1845 - 1932

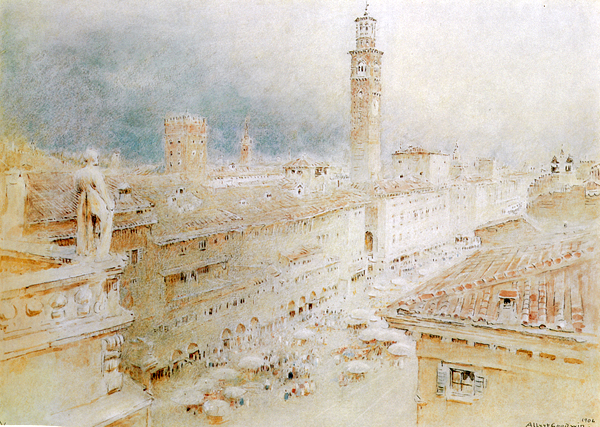

Ponte Pietra Verona: 1896

by Albert Goodwin

The following articles about the Life and Work of Albert Goodwin can be found on the Art Renewal Center's Page and were compiled by Chris Beetles and they are the created work of the cited authors, and I provide them here for a broader understanding of this landscape artist.

Senex Magister

underestimate the gift God has given me…and in its measure this pleasure is passed along to those who know my work…Beauty - the beauty that is in the landscape - is a sealed book to many, hence in a degree the landscape painter may magnify his calling, for is he not one who is helping to open the eyes of the blind that they may see the hand of our Heavenly Father in the things that he has made for our delight?

However, the Pre-Raphaelites were not the only source of inspiration in the artistic development of Goodwin; more important perhaps for the development of his mature style was Joseph Mallord William Turner - and the link between Turner, the Pre-Raphaelites and Goodwin was, of course, Ruskin. Goodwin met Ruskin towards the end of the 1860, probably as a result of his association with Hughes and Brown, and during the next few years, a friendship developed between them, with Goodwin holidaying with Ruskin at Abingdon and Matlock in 1871, and then in the following year, Goodwin spent three months touring Italy with Ruskin and another one of his protégés, Arthur Severn. The relationship with Ruskin was of considerable importance to Goodwin, as until then he had paid little attention to drawing, but had been noted as an artist with 'an originality and courage in…the use of his paint box'. Now, under the guidance of Ruskin, he began to pay more attention to drawing, noting some years later that,I owe much thanks to Ruskin, who ballyragged me into love of form when I was getting too content with color alone: and color alone is luxury…how much I enjoyed the three months I had when I took up with drawing when with Ruskin in Italy; and how good it was for one. The pleasure that is to be found in lines which should string a drawing together is almost an unknown quantity in these days of paint and paint only.

Although it was Ruskin who made Goodwin show a greater concern for drawing, and who encouraged him in the development of his sensitive use of the pen, it was the example of Turner who above all liberated the genius of Albert Goodwin. Ruskin himself had no difficulty in reconciling his admiration for the Pre-Raphaelites with his passion for Turner, as he saw them representing two stages of artistic development; for having exhorted the young artist to study nature most carefully, 'rejecting nothing, selecting nothing, and scorning nothing', he goes on to say, 'then, when their memories are stored, and their imagination fed…let them take up the scarlet and gold, give reins to their fancy and show us what their heads are made of'. It is into this second stage that Turner's work falls, and Goodwin himself from the mid 1870's, but most especially from around the turn of the century, more and more in his poetic use of color and sensitive use of the pen, succumbed to the magical spell of Turner's work; so much so, that he subsequently observed that 'I wonder sometimes of the spirit of old Turner makes use of my personality! I often find myself doing the very things that he seemed to do'. Turner was important for Goodwin in two particular aspects of his work; in the first place, he was greatly influenced by Turner's skill in combining fact and fancy in his landscapes views, thus emulating that feature of Turner's work so aptly described by Ruskin as 'imaginative topography' and secondly, he learned certain technical skills, such as the ability of achieving both breadth and detail in his water-colors, by a skilful and sensitive combination of wash and pen-work - characteristics that are well illustrated in much of his later work, especially from the years circa 1895-1925. Although Goodwin is now best remembered for his work in watercolors, he also worked from time to time in oils. His large oil painting of Ali Baba and The Forty Thieves was bought by the Tate Gallery under the terms of the Chantery Bequest of 300 guineas in 1901. Indeed, in the early part of his career, he seriously considered the possibility of working more extensively in oils. It may be that he was caught up in the prevailing belief that oil painting was a higher and more serious art form, and the one by which artistic reputations were made. Fortunately he sought the advice of Ruskin, who rightly observed that I have always felt deep regret at your taking to oil… The virtue of oil, as I understand it, is perfect delineation of solid form in deep local color.Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves

The Arabian Nights or The Thousand and One Nights is a loose collection of stories written in Arabic, which were known in Europe by the early-eighteenth century. Their magic and adventure captivated the Western imagination and greatly contributed to the vogue for 'oriental' literature and images into the nineteenth century.

Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves is generally regarded as one of these tales. Here, in an enchanted landscape, Goodwin shows the moment when Ali Baba observes the thieves entering a cave, which they have opened by pronouncing the words 'Open, Sesame!'.

There was a second prison from which Goodwin felt the need to escape - an artistic cell to which he was confined by John Ruskin.

Ruskin, with his conviction that form mattered more than color, commanded Goodwin in his youth that the artist must always choose for his subject a scene or an object of beauty - that is, a subject beautiful in its own right. In Victorian England, where the landscape changed dramatically every day under the weight of heavy industry and the blue sky turned to smoky grey, this requirement ruled out an enormous number of subjects. The Ruskin rule in effect condemned the artist to paint something other than what lay before him - to escape from ugly modern life to scenes more beautiful, to escape, in old-fashioned language, to the ideal world that was inhabited by painters from Raphael to Sir Joshua Reynolds. In a phrase, Ruskin forbade the existence of 'Contemporary Art' - or much, if not all of it. Goodwin's diaries make clear that he chafed at this. He envied James Abbott McNeill Whistler, who expressed public contempt for Ruskin, and he envied the freedom Whistler felt to paint the ugly and to be expressionist about it. In some diary entries, Goodwin openly admired Whistler, feeling him to be more correct about color than Ruskin was about form. Which way to go? Forcing himself to choose, Goodwin backed the 19th century, declaring Ruskin to be 'the truer wisdom' (Diary, 29 December 1914). He decided this when Ruskin was out of date in a 20th century that has elevated the ugly. Goodwin, in his grave, may nourish the hope that in the 21st Century he, Ruskin and the concept of beauty will steam back into fashion - that ugliness has run its course with the ultra-democratic art history of our time. The escape of Albert Goodwin from Turner and Ruskin, the lifetime journey that he made to a style maturely and unmistakably his own, was not an easy one. I sometimes wonder if the spirit of old Turner takes over my personality. I often find (or think I find) myself doing the very same things that he seemed to do. That is no more than a reference to Goodwin using spare paint on the palette at the end of one picture to start a new one but it announces the eternal presence of Turner in his mind. Hammond Smith, Goodwin's first and chief biographer, claims that his admiration for Turner was more present in his post-1900 work than at any other time,in his poetic and atmospheric use of color, in his delicate and much more sensitive use of the pen, but most especially perhaps in his ability to combine a feeling for breadth with an eye for detail, which was such an unique feature of Turner's work.

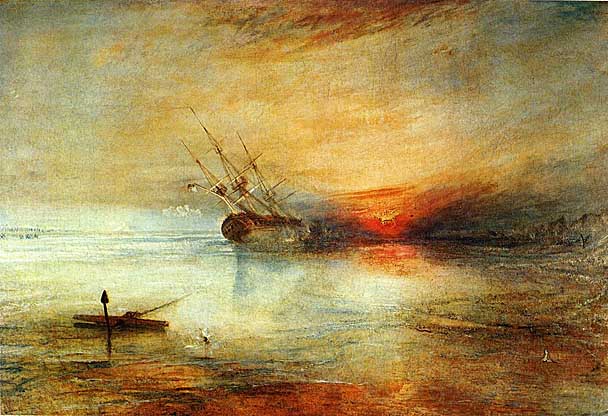

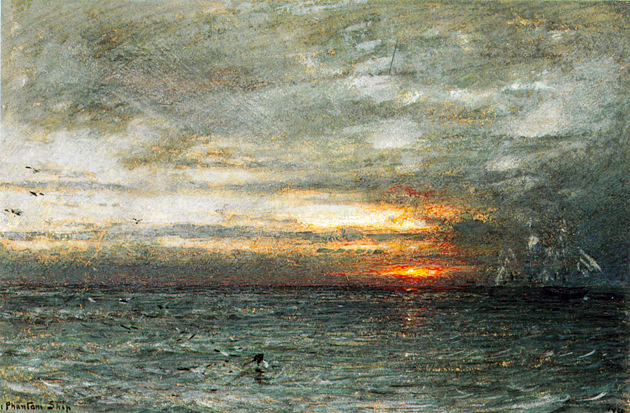

One sees why he says this: "lay Turner's Fort Vimieux of 1831 alongside a 1914 Goodwin sunset and it does look as if little has happened in between. Turner's rendering of vast, glowing abstract areas of color in the 1835-40 oils and watercolors is undoubtedly faithfully reproduced in many Goodwin works. And yet Goodwin can be easily distinguished from Turner. How?"Fort Vimieux: 1831

