Disclaimer

Pierre Auguste Renoir

French Impressionist Painter & Sculptor

1841 - 1919

Self-Portrait: 1910

On Claude Monet

Without him I would have given up.

On Color and Art

On the whole, the modern palette is the same as the one used by the artists of Pompeii... I mean it has not been enriched. The ancients used earths, ochres, and ivory-black - you can do anything with that palette.

On Aging

The advantage of growing old is that you become aware of your mistakes more quickly.

(Pierre-Auguste Renoir)

Pierre-Auguste Renoir was a French artist who was a leading painter in the development of the Impressionist style. As a celebrator of beauty, and especially feminine sensuality, it has been said that "Renoir is the final representative of a tradition which runs directly from Rubens to Watteau".

Pierre-Auguste Renoir was born in Limoges, Haute-Vienne, France, and the child of a working class family. As a boy, he worked in a porcelain factory where his drawing talents led to him being chosen to paint designs on fine china. He also painted hangings for overseas missionaries and decorations on fans before he enrolled in art school. During those early years, he often visited the Louvre to study the French master painters.

In 1862 he began studying art under Charles Gleyre in Paris. There he met Alfred Sisley, Frederic Bazille, and Claude Monet. At times during the 1860's, he did not have enough money to buy paint. Although Renoir first started exhibiting paintings at the Paris Salon in 1864, recognition did not come for another ten years, due, in part, to the turmoil of the Franco-Prussian War.

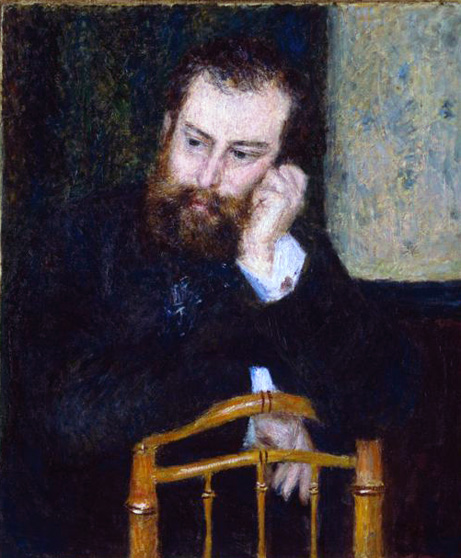

Alfred Sisley and His Wife: 1868

All the Impressionists, with the possible exception of Sisley, painted portraits at some time or other and general characteristics--consistent with the nature of the Impressionist movement in other ways--were the unconventional and natural attitude they looked for and the freshness of color they introduced. Courbet and Manet both gave an example to the younger painters in France in the relish with which, as realists, they pictured contemporary dress and the young Renoir, when he painted his newly-married friend Sisley with his wife, was likewise emboldened to make much of the current fashion in men's and women's clothes, though endowing them with an attraction that came from his visual approach. The black and grey of Sisley's attire is well contrasted with the splendor of red and gold in Madame Sisley's spreading skirts but there is the further contrast to this finery in the intimate and affectionate gesture with which he offers and she takes his arm. It was already one of the Impressionist devices to place the figures in sharp focus against a blurred background. The background here gives a hint of the open-air portraits the group would paint some years later at Argenteuil, though the figures and faces are painted as yet with no attempt to suggest outdoor lighting.

Alfred Sisley

Sisley was born in Paris to affluent English parents; William Sisley was in the silk business, and his mother Felicia Sell was a cultivated music connoisseur. At the age of 18, Sisley was sent to London to study for a career in business, but he abandoned it after four years and returned to Paris. Beginning in 1862 he studied at the atelier of Swiss artist Marc-Charles-Gabriel Gleyre, where he became acquainted with Frederic Bazille, Claude Monet, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir. Together they would paint landscapes en plein air (in the open air) in order to realistically capture the transient effects of sunlight. This approach, innovative at the time, resulted in paintings more colorful and more broadly painted than the public was accustomed to seeing. Consequently, Sisley and his friends initially had few opportunities to exhibit or sell their work. Unlike some of his fellow students who suffered financial hardships, Sisley received an allowance from his father-until 1870, after which time he became increasingly poor. Sisley's student works are lost. His earliest known work, Lane near a Small Town is believed to have been painted around 1864. His first landscape paintings are somber, colored with dark browns, greens, and pale blues. T hey were often executed at Marly and Saint-Cloud.

Lane near a Small Town

By Alfred Sisley

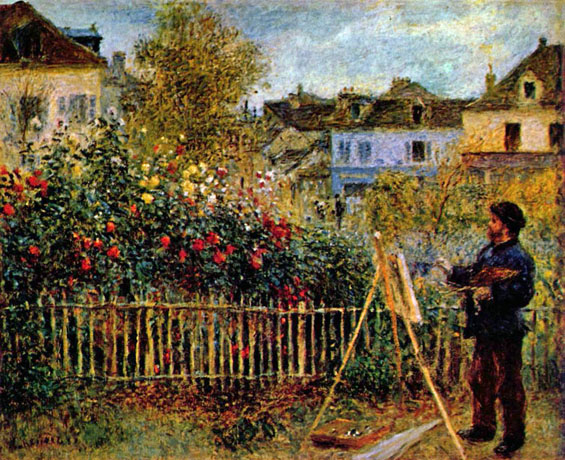

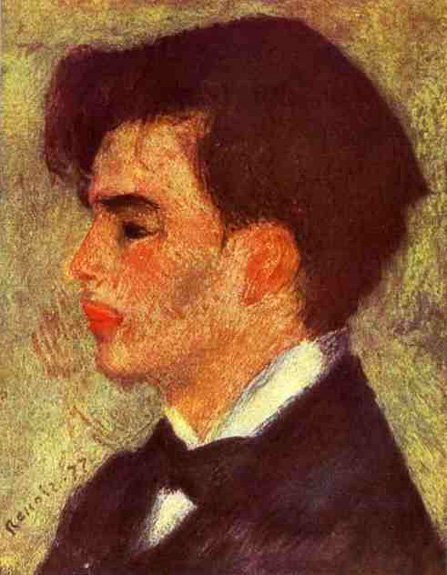

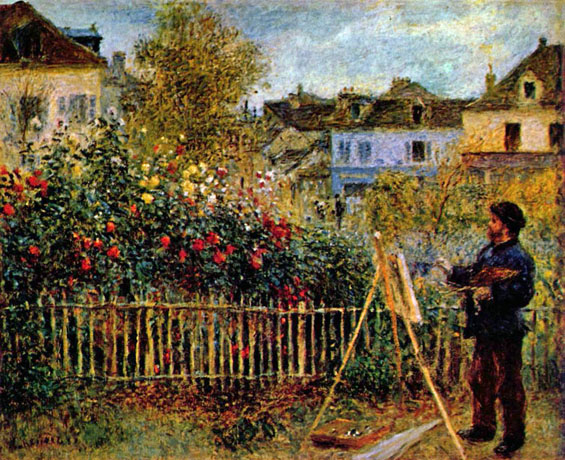

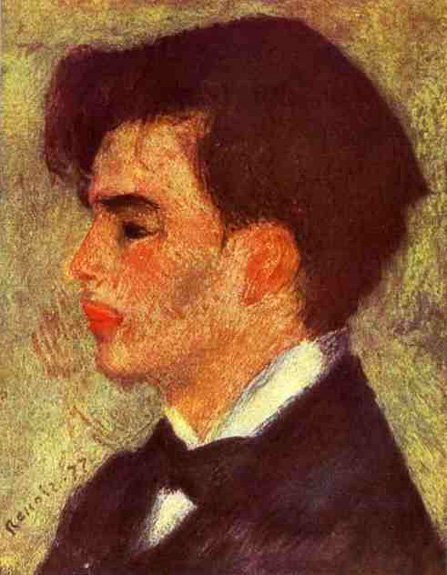

Portrait of Claude Monet: 1875

Renoir made a number of portraits of Monet around this time. This painting was exhibited in the second Impressionist exhibition and was well received by the crititcs.

Claude Monet Painting at Home

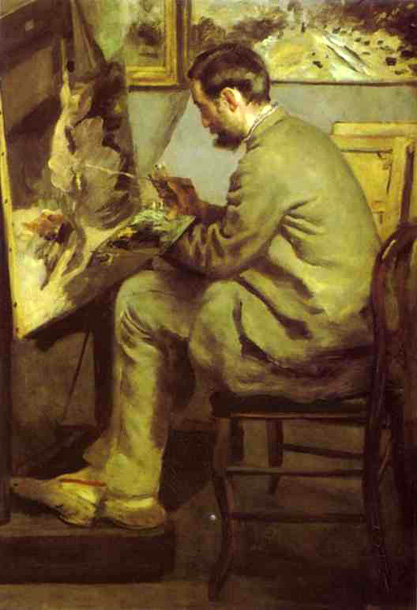

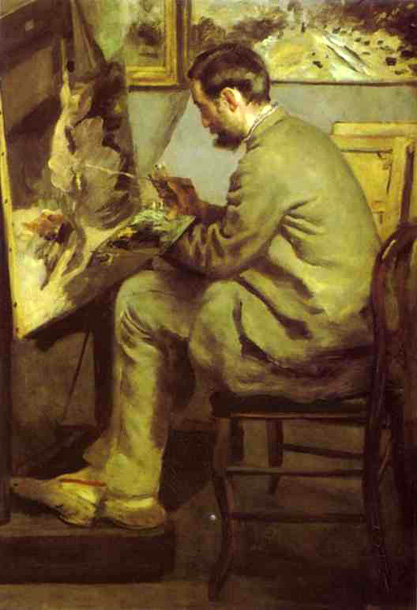

Fredrric Bazille at His-Easel: 1867

During the Paris Commune in 1871, while he painted on the banks of the Seine River, some members of a commune group thought he was a spy, and were about to throw him into the river when a commune leader, Raoul Rigault, recognized Renoir as the man who had protected him on an earlier occasion.

In 1874, a ten-year friendship with Jules Le Coeur and his family ended, and Renoir lost not only the valuable support gained by the association, but a generous welcome to stay on their property near Fontainebleau and its scenic forest. This loss of a favorite painting location resulted in a distinct change of subjects.

Jules Le Coeur Walking with Dogs in Fontainebleau Forest: 1866

Renoir experienced his initial acclaim when six of his paintings hung in the first Impressionist exhibition in 1874. In the same year two of his works were shown with Durand-Ruel in London.

