French Realist Painter and Designer

1819 - 1877

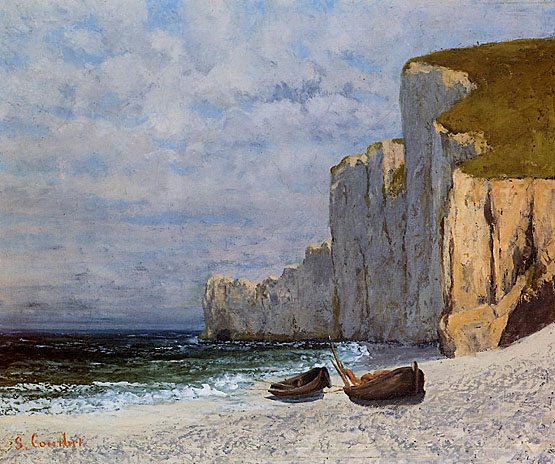

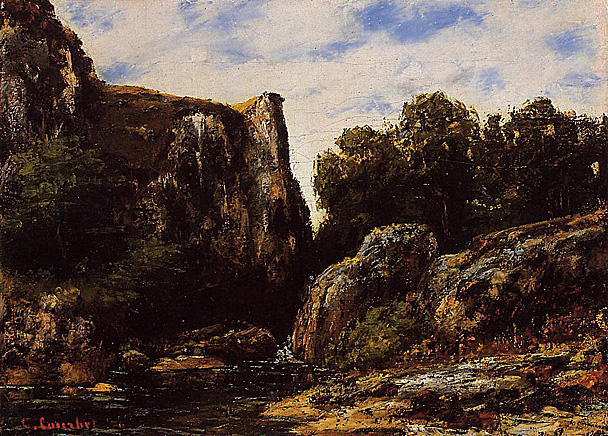

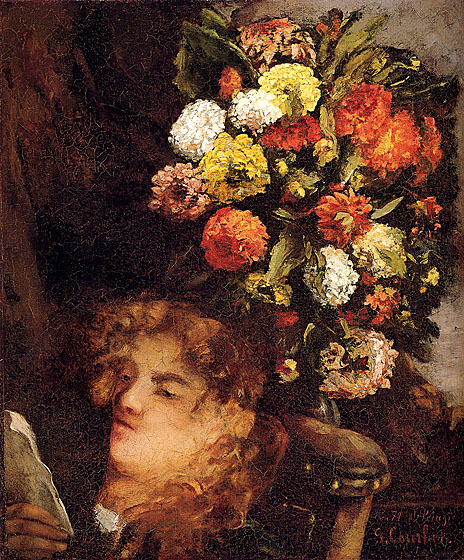

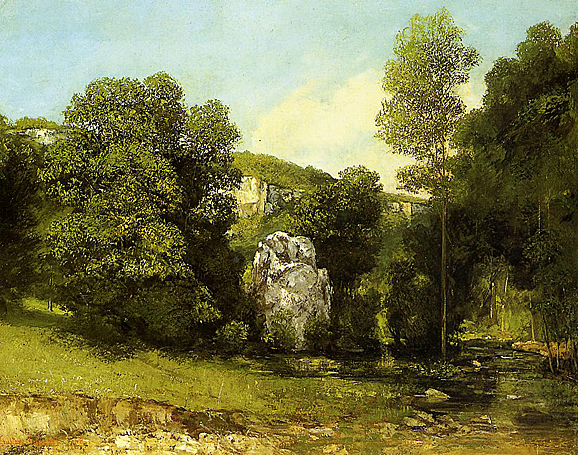

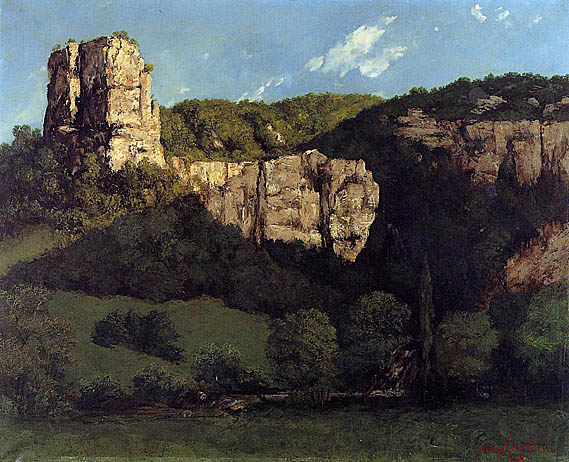

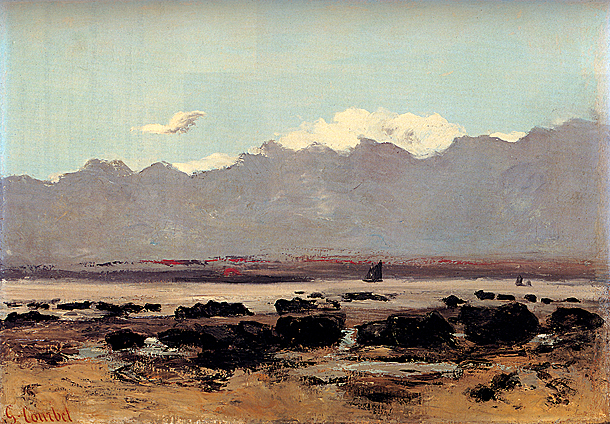

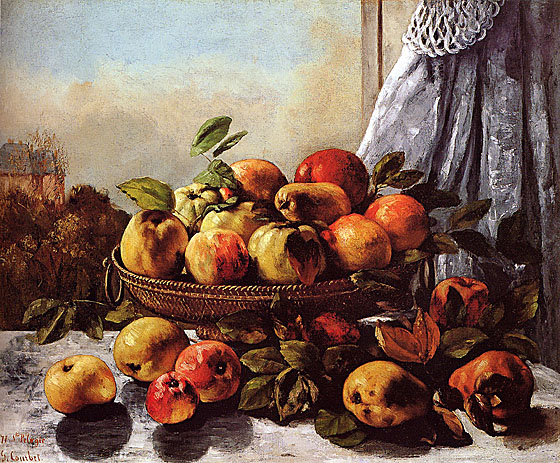

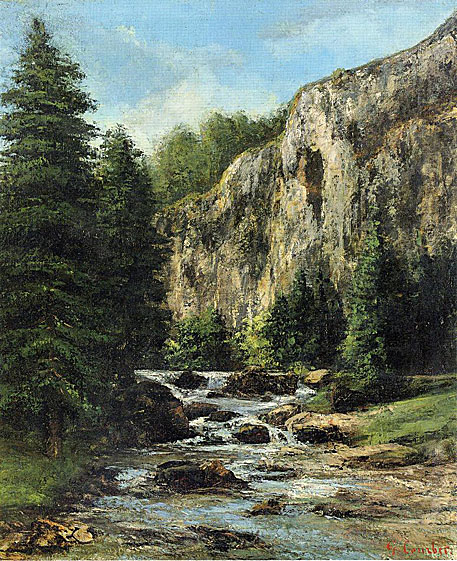

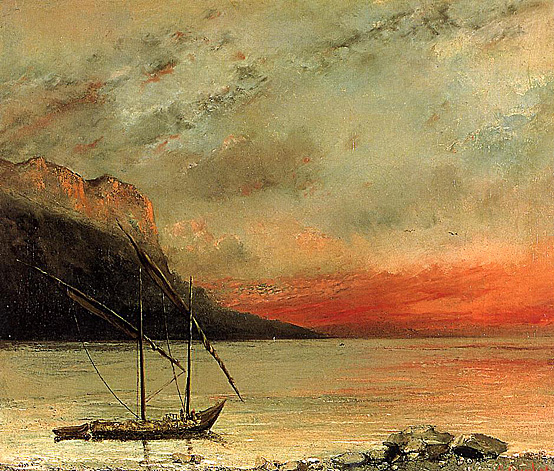

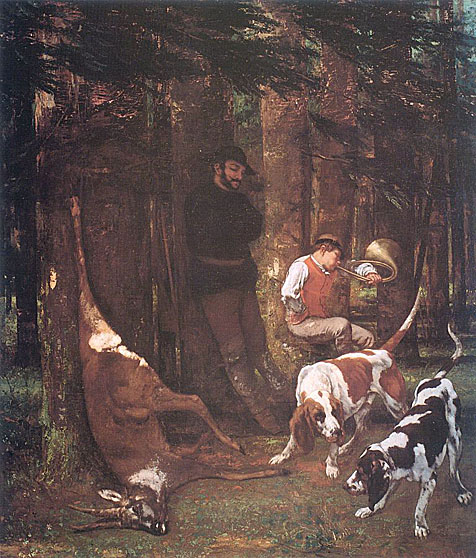

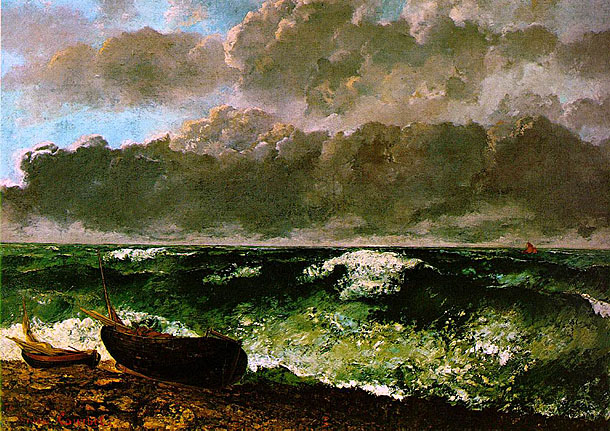

Best known as an innovator in Realism (and credited with coining the term), Courbet was a painter of figurative