English Rococo Painter, Collector & Writer

1723 - 1792

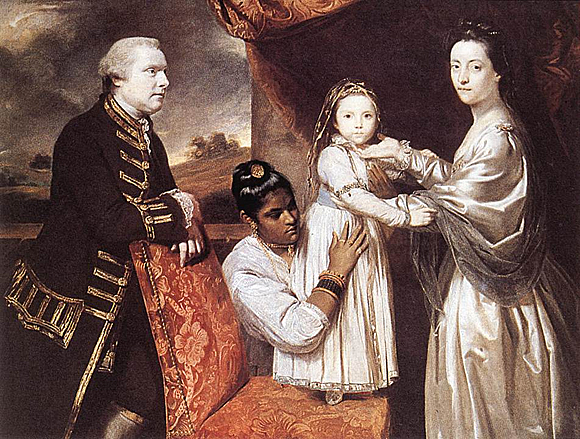

Sir Joshua Reynolds was one of the most important and influential of 18th century English painters, specializing in portraits and promoting the "Grand Style" in painting which depended on idealization of the imperfect. He was one of the founders and first President of the Royal Academy. George III appreciated his merits and knighted him in 1769.

Reynolds was born in Plympton, Devon, on 16 July 1723. As one of eleven children, and the son of the village school-master, Reynolds was restricted to a formal education provided by his father. He exhibited a natural curiosity and, as a boy, came under the influence of Zachariah Mudge, whose Platonic Philosophy stayed with him all his life.

Showing an early interest in art, Reynolds was apprenticed in 1740 to the fashionable portrait painter Thomas Hudson, with whom he remained until 1743. From 1749 to 1752, he spent over two years in Italy, where he studied the Old Masters and acquired a taste for the "Grand Style". Unfortunately, while in Rome, Reynolds suffered a severe cold which left him partially deaf and, as a result, he began to carry a small ear trumpet with which he is often pictured. From 1753 until the end of his life he lived in London, his talents gaining recognition soon after his arrival in France.

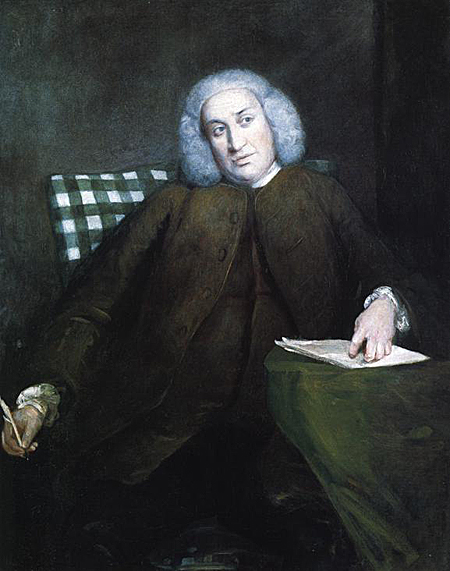

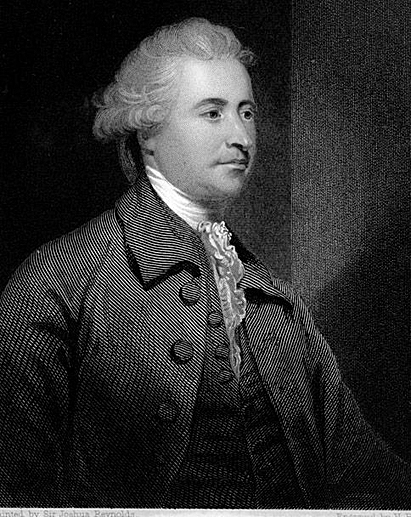

Reynolds worked long hours in his studio, rarely taking a holiday. He was both gregarious and keenly intellectual, with a great number of friends from London's intelligentsia, numbered among whom were Dr. Samuel Johnson, Oliver Goldsmith, Edmund Burke, Giuseppe Baretti, Henry Thrale, David Garrick and fellow artist Angelica Kauffmann. Because of his popularity as a portrait painter, Reynolds enjoyed constant interaction with the wealthy and famous men and women of the day, and it was he who first brought together the famous figures of "The" Club.

Burke exerted a tremendous influence upon Reynolds, shaping his views on philosophy and politics. It was also Burke who effectively transformed Reynolds from an artist with sympathy for Whig ideals into the 'principal painter' to the Whig party.

Reynolds presents Baretti as a myopic scholar, in an attempt to counteract his public image which was still colored by his trial for murder in 1769. Baretti narrowly escaped hanging after stabbing a pimp to death in a violent street brawl.

In the event the portrait was not hung with the other portraits in the library - on the pretext that her husband did not like it.

Garrick practically ceased to act in 1766, but he continued the management of Drury Lane. In 1776 he sold his share in the property, and took leave of the stage by playing a round of his favorite characters.

With his rival Thomas Gainsborough, Reynolds was the dominant English portraitist of 'the Age of Johnson'. It is said that in his long life he painted as many as three thousand portraits. In 1789 he lost the sight of his left eye, which finally forced him into retirement and, on 23 February 1792, he died in his house in Leicester Fields, London. He is buried in St. Paul's Cathedral.

Professionally, Reynolds' career never peaked. He was one of the earliest members of the Royal Society of Arts and, with Gainsborough, established the Royal Academy of Arts as a spin-off organization. In 1768 he was made the RA's first President, a position he held until his death. As a lecturer, Reynolds' Discourses on Art (delivered between 1769 and 1790) are remembered for their sensitivity and perception. In one of these lectures he was of the opinion that "invention, strictly speaking, is little more than a new combination of those images which have been previously gathered and deposited in the memory."

Reynolds and the Royal Academy have historically received a mixed reception. Critics include many of the Pre-Raphaelites, and William Blake, the latter having published his vitriolic Annotations to Sir Joshua Reynolds' Discourses in 1808. To the contrary, both J. M. W. Turner and James Northcote were fervent acolytes: Turner requested he be laid to rest at Reynolds' side, and Northcote (who lived for four years as Reynolds' pupil) wrote to his family "I know him thoroughly, and all his faults, I am sure, and yet almost worship him." The word worship is second cast; originally Northcote had written adore.

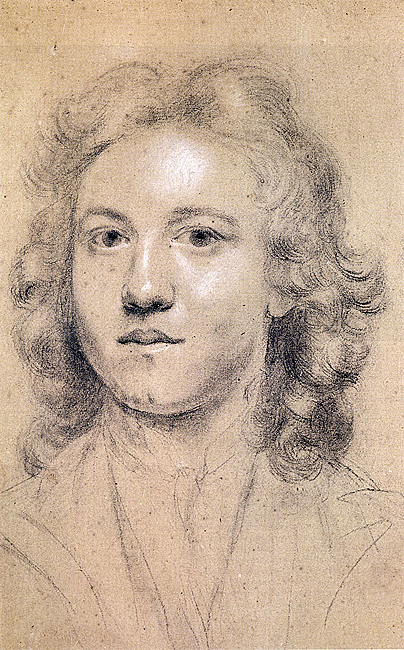

In appearance Reynolds was not at all striking. Slight of frame, he was just about 5'6" with dark brown curls, a florid complexion and features which James Boswell thought were "rather too largely and strongly limned. " He had a broad face, a cleft chin, and the bridge of his nose was slightly dented; his skin was scarred by smallpox, and his upper lip disfigured as a result of falling from a horse as a young man. Nonetheless he was not considered ugly, and Edmond Malone asserted that "his appearance at first sight impressed the spectator with the idea of a well-born and well-bred English gentleman."