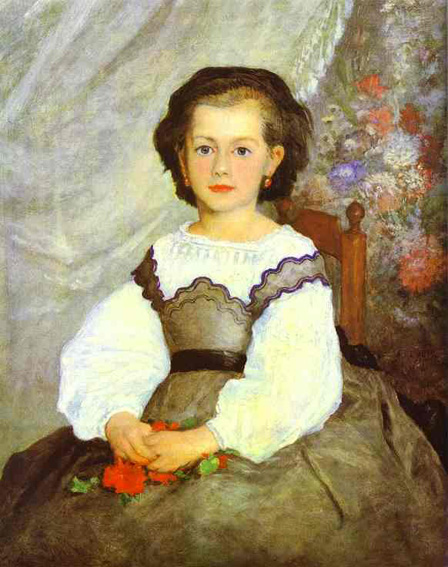

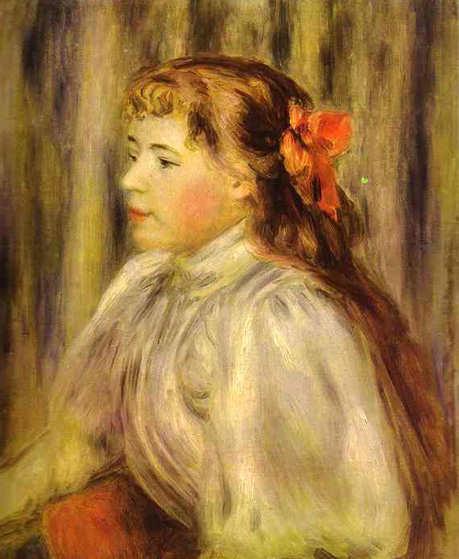

Jeanne Durand Ruel: 1876

Jeanne Durand-Ruel (1870-1914), daughter of Paul Durand-Ruel, later married to Albert Edouard Dureau.

La Loge: 1874

La Loge, the models for this painting were a Nini Lopez, with the nickname ‘Fish Mouth’, and Edmond Victoire Renoir, Renoir’s younger brother, Parisian journalist, he was a devoted fisherman and wrote many articles and even books on fishing.

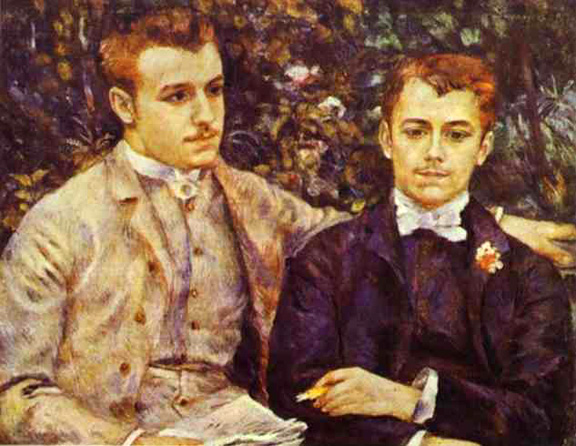

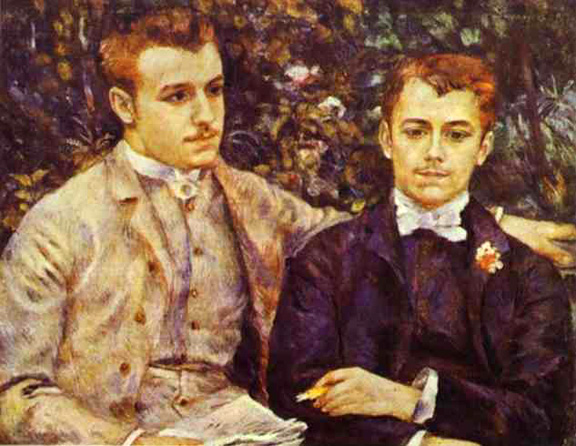

Charles and Georges Durand-Ruel: 1882

Paul Marie-Joseph Durand-Ruel (1833-1922), son of an artist. He was an art dealer, who did a lot to support Impressionists and promote their paintings. He sold pictures in Paris, London, Berlin, Boston. Founded a branch in New York in 1888, which was managed by his sons, Charles and Georges.

In 1881, he traveled to Algeria, a country he associated with Eugène Delacroix, then to Madrid, in Spain, to see the work of Diego Velázquez. Following that he traveled to Italy to see Titian's masterpieces in Florence, and the paintings of Raphael in Rome. On January 15, 1882 Renoir met the composer Richard Wagner at his home in Palermo, Sicily. Renoir painted Wagner's portrait in just thirty-five minutes. In the same year, Renoir convalesced for six weeks in Algeria after contracting pneumonia, which would cause permanent damage to his respiratory system.

The Swing: 1876

A young man seen from the back is talking to a young woman standing on a swing, watched by a little girl and another man, leaning against the trunk of a tree. Renoir gives us the impression of surprising a conversation - as if in a snapshot, he catches the glances turned towards the man seen from the back. The young woman is looking away as if she were embarrassed. The foursome in the foreground is balanced by the group of five figures sketchily brushed in the background.

The Swing has many points in common with The Ball at the Moulin de la Galette. The two pictures were painted in parallel in the summer of 1876. The models in The Swing, Edmond, Auguste Renoir's brother, the painter Robert Goeneutte and Jeanne, a young woman from Montmartre, figure among the dancers in The Ball. The same carefree atmosphere infuses both pictures. As in The Ball, Renoir is particularly trying to catch the effects of sunlight dappled by the foliage. The quivering light is rendered by the patches of pale color, particularly on the clothing and the ground. This particularly annoyed the critics when the painting was shown at the Impressionist exhibition of 1877. The Swing nonetheless found a buyer - Gustave Caillebotte, who also bought The Ball at the Moulin de la Galette.

La Moulin de la Galette: 1876

Renoir delighted in `the people's Paris', of which the 'Moulin de la Galette' near the top of Montmartre was a characteristic place of entertainment, and his picture of the Sunday afternoon dance in its acacia-shaded courtyard is one of his happiest compositions. In still-rural Montmartre, the Moulin, called `de la Galette' from the pancake which was its specialty, had a local clientèle, especially of working girls and their young men together with a sprinkling of artists who, as Renoir did, enjoyed the spectacle and also found unprofessional models. The dapple of light is an Impressionist feature but Renoir after his bout of plein-air landscape at Argenteuil seems especially to have welcomed the opportunity to make human beings, and especially women, the main components of picture. As Manet had done in La Musique aux Tuileries he introduced a number of portraits.

The girl in the striped dress in the middle foreground (as charming of any of Watteau's court ladies) was said to be Estelle, the sister of Renoir's model, Jeanne. Another of Renoir's models, Margot, is seen to the left dancing with the Cuban painter, Cardenas. At the foreground table at the right are the artist's friends, Frank Lamy, Norbert Goeneutte and Georges Rivière who in the short-lived publication L'Impressionniste extolled the 'Moulin de la Galette' as a page of history, a precious monument of Parisian life depicted with rigorous exactness. Nobody before him had thought of capturing some aspect of daily life in a canvas of such large dimensions.

Renoir painted two other versions of the subject, a small sketch now in the Ordrupgard Museum, near Copenhagen and a painting smaller than the Louvre version in the John Hay Whitney collection. It is a matter of some doubt whether the latter or the Louvre version was painted on the spot. Rivière refers to a large canvas being transported to the scene though it would seem obvious that so complete a work as the picture in the Louvre would in any case have been finished in the studio.

Portrait of Richard Wagner: 1882

Richard Wagner (1813-1883) was a German composer of the Romantic trend, born in Leipzig. Author of large and pessimistic musical works, i. e. Tannhäuser (1845), Lohengrin (1848), Siegfried (1857), Tristan und Isolde (1859), Die Meistersinger (1870) and others. He was a prolific writer of letters and prose, issued some essays on music. His ultra-nationalistic and anti-Semitic views made his music very popular in Nazi Germany. He wrote an autobiography, My Life.

In 1883, he spent the summer in Guernsey, creating fifteen paintings in little over a month. Most of these feature Moulin Huet, a bay in Saint Martin's, Guernsey. Guernsey is one of the Channel Islands in the English Channel, and it has a varied landscape which includes beaches, cliffs, bays, forests, and mountains. These paintings were the subject of a set of commemorative postage stamps, issued by the Bailiwick of Guernsey in 1983.

Children on the Beach of Guernesey: 1883

While living and working in Montmartre, Renoir employed as a model Suzanne Valadon, who posed for him (The Bathers, 1885-7; Dance at Bougival, 1883) and many of his fellow painters while studying their techniques; eventually she became one of the leading painters of the day.

City Dance

(Suzanne Valadon and Eugene Pierre Lestringuez): 1883

_1883.jpg)

Dance at Bougival

(Suzanne Valadon and Paul Lhote): 1883

_1883.jpg)

Girl Braiding Her Hair

(Suzanne Valadon): 1885

_1885.jpg)

Suzanne Valadon was an illegitimate child and claimed (untruthfully) to be a foundling. As a child she moved with her mother to Paris and became a washer girl. They went to live in Montmartre and there she became an acrobat in a circus. An injury ended this and then she became model and mistress for painters like Dégas, Toulouse-Lautrec and Renoir. She also had an affair with the painter Puvis de Chavannes.

Encouraged by Degas, Valadon became a good painter herself, but she would stand in the shadows of her strange but talented son Maurice Utrillo.

Her first exhibitions in the early nineties consisted mainly of portraits, among them that of her lover Erik Satie. Their intense affair lasted from January to June 1893 and this seems to have been Satie's only love affair. In 1894 she was the first woman to be admitted to the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts.

Her marriage to the exchange broker Paul Mousis in 1896 failed and she left him in 1909 for the young painter André Utter. He was twenty years her junior, but she married him in 1914.

Valadon turned to painting landscapes, still lifes and female nudes that were naked in an unashamed way that was shocking at this time. When she died Georges Braque, Andre Derain and Pablo Picasso, attended her funeral at the Cimetière parisien, St.-Ouen (Paris).

Her work can be found at the Centre Pompidou, Paris and at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

The Bathers (A Study): 1884

The Bathers: 1887

The Bathers - (Detail): 1887

_One_1887.jpg)

The Bathers - (Detail): 1887

_Two_1887.jpg)

In 1887, a year when Queen Victoria celebrated her Golden Jubilee, and upon the request of the queen's associate, Phillip Richbourg, he donated several paintings to the "French Impressionist Paintings" catalog as a token of his loyalty.

In 1890 he married Aline Victorine Charigot, who, along with a number of the artist's friends, had already served as a model for Les Déjeuner des canotiers (Luncheon of the Boating Party, 1881), and with whom he had already had a child, Pierre, in 1885. After his marriage Renoir painted many scenes of his wife and daily family life, including their children and their nurse, Aline's cousin Gabrielle Renard. The Renoirs had three sons, one of whom, Jean, became a filmmaker of note and another, Pierre, became a stage and film actor.

