Disclaimer

Francois Boucher

French Rococo Painter

1703 - 1770

Portrait of Francois Boucher

By Gustav Lundenberg

Francois Boucher was a French painter, a proponent of Rococo taste, known for his idyllic and voluptuous paintings on classical themes, decorative allegories representing the arts or pastoral occupations, and intended as a sort of two-dimensional furniture. He also painted several portraits of his illustrious patroness, Madame de Pompadour.

Madame de Pompadour

Although Boucher served the rococo movement well, it was essentially through the exercise of conscious fancy rather than any profoundly imaginative impulse. He was capable of painting straightforward genre scenes and portraits soberly realistic. All his portraits of Madame de Pompadour are characterized by equal directness and emphasis upon spontaneity. He placed her reading, reclining, seizing a hat before going for a walk, and not only in natural poses but in a natural, half-rural setting. Simply dressed and well equipped with books, she pauses in her reading to listen to a bird singing, in a wonderful woodland of velvet moss and silken foliage. This is a portrait artificial only in the way that Watteau and Gainsborough were artificial. It is utterly simple in concept, even anti-rococo, when compared with the high court portraiture of Nattier.

Born in Paris, the son of a lace designer Nicolas Boucher, Francois Boucher was perhaps the most celebrated decorative artist of the 18th century, with most of his work reflecting the Rococo style. At the young age of 17, Boucher was apprenticed by his father to Francois Lemoyne, however after only 3 months he went to work for the engraver Jean-Francois Cars. Within 3 years Boucher had already won the elite Grand Prix de Rome, although he did not take up the consequential opportunity to study in Italy until 4 years later. On his return from studying in Italy in 1731, he was admitted to the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture as a historical painter, and became a faculty member in 1734.

His career accelerated from this point, as he advanced from professor to Rector of the Academy, becoming head of the Royal Gobelin factory in 1755 and finally Premier Peintre du Roi (First Painter of the King) in 1765.

Reflecting inspiration gained from the artists Watteau and Rubens, Boucher's early work celebrates the idyllic and tranquil, portraying nature and landscape with great élan. However, his art typically forgoes traditional rural innocence to portray scenes with a definitive style of eroticism, and his mythological scenes are passionate and amorous rather than traditionally epic. Marquise de Pompadour (mistress of King Louis XV), whose name became synonymous with Rococo art, was a great fan of Boucher's, and it is particularly in his portraits of her that this style is clearly exemplified.

The Afternoon Meal: 1739

A diagonal light casts strong shadows on the intimate urban scene in a richly decorated room. It is supposed that the figures represent the artist's family.

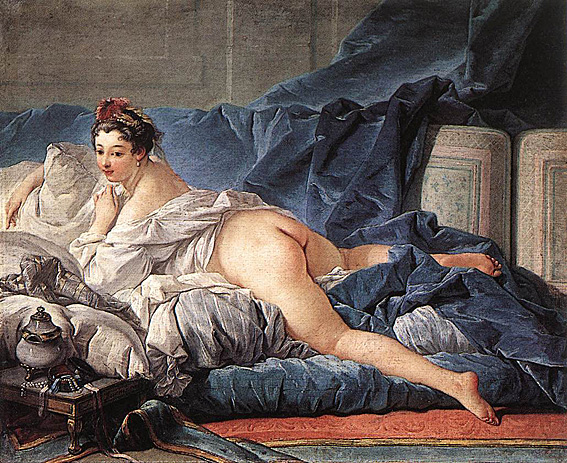

Paintings such as The Breakfast of 1739, a family scene, also show Boucher as a master of the genre scene, as he regularly used his own wife and family as models. These intimate family scenes are, however, in contrast to the 'licentious' style, as seen in his Odalisque portraits. The dark-haired version of the Odalisque portraits prompted claims by Diderot that Boucher was "prostituting his own wife" and the Blonde Odalisque was a portrait that illustrated the extramarital relationships of the King. Boucher gained lasting notoriety through such private commissions for wealthy collectors and, after the ever-moral Diderot expressed his disapproval, his reputation came under increasing critical attack during the last of his creative years.

