Disclaimer

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci

Renaissance Artist and Humanist

1452 - 1519

Self Portrait: ca 1512

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci was an Italian Renaissance Scholar (Man): painter, sculptor, architect, musician, scientist, mathematician, engineer, inventor, anatomist, geologist, cartographer, botanist, and writer. His genius, perhaps more than that of any other figure, epitomized the Renaissance humanist ideal. Leonardo has often been described as the archetype of the Renaissance Man, a man of "unquenchable curiosity" and "feverishly inventive imagination". He is widely considered to be one of the greatest painters of all time and perhaps the most diversely talented person ever to have lived. According to art historian Helen Gardner, the scope and depth of his interests were without precedent and "his mind and personality seem to us superhuman, the man himself mysterious and remote". Marco Rosci states that while there is much speculation about Leonardo, his vision of the world is essentially logical rather than mysterious, and that the empirical methods he employed were unusual for his time.

Born out of wedlock to a notary, Piero da Vinci, and a peasant woman, Caterina, at Vinci in the region of Florence, Leonardo was educated in the studio of the renowned Florentine painter, Verrocchio. Much of his earlier working life was spent in the service of Ludovico il Moro in Milan. He later worked in Rome, Bologna and Venice, and he spent his last years in France at the home awarded him by Francis I.

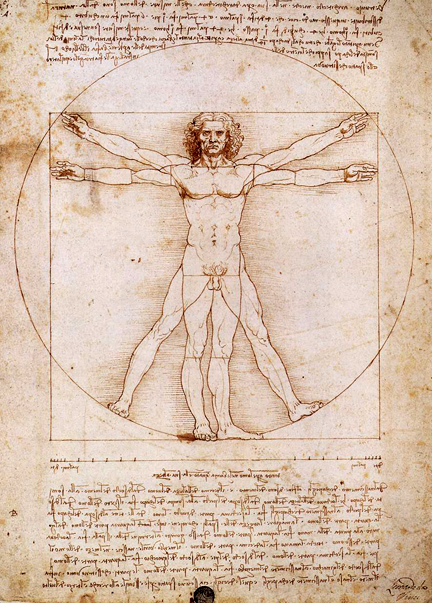

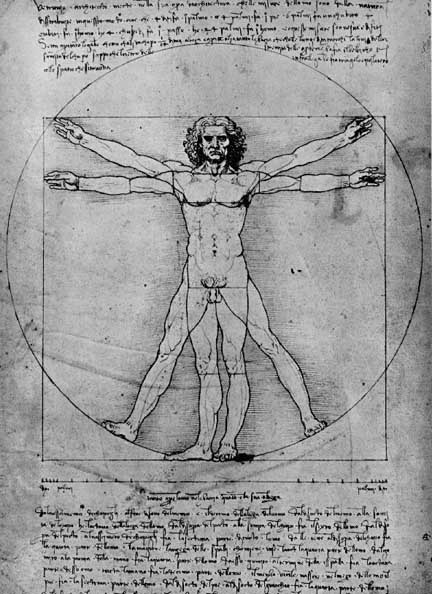

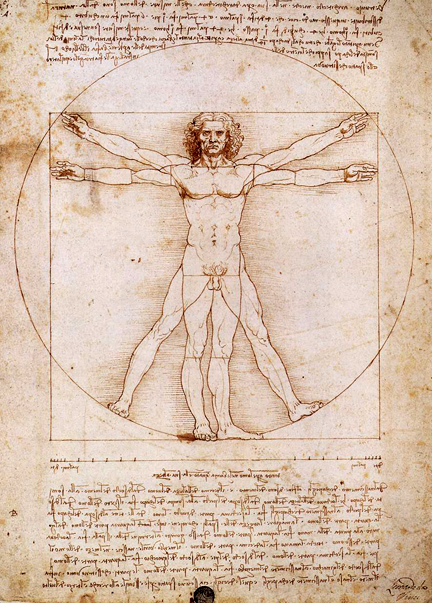

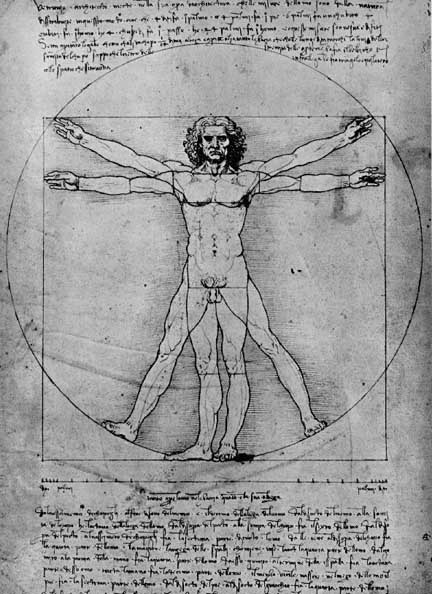

Leonardo was and is renowned primarily as a painter. Among his works, the Mona Lisa is the most famous and most parodied portrait and The Last Supper the most reproduced religious painting of all time, with their fame approached only by Michelangelo's The Creation of Adam. Leonardo's drawing of the Vitruvian Man is also regarded as a cultural icon, being reproduced on items as varied as the euro, textbooks, and T-shirts. Perhaps fifteen of his paintings survive, the small number because of his constant, and frequently disastrous, experimentation with new techniques, and his chronic procrastination. Nevertheless, these few works, together with his notebooks, which contain drawings, scientific diagrams, and his thoughts on the nature of painting, compose a contribution to later generations of artists rivaled only by that of his contemporary, Michelangelo.

Vitruvian Man: 1492

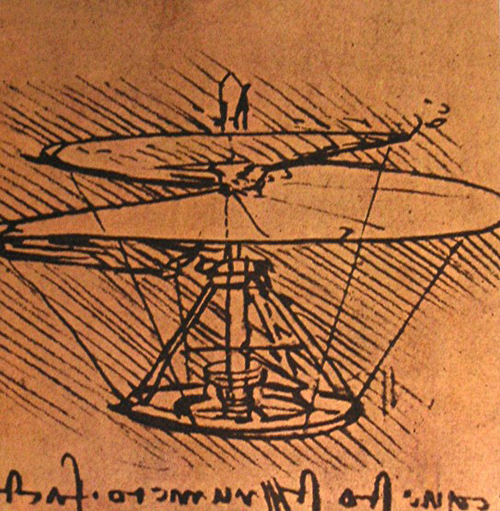

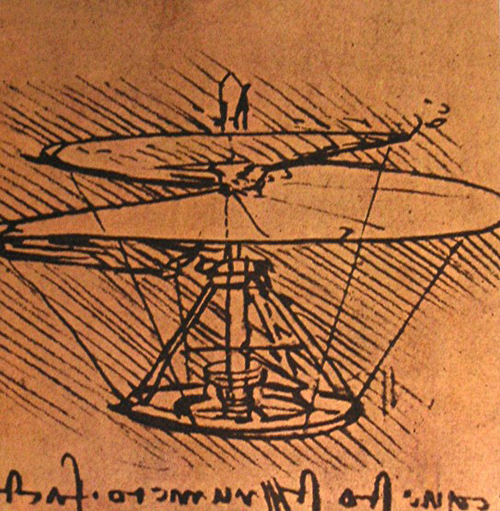

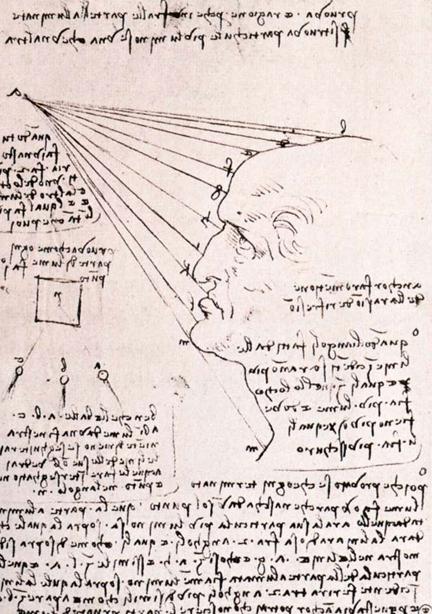

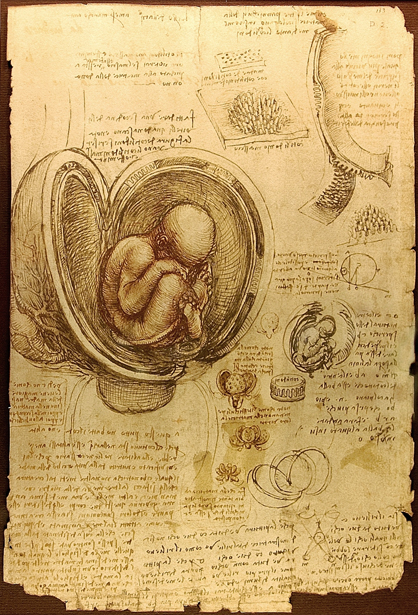

Leonardo is revered for his technological ingenuity. He conceptualized a helicopter, a tank, concentrated solar power, a calculator, and the double hull, and he outlined a rudimentary theory of plate tectonics. Relatively few of his designs were constructed or were even feasible during his lifetime, but some of his smaller inventions, such as an automated bobbin winder and a machine for testing the tensile strength of wire, entered the world of manufacturing unheralded. He made important discoveries in anatomy, civil engineering, optics, and hydrodynamics, but he did not publish his findings and they had no direct influence on later science.