compositions, landscapes and seascapes. He also worked with social issues, and addressed peasantry and the grave working conditions of the poor. His work belonged neither to the predominant Romantic nor Neoclassical schools. Rather, Courbet believed the Realist artist's mission was the pursuit of truth, which would help erase social contradictions and abuses.

This painting, executed in 1855, is a replica of the original. Courbet, dissatisfied with the perspective, repainted the work and enlarged the canvas by some twelve inches along the right side. He also reworked the present canvas, as evidenced by his shift of the woman with the basket on her head from the right side of the composition (where traces of the basket are visible) toward the center.

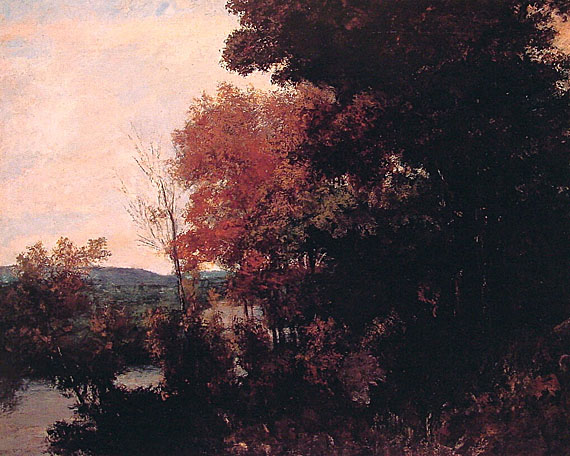

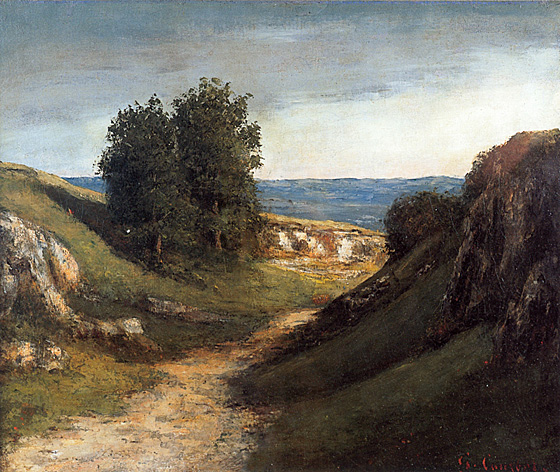

For Courbet realism dealt not with the perfection of line and form, but entailed spontaneous and rough handling of paint, suggesting direct observation by the artist while portraying the irregularities in nature. He depicted the harshness in life, and in so doing, challenged contemporary academic ideas of art, which brought the criticism that he deliberately adopted a cult of ugliness.

