Disclaimer

Peter Paul Rubens

Baroque Painter and Diplomat

1577 - 1640

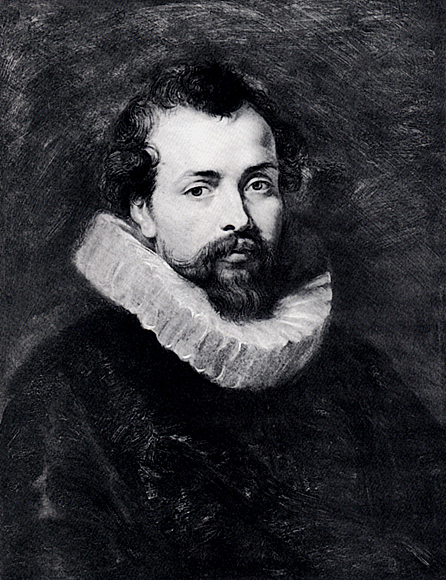

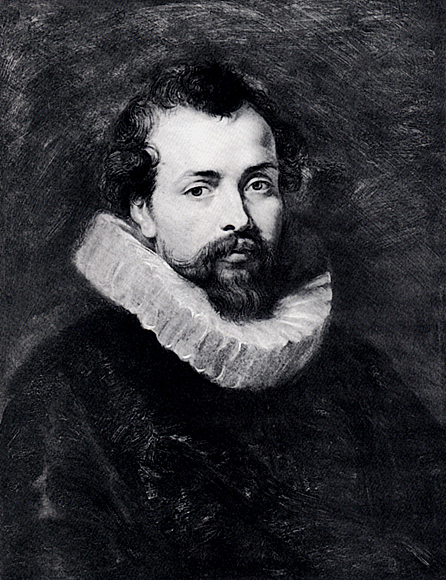

Self Portrait of Peter Paul Rubens

Peter Paul Rubens was a prolific seventeenth-century Flemish and European painter, and a proponent of an exuberant Baroque style that emphasized movement, color, and sensuality. He is well-known for his Counter-Reformation altarpieces, portraits, landscapes, and history paintings of mythological and allegorical subjects.

In addition to running a large studio in Antwerp which produced paintings popular with nobility and art collectors throughout Europe, Rubens was a classically-educated humanist scholar, art collector, and diplomat who was knighted by both Philip IV, King of Spain, and Charles I, King of England.

Rubens was born in Siegen, Westphalia, to Jan Rubens and Maria Pypelincks. His father, a Calvinist, and mother fled Antwerp for Cologne in 1568, after increased religious turmoil and persecution of Protestants during the rule of the Spanish Netherlands by the Duke of Alba. Jan Rubens became the legal advisor (and lover) to Anna of Saxony, the second wife of William I of Orange, and settled at her court in Siegen in 1570. Following imprisonment for the affair, Peter Paul Rubens was born in 1577. The family returned to Cologne the next year. In 1589, two years after his father's death, Rubens moved with his mother to Antwerp, where he was raised Catholic. Religion figured prominently in much of his work and Rubens later became one of the leading voices of the Catholic Counter-Reformation style of painting.

In Antwerp Rubens received a humanist education, studying Latin and classical literature. By fourteen he began his artistic apprenticeship with Tobias Verhaeght. Subsequently, he studied under two of the city's leading painters of the time, the late mannerists Adam van Noort and Otto van Veen. Much of his earliest training involved copying earlier artists' works, such as woodcuts by Hans Holbein the Younger and Marcantonio Raimondi's engravings after Raphael. Rubens completed his education in 1598, at which time he entered the Guild of St. Luke as an independent master.

In 1600, Rubens traveled to Italy. He stopped first in Venice, where he saw paintings by Titian, Veronese, and Tintoretto, before settling in Mantua at the court of Duke Vincenzo I of Gonzaga. The coloring and compositions of Veronese and Tintoretto had an immediate effect on Rubens's painting, and his later, mature style was profoundly influenced by Titian. With financial support from the duke, Rubens traveled to Rome by way of Florence in 1601. There, he studied classical Greek and Roman art and copied works of the Italian masters. The Hellenistic sculpture Laocoon and his Sons was especially influential on him, as was the art of Michelangelo, Raphael and Leonardo da Vinci. He was also influenced by the recent, highly naturalistic paintings by Caravaggio. He later made a copy of that artist's Entombment of Christ, recommended that his patron, the Duke of Mantua, purchase The Death of the Virgin (Louvre), and was instrumental in the acquisition of The Madonna of the Rosary (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna) for the Dominican Church in Antwerp. During this first stay in Rome, Rubens completed his first altarpiece commission, St. Helena with the True Cross for the Roman Church, Santa Croce in Gerusalemme.

The Duke of Lerma

In 1603 Flemish painter Peter Paul Rubens traveled to Spain as part of a diplomatic mission. While there, he received a commission for this portrait of the Duke of Lerma, the powerful prime minister of Spanish king Philip III. The painting now hangs in the Prado Museum in Madrid, Spain.

Emperor Charles V

Allegory on Emperor Charles V as Ruler of Vast Realms

While Rubens was court painter to Duke Vincenzo Gonzaga, he was sent on a diplomatic mission to Spain in 1603- 1604. This was probably Rubens' first encounter with the powerful and magnificent position of the Habsburg dynasty and the Habsburg rulers at their principal residence. He perceived Charles V as the founder of the imperial and dynastic power of this family which he held in high respect. Rubens applied himself to the study of Titian's (1477- 1576) portraits of the emperor. Shortly after his return from Spain to Italy, he executed this portrait of the emperor, which he modelled on a painting by Parmigianino (1503- 1540) in the ducal collection. Rubens created a large-scale composition of geometric and stereometric forms. The emperor is depicted in ceremonial armour, with the Order of the Golden Fleece and his imperial insignia: crown, sceptre, sword and globe, the latter being the symbol of his extensive dominions. The mitre crown depicted in the painting is consistent with the form of the private crowns of the Habsburgs.

Rubens traveled to Spain on a diplomatic mission in 1603, delivering gifts from the Gonzagas to the court of Philip III. While there, he viewed the extensive collections of Raphael and Titian that had been collected by Philip II. He also painted an equestrian portrait of the Duke of Lerma during his stay (Prado, Madrid) that demonstrates the influence of works like Titian's Charles V at Muhlberg (1548; Prado, Madrid). This journey marks the first of many during his career that would combine art and diplomacy.

Marchesa Brigida Spinola-Doria

On at least four occasions during his long stay in Italy, Rubens worked in Genoa, a wealthy seaport. This proud Genoese aristocrat, by birth a Spinola, married Giacomo Massimiliano Doria in 1605. Painted at the age of twenty-two in the year following her marriage, the marchesa wears a magnificent silvery satin dress that may be her wedding gown.

Following the sixteenth-century Venetian master Titian, Rubens built up layer upon layer of translucent glazes and added free strokes of thick highlights. In contrast to this loose brushwork in the gleaming white gown and crimson drapery, the tight Flemish technique Rubens had practiced in his native Flanders defines the carefully detailed face, intricately jeweled coiffure, and spectacular lace collar.

Rubens' preliminary drawing and a print made after this painting indicate that the National Gallery's portrait is only a fragment. Initially the figure was full-length, and the architecture receded to an open landscape. Sometime after 1854 the canvas was cut down, possibly because its edges had been damaged.

He returned to Italy in 1604, where he remained for the next four years-first in Mantua, and then in Genoa and Rome. In Genoa, Rubens painted numerous portraits, such as the Marchesa Brigida Spinola-Doria (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.), in a style that would influence later paintings by Anthony van Dyck, Joshua Reynolds, and Thomas Gainsborough. He also began a book illustrating the palaces in the city. From 1606 to 1608, he was largely in Rome. During this period Rubens received his most important commission to date for the high altar of the city's most fashionable new church, Santa Maria in Vallicella (or, Chiesa Nuova). The subject was to be St. Gregory the Great and important local saints adoring an icon of the Virgin and Child. The first version, a single canvas (Musee des Beaux-Arts, Grenoble), was immediately replaced by a second version on three slate panels that permits the actual miraculous holy image of the "Santa Maria in Vallicella" to be revealed on important feast days by a removable copper cover, also painted by the artist.

The impact of Italy on Rubens was great. Besides the artistic influences, he continued to write many of his letters and correspondences in Italian for the rest of his life, signed his name as "Pietro Paolo Rubens", and spoke longingly of returning to the peninsula-a hope that never materialized.

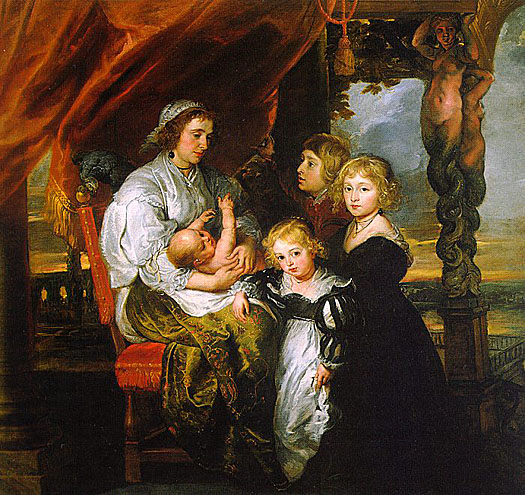

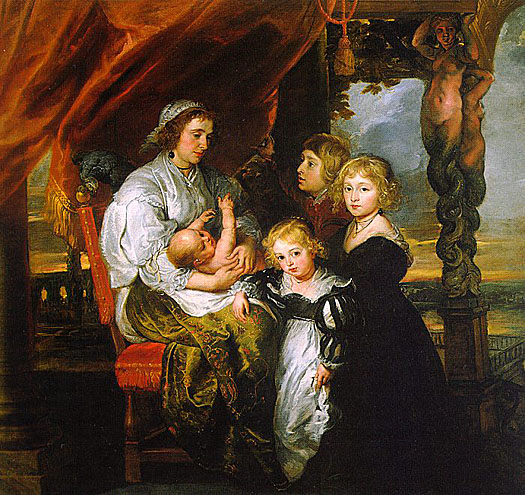

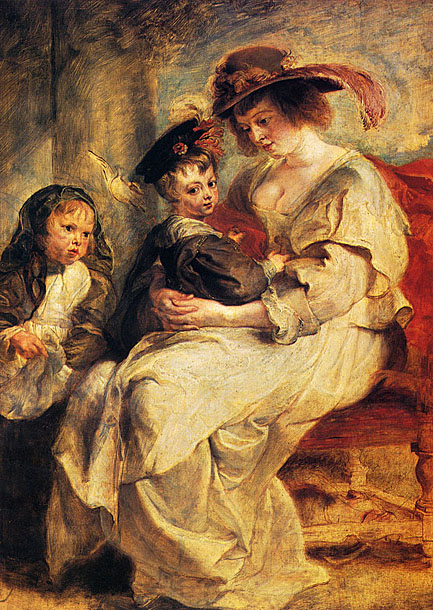

Upon hearing of his mother's illness in 1608, Rubens planned his departure from Italy for Antwerp. However, she died before he made it home. His return coincided with a period of renewed prosperity in the city with the signing of Treaty of Antwerp in April 1609, which initiated the Twelve Years' Truce. In September of that year Rubens was appointed court painter by Albert and Isabella, the Governors of the Low Countries. He received special permission to base his studio in Antwerp, instead of at their court in Brussels, and to also work for other clients. He remained close to the Archduchess Isabella until her death in 1633, and was called upon not only as a painter but also as an ambassador and diplomat. Rubens further cemented his ties to the city when, on October 3, 1609, he married Isabella Brant, the daughter of a leading Antwerp citizen and humanist Jan Brant.

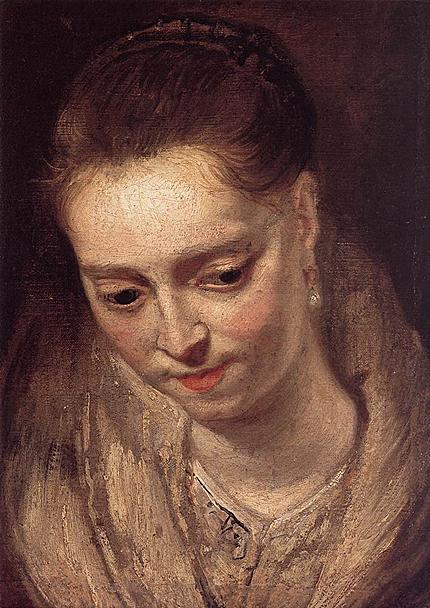

Isabella Brandt and Self Portrait of Rubens: 1610

Isabella Brandt: ca 1626

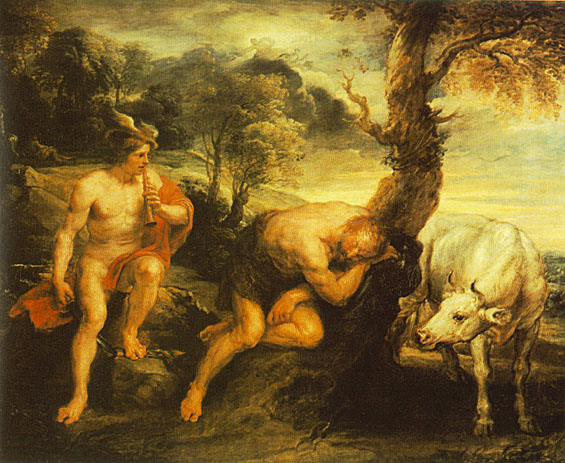

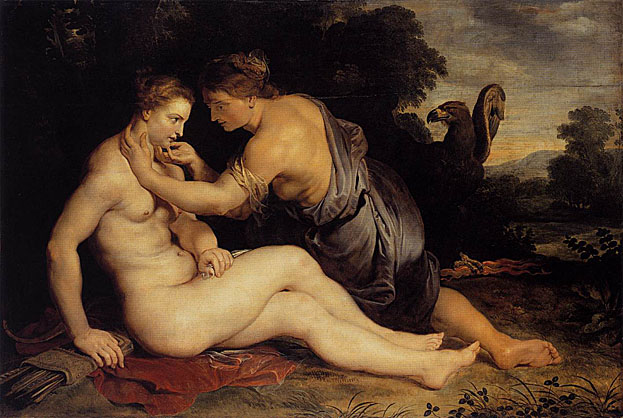

In 1610, Rubens moved into a new house and studio that he designed. Now the Rubenshuis Museum, the Italian-influenced villa in the center of Antwerp contained his workshop, where he and his apprentices made most of the paintings, and his personal art collection and library, both among the most extensive in Antwerp. During this time he built up a studio with numerous students and assistants. His most famous pupil was the young Anthony van Dyck, who soon became the leading Flemish portraitist and collaborated frequently with Rubens. He also frequently collaborated with the many specialists active in the city, including the animal painter Frans Snyders, who contributed to the eagle to Prometheus Bound (illustrated left), and his good friend the flower-painter Jan Brueghel the Elder.

