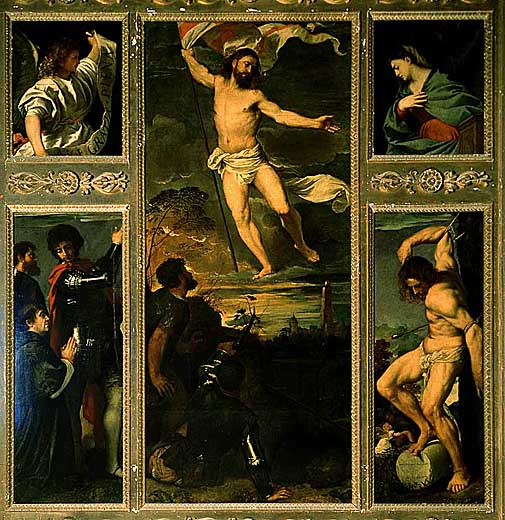

1488 - 1576

Tiziano Vecelli (c. 1485 - August 27, 1576), better known as Titian, was the leader of the 16th-century Venetian school of the Italian Renaissance. He was born in Pieve di Cadore, near Belluno (Veneto), in the Republic of Venice. During his lifetime he was often called Da Cadore, taken from the place of his birth.

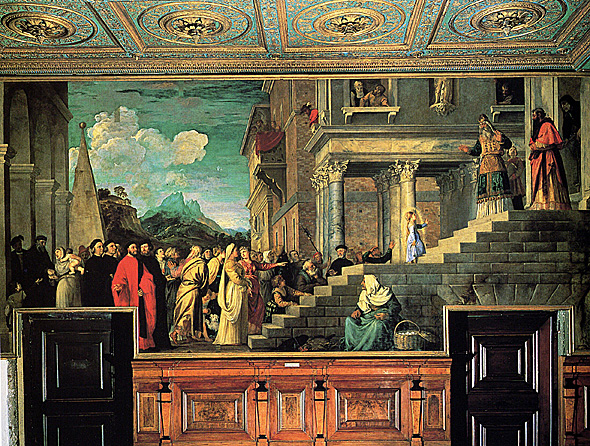

Recognized by his contemporaries as "the sun amidst small stars" (recalling the famous final line of Dante's Paradiso), Titian was one of the most versatile of Italian painters, equally adept with portraits and landscapes (two genres that first brought him fame), mythological and religious subjects. Had he died at the age of forty, he would still have to be regarded as one of the most influential artists of his time. But he lived on for a further half century, changing his manner so drastically that some critics refuse to believe that his early and later pieces could have been produced by the same man. What unites the two parts of his career is his deep interest in color. His later works may not contain vivid, luminous tints as his early pieces do, yet their loose brushwork and subtlety of polychromatic modulations have no precedents in the history of Western art.

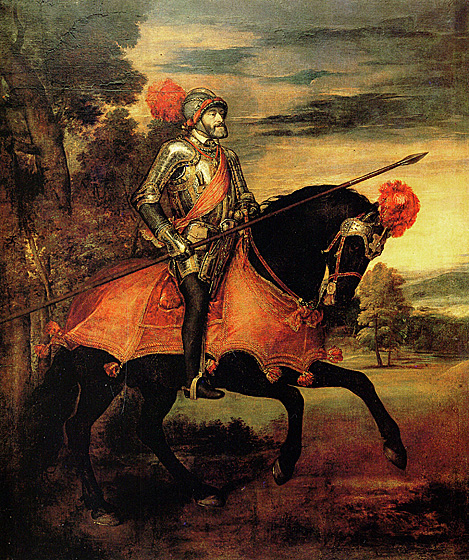

As the heir of four of Europe's leading dynasties - the Trastamara of the Kingdom of Castile and the Crown of Aragon, the Burgundian Valois of the Duchy of Burgundy and the Habsburgs of Austria - he ruled over extensive domains in Central, Western and Southern Europe, as well as Castilian colonies in the Americas and Philippines.

As the first monarch to reign in his own right over both the Kingdom of Castile and the Crown of Aragon (from 1555) he is often considered as the first King of Spain, with the name of Charles I. Upon his retirement, he divided his realms between his son Philip and his brother Ferdinand.

He was the son of Philip the Handsome and Joanna the Mad of Castile. His paternal grandparents were Emperor Maximilian I and Mary of Burgundy, whose daughter Margaret raised him. His maternal grandparents were Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile, whose marriage had first united their territories into what is now modern Spain, and whose daughter Catherine of Aragon was Queen of England and first wife of Henry VIII. His cousin was Mary I of England who married his son Philip.