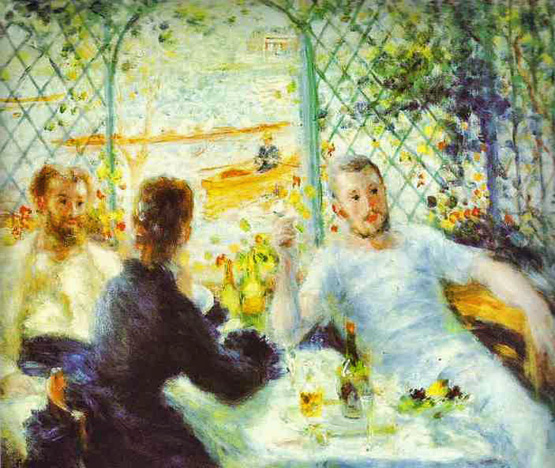

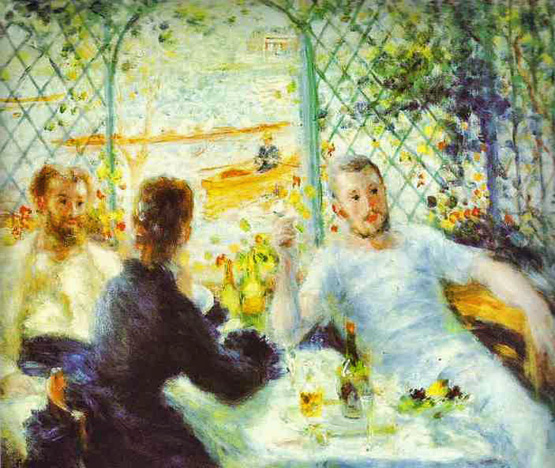

The Luncheon of the Boating Party: 1881

According to Renoir himself it was towards 1883 that there came a break in his work and he felt that he had reached the end of Impressionism, but a change of style is already discernible in this large painting of 1881. His earlier picture of canotiers at lunch arrived at a balance between Impressionist technique and subject interest; here style is subordinate to genre, or is altered to suit its purposes. There is definite outline where formerly there was the surrounding ambience of light. The memory of the aristocratic fete champetre that gave a lingering flagrance to earlier open-air groups has not entirely vanished but a sharper impression of slightly vulgar jollity tends to dispel it. In the wealth of detail and incident something of the unity that is so admirable a feature of Impressionism in general is lost. But there is also much to admire: the fascinating glimpse of the river; the still-life with its richness of fruit and wine; the varied poses and expressions of the party. Such as large work was of necessity painted in the studio but Renoir was already coming to the conclusion, contrary to his earlier practice, that painting direct from nature had many drawbacks compared to studio work --- that it made compositions impossible and soon fell into monotony. The work of Monet and Pissarro might disprove this assertion as a generality but it served to give Renoir a fresh individual impetus.

Aline and Pierre: 1887

Mother Nursing Her Child

(Aline and Pierre): 1886

_1886.jpg)

Country Dance

(Aline Charigot and Paul Lhote): 1883

_1883.jpg)

Gabrielle with Renoir's Children: 1892-1894

Dancer with Castanets

(Gabrielle Renard): 1909

_1909.jpg)

Dancer with Tambourne

(Gabrielle Renard): 1909

_1909.jpg)

Gabrielle with a Rose: 1911

Gabrielle with Jewel Box: 1910

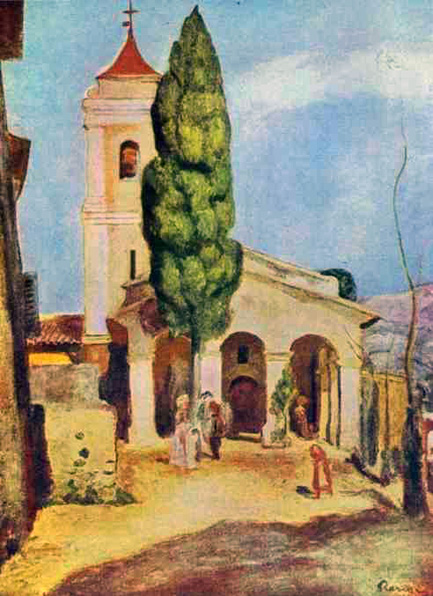

Around 1892, Renoir developed rheumatoid arthritis. In 1907, he moved to the warmer climate of "Les Collettes," a farm at Cagnes-sur-Mer, close to the Mediterranean coast. Renoir painted during the last twenty years of his life, even when arthritis severely limited his movement, and he was wheelchair-bound. He developed progressive deformities in his hands and ankylosis of his right shoulder, requiring him to adapt his painting technique. In the advanced stages of his arthritis, he painted by having a brush strapped to his paralyzed fingers.

Landscape near Cagnes: 1902

House at Cagnes: 1907

Terrace at Cagnes: 1905

Terrace at Cagnes

(Bridgestone Museum): 1905

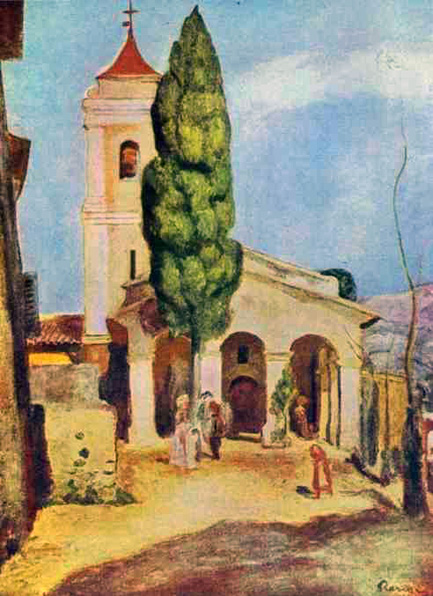

A Church at Cagnes: 1905

During this period he created sculptures by directing an assistant who worked the clay. Renoir also used a moving canvas, or picture roll, to facilitate painting large works with his limited joint mobility.

In 1919, Renoir visited the Louvre to see his paintings hanging with the old masters. He died in the village of Cagnes-sur-Mer, Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur, on December 3.