Anthony van Dyck - Self Portrait

Prometheus Bound: 1610

The piece Prometheus Bound is based upon the mythological story of the Titan Prometheus who stole fire from the gods to give to mankind. This work, which was completed in 1612, has a very interesting and diverse history.

Flemish baroque painter Peter Paul Rubens was born June 28, 1577. By the age of 21 Rubens had become a master painter. At 21, Rubens traveled to Italy to continue his education. It was in Venice where he saw the radiant colors and majestic forms of Titian that influenced the style we see in his Prometheus work. Prometheus Bound was painted between 1611 and 1612. The more I look at this painting the more I like it but the stranger it becomes. The painting is of an almost naked man chained to a rock and fighting an eagle that is pecking out his liver. This piece symbolizes Baroque art at its purest. Most of the qualities associated with the Baroque are present in this painting. The painting is very dramatic in its portrayal of this struggle between Prometheus and the eagle. When I look at the eagle's face I think it is grinning as if it were enjoying ripping out the liver of Prometheus.

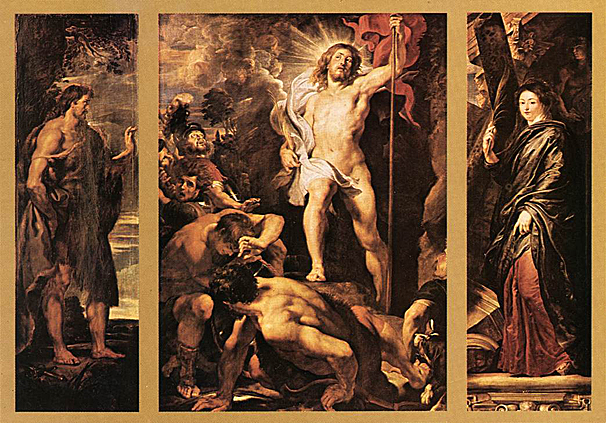

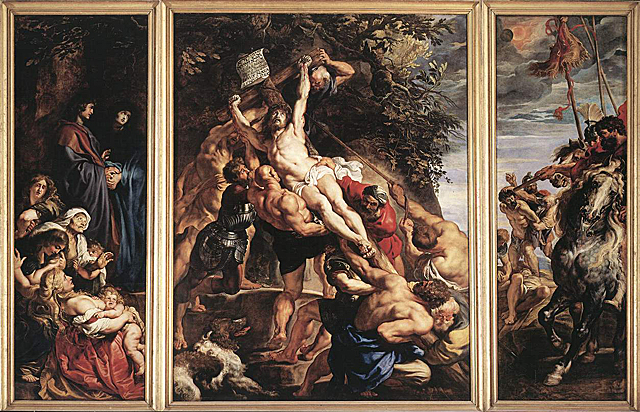

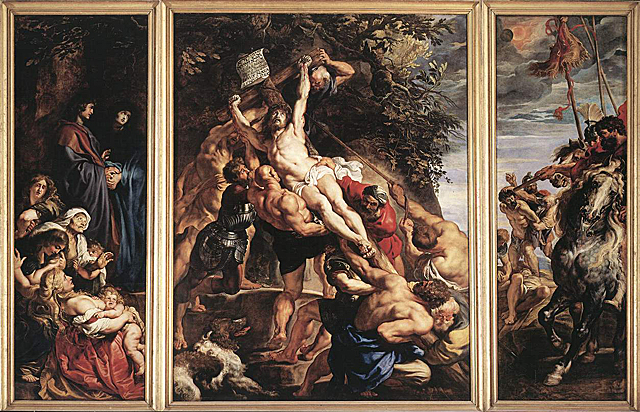

Altarpieces such as The Raising of the Cross (1610) and The Descent from the Cross (1612-1614) for the Cathedral of Our Lady were particularly important in establishing Rubens as Flanders' leading painter shortly after his return. The Raising of the Cross, for example, demonstrates the artist's synthesis of Tintoretto's Crucifixion for the Scuola di San Rocco in Venice, Michelangelo's dynamic figures, and Rubens's own personal style. This painting has been held as a prime example of Baroque religious art.

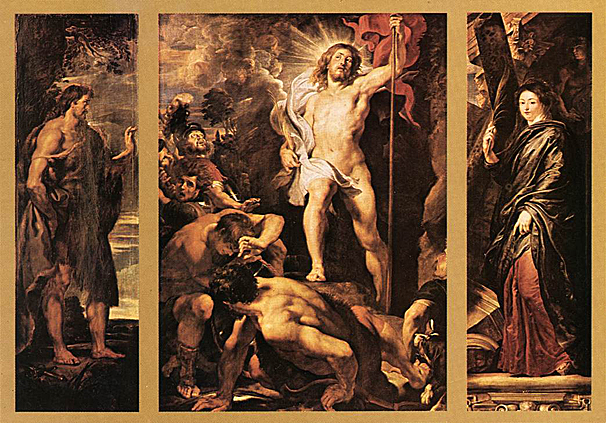

The Raising of the Cross: 1610

The triptych marked Rubens' sensational introduction of the Baroque style into Northern art. The diagonal composition is full of dynamism and animated color. The artist had just returned from Italy, with the memory of Michelangelo, Caravaggio and Venetian painting still fresh in his mind. The Raising of the Cross is the perfect summation of the unruly bravura that marked his first years in Antwerp.

In the centre nine executioners strain with all their might to raise the cross from which Christ's pale body hangs. The dramatic action is witnessed from the left by St John, the Virgin Mary and a group of weeping women and children. On the right, a Roman officer watches on horseback while soldiers in the background are crucifying the two thieves. In other words, the subject is spread across all three panels. The outside of the wings shows Saints Amand, Walpurgis, Eligius and Catherine of Alexandria.

The painting was confiscated by the French in 1794 and taken to Paris. It was returned to Antwerp in 1815, following the defeat of Napoleon, and installed in the church of Our Lady.

During restoration in the 1980s, successive layers of varnish, which had form an even grey veil over the painting, were removed. The burgeoning talent of the confident young Rubens is more clearly visible now in the intense emotion of the figures, the contrasting lighting, the glow of the laboring bodies and the gleam of the armor and costly robes.

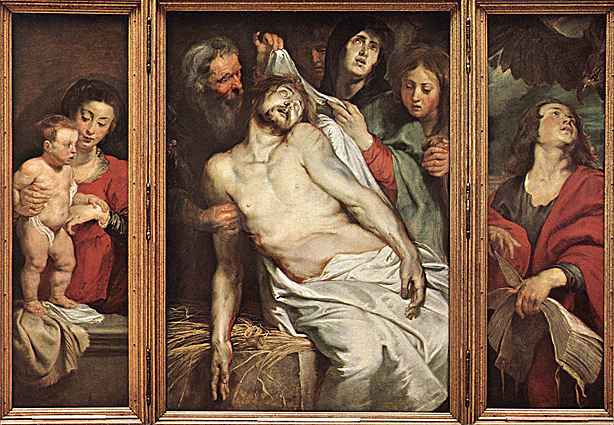

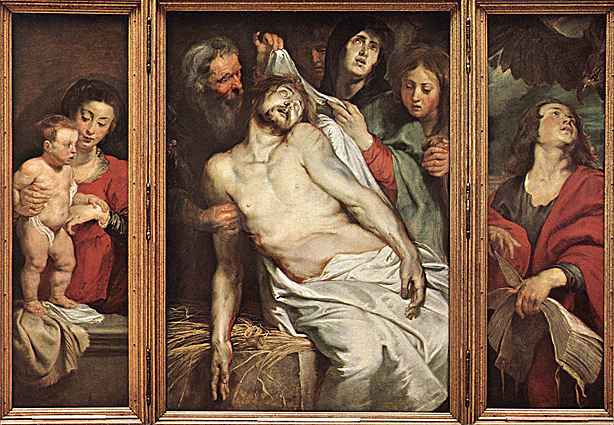

The Descent from the Cross: 1612-1614

After the termination of the Calvinist regime in Antwerp in 1585, the city's churches were gradually decorated once again with works of art. The process continued and intensified in the early part of the 17th century, when the Southern Netherlands enjoyed a period of stability and prosperity thanks to the peace policies pursued by the Archdukes Albert and Isabella. Art and artists were major beneficiaries. Antwerp was a wealthy city, whose churches were decorated with unusual splendour: Catholic worship had to be especially glorious in this place where the Protestants head recently held sway.

In 1611, the Arquebusiers - Antwerp's civic guard - commissioned a Descent from the Cross by their illustrious townsman Rubens for their altar in the cathedral. The dean of the guild at that time was Burgomaster Nicolaas Rockox, who appear in the painting. The Descent from the Cross is the second of Rubens's great altarpieces for the Antwerp Cathedral. It shows the Visitation, and the Presentation of the Temple on either side of the Descent from the Cross. (The first triptych of the Raising of the Cross was executed in 1611-12.) His rich painterly Baroque technique incorporated both elements of Venetian design and also the composition and lighting of the Roman period of Caravaggio. But the result is purely Flemish.

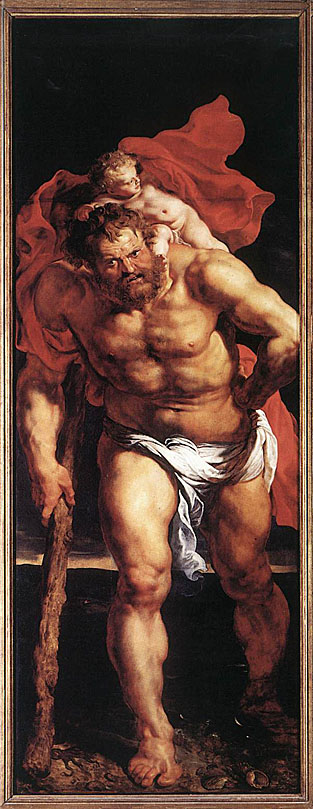

Although at first sight the themes presented in the triptych seem extremely wide-ranging, they are actually linked, for St Christopher was the Arquebusiers' patron saint. When the triptych was closed, all that worshippers could see was this scene from the legend of St Christopher, whose Greek name 'Christophorus' means 'Christ-bearer'. This fact forms the key to the entire painting, in which the friends and holy women in the centre panel, and Mary and Simeon in the wings are also 'Christ-bearers'.

The Descent from the Cross: Detail-Center Panel

The center panel of the great triptych shows the Descent from the Cross against a dark sky. Several men - Joseph of Arimathea, Nicodemus, St John and two servants - carefully lower the body of Christ in a brilliant white shroud. They are assisted by several women, including Jesus' mother. Christ's foot rests on the shoulder of Mary Magdalene, who dried his feet with her hair.

The Descent from the Cross: Detail-Left Wing

The left wing of the great triptych of the Descent from the Cross shows the Virgin Mary, pregnant with Jesus, visiting her cousin Elizabeth, who will shortly give birth to John the Baptist. The women, accompanied by their respective husbands Joseph and Zacharias, greet one another in an imposing porch. A servant carries a basket containing travel items.

The Descent from the Cross: Detail Outside Left and Right

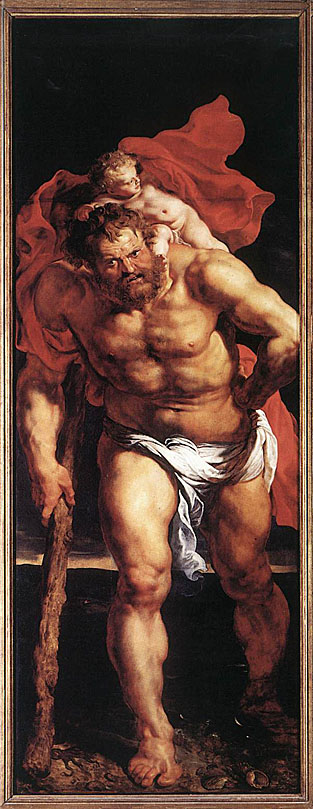

The outsides of the wings are devoted to St Christopher. According to his medieval legend, the huge St Christopher carried the Christ Child across a river on his shoulders. A hermit on the right lights his way with a lantern.

The Descent from the Cross: Detail Right Wing

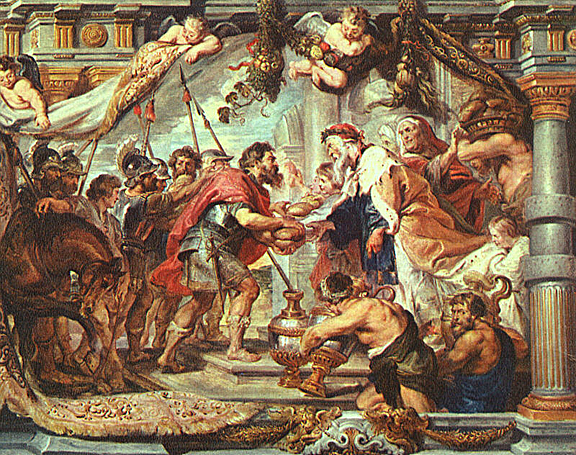

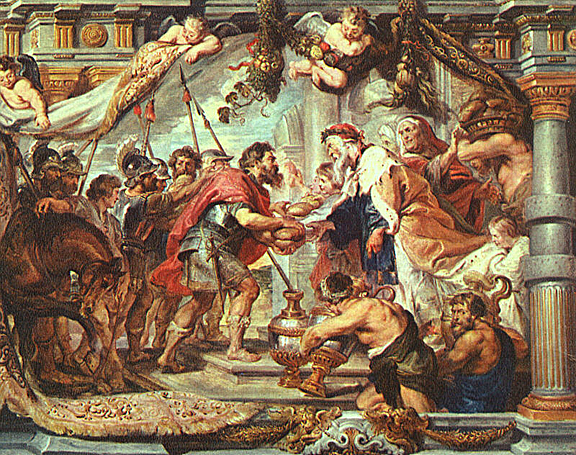

The right wing of the great triptych of the Descent from the Cross is devoted to the presentation of the Infant Christ in the Temple at Jerusalem. The elderly Simeon holds the Child in his arms while the prophetess Anna, located in the shadows between Simeon and Mary, looks on joyfully. Joseph, who has brought two sacrificial doves with him, kneels down respectfully. The onlooker on the left edge of this splendid temple interior is Nicolaas Rockox, a friend of Rubens and a prominent figure in Antwerp.