Design for a Helicopter

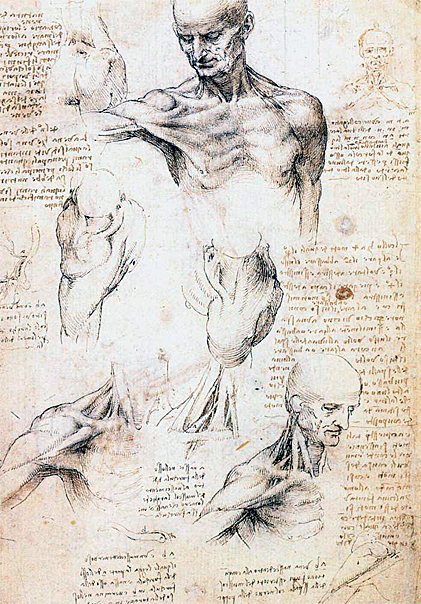

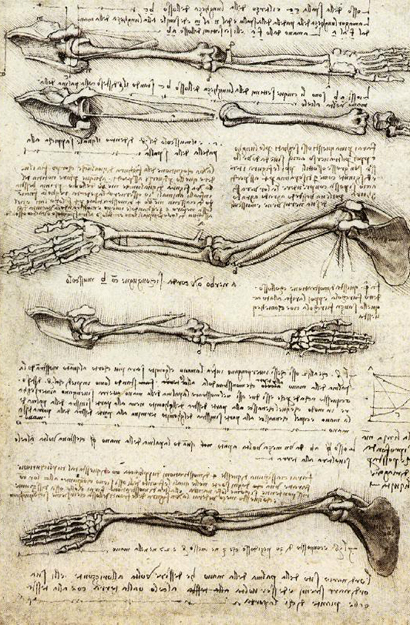

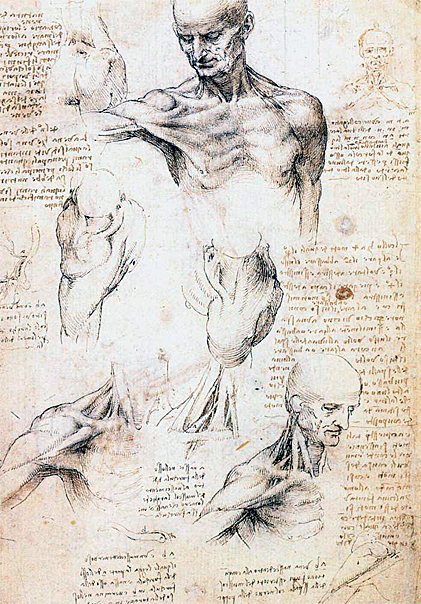

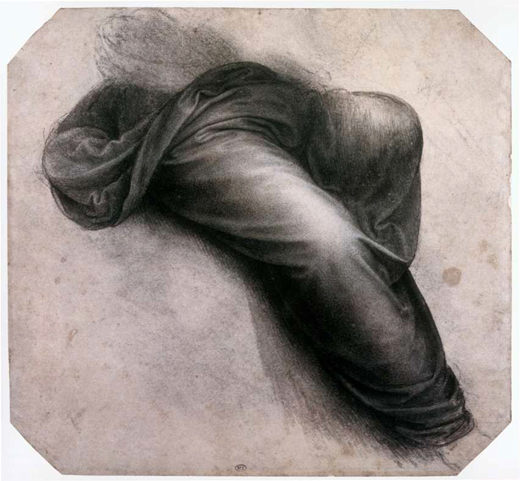

Anatomical Studies of a Male Shoulder: 1509-10

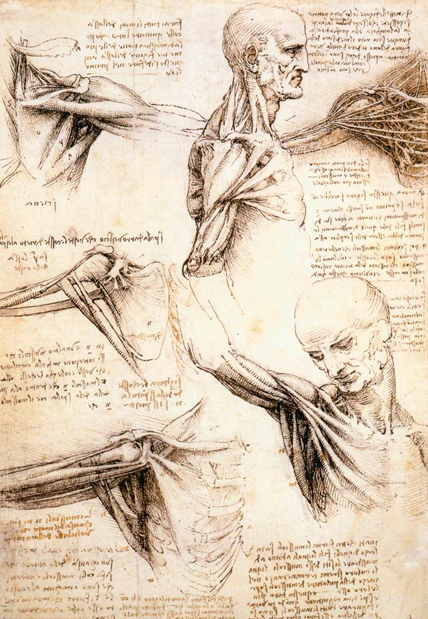

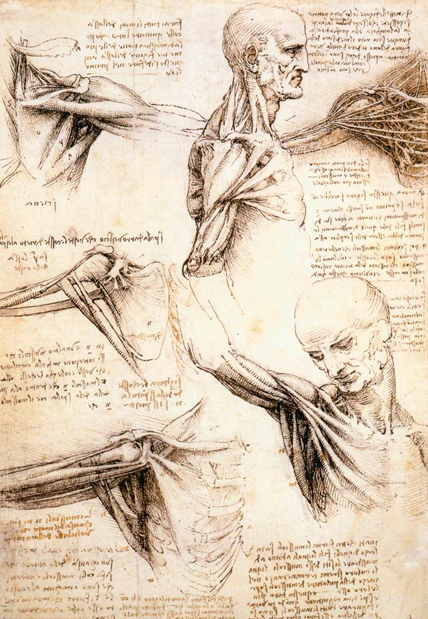

Anatomical Studies of the Shoulder: 1510-11

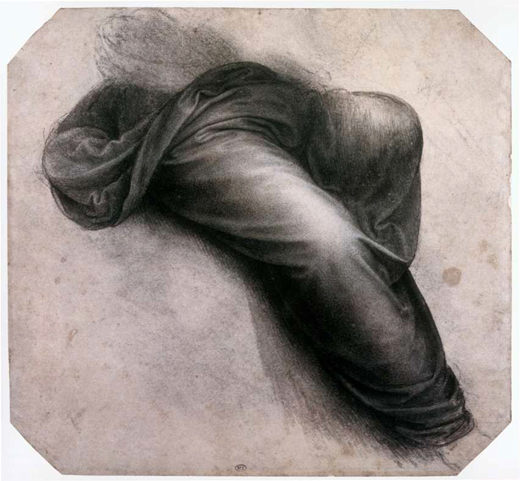

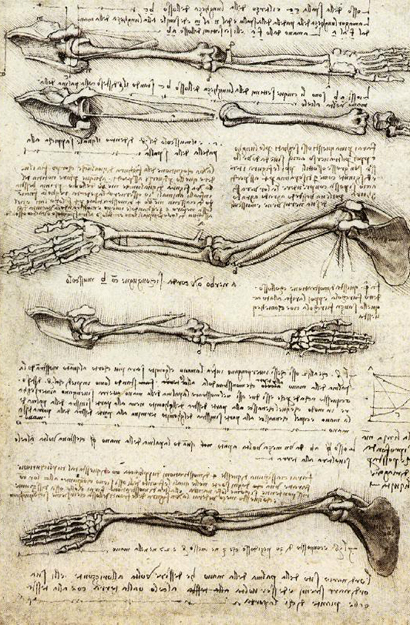

Anatomical Study of the Arm: ca 1510

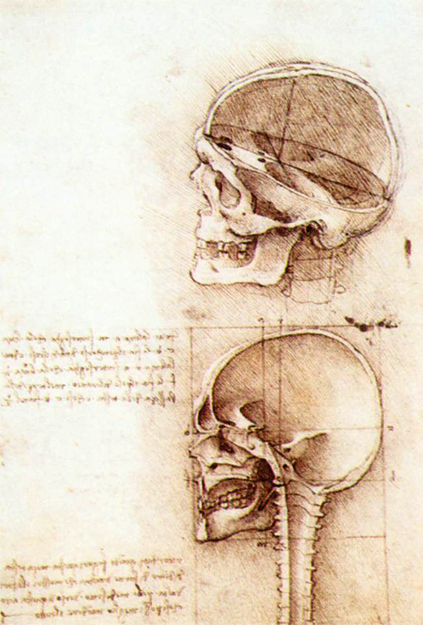

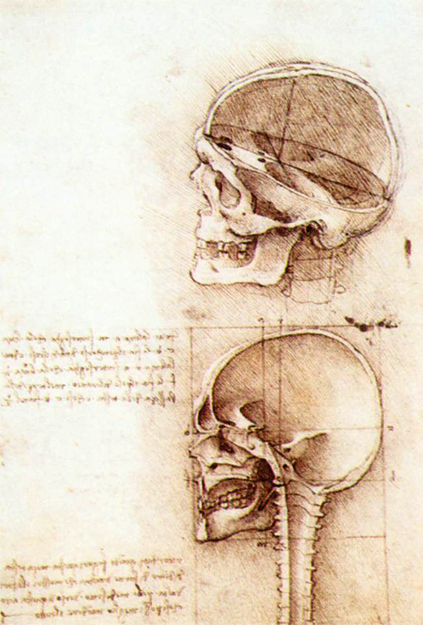

Studies of the Human Skull: 1489

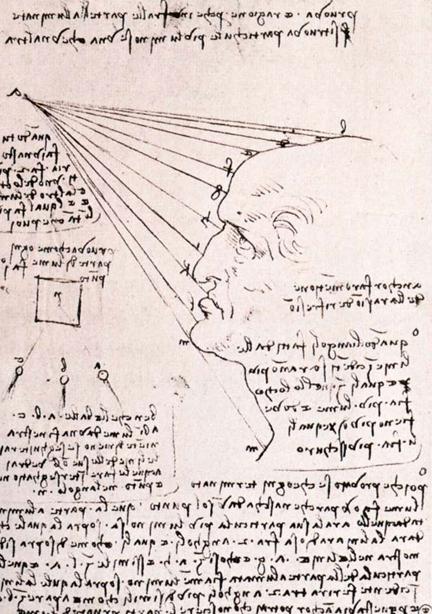

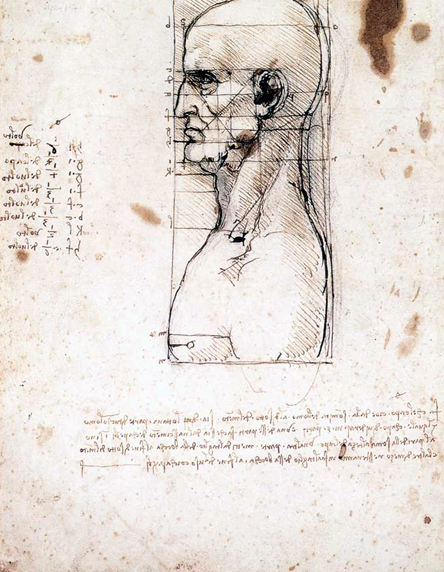

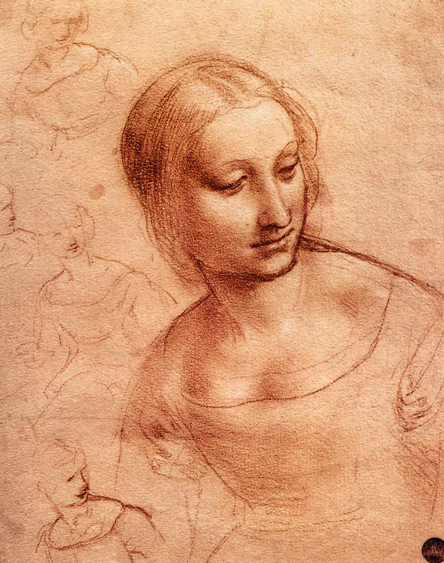

Study of the Effect of Light on a Profile Head (facsimile): 1487-90

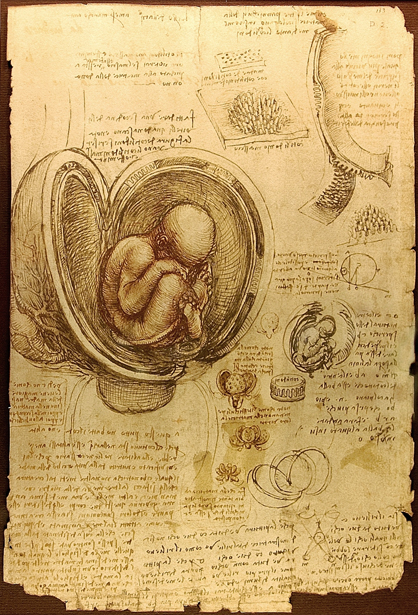

Studies of Embryos: 1510-13

Childhood, 1452-66

Leonardo was born on April 15, 1452, "at the third hour of the night" in the Tuscan hill town of Vinci, in the lower valley of the Arno River in the territory of the Medici-ruled Republic of Florence. He was the out-of-wedlock son of the wealthy Messer Piero Fruosino di Antonio da Vinci, a Florentine legal notary, and Caterina, a peasant. Leonardo had no surname in the modern sense, "da Vinci" simply meaning "of Vinci": his full birth name was "Lionardo di ser Piero da Vinci", meaning "Leonardo, (son) of (Mes)ser Piero from Vinci". The inclusion of the title "ser" indicated that Leonardo's father was a gentleman.

Little is known about Leonardo's early life. He spent his first five years in the hamlet of Anchiano in the home of his mother, then from 1457 he lived in the household of his father, grandparents and uncle, Francesco, in the small town of Vinci. His father had married a sixteen-year-old girl named Albiera, who loved Leonardo but died young. When Leonardo was sixteen, his father married again, to twenty-year-old Francesca Lanfredini. It was not until his third and fourth marriages that Ser Piero produced legitimate heirs.

Leonardo's Home in Anchiano

Leonardo received an informal education in Latin, geometry and mathematics. In later life, Leonardo recorded only two childhood incidents. One, which he regarded as an omen, was when a kite dropped from the sky and hovered over his cradle, its tail feathers brushing his face. The second occurred while exploring in the mountains. He discovered a cave and was both terrified that some great monster might lurk there and driven by curiosity to find out what was inside.

Leonardo's early life has been the subject of historical conjecture. Vasari, the 16th-century biographer of Renaissance painters, tells of how a local peasant made himself a round shield and requested that Ser Piero have it painted for him. Leonardo responded with a painting of a monster spitting fire which was so terrifying that Ser Piero sold it to a Florentine art dealer, who sold it to the Duke of Milan. Meanwhile, having made a profit, Ser Piero bought a shield decorated with a heart pierced by an arrow, which he gave to the peasant.

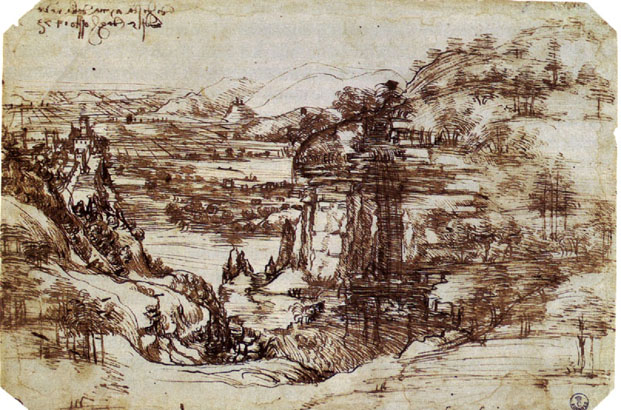

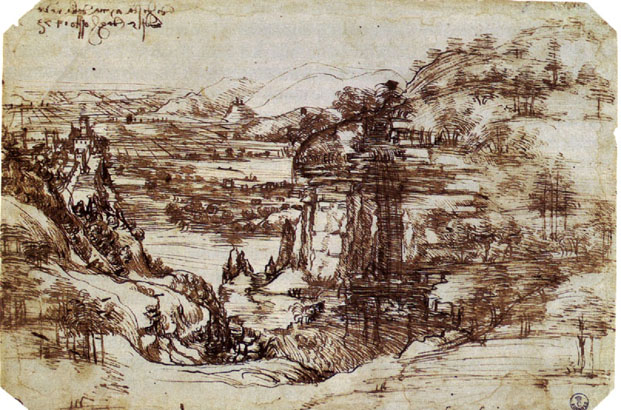

Leonardo's earliest known drawing, the Arno Valley: ca 1473

Verrocchio's Workshop, 1466-76

In 1466, at the age of fourteen, Leonardo was apprenticed to the artist Andrea di Cione, known as Verrocchio, whose workshop was "one of the finest in Florence". Other famous painters apprenticed or associated with the workshop include Domenico Ghirlandaio, Perugino, Botticelli, and Lorenzo di Credi. Leonardo would have been exposed to both theoretical training and a vast range of technical skills including drafting, chemistry, metallurgy, metal working, plaster casting, leather working, mechanics and carpentry as well as the artistic skills of drawing, painting, sculpting and modeling.

Much of the painted production of Verrocchio's workshop was done by his employees. According to Vasari, Leonardo collaborated with Verrocchio on his The Baptism of Christ, painting the young angel holding Jesus' robe in a manner that was so far superior to his master's that Verrocchio put down his brush and never painted again. On close examination, the painting reveals much that has been painted or touched up over the tempera using the new technique of oil paint, with the landscape, the rocks that can be seen through the brown mountain stream and much of the figure of Jesus bearing witness to the hand of Leonardo. Leonardo may have been the model for two works by Verrocchio: the bronze statue of David in the Bargello and the Archangel Raphael in Tobias and the Angel.

By 1472, at the age of twenty, Leonardo qualified as a master in the Guild of Saint Luke, the guild of artists and doctors of medicine, but even after his father set him up in his own workshop, his attachment to Verrocchio was such that he continued to collaborate with him. Leonardo's earliest known dated work is a drawing in pen and ink of the Arno valley, drawn on August 5, 1473.

The Baptism of Christ: ca 1475

The Baptism of Christ (Detail): 1472-75

When Leonardo worked under Verrocchio he participated in many works including Verrocchio's The Baptism of Christ. The gentle modeling of the left angel's head and the fact that the paint at this point contains oil supports the general attribution of this section to Leonardo. The painting was probably produced for the church of San Salvi in Florence and was mentioned as early as 1510 by Albertini, who stated that Leonardo painted the angel's head. A drawing of the angel's head is kept in Turin.

Quoted From: The Web Gallery of Art

Professional Life, 1476-1513

Florentine court records of 1476 show that Leonardo and three other young men were charged with sodomy and acquitted. From that date until 1478 there is no record of his work or even of his whereabouts. In 1478 he left Verrocchio's studio and was no longer resident at his father's house. One writer, the "Anonimo" Gaddiano claims that in 1480 he was living with the Medici and working in the Garden of the Piazza San Marco in Florence, a Neo-Platonic academy of artists, poets and philosophers that the Medici had established. In January 1478, he received his first of two independent commissions: to paint an Altarpiece for the Chapel of Saint Bernard in the Palazzo Vecchio and, in March 1481, The Adoration of the Magi for the monks of San Donato a Scopeto. Neither commission was completed, the second being interrupted when Leonardo went to Milan.

