Spanish Baroque Painter

1599 - 1660

Diego Rodriguez de Silva y Velazquez commonly referred to as Diego Velazquez, was a Spanish painter who was the leading artist in the court of King Philip IV. He was an individualistic artist of the contemporary baroque period, important as a portrait artist. In addition to numerous renditions of scenes of historical and cultural significance, he painted scores of portraits of the Spanish royal family, other notable European figures, and commoners, culminating in the production of his masterpiece Las Meninas (1656).

From the first quarter of the nineteenth century, Velazquez's artwork was a model for the realist and impressionist painters, in particular Edouard Manet. Since that time, more modern artists, including Spain's Pablo Picasso and Salvador Dali, as well as the Anglo-Irish painter Francis Bacon, have paid tribute to Velazquez by recreating several of his most famous works.

Born in Seville, Andalusia, Spain early on June 6, 1599, and baptized on June 6, Velazquez was the son of Juan Rodríguez de Silva (born Joao Rodrigues da Silva), a lawyer of Portuguese Jewish descent (son of Diogo da Silva and wife Maria Rodrigues, Portuguese Jews), and Jeronima Velazquez, a member of the hidalgo class, an order of minor aristocracy (it was a Spanish custom, in order to maintain a legacy of maternal inheritance, for the eldest male to adopt the name of his mother). He was educated by his parents to fear God and, intended for a learned profession, received good training in languages and philosophy. But he showed an early gift for art; consequently, he began to study under Francisco de Herrera, a vigorous painter who disregarded the Italian influence of the early Seville school. Velazquez remained with him for one year. It was probably from Herrera that he learned to use brushes with long bristles.

After leaving Herrera's studio when he was 12 years old, Velazquez began to serve as an apprentice under Francisco Pacheco, an artist and teacher in Seville. Though considered a generally dull, undistinguished painter, Pacheco sometimes expressed a simple, direct realism in contradiction to the style of Raphael that he was taught. Velazquez remained in Pacheco's school for five years, studying proportion and perspective and witnessing the trends in the literary and artistic circles of Seville.

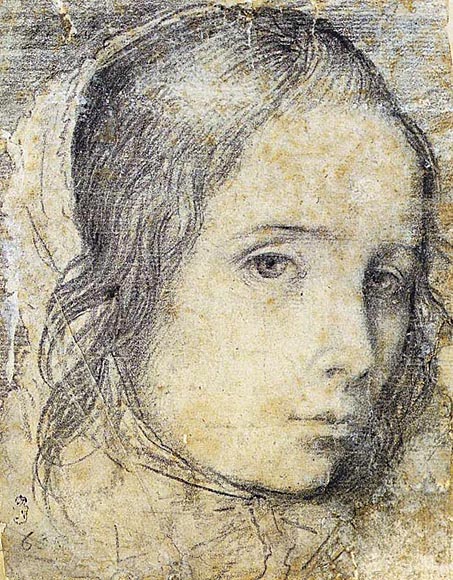

By the early 1620s, his position and reputation were assured in Seville. In 1618, Velazquez married Juana Pacheco (June 1, 1602-August 10, 1660), the daughter of his teacher. She bore him two daughters-his only known family. The younger, Ignacia de Silva Velazquez y Pacheco, died in infancy, while the elder, Francisca de Silva Velazquez y Pacheco (1619-1658), married painter Juan Bautista Martinez del Mazo at the Church of Santiago in Madrid in August 21, 1633.

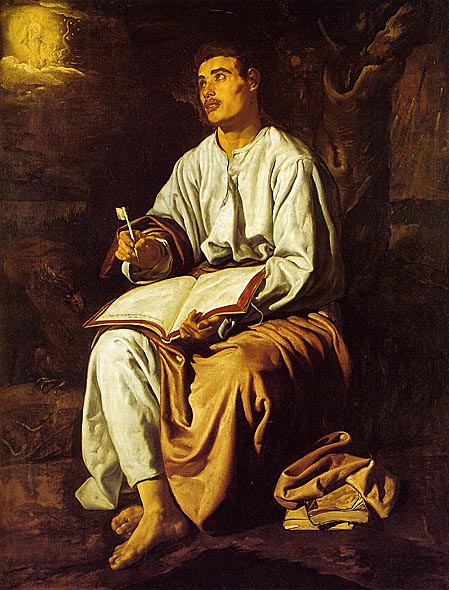

Velazquez produced other notable works in this time. Sacred subjects are depicted in Adoracion de los Reyes (1619, The Adoration of the Magi), and Jessu y los peregrinos de Emaus (1626, Christ and the Pilgrims of Emmaus), both of which begin to express his more pointed and careful realism.

Velazquez went to Madrid in the first half of April 1622, with letters of introduction to Don Juan de Fonseca, himself from Seville, who was chaplain to the King. At the request of Pacheco, Velazquez painted the portrait of the famous poet Luis de Gongora y Argote. Velazquez painted Gongora crowned with a laurel wreath, but painted over it at some unknown later date. It is possible that Velazquez stopped in Toledo on his way from Seville, on the advice of Pacheco, or back from Madrid on that of Gongora, a great admirer of El Greco, having composed a poem on the occasion of his death.

His name, even greater encouragement dino

that the clarines of Fame possible,

illustrates that the field of marble grave:

venéralo and continued your way.

Yace the Greek. Inherited Nature

Art and the Arts, study; Iris, colors;

Febo, lights-if not shadows, Morfeo.

Tanta urn, despite its hardness,

tears drink, and how many sweats odors

KNOW funeral of tree bark.

In December 1622, Rodrigo de Villandrando, the king's favorite court painter, died. Don Juan de Fonseca conveyed to Velazquez the command to come to the court from the Count-Duke of Olivares, the powerful minister of Philip IV. He was offered 50 ducats to defray his expenses, and he was accompanied by his father-in-law. Fonseca lodged the young painter in his own home and sat for a portrait himself, which, when completed, was conveyed to the royal palace. A portrait of the king was commissioned. On August 16, 1623, Philip IV sat for Velazquez. Complete in one day, the portrait was likely to have been no more than a head sketch, but both the king and Olivares were pleased. Olivares commanded Velazquez to move to Madrid, promising that no other painter would ever paint Philip's portrait and all other portraits of the king would be withdrawn from circulation. In the following year, 1624, he received 300 ducats from the king to pay the cost of moving his family to Madrid, which became his home for the remainder of his life.

