English Pre-Raphaelite Artist

1827 - 1910

Hunt, a founder of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was born in London, the son of a warehouse manager. Throughout his life he was a devout Christian. He was also serious minded, and lacking in a sense of humor. Hunt joined the Royal Academy Schools in 1844, where he met Millais and Rossetti, and, in fact brought them together. In 1854 Hunt decided to visit the Holy Land, to see for himself the genuine background for the religious pictures he intended to paint. The first tangible results of this journey were two paintings, 'The Scapegoat', and 'The Finding of the Savior in the Temple', which was exhibited nationally to great acclaim in 1860, and sold for the sum of 5,500 guineas, Hunt was advised on the price by Charles Dickens. This sale, which included the copyright, established the painter both financially, and artistically. Hunt's famous picture 'The Light of the World', was one of the greatest Christian images of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Hunt worked at night on this picture, in an unheated shelter in a wood near Ewell in Surrey.

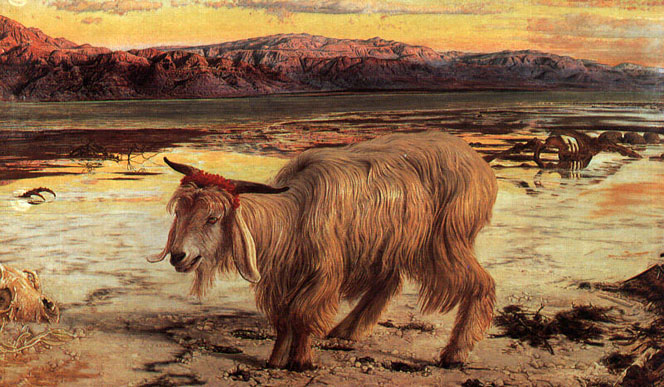

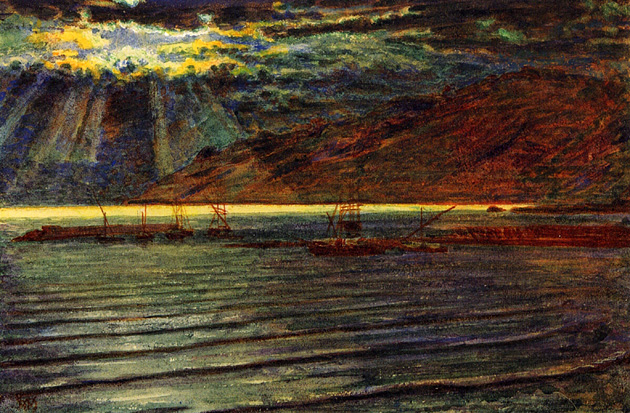

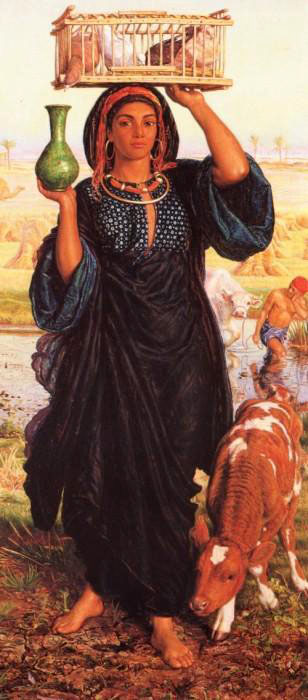

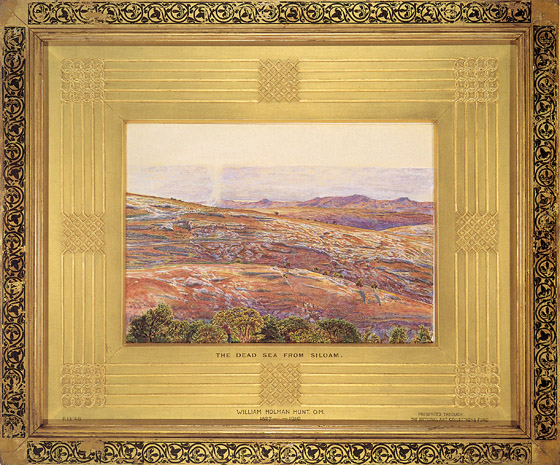

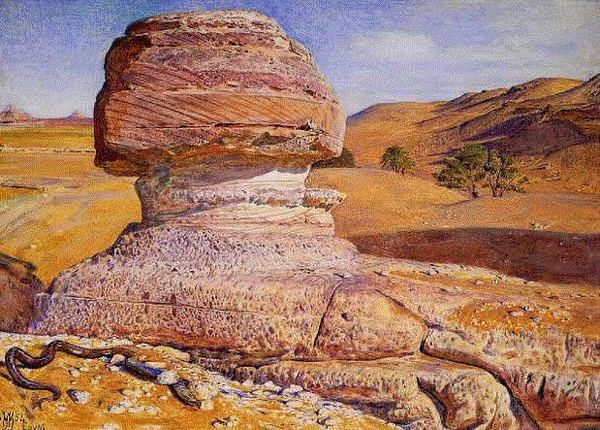

In the Book of Leviticus (which is quoted on the frame) the goat is said to bear the iniquities into a land that was not inhabited. Hunt chose to set his goat in a landscape of quite hideous desolation - it is the shore of the Dead Sea at Osdoom with the mountains of Edom in the distance. In his diary Hunt described this setting as 'a scene of beautifully arranged horrible wilderness' and he saw the Dead Sea as a 'horrible figure of sin', believing as did many at this time that it was the original site of the city of Sodom.

Initially, Hunt considered that the subject might be suitable for the animal painter Landseer, who, in the 1840's, had taken to producing threatening symbolic loch side scenes with deer. However, in March 1855, Hunt wrote to Rossetti saying that it was seeing for the first time the extraordinary sight of the Dead Sea that decided him to tackle the subject himself. Hunt returned to the edge of the sea with guides and spent about two weeks painting in the landscape and making sketches and notes. He took a white goat with him but he left blank that part of the picture that the animal occupies and did not paint the beast until he returned to his Jerusalem studio. While at Osdoom, Hunt's life was at risk from hostile tribesmen. The insistence of his guides that they get away from this dangerous spot led to his leaving earlier than he wished. He took back samples of mud and salt to help him finish the foreground. In Jerusalem Hunt also bought or borrowed sheep and goat skulls and a full camel skeleton.