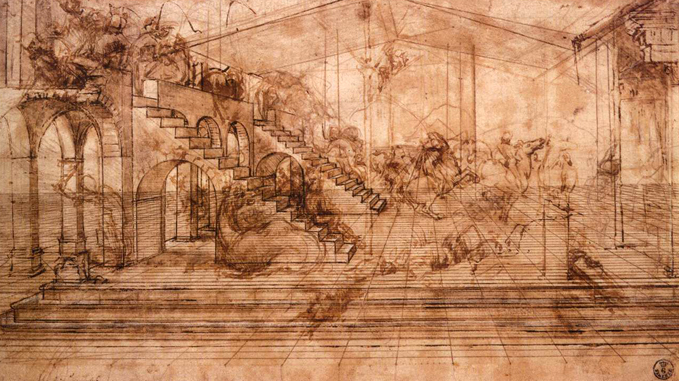

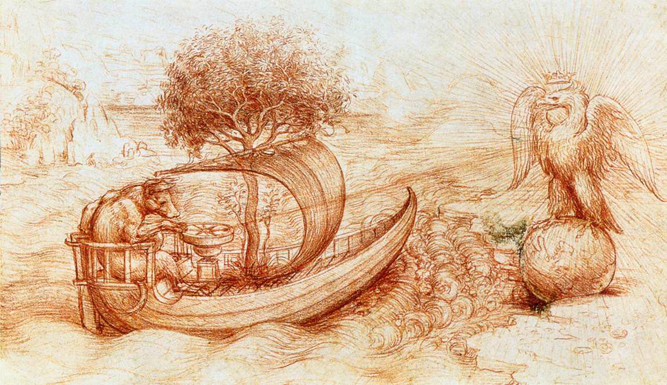

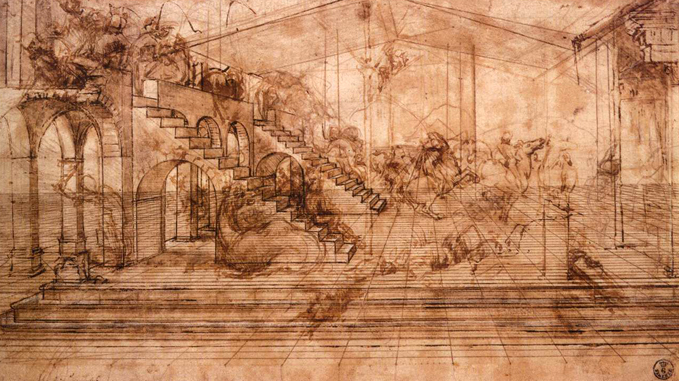

Adoration of the Magi: 1481-82

Since the Early Christian era, the 6 January has been celebrated as the feast of Epiphany, the appearance of God amongst men in the form of Jesus Christ. Mankind is represented by the Three Kings, who are paying homage to the Messiah. The fall of the pagan world began at the same time as his appearance. Leonardo appears to have depicted this moment, so dramatic in human history, in his panel. It remained unfinished because Leonardo left Florence and moved to Milan, though we do not know why he did so. Chemical reactions and soiling mean it is now difficult to read this fascinating panel in detail.

With this painting Leonardo declares his independence from Verrocchio, emerging with a fresh, personal style. Although unfinished, this painting is far more innovative than his previous works. The composition is constructed around a central, pyramidal grouping of figures, and, most significantly, Leonardo here incorporates lights and darks in the under drawing of this painting.

Even though the panel remained unfinished, the Adoration of the Magi, with its symmetrically composed main group which differs from the traditional linear composition, is now considered one of the most progressive works in Florentine painting. It puts into practice the demands Alberti made of history paintings in a way no other work in its era does. All the figures are involved in the events in the picture. The distinguished kings display their emotions in a more dignified manner than the accompanying figures around them, and the overall number of participants is kept within moderation. The figures are grouped in a circle around Mary and are expressing, with more or less vigorous gestures, their emotion at the first demonstration of divinity of the Christ Child.

The painting also differs from the traditional way of depicting the Adoration in Florence by means of the puzzling scenes in the background, the equestrian battles and an unfinished staircase. This led to the assumption that the Augustinian convent of San Donato in Scopeto, which had commissioned the picture, wanted to use this picture composition in order to convey its own theological interpretation of the Adoration theme.

Quoted From: The Web Gallery of Art

In 1482 Leonardo, who according to Vasari was a most talented musician, created a silver lyre in the shape of a horse's head. Lorenzo de' Medici sent Leonardo to Milan, bearing the lyre as a gift, to secure peace with Ludovico Sforza, Duke of Milan. At this time Leonardo wrote an often-quoted letter describing the many marvelous and diverse things that he could achieve in the field of engineering and informing Ludovico that he could also paint.

Study of a Horse from Leonardo's Journals

Leonardo worked in Milan from 1482 until 1499. He was commissioned to paint The Virgin of the Rocks for the Confraternity of the Immaculate Conception and The Last Supper for the monastery of Santa Maria delle Grazie. Between 1493 and 1495 Leonardo listed a woman called Caterina among his dependents in his taxation documents. When she died in 1495, the list of funeral expenditures suggests that she was his mother.

Virgin of the Rocks: 1483-86

There are two versions of the Virgin of the Rocks, one (the earlier) in the Louvre, Paris and another in the National Gallery, London.

Virgin of the Rocks: 1495-1508

The first work that Leonardo executed in Milan is the so-called Virgin of the Rocks, which actually expresses the theme of the Immaculate Conception, the dogma that affirms Mary was conceived without original sin. The name of the picture reflects an iconographical peculiarity: the religious figures are depicted in a rocky grotto, in which they are sitting on a stone floor. The figures are subjected to a strict spatial arrangement called a pyramidal composition. The painting had a considerable influence on Leonardo's artistic colleagues in Lombardy.

This canvas was to decorate the Ancona (a carved wooden altar with frames where paintings were inserted) in the chapel of the Immacolata in the church of San Francesco Grande in Milan. On 25 April 1483, the members of the Confraternity of the Conception assigned the work of the paintings (a Virgin and Child in the center and two Angel-Musicians for the sides), to Leonardo, for the most important part, and the brothers Ambrogio and Evangelista De Predis, for the side panels. Scholars now feel that the two canvases on this same subject, one in the Louvre and the other in London's National Gallery, are simply two versions of the same painting, with significant variants.

The Paris Virgin of the Rocks, entirely by Leonardo, is the one which first adorned the altar in San Francesco Grande. It may have been given by Leonardo himself to King Louis XII of France, in gratitude for the settlement of the suit between the painters and those who commissioned the works, in dispute over the question of payment. The later London painting replaced this one in the Ancona.

For the first time Leonardo could achieve in painting that intellectual program of fusion between human forms and nature which was slowly taking shape in his view of his art. Here there are no thrones or architectural structures to afford a spatial frame for the figures; instead there are the rocks of a grotto, reflected in limpid waters, decorated by leaves of various kinds from different plants while in the distance, as if emerging from a mist composed of very fine droplets and filtered by the golden sunlight, the peaks of those mountains we now know so well reappear. This same light reveals the gentle, mild features of the Madonna, the angel's smiling face, the plump, pink flesh of the two putti.

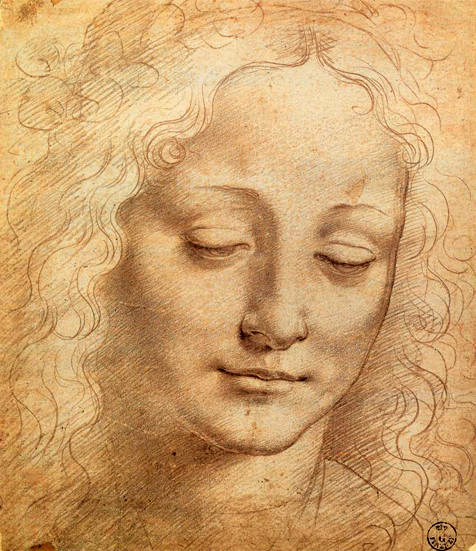

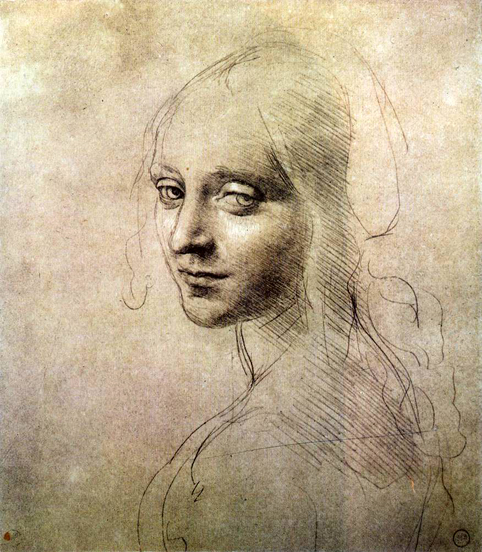

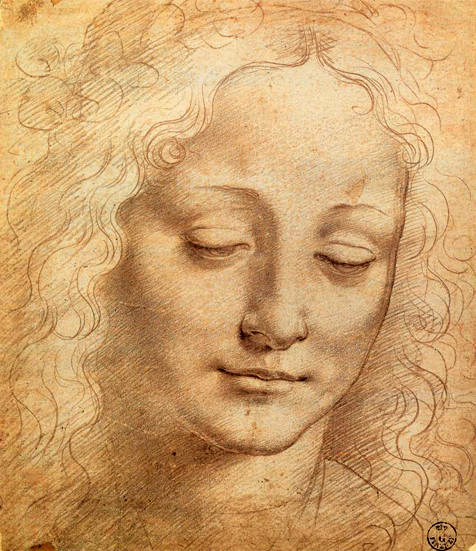

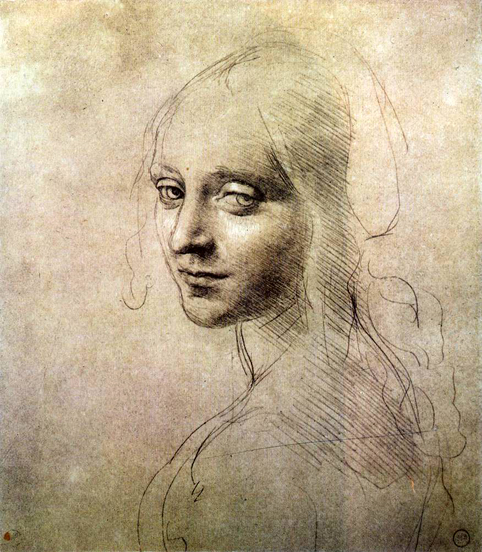

For this work, too, Leonardo made numerous studies, and the figurative expression is slowly adapted to the program of depiction. In fact, the drawing of the face of the angel is, in the sketch, clearly feminine, with a fascination that has nothing ambiguous about it. In the painting, the sex is not defined, and the angel could easily be either a youth or a maiden.

Quoted From: The Web Gallery of Art

Virgin of the Rocks (Detail 1): 1483-86

In contrast with traditional iconography, Leonardo has not conceived Mary and the Christ Child as a closely united group, but has placed Jesus beneath his mother's hand next to an angel on the right side of the picture. In accordance with the composition of the group of figures which are connected to each other by means of glances and gestures, the angel has embraced him and is looking at him; his finger, however, is pointing at the small St. John in the Mother of God's arms who is adoring the Christ Child, whose hand is raised in blessing, entirely in the traditional manner.

Quoted From: The Web Gallery of Art

Virgin of the Rocks (Detail 2): 1483-86

In contrast with traditional iconography, Leonardo has not conceived Mary and the Christ Child as a closely united group, but has placed Jesus beneath his mother's hand next to an angel on the right side of the picture. In accordance with the composition of the group of figures which are connected to each other by means of glances and gestures, the angel has embraced him and is looking at him; his finger, however, is pointing at the small St. John in the Mother of God's arms who is adoring the Christ Child, whose hand is raised in blessing, entirely in the traditional manner.

Quoted From: The Web Gallery of Art

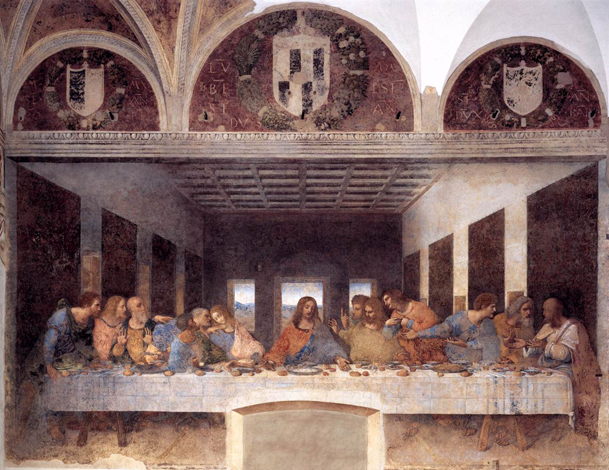

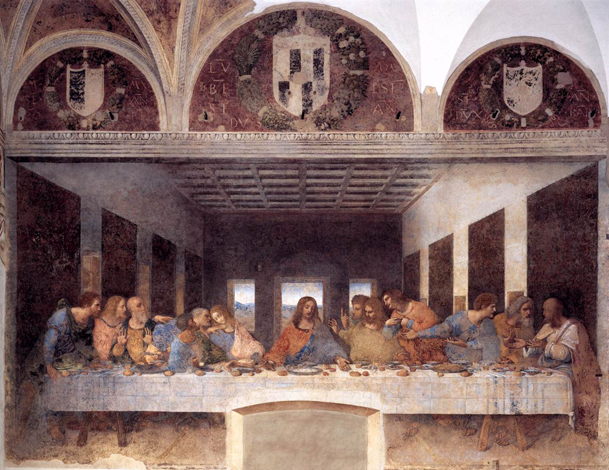

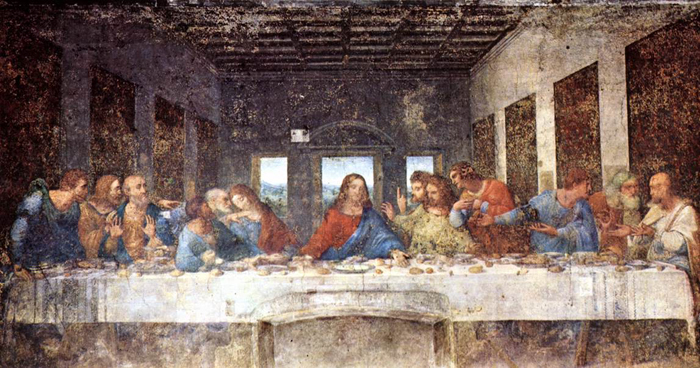

The Last Supper for the Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan - 1498

The Refectory with the Last Supper after Restoration: 1498

After Ludovico il Moro was made duke of Milan in 1494, he decided to make the monastery of Santa Maria delle Grazie his family's burial place. This is the context within which Leonardo was probably commissioned to decorate the monks' dining room, the refectory, with a depiction of the Last Supper. It cannot be determined exactly when the commission went to Leonardo, however, the completion of the painting in 1498 is documented.