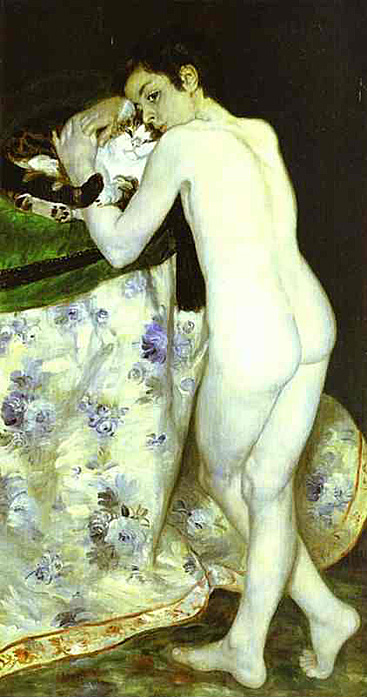

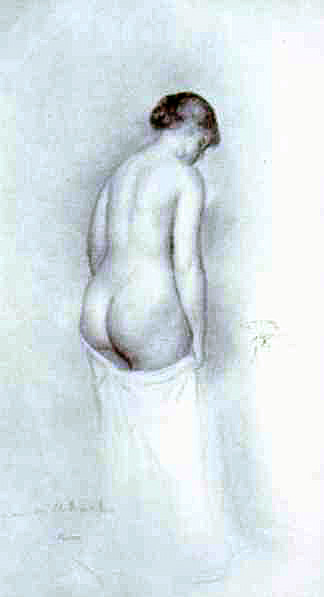

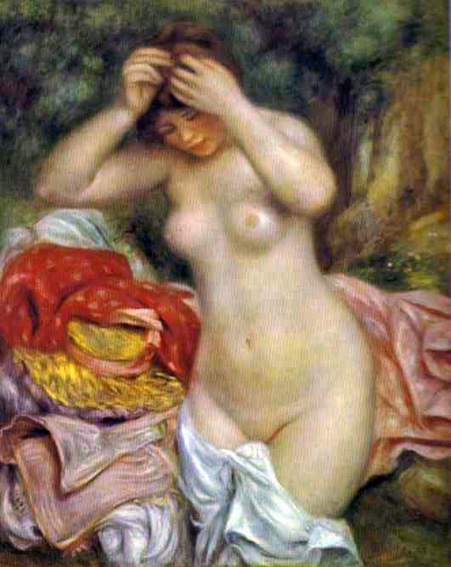

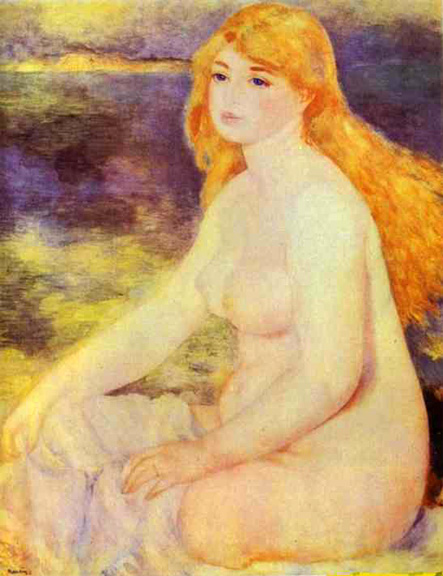

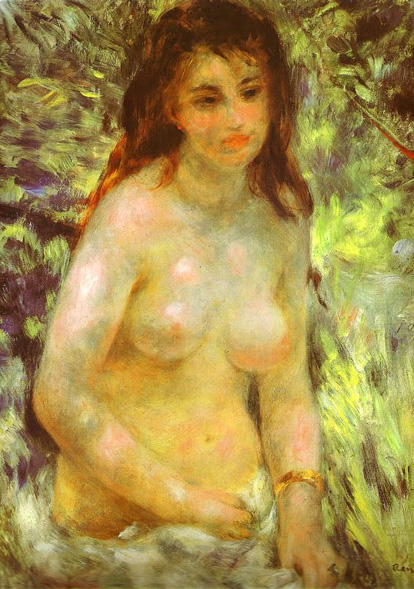

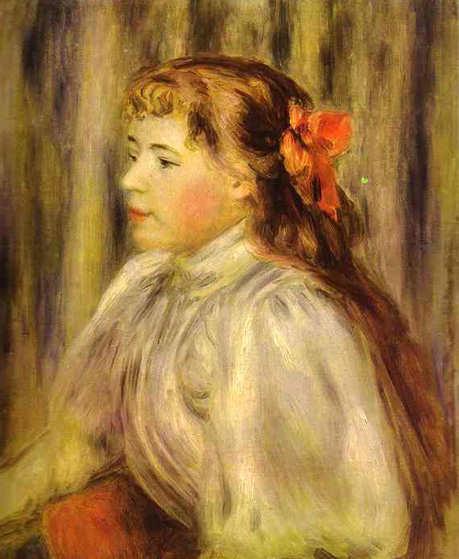

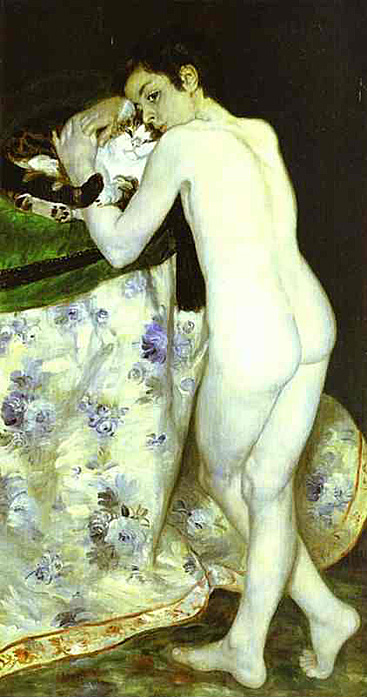

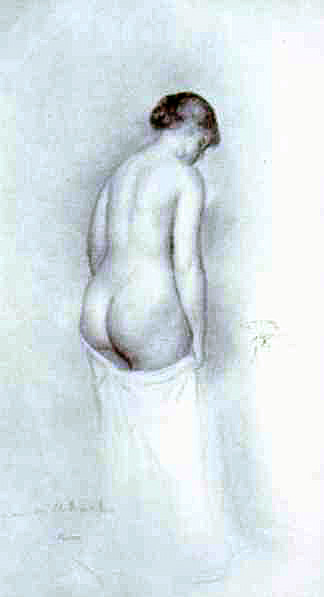

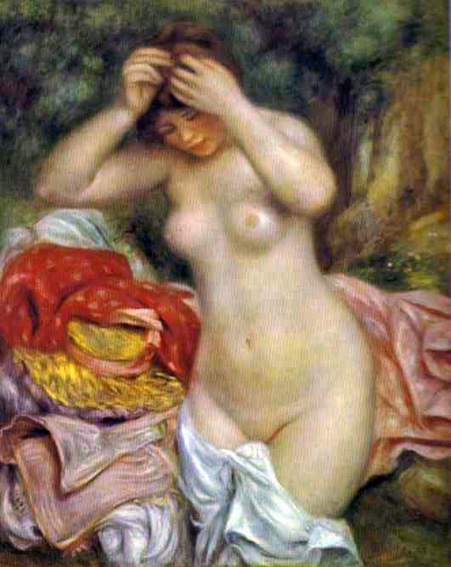

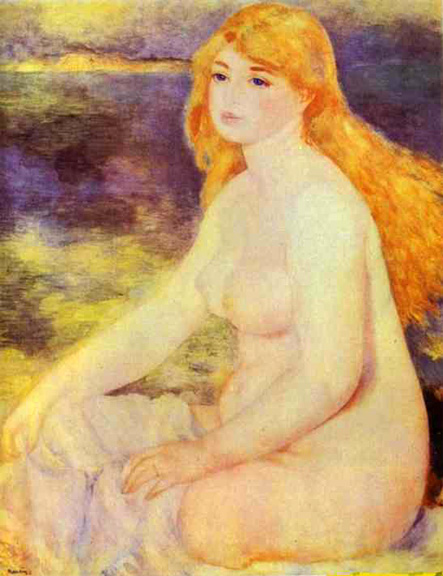

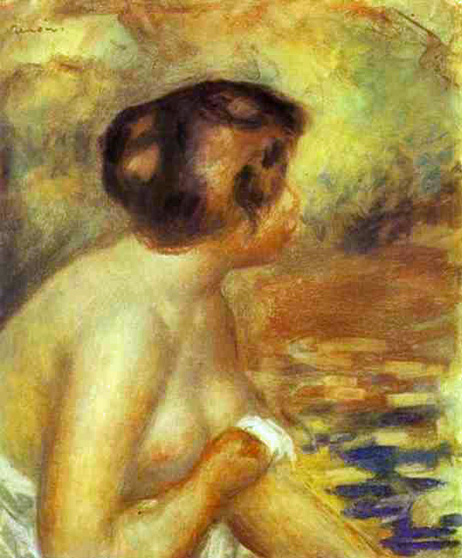

Renoir's paintings are notable for their vibrant light and saturated color, most often focusing on people in intimate and candid compositions. The female nude was one of his primary subjects. In characteristic Impressionist style, Renoir suggested the details of a scene through freely brushed touches of color, so that his figures softly fuse with one another and their surroundings.

His initial paintings show the influence of the colorism of Eugène Delacroix and the luminosity of Camille Corot. He also admired the realism of Gustave Courbet and Édouard Manet, and his early work resembles theirs in his use of black as a color. As well, Renoir admired Edgar Degas' sense of movement. Another painter Renoir greatly admired was the 18th century master François Boucher.

A fine example of Renoir's early work, and evidence of the influence of Courbet's realism, is Diana, 1867. Ostensibly a mythological subject, the painting is a naturalistic studio work, the figure carefully observed, solidly modeled, and superimposed upon a contrived landscape. If the work is still a 'student' piece, already Renoir's heightened personal response to female sensuality is present. The model was Lise Tréhot, then the artist's mistress and inspiration for a number of paintings.

Diana: 1867

In the late 1860's, through the practice of painting light and water en plein air (in the open air), he and his friend Claude Monet discovered that the color of shadows is not brown or black, but the reflected color of the objects surrounding them. Several pairs of paintings exist in which Renoir and Monet, working side-by-side, depicted the same scenes (La Grenouillère, 1869).

La Grenouillere: 1869

(National Museum Stockholm)

La Grenouillere: 1869

(Pushkin Museum)

One of the best known Impressionist works is Renoir's 1876 Dance at Le Moulin de la Galette (Le Bal au Moulin de la Galette). The painting depicts an open-air scene, crowded with people, at a popular dance garden on the Butte Montmartre, close to where he lived.

The works of his early maturity were typically Impressionist snapshots of real life, full of sparkling color and light. By the mid 1880's, however, he had broken with the movement to apply a more disciplined, formal technique to portraits and figure paintings, particularly of women, such as The Bathers, which was created during 1884-87. It was a trip to Italy in 1881, when he saw works by Raphael and other Renaissance masters, that convinced him that he was on the wrong path, and for the next several years he painted in a more severe style, in an attempt to return to classicism. This is sometimes called his "Ingres Period", as he concentrated on his drawing and emphasized the outlines of figures.

On the Terrace

(Two Sisters): 1881

The Two Sisters is one of the peaks of Renoir's artistic career and one of the most popular items in the Art Institute of Chicago. The painting was given its second title - On the Terrace - by the dealer and patron of the Impressionists Paul Durand?Ruel, its first and for many years only owner. The painter was evidently happy with this, the more so since his figures were not indeed related.

The work was painted at Chatou, which Renoir considered "the most pleasant of all Paris suburbs". Renoir and the friends whom he recorded in The Luncheon of the Boating Party (1880, Phillips Collection, Washington), in which the same stretch of river with its wooden banks serves as a background, still perceived Chatou as an ideal leisure spot. The Two Sisters was painted on the same terrace of the Maison Fournaise as The Luncheon. It is believed that Renoir began The Two Sisters in April 1881 when he wrote to the critic Théodore Duret, "I am struggling with trees in colour, with portraits of women and children, and besides that I do not want to see anything…"

The year before on the same terrace Renoir had painted another girl, touchingly delicate, but lacking the charm of the new model (Girl on a Balcony, Cushing collection). This time he conceived a much more complicated composition and placed his subjects directly by the railing, obtaining the best structural interconnection of all elements. Renoir even included a clumsy tub of flowers, both for the sake of contrast and for greater compositional stability.

The Impressionists were painters of light and 'Light' plays an exceptionally important role in the painting, glistening on the water, playing in the agglomerations of flowers and foliage behind the terrace, flashing out in the bud on the breast of the older girl and the chaplet of the younger and finally freezing in sparks in the eyes of both these charming heroines. The older girl's glowing scarlet hat, the resonance of color that is expressively emphasized by the fresh green of the background, from the first rivets any gaze to the young face, its pure oval, tender skin, the beautiful eyes of a dreamer.

The Two Sisters was first presented to the public at the seventh Impressionist exhibition in the spring of 1882, together with such Renoir masterpieces as the Hermitage's Girl with a Fan, Girl with a Cat and A Box in the Opera (Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown) and The Luncheon of the Boating Party.

It is not known who posed for the younger "sister", but thirty years ago François Daulte, an expert on Renoir's work, established that the older girl was Jeanne Darlot (1863-1914). She was eighteen at the time. Soon she joined the Théâtre Gymnase where she acted supporting roles in comedies. The attractive actress quite often had her photograph in the papers. A decade later Jeanne Darlot had her début at the Comédie Française, but soon after she quit the stage. Evidently her theatrical career was not shaping the way she wanted. She did not marry either, becoming the kept mistress of a chocolate manufacturer, and later of an influential senator.

It is a special quality of the heroines of Renoir's paintings that they both resemble and do not resemble the models. Comparing photographs with the portraits it is obvious that in paintings they are immeasurably more attractive. Renoir's pictures are first and foremost paintings, and only then the motif or the personage. And his painting always contains a lofty image, yet one deliberately devoid of bombast, so that the artist could permit himself both humor and the play of allusions. Without remembering that, it is impossible to understand the detail in the bottom left corner of the composition that might at first glance be taken for flowers. There is little logical justification for such a detail, since the painting is set not in an interior, but in the open air. It has been suggested that the balls of wool appeared as Renoir's response to the insinuation of a critic who compared his painting to knitting. One of his masterpieces was described as "a weak sketch seemingly executed in wool of different colors". On the other hand, Degas wittily recalled the balls of wool. "Renoir," he said, "can do whatever he likes" and added, thinking of the wholly non-programmatic nature of his colleague's art, "You've seen a cat playing with balls of different colored wool?"

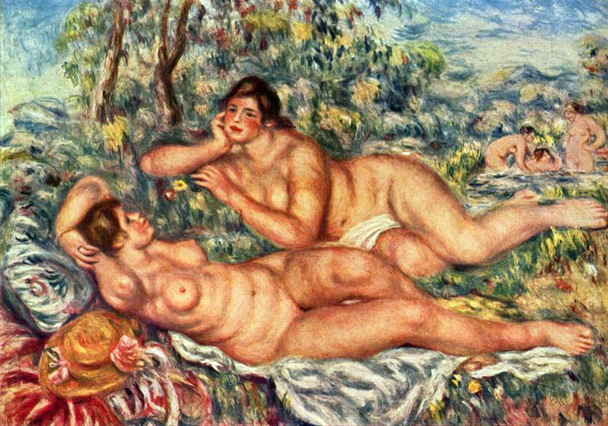

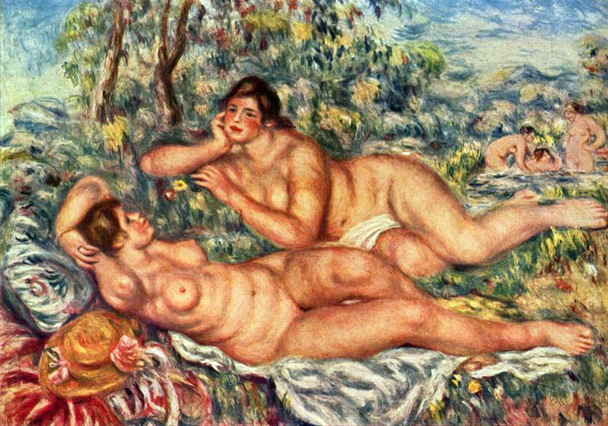

After 1890, however, he changed direction again, returning to the use of thinly brushed color which dissolved outlines as in his earlier work. From this period onward he concentrated especially on monumental nudes and domestic scenes, fine examples of which are Girls at the Piano, 1892, and Grandes Baigneuses, 1918-19. The latter painting is the most typical and successful of Renoir's late, abundantly fleshed nudes.

Girls at the Piano: 1892

Les Grandes Baigneuses: 1918-19

A prolific artist, he made several thousand paintings. The warm sensuality of Renoir's style made his paintings some of the most well-known and frequently-reproduced works in the history of art.

