English Romantic Artist

1776 - 1837

We see nothing truly until we understand it.

An artist who is self-taught is taught by a very ignorant person indeed.

Painting is a science and should be pursued as an inquiry into the laws of nature. Why, then, may not a landscape be considered as a branch of natural philosophy, of which pictures are but experiments?

I associate my careless boyhood with all that lies on the banks of the Stour. Those scenes made me a painter and I am grateful - that is, I had often thought of pictures of them before ever I touched a pencil.

I never saw an ugly thing in my life: for let the form of an object be what it may, - light, shade, and perspective will always make it beautiful.

I know very well what I am about and that my skies have not been neglected, though they often failed in execution - and often no doubt from over anxiety about them.

I am anxious that the world should be inclined to look to painters for information about painting.

Speaking to a lawyer about pictures is something like talking to a butcher about humanity.

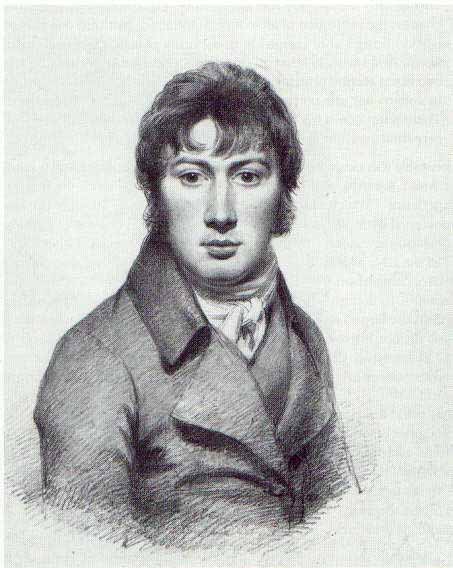

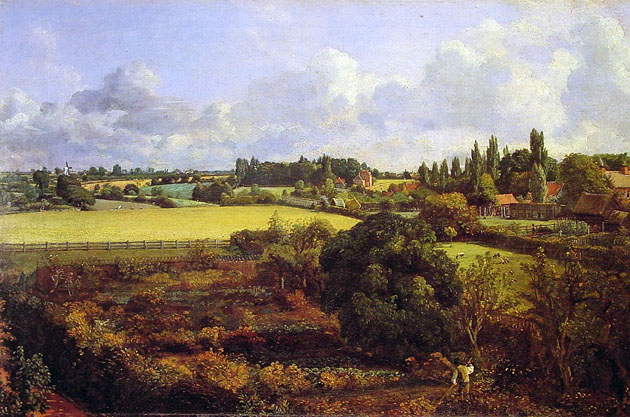

John Constable was an English Romantic painter. Born in Suffolk, he is known principally for his landscape paintings of Dedham Vale, the area surrounding his home-now known as "Constable Country"-which he invested with an intensity of affection. "I should paint my own places best", he wrote to his friend John Fisher in 1821, "painting is but another word for feeling".

His most famous paintings include Dedham Vale of 1802 and The Hay Wain of 1821. Although his paintings are now among the most popular and valuable in British art, he was never financially successful and did not become a member of the establishment until he was elected to the Royal Academy at the age of 52. He sold more paintings in France than in his native England.

John Constable was born in East Bergholt, a village on the River Stour in Suffolk, to Golding and Ann Constable. His father was a wealthy corn merchant, owner of Flatford Mill in East Bergholt and, later, Dedham Mill. Golding Constable also owned his own small ship, The Telegraph, which he moored at Mistley on the Stour estuary and used to transport corn to London. Although Constable was his parents' second son, his older brother was mentally handicapped and so John was expected to succeed his father in the business, and after a brief period at a boarding school in Lavenham, he was enrolled in a day school in Dedham. Constable worked in the corn business after leaving school, but his younger brother Abram eventually took over the running of the mills.

In his youth, Constable embarked on amateur sketching trips in the surrounding Suffolk countryside that was to become the subject of a large proportion of his art. These scenes, in his own words, "made me a painter, and I am grateful"; "the sound of water escaping from mill dams etc., willows, old rotten planks, slimy posts, and brickwork, I love such things." He was introduced to George Beaumont, a collector, who showed him his prized Hagar and the Angel by Claude Lorrain, which inspired Constable. Later, while visiting relatives in Middlesex, he was introduced to the professional artist John Thomas Smith, who advised him on painting but also urged him to remain in his father's business rather than take up art professionally.