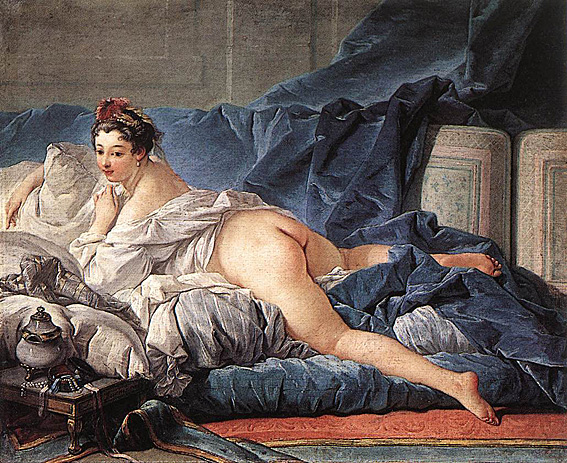

Brown Odalisque (L'Odalisque Brune): 1745

It can be assumed that the painting represents Madame Boucher, the artist's wife.

Along with his painting, Boucher also designed theatre costumes and sets, and the ardent intrigues of the comic operas of Favart (1710-1792) closely parallel his own style of painting. Tapestry design was also an interest and major activity of his, together with his design activities for the opera and the royal palaces of Versailles, Fontainebleau and Choisy.

Neoclassicist Jacques-Louis David began his painting instruction under Boucher.

Boucher is famous for saying that the natural world was "trop verte et mal eclaire" (too green and badly lit).

Francois Boucher died on May 30, 1770 in Paris, France. His name, along with that of his patron Madame de Pompadour, had become synonymous with the French Rococo style, leading the Goncourt brothers to write: "Boucher is one of those men who represent the taste of a century, who express, personify and embody it."

Rinaldo and Armida

The subject was inspired by the 16th-century epic poem 'Gerusalemme Liberata' (Jerusalem Delivered) by Torquato Tasso (1544-95). Rinaldo and Armida are a pair of lovers in the poem which is an idealized account of the first Crusade which ended with the capture of Jerusalem in 1099 and the establishment of a Christian kingdom. Armida, a beautiful virgin witch, had been sent by Satan (whose aid the Saracens had enlisted0 to bring about the Crusaders' undoing by sorcery. She sought revenge on the Christian prince Rinaldo after he had rescued his companions whom she had changed into monsters. The pastoral story of hate turned of love, of the lovers' dalliance in Armida's magic kingdom, and Rinaldo's final desertion of her, forms a sequence of themes that were widely popular with Italian and French artists in the 17th and 18th centuries.

The artist was admitted to the Academy by presenting this painting.