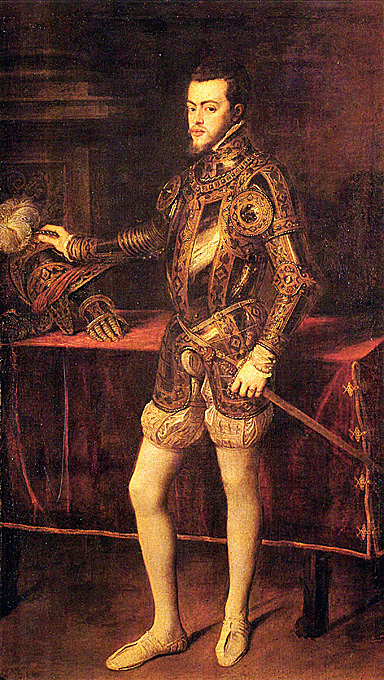

Under Philip II Spain reached the peak of its power but also met its limits. Having nearly reconquered the rebellious Netherlands, Philip's unyielding attitude led to their loss, this time permanently, as his wars expanded in scope and complexity. So in spite of the great and increasing quantities of gold and silver flowing into his coffers from the American mines, the riches of the Portuguese spice trade and the enthusiastic support of the Habsburg dominions for the Counter-Reformation, he would never succeed in suppressing Protestantism or defeating the Dutch rebellion. Early in his reign the Dutch might have laid down their weapons if he had desisted in trying to suppress Protestantism, but his devotion to Roman Catholicism and the principle of cuius regio, eius religio, as laid down by his father, would not permit him. He was a fervent Roman Catholic, and exhibited the typical 16th century disdain for religious heterodoxy.

One of the long term consequences of his striving to enforce Catholic orthodoxy through an intensification of the Inquisition was the gradual smothering of Spain's intellectual life. Students were barred from studying elsewhere and books printed by Spaniards outside the kingdom were banned. Even a highly respected churchman like Archbishop Carranza, was jailed by the Inquisition for seventeen years merely for ideas that seemed sympathetic in some degree to Protestant reformism. Such strict enforcement of orthodox belief was successful and Spain avoided the religiously inspired strife tearing apart other European dominions, but this came at a heavy price in the long run, as her great academic institutions were reduced to third rate status under Philip's successors.

Philip's wars against what he perceived to be heresies led not only to the persecution of Protestants, but also to the harsh treatment of the Moriscos, causing a massive local uprising in 1568. The damage of these endless wars would ultimately undermine the Spanish Habsburg empire after his passing. His endless meddling in details, his inability to prioritise, and his failure to effectively delegate authority hamstrung his government and led to the creation of a cumbersome and overly centralised bureaucracy. Under the weak leadership of his successors the Spanish ship of state would drift towards disaster. Yet such was the strength of the system he and his father had built that this did not start to become clearly apparent until a generation after his death.

However, Philip II's reign can hardly be characterized as a failure. He consolidated Spain's overseas empire, succeeded in massively increasing the importation of silver in the face of English, Dutch and French privateering, and ended the major threat posed to Europe by the Ottoman navy (though peripheral clashes would be ongoing). He succeeded in uniting Portugal and Spain through personal union. He dealt successfully with a crisis that could have led to the secession of Aragon. His efforts also contributed substantially to the success of the Catholic Counter-Reformation in checking the religious tide of Protestantism in Northern Europe. Philip was a complex man, and though given to suspicion of members of his court, was not the cruel tyrant that he has been painted by his opponents. Philip was known to intervene personally on behalf of the humblest of his subjects. Above all a man of duty, he was also trapped by it.

Don Fernando was a Spanish general and administrator. After a distinguished military career in Germany and Italy, Alba returned to Spain as adviser to King Philip II. Advocating a stern policy toward the rebels against Spain in the Netherlands, he was appointed (1567) captain general there, with full civil and military powers. The regent, Margaret of Parma, opposed him and resigned, and Alba became regent and governor-general. A religious fanatic and ruthless absolutist, he set out to crush the Netherlanders' attempts to gain religious toleration and political self-government. He set up a special court at Brussels, popularly known as the Court of Blood, which spread terror throughout the provinces. Some 18,000 persons were executed (among them the counts of Egmont and Hoorn) and their properties confiscated. Increased taxation also fanned popular resentment, and in 1572 the Netherlanders rebelled again, on a larger scale than before. Alba defeated the invading forces of William the Silent, but he was unable to recover much of the NW Netherlands, which had been taken by the Gueux. In 1573 he was recalled to Spain in disgrace. In 1580, Philip was persuaded to use Alba for the conquest of Portugal. He took Lisbon within a few weeks.

.jpg)

It was de facto lord of the city in place of his cousin Julius, when he became Pope Clement VII, together with Cardinal Silvio Passerini and all'odiato rival Alessandro de 'Medici (1523 - 1527).

When lansquenets of Charles V espugnarono Rome with the famous Sacco, the entire family escaped from the city in the so-called second expulsion of the Medici. When Clement VII restored peace with the Emperor, had the help in recapturing the city of Florence, with the famous siege of 1529 - 30, after which he was made head of the city Duke Alessandro de 'Medici. Ippolito hoped to be chosen him instead dell'odiato cousin Alessandro, his rival, but was instead removed from Florence, first as archbishop of Avignon, then coming appointed cardinal in 1529 by Pope Clement VII as compensation, and was sent as nuncio in Hungary.

He had an illegitimate child with Giulia Gonzaga, the prince Hasdrubal de 'Medici, who was a knight of' Order of Malta and died to the Fort St. Michael, on the island of Malta, July 13, 1565.

In 1535 he was sent by the Florentines as ambassador by Charles V, to condemn the serious abuses perpetrated by Duke Alessandro, however, but died of malaria during the journey, even if you just spread the voice of poisoning by Alessandro warp. He was buried in the church of San Lorenzo in Damasus in Rome.

On May 29, 1537 Paul III promulgated the papal bull Sublimus Dei against the enslavement of the indigenous peoples of the Americas.