In 1799, Constable persuaded his father to let him pursue art, and Golding even granted him a small allowance. Entering the Royal Academy Schools as a probationer, he attended life classes and anatomical dissections as well as studying and copying Old Masters. Among works that particularly inspired him during this period were paintings by Thomas Gainsborough, Claude Lorrain, Peter Paul Rubens, Annibale Carracci and Jacob van Ruisdael. He also read widely among poetry and sermons, and later proved a notably articulate artist. By 1803, he was exhibiting paintings at the Royal Academy.

In 1802 he refused the position of drawing master at Great Marlow Military College, a move which Benjamin West (then master of the RA) counseled would mean the end of his career. In that year, Constable wrote a letter to John Dunthorne in which he spelled out his determination to become a professional landscape painter:

His early style has many of the qualities associated with his mature work, including a freshness of light, color and touch, and reveals the compositional influence of the Old Masters he had studied, notably of Claude Lorrain. Constable's usual subjects, scenes of ordinary daily life, were unfashionable in an age that looked for more romantic visions of wild landscapes and ruins. He did, however, make occasional trips further afield. For example, in 1803 he spent almost a month aboard the East Indiaman ship Coutts as it visited south-east coastal ports, and in 1806 he undertook a two-month tour of the Lake District. But he told his friend and biographer Charles Leslie that the solitude of the mountains oppressed his spirits; Leslie went on to write:

In order to make ends meet, Constable took up portraiture, which he found dull work-though he executed many fine portraits. He also painted occasional religious pictures, but according to John Walker, "Constable's incapacity as a religious painter cannot be overstated."

Constable adopted a routine of spending the winter in London and painting at East Bergholt in the summer. And in 1811 he first visited John Fisher and his family in Salisbury, a city whose Cathedral and surrounding landscape were to inspire some of his greatest paintings.

From 1809 onwards, his childhood friendship with Maria Bicknell developed into a deep, mutual love. But their engagement in 1816 was opposed by Maria's grandfather, Dr Rhudde, Rector of East Bergholt, who considered the Constables his social inferiors and threatened Maria with disinheritance.

Maria's father, Charles Bicknell, a solicitor, was reluctant to see Maria throw away this inheritance, and Maria herself pointed out that a penniless marriage would detract from any chances John had of making a career in painting.

Golding and Ann Constable, while approving the match, held out no prospect of supporting the marriage until Constable was financially secure; but they died in quick succession, and Constable inherited a fifth share in the family business.

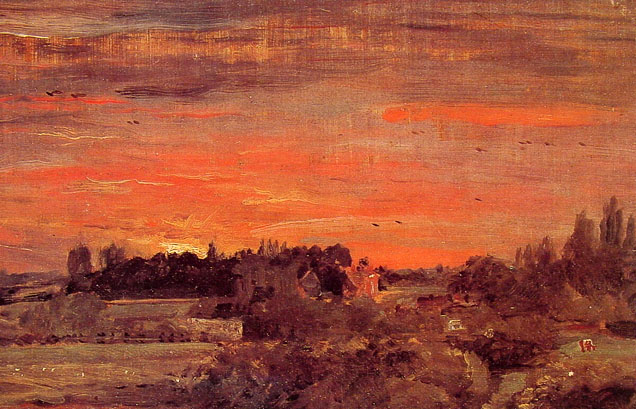

John and Maria's marriage in October 1816 was followed by a honeymoon tour of the south coast, where the sea at Weymouth and Brighton stimulated Constable to develop new techniques of brilliant color and vivacious brushwork. At the same time, a greater emotional range began to register in his art.

Although he had scraped an income from painting, it was not until 1819 that Constable sold his first important canvas, The White Horse, which led to a series of "six footers", as he called his large-scale paintings.

He was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy that year, and in 1821 he showed The Hay Wain (a view from Flatford Mill) at the Academy's exhibition. Théodore Géricault saw it on a visit to London and was soon praising Constable in Paris, where a dealer, John Arrowsmith, bought four paintings, including The Hay Wain, which was exhibited at the Paris Salon of 1824, winning a gold medal.