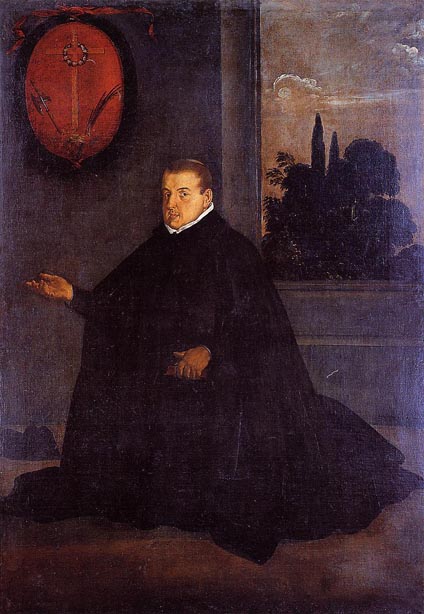

In 1615 Olivares became one of Prince Philip's six personal attendants. When Philip was crowned king in April of 1621, he had just reached 16 years of age, and Olivares was approaching the age of 34. By this time Olivares, a man of unpleasing appearance and changing moods, had become the young king's irreplaceable companion. As Philip's favorite he was given the rank of grandee, the title most coveted by Castilian nobility. Reluctant to drop any part of his title, he styled himself "conde-duque" (count-duke).

From 1623 until Jan. 24, 1643, Olivares served as prime minister of Spain. He was unswervingly loyal to the King and was vehemently patriotic. He was also avid for power--both for himself and for Spain. The main objective of his domestic policy was to engender national unity among the separate kingdoms of the peninsula, kingdoms that he described as "anachronistic as crossbows." He attempted many economic reforms aimed at relieving the difficult situation that had arisen as a result of long reliance on the influx of precious metals from the New World. Among these programs were restrictions on granting favours (except for honorary titles); recoining of the old copper alloy moneys; introduction of paper money; promotion, with the aid of the Castilian Cortes (representative assembly), of various royal decrees to stop the industrial and commercial decline of the kingdom; and a project whereby the shipping companies would be able to compete more advantageously with the Dutch, English, and French commercial fleets. But his attempts to promote trade and industry met with failure, due largely to the fact that aristocratic Castilians, slaves to the idea of a rigid class structure, looked down upon all mercantile professions. His moves toward centralizing power in the hands of the king and his ministers were partly responsible for the revolts of the Catalans and the Portuguese, which began in 1640, and for an abortive conspiracy to form a separate Andalusian kingdom (1641). In foreign policy Olivares was guided by the dream of austracismo, a joint European hegemony of the Austrian and Spanish Habsburg kingdoms. This policy meant continued Spanish involvement in the Thirty Years' War and ended with the eclipse of Spanish power by France. Yet in the period of the Counter-Reformation, it is difficult to conceive of Spain following a different course: in this sense it was almost inevitable, and Olivares can hardly be judged in terms of its ultimate failure.

As a result of a court intrigue headed by the Queen (Elizabeth of France), Philip removed his ailing favourite from office in January 1643. Although the King would undoubtedly have liked to recall him later, other grandees, long jealous of his power, continued to discredit him. Eventually Olivares was exiled, along with his wife, to the city of Toro. In December 1644 the Inquisition began to investigate his conduct. He died in Toro the following year.

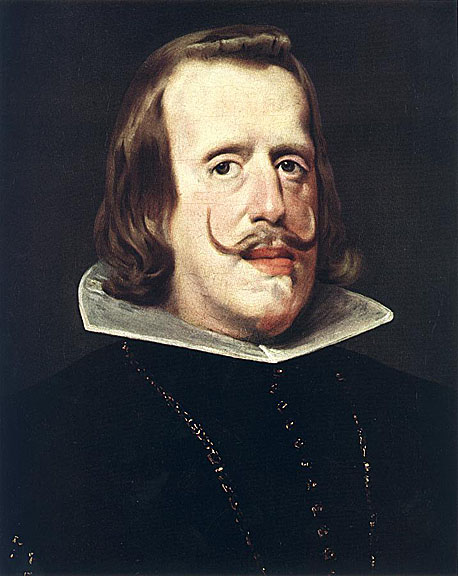

Through a bust portrait of the king, painted in 1623, Velazquez secured admission to the royal service, with a salary of 20 ducats per month, besides medical attendance, lodgings and payment for the pictures he might paint. The portrait was exhibited on the steps of San Felipe and was received with enthusiasm. It is now lost. The Museo del Prado, however, has two of Velazquez's portraits of the king in which the severity of the Seville period has disappeared and the tones are more delicate. The modeling is firm, recalling that of Antonio Mor, the Dutch portrait painter of Philip II, who exercised a considerable influence on the Spanish school. In the same year, the Prince of Wales (afterwards Charles I) arrived at the court of Spain. Records indicate that he sat for Velazquez, but the picture is now lost.

In September 1628, Peter Paul Rubens came to Madrid as an emissary from the Infanta Isabella, and Velazquez kept his company among the Titians at the Escorial. Rubens was then at the height of his powers. The seven months of the diplomatic mission showed Rubens' brilliance as painter and courtier. Rubens had a high opinion of Velazquez, but he effected no great change in his painting. He reinforced Velazquez's desire to see Italy and the works of the great Italian masters.

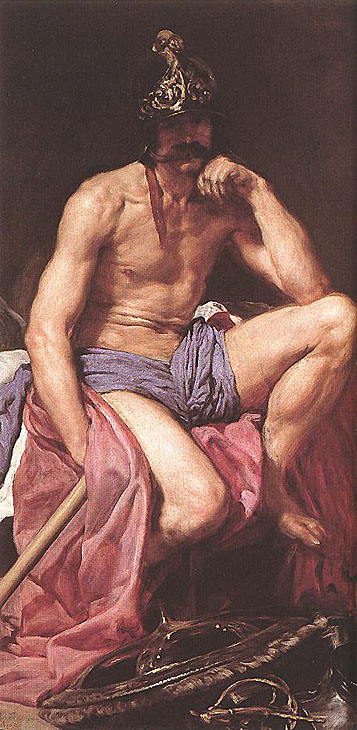

In 1627, Philip set a competition for the best painters of Spain with the subject to be the expulsion of the Moors. Velazquez won. His picture was destroyed in a fire at the palace in 1734. Recorded descriptions of it say that it depicted Philip III pointing with his baton to a crowd of men and women driven off under charge of soldiers, while the female personification of Spain sits in calm repose. Velazquez was appointed gentleman usher as reward. Later he also received a daily allowance of 12 réis, the same amount allotted to the court barbers, and 90 ducats a year for dress. Five years after he painted it in 1629, as an extra payment, he received 100 ducats for the picture of Bacchus (The Feast of Bacchus). The spirit and aim of this work are better understood from its Spanish name, Los borrachos or Los bebedores (the tipplers), who are paying mock homage to a half-naked ivy-crowned young man seated on a wine barrel. The painting is firm and solid, and the light and shade are more deftly handled than in former works. Altogether, this production may be taken as the most advanced example of the first style of Velazquez.

