English Rococo Artist

1727 - 1788

Gainsborough was born in Sudbury, Suffolk, England. His father was a weaver involved with the wool trade. At the age of thirteen he impressed his father with his penciling skills so that he let him go to London to study art in 1740. In London he first trained under engraver Hubert Gravelot but eventually became associated with William Hogarth and his school. One of his mentors was Francis Hayman. In those years he contributed to the decoration of what is now the Thomas Coram Foundation for Children and the supper boxes at Vauxhall Gardens.

In the 1740's, Gainsborough married Margaret Burr, an illegitimate daughter of the Duke of Beaufort, who settled a 200 Pounds annuity on the couple. The artist's work, then mainly composed of landscape paintings, was not selling very well. He returned to Sudbury in 1748-1749 and concentrated on the painting of portraits.

In 1752, he and his family, now including two daughters, moved to Ipswich. Commissions for personal portraits increased, but his clientele included mainly local merchants and squires. He had to borrow against his wife's annuity.

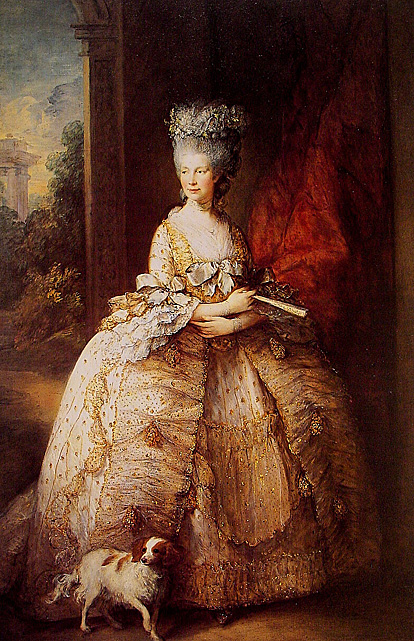

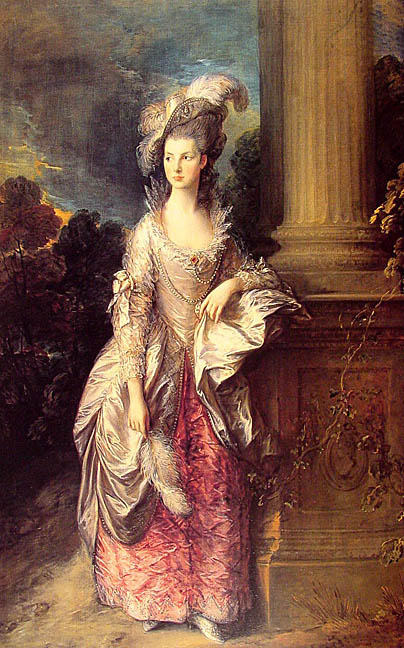

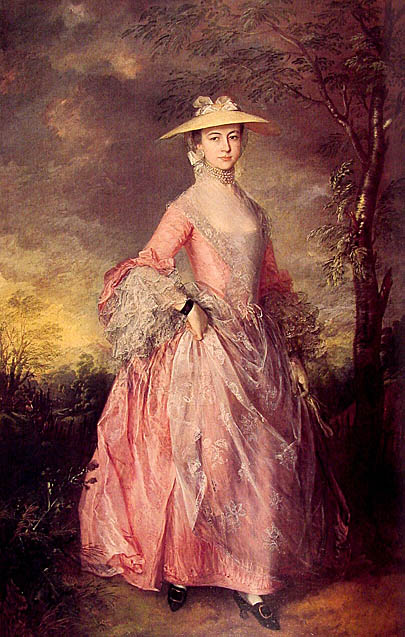

In 1759, Gainsborough and his family moved to Bath. There, he studied portraits by van Dyck and was eventually able to attract a better-paying high society clientele. In 1761, he began to send work to the Society of Arts exhibition in London (now the Royal Society of Arts, of which he was one of the earliest members); and from 1769 on, he submitted works to the Royal Academy's annual exhibitions. He selected portraits of well-known or notorious clients in order to attract attention. These exhibitions helped him acquire a national reputation, and he was invited to become one of the founding members of the Royal Academy in 1769. His relationship with the academy, however, was not an easy one and he stopped exhibiting his paintings there in 1773.

