1829- 1896

Millais was born in Southampton, England in 1829, of a prominent Jersey-based family. His prodigious artistic talent won him a place at the Royal Academy schools at the unprecedented age of eleven. While there, he met William Holman Hunt and Dante Gabriel Rossetti with whom he formed the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (Known as the 'PRB') in September 1848 in his family home on Gower Street, off Bedford Square.

Millais' Christ In The House of His Parents (1850) was highly controversial because of its realistic portrayal of a working class Holy Family laboring in a messy carpentry workshop. Later works were also controversial, though less so. Millais achieved popular success with A Huguenot (1852), which depicts a young couple about to be separated because of religious conflicts. He repeated this theme in many later works.

All these early works were painted with great attention to detail, often concentrating on the beauty and complexity of the natural world. In paintings such as Ophelia (1852) Millais created dense and elaborate pictorial surfaces based on the integration of naturalistic elements. This approach has been described as a kind of "pictorial eco-system".

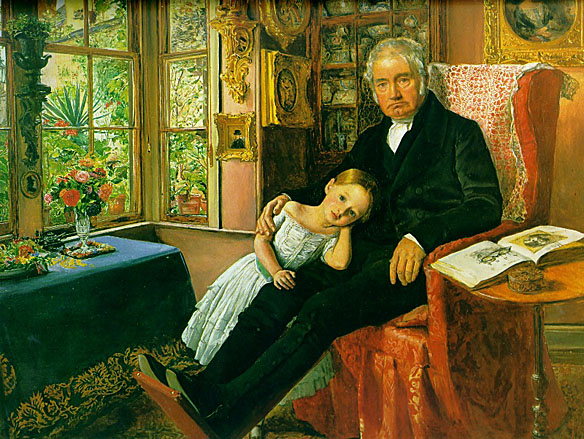

This style was promoted by the critic John Ruskin, who had defended the Pre-Raphaelites against their critics. Millais' friendship with Ruskin introduced him to Ruskin's wife Effie. Soon after they met she modeled for his painting The Order of Release. As Millais painted Effie they fell in love. Despite having been married to Ruskin for several years, Effie was still a virgin. Her parents realized something was wrong and she filed for an annulment. In 1856, after her marriage to Ruskin was annulled, Effie and John Millais married. He and Effie eventually had eight children.

After his marriage, Millais began to paint in a broader style, which was condemned by Ruskin as "a catastrophe". It has been argued that this change of style resulted from Millais' need to increase his output to support his growing family. Unsympathetic critics such as William Morris accused him of "selling out" to achieve popularity and wealth. His admirers, in contrast, pointed to the artist's connections with Whistler and Albert Moore, and influence on John Singer Sargent. Millais himself argued that as he grew more confident as an artist, he could paint with greater boldness. In his article "Thoughts on our art of Today" (1888) he recommended Velázquez and Rembrandt as models for artists to follow.

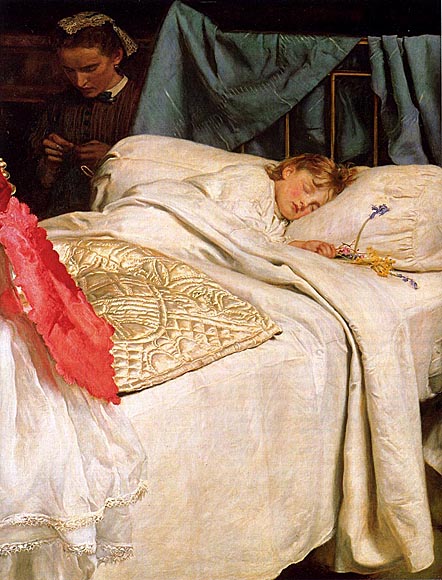

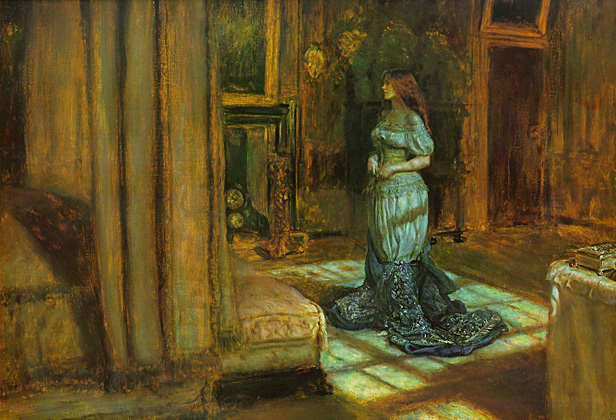

Paintings such as The Eve of St. Agnes and The Somnambulist clearly show an ongoing dialogue between the artist and Whistler, whose work Millais strongly supported. Other paintings of the late 1850s and 1860s can be interpreted as anticipating aspects of the Aesthetic Movement. Many deploy broad blocks of harmoniously arranged color and are symbolic rather than narrative.

Later works, from the 1870s onwards demonstrate Millais' reverence for old masters such as Joshua Reynolds and Velázquez. Many of these paintings were of an historical theme and were other examples of Millais' talent. Notable among these are The Two Princes Edward and Richard in the Tower (1878) depicting the Princes in the Tower, The Northwest Passage (1874) and the Boyhood of Raleigh (1871). Such paintings indicate Millais' interest in subjects connected to Britain's history and expanding empire.