In 1629, he went to live in Italy for a year and a half. Though his first Italian visit is recognized as a crucial chapter in the development of Velazquez's style - and in the history of Spanish Royal Patronage, since Philip IV sponsored his trip - we know rather little about the details and specifics: what the painter saw, whom he met, how he was perceived and what innovations he hoped to introduce into his painting. It is canonical to divide the artistic career of Velazquez by his two visits to Italy, with his second grouping of works following the first visit and his third grouping following the second visit. This somewhat arbitrary division may be accepted though it will not always apply, because, as is usual in the case of many painters, his styles at times overlap each other. Velazquez rarely signed his pictures, and the royal archives give the dates of only his most important works. Internal evidence and history pertaining to his portraits supply the rest to a certain extent.

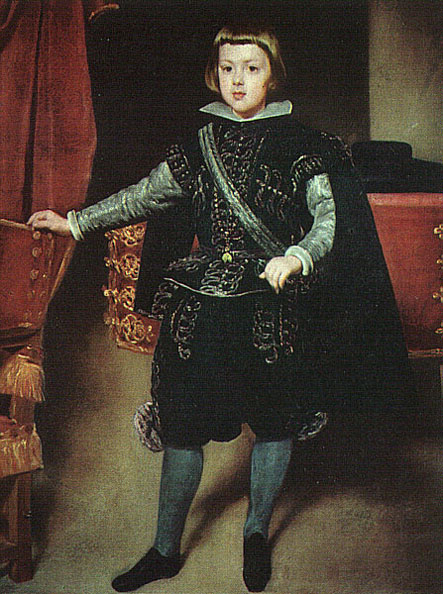

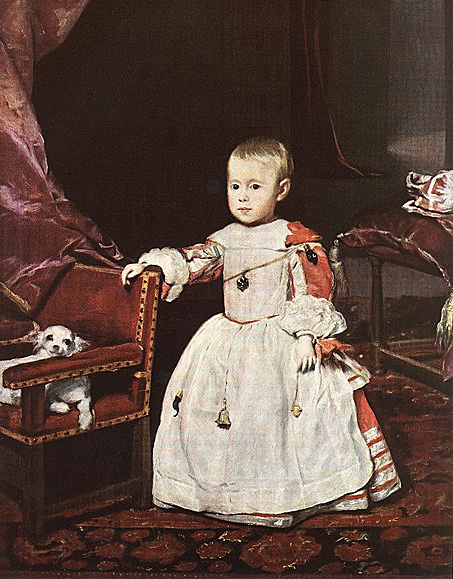

Velazquez then painted the first of many portraits of the young prince and heir to the Spanish throne, Don Baltasar Carlos, looking dignified and lordly even in his childhood, in the dress of a field marshal on his prancing steed. The scene is in the riding school of the palace, the king and queen looking on from a balcony, while Olivares attends as master of the horse to the prince. Don Baltasar died in 1646 at the age of seventeen, so, judging by his age in the portrait, it must have been painted in about 1641.

The powerful minister Olivares was the early and constant patron of the painter. His impassive, saturnine face is familiar to us from the many portraits painted by Velazquez. Two are notable; one is a full-length, stately and dignified, in which he wears the green cross of the order of Alcantara and holds a wand, the badge of his office as master of the horse, the other, a great equestrian portrait in which he is flatteringly represented as a field marshal during action. In these portraits, Velazquez has well repaid the debt of gratitude that he owed to his first patron, whom Velazquez stood by during Olivares's fall from power, thus exposing himself to the great risk of the anger of the jealous Philip. The king, however, showed no sign of malice towards his favorite painter.

The sculptor Montafles modeled a statue of one of Velazquez's equestrian portraits of the king, painted in 1636, which was cast in bronze by the Florentine sculptor Pietro Tacca and which now stands in the Plaza de Oriente at Madrid. The original of this portrait no longer exists, but several others do. Velazquez, in this and in all his portraits of the king, depicts Philip wearing the golilla, a stiff linen collar projecting at right angles from the neck. It was invented by the king, who was so proud of it that he celebrated it by a festival followed by a procession to the church to thank God for the blessing. Thus, the golilla was the height of fashion, and appeared in most of the male portraits of the period.

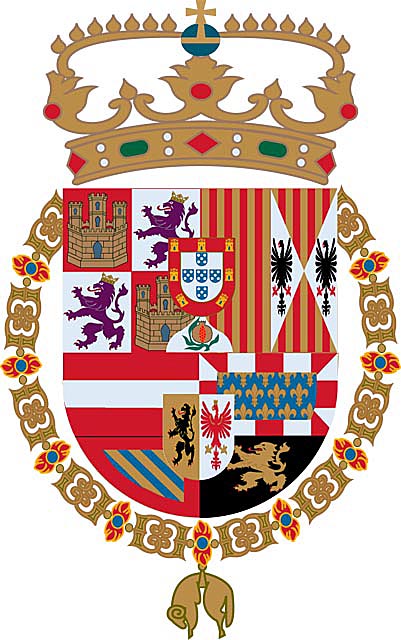

Philip IV (Habsburg) (1605-1665) King of Spain from 1621, son and successor of Philip III. A discerning patron of the arts (particularly of Velazquez), he had no interest in politics and left the administration of government to his favorite minister, Caspar de Guzman, count-duke of Olivares. His reign saw the continuing decline of Spain as a dominant European power. In 1640, Portugal regained its independence after a revolt; in 1648, Holland was lost in the Treaty of Westphalia; and in 1659 the Treaty of the Pyrenees cost Spain her frontier fortresses in Flanders.

Philip IV was married twice. His first wife was Elizabeth (Isabel) of Bourbon (1602 -1644), princess of France, daughter of King Henry IV of France and Marie de Medici; she married Philip IV in 1615 before he came to the throne. Her betrothal was depicted by Rubens in The Exchange of Princesses. Their 1st child, daughter Maria Theresa (1638-83), was the first wife of Louis XIV of France. His second wife was his own niece, Marianna of Austria, daughter of Philip IV's sister, Maria Anna and Ferdinand III.

Philip IV was succeeded by his four-year-old son, Charles II, the last of the Habsburgs.

Velazquez was in constant and close attendance on Philip, accompanying him in his journeys to Aragon in 1642 and 1644, and was doubtless present with him when he entered Lerida as a conqueror. It was then that he painted a great equestrian portrait in which the king is represented as a great commander leading his troops-a role which Philip never played except in pageantry. All is full of animation except the stolid face of the king. It hangs as a pendant to the great Olivares portrait-fit rivals of the neighboring Charles V by Titian, which inspired Velazquez to excel himself, and both remarkable for their silvery tone and their feeling of open air.