In 1536, Paul III invited nine eminent prelates, distinguished by learning and piety alike, to act in committee and to report on the reformation and rebuilding of the Church. In 1537 they turned in their celebrated Concilium de emendenda ecclesia, exposing gross abuses in the Curia, in the church administration and public worship; and proffering many a bold and earnest word on behalf of abolishing such abuses. This report was printed not only at Rome, but at Strasburg and elsewhere.

But to the Protestants it seemed far from thorough; Martin Luther had his edition (1538) prefaced with a vignette showing the cardinals cleaning the Augean stable of the Roman Church with their foxtails instead of with lusty brooms. Yet the Pope was in earnest when he took up the problem of reform. He clearly perceived that the emperor would not rest until the problems were grappled in earnest, and a council without prejudice to the Pope was by an unequivocal procedure that should leave no room for doubt of his own readiness to make changes. Yet it is clear that the Concilium bore no fruit in the actual situation, and that in Rome no results followed from the committee's recommendations.

On the other hand, serious political complications resulted. In order to vest his grandson Ottavio Farnese with the dukedom of Camerino, Paul III forcibly wrestled the same from the duke of Urbino (1540). He also incurred virtual war with his own subjects and vassals by the imposition of burdensome taxes. Perugia, renouncing its obedience, was besieged by Pier Luigi, and forfeited its freedom entirely on its surrender. The burghers of Colonna were duly vanquished, and Ascanio was banished (1541). After this the time seemed ripe for annihilating heresy.

In 1521, his patron was Cardinal Giulio de' Medici, whose competitors for the papal throne felt the sting of Aretino's scurrilous lash. The installation of the prudish Fleming Adrian VI ("la tedesca tigna" in Pietro's words) instead encouraged Aretino to seek new patrons away from Rome, mainly with Federico II Gonzaga in Mantua, and with the condottiero Giovanni de' Medici ("Giovanni delle Bande Nere"). The election of his old Medici patron as Pope Clement VII sent him briefly back to Rome, but death threats and an attempted assassination from one of the victims of his pen, Bishop Giovanni Giberti, in July 1525, set him wandering through northern Italy in the service of various noblemen, distinguished by his wit, audacity and brilliant and facile talents, until he settled permanently in 1527, in Venice, the anti-Papal city of Italy, "seat of all vices" Aretino noted with gusto.

"In a letter to Giovanni de Medici written in 1524 Aretino encloses a satirical poem saying that due to a sudden aberration he has fallen in love with a female cook and temporarily switched from boys to girls..." (My Dear Boy)

From the security of Venice Aretino "kept all that was famous in Italy in a kind of state of siege," in Jakob Burckhardt's estimation. Francis I of France and Charles V pensioned him at the same time, each hoping for some damage to the other. "The rest of his relations with the great is mere beggary and vulgar extortion," was Burckhardt's assessment of a man the 19th century found utterly unprincipled, an abject flatterer, the object of judgmental disgust and yet the father of modern journalism:p "His literary talent, his clear and sparkling style, his varied observation of men and things, would have made him a considerable writer under any circumstances, destitute as he was of the power of conceiving a genuine work of art, such as a true dramatic comedy; and to the coarsest as well as the most refined malice he added a grotesque wit so brilliant that in some cases it does not fall short of that of Rabelais."

-Jacob Burckhardt, The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy, 1855.

Apart from both sacred and profane texts- a satire of high-flown Renaissance neo-Platonic dialogues is set in a brothel- and comedies such as La cortigiana and La talenta, Aretino is remembered above all for his letters, full of literary flattery that could turn to blackmail. They circulated widely in manuscript and he collected them and published them at intervals winning as many enemies as it did fame, and earned him the dangerous nickname Ariosto gave him: flagello dei principi ("scourge of princes"). The first English translations of some of Aretino's racier material have been coming onto the market recently.

La cortigiana is a brilliant parody of Castiglione's Il Cortegiano, and features the adventures of a Sienese gentleman, Messer Maco, who travels to Rome to become a cardinal. He would also like to win himself a mistress, but when he falls in love with a girl he sees in a window, he realizes that only as a courtier would he be able to win her. In mockery of Castiglione's advice on how to become the perfect courtier, a charlatan proceeds to teach Messer Maco how to behave as a courtier: he must learn how to deceive and flatter, and sit hours in front of the mirror.