Renowned for his calm and peaceful nature, Reynolds often claimed that he "hated nobody". Never quite losing his Devonshire accent, he was not only an amiable and original conversationalist but a friendly and generous host, so that Fanny Burney recorded in her diary that he had "a suavity of disposition that set everybody at their ease in his society", and William Makepeace Thackeray believed "of all the polite men of that age, Joshua Reynolds was the finest gentleman." Dr. Johnson commented on the inoffensiveness of his nature; Edmund Burke noted his "strong turn for humor". Thomas Bernard, who later became Bishop of Killaloe, wrote in his verses on Reynolds :

Thou say'st not only skill is gained

But genius too may be attained

By studious imitation;

Thy temper mild, thy genius fine

I'll copy till I make them mine

By constant application."

Admittedly, some did construe Reynolds' equable calm as cool and unfeeling. Hester Lynch Piozzi's pen-portrait reads:

It is to this luke-warm temperament that Frederick W. Hilles, Bodman Professor of English Literature at Yale attributes the fact Reynolds never married. In the editorial notes of his compendium Portraits by Sir Joshua Reynolds, Hilles theorizes that "as a corollary one might say that he (Reynolds) was somewhat lacking in a capacity for love", and cites Boswell's notary papers:

"He said that the reason he would never marry was that every woman whom he liked had grown indifferent to him, and he had been glad he did not marry her."

Reynolds' own sister, Frances, who lived with him as housekeeper, took her own negative opinion further still, thinking him "a gloomy tyrant". Strangely, it was this very presence of family that compensated Reynolds for the absence of a wife. He wrote on one occasion to his friend Bennet Langton, that both his sister and niece were away from home "so that I am quite a bachelor." Biographer Ian McIntyre discusses the possibility of Reynolds having enjoyed sexual rendezvous with certain clients, such as Nelly O'Brien (or "My Lady O'Brien", as he playfully dubbed her) and Kitty Fisher, who visited his house for more sittings than were strictly necessary. Claims to this end are, however, purely speculative.

It has often been laid down as the law that the artist, whether in paint or in words, who works for money and caters for the popular taste sacrifices thereby the richer treasures of his genius. Instances abound in proof of this rule; but it may be said of Sir Joshua Reynolds that he was largely an exception to it. Even if we argue that his work does not attain the supreme height of genius, there is still enough of that elusive quality in it to make his case remarkable.

Sir Joshua Reynolds was perhaps the most popular portrait painter who ever lived. The world of fashion flocked in crowds to his studio, and it is amazing that, with all the claims upon his time, both by his sitters for portraits, and by the work entailed by the preparation of his Discourses on Art, he should still have found leisure for producing such subject pictures as "The Strawberry Girl" or his charming "Heads of Angels," in which he depicts the tender graces of perfect childhood.

"The Strawberry Girl" was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1773, and was described by Reynolds himself as "one of the half-dozen original things which no man ever exceeded in his life work."

Ferguson believed in the progress of humankind, and used his knowledge of the classical world to advance arguments on the ameliorative nature of society. He had much in common with Reynolds's immediate intellectual circle, which may have prompted him to commission this portrait.

Born on October 3, 1767 at St James Square, London, he was educated at Harrow School and at Christ Church, Oxford University.

Hamilton was a Whig, and his political career began in 1802, when he became MP for Lancaster. He remained in the House of Commons until 1806, when he was appointed to the Privy Council, and Ambassador to the court of Saint Petersburg until 1807; additionally, he was Lord Lieutenant of Lanarkshire from 1802 to 1852. He received the numerous titles at his father's death in 1819. He was Lord High Steward at King William IV's coronation in 1831 and Queen Victoria's coronation in 1838, and remains the last person to have undertaken this duty twice. He became a Knight of the Garter in 1836. He held the office of Grand Master of the Freemasons (Scotland) between 1820 and 1822. He held the office of President of the Highland and Agricultural Society (Scotland) between 1827 and 1831. He held the office of Trustee of the British Museum between 1834 and 1852.

He married Susan Euphemia Beckford, daughter of William Beckford and Lady Margaret Gordon, on 26 April 1810 in London, England.

Hamilton was a well-known dandy of his day. An obituary notice states that "timidity and variableness of temperament prevented his rendering much service to, or being much relied on by his party ... With a great predisposition to over-estimate the importance of ancient birth ... he well deserved to be considered the proudest man in England."

Lord Lamington, in The Days of the Dandies, wrote of him that 'never was such a magnifico as the 10th Duke, the Ambassador to the Empress Catherine; when I knew him he was very old, but held himself straight as any grenadier. He was always dressed in a military laced undress coat, tights and Hessian boots. Lady Stafford in letters to her son mentioned 'his great Coat, long Queue, and Fingers covered with gold Rings', and his foreign appearance. According to another obituary, this time in Gentleman's Magazine he had 'an intense family pride'.

Hamilton had a strong interest in Ancient Egyptian mummies, and was so impressed with the work of mummy expert Thomas Pettigrew that he arranged for Pettigrew to mummify him after his death. He died on August 18, 1852 at age 84 at 12 Portman Square, London, England and was buried on September 4, 1852 at Hamilton Palace, Hamilton, Scotland. In accordance with his wishes, Hamilton's body was mummified after his death and placed in a sarcophagus on his estate.

His collection of paintings, objects, books and manuscripts was sold for £397,562 in July 1882. The manuscripts were purchased by the German government for £80,000. Some were repurchased by the British government and are now in the British Museum.

The sitter was the mother of Reynolds's friend Commodore (later Admiral) Keppel, with whom he sailed to Italy in 1749.

The closely wrapped black shawl suggests her status as a widow, and her occupation is that of 'knotting', a fashionable occupation of the time akin to crochet work.

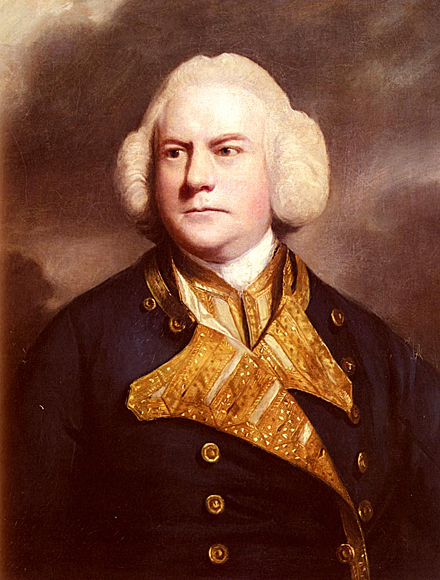

Montgomerie was educated at Eton College and Winchester School. He joined the Army in 1743, becoming a major general in 1772, a lieutenant general in 1777 and a general in 1793.

During his army career Montgomerie raised a Highland battalion. He participated along with George Washington in the Forbes expedition against Fort Duquesne in 1758. In 1760, he commanded an expedition against the Cherokee during the Anglo-Cherokee War.

He was elected for two seats in the 1761 general election. He chose to give up Wigtown Burghs, to sit for Ayrshire. He served in the House of Commons 1761-1768.

He inherited the Earldom on 25 October, 1769 when his brother Alexander Montgomerie, 10th Earl of Eglinton was murdered. He served as a Scottish representative peer 1776-1796. He was Lord Lieutenant of Ayrshire 1794-1796.

On his death the Earldom passed to a third cousin, Hugh Montgomerie, 12th Earl of Eglinton.

This portrait, painted immediately after Reynolds's return from Italy in 1752, was one of his most important early works. The pose, based on a drawing Reynolds had made of a statue of Apollo, emphasizes Keppel's heroic qualities.

.jpg)

Significantly, the scene in the distance is not, as you might expect, a celebrated military victory. Instead it shows a catastrophic defeat by the French army near the Monongahela River in America, in the summer of 1755. Nearly nine hundred British and American soldiers were slaughtered; Orme, though shot in the leg, survived.

Burney had been awarded a doctorate in music by the University of Oxford in 1769, and is shown in his academic robes. Unusually, Reynolds painted this portrait in the Thrales' house at Streatham rather than his own studio.

In 1765 he was appointed British ambassador extraordinary in Paris, and in the following year he became a secretary of state.