Besides the forty portraits of Philip by Velazquez, he painted portraits of other members of the royal family: Philip's first wife, Isabella of Bourbon, and her children, especially her eldest son, Don Baltasar Carlos, of whom there is a beautiful full-length in a private room at Buckingham Palace. Cavaliers, soldiers, churchmen, and the prominent poet Francisco de Quevedo (now at Apsley House), sat for Velazquez.

In 1615, Elisabeth (also Isabel) was married to the future Philip IV of Spain. She was Queen of Spain from 1621 to 1644. This marriage followed a tradition of cementing military and political alliances between the Catholic powers of France and Spain with royal marriages. The tradition went back to the marriage of King Philip II of Spain with the French princess, Élisabeth de Valois, the daughter of King Henry II of France, in 1559 as part of the Peace of Cateau-Cambrésis. They were parents to seven children:

Infanta Mary Margaret (Maria Margarita) (1621)

Infanta Margaret Mary Catherine (Margarita Maria Catalina) (1623) )

Infanta Mary Eugenie (Maria Eugenia) (1625-1627) )

Infanta Elisabeth Mary Theresa (Isabel Maria Teresa) (1627) )

Baltasar Carlos, Prince of the Asturias (1629-1646) )

Infanta Marianne Antonia (Maria Ana "Mariana" Antonia) (1636) )

Maria Theresa of Spain (1638-1683), Queen Consort of France as first wife of Louis XIV of France

Elisabeth was renowned for her physical beauty, intelligence and noble personality, which made her very popular with the Spanish people.

_1652_53.jpg)

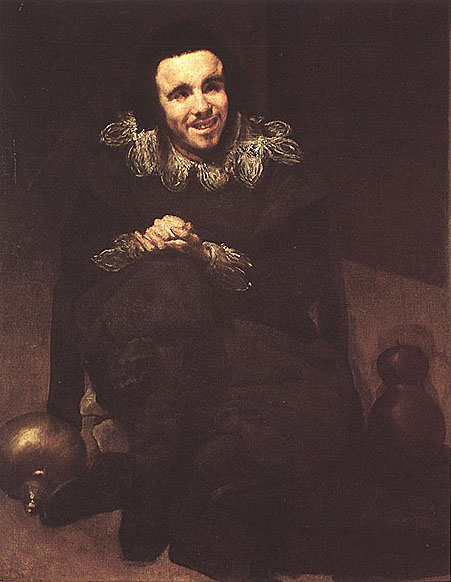

One wonders who the beautiful woman can be who adorns the Wallace collection, a brunette so unlike the usual fair-haired female sitters to Velazquez. This picture is one of the ornaments of the Wallace collection. However, if few ladies of the court of Philip have been depicted, Velazquez painted several of his buffoons and dwarfs. Velazquez appears to represent them with respect and sympathetically, as in El Primo (1644, English: The Favorite), whose intelligent face and huge folio with ink-bottle and pen by his side show him to be a wiser and better-educated man than many of the gallants of the court. Pablo de Valladolid (1635, English: Paul of Valladolid), a buffoon evidently acting a part, and El Bobo de Coria (1639, English: The Buffoon of Coria) belong to this middle period.

I am not sure whether I feel embarrassed or ashamed but I found myself intrigued about so many dwarves in Velazquez's paintings. It does not appear to me to be the kind of phenomena that has brought out the best of human qualities. These small people were a curiosity because they were different and what does that mean they were forced to endure? I really don't know but can only imagine the extent of what must have been quite demeaning for them. I continue to wonder but, I shouldn't be surprised, why man over the course of so many centuries doesn't seem to have the capacity to rise above what is different and accept our fellow humanity.

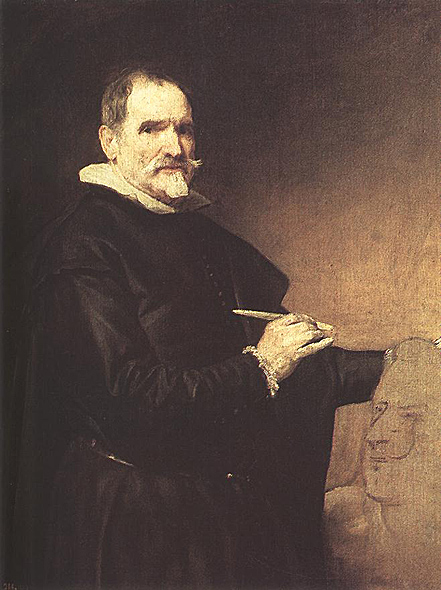

Senex Magister

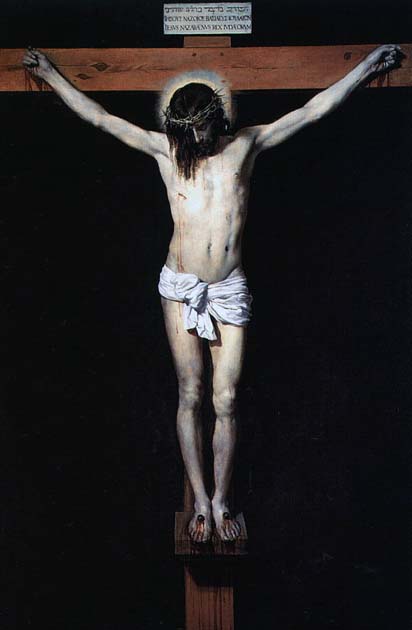

The greatest of the religious paintings by Velazquez also belongs to this middle period, the Cristo Crucificado (1632, English: Christ on the Cross). It is a work of tremendous originality, depicting Christ immediately after death. The Savior's head hangs on his breast and a mass of dark tangled hair conceals part of the face. The figure stands alone. The picture was lengthened to suit its place in an oratory, but this addition has since been removed. Some believe that the man in this painting is his uncle.

Velazquez's son-in-law Juan Bautista Martinez del Mazo had succeeded him as usher in 1634, and Mazo himself had received a steady promotion in the royal household. Mazo received a pension of 500 ducats in 1640, increased to 700 in 1648, for portraits painted and to be painted, and was appointed inspector of works in the palace in 1647.

Philip now entrusted Velazquez with carrying out a design on which he had long set his heart: the founding of an academy of art in Spain. Rich in pictures, Spain was weak in statuary, and Velazquez was commissioned once again to proceed to Italy to make purchases.

Accompanied by his manservant Juan de Pareja, whom he trained in painting, Velazquez sailed from Malaga in 1649, landing at Genoa, and proceeded from Milan to Venice, buying paintings of Titian, Tintoretto and Veronese as he went. At Modena he was received with much favor by the duke, and here he painted the portrait of the duke at the Modena gallery and two portraits that now adorn the Dresden gallery, for these paintings came from the Modena sale of 1746.