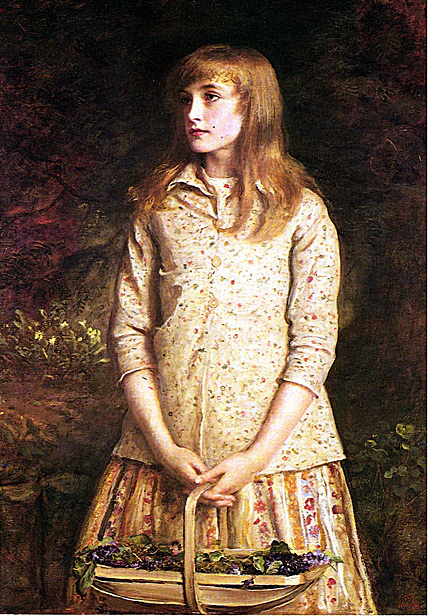

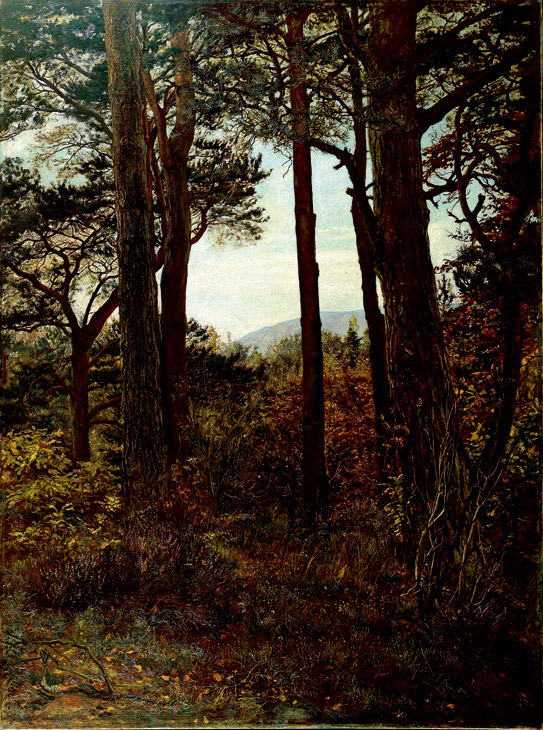

His last project was to be a painting depicting a white hunter lying dead in the African veldt, his body contemplated by two indifferent Africans. This fascination with wild and bleak locations is also evident in his many landscape paintings of this period, which usually depict difficult or dangerous terrain. The first of these, Chill October (1870) was painted in Perth, near his wife's family home. Many others were painted elsewhere in Perthshire, near Dunkeld and Birnam, where Millais rented grand houses each autumn in order to hunt and fish. Millais also achieved great popularity with his paintings of children, notably Bubbles (1886) - famous, or perhaps notorious, for being used in the advertising of Pears soap - and Cherry Ripe.

Millais was also very successful as a book illustrator, notably for the works of Anthony Trollope and the poems of Tennyson. His complex illustrations of the parables of Jesus were published in 1864. His father-in-law commissioned stained-glass windows based on them for Kinnoull parish church, Perth. He also provided illustrations for magazines such as Good Words. In 1869 he was recruited as an artist for the newly founded weekly newspaper The Graphic.

Millias was elected as an associate member of the Royal Academy of Arts in 1853, and was soon elected as a full member of the Academy, in which he was a prominent and active participant. He was granted a baronetcy in 1885, the first artist to be honored with a hereditary title. After the death of Frederic Leighton in 1896, Millais was elected President of the Royal Academy, but he died later in the same year from throat cancer. He was buried in St Paul's Cathedral.

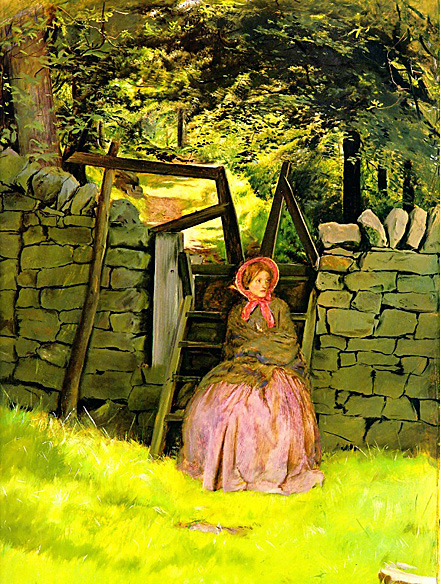

Cherry ripe, cherry ripe,

Ripe I cry,

Full and fair ones

Come and buy.

Cherry ripe, cherry ripe,

Ripe I cry,

Full and fair ones

Come and buy.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Although Millais visited Scotland primarily to take a break from the confines of the studio, by 1868 he was keen to depict the dramatic scenery he knew so well from scrambling over hills to stalk deer, or wading in rivers to fly-fish. In 1870 he completed Chill October, which set a new standard in landscape painting with their depictions of dramatic weather and melancholy mood the paintings convey his love for the beauty of the Scottish countryside. He said that 'there is more significance and feeling in one day of a Scotch autumn than in a whole half-year of spring and summer in Italy'.

Millais based the setting on a real carpenter's shop in Oxford Street. Symbols of the Crucifixion figure prominently: the wood, the nails, the cut in Christ's hand and the blood on his foot. Millais was viciously attacked by the press for showing the holy family as 'ordinary'.

Charles Dickens described Christ as 'a hideous, wry-necked, blubbering, red-haired boy in a night-gown.'

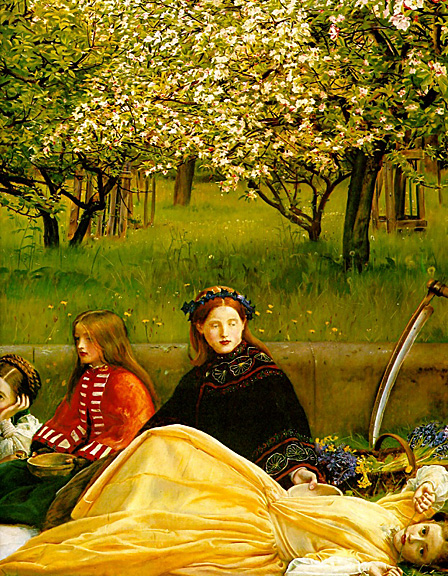

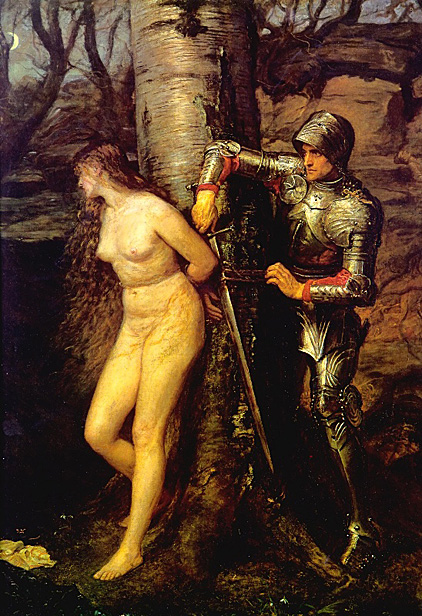

This bucolic rendering of the theme that has been treated with such dignity by Reynolds and Leighton, is conceived in the spirit of Etty and Frost. Cymon, a rollicking rustic, newly-awakened to the charms of womanhood, is leading the fair maid - little "asham'd of such a guide" - in a riotous dance. Ford Madox Brown declared that Etty "taught Millais and all our school to color," but added that Millais and, in a minor degree, Mr. Holman Hunt, were the only ones who sought, and found out, his secret. The composition, arrangement of figures, color, and general design, make this picture an unusually creditable performance for a youth who had just left the schools. Clearly based on Etty - especially in the painting of flesh - it was begun in 1848 and then put on one side when the young artist, converted to Pre-Raphaelitism, threw his energies into the Lorenzo and Isabella. In 1851 he took Cymon up again, and completed the foreground flowers and growth with as much Pre-Raphaelite precision as the picture would bear; but not caring, no doubt, to exhibit it, he sent it to Christie's, where, in 1853, it was sold by auction. The humor in the vacant eyes and grinning face of Cymon is quite in the tradition of the Leslie School.

The story of Cimon (or Cymon) and Iphigenia was originally told in The Decameron of Boccaccio. Millais's source, though, was the version by the 17th century English poet John Dryden. The poem described the love of the aristocratic but boorish Cymon, who had been banished by his family to live in the country as a rustic, for the distant and refined Iphigenia.