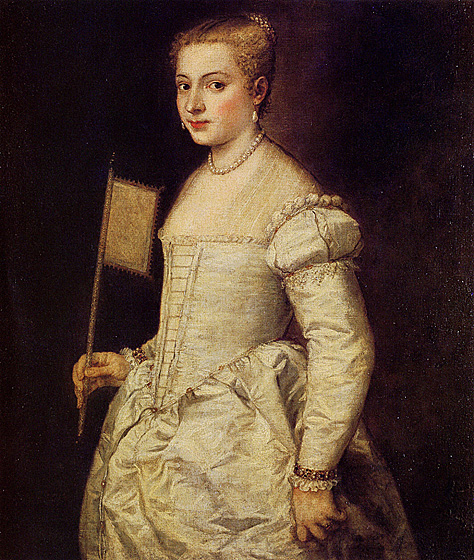

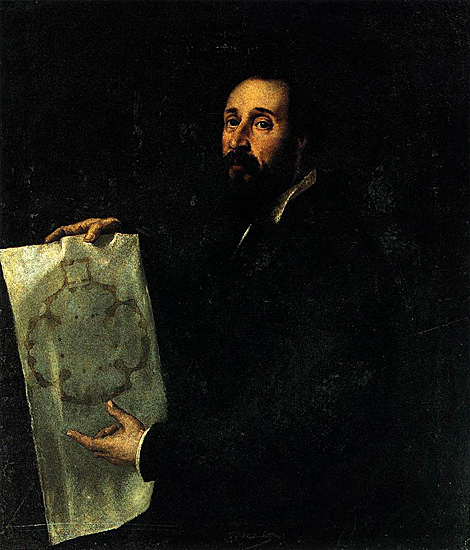

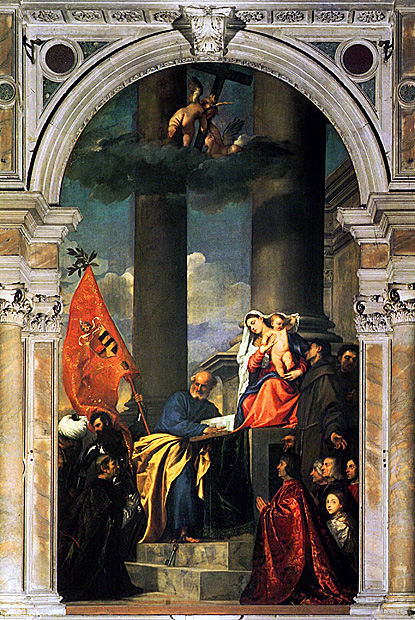

Aretino was a close friend of Titian, who painted his portrait (illustrations) at least three times. The early portrait is a psychological study of alarming modernity. Clement VII made Aretino a Knight of Rhodes, and Julius III named him a Knight of St. Peter, but the chain he wears for his 1545 portrait may have merely been jewelry. In his strictly-for-publication letters to patrons Aretino would often add a verbal portrait to Titian's painted one.

"He is said to have died of suffocation from laughing too much."

Ranuccio Farnese was born in Valentano. As a 12-year-old, he was made prior of the Knights of Malta's important property San Giovanni dei Forlani in Venice. Son of Pier Luigi Farnese, the illegitimate son of Pope Paul III, Farnese was created Cardinal at the age of 15 by his grandfather the pope: he was nicknamed the cardinalino ("small cardinal") for his young age.

He was also administrator of the archdiocese of Naples, and was granted several bishoprics. Farnese was patron to Federico Commandino, an important translator of ancient Greek mathematical works.

Farnese's brother, Ottavio Farnese, was Duke of Parma.

He is entombed in the Basilica di San Giovanni in Laterano in Rome.

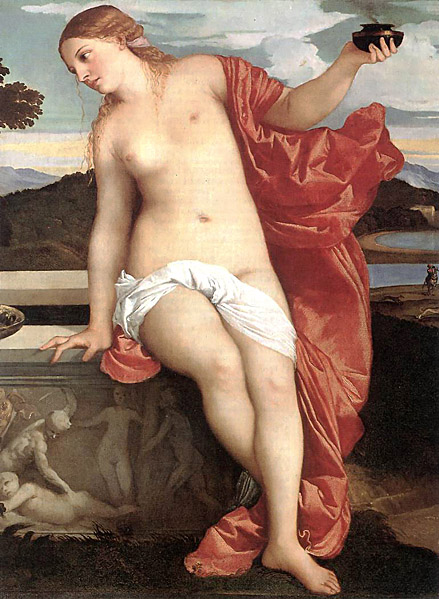

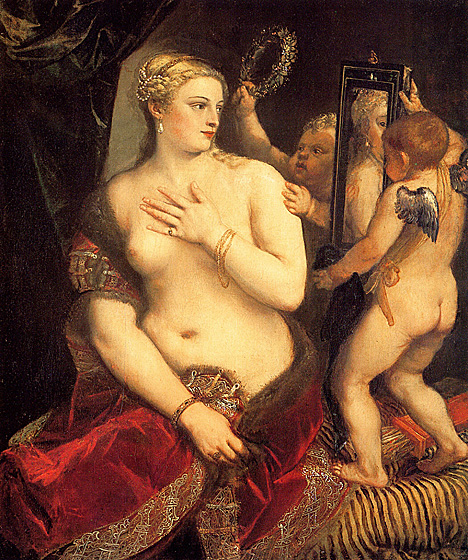

The first record of the work under its popular title is in an inventory of 1693, although scholars now discredit the theory that the two female figures are personifications of the Neoplatonic concepts of sacred and profane love. The art historian Walter Friedländer outlined similarities between the painting and Francesco Colonna's Hypnerotomachia Poliphili and proposed that the two figures represented Polia and Venere, the two female characters in the 1499 romance. It has been suggested that the scholar Pietro Bembo devised the allegorical scheme.

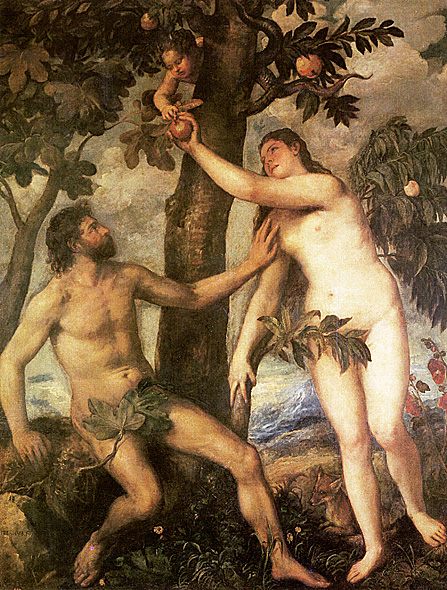

Judaism and Islam interpret the account of the fall as being simply historical, Adam and Eve's disobedience would have already been known to God even before He created them, thus draw no particular theological implications for human nature. Quite simply, because of Adam's actions, he and his wife were removed from the garden, forced to work, suffer pain in childbirth, and die. However, even after expelling them from the garden, God provided that people who honor God and follow God's laws would be rewarded, while those who acted wrongly would be punished. Some Muslims believe that Adam and Eve were clothed in the Garden and stripped when they were expelled.

