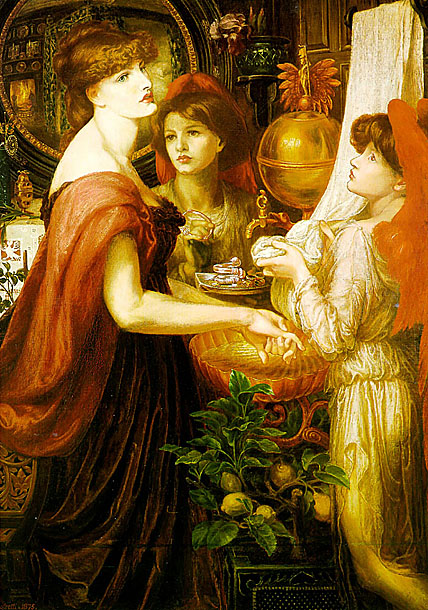

1828 - 1882

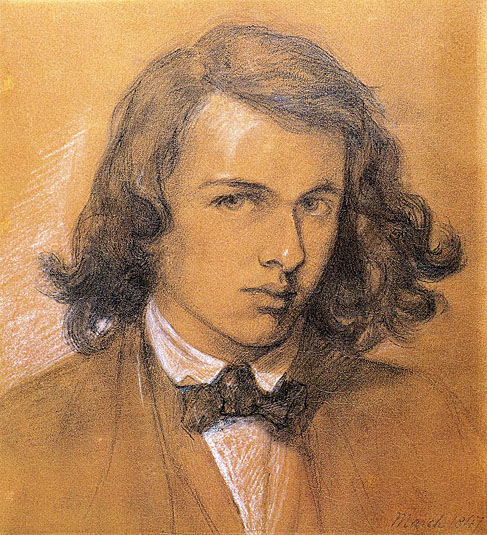

The son of émigré Italian scholar Gabriel Pasquale Giuseppe Rossetti, D.G. Rossetti was born in London, England and originally named Gabriel Charles Dante Rossetti. His family and friends called him "Gabriel", but in publications he put the name Dante first (in honor of Dante Alighieri). He was the brother of poet Christina Rossetti, the critic William Michael Rossetti, and author Maria Francesca Rossetti, and was a founder of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood with John Everett Millais and William Holman Hunt.

Like all his siblings, he aspired to be a poet and attended King's College School. However, he also wished to be a painter, having shown a great interest in Medieval Italian art. He studied at Henry Sass's Drawing Academy from 1841 to 1845 when he enrolled at the Antique School of the Royal Academy, leaving in 1848. After leaving the Royal Academy, Rossetti studied under Ford Madox Brown, with whom he was to retain a close relationship throughout his life.

Following the exhibition of Holman Hunt's painting The Eve of St. Agnes, Rossetti sought out Hunt's friendship. The painting illustrated a poem by the then still little-known John Keats. Rossetti's own poem "The Blessed Damozel" was an imitation of Keats, so he believed that Hunt might share his artistic and literary ideals. Together they developed the philosophy of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Rossetti was always more interested in the Medieval than in the modern side of the movement. He was publishing translations of Dante and other Medieval Italian poets, and his art also sought to adopt the stylistic characteristics of the early Italians.

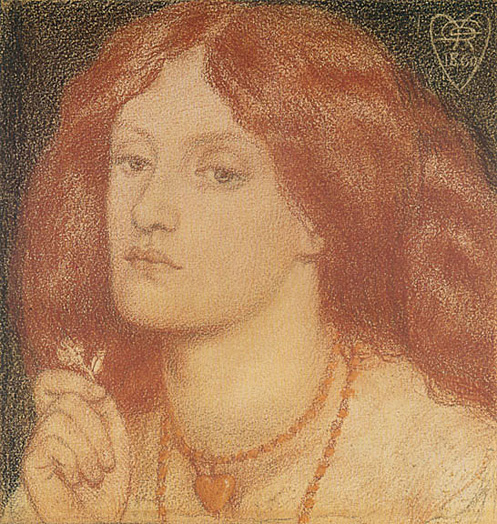

In 1850, Rossetti met Elizabeth Siddal, who became an important model for the Pre-Raphaelite painters. They were married in 1860.

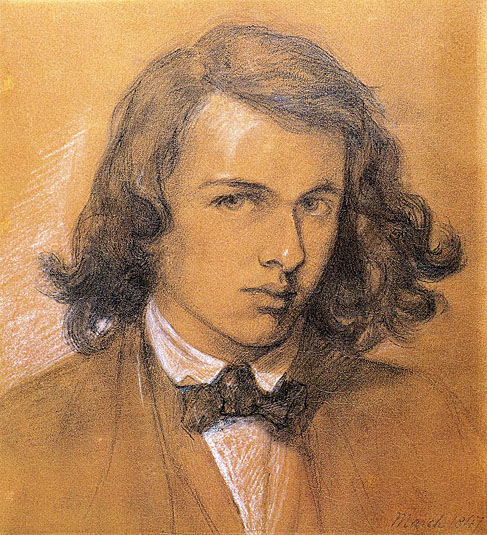

Rossetti's first major paintings display some of the realist qualities of the early Pre-Raphaelite movement. His Girlhood of Mary, Virgin and Ecce Ancilla Domini both portray Mary as an emaciated and repressed teenage girl. His incomplete picture Found was his only major modern-life subject. It depicted a prostitute, lifted up from the street by a country-drover who recognises his old sweetheart. However, Rossetti increasingly preferred symbolic and mythological images to realistic ones. This was also true of his later poetry. Many of the ladies he portrayed have the image of idealized Botticelli's Venus, who was supposed to portray Simonetta Vespucci.

Although he won support from John Ruskin, criticism of his paintings caused him to withdraw from public exhibitions and turn to watercolors, which could be sold privately.

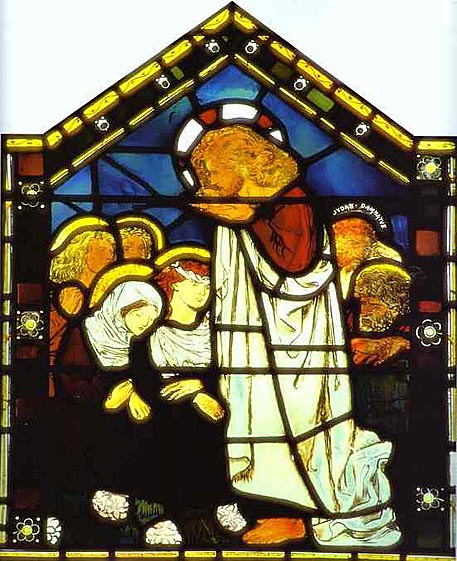

In 1861, Rossetti published The Early Italian Poets, a set of English translations of Italian poetry including Dante Alighieri's La Vita Nuova. These, and Sir Thomas Malory's Morte d'Arthur, inspired his art in the 1850s. His visions of Arthurian romance and medieval design also inspired his new friends of this time, William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones. Rossetti also typically wrote sonnets for his pictures, such as "Astarte Syraica". As a designer, he worked with William Morris to produce images for stained glass and other decorative devices.

Both these developments were precipitated by events in his private life, in particular by the death of his wife Elizabeth Siddal. She had taken an overdose of laudanum shortly after giving birth to a dead child. Rossetti became increasingly depressed, and buried the bulk of his unpublished poems in her grave at Highgate Cemetery, though he would later have them exhumed. He idealized her image as Dante's Beatrice in a number of paintings, such as Beata Beatrix.