Millais was only 18 when he began the painting, and it was the last major canvas he worked on before he embraced Pre-Raphaelitism with his friends Holman Hunt and Rossetti. Hunt assisted him with Iphigenia's dress but Millais was already dissatisfied with the picture and vowing he could do something much better. The outcome was 'Isabella', now in the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool.

Euphemia ('Effie') Chalmers Gray was the wife of the critic John Ruskin, but later left her husband to marry his protégé, the Pre-Raphaelite painter John Everett Millais. This famous Victorian "love triangle" has been dramatized in several plays and an opera.

Effie was born in Perth, Scotland and lived in Bowerswell, the house where Ruskin's grandfather had committed suicide. Her family knew Ruskin's father, who encouraged a match between them. In 1842, Ruskin wrote the fantasy novel The King of the Golden River for Effie. After their marriage, they travelled to Venice where Ruskin was researching his book The Stones of Venice. However, their different temperaments soon caused problems, with Effie coming to feel oppressed by Ruskin's dogmatic personality.

When she met Millais five years later, Effie was still a virgin, as Ruskin had persistently put off consummating the marriage. His reasons are unclear, but they involved disgust with some aspect of her body. As Effie later wrote to her father, "He alleged various reasons, hatred to children, religious motives, a desire to preserve my beauty, and, finally this last year he told me his true reason... that he had imagined women were quite different to what he saw I was, and that the reason he did not make me his Wife was because he was disgusted with my person the first evening 10th April." Ruskin confirmed this in his statement to his lawyer during the annulment proceedings. "It may be thought strange that I could abstain from a woman who to most people was so attractive. But though her face was beautiful, her person was not formed to excite passion. On the contrary, there were certain circumstances in her person which completely checked it."

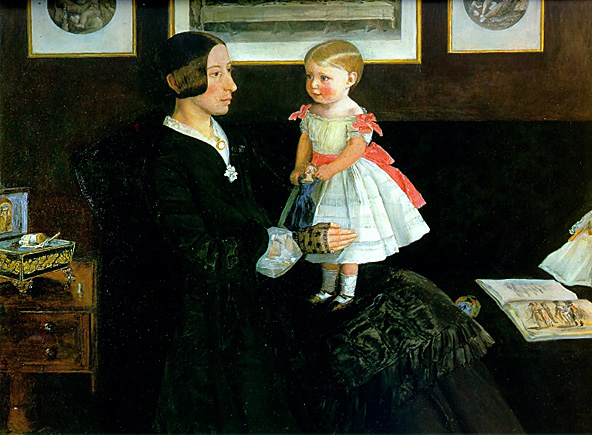

While married to Ruskin, she modeled for Millais' painting The Order of Release, in which she was depicted as the loyal wife of a Scottish rebel who has secured his release from prison. She then became close to Millais when he accompanied the couple on a trip to Scotland in order to paint Ruskin's portrait according to the critic's artistic principles. During this time, spent in Brig o'Turk in the Trossachs, they fell in love. Effie left Ruskin and she filed for an annulment, causing a major public scandal. In 1855, after her marriage to Ruskin was annulled, Effie and John Millais married. During the marriage she bore Millais eight children. She also modeled for a number of his works, notably Peace Concluded (1856), which idealizes her as an icon of beauty and fertility.

When Ruskin later sought to become engaged to a teenage girl, Rose la Touche, Rose's parents were concerned. They wrote to Effie, who replied by describing Ruskin as an oppressive husband. There is no reason to doubt Effie's sincerity, but her intervention helped to break up the engagement, probably contributing to Ruskin's later mental breakdown.

After his marriage, Millais began to paint in a broader style, which Ruskin condemned as a "catastrophe". Marriage had given him a large family to support, and it is claimed that Effie encouraged him to churn out popular works for financial gain and to maintain her busy social life. However, there is no evidence that Effie consciously pressured him to do so, though she was an effective manager of his career and often collaborated with him in choosing subjects. Effie's journal indicates her high regard for her husband's art, and his works are still recognizably Pre-Raphaelite in style several years after his marriage.

However, Millais eventually abandoned the Pre-Raphaelite obsession with detail and began to paint in a looser style which produced more paintings for the time and effort. Many were inspired by his family life with Effie, often using his children and grandchildren as models.

The annulment barred Effie from some social functions. She was not allowed in the presence of the queen, so if the queen was present at a party then Effie was not invited. Prior to the annulment, she had been socially very active and this really bothered her. Eventually, when Millais was dying, the queen relented, allowing Effie to attend a royal function.

Effie died a few months after her husband. She is buried in Kinnoull churchyard, Perth, which is depicted in Millais's painting The Vale of Rest.

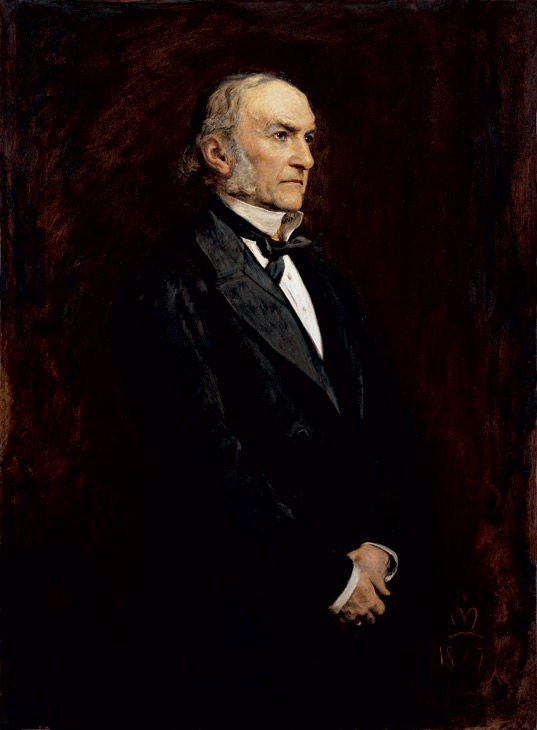

John Ruskin, English author and art critic, born in London. Son of a wealthy wine merchant, he was brought up in a cultured and religious family, but his mother's over protectiveness undoubtedly contributed to his later psychological troubles. On his frequent trips in Europe, he took an artists' and poet's delight both in landscape and works of art, especially medieval and Renaissance. His first great work, Modern Painters (5 volumes, 1843-60), began as a passionate defense of Turner's pictures, but became a study of the principles of Art. In The Seven Lamps Of Architecture (1849) and The Stones Of Venice (1851) he similarly treated the fundamentals of architecture. These principles enabled him, incidentally, to appreciate and defend the Pre-Raphaelites, then the target of violence and abuse. To Ruskin the relationship between art, morality and social justice was of paramount importance and he increasingly became preoccupied with social reform. His concern inspired, among others, William Morris and Arnold Toynbee, whilst in the practical field he founded the Working Men' s college (1854) and backed with money the experiments of Octavia Hill in the management of house property. He advocated social reforms which later were adopted by all political parties old age pensions, universal free education, better housing.