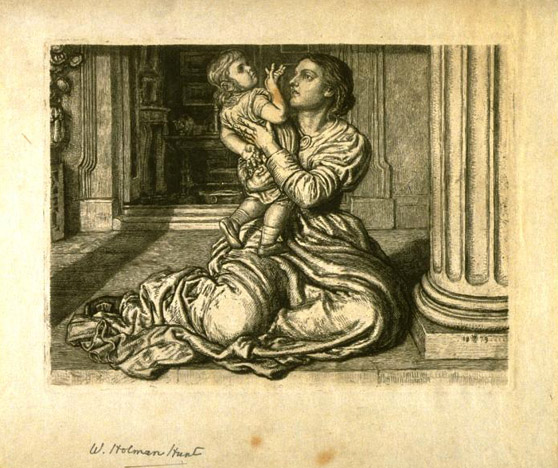

"Every year his parents went to Jerusalem for the Feast of the Passover. When he was twelve years old, they went up to the Feast, according to the custom. After the Feast was over, while his parents were returning home, the boy Jesus stayed behind in Jerusalem, but they were unaware of it. Thinking he was in their company, they traveled on for a day. Then they began looking for him among their relatives and friends. When they did not find him, they went back to Jerusalem to look for him. After three days they found him in the temple courts, sitting among the teachers, listening to them and asking them questions. Everyone who heard him was amazed at his understanding and his answers. When his parents saw him, they were astonished. His mother said to him, "Son, why have you treated us like this? Your father and I have been anxiously searching for you." "Why were you searching for me?" he asked. "Didn't you know I had to be in my Father's house?" But they did not understand what he was saying to them."

Hunt depicts the moment at which Mary and Joseph find Jesus, while the rabbis in the temple are reacting in various contrasting ways to his discourse, some intrigued, and others angry or dismissive. This depiction of contrasting reactions is part of the tradition of the subject, as evidenced in Dürer's much earlier version. Hunt would also have known Bernardino Luini's version of the subject in the National Gallery. At the time this was ascribed to Leonardo da Vinci.

"Behold, I stand at the door and knock; if any man hear my voice, and open the door, I will come in to him, and will sup with him, and he with me".

According to Hunt: "I painted the picture with what I thought, unworthy though I was, to be by Divine command, and not simply as a good subject." The door in the painting has no handle, and can therefore only be opened from the inside, representing "the obstinately shut mind". Hunt, 50 years after painting it, felt he had to explain the symbolism.

The original, painted at night in a makeshift hut at Worcester Park Farm in Surrey, is now in a side room off the large chapel at Keble College, Oxford. Toward the end of his life, Hunt painted a life-size version, which was hung in Saint Paul's Cathedral, London after a world tour where the picture drew large crowds.

This painting inspired much popular devotion in the late Victorian period and inspired several musical works, including Arthur Sullivan's 1873 oratorio 'The Light of the World'.

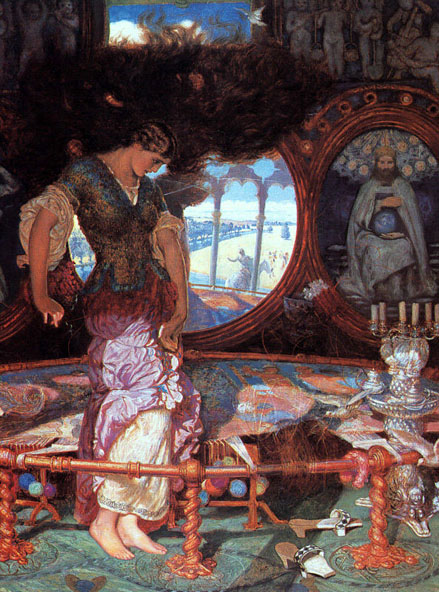

Hunt did not have the natural talent of Millais, or the intellect and vision of Rossetti. He made up for this by sheer hard work and commitment. He could have been a very successful portrait painter had he chosen to be so. In later years, as his sight started to fail, perhaps, his colors became increasingly harsh. He was still capable of great things, however, as shown by his wonderful late picture 'The Lady of Shallott', surely one of the most powerful Pre-Raphaelite images.

Alfred, Lord Tennyson, The Lady of Shalott (1842)

The lady's magnificent hair, blown by a stormy wind, frightens away the doves of peace that had settled next to her as she worked, the weaving ruined, as is her own life. The silver lamp on the right has owls decorating the top and sphinxes at the bottom to suggest wisdom triumphing over mystery, its light extinguished now that the she has succumbed to temptation. Hercules, who is portrayed to the right of the mirror is given a halo to signify him as a type of Christ, his victory over the serpent guarding the apples in the garden of the Hesperides the pagan counterpart to Christ's victory over sin. To the left of the mirror, the Virgin Mary prays over the Christ child, her humility and the valor of Hercules both exemplars of duty and foils to the Lady of Shalott, who personifies its dereliction, as signified by her wild hair and unraveling yarn.

In his last years Hunt became the Patriarch of Victorian painting. He was awarded the Order of Merit by King Edward VII in 1905. Hunt married firstly Fanny Waugh, and after her death in childbirth her younger sister Edith. He was also a far more attractive personality than is generally supposed, with a wide range of interests, which included horse racing and boxing. He died in 1910.

Source: Victorian Art in Britain.

From: Art Renewal Center

William Holman Hunt was a British painter, and one of the founders of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.

Hunt's intended middle name was "Hobman", which he disliked intensely. He chose to call himself Holman when he discovered that his middle name had been misspelled this way after a clerical error at his baptism at the church of Saint Mary the Virgin, Ewell. Though his surname is "Hunt", his fame in later life led to the inclusion of his middle name as part of his surname, in the hyphenated form "Holman-Hunt", by which his children were known.