He was born in 1660 to Alfonso IV d'Este, duke of Modena, and Laura Martinozzi, niece of Cardinal Mazarin. His sister, Mary of Modena, married the future James II of England in 1673 and became queen of England in 1685.

He became duke at the age of two. His mother, pious and rigorous, served as his regent until 1674, filling state offices with clerics under the advice of her Jesuit confessor Father Garimberti. When she left to accompany the princess to England, he assumed control at the age of fourteen, and was so transformed in the free and easy company of his cousin principe Cesare Ignazio d'Este, that on her return the dowager duchess withdrew from court. Francesco's foreign policy was affected by the requirements of Louis XIV, his sister's patron after 1688, but he resisted French attempts to interfere in the duchies. He learned the violin as a boy and the court orchestra was revived for him when he was eleven; the violinist was Giovanni Maria Bononcini. Francesco was a lavish and discerning patron of music. His library has remained substantially complete in the Biblioteca Estense, Modena.

Those works presage the advent of the painter's third and latest manner, a noble example of which is the great portrait of Pope Innocent X in the Doria Pamphilj Gallery in Rome, where Velazquez now proceeded. There he was received with marked favor by the Pope, who presented him with a medal and golden chain. Velazquez took a copy of the portrait-which Sir Joshua Reynolds thought was the finest picture in Rome-with him to Spain. Several copies of it exist in different galleries, some of them possibly studies for the original or replicas painted for Philip. Velazquez, in this work, had now reached the manera abreviada, a term coined by contemporary Spaniards for this bolder, sharper style. The portrait shows such ruthlessness in Innocent's expression that some in the Vatican feared that Velazquez would meet with the Pope's displeasure, but Innocent was well pleased with the work, hanging it in his official visitor's waiting room.

In 1650 in Rome Velazquez also painted a portrait of his servant, Juan de Pareja, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. This portrait procured his election into the Academy of St. Luke. Purportedly Velqzquez created this portrait as a warm-up of his skills before his portrait of the Pope. It captures in great detail Pareja's countenance and his somewhat worn and patched clothing with an impressive economy of brushwork; it is one of his best known pieces of portraiture.

King Philip wished that Velazquez return to Spain; accordingly, after a visit to Naples, where he saw his old friend Jose Ribera, he returned to Spain via Barcelona in 1651, taking with him many pictures and 300 pieces of statuary, which afterwards were arranged and cataloged for the king. Undraped sculpture was, however, abhorrent to the Spanish Church, and after Philip's death these works gradually disappeared. Isabella of Bourbon had died in 1644, and the king had married Marie-Anne of Austria, whom Velazquez now painted in many attitudes. He was specially chosen by the king to fill the high office of aposentador mayor, which imposed on him the duty of looking after the quarters occupied by the court-a responsible function which was no sinecure and one which interfered with the exercise of his art. Yet far from indicating any decline, his works of this period are amongst the highest examples of his style.

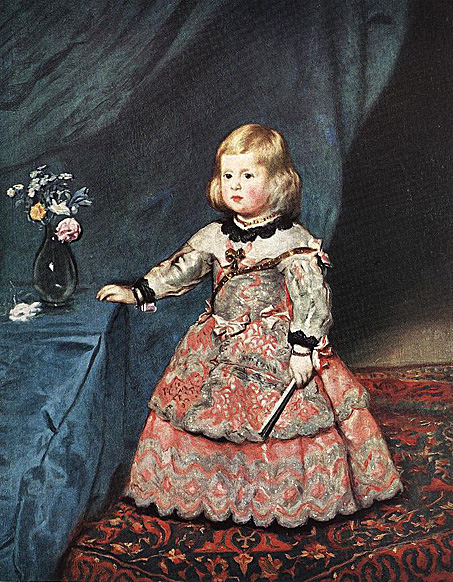

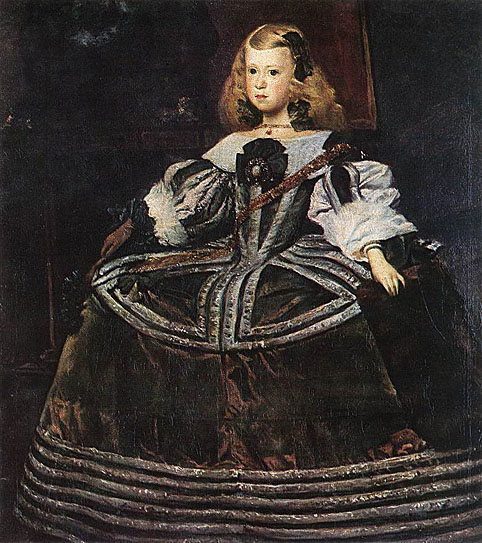

One of the infantas, Margarita, the eldest daughter of the new Queen, appears to be subject of Las Meninas (1656, English: The Maids of Honor), Velazquez's magnum opus. However, in looking at the various viewpoints of the painting it is unclear as to who or what is the true subject. Is it the royal daughter, or perhaps the painter himself? The answer may lie in the image on the back wall, depicting the King and Queen. Is this image a mirror, in which case the King and Queen are standing where we stand? Are they the subject of Velazquez's work? Or is the work simply a court painting? Much is still in speculation about the true subject of this masterpiece, and many of the questions that we ask may never be truly answered.

Created four years before his death, it is a staple of the European baroque period of art. An apotheosis of the work has been effected since its creation; Luca Giordano, a contemporary Italian painter, referred to it as the "theology of painting," and the eighteenth century the Englishman Thomas Lawrence cited it as the "philosophy of art," so decidedly capable of producing its desired effect. That effect has been variously interpreted; Dale Brown points out an interpretation that, in inserting within the work a faded portrait of the king and queen hanging on the back wall, Velázquez has ingeniously prognosticated the fall of the Spanish empire that was to gain momentum following his death. Another interpretation is that the portrait is in fact a mirror, and that the painting itself is in the perspective of the King and Queen; hence their reflection can be seen in the mirror on the back wall.

It is said the king painted the honorary Cruz Roja (Red Cross) of the Orden de Santiago (Order of Santiago) on the breast of the painter as it appears today on the canvas. However, Velazquez did not receive this honor of knighthood until three years after execution of this painting. Even the King of Spain could not make his favorite a belted knight without the consent of the commission established to inquire into the purity of his lineage. This aim of these inquiries would be to prevent the appointment to positions of anyone found to have even a taint of heresy in their lineage-that is, a trace of Jewish or Moorish blood or contamination by trade or commerce in either side of the family for many generations. The records of this commission have been found among the archives of the Order of Santiago. Velazquez was awarded the honor in 1659. His occupation as plebeian and tradesman was justified because, as painter to the king, he was evidently not involved in the practice of "selling" pictures.