The Duke was a firm supporter of the American colonists; and he initiated the debate of 1778 calling for the removal of troops from America.

He opened, in March 1758, at his house in Whitehall, a gallery of casts of antique statues where students could draw under the direction of Wilton and Cipriani. He soon lost interest and the gallery was closed in either 1765 or 1766. He was a member of the Society of Dilettanti. Richmond died in December 1806, and, leaving no legitimate children, he was succeeded in the peerage by his nephew Charles, son of his brother, General Lord George Henry Lennox.

Rogers had some reservations about the portrait and he later wrote to Walpole that he thought it made him look too young. Walpole responded that 'posterity will not know at what age the Likeness was taken'.

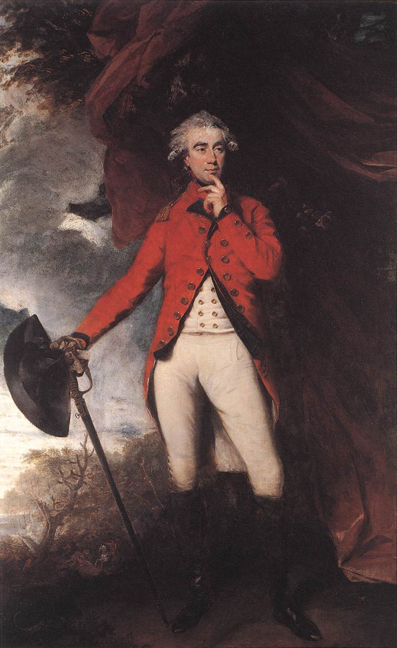

This work was painted in 1782. Tarleton is in the uniform of a troop, raised during the American campaign, known as the British Legion or (for the cavalry part) Tarleton's Green Horse, of which he was commandant.

It is assumed that the flag above him is of the British Legion. In 1781 Tarleton lost two fingers of his right hand, as Reynolds discreetly shows.

In 1747, at the age of fifteen, she married the immensely wealthy James FitzGerald, 20th Earl of Kildare, and went to live in Ireland.

The marriage was a happy one, despite Lord Kildare's inability to be sexually faithful. The couple had nineteen children.

The Sheriff of Devon was father to Sir Edward Seymour, 1st Baronet of Berry Pomeroy, grandfather of Sir Edward Seymour, 2nd Baronet of Berry Pomeroy, great-grandfather of Sir Edward Seymour, 3rd Baronet of Berry Pomeroy and a fourth-generation ancestor of Sir Edward Seymour, 4th Baronet of Berry Pomeroy.

The 4th Baronet was father to Sir Edward Seymour, 5th Baronet of Berry Pomeroy and grandfather to Edward Seymour, 8th Duke of Somerset. His younger son was Francis Seymour-Conway, 1st Lord Conway (1679-1732).

Lord Conway married Charlotte Shorter, a daughter of John Shorter of Bybrook. They were the parents of the Marquess. His father died when the younger Francis was about fourteen years old. The first few years after his father's death were spent in Italy and Paris. On his return to England he took his seat, as 2nd Baron Conway, among the Peers in November 1739.

The time was one of the greatest difficulty for while the calm of the country was disturbed by the American rebellion, it was drained of regular troops, and large bands of volunteers not under the control of the government had been formed. Nevertheless, the two years of Carlisle's rule passed in quietness and prosperity, and the institution of a national bank and other measures which he affected left permanently beneficial results upon the commerce of the island. In 1789, in the discussions as to the regency, Carlisle took a prominent part on the side of the Prince of Wales.

In 1791 he opposed William Pitt the Younger's policy of resistance to the dismemberment of the Ottoman Empire by Imperial Russia; but on the outbreak of the French Revolution he left the opposition and vigorously maintained the cause of war. He resigned from the Order of the Thistle and was created a Knight of the Garter in 1793. In 1815 he opposed the enactment of the Corn Laws; but from this time till his death, he took no important part in public life.

Reynolds deliberately imposed on his compositions certain formal artistic qualities that would give them the solidity and nobility of Greek, Roman, and Renaissance art. He also liked to suggest associations in his portraits that elevate them to some level beyond the merely descriptive. Roses are symbolically related to Venus and the Three Graces, and Reynolds may well have intended to allude to their attributes, Chastity, Beauty, and Love, as ideals to which Lady Caroline should aspire.

Lady Caroline's father affectionately described his daughter as a determined, strong-minded child whose need for discipline he met fairly but reluctantly. He wrote that she was "always a great favorite," suggesting that her spirited personality made her faults tolerable. Reynolds captured some of Lady Caroline's complexity in the serious, intent expression of her attractive face, her averted gaze, and the tension implied in her closed left hand.

Spencer, the son of John Spencer, 1st Earl Spencer was born in 1758 in Wimbledon and was baptized there on the 16 October 1758. His godparents were King George II, Earl Cowper (his grandmother's second husband) and his great-aunt the Dowager Viscountess Bateman. He was educated at Harrow School from 1770 to 1775 and he won the school's Silver Arrow (an archery prize) in 1771. He then attended Trinity College, Cambridge from 1776 1778 and graduated with a Master of Arts. Spencer was Whig MP for Northampton from 1780 to 1782 and Whig MP for Surrey from 1782 to 1783. On March 6, 1781, he married Lady Lavinia Bingham (1762-1831), daughter of Charles Bingham, 1st Earl of Lucan and they had nine children.

He served under Pitt as First Lord of the Admiralty from 1794 to 1801, and then in the Ministry of All the Talents as Home Secretary. He was noted for his interest in literature. His son Lord Althorp was one of the chief architects of the passage of the Great Reform Bill in 1832. His sister Georgiana married the Duke of Devonshire and became a famed Whig hostess. Spencer was also High Steward of Saint Albans from 1783 to 1807, Mayor of Sait Albans in 1790, President of the Royal Institution from 1813 to 1825 and Commissioner of the Public Records in 1831.

He died in 1834, aged 76 at Althorp and was buried in the nearby village of Great Brington on November 19 of that year.

When the 22 year old George Spencer met the gorgeous Lavinia Bingham he became "out of his senses" for her. And why not? She was a blonde with blue eyes, intelligent, personable, and had memorized the book on etiquette (a real win-over for Lady Spencer). Despite his young age and her lack of wealth, Georgiana's brother and Lavinia wed. Now instead of being a daughter of a mere Irish peer she was destined to be the Countess Spencer.

But the monster that lay within Lavinia was vicious; she was two-faced and a hypocrite. She also was very territorial of her man. Anything that came between her and George met the wrath of Lavinia, and this included his two sisters. She made scathing remarks about Georgiana's part in the Westminster election and like a competing child in the schoolyard, seemed to relish in Charles Fox's defeats. Like Georgiana, Lavinia followed politics. Instead of bonding with her sister-in-law over their similar interests, Lavinia spent a lot of her time criticizing her. George must have dearly loved her, for her letters to him throughout their marriage are scathingly critical of Georgiana. It was likely she was just envious of her popularity. Lavinia had made attempts at being a successful socialite. She once tried to rile woman together to erect a statue of a nude Achilles in tribute to the Duke of Wellington. Interesting choice of tribute, Lady S...

She had her opinions on Bess as well, "I really look upon her in every light as the most dangerous devil..." Bess, who usually complimented everyone in her web a manipulation, felt similarly about Lavinia, "Lady S seemed to raise herself three feet in order to look down with contempt on me..." The bitter Lavinia, years later, even went as far as insulting Bess' son, claiming he was "dull as a post." Meow! I'm sure there was a couple rakes who would have loved to see a cat fight break out between those two!

Despite Lavinia previously complaining about London being so odious due to the importance that was put on parties (she was probably put out by not being invited to Georgiana's) she seemed to have finally buried the hatchet with her sister-in-law in the final years of Georgiana's life in order to plan one. The two ladies threw a political ball, finally bringing their similar interests together. When the Duke went on to marry Bess after Georgiana's death, it was Lavinia who insisted they sever all ties. Of course she was probably just happy to finally have an excuse!