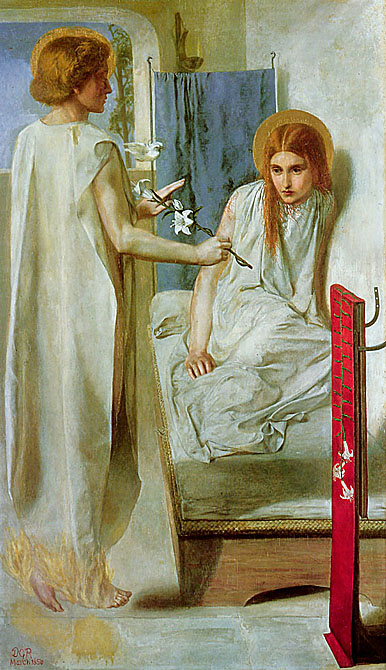

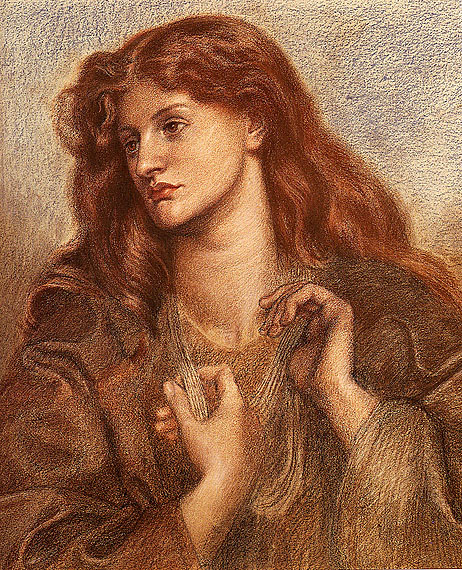

These paintings were to be a major influence on the development of the European Symbolist movement. In these works, Rossetti's depiction of women became almost obsessively stylized. He tended to portray his new lover Fanny Cornforth as the epitome of physical eroticism, while another of his mistresses Jane Burden, the wife of his business partner William Morris, was glamorized as an ethereal goddess.

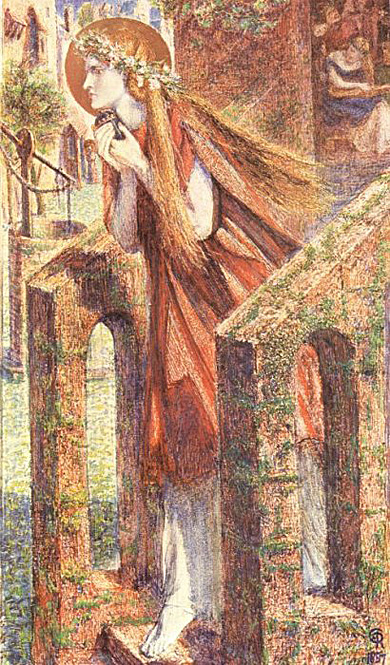

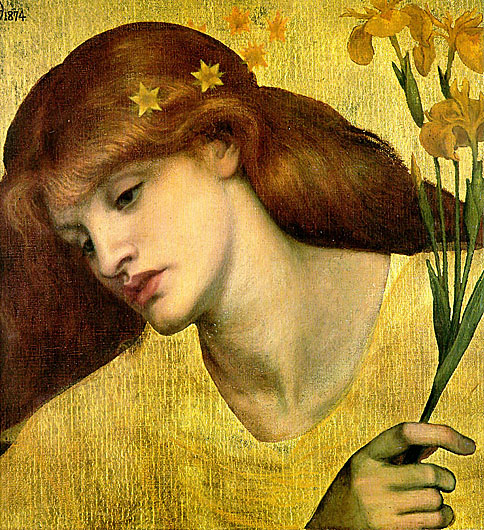

A Vision of Fiammetta (1878), one of Rossetti's last paintings is now in the collection of Andrew Lloyd Webber.During these years, Rossetti was prevailed upon by friends to exhume his poems from his wife's grave. This he did, collating and publishing them in 1870 in the volume Poems by D. G. Rossetti. They created a controversy when they were attacked as the epitome of the "fleshly school of poetry". The eroticism and sensuality of the poems caused offense. One poem, "Nuptial Sleep", described a couple falling asleep after sex. This was part of Rossetti's sonnet sequence The House of Life, a complex series of poems tracing the physical and spiritual development of an intimate relationship. Rossetti described the sonnet form as a "moment's monument", implying that it sought to contain the feelings of a fleeting moment, and to reflect upon their meaning. The House of Life was a series of interacting monuments to these moments-an elaborate whole made from a mosaic of intensely described fragments. This was Rossetti's most substantial literary achievement.

In 1881, Rossetti published a second volume of poems, Ballads and Sonnets, which included the remaining sonnets from the The House of Life sequence.

Toward the end of his life, Rossetti sank into a morbid state, darkened by his drug addiction to chloral and increasing mental instability, possibly worsened by his reaction to savage critical attacks on his disinterred (1869) poetry from the manuscript poems he had buried with his wife. He spent his last years as a withdrawn recluse.

On Easter Sunday, 1882, he died at the country house of a friend, where he'd gone in yet another vain attempt to recover his health, which had been destroyed by chloral as his wife's had been destroyed by laudanum. He is buried at Birchington-on-Sea, Kent, England. His grave is visited regularly by admirers of his life's work and achievements and this can be seen by fresh flowers placed there regularly.

Her lute hangs shadowed in the apple-tree,

While flashing fingers weave the sweet-strung spell

Between its chords; and as the wild notes swell,

The sea-bird for those branches leaves the sea.

But to what sound her listening ear stoops she?

What netherworld gulf-whispers doth she hear,

In answering echoes from what planisphere,

Along the wind, along the estuary?

She sinks into her spell: and when full soon

Her lips move and she soars into her song,

What creatures of the midmost main shall throng

In furrowed self-clouds to the summoning rune,

Till he, the fated mariner, hears her cry,

And up her rock, bare breasted, comes to die?

D. G. Rossetti

Mystery: lo! betwixt the sun and moon

Astarte of the Syrians: Venus Queen

Ere Aphrodite was. In silver sheen

Her twofold girdle clasps the infinite boon

Of bliss whereof the heaven and earth commune:

And from her neck's inclining flower-stem lean

Love-freighted lips and absolute eyes that wean

The pulse of hearts to the spheres' dominant tune.

Torch-bearing, her sweet ministers compel

All thrones of light beyond the sky and sea

The witnesses of Beauty's face to be:

That face, of Love's all-penetrative spell

Amulet, talisman, and oracle,

Betwixt the sun and moon a mystery.

D. G. Rossetti

_1863_73.jpg)

In royal wise ring-girt and bracelet-spann'd

A flower of Venus' own virginity,

Go shine among thy sisterly sweet band;

In maiden-minded converse delicately

Evermore white and soft; until thou be,

O hand! heart-handsel'd in a lover's hand.

D. G. Rossetti

Love's pallor and the semblance of deep ruth

Were never yet shown forth so perfectly

In any lady's face, chancing to see

Grief's miserable countenance uncouth,

As in thine, lady, they have sprung to soothe,

When in mine anguish thou hast lookd on me;

Until sometimes it seems as if, through thee,

My heart might almost wander from its truth.

Yet so it is, I cannot hold mine eyes

From gazing very often upon thine.

In the sore hope to shed those tears they keep;

And at such time, thou mask'st the pent tears rise

Even to the brim, till the eyes wast and pine;

Yet cannot they, while thou art present, weep.

D. G. Rossetti

Afar away the light that brings cold cheer

Unto this wall, - one instant and no more

Admitted at my distant palace-door

Afar the flowers of Enna from this drear

Dire fruit, which, tasted once, must thrall me here.

Afar those skies from this Tartarean grey

That chills me: and afar how far away,

The nights that shall become the days that were.

Afar from mine own self I seem, and wing

Strange ways in thought, and listenfor a sign:

And still some heart unto some soul doth pine,

O, Whose sounds mine inner sense in fain to bring,

Continually together murmuring)

'Woe me for thee, unhappy Proserpine'.

D. G. Rossetti

Rossetti himself said this of her:

"It seems hard to me when I look at her sometimes, working or too ill to work, and think how many without one tithe of her genius or greatness of spirit have granted them abundant health and opportunity to labor through the little they can do or will do, while perhaps her soul is never to bloom nor her bright hair to fade, but after hardly escaping from degradation and corruption, all she might have been must sink out again unprofitably in that dark house where she was born. How truly she may say,'No man cared for my soul.' I do not mean to make myself an exception, for how long have I known her, and not thought of this till late - perhaps too late. But it is of no use writing more about this subject; and I fear, too, my writing at all about it must prevent your easily believing it to be, as it is, by far the nearest thing to my own heart."