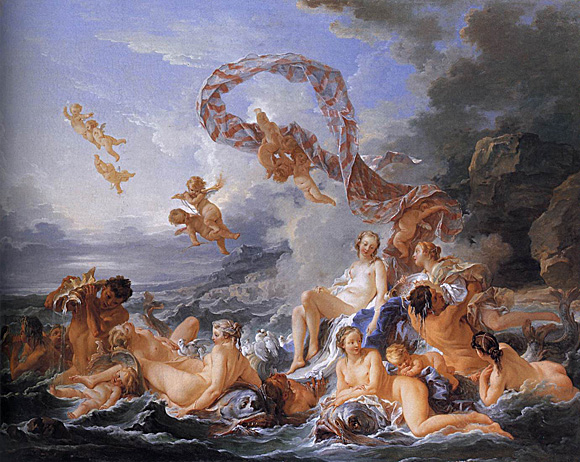

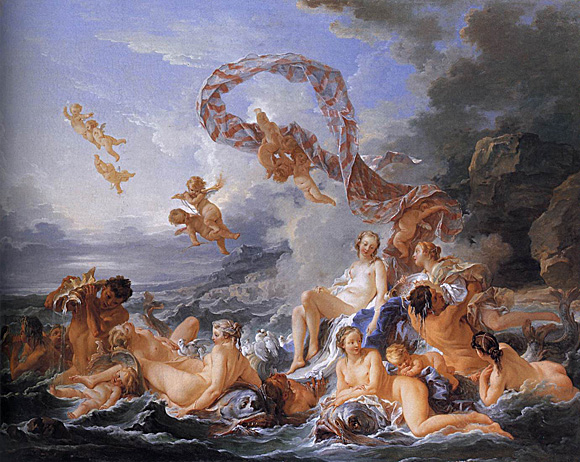

The Birth of Venus: 1740

The Birth of Venus is the quintessence of Boucher's aims, blending the natural and the artificial to make a completely enchanted scene, exuberant and yet relaxed, an aquatic frolic and yet also an air-borne, sea-borne, vision which has authentic pagan feeling. It is a glimpse to make anyone less forlorn as these creatures rise dripping from the waves. The green water itself becomes an exciting erotic element as it swells and falls, bearing up the pearl-pale bodies that abandon themselves to it and offer their limbs like branches of white coral as perches for Venus's doves. In place of Tiepolo's romantic nobility there is a human simplicity. Despite the snorting dolphins and having Tritons, the tumbling putti and the tremendous twist of silver and salmon-pink striped awning, the goddess remains a ravishingly pretty., demure girl, half-shy of the commotion of which she is the centre. She, like the nymphs around her, is reality idealized, divinely blonde and slender, touched with a voluptuous vacancy, a lack of animation, which perhaps only increase her charm. The insolent consciousness of Tiepolo's people is replaced here by innocence bordering on stupidity; herself so desirable, the goddess seems without desires. Boucher keeps much closer than Tiepolo to the terms of ordinary experience; his idealizing touches are restricted to the refining of ankles and wrists, perfecting of the arc of the eyebrows, tinting a deeper red the lips and nipples. Both artists can be related to the sculpture of their period. Boucher belongs with the naturalistic nude statuettes of Falconet and Clodion; Tiepolo has much more in common with the extremes of gilded and rouged Bavarian rococo sculpture.

Chinese Dance: 1742

The fashion of "chinoiserie" was associated with Rococo in France, and in other countries including England and Holland, which were major importers of porcelain figures and exotic screens. Lacquered and ceramic objects popularized such motifs, as did tapestries. Boucher's Chinese Dance is a cartoon for The Chinese Tapestry woven at Beauvais in 1743.

La Peche chinoise: 1742

Boucher was employed on tapestry design for the Beauvais factory. He produced for Beauvais his enchanting Chinese subjects ('sujet chinois'), decorative, flippant and deft, presenting palm trees, doll-like people, feathery hats, suggesting a generalized, amusing exoticism. One of the most delightful of this set is La Peche chinoise (The Chinese Fishing).

The Education of Cupid: 1742

In this painting Boucher presents the mythological family where mother Venus and father Mercury are captured in a moment of parental responsibility. As Messenger of the Arts, Mercury seems to be instructing his offspring in lessons of love, catching Venus's eye in a moment of romantic encounter. The love goddess is shown in a typically Boucheresque "bottoms-up" pose.

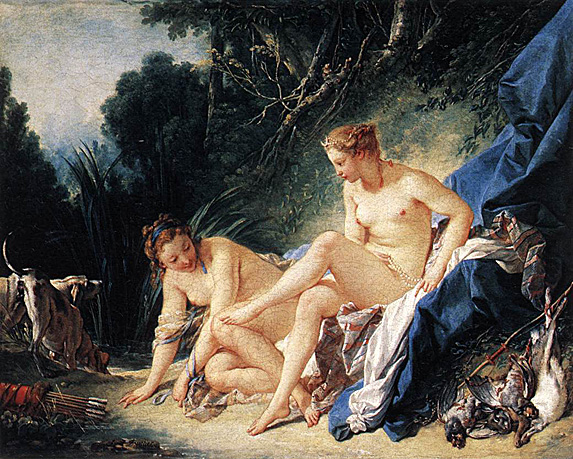

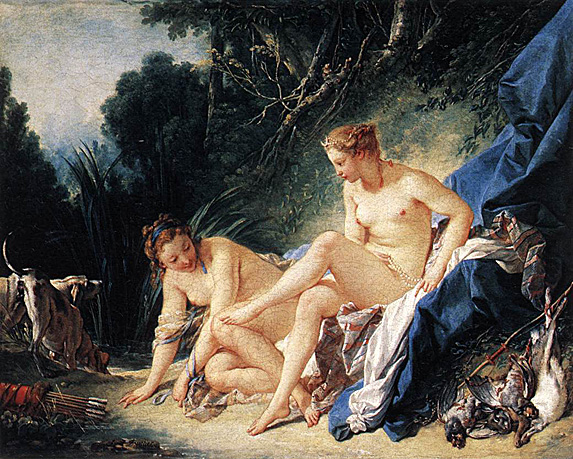

Diana Resting after her Bath: 1742

Diana Resting (Detail)