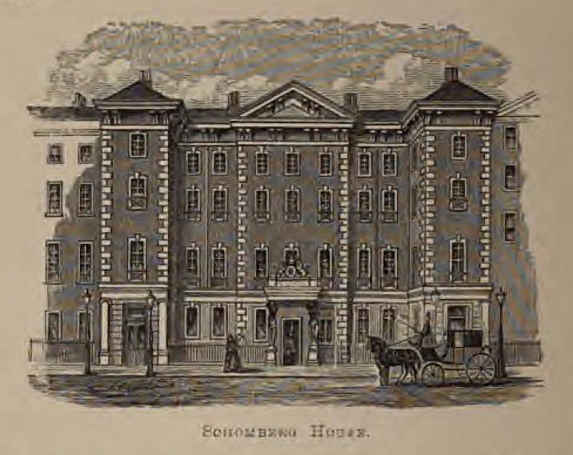

In 1774, Gainsborough and his family moved to London to live in Schomberg House, Pall Mall. In 1777, he again began to exhibit his paintings at the Royal Academy, including portraits of contemporary celebrities, such as the Duke and Duchess of Cumberland. Exhibitions of his work continued for the next six years.

_1781.jpg)

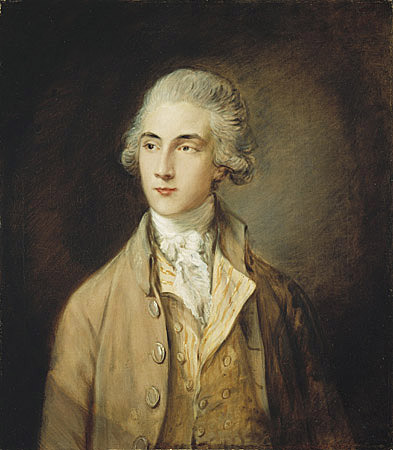

Hervey was Member of Parliament for Bury St Edmunds from 1757 to 1763, and, after being for a short time Member for Saltash, again represented Bury St Edmunds from 1768 until he succeeded his brother in the Earldom of Bristol in 1775.

He often took part in debates in Parliament, and was a frequent contributor to periodical literature. Having served as a Lord of the Admiralty from 1771 to 1775 he won some notoriety as an opponent of the Rockingham ministry and a defender of Admiral Keppel. In August 1744 he had been secretly married to Elizabeth Chudleigh (1720-1788), afterwards Duchess of Kingston, but this union was dissolved in 1769. Lord Bristol died leaving no legitimate issue, and having, as far as possible, alienated his property from the title. He was succeeded by his brother.

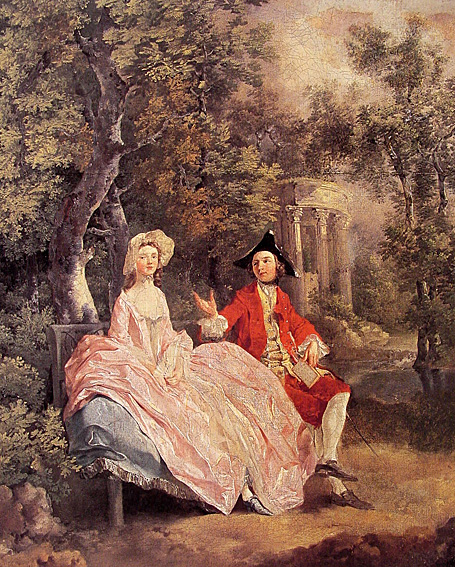

The open-air portrait is a familiar theme in the English school, whereas in eighteenth-century France the portrait is usually in an interior. The evocation of nature by the English portrait painters is on the whole conventional; it is quite another matter with Gainsborough, however, who has treated the landscape for its own sake.

In 1780, he painted the portraits of King George III and his Queen and afterwards received many royal commissions. This gave him some influence with the Academy and allowed him to dictate the manner in which he wished his work to be exhibited. However, in 1783, he removed his paintings from the forthcoming exhibition and transferred them to Schomberg House.

In 1784, royal painter Allan Ramsay died and the King was obliged to give the job to Gainsborough's rival and Academy president, Joshua Reynolds, however Gainsborough remained the Royal Family's favorite painter. At his own express wish, he was buried at Saint Anne's Church, Kew, where the Family regularly worshipped.