Gothic was for Ruskin the expression of an integrated and spiritual civilization; classicism represented paganism and corruption; the use of cast iron, and the increasing importance of function in architecture and engineering seemed to him a lamentable trend. He was Slade Professor of art at Oxford (1870-79) and (1883-84). His later works, eg. Sesame and Lilies(1865), The Crown Of Wild Olives (1866) and Fors Clavigera (1871 -74), contain the program of social reform in which he was so interested. Ruskin married (1848) Euphemia (Effie) Gray (the child of whom he had written The King Of the Golden River) but in 1854 the marriage was annulled and Effie later married Millais. Ruskin did not marry again, although on occasions he fell in love with girls much younger than himself and his last disappointment over Rose la Touche contributed to his mental breakdown which caused him to spend his last years in seclusion at Brantwood on Lake Coniston, where he wrote Praeterita, an unfinished account of his early life. Much of his wealth he devoted to the 'Guild of St. George', which he founded, and other schemes of social welfare.

This, Millais' first Pre-Raphaelite painting, was painted during 1848 when he was 19 years old. The subject is taken from Keats's poem 'Isabella' or 'The Pot of Basil'. The painting is also sometimes simply known as 'Isabella'. When exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1849, the following quotation from the poem was included in the catalogue:

Keats's source for this poem was a tale by the 14th century Italian author, Bocaccio, and the story is broadly as follows: Lorenzo and Isabella were deeply in love with each other. Isabella was the daughter of a rich and greedy Florentine merchant family to which Lorenzo was apprenticed. Discovering their sister's love for Lorenzo, Isabella's brothers plotted to kill Lorenzo. They lured him into a wood and there murdered him. Isabella pined for her love and in a vision saw the spot where he had been killed. She found his grave and dug up his body. Then cutting off Lorenzo's head and taking it home, she kept it hidden in a flowerpot in which she planted the sweet smelling herb, basil. Eventually her brothers discovered her macabre secret and stole the pot of basil, and full off guilt, they fled to Florence. Isabella grew weak through sorrow, and died.

Keats's poetry was a major preoccupation with the Brotherhood. Rossetti first read his poems in 1845 and thought him 'the greatest modern poet'. Hunt discovered Keats's work in 1848 and introduced Millais to his verse. Hunt and Millais planned to produce a series of etchings for book illustrations of Keats's 'Isabella'. Millais worked up his drawings into this large painting. Hunts work on the project did not get beyond the drawing stage. Hunt later suggested that Keats's work played a major part in uniting the group. In 1848, Keats was little known outside of a small group of devotees. His work had remained unpublished after his death in 1821. The Pre- Raphaelites were particularly attracted to the medieval themes in Keats's poems rather than to his classical subjects and it was the moral intensity of both 'Isabella' and 'The Eve of St Agnes' that they felt made them suitable as subjects. Both had the 'high seriousness' which the Brotherhood wished to characterize their work.

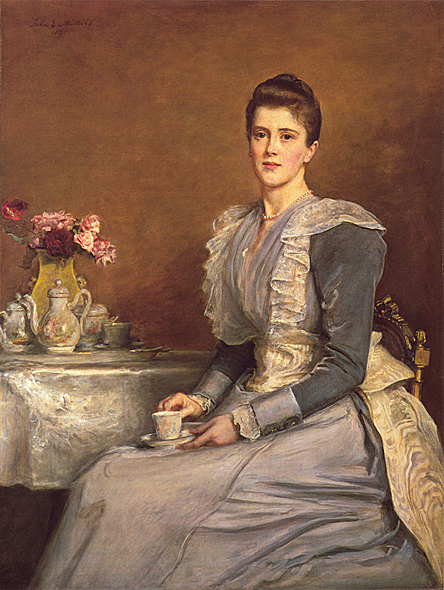

Louise Goode was born in Manchester. At the age of only seventeen, she married Frank Romer. In 1865, Romer became Private Secretary to Baron Rothschild in Paris. It was at this time, that Louise's artistic talent was spotted by Baroness Rothschild, who arranged for her to have some training. Unfortunately, Romer was dismissed by Rothschild in 1869. The couple returned to England, where the unfortunate Romer died in 1873. In 1874 Louise married the watercolour painter Joseph Middleton Jopling (1831-1884).

Jopling was the great friend and companion of Millais 'Joe Jopling.' Millais was to have a profound influence on Louise Jopling, as henceforth her painting was to show distinct signs of his example. In 1879, Millais painted a most striking and beautiful portrait of Louise (shown above), very much in his later and freer style. The words striking and beautiful could just as easily have been applied to Louise Jopling herself at this time. She painted pictures of domestic life and portraits, many of which were highly accomplished. Louise Jopling was the first woman to be elected a member of the Royal Society of British Artists.

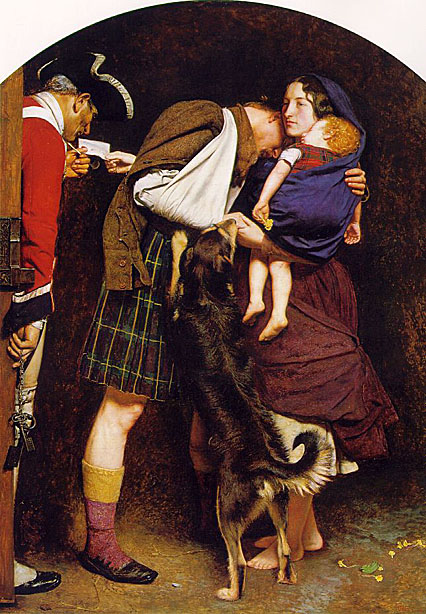

The Order of Release, 1746 is a painting by John Everett Millais exhibited in 1853. It is notable for the fact that it marks the beginnings of Millais's move away from the highly detailed Pre-Raphaelitism of his early years. Another notable fact is that Effie Gray, who later left her husband for the artist, modeled for the principal figure.

The painting depicts the wife of a rebel Scottish soldier, who has been imprisoned after the Jacobite rising of 1745, arriving with an order securing his release. She holds her child, showing the order to a guard, while her husband embraces her.

The Illustrated London News reviewed the painting as follows:

Truth to say, Mr. Millais, in this "Order of Release", has achieved for himself an "order of merit" worth more than any academic honor, and has earned a fame which a whole corporate academy might be proud to portion amongst its constituent members. Whilst we admit - nay assert this - we would by no means wish to be understood as enrolling ourselves incontinently of this young artist's "party" (for there is partisanship in everything, even in art); but simply as asserting that Pre-Raphaelitism (or rather the artists who have been foolishly styled Pre-Raphaelites) is a "great fact," and perhaps may lead to the regeneration of art in this country;. . .

The subject is simply that of a wife, with child in her arms, coming with an order of release for her husband, who has been taken in the Civil Wars. The husband, overcome with emotions, and weak from a recent wound (his arm is in a sling), can but fall upon her neck and weep; moan, "firm of purpose," sheds no tear; she has none to shed; but her eye is red and heavy with weeping and waking; and she looks at the stern and unconcerned with a proud look, expressing that she has won the reward for all her trouble past. The coloring, the textural execution, are marvelous (for these degenerate days).