Leonardo's Last Supper is indisputably one of the most famous and important works in the history of painting. The quality of the wall painting was recognized within a very short space of time after its completion; copies were produced of it and its praises were sung in contemporary sources. After conquering Milan in 1499, the French king is even said to have expressed the desire to bring it to France, but his advisors were apparently able to dissuade him on the grounds that, given the technological conditions of the time, transporting the painting would have been tantamount to destroying it.

As in all his major undertakings, Leonardo sought a new technical solution for the process of painting. He decided in favor of mixed media and painted over two ground layers using oil and tempera paints, as was done in panel painting. This particular technique is partially responsible for the fact that the disintegration of the work set in so early, given the unfavorable climatic conditions.

Scarcely 20 years after the completion of the work, it was already starting to come to pieces, possibly because the wall had absorbed water. Ever since, every generation has worried and made efforts to a greater or lesser degree to preserve this work. In 1943, during an air raid, a bomb exploded in the refectory of the monastery of Santa Maria delle Grazie and destroyed the roof and the wall to the right of the Last Supper right down to the foundations; the work of art, protected by sand bags, fortunately survived this catastrophe largely unscathed. Since about 1980, extremely extensive and technologically lavish restoration work has been taking place to preserve it, made particularly necessary by increasingly destructive air pollution. This restoration followed the disputed decision to remove all over-paintings and completions of missing sections, preserving only those parts originally painted by Leonardo.

Quoted From: The Web Gallery of Art

The Last Supper: 1498

The most celebrated Last Supper was painted by Leonardo da Vinci around 1494-98 in the refectory of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan. The real dining room appears to be continued in the perspectival painted one, but on a higher level: the prior's table is upstaged by that of Christ and the apostles above. Christ and the apostles seem to have taken their place in the monk's dining hall in Milan, as it were. The emphatic gestures of the larger-than-life-size, heroic figures would have contrasted once with the quiet, controlled meal of the monks. A sublime, sacred drama overshadowed the worldly meal and focused the brothers' attention religious meditation. Leonardo depicted a specific moment of the Last Supper: Christ has just announced that he will be betrayed by one of the disciples, and the community of apostles reacts with agitation and questioning. The brothers found here a painted exemplar for their explorations of their own conscience; Judas's offence warned them not to betray the monastic community and its regulations.

Quoted From: The Web Gallery of Art

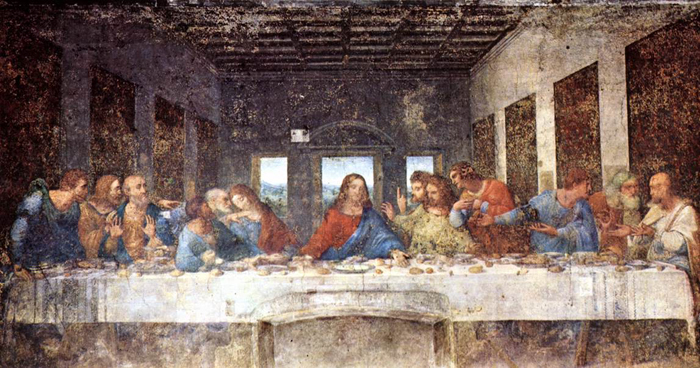

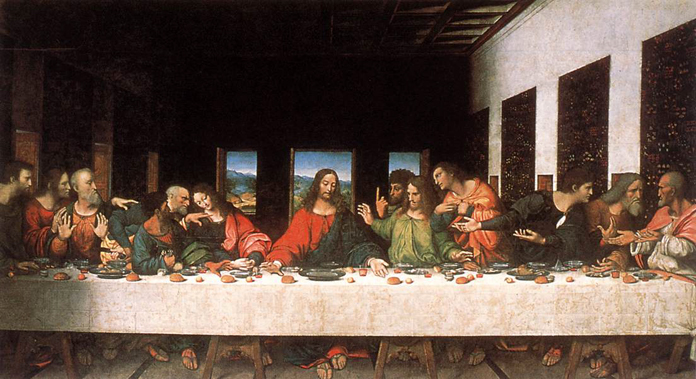

The Last Supper: 1498 (Two)

The photo was taken after the recent restoration.

There are differing opinions amongst art researchers as to which episode from the Gospels is depicted in the Last Supper. Some consider it to portray the moment at which Jesus has announced the presence of a traitor and the apostles are all reacting with astonishment, others feel that it also represents the introduction of the celebration of the Eucharist by Jesus, who is pointing to the bread and wine with his hands. And yet others feel it depicts the moment when Judas, by reaching for the bread at the same moment as Jesus as related in the Gospel of St Luke (22:21), reveals himself to be the traitor. In the end, none of the interpretations is convincing.

Leonardo's Last Supper is not a depiction of a simple or sequential action, but interweaves the individual events narrated in the Gospels, from the announcement of the presence of a traitor to the introduction of the Eucharist, to such an extent that the moment depicted is a meeting of the two events. As a result, the disciples' reactions relate both to the past and subsequent events. At the same time, however, the introduction of the Eucharist clearly remains the central event.

The Apostles from left to right: Bartholomew, James the Less, Andrew, Judas, Peter, John, Christ, Thomas, James the Greater, Philip, Matthew, Thaddeus, Simon.

Quoted From: The Web Gallery of Art

The Last Supper: 1498 (Three)

Leonardo's painting of the Last Supper was constructed symmetrically according to the laws of central perspective, with a main figure, Jesus, in the center. He is physically and psychologically isolated from the other figures and with his hands is pointing to the bread and wine, making the introduction of the Eucharist the central event. In Leonardo's conception, the other figures are reacting directly to Jesus, and at the same time, some of them are coming into contact with each other.

James the Great, whose mouth is opened in astonishment, is sitting on the right next to Jesus, and spreading out his arms as if trying to say to the two disciples behind him, who are attempting to command the attention of Jesus with their eloquent gestures and the way they are pushing forward, that they should be quiet and listen.

James the Less, the second from the left, places his hand on Peter's back, while Andrew next to him is still holding his hands before him and speaking, but his eyes are already seeking out Jesus. Peter and John are facing each other deep in conversation, just like the group of three on the far right who still seem to be animatedly discussing the previous announcement of the existence of a traitor.

That this announcement has indeed already taken place is proven by the behavior of John and Peter. In contrast with the usual manner of depiction, in which John is lying against Christ's chest, here Leonardo refers to the Gospel of St John (13:24): "Simon Peter therefore beckoned to him, that he should ask who it should be of whom he spoke."

By combining these two apostles into a group with Judas in this manner, Leonardo was distancing himself from the traditional scheme of depiction used for Last Suppers, according to which Peter and John sat to the right and left of Jesus. In contrast to the other apostles, however, he characterized them so clearly that they are identifiable to the observer. He identified Peter by means of the threatening dagger that he would, at dawn, use to cut off the ear of Malchus, one of the soldiers arresting Jesus.

John, the favorite disciple, is wearing red and blue garments as is Jesus, and is seated at his right hand, the most honorable place. But Judas above all was clearly characterized by Leonardo, for he was not, as was customary, placed in the center of the picture in front of the table, but placed amongst the row of disciples. He is identified by means of several motifs such as his reaching for the bread, the purse containing the reward for his treachery and the knocking over of a saltcellar, a sign of misfortune. Leonardo even formally expressed his isolation from the group by depicting him as the only one whose upper body is leaning against the table, shrinking back from Jesus.

Quoted From: The Web Gallery of Art

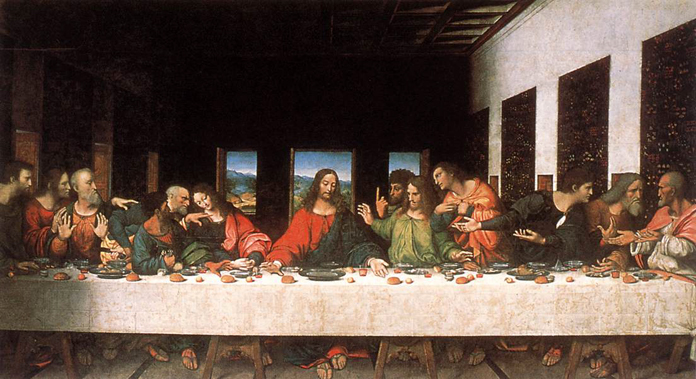

Last Supper: 16th Century Copy

This copy, made on canvas in approximately original size by an unknown painter in the 16th century, reveals many details which can no longer be detected due to the deterioration of the fresco.

Quoted From: The Web Gallery of Art

Leonardo was employed on many different projects for Ludovico, including the preparation of floats and pageants for special occasions, designs for a dome for Milan Cathedral and a model for a huge equestrian monument to Francesco Sforza, Ludovico's predecessor. Seventy tons of bronze were set aside for casting it. The monument remained unfinished for several years, which was not unusual for Leonardo. In 1492 the clay model of the horse was completed. It surpassed in size the only two large equestrian statues of the Renaissance, Donatello's Gattemelata in Padua and Verrocchio's Bartolomeo Colleoni in Venice, and became known as the "Gran Cavallo". Leonardo began making detailed plans for its casting; however, Michelangelo insulted Leonardo by implying that he was unable to cast it. In November 1494 Ludovico gave the bronze to be used for cannon to defend the city from invasion by Charles VIII.

At the start of the Second Italian War in 1499, the invading French troops used the life-size clay model for the "Gran Cavallo" for target practice. With Ludovico Sforza overthrown, Leonardo, with his assistant Salai and friend, the mathematician Luca Pacioli, fled Milan for Venice where he was employed as a military architect and engineer, devising methods to defend the city from naval attack. On his return to Florence in 1500, he and his household were guests of the Servite monks at the monastery of Santissima Annunziata and were provided with a workshop where, according to Vasari, Leonardo created the cartoon of The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne and Saint John the Baptist, a work that won such admiration that "men and women, young and old" flocked to see it "as if they were attending a great festival".

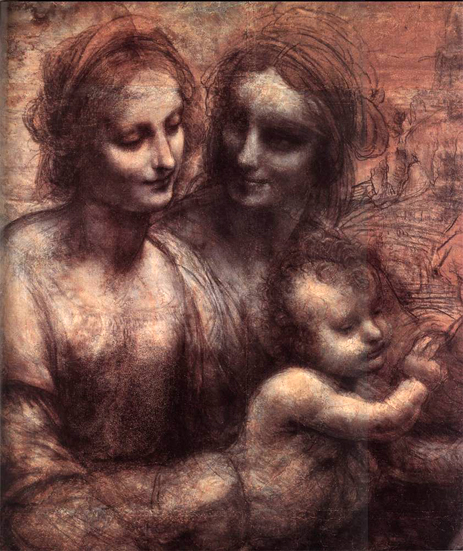

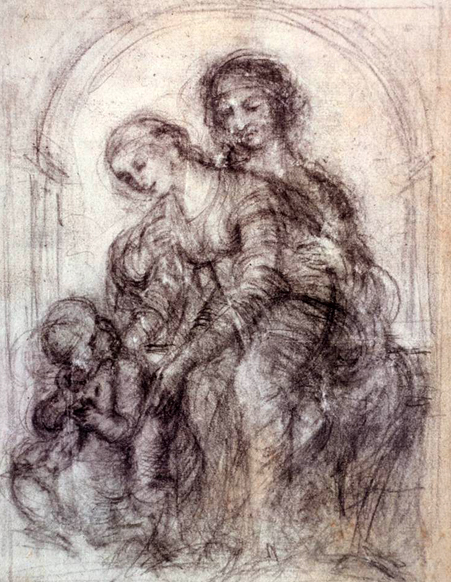

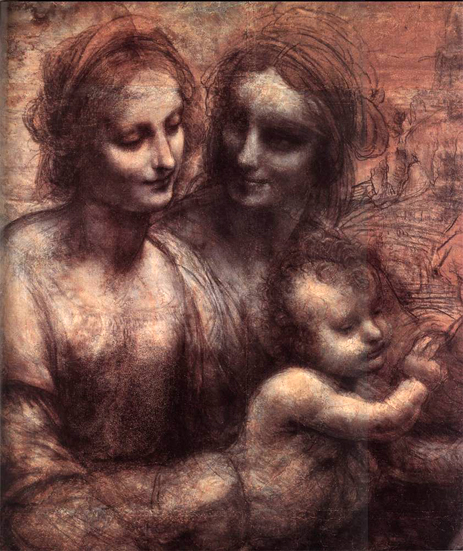

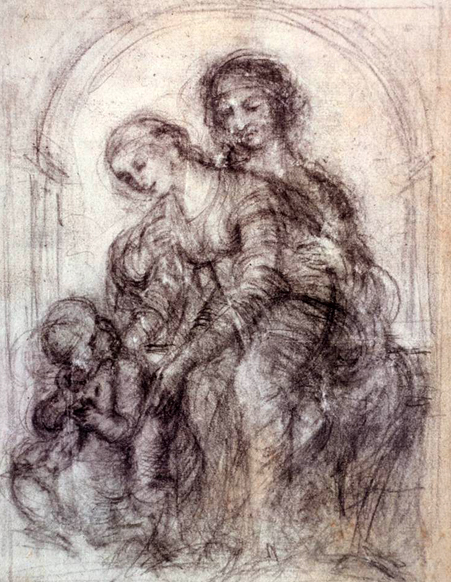

Madonna and Child with Saint Anne and the Young Saint John: 1507-08

The cartoon of the Madonna and Child with St Anne and the young St John is also referred to as Burlington House cartoon. In 1986, a vandal shot at the cartoon and severely damaged it around the area of Mary's chest. Restorers had an opportunity to examine the cartoon while repairing it. They could discover no sign on it that it was used either by Leonardo or any other artist at a later date for transferring the design to another medium. In the Pinacoteca Ambrosiana is a Holy Family attributed to Bernardino Luini. It corresponds precisely to the figural composition of the London cartoon, with the exception that Joseph is added in the background on the right.