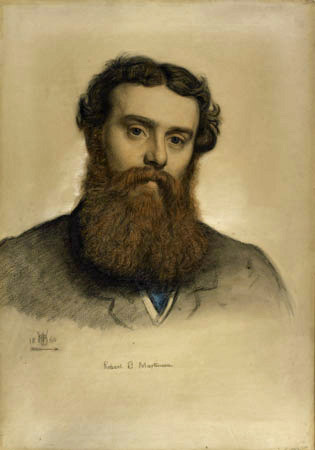

After eventually entering the Royal Academy art schools, having initially been rejected, Hunt rebelled against the influence of its founder Sir Joshua Reynolds. He formed the Pre-Raphaelite movement in 1848, after meeting the poet and artist Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Along with John Everett Millais they sought to revitalize art by emphasizing the detailed observation of the natural world in a spirit of quasi-religious devotion to truth. This religious approach was influenced by the spiritual qualities of medieval art, in opposition to the alleged rationalism of the Renaissance embodied by Raphael. He had many pupils including Robert Braithwaite Martineau (best known for his work "Last Days in the Old Home") who was a moderately successful painter although he died young.

Hunt's works were not initially successful, and were widely attacked in the art press for their alleged clumsiness and ugliness. He achieved some early note for his intensely naturalistic scenes of modern rural and urban life, such as The Hireling Shepherd and The Awakening Conscience. However, it was with his religious paintings that he became famous, initially The Light of the World (now in the chapel at Keble College, Oxford, with a later copy in St Paul's Cathedral), having toured the world. After travelling to the Holy Land in search of accurate topographical and ethnographical material for further religious works, Hunt painted The Scapegoat, The Finding of the Savior in the Temple and The Shadow of Death, along with many landscapes of the region. Hunt also painted many works based on poems, such as Isabella and The Lady of Shalott.

William Holman Hunt actually wrote a letter on this subject that I found on Shakespeare Illustrated-- that connects 19th century paintings to their roots in Shakespeare's work.

Shakespeare's song represents a Shepherd who is neglecting his real duty of guarding the sheep: instead of using his voice in truthfully performing his duty, he is using his "minikin mouth" in some idle way. He was a type thus of other muddle headed pastors who instead of performing their services to their flock--which is in constant peril--discuss vain questions of no value to any human soul. My fool has found a death's head moth, and this fills his little mind with forebodings of evil and he takes it to an equally sage counselor for her opinion. She scorns his anxiety from ignorance rather than profundity, but only the more distracts his faithfulness: while she feeds her lamb with sour apples his sheep have burst bounds and got into the corn. It is not merely that the wheat will be spoilt, but in eating it the sheep are doomed to destruction from becoming what farmers call "blown."

I really enjoy the humor in this painting. At first glance, the viewer is presented with an idyllic setting--rolling hills dotted with sheep, a happy young couple, a winding stream and a field of golden wheat.

But on closer inspection, it turns out that a number of the sheep are lying on the grass, unable to get up! You can see one of the sheep on the left of the canvas is even helplessly flailing his legs! One of the sheep has wondered across the stream and is eating barleycorn (note: in King Lear, Edgar refers to the sheep being in the corn--in Shakespeare's day, corn meant barleycorn--there was no maize until after the European discovery of the Americas), which probably isn't good for him, and refers directly to the song from King Lear. The lamb resting in the girls lap is eating green apples, which are probably making him sick as well. The girl, who at first blush seemed to be relaxing in the grass happily with the shepherd boy, actually looks a little uneasy. The shepherd boy is showing her something--a death's head moth! He's also totally neglecting his work and seems oblivious to what is happening to his flock.

All these paintings were notable for their great attention to detail, their hard vivid color and their elaborate symbolism. These features were influenced by the writings of John Ruskin and Thomas Carlyle, according to whom the world itself should be read as a system of visual signs. For Hunt it was the duty of the artist to reveal the correspondence between sign and fact. Out of all the members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood Hunt remained most true to their ideals throughout his career. He eventually had to give up painting because failing eyesight meant that he could not get the level of quality that he wanted. His last major work, The Lady of Shalott, was completed with the help of an assistant (Edward Robert Hughes).

Hunt married twice. After a failed engagement to his model Annie Miller, he married Fanny Waugh, who later modeled for the figure of Isabella. When she died in childbirth in Italy he sculpted her tomb up at Fiesole, having it brought down to the English Cemetery, beside the tomb of Elizabeth Barrett Browning. His second wife, Edith, was Fanny's sister. At this time it was illegal in Britain to marry one's deceased wife's sister, so Hunt was forced to travel abroad to marry her. This led to a serious breach with other family members, notably his former Pre-Raphaelite colleague Thomas Woolner, who had married Fanny and Edith's third sister Alice.

Hunt's autobiography Pre-Raphaelitism and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (1905) was written to correct other literature about the origins of the Brotherhood, which in his view did not adequately recognize his own contribution. Many of his late writings are attempts to control the interpretation of his work.

In 1905, he was appointed to the Order of Merit by King Edward VII. At the end of his life he lived in Sonning-on-Thames.

From: Wikipedia

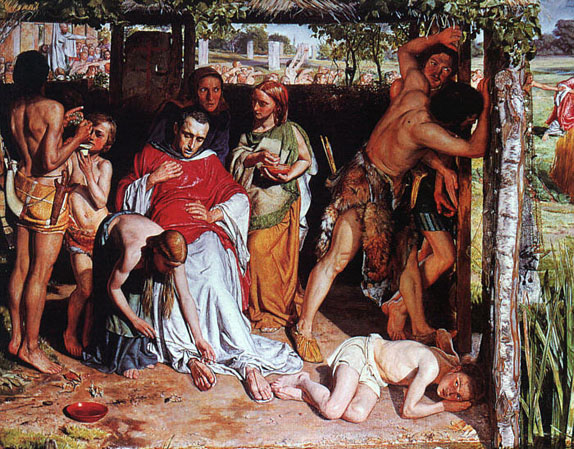

Hunt's painting depicts a family of Ancient Britons occupying a crudely constructed hut by the riverside. They are attending a missionary who is hiding from a mob of pagan Celts. A Druid is visible in the background pointing towards a missionary who is being taken by one of the mob. A stone circle is noticeable behind the missionary, but these scenes can only be glimpsed through gaps in the back of the hut used by the Christian family. The contrast between Christian and Druidic symbols is identified by the painting of a red cross over a stone within the Christian family's hut.