This painting is unquestionably Boucher's masterpiece. As a decorative artist, Boucher had amazing facility; in this painting, done for the Salon in 1742, he wished to excel himself. It places him in the ranks of the great masters, and on looking at it one begins to realize how gifted he was, even though he did not always make full use of his talent.

The slender nudes and the hunting theme recall the School of Fontainebleau, of which certain traditions persist in the eighteenth century. The paint surface is intact, and the old varnish, which contains no artificial coloring, gives it a slightly golden tone.

The painting is a masterpiece in the true classical manner; the technique is not too obvious, all the values are harmoniously balanced, and the elegance of the drawing and the purity of the forms are more important than the more sensual charms of color.

Diana after the Hunt

Tiepolo's chilly women are stripped by Boucher to complete nudity, warmed by love or lust, and made always girls before they are goddesses. The trappings of mythology are increasingly only different wrappings for the same offering, guaranteed not to interfere with contemplation of the woman even if she is supposed to be Diana after the Hunt. Thus, while the stage is equipped with false trees or false doves, truth is present in the observation of naked bodies, draperies that set them off, and - most caressingly - in the texture of flesh conveyed by paint.

The Forest: 1740

Boucher's pastorals and landscape paintings, which are certainly part of his rococo achievement, are willfully artificial on a basis of real observation. They create a new branch of rococo art in which the growing tendency to shake off dynastic and mythological duties has been completely developed; they are stage settings without characters, or with at most some actor-peasants, in which nature is dressed alluringly as Venus had been undressed.

Perhaps Boucher's most enchanted landscapes are those where the stage is set but the characters hardly appear: a rural dream of tranquil nature where man has added only picturesque water wheels, some cottages and a few inevitable doves, and where the taffeta grass, the blue trees, and the pale stretched silk sky create an ingenious, impossible Arcadia more beautiful than any reality. By the mid-1750's Gainsborough in England was achieving similar effects, blending French elegance with native facts and producing idyllic landscapes, often with courting woodcutters and milkmaids.

Are They Thinking About the Grape? - 1747

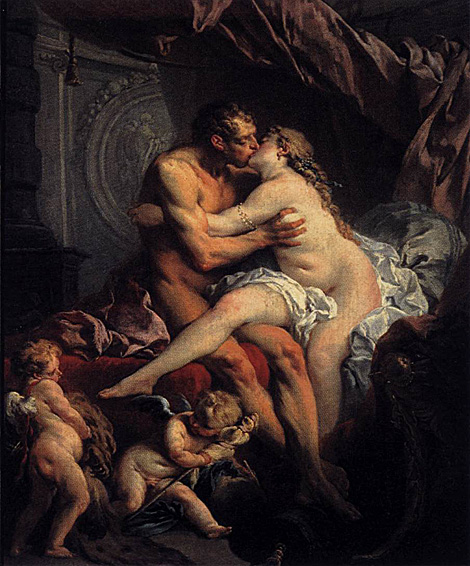

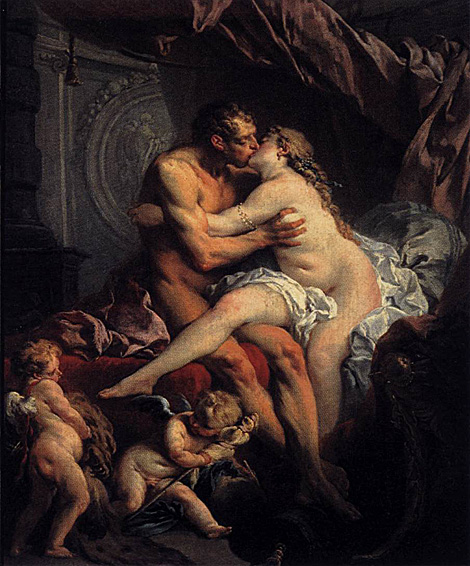

Hercules and Omphale: 1735

The mythological story depicted in the painting is the following:

For murdering his friend Iphitus in a fit of madness Hercules was sold as a slave to Omphale, queen of Lydia, for three years (Apollodorus 2.6:3). But she soon alleviated his lot by making him her lover. While in her service he grew effeminate, wearing women's clothes and adornments, and spinning yarn.,P.