One of the most precious and fragile works in the National Gallery, the cartoon now hangs in a specially built recess in the wall of a darkened little room. The drawing covers eight sheets of paper glued together. A reduced light level is necessary to prevent the chalk and charcoal from fading, but the reverential atmosphere it creates seems appropriate. As in the Virgin of the Rocks Leonardo has represented four figures in rapt communion charged with theological significance and intense human emotion. Shared glances and introspective smiles play across their faces, enigmatic expressions which Leonardo made famous.

The open triangle formed by the figures in the Virgin of the Rocks is here condensed into a pyramid of interlocking forms; the figures increase in scale and the rocky landscape recedes into the distance, leaving only pebbles in the foreground. Despite the gain in monumentality nothing is conclusively resolved. Potentially awkward areas where the bodies touch and overlap were left blurred and smudged. Saint Anne's forearm, prophetically raised to Heaven, is barely sketched in. We begin to see why Leonardo found such great difficulty in bringing projects to completion, for the indeterminacy of the design and the lack of finish are integral to the significance of the work, pictorial mystery evoking divine mystery: God made flesh in the womb of a woman herself conceived without sin, the Passion foretold and accepted with melancholy joy.

Cartoons were full-size drawings made to be transferred to panel, wall or canvas to serve as a guide to painting. The National Gallery drawing was surely preparatory for a painting, but was never used for transfer, since the outlines are neither pricked nor incised. Like the Virgin of the Rocks, it is a variation on a theme which occupied Leonardo for some years. In 1501 Florentine `men and women, young and old, as if they were going to a solemn festival', had flocked to see an earlier drawing by Leonardo of similar size on a similar subject, probably made for an altarpiece to Saint Anne, one of the patrons of republican Florence, for the church of Santissima Annunziata. That altarpiece was never executed, and the drawing for it was lost.

Sometime later Leonardo was commissioned to revise the composition for King Louis XII of France, whose second wife's name, Anne, would have made the subject especially attractive. The French king's painting, begun in about 1508, was left unfinished at Leonardo's death and is now in the Louvre. It shows Anne smiling down at the Virgin on her lap, who bends over to restrain the Child playing with a lamb, symbol of Christ's sacrifice and attribute of Saint John the Baptist. Both the Paris painting and the National Gallery `cartoon' demonstrate what an eyewitness marveled at in the lost drawing of 1501: `And these figures are all as large as life, but they exist within a small cartoon, because they are either seated or in curved poses and each is a certain amount in front of the other...' It was Leonardo's supreme gift to resolve a formal problem in many different, but equally evocative, ways.

Quoted From: The Web Gallery of Art

Madonna and Child with Saint Anne and the Young Saint John (Detail): 1507-08

In Cesena, in 1502 Leonardo entered the service of Cesare Borgia, the son of Pope Alexander VI, acting as a military architect and engineer and travelling throughout Italy with his patron. Leonardo created a map of Cesare Borgia's stronghold, a town plan of Imola in order to win his patronage. Maps were extremely rare at the time and it would have seemed like a new concept; upon seeing it, Cesare hired Leonardo as his chief military engineer and architect. Later in the year, Leonardo produced another map for his patron, one of Chiana Valley, Tuscany so as to give his patron a better overlay of the land and greater strategic position. He created this map in conjunction with his other project of constructing a dam from the sea to Florence in order to allow a supply of water to sustain the canal during all seasons.

Plan of Imola: 1502

Leonardo returned to Florence where he rejoined the Guild of Saint Luke on October 18, 1503, and spent two years designing and painting a mural of The Battle of Anghiari for the Signoria, with Michelangelo designing its companion piece, The Battle of Cascina. In Florence in 1504, he was part of a committee formed to relocate, against the artist's will, Michelangelo's statue of David.

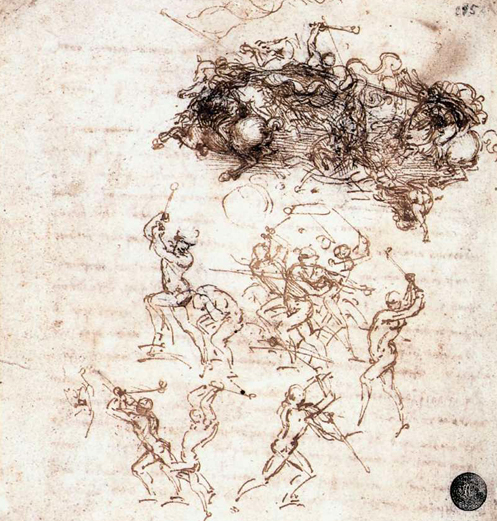

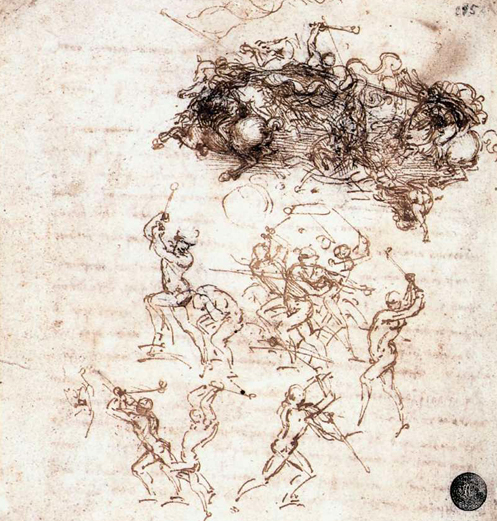

The Battle of Anghiari by Leonardo da Vinci

The Republic of Florence, which came into being in 1494, decided to create an assembly hall for their most important political committee, the "High Council", which was suited to the requirements and pretensions of the new republic. The majority of the construction work on the Sala del Gran Consiglio in the Florentine Palazzo Vecchio had been completed shortly before 1500. The pictorial program was to include two large wall paintings intended to express the self-confidence of the new republic. It was planned that two important victories from recent Florentine history should be depicted: the Battle of Anghiari and the Battle of Cascina. The choice of artist had to measure up to the importance of the commission, and the decision was made in favor of two of the most highly esteemed Florentine artists of the age, Leonardo da Vinci and the young Michelangelo.

Neither of the two artists completed his works and we only know of their projects indirectly by their being mentioned in documents, or in the form of copies or sketches that have been associated with the project.

Quoted From: The Web Gallery of Art

The Battle of Anghiari (Detail): 1503-05

This is the best copy of the Battle of Anghiari executed by an unknown artist in mid-16th century. At the sides it was made up by Rubens.

The Battle of Anghiari (Detail 2): 1503-05

The picture shows a copy by an unknown artist, the original did not survive.

The Battle of Anghiari (Copy of a Detail): 1503-05

Both Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo were commissioned to paint battle scenes in the Salone dei Cinquecento of the Palazzo Signoria in Florence. Leonardo gained a reputation for not finishing his projects, together with the Adoration and the mighty equestrian statue for the Duke of Milan, the fresco of the Battle of Anghiari is another example of a project not brought to completion. He likely did little more than sketch the design on the wall of the room. In preparation, however, he produced an elaborate cartoon, now lost, of which numerous copies were made by other artists.

Quoted From: The Web Gallery of Art

Battle of Anghiari (Tavola Doria): 1503-05

The panel is named after the collector Doria, who owned it until 1651. It shows the main scene of the design for the wall painting of the Battle of Anghiari for the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence. The familiar sources from the 16th century speak of a panel showing a group of horses; it could be this very painting. The reproduction shows a copy by an unknown master.

Quoted From: The Web Gallery of Art

Peter Paul Ruben's copy of the lost Battle of Anghiari

In 1506 Leonardo returned to Milan. Many of his most prominent pupils or followers in painting either knew or worked with him in Milan, including Bernardino Luini, Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio and Marco d'Oggione. However, he did not stay in Milan for long because his father had died in 1504, and in 1507 he was back in Florence trying to sort out problems with his brothers over his father's estate. By 1508 Leonardo was back in Milan, living in his own house in Porta Orientale in the parish of Santa Babila.

Later Life, 1513-19

From September 1513 to 1516, Leonardo spent much of his time living in the Belvedere in the Vatican in Rome, where Raphael and Michelangelo were both active at the time. In October 1515, Francis I of France recaptured Milan. On December 19, Leonardo was present at the meeting of Francis I and Pope Leo X, which took place in Bologna. Leonardo was commissioned to make for Francis a mechanical lion which could walk forward, then open its chest to reveal a cluster of lilies. In 1516, he entered François' service, being given the use of the manor house Clos Lucé near the king's residence at the royal Château d'Amboise. It was here that he spent the last three years of his life, accompanied by his friend and apprentice, Count Francesco Melzi, and supported by a pension totalling 10,000 scudi.

Clos Lucé in France, where Leonardo died in 1519

Leonardo died at Clos Lucé, on May 2, 1519. Francis I had become a close friend. Vasari records that the king held Leonardo's head in his arms as he died, although this story, beloved by the French and portrayed in romantic paintings by Ingres, Ménageot and other French artists, as well as by Angelica Kauffmann, may be legend rather than fact. Vasari states that in his last days, Leonardo sent for a priest to make his confession and to receive the Holy Sacrament. In accordance with his will, sixty beggars followed his casket. Melzi was the principal heir and executor, receiving as well as money, Leonardo's paintings, tools, library and personal effects. Leonardo also remembered his other long-time pupil and companion, Salai and his servant Battista di Vilussis, who each received half of Leonardo's vineyards, his brothers who received land, and his serving woman who received a black cloak "of good stuff" with a fur edge. Leonardo da Vinci was buried in the Chapel of Saint-Hubert in Château d'Amboise, in France.

Some 20 years after Leonardo's death, Francis was reported by the goldsmith and sculptor Benevenuto Cellini as saying: "There had never been another man born in the world who knew as much as Leonardo, not so much about painting, sculpture and architecture, as that he was a very great philosopher."

Florence: Leonardo's Artistic and Social Background

Florence, at the time of Leonardo's youth, was the center of Christian Humanist thought and culture. Leonardo commenced his apprenticeship with Verrocchio in 1466, the year that Verrocchio's master, the great sculptor Donatello, died. The painter Uccello, whose early experiments with perspective were to influence the development of landscape painting, was a very old man. The painters Piero della Francesca and Fra Filippo Lippi, sculptor Luca della Robbia, and architect and writer Leon Battista Alberti were in their sixties. The successful artists of the next generation were Leonardo's teacher Verrocchio, Antonio Pollaiuolo and the portrait sculptor, Mino da Fiesole whose lifelike busts give the most reliable likenesses of Lorenzo Medici's father Piero and uncle Giovanni.

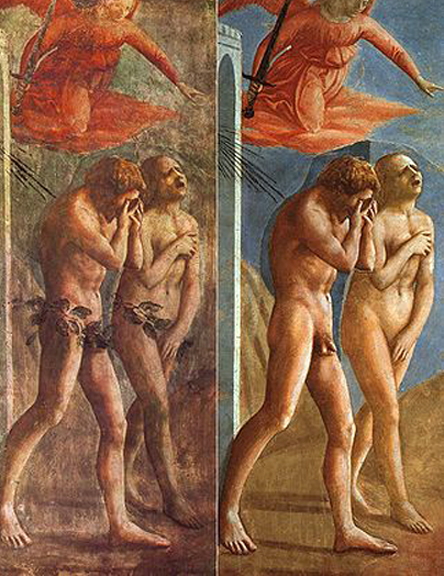

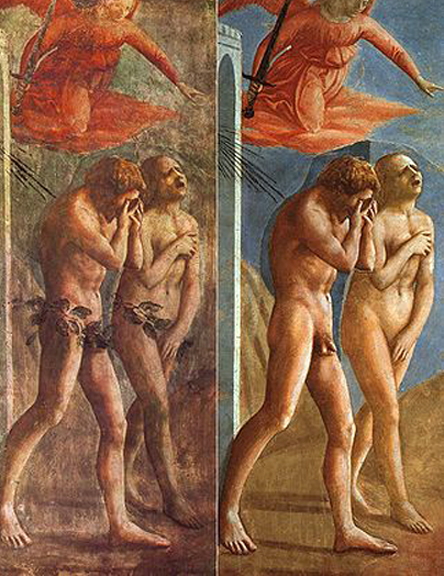

Leonardo's youth was spent in a Florence that was ornamented by the works of these artists and by Donatello's contemporaries, Masaccio, whose figurative frescoes were imbued with realism and emotion and Ghiberti whose Gates of Paradise, gleaming with gold leaf, displayed the art of combining complex figure compositions with detailed architectural backgrounds. Piero della Francesca had made a detailed study of perspective, and was the first painter to make a scientific study of light. These studies and Alberti's Treatise were to have a profound effect on younger artists and in particular on Leonardo's own observations and artworks.

The Gates of Paradise in Florence by Lorenzo Ghiberti

Massaccio's "The Expulsion from the Garden of Eden" depicting the naked and distraught Adam and Eve created a powerfully expressive image of the human form, cast into three dimensions by the use of light and shade which was to be developed in the works of Leonardo in a way that was to be influential in the course of painting. The humanist influence of Donatello's "David" can be seen in Leonardo's late paintings, particularly John the Baptist.