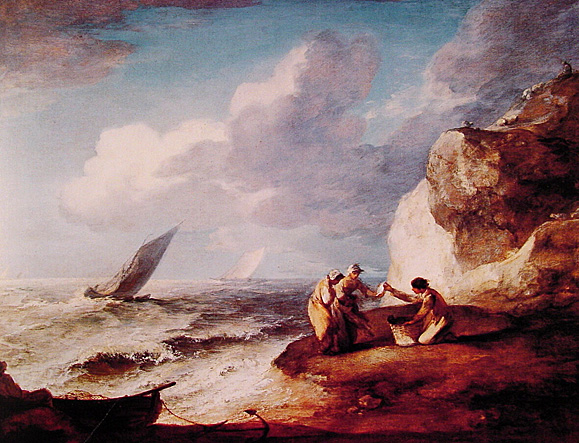

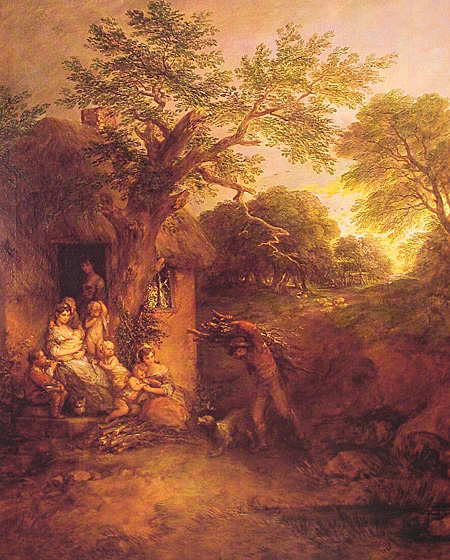

In his later years, Gainsborough often painted relatively simple, ordinary landscapes. With Richard Wilson, he was one of the originators of the eighteenth-century British landscape school; though simultaneously, in conjunction with Joshua Reynolds, he was the dominant British portraitist of the second half of the 18th century.

Gainsborough painted more from his observations of nature (and human nature) than from any application of formal academic rules. The poetic sensibility of his paintings caused Constable to say, "On looking at them, we find tears in our eyes and know not what brings them." He himself said, "I'm sick of portraits, and wish very much to take my viol-da-gam and walk off to some sweet village, where I can paint landskips (sic) and enjoy the fag end of life in quietness and ease."

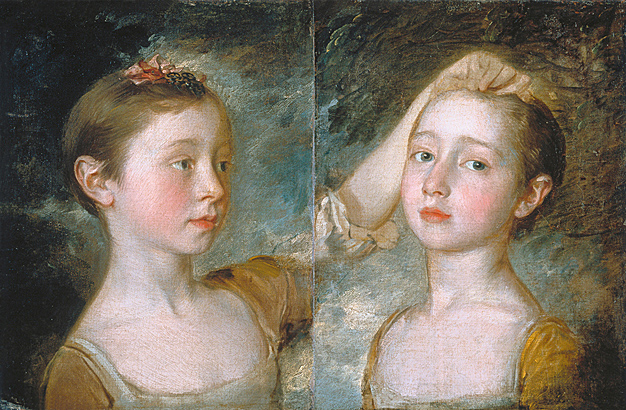

His most famous works, such as Portrait of Mrs. Graham; Mary and Margaret: The Painter's Daughters; William Hallett and His Wife Elizabeth, nee Stephen, known as The Morning Walk; and Cottage Girl with Dog and Pitcher, display the unique individuality of his subjects.