Although the painting evokes a Suffolk scene, it was created in the artist's studio in London. Constable first made a number of open-air sketches of parts of the scene. He then made a full-size preparatory sketch in oil to establish the composition.

The painting was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1821, the year it was painted, but failed to find a buyer. Yet when exhibited in France, with other paintings by Constable, the artist was awarded a Gold Medal by Charles X.

Of Constable's color, Delacroix wrote in his journal: "What he says here about the green of his meadows can be applied to every tone". Delacroix repainted the background of his 1824 Massacre de Scio after seeing the Constables at Arrowsmith's Gallery, which he said had done him a great deal of good.

In his lifetime Constable was to sell only twenty paintings in England, but in France he sold more than twenty in just a few years. Despite this, he refused all invitations to travel internationally to promote his work, writing to Francis Darby: "I would rather be a poor man (in England) than a rich man abroad."

In 1825, perhaps due partly to the worry of his wife's ill-health, the lack of congeniality of living in Brighton ("Piccadilly by the Seaside"), and the pressure of numerous outstanding commissions, he quarreled with Arrowsmith and lost his French outlet.

After the birth of her seventh child in January 1828, Maria fell ill and died of tuberculosis that November at the age of forty-one. Intensely saddened, Constable wrote to his brother Golding, "hourly do I feel the loss of my departed Angel-God only knows how my children will be brought up…the face of the World is totally changed to me".

Thereafter, he always dressed in black and was, according to Leslie, "a prey to melancholy and anxious thoughts". He cared for his seven children alone for the rest of his life.

Shortly before her death, Maria's father had died, leaving her £20,000. Constable speculated disastrously with this money, paying for the engraving of several mezzotints of some of his landscapes in preparation for a publication. He was hesitant and indecisive, nearly fell out with his engraver, and when the folios were published, could not interest enough subscribers. Constable collaborated closely with the talented mezzotinter David Lucas on some forty prints after his landscapes, one of which went through thirteen proof stages, corrected by Constable in pencil and paint. Constable said, "Lucas showed me to the public without my faults", but the venture was not a financial success.

He was elected to the Royal Academy in February 1829, at the age of 52, and in 1831 was appointed Visitor at the Royal Academy, where he seems to have been popular with the students.

He also began to deliver public lectures on the history of landscape painting, which were attended by distinguished audiences. In a series of such lectures at the Royal Institution, Constable proposed a threefold thesis: firstly, landscape painting is scientific as well as poetic; secondly, the imagination cannot alone produce art to bear comparison with reality; and thirdly, no great painter was ever self-taught.

He also later spoke against the new Gothic Revival movement, which he considered mere "imitation".

In 1835, his last lecture to the students of the RA, in which he praised Raphael and called the R.A. the "cradle of British art", was "cheered most heartily". He died on the night of the 31st of March, apparently from indigestion, and was buried with Maria in the graveyard of Saint John-at-Hampstead, Hampstead. (His children John Charles Constable and Charles Golding Constable are also buried in this family tomb.)

Constable quietly rebelled against the artistic culture that taught artists to use their imagination to compose their pictures rather than nature itself. He told Leslie, "When I sit down to make a sketch from nature, the first thing I try to do is to forget that I have ever seen a picture".

Although Constable produced paintings throughout his life for the "finished" picture market of patrons and R.A. exhibitions, constant refreshment in the form of on-the-spot studies was essential to his working method, and he never satisfied himself with following a formula. "The world is wide", he wrote, "no two days are alike, nor even two hours; neither were there ever two leaves of a tree alike since the creation of all the world; and the genuine productions of art, like those of nature, are all distinct from each other."

Constable painted many full-scale preliminary sketches of his landscapes in order to test the composition in advance of finished pictures. These large sketches, with their free and vigorous brushwork, were revolutionary at the time, and they continue to interest artists, scholars and the general public. The oil sketches of The Leaping Horse and The Hay Wain, for example, convey a vigor and expressiveness missing from Constable's finished paintings of the same subjects. Possibly more than any other aspect of Constable's work, the oil sketches reveal him in retrospect to have been an avant-garde painter, one who demonstrated that landscape painting could be taken in a totally new direction.