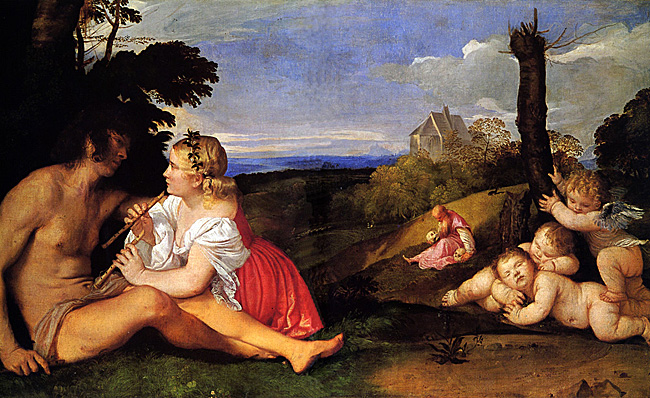

To the left, he paints the joys [and exhaustion] of youth, the firmly muscled, mature male, perhaps spent from a sexual encounter, being tantalized by a pubescent girl dressed in provocative style to further endeavors. She holds two flutes and by chance is urging him on with her piped, "Siren's song."

In the background, at the end of his days, a bearded old, stooped man gazes at two skulls, either in terror or in wonder. The exquisite detailed scenery reflects nature in her glory and decline--lofty, weightless clouds float through an azure sky. Parched trees in the foreground reflect the arid remnants of summer landscapes, as the skulls reflect those of man.

In life, we are in death, the philosopher tells us. In an age when people died so young, perhaps Titian is reflecting the same attitude by placing all of these figures in the same landscape. Perhaps the angel is not only protecting the infants, but also reminding us that in Titian's day, children died at a frightening rate, inconceivable in this modern age, and his/her home in heaven is the destination to which they will soon be transported.

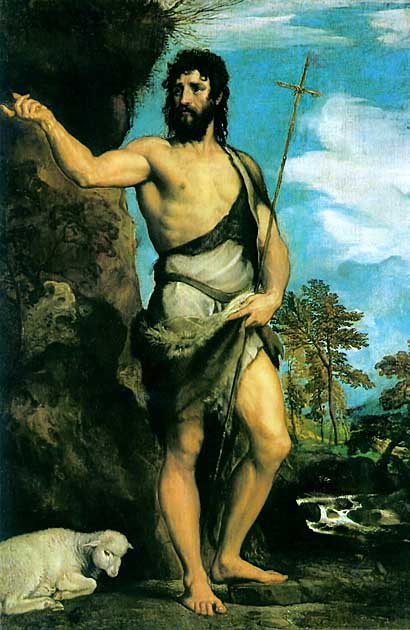

Christians traditions depict her as an icon of dangerous female seductiveness, for instance depicting her dance mentioned in the New Testament (in some later transformations it becomes another icon in the dance of the seven veils), or concentrate on her lighthearted and cold foolishness that, according to the gospels, led to John the Baptist's death.

Aged by the time he assumed the throne, he led the Republic into the Italian War of 1521, the only ally of Francis I of France that did not abandon him. Following the French defeat at the Battle of Bicocca, however, he grew concerned about the course of the war; but he died in 1523, and it was left to his successor, Andrea Gritti, to achieve a settlement with Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor.

Antonio Grimani previously fought the Ottoman Empire at the Battle of Zonchio in 1499, also known as the Battle of Sapienza of 1499 or the First Battle of Lepanto, which was a part of the Ottoman-Venetian Wars of 1499-1503.

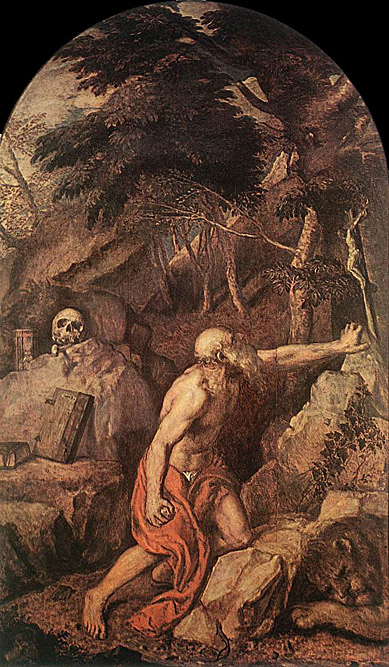

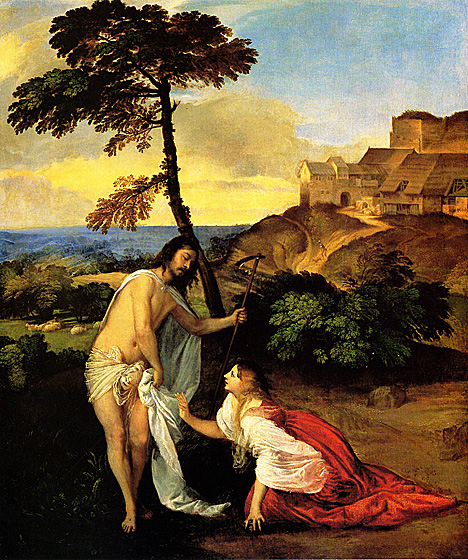

Mary Magdalene's name identifies her as being "of Magdala" - the town she came from, on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee - and thus distinguishes her from the other Marys referred to throughout the New Testament.