His work, along with the works of Honoré Daumier and Jean-François Millet, became known as Realism.

Born in Ornans (Doubs), into a prosperous farming family which wanted him to study law, he went to Paris in 1839, and worked at the studio of Steuben and Hesse. An independent spirit, he soon left, preferring to develop his own style by studying Spanish, Flemish and French painters and painting copies of their work.

His first works were an Odalisque, suggested by the writing of Victor Hugo, and a Lélia, illustrating George Sand, but he soon abandoned literary influences for the study of real life.

A trip to the Netherlands in 1847 strengthened Courbet's belief that painters should portray the life around them, as Rembrandt, Hals, and the other Dutch masters had done.

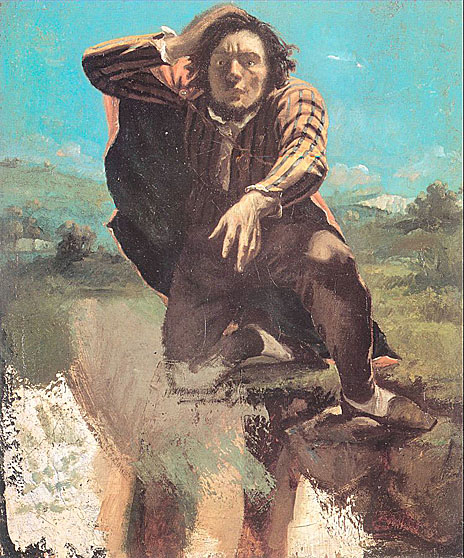

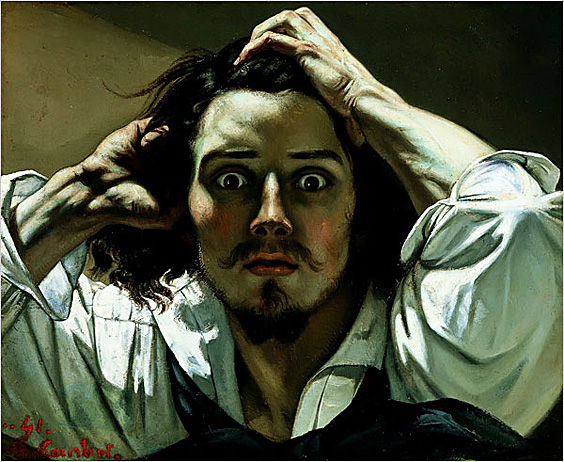

Among his early works, he painted his own portrait with his dog, and The Man with a Pipe, both of which the Paris Salon jury rejected. However, the younger critics, the Neo-Romantics and Realists, loudly sang his praises, and by 1849 Courbet was becoming well known, producing such pictures as After Dinner at Ornans (for which the Salon awarded him a medal) and The Valley of the Loire.

One of Courbet's most important works is Burial at Ornans, a canvas recording an event which he witnessed in September 1848. Courbet's painting of the funeral of his grand uncle became the first masterpiece in the Realist style. People who had attended the funeral were used as models for the painting. Previously, models had been used as actors in historical narratives; here Courbet said that he "painted the very people who had been present at the interment, all the townspeople". The result is a realistic presentation of them, and of life, in Ornans. The painting caused a fuss with critics and the public. It is an enormous work, measuring 10 by 22 feet depicting a prosaic ritual on a scale which previously would have been reserved for a religious or royal subject. Eventually the public grew more interested in the new Realist approach, and the lavish, decadent fantasy of Romanticism lost popularity. The artist well understood the importance of this painting; as Courbet said: "The Burial at Ornans was in reality the burial of Romanticism."

