1840 - 1926

Monet was born on November 14, 1840 on the fifth floor of 45 rue Laffitte, in the ninth arrondissement of Paris. He was the second son of Claude-Adolphe and Louise-Justine Aubrée Monet, both of them second-generation Parisians. On May 20, 1841, he was baptized in the local parish church, Notre-Dame-de-Lorette as Oscar-Claude. In 1845, his family moved to Le Havre in Normandy. His father wanted him to go into the family grocery store business, but Claude Monet wanted to become an artist. His mother was a singer.

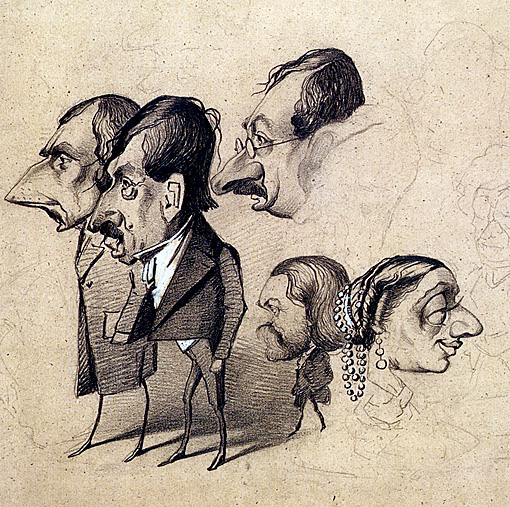

On the first of April 1851, Monet entered the Le Havre secondary school of the arts. He first became known locally for his charcoal caricatures, which he would sell for ten to twenty francs. Monet also undertook his first drawing lessons from Jacques-François Ochard, a former student of Jacques-Louis David. On the beaches of Normandy in about 1856/1857 he met fellow artist Eugène Boudin who became his mentor and taught him to use oil paints. Boudin taught Monet "en plein air" (outdoor) techniques for painting.

On 28 January 1857 his mother died. He was 16 years old when he left school, and went to live with his widowed childless aunt, Marie-Jeanne Lecadre.

When Monet traveled to Paris to visit The Louvre, he witnessed painters copying from the old masters. Monet, having brought his paints and other tools with him, would instead go and sit by a window and paint what he saw. Monet was in Paris for several years and met several painters who would become friends and fellow impressionists. One of those friends was Édouard Manet.

In June of 1861 Monet joined the First Regiment of African Light Cavalry in Algeria for two years of a seven-year commitment, but upon his contracting typhoid his aunt Marie-Jeanne Lecadre intervened to get him out of the army if he agreed to complete an art course at a university. It is possible that the Dutch painter Johan Barthold Jongkind, whom Monet knew, may have prompted his aunt on this matter. Disillusioned with the traditional art taught at universities, in 1862 Monet became a student of Charles Gleyre in Paris, where he met Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Frédéric Bazille, and Alfred Sisley. Together they shared new approaches to art, painting the effects of light en plein air with broken color and rapid brushstrokes, in what later came to be known as Impressionism.

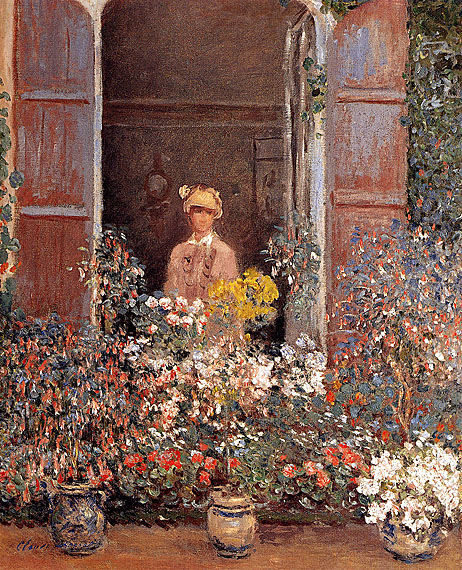

Monet's Camille or The Woman in the Green Dress (La Femme à la Robe Verte), painted in 1866, brought him recognition, and was one of many works featuring his future wife, Camille Doncieux; she was the model for the figures in The Women in the Garden of the following year, as well as for On the Bank of the Seine, Bennecourt, 1868, pictured here. Shortly thereafter Doncieux became pregnant and bore their first child, Jean. In 1868, due to financial reasons, Monet attempted suicide by throwing himself into the Seine.

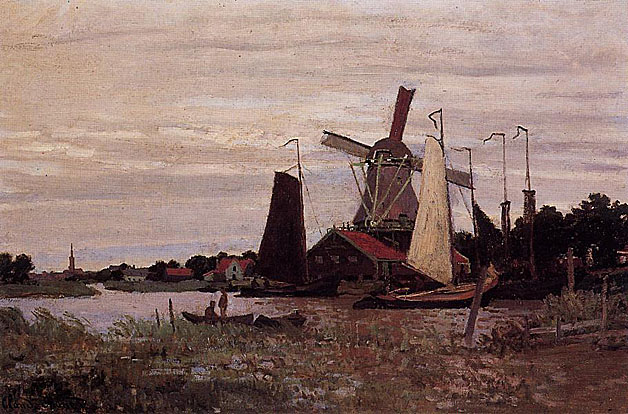

After the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War (July 19, 1870), Monet took refuge in England in September 1870. While there, he studied the works of John Constable and Joseph Mallord William Turner, both of whose landscapes would serve to inspire Monet's innovations in the study of color. In the Spring of 1871, Monet's works were refused to be included in the Royal Academy exhibition. In May 1871 he left London to live in Zaandam, where he made 25 paintings (and the police suspected him of revolutionary activities). He also had a first visit to nearby Amsterdam. In October or November 1871 he returned to France. Monet lived from December 1871 to 1878 at Argenteuil, a village on the Seine near Paris, and here he painted some of his best known works. In 1874, he briefly returned to Holland.

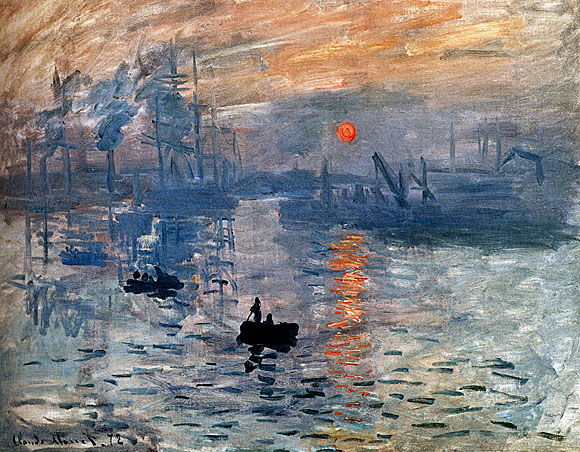

In 1872 (or 1873), he painted Impression, Sunrise (Impression: soleil levant) depicting a Le Havre landscape. It hung in the first Impressionist exhibition in 1874 and is now displayed in the Musée Marmottan-Monet, Paris. From the painting's title, art critic Louis Leroy coined the term "Impressionism", which he intended to be derogatory, however the Impressionists appropriated the term for themselves.