The life of the historical Mary Magdalene is the subject of ongoing debate, while the less-obscure development of the "penitent Megdalene", as the most beloved medieval female saint after Mary, both as an exemplar for the theological discussion of penitence and a social parable for the position and custody of women, provides matter for the social historian and the history of ideas.

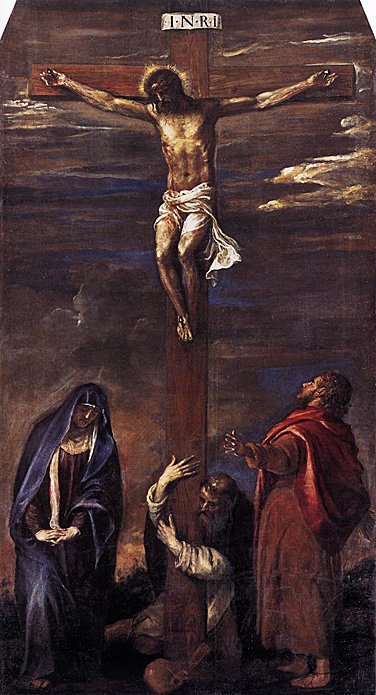

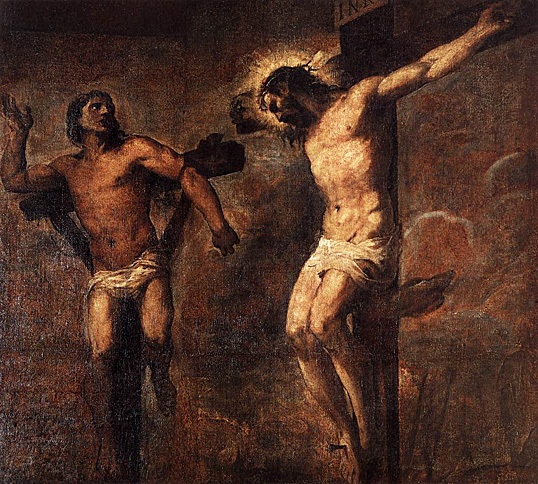

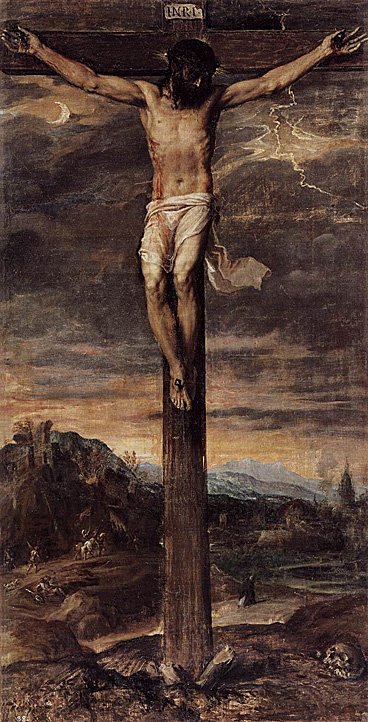

The words were a popular trope in Gregorian chant, and the moment in which they were spoken was a popular subject for paintings that relate to Resurrection appearances of Jesus.

The tale was often depicted; Titian painted Lucretia's consequent suicide and two other versions of this episode painting the dagger was originally pointing upwards; Titian repainted it to point at Lucretia presumably to make Tarquin's threat to her more obvious.