by Joseph Mallord William Turner

I tried to find the 1914 Sunset but I couldn't find it. At least there was no certainty in my untrained mind that is was the painting mentioned in this article. Yet, I did find a couple which, I think, bears out the point of Goodwin's use of color in his watercolors. Compare the next two works with Turner's Fort Vimieux.

Senex Magister

A Tropical Sunset

Venice

Benares: 1917

The Thames near Walton Bridges

by Joseph Mallord William Turner

Mortlake Terrace: 1826

by Joseph Mallord William Turner

T. S. Eliot in 1938

by Wyndham Lewis

Fashion and art history are transient things. What endures is art creation and merit.

It matters not that in the definition of Frances Spalding and certain art historians, Goodwin was not 'of his time' or century after 1905, to use that imprisoning phrase of Baudelaire which has so limited the judgments of art history. And it is simply wrong to dismiss him - or any other artist - as part of a Victorian past that, at a thunderclap, became dead on the spot in 1901 and was without further relevance. Life is not so tidy and this is simply bad history. Goodwin did important work on either side of the First World War, and during it. His most personal pictures of this time have a value which is considerably understated in 2007. That understatement also means that his 21st century price is absurdly low. So how are we to praise Albert Goodwin? The Maidstone prodigy did not go short in his own time. His first painting to be acclaimed reached the Royal Academy by age 15, as did Turner's. Ruskin, who gave Goodwin a first Grand Tour of Europe, complete with culture shocks, in 1872, made him a favorite son and saluted his 'pure aesthetic delight'.Westminster

Beachy Head: 1920

The Gardens, Pallanza

Lincoln Canal: 1926

Palma, Majorca: 1925 # 125

Palma, Majorca: 1925 # 127

Bristol: 1893

This is not the Harbor at Bristol but an earlier work of Goodwin.