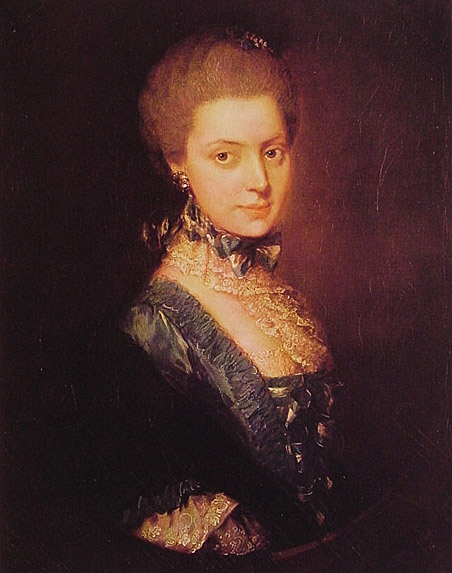

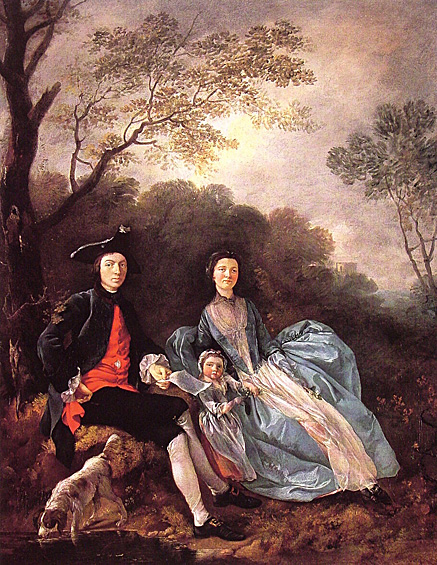

The portrait was probably painted in Ipswich in the mid-1750's and left unfinished.

In his early years in Sudbury, after his training in London restoring Dutch landscapes and working with a French engraver, Gainsborough's finish was less free. After moving to the resort town of Bath in about 1759, he found a metropolitan clientele, and discovered Van Dyck in country-house collections. Both were to be decisive, and the effects are best judged in his portraits of women sitters, on the scale of life, in which elegance and ease of manner combine with a new, more tender color range and a loosening of paint texture. In 1774 he moved permanently to London, where he built up a great portrait practice, but also began to paint imaginative 'fancy pictures' inspired by Murillo. He never aspired to 'history painting' in the Grand Manner. His poetry resides mainly in his brush, not in compositional inventiveness.

It was surely Gainsborough's own inclination, however, to interpret a formal marriage portrait, for which the sitters probably sat separately, as a parkland promenade. William Hallett was 21 and his wife Elizabeth, nee Stephen, 20 when they solemnly linked arms to walk in step together through life. A Spitz dog paces at their side, right foot forward like theirs, as pale and fluffy as Mrs Hallet is pale and gauzy. Being only a dog with no sense of occasion he pants joyfully hoping for attention. The parkland is a painted backdrop, like those of Victorian photographers, yet it provides a pretext for depicting urban sitters in urban finery as if in the dappled light of a world fresh with dew.

The Portrait of James Christie hung in a place of honor at Christie's auction house in London until it was sold in 1846. The auction house was a gathering place for collectors, dealers, and fashionable society. The portrait immortalized the auctioneer and perpetuated his association with Gainsborough, who was one of England's most famous portrait painters.

In 1754 he went to Italy where he studied counterpoint under Giovanni Battista Martini, and from 1760 to 1762 held the post of organist at Milan cathedral, for which he wrote two Masses, a Requiem, a Te Deum and other works. Around this time he converted from Lutheranism to Catholicism.

He was the only one of Johann Sebastian's sons to write opera in Italian, starting with arias inserted into the operas of others, then pasticcios , the Teatro Regio in Turin commissioned him to write Artaserse, an opera seria that was premiered in 1760. This led to more opera commissions, leading to commissions for the King's Theatre in London, an invitation in 1762 to go there, where he spent the rest of his life. Thus, he is often referred to as the "London Bach". The Milan Cathedral kept his position open, hoping he would return.

For twenty years he was the most popular musician in England. His dramatic works, produced at the King's theatre, were received with great cordiality. The first of these, Orione, was one of the first few musical works to use clarinets. He was appointed music master to the Queen, and his duties included giving music lessons to her and her children, and accompanying on piano, the King playing flute. His concerts, given in partnership with Abel at the Hanover Square rooms, soon became the most fashionable of public entertainments.

During his first years in London, Bach made friends with a very young but very promising musician, Mozart, who was there as part of the endless tours arranged by his father Leopold for the purpose of displaying him as a child prodigy. Many scholars judge that J. C. Bach was one of the most important influences on Mozart, who learned from him how to produce a brilliant and attractive surface texture in his music. This influence can be seen directly in the opening of Mozart's piano sonata in B?flat (KV 315c, the Linz sonata from 1783 - 1784) which very closely resembles that of two sonatas of Bach's which Mozart would have known; and indirectly in Bach's attempt in an early sonata (the C minor piano sonata of the opus 5 set) to more effectively combine the gallant style of his day with fugal music.