Rubens used the production of prints and book title-pages, especially for his friend Balthasar Moretus-owner of the large Plantin-Moretus publishing house- to further extend his fame throughout Europe during this part of his career. With the exception of a couple of brilliant etchings, he only produced drawings for these himself, leaving the printmaking to specialists, such as Lucas Vorsterman. He recruited a number of engravers trained by Goltzius, who he carefully schooled in the more vigorous style he wanted. He also designed the last significant woodcuts before the 19th century revival in the technique.

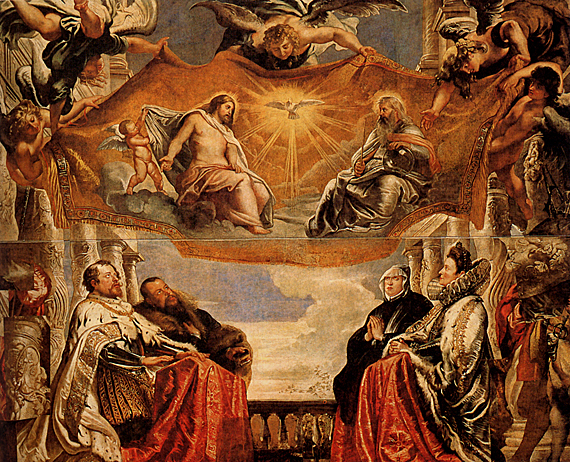

In 1621, the queen-mother of France, Marie de' Medici, commissioned Rubens to paint two large allegorical cycles celebrating her life and the life of her late husband, Henry IV, for the Luxembourg Palace in Paris. The Marie de' Medici Cycle (now in the Louvre) was installed in 1625, and although he began work on the second series it was never completed. Marie was exiled from France in 1630 by her son, Louis XIII, and died in 1642 in the same house in Cologne where Rubens had lived as a child.

The Marie de' Medici Cycle is a series of twenty-four paintings by Peter Paul Rubens commissioned by Marie de' Medici, wife of Henry IV of France, for the Luxembourg Palace in Paris. Rubens received the commission in the autumn of 1621. After negotiating the terms of the contract in early 1622, the project was to be completed within two years, coinciding with the marriage of Marie's daughter, Henrietta Maria. Twenty-one of the paintings depict Marie's own struggles and triumphs in life.

The Destiny of Marie de' Medici

The first painting of the narrative cycle, The Destiny of Marie de' Medici, is a twisting composition of the three Fates on clouds beneath the celestial figures of Juno and Jupiter.

The Fates are depicted as beautiful, nude goddesses spinning the thread of Marie de' Medici's destiny; their presence at Marie's birth assures her prosperity and success as a ruler that is unveiled in the cycle's subsequent panels. In Greek and Roman mythology, one Fate spun the thread, another measured its length, and the third cut the thread. In Rubens' depiction, however, the scissors necessary for this cutting are omitted, stressing the privileged and immortal character of the Queen's life. The last panel of the cycle, in accordance with this theme, illustrates Queen Marie rising up to her place as queen of heaven, having achieved her lifelong goal of immortality through eternal fame.

Early interpretations explained Juno's presence in the scene through her identity as the goddess of childbirth. Later interpretations suggested, however, that Rubens used Juno to represent Marie de' Medici's alter ego, or avatar, throughout the cycle. Jupiter accordingly signifies the allegory of Henri IV, the promiscuous husband.

The Birth of the Princess

The cycle's second painting, The Birth of the Princess, represents de' Medici's April 26, 1573 birth. Symbols and allegory appear throughout the painting. On the left, two putti play with a shield on which the Medici crest appears, suggesting that Heaven favored the young de' Medici from the moment of her birth. The river god in the picture's right corner is likely an allusion to the Arno River that passes through Florence, Marie's city of birth. The cornucopia above the infant's head can be interpreted as a harbinger of Marie's future glory and fortune; the lion may be seen as symbolic of power and strength. The glowing halo around the infant's head should not be seen as a reference to Christian imagery; rather, it should be read according to imperial iconography which uses the halo as an indication of the Queen's divine nature and of her future reign. Though Marie was born under the Taurus sign, Sagittarius appears in the painting; it may be seen as a guardian of imperial power.

Education of the Princess

Education of the Princess (1622-1625) shows a maturing Marie de' Medici at study. Her education is given a divine grace by the presence of three gods Apollo, Athena, and Hermes. (Apollo being associated with art, Athena with wisdom, and Hermes the messenger god for a fluency and understanding of language) Hermes dramatically rushes in on the scene and literally brings a gift from the gods, the caduceus. It is generally thought that Hermes endows the princess with the gift of eloquence, to go along with the Grace's gift of beauty. However, the caduceus, which is seen in six other paintings in the cycle, has also been associated with peace and harmony. The object may be seen as foretelling of Marie's peaceful reign. It can be interpreted that the combined efforts of these divine teachers represent Marie's idyllic preparedness for the responsibilities she will obtain in the future, and the trials and tribulations she will face as Queen. It is also suggested that the three gods, more importantly, offer their guidance as a gift that allows the soul to be "freed by reason" and gain the knowledge of what is "good" revealing the divine connection between the gods and the future Queen. The painting displays an embellished Baroque collaboration of the spiritual and earthly relationships, which are illustrated in a theatrical environment. Acting as more than just static symbols the figures portrayed take an active role in her education. Also present are the three graces, Euphrosyne, Aglaea, and Thalia giving her beauty.

The Presentation of Her Portrait to Henri IV

To fully appreciate and value this particular cycle piece and the collection as a whole, there is one historical principle to take into account. This painting was created on the cusp of the age of absolutism and, as such, one must remember royalty were considered above corporeal existence. So from birth, Marie would have led a life more ornamental than mortal. This painting of classical gods, along with allegorical personifications, aptly shows the viewer how fundamental this idea was.

Just as Tamino in The Magic Flute, Henri IV falls in love with a painted image. With Amor the Cupid as his escort, Hymen, the god of marriage, displays the princess Marie on canvas to her future king and husband. Meanwhile, Jupiter and Juno are sitting atop clouds looking down on Henri as they provide the viewer a key example of marital harmony and thus show approval for the marriage. A personification of France is shown behind Henri in her helmet, her left hand showing support, sharing in his admiration of the future sovereignty. Rubens had a way of depicting France that was very versatile in gender in many of his paintings in the cycle. Here France takes on an androgynous role being both woman and man at the same time. Frances's intimate gesture may suggest closeness between Henri and his country. This gesture would usually be shared among male companions, telling each others' secret. The way France is also dressed shows how female she is on top revealing her breasts and the way the fabric is draped adding notions of classicism. However her bottom half, most notably her exposed calves and Roman boots hints at a masculinity. A sign of male strength in the history of imagery was their stance and exposed strong legs. This connection between the two show that not only are the gods in favor of the match, the King also has the well wishes of his people.

In negotiating the marriage between Marie de' Medici and King Henri IV, a number of portraits were exchanged between the two. The king was pleased with her looks, and upon meeting her was impressed even more by her, than with her portraits. There was great approval of the match, as the pope and many powerful Florentine nobles had been advocates of the marriage and had worked at convincing the king of the benefits of such a union. The couple was married by proxy on October 5, 1600.

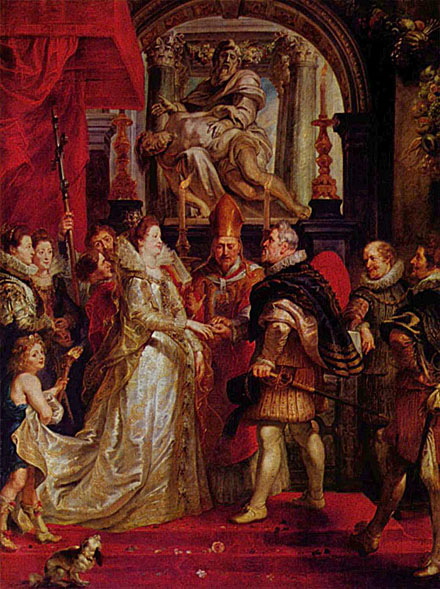

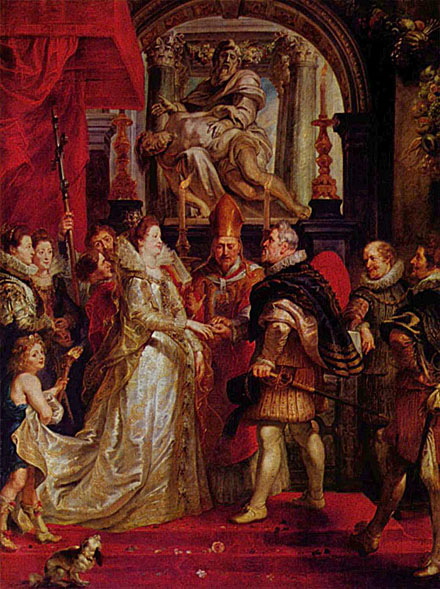

The Wedding by Proxy of Marie de' Medici to King Henri IV

The Wedding by Proxy of Marie de' Medici to King Henri IV (1622-25): Rubens depicts the marriage ceremony of the Florentine princess Marie de' Medici to the King of France, Henri IV which took place in the cathedral of Florence on October 5, 1606. Cardinal Peitro Aldobrandini presides over the ritual, however since Henri IV was too busy to attend his own wedding, the bride's uncle, the Grand Duke Ferdinand of Tuscany stood in his place and is pictured here slipping a ring on his niece's finger. All the surrounding figures are identifiable, including the artist himself. Although he was present at the actual event twenty years earlier, as a member of the Gonzaga household during his travels in Italy, Rubens appears youthful and stands behind the bride, holding a cross and gazing out at the viewer. It is highly unlikely that Rubens actually had such a pronounced presence in this scene when it took place. Those who attended the ceremony for Marie include Christine de Lorraine, Grand Duchess of Tuscany and Marie's sister Eleonora, Duchess of Mantua; and in entourage of Grand Duke are Roger de Bellegarde, Grand Esquire of France, and the Marquis de Sillery, who negotiated the marriage. As in other scenes in the Medici Cycle, Rubens includes a mythological element: the ancient god of marriage, Hymen wearing a crown of roses, carries the bride's train in one hand and the nuptial torch in the other. The scene takes place below a marble statue, which depicts God the Father mourning over the dead body of Christ, alluding to the Pieta sculpture by Baccio Bandinelli (1493-1560).

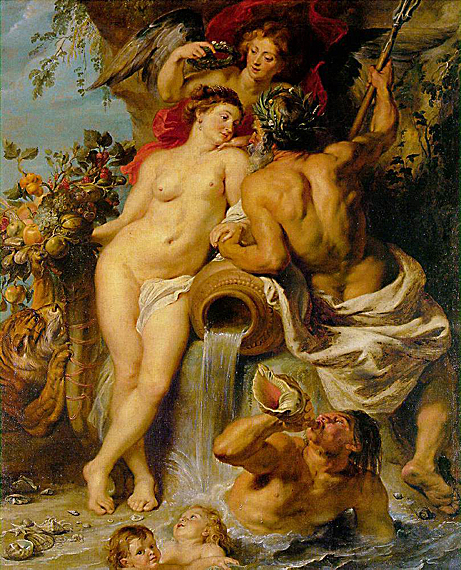

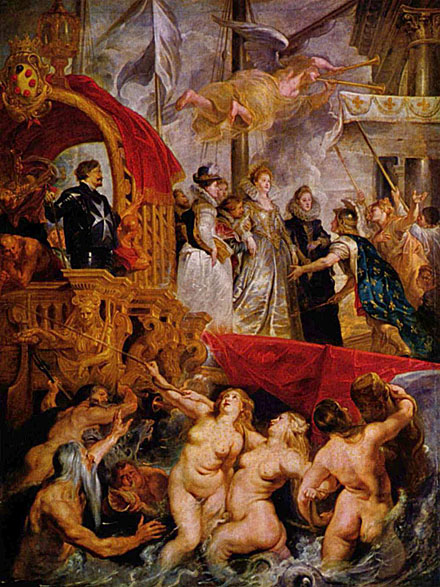

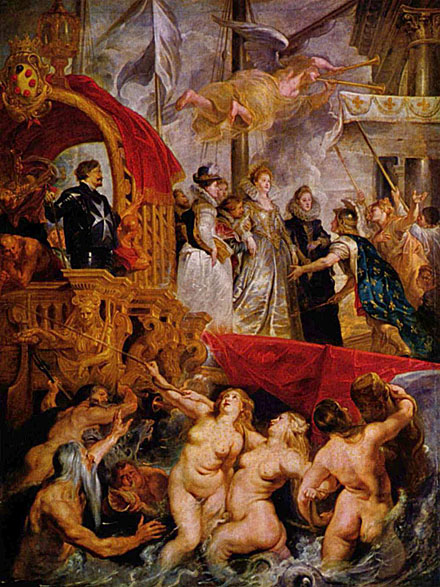

The Disembarkation at Marseilles

Having never been a particularly graceful event for anyone, disembarking a ship does not pose a problem for Rubens in his depiction of Marie de' Medici arriving in Marseilles after having been married to Henri IV by proxy in Florence. Rubens has again, turned something ordinary into something of unprecedented magnificence. He depicts her leaving the ship down a gangplank (she actually walked up, not down, but was illustrated this way by Rubens to create a diagonal element). She was accompanied by the Grand Duchess of Tuscany and her sister, the Duchess of Mantua, into the welcoming, allegorical open arms of France, evidenced by the golden fleur-de-lis on his cape of royal blue. Her sister and aunt flank Marie while two trumpets are blown simultaneously by an ethereal Fame. All this occurs while Neptune and his corps of Nereids rise from the sea, after having accompanied her on the long voyage to procure her safe arrival in Marseilles. It is melody and song as Rubens combines heaven and Earth, history and allegory into a symphony for the eyes of the viewer. Moreover, in The Debarkation at Marseilles, Marie is welcomed to her new home by a personified France, wearing a helmet and a blue mantle with golden fleur-de-lis in the painting. Above, Fame blows two horns to announce her arrival to the people of France with her future husband. Below, Neptune, three sirens, a sea-god, and a triton help escort the future Queen to her new home. To the left, the arms of the Medici can be seen above an arched structure, where a Knight of Malta stands in all of his regalia. On a side note, Avermaete discusses an interesting idea that is particularly present in this canvas.