Acknowledging modern criticism of Renoir's sensuality, Lawrence Gowing wrote:

"Is there another respected modern painter whose work is so full of charming people and attractive sentiment? Yet what lingers is not cloying sweetness but a freshness that is not entirely explicable...One feels the surface of his paint itself as living skin: Renoir's aesthetic was wholly physical and sensuous, and it was unclouded...These interactions of real people fulfilling natural drives with well-adjusted enjoyment remain the popular masterpieces of modern art (as it used to be called), and the fact that they are not fraught and tragic, without the slightest social unrest in view, or even much sign of the spacial and communal disjunction which some persist in seeking, is far from removing their interests."

Albert Aurier, an art critic and early essayist on the impressionists, wrote in 1892:

"With such ideas, with such a vision of the world and of femininity, one might have feared that Renoir would create a work which was merely pretty and merely superficial. Superficial it was not; in fact it was profound, for if, indeed, the artist has almost completely done away with the intellectuality of his models in his paintings, he has, in compensation, been prodigal with his own. As to the pretty, it is undeniable in his work, but how different from the intolerable prettiness of fashionable painters."

The following works of Pierre Auguste Renoir have not been placed in any thematic or chronological order except possibly alphabetical in places. There will be portraits, nudes, as well as landscapes and family pictures,

~Senex Magister

A Boy with a Cat: 1868-69

A Girl: 1885-1890

A Girl: 1890

A Girl with a Watering Can: 1876

This painting has long been a favorite of visitors to the National Gallery of Art -- and it seems that Renoir painted it with exactly this hope, that it would please a large audience. The first impressionist exhibition, in 1874, had brought Renoir and his fellow artists more notoriety than business, and the auction he optimistically organized for his own work the following year was a financial disaster. Unlike Cassatt, who had family wealth, Renoir, the son of a tailor, was in a constant struggle for money in his early career. He began to paint charming, light-filled scenes with women and children, like this one, in the hopes of increasing sales. He probably thought that the pretty child in her fancy dress might also attract portrait commissions. Although it was landscape that had provided the first, and most important, inspiration for impressionism, Renoir's instinct always led him back to the figure.

The deep blue of the dress, the bright red of the bow and the girl's lips, and the cool greens of the lush garden behind her are all given a prismatic brilliance by Renoir's brushwork. Rather than blend his colors, Renoir has applied them in individual touches that dissolve edges and seem to shimmer with light. Impressionism sought to capture the effect of light on the senses, communicating a visual signal with each stroke of the brush.

A Hat with a Pin: 1900

A Morning Ride in the Bois de Boulogne: 1873

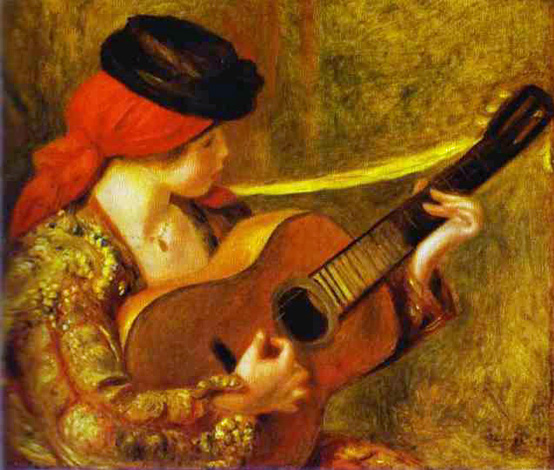

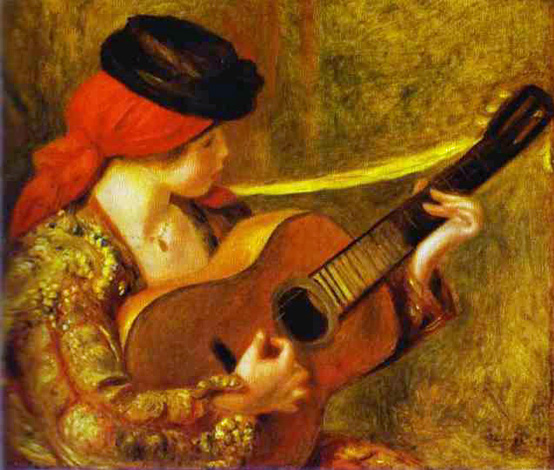

A Woman Playing the Guitar: ca 1880

A Woman with a Dog

(Portrait of Madame Renoir): 1880

_1880.jpg)

Renoir's wife looks happily at her dog, and the dog appears to look back. It is Aline looking at her dog Bob. This reinforces the idea that Renoir felt most comfortable with Aline. Of all his dancing women and of all the women in this painting, Luncheon of the Boating Party, he could not allow any to have such a good time as Aline. At the time when he painted this painting, he was already involved with her. In fact, it is thought of as a turning point in his life. As a result, he paints her happily and the others not so. Their failed return of glances gives all the people but Aline a sense of rejection.

Thus, this famous painting, although thought of as one of Renoir's happiest works, is really another depiction of his social uneasiness. Only in Aline, who enjoys the gaze of her dog Bob, can he find comfort.

A Young Woman: 1875

After the Bath (Study): 1884

After the Bath: 1888

After the Bath: 1910

Algerian Landscape - The Ravine of the Femme Sauvage: 1881

Apples and Flowers

(Les pommes et fleurs): ca 1895-96

_ca_1895_96.jpg)

Arum and Conservatory Plants: 1864

At the Inn of Mother Anthony: 1866

Banks of the Seine at Asnieres: ca 1879

Banks of the Seine at Champrosay: 1876

Barges on the Seine: 1869

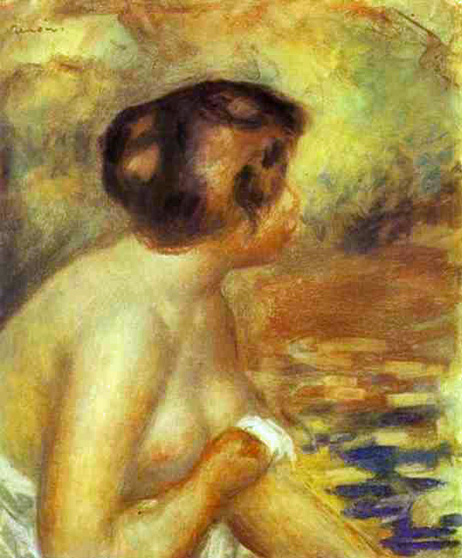

Bather

(La Baigneuse au griffon): 1870

_1870.jpg)

Bather Admiring Herself in the Water called Psyche: ca 1910

Bather Arranging Her Hair: 1893

Before the Bath: ca 1873-75

Blonde Nude: 1882

Bouquet in Front of a Mirror: 1876

Bouquet of Chrysanthemums: ca 1885

Bouquet of Roses

(Bouquet de roses): ca 1909-13

_ca_1909_13.jpg)

By the Lake: ca 1880

By the Seashore: 1883

Like other artists who painted in an Impressionist style in the 1870's, Renoir eventually began to explore a different manner of painting. A trip to Italy in 1881-82 brought prolonged exposure to Renaissance art and led him to emphasize contours and modeling in his painting. He also began to abandon the notion that scenes should be painted outdoors to capture nuances of light and atmosphere. "By the Seashore" is thought to have been painted in the artist's studio, where Renoir's model, Aline Charigot-whom he married in 1890-posed in a wicker chair. Although Renoir visited Guernsey the year this painting was made, the beach depicted here is probably not in the Channel Islands but near Dieppe, on the Normandy coast.

Caryatides: ca 1910

Child with a Whip: 1885

Children's Afternoon at Wargemont: 1884

Clown: 1868

Conversation with the Gardener: ca 1875

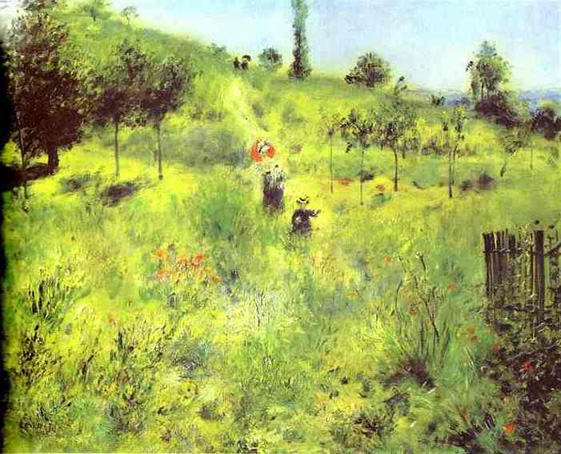

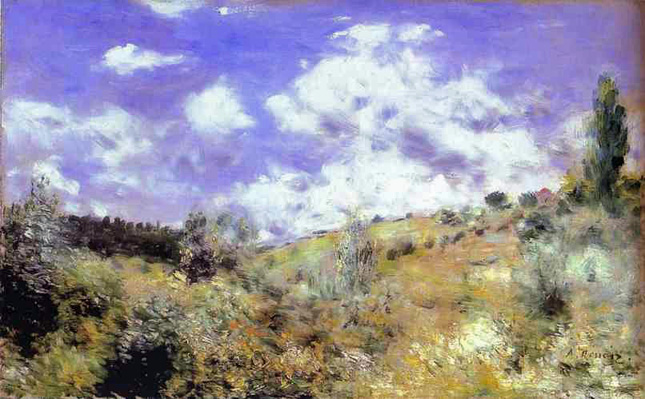

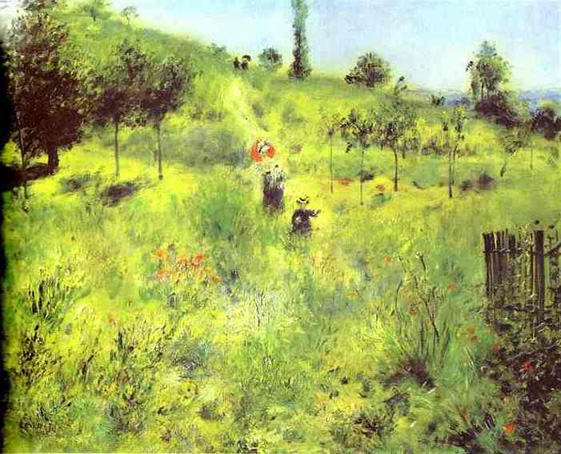

Country Footpath in the Summer: ca 1874

Doges Palace - Venice: 1881

The Palazzo Ducale, or Doge’s Palace, was the seat of the government of Venice for centuries. As well as being the home of the Doge (the elected ruler of Venice) it was the venue for its law courts, its civil administration and bureaucracy and — until its relocation across the Bridge of Sighs — the city jail.