Andromeda, by Perseus sav'd and wed,

Hanker'd each day to see the Gorgon's head:

Till o'er a fount he held it, bade her lean,

And mirror'd in the wave was safely seen

That death she liv'd by.

Let not thine eyes know

Any forbidden thing itself, although

It once should save as well as kill: but be

Its shadow upon life enough for thee.

D. G. Rossetti

What smouldering senses in death's sick delay

Or seizure of malign vicissitude

Can rob this body of honour, or denude

This soul of wedding-raiment worn to-day?

For lo! even now my lady's lips did play

With these my lips such consonant interlude

As laurelled Orpheus longed for when he wooed

The half-drawn hungering face with that last lay.

I was a child beneath her touch,--a man

When breast to breast we clung, even I and she,

A spirit when her spirit looked through me,

A god when all our life-breath met to fan

Our life-blood, till love's emulous ardours ran,

Fire within fire, desire in deity.

D. G. Rossetti

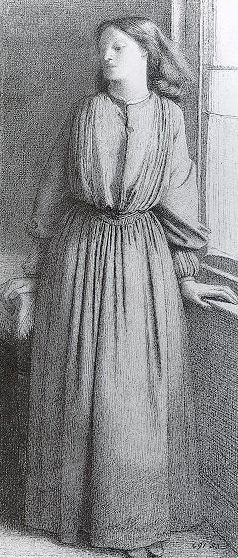

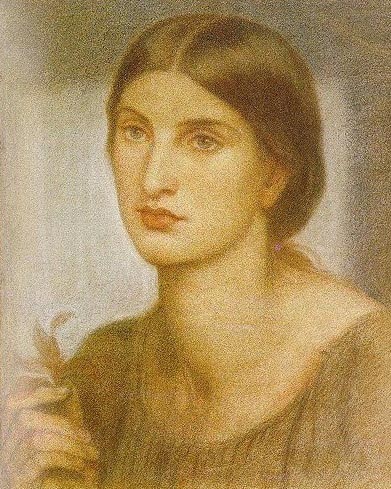

May Morris was an English craftswoman and designer. She was the daughter of the Pre-Raphaelite artist and designer William Morris and artists' model Jane Burden Morris.

May Morris was an influential embroideress and designer, although her contributions are often overshadowed by those of her father, a towering figure in the Arts and Crafts movement. May learned to embroider from her mother and her aunt Bessie Burden, who had been taught by William Morris. Morris himself is credited with the resurrection of free-form embroidery in the style which would be termed art needlework. Art needlework emphasized freehand stitching and delicate shading in silk thread, and was thought to encourage self-expression in the needle worker; this contrasted sharply with the brightly colored Berlin wool work needlepoint and its "paint by numbers" aesthetic which had gripped much of home embroidery in the mid-nineteenth century.

May Morris was active in the Royal School of Art Needlework (now Royal School of Needlework), founded as a charity in 1872 under the patronage of Princess Helena to maintain and develop the art of needlework through structured apprenticeships.

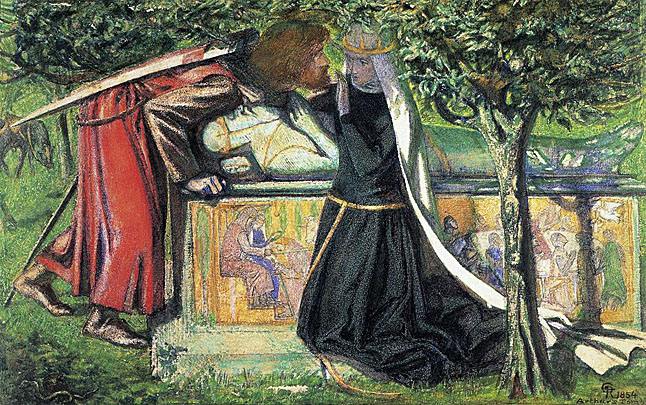

One day, to pass the time away, we read

of Lancelot- how love had overcome him.

We were alone, and we suspected nothing.

And time and time again that reading led

our eyes to meet, and made our faces pale,

and yet one point alone defeated us.

When we had read how the desired smile

was kissed by one who was so true a lover,

this one, who never shall be parted from me,

while all his body trembled, kissed my mouth.

A Gallehault indeed, that book and he

who wrote it, too; that day we read no more."

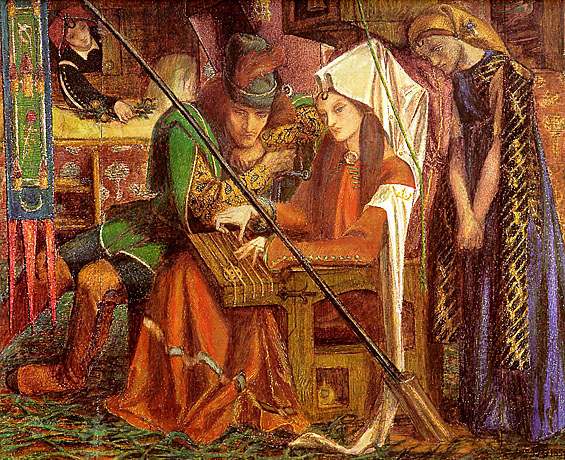

Inscribed at the foot of the left frame: "quanti dolci pensier, quanto disio"; at the foot of the right frame: "menò costoro al doloroso passo!"; at the top of central frame: "O lasso!" (Dante, InfernoV.114-116.

Quando rispuosi, cominciai: "Oh lasso,

quanti dolci pensier, quanto disio

menò costoro al doloroso passo!"

When I replied, my words began: "Alas,

how many gentle thoughts, how deep a longing,

had led them to the agonizing pass!"

_1870.jpg)

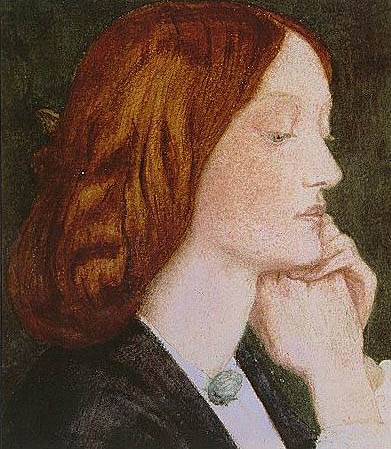

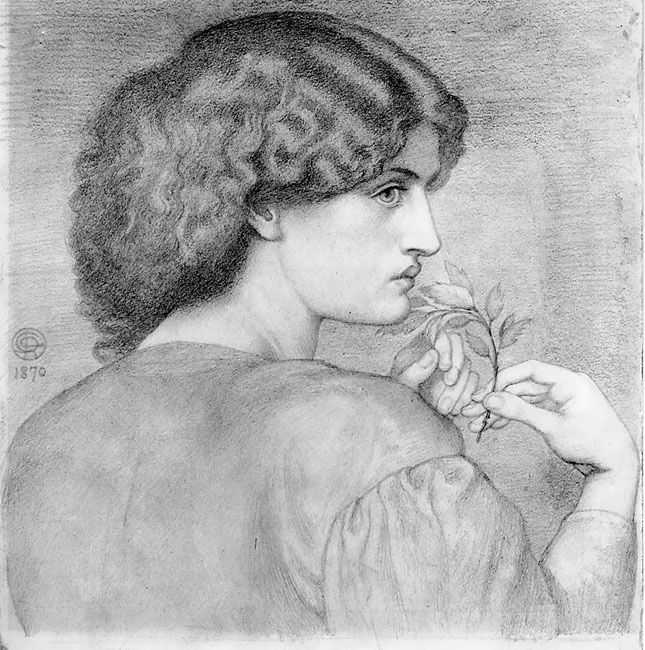

Elizabeth Eleanor Siddal was a British artist's model, poet and artist who was painted and drawn extensively by artists of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.

Siddal was perhaps the most important model to sit for the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Their ideas about feminine beauty were profoundly influenced by her, or rather she personified those ideals. She was Dante Gabriel Rossetti's model par excellence; almost all of his early paintings of women are portraits of her. She was also painted by Walter Deverell, William Holman Hunt, and John Everett Millais, and was the model for Millais' well known Ophelia (1852).