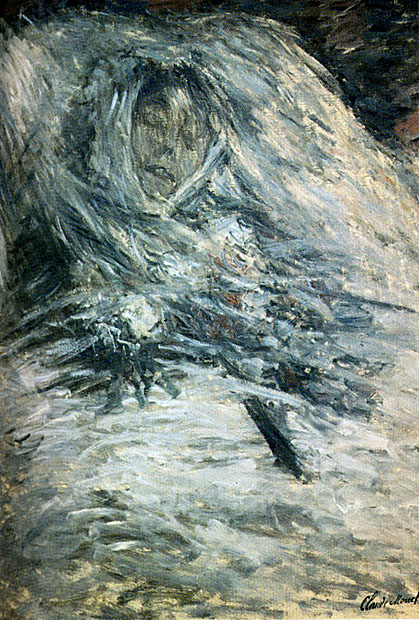

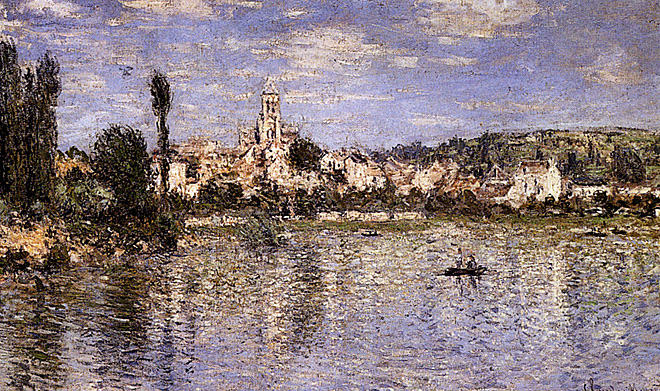

Monet and Camille Doncieux had married just before the war (June 28, 1870) [6] and, after their excursion to London and Zaandam, they had moved into a house in Argenteuil near the Seine River in December 1871. She became ill in 1876. They had a second son, Michel, on March 17, 1878, (Jean was born in 1867). This second child weakened her already fading health. In that same year, he moved to the village of Vétheuil. At the age of thirty-two, Madame Monet died on 5 September 1879 of tuberculosis; Monet painted her on her death bed.

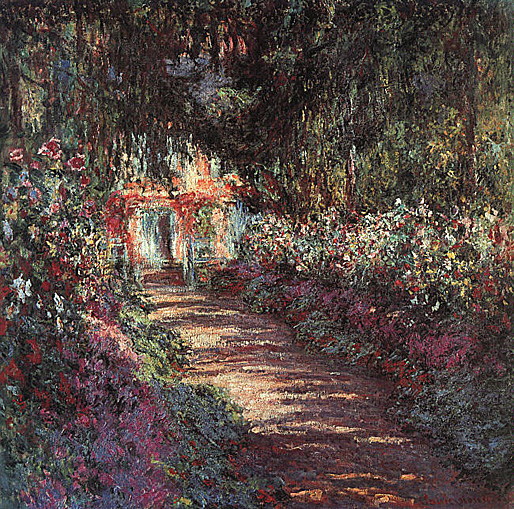

After several difficult months following the death of Camille, a grief stricken Monet (resolving never to be mired in poverty again) began in earnest to create some of his best paintings of the 19th century. During the early 1880's Monet painted several groups of landscapes and seascapes in what he considered to be campaigns to document the French countryside. His extensive campaigns evolved into his series' paintings. Camille Monet became ill with tuberculosis in 1876. Pregnant with her second child she gave birth to Michel Monet in March 1878. In 1878 the Monets temporarily moved into the home of Ernest Hoschedé, (1837-1891), a wealthy department store owner and patron of the arts. Both families then shared a house in Vétheuil during the summer. After her husband was bankrupted, and left in 1878 for Belgium, and after the death of Camille in September 1879 and while Monet continued to live in the house in Vétheuil; Alice Hoschedé helped Monet to raise his two sons, Jean and Michel, by taking them to Paris to live alongside her own six children. They were Blanche, Germaine, Suzanne, Marthe, Jean-Pierre, and Jacques. In the spring of 1880 Alice Hoschedé and all the children left Paris and rejoined Monet still living in the house in Vétheuil. In 1881 all of them moved to Poissy which Monet hated. From the doorway of the little train between Vernon and Gasny he discovered Giverny. In April 1883 they moved to Vernon, then to a house in Giverny, Eure, in Upper Normandy, where he planted a large garden where he painted for much of the rest of his life. Following the death of her estranged husband, Alice Hoschedé married Claude Monet in 1892.