Murthly Castle is located near Dunkeld in the Highlands of Perthshire, Scotland, where Millais and his Perth-born wife, Effie (the former wife of John Ruskin), made their first home.

The play begins with King Lear taking the decision to abdicate the throne and divide his kingdom among his three daughters: Goneril, Regan and Cordelia. The eldest two are already married, while Cordelia is much sought after as a bride, partly because she is her father's favourite. It is announced that each daughter shall be accorded lands according to how much she demonstrates her love for him in speech. To his surprise Cordelia refuses to outdo the flattery of her elder sisters, as she cannot be compelled to describe her love with dishonest hyperbole. Lear, in a fit of pique, divides her share of the kingdom between Goneril and Regan, and Cordelia is disowned. The King of France however marries her, even after she has been disinherited.

Soon after Lear abdicates the throne, he finds that Goneril and Regan's feelings for him have turned cold, and arguments ensue. The Earl of Kent, who has spoken up for Cordelia and been banished for his pains, returns disguised as the servant Caius, who will "eat no fish" (that is to say, he is a Protestant), in order to protect the king, to whom he remains loyal. Meanwhile, Goneril and Regan fall out with one another over their attraction to Edmund, the bastard son of the Earl of Gloucester-and are forced to deal with an army from France, led by Cordelia, sent to restore Lear to his throne. A cataclysmic war is fought.

Meanwhile, there is the Earl of Gloucester and his two sons, Edgar and Edmund. Edmund concocts false stories about his legitimate half-brother, and Edgar is forced into exile, affecting lunacy. Edmund engages in liaisons with Goneril and Regan. Gloucester is confronted by Regan's husband, the Duke of Cornwall, but is saved from death by several of Cornwall's servants, who object to the duke's treatment of Lear; one of the servants wounds the duke (but is killed by Regan), who plucks out Gloucester's eyes and throws him into the storm telling him to, "smell his way to Dover". Cornwall dies of his wound shortly thereafter.

Edgar, still under the guise of a homeless lunatic, finds Gloucester out in the storm. The earl asks him whether he knows the way to Dover, to which Edgar replies that he will lead him. Edgar, whose voice Gloucester fails to recognize, is shaken by encountering his blinded father and his guise is put to the test.

Lear appears in Dover, wandering and raving. Gloucester attempts to throw himself from a cliff, but is deceived by Edgar in order to save him and comes off safely, encountering the king shortly after. Lear and Cordelia are briefly reunited and reconciled before the battle between Britain and France. After the French lose, Lear is content at the thought of living in prison with Cordelia, but Edmund gives orders for them to be executed.

Edgar, in disguise, then fights Edmund, fatally wounding him. On seeing this, Goneril, who has already poisoned Regan out of jealousy, kills herself. Edgar reveals himself to Edmund and tells him that Gloucester has just died. On hearing this, and of Goneril and Regan's deaths, Edmund tells Edgar of his order to have Lear and Cordelia murdered and gives orders for them to be reprieved.

Unfortunately, the reprieve comes too late. Lear appears on stage with Cordelia's dead body in his arms, having killed the servant who hanged her, then dies himself.

Besides the subplot involving the Earl of Gloucester and his sons, the principal innovation Shakespeare made to this story was the death of Cordelia and Lear at the end. During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, this tragic ending was much criticized, and alternative versions were written and performed, in which the leading characters survived and Edgar and Cordelia were married.

Pippa Passes was a dramatic piece, as much play as poetry, by Robert Browning published in 1841 as the first volume of his Bells and Pomegranates series. The author described the work as the first of a series of dramatic pieces. His original idea was of a young innocent girl, moving unblemished through the crime-ridden neighborhoods of Asolo. The work caused outrage when it was first published, due to the matter-of-fact portrayals of many of the area's more disreputable characters - notably the adulterous Ottima - and for its frankness on sexual matters. Perhaps the most famous passage is below:

Besides the oft-quoted line "God's in his Heaven/All's right with the world!" above, the poem contains an amusing error rooted in Robert Browning's unfamiliarity with vulgar slang. Right at the end of the poem, in her closing song, Pippa calls out the following:

"Twat" both then and now is vulgar slang for a woman's genitals. When the editors of the Oxford English Dictionary inquired decades later where Browning had picked up the word, he directed them to a rhyme from 1660 that went thus: "They talk't of his having a Cardinall's Hat/They'd send him as soon an Old Nun's Twat." Browning apparently missed the vulgar joke and took "twat" to mean part of a nun's habit, pairing it in his poem with a priest's cowl.

.jpg)

The Northwest Passage was the name given to the treacherous sea route round the North American continent to the Pacific, a challenge that had thwarted explorers from Henry Hudson to, more recently, John Franklin. This work was intended to elicit patriotic sentiment through the image of a fiery ancient mariner who, fist clenched, shows his confidence in English nautical discovery. He and his daughter are surrounded by the mementos of a life on the seas.

"The North-West Passage, exhibited at the Academy in the spring of 1874, was perhaps the most popular of all Millais' paintings at the time, not only for its intrinsic merit, but as an expression more eloquent than words of the manly enterprise of the nation and the common desire that to England should fall the honor of laying bare the hidden mystery of the North. 'It might be done, and England ought to do it': this was the stirring legend that marked the subject of the picture; and its treatment by the artist lent a dignity and a pathos to the words that undoubtedly added to their force."

Millais' son John Guille Millais in his The Life and Letters of Sir John Everett Millais, 1899

Many British soldiers died of wounds or disease in the senseless Crimean War (1854-56), the result of long-standing political and economic disputes between England, France, Turkey and Russia. Each of these countries wanted to control the prosperous trade in the Middle East and to gain possession of territories in the region. Russia was defeated by the alliance of the other three countries, and on March 18, 1856, after a long diplomatic struggle, a peace treaty was signed in Paris. Russia made significant military concessions, but in the end no country achieved its aims.

Each member of the family tells us something about the meaning of the picture, by what they wear and by their actions. The father wears a dressing gown, indicating that he is convalescing, possibly from a concealed wound. He has just read the news of the war's end in the London Times newspaper, evidently with mixed emotions. Previously he had been reading a popular contemporary novel by William Thackeray (now lying behind his pillow), The Newcomes, about an exceptionally virtuous military man. The dog is an Irish wolfhound, an ancient British breed. Dogs usually symbolize strength and fidelity to man, and also marital fidelity when portrayed together with a married couple.

On his wife's face there is a resigned, melancholy gaze.4 Perhaps she is despondent about the gravity of her husband's condition. She wears an embroidered velvet gown and heavy gold jewelry, indicating that the family is well off and can afford such luxuries.