Senex Magister

Music in the Tuileries: 1862

by Édouard Manet

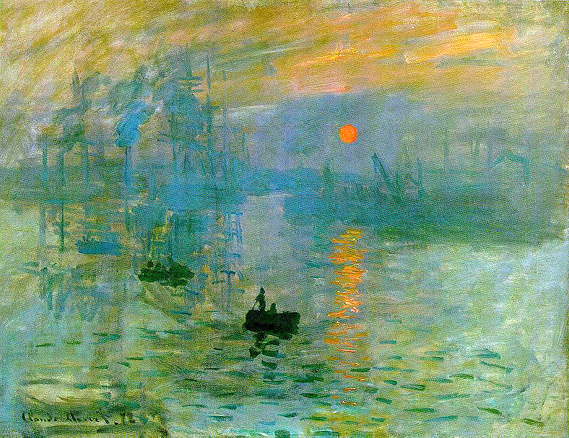

Impression, Sunrise: 1872

by Claude Monet

Various Works of Albert Goodwin

A Baptism of Flowers: 1877

A Days End

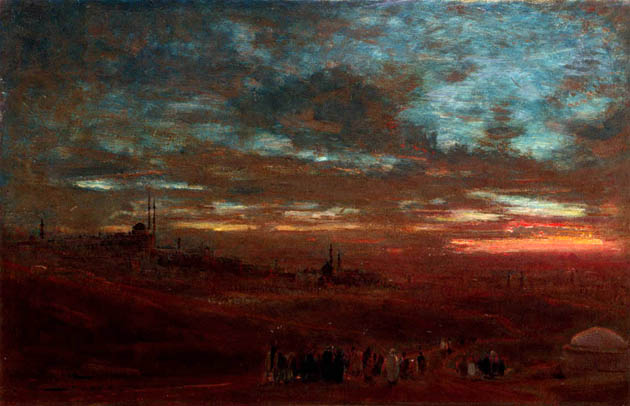

A Nile Sunset: 1916

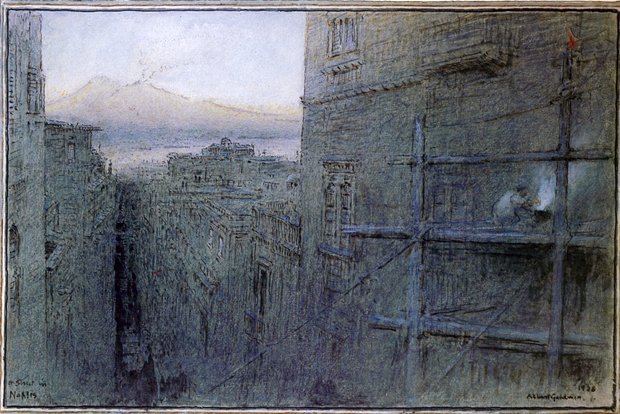

A Street in Naples: 1926

A View of Cairo at Sunset

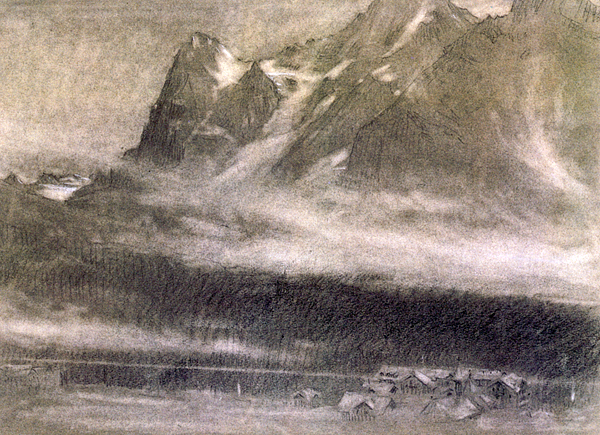

Alpine Valley

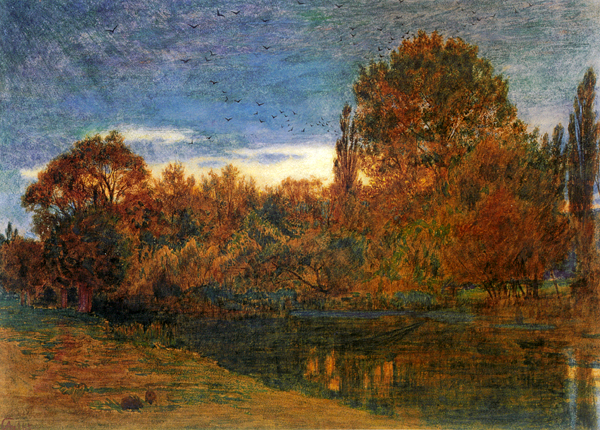

Aspen Trees in Autumn: 1865

This early watercolor by Goodwin was exhibited at the Dudley Gallery in 1866. Its subject tallies with the exhibition title, and reviewers' descriptions confirm the identification. The Athenaeum mentioned the `still pool with trees' and the Illustrated London News noted the sunset effect leading to extreme `oppositions of color'.

The exhibition opened in February, three months before the main London exhibition season, and was Goodwin's first opportunity to exhibit a work produced the previous autumn.

The painting was extensively and generally well reviewed. The Illustrated London News stated: Mr. Goodwin is an artist of whom much may be expected. Highest praise came from the critic of the Saturday Review:

"Aspen Trees in Autumn. Albert Goodwin. - This is one of the most remarkable works in the room. It is a thoroughly careful study of autumnal color, great attention being evident at the same time paid to form, and to light and shade. So earnest an endeavor to unite the three great qualities of good painting is seldom met with. And the best of it is that on all three points the artist has succeeded. The trees are most gracefully drawn, the color is very true, and the arrangement of light and shade so telling that the work would engrave well."

At the beginning of his career, Goodwin had worked as an oil painter but in the 1860's he transferred his allegiance to watercolors. This change of medium would have been encouraged by such praise.

The Dudley Gallery was a natural choice of venue for Goodwin at this period of transition. The exhibition of the Old and New Watercolor Societies were restricted to the works of members and associates, and in the mid Nineteenth Century, artists who worked in oil as well as watercolor were rarely elected. The Royal Academy displayed watercolor work poorly.

The Dudley Gallery was founded in 1865 as an alternative open exhibition for watercolors. It attracted aspirants to the two older societies (in fact Goodwin was elected Associate of the Old Watercolor Society in 1872), as well as watercolors by established oil painters. Because it was run by a committee of young artists, it gained a reputation for liberalism and in the 1860's was favored by the Pre-Raphaelites and their followers. Goodwin was a pupil of both Hughes and Madox Brown, and it is worth noting that the Dudley Gallery was the only London exhibition used by Madox Brown in this period.