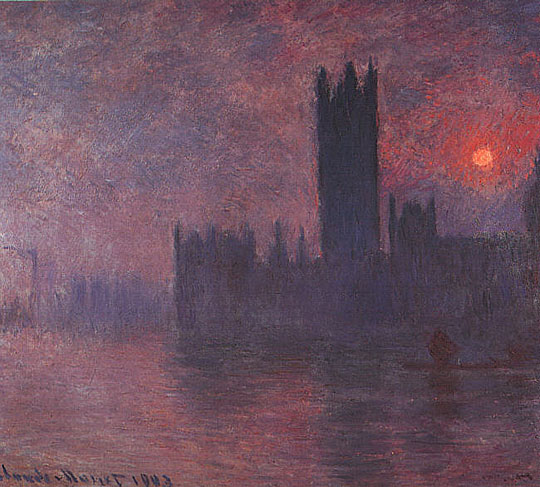

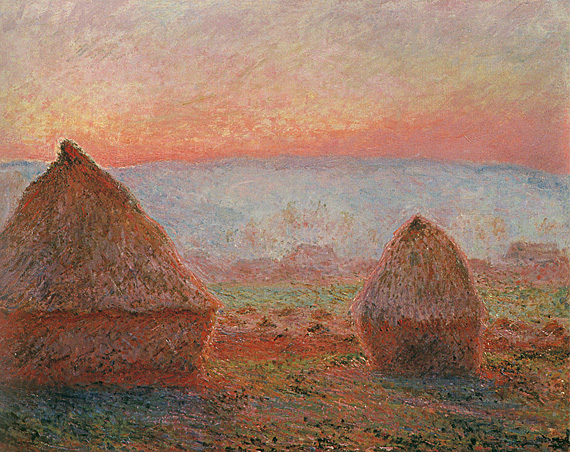

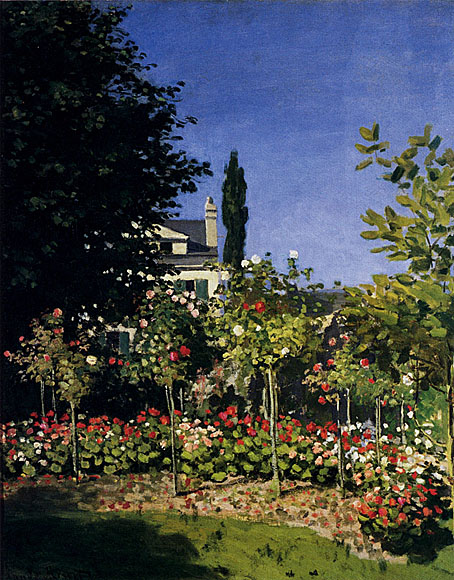

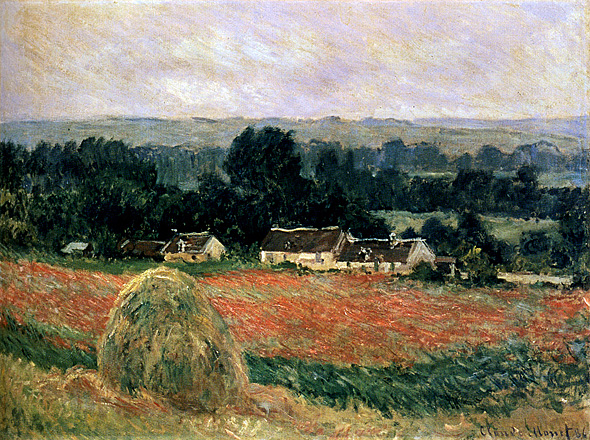

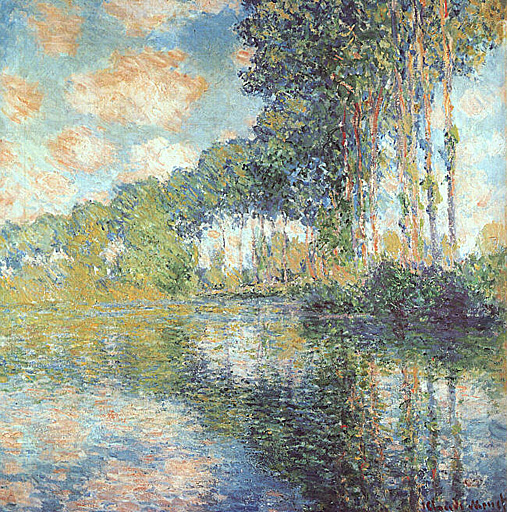

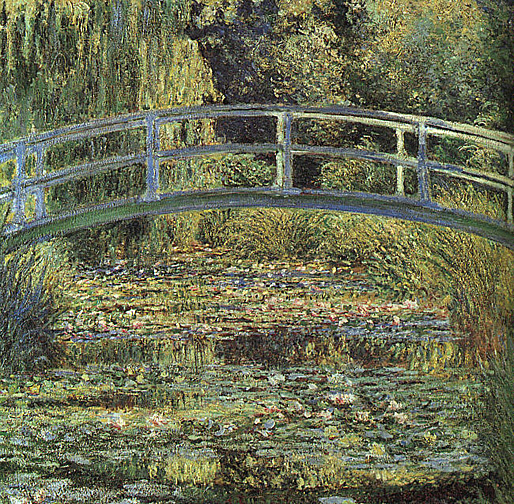

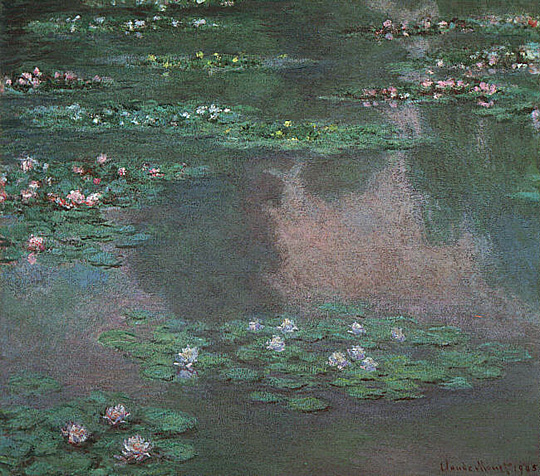

At the beginning of May 1883, Monet and his large family rented a house and two acres from a local landowner. The house was situated near the main road between the towns of Vernon and Gasny at Giverny. There was a barn that doubled as a painting studio, orchards and a small garden. The house was close enough to the local schools for the children to attend and the surrounding landscape offered an endless array of suitable motifs for Monet's work. The family worked and built up the gardens and Monet's fortunes began to change for the better as his dealer Paul Durand-Ruel had increasing success in selling his paintings. By November 1890 Monet was prosperous enough to buy the house, the surrounding buildings and the land for his gardens. Within a few years by 1899 Monet built a greenhouse and a second studio, a spacious building, well lit with skylights. Beginning in the 1880s and 1890s, through the end of his life in 1926, Monet worked on "series" paintings, in which a subject was depicted in varying light and weather conditions. His first series exhibited as such was of Haystacks, painted from different points of view and at different times of the day. Fifteen of the paintings were exhibited at the Durand-Ruel in 1891. He later produced several series' of paintings including: Rouen Cathedral, Poplars, the Houses of Parliament, and Mornings on the Seine and the Water Lilies that were painted on his property at Giverny.

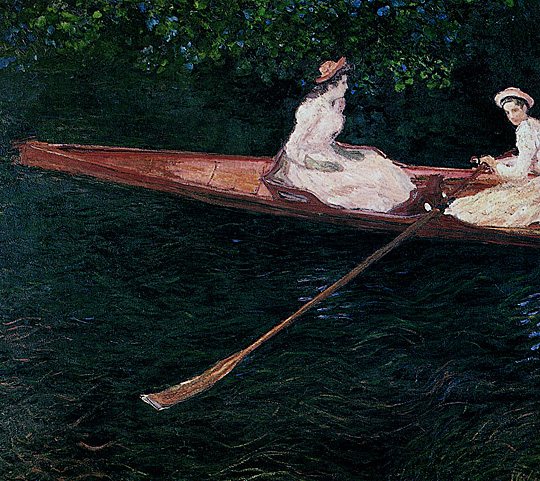

Monet was exceptionally fond of painting controlled nature: his own gardens in Giverny, with its water lilies, pond, and bridge. He also painted up and down the banks of the Seine.

Between 1883 and 1908, Monet traveled to the Mediterranean, where he painted landmarks, landscapes, and seascapes, such as Bordighera. He painted an important series of paintings in Venice, Italy, and in London he painted two important series - views of Parliament and views of Charing Cross Bridge. His second wife Alice died in 1911 and his oldest son Jean, who had married Alice's daughter Blanche, Monet's particular favourite, died in 1914. After his wife died, Blanche looked after and cared for him. It was during this time that Monet began to develop the first signs of cataracts.

During World War I, in which his younger son Michel served and his friend and admirer Clemenceau led the French nation, Monet painted a series of Weeping Willow trees as homage to the French fallen soldiers. Cataracts formed on Monet's eyes, for which he underwent two surgeries in 1923. The paintings done while the cataracts affected his vision have a general reddish tone, which is characteristic of the vision of cataract victims. It may also be that after surgery he was able to see certain ultraviolet wavelengths of light that are normally excluded by the lens of the eye, this may have had an effect on the colors he perceived. After his operations he even repainted some of these paintings, with bluer water lilies than before the operation.

Monet died of lung cancer on December 5, 1926 at the age of 86 and is buried in the Giverny church cemetery. Monet had insisted that the occasion be simple; thus about fifty people attended the ceremony.

His famous home and garden with its water lily pond were bequeathed by his heirs to the French Academy of Fine Arts (part of the Institut de France) in 1966. Through the Fondation Claude Monet, the home and gardens were opened for visit in 1980, following refurbishment. In addition to souvenirs of Monet and other objects of his life, the home contains his collection of Japanese woodcut prints. The home is one of the two main attractions of Giverny, which hosts tourists from all over the world.