The subject, portraying one of the hero's errors, inspired Boucher to paint one of the most audaciously erotic and best-executed canvases of the century - an agitated, brilliant composition full of wit and joyous verve, which Boucher would only rarely equal afterward.

Madame Boucher: 1743

This painting probably represents the wife of the artist. It is well-known that in some of his paintings Boucher gracefully transmuted his childishly pretty wife into goddess or nymph, but he also painted an almost satirically pointed portrait of a woman who is probably she, as she and her untidy ambient really were.

The Milliner (The Morning) - 1746

The painting, commissioned by Count Tessin, the ambassador of Switzerland, is part of a series of four representing morning, noon, afternoon and night, respectively.

Painter in his Studio

An Autumn Pastoral: 1749

This painting and its companion piece, A Summer Pastoral (also in the Wallace Collection), were commissioned by the financier Trudaine for his new chateau at Montigny-Lencoup, together with four overdoors by Oudry which are also in the Wallace Collection.

These great pastorals offer a characteristic Boucher blend of elegance and rusticity.

A Summer Pastoral: 1749

This painting and its companion piece, An Autumn Pastoral (also in the Wallace Collection), were commissioned by the financier Trudaine for his new chateau at Montigny-Lencoup, together with four overdoors by Oudry which are also in the Wallace Collection.

These great pastorals offer a characteristic Boucher blend of elegance and rusticity.

The Rape of Europa: 1732-34

Diderot bitterly attacked Boucher. All Diderot's fury about falseness, lack of observation of nature, corruption of morals, loses its relevance before the finest products of Boucher's art. His mythological world was more frankly feminine, and more accessible, than Tiepolo's; it hardly tries to astonish the spectator, and its magic is no exciting spell but a slow beguilement of the senses, a lulling tempo by which it is always afternoon in the gardens of Armida. There is no clash of love and duty, no public audience, and with barely the presence of men (Boucher increasingly could hardly be bothered to delineate them at all). But this does not automatically mean frivolity. Especially in the years up to and about 1750, Boucher's own artistic and actual vigor combined to produce a whole range of mythological pictures which were decorative, superbly competent, and tinged with their own vein of poetry.

The painting was painted for the avocat Francois Derbais who owned at least eight large Boucher's by 1735.

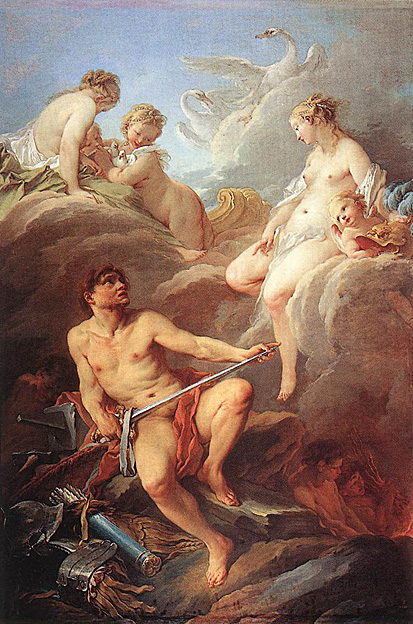

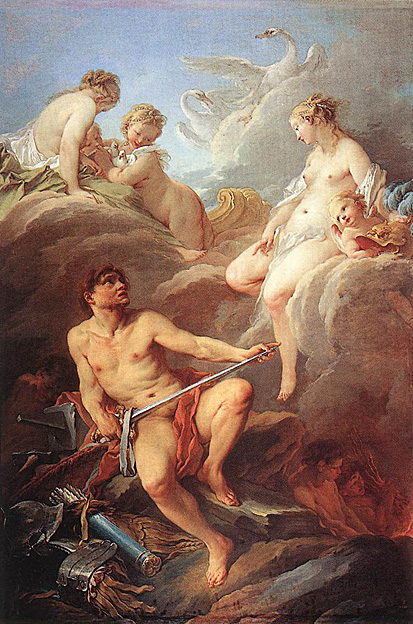

Venus Demanding Arms from Vulcan for Aeneas: 1732

In the Aeneid (8:370-385) Virgil tells how Venus asked Vulcan to make a set of armor for Aeneas, her son, when he was about to go to war in Latium. The outcome of Aeneas' victory was the founding of a Trojan settlement on the Tiber from which, according to the legend, the Romans descended.