Apocalypse

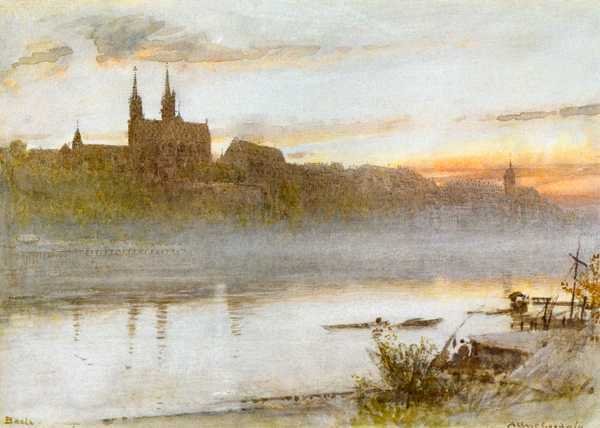

Basle

Blankeney, Norfolk: 1919

Boulay Bay, Jersey: 1864

In the summer of 1864, Ford Madox Brown wrote a letter to his patron James Leathart of Newcastle suggesting that he purchased a series of beautiful works of Jersey by his pupil, Albert Goodwin. He predicted that the young painter would become the greatest landscape artist of his time:

"My pupil Mr. Goodwin has recently returned from Jersey with a very admirable set of drawings - As I promised him to send them to you for inspection and also you may remember promised you to do so, I take it upon me without further leave to have them placed in the case along with 'Oure Ladye' for although, as you say, you are not at present prepared for extensive purchase, yet these drawings, all who have seen them think so very beautiful that I cannot help thinking you will retain some of them.

Considering how fine most of them are and the extreme youth of the artist (only 19) I think there can be no doubt of his becoming before long one of the greatest landscape painters of the age.

Hughes who was his first master came over this afternoon to help us to price them, we have done to the best of our ability and the result is the enclosed list.

Should you buy any or even all (for it is a very cheap list) we should feel obliged by your sending back the whole of them in a week - for as yet scarce any one has seen them and no doubt they will do him much good by being shown …"

(Letter held in the Library of the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, dated July 18th, 1864)

During his years studying with Madox Brown, Goodwin described how he had learned the need of hard work. Boulay Bay is undoubtedly one of those works referred to in Madox Brown's letter quoted above, painted with a rich primary color scheme reminiscent of Brown's own magical realism, seen in intense colors of his landscape masterpiece, Walton on the Naze (Birmingham City Art Gallery).

Walton on the Naze

by Ford Madox Brown

The artist (Ford Madox Brown) and his family stayed in Walton-on-the-Naze, a small town on the Essex coast, in August 1859. The gentleman on the left discussing the beauty of the scene is undoubtedly a self-portrait of Brown. The lady and the little girl, drying their hair after bathing, are his wife Emma and their daughter Catherine. The scene is concerned with the theme of leisure, and the developing mid-nineteenth century interest in tourism. Londoners could reach the resort by steamer - visible on the horizon. The tourists are contrasted against the world of work represented by the stacks of wheat in the foreground, the smoking factory in the background and the ships in the estuary.