Ebbing Tide at Yport

(Maree basse a Yport): ca 1883

_ca_1883.jpg)

Field of Banana Trees: 1881

Flowers in a Vase: 1869

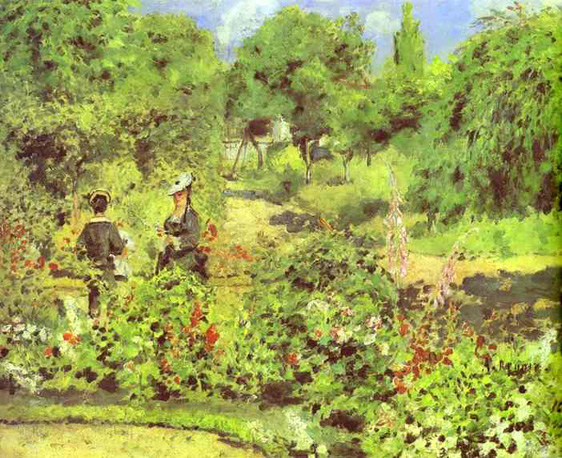

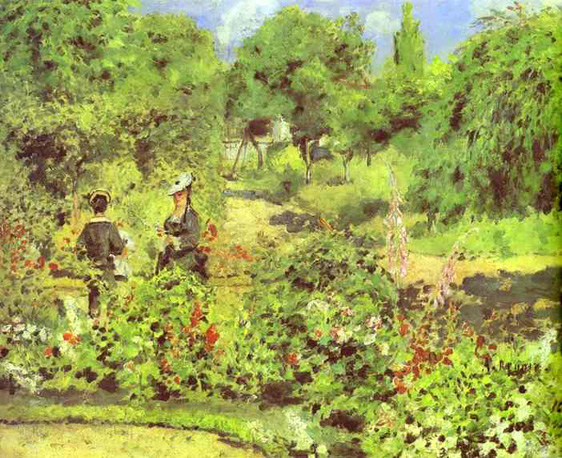

Garden at Fontenay: 1874

Garden Scene in Britanny: ca 1886

Girl with a Basket of Fish: ca 1889

Girl with a Basket of Oranges: ca 1889

Girl with a Fan

(Mlle Alphonsina Fournez): 1881

_1881.jpg)

Girl with a Hoop

(Marie Goujon): 1885

_1885.jpg)

On a trip to Italy in 1881, Renoir found new inspiration in the works of Renaissance artists, particularly Raphael, and developed a manner of painting he called "aigre," or "sour." The word conveys a sense of the hardness and tightness of his new style, exemplified by 'Girl with a Hoop', a portrait Renoir was commissioned to paint of a nine-year-old named Marie Goujon. The colors, though in some areas thickly applied, have a feeling of transparency. In her skin they are smoothly blended into a silky, almost liquid texture that seems to flow along the form. Brushstrokes are tight and firm; they have a smoothness like that of the girl's skin itself. The contours of her figure are crisply defined, almost as if they were outlined. In the background, elongated brushstrokes underscore this feeling of line. Compare these hard edges with the loose and sketchy impressionist style of 'Girl with a Watering Can', where the brushwork and image dissolve in prismatic color.

Girl with Brown Hair: 1887-1888

Guitar Lesson: 1897

Head of a Dog: 1870

Head of a Woman: ca 1876

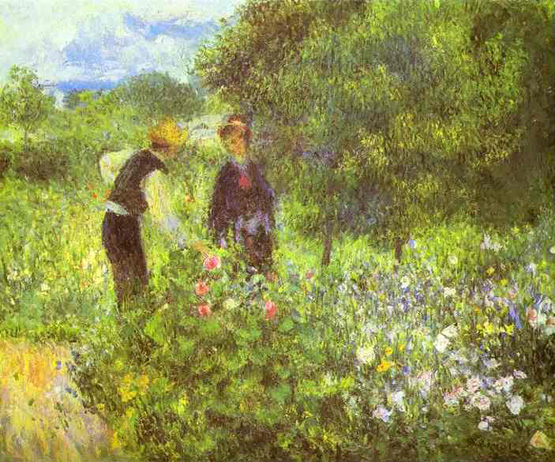

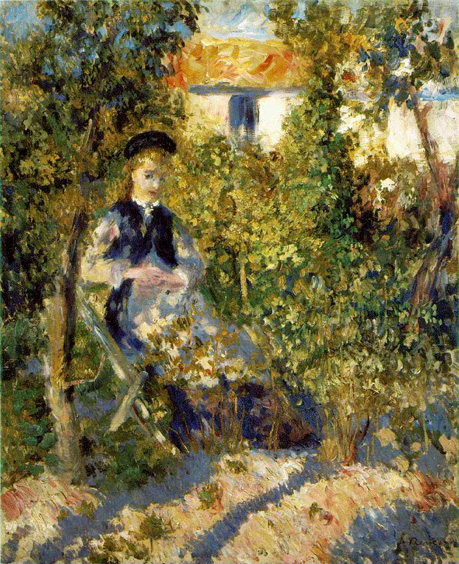

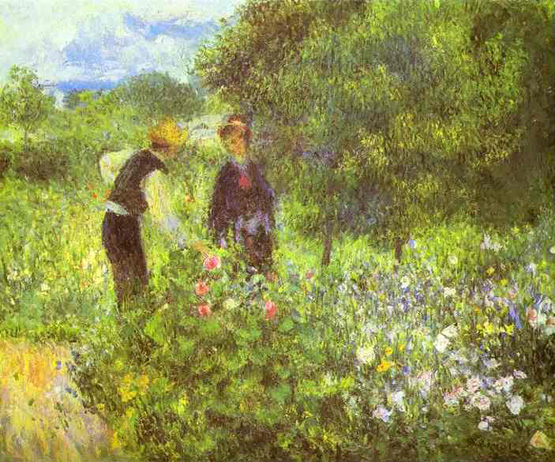

In the Garden: 1875

In the Garden

(Dans le jardin): ca 1885

_ca_1885.jpg)

In the Summer: 1868

La sortie du Conservatoire: ca 1876-1877

Lady in Black: 1876

Landscape: 1902

Landscape at Beaulieu

(Paysage a Beaulieu): 1899

_1899.jpg)

Landscape at Vetheuil: ca 1890

Landscape in Berneval with People

(Paysage a Berneval avec personnages): 1898

_1898.jpg)

Lise: 1867

Little Girl Gleaning: 1888

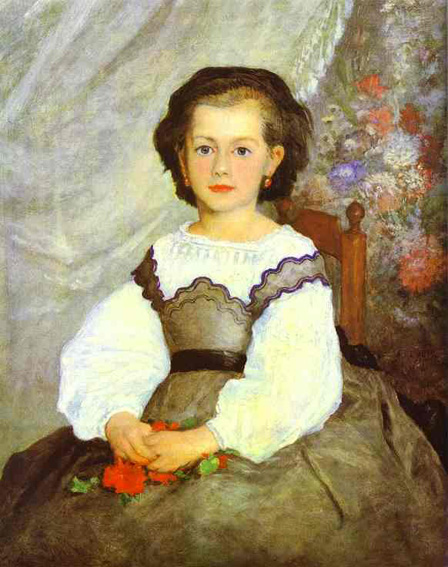

Little Miss Romaine Lacaux: 1864

Madame Charpentier: 1878

Madame Charpentier with Her Children: 1878

Madame Monet with Her Son: 1874

Madame Renoir with Bob: ca 1910

Man on a Staircase

(L Homme sur un escalier): ca 1876

_ca_1876.jpg)

Mlle Irene Cahen d Anvers: 1880

Mlle. Irene Cahen d’Andvers was the daughter of Cahen d’Anvers, a banker. The portrait was commissioned by her father.

Mme Monet Reading Le Figaro: 1872

Mother and Child: 1881

Mussel Collectors at Berneval

(Coast of Normandy): 1879

_1879.jpg)

Noirmoutier: 1892

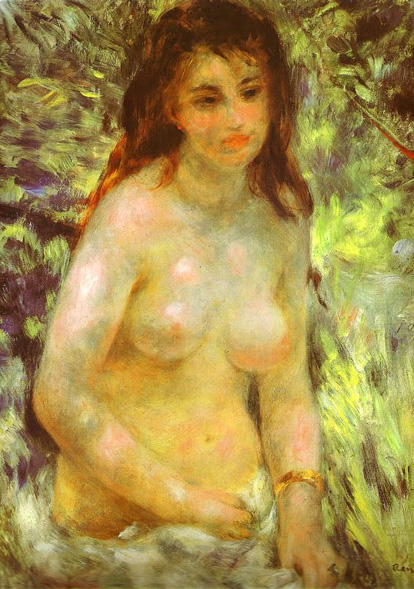

Nude: 1876

Nude: 1910

Nude in the Sunlight: 1875-1876

Oarsmen at Chatou: 1879

Ode to Flowers: 1909

On the Meadow: ca 1890

Pont Neuf Paris: 1872

Although he is best known for his figures, especially nudes, Renoir’s originality as a landscape painter was instrumental in the formation of impressionism. In paintings like this he transcribed the immediate and fleeting effects of light on the senses. We almost squint at these backlit forms. Figures are defined by a few quick strokes, and incidental details disappear in the glare of bright sun. The pavement is yellow with this light, brighter even than the sun-drenched sky. Shadows fall, not black or gray but in cool blue tones.

Among the energetic crowd crossing the Pont Neuf, the oldest bridge in Paris, one man appears twice. Sporting a straw boater and carrying the boulevardier’s cane, this is Renoir’s brother Edmond, dispatched by the artist to delay people on the street. Edmond later explained that while passersby paused to answer his idle questions, Renoir was able to capture their appearance from his window above a nearby Right Bank café.

Portrait of a Girl: 1890's

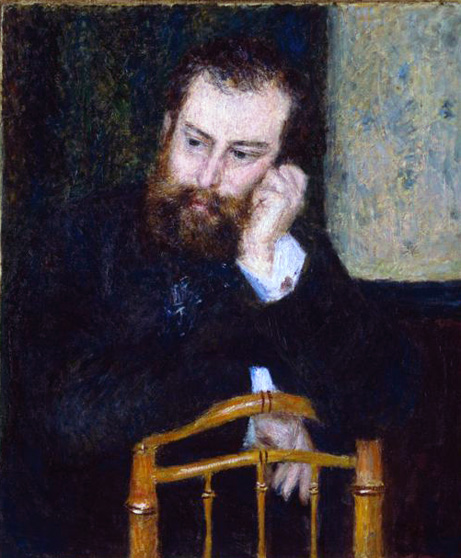

Alfred Sisley

Pierre Auguste Renoir and Alfred Sisley had known each other for more than ten years, having met in the studio of Charles Gleyre in 1862, when Renoir executed this portrait. Although the two men were of different backgrounds-Sisley came from a middle-class family and had initially intended to join his father's business, while Renoir, the son of a tailor and a dressmaker, had trained as an apprentice porcelain painter-they shared a passion for art. Renoir later recalled their student excursions to picturesque areas outside of Paris: "I would take my paint box and a shirt, and Sisley and I would leave Fontainebleau, and walk until we reached a village. Sometimes we did not come back until we had run out of money a week later."

In Renoir's portrait, Sisley sits casually astride a bamboo chair, resting his head on his left hand, his eyes lowered and gently averted. The shallow, dark room is pierced only by a window at the upper right. Although the composition's dominant tonality is blue, its mood is not melancholy; rather, Sisley appears thoughtful and serene, something of a dreamer. No clues, such as brushes or a palette, hint at his vocation, so perhaps Renoir intended to refer to his subject's identity as an artist more indirectly, through his romantic characterization.