The word `Impression' was not so unusual that it had never before been applied to works of art but the scoffing article by Louis Leroy in Le Charivari which coined the word Impressionnist as a general description of the exhibitors added a new term to the critical vocabulary that was to become historic. It was first adopted by the artists themselves for their third group exhibition in 1877, though some disliked the label. It was dropped from two of the subsequent exhibitions as a result of disagreements but otherwise defied suppression.

Claude Monet was a French painter whose 1872 painting, "Impression Sunrise" (which depicted sunlight dancing and shimmering on water), gave the name to the entire Impressionist movement. Monet felt that nature knows no black or white and nature knows no line. These beliefs resulted in this artist creating beautifully colorful and energetic pieces of work. The leading member of the Impressionists, Claude Monet captured the spontaneity of nature's wonderful light.

The foreground here consists of a symmetrical décor: hangings with coloured motifs, green plants, and decorative vases, seen in other paintings by Monet. This composition gives the impression of a curtain opening on to a stage. The viewer's eye is drawn towards the back of the room, towards the illuminated area near the window. In the very centre of the picture, the herringbone pattern of the parquet reinforces the symmetry of the overall view, whilst emphasising the perspective. Then, one after another, one can make out Jean standing slightly to the right, the lamp and the table in the centre, and Camille sitting on the left.

The child's silhouette is reflected on the parquet floor, lit by the daylight from the window. In this interior, "there is a serious attempt to introduce air and light", as the art critic Gustave Geffroy pointed out in 1894.

This silent, intimate scene, an image of everyday family life in Argenteuil, is recreated in a blue-tinted space. This range of colour evokes an atmosphere of tranquillity and poetry, reminiscent of the childhood world of the author Marcel Proust, as he would later describe it in In Search of Lost Time (1913).

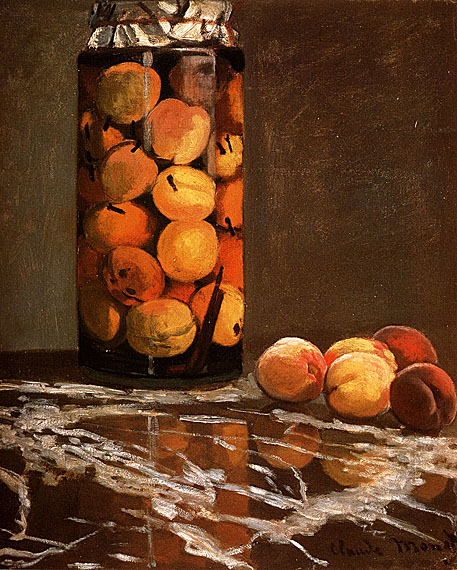

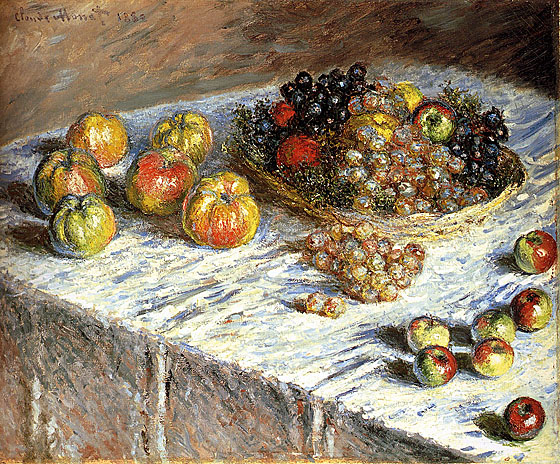

While Monet painted outdoors at every opportunity, he also experimented with more traditional subjects, such as this still life that features objects commonly found in a studio.

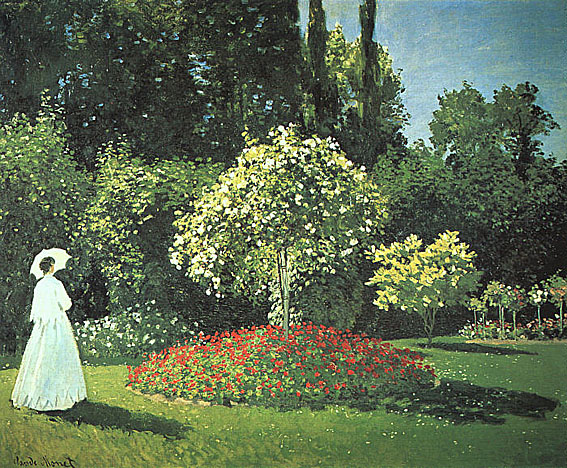

Dressed in the fashion of the day, the figure of a lady was posed by Lecadre's wife. This lonely silhouette introduces an elegaic, sorrowful note into the painting whilst the bright, light area of the dress plays in important role in the balancing the composition and in demonstrating the interrelationship of light and color.

She modelled for her husband on several occasions, including for the painting Camille, "The Woman in the Green Dress".

They were married in 1870. She became ill in 1875. They had two sons; Jean was born in 1867, Michel was born in 1878. This second child weakened her already fading health.

She died of tuberculosis on 5 September, 1879; Monet painted her on her death bed.

These artists were motivated by their determination to break ranks with the standard-bearers of more traditional painting and to break free of the marketing restrictions inherent in the Salon and jury systems. It was only with the death of Pissarro in 1903 that these artists' movement became recognized as the primary nineteenth century artistic revolution, and, over time, lead to what we now view as Modern Art.

Capucines Boulevard provides a similar service to artists, giving them a professional outlet outside of the confines of juried art shows and galleries. It also functions as an intimate collection of galleries where anyone searching for artwork can either participate in a live time auction or purchase art at a set price all from the privacy of their own home.

In May 1891, the artist hung fifteen of the wheat-stack compositions next to one another in a small room in his dealer’s Paris gallery, thus firmly establishing his famous method of working in series. The Art Institute boasts the largest group of Monet’s Stacks of Wheat in the world; five of the six in the collection numbered among the original canvases Monet placed on view in 1891.

Claude Monet

Here, Monet depicted an assortment of two different kinds of apples, together with green and red grapes, and introduced an element of animation, even suspense. This still life is anything but still: the smaller apples at the lower right seem ready to roll off the steeply angled table, and the folds of the cloth appear to ripple like waves. Yet the artist’s control over the objects is evident, giving the composition a sense of stability and vitality. Not only did Monet adopt a magisterial view from above, but he also anchored the fruits and basket with palpable, grayish-green shadows. Exploring the possibilities of materials at hand—one of the central challenges of still-life painting—Monet found several ways to use the same dabs of white pigment: on the grapes, they represent translucent fragility; on the large apples, matte solidity; and on the little apples, glossy sheen.

Still life never became central to Monet’s repertory, but it is tempting to look from this brief experiment to those of his colleagues—most notably Paul Cézanne, who would bring the genre to new heights of complexity and beauty.