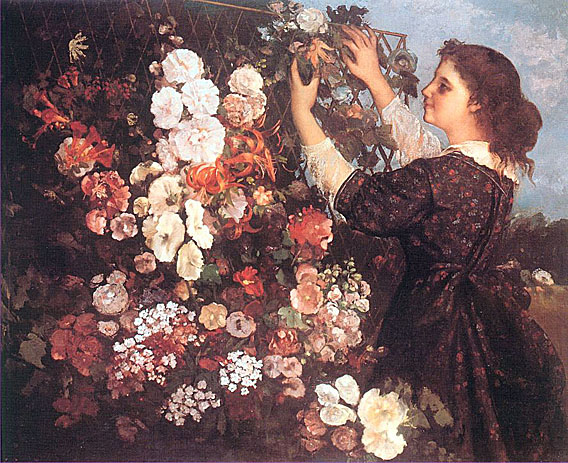

The Salon of 1850 found him triumphant with the Burial at Ornans, the Stone-Breakers (destroyed in 1945), and the Peasants of Flagey. Other figurative works, with common folk and friends as his subjects, included Village Damsels (1852), the Wrestlers, Bathers, and A Girl Spinning (1852).

The model for the standing bather has been identified as Henriette Bonnion, who, according to a nineteenth-century source, posed "in naturabilis " in Courbet's Paris studio in the winter of 1853. Bonnion also modeled for the photographer Julien Vallou de Villeneuve, assuming a nearly identical pose in a photograph of the same date. It is not known if the photograph was made before Courbet's painting.

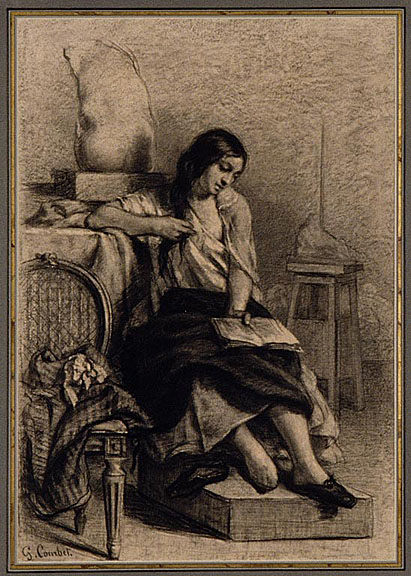

Proudhon also was delighted with the artist for having painted neither a goddess, nor a Greek, nor a fashionable doll, nor a Florian shepherdess, but a really "physiological beauty, full-blooded, alive, strong and tranquil." With many philosophical divagations he admires the "magnificent creature . . . , the thread has fallen from her hand. Almost we can hear her slow breathing instead of the whirring of the wheel. Every day she rises early in the morning; she is the last to go to bed . . . It is in her spare moments that she takes her distaff, and turns to the gentle slow work, the slight noise of which is not enough to keep her, healthy countrywoman that she is, awake. Do you understand now why Courbet made his spinner a mere peasant? There would be no sense in her otherwise; more than that, I say she would be indecent . . . Only the truth, discarding every impure thought, could here suggest both an idea and an ideal, without which art is reduced to arbitrariness and insignificance and disappears."

"La Fileuse" has often been shown in public, notably at the Universal Exhibition of 1855 and the private exhibition of 1867. It was given by Bruyas to the Montpellier Museum.

Courbet associated his ideas of realism in art with Socialism, and, having gained an audience, he promoted democratic and Socialist ideas by writing politically motivated essays and dissertations.

To a friend in 1850 he wrote:

He displayed his monumental The Artist's Studio in 1855. It is an allegory of his life as a painter, seen as a heroic venture, in which he is surrounded by friends and admirers, among them Charles Baudelaire.