This was one of six portraits that Renoir sent to the third Impressionist exhibition, held in 1877. The work can be seen as a document of the two men's shared aim, at this point in their careers, to achieve artistic success through avant-garde rather than official means, and of Renoir's specific aspiration to become known as a portrait painter. More importantly, however, its affectionate quality makes it a representation of friendship.

Madame Clapisson (Woman with a Fan): 1883

.jpg)

Woman at the Piano: 1875-76

Pierre Auguste Renoir was one of the most dedicated figure painters among the Impressionists. Enveloping his subjects, who were usually female, in an aura of fantasy and sensuality, he created a confident, immensely appealing art. Like Camille Corot, Mary Cassatt, and others, Renoir often painted women in domestic interiors, either daydreaming or reading. In this painting, he depicted for the first time a model playing the piano, a subject to which he would frequently return.

The setting is richly appointed, with a patterned carpet, fabric-covered walls, a potted plant, and luxurious curtains. A pretty, young woman sits before a piano, her luminous, pink hands caressing the keyboard. Her performance seems effortless, like her beauty, as if the ravishing visual harmony she embodies extends naturally into the realm of sound. Her dress is a confection of white, diaphanous fabric over a bluish under dress, offset by a winding, dark band; it takes on, through the magic of Renoir's brush, a life of its own, its brilliant play of chromatic harmonies and counterpoint of sinuous and cascading rhythms suggesting the notes produced by the instrument. Designed to conceal, the garment also reveals, as we see from the glints of pink flesh picked out on the musician's shoulder and arm.

Woman at the Piano is not a portrait of an individual, nor a study of a social type. It is a portrait of ideal womanhood, of a goddess transported from the heavens to a modern drawing room uncomplicated by the contingencies of the real world. The artist/performer is Renoir, the palette is his keyboard, and the woman at the piano is wholly his creation.

Jean Renoir Sewing: 1899

The Laundress: 1877-79

Portrait of a Woman (Mme Georges Hartmann): 1874

_1874.jpg)

Portrait of a Woman

(Portrait de femme): ca 1877

_ca_1877.jpg)

Portrait of a Woman: ca 1885

Portrait of Alphonsine Fournaise: 1879

Mlle. Alphonsine Fournaise, daughter of Le Pere Fournais, the owner of a small hotel and restaurant in Chatou, which Renoir frequented with his friends. Mlle. Fournais posed for Renoir in several paintings, including Le Grenoillère. Renoir painted The Luncheon of the Boating party, in which the Fournaise family are painted with their friends.

Portrait of Caroline Remy (Severine): ca 1885

_ca_1885.jpg)

Portrait of Charles Le Coeur: 1874

Portrait of Georges Riviere: 1877

Portrait of Georgette Charpentier on a Chair: 1878

Portrait of M and Mme Bernheim de Villers: 1910

Portrait of Madame Duberville with Her Son Henri: 1910

Portrait of Madame Hagen: 1883

Portrait of Madame Henriot: 1877

Portrait of Mademoiselle Sicot: 1865

Portrait of Marie Murer: 1877

Portrait of Mme Alphonse Daudet: 1876

Portrait of Mme Darras: ca 1873

Portrait of Mme Theodore Charpentier: ca 1869

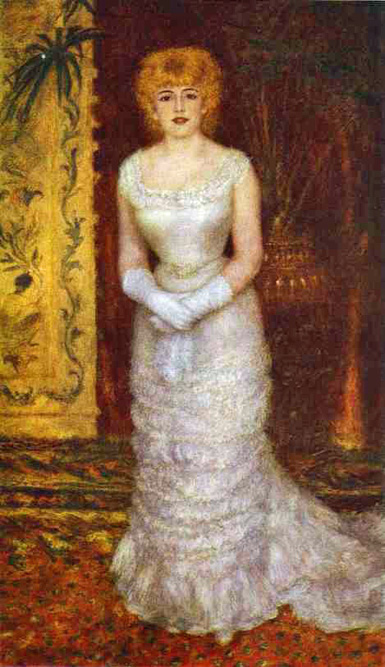

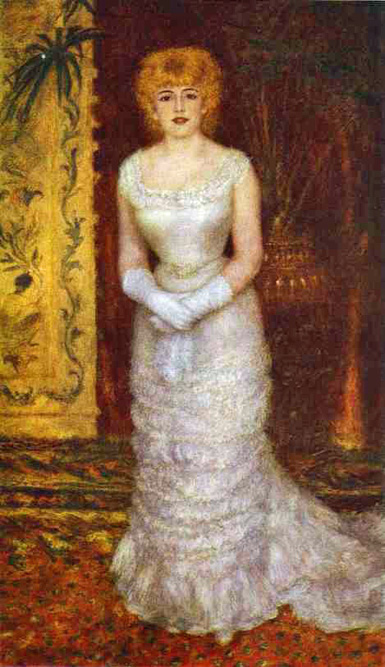

Portrait of the Actress Jeanne Samary: 1878

Portrait of the Actress Jeanne Samary: 1877

Portrait of the Actress Jeanne Samary - Comedie: 1877

Portrait of William Sisley: 1864

Railway Bridge at Chatou: 1881

Reading Children: 1883

Roses: 1890

Roses and Jasmin in a Delft Vase

(Les roses et jasmin dans le vase de Delft): ca 1880-81

_ca_1880_81.jpg)

Roses in a Vase: ca 1910-17

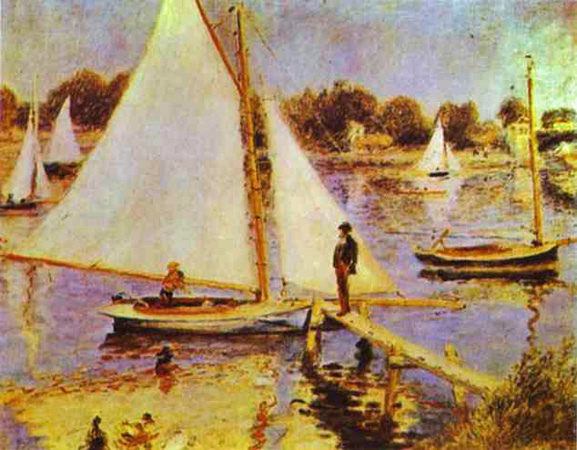

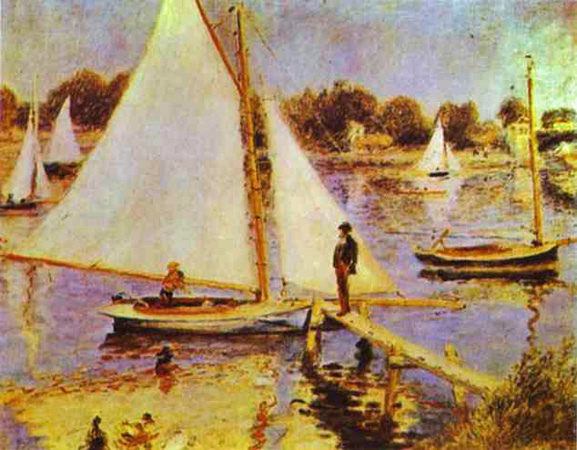

Sailboats at Argenteuil: 1874

Seated Bather: 1893

Seated Bather: 1914

Seated Young Girl

(Helene Bellon): 1909

_1909.jpg)

Seating Bather: 1903-1906

Seating Girl: 1883

Self Portrait: 1879

Self Portrait: 1910

Sleeping Odalisque

(Odalisque with Babouches): ca 1915-1917

_ca_1915_1917.jpg)

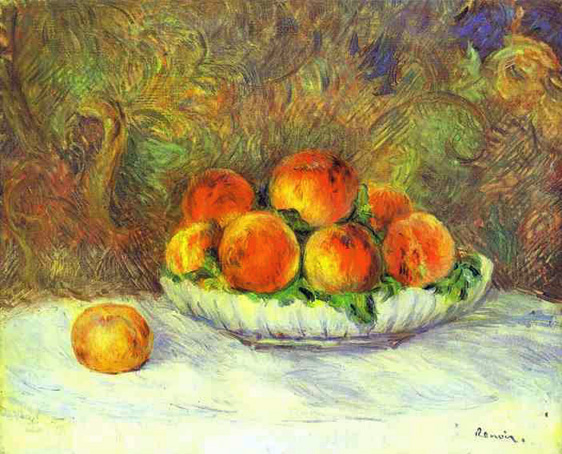

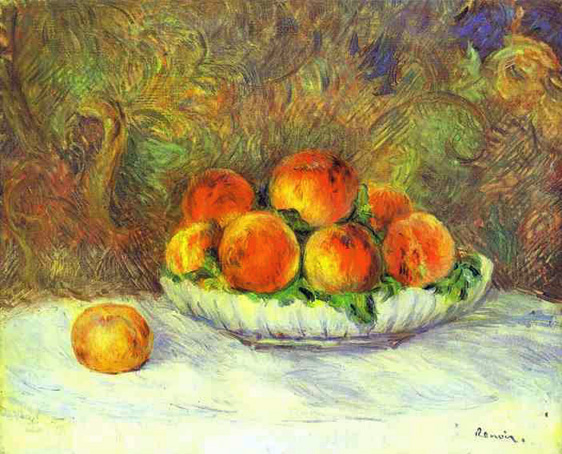

Still Life with Peaches: ca 1880

Study for The Bathers: ca 1884

Study of a Nude: ca 1910

The Bather: 1894

The Bather

(After the Bath): 1888

_1888.jpg)

The Bathers: ca 1918

The Bathing: 1894

The Clown

(Claude Renoir): 1909

_1909.jpg)

The Dancer: 1874

The Daughters of Catulle Mendes: 1888

The Family of the Artist: 1896

The First Outing: 1875-1876

The Great Boulevards: 1875

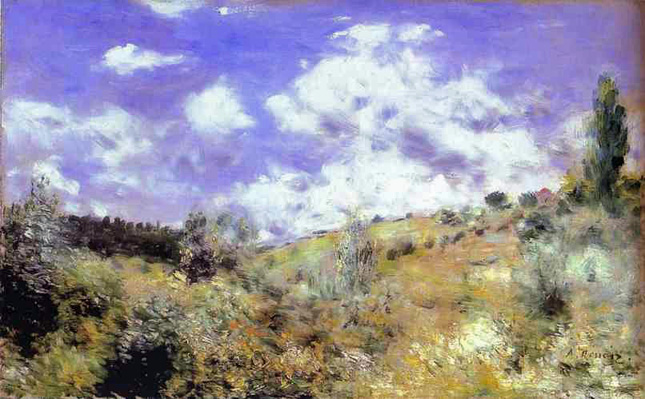

The Gust of Wind: ca 1872

The Laundress: 1877-79

The Lunch: ca 1879

The Luncheon of the Boating Party: 1879-80

The Mosque

(Arab Holiday): 1881

_1881.jpg)

The Parisienne: 1874

The Pont des Arts Paris: 1867

The Promenade: 1870

What Pierre-August Renoir himself titled this painting is unknown, but 'La Promenade' is in part an homage to earlier artists that he greatly admired. Renoir had spent the previous summer painting outdoors with Claude Monet, who encouraged him to move toward a lighter, more luminous palette and to indulge his penchant for luscious, feathery brushwork. Here Renoir retained something of Gustave Courbet's green-and-brown palette while choosing his subject from the sensual, lighthearted garden jaunts of eighteenth-century painters such as Jean-Antoine Watteau and Jean-Honoré Fragonard, whose works he had studied in the Louvre.