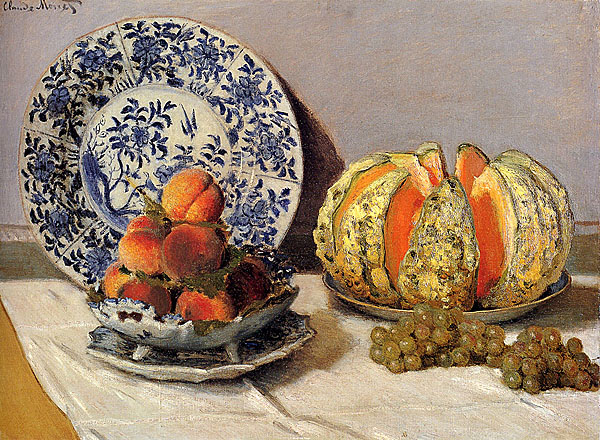

An ordered sequence of spherical forms provides a superb structure: the summer fruits create a subtle chromatic dialogue with the Chinese porcelain that is carefully positioned in the space, allowing the whole to be seen as a coherent artistic discourse. The open-air aesthetic that the Impressionists held so dear fills the canvas with light and lends it a unique originality. However, it is through his use of the colour that Monet best manages to express a situation that is essentially meant to be understood using one’s senses.

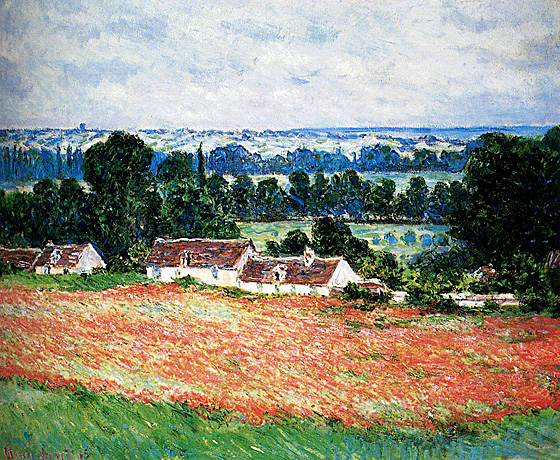

. "Poppies at Argenteuil" was exhibited with "Impression, sunrise" at the 1874 exhibition of the photographer Nadar.

It is one of Claude MONET's most famous paintings, perhaps because Camille seems to swim in flowers.

Claude Monet to Durand-Ruel, 1890

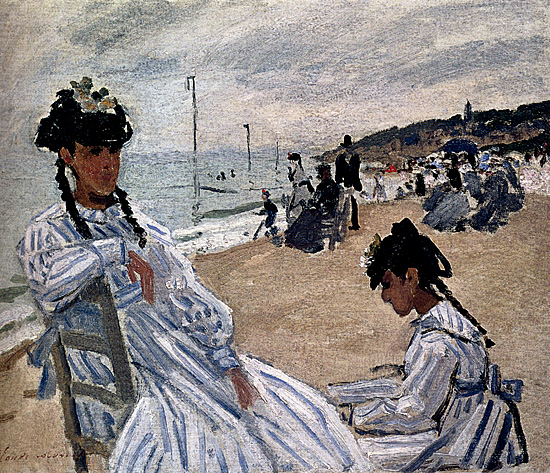

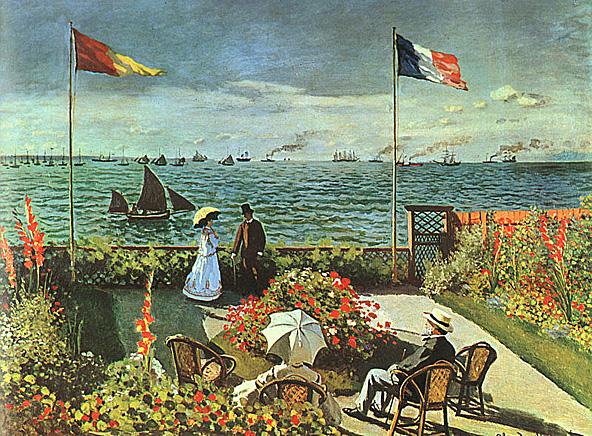

Monet married Camille Doncieux, his mistress since about 1865, in June 1870. They had previously suffered through Monet's conflict with his father, a wholesale grocer, who refused help when Camille became pregnant in 1867. The summer of this seaside idyll was the summer the Franco-Prussian War began. In the autumn of 1870, Monet, with Camille and their son Jean, fled to London to evade conscription.

Claude Monet

Claude Monet

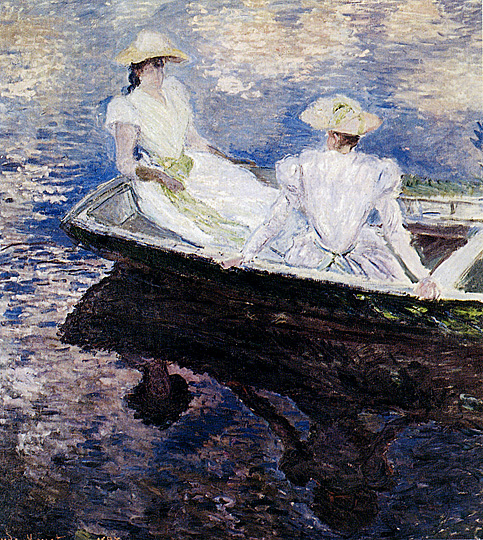

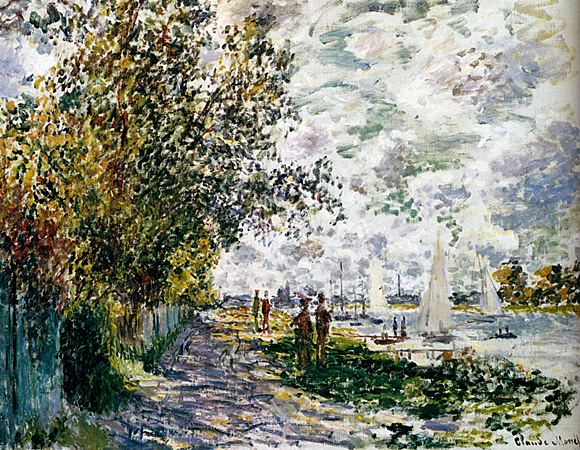

Two years before the Impressionist movement officially came into existence, Monet painted this scene which has all its features, in particular the famous fragmented brushstroke. Regattas at Argenteuil was painted in natural light, because tin tubes and portable easels allowed artists to leave their studios and paint outside. Monet sought to capture the fluidity of air and water and the way they changed with the light. He explained what he was trying to do: "I want to do something intangible. It's appalling, this light that drifts off and takes the colour with it".

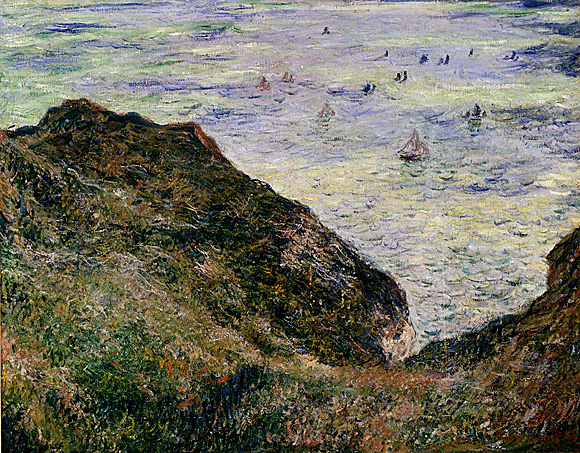

In letters to friends, he wrote of the stormy weather he experienced that winter and he was disappointed that it forced him to abandon Le Havre for Etretat. This was a popular fishing village, and an area he felt too often painted by other artists for him to create 'new' works. It is perhaps testament to Monet's genius that the Etretat paintings are certainly not hackneyed or stale, as his unique perception and vigorous style translated into a fresh interpretation of the area.