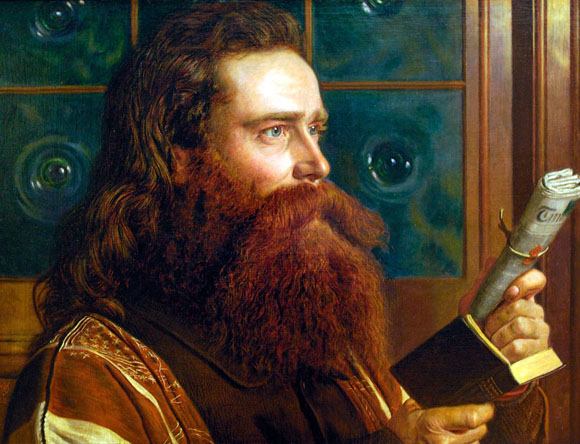

It was unusual for Hunt to find the time or money to take a holiday, but in 1860 he had funds at his disposal, having secured a record price of 5,500 guineas for 'The Finding of the Savior in the Temple' (1854-60; Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery). Caroline Fox, of Penjerrick, near Falmouth, met Hunt during this West Country trip, and memorably summed him up in her diary as 'a very genial, young-looking creature, with a large, square, yellow beard, clear blue laughing eyes, a nose with a merry little upward turn in it, dimples in the cheek, and the whole expression sunny and full of simply boyish happiness. His voice is most musical, and there is nothing in his look or bearing, in spite of the strongly-marked forehead, to suggest the High Priest of Pre-Raphaelitism'.

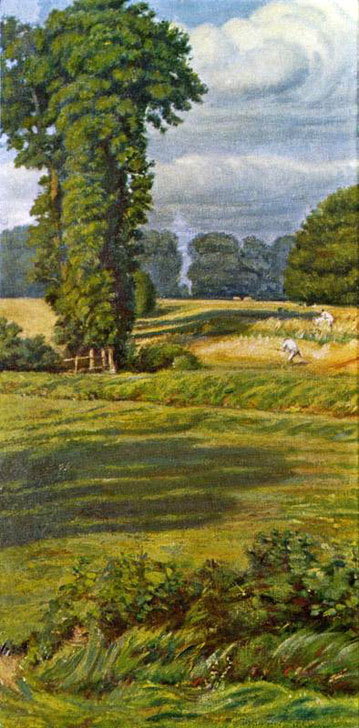

If one thinks of Hunt as a 'High Priest' with a strong didactic streak, this watercolor of 'Asparagus Island' seems atypical. Yet in a pamphlet of 1865 Hunt declared that 'the first ambition of the painter... should be to give a delightsome aspect to all his representations. If he succeeds in this it may not be possible to find a special moral... but it will be a picture - an exposition as far as it extends - of Nature's omnipresent grace'. For Hunt truth to nature became a moral imperative because he believed that nature was the repository of transcendent truth. In it - to quote Ruskin - one could trace 'the finger of God'.

The amount of detail incorporated into Hunt's works can partly be attributed to his exceptional eyesight. Indeed, it was said of him that 'on one occasion in Jerusalem, he proved to a friend, who doubted the statement, that he could see the moons of Jupiter with the naked eye'. In 'Asparagus Island' this gift enabled the artist to delineate the landscape in a way that may not seem unusual for a generation used to the zoom lens of a camera, but is extraordinary when one considers his viewpoint on the cliffs. (In a typical Hunt touch, part of the cliff is glimpsed in the immediate foreground of the watercolor). For Hunt, however, truth to nature was not enough. In the 1865 pamphlet he stated that 'a work with the profoundest philosophy or morality may be a wonderful piece of mental ingenuity; it may even be an extraordinary specimen of imitative power, but executed without enthusiastic love of the object, it will be repulsive rather than attractive to the eye, and the workman will be proved no painter, in the great sense, whatever else he may be'. Hunt's landscapes are imbued with 'enthusiastic love of the object', which - whether in oil or watercolor - makes them particularly memorable. His exploration of the effects of light on land and water can be combined with an underlying symbolic dimension, as in Our English Coasts, 1852 (Tate, London), but it does not have to be; 'Fairlight Downs - Sunlight on the Sea', begun in 1852, is a notable example of such a symbol-free landscape. In both these pictures and in 'Asparagus Island' Hunt used sophisticated optical effects to convey sunlight in an utterly convincing way. Indeed, in a lecture of 1883 Ruskin was to claim that Our English Coasts, 1852 'showed us, for the first time in the history of art, the absolutely faithful balances of color and shade by which actual sunshine might be transposed into a key in which harmonies possible with material pigments should yet produce the same impressions upon the mind which were caused by the light itself'.