The Meeting of Marie de' Medici and Henri IV at Lyons

This painting allegorically depicts the first meeting of Marie and Henri, which took place after their nuptials by proxy. The upper half of the painting shows Marie and Henri as the mythological Roman gods Juno and Jupiter. The representations are accompanied by their traditional attributes. Marie is shown as Juno (Greek Hera) identified by the peacocks and chariot. Henri is shown as Jupiter (Greek Zeus) identified by the fiery thunderbolts in his hand and the eagle. The joining of the couple's right hands is a traditional symbol of the marriage union. They are dressed in the classical style, which is naturally appropriate to the scene. Above the two stands Hymen who unites them. A rainbow extends from the left corner, a symbol of concord and peace. The lower half of the painting is dominated by imagery of Lyons. Reading from left to right, we see the cityscape with its single hill. The lions pull the chariot (which is a pun on the name of the city), and in the chariot we see the allegorical figure of the city herself with a crown of her battlements: Lyons. Rubens needed to be very careful in the representation of the couple's first meeting because allegedly Henri was very much involved with a mistress at the time of the marriage. In fact, due to the king's other engagements their introduction was delayed, and it was not until midnight nearly a week after Marie arrived that Henri finally joined his bride. By presenting him as Jupiter Rubens implies the promiscuity of the man and the deity. Simultaneously by placing King and Queen together he effectively illustrates the elevated status of the couple.

The Birth of the Dauphin at Fontainebleau

This painting depicts the birth of Marie de' Medici's first son, Louis XIII. Rubens designed the scene around the theme of political peace. The birth of the first male heir brings a sense of security to the royal family that they will continue to rule. In those times an heir was of the utmost importance, especially if Henri wanted to showcase his masculinity and discontinue with the pattern of the royal reproductive failure. The word dauphin is French for dolphin, a term associated with princely royalty. Henri's promiscuity made difficult the production of a legitimate heir, and rumors circulated to the extent that Henri's court artists began to employ strategies to convince the country otherwise. One of these strategies was to personify Marie as Juno or Minerva. By representing Marie as Juno, implying Henri as Jupiter, the king is seen domesticated by marriage. The queen's personification as Minerva would facilitate Henri's military prowess and her own. As a Flemish painter Rubens includes a dog in the painting, alluding to fidelity in marriage. In addition to the idea of political peace Rubens also includes the personification of Justice, Astraea. The return of Astraea to earth is symbolic of the embodiment of continuing Justice with the birth of the future king. Louis is nursed by Themis, the goddess of divine order, referring to Louis XIII birthright to one day become king. The baby is quite close to a serpent, which is a representation of Health. Rubens incorporates the traditional allegory of the cornucopia, which symbolizes abundance, to enhance the meaning of the painting by including the heads of Marie de' Medici's children who have yet to be born among the fruit. While Marie gazes adoringly at her son, Fecundity presses the cornucopia to her arm, representing the complete and bountiful family to come.

The Consignment of the Regency

Throughout the depictions of Marie de' Medici's life, Rubens had to be careful not to offend either Marie or the king, Louis XIII, when portraying controversial events. Marie commissioned paintings that truthfully followed the events of her life, and it was the job of Rubens to tactfully convey these images. More than once, the artistic license of the painter was curbed in order to portray Marie in the right light. In The Consignment of the Regency, Henri IV entrusts Marie with both the regency of France and the care of the dauphin shortly before his war campaigns and eventual death. Set within a grand Italian-style architectural setting, the theme is somewhat sobering. Prudence, the figure to the right of Marie, was stripped of her emblematic snake to lessen the chances any viewer would be reminded of Marie's rumored involvement in the King's assassination. The efficacy of the form is lost in order to ensure Marie's representation in a positive light. Other changes include the removal of the Three Fates, originally positioned behind the king calling him to his destiny, war, and death. Rubens was forced to remove these mythical figures and replace them with three generic soldiers.

Also worthy of note in this painting is the first appearance the orb as a symbol of the "all-embracing rule or power of the state". This particular image appears to carry significant weight in Rubens's iconographic program for the cycle, as it appears in six (one quarter) of the twenty-four paintings of the cycle. This orb functions both as an allusion to the Roman orbis terrarum (sphere of earth) which signifies the domain and power of the Roman emperor, and as a subtle assertion of the claim of the French monarchy upon the imperial crown. While Rubens was certainly aware of the inherent meaning of the orb and employed it to great effect, it appears that Marie and her counselors instigated its introduction into the cycle to add allegorical and political grandeur to the events surrounding Marie's regency.

The Coronation in Saint-Denis

The Coronation in Saint-Denis is one of the few paintings in the cycle that does not contain any mythological figures. This painting is the last scene on the North End of the West Wall, showing the completion of Marie's divinely assisted preparation. It would be one of two paintings most visually apparent upon entrance into the gallery through the southeast corner. Rubens composes The Coronation in Saint-Denis for distanced viewing by employing accents of red. For example, the robes of two cardinals near the right edge. These accents also create a sense of unity with the neighboring work, Apotheosis of Henri IV and the Proclamation of the Regency.

This painting is a representation of an historical event in the life of the Queen where the King and the Queen were crowned at the basilica of Saint-Denis in Paris. Considered one of the principle paintings in the series along with the Apotheosis of Henri IV and the Proclamation of the Regency both scenes also show Marie de' Medici receiving the orb of state. She is conducted to the altar by the Cardinals Gondi and de Sourdis, who stand with her along with Mesieurs de Souvrt and de Bethune. The ceremony is officiated by Cardinal Joyeuse. The royal entourage includes Dauphin, the Prince of Conti with the crown, the Duc de Ventadour with the scepter, and the Chevalier de Vendome with the hand of Justice. The Princess de Conti and the Duchess de Montpensier carry the train of the royal mantle. Above in the tribune appears Henri IV, as if to give sanction to the event. The crowd below in the basilica raise their hands in acclamation of the new Queen, and above, the classical personifications of Abundantia and Victoria shower the blessings of peace and prosperity upon the head of Marie. Also, her pet dogs are placed in the foreground of the painting. Henri, not included within the centralized group, has been removed from the main scene to the balcony in the background. Also to be noted are the two winged Victories that hover above, pouring the golden coins of Jupiter. Rubens inspiration for the blue coronation orb emblazoned with golden lilies was Guillaume Dupres' presentation medal struck in 1610 at Marie's' request portraying her as Minerva with Louis XIII as Apollo-Sol. The symbolism carried the message that she was charged with the guidance of the young, soon-to-be king.

The Death of Henri IV and the Proclamation of the Regency

Sometimes also referred to as The Apotheosis of Henri IV and The Proclamation of the Regency, this particular painting within the Medici Cycle as a whole, was placed originally by Rubens as a series of three. The other two having similar design measurements, it was consigned as the middle painting in a pseudo triptych of sorts as it adorned the halls of Marie de' Medici's Palais du Luxembourg.

The painting is separated into two separate, but related scenes: the elevation of Henri IV to the heavens (he had been assassinated on the 14th of May 1610 which resulted in the immediate declaration of Marie as regent and the assumption of Marie to the crown.

On the left, Jupiter and Saturn are shown welcoming the assassinated King of France, as he ascends as a personified Roman sovereign, victoriously to Olympus. As with all of Ruben's allegorical paintings, these two figures are chosen for a reason. Jupiter is meant to be the King's celestial counterpart, while Saturn, who represents finite time, is an indication of the end of Henri's mortal existence. This particular theme, within the painting as a whole, has found other great masters receiving inspiration and fascination from Rubens' tormented figure of Bellona, the goddess of War, who lays disarmed below. Post-Impressionist, Paul Cézanne (1939-1906) registered for permission to copy the goddess as many as ten times. It should be kept in mind that Rubens's energetic manner of placing all these allegorical themes are substantially resultant from classical coins as documented through communication with his friend and notable collector of antiquities, Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc. The right side of the panel shows the succession of the new Queen, dressed in solemn clothing suited to a widow. She is framed by a triumphal arch and surrounded by people at the court, including the personification of France who is handing her a globe. The Queen accepts an orb, a symbol of government, from the personification of France while the people kneel before her and this scene is a great example of the exaggeration of facts in the cycle. Rubens stresses the idea of the Regency that was offered to the Queen, though she actually claimed it for herself the same day her husband was murdered.

Worthy of note is a possible contemporary inspirational influence on Rubens for the right side of this painting. Although originally started but may or may not have been finished in Rome, Caravaggio's Madonna of the Rosary may well have been an artistic influence on Rubens for the Proclamation of the Regency side of this painting, as the two works are highly corresponding in their presentation. Through a causal nexus, this painting would have been available to Rubens and thereby plausible for its influence to exist within Rubens's own genius on canvas. As a comparison, there are within each, two women upon a dais classical pillars, swathes of luxuriant cloth, genuflecting personages with arms extended, and allegorical figures present. In Rubens's painting, Minerva, Prudence, Divine Providence and France; in the Caravaggio, St Dominic, St Peter the Martyr, and a pair of Dominican monks. Also present in each are objects of importance: rudder, globe, and rosaries. All these and more, combine to make a persuasive argument and show a certain artistically respectful nod from Rubens to Caravaggio as two contemporaries of the time.

The Council of the Gods

This painting commemorates Marie taking over the government as new regent, and promoting long-term plans for peace in Europe by way of marriages between royal houses.

Cupid and Juno bind two doves together over a split sphere in the painting as a symbol of peace and love. Marie hoped for her son, Louis XIII, to marry the Spanish Infanata Anne and for her daughter Elizabeth to marry the future king of Spain, Philip IV, possibly resulting in an alliance between France and Spain. To Marie de' Medici these unions were probably the most significant part of her reign, for peace in Europe was Marie's greatest goal.

The Council of the Gods is one of the least understood paintings of Marie de' Medici cycle. It represents the conduct of the Queen and the great care with which she oversees her Kingdom during her Regency. For example, how she overcomes the rebellions and the disorders of the State. It also suggests that she perpetuated the policies and ideals of the late King in his life and in death. The painting subjects are placed in a celestial setting which doesn't give way to a particular place, time or event. The scene is painted with a variety of mythological figures. This, along with its setting makes it difficult to figure out the subject matter of the work. The mythological figures include Apollo and Pallas, who combat and overcome vices such as Discord, Hate, Fury, and Envy on the ground and Neptune, Pluto, Saturn, Hermes, Pan, Flora, Hebe, Pomono, Venus, Mars, Zeus, Hera, Cupid, and Diana above.

Though originally intended to be displayed on the East Wall of the gallery in Marie's Luxembourg Palace in Paris, "The Council of the Gods" is now housed at the Louvre. The mythological figures and celestial setting act as allegories for Marie's peaceful rule over France.

The Regent Militant: The Victory at Jülich

The Victory at Jülich shows the only military event that the Queen participated in during her regency: the return of Jülich (or Juliers in French) to the Protestant princes. Being a crossing of Ruhr, Juliers was of great strategic importance for France and thus the French victory was chosen to be the glorious subject of Rubens' painting. The scene is rich with symbolism highlighting her heroism and victory. The Queen thrusts her arm high with an assembler's baton in hand. In the upper part of the image Victoria appears crowning her with laurel leaves which is a symbol of victory. Also symbolizing victory is the imperial eagle which can be seen in the distance. The eagle in the sky compels the weaker birds to flee. The Queen is accompanied by a womanly embodiment of what was once thought to be, Fortitude because of the lion beside her. However, the figure is Magnanimity, also referred to as Generosity, because of the riches held in her palm. One of the pieces in her hand is the Queen's treasured strand of pearls. Other figures include Fame and the personification of Austria with her lion. Fame in the right side of the painting pushes air through the trumpet so powerfully that a burst of smoke comes out. In the painting Marie de' Medici is highly decorated and triumphant after the collapse of a city, she is depicted across a white stallion to demonstrate that, like the departed King Henri IV, she could triumph over rivals in warfare.

The Exchange of the Princesses at the Spanish Border

The Exchange of Princesses celebrates the double marriage of the Habsburg Infanta Anna of Spain to Louis XIII of France and Louis XIII's sister, Isabella Bourbon, to future king of Spain, Phillip IV on 9 November 1615. France and Spain present the young princesses, aided by a youth who is probably Hymen. Above them, two putti brandish hymeneal torches, a small zephyr blows a warm breeze of spring and scatter roses, and a circle of joyous butterfly-winged putti surround Felicitas Publica with the caduceus, who showers the couple with gold from her cornucopia. Below, the river Andaye is filled with sea deities come to pay homage to the brides: the river-god Andaye rests on his urn, a nereid crowned with pearls offers a strand of pearls and coral as wedding gifts, while a triton blows the conch to herald the event. The wedding, which was thought to secure peace between France and Spain, took place on a float midway across the Bidassoa River, along the French-Spanish border. In Ruben's depiction, the princesses stand with their right hands joined between personifications of France and Spain. Spain with a recognizable symbol of a lion on her helmet is on the left, whereas France, with fleur-de-lis decorating her drapery, is on the right. Anna, at age fourteen the older of the two, turns back as if to take leave of Spain, while France gently pulls her by the left arm. In turn, Spain can be seen taking the thirteen year old Isabella by her left arm.

The Felicity of the Regency of Marie de' Medici

This particular painting in the Marie de' Medici Cycle is noteworthy for its uniqueness in execution. While the other paintings were completed at Rubens's studio in Antwerp, The Felicity of the Regency of Marie de' Medici was designed and painted entirely by Rubens on the spot to replace another, far more controversial depiction of Marie's 1617 expulsion from Paris by her son Louis. Completed in 1625, this is the final painting in the cycle in terms of chronological order of completion.