In this instance, the monumental cliffs are battered by the crashing waves which are dwarfing two figures in the foreground. They are blurred by the sea spray, and by appearing as little more than silhouettes make it easy for the viewer to identify with them and feel part of the scene.

"Sunflowers" appear in four views Monet painted in 1881 at Vétheuil of the steps to his garden, from which this bouquet was probably cut.

. Monet did not exhibit this work publicly for almost ten years after he completed it. Because of its small, informal composition, seemingly unfinished character, and straightforward depiction of everyday life, this painting and others like it were frequently rejected from the state-sponsored Salon exhibitions. To combat the official control of artistic standards and sales, Monet banded together with a diverse group of like-minded, avant-garde artists to mount the first of what would be eight independent exhibitions over the years 1874 to 1886. He included The Beach at Sainte-Adresse in the second of these unprecedented Impressionist group shows, in 1876.

Inscriptions: Signed and dated (lower right): Claude Monet 1880, Provenance

This painting is one of four surviving canvases representing the interior of the station. Trains and railways had been depicted in earlier Impressionist works (and by Turner in his 'Rain, Steam and Speed'), but were not generally regarded as aesthetically palatable subjects.

Monet's exceptional views of the Gare St-Lazare resemble interior landscapes, with smoke from the engines creating the same effect as clouds in the sky. Swift brushstrokes indicate the gleaming engines to the right and the crowd of passengers on the platform.

Using rapid, often sketchlike, brush strokes, Monet captured the light as it poured through the glass roof and mixed with the whirling clouds of steam. Despite its bold style, the painting is a significant example of the Impressionist focus on city life, as seen in the architectural environment and the train itself. Later in his career, Monet would largely abandon urban views in favor of depicting the undisturbed world of nature.

Monet needed to have a success so he painted a relatively conventional work. The subject-matter was traditional - a fisherman, peasants gathering seaweed. Not a hint of the modern world such as the steam ships that constantly passed this headland. For the beach, land and sky, Monet used darker tones - browns, greys, dull greens, blues and ochres. They contrast with the paler tones of the ocean, surf and clouds to create a powerful impression of the light that signals an impending storm.

The paint is quite abstract — For example the long ripples on the shore are painted with the same definition as the pebbly beach and distant forms are as sharp as close ones. This has the effect of flattening depth into a surface pattern. These effects may well have been influenced by similar qualities in Japanese prints.

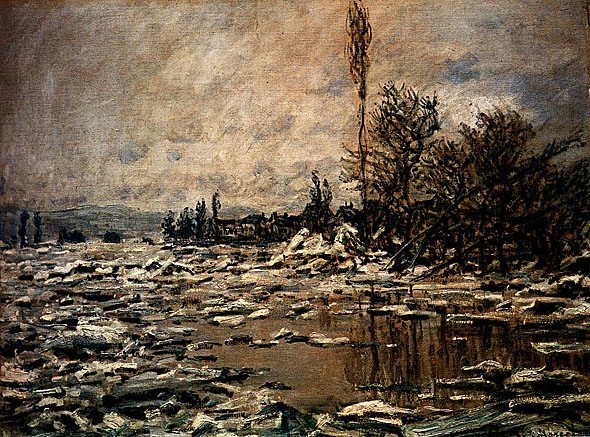

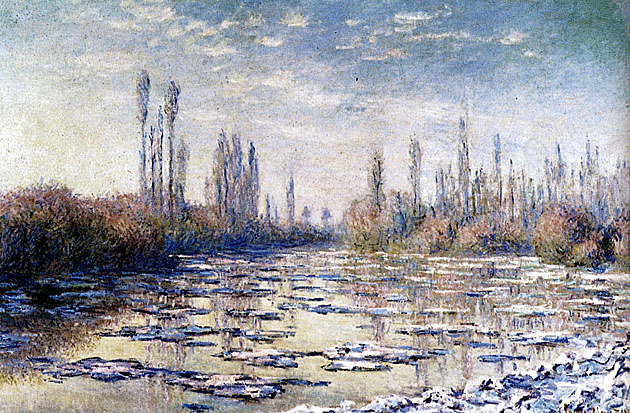

Alice Hoschedé, now living with her children in Monet's house, described the resulting thaw as terrifying, as half the melted snow slid down from the hills onto the village. Monet drew inspiration from the experience, painting scene after scene as the ice floes broke on the river.

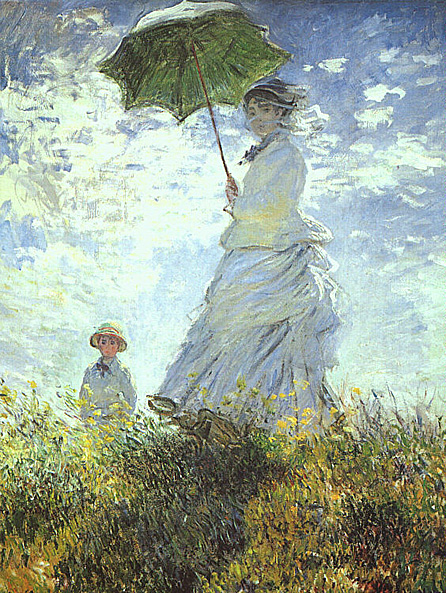

Monet re-creates the most pleasant sensations of a sunny afternoon -- the vivid flowers, the cool patches of shade, and the breezy fabrics of summer gowns -- with lightly applied dabs of color.

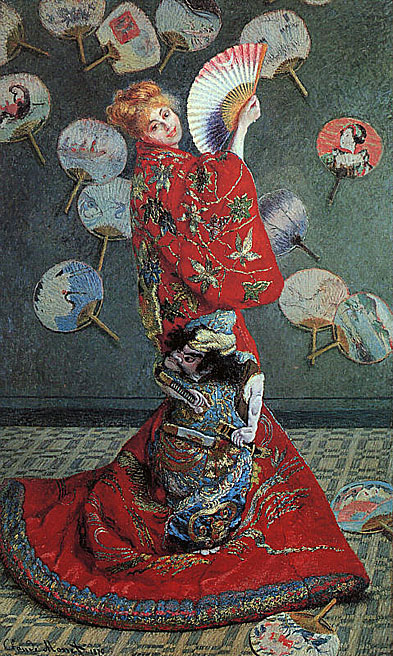

He shared it with the spectator through this bright red, blue and green composition.

Claude Monet

When the work was shown in the third Impressionist exhibition, the critical response was mixed. One critic urged the viewer to think of how well it would look in a lavishly furnished dining room, while others disparaged Monet's choice of subject as ridiculous.

The Valley of Death-The Falaise Gap

The lightning moves which wrested Mayenne and Le Mans from the enemy presaged a new type of warfare on the European continent. This was a war of movement, one which kept the Germans eternally on their heels, reeling under the impact of blows which they were unable to counter. No front lines existed in France, only pockets of resistance of variable strength. In the Cotentin peninsula gains had been measured in terms of yards and hedgerows and frightful casualties. But now the 90th Division laced its Seven League Boots and strode over the river and over the hills.