After becoming engaged to Rossetti, Siddal began to study with him. In contrast to Rossetti's idealized paintings, Siddal's were harsh. This is very evident in her self portrait, pictured above. Rossetti painted and repainted her and drew countless sketches of her. His depictions show a beauty. Her self portrait shows much about the subject, but certainly not the floating beauty that Rossetti painted. This painting is historically very significant because it shows, through her own eyes, a beauty who was idealized by so many famous artists. In 1855 the art critic John Ruskin began to subsidize her career. Ruskin paid a generous yearly stipend in exchange for all drawings and paintings that she produced. Siddal produced many sketches but only a single painting. Her sketches are laid out in a fashion similar to Pre-Raphaelite compositions and tend to illustrate Arthurian legend and other idealized Medieval themes. Ruskin also admonished Rossetti in his letters for not marrying Siddal and giving her the security she needed. During this period Siddal also began to write poetry, often with dark themes about lost love or the impossibility of true love. "Her verses were as simple and moving as ancient ballads; her drawings were as genuine in their medieval spirit as much more highly finished and competent works of Pre-Raphaelite art," wrote critic William Gaunt in The Pre-Raphaelite Dream.

As Siddal came from a lower class family, Rossetti feared introducing her to his parents. "Lizzy" was also the victim of harsh criticism from Rossetti's sisters. The knowledge that the family would not approve the wedding contributed to Rossetti putting it off. Siddal also appears to have believed, with some justification that Rossetti was always seeking to replace her with a younger muse, which contributed to her later depressive periods and illness.

Siddal travelled to Paris and Nice for several years for her health. She returned to England in 1860 to marry Rossetti. In the previous ten years he had been engaged to her and then broken it off at the last minute several times. Stress from those incidents had affected her. She was now severely depressed and her long illness had given her access to and addiction to laudanum. In 1861, Siddal became pregnant. She was overjoyed about this, but the pregnancy ended in a stillborn daughter. Siddal overdosed on laudanum shortly after becoming pregnant for a second time. Rossetti discovered her unconscious and dying in bed. Although her death was ruled accidental by the coroner, there are suggestions that Rossetti found a suicide note. Consumed with grief and guilt Rossetti went to see Ford Madox Brown who is supposed to have instructed him to burn the note - under the law at the time suicide was both illegal and immoral and would have brought a scandal on the family as well as barred Siddal from a Christian burial.

To touch the glove upon her tender hand,

To watch the jewel sparkle in her ring,

Lifted my heart into a sudden song

As when the wild birds sing.

To touch her shadow on the sunny grass,

To break her pathway through the darkened wood,

Filled all my life with trembling and tears

And silence where I stood.

I watch the shadows gather round my heart,

I live to know that she is gone

Gone gone for ever, like the tender dove

That left the Ark alone.

Early Death

Oh grieve not with thy bitter tears

The life that passes fast;

The gates of heaven will open wide

And take me in at last.

Then sit down meekly at my side

And watch my young life flee;

Then solemn peace of holy death

Come quickly unto thee.

But true love, seek me in the throng

Of spirits floating past,

And I will take thee by the hands

And know thee mine at last.

Ope not thy lips, thou foolish one,

Nor turn to me thy face;

The blasts of heaven shall strike thee down

Ere I will give thee grace.

Take thou thy shadow from my path,

Nor turn to me and pray;

The wild wild winds thy dirge may sing

Ere I will bid thee stay.

Turn thou away thy false dark eyes,

Nor gaze upon my face;

Great love I bore thee: now great hate

Sits grimly in its place.

All changes pass me like a dream,

I neither sing nor pray;

And thou art like the poisonous tree

That stole my life away.

Ford Madox Brown was an English painter of moral and historical subjects, notable for his distinctively graphic and often Hogarthian version of the Pre-Raphaelite style. While he was closely associated with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, he was never actually a member. Nevertheless, he remained close to Dante Gabriel Rossetti, with whom he also joined William Morris's design company, Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co., in 1861.

One of his most famous images is The Last of England, a portrait of a pair of stricken emigrants as they sail away on the ship that will take them from England forever. It was inspired by the departure of the Pre-Raphaelite sculptor Thomas Woolner, who had left for Australia. The painting is structured with Brown's characteristic linear energy, and emphasis on apparently grotesque and banal details, such as the cabbages hanging from the ship's side

Brown's most important painting was Work (1852-1865), which he showed at a special exhibition. It attempted to depict the totality of the mid-Victorian social experience in a single image, depicting 'navvies' digging up a road, Heath Street in Hampstead, London, and disrupting the old social hierarchies as they did so. The image erupts into proliferating details from the dynamic centre of the action, as the workers tear a hole in the road - and, symbolically, in the social fabric. Each character represents a particular social class and role in the modern urban environment. Brown wrote a catalogue to accompany the special exhibition of Work. This publication included an extensive explanation of Work that nevertheless leaves many questions unanswered.

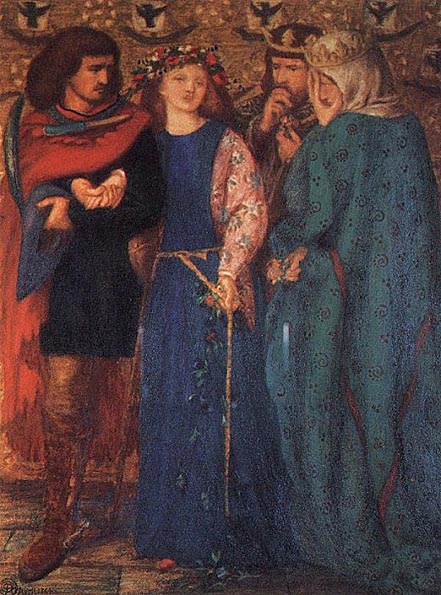

Romeo and Juliet in the famous balcony scene. Brown's major achievement after Work was the "Manchester Murals", a cycle of twelve paintings in the Great Hall of Manchester Town Hall depicting the history of the city. These present a partly ironic and satirical view of Mancunian history.

His son Oliver Madox Brown (1855-1874) showed promise both as an artist and poet, but died of blood-poisoning.