Johann Christian Bach died in London on the first day of 1782. Mozart said in a letter to his father that it was "a loss to the musical world".

Fischer was a composer and virtuoso oboist. His two-keyed oboe is visible on the harpsichord-cum-piano against which the musician leans. Fanny Burney praised the 'sweet-flowing, melting celestial notes of Fischer's hautboy,' but the Italian violinist Felice de' Giardini (1716-93) referred to Fischer's 'impudence of tone as no other instrument could contend with.' In the portrait on the chair behind Fischer is a violin, on which he was apparently also an accomplished performer although only in private. The harpsichord-cum-piano, made by Joseph Merlin who came to London from the Netherlands in 1760 and established a successful business in the production of pianofortes, presumably refers to his abilities as a composer, as no doubt do the piles of musical scores.

This portrait of Johann Christian Fischer stands as testimony to Gainsborough's own love of music. The artist preferred the company of actors, artists, dramatists and musicians to that of politicians, writers or scholars, and was himself a talented amateur musician in addition to being a painter. Gainsborough once wrote to William Jackson: 'I'm sick of Portraits and wish very much to take my Viol da Gamba and walk off to some sweet Village when I can paint Landskips and enjoy the fag End of Life in quietness and ease.' Yet some of his finest portraits are of musicians and include, in addition to that of Fischer, the composer Karl Friedrich Abel (San Marino, Henry E. Huntington Library and Art Gallery) and Johann Christian Bach (Bologna, Museo Civico, Bibliografico Musicale). These two portraits date from the late 1770s, whereas that of Johann Christian Fischer was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1780.

Gainsborough seems to have known Fischer while he was still living in Bath (Fischer moved permanently to London in 1774). As early as 1775 Fischer evinced an interest in the artist's elder daughter Mary (1748-1826), whom he married at Saint Ann's Church, Soho, on 21 February 1780. The wedding was agreed to reluctantly by Gainsborough, who, although he admired Fischer as a musician, perhaps hoped that his elder daughter might make a better marriage, and lodged doubts about the musician's character. He wrote to his sister on 23 February 1780: 'I can't say I have any reason to doubt the man's honesty or goodness of heart, as I never heard anyone speak anything amiss of him; and as to his oddities and temper, she must learn to like as she likes his person, for nothing can be altered now. I pray God she may be happy with him and have her health.' The marriage did not last and Mary gradually became insane. Whatever tensions Gainsborough might have been experiencing with regard to Fischer's relationship with his daughter, Gainsborough's portrait is masterly in its compositional sophistication, use of color and sympathetic characterization. It is clear, however, that the likeness has been painted over another portrait which will no doubt be revealed by X-ray. The portrait came into the Royal Collection indirectly. It appears to have been painted for Willoughby Bertie, 4th Earl of Abingdon (died 1799), a radical politician and a talented amateur musician, but was sold by his successor. Eventually it was acquired by Ernest, Duke of Cumberland, who in 1809 presented it to his brother, the Prince of Wales (later George IV). Both were admirers of Gainsborough's work.

He served with Prince Ferdinand of Brunswick during the Seven Years' War, and was appointed a captain in the 1st Regiment of Foot Guards. In 1763, he was appointed a royal aide-de-camp, and from 1763 until 1765, he was secretary to the embassy at Madrid. On 12 November 1764, he was appointed a Groom of the Bedchamber to the Duke of Gloucester.

On 6 December 1766, he married Penelope Pitt, daughter of George Pitt, 1st Baron Rivers. Her wanton intrigue with Vittorio Amadeo, Count Alfieri, provoked a duel between her husband and her lover on 7 May 1771, and Ligonier was able to obtain a divorce by Act of Parliament on 7 November 1771. He married Lady Mary Henley, daughter of Robert Henley, 1st Earl of Northington, on 14 December 1773. In the meantime, upon the death of his uncle, the Earl Ligonier in 1770, he became Viscount Ligonier, of Clonmell, which title had been created with a special remainder to him.

He was promoted major general in 1775 and lieutenant general in 1777. On 19 July 1776, he was created Earl Ligonier, of Clonmell, in the Peerage of Ireland. The last honor conferred upon him was an appointment as a Knight Companion of the Order of the Bath, on 17 December 1781. He died on 14 June 1782, before he could be installed, and left no posterity.