Lady Elizabeth Foster, closest friend of Georgiana, later the Duchess of Devonshire. She lived together with the 5th Duke of Devonshire and Georgiana, the Duchess, bearing the Duke two children. After Georgiana's death she married the Duke.

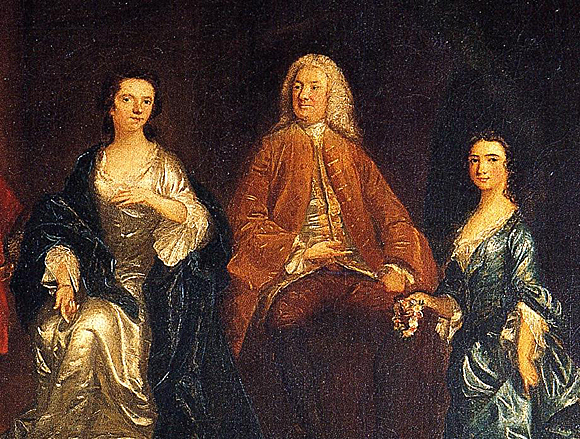

Georgiana, Countess Spencer - her mother. On the portrait she is with Georgiana future Duchess of Devonshire as a child.

George John Spencer, 2nd Earl Spencer - her brother

Then into her life and that of her husband, came Lady Elizabeth Foster who was not only to remain her closest friend and confidante for the rest of the Duchess's life but also her husband's mistress. For over twenty years the three lived together with a harmony only interrupted by Lady Elizabeth's departure abroad to give birth to the Duke's children, and Georgiana's own banishment to Europe when she was carrying a baby by Charles Grey, later to be Prime Minister. The various offspring, legitimate and illegitimate, made for a complicated nursery."

"Her husband was John Russel, 4th Duke of Bedford (1710-1771) a British statesman. He was the second son of Wriothesley Russell, 2nd Duke of Bedford, and his wife, Elizabeth, daughter and heiress of John Howland of Streatham, Surrey. In 1731 Lord John Russell married Lady Diana Spencer (d. 1735), daughter of Charles Spencer, 3rd Earl of Sunderland. A year later, after his elder brother's death he became Duke of Bedford. In April 1737 he married Lady Gertrude Leveson-Gower (d. 1794), daughter of John Leveson-Gower, 1st Earl Gower."

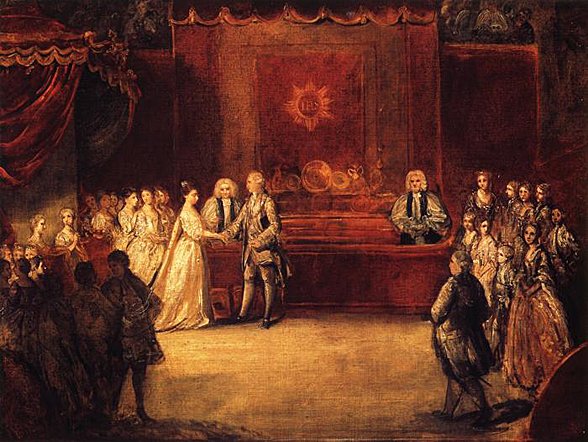

In 1747, on the occasion of his marriage to Lady Emily Lennox, daughter of the 2nd Duke of Richmond, he was in the Peerage of Great Britain created Viscount Leinster, of Taplow in the County of Buckingham, and took his seat at Westminster that same year. From 1749 to 1755 he was one of the leaders of the Popular Party in Ireland, and served as the country's Master-General of the Ordnance between 1758 and 1766, becoming Colonel of the Royal Irish Artillery in 1760.

In 1761 Lord Kildare was created Marquess of Kildare and Earl of Offaly in the Peerage of Ireland, and in 1766 he was created Duke of Leinster, becoming by this time the Premier Duke, Marquess and Earl in the Peerage of Ireland. This followed from his marriage to Emily, who was descended from King Charles II and was therefore a cousin of King George III.

His eldest surviving son, William, Marquess of Kildare, succeeded as 2nd Duke of Leinster, his third son, Lord Charles FitzGerald, was created Baron Lecale in the Peerage of Ireland in 1800, and his fifth son was the Irish revolutionary Lord Edward FitzGerald.

Leinster died aged 51 at Leinster House in Dublin, and was buried in the city's Christ Church Cathedral.

Burgoyne was known as 'Gentleman Johnny' for his good manners and affability. Appropriately, Reynolds has fused the pictorial languages of aristocratic poise and military command.

If Granby played hard, he worked hard too. He showed himself to be an able and frequently victorious commander and he was never afraid to lead by example from the front. The cavalry charge which he led against the French at the Battle of Warburg on 31 July 1760 caused his hat and wig to blow off, giving rise to the expression '... to go at [something] bald-headed'.

But Granby had a reputation for looking after his men, and the public idolized him for this common touch as much as for his personal bravery. Engravings of this painting showing Granby giving alms to a sick soldier sold hand over fist, but perhaps the most enduring testament to his popularity is the number of pubs opened by retired soldiers that were and still are named after him.

The blasted tree-trunk shows signs of natural regeneration: the leaves and the flowers emerging from the old tree. This imagery suggested that the Highlands, brutalized during the terrible repression of 1746-7, were now being restored to order by a new generation of Scottish noblemen loyal to the crown - like Murray himself.

Expressing nostalgia for the values of days gone by is common to an older generation. We hear and read about the need to return to values of previous times without, in many cases, any clear definition of what those values might be. In reaction to change, older people often simply declare that things used to be better.

But is it really a question of whose values are correct? Indeed, do any values represent a correct standard, or are values of themselves relative? If so, should we accept that they can and will differ from one generation to the next?

The nature of the generational differences is in the way we view values themselves. The word value can have a broad range of meaning; in a cultural sense it refers to a principle, standard or quality. A desire to return to past values generally means a return to principles and standards held by society at large in previous decades. However, another meaning of value that needs to be considered is "the desirability or worth of a thing." If this meaning is applied to cultural values, then we introduce a moving target, because such a definition implies variation over time.

The perceived value of something differs from person to person and may reasonably change. For example, do we really want to return to the days of men wearing three-piece suits to baseball games? Would it be better if women still wore girdles and white gloves when they left the house? It would be ludicrous to think in these terms to find solutions to generational differences today. But here is the catch: While certain values cannot be replicated today, the principles, standards and qualities they reflect may well be desirable and downright helpful to a younger generation. How can we improve our principles and standards without all the baggage that can come with trying to recapture the values of a previous time?

Author Jeremy Rifkin describes the problem in his book The Age of Access: "The world . . . has become a human construct. . . . This new world is not objective but rather contingent, not made up of truths, but rather options and scenarios. Reality, it seems, is not something bequeathed to us but rather something we create. . . ."

James Davison Hunter says it quite plainly in his book The Death of Character: "Values are truths that have been deprived of their commanding character."

To address issues in terms of values makes it difficult, if not impossible, for the generations to be drawn together on common ground. Successive generations have created their own values as cultural influences have progressively emphasized the importance of self.

Perhaps a change of focus would be helpful. Instead of addressing values, which are relative, why not think in terms of ethics? Ethics refers to principles of right and wrong, especially in relation to specific moral choices that affect others. Right and wrong become anchor points that keep us from being drawn in by the relativity of values.

Of course, this necessitates some clear and indisputable definitions of right and wrong. The standard for moral choices in regard to relationships with others was written a long time ago.

Ethics based on principles provide a basis for defining right and wrong. From these, each generation can enjoy individual development and progress, but the commonality of these principles allows successive generations to share them as well.

How much happier would relationships be if we were prepared to question the evolving cultural values that have shaped us and to accept a common set of ethical standards? Ethics that transcend humanly devised morality benefit people of all ages simultaneously.