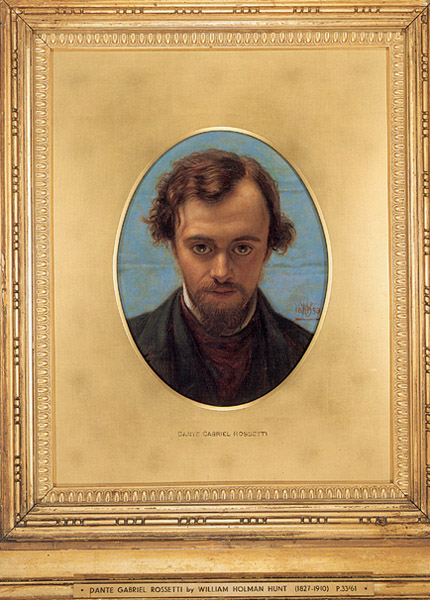

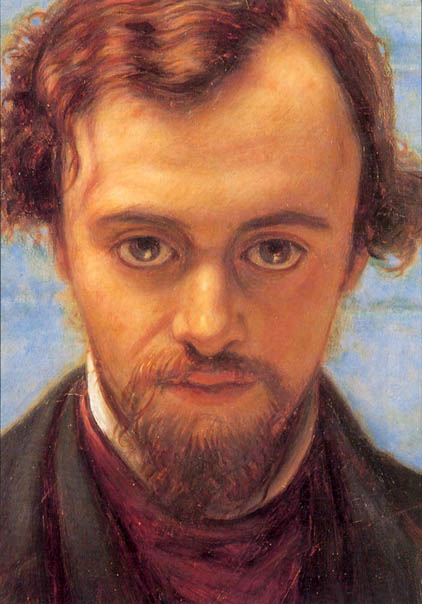

On 12 April 1853, the remaining members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood met for breakfast in Millais's studio, to make portrait drawings of each other which could be sent to Thomas Woolner, who had immigrated to Australia six months before. Hunt's drawings, of Millais and Rossetti, are the finest of this series, most of which are in the National Portrait Gallery. His chalk drawing of Rossetti (now at Manchester City Art Gallery) had become badly rubbed by 1882, and Hunt painted this replica in oils to commemorate his friend's recent death.

Italian Features

In his autobiography, Hunt describes the young Rossetti's "southern" (i.e. Italian) features, with "grey eyes, looking directly only when arrested by external interest".

It is likely that Rossetti was constantly looking up at Hunt from work on his reciprocal portrait drawing (now at Birmingham), which explains the slightly foreshortened angle of the head.

In 1852 Lear was introduced to William Holman Hunt that Lear might learn an improved technique from the Pre-Raphaelite. A long association between the two followed; despite Lear's sixteen years seniority to Hunt he was aware of the advances that the younger generation had made in terms of the use of color and the understanding of light; he shared their reverence for the detail of nature, and was determined to learn from them.

Lear and Hunt spent part of the summer and autumn of 1852 together at Fairlight on the coast near Hastings. During this time Hunt was painting his two landscape masterpieces: 'Our English Coasts' 1852 'Strayed Sheep' (Tate Gallery) and 'Fairlight Downs -- Sunlight on the Sea'. Lear's subsequent oil paintings, in their treatment of clear sunlight and use of prismatic color, demonstrate the importance of this experience. In the autumn of 1852 Lear wrote to Hunt: "I really cannot help again expressing my thanks to you for the progress I have made this autumn . . . I am now beginning to have a perfect faith in the means employed, and if the Thermopylae' turn out right I am a P.R.B. forever." Lear lived for periods of time in Rome, Corfu, and finally at San Remo on the Italian Riviera to which place he moved during the winter of 1870-71.

Like several of his other works, this one employs the curved mirror of Jan van Eyck's 'Arnolfini Marriage Portrait', which Hunt knew from the National Gallery. It and other mirrors appear again in 'The Lady of Shalott' and his portrait of 'Fanny Waugh Hunt'. Here it reveals that the woman, who appears to be looking directly at the spectator, is in fact gazing into the fireplace, thus making this painting yet another Victorian representation of the contemplative or dreaming woman.

Even though Hunt stated that 'Il Dolce Far Niente' had no didactic purpose or meaning, he devoted as much time and effort to rendering details of texture and surface as he did in works like 'The Shadow of Death'. The flowers, the contrast of shawl and dress, the ivory and wood chair, the figure's jewelry, and the reflections all show Hunt trying to create a tour de force that implicitly challenges Rossetti's paintings, as if Hunt was trying to show the way they should be painted. - George P. Landow

Hunt had drawn an illustration to the poem in 1848, shortly after the foundation of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, but he had not developed it into a completed painting. The drawing portrayed a very different scene, depicting Lorenzo as a clerk at work while Isabella's brothers study their accounts and order around underlings.

Hunt returned to the poem in 1866, shortly after his marriage, when he began to paint several erotically charged subjects. His sensuous painting 'Il Dolce Far Niente' had sold quickly, and he conceived the idea for a new work depicting Isabella. Having travelled with his pregnant wife Fanny to Italy, Hunt began work on the painting. However, after giving birth, Fanny died from fever in December 1866. Hunt turned the painting into a memorial to his wife, using her features for Isabella. He worked on it steadily in the months after her death, returning to England in 1867, and finally completing it in January 1868. The painting was purchased and exhibited by the dealer Ernest Gambart.

The painting portrays Isabella, unable to sleep, dressed in a semi-transparent nightgown, having just left her bed, which is visible with the cover turned over in the background. She drapes herself over an altar she has created to Lorenzo from an elaborately inlaid prie-dieu over which a richly embroidered cloth has been placed. On the cloth is the majolica pot, decorated with skulls, in which Lorenzo's head is interred. Her abundant hair flows over the pot and around the flourishing plant, reflecting Keats's words that Isabella "hung over her sweet Basil evermore, /and moistened it with tears unto the core."

The emphasis on sensuality, rich colors and elaborate decorative objects reflects the growing Aesthetic movement and similar features in the work of Hunt's Pre-Raphaelite associates John Everett Millais and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, such as Millais's Pot Pourri and Rossetti's Venus Verticordia. The pose of the figure also resembles Thomas Woolner's sculpture Civilization, which was partly modeled by Fanny's sister Alice.

Hunt's work influenced several later artists, who adopted the same subject. Most notable are the paintings by John White Alexander (1897) and John William Waterhouse (1907). Alexander and Waterhouse reproduce Hunt's title and develop variations on his composition. Alexander's composition adapts the subject to a Whistlerian style. Waterhouse reverses the composition, and places the scene in a garden, but retains the motif of the water-jug and the decorative skull.

OR

The Pot of Basil

A Story from Boccaccio

Valentine:

Now I dare not say

I have one friend alive: thou wouldst disprove me

Who should be trusted, when one's own right hand

Is perjur'd to the bosom?

Proteus:

I am sorry I must never trust thee more,

But count the world a stranger for thy sake.