.jpg)

In his 1966 book The Order of Things, the philosopher Michel Foucault devotes the opening chapter to a detailed analysis of Las Meninas. He describes the ways in which the painting problematizes issues of representation through its use of mirrors, screens, and the subsequent oscillations that occur between the image's interior, surface, and exterior. In his book, "The Dying Animal", Philip Roth uses Las Meninas as a metaphor for the distracted attraction of courtship.

Had it not been for this royal appointment, which enabled Velazquez to escape the censorship of the Inquisition, he would not have been able to release his La Venus del espejo (c. 1644-1648, English: Venus at her Mirror) also known as The Rokeby Venus. It is the only surviving female nude by Velazquez.

Detail of Las Meninas (Velazquez's self-portrait)There were essentially only two patrons of art in Spain-the church and the art-loving king and court. Bartolome Esteban Murillo was the artist favored by the church, while Velázquez was patronized by the crown. One difference, however, deserves to be noted. Murillo, who toiled for a rich and powerful church, left little means to pay for his burial, while Velazquez lived and died in the enjoyment of good salaries and pensions.

One of his final works was Las hilanderas (The Spinners), painted circa 1657, representing the interior of the royal tapestry works. It is full of light, air and movement, featuring vibrant colors and careful handling. Anton Raphael Mengs said this work seemed to have been painted not by the hand but by the pure force of will. It displays a concentration of all the art-knowledge Velazquez had gathered during his long artistic career of more than forty years. The scheme is simple-a confluence of varied and blended red, bluish-green, grey and black.

Velazquez's final portraits of the royal children are among his finest works. These include the Infanta Margarita in blue dress and his only surviving portrait of the sickly Prince Felipe Prospero. The latter is remarkable for its combination of the sweet features of the child prince and his dog with a subtle sense of gloom. As in all of the artist's late paintings, the handling of the colors is extraordinarily fluid and vibrant.

In 1660 a peace treaty between France and Spain was consummated by the marriage of Maria Theresa with Louis XIV, and the ceremony took place on the Island of Pheasants, a small swampy island in the Bidassoa. Velazquez was charged with the decoration of the Spanish pavilion and with the entire scenic display. He attracted much attention from the nobility of his bearing and the splendor of his costume. On June 26 he returned to Madrid, and on July 31 he was stricken with fever. Feeling his end approaching, he signed his will, appointing as his sole executors his wife and his firm friend named Fuensalida, keeper of the royal records. He died on August 6, 1660. He was buried in the Fuensalida vault of the church of San Juan Bautista, and within eight days his wife Juana was buried beside him. Unfortunately, this church was destroyed by the French in 1811, so his place of interment is now unknown. There was much difficulty in adjusting the tangled accounts outstanding between Velazquez and the treasury, and it was not until 1666, after the death of King Philip, that they were finally settled.

Until the nineteenth century, little was known outside of Spain of Velazquez's work. His paintings mostly escaped being stolen by the French marshals during the Peninsular War. In 1828 Sir David Wilkie wrote from Madrid that he felt himself in the presence of a new power in art as he looked at the works of Velazquez, and at the same time found a wonderful affinity between this artist and the British school of portrait painters, especially Henry Raeburn. He was struck by the modern impression pervading Velazquez's work in both landscape and portraiture. Presently, his technique and individuality have earned Velazquez a prominent position in the annals of European art, and he is often considered a father of the Spanish school of art. Although acquainted with all the Italian schools and a friend of the foremost painters of his day, he was strong enough to withstand external influences and work out for himself the development of his own nature and his own principles of art.

Velazquez is often cited as a key influence on the art of Edouard Manet, important when considering that Manet is often cited as the bridge between realism and Impressionism. Calling Velazquez the "painter of painters," Manet admired Velazquez's use of vivid brushwork in the midst of the baroque academic style of his contemporaries and built upon Velazquez's motifs in his own art.

The powerful minister Olivares was the early and constant patron of the painter. During Olivares' Fall from power, Velasquez was loyal to his patron, exposing himself to the great risk of the anger of the jealous Philip. The king, however, showed no sign of malice towards his favorite painter.

Velázquez was in constant and close attendance on Philip, accompanying him in his journeys to Aragon in 1642 and 1644, and was doubtless present with him when he entered Lerida as a conqueror.

In this case, Velazquez has painted the interior of a kitchen with two half-length women to the left. On the table are a number of foods, perhaps the ingredients of an Alioli (a garlic mayonnaise made to accompany fish). These have been prepared by the maid. Extremely realistic, they were probably painted from the artist's own household as they appear in other bodegones from the same time.

In the background is a biblical scene, generally accepted to be the story of Martha and Mary (Luke 10). In it, Christ goes to the house of a woman named Martha. Her sisters, Mary, sat at his feet and listened to him speak. Martha, on the other hand, went to "make all the preparations that had to be made". Upset that Mary did not help her, she complained to Christ to which he responded: "Martha, Martha, you are worried and upset about many things, but only one thing is needed. Mary has chosen what is better, and it will not be taken away from her." In the painting, Christ is shown as a bearded man in a blue tunic. He gesticulates at Martha, the woman standing behind Mary, rebuking her for her frustration.

The foods are shown prepared in ways typical of Spanish cookery at the time. His painstaking attention to detail show how important Velázquez considered it to represent realistic scenes. The plight of Martha clearly relates to that of the maid in the foreground. She has just prepared a large amount of food and, from the redness of her creased puffy cheeks; we can see that she is also upset. To comfort her (or perhaps even to rebuke her), the elderly woman indicates the scene in the background reminding her that she can not expect to gain fulfillment from work alone. The maid, who cannot bring herself to look directly at the biblical scene and instead looks out of the painting towards us, meditates on the implications of the story.

This is probably the most likely interpretation of the painting. However scholars have given other readings of it. Some have argued over the identities of the characters, suggesting that the maid in the foreground is actually Martha herself and the lady standing in the background is just an incidental character.

Another point of contention is over the representation of the background. On one hand, we may be looking at a mirror or through a hatch at the biblical scene. If so, it would imply that the whole painting, foreground and background, is set in Christ's time and would perhaps lend weight to the argument that the maid in the foreground is Martha. On the other hand, the biblical scene may just be a painting which is hung in the maid's kitchen. Given that the bodegones usually represent images of contemporary Spain, many have thought that this is probably the most likely explanation. However, the National Gallery say that following cleaning and restoration in 1964, it is now clear that the smaller scene is framed by a hatch or aperture through the wall. The suggestion of other possibilities, especially that of the scene as a painting, may remain as an element in the meaning of the work.