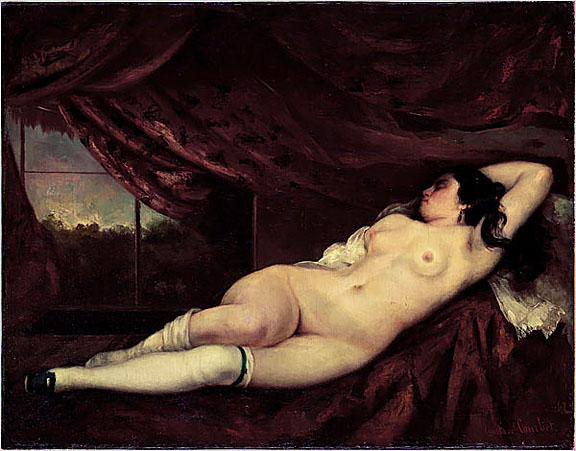

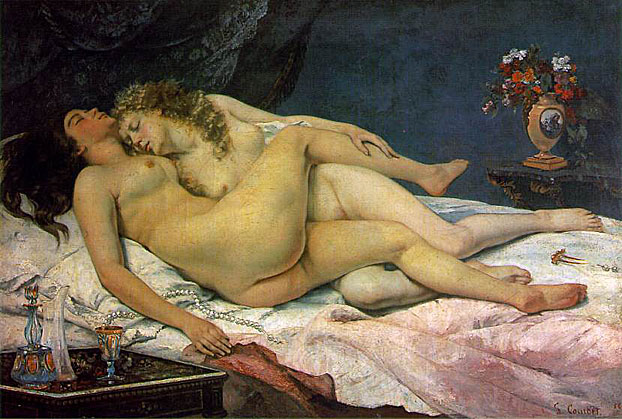

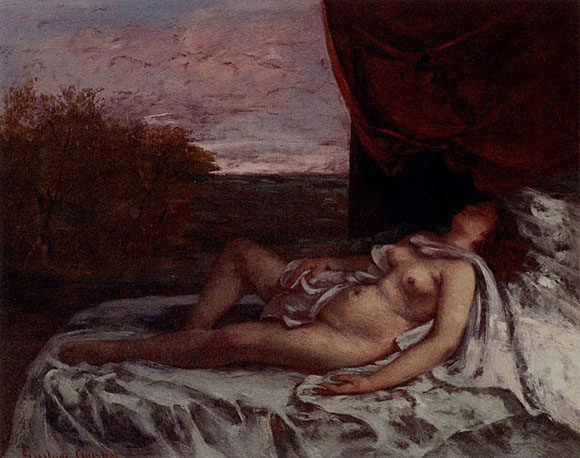

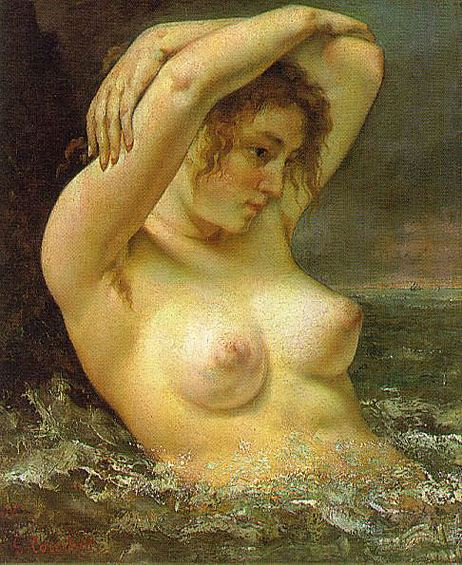

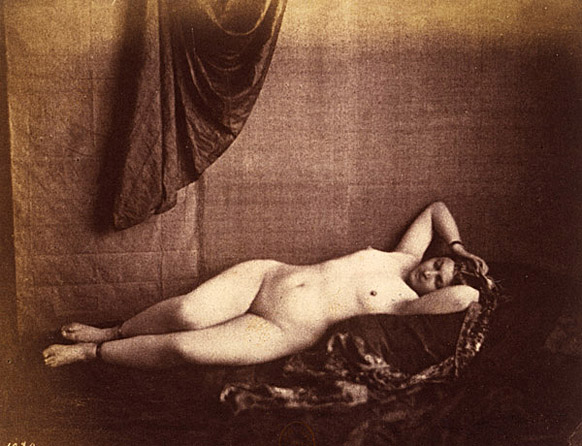

Towards the end of the 1860's, Courbet painted a series of increasingly erotic works such as Femme nue couchée. This culminated in The Origin of the World (L'Origine du monde) (1866), depicting female genitalia, and Sleep (1866), featuring two women in bed. While banned from public display, the works only served to increase his notoriety.