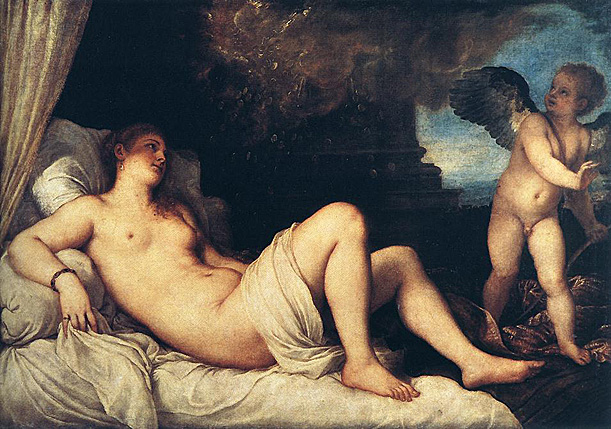

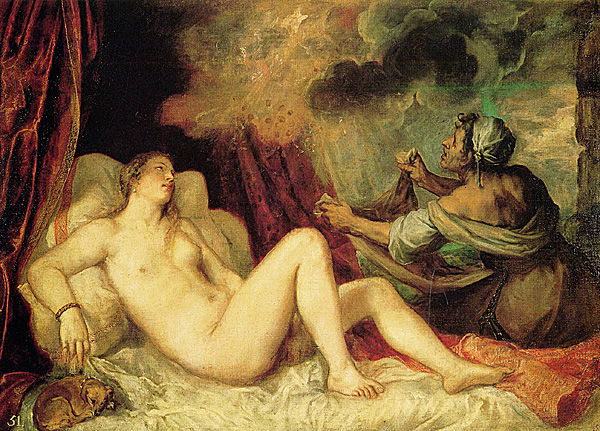

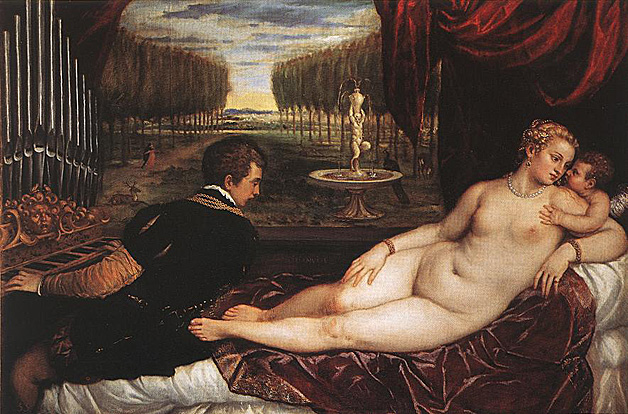

Titian described the painting as 'an invention involving greater labor and artifice than anything, perhaps, that I have produced for many years'. It was painted for his greatest patron, King Philip II of Spain, for whom he produced many other pictures including several erotic scenes.

Perseus, continuing his flight, arrived at the country of the Ethiopians, of which Cepheus was king. Cassiopeia his queen, proud of her beauty, had dared to compare herself to the Sea-Nymphs, which roused their indignation to such a degree that they sent a prodigious sea-monster to ravage the coast. To appease the deities, Cepheus was directed by the oracle to expose his daughter Andromeda to be devoured by the monster. As Perseus looked down from his aerial height he beheld Andromeda chained to a rock, and waiting the approach of the serpent. She was so pale and motionless that if it had not been for her flowing tears and her hair that moved in the breeze, he would have taken her for a marble statue. He was so startled at the sight that he almost forgot to wave his wings.

As he hovered over her he said, "O virgin, undeserving of those chains, but rather of such as bind fond lovers together, tell me, I beseech you, your name, and the name of your country, and why you are thus bound." At first she was silent from modesty, and, if she could, would have hid her face with her hands; but when he repeated his questions, for fear she might be thought guilty of some fault which she dared not tell, she disclosed her name and that of her country, and her mother's pride of beauty. Before she had done speaking, a sound was heard off upon the water, and the sea-monster appeared, with his head raised above the surface, cleaving the waves with his broad breast. Andromeda shrieked, the father and mother who had now arrived at the scene, wretched both, but the mother more justly so, stood by, not able to afford protection, but only to pour forth lamentations and to embrace the victim. Then spoke Perseus: "There will be time enough for tears; this hour is all we have for rescue.

My rank as the son of Zeus and my renown as the slayer of the Gorgon might make me acceptable as a suitor; but I will try to win her by services rendered, if the gods will only be propitious. If she be rescued by my valor, I demand that she be my reward." The parents consent (how could they hesitate?) and promise a royal dowry with her.

And now the monster was within the range of a stone thrown by a skillful slinger, when with a sudden bound the youth soared into the air. As an eagle, when from his lofty flight he sees a serpent basking in the sun, pounces upon him and seizes him by the neck to prevent him from turning his head round and using his fangs, so the youth darted down upon the back of the monster and plunged his sword into its shoulder. Irritated by the wound, the monster raised himself into the air, then plunged into the depth; then, like a wild boar surrounded by a pack of barking dogs, turned swiftly from side to side, while the youth eluded its attacks by means of his wings. Wherever he can find a passage for his sword between the scales he makes a wound, piercing now the side, now the flank, as it slopes towards the tail. The brute spouts from his nostrils water mixed with blood,. The wings of the hero are wet with it, and he dares no longer to trust to them. Alighting on a rock which rose above the waves, and holding on by a projecting fragment, as the monster floated near he gave him a death stroke. The people who had gathered on the shore shouted so that the hills reechoed the sound. The parents, transported with joy, embraced their future son-in-law, calling him their deliverer and the savior of their house, and Andromeda, both cause and reward of the contest, descended from the rock.

From Bulfinch's Mythology

"There is likewise in Phoenicia a temple of great size owned by the Sidonians. They call it the temple of Astarte. I hold this Astarte to be no other than the moon-goddess. But according to the story of one of the priests this temple is sacred to Europa, the sister of Cadmus. She was the daughter of Agenor, and on her disappearance from Earth the Phoenicians honored her with a temple and told a sacred legend about her; how that Zeus was enamored of her for her beauty, and changing his form into that of a bull carried her off into Crete. This legend I heard from other Phoenicians as well; and the coinage current among the Sidonians bears upon it the effigy of Europa sitting upon a bull, none other than Zeus. Thus they do not agree that the temple in question is sacred to Europa."

The paradox, as it seemed to Lucian, would be solved if Europa is Astarte in her guise as the full, "broad-faced" moon.