Nostalgia for days gone by might lessen if young and old could enjoy their differences because of shared underlying principles of right and wrong.

BRIAN ORCHARD

Lucy Locket lost her pocket,

Kitty Fisher found it;

Not a penny was there in it,

Only ribbon 'round it.

The tune for Lucy Locket was later used as the basis for Yankee Doodle, a song which originated in Norwalk, Connecticut.

Lucy Locket was a barmaid at the Cock, in Fleet Street, London, sometime in the 1700's. Lucy discarded one of her lovers (her 'pocket') when she had run through all his money. Kitty Fisher, a noted courtesan, took up with him, even though he had no money. It also taunts Lucy Locket because a "pocket" was what prostitutes kept their money in and would tie to their thigh with a ribbon.

Amabel Hume-Campbell, 1st Countess de Grey and 5th Baroness Lucas was a political writer.

Born Amabel Yorke, she was the eldest of the two daughters of The Honorable Philip Yorke and his wife, Jemima Yorke, 2nd Marchioness Grey. When her father inherited the earldom of Hardwicke in 1764, she was entitled to the nominal prefix, Lady.

Amabel grew up in the political and intellectual atmosphere of her parents' homes at Wrest Park, Bedfordshire, and Saint James's Square, Westminster. She was educated at home, and became an avid reader; her mother's friend, the scholar Catherine Talbot, said of her that, aged five, she "has no joy but in books, and of those will not read little idle stories such as were first given to her, but picks out for herself. Her knowledge in geography and English history is astonishing". Walpole later wrote that her sister, Mary, "behaved like a human creature, and not like her sister or a college-tutor".

On 16 July 1772, at Saint James's, Amabel married Alexander Hume-Campbell, Viscount Polwarth (1750-1781), the eldest surviving son of Hugh Hume-Campbell, 3rd Earl of Marchmont, and his second wife, Elizabeth; it appears to have been a love match. Polwarth was interested in books but was a keen hunter too and also established a model farm on the Bedfordshire estate, to which Amabel was coheir. In 1776, he was created Baron Hume of Berwick. In 1777, his health began to fail, and after a long decline, he died on 9 March 1781. In her diary, kept from 1769 to 1827, Amabel mourned the loss of "the friend & protector I had hoped for". She then divided her time between Wrest, London, and (from 1791) her villa on Putney Heath, with London usually accounting for about half the year. On the death of her mother in 1797, she inherited the family houses at Wrest and 4 St. James's Square, and the title Baroness Lucas. In 1816, she was created Countess de Grey, of Wrest, in the County of Bedford, with a special remainder, failing heirs male of her body, to her sister and the heirs male of her body.

The countess's diary and her correspondence reveal an intense interest in politics. It was a matter of lifelong frustration that, being a woman, she could not be elected to the Commons or, later, take her place in the House of Lords. She told her mother on 21 November 1775 that if she were in Parliament, she would certainly have voted for the Rockingham party's amendments to the Militia Bill, and in 1811, she wrote:

"I can only flutter & beat against the wires of my large gilded cage in Saint James Square while I embody in my reveries an imaginary Marquis de Grey speaking in Parliament. But alas! When I wake from my day-dreams, I find out that my poor Marquis (with my soul in a manly form) would probably have had a bullet in the thorax...long ago for the vehemence of his speeches."

She described herself as "an old English Whig" and her views were dominated by a desire not to upset the status quo. She noted that "most Reformers, though their cause may be good, yet are dangerous from their rash & impracticable notions".

In 1792, Amabel wrote An Historical Sketch of the French Revolution from its Commencement to the Year 1792 and had it anonymously published by John Debrett. In 1796, she wrote An Historical Essay on the Ambition and Conquests of France, with some remarks on the French Revolution, published in 1797, also anonymously. Debrett also accepted a pamphlet she described as "an appeal to the People of Britain", and "desired that the unknown author would send any other work to him". No other crisis provoked her to write until the assassination of Spencer Perceval in 1812, when she discussed the possibility of a pamphlet directly with John Hatchard. She died on 4 March 1833 at Sain James's Square, aged 81, and was buried at the de Grey Mausoleum in Flitton, Bedfordshire. She was succeeded in her titles and estates by her nephew Thomas Philip Weddell.

Reynolds therefore suppressed psychological individuality to gain grandeur appropriate for these aristocrats. Lady Betty graciously deigns to accept our presence. As heir to his father's estate, John commandingly surveys the distance, and Isabella Elizabeth displays a coy shyness. Even the Skye terrier gazes upward with proper loyalty.

The figure group forms a pyramidal silhouette, and the beech trees accentuate a spatial wedge that recedes toward two vistas on the picture's sides. This stable, triangular configuration is reminiscent of Holy Families, sheltered beneath canopies, painted by Raphael and Poussin. The earthy color scheme of ochers and umbers recalls the sonorous tones employed by Titian and Rembrandt. Reynolds' ability to synthesize from so many sources astounded Thomas Gainsborough, who reportedly exclaimed, "Damn him, how various he is!"

From this time, she lived in a menage a trois with Georgiana and her husband, William, the 5th Duke of Devonshire, for about twenty-five years. She bore two children by the Duke: a son, Augustus (later Augustus Clifford, 1st Baronet), and a daughter, Caroline St. Jules, who were raised at Devonshire House with the Duke's legitimate children by Georgiana. Lady Elizabeth finally married the Duke in 1809, three years after the death of his first wife, during which time she had continued to live in his household.

Bess is also said to have had affairs with several other men, including Ercole Cardinal Consalvi, John Sackville, 3rd Duke of Dorset, Count Axel von Fersen, Charles Lennox, 3rd Duke of Richmond, and Valentine Richard Quin, 1st Earl of Dunraven. There is some evidence that Quin fathered an illegitimate son by her, who became the noted physician, Frederick Hervey Foster Quin.

Bess also had literary pretensions, and was a friend of the French author Madame de Stael, with whom she corresponded from about 1804.

e\

.jpg)

Reynolds creates a perfect setting for this small boy, who looks beyond the frame at something in the distance that no one else can perceive. His white skin, his bright eyes, and his dynamic pose contrast with the somber colors of the background. In creating such a setting, Reynolds wished to demonstrate the primacy of a child's world that cares little for external matters. The subtle echoes between the child's blond hair, the bronze reflections on the tree behind him, and the material that forms the child's belt enliven the picture, thereby emphasizing the child's sweetness.

What makes this painting more interesting today is the manner in which it has aged. When painted, Miss Ingram would have had a healthy complexion. The use of unstable pink pigments has resulted in her current pale state. This gives the portrait a much more arresting quality than perhaps it had when it was new.

TELL me, ye prim adepts in Scandal's school,

Who rail by precept, and detract by rule,

Lives there no character, so tried, so known,

So decked with grace, and so unlike your own,

That even you assist her fame to raise, (5)

Approve by envy, and by silence praise!

Attend!-a model shall attract your view-

Daughters of calumny, I summon you!

You shall decide if this a portrait prove,

Or fond creation of the Muse and Love. (10)

Attend, ye virgin critics, shrewd and sage,

Ye matron censors of this childish age,

Whose peering eye and wrinkled front declare

A fixed antipathy to young and fair;

By cunning, cautious; or by nature, cold, (15)

In maiden madness, virulently bold!-

Attend, ye skilled to coin the precious tale,

Creating proof, where innuendos fail!

Whose practised memories, cruelly exact,

Omit no circumstance, except the fact!- (20)

Attend, all ye who boast,-or old or young,-

The living libel of a slanderous tongue!

So shall my theme as far contrasted be,

As saints by fiends, or hymns by calumny.