Whatever the truth of this is, we can appreciate this as an early example of Velazquez's interest in layered composition, a form also known as "paintings within the painting". He continually exploited this form throughout his career. Other examples of this are Kitchen Scene with the Supper in Emmaus (1618), Las Hilanderas (1657) and his masterpiece Las Meninas (1656).

Credit cannot be given to the tale that Democritus spent his leisure hours in chemical researches after the philosopher's stone -- the dream of a later age; or to the story of his conversation with Hippocrates concerning Democritus's supposed madness, as based on spurious letters. Democritus has been commonly known as "The Laughing Philosopher," and it is gravely related by Seneca that he never appeared in public with out expressing his contempt of human follies while laughing. Accordingly, we find that among his fellow-citizens he had the name of "the mocker". He died at more than a hundred years of age. It is said that from then on he spent his days and nights in caverns and sepulchers, and that, in order to master his intellectual faculties, he blinded himself with burning glass. This story, however, is discredited by the writers who mention it insofar as they say he wrote books and dissected animals, neither of which could be done well without eyes.

Democritus expanded the atomic theory of Leucippus. He maintained the impossibility of dividing things ad infinitum. From the difficulty of assigning a beginning of time, he argued the eternity of existing nature, of void space, and of motion. He supposed the atoms, which are originally similar, to be impenetrable and have a density proportionate to their volume. All motions are the result of active and passive affection. He drew a distinction between primary motion and its secondary effects, that is, impulse and reaction. This is the basis of the law of necessity, by which all things in nature are ruled. The worlds which we see -- with all their properties of immensity, resemblance, and dissimilitude -- result from the endless multiplicity of falling atoms. The human soul consists of globular atoms of fire, which impart movement to the body. Maintaining his atomic theory throughout, Democritus introduced the hypothesis of images or idols (eidola), a kind of emanation from external objects, which make an impression on our senses, and from the influence of which he deduced sensation (aesthesis) and thought (noesis). He distinguished between a rude, imperfect, and therefore false perception and a true one. In the same manner, consistent with this theory, he accounted for the popular notions of Deity; partly through our incapacity to understand fully the phenomena of which we are witnesses, and partly from the impressions communicated by certain beings (eidola) of enormous stature and resembling the human figure which inhabit the air. We know these from dreams and the causes of divination. He carried his theory into practical philosophy also, laying down that happiness consisted in an even temperament. From this he deduced his moral principles and prudential maxims. It was from Democritus that Epicurus borrowed the principal features of his philosophy.

The author of this article is anonymous. The IEP is actively seeking an author who will write a replacement article.

_1660.jpg)

His master was Pablo de Roxas. His first known work, dating 1597, is the graceful St. Christopher in the church of El Salvador at Seville. His boy Christ (dated 1607) is in the sacristy of the cathedral of Seville. His masterpiece, the great altar of St Jerome at San Isidoro del Campo, Santiponce near Seville, was contracted in 1609 and completed in 1613. Montanes executed most of his sculpture in wood, gessoed, polychromed and gilded.

Other works were the great altars at Santa Clara in Seville and at San Miguel in Jerez, the Conception and the realistic figure of Christ Crucified in Cristo de la Clemencia, commissioned in 1603, in the sacristy of Seville cathedral (illustration); the figure of St John the Baptist, and the St Bruno (1620); a tomb for Don Perez de Guzman and his wife (1619); the highly realistic polychromed wood head and hands of St Ignatius of Loyola (1610) and of St Francis Xavier in the university church of Seville, where the costumed figures were used in celebrations.

Montanes achieved great fame in his lifetimes; he died in 1649, leaving a large family. His works are more realistic than imaginative, but this, allied with an impeccable taste, produced remarkable results. In 1635, in preparation for the bronze equestrian statue of King Philip IV, by Pietro Tacca in Florence in 1640, Montanes went to Madrid and spent seven months there modeling a portrait of Philip IV, which was to be sent to Florence and used by Pietro Tacca in his equestrian sculpture for Madrid.

He had many imitators, his son Alonzo Martinez, who died in 1668, being among them.

"Look-tramps!" people exclaim when they see this painting and the one of Aesop beside it in the Prado Museum. Velazquez liked to paint the poor. He must have found this fellow in a backstreet somewhere. Who was Menippus? A third-century Greek slave who wrote snide poems about the world.

Velazquez's Menippus isn't supposed to look very trustworthy. "Rogues and swindlers like this man were a plague on the nation," writes Gaya Nuno, a Velazquez biographer. "The number of locksmiths, carpenters, or surgeons had not increased in the twenty years since Velazquez had come to Madrid [in 1623], but types like this had multiplied. This old picaro wrapped in his big cape, his eyes sparkling with wine is the updated version of the old water-carrier Velazquez painted in Seville when he was a boy. That water-carrier earned his living by honest work whereas this Menippus is just an old rascal."

The man has a mythology almost as great as his stories. Socrates made poems of him. The biographer Plutarch put him as one of the "Seven Wise Men" or "Seven Sages" and serving in the council of the 6th century Lydian King Croesus.

It was said that his third owner set him free because of his wit and wisdom and that he was killed by the people of Delphi (while working for the king) when he was sent there to divide money among the people. When he arrived, he found them dishonest and refused to give them any. For his efforts they threw him off a cliff. It is said that a terrible plague befell the people as a result.

Velázquez rendition is of a very simple man whom has seen a hard life -- etched in the face and eyes with wisdom and intellect. He stands there, a former slave, with his fables under his arm as if he is still giving council to kings.

In Velazquez's case it would be King Philip IV of Spain who was Velazquez's patron.

The culmination of his career is Las Meninas (The Maids of Honour) (Prado. c. 1656). It shows Velazquez at his easel, with various members of the royal family and their attendants in his studio, but it is not clear whether he has shown himself at work on a portrait of the king and queen (who are reflected in a mirror) when interrupted by the Infanta Margarita and her maids of honour or vice versa. Velazquez's prominence in the picture seems to assert his own importance and his pride in his art, but in the background he has included two pictures by Rubens showing the downfall of mortals who challenge the gods in the arts. Apparently spontaneous but in the highest degree worked out, it is both Velazquez's most complex essay in portraiture and an expression of the high claims he made for the dignity of his art. Luca Giordano called it 'the Theology of Painting' because 'just as theology is superior to all other branches of knowledge, so is this the greatest example of painting'. Posterity has endorsed his verdict, for in a poll of artists and critics in The Illustrated London News in August 1985, Las Meninas was voted — by some margin — 'the world's greatest painting'.