Here Marie is shown in allegorical fashion as the personification of Justice itself and flanked by a retinue of some of the primary personifications/gods in the Greek and Roman pantheon. These have been identified as Cupid, Minerva, Prudence, Abundance, Saturn, and two figures of Fame, all indicated by their traditional attributes, all bestowing their bounties on the Queen. (Cupid has his arrow; Prudence carries a snake entwined around her arm to indicate serpent-like wisdom; Abundance also appears with her cornucopia, also a reference to the fruits of Marie's regency. Minerva, goddess of wisdom, bears her helmet and shield and stands near Marie's shoulder, signifying her wise rule. Saturn has his sickle and is personified as Time here guiding France forward. Fame carries a trumpet to herald the occasion. These personifications are accompanied in turn by several allegorical figures in the guise of four putti and three vanquished evil creatures (Envy, Ignorance, and Vice) as well as a number of other symbols that Rubens employed throughout the entire cycle of paintings.

Though this particular painting is one of the most straightforward in the series, there is still some minor dispute about its significance. Rather than accept this as a depiction of Marie as Justice, some hold that the real subject of the painting is the "return to earth of Astraea, the principle of divine justice, in a golden age." They support this claim with a statement in Rubens's notes which indicates that "this theme holds no special reference to the particular reason of state of the French kingdom." Certain symbolic elements, such as the wreath of oak leaves (a possible corona civica), France being seen as a subjugated province, and the inclusion of Saturn in the scheme might all point to this interpretation and certainly would not have been lost on Rubens. Fortunately, and perhaps solely due to the controversy surrounding this painting, Rubens mentioned its significance in a letter to Peiresc dated 13 May 1625. It reads,

I believe I wrote you that a picture was removed which depicted the Queen's departure from Paris and that, in its place, I did an entirely new one which shows the flowing of the Kingdom of France, with the revival of the sciences and the arts through the liberality and the splendor of Her Majesty, who sits upon a shining throne and holds a scale in her hands, keeping the world in equilibrium by her prudence and equity.

Considering the haste with which Rubens completed this painting, his lack of specific reference to a golden age in his letter, and the existence of several contemporary depictions of Marie as a figure of Justice, most historians are content with the simpler allegorical interpretation which is more consistent both with Rubens's style and the remainder of the cycle.

It is believed that the original painting mentioned in the letter depicting Marie's departure from Paris was rejected in favor of The Felicity of the Regency due to the more innocuous subject matter of the latter. Rubens, in the same letter, goes on to say,

"This subject, which does not touch on the particular political considerations ... of this reign, nor have reference to any individual, has been very well received, and I believe that had it been entrusted altogether to me the business of the other subjects would have turned out better, without any of the scandal or murmurings."

Here, we can see evidence of the adaptability of Rubens' style which made his career so successful. His willingness to fit his ideas with those of the patron equipped him with the perfect tools to be in charge of such a delicate and heavily anticipated subject.

Louis XIII Comes of Age

The painting Louis XIII Comes of Age represents the historical scene of the transferring of power from mother to son in abstract, or allegorical means. Marie has reigned as regent during her son's youth, and now she has handed the rudder of the ship to Louis, the new king of France. The ship represents the state, now in operation as Louis steers the vessel. Each of the rowers can be identified by the emblematic shields that hang on the side of the ship. The second rower's shield depicts a flaming altar with four sphinxes, a coiling serpent and an open eye that looks downwards. These characteristics are known to be that of Piety or Religion, both of which Maria would want her son to embody. What is also known as a parade boat, Rubens referencing Horace's boat, is adorned with a dragon on front and dolphins on the stern. Louis looks upwards to his mother for guidance on how to steer the ship of state. In the violent clouds are two Fames, one with a Roman buccina and the second with what seems to be a trumpet. Louis guides, while the ship's actual movement is due to the four rowing figures, personifying Force, Religion, Justice, and Concord. The figure adjusting the sail is thought to be Prudence or Temperance. At the center in front of the mast stands France, with a flame in her right hand illustrating steadfastness and the globe of the realm, or the orb of government, in her left. Force, extending her oar and heaving to, is identified by the shield just beneath her showing a lion and column. She is paired with Marie by the color of their hair, and similarly Louis is paired with Religion, or the Order of the Holy Spirit. The pairing of Marie with the figure of Force gives power to the image of the queen, while Marie's actual pose is more passive, showing very effectively her graceful acknowledgement of her son's authority henceforth. It is an interesting painting to examine within the context of the tense relationship between the young king and his mother. Sometime just prior to his coronation, Louis XIII and Marie de' Medici had a quarrel, leading to the exile of the queen. Rubens obviously would have known this and so chose to ignore the tension surrounding Marie's relationship with her son, instead emphasizing her poise in the transfer of power.

The Flight from Blois

The Flight from Blois is a depiction of Queen Marie escaping from confinement at Blois. The Queen stands in a dignified manner, suggesting her poise in times of disarray, amongst a chaotic crowd of handmaidens and soldiers. She is led and protected by a representation of France, and guided by illustrations of Night and Aurora. They are used literally to portray the actual time of the event and shield the queen from spectators as they illuminate her path. Rubens painted a scene of the event in a more heroic nature rather than showing the accuracy of realistic elements. According to historical records of the Queen's escape, this painting is not truthfully reflecting the moment of the occurrence. Rubens did not include many of the negative aspects of the event, fearing that he would offend the Queen, which resulted in the paintings non-realistic nature. The Queen Marie is depicted in a humble way, yet the illustration implies her power over the military. She does not express any hardships she had gone through by the escape. The male figures in foreground reaching for are unknown. The larger figures in the background represent the military, who were added to have a symbolic meaning of the Queen's belief in the command over military.

The Negotiations at Angouleme

In The Negotiations at Angouleme, Marie de' Medici genially takes the olive branch from Mercury, the messenger god, in the presence of both of her priests, as she gives her consent to have discussions with her son concerning her clash to his governmental direction. Rubens uses several methods to portray Queen Marie in precisely the light that she wanted to be seen, as her young son's guardian and wise advisor. Enthroned on a pedestal with sculptures of Minerva's symbols of wisdom and two putti holding a laurel wreath to represent victory and martyrdom, the representation of Marie de' Medici is quite clear. Her humble, yet all-knowing gaze conveys the wisdom that she holds. She is also placed compositionally in a tight and unified group with the cardinals, signifying a truthful side opposed to Mercury's dishonesty. Rubens gave Mercury an impression of untruthfulness by illustrating his figure hiding a caduceus behind his thigh. The effect of the two groups of figures is meant to stress the gap between the two sides. Rubens also added a barking dog, a common reference used to indicate or warn someone of foreigners who came with evil intention. All of these symbols, Rubens displayed in this ambiguous and enigmatic painting to represent or "misrepresent" Marie de' Medici in the manner that portrayed her as the prudent, yet caring and humble mother of a young and naive monarch. Overall, this painting is the most problematic or controversial, as well as the least understood out of the entire cycle. This image is of; once again, Marie claiming her of regal authority yet was nonetheless the first step towards peace between mother and son.

The Queen Opts for Security

Rubens's The Queen Opts for Security represents Marie de' Medici's need for security through a depiction of the event when Marie de' Medici was forced to sign a truce in Angers after her forces had been defeated at Ponte-de-Ce. Though the painting shows Marie de' Medici's desire for security with the representation of the Temple of Security, the symbols of evil at bay, and the change of smoky haze to clarity, there is also underlying symbolism of unrest to the acceptance of the truce. The round shape of the temple, like those built by the ancients to represent the world, and has an Ionic order that is associated with Juno and Maria herself. The temple defines itself, by also including a plaque above the niche that says "Securitati Augustae" or For the Secturity of the empress. She is shown with the snakes of the caduceus emblem having uneasy movement and the forced escorting of the queen by Mercury into the Temple of Peace give the feeling of a strong will not to be defeated. It can also be debated that the painting is not really about peace or security, but really a unrelenting spirit that does not give into loss. As she is a divine power, she is heroically depicted in a classical setting using neoplatonic hierarchy and visual cues of light on her face. These ultimately imply that this allegory of Marie de' Medici is an apotheosis. Additionally, the inclusion of two differently adorned personifications of Peace hints at the fact that Rubens wanted confuse or excite the viewer to look deeper into the this particular painting as a whole.

Reconciliation of the Queen and her Son

The Return of the Mother to Her Son tenuously held an alternate title The Full Reconciliation with the Son after the Death of the High Constable until the temperament of the nation was assessed. The many headed hydra struck a fatal blow by Divine Justice as witnessed by Divine Providence, a theme based on a classical seventeenth century metaphor for insurrection. Here the monster is a stand in for the dead Constable de Luynes who has met its demise at the hand of a feminine Saint Michael. The death in 1621 of the falconer turned supreme commander may have improved the tensions between mother and son, but Conde, considered the most dangerous of Marie de' Medici's foes quickly stepped in to fill the gap. Rubens' deliberate vagueness would be consistent with his practice of generalizing and allegorizing historical facts especially in a painting about peace and reconciliation. Marie, desiring vindication for the death of her close personal friend, Concini, would likely have intended a more direct personal allusion to Constable de Luynes, but Rubens preferring to keep to allegory, avoided specifics that could later prove embarrassing. The artist chose the high road, relying on Ripa's visual vernacular, to portray a scene where virtues defeat vices and embrace peaceful reconciliation making little more than an allusion to a vague political statement.

It is not hard to imagine the much maligned scapegoat Luyens as the one suffering divine punishment and being thrown into the pits of hell while assuming all the blame for the animosity between Louis XIII and his mother. In this painting, Louis XIII, represented as an adult, is depicted as Apollo. The hydra's death is not at the hand of Apollo as might be expected. Instead it is left to an Amazon-like vision of Providence/Fate. With the removal of the scales she carried in an earlier sketch that would have connected her to Louis XII, we are left with an entity who with no help from Louis, slays the adversary as he appears oblivious and unconcerned. Marie de' Medici however, emerges as a loving mother, ready to forgive all evils and pain endured.

The Triumph of Truth

The last painting in the cycle, The Triumph of Truth, is a purely allegorical depiction of King Louis XIII and his mother, the Queen, reconciling before heaven. The Queen and Louis XIII are depicted floating in heaven, connected by the symbol of Concordia, which demonstrates her sons' forgiveness and the peace that was reached between them. Below, Saturn raises Veritas to heaven which symbolizes truth being, "brought to the light," as well as the reconciliation between the Queen and her son. The illustrations of Time and Truth occupy almost 3/4 of the lower canvas. The upper part of the canvas is filled with renderings of Marie and her son. In the composition, Marie is depicted as much larger than her son and occupies much more space. Her larger, less obscured body is turned frontally on the picture plane, which emphasizes her importance. Her importance is further highlighted by her equal height to her son, the King. Her son who is obscured in part by the Wing of Time, kneels before the queen and presents her with the token of amity, the clasped hands and flaming heart within a laurel crown. Compositionally, Rubens gives the queen greater importance in this panel through the use of gestures and gazes. In the work, Truth gestures toward the Queen while Time looks toward her from below. Both figures ignore the King. Rubens artfully projected both mother and son into the future, depicting them as more aged and mature than in the preceding panel (Peace is Confirmed in Heaven). It is at this point that the Medici Cycle changes to the subject of the Queen Mother's reign.[98] With the death of son Louis' court favorite, Charles d'Albert de Luynes, mother and son reconcile. Marie receives ultimate vindication by being re-admitted to the Council of State in January of 1622. This picture represents how time thus uncovers the truth in correspondence to the relationship between Marie and her son.

The final painting coincided with Marie's interest in politics after the death of her husband. She believed that diplomacy should be obtained through marriage and it is the marriage of her daughter Henrietta Maria to Charles I that rushed the completion of the Medici Cycle.

After the end of the Twelve Years' Truce in 1621, the Spanish Habsburg rulers entrusted Rubens with a number of diplomatic missions. Between 1627 and 1630, Rubens's diplomatic career was particularly active, and he moved between the courts of Spain and England in an attempt to bring peace between the Spanish Netherlands and the United Provinces. He also made several trips to the Northern Netherlands as both an artist and a diplomat. At the courts he sometimes encountered the attitude that courtiers should not use their hands in any art or trade, but he was also received as a gentleman by many. It was during this period that Rubens was twice knighted, first by Philip IV of Spain in 1624, and then by Charles I of England in 1630. He was awarded an honorary Master of Arts degree from Cambridge University in 1629.

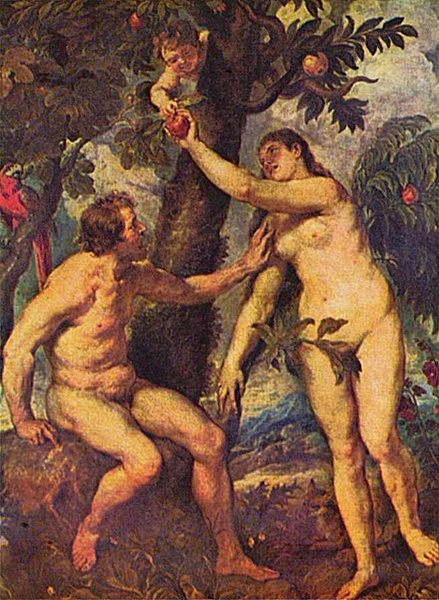

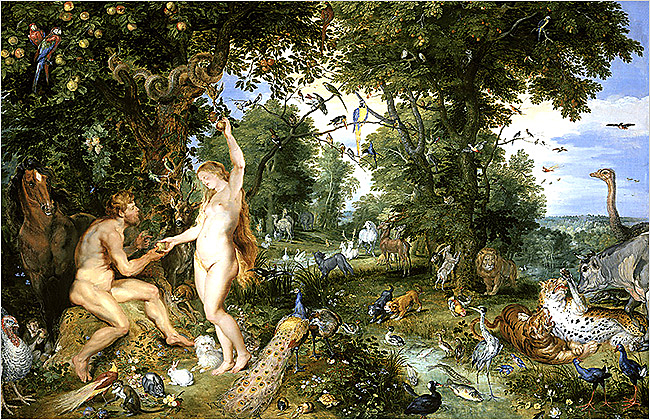

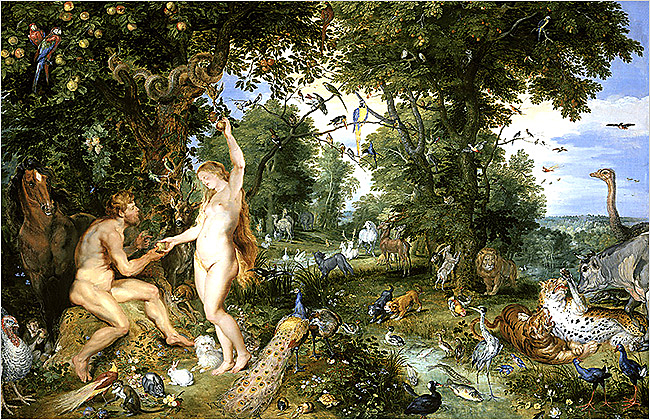

Rubens was in Madrid for eight months in 1628-1629. In addition to diplomatic negotiations, he executed several important works for Philip IV and private patrons. He also began a renewed study of Titian's paintings, copying numerous works including the Madrid Fall of Man (1628-29). During this stay, he befriended the court painter Diego Velázquez. The two planned to travel to Italy together the following year. Rubens, however, returned to Antwerp and Velázquez made the journey without him.