Come, gentle Amoret (for 'neath that name (25)

In worthier verse is sung thy beauty's fame);

Come-for but thee who seeks the Muse? and while

Celestial blushes check thy conscious smile,

With timid grace, and hesitating eye,

The perfect model, which I boast, supply:- (30)

Vain Muse! couldst thou the humblest sketch create

Of her, or slightest charm couldst imitate-

Could thy blest strain in kindred colours trace

The faintest wonder of her form and face-

Poets would study the immortal line, (35)

And Reynolds own his art subdued by thine;

That art, which well might added lustre give

To Nature's best, and Heaven's superlative:

On Granby's cheek might bid new glories rise,

Or point a purer beam from Devon's eyes! (40)

Hard is the task to shape that beauty's praise,

Whose judgment scorns the homage flattery pays!

But praising Amoret we cannot err,

No tongue o'ervalues Heaven, or flatters her!

Yet she by Fate's perverseness-she alone (45)

Would doubt our truth, nor deem such praise her own.

Adorning fashion, unadorned by dress,

Simple from taste, and not from carelessness;

Discreet in gesture, in deportment mild,

Not stiff with prudence, nor uncouthly wild: (50)

No state has Amoret; no studied mien;

She frowns no goddess, and she moves no queen.

The softer charm that in her manner lies

Is framed to captivate, yet not surprise;

It justly suits the expression of her face,- (55)

'Tis less than dignity, and more than grace!

On her pure cheek the native hue is such,

That, formed by Heaven to be admired so much,

The hand divine, with a less partial care,

Might well have fixed a fainter crimson there, (60)

And bade the gentle inmate of her breast-

Inshrinèd Modesty-supply the rest.

But who the peril of her lips shall paint?

Strip them of smiles-still, still all words are faint.

But moving Love himself appears to teach (65)

Their action, though denied to rule her speech;

And thou who seest her speak, and dost not hear,

Mourn not her distant accents 'scape thine ear;

Viewing those lips, thou still may'st make pretence

To judge of what she says, and swear 'tis sense: (70)

Clothed with such grace, with such expression fraught,

They move in meaning, and they pause in thought!

But dost thou farther watch, with charmed surprise,

The mild irresolution of her eyes,

Curious to mark how frequent they repose, (75)

In brief eclipse and momentary close-

Ah! seest thou not an ambushed Cupid there,

Too timorous of his charge, with jealous care

Veils and unveils those beams of heavenly light,

Too full, too fatal else, for mortal sight? (80)

Nor yet, such pleasing vengeance fond to meet,

In pardoning dimples hope a safe retreat.

What though her peaceful breast should ne'er allow

Subduing frowns to arm her altered brow,

By Love, I swear, and by his gentle wiles, (85)

More fatal still the mercy of her smiles!

Thus lovely, thus adorned, possessing all

Of bright or fair that can to woman fall,

The height of vanity might well be thought

Prerogative in her, and Nature's fault. (90)

Yet gentle Amoret, in mind supreme

As well as charms, rejects the vainer theme;

And, half mistrustful of her beauty's store,

She barbs with wit those darts too keen before:-

Read in all knowledge that her sex should reach, (95)

Though, Greville, or the Muse, should deign to teach,

Fond to improve, nor timorous to discern

How far it is a woman's grace to learn;

In Millar's dialect she would not prove

Apollo's priestess, but Apollo's love, (100)

Graced by those signs which truth delights to own,

The timid blush, and mild submitted tone:

Whate'er she says, though sense appear throughout,

Displays the tender hue of female doubt;

Decked with that charm, how lovely wit appears, (105)

How graceful science, when that robe she wears!

Such too her talents, and her bent of mind,

As speak a sprightly heart by thought refined:

A taste for mirth, by contemplation schooled,

A turn for ridicule, by candour ruled, (110)

A scorn of folly, which she tries to hide;

An awe of talent, which she owns with pride!

Peace, idle Muse! no more thy strain prolong,

But yield a theme, thy warmest praises wrong;

Just to her merit, though thou canst not raise (115)

Thy feeble verse, behold th' acknowledged praise

Has spread conviction through the envious train,

And cast a fatal gloom o'er Scandal's reign!

And lo! each pallid hag, with blistered tongue,

Mutters assent to all thy zeal has sung- (120)

Owns all the colours just-the outline true;

Thee my inspirer, and my model-CREWE!

_1776.jpg)

.jpg)

The second son of Lord Augustus Fitzroy and a grandson of the 2nd Duke of Grafton, Fitzroy joined the 1st Regiment of Foot Guards as an ensign in 1752. He fought at the Battles of Minden and Kirchdenkern during the Seven Years' War and rose to the ranks of Captain in 1756 and Lieutenant-Colonel in 1758.

On 27 July 1758, Fitzroy married Anne Warren, the daughter and co-heir of Admiral Sir Peter Warren and they later had seven children. He was a Groom of the Bedchamber from 1760-62 and Whig MP (later Tory from 1770-83 and thereafter a Whig again) for Oxford from 1759-61, for Bury St Edmunds from 1761-74 and for Thetford from 1774-80. On leaving the post of Queen Charlotte's Vice-Chamberlain in 1780 (a post he had held since 1768), he was created Baron Southampton on 17 October that year and was succeeded by his eldest son, George, upon his death in 1797.

His younger son, Sir Charles Fitzroy, was romantically linked to King George III's daughter Princess Amelia.

Townshend was the second son of Field Marshal George Townshend, 1st Marquess Townshend, by his first wife Charlotte Compton, 15th Baroness Ferrers of Chartley. George Townshend, 2nd Marquess Townshend, was his elder brother and Charles Townshend his uncle. He was elected to the House of Commons for Cambridge University in 1780, a seat he held until 1784, and later represented Westminster from 1788 to 1790 and Knaresborough from 1793 to 1818. In 1806 he was admitted to the Privy Council.

Townshend married Georgiana Anne, daughter of William Poyntz. Their elder son Charles Fox Townshend was the founder of the Eton Society but died young. Their younger son John became an Admiral in the Royal Navy and succeeded his first cousin in the marquessate in 1855. Townshend died in February 1833, aged 76. Lady Georgiana Anne died in 1851.

Her pose recalls the figure of prophet Isaiah from Michelangelo's Sistine Ceiling, but Mrs Siddons insisted she had composed it spontaneously herself. This is one of three versions Reynolds made of the portrait.

Ostenaco wears around his neck a silver gorget, a military mark of rank given by the British to Native Americans they regarded as allies. He also wears a medal the British had awarded him after a recent peace treaty.

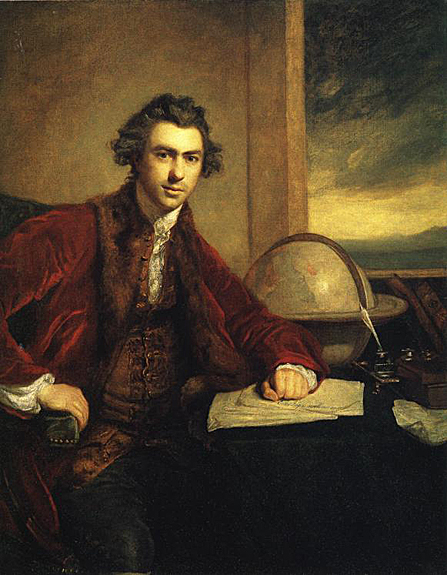

At the same time it is a manifesto of the young artist's aims and ambitions. Reynolds is casting himself in the role of a man of vision, who uses the art of the past in order to look to the future.

Reynolds is traditionally supposed to have become partially deaf due to a cold caught in the Vatican during his stay in Rome in the early 1750's. But deafness was also hereditary in his family.

Reynolds wears his doctoral cap and robes, and holds a scroll referring to his Discourses on Art. The bust of his artistic hero, Michelangelo, seems to nod in deference towards him.

He served as president of the Royal Society for forty-two years. He also founded the Royal Institution of Great Britain with Rumford in 1799, naming Sir Humphry Davy as the first lecturer.