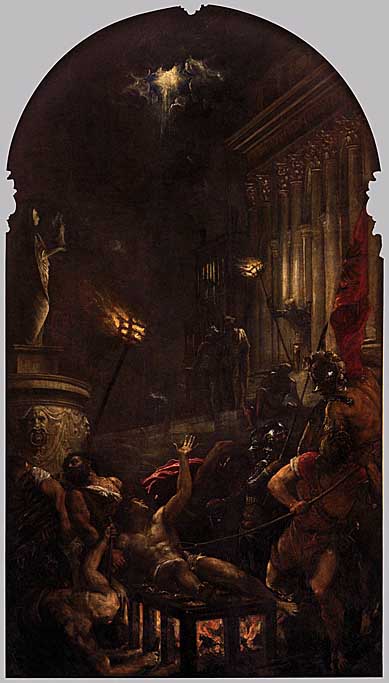

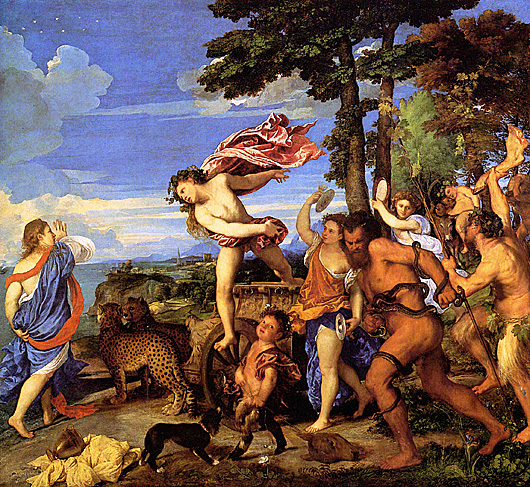

Livy informs us that the rapid spread of the cult, which he claims indulged in all kinds of crimes and political conspiracies at its nocturnal meetings, led in 186 BC to a decree of the Senate-the so-called Senatus consultum de Bacchanalibus, inscribed on a bronze tablet discovered in Apulia in Southern Italy (1640), now at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna-by which the Bacchanalia were prohibited throughout all Italy except in certain special cases which must be approved specifically by the Senate. In spite of the severe punishment inflicted on those found in violation of this decree (Livy claims there were more executions than imprisonment), the Bacchanalia survived in Southern Italy long past the repression.

Modern scholars hold Livy's account in doubt and believe that the Senate acted against the Bacchants for one or more of three reasons. First, because women occupied leadership positions in the cult (contrary to traditional Roman family values). Second, because slaves and the poor were the cult's members and were planning to overthrow the Roman government. Or third, according to a theory proposed by Erich Gruen, as a display of the Senate's supreme power to the Italian allies as well as competitors within the Roman political system, such as individual victorious generals whose popularity made them a threat to the senate's collective authority.

Flora achieved more prominence in the neo-pagan revival of Antiquity among Renaissance humanists than she had ever enjoyed in ancient Rome.

Sisyphus promoted navigation and commerce, but was avaricious and deceitful, violating the laws of hospitality by killing travelers and guests. He took pleasure in killing his guests because that would allow him to maintain his position at the top. From Homer onwards, Sisyphus was famed as the craftiest of men. He seduced his niece, took his brother's throne and betrayed Zeus's secrets (specifically, Zeus' rape of Aegina, the daughter of the river god Asopus; by some accounts, the daughter of his father Aeolus, making her either Sisyphus' sister or half-sister). Zeus then ordered Hades to chain Sisyphus in Tartarus. Sisyphus slyly asked Thanatos to try the chains to show how they worked. When Thanatos did so, Sisyphus secured them and threatened Hades. This caused an uproar, and no human could die until Ares (who was annoyed that his battles had lost their fun because his opponents would not die) intervened, freeing Thanatos and sending Sisyphus to Tartarus.

However, before Sisyphus died, he had told his wife that when he was dead she was not to offer the usual sacrifice. In the underworld he complained that his wife was neglecting him and persuaded Persephone, Queen of the Underworld, to allow him to go back to the upper world and ask his wife to perform her duty. When Sisyphus got back to Corinth, he refused to return and was eventually carried back to the underworld by Hermes. In another version of the myth, Persephone was directly persuaded that he had been conducted to Tartarus by mistake and ordered him to be freed.

.jpg)

The story of Venus and Adonis derives from Ovid's Metamorphoses. Venus, infatuated with the handsome young Adonis, knew that his passion for hunting would ultimately cause his death. Here, the powerless goddess clings to her mortal lover in a futile attempt to save his life. Adonis pulls away to pursue the hunt and tragically meets his death. The closeness of the lovers' final embrace serves as an ironic reminder of their impending, and permanent, separation.

Zeus hid Elara from his wife, Hera, by placing her deep beneath the earth. This was where she gave birth to Tityas, who is also sometimes said to be the son of Gaia, the earth goddess, for this reason. Tityos was a phallic being who grew so vast that he split his mother's womb and had to be carried to term by Gaia herself. Tityos attempted to rape Leto and was slain by Apollo and Artemis. As punishment, he was stretched out in Hades and tortured by two vultures who fed on his liver.

Jane Ellen Harrison noted that, "To the orthodox worshipper of the Olympians he was the vilest of criminals; as such Homer knew him":

I saw Tityus too,

son of the mighty Goddess Earth-sprawling there

on the ground, spread over nine acres-two vultures

hunched on either side of him, digging into his liver,

beaking deep in the blood-sac, and he with his frantic hands

could never beat them off, for he had once dragged off

the famous consort of Zeus in all her glory,

Leto, threading her way toward Pytho's ridge

over the lovely dancing-rings of Panopeus".

(Robert Fagles' translation)

Source: Web Gallery of Art

Source: Art Renewal Center

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.