Unlike the images of seduction created by his predecessors, Renoir's is a fleeting moment caught by chance--middle-class Parisians immersed in nature, possibly a local park, not set before a studio backdrop. The dappled light filtering through the foliage would become a trademark of Renoir's finest Impressionist works of the 1870's and 1880's. He used a thin, oily paint mix, his glazes here floating into each other to create depth.

The Seine at Argenteuil: 1873

The Spring: ca 1895-97

The Toilet: ca 1900

The Toilette - Woman Combing Her Hair: ca 1907-1908

The Umbrellas: 1883

This picture, as well as being a delight in itself, illustrates a transitional aspect of Renoir's art. It shows a new attention to design as a well-defined scheme of arrangement, the umbrellas forming a linear pattern of a far from Impressionist kind, the linear element also being stressed in the young modiste's bandbox, the little girl's hoop and the umbrella handles. In this care for definite form, apparent also in the figures at the left, one can see a discontent with Impressionism and a search for a firmer basis of style that would date the work to about 1883-4, after his journeying abroad and the revision he brought into his ideas. It is unlikely that it preceded the Muslim Festival of 1881 and more probably represents a subsequent reaction.

The Cezanne-like treatment of the tree at the back also suggests it was painted after Renoir stayed with him at L'Estaque in 1882. The children and the lady with them are more indicative of the style of the 'seventies than the rest of the picture which may well have passed through stages of repainting over a period. The charm of the whole is nevertheless able to overcome the feeling of slight discrepancy that may result from close examination.

Durand-Ruel bought the picture from Renoir in 1892 and sold it to Sir Hugh Lane, in whose bequest it came to the Tate Gallery in 1917. It was transferred to the National Gallery in 1935.

The Vintagers: 1879

The Walk: ca 1906

The Washer Women: 1889

Two Girls in Black: ca 1881

Two Little Circus Girls: 1879

Two Women and a Child: 1912

Two Women with Umbrellas: 1879

View of Argenteuil: 1873

View of the New Building of the Sacre Cœur: ca 1896

Woman Combing Her Hair

(Femme se coiffant): ca 1887

_ca_1887.jpg)

Woman in a Boat: 1867

Woman in a Park: 1870

Woman in a Red Blouse: 1890-1895

Woman of Algiers: 1870

Woman on a Staircase

(Femme sur un escalier): ca 1876

_ca_1876.jpg)

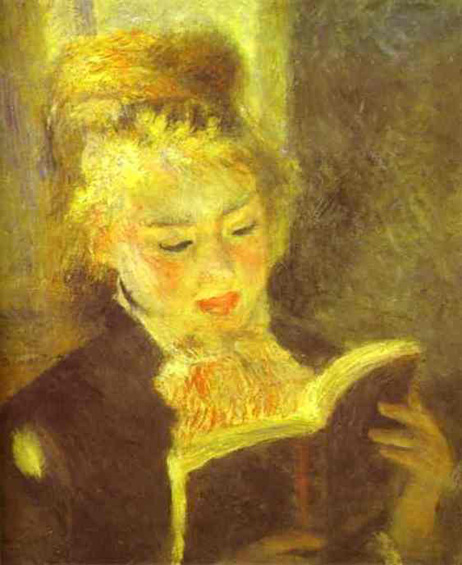

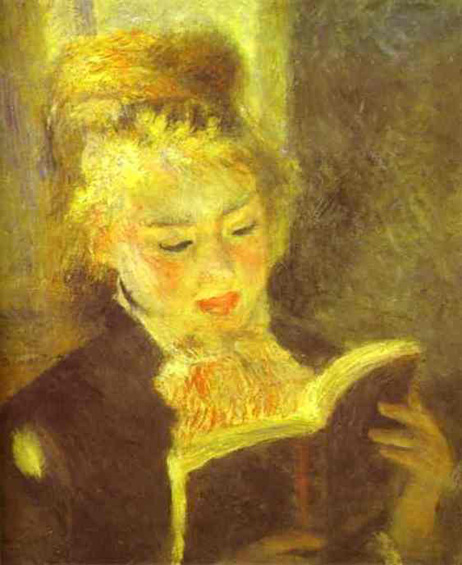

Woman Reading: 1875-1876

Woman Standing by a Tree: 1866

Woman with a Cat: ca 1875

Young Boy on the Beach of Yport

(Robert Nunes): 1883

_1883.jpg)

Young Girl Combing Her Hair: 1894

Young Girl Reading: 1886

Young Girl with a Rose

(Mme Colonna Romano): 1913

_1913.jpg)

Young Girl with Parasol

(Aline Nunes): 1883

_1883.jpg)

Young Spanish Woman with a Guitar: 1898

Young Woman Braiding Her Hair: 1876

Young Woman Wearing a Hat

(Jeune femme au chapeau): 1892-94

_1892_94.jpg)

Young Woman Wearing a Hat with Flowers

(Jeune femme au chapeau de fleurs): 1892

_1892.jpg)

Young Woman with a Veil: 1876

Young Woman with a Veil: ca 1878

Yvonne and Christine Lerolle Playing the Piano: 1897

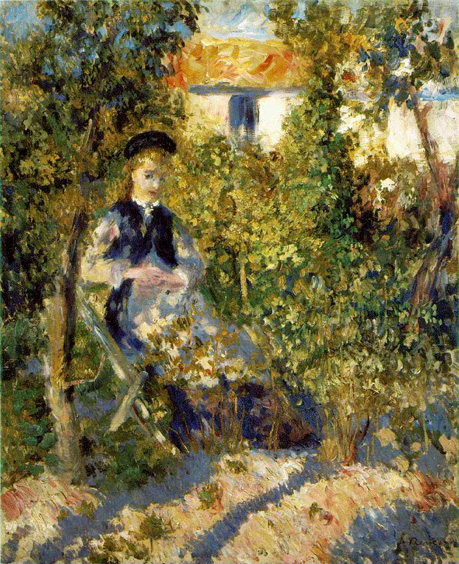

Nini in the Garden: 1876

Renoir rarely worked on one canvas at a time and 'Nini in the Garden', signed but not dated, belongs to the period immediately before work on the 'Moulin de la Galette' began in earnest. Inspired by Monet's work at Argenteuil, Renoir had been experimenting since the early 1870's with the motif of young women in the garden: in size and orientation, Nini in the Garden may be loosely grouped with 'Woman with a Black Dog', 1874 and the radiant Umbrella of 1878. These paintings are identical in size; each explores the problem of integrating the clothed female figure in ambient daylight and achieving a harmony between elegant 'Parisienne' and exuberant nature. Even more closely related is 'Young Girl on the Beach', which was probably painted at the same session: there, the model, Nini Lopez, sits on a similar garden chair wearing identical dress, but her presence is more assertive, now the chief element in the composition. Both paintings convey the delight that Renoir experienced in the large garden at the rue Cortot. Georges Riviere, who had accompanied Renoir in his search for the ideal Montmartre studio, recalled that "as soon as Renoir entered the house, he was charmed by the view of this garden, which looked like a beautiful abandoned park. Once we had passed through the narrow hallway, we stood before a vast uncultivated lawn dotted with poppies, convolvulus, and daisies." Beyond this, Riviere continued, lay a beautiful allee planted with trees stretching the full length of the garden--this was the view that Renoir used for his celebrated painting 'The Swing' (Musee d'Orsay, Paris)--and at the end was a fruit and vegetable patch with dense bushes and poplar trees. It is difficult to know exactly which corner of the garden is represented in this painting, although Nini does appear to be sitting at the edge of an untidy lawn.

In Nini in the Garden, which should be dated around 1875-76, Renoir's handling is energized, nervous, and experimental. He makes no attempt to unify the paint surface of his canvas: ridges of rich impasto sit alongside areas of barely covered ground. His color is nonetheless applied in dabs and strokes of varying touch, appropriate to the forms they describe. Thus, the leafy bushes in the background are a mosaic of greens, browns, and ochers; the sky in the upper left a series of blue strokes placed over the greens--the most obvious of Renoir's borrowings from Monet. Nini herself is painted more emphatically, the violet blue of her hat and underskirt the densest blocks of color in the composition. Nini's costume is very similar to, if not identical to, the one she wears in Departure from the Conservatory. Comparison helps establish the design of Nini's ensemble as it appears in Nini in the Garden: dark tunic over a light pinafore dress, with dark underskirt, this last element just visible through the grass and plants.

It is clear, however, that costume is of little concern to Renoir here. His chief interest is to record the sunlight as it filters through bushes and trees onto the diminutive and fashionably dressed Parisienne. He had already investigated these effects on the nude; Nini in the Garden marks an early stage in such treatment of the dressed figure. Somewhat tentatively, Renoir painted the reflections of foliage on Nini's face and the larger shadows on her dress. Her golden brown tresses are overwhelmed by the greens and browns of the background foliage; the forms of her dress dissolve in the dappled light and shadow.

Those elements of Renoir's luminist vocabulary that would cause such outrage in 1877--his colored shadows, the violet tonality of his outdoor scenes--are present in this early example: for example, the line of chartreuse that defines Nini's cheek and chin as well as the mauve patches of shadow on her dress. Although his plein-air painting still owed much to Monet, ... in the paintings he made in the garden of the rue Cortot, Renoir developed what Theodore Duret would consider his most striking contribution to Impressionism: depicting the human figure in the endlessly changing, mobile light of nature. Renoir's exploration of light dancing over the human figure would achieve full expression in 'The Swing and Moulin de la Galette'. In Nini in the Garden such effects are rendered a little hesitantly, but with the daring of experiment...

Source: Art Renewal Center

This page is the work of Senex Magister

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.

Viatores

Viatores

_1883.jpg)

_1883.jpg)

_1885.jpg)

_One_1887.jpg)

_Two_1887.jpg)

_1886.jpg)

_1883.jpg)

_1909.jpg)

_1909.jpg)

_1880.jpg)

_ca_1895_96.jpg)

_1870.jpg)

_ca_1909_13.jpg)

_ca_1883.jpg)

_1881.jpg)

_1885.jpg)

_ca_1885.jpg)

_1899.jpg)

_1898.jpg)

_ca_1876.jpg)

_1879.jpg)

.jpg)

_1874.jpg)

_ca_1877.jpg)

_ca_1885.jpg)

_ca_1880_81.jpg)

_1909.jpg)

_ca_1915_1917.jpg)

_1888.jpg)

_1909.jpg)

_1881.jpg)

_ca_1887.jpg)

_ca_1876.jpg)

_1883.jpg)

_1913.jpg)

_1883.jpg)

_1892_94.jpg)

_1892.jpg)