During the 19th century, the display of the nude body underwent a revolution whose main activists were Courbet and Manet. Courbet rejected academic painting and its smooth, idealized nudes, but he also directly recriminated the hypocritical social conventions of the Second Empire, where eroticism and even pornography were acceptable in mythological paintings.

Courbet later insisted he never lied in his paintings, and his realism pushed the limits of what was considered presentable. With L'Origine du monde he has made even more explicit the eroticism of Manet's Olympia. Maxime Du Camp, in a harsh tirade, reported his visit of the work's purchaser, and his sight of a painting "giving realism's last word".

The commission for L'Origine du monde is believed to have come from Khalil-Bey, a Turkish diplomat, former ambassador of the Ottoman Empire in Athens and Saint Petersburg who had just moved to Paris. Sainte-Beuve introduced him to Courbet and he ordered a painting to add to his personal collection of erotic pictures, which already included Le Bain turc (The Turkish Bath) from Ingres and another painting by Courbet, Les Dormeuses (The Sleepers), for which it is supposed that Hiffernan was one of the models.

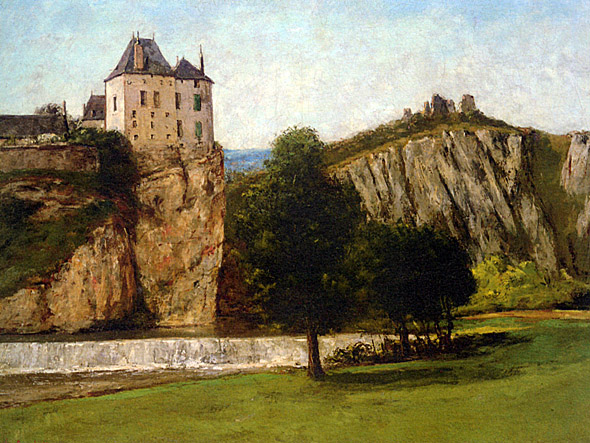

After Khalil-Bey's finances were ruined by gambling, the painting subsequently passed through a series of private collections. It was first bought during the sale of the Khalil-Bey collection in 1868, by antique dealer Antoine de la Narde. Edmond de Goncourt hit upon it in an antique shop 1889, hidden behind a wooden pane decorated with the painting of a castle or a church in a snowy landscape. According to Robert Fernier, Hungarian collector Baron Ferenc Hatvany bought it at the Bernheim-Jeune gallery in 1910 and took it with him to Budapest. Towards the end of the Second World War the painting was looted by Soviet troops but ransomed by Hatvany who when he emigrated was allowed to take only one art work with him, and he took L'Origine to Paris.

In 1955 L'Origine du monde was sold at auction for 1.5 million francs. Its new owner was the psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan. Together with his wife, actress Sylvia Bataille, he installed it in their country house in Guitrancourt. Lacan asked André Masson, his stepbrother, to build a double bottom frame and draw another picture thereon. Masson painted a surrealist, allusive version of L'Origine du monde. The New York public had the opportunity to admire L'Origine du monde in 1988 during the Courbet Reconsidered show at the Brooklyn Museum; the painting was also included in the exhibition Gustave Courbet at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2008. After Lacan died in 1981, the French Minister of Economy and Finances agreed to settle the family's inheritance tax bill through the transfer of the work (dation en lieu in French law) to the Musée d'Orsay, an act which was finalized in 1995.