The number of good contemporary copies of Velazquez's work indicates that he ran a busy studio, but of his pupils only his son-in-law Mazo achieved any kind of distinction. As with most Spanish painters, Velazquez remained little known outside his own country until the Napoleonic Wars, but from the early 19th century the technical freedom of his work made him an inspiration to progressive artists, above all Manet, who regarded him as the greatest of all painters. Most of Velazquez's work is still in Spain, and his genius can be fully appreciated only in the Prado, which has most of his key masterpieces. Outside Spain, he is best represented in London — in the National Gallery, which has his only surviving female nude, the Rokeby Venus (ca. 1648), in the Wellington Museum, and in the Wallace Collection.

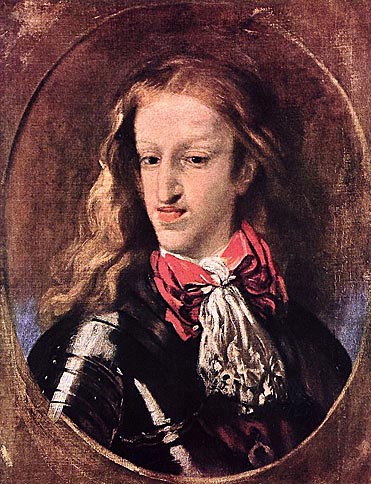

Charles II, or Carlos, was King of Spain, ruling over nearly all of Italy (except Piedmont, the Papal States and Venice), the Spanish territories in the Southern Low Countries, and Spain's overseas Empire, stretching from Mexico to the Philippines. Charles was the only surviving son of his Habsburg predecessor, King Philip IV of Spain and his second Queen (and niece), Mariana of Austria, another Habsburg. His birth was greeted with joy by the Spaniards, who feared the disputed succession which could have ensued if Philip IV had left no male heir.

Charles II is known in Spanish history as El Hechizado ("The Bewitched") from the popular belief - to which Charles himself subscribed - that his physical and mental disabilities were caused by "sorcery" rather than the much more likely cause: centuries of inbreeding within the Habsburg dynasty (in which first cousin and uncle/niece matches were commonly used to preserve a prosperous family's hold on its multifarious territories). Charles' own immediate pedigree was exceptionally populated with nieces giving birth to children of their uncles: Charles' mother was niece of Charles' father, being daughter of Maria Anna of Spain (1606-46) and Emperor Ferdinand III. Thus, Empress Maria Anna was simultaneously his aunt and grandmother. Still, the king was exorcised, and the exorcists of the kingdom were called upon to put straight questions to the devils they cast out. His great-great-great grandmother, Joanna the Mad, mother of the Spanish King Charles I who was also Holy Roman Emperor Charles V - became completely insane early in life; the fear of a taint of insanity ran through the Habsburgs. Charles descended from Joanna a total of 14 times - twice as a great-great-great grandson, and 12 times further.

Charles II was the last of the Spanish Habsburg dynasty, physically disabled, mentally retarded and disfigured (possibly through affliction with mandibular prognathism - he was unable to chew). His tongue was so large that his speech could barely be understood, and he frequently drooled. He may also have suffered from the bone disease acromegaly. He was treated as virtually an infant in arms until he was ten years old. Fearing the frail child would be overtaxed, he was left entirely uneducated, and his indolence was indulged to such an extent that he was not even expected to be clean. When his half-brother John of Austria the Younger, a natural son of Philip IV, obtained power by exiling the queen mother from court, he insisted that at least the king's hair should be combed.

The only vigorous activity shown by Charles was shooting, which he occasionally indulged in the preserves of the Escorial.

In 1679, the 18-year-old Charles II married Marie Louise of Orleans (1662-1689), eldest daughter of Philippe I, Duke of Orleans, the only sibling of Louis XIV, and his first wife Princess Henrietta of England. At that time, she was known as a lovely young woman. It is likely that Charles was impotent, and no children were born. Marie Louise became deeply depressed and died at 27, ten years after their marriage, leaving 28-year-old Charles heartbroken.

Still in desperate need of a male heir, the next year he married the 23-year-old Palatine princess Maria Anna of Neuburg, a daughter of Philip William, Elector of the Palatinate and sister-in-law of his uncle Leopold I, Holy Roman Emperor. However, this marriage was no more successful than the first in producing the much desired heir.

Towards the end of his life Charles became increasingly hypersensitive and strange, at one point demanding that the bodies of his family be exhumed so he could look upon the corpses. He reportedly wept upon viewing the body of his first wife, Marie Louise.

As the American historians Will and Ariel Durant put it, Charles II was "short, lame, epileptic, senile, and completely bald before thirty-five, he was always on the verge of death, but repeatedly baffled Christendom by continuing to live."

When Charles II died in 1700, the line of the Spanish Habsburgs died with him. He had named a great-nephew, Philippe de Bourbon, Duke of Anjou (a grandson of the reigning French king Louis XIV, and of Charles' half-sister, Maria Theresa of Spain - Louis himself was an heir to the Spanish throne through his mother, daughter of Philip III), as his successor. He had named his blood cousin Charles (from the Austrian branch of the Habsburg dynasty) as alternate successor.

The specter of the multi-continental empire of Spain passing under the effective control of Louis XIV provoked a massive coalition of powers to oppose the Duc d'Anjou's succession. The actions of Louis heightened the fears of the English, the Dutch and the Austrians, among others. In February of 1701, the French King caused the Parlement of Paris (a court) to register a decree that should Louis himself have no heir that the Duc d'Anjou--Phillip V of Spain--would surrender the Spanish throne for that of the French, ensuring dynastic continuity in Europe's greatest land power.

However, a second act of the French King "justified a hostile interpretation": pursuant to a treaty with Spain, Louis occupied several towns in the Spanish Netherlands (modern Belgium and Nord-Pas-de-Calais). This was the spark that ignited the powder keg created by the unresolved issues of the War of the League of Augsburg (1689-97) and the acceptance of the Spanish inheritance by Louis XIV for his grandson.

Almost immediately the War of the Spanish Succession (1702-1713) began. After eleven years of bloody, global warfare, fought on four continents and three oceans, the Duc d'Anjou, as Philip V, was confirmed as King of Spain on substantially the same terms that the powers of Europe had agreed to before the war. Thus the Treaties of Utrecht and Rastatt ended the war and "achieved little more than...diplomacy might have peacefully achieved in 1701." A proviso of the peace perpetually forbade the union of the Spanish and French thrones.

The House of Bourbon, founded by Philip V, has intermittently occupied the Spanish throne ever since, and sits today on the throne of Spain in the person of Juan Carlos I of Spain (1975-present).

Source: Art Renewal Center

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.