The little girl on the right wears a delicate lace dress, and clutches a medal bearing Queen Victoria's profile that her father had obviously earned. This medal honored participants in any of the five major battles of the war. She has been playing with the toy animals on her mother's lap, which represent the four warring countries: Britain (lion), Russia (bear), the Ottoman Empire (turkey) and France (rooster). These animals belong to a toy Noah's Ark set, then commonly found in English households. (The rest of the animals are in the box on the floor).

The other little girl holds a toy dove carrying an olive branch in its beak, symbolizing peace, but may also refer to the dove's role in the biblical story of Noah, when it returns to the Ark with proof of land. This child, too, wears a richly decorated velvet dress. The turkey carpet on the floor is another sign of the family's wealth and comfort.

Behind the group is a large, spreading myrtle bush. Since it is an evergreen, myrtle symbolizes eternal love, in particular conjugal fidelity. The battle picture on the wall represents an engraving, by James Heath, of a renowned painting by John Singleton Copley, the Death of Major Pearson. As a young commander, Major Pierson led his troops to victory by repelling a French invasion, but lost his life in the conflict.

Millais painted with oil paint on canvas, using very flat, thinly layered brushstrokes to create a smooth surface. The painting has been varnished, which not only protects the surface but also increases the brilliance of the colors.

Saint Agnes was a Roman virgin and martyr during the reign of Diocletian (early 4th century.) At first condemned to debauchery in a public brothel before her execution, her virginity was preserved by thunder and lightning from Heaven. Eight days after her execution, her parents visited her tomb and were greeted by a chorus of angels, including Agnes herself, with a white lamb at her side.

The Eve of St Agnes was written at Chichester and Bedhampton during the last half of January 1819. Perhaps Keats was inspired by the calendar - St Agnes's feast is celebrated on 21 January. He revised the work at Winchester in September; it was first published in 1820.

On the eve of St Agnes's feast day (20 January), virgins used divinations to 'discover' their future husbands. As Keats writes: '[U]pon St Agnes' Eve, / Young virgins might have visions of delight, / And soft adorings from their loves receive'. The poem tells the story of Madeline and her lover Porphyro. It is one of Keats's best-loved works. It also inspired numerous pre-Raphaelite paintings.

His prayer he saith, this patient, holy man;

Then takes his lamp, and riseth from his knees,

And back returneth, meagre, barefoot, wan,

Along the chapel aisle by slow degrees:

The sculptur'd dead, on each side, seem to freeze,

Emprison'd in black, purgatorial rails:

Knights, ladies, praying in dumb orat'ries,

He passeth by; and his weak spirit fails

To think how they may ache in icy hoods and mails.

Northward he turneth through a little door,

And scarce three steps, ere Music's golden tongue

Flatter'd to tears this aged man and poor;

But no---already had his deathbell rung

The joys of all his life were said and sung:

His was harsh penance on St. Agnes' Eve:

Another way he went, and soon among

Rough ashes sat he for his soul's reprieve,

And all night kept awake, for sinners' sake to grieve.

That ancient Beadsman heard the prelude soft;

And so it chanc'd, for many a door was wide,

From hurry to and fro. Soon, up aloft,

The silver, snarling trumpets 'gan to chide:

The level chambers, ready with their pride,

Were glowing to receive a thousand guests:

The carved angels, ever eager-eyed,

Star'd, where upon their heads the cornice rests,

With hair blown back, and wings put cross-wise on their breasts.

At length burst in the argent revelry,

With plume, tiara, and all rich array,

Numerous as shadows haunting fairily

The brain, new-stuff'd, in youth, with triumphs gay

Of old romance. These let us wish away,

And turn, sole-thoughted, to one lady there,

Whose heart had brooded, all that wintry day,

On love, and wing'd St Agnes' saintly care,

As she had heard old dames full rnany times declare.

They told her how, upon St Agnes' Eve,

Young virgins might have visions of delight,

And soft adorings from their loves receive

Upon the honey'd middle of the night,

If ceremonies due they did aright;

As, supperless to bed they must retire,

And couch supine their beauties, lily white;

Nor look behind, nor sideways, but require

Of Heaven with upward eyes for all that they desire.

Full of this whim was thoughtful Madeline:

The music, yearning like a God in pain,

She scarcely heard: her maiden eyes divine,

Fix'd on the floor, saw many a sweeping train

Pass by---she heeded not at all: in vain

Came many a tiptoe, amorous cavalier,

And back retir'd; not cool'd by high disdain,

But she saw not: her heart was otherwhere;

She sigh'd for Agnes' dreams, the sweetest of the year.

She danc'd along with vague, regardless eyes,

Anxious her lips, her breathing quick and short:

The hallow'd hour was near at hand: she sighs

Amid the timbrels, and the throng'd resort

Of whisperers in anger, or in sport;

'Mid looks of love, defiance, hate, and scorn,

Hoodwink'd with faery fancy; all amort,

Save to St Agnes and her lambs unshorn,

And all the bliss to be before to-morrow morn.

So, purposing each moment to retire,

She linger'd still. Meantime, across the moors,

Had come young Porphyro, with heart on fire

For Madeline. Beside the portal doors,

Buttress'd from moonlight, stands he, and implores

All saints to give him sight of Madeline,

But for one moment in the tedious hours,

That he might gaze and worship all unseen;

Perchance speak, kneel, touch, kiss---in sooth such things have been.

He ventures in: let no buzz'd whisper tell:

All eyes be muffled, or a hundred swords

Will storm his heart, Love's fev'rous citadel:

For him, those chambers held barbarian hordes,

Hyena foemen, and hot-blooded lords,

Whose very dogs would execrations howl

Against his lineage: not one breast affords

Him any mercy, in that mansion foul,

Save one old beldame, weak in body and in soul.

Ah, happy chance! the aged creature came,

Shuffling along with ivory-headed wand,

To where he stood, hid from the torch's flame,

Behind a broad hall-pillar, far beyond

The sound of merriment and chorus bland.

He startled her; but soon she knew his face,

And grasp'd his fingers in her palsied hand,

Saying, "Mercy, Porphyro! hie thee from this place;

"They are all here to-night, the whole blood-thirsty race!

"Get hence! get hence! there's dwarfish Hildebrand;

He had a fever late, and in the fit

He cursed thee and thine, both house and land:

Then there's that old Lord Maurice, not a whit

More tame for his gray hairs---Alas me! flit!

Flit like a ghost away."---"Ah, gossip dear,

We're safe enough; here in this arm-chair sit,

And tell me how"---"Good saints! not here, not here;

Follow me, child, or else these stones will be thy bier."

He follow'd through a lowly arched way,

Brushing the cobwebs with his lofty plume,

And as she mutter'd "Well-a---well-a-day!"

He found him in a little moonlight room,

Pale, lattic'd, chill, and silent as a tomb.

"Now tell me where is Madeline", said he,

"O tell me, Angela, by the holy loom

Which none but secret sisterhood may see,

"When they St Agnes' wool are weaving piously."

"St Agnes! Ah! it is St Agnes' Eve---

Yet men will murder upon holy days:

Thou must hold water in a witch's sieve,

And be liege-lord of all the Elves and Fays

To venture so: it fills me with amaze

To see thee, Porphyro!---St Agnes' Eve!