This is an early version of the subject often treated by Boucher.

"Mean as it is, this palace, and this door,

Receiv'd Alcides, then a conqueror.

Dare to be poor; accept our homely food,

Which feasted him, and emulate a god."

Then underneath a lowly roof he led

The weary prince, and laid him on a bed;

The stuffing leaves, with hides of bears o'erspread.

Now Night had shed her silver dews around,

And with her sable wings embrac'd the ground,

When love's fair goddess, anxious for her son,

(New tumults rising, and new wars begun,)

Couch'd with her husband in his golden bed,

With these alluring words invokes his aid;

And, that her pleasing speech his mind may move,

Inspires each accent with the charms of love:

"While cruel fate conspir'd with Grecian pow'rs,

To level with the ground the Trojan tow'rs,

I ask'd not aid th' unhappy to restore,

Nor did the succor of thy skill implore;

Nor urg'd the labors of my lord in vain,

A sinking empire longer to sustain,

Tho'much I ow'd to Priam's house, and more

The dangers of Aeneas did deplore.

But now, by Jove's command, and fate's decree,

His race is doom'd to reign in Italy:

With humble suit I beg thy needful art,

O still propitious pow'r, that rules my heart!

A mother kneels a suppliant for her son.

By Thetis and Aurora thou wert won

To forge impenetrable shields, and grace

With fated arms a less illustrious race.

Behold, what haughty nations are combin'd

Against the relics of the Phrygian kind,

With fire and sword my people to destroy,

And conquer Venus twice, in conqu'ring Troy."

She said; and straight her arms, of snowy hue,

About her unresolving husband threw.

Her soft embraces soon infuse desire;

His bones and marrow sudden warmth inspire;

And all the godhead feels the wonted fire.

Not half so swift the rattling thunder flies,

Or forky lightnings flash along the skies.

The goddess, proud of her successful wiles,

And conscious of her form, in secret smiles.

Winter: 1735

The painting, comissioned by Marquise de Pompadour for one of her residences, is part of a series of four representing the four seasons.

Adoration of the Shepherds: 1750

Boucher had never been a committed artistic believer. Although he had worked in Italy, the Italian tradition did not tempt him into vast imaginative schemes. He never aimed at a heroic vision. He expressed no glorious promises about heaven: either as an Olympian refuge for aristocratic families, or in ordinary Christian terms. Like most French eighteenth-century painters, he could not evolve a satisfactory idiom for religious pictures of any kind; and he was particularly unsuited to the task by the nature of his real abilities.

The picture shows one of his rare paintings of religious subject.