Cairo: 1905

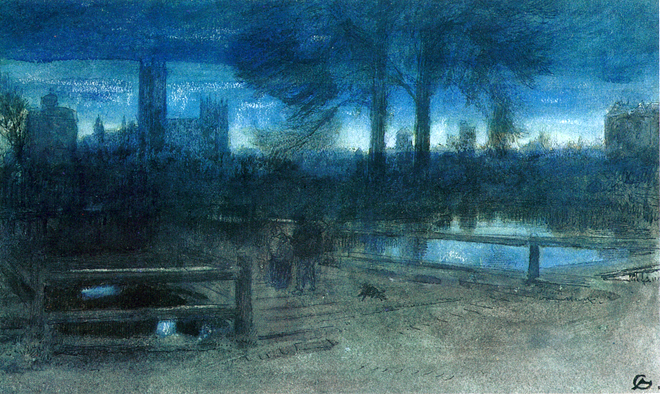

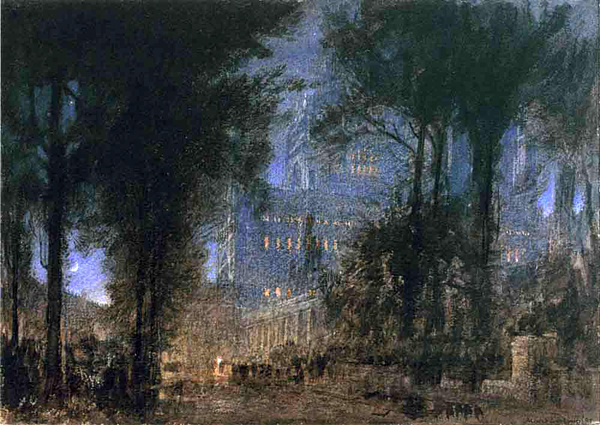

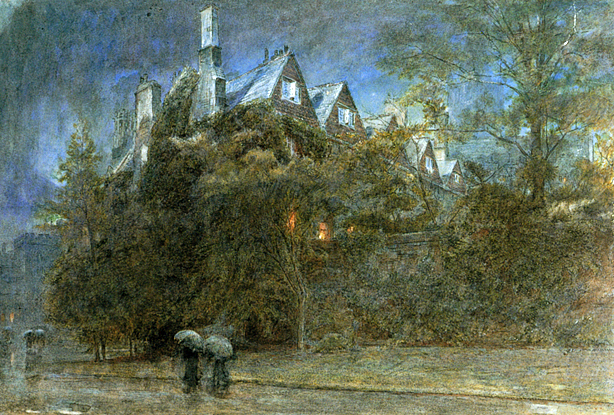

Canterbury by Night

Certosa: 1873

Christian and Faithfull in the Grounds of Giant Despair

Cleaning Nets: 1883

Clovelly: 1921

Clovelly is a fishing village on the north coast of Devon, England. Famous for its steep cobbled high street, the village has inspired many artists with its quaint beauty.

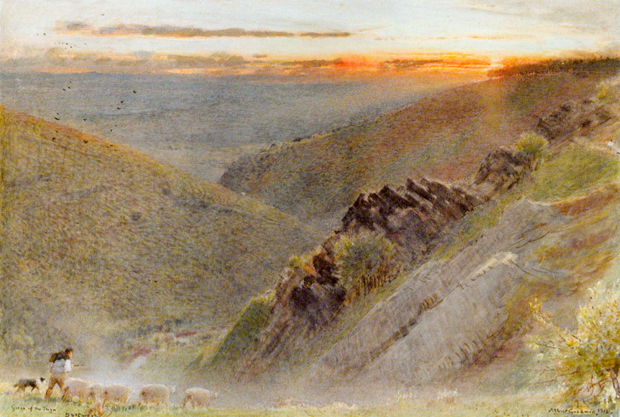

Dartmoor, Gorge of the Teign: 1913

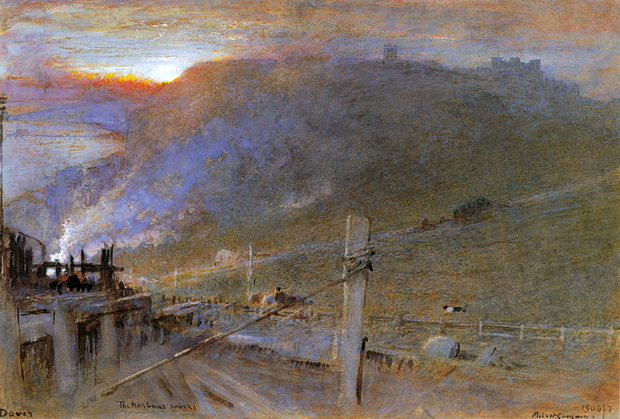

Dover, The Harbour Works: 1906-07

Durham: 1900

Durham Cathedral

This hazy view of Durham Cathedral shows Albert Goodwin's interest in atmosphere and light. The trees and water emerge from a mist of color in a manner similar to the style of J.M.W. Turner, whose work Goodwin admired. Albert Goodwin was based in London, but travelled extensively to paint landscapes.