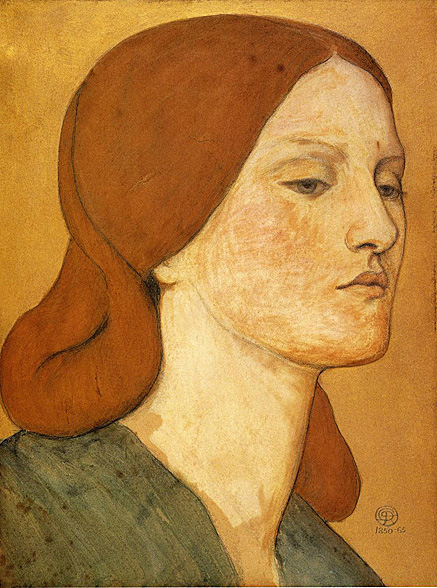

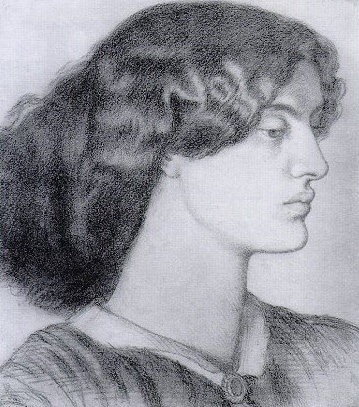

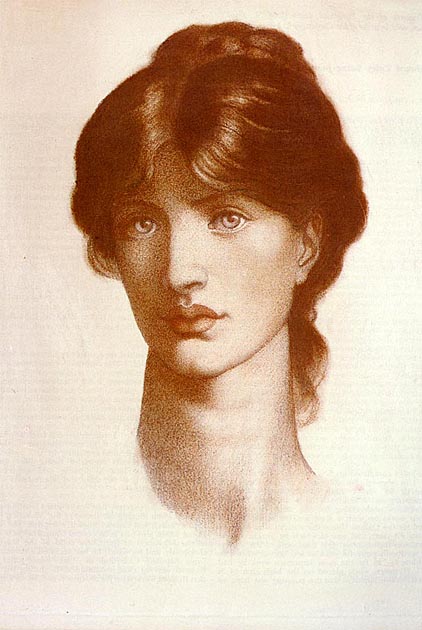

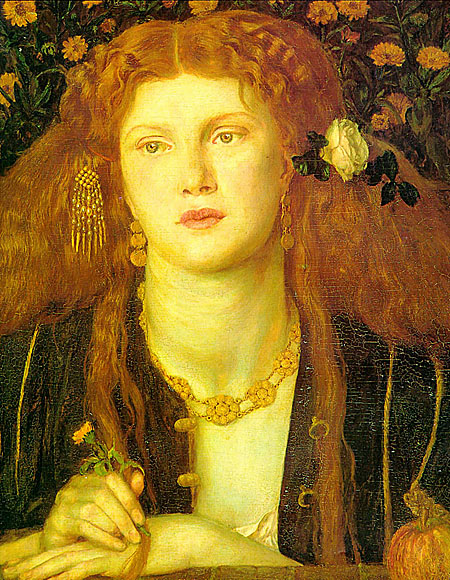

Jane Burden was the embodiment of the Pre-Raphaelite ideal of beauty. She became the wife of William Morris and the inspiration, and possibly mistress, of Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

She was born in Oxford. At the time of her birth, her father, Robert Burden, was a stableman and lived with his wife (Jane's mother), Ann Burden (formerly Maizey) at St. Helen's Passage, St Peter in the East, off Holywell Street in Oxford, marked with a blue plaque. Jane's mother, who was illiterate, probably came to Oxford as a domestic servant. Little is known about Jane's childhood but it was clearly one of poverty and deprivation.

In October 1857, Jane and her sister Elizabeth (known in the family as Bessie) were attending a performance in Oxford of the Drury Lane Theatre Company. Jane was noticed by the artists Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Edward Burne-Jones who were part of a group of artists painting murals in the Oxford Union based on Arthurian tales. Struck by Jane's beauty, they sought her to model for them. Jane initially sat mainly for Rossetti, who needed a model for Queen Guinivere. After this, Jane sat to Morris, who was working on an easel painting, La Belle Iseult (Tate Gallery). Like Rossetti, Morris also used Jane as his model for his rendition of Queen Guinevere. During this period, Morris fell in love with Jane and they were engaged.

Jane's education was extremely limited and she was probably intended to go into domestic service. After her engagement, Jane was privately educated. Her keen intelligence allowed her essentially to re-create herself. She was a voracious reader and became proficient in French and later Italian. She also became an accomplished pianist with a strong background in classical music. Her manners and speech became refined to an extent that contemporaries referred to her as "Queenly". Later in life, she would have no trouble moving in upper class circles and she appears to have been the model for Mrs Higgins in Bernard Shaw's play Pygmalion (1914).

She married William Morris at St Michael's Church, Oxford, on April 26, 1859. Her father was at that time described as a groom, in stables at 65 Holywell Street, Oxford.

Jane Burden and William Morris lived firstly at the Red House in Bexleyheath, Kent. While there, they had two daughters, Jane Alice (Jenny), born January 1861, and Mary (May) (March 1862 - 1938), who was the editor of her father's works. They then lived for many years at Kelmscott Manor, on the Gloucestershire-Oxfordshire-Wiltshire borders, which is now open to the public.

During this time, Jane became closely attached to Dante Gabriel Rossetti and, in addition to being his muse, may have been his lover.

In 1884, Jane met the poet and political activist Wilfrid Scawen Blunt at a house party given by her close friend Rosalind Howard (later Countess of Carlisle). There appears to have been an immediate attraction between the two. By 1887 at the latest, the pair had become lovers. Their sexual relationship would continue until 1894, and they remained close friends until Jane's death.

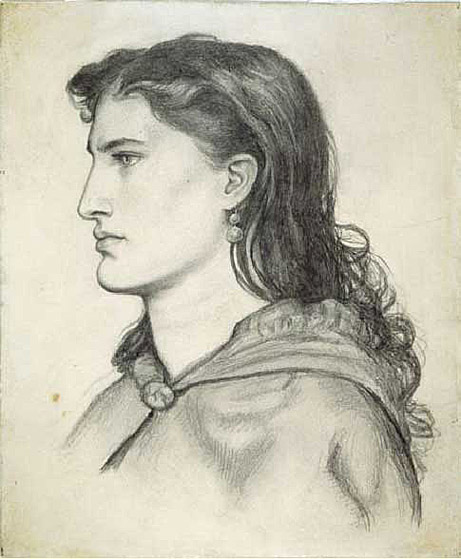

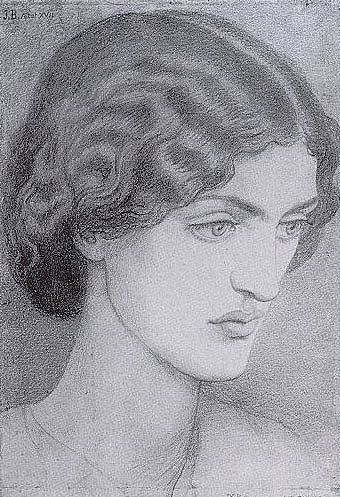

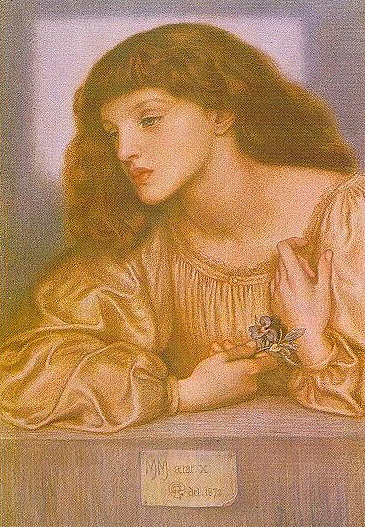

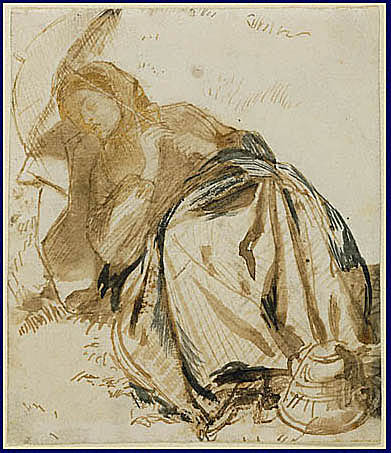

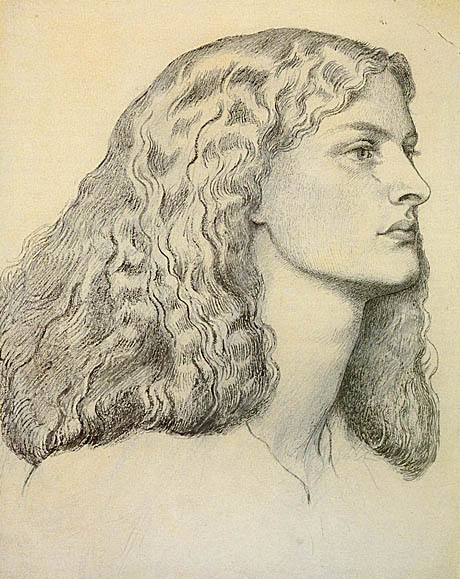

This wedding portrait was made soon after Rossetti's marriage to Elizabeth Eleanor "Lizzie" Siddal, in May 1860 and is an image of the final, tragic stage of that great love affair. In marrying her in 1860, Rossetti was probably motivated more by compassion and duty than a revival of their old great love and the events following the production of the drawing suggest that it was a genuine attempt to recreate a feeling that was slowly slipping away. Certainly this drawing has a greater directness and intensity than the oil painting that derives from it. As Virginia Surtees observes the '...likeness to the sitter is closer.'