The court case centered round Lady Worsley, the wife of Sir Richard Worsley, the Governor of the Isle of Wight. She had spent the night in a hotel with George Maurice Bisset, a captain in the Isle of Wight militia. But his defense had claimed that Worsley had encouraged this liaison and was a willing accomplice! Lady Worsley was an attractive woman, who had a reputation for flirtatious behavior and was known in fashionable society as somewhat loose with her affections.

Worsley's political career was badly damaged by the very public collapse of his marriage. On 20 September 1775 he had married Seymour Dorothy, the younger daughter and coheir of Sir John Fleming, first baronet (d. 1763), of Brompton Park, Middlesex, and his wife, Lady (Jane) Fleming (d. 1811), and had with her a son, Robert Edwin (who died young), and a daughter. Though the marriage brought Worsley over £70,000, the couple soon fell out. Lady Worsley's numerous affairs (twenty-seven lovers were rumored) became notorious. On 22 February 1782 Worsley brought an action for criminal conversation with his wife against George M. Bissett, an officer in the Hampshire militia and a neighbor on the island. The jury found for the plaintiff but, on the ground of Worsley's connivance, awarded him only 1s. damages, not the £20,000 claimed. He subsequently entered into articles of separation with his wife in 1788.

Details of Emma's early life are unclear, but at age 12 she was known to be working as a maid at the Hawarden home of Doctor Honoratus Leigh Thomas, a surgeon working in Chester. Although this employment provided an escape from abject poverty, she was sacked after just a few months, presumably for poor work. She headed for London. There she worked for the Budd family in Chatham Place, Blackfriars. There she met a maid called Jane Powell, who wanted to be an actress. Emma joined in with Jane's rehearsals for various tragic roles - Jane is known to have played parts in local theatres. Emma and Jane enjoyed city life, but their excursions into London's unsavory nightlife, and particularly their likely liaisons with young men, soon led Mrs Budd to sack the pair.

Emma went back to her mother, who was at this time living in comparative squalor near Oxford Street. Inspired by Jane's enthusiasm for the theatre, Emma started work at the Drury Lane theater in Covent Garden, as maid to various actresses, among them Mary Robinson (poet). However, this paid little, and she supplemented her income by working Drury Lane as a prostitute. She soon gained employment in a local tavern/brothel. It was here that she became a strip tease artiste, a performance that involved striking lewd poses for the viewers. This act she would later refine by removing the nudity and lewdness, and developing it into what would become her Attitudes.

At about this time, Emma also began to pose for the artists George Romney and Sir Joshua Reynolds. Many hundreds of works were painted of Emma, particularly by Romney. The Royal Academy had great difficulty in finding models, as the work was considered unbecoming. Emma therefore undertook such work under various pseudonyms, such as "Emma Potts", "Emily Potts", "Miss Emily", "Warren", "Bertie" and "Coventry". One of the most famous of these is "Thais", by Sir Joshua Reynolds, which hangs in the drawing room at Waddesdon Manor, in Buckinghamshire, England. It shows Emma as Thais, mistress of Alexander the Great, holding aloft a flaming torch and encouraging Alexander to burn down the Temple of Persepolis.

Thais was a famous Greek hetaera who lived during the time of Alexander the Great and accompanied him on his campaigns.

Thals first came to the attention of history when, in 330 BC, Alexander the Great burned down the palace of Persepolis after a drinking party. Thais was present at the party and gave a speech which convinced Alexander to burn the palace. Cleitarchus claims that the destruction was a whim; Plutarch and Diodorus recount that it was intended as retribution for Xerxes' burning of the temple of Athena on the Acropolis in Athens in 480 BC (the destroyed temple was replaced by the Parthenon of Athens).

"When the king (Alexander) had caught fire at their words, all leaped up from their couches and passed the word along to form a victory procession in honor of Dionysus. Promptly many torches were gathered. Female musicians were present at the banquet, so the king led them all out for the comus to the sound of voices and flutes and pipes, Thais the courtesan leading the whole performance. She was the first, after the king, to hurl her blazing torch into the palace. As the others all did the same, immediately the entire palace area was consumed, so great was the conflagration. It was remarkable that the impious act of Xerxes, king of the Persians, against the acropolis at Athens should have been repaid in kind after many years by one woman, a citizen of the land which had suffered it, and in sport."

~Diodorus of Sicily (XVII.72)

It became fashionable in the later eighteenth century for young aristocrats to identify with the romantic, virile figure of the archer. Reynolds conjures up an older, more chivalrous era; the pile of game emphasizes that they are not common 'foresters' but noblemen exploiting their aristocratic right to hunt.

Then the Lord said to Samuel, "See, I am about to do something in Israel that will make both ears of anyone who hears of it tingle. On that day I will fulfill against Eli all that I have spoken concerning his house, from beginning to end. For I have told him that I am about to punish his house forever, for the iniquity that he knew, because his sons were blaspheming God, and he did not restrain them. Therefore I swear to the house of Eli that the iniquity of Eli's house shall not be expiated by sacrifice or offering forever." Samuel lay there until morning; then he opened the doors of the house of the Lord. Samuel was afraid to tell the vision to Eli. But Eli called Samuel and said, "Samuel, my son." He said, "Here I am." Eli said, "What was it that he told you? Do not hide it from me. May God do so to you and more also, if you hide anything from me of all that he told you." So Samuel told him everything and hid nothing from him. Then he said, "It is the Lord; let him do what seems good to him."

As Samuel grew up, the Lord was with him and let none of his words fall to the ground. And all Israel from Dan to Beer-sheba knew that Samuel was a trustworthy prophet of the Lord.

Had the false Trojan never touch'd my shore!"

Then kiss'd the couch; and, "Must I die," she said,

"And unreveng'd? 'T is doubly to be dead!

Yet ev'n this death with pleasure I receive:

On any terms, 't is better than to live.

These flames, from far, may the false Trojan view;

These boding omens his base flight pursue!"

She said, and struck; deep enter'd in her side

The piercing steel, with reeking purple dyed:

Clogg'd in the wound the cruel weapon stands;

The spouting blood came streaming on her hands.

Her sad attendants saw the deadly stroke,

And with loud cries the sounding palace shook.

Distracted, from the fatal sight they fled,

And thro' the town the dismal rumor spread.

First from the frighted court the yell began;

Redoubled, thence from house to house it ran:

The groans of men, with shrieks, laments, and cries

Of mixing women, mount the vaulted skies.

Not less the clamor, than if- ancient Tyre,

Or the new Carthage, set by foes on fire-

The rolling ruin, with their lov'd abodes,

Involv'd the blazing temples of their gods.

Her sister hears; and, furious with despair,

She beats her breast, and rends her yellow hair,

And, calling on Eliza's name aloud,

Runs breathless to the place, and breaks the crowd.

"Was all that pomp of woe for this prepar'd;

These fires, this fun'ral pile, these altars rear'd?

Was all this train of plots contriv'd," said she,

"All only to deceive unhappy me?

Which is the worst? Didst thou in death pretend

To scorn thy sister, or delude thy friend?

Thy summon'd sister, and thy friend, had come;

One sword had serv'd us both, one common tomb:

Was I to raise the pile, the pow'rs invoke,

Not to be present at the fatal stroke?

At once thou hast destroy'd thyself and me

,

Thy town, thy senate, and thy colony!

Bring water; bathe the wound; while I in death

Lay close my lips to hers, and catch the flying breath."

This said, she mounts the pile with eager haste,

And in her arms the gasping queen embrac'd;

Her temples chaf'd; and her own garments tore,

To stanch the streaming blood, and cleanse the gore.

Thrice Dido tried to raise her drooping head,

And, fainting thrice, fell grov'ling on the bed;

Thrice op'd her heavy eyes, and sought the light,

But, having found it, sicken'd at the sight,

And clos'd her lids at last in endless night.

Then Juno, grieving that she should sustain

A death so ling'ring, and so full of pain,

Sent Iris down, to free her from the strife

Of lab'ring nature, and dissolve her life.