The Expulsion of Adam and Eve from Eden (Restoration)

A prevalent tradition in Florence was the small altarpiece of The Virgin and Child. Many of these were created in tempera or glazed terracotta by the workshops of Filippo Lippi, Verrocchio and the prolific della Robbia family. Leonardo's early Madonnas such as The Madonna with a Carnation and The Benois Madonna followed this tradition while showing idiosyncratic departures, particularly in the case of the Benois Madonna in which the Virgin is set at an oblique angle to the picture space with the Christ Child at the opposite angle. This compositional theme was to emerge in Leonardo's later paintings such as The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne.

The Madonna of the Carnation: ca 1478-80

A work that would seem to evoke the sketches of a young Leonardo freed from Verrocchio's tutelage, though nevertheless still affected by a passion and taste for the soft textures and dazzle of solid material (as practiced in the workshop of the Florentine artist), is the Madonna sometimes referred to as the Madonna of the Carnation or "Madonna of the flowers".

This painting is a free variant of the Benois Madonna in the Hermitage, being more complex in its composition and spatial arrangement, though perhaps somewhat high-flown and less spontaneous. How it arrived at the Alte Pinakothek in Munich, after its acquisition by a private German collector, is unknown to us. What is certain is that after a comprehensible, temporary attribution to Verrocchio or his shop, art critics subsequently almost universally assigned the painting to Leonardo, a judgment backed up by the most recent research. In fact, the richness of the drapery, the vastness of the mountain scenery with purple and gold hues tingeing the foothills of peaks that fade into the sky, the vitality of the cut flowers in the crystal vase and the softness of the Child's flesh that foreshadows the tender putti of the Virgin of the Rocks, are elements that show a distancing from the more distinctive Verrocchiesque style and instead assume those formal and chromatic characteristics that would be the mature Leonardo's very own. Moreover, we should not overlook the striking similarities - in facial features and other details - with the Benois Madonna already mentioned (the gem fastening the Virgin's gown over her breast) and with the Uffizi Annunciation, works that in their figurative and expressive invention quite clearly reveal the stamp of Leonardo.

Quoted From: The Web Gallery of Art

Madonna with a Flower

(Madonna Benois): ca 1478

Mary and her child are naturally engrossed in their game, and their gazes make them appear lifelike to a degree that can be found in no contemporary Italian painting of the Madonna. Leonardo achieved this quality by means of nature studies. In 1478, he noted that he was working on two Madonnas. The Benois Madonna can be dated to that period. The painting has in its present condition been overpainted in some places and has lost some of the paint layer.

The painting was also called the Madonna Benois because of the family who owned it. This canvas demonstrates the newly developed method of chiaroscuro - a lighting/shading technique that made the figures appear three dimensional. It entered the Hermitage in 1914.

Quoted From: The Web Gallery of Art

Leonardo was a contemporary of Botticelli, Domenico Ghirlandaio and Perugino, who were all slightly older than he was. He would have met them at the workshop of Verrocchio, with whom they had associations, and at the Academy of the Medici. Botticelli was a particular favorite of the Medici family, and thus his success as a painter was assured. Ghirlandaio and Perugino were both prolific and ran large workshops. They competently delivered commissions to well-satisfied patrons who appreciated Ghirlandaio's ability to portray the wealthy citizens of Florence within large religious frescoes, and Perugino's ability to deliver a multitude of saints and angels of unfailing sweetness and innocence.

These three were among those commissioned to paint the walls of the Sistine Chapel, the work commencing with Perugino's employment in 1479. Leonardo was not part of this prestigious commission. His first significant commission, The Adoration of the Magi for the Monks of Scopeto, was never completed.

In 1476, during the time of Leonardo's association with Verrocchio's workshop, the Portinari Altarpiece by Hugo van der Goes arrived in Florence, bringing new painterly techniques from Northern Europe which were to profoundly affect Leonardo, Ghirlandaio, Perugino and others. In 1479, the Sicilian painter Antonello da Messina, who worked exclusively in oils, traveled north on his way to Venice, where the leading painter Giovanni Bellini adopted the technique of oil painting, quickly making it the preferred method in Venice. Leonardo was also later to visit Venice.

Portinari Altarpiece by Hugo van de Goes

Like the two contemporary architects Bramante and Antonio da Sangallo the Elder Leonardo experimented with designs for centrally planned churches, a number of which appear in his journals, as both plans and views, although none was ever realized.

Leonardo's political contemporaries wereLorenzo Medici (il Magnifico), who was three years older, and his younger brother Giuliano who was slain in the Pazzi Conspiracy in 1478. Ludovico il Moro who ruled Milan between 1479-1499 and to whom Leonardo was sent as ambassador from the Medici court, was also of Leonardo's age.

With Alberti, Leonardo visited the home of the Medici and through them came to know the older Humanist philosophers of whom Marsiglio Ficino, proponent of Neo Platonism; Cristoforo Landino, writer of commentaries on Classical writings, and John Argyropoulos, teacher of Greek and translator of Aristotle were the foremost. Also associated with the Academy of the Medici was Leonardo's contemporary, the brilliant young poet and philosopher Pico della Mirandola. Leonardo later wrote in the margin of a journal "The Medici made me and the Medici destroyed me." While it was through the action of Lorenzo that Leonardo received his employment at the court of Milan, it is not known exactly what Leonardo meant by this cryptic comment.

Although usually named together as the three giants of the High Renaissance, Leonardo, Michelangelo and Raphael were not of the same generation. Leonardo was twenty-three when Michelangelo was born and thirty-one when Raphael was born. Raphael only lived until the age of 37 and died in 1520, the year after Leonardo, but Michelangelo went on creating for another 45 years.

Personal Life

Within Leonardo's lifetime, his extraordinary powers of invention, his "outstanding physical beauty", "infinite grace", "great strength and generosity", "regal spirit and tremendous breadth of mind" as described by Vasari, as well as all other aspects of his life, attracted the curiosity of others. One such aspect is his respect for life evidenced by his vegetarianism and his habit, according to Vasari, of purchasing caged birds and releasing them.

Leonardo had many friends who are now renowned either in their fields or for their historical significance. They included the mathematician Luca Pacioli, with whom he collaborated on a book in the 1490's, as well as Franchinus Gaffurius and Isabella d'Este. Leonardo appears to have had no close relationships with women except for his friendship with the two Este sisters, Beatrice and Isabella. He drew a portrait of Isabella while on a journey which took him through Mantua, and which appears to have been used to create a painted portrait, now lost.

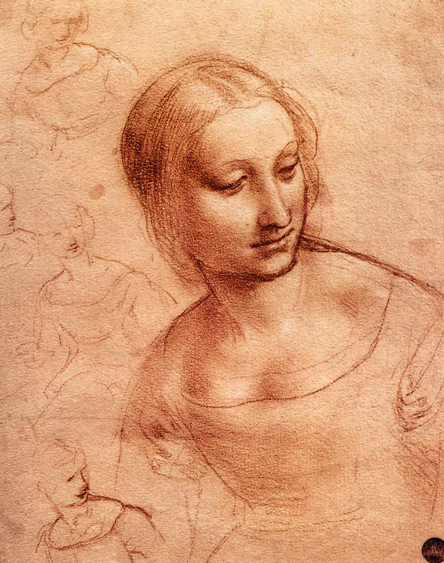

Isabella d'Este: 1500

Beyond friendship, Leonardo kept his private life secret. His sexuality has been the subject of satire, analysis, and speculation. This trend began in the mid-16th century and was revived in the 19th and 20th centuries, most notably by Sigmund Freud. Leonardo's most intimate relationships were perhaps with his pupils Salai and Melzi. Melzi, writing to inform Leonardo's brothers of his death, described Leonardo's feelings for his pupils as both loving and passionate. It has been claimed since the 16th century that these relationships were of a sexual or erotic nature. Court records of 1476, when he was aged twenty-four, show that Leonardo and three other young men were charged with sodomy in an incident involving a well-known male prostitute. The charges were dismissed for lack of evidence, and there is speculation that since one of the accused, Lionardo de Tornabuoni, was related to Lorenzo de' Medici, the family exerted its influence to secure the dismissal. Since that date much has been written about his presumed homosexuality and its role in his art, particularly in the androgyny and eroticism manifested in John the Baptist and Bacchus and more explicitly in a number of erotic drawings.

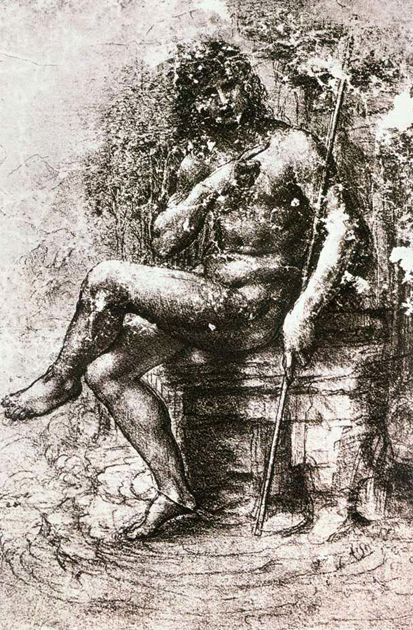

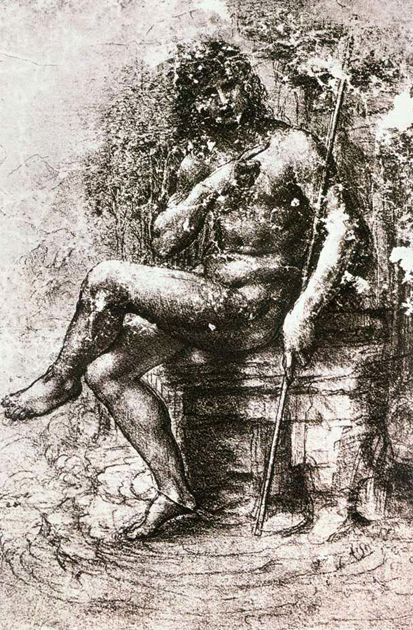

Saint John in the Wilderness (Bacchus): 1510-15

Assistants and Pupils

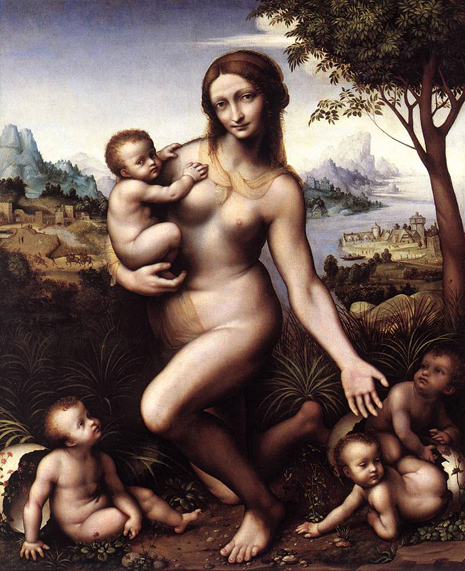

Gian Giacomo Caprotti da Oreno, nicknamed Salai or Il Salaino ("The Little Unclean One" i.e., the devil), entered Leonardo's household in 1490. After only a year, Leonardo made a list of his misdemeanors, calling him "a thief, a liar, stubborn, and a glutton", after he had made off with money and valuables on at least five occasions and spent a fortune on clothes. Nevertheless, Leonardo treated him with great indulgence, and he remained in Leonardo's household for the next thirty years. Salai executed a number of paintings under the name of Andrea Salai, but although Vasari claims that Leonardo "taught him a great deal about painting", his work is generally considered to be of less artistic merit than others among Leonardo's pupils, such as Marco d'Oggione and Boltraffio. In 1515, he painted a nude version of the Mona Lisa, known as Monna Vanna. Salai owned the Mona Lisa at the time of his death in 1525, and in his will it was assessed at 505 lire, an exceptionally high valuation for a small panel portrait.

In 1506, Leonardo took on another pupil, Count Francesco Melzi, the son of a Lombard aristocrat, who is considered to have been his favorite student. He travelled to France with Leonardo and remained with him until Leonardo's death. Melzi inherited the artistic and scientific works, manuscripts, and collections of Leonardo and administered the estate.

Gian Giacomo Caprotti (Salai)

Monna Vanna

Painting

Despite the recent awareness and admiration of Leonardo as a scientist and inventor, for the better part of four hundred years his fame rested on his achievements as a painter and on a handful of works, either authenticated or attributed to him that have been regarded as among the masterpieces.

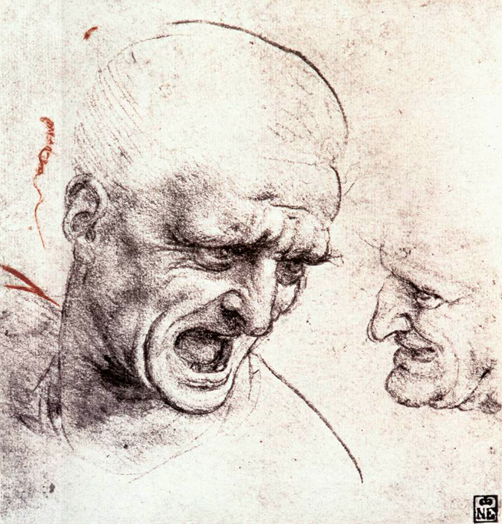

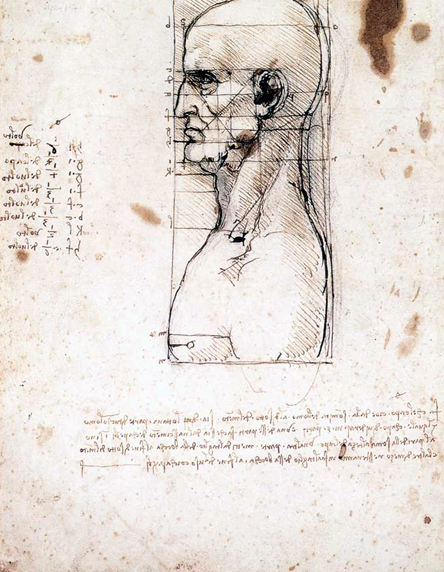

These paintings are famous for a variety of qualities which have been much imitated by students and discussed at great length by connoisseurs and critics. Among the qualities that make Leonardo's work unique are the innovative techniques that he used in laying on the paint, his detailed knowledge of anatomy, light, botany and geology, his interest in physiognomy and the way in which humans register emotion in expression and gesture, his innovative use of the human form in figurative composition, and his use of the subtle gradation of tone. All these qualities come together in his most famous painted works, the Mona Lisa, the Last Supper and the Virgin of the Rocks.