On August 10th the 90th Division was instructed to proceed northward, follow the 2nd French Armored Division, and seize a line from Carrouges to Sees, approximately sixty miles away, and due west of Paris. The Division advanced by bounds, meeting nothing of consequence in the way of resistance. Alencon was taken on the 12th and positions across the Sarthe river consolidated on the 13th.

Shortly thereafter the 90th was ordered to relieve the 5th Armored Division located northeast, and this relief was effected by the 15th, the eve of the Battle of the Falaise Gap. From the time of the landings at Normandy the 90th had passed 4,500 prisoners of war through its cages. That figure was destined to rise sharply.

The German Seventh Army, consisting of many of the elite troops of the enemy, was moving east, threatened by the British and Canadians on the North, and by the Americans in the south. Its lines had been broken, its communications shattered. One thing only could save this military organization which had once been supreme on the battlefields of Europe. One thing could save the Seventh Army . . . escape . . . move rapidly to defensible line, reorganize, fight back. But now, one thing able all . . . escape!

The line of retreat lay along the road running southeast from the city of Falaise through Chambois, 25 kilometers away. The road ran through a valley, on both side of which high ground provided perfect observation on every action and move which the enemy might make.

Until the night of August 15th there was little indication that anything big was afoot, and the first hint was an artillery barrage at the 90th's troops in the vicinity of Le Bourg St. Leonard. The next morning reports of extensive enemy activity in the Foret de Gouggern came streaming in. Artillery liaison pilots reported great convoys of enemy vehicles and troops swarming throughout the valley. Forward observers rubbed their eyes incredulously as they saw targets they had never dreamed could exist.

At noon on the 16th the enemy attacked in force the 90th's road block at Le Bourg St. Leonard in a desperate effort to clear the shoulders of their escape rout. All day the battle raged, with the town changing hands several times. Tanks battled furiously throughout the encounter, tank destroyers waded into the fight with guns blazing, the doughboys stood fast, containing the frantic Seventh Army within its narrow bottle neck. And the Artillery blasted away with everything it had.

That night the 90th was released from the XV Corps and passed to the control of a Provisional Corps whose function it was to reduce the Falaise pocket. The mission of the 90th was to attack north, seize the village of Ommeel and the high ground northeast of Chambois. Since the main road by which the Seventh Army sought escape ran directly through Chambois,t he control of that town was vital to the Americans as well as to the enemy.

The following day the Division passed to the control of V Corps, and returned once more to the First Army. And still the battle raged on. Never in history had artillery enjoyed such a field day. Observers, enjoying for the first time the luxury of perfect observation on numberless targets, radioed fire missions to their heart's content. Desperately the trapped Germans beat themselves against the side of the wall that engulfed them, hopeless they plunged into the immobile lines that hemmed them in. And all the while the artillery loaded and fired, loaded and fired, pausing only to allow the tubes to cool.

In the meantime, the infantry was by no means idle. Against do or die resistance the doughboys advanced towards Chambois, closing the bottleneck, strangling the escape route with an iron noose. One after another the objectives fell . . . Hill 137, Hill 129, Ste. Eurgenie, Bon Menil, Fough; the road leading out of Chambois was cut, and the trap was sealed.

Prisoners poured into the 90th's cages. Equipment, guns, vehicles beyond number littered the floor of the Valley. The once mighty cream of the German armies found itself being cut to bloody ribbons with no chance for escape. And still the artillery, eleven battalions, lashed the valley with high explosives, time and white phosphorous fire. Mercilessly the raked the valley, inflicting casualties, disrupting counterattacks, pouring a hail of steel into the milling remnants of the invincible conquerors of Europe.

An aerial observer, annoyed by the necessary time lapse between his reporting a target and the actual firing of the mission, shouted excitedly into his radio, "Stop computin', and start shooting."

And into the storm the unarmed Medics of the 315th Medical Battalion performed heroically under fire, evacuating the enemy wounded as well as the American casualties. A truce was called in order that the wounded might be attended and removed from the field of battle. The 315th, in spite of sniper fire (in violation of the terms of the truce), carried out its mission with unsung gallantry.

The 712th Tank Battalion and the 773rd Tank Destroyed Battalion also added their voices to the deafening salvoes that spread death in the valley. And still it continued, never pausing until the white flags appeared, timidly at first, then more and more openly. On the 20th of August the dramatic episode of the Falaise Gap moved rapidly toward its inevitable climax.

The realization had come home to the trapped enemy that the Seventh Army was a beaten force, incapable of any offensive or defensive action. And on that day, August 20th, five thousand Germans surrendered to the 90th Division. The following day the slaughter continued, with 5,500 additional prisoners flooding the cages. The battle of the Falaise Gap was over, the Seventh German Army, except for the scraps which had squeezed through before the trap was hermetically sealed, was no longer in existence. The fighting potential of the German nation had received so lethal a blow that it was never fully to recover.

The 90th had begun the action merely in a supporting role, but before the smoke had cleared the Division had become the motivating force in closing the vital gap. It had withstood the fiercest assaults of which crack German units were capable and had hurled them back. In a period of four days it had taken more than 13,000 prisoners, killed or wounded an estimated 8,000 of the enemy, but itself suffered less than 600 casualties. More than 300 enemy tanks, 250 self-propelled guns, 164 artillery pieces, 3,270 vehicles, and a variety of all type of equipment and weapons were destroyed.

So ended the greatest Allied triumph on the soil of France, the most complete and humiliating defeat ever suffered by the German armed forces. But the 90th was not content to rest on its laurels. But this time the men of the T-O Division knew they were "hot," and so did the Germans who were soon to face them . . . the brawling 90th . . . spoiling for a fight.

Framed at the top of the composition with the broad arch of the Clichy Bridge, the painting is suffused with a warm, pale gold light. This work was one of 29 works Monet presented in the fourth Impressionist exhibition.

Only cold made Monet give up, in spite of the fur coat kindly lent by Louis Aston Knight, a young American painter living in Rolleboise, near Giverny, whom they happened to met at the hotel. On December 3, Monet painted a final sketch, featuring a gondola. They left on December 7, ten weeks after their arrival, never to return. Alice's health began to fail shortly thereafter, and she died in 1911.

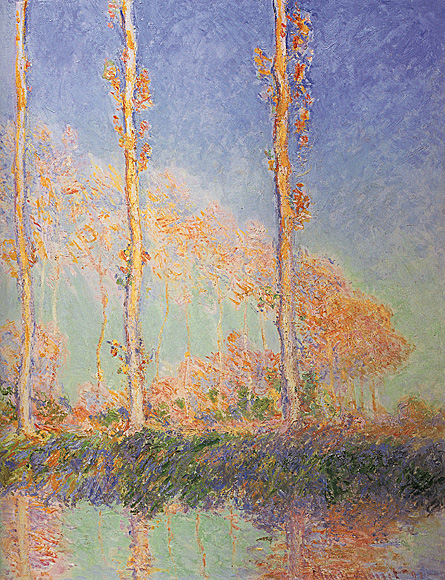

Although dated 1890, this work was actually painted the following year. In the spring of 1891 Monet began work on a series of twenty-three paintings depicting the poplars which lined the left bank of the river Epte, near Limetz, south of Giverny. On 18 June the town decided to auction off the trees. Monet persuaded a wood merchant to buy them jointly with him, on the condition that they were left standing for a few more months to enable the artist to finish his series.