The painting is deliberately 'grand' in conception and recalls some of the great equestrian portraits of the past by Leonardo and Velazquez. It is less specific in its sense of a particular moment than Constable's earlier Stour paintings: instead of being set at noon, for instance, it focuses on wind and light in a more abstract and generalized fashion. Constable uses the turbulent sky to echo the energetic movement of horse and rider.

Significantly, Constable takes liberties with the actual topography of his scene, moving the spire of Dedham Church far from its actual position. While his frequent changes to the full-scale sketch and finished canvas show his increasing concern to get a satisfying composition, the church is also a powerful spiritual presence in Constable's personal landscape.

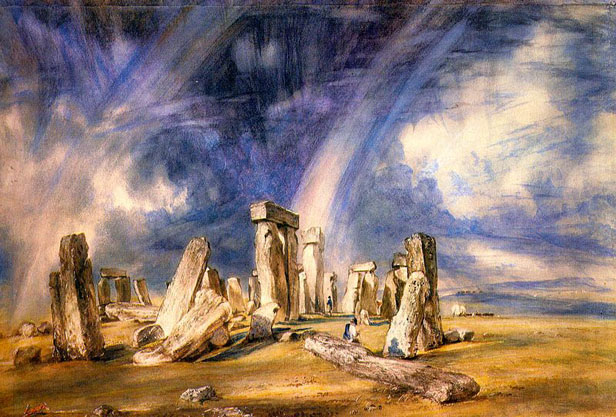

Constable's watercolors were also remarkably free for their time: the almost mystical Stonehenge, 1835, with its double rainbow, is often considered to be one of the greatest watercolors ever painted. When he exhibited it in 1836, Constable appended a text to the title: "The mysterious monument of Stonehenge, standing remote on a bare and boundless heath, as much unconnected with the events of past ages as it is with the uses of the present, carries you back beyond all historical records into the obscurity of a totally unknown period."

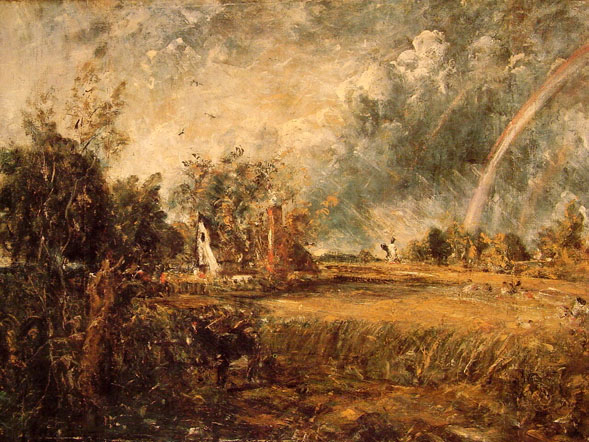

The double rainbow was a recurrent motif in Constable's later works, but Constable wavered on its symbolic meaning. Sometimes he picked out specific symbols in his work (seeing a ruin, for example, as himself after the death of his wife), but at other times the nature that he observed was simply nature - a rainbow meaning no more than 'the exhilaration of the returning sun'.

In addition to the full-scale oil sketches, Constable completed numerous observational studies of landscapes and clouds, determined to become more scientific in his recording of atmospheric conditions. The power of his physical effects was sometimes apparent even in the full-scale paintings which he exhibited in London; The Chain Pier, 1827, for example, prompted a critic to write: "the atmosphere possesses a characteristic humidity about it, which almost imparts the wish for an umbrella".

The 1820's were some of the busiest years of Brighton's development as a fashionable seaside resort. Here Constable shows the bustling life of the beach against a backdrop of Brighton's new hotels, residential quarters and the Chain Pier itself. The pier opened in 1823, shortly before Constable's first visit, but was destroyed by storm in 1896.