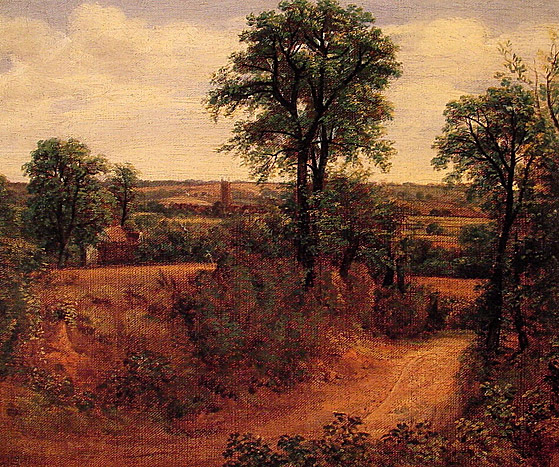

This kind of picture, commissioned by people 'who lived in rooms which were neat but not spacious', in Ellis Waterhouse's happy phrase about Gainsborough's contemporary Arthur Devis, was a speciality of painters who were not 'out of the top drawer'. The sitters, or their mannequin stand-ins, are posed in 'genteel attitudes' derived from manuals of manners. The nonchalant Mr Andrews, fortunate possessor of a game license, has his gun under his arm; Mrs Andrews, ramrod straight and neatly composed, may have been meant to hold a book, or, it has been suggested, a bird which her husband has shot. In the event, a reserved space left in her lap has not been filled in with any identifiable object.

Out of these conventional ingredients Gainsborough has composed the most tartly lyrical picture in the history of art. Mr Andrews's satisfaction in his well-kept farmlands is as nothing to the intensity of the painter's feeling for the gold and green of fields and copses, the supple curves of fertile land meeting the stately clouds. The figures stand out brittle against that glorious yet ordered bounty. But how marvelously the acid blue hooped skirt is deployed, almost, but not quite, rhyming with the curved bench back, the pointy silk shoes in sly communion with the bench feet, while Mr Andrews's substantial shoes converse with tree roots. (The faithful gun dog had better watch out for his unshod paws.) More rhymes and assonances link the lines of gun, thighs, dog, calf, coat; a coat tail answers the hanging ribbon of a sun hat; something jaunty in the husband's tricorn catches the corner of his wife's eye. Deep affection and naive artifice combine to create the earliest successful depiction of a truly English idyll.

Everything is natural. With loose hair, in loose natural clothing (no corsets or hip bolsters) she is seated on a bench of shrubby rock. Around her, there's a landscape that declares itself as free and uncultivated Nature. A woman of feeling, she is at one with it in spirit and in body.

There's one very conspicuous point of junction. The woman sits under a softly bending tree whose leaves surround her head. A breeze gusts through the scene. Her fluttering locks are given an almost identical profile to the waving foliage that frames them. It is a pictorial simile, likening her blowing hair with the tree's own tresses, linking her mind with the movements of nature. And what species of tree might that be? Don't bother asking. It is merely a generic tree, "some sort of tree". It's not alone. What material is the dress made of? Hair, leaves, cloth, grass, distant clump of sheep - nothing has a definite character.

All is vague - and all is a blur. The way Gainsborough puts his paint on is designed to break down barriers. He fades the hair and the leaves at their edges, blends their textures, and softens all the physical differences between them.

Likewise, the strands of grass in the foreground are echoed by the streaky highlights in the dress - but actually the two phenomena are indistinguishable. The sloping curving skirt is likened to the rising ground in the middle distance, but again there is nothing but their color to tell these two streaky, shimmery areas apart. All is rendered in soft, fluent, semi-transparent flecks and flickers.

The picture is a tissue of similes and echoes, but it's more than that. It doesn't say: A is like B, but of course A is also significantly unlike B. What it says is: A is like B, in fact A is virtually the same as B. At every point, the vagueness of forms and the breakdown of the paint make sure that specifics do not obtrude and distinctions do not arise. Each likeness is an equation. Any counterpoint of differences is suppressed.

Everything diffuses and interfuses - nature, body and mind. The peach of her dress crops up in the leaves and grasses around her, and their greens enter into her shadows, just as the ruffling wind can be imagined to spread and mingle the scents of woman and nature. And this breeze is especially embodied in her gauzy veil as it delicately wafts around her and then dissolves into airy invisibility.