Madrid 'Fall of Man'

His stay in Antwerp was brief, and he soon traveled on to London. Rubens stayed there until April, 1630. An important work from this period is the Allegory of Peace and War (1629; National Gallery, London). It illustrates the artist's strong concern for peace, and was given to Charles I as a gift.

Minerva Protects Pax from Mars

The painting was probably executed in England in 1629-30, illustrating Rubens's hopes for the peace he was trying to negotiate between England and Spain in his role as envoy to Philip IV of Spain. Rubens presented the finished work to Charles I of England as a gift.

The central figure represents Pax (Peace) in the person of Ceres, goddess of the earth, sharing her bounty with the group of figures in the foreground. The children have been identified as portraits of the children of Rubens's host, Sir Balthasar Gerbier, a painter-diplomat in the service of Charles I.

To the right of Pax is Minerva, goddess of wisdom. She drives away Mars, the god of war, and Alecto, the fury of war. A winged cupid and the goddess of marriage, Hymen, lead the children (the fruit of marriage) to a cornucopia, or horn of plenty. The satyr and leopard are part of the entourage of Bacchus, another fertility god, and leopards also draw Bacchus's chariot. Two nymphs or maenads approach from the left, one brings riches, the other dances to a tambourine. A putto holds an olive wreath, symbol of peace, and the caduceus of Mercury, messenger of the gods.

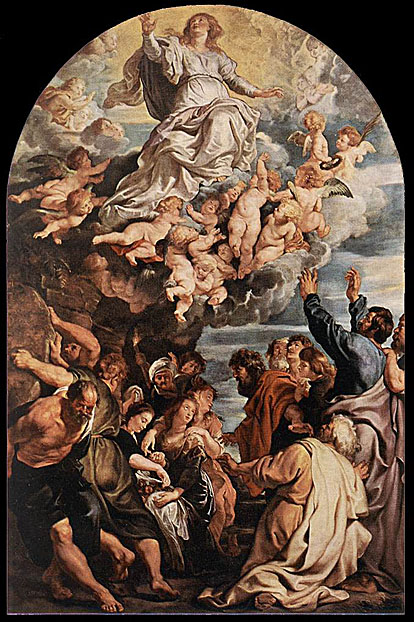

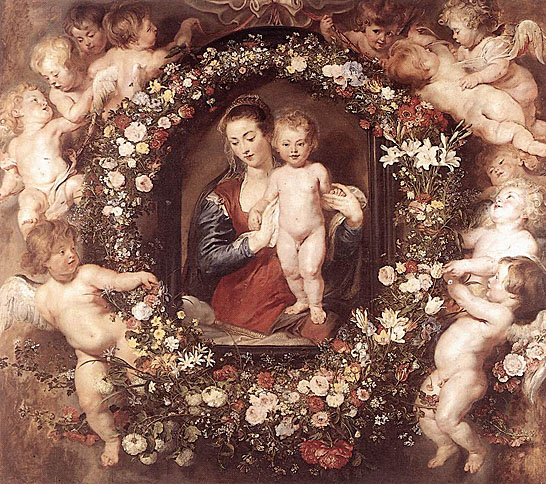

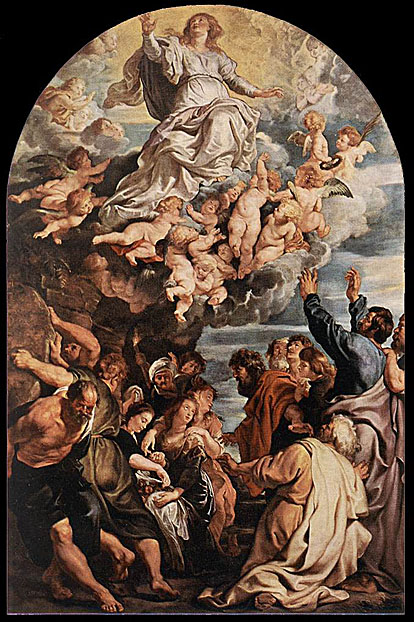

While Rubens's international reputation with collectors and nobility abroad continued to grow during this decade, he and his workshop also continued to paint monumental paintings for local patrons in Antwerp. The Assumption of the Virgin Mary (1625-6) for the Cathedral of Antwerp is one prominent example.

The Assumption of the Virgin Mary: 1626

The Assumption of the Virgin Mary or Assumption of the Holy Virgin is a painting by Peter Paul Rubens, completed in 1626 as an altarpiece for the high altar of the Cathedral of Our Lady, Antwerp, where it remains.

According to New Testament apocrypha, Jesus' mother Mary was physically assumed (raised) to heaven after her death. In Rubens depiction of the Assumption, a choir of angels lifts her in a spiraling motion toward a burst of divine light. Around her tomb are gathered the 12 apostles - some with their arms raised in awe; others reaching to touch her discarded shroud. The women in the painting are thought to be Mary Magdalene and the Virgin Mary's two sisters. A kneeling woman holds a flower, referring to blossoms that miraculously filled the empty coffin.

The Antwerp cathedral opened a competition for an Assumption altar in 1611. Rubens submitted models to the clergy on 16 February 1618. In September 1626, 15 years later, he completed the piece.

Rubens's last decade was spent in and around Antwerp. Major works for foreign patrons still occupied him, such as the ceiling paintings for the Banqueting House at Inigo Jones's Palace of Whitehall, but he also explored more personal artistic directions.

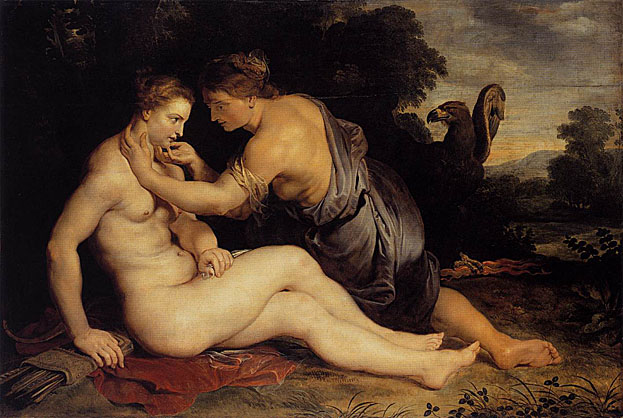

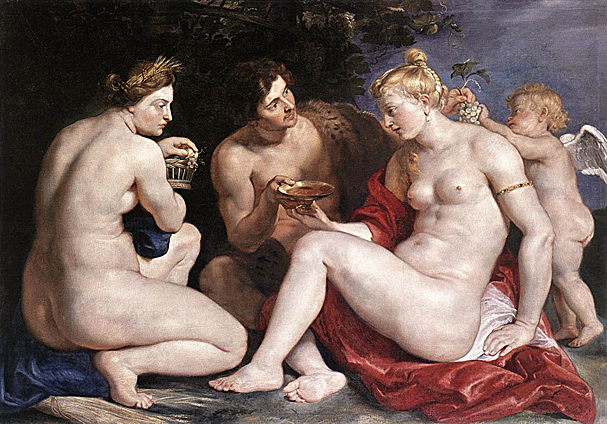

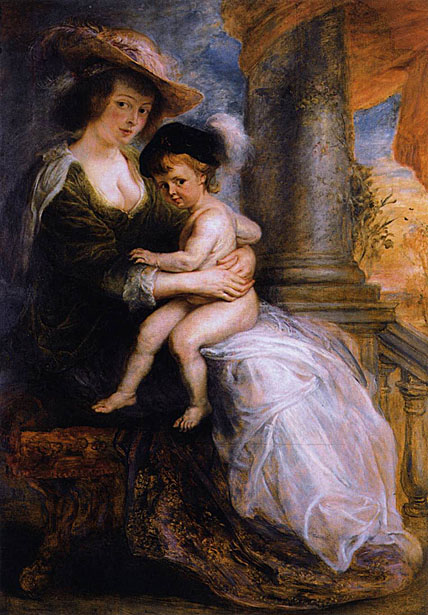

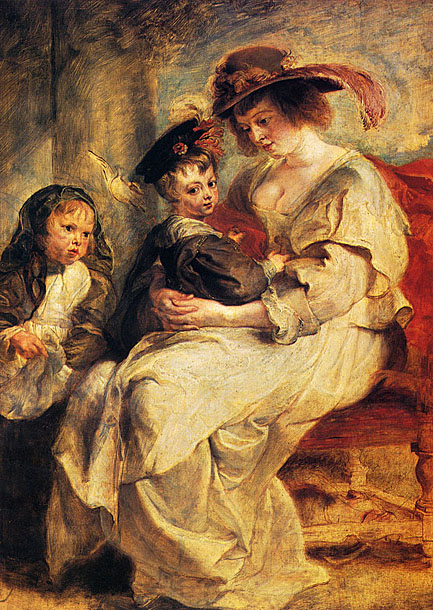

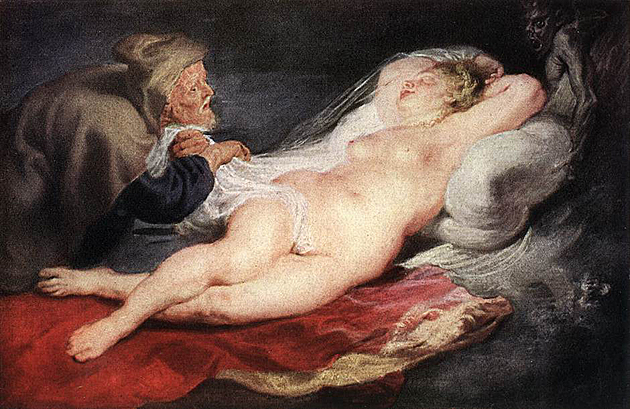

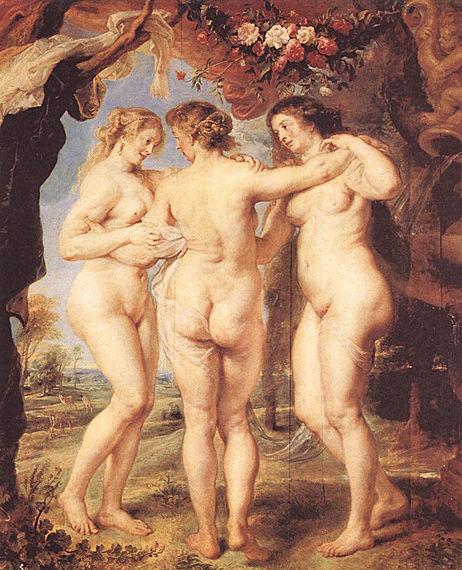

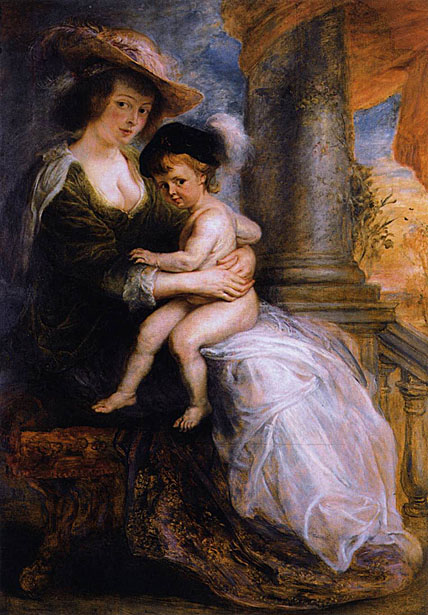

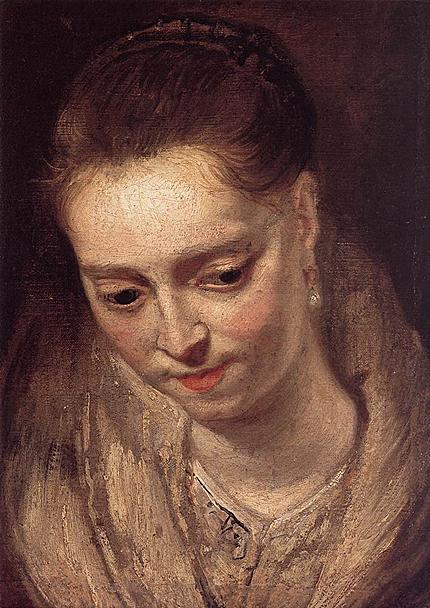

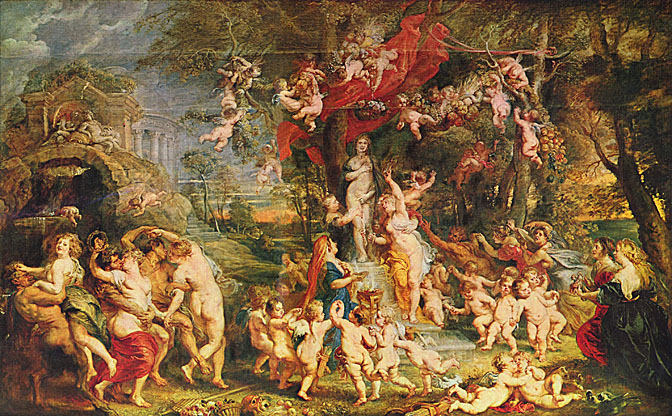

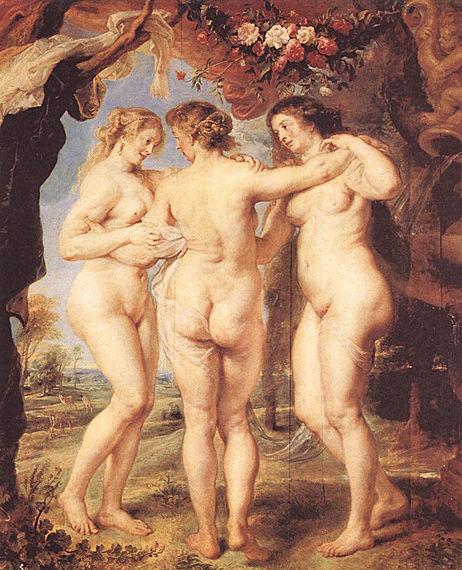

In 1630, four years after the death of his first wife, the 53-year-old painter married 16-year-old Helene Fourment. Helene inspired the voluptuous figures in many of his paintings from the 1630s, including The Feast of Venus (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna), The Three Graces (Prado, Madrid) and The Judgment of Paris (Prado, Madrid). In the latter painting, which was made for the Spanish court, the artist's young wife was recognized by viewers in the figure of Venus. In an intimate portrait of her, Helene Fourment in a Fur Wrap, also known as Het Pelsken, Rubens's wife is even partially modeled after classical sculptures of the Venus Pudica, such as the Medici Venus.