The drawing almost certainly predates the painting, which was complete by the end of 1860, when George Price Boyce recorded in his diary for December 14th that Rossetti had 'painted a fine head of his wife as "Regina Cordium."' This reference and the date on the painting emphasize that it was completed in 1860 and not 1861. It was underway in the Summer, when Rossetti wrote to Ford Madox Brown: 'Lizzie is here now, and I am painting her as the Queen of Hearts.' Several facts suggest the earlier date of the drawing which must come from the first months of Rossetti's marriage. There is the closer likeness to the sitter which has already been mentioned. The drawing is simpler, omitting the parapet which distances us from the sitter in the painting. Finally, in the drawing Lizzie carries a conventionalized flower, rather than the symbolic pansy or heartease which she carries in the final painting. This last detail in particular would almost certainly have been transferred to a drawing that postdated the painting. However the degree of finish of the drawing, its decorative signature within a heart shaped medallion and the fact that it passed out of Rossetti's possession in his lifetime all show that it was conceived as a work of art in its own right and not merely as a study for the painting.

The probable first owner of this drawing, Val Prinsep, was very close to Rossetti at the time of his marriage. He is almost the only person to have left a record of the tensions that marred it. Although he believed that Rossetti remained faithful to Lizzie, he observed her destructive jealousy of him: 'She threw studies of "stunners" out of the window and they floated down the Thames and were lost.' Certainly Rossetti continued to use Fanny Cornforth, his mistress, as a model during the period of his marriage. The present drawing could even be seen as a very ambivalent tribute to Elizabeth Siddal, for Rossetti has represented her with the sensuality and flowing hair he first used in pictures of Fanny. The 'Regina Cordium' image, which must have been a comfort to Lizzie at the beginning of the marriage, probably contributed to her self-destructive unhappiness at its end. In November 1861, some three months before Lizzie's presumed suicide, Rossetti painted another woman, Mrs. Heaton, wife of a patron, as 'Regina Cordium' in exactly the same format as the drawing and painting of Lizzie. It is not that he was in love with Mrs. Heaton, but rather that the re-use of the image seems to undermine its value as a statement of love for his wife.

Your hands lie open in the long fresh grass,

The finger-points look through, like rosy blooms:

Your eyes smile peace. The pasture gleams and glooms

'Neath billowing skies that scatter and amass.

All round our nest far, as the eye can pass

Are golden kingcup fields with silver edge

Where the cow-parsley skirts the hawthorn-hedge

'Tis visible silence, still as the hour-glass.

Deep in the sun searched groves, a dragon-fly

Hangs, like a blue thread loosened from the sky:

So this winged hour is dropt to us from above.

Oh! clasp we to our hearts, for deathless dower

This close-companioned inarticulate hour

When twofold silence was the song of love.

D. G. Rossetti

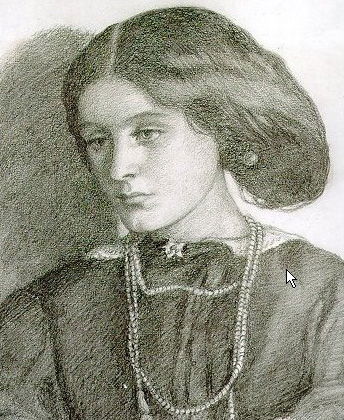

In 1854, William Holman Hunt embarked on a trip to the Holy Land, leaving his fiancée Annie Miller in London. He had discovered her working as a barmaid in a Chelsea slum. Hunt had seen in her his ideal of Pre-Raphaelite beauty and had 'rescued' her with the intention of molding her into a lady to be his wife. Before leaving he had issued strict instructions to her that she should not model for any of his artist friends (especially Rossetti). George Price Boyce had met Hunt the previous year in the studio of his good friend, Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Despite describing Hunt as a thoroughly genuine, humorous, good-hearted, straightforward English like fellow, Boyce ignored his wishes and characteristically, succumbed to Annie's will to model for him and to have a good time. Boyce was renowned for his weakness for female beauty and this delicate drawing of Annie as a young girl, made shortly after Hunt's departure for Syria, is a result of this forbidden liaison. In January 1858 Hunt requested and then insistently demanded Boyce's 1854 Portrait of Annie Miller.

After Hunt's return and his break from Annie in 1860, Boyce and Rossetti began to fiercely battle for sittings with her; Rossetti being the consistent winner in this competition. In Boyce's diary of 1860, we see that his appointments with Annie were constantly usurped. He notes on several occasions how Rossetti would interrupt his sittings with her, even to the point of taking her away. In one taunting note from his competitor, Rossetti jeers: Dear Boyce, Blow you, Annie is coming to me tomorrow. I'm sure you won't mind, like a good chap. No wonder Rossetti's wife, Lizzie Siddal, became jealous and threw his drawings of Annie out the window.

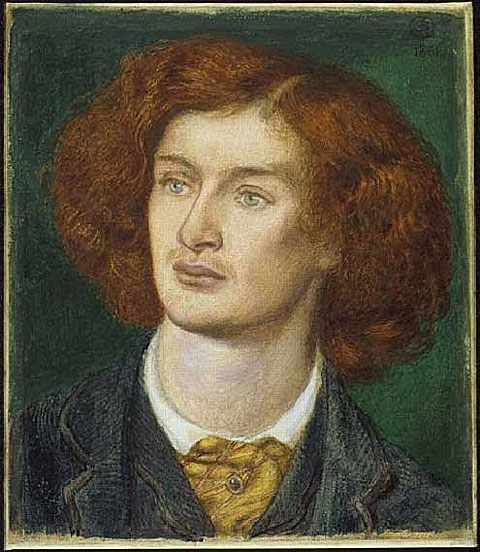

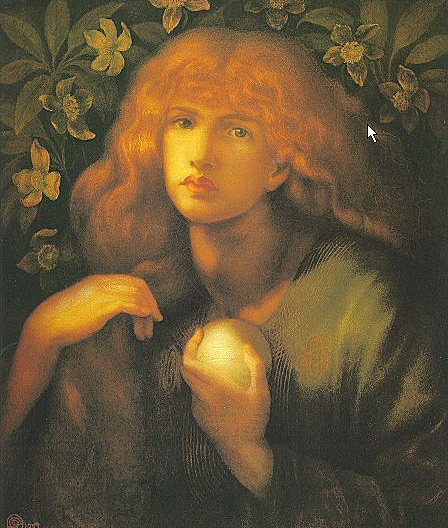

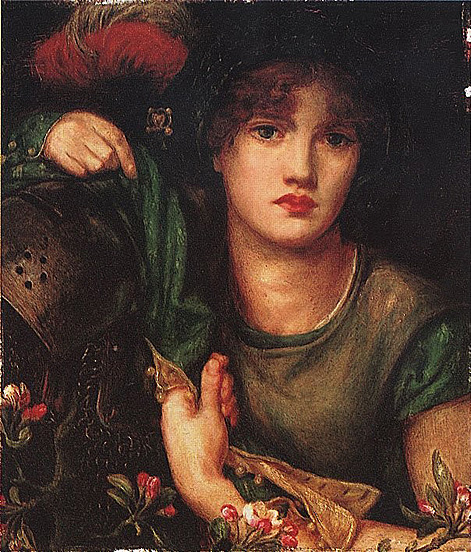

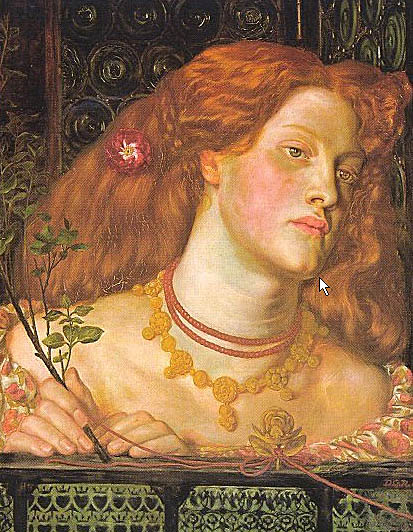

Fanny Cornforth was born in Sussex in 1824. She seems to have moved to London as a small child with her family. She met Rossetti in about 1857. Legend has it that the painter was walking along The Strand one evening, when his attention was attracted by a young woman noisily misbehaving herself-in fact she was cracking nuts with her teeth. On noticing that Rossetti was watching her, Fanny started throwing the nutshells at him. He was intrigued and amused by this behaviour, and straightaway decided to use her as a model.