Early Works

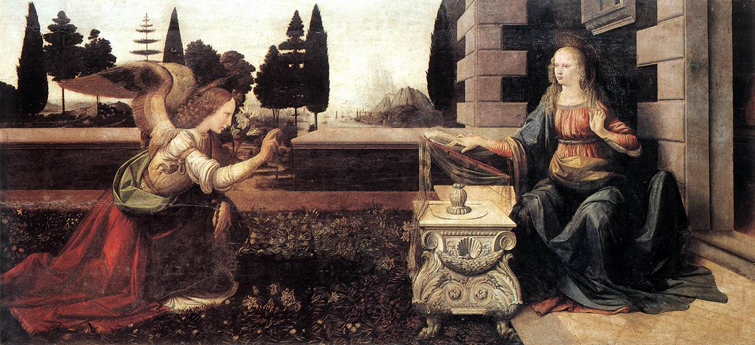

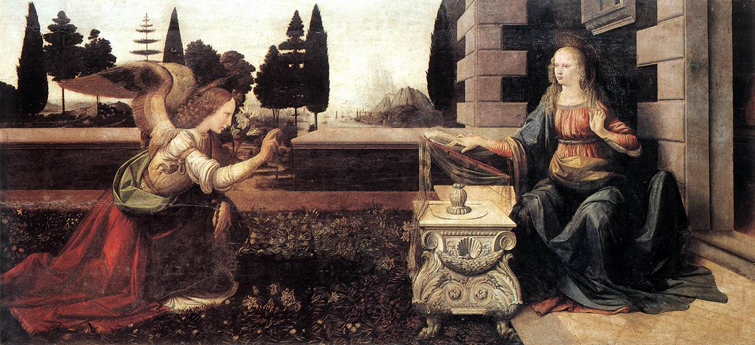

Leonardo's early works begin with the Baptism of Christ (see above) painted in conjunction with Verrocchio. Two other paintings appear to date from his time at the workshop, both of which are Annunciations. One is small, (23 inches) long and (5.5 inches) high. It is a "predella" to go at the base of a larger composition, in this case a painting by Lorenzo di Credi from which it has become separated. The other is a much larger work, (85 inches) long. In both these Annunciations, Leonardo used a formal arrangement, such as in Fra Angelico's two well-known pictures of the same subject, of the Virgin Mary sitting or kneeling to the right of the picture, approached from the left by an angel in profile with rich flowing garment, raised wings and bearing a lily. Although previously attributed to Ghirlandaio, the larger work is now generally attributed to Leonardo.

In the smaller picture Mary averts her eyes and folds her hands in a gesture that symbolized submission to God's will. In the larger picture, however, Mary is not submissive. The girl, interrupted in her reading by this unexpected messenger, puts a finger in her bible to mark the place and raises her hand in a formal gesture of greeting or surprise. This calm young woman appears to accept her role as the Mother of God not with resignation but with confidence. In this painting the young Leonardo presents the humanist face of the Virgin Mary, recognizing humanity's role in God's incarnation.

Annunciation: 1472-75

The archangel Gabriel is kneeling as a dignified profile figure and raising his right hand in greeting to Mary, indicating her divine pregnancy. The Virgin has stopped reading and reacts to the Annunciation with an expression of deep respect and by gesturing with her left hand. There is a conspicuous perspectival mistake: her right arm had to be painted too long proportionally, so that, despite her seated position, it would still be able to depict the impressive position other hand over the prie-dieu. Leonardo depicted Mary in a three-quarter profile in front of the corner of a room. All three spatial coordinates - height, width and depth - converge on this point, thus creating a sense of depth in the picture as well as enhancing the importance of Mary. Her head clearly contrasts with the dark wall and her body is emphatically framed by the cornerstones whose parallel lines are converging on her.

The work came to the Uffizi in 1867 from the monastery of San Bartolomeo of Monteoliveto, near Florence. It was ascribed to Domenico Ghirlandaio until 1869, when some critics recognized it as a youthful work by Leonardo, executed around 1472-1475, when he was still an apprentice in the workshop of his master, Andrea del Verrocchio. The sacred scene is set in the garden of a Florentine palace, with a landscape on the background which is already peculiarly Leonardesque, for the magic and unreal atmosphere created by mountains, water and sky. Leonardo's personality is pointed out also in the beautiful drapery of the Virgin and the Angel, while the marble table in front of her probably quotes the tomb of Piero and Giovanni dei Medici in the church of San Lorenzo sculpted by Verrocchio in this period.

Quoted From: The Web Gallery of Art

Annunciation (Detail 1): 1472-75

The detail shows the angel annunciating.

Annunciation (Detail 2): 1472-75

The detail shows the Virgin annunciate.

Annunciation (Detail 3): 1472-75

The detail shows the head of the Virgin.

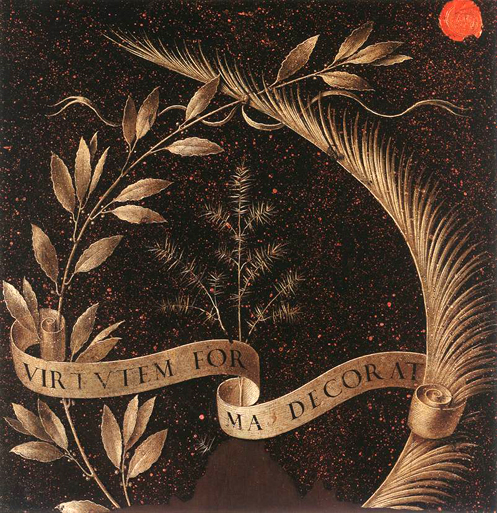

Portrait of Ginevra de Benci: 1474-78

One of Leonardo's earlier works completed while he was apprenticed to Andrea Verrocchio in his Florentine workshop. Here, Leonardo learned a variety of skills that he would master later on in his career. Although this painting is rather traditional, it includes details such as Ginevra's curling hair that only Leonardo could achieve.

Although a portrait of Ginevra de' Benci by Leonardo is mentioned by three sixteenth-century writers, the attribution of the Washington painting to that artist has been the cause of much debate. It is now accepted by virtually all Leonardo scholars. The date of the portrait, generally given as c. 1474, and its commission, however, are still discussed. The sitter, born into a wealthy Florentine family, was married to Luigi Niccolini in 1474 at the age of sixteen. It was a customary practice to have a likeness painted on just such an occasion. Recently, however, the humanist Bernardo Bembo has been identified as a possible patron. He was the Venetian Ambassador to Florence from 1474-76 and again in 1478-80, dates that have been suggested for the portrait. Bembo and Ginevra, both married to others, were known to have had a platonic affair, an accepted convention at the time.

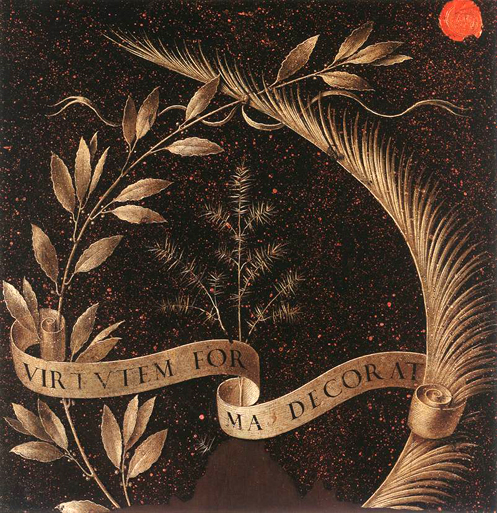

The heraldic motif on the painted porphyry reverse side of the portrait, with the motto "Beauty adorns Virtue," praises her, and juniper plants symbolize chastity, considered an appropriate choice for a marriage portrait. The juniper bush, ginepro in Italian, is also a pun on her name.

Leonardo has painted a sensitive and finely modeled image of Ginevra. The undulating curls of her hair are set against her pale flesh, the surface of the paint smoothed by the artist's own hands. Leonardo's portrait was cut down at the bottom sometime in the past by as much as one-third. Presumably the lower section would have shown her hands, possibly folded or crossed, resting in her lap.

Reverse Side of the Portrait of Ginevra de Benci: 1474-78

The inscription on the band connecting the juniper, laurel and palm branches: VIRTUTEM FORMA DECORAT (Beauty adorns Virtue).

Annunciation: 1478-82

This Annunciation predella was originally part of the altar of the Madonna di Piazza in the cathedral of Pistoia commissioned from Verrocchio and produced between 1475 and 1485 with the assistance of Lorenzo di Credi in Verrocchio's workshop. Leonardo's participation in the work on the altar is the subject of debate.

Quoted From: The Web Gallery of Art

Annunciation (Detail 1): 1478-82

The detail shows the angel annunciating.

Annunciation (Detail 2): 1478-82

The detail shows the Virgin annunciated.

Paintings in the 1480's by Lonardo da Vinci

Leonardo lived in Milan from 1482 to until 1499 working mainly at the court of Duke Ludovico Sforza (Il Moro). His paintings in the 1480s included portraits, notably the marvelous picture of Duke Ludovico's mistress Cecilia Gallerani known as the Lady with an Ermine and an altarpiece of the Virgin of the Rocks, which exists in two problematically related versions, the earlier (Louvre, Paris) possibly painted when Leonardo still was in Florence, the later (National Gallery, London) still being worked on in 1508.

Quoted From: The Web Gallery of Art

Paintings of the 1480's

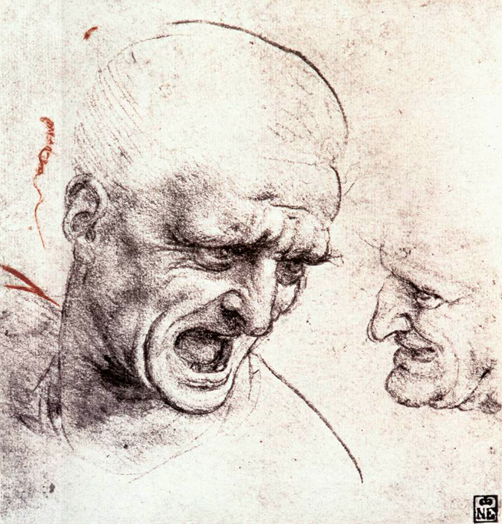

In the 1480's Leonardo received two very important commissions and commenced another work which was also of ground-breaking importance in terms of composition. Two of the three were never finished, and the third took so long that it was subject to lengthy negotiations over completion and payment. One of these paintings is that of Saint Jerome in the Wilderness. Bortolon associates this picture with a difficult period of Leonardo's life, as evidenced in his diary: "I thought I was learning to live; I was only learning to die."

Although the painting is barely begun, the composition can be seen and it is very unusual. Jerome, as a penitent, occupies the middle of the picture, set on a slight diagonal and viewed somewhat from above. His kneeling form takes on a trapezoid shape, with one arm stretched to the outer edge of the painting and his gaze looking in the opposite direction. J. Wasserman points out the link between this painting and Leonardo's anatomical studies. Across the foreground sprawls his symbol, a great lion whose body and tail make a double spiral across the base of the picture space. The other remarkable feature is the sketchy landscape of craggy rocks against which the figure is silhouetted.

Saint Jerome: ca 1480

In about 370, Saint Jerome, later a Father of the Church is said to have withdrawn to live as a hermit in the desert of Chalcis near Antioch, in order to produce a translation of the Bible and live as an ascetic. Leonardo depicts the Father of the Church as a penitent, not a scholar. Saint Jerome is kneeling in a humble posture that arouses our sympathy, in front of the sketched cross of Christ on the right, and before him lies the lion, his attribute. In his right hand he is holding a stone with which he is striking his breast. The head section of the unfinished panel was sawn out in the 18th century and not replaced and restored until the 19th century.

Quoted From: The Web Gallery of Art

The daring display of figure composition, the landscape elements and personal drama also appear in the great unfinished masterpiece, the Adoration of the Magi, a commission from the Monks of San Donato a Scopeto (see above). Leonardo did numerous drawings and preparatory studies, including a detailed one in linear perspective of the ruined classical architecture which makes part of the backdrop to the scene. But in 1482 Leonardo went off to Milan at the behest of Lorenzo de' Medici in order to win favor with Ludovico il Moro, and the painting was abandoned.

The third important work of this period is The Virgin of the Rocks which was commissioned in Milan for the Confraternity of the Immaculate Conception (see above). The painting, to be done with the assistance of the de Predis brothers, was to fill a large complex altarpiece, already constructed. Leonardo chose to paint an apocryphal moment of the infancy of Christ when the infant John the Baptist, in protection of an angel, met the Holy Family on the road to Egypt. In this scene, as painted by Leonardo, John recognizes and worships Jesus as the Christ. The painting demonstrates an eerie beauty as the graceful figures kneel in adoration around the infant Christ in a wild landscape of tumbling rock and whirling water. While the painting is quite large, it is not nearly as complex as the painting ordered by the monks of Saint Donato, having only four figures rather than about fifty and a rocky landscape rather than architectural details. The painting was eventually finished; in fact, two versions of the painting were finished, one which remained at the chapel of the Confraternity and the other which Leonardo carried away to France. But the Brothers did not get their painting, or the de Predis their payment, until the next century.

Portrait of Cecilia Gallerani, Lady with an Ermine: 1483-90

Cecilia Gallerani is holding the heraldic animal of Ludovico il Moro in her arms. She was his favorite and gave birth to his child in the same year as he married Beatrice d'Este. The charming and vivid impression Cecilia makes gained Leonardo the reputation of being a talented portrait painter. The movement of this beautiful girl turning slowly from the shadow into the light is mirrored by the small animal she is holding.