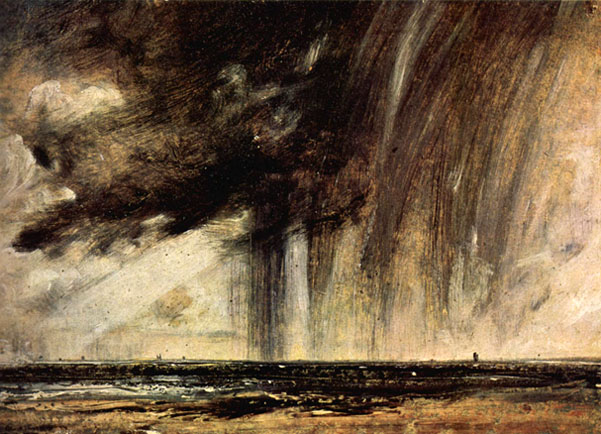

The sketches themselves were the first ever done in oils directly from the subject in the open air. To convey the effects of light and movement, Constable used broken brushstrokes, often in small touches, which he stumbled over lighter passages, creating an impression of sparkling light enveloping the entire landscape. One of the most expressionistic and powerful of all his studies is Seascape Study with Rain Cloud, painted in around 1824 at Brighton, which captures with slashing dark brushstrokes the immediacy of an exploding cumulus shower at sea. Constable also became interested in painting rainbow effects, for example in Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows, 1831, and in Cottage at East Bergholt, 1833.

Salisbury Cathedral is seen here from the north-west, with Long Bridge over the River Avon on the extreme right. The most striking feature of the composition is the arching rainbow. However, Constable appears to have introduced this at a late stage in planning the picture. Much of the atmospheric effect of the painting is achieved by Constable's extensive use of the palette knife in addition to the brush.

To the sky studies he added notes, often on the back of the sketches, of the prevailing weather conditions, direction of light, and time of day, believing that the sky was "the key note, the standard of scale, and the chief organ of sentiment" in a landscape painting. In this habit he is known to have been influenced by the pioneering work of the meteorologist Luke Howard on the classification of clouds; Constable's annotations of his own copy of Researches About Atmospheric Phaenomena by Thomas Forster show him to have been fully abreast of meteorological terminology. "I have done a good deal of skying", Constable wrote to Fisher on 23 October 1821; "I am determined to conquer all difficulties, and that most arduous one among the rest".

Constable once wrote in a letter to Leslie, "My limited and abstracted art is to be found under every hedge, and in every lane, and therefore nobody thinks it worth picking up". He could never have imagined how influential his honest techniques would turn out to be. Constable's art inspired not only contemporaries like Géricault and Delacroix, but the Barbizon School, and the French impressionists of the late nineteenth century.

The inclusion of people from three generations acts as a reminder of the passage of time and of human mortality, while the church offers hope of salvation. Pensive figures in churchyards would have reminded contemporaries of Thomas Gray's famous poem, Elegy written in a Country Churchyard 1751.

Tis haytime & the red complexioned sun

Was scarcely up ere blackbirds had begun

Along the meadow hedges here & there

To sing loud songs to the sweet smelling air

Where breath of flowers & grass & happy cow

Fling oer ones senses streams of fragrance now

While in some pleasant nook the swain & maid

Lean oer their rakes & loiter in the shade

Or bend a minute oer the bridge & throw

Crumbs in their leisure to the fish below

---Hark at that happy shout---& song between

Tis pleasures birthday in her meadow scene

What joy seems half so rich from pleasure won

As the loud laugh of maidens in the sun.

_1826.jpg)

Large in scale, View on the Stour was one of a series of "six-foot" canvases, all representing his native land, produced for exhibition at the Royal Academy between 1819 and 1825. Constable rightly felt these works would secure his reputation as a landscape painter.

View on the Stour together with The Hay Wain was also shown in Paris in 1824, where their truthfulness to nature had an immediate impact on French artists of the period such as Eugene Delacroix, who repainted one of his works upon seeing Constable's pictures. The work was purchased by Mr. Huntington in 1925.