God's help! my lady fair the conjuror plays

This very night: good angels her deceive!

But let me laugh awhile, I've mickle time to grieve."

Feebly she laugheth in the languid moon,

While Porphyro upon her face doth look,

Like puzzled urchin on an aged crone

Who keepeth clos'd a wondrous riddle-book,

As spectacled she sits in chimney nook.

But soon his eyes grew brilliant, when she told

His lady's purpose; and he scarce could brook

Tears, at the thought of those enchantments cold

And Madeline asleep in lap of legends old.

Sudden a thought came like a full-blown rose,

Flushing his brow, and in his pained heart

Made purple riot: then doth he propose

A stratagem, that makes the beldame start:

"A cruel man and impious thou art:

Sweet lady, let her pray, and sleep, and dream

Alone with her good angels, far apart

From wicked men like thee. Go, go!---I deem

Thou canst not surely be the same that thou didst seem."

"I will not harm her, by all saints I swear,"

Quoth Porphyro: "O may I ne'er find grace

When my weak voice shall whisper its last prayer,

If one of her soft ringlets I displace,

Or look with ruffian passion in her face:

Good Angela, believe me by these tears;

Or I will, even in a moment's space,

Awake, with horrid shout, my foemen's ears,

And beard them, though they be more fang'd than wolves and bears."

"Ah! why wilt thou affright a feeble soul?

A poor, weak, palsy-stricken, churchyard thing,

Whose passing-bell may ere the midnight toll;

Whose prayers for thee, each morn and evening,

Were never miss'd." Thus plaining, doth she bring

A gentler speech from burning Porphyro;

So woeful, and of such deep sorrowing,

That Angela gives promise she will do

Whatever he shall wish, betide her weal or woe.

Which was, to lead him, in close secrecy,

Even to Madeline's chamber, and there hide

Him in a closet, of such privacy

That he might see her beauty unespied,

And win perhaps that night a peerless bride,

While legion'd fairies pac'd the coverlet,

And pale enchantment held her sleepy-eyed.

Never on such a night have lovers met,

Since Merlin paid his Demon all the monstrous debt.

"It shall be as thou wishest," said the Dame:

"All cates and dainties shall be stored there

Quickly on this feast-night: by the tambour frame

Her own lute thou wilt see: no time to spare,

For I am slow and feeble, and scarce dare

On such a catering trust my dizzy head.

Wait here, my child, with patience; kneel in prayer

The while: Ah! thou must needs the lady wed,

Or may I never leave my grave among the dead."

So saying, she hobbled off with busy fear.

The lover's endless minutes slowly pass'd;

The Dame return'd, and whisper'd in his ear

To follow her; with aged eyes aghast

From fright of dim espial. Safe at last

Through many a dusky gallery, they gain

The maiden's chamber, silken, hush'd and chaste;

Where Porphyro took covert, pleas'd amain.

His poor guide hurried back with agues in her brain.

Her falt'ring hand upon the balustrade,

Old Angela was feeling for the stair,

When Madeline, St Agnes' charmed maid,

Rose, like a mission'd spirit, unaware:

With silver taper's light, and pious care,

She turn'd, and down the aged gossip led

To a safe level matting. Now prepare,

Young Porphyro, for gazing on that bed;

She comes, she comes again, like dove fray'd and fled.

Out went the taper as she hurried in;

Its little smoke, in pallid moonshine, died:

She closed the door, she panted, all akin

To spirits of the air, and visions wide:

No utter'd syllable, or, woe betide!

But to her heart, her heart was voluble,

Paining with eloquence her balmy side;

As though a tongueless nightingale should swell

Her throat in vain, and die, heart-stifled, in her dell.

A casement high and triple-arch'd there was,

All garlanded with carven imag'ries

Of fruits, and flowers, and bunches of knot-grass,

And diamonded with panes of quaint device,

Innumerable of stains and splendid dyes,

As are the tiger-moth's deep-damask'd wings;

And in the midst, 'mong thousand heraldries,

And twilight saints, and dim emblazonings,

A shielded scutcheon blush'd with blood of queens and kings.

Full on this casement shone the wintry moon,

And threw warm gules on Madeline's fair breast,

As down she knelt for heaven's grace and boon;

Rose-bloom fell on her hands, together prest,

And on her silver cross soft amethyst,

And on her hair a glory, like a saint:

She seem'd a splendid angel, newly drest,

Save wings, for heaven:---Porphyro grew faint:

She knelt, so pure a thing, so free from mortal taint.

Anon his heart revives: her vespers done,

Of all its wreathed pearls her hair she frees;

Unclasps her warmed jewels one by one;

Loosens her fragrant bodice; by degrees

Her rich attire creeps rustling to her knees:

Half-hidden, like a mermaid in sea-weed

,

Pensive awhile she dreams awake, and sees,

In fancy, fair St Agnes in her bed,

But dares not look behind, or all the charm is fled.

Soon, trembling in her soft and chilly nest,

In sort of wakeful swoon, perplex'd she lay,

Until the poppied warmth of sleep oppress'd

Her soothed limbs, and soul fatigued away;

Flown, like a thought, until the morrow-day;

Blissfully haven'd both from joy and pain;

Clasp'd like a missal where swart Paynims pray;

Blinded alike from sunshine and from rain,

As though a rose should shut, and be a bud again.

Stol'n to this paradise, and so entranced,

Porphyro gazed upon her empty dress,

And listen'd to her breathing, if it chanced

To wake into a slumbrous tenderness;

Which when he heard, that minute did he bless,

And breath'd himself: then from the closet crept,

Noiseless as fear in a wide wilderness,

And over the hush'd carpet, silent, stept,

And 'tween the curtains peep'd, where, lo!---how fast she slept!

Then by the bed-side, where the faded moon

Made a dim, silver twilight, soft he set

A table, and, half anguish'd, threw thereon

A doth of woven crimson, gold, and jet:---

O for some drowsy Morphean amulet!

The boisterous, midnight, festive clarion,

The kettle-drum, and far-heard clarinet,

Affray his ears, though but in dying tone:---

The hall door shuts again, and all the noise is gone.

And still she slept an azure-lidded sleep,

In blanched linen, smooth, and lavender'd,

While he from forth the closet brought a heap

Of candied apple, quince, and plum, and gourd

With jellies soother than the creamy curd,

And lucent syrops, tinct with cinnamon;

Manna and dates, in argosy transferr'd

From Fez; and spiced dainties, every one,

From silken Samarcand to cedar'd Lebanon.

These delicates he heap'd with glowing hand

On golden dishes and in baskets bright

Of wreathed silver: sumptuous they stand

In the retired quiet of the night,

Filling the chilly room with perfume light.---

"And now, my love, my seraph fair, awake!

Thou art my heaven, and I thine eremite:

Open thine eyes, for meek St Agnes' sake,

Or I shall drowse beside thee, so my soul doth ache."