My shame and guilt confounds me.

Forgive me, Valentine; if hearty sorrow

Be a sufficient ransom for offence,

I tender't here; I do as truly suffer

As e'er I did commit.

Proteus had abandoned his first love, Julia, and fallen in love with Silvia, the girl loved by his best friend, Valentine. Silvia was the daughter of the Duke of Milan. Proteus connived to have Valentine, now his rival, banished by the Duke. Silvia went looking for Valentine, but was abducted by outlaws who took her into a forest. Proteus finds her, rescues her, and demands sex as a reward; Silvia refuses. Valentine happened to be close by and to observe that from hiding. He comes out, and in the scene pictured, angrily confronts Proteus. Julia also happens upon them, as she, disguised as a man (at left in the picture) was searching for Proteus. At the end everything will get straightened out, and there will be a happy double wedding: Valentine with Silvia, and Proteus with Julia.

Hunt was not really concerned with an accurate depiction of the ceremony and that is why he does not include the people attending or a proper view from the tower. In a letter to the 'Pall Mall Gazette' Hunt commented that he wished the painting: "to represent the spirit of a beautiful, primitive and in a large sense eternal service, which has only been in part restored on the tower, even to the floral fullness of three centuries since, but which still carries evidence in it of the origin of our race and thoughts in the same cradle with the early Persians. This was the kernel of the scene which I had to extract."

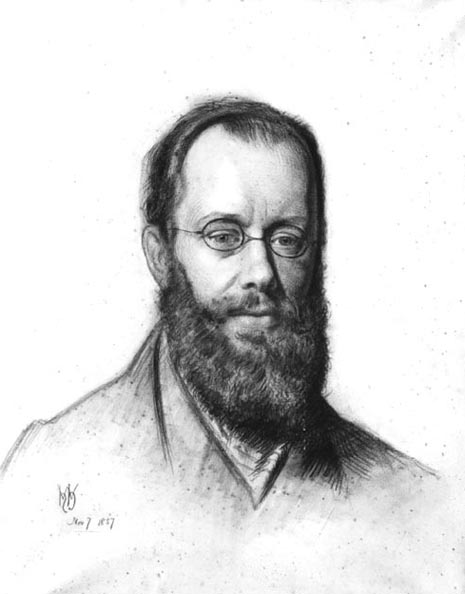

Monk was born near Ottawa in 1827. Seized with religious fervor (he trained briefly for the Anglican ministry), he worked his way as a sailor to Palestine in 1853 to work on an early kibbutz. Hunt met Monk near Jerusalem in 1854, where Hunt had gone to do his famous painting 'The Scapegoat'. The two shared the idea of a Jewish return to Palestine and Jerusalem as a centre for world government.

Monk returned home and wrote a book promoting this idea and with anonymous financial support from John Ruskin had it published in England in 1858, the same year he sat for this portrait. According to the Dictionary of Canadian Biography, "Monk held that railways, steamships, and the telegraph made possible a world government based in Jerusalem whose first act of justice would be the full emancipation of the Jews."

In 1864, Monk was the sole survivor of a shipwreck off the northeast coast of Canada, after which he was given to various personal eccentricities - a refusal to cut his hair or beard, a fear of germs, a preference for sleeping and eating outdoors, and a habit of plunging his whole head into ice-cold water to relieve his severe pains. In Ottawa in the 1870's he worked for the Ottawa Daily Citizen and devoted his energies to the creation of the Palestine Restoration Fund and the idea of an international tribunal to ensure world peace. He died in Ottawa in 1896.

An inscription in Edith's hand on the back of this portrait indicates that it was framed with two other silver points of the children and hung in Draycott Lodge, the house acquired by the family in 1881.

Drawing on part of the Bible not used today, this painting shows Mary to be staring at a shadow that predicts Jesus' crucifixion. Up until this point she had thought Jesus would be a king of earthly wealth, rather than spiritual.

Though this painting took four years to produce, rather than 12, "Hunt repainted Christ's face daily almost, trying to create an effect that was impossible to get," says Locnan. The Pre-Raphaelite motto of staying true to nature extended beyond Hunt's botanical subjects - everything had to be perfect.

A letter from Holman Hunt to Miss E. Tuckett, dated June 6th 1861 relates "on Saturday I intend to do a rough portrait of my sister in oil".

Both paintings were inspired by John Keats' poem of the same name. The poem was based upon the ancient belief that if a young woman prayed to Saint Agnes on the eve of her feast, then she would see in her sleep the face of the man she was destined to marry. Madeleine and Porphyro, two lovers who have been kept from each other's arms by the jealous rivalry between their two families, are the principal figures of the poem and the painting. On 'Saint Agnes Eve', Porphyro gained access to Madeleine's bedroom, pretending at first to be a vision. After revealing his true identity he persuaded her to leave her father's house and marry him.

Hunt's painting illustrates the penultimate verse of the poem, in which the two lovers are described as escaping. The following lines from Keats' poem were included in the catalogue of the 1848 Royal Academy Exhibition when the larger version was first shown:

'They glide, like phantoms into the wide hall;

Like phantoms, to the iron porch they glide;

Where lay the Porter, in uneasy sprawl,

With a huge empty flagon by his side:

The wakeful bloodhound rose, and shook his hide,

But his sagacious eye an inmate owns;

By one, and one, the bolts full easy slide:-

The chains lie silent on the footworn stones

The key turns, and the door upon its hinges groans.'

Nobody else is awake in the poem, rather 'In all the house was heard no human sound'. However, Hunt has increased the tension of the moment of escape by adding feasting guests of Madeleine's father to the scene. These debauched partygoers are significantly placed on the left hand side (traditionally the side associated with evil), in contrast to the goodness and piety of the couple escaping through a door on the right (traditionally the side of righteousness).

And he [Jesus] said unto them, Which of you shall have a friend, and shall go unto him at midnight, and say unto him, Friend, lend me three loaves; For a friend of mine in his journey is come to me, and I have nothing to set before him? And he from within shall answer and say, Trouble me not: the door is now shut, and my children are with me in bed; I cannot rise and give thee. I say unto you, though he will not rise and give him, because he is his friend, yet because of his importunity he will rise and give him as many as he needed.