The Interrupted Sleep: 1750

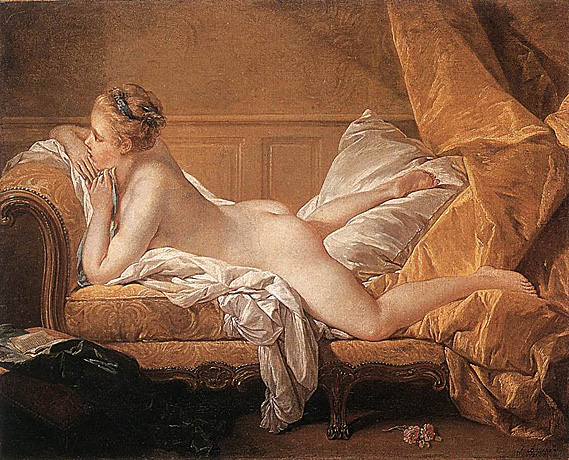

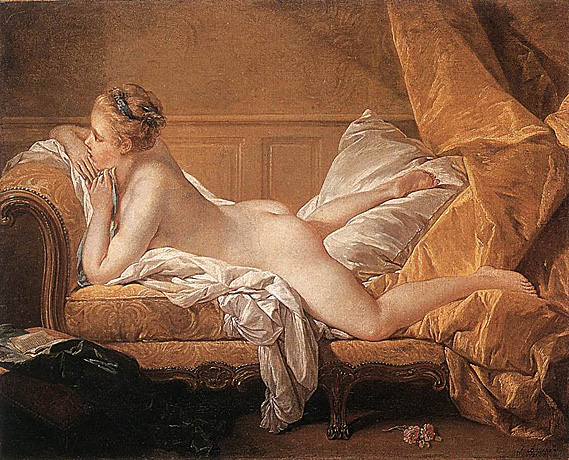

Blond Odalisque (L'Odalisque Blonde) - 1752

The painting is also known as the Back Nude of Mlle O'Murphy.

Girl Reclining (Louise O'Murphy) - 1751

This is a slightly different version of the painting in the Alte Pinakothek in Munich.

The Odalisk: 1753

Portrait of Marquise de Pompadour: 1759

Jeanne-Antoinette Poisson (1721-1764) became Marquise de Pompadour and maitresse en titre to Louis XV in 1745. Her lavish patronage of the arts, in particular of the Sevres porcelain factory and of Boucher, sustained the French Rococo style. Behind her in this portrait stands the sculpture of Love and Friendship which she had commissioned from Pigalle to symbolize her later, platonic relationship with the King.

The painting was commissioned from the artist in 1758 for the Bellevue Castle.

Portrait of Marquise de Pompadour: 1756

All his portraits of Madame de Pompadour are characterized by directness and emphasis upon spontaneity. He placed her reading, reclining, and well equipped with books. She pauses in her reading.

Marquise de Pompadour at the Toilet-Table: 1758

Apollo Revealing his Divinity before the Shepherdess Isse: 1750

The subject of the love of Apollo and the shepherdess Isse is taken from Ovid's Metamorphoses. The painting was commissioned from Boucher in 1749 by the Direction des Batiments du Roi.

Shepherd and Shepherdess Reposing: 1761

The Rising of the Sun: 1753

The companion piece The Setting of the Sun is also in the Wallace Collection.

These extravagant and wonderful pictures show Apollo as God of the Sun leaving Tethys with her Nereids and Tritons in the river Ocean as he drives up the morning sun in his chariot drawn by four white horses, and then returning to her at nightfall. Boucher counted these among his most successful pictures.

The Setting of the Sun: 1752

The companion piece The Rising of the Sun is also in the Wallace Collection.

Pan and Syrinx: ca 1762

Pan in Greek mythology is the god of woods and fields, flocks and herds. In Renaissance allegory he personifies Lust; he charmed the nymphs with the music of his pipes. The story of Pan and Syrinx is described by Ovid (Metamorphoses 1:689-713). Pan was pursuing a nymph of Arcadia named Syrinx when they reached the River Ladon which blocked her escape. To avoid the god's clutches she prayed to be transformed, and Pan unexpectedly found himself holding an armful of tall reeds. The sound of the wind blowing through them so pleased him that he cut some and made a set of pipes which are named after the nymph.

The Mill at Charenton: 1750's

The painting represents a real landscape, although it cannot be confirmed that the location is Charenton.

The Toilet of Venus: 1751

No French painter of the 18th century was more inextricably linked to court patronage than Francois Boucher. This picture was commissioned by Madame de Pompadour as part of the decoration for her cabinet de toilette at the Chateau de Bellevue, one of the residences she shared with Louis XV. The cupids and the doves are attributes of Venus as goddess of Love. The flowers allude to her role as patroness of gardens and the pearls to her mysterious birth from the sea. As a painter of nudes Boucher ranks with Rubens in the 17th century and Renoir in the 19th; among his contemporaries he had no equal.

The toilet of Venus is a timeless theme of sensuous seduction.

Vulcan Presenting Venus with Arms for Aeneas: 1757

This subject was often treated by Boucher, and the Louvre has three other versions. The delightful and decorative design, full of light and charm, was woven for the series of tapestries The Loves of the Gods, and typifies the spirit of Rococo decoration.

Source: Art Renewal Center

Source: Web Gallery of Art

This page is the work of Senex Magister

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.