Thus whispering, his warm, unnerved arm

Sank in her pillow. Shaded was her dream

By the dusk curtains:---'twas a midnight charm

Impossible to melt as iced stream:

The lustrous salvers in the moonlight gleam;

Broad golden fringe upon the carpet lies:

It seem'd he never, never could redeem

From such a stedfast spell his lady's eyes;

So mus'd awhile, entoil'd in woofed phantasies.

Awakening up, he took her hollow lute,---

Tumultuous,---and, in chords that tenderest be,

He play'd an ancient ditty, long since mute,

In Provence call'd, "La belle dame sans mercy:"

Close to her ear touching the melody:---

Wherewith disturb'd, she utter'd a soft moan:

He ceased---she panted quick---and suddenly

Her blue affrayed eyes wide open shone:

Upon his knees he sank, pale as smooth-sculptured stone.

Her eyes were open, but she still beheld,

Now wide awake, the vision of her sleep:

There was a painful change, that nigh expell'd

The blisses of her dream so pure and deep,

At which fair Madeline began to weep,

And moan forth witless words with many a sigh;

While still her gaze on Porphyro would keep;

Who knelt, with joined hands and piteous eye,

Fearing to move or speak, she look'd so dreamingly.

"Ah, Porphyro!" said she, "but even now

Thy voice was at sweet tremble in mine ear,

Made tuneable with every sweetest vow;

And those sad eyes were spiritual and clear:

How chang'd thou art! how pallid, chill, and drear!

Give me that voice again, my Porphyro,

Those looks immortal, those complainings dear!

Oh leave me not in this eternal woe,

For if thou diest, my Love, I know not where to go."

Beyond a mortal man impassion'd far

At these voluptuous accents, he arose,

Ethereal, flush'd, and like a throbbing star

Seen mid the sapphire heaven's deep repose

Into her dream he melted, as the rose

Blendeth its odour with the violet,---

Solution sweet: meantime the frost-wind blows

Like Love's alarum pattering the sharp sleet

Against the window-panes; St Agnes' moon hath set.

Tis dark: quick pattereth the flaw-blown sleet:

"This is no dream, my bride, my Madeline!"

'Tis dark: the iced gusts still rave and beat:

"No dream, alas! alas! and woe is mine!

Porphyro will leave me here to fade and pine.---

Cruel! what traitor could thee hither bring?

I curse not, for my heart is lost in thine

Though thou forsakest a deceived thing;---

A dove forlorn and lost with sick unpruned wing."

"My Madeline! sweet dreamer! lovely bride!

Say, may I be for aye thy vassal blest?

Thy beauty's shield, heart-shap'd and vermeil dyed?

Ah, silver shrine, here will I take my rest

After so many hours of toil and quest,

A famish'd pilgrim,---saved by miracle.

Though I have found, I will not rob thy nest

Saving of thy sweet self; if thou think'st well

To trust, fair Madeline, to no rude infidel.

"Hark! 'tis an elfin-storm from faery land,

Of haggard seeming, but a boon indeed:

Arise---arise! the morning is at hand;---

The bloated wassailers will never heed:---

Let us away, my love, with happy speed;

There are no ears to hear, or eyes to see,---

Drown'd all in Rhenish and the sleepy mead:

Awake! arise! my love, and fearless be,

For o'er the southern moors I have a home for thee."

She hurried at his words, beset with fears,

For there were sleeping dragons all around,

At glaring watch, perhaps, with ready spears---

Down the wide stairs a darkling way they found.---

In all the house was heard no human sound.

A chain-droop'd lamp was flickering by each door;

The arras, rich with horseman, hawk, and hound,

Flutter'd in the besieging wind's uproar;

And the long carpets rose along the gusty floor.

They glide, like phantoms, into the wide hall;

Like phantoms, to the iron porch, they glide;

Where lay the Porter, in uneasy sprawl,

With a huge empty flagon by his side:

The wakeful bloodhound rose, and shook his hide,

But his sagacious eye an inmate owns:

By one, and one, the bolts fill easy slide:---

The chains lie silent on the footworn stones,---

The key turns, and the door upon its hinges groans.

And they are gone: ay, ages long ago

These lovers fled away into the storm.

That night the Baron dreamt of many a woe,

And all his warrior-guests, with shade and form

Of witch, and demon, and large coffin-worm,

Were long be-nightmar'd. Angela the old

Died palsy-twitch'd, with meagre face deform;

The Beadsman, after thousand aves told,

For aye unsought for slept among his ashes cold.

A knight-errant (plural knights-errant) is a figure of medieval chivalric romance literature. "Errant," meaning wandering or roving, indicates how the knight-errant would typically wander the land in search of adventures to prove himself as a knight, such as in a pas d'Armes.

The first known appearance of the term "knight-errant" was in the 14th century poem Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, where Sir Gawain arrives at the castle of Sir Bercilak de Haudesert after long journeys, and Sir Bercilak goes to welcome the "knygt erraunt."

Many knights-errant fit the ideal of the "knight in shining armor". A knight-errant performed all his deeds in the name of a lady, and invoked her name before performing an exploit. Such a knight might well be outside the structure of feudalism, wandering solely to perform noble exploits (and perhaps to find a lord to give his service to), but might also be in service to a king or lord, traveling either in pursuit of a specific duty that his overlord charged him with (as Sir Gareth rescuing the Lady Lyonesse), or to put down evildoers in general. This quest sends a knight on adventures much like the ones of a knight in search of them, as he happens on the same marvels; in The Faerie Queen, St. George is sent to rescue Una's parents' kingdom from a dragon, and Guyon has no such quest, but both knights encounter perils and adventures.

In the romances, his adventures frequently included greater foes than other knights, including giants, enchantresses, or dragons. They may also gain help that is out of ordinary; Sir Ywain assisted a lion against a serpent, and was thereafter accompanied by it, becoming the Knight of the Lion. Other knights-errant have been assisted by wild men of the woods, as in Valentine and Orson, or, like Guillaume de Palerme, by wolves that were, in fact, enchanted princes.

The resounding title comes from Cardinal Newman's The Dream of Gerontius. Millais painted this broad and rocky expanse of the River Braan instead of the nearby more picturesque waterfall by the Rumbling Brig. He worked in rain and snow from a temporary hut on the bank. In this mature work he effectively conveyed the features of volcanic rock without the meticulousness of Pre-Raphaelitism. The result is a masterpiece of observation and large-scale ambition.

"Rumbling Brig, November 9th 1876

Dearest Mary,

I fear that, after all, I shall have to give my work up and finish it next year, as there is nothing but snow over all, and I have a cold as well, which makes it positively dangerous to paint out in such weather as this. However, we will see what tomorrow brings. It is dreadfully dull here when there is nothing to do. I have been in my hut this morning, and I hoped a blink of sun would thaw sufficiently the snow on the foreground rocks to enable me to get on, but the storm is on again, and it is simply ridiculous trying to work, as everything is hidden with a white sheet…

Your affectionate father,

JE Millais"

Source: Art Renewal Center

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.