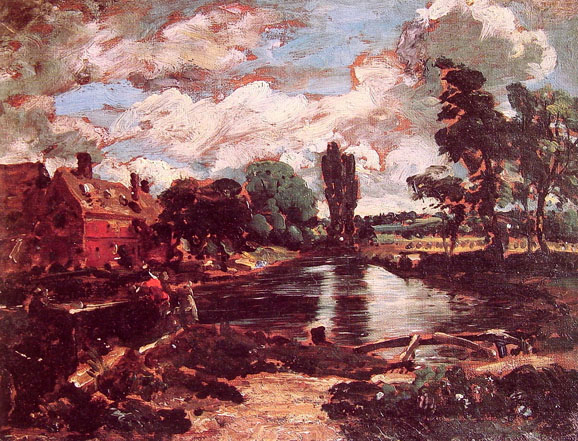

During the summer of 1810 or 1811 Constable painted a number of oil sketches of Flatford Mill, with minor variations. He portrayed the scene from the towpath beside Flatford Lock looking down the river, showing the mill on the left bank and the water meadows on the right, with haymakers at work. He depicted it looking directly into the light, with an expressive sky and sparkling reflections on the water.

Constable painted this sketch to explore his ideas while preparing an exhibition picture with the same composition, Flatford Mill from the lock (A water mill) which he showed at the Royal Academy in 1812. Michael Kitson has suggested that in using the sharply receding lines of the river to lead into the picture, Constable may have been influenced by the two Seaport subjects of the seventeenth-century French landscape painter, Claude Lorrain, in the collection of John Julius Angerstein, which Constable is known to have admired.

Leslie Parris and Ian Fleming-Williams note that an inscription on the back of this work indicates that Constable painted it in 1810 or 1811, and suggest that the second year is more likely.

Constable studied the work of great landscape artists who preceded him, such as Claude Lorrain, Salvator Rosa, Jacob van Ruisdael, Rembrandt, and Thomas Gainsborough. He also spent much time out of doors, working directly from nature, and adapted these open-air studies to fully worked paintings in the studio. Throughout his career he concentrated on a comparatively limited number of locations, producing many versions of particular areas in a variety of weather and atmospheric conditions.

This lock, located in Flatford in Suffolk, the county in which Constable was born, is the subject of many of his paintings. Some writers have stated that the sketchiness of this work indicates it was not 'finished', or was a study for another painting. However, the foreground in particular is fully worked and forms a striking contrast with the loosely painted background and the figure operating the lock.

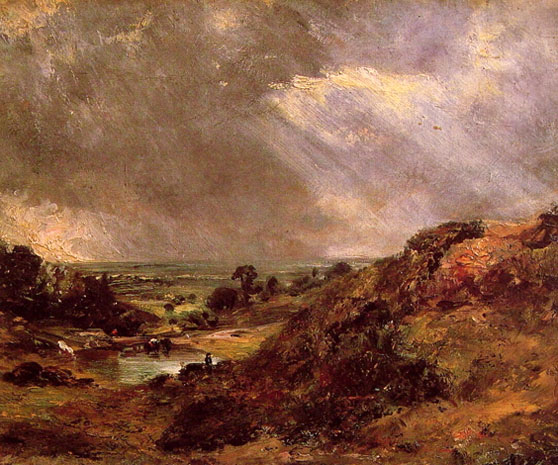

The artist meticulously observed and recorded cloud formations, weather conditions, and natural light effects; he believed an accurate rendering of these constantly shifting elements could transmit the vitality and freshness that was so important to his vision of the English countryside.

Constable's insistently overcast skies, with rain or the promise of rain, were distinctly British, and his treatment of them is how he distanced himself from the more temperate Italianate landscapes, seen in the golden glow of sky in paintings by Richard Wilson, Thomas Gainsborough, and John Martin also in this gallery that many still considered the ideal of natural beauty. The artist meticulously observed and recorded cloud formations, weather conditions, and natural light effects; he believed an accurate rendering of these constantly shifting elements could transmit the vitality and freshness that was so important to his vision of the English countryside.

Constable's insistently overcast skies, with rain or the promise of rain, were distinctly British, and his treatment of them is how he distanced himself from the more temperate Italianate landscapes, seen in the golden glow of sky in paintings by Richard Wilson, Thomas Gainsborough, and John Martin also in this gallery that many still considered the ideal of natural beauty.