The circulating air provides a natural explanation for the general softening and blurring together of things. It's also the woman's "air", her demeanor, her passionate but dreamy mood, that emanates from her and encircles her, and which blends in turn into the atmosphere of the natural world.

.jpg)

Gainsborough holds in his hand a paper, perhaps once showing a sketch, but now transparent with age, as is the figure of the child. It has been presumed that she must be the Gainsborough's' eldest surviving daughter Mary, born shortly before February 1750.

However, both the style of the background and the evident difficulties Gainsborough had with the proportions of the rather stiff-limbed figures suggest a date closer to 1747-48, when Gainsborough was still working in London. The child may, therefore, be the Gainsborough's' first-born but short-lived daughter, also named Mary, who died in 1748. Her date of birth is so far untraced, but the child in the picture would seem to be around eighteen months old.

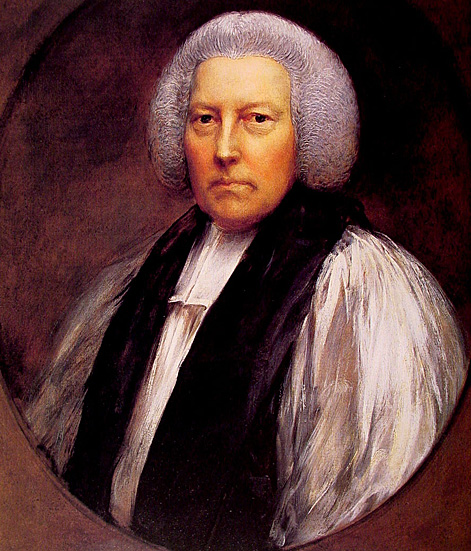

In the 1780's Hurd assisted in drawing up the program for Benjamin West's series of paintings illustrating the history of revealed religion for the King's new private chapel at Windsor, a project never realized. According to Horace Walpole, Hurd was 'a gentle, plausible man affecting a singular decorum that endeared him highly to devout old ladies'. In Gainsborough's portrait the ground is left visible in the surround and in the loosely painted white rochet but the confident gaze is from a well-defined face.

The most personal response to Watteau is in Gainsborough, a great painter who yet seldom painted anything resembling a Watteau subject. Several of Gainsborough's early portraits show him utilizing Watteau's compositions for his sitters. But Gainsborough borrows more than a pose, as his later pictures confirm. It is freedom that exhales from his portraits: the freedom of nature and natural settings is allied to free handling, and the whole expresses the idiosyncratic character of his sitters, so relaxed and yet lively, just like Gainsborough's own nature. The painter who described himself in a letter to a patron as 'but a wild goose at best' was dearly Watteau's cousin, taking the same freedom for the artist as he expressed in his art, and conscious of being the odd man out in ordinary society. Gainsborough, if anyone, was the heir to Watteau's art, but he was not to turn to the 'fancy picture' until late in life; and there would have been little patronage for an English painter producing fetes galantes in preference to portraits.

_ca_1770.jpg)

It has been said that Gainsborough painted the portrait mainly to prove to his chief rival Joshua Reynolds that it was possible to use blue as the central color of a portrait, but this statement has been discredited: the rumor began circulating after Gainsborough's death and Reynolds had painted portraits in blue long before.

The painting was in Jonathan Buttall's possession until he filed for bankruptcy in 1796. It was bought first by the politician John Nesbitt and then, in 1802, by the portrait painter John Hoppner. In about 1809 The Blue Boy entered the collection of the Earl Grosvenor and remained with his descendants until its sale by the second Duke of Westminster to the dealer Joseph Duveen in 1921. In a move that caused a public outcry in Britain, it was then sold on to the American railway pioneer Henry Edwards Huntington for $182,200 (then a record price for any painting) (According to a mention in the New York Times, dated Nov. 11, 1921, the purchase price was $640,000). Before its departure to California in 1922, The Blue Boy was briefly put on display at the National Gallery where it was seen by 90,000 people; the Gallery's director Charles Holmes was moved to scrawl "Au revoir" on the back of the painting.

Gainsborough's only known assistant was his nephew, Gainsborough Dupont.

He died of cancer on 2 August 1788 at the age of 61.

Source: Art Renewal Center

Source: Web Gallery of Art

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.