The situation of working class women unprotected by a family was very difficult at that time. The only real opportunity open to them was to work as domestic servants, which involved long hours, very low wages, and a virtually total loss of personal freedom. The result of this was an army of young women in London working as, and around the edges of prostitution. Quite often these women did not sleep with men on a regular basis, frequency being dictated by financial necessity. Such a young woman was Fanny Cornforth. It is quite wrong to simply describe these women baldly as prostitutes-collectively they were known as ‘dolly mops.’

At this time the relationship of Rossetti and Lizzie Siddal had cooled down from its former exclusive intensity, and Fanny was quickly installed in his house at Cheyne Walk as his mistress cum housekeeper. This relationship did not meet the approval of many of the painter’s friends. Fanny was noisy, hearty, earthy, and spoke in a broad cockney dialect. It is notable that Rossetti’s brother William, who quite obviously knew her well, did not mention Fanny in any of his copious writings about his famous brother, yet photographic evidence confirms they knew each other, and suggests they were on good terms. It would be wrong to assume, however that this hostility was shared by all his friends. She was on good terms with Swinburne, and George Price Boyce the painter was a great admirer of hers. He described her as having an ’interesting face, and an engaging disposition.’

In 1860 Rossetti became involved again with Lizzie Sidal, who was now seriously ill, and in May that year he married her. Fanny Cornforth was deeply offended, and was described at the time as frantic. Shortly after this she married one Timothy Hughes. On the night of February 10th 1862 the unhappy, sick, tragic Lizzie committed suicide, shortly following a full-term pregnancy, and a stillborn baby. Some time after this the relationship between Fanny Cornforth and the painter resumed, incidentally her new husband had also died.

The cheerful, uncomplicated, earthy cockney girl was a great comfort to the guilt-ridden and seriously disturbed Rossetti at this time, which also marked the zenith of their relationship. This was also the time when Fanny became his major model and muse. Her personality also influenced the direction of Rossetti’s art at this time, as not even he could make her fascinating, and ethereal in a claustrophobic background. His paintings of Fanny Cornforth were more literal than anything else he produced, and showed a woman who was sensual, and had a highly suspect past. Rossetti’s many drawings and paintings of Fanny at this time usually refer, in the iconography he used, to that past, and they show as a her rather coarse, and very sexual beauty.

In about 1867 Rossetti’s obsession with Jane Morris gradually became the greatest factor in his life, both personally and artistically, and Fanny Cornforth’s role seems to have become mainly as his housekeeper. I think it reasonable to assume that her cheerful presence still exerted a positive influence in his increasingly disturbed and addicted life.

In 1879 Fanny Cornforth finally left Rosssetti to marry one John Schott, and she seems to have helped herself to some of his minor possessions and drawings at this time-I would imagine he accepted this in a wry and humorous manner. There is little evidence that he tried to reclaim any of his belongings from her. Fanny Cornforth and her husband became fairly successful publicans, running an inn in London. She died in 1906 aged eighty- two years.

Of Adam's first wife, Lilith, it is told

(The witch he loved before the gift of Eve.)

That, ere the snake's, her sweet tongue could deceive,

And still her enchanted hair was the first gold.

And still she sits, young while the earth is old,

And, subtly of herself contemplative,

Draws men to watch the bright web she can weave,

Till heart and body and life are in its hold.

The rose and poppy are her flowers; for where

Is he not found, O Lilith, whom shed scent

And soft-shed kisses and soft sleep shall snare?

Lo! as that youth's eyes burned at thine, so went

Thy spell through him, and left his straight neck bent,

And round his heart one strangling golden hair.

D. G. Rossetti

Rossetti inscribed the line on the reverse side of the canvas in its original translation: Bocca baciate non perda ventura, anzi rinnova come fa la luna.

How Sir Lancelot was espied in the queen's chamber, and how Sir Agravaine and Sir Mordred came with twelve knights to slay him.

SO Sir Lancelot departed, and took his sword under his arm, and so in his mantle that noble knight put himself in great Jeopardy; and so he passed till he came to the queen's chamber, and then Sir Lancelot was lightly put into the chamber. And then, as the French book says, the queen and Lancelot were together. And whether they were abed or at other manner of disports, me list not hereof make no mention, for love that time was not as is now-a-days. But thus as they were together, there came Sir Agravaine and Sir Mordred, with twelve knights with them of the Round Table, and they said with crying voice: Traitor-knight, Sir Lancelot du Lake, now art thou taken. And thus they cried with a loud voice, that all the court might hear it; and they all fourteen were armed at all points as they should fight in a battle. Alas said Queen Guinevere, now are we are compromised both Madam, said Sir Lancelot, is there here any armor within your chamber, that I might cover my poor body withal? And if there be any give it me, and I shall soon stint their malice, by the grace of God. Truly, said the queen, I have none armor, shield, sword, nor spear; wherefore I dread me sore our long love is come to a mischievous end, for I hear by their noise there be many noble knights, and well I wot they be surely armed, and against them ye may make no resistance. Wherefore ye are likely to be slain, and then shall I be brent. For an ye might escape them, said the queen, I would not doubt but that ye would rescue me in what danger that ever I stood in. Alas, said Sir Lancelot, in all my life thus was I never bestead, that I should be thus shamefully slain for lack of mine armor.

But ever in one Sir Agravaine and Sir Mordred cried: Traitor-knight, come out of the queen's chamber, for wit thou well thou art so beset that thou shalt not escape. O Jesu mercy, said Sir Lancelot, this shameful cry and noise I may not suffer, for better were death at once than thus to endure this pain. Then he took the queen in his arms, and kissed her, and said: Most noble Christian queen, I beseech you as ye have been ever my special good lady, and I at all times your true poor knight unto my power, and as I never failed you in right nor in wrong sithen the first day King Arthur made me knight, that ye will pray for my soul if that I here be slain; for well I am assured that Sir Bors, my nephew, and all the remnant of my kin, with Sir Lavaine and Sir Urre, that they will not fail you to rescue you from the fire; and therefore, mine own lady, recomfort yourself, whatsoever come of me, that ye go with Sir Bors, my nephew, and Sir Urre, and they all will do you all the pleasure that they can or may, that ye shall live like a queen upon my lands. Nay, Lancelot, said the queen, wit thou well I will never live after thy days, but an thou be slain I will take my death as meekly for Jesu Christ's sake as ever did any Christian queen. Well, madam, said I-Lancelot, says it is so that the day is come that our love must depart, wit you well I shall sell my life as dear as I may; and a thousand fold, said Sir Lancelot, I am more heavier for you than for myself. And now I had liefer than to be lord of all Christendom, that I had sure armor upon me, that men might speak of my deeds or ever I were slain. Truly, said the queen, I would an it might please God that they would take me and slay me, and suffer you to escape. That shall never be, said Sir Lancelot, God defend me from such a shame, but Jesu be Thou my shield and mine armor!

She hath the apple in her hand for thee,

Yet almost in her heart would hold it back;

She muses, with her eyes upon the track

Of that which in thy spirit they can see.

Haply, "Behold, he is at peace," saith she;

"Alas! the apple for his lips, - the dart

That follows its brief sweetness to his heart,

The wandering of his feet perpetually!"

A little space her glance is still and coy,

But if she gives the fruit that works her spell,

Those eyes shall flame as for her Phrygian boy.

Then shall her bird's strained throat the woe foretell,

And her far seas moan as a single shell,

And through her dark grove strike the light of Troy.

D. G. Rossetti

Under the arch of life, where love and death,

Terror and mystery, guard her shrine, I saw

Beauty enthroned; and though her gaze struck awe,

I drew it in as simply as my breath.

Hers are the eyes which, over and beneath

The sky and sea bend on thee, - which can draw,

By sea or sky or woman, to one law,

The allotted bondman of her palm and wreath.

This is that Lady Beauty, in whose praise

Thy voice and hand shake still, - long known to thee

By flying hair and fluttering hem, - the beat

Following her daily of thy heart and feet,

How passionately and irretrievably,

In what fond flight, how many ways and days!

D. G. Rossetti

The blessed damozel leaned out

From the gold bar of Heaven;

Her eyes were deeper than the depth

Of waters stilled at even;

She had three lilies in her hand,

And the stars in her hair were seven.