Constable's description of East Bergholt appeared in the letterpress to the second edition of Lucas-Constable mezzotints, English Landscape:

East Bergholt, or as its Saxon derivation implies, 'Wooded Hill', is thus mentioned in 'The Beauties of England and Wales' … It is pleasantly situated in the most cultivated part of Suffolk, on a spot which overlooks the fertile valley of the Stour, which river divides that county on the south from Essex.

The beauty of the surrounding scenery, the gentle declivities, the luxuriant meadow flats sprinkled with flocks and herds, and well cultivated uplands, the woods and rivers, the numerous scattered villages and churches, with farms and picturesque cottages, all impart to this particular spot an amenity and elegance hardly anywhere else to be found .

East Bergholt is now a twin town with the village of Barbizon, in the Forest of Fontainebleau, France. Given that East Bergholt was Constable's birthplace, and that his work was much admired by Eugène Delacroix, Paul Huet, Jules Dupré, Théodore Rousseau and other artists associated with the area around Barbizon, this is a most appropriate association.

Constable shows a pair of barges travelling upstream. They are about to be disconnected from the towing-horse so that they can be poled under Flatford footbridge (just out of the composition to the left). Constable painted much of the picture on the spot in the summer of 1816.

Constable's pride in his family's successful and well-organized farm is evident. He depicted an ordered and harmonious landscape, and because of his personal connections and his deep affection for the place, he created an emotionally charged scene. But ultimately, this dynamic image transcends the personal and the local, as well as time and place.

This is one of two carefully detailed drawings that Constable may have exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1815.

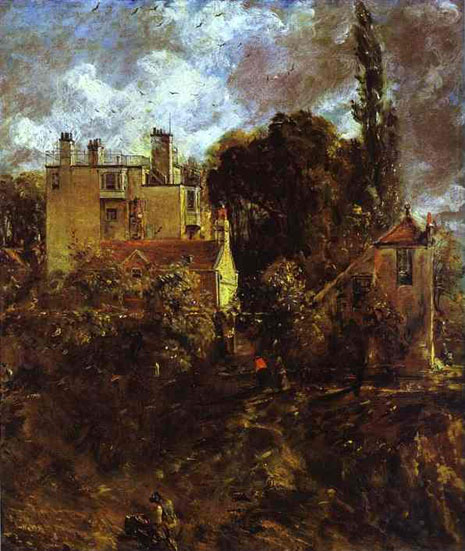

The composition originated in a minute drawing Constable made on a visit to Hadleigh in 1814, but was not developed until around the time of his wife's death in 1828. As an image of loneliness and decay, the subject suited his desolate state of mind. The paint is savagely worked across the canvas, contributing to the picture's highly expressive mood.

These small-scale coastal subjects in the Dutch manner were popular with collectors. A few years later Constable painted a composition of Yarmouth Jetty on the same format, and even used the same sky. He also made several versions of this composition.

_1820_25.jpg)

Lucas engraved the plate in 1831, basing it on the painting that Constable had exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1813 as Landscape: Boys Fishing. He made at least seven progress proof variations before the published state, of which this is the last. During the proofing the sky was reworked and the plants, birds and lights on the water were added.

Heysen wrote: 'I feel elated at the inclusion of … A lock on the Stour - This always appeals as a well knit & most complete design'.

Constable exhibited this first version of the subject at the Royal Academy in 1814 and at the British Institution in 1815, from where it was purchased by John Allnutt, a Clapham wine merchant and collector. As a result of this sale Constable was encouraged to pursue his career as a painter.

This half-length portrait depicts the wife of James Pulham, a local Suffolk attorney, dressed in elaborate finery befitting her status within the community. Mrs. Pulham's pyramidal form dominates the composition, with the voluminous fabric of her sleeves seeming to spill off the edge of the canvas and her gaze peering into the unseen distance. Whereas Constable has rendered the face, hair, and hat carefully, and captured the sitter's contemplative expression through attention to naturalistic details, he employs looser brushwork in his handling of the clothing and background. For instance, bravura passages of white paint evoke the shimmer of light on the satin dress. In a letter to Constable of April 30, 1818, Pulham acknowledged receipt of his wife's portrait and referred to it as "the Compliment which you have so handsomely bestowed on her."