And I say unto you, Ask, and it shall be given you; seek, and ye shall find; knock, and it shall be opened unto you.

For every one that asked received; and he that sought found; and to him that knocked it shall be opened.

John Everett Millais had illustrated this same text in 'The Parables of Our Lord' (1864). Unlike Hunt, he chose to depict the friend handing the importunate neighbor the requested bread. If Hunt's figure of the pleading late-night visitor draws upon any of Millais's illustrations to 'The Parables of Our Lord', it follows "The Foolish Virgins" in representing a person standing against a closed door.

'The Importunate Neighbor', however, relates more obviously to Hunt's own 'The Light of the World' since it provides an obvious companion image or complement to the artist's first great popular success. 'The Light of the World' depicts Christ knocking on the door of the human heart, and it thus represents the way God in his grace awakens the human heart and conscience. 'The Importunate Neighbor', on the other hand, represents man seeking God - and God welcoming the seeker. For as Jesus tells his disciples: "Ask, and it shall be given you; seek, and ye shall find; knock, and it shall be opened unto you." Both paintings, then, create images of divine grace. In 'The Importunate Neighbor' man is the active agent, the seeker; in 'The Light of the World' Jesus is the seeker. Considered with respect to standard Evangelical paradigms of conversion experience, the two pictures represent subsequent stages of man's voyage to God, for whereas the earlier painting, which Hunt claimed recorded his own visionary conversion experience, depicts the first instant when man awakens to God, the second shows the awakened conscience, the convert, in search of his God and his salvation.

Such tensions between the sexes were, however, shown to reappear whenever women entered public spaces. In Lewis's Seraff, some female shoppers get into difficulties in their dealings, while in William Holman Hunt's 'Lantern-Maker's Courtship', a girl's modesty is compromised when she visits the stall of her fiancé. In its most extreme form, this vulnerability of women in the public sphere is represented in scenes of slavery, such as William Allan's 'The Slave Market', Constantinople, in which women have themselves become the commodity.

(Lines from Coventry Patmore's Tamerton Church Tower).

The colossal Sphinx, near the group of pyramids at Jizeh, which lay half buried in the sand, was uncovered and measured by Caviglia. It is about 150 feet long, and 63 feet high. The body is made out of a single stone; but the paws, which are thrown out about fifty feet in front, are constructed of masonry.

The Sphinx of Sais, formed of a block of red granite, twenty-two feet long, is now in the Egyptian Museum in the Louvre. There has been much speculation among the learned, concerning the signification of these figures. Winckelmann observes that they have the head of a female, and the body of a male, which has led to the conjecture that they are intended as emblems of the generative powers of nature, which the old mythologies are accustomed to indicate by the mystical union of the two sexes in one individual; they were doubtless of a sacred character, as they guarded the entrance of temples, and often formed long avenues leading up to them.

In landscape and figures, Hunt sought to reproduce as closely as possible the event as it might have looked. In one of his letters to Harold Rathbone he wrote:

'I am always interested to the deepest extent in the illustration of religious history by such means. Since I first knew the East, the opportunities of illustrating old events by existing customs and tradition has enormously decreased, and in another fifty years the world will wonder why, when the mood of European manners had not destroyed primitive forms, painters had not full worked to perpetuate these'

Sidney Colvin characterized Hunt's attitude well:

'He shows himself a child of his age by attending first of all to geography and ethnology and archaeology and local color, performing the work of "Societies of Biblical Archaeology'.

Hunt's interest in depicting scriptural episodes with geographical and historical accuracy was not merely scientific but designed to awaken the spectator's religious emotions and make him confront the problem of whether or not these biblical events had taken place.

This is one of a group of portrait drawings Hunt made of his artist friends.

Hunt gave this drawing and the one of Edward Lear to the Walker in gratitude for the encouragement and prizes he had received from the Liverpool Academy in the 1850's.

Although the Self-portrait's setting is not one of its dominant elements, it does have important bearing upon the overall meaning of the painting. One would therefore like to know precisely what it represents, and several possibilities come to mind. Although we know from Hunt's letters that the picture was painted in England, Hunt seems to be depicting himself within one of his foreign studios. The painter, who began the picture in 1867, could be representing himself at work in his Florentine studio. This possibility is suggested since the room's architecture bears some slight resemblance to that in Isabella and the Pot of Basil, 1866-67, which he painted in Florence. He could also be representing himself at work in his Jerusalem studio -- a possibility argued for by the apparent likeness of the window or niche on the right side of the canvas to that in 'The Shadow of Death', 1869-1873. If, as seems likely, the Self-Portrait represents Hunt at work within his studios in either Jerusalem or Florence, it therefore portrays him painting in a non-English environment -- the artist as traveler and art pilgrim. (In contrast, the pen and ink sketch of himself painting the pyramids and armed with pistol and rifle (this last implement he used to steady his brush) which sketch he sent in a letter of April 26 and 27, 1854 to Thomas Combe, emphasizes Hunt the adventurer -- the kind of role he stressed throughout his memoirs and correspondence.

The wonder and delight that Hunt experienced in the Middle East encouraged him not only to depict himself in garb of the region but also to return again and again. Sixteen years after he wrote his enthusiastic description of Cairo to Rossetti, the painter attempted to make William Bell Scott understand that he found "true wonder" in traveling through Palestine. "We pass not merely from village to town and from town to desert, or to an Arab encampment, lying down for the night's rest under the unscreened stars; but we pass from century to century, from Abraham to Cambyses, from Herodotus to Jesus Christ, then to Mohammed and so to the Crusaders. There are, too, such undreamed-of scenes as though they did not belong to this world but rather to the moon". Hunt's concern with the Middle East, his delight in it, stems from a characteristic attempt to combine imagination and fact, for the Middle East was a land of wonder, fantasy, and exotic life -- something that had great appeal for him -- and at the same time it was a land that forced him as a painter to utilize his talents for detailed representation. The Holy Land, in other words, gave Hunt, as it gave David Roberts, J. F. Lewis, Thomas Seddon, and so many other nineteenth-century artists of all nations, the opportunity to combine the appeals of realism and imagination, physical fact and fantasy.