Exeter: 1922

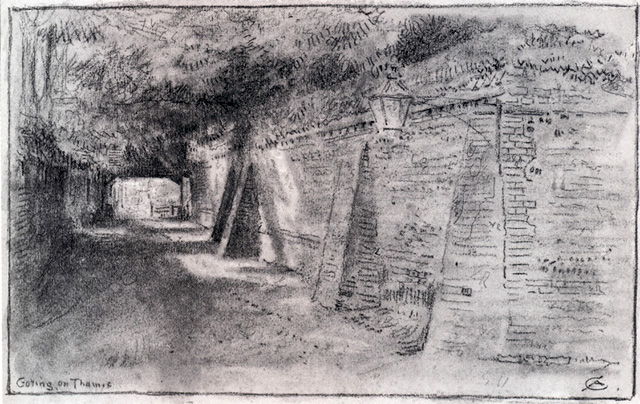

Goring on Thames

Hastings

Holyroad

In The Smoke of His Burning: 1913

Lincoln: 1904

Low Tide on the South Coast, near Brighton: 1868

Albert Goodwin was a master of watercolor technique. This shore scene evokes the luminous glow of dusk by using a combination of washing, scumbling and sponging with rich effervescent coolers. Albert Goodwin was living in Waterloo Street in Brighton at the time. He exhibited a series of these radiantly atmospheric twilit scenes at the Dudley Gallery from 1866 onwards where they were noted for their magnificent color, one being described as … all aflame with its crimson sunset (The Spectator, 1866).

Under the influence of his mentors, Arthur Hughes, Ford Madox Brown and, to an extent, Samuel Palmer, Albert Goodwin's landscape watercolors became more poetical toward the end of the 1860's. Nature was to Goodwin a manifestation of God Himself, and painting an outlet for his growing religious spirituality: The whole natural world, down to the smallest detail, is one great allegory, typical of the spiritual world. Our business is to study the natural world as the continued revelation of God, guiding us forever into fresh revelation of Himself. (An extract from Albert Goodwin's Diary)

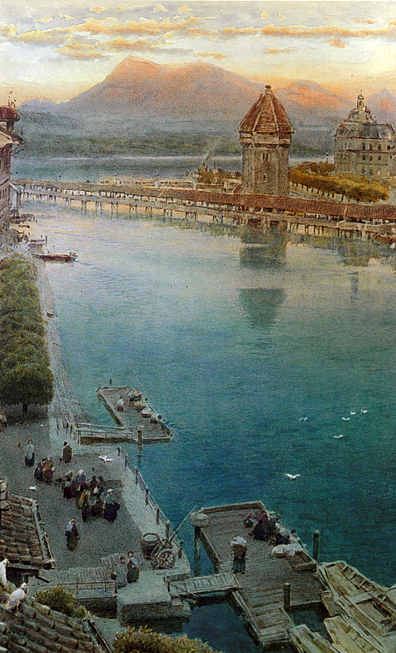

Lucerne

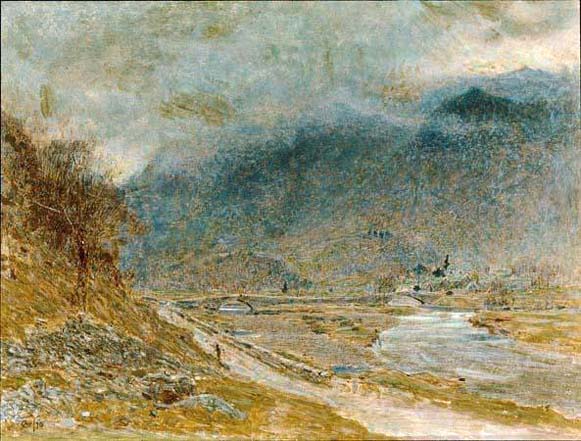

Matlock

Mont San Michel: 1898

Moored Boats in Rotterdam

Monte Carlo at Night: 1926

Mountain Mist: 1870

On the Road to Winchester

Penzance

Saint Leonard's: 1908

Saint Leonard's demonstrates the level of technical and visual sophistication that Albert Goodwin achieved. His objective in the watercolor is to give a sense of aerial perspective; both his purpose and his solution owe much to his study of Turner. No compositional support is required to allow the viewer to feel the expanse of wet sand that forms the vast triangular foreground to the drawing. The modulation of color within this area, combined with a density of glistening texture, allows the eye to perceive the area as a flat expanse on the basis of abstract visual information.

Saint Michael's Mount: 1913

Salisbury Close: 1897

Shipwreck: Sinbad the Sailor Storing his Raft - 1887

Shore Scene at Sunset: 1865

Sleeping in the Moonlight, Monastery of Saint Francis of Assisi

Sunset, The Lion's Mouth Surinam Dutch Guiana: 1912

Sunset Through Woodland: 1865

The Abby Church, Christchurch

The Evening Service Salisbury

The Hardy Norseman in Venice: 1904

The Jungle

The Phantom Ship: 1900

The Rain from Heaven, All Souls, Oxford: 1922

The Sea Raiders

The Shipbreakers Yard

The Source of the Sacred River: ca 1900

The Venetian Lagoons

The Village of Corfe

Torre del Greco and Capri

Verona

Venice: 1892

Albert Goodwin first travelled to Venice in 1872 in the company of John Ruskin, the greatest enthusiast for the city of the Victorian age. Although Goodwin made subsequent visits there, he developed his sketches and ideas from this early trip until the end of the century, stating in the catalogue of his 1896 London exhibition:

"Though I date my pictures at the time of their completion, I would by no means have it inferred that the whole of this exhibition has been done in the last year. Some of the subjects were begun as many as twenty years ago."