On 14 April 1870, Courbet established a "Federation of Artists" (Fédération des artistes) for the free and uncensored expansion of art. The group's members included André Gill, Honoré Daumier, Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot, Eugène Pottier, Jules Dalou, and Édouard Manet.

His refusal of the cross of the Legion of Honour offered to him by Napoleon III made him immensely popular with those who opposed the current regime, and in 1871 under the revolutionary Paris Commune he was placed in charge of all the Paris art museums and saved them from looting mobs. For his insistence in executing the Communal decree for the destruction of the Vendôme Column, he was designated as responsible for the act and accordingly sentenced on 2 September 1871 by a Versailles Court Martial to six months in prison and a fine of 500 francs.

In 1873, the newly elected president Mac-Mahon wanted to resurrect the Column, and Courbet was singled out to pay the expenses. He then took refuge in Switzerland to avoid bankruptcy. On 4 May 1877, the estimate of the costs was finally established: 323,091 fr 68 cent. Courbet was allowed to pay the fine in yearly installments of 10,000 francs for the next 33 years, until his 91st birthday.

Courbet died, age 58, in La Tour-de-Peilz, Switzerland, of a liver disease aggravated by heavy drinking on 31 December 1877, a day before the payment of the first installment was due.

Courbet's particular kind of realism influenced a number of artists to follow, notably among them, Edward Hopper. Symbolically, Hopper's "Bridge in Paris" (1906) and "Approaching a City" (1946) in particular, seem Freudian echoes of Courbet's "The Source of the Loue" and "The Origin of the World. " Hopper's "Les Deux Pigeons" (1920) is "infused with the spirit of Courbet. Lovers on a terrace ardently embrace while the river flows freely through the forest below them."

Senex Magister

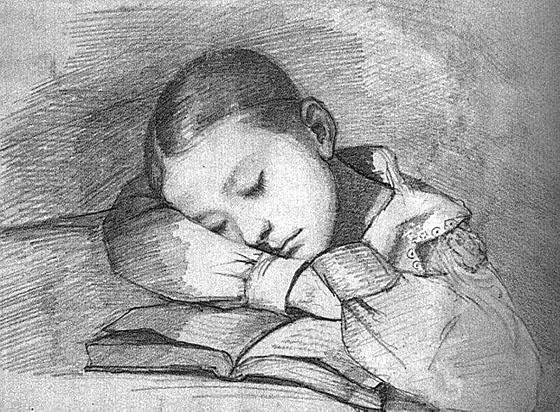

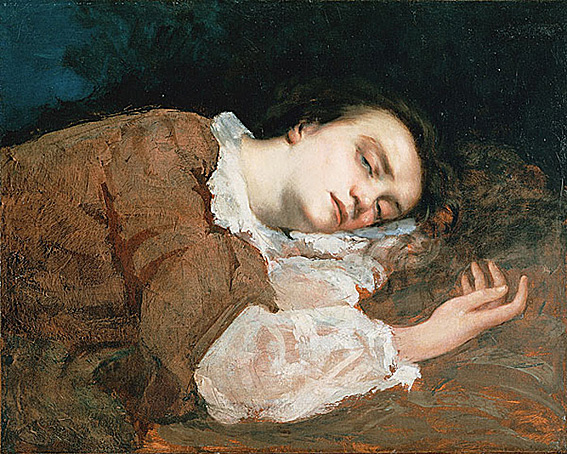

In 1854, already taking a retrospective look at his oeuvre, Courbet wrote to Alfred Bruyas, his patron in Montpellier: "During my life, I have painted myself many times, whenever my state of mind changed. In short, I have written the story of my life". The Wounded Man subscribes to this subjectivity by investing the romantic theme of the artist made heroic by suffering. The picture painted in 1844 was reworked by Courbet ten years later, at the end of a love affair. The woman, who was originally leaning on the artist's shoulder, has been replaced by a sword and Courbet has added a red bloodstain on his shirt over his heart. The artist has ambiguously and seductively combined the most intimate autobiographical register (by evoking a duel) with a death struggle confused with the sensual abandonment of sleep.

Source: Art Renewal Center

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.