The site has the romance of a long-abandoned seat of power, but it was notorious in 1830 as the seat of a 'rotten borough', targeted by radicals seeking parliamentary reform. Constable was by then passionately opposed to reform and the print was seen by at least one contemporary as a political protest.

Constable created a full-scale preparatory sketch for a finished work that is now in the Frick Collection, New York with the bishop in mind. Drawing upon his extensive repertoire of cloud studies, Constable replaced the earlier works' menacing skies with the white, puffy clouds preferred by his patron. The spire, freed from the original arch of tree branches, now soars unimpeded into the sky. The bishop, his wife, and their daughter appear at the left, where Fisher points toward the cathedral with his white cane.

Although frequently associated with the Romantic Movement, Constable strove to depict nature with more careful observation from life than his contemporaries. His ability to render the sense of direct experience and his bold brushwork inspired French contemporaries such as Eugène Delacroix and was an inspiration for artists of the Barbizon school and Impressionist movement.

After Constable's death, Stratford Mill acquired its more familiar title, 'The Young Waltonians', a reference to Izaak Walton, author of 'The Compleat Angler'.

The painting was exhibited several times during Constable's lifetime, first at the Royal Academy in 1826.

Constable depicted the view along a valley with water in the foreground, where a cow is drinking, tall trees to the left and the farmhouse beside the church tower on a hill to the right. He based the farmhouse on a small oil sketch from nature he had made around 1811-15, Church Farm, Langham. The sketch does not include Langham Church. Although it has been suggested that the church would have been out of sight behind the farmhouse when viewed from this angle, Anne Lyles has recently shown the author that this is not the case. The image of Glebe Farm was a favorite with Constable, and he painted four versions between 1826 and 1830.

Constable wrote to the Bishop's nephew, John Fisher, on 9 September 1829 about his first version of The Glebe Farm 1826-27: 'My last landscape is a cottage scene - with the Church of Langham - the poor bishops first living … It is one of my best - very rich in colour - & fresh and bright - and I have "pacified it" - so that it gains much by that tone & solemnity'.

This second version of The Glebe Farm once belonged to Constable's friend and biographer, C.R. Leslie. Leslie told Constable that he liked it so much he did not think it needed another touch, and Constable gave it to him in early 1830 with the foliage, tree trunks and other details 'unfinished'. Constable had painted in the pitcher beside the pool, but not the country girl who would have been there to fill it and who appears in the third version. The tall thin tree in the foreground is not present in other versions of the subject.

On 8 December 1836 Constable wrote to Leslie: 'This is one of the pictures on which I rest my little pretensions to futurity'.

Constable depicted a traditional farming community harvesting wheat, with harvesters, gleaners, a boy with a dog and a distant ploughman. The woman and two girls in the foreground are poor, gleaning the ears of wheat missed by the reapers. The boy with the dog is guarding the workers' food and drink, draped in discarded clothes to provide shade from the sun. Constable presented life before the changes that occurred in rural society with the enclosure of the common fields in 1816 - before the poor had been largely barred from taking part in their age-old practice of gleaning.

Constable exhibited this painting at the Royal Academy in 1816 and at the British Institution the following year, when he included with the catalogue entry lines from Robert Bloomfield's The Farmer's Boy (1800):

Nature herself invites the reapers forth;

No rake takes here what heaven to all bestows:

Children of want, for you the bounty flows!

His inclusion of this text suggests that Constable too believed that the rural poor, in this instance the gleaners, were deserving of nature's bounty.

This study is based on the oil sketch. The ferry shown, which plied between the bank of the mill stream by the house and the far bank of the River Stour, is taken from a sketchbook drawing. The work was engraved for English Landscape in 1831.

A parapet surmounted by urns appears in the foreground, acting as a repoussoir, or device for projecting the eye deep into the composition. Above the bridge Constable portrays a rare atmospheric condition which he described thus: 'when the spectator stands with his back to the sun, the rays may be seen converging…towards…the horizon'.

In October 1816 Constable went to Osmington near Weymouth for his honeymoon; the idea for the painting probably dates from this period. A larger version called Osmington Shore was exhibited by him at the British Institution in 1819.

Source: Art Renewal Center

Source: John Constable

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.