It is clear, however, that the present work has its genesis in a later visit. Albert Goodwin shed the Pre-Raphaelite inspiration, and under Turner's influence developed a brilliant rendering of space and atmosphere, seen to full effect in his handling of the pastel.

His qualities were still recognized in 1933 in his obituaries, for Albert Goodwin was one of the few Victorian painters to retain his popularity in the twentieth century. The Connoisseur wrote:

"Mr. Albert Goodwin... was one of the few artists for whom some measure of Old Mastership can be reasonably predicted in their lifetimes. A landscape painter of rare delicacy and imagination, he possessed the art of capturing effects so ethereal as to make them almost impossible of attainment by ordinary means. There are not many artists who have this facility, but Goodwin was one of them."

Venice-Midsummer Dawn: ca 1872 - ca 1900

Albert Goodwin took a three-month trip to Italy in 1872 with John Ruskin who was his mentor and perhaps the greatest Victorian enthusiast for the city of Venice. It is clear, however, that Venice - A Midsummer Dawn has its foundation in a later visit to Venice. Goodwin has shed the Ruskin qualities visible in so many of his works and under Turner's influence developed a brilliant rendering of space and atmosphere. He had the ability to convey a sense of atmosphere with areas of nebulous washes flecked with calligraphic touches.

View from the Entrance to Meadow Building

Christchurch College, Oxford: 1923

Wells from Roof of Parish Church: 1903

Westminster: 1917

Winchester: 1864

This watercolor dates from the period when Goodwin was studying under Madox Brown, and shares many characteristics of Brown's Pre-Raphaelite landscapes of the 1850's, although already Goodwin's distinctive concern with atmospheric effects is apparent in the subtle treatment of the sunset sky and its reflection. From Brown, Goodwin said he learnt the need of hard work. In this particular watercolor he also seems to have learnt from Brown's ability to juxtapose red roofs and green foliage, from his ability to produce a loving depiction of an ordinary scene (for this view is not a conventionally picturesque composition) and from his interest in the inhabitants of a place as they go about their daily lives. Even in this tiny watercolor Goodwin has introduced a group of men fishing and a woman and child with a dog.

Brown was clearly impressed by the picture. An old label on the backboard records that Boyce bought it off the artist through the intermediary of Ford Madox Brown. Boyce is another painter whom the work would have interested, as he produced detailed watercolors of vernacular buildings and old towns similar to this.

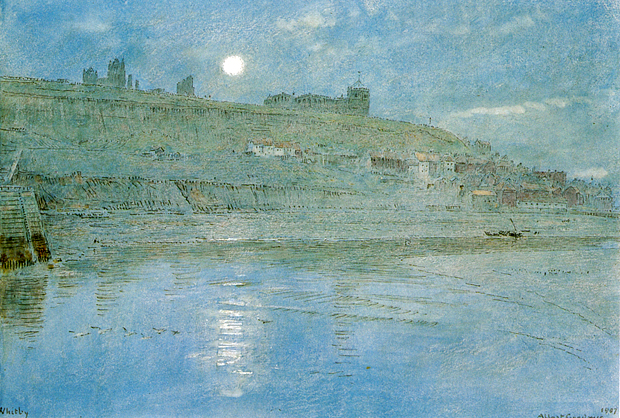

Whitby

Whitby Abbey: 1910

Whitby Abbey was founded by Saint Hilda in 657 and was destroyed by the Danes in 867. The building in Goodwin's painting was constructed in the thirteenth century. In 1830 one of the Abbey's towers collapsed. The Abbey today looks just as it does in this painting.

Goodwin loved painting dramatic, poetic landscapes. The richly glowing deep blue of the sky in this painting is very typical of his work. Whitby Abbey was a favorite subject for Goodwin, partly because of its ruinous appearance, but also because he was deeply religious man, with a profound interest in spiritual subjects. When Goodwin painted this in 1910, he had been painting Whitby Abbey intermittently for at least fourteen years. Goodwin spent much of his life travelling, visiting Egypt, India and America, as well as travelling extensively in Britain and Europe. He painted many of the places he visited.

Whitby Abbey: 1922

Whitby by Moonlight: 1907

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.