Given Hunt's stern morality and his own conceptions of high art, one can readily understand his later dislike of Shelley and his poetry. What is perhaps surprising is that Hunt includes Dante with Shelley as one of those guilty of the "cant of genius." Immediately after telling William Bell Scott that he takes exception to "poetic maunderings" of "higher men" than Shelley, he makes it clear that the author of the Divine Comedy is his chief example:

Dante throws glamour over the story of Paolo and Francesca which is not healthy and the whole tone of his own spooneyings in the Vita Nuova and the whole scheme of the Inferno in which he puts men, known individuals, into eternal punishment seems to me like the real sin against the Holy Ghost. Every human judgment should stop short of that. Virgil's imaginings are quite of another spirit and the fact of Dante following him under such distinct responsibilities has always made me think less of his intellect and more of his narrowness, and cruelty. His example has I think introduced the wretched principle of 'poetic justice' as a make up for much unwholesome gloating over brilliant vice".

The painter did not come late to such views of the great Italian poet, for more than two decades earlier, in a letter of July 3, 1865, he had made similar objections to Tupper:

(William Michael Rossetti's) translation of Dante interested me very much but it brought me to the conclusion that Dante was a miserable egotistical professional genius, in no way akin to the great family which contained Shakespeare, Homer - or even Goethe. Imagine S or H describing himself as kicking the imprisoned head of a poor wretch doomed for eternity to be frozen into a sea of ice and saying he did not know whether he had done it by chance or design - or still further think of one or other getting a history of the life of a similar miserable out of him by a sacred promise to clear the frozen tears away from his eyes and then leaving him neglected with the reflection that to be such false to such as one were courtesy. I had some idea that the great Italian was an imposter from my knowledge of the Vita Nuova and the incident in his life at Casa del Scala's court but I did not like to trust this.

Hunt's moral objections to Dante provided the major impetus for his dislike of a poet idolized by both Ruskin and the Pre-Raphaelites, but there were two other contributing factors as well. In a letter of June 16, 1869 the painter complained to Tupper from Florence that "from high to low here the people have no sense of responsibility, no true sense of personal dignity. They believe in lying and assignations and I don't wonder looking at their literature from Dante, Boccaccio and down to Goldoni". This bitter dislike of Italy and the Italians was largely the result of several painful experiences in Florence after his wife's death there. Not only was Italy the scene of his wife's death, but he almost lost his infant son there as well - and largely, he believed, because of the selfishness and dishonesty of Italian midwives. Several local women purporting to be wet-nurses had apparently swindled the bereaved father, so that the infant Cyril almost died of malnutrition before their actions were discovered. The last one, when relieved of her position, told the still stricken father that she hoped the infant would die. Meanwhile, his models, who demanded advance payment, failed to return and the stone carver who was preparing Fanny Waugh Hunt's gravestone also cheated the painter.

Furthermore, Hunt makes it clear in this same letter to Tupper that his dislike of Dante - and the Italians - had another source, for as he told his friend, he made his criticisms "with a strong fiendish determination because it seemed to me from one or two words you said you had been talked over too much by William (M. Rossetti). We could not then go into the subject - it was about Machiavelli. I am hot on the subject for I believe that these Italian geniuses little by little are spoiling the standard of morality in English literature. Nothing makes me wish I could write well more than the desire to avow my ideas on this subject and in despair on this point, I wish I could make somebody else a convert to my views". His mention here and in other letters of "these Italian geniuses" and "professional geniuses" suggests that his increasing dislike of Dante Gabriel Rossetti and his supporters contributed importantly to his distaste for Dante Alighieri. Certainly, his striking out at the greater Dante's morality and character served Hunt as a way to criticize the man whom he came to believe had betrayed him in a number of ways - ways which ranged from philandering with the woman Hunt had planned to marry to claiming undue importance in the foundation of an artistic movement that Hunt thought he had done much to destroy. He wrote to Tupper that "to attack Dante requires indifference to the opinions of all professional geniuses or their admirers, the largest and most influential class in intellectual society in Europe"; and perhaps the desire not to seem eccentric on yet another point made Hunt refrain from making such comments in Pre-Raphaelitism and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood where discussion of the great Italian poet is conspicuously absent.

At any rate, Hunt's dislike for Dante encouraged him to hold even more fiercely his beloved nationalistic theory of the arts. This artistic nationalism, one should emphasize, was never simple narrow-minded chauvinism. Rather, like Ruskin, the painter believed that every nation's arts were the expression of its character as well as its testament to later ages. He was therefore always troubled by the thought that England might fail to leave such an artistic legacy, and whenever possible he did his best to encourage the creation of a uniquely English art and poetry. Characteristically, he wrote to Sir William Watson on September 25, 1891:

Your poems come to me bringing pleasure. . . . The imagination is more welcome because it is English - that is manly, open aired and rebounding. The strain of much recent poetry is too self retired for our red blooded race. One may profit by a mood for Dante, but it is then only for part of our complete appetite. Adopted in our language the strain (has) grown stale and jaundiced even when the form is accomplished, as it often is. Perhaps I have more determinedly formed this opinion from having seen much of the insincerity of the sentiments thus expressed, and poetry is worth nothing if it is not a genuine revelation of the inventors soul. I hail with comfort all indications of return to the honest tone of mind of Dan Chaucer, and of all true Britons since. The stilted posing vanity cabins all sterling (or: starting) vitality; in my Art in one form or the other - like the tares which the evil one sewed - it is always trying to choke up the real bread of life.

As Holman Hunt's closing remark makes clear, his views of poetry were always closely related to his conceptions of painting - and always implicit defenses of his own form of Pre-Raphaelitism. Earnest to the end, Hunt conceived of painting and poetry as sacred enterprises, and those who misused them as servants of the Evil One.

Source: Art Renewal Center

Source: William Holman Hunt Online

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.