Her robe, ungirt from clasp to hem,

No wrought flowers did adorn,

But a white rose of Mary's gift,

For service meetly worn;

Her hair that lay along her back

Was yellow like ripe corn.

Herseemed she scarce had been a day

One of God's choristers ...

D. G. Rossetti

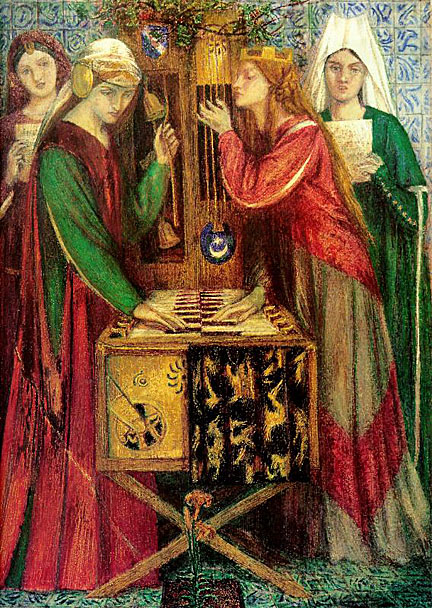

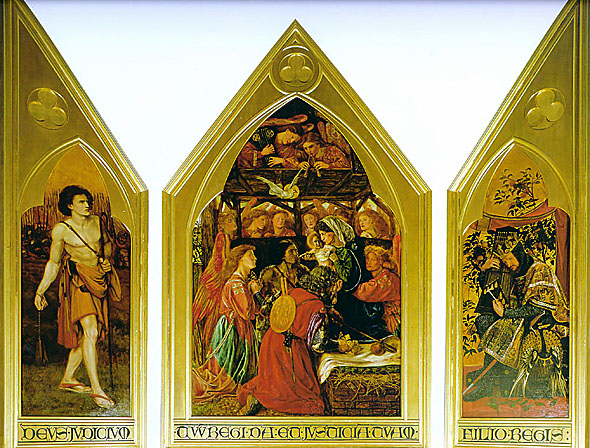

The subject has no apparent literary source; two women play upon a strange medieval instrument, which combines clavichord, carillon and harp. Behind the musicians stand two singers. The painting inspired Morris's poem of the same name, but, as Rossetti remarked, 'The poems were the result of the pictures, but don't at all tally to any purpose with them though beautiful in themselves.'

(From 'The Blue Closet', William Morris)

I.

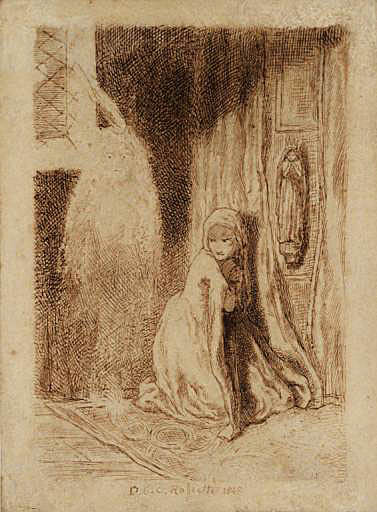

This is that blessed Mary, pre-elect,

God's Virgin. Gone is a great while, and she

Dwelt young in Nazareth of Galilee.

Unto God's will she brought devout respect,

Profound simplicity of intellect,

And supreme patience. From her mother's knee

Faithful and hopeful; wise in charity;

Strong in grave peace; in pity circumspect.

So held she through her girlhood; as it were

An angel-watered lily, that near God

Grows and is quiet. Till, one dawn at home,

She woke in her white bed, and had no fear

At all, -- yet wept till sunshine, and felt awed;

Because the fullness of the time was come.

II.

These are the symbols. On that cloth of red

I' the centre is the Tripoint: perfect each,

Except the centre of its points,to teach

That Christ is not yet born. The books -- whose head

Is golden Charity, as Paul hath said

Those virtues are wherein the soul is rich;

Therefore on them the lily standeth, which

Is innocence, being interpreted.

The seven-thorn'd brier and palm seven-leaved

Are here great sorrow and her great reward

Until the end be full, the Holy One

Abides without. She soon shall have achieved

Her perfect purity: yea, God the Lord

Shall soon vouchsafe His Son to be her Son.

D. G. Rossetti

Autumn Song

Know'st thou not at the fall of the leaf

How the heart feels a languid grief

Laid on it for a covering,

And how sleep seems a goodly thing

In Autumn at the fall of the leaf?

And how the swift beat of the brain

Falters because it is in vain,

In Autumn at the fall of the leaf

Knowest thou not? and how the chief

Of joys seems--not to suffer pain?

Know'st thou not at the fall of the leaf

How the soul feels like a dried sheaf

Bound up at length for harvesting,

And how death seems a comely thing

In Autumn at the fall of the leaf?

The Cloud Confines

The day is dark and the night

To him that would search their heart;

No lips of cloud that will part

Nor morning song in the light:

Only, gazing alone,

To him wild shadows are shown,

Deep under deep unknown

And height above unknown height.

Still we say as we go,

"Strange to think by the way,

Whatever there is to know,

That shall we know one day."

The Past is over and fled;

Nam'd new, we name it the old;

Thereof some tale hath been told,

But no word comes from the dead;

Whether at all they be,

Or whether as bond or free,

Or whether they too were we,

Or by what spell they have sped.

Still we say as we go,

"Strange to think by the way,

Whatever there is to know,

That shall we know one day."

What of the heart of hate

That beats in thy breast, O Time?

Red strife from the furthest prime,

And anguish of fierce debate;

War that shatters her slain,

And peace that grinds them as grain,

And eyes fix'd ever in vain

On the pitiless eyes of Fate.

Still we say as we go,

"Strange to think by the way,

Whatever there is to know,

That shall we know one day."

What of the heart of love

That bleeds in thy breast, O Man?

Thy kisses snatch'd 'neath the ban

Of fangs that mock them above;

Thy bells prolong'd unto knells,

Thy hope that a breath dispels,

Thy bitter forlorn farewells

And the empty echoes thereof?

Still we say as we go,

"Strange to think by the way,

Whatever there is to know,

That shall we know one day."

The sky leans dumb on the sea,

Aweary with all its wings;

And oh! the song the sea sings

Is dark everlastingly.

Our past is clean forgot,

Our present is and is not,

Our future's a seal'd seedplot,

And what betwixt them are we?

We who say as we go,

"Strange to think by the way,

Whatever there is to know,

That shall we know one day."

Insomnia

Thin are the night-skirts left behind

By daybreak hours that onward creep,

And thin, alas! the shred of sleep

That wavers with the spirit's wind:

But in half-dreams that shift and roll

And still remember and forget,

My soul this hour has drawn your soul

A little nearer yet.

Our lives, most dear, are never near,

Our thoughts are never far apart,

Though all that draws us heart to heart

Seems fainter now and now more clear.

To-night Love claims his full control,

And with desire and with regret

My soul this hour has drawn your soul

A little nearer yet.

Is there a home where heavy earth

Melts to bright air that breathes no pain,

Where water leaves no thirst again

And springing fire is Love's new birth?

If faith long bound to one true goal

May there at length its hope beget,

My soul that hour shall draw your soul

For ever nearer yet.

Love-Lily

Between the hands, between the brows,

Between the lips of Love-Lily,

A spirit is born whose birth endows

My blood with fire to burn through me;

Who breathes upon my gazing eyes,

Who laughs and murmurs in mine ear,

At whose least touch my colour flies,

And whom my life grows faint to hear.

Within the voice, within the heart,

Within the mind of Love-Lily,

A spirit is born who lifts apart

His tremulous wings and looks at me;

Who on my mouth his finger lays,

And shows, while whispering lutes confer,

That Eden of Love's watered ways

Whose winds and spirits worship her.

Brows, hands, and lips, heart, mind, and voice,

Kisses and words of Love-Lily,

Oh! bid me with your joy rejoice

Till riotous longing rest in me!

Ah! let not hope be still distraught,

But find in her its gracious goal,

Whose speech Truth knows not from her thought

Nor Love her body from her soul.

Source: Art Renewal Center

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.