For since she died, not doom'd by Heav'n's decree,

Or her own crime, but human casualty,

And rage of love, that plung'd her in despair,

The Sisters had not cut the topmost hair,

Which Proserpine and they can only know;

Nor made her sacred to the shades below.

Downward the various goddess took her flight,

And drew a thousand colors from the light;

Then stood above the dying lover's head,

And said: "I thus devote thee to the dead.

This off'ring to th' infernal gods I bear."

Thus while she spoke, she cut the fatal hair:

The struggling soul was loos'd, and life dissolv'd in air.

The sisters, all of whom were to marry in the following years, were single when the painting was commissioned. Their portrait, exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1781, would have advertised their eligibility and desirability. Individually and collectively, the Waldegrave sisters embody contemporary ideals of feminine accomplishment, style, and beauty.

After inheriting the dukedom, Marlborough took his seat in the House of Lords in 1760, becoming Lord Lieutenant of Oxfordshire in that same year. The following year, he bore the scepter with the cross at the coronation of George III. In 1762, he was made Lord Chamberlain as well as a Privy Counselor, and after a year succeeded this appointment as Lord Privy Seal. An amateur astronomer, he built a private observatory at his residence, Blenheim Palace. He kept up a lively scientific correspondence with Hans Count von Bruhl, another aristocratic dilettante in astronomy.

The Duke was made a Knight of the Garter in 1768, and was elected to the Royal Society in 1786. He married Lady Caroline Russell, daughter of John Russell, 4th Duke of Bedford, in 1762, by whom he had seven children:

Lady Caroline Spencer (1763-1813), married the 2nd Viscount Clifden and had issue, incl. George Agar-Ellis, 1st Baron Dover.

Lady Elizabeth Spencer (d. 1812), married her cousin John Spencer (a grandson of the 3rd Duke of Marlborough) and had issue.

Lady Charlotte Spencer (d. 1802), married Rev. Edward Nares and had issue. George Spencer, Marquess of Blandford (1766-1840)

Lord Henry John Spencer (1770-1795)

Lady Anne Spencer (1773-1865), married the future 6th Earl of Shaftesbury and had issue.

Lady Amelia Sophia Spencer (d. 1829), married Henry Pytches Boyce.

Lord Francis Almeric Spencer (1779-1845)

He died at Blenheim Palace aged 78, and was buried there.

Father our pain', they said,

'Will lessen if you eat us you are the one

Who clothed us with this wretched flesh: we plead

For you to be the one who strips it away'

Without his dart, Cupid is a sad, emasculated little figure; but the tone of the painting as a whole is light-hearted and witty. It is a new take on one of the most familiar mythological subjects in western art. There had been many images of Venus scolding Cupid and clipping his wings, or Eros having a tussle with his brother Anteros. The idea that Cupid's crime is an interest in money, however, is Reynolds's own. Reynolds may have been having a sly dig at the loveless lives of people who married for money, a common practice in the circles of high-spending young men who were the picture's anticipated audience. And it is possible he may even have been having a little fun at his own expense. The figures on Cupid's account sheet appear to be the prices Reynolds charged for various sizes of painting and frame. Could he be commenting upon his own status as a confirmed old bachelor whom love has passed by, as a result of his too-eager pursuit of professional success and with it, financial security?

Reynolds painted Venus subjects on numerous occasions. Indeed, this canvas is a later version of a painting he originally exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1771, now in the collection of English Heritage at Kenwood House, Hampstead. The earlier painting was smaller and square in format. This may suggest that it was intended as part of a decorative scheme. The whole effect is lighter and brighter, with Venus's swirling drapery more prominent and the figures have a rather cramped feel. In the Lady Lever painting, there is more attention to contrasts of light and shade, more space around the figures, and a more pleasing treatment of Venus's right arm. One simple explanation might be that in making the second picture, Reynolds felt he could improve on the first one, making the subject more convincing and 'Old Master'-like. His handling of paint in this work is especially rich and textural.

Reynolds was obviously conscious of the dangers of his mythological pictures appearing to patrons and critics as dry exercises in theory. In order to make them marketable, he often chose subjects that, as here, had distinctly erotic overtones. Painting Venus was an accepted way for artists to portray the female nude, as generations of connoisseurs had long understood. Reynolds was appealing to this awareness even as he took care to treat the subject with humor and intellectual sophistication. Given that the depiction of Venus had been uncommon within traditional British art, it could be said that in works like this Reynolds was first and foremost persuading British patrons that they had now grown up to the level of their continental counterparts.

He was born in Leicester House, Leicester Fields (now Leicester Square), London, where his parents had moved after his grandfather, George I, was invited to take the British throne. His godparents included The King and The Queen in Prussia (his paternal aunt), but they apparently didn't appear, probably represented by proxies. On 27 July 1726, at only four-years-old, he was created Duke of Cumberland, Marquess of Berkhamstead in the County of Hertford, Earl of Kennington in the County of Surrey, Viscount of Trematon in the County of Cornwall, and Baron of the Isle of Alderney. The young prince was educated well (his tutor was his mother's favorite Andrew Fountaine), becoming his parents' favorite (so much so that his father would later consider ways of making him his heir in preference over his eldest brother, Frederick, Prince of Wales). At Hampton Court Palace, apartments were designed especially for him by William Kent.

From childhood, he showed physical courage and ability. He was intended, by the King and Queen, for the office of Lord High Admiral, and, in 1740, he sailed, as a volunteer, in the fleet under the command of Sir John Norris, but he quickly became dissatisfied with the Navy and, early in 1742, he began an Army career. In December 1742, he became a Major-General, and, the following year, he first saw active service in Persia. George II and the "martial boy" shared in the glory of the Battle of Dettingen (27 June 1743), and Cumberland, who was wounded in the action, was reported as a hero in Britain, thus founding his military popularity. After the battle he was made Lieutenant-General.

During the ten years of peace from 1748, Cumberland occupied himself chiefly with his duties as Captain-General, and the result of his work was clearly shown in the conduct of the army in the Seven Years' War. His unpopularity, which had steadily increased since Culloden, interfered greatly with his success in politics, and when the death of the Prince of Wales brought the latter's son, a minor, next in succession to the throne, the Duke was not able to secure for himself the contingent regency, which was vested in the Dowager Princess of Wales, who considered him an enemy.

In 1757, the Seven Years' War having broken out, Cumberland was placed at the head of a motley army of allies led by Great Britain to defend Hanover. At the Battle of Hastenbeck, near Hamelin, on 26 July 1757, he was defeated by the superior forces of d'Estrees. In September of the same year, his defeat had almost become disgrace. Driven from point to point, and at last hemmed in by the French, under Richelieu, he capitulated at Zeven monastery, on 8 September 1757, agreeing to evacuate Hanover. He played a major role as second-in-command to Duke Ferdinand of Brunswick later in the war.

His disgrace was completed on his return to England by the refusal of his father, George II, to be bound by the terms of the Duke's agreement. In chagrin and disappointment, he retired into private life, having formally resigned the public offices he held. In his retirement, he made no attempt to justify his conduct, applying in his own case the discipline he had enforced in others. For a few years, he lived quietly at Cumberland Lodge in Windsor and subsequently in London, taking but little part in politics. He did much, however, to displace the Bute ministry and that of Grenville, and endeavored to restore Pitt to office. Public opinion had now set in his favor, and he became almost as popular as he had been in his youth. After the accession of his nephew, George III, he vied with his sister-in-law, the Dowager Princess of Wales, for the role of regent in times of emergency. Shortly before his death, the Duke was requested to open negotiations with Pitt for a return to power. This was, however, unsuccessful.

The Duke passed away suddenly on Upper Grosvenor Street in London, on October 31, 1765 apparently from a myocardial infarction brought on by his life-long obesity, at the age of 44. He is currently buried beneath the floor of the nave of the Henry VII Lady Chapel in Westminster Abbey.

Source: Art Renewal Center

Source: Web Gallery of Art

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.