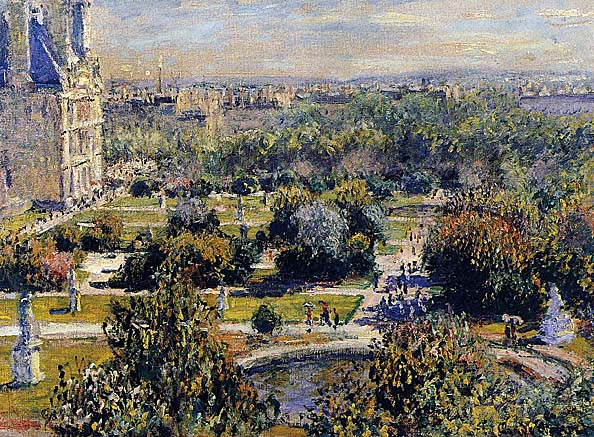

In the spring of 1867 Monet was granted official permission to install himself and his easel in an east end balcony of the Louvre. The resulting paintings are Monet's earliest images of Paris: the Quai du Louvre (The Hague, Haags Gemeentemuseum); Oberlin's Jardin de l'Infante, painted from nearly the same viewpoint; and St. Germain-l'Auxerrois (Berlin, Staatliche Museen, Nationalgalerie). These works belong to a critical moment within Monet's formation of an idiom for painting modern life. Previously, Monet's most ambitious paintings--Déjeuner sur l'Herbe or Femmes au Jardin (both 1866; Paris, Musée d'Orsay)--had focused on the individual comportment and dress of middle-class men and women taking their leisure in intimate, outdoor settings. The Paris views multiply and disperse these figures within a broad expanse of space and atmospheric phenomena, amidst a wide variety of incident, movement, and activity.

In sitting his three Paris paintings at the quai and place du Louvre, Monet could depict a central thoroughfare that had been recently enlarged, repaved, and refurbished, and at the same time, include clearly recognizable portraits of a set of historical Paris monuments. The title and foreground is given to the stately geometry of the Garden of the Princess, whose name evokes the once royal, then imperial, pedigree of the Louvre's inhabitants. Crowning the view is the cupola of the Pantheon, resting place of the great men of French history; flanking it to the left and right are the bell tower of St.-Etienne-du-Mont and the cupola of the Val du Grace. The façades, attics, and chimneys at the far left indicates the Place Dauphine on the Ile de la Cité; further back and extending to the right are the buildings along the Left Bank. The tall, dark foliage behind the younger chestnut trees along the quai both signal and obscure the pointe or terminus of the Cité, where the French flag is planted.

Wedged between the chestnut trees and the garden are the place and quai du Louvre, where dozens of figures in transit--riding, strolling, striding, or pausing--are briefly noted and dressed with a few blunt strokes of the brush. The contrast in execution between the buildings and the figures--the attention to detail, surface, and tonal gradation in much of the architecture, and the approximate, improvisational strokes of physiognomy and movement in the figures--suggests a complementary relationship between the city's historical continuities and the dynamic exchanges of contemporary life.

While offering a convincing view of a familiar site, Monet's Paris paintings do not aim for topographical precision. The effects of format and composition are evident when one compares the Jardin de L'Infante with the straightforward though more diffuse organization of the Quai du Louvre at The Hague. The clear shapes of the Oberlin canvas are stacked vertically, from the quai to the sky; while this area is viewed straight on, the garden is viewed from above. The axial disposition of the Oberlin composition is the most complex of the three Paris views. The central, vertical axis created by the Pantheon competes with the elusive slope of the quai and (invisible) Seine; the garden expands beyond the frame of the picture at a sharp angle. Robert Herbert has discussed these elisions and oblique viewpoints as a careful orchestration of the casual, random appearance of things in the modern experience of the city. At the same time, the composition's various symmetries and regular patterns invoke the ordered, controlling aspects of the newly planned city.

The Jardin de l'Infante also demonstrates the persistence--and the peculiarity--of realism in Monet's practice in the 1860s. While his later Impressionist paintings of the boulevards present a homogeneous field of painted marks, creating a strict unity of vision and sensation, the Jardin de l'Infante modulates its brushwork, address, and tonality to register differences in things: from the thicket of grey, white, and blue marks clouding the sky to the seamless expanse of the lawn; from the bright, neutral pavement to the daubed layers of foliage; and from one (briefly indicated) urban type, silhouette, or posture to another.

A. Kurlander

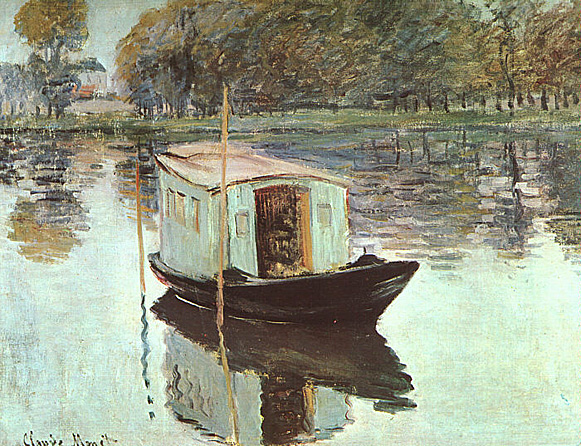

That Monet at age thirty-three purchased a boat and rendered it so faithfully is significant on a personal and a practical level. It speaks of his success, as such a boat would have been expensive. Monet earned 24,8oo francs the previous year, or twice what doctors and lawyers were making in Paris at the time, and he was ordering his wines from Narbonne and Bordeaux instead of drinking cheaper local vintages. At the same time, he must have believed that the boat was a reasonable investment. Although he was generally careful about money, he never skimped on professional expenses. He bought his, painting supplies from one of the best houses in Paris, for instance, and maintained a studio in the capital so that he could meet dealers and collectors; he was keen to ensure that his canvases would remain in superb physical condition over time (as most of his work from the Argenteuil period has). Monet also had unwavering confidence in himself as an artist it would do what it took to advance his career.

The simple design of this painting with the close-up view of the bridge was repeated in several other canvases. The fresh greens of the foliage evoke an early summer's day.

Monet found a solution by painting the shadows, coloured light, patches of sunshine filtering through the foliage, and pale reflections glowing in the gloom.

Emile Zola wrote in his report on the Salon: "The sun fell straight on to dazzling white skirts; the warm shadow of a tree cut out a large grey piece from the paths and the sunlit dresses. The strangest effect imaginable. One needs to be singularly in love with his time to dare to do such a thing, fabrics sliced in half by the shadow and the sun".

The faces are left vague and cannot be considered portraits. Camille, the artist's companion, posed for the three figures on the left. Monet has skilfully rendered the white of the dresses, anchoring them firmly in the structure of the composition – a symphony of greens and browns – provided by the central tree and the path.

Finished in the studio, the painting was refused by the jury of the 1867 Salon which, apart from the lack of subject and narrative, deplored the visible brushstrokes which it regarded as a sign of carelessness and incompleteness. One of the members of the jury declared: "Too many young people think of nothing but continuing in this abominable direction. It is high time to protect them and save art!"

Claude Monet

Source: Web Gallery of Art

Source: Art Renewal Center

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.