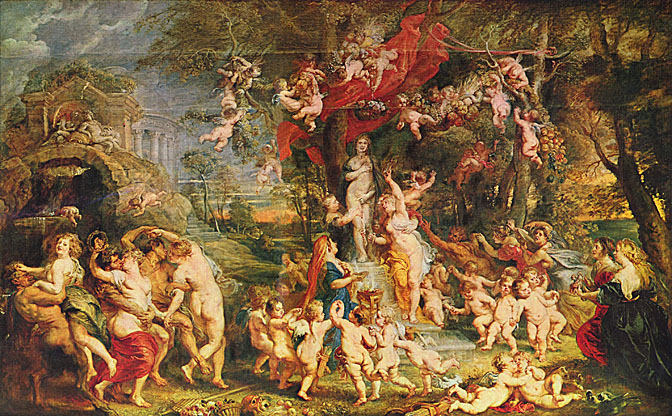

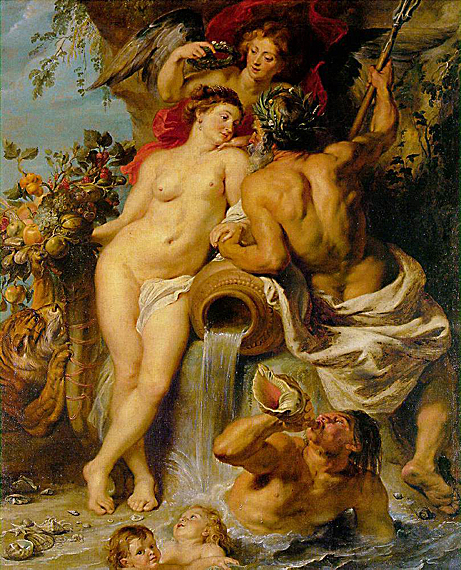

The Feast of Venus

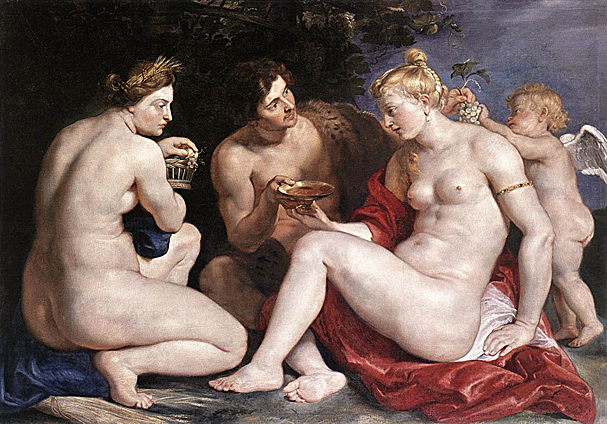

The Three Graces

Charities (called in Latin Graces) ancient Greek divines for beauty, grace and artistic inspiration, and perhaps also, in their earliest form, of powers of vegetation. They are generally said to be tree sisters called Euphrosyne, Thalia and Aglaea. Their father was Zeus, mother either Eurynome, or Hera. They are usually depicted as naked girls embracing at each other. They frequently accompany Apollo, Athena, Aphrodite, Eros and Dionysus.

The Judgment of Paris

Rubens follows the story of the Judgement of Paris as told by Lucian in the 'Judgement of the Goddesses'.

Alterations to this work show that Rubens first painted an earlier moment in the story when Mercury ordered the goddesses to undress; the final stage shows Paris awarding the golden apple to Venus, who stands between Minerva and Juno; Mercury stands behind Paris; above is the Fury, Alecto.

Venus with a Fur Wrap

In this painting the artist portrayed his second wife, Helena Fourment nude but for a fur. This was certainly his favourite among the many paintings exhibiting her undeniable charms. At all events, he refused to part with Het Pelsken. In tones worthy of Titian, he painted Helena with curly hair, her nipples erect, her nudity barely concealed by a fur wrap better suited to her husband's bulk than her own. Her expression is difficult to read: is her mutinous air intended as a provocation, or was she simply anxious to wrap herself up against the cold?

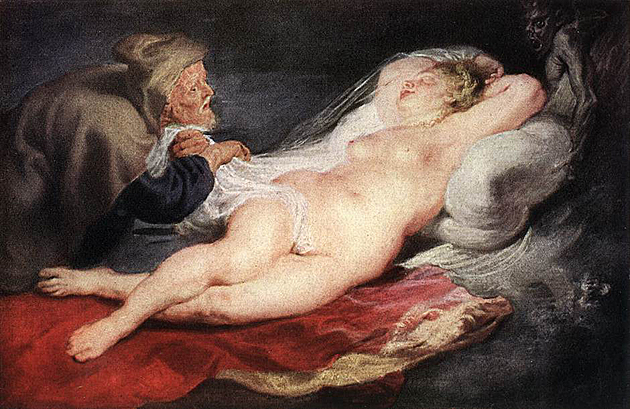

Venus at a Mirror

The toilet of Venus is a timeless theme of sensuous seduction.

In 1635, Rubens bought an estate outside of Antwerp, the Chateau de Steen (Het Steen), where he spent much of his time. Landscapes, such as his Chateau de Steen with Hunter (National Gallery, London) and Farmers Returning from the Fields (Pitti Gallery, Florence), reflect the more personal nature of many of his later works. He also drew upon the Netherlandish traditions of Pieter Bruegel the Elder for inspiration in later works like Flemish Kermis (c. 1630; Louvre, Paris).

View of Het Steen

Farm at Laken

Rubens died from gout on May 30, 1640. He was interred in Saint Jacob's church, Antwerp. Between his two marriages the artist bore eight children, three with Isabella and five with Helene; his youngest child was born eight months after his death.

Rubens was a prolific artist. His commissioned works were mostly religious subjects, "history" paintings, which included mythological subjects, and hunt scenes. He painted portraits, especially of friends, and self-portraits, and in later life painted several landscapes. Rubens designed tapestries and prints, as well as his own house. He also oversaw the ephemeral decorations of the Joyous Entry into Antwerp by the Cardinal-Infante Ferdinand in 1635.

The Cardinal Infante Ferdinand

His drawings are mostly extremely forceful but not detailed; he also made great use of oil sketches as preparatory studies. He was one of the last major artists to make consistent use of wooden panels as a support medium, even for very large works, but he used canvas as well, especially when the work needed to be sent a long distance. For altarpieces he sometimes painted on slate to reduce reflection problems.

Paintings can be divided into three categories: those painted by Rubens himself, those which he painted in part (mainly hands and faces), and those he only supervised. He had, as was usual at the time, a large workshop with many apprentices and students, some of whom, such as Anthony Van Dyck, became famous in their own right. He also often sub-contracted elements such as animals or still-life in large compositions to specialists such as Frans Snyders, or other artists such as Jacob Jordaens.

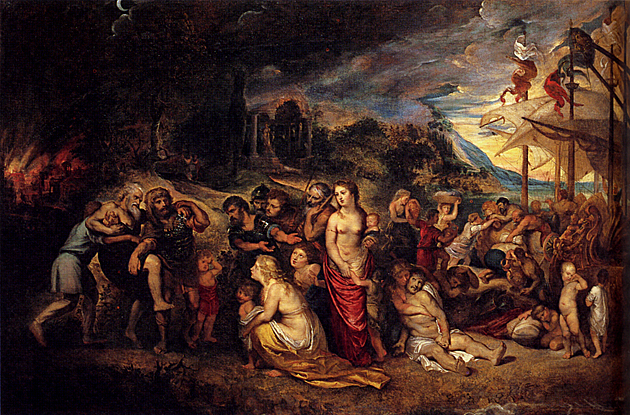

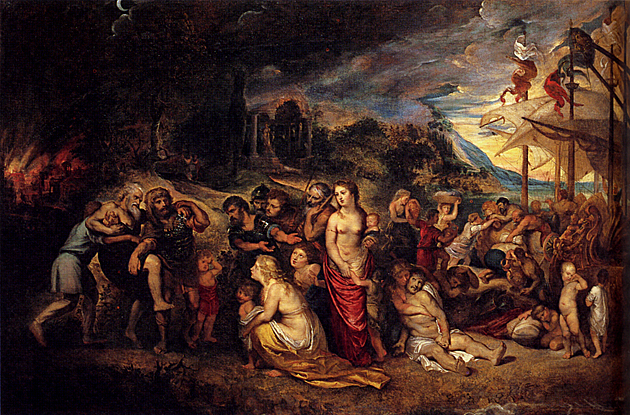

At a Sotheby's auction on July 10, 2002, Rubens' newly discovered painting Massacre of the Innocents sold for 49.5million punds ($76.2 million) to Lord Thomson. It is a current record for an Old Master painting.

Massacre of the Innocents: 1621

Recently in 2006, however, another lost masterpiece by Rubens, The Calydonian Boar Hunt, dating to 1611 or 1612, was sold to the Getty Collection in Paris for an unknown amount. It had been mistakenly attributed to a follower of Rubens for centuries until art experts authenticated it.

The Calydonian Boar Hunt

Press Release

The Calydonian Boar Hunt Ranks as One of the Greatest Paintings by Rubens in the United States

May 8, 2006

LOS ANGELES-The J. Paul Getty Museum has acquired The Calydonian Boar Hunt (about 1611-12), a newly discovered painting by 17th-century master Peter Paul Rubens (Flemish, 1577-1640) that was previously only known from later copies and engravings. It is one of the most significant works by Rubens to become available in a generation and ranks among his greatest paintings held in the United States. With this new acquisition, the Getty Museum will have the nation's most important collection of works by the artist from the innovative and crucial period following his return to Antwerp, which formed the foundation for the rest of his career. The painting will be on view to the public for the first time at the Getty Center from July 5, 2006.

"We are extremely excited about this rare find. It is seldom that a "lost" painting of such an innovative historical subject by an artist of this caliber comes to light again," says Michael Brand, director of the J. Paul Getty Museum. "What has been unknown to scholars until now is the extraordinary beauty and visual power of this painting, which epitomizes Rubens' assurance and technical brilliance at a key moment of his career. This acquisition offers us the opportunity to study and appreciate the work for the first time, establishing another connection to this influential talent. From this one painting, we can trace the root of Rubens' expressive style and his bold inventiveness, and observe his passion and personal affinity for classical art and literature."

The Calydonian Boar Hunt will be installed in the permanent collection galleries of the Getty Museum at the Getty Center. Here, among the Museum's outstanding 17th-century paintings collection, The Calydonian Boar Hunt will be displayed alongside works by Nicolas Poussin, Orazio Gentileschi, Jan Brueghel the Elder, and other contemporaries of Rubens. Visitors will be able to learn more about Rubens in two complementary exhibitions opening this summer-Rubens and Brueghel: A Working Friendship, and Rubens and His Printmakers. Both these Getty Museum exhibitions run concurrently at the Getty Center from July 5-September 24, 2006.

With The Calydonian Boar Hunt joining The Return from War: Mars Disarmed by Venus (1610-12) and The Entombment (about 1612), all painted at around the same time, the Museum will be able to vividly demonstrate the ingenuity of one of the greatest artists of the century during his formative years. Rubens' brilliant and descriptive brushwork in the panel has much in common with his oil sketches, another strength of the collection. The Getty's collection also includes one of the largest holdings of drawings by Rubens in the U.S., ranging from early examples such as Anatomical Study (about 1600-05) to the magnificent Assumption of the Virgin (about 1624).

Depicting the mythological hunt as told by Ovid, the painting is the artist's first treatment of this classical combat between men and beast, a rare subject in the 1600s. With this work, Rubens established a new genre, combining Flemish naturalism with Italian classical influences. Painted on his return from Italy, The Calydonian Boar Hunt reflects Rubens' study of statues from antiquity and reliefs on Roman sarcophagi, which informed the pose of his subjects and the tight composition of his scene.

Portraying the climactic instant when Meleager thrusts a spear into the boar, surrounded by robust hunters and the bloodied form of a fallen warrior, the painting is a superb expression of the Baroque style in its ability to depict emotion through action. It epitomizes the dramatic, powerful style Rubens brought to his battle scenes and his subjects from history. Combining dazzling brushwork and chiaroscuro light effects, the picture features two dynamic horses influenced by an awareness of Leonardo da Vinci. The Calydonian Boar Hunt shows Rubens at his most daring and inventive. It is thought that Rubens retained this painting in his studio as inspiration as he continued to develop the theme of the boar hunt and related subjects through the years.

Born in 1577, Peter Paul Rubens rose to become the preeminent painter in Antwerp, forging a bold style that earned him an international reputation and major public commissions. He embarked on an influential eight-year sojourn in Italy in 1600, where he served as court painter to the Duke of Mantua. Over the years Rubens worked across Europe, producing paintings for the rulers of France, England, and Spain, among others.

A Unique Collaboration

Peter Paul Rubens and Jan Brueghel the Elder were the most eminent painters in Antwerp, in present-day Belgium, during the first two decades of the 17th century. While it was common practice in the Netherlands around 1600 for two or more artists to contribute to a single composition, Rubens and Brueghel's partnership was extraordinary.

There are a few collaborative paintings by Rubens and Brueghel. It is their joint work which makes these paintings unique, and consider how these two great artists were able to work together. The results of recent technical analysis provide new insight into their collaborative working method.

Both painters served the Brussels court of the joint Habsburg regents of the Southern Netherlands, Archduke Albert and Archduchess Isabella. Fond friends, both in and out of the studio, Rubens and Brueghel accommodated each other's preferences and modified each other's contributions. While it has often been assumed that Rubens was the dominant partner, in fact it was Brueghel, senior by nine years, who often took the lead.

The two artists had distinctive individual styles. Brueghel was a renowned still-life and landscape specialist known for highly detailed works, while Rubens created large-scale history paintings. Brought together in the same painting, these individual styles result in highly inventive compositions. The rich context for joint productions in Antwerp is represented in the exhibition by Rubens and Brueghel's collaborative works with important contemporaries.

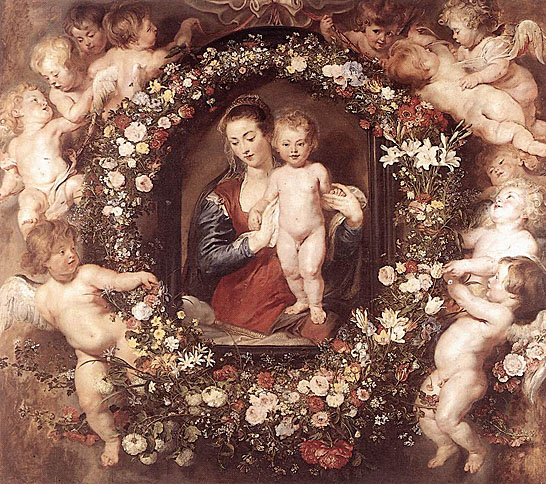

Collaboration of Jan Brueghel the Elder and Peter Paul Rubens

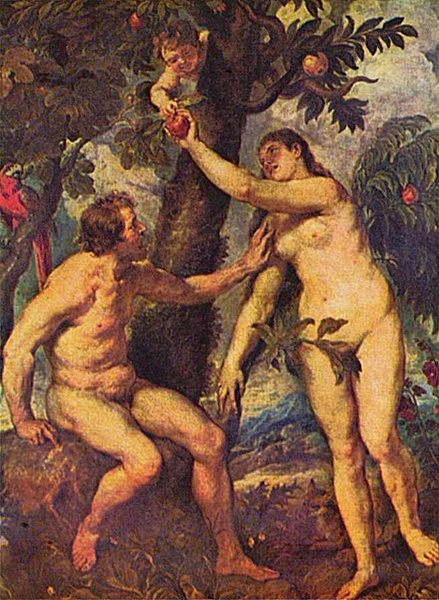

The Garden of Evil With the Fall of Man

The Return From War: Mars Disarmed by Venus

Vision of Saint Hubert

This painting is a fruit of collaboration between Rubens and Jan Brueghel, the former being responsible for the figures and the latter for the landscape.

St Hubert was born in the middle of the seventh century, son of a Duke of Aquitaine. He was elected as Bishop of Maastricht around 705. Later he was transferred to Liege, becoming its first bishop, and evangelized the Ardennes.

At the end of the middle ages, his life was enriched with a number of episodes borrowed from the legend of St Eustace, in particular his encounter with a miraculous stag. One Good Friday Hubert, a fearsome hunter, fell upon a stag with a crucified Christ between its antlers. Blinded in the manner of St Paul on the road to Damascus, he fell from his horse and knelt down. He heard a voice, "Hubert, Hubert, why do you pursue me? Will your love of hunting make you forever forgetful of your salvation?" Hubert immediately changed his life and retired to the forest of Ardennes. He then succeeded St Lambert as Bishop of Maastricht and performed numerous miracles. St Hubert now is the patron saint of hunters, and protector of hunting dogs.

Virgin and Child Surrounded by Flower and Fruit

This painting is the result of collaboration between Rubens and Jan Brueghel, the former being responsible for the figures and the latter for the flowers and fruit.

Battle of the Amazons: 1618

After becoming a master in 1678, Rubens also produced paintings in addition to graphic works. His earliest work was very similar in style to that of Van Veen. This is apparent from the rare juvenilia which can on good grounds be ascribed to Rubens, such as the Battle of the Amazons in Potsdam. The classicist portrayal of the characters goes back to Van Veen, but bears witness to a better anatomical insight than is often the case with him.

The Battle of the Amazons shows small figures in a landscape by Jan Brueghel, here Rubens followed the earlier and specifically Antwerp tradition of sharing out the tasks in landscapes with figures.

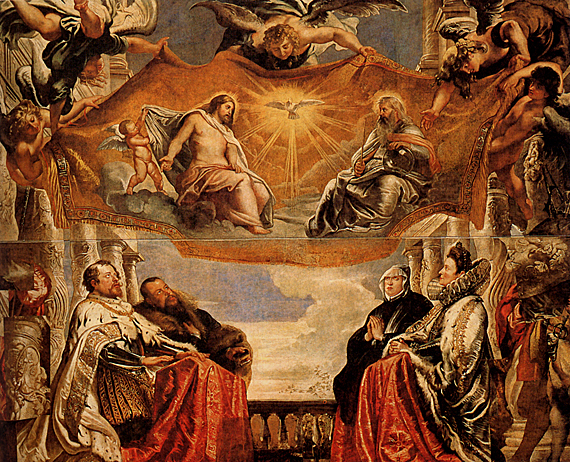

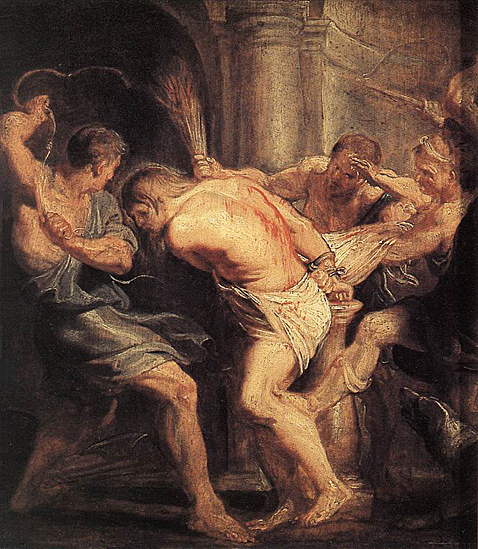

RELIGIOUS SUBJECTS

Adoration of the Shepherds: ca 1608

Rubens worked in Italy from 1600 to 1608 before returning to Antwerp. This masterpiece, commissioned for the church of San Filippo in Fermo, dates from the last year of his stay, while he was working in Rome for the Congregation of St. Philip Neri, and is one of his finest works from this period.

Its lighting, naturalism and human power owes much to the influence of Caravaggio and documents a significant development in Rubens' work.

Bathsheba at the Fountain: ca 1635

Rubens depicts Bathsheba at her toilet, sitting at a fountain. A messenger is shown arriving with a letter sent by King David who is barely visible at the upper left corner of the painting.

Christ at Simon the Pharisee: 1618-20

According to the Bible (Luke 7:40-50) Simon the Pharisee invited Jesus to share a meal. He received Jesus in his home. While they were at table, a sinner, occasionally taken wrongly to be Mary Magdalene, came and poured ointment over Jesus' feet.

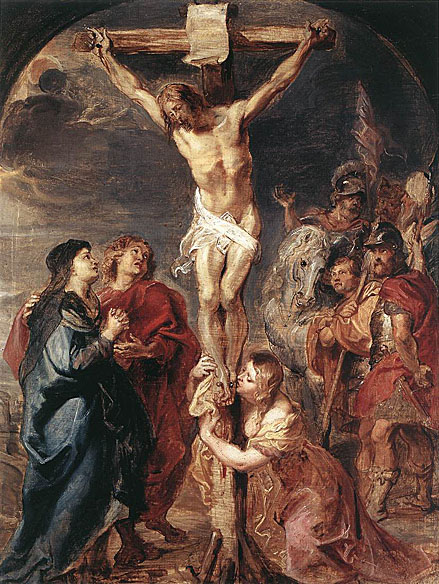

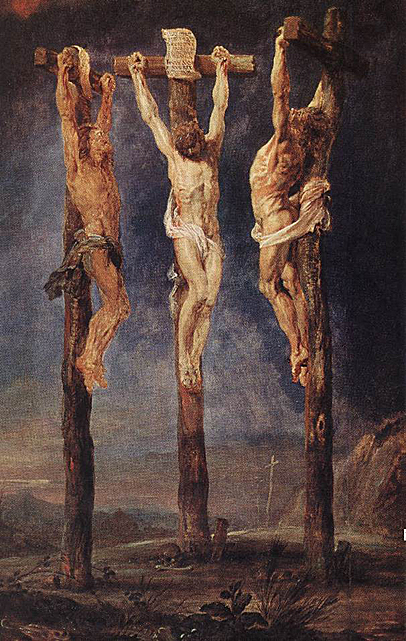

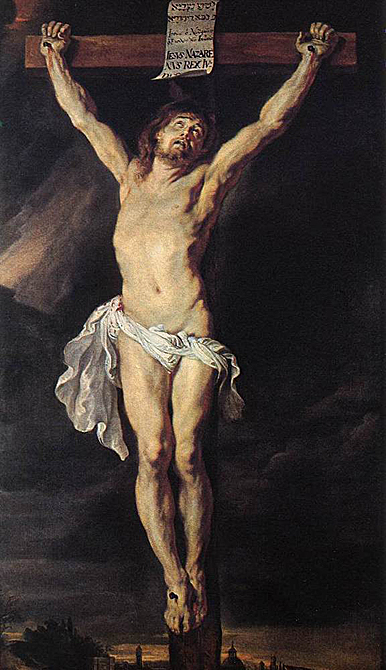

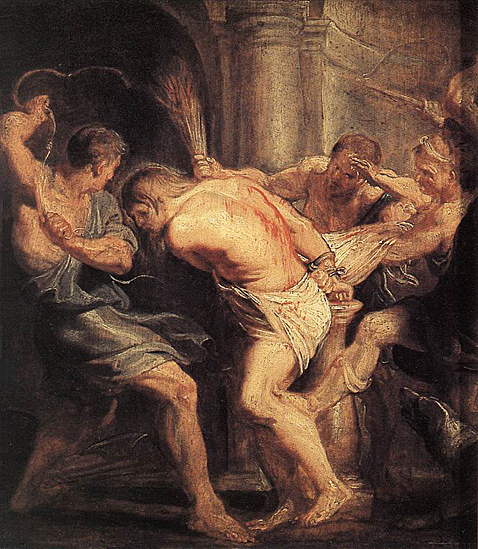

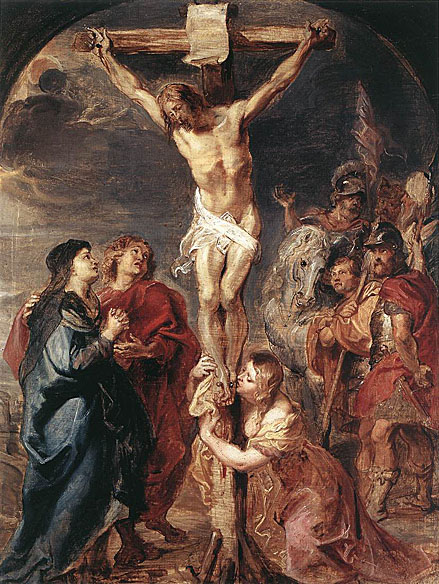

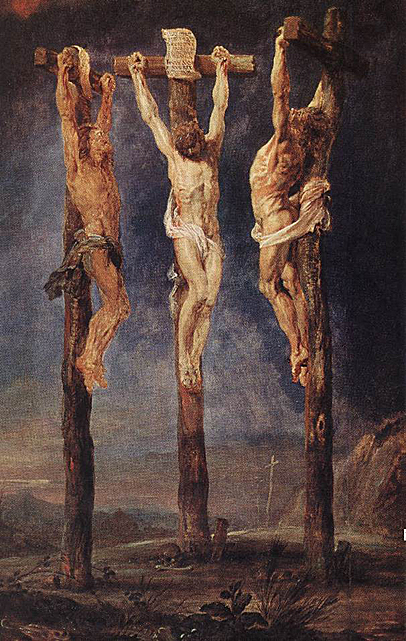

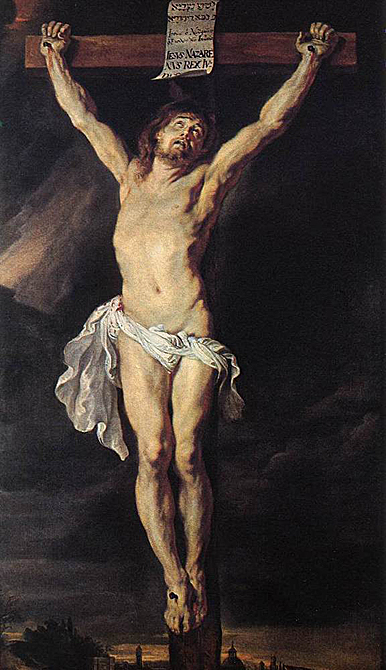

Christ on the Cross between the Two Thieves: 1620

Rubens' close involvement with the resurgence of Catholicism and the struggle for power led to the production a numerous large altarpieces. His stirring baroque ideas come to the fore in The Lance, with its emotionally charged, highly plastic figures.

Daniel in the Lions Den: ca 1615

The Old Testament prophet Daniel, as chief counselor to the Persian king Darius, aroused the envy of the other royal ministers. Conspiring against the young Hebrew, they forced the king into condemning Daniel to a den of lions. The following dawn, Darius, anxious about his friend, had the stone that sealed the entrance rolled away to discover that Daniel had been miraculously saved. Rubens depicted the moment when, as the beasts squint and yawn at the morning light streaming into their lair, Daniel gives thanks to God.

The monumental size of the ten lions and their placement close to the viewer heighten the sense of immediacy. Within the asymmetrical baroque design, Daniel is the focal point. Against the brown tones of animals and rocks, his pale flesh is accented by his red and white robes as well as by the blue sky and green vines overhead.