The inscription in the upper left corner - La Feroniere Leonard d'Awinci - is a mistaken addition at the end of the 18th century.

Quoted From: The Web Gallery of Art

Paintings in the 1490's by Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo's main artistic undertakings in Milan were a project for a huge equestrian statue to Ludovico Sforza's father, and the wall-painting of the Last Supper in the refectory of Santa Maria delle Grazie. The fresco method of mural painting was not flexible or subtle enough for the slow-working Leonardo, so he adopted an experimental technique that quickly caused the picture to deteriorate disastrously. It has been many times restored, but although it is only a shadow of Leonardo's original creation it still retains some of the immense authority that has made it the most revered painting in the world.

Quoted From: The Web Gallery of Art

Paintings of the 1490's

Leonardo's most famous painting of the 1490's is The Last Supper, painted for the refectory of the Convent of Santa Maria della Grazie in Milan see above. The painting represents the last meal shared by Jesus with his disciples before his capture and death. It shows specifically the moment when Jesus has just said "one of you will betray me". Leonardo tells the story of the consternation that this statement caused to the twelve followers of Jesus.

The novelist Matteo Bandello observed Leonardo at work and wrote that some days he would paint from dawn till dusk without stopping to eat and then not paint for three or four days at a time. This was beyond the comprehension of the prior of the convent, who hounded him until Leonardo asked Ludovico to intervene. Vasari describes how Leonardo, troubled over his ability to adequately depict the faces of Christ and the traitor Judas, told the Duke that he might be obliged to use the prior as his model.

When finished, the painting was acclaimed as a masterpiece of design and characterization, but it deteriorated rapidly, so that within a hundred years it was described by one viewer as "completely ruined". Leonardo, instead of using the reliable technique of fresco, had used tempera over a ground that was mainly gesso, resulting in a surface which was subject to mold and to flaking. Despite this, the painting has remained one of the most reproduced works of art, countless copies being made in every medium from carpets to cameos.

Other Works of the 1490's

Portrait of a Musician: 1490

It was not until 1904 that the hand and sheet of music were discovered underneath over-paintings, and it is these that have given the painting its present title. Since this discovery, efforts have also been made to identify the person depicted. The names of two important court musicians in Milan during that period are known: Franchino Gaffurio (1451-1522) and Josquin des Prés (c. 1450-1521). But there is no clear indication enabling us to identify either of these two in this portrait.

The attribution to Leonardo is debated. If the picture is Leonardo's work, this is the only portrait of a man executed by Leonardo.

Quoted From: The Web Gallery of Art

La belle Ferroniere: ca 1490

This portrait has long been a subject of controversy over its attribution to Leonardo. (The attribution to Bernardino de'Conti or Boltraffio can also be found in the literature.) The refinement with which the woman is gently turning her head and in which the eyes pick up and continue this movement clearly show it to be a work by Leonardo. Coarse over-painting of the hair has had an adverse effect on the painting without, however, being able to conceal its high quality.

It has not so far been possible to establish beyond doubt the identity of the person depicted. It is very probable that this enigmatic and highly intelligent young lady was also a noblewoman at the Milanese court. It is even possible that this is another portrait of Cecilia Gallerani seen in the Cracow painting.

The title of the painting is due to an erroneous cataloguing in the French royal collection, when it was mistaken for a portrait of Belle Ferronière, the mistress of King François I. The misunderstanding was increased by the fact that the band on the forehead of the sitter was also named "ferronière" in the 16th century.

Quoted From: The Web Gallery of Art

Madonna Litta: ca 1490-91

This painting was completed before Leonardo moved back to Florence in 1500 and was at a time when he was experimenting with different mediums. The attribution to Leonardo is debated although preparatory drawings in the Louvre prove that he directly participated in designing the picture.

Quoted From: The Web Gallery of Art

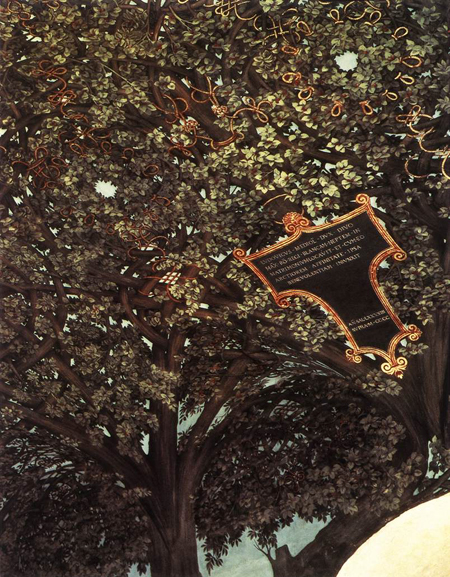

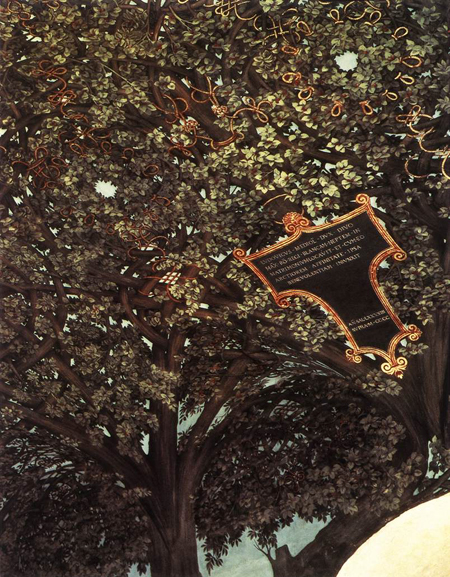

Ceiling Decoration: 1496-98

All that remains of Leonardo's decorations in the Castello Sforzesco in Milan are some fragments in the Sala delle Asse which were, when discovered towards the end of the 19th century, restored in such a way that it is scarcely possible anymore to make out their original appearance. Leonardo's plan was to cover the vaulted ceiling of the Sala with a complicated network of twigs and leaves growing from the tree trunks painted on the side walls, together with the blue of the sky in-between, create the illusion of a jumble of branches beneath an open sky.

Quoted From: The Web Gallery of Art

Ceiling Decoration: 1496-98

All that remains of Leonardo's decorations in the Castello Sforzesco in Milan are some fragments in the Sala delle Asse which were, when discovered towards the end of the 19th century, restored in such a way that it is scarcely possible anymore to make out their original appearance.

Quoted From: The Web Gallery of Art

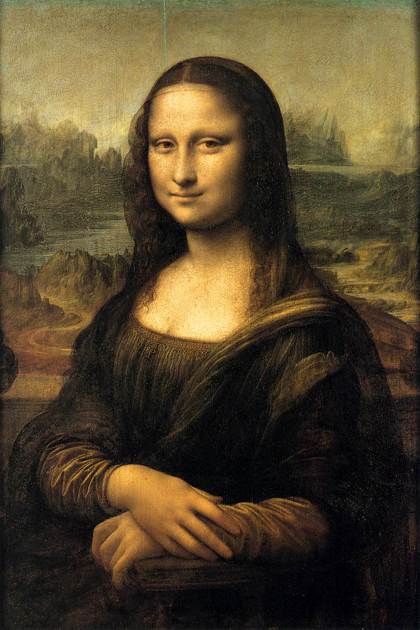

Paintings of the 1500's

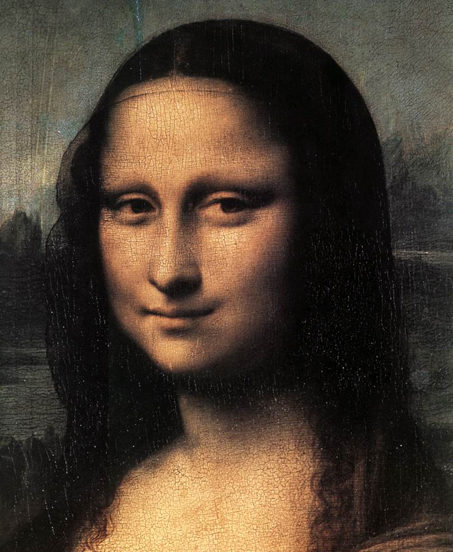

Among the works created by Leonardo in the 16th century is the small portrait known as the Mona Lisa or "la Gioconda", the laughing one. In the present era it is arguably the most famous painting in the world. Its fame rests, in particular, on the elusive smile on the woman's face, its mysterious quality brought about perhaps by the fact that the artist has subtly shadowed the corners of the mouth and eyes so that the exact nature of the smile cannot be determined. The shadowy quality for which the work is renowned came to be called "sfumato" or Leonardo's smoke. Vasari, who is generally thought to have known the painting only by repute, said that "the smile was so pleasing that it seemed divine rather than human; and those who saw it were amazed to find that it was as alive as the original".

Other characteristics found in this work are the unadorned dress, in which the eyes and hands have no competition from other details, the dramatic landscape background in which the world seems to be in a state of flux, the subdued coloring and the extremely smooth nature of the painterly technique, employing oils, but laid on much like tempera and blended on the surface so that the brushstrokes are indistinguishable. Vasari expressed the opinion that the manner of painting would make even "the most confident master ... despair and lose heart." The perfect state of preservation and the fact that there is no sign of repair or over-painting is rare in a panel painting of this date.

In the painting Virgin and Child with Saint Anne the composition again picks up the theme of figures in a landscape which Wasserman describes as "breathtakingly beautiful" and harkens back to the Saint Jerome picture with the figure set at an oblique angle. What makes this painting unusual is that there are two obliquely set figures superimposed. Mary is seated on the knee of her mother, Saint Anne. She leans forward to restrain the Christ Child as he plays roughly with a lamb, the sign of his own impending sacrifice. This painting, which was copied many times, influenced Michelangelo, Raphael, and Andrea del Sarto, and through them Pontormo and Correggio. The trends in composition were adopted in particular by the Venetian painters Tintoretto and Veronese.

Late Paintings (1501-20) by Leonardo da Vinci

Between 1500, when he returned for a time to Florence, and 1516, when he left Italy for France, Leonardo's life was unsettled. In 1502-03 and in 1506-13 he was based in Milan, in 1513 he moved to Rome, but the artistic activity of his later years was chiefly centered in Florence in the years 1500-06. From this time dates his portrait of Mona Lisa, his most famous work, which is as well known for its mastery of technical innovations as for the mysteriousness of its legendary smiling subject. In Florence also Leonardo worked out variations on a theme that fascinated him at this time and presented a great challenge to his skill in composing closely knit groups of figures. This was the Virgin and Child with Saint Anne, known today mainly through a painting in the Louvre, Paris and the incomparably beautiful cartoon in the National Gallery, London.

Leonardo did little artistic work in the last decade of his life, the last paintings from his hand generally being accepted are two pictures of Saint John (one later converted into a Bacchus), both in the Louvre.

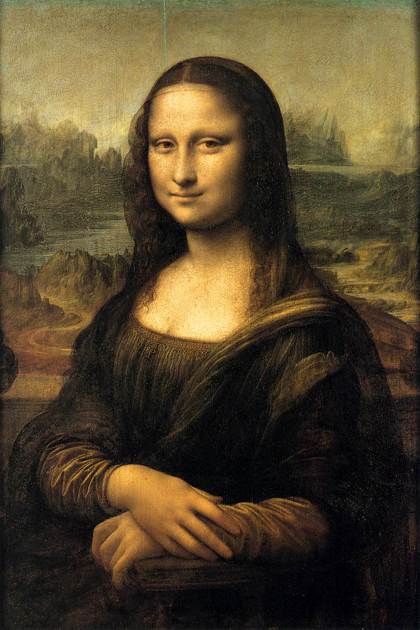

Mona ("Lisa La Gioconda"): ca 1503-05

According to Vasari, this picture is a portrait of Mona or Monna (short for Madonna) Lisa, who was born in Florence in 1479 and in 1495 married the Marquese del Giocondo, a Florentine of some standing - hence the painting's other name, `La Gioconda'. This identification, however, has sometimes been questioned.

Leonardo took the picture with him from Florence to Milan, and later to France. It must have been this portrait which was seen at Cloux, near Amboise, on 10 October 1517 by the Cardinal of Aragon and his secretary, Antonio de Beatis. There is a slight difficulty here, however, because Beatis says that the portrait had been painted at the wish of Giuliano de Medici. Historians have attempted to solve this problem by suggesting that Monna del Giocondo had been Giuliano's mistress.

The painting was probably acquired by François I from Leonardo himself, or after his death from his executor Melzi. It is recorded as being at Fontainebleau by Vasari (1550), Lomazzo (1590), Peiresc, and Cassiano del Pozzo (1625). The latter relates that when the Duke of Buckingham came to the French court to seek the hand of Henrietta of France for Charles I, he made it known that the King was most anxious to own this painting; but the courtiers of Louis XIII prevented him from parting with the picture. It was put on exhibition in the Musée Napoléon in I8o4; before that, in 1800, Bonaparte had it in his room in the Tuileries.

From the beginning it was greatly admired and much copied, and it came to be considered the prototype of the Renaissance portrait. It became even more famous in 1911, when it was stolen from the Salle Carrée on 21 August 1911 by Vicenzo Perrugia, an Italian workman. In 1913 it was found in Florence, exhibited at the Uffizi, then in Rome and Milan, and brought back to Paris on 31 December in the same year.

This figure of a woman, dressed in the Florentine fashion of her day and seated in a visionary, mountainous landscape, is a remarkable instance of Leonardo's sfumato technique of soft, heavily shaded modeling. The Mona Lisa's enigmatic expression, which seems both alluring and aloof, has given the portrait universal fame.

Reams have been written about this small masterpiece by Leonardo, and the gentle woman who is its subject has been adapted in turn as an aesthetic, philosophical and advertising symbol, entering eventually into the irreverent parodies of the Dada and Surrealist artists.

Vasari relates that Leonardo worked on it for four years without being able to finish it; yet the picture gives the impression of being completely realized. The dates suggested for it vary between 1503 and 1513, the most widely accepted being 1503-05.

Taking a living model as his point of departure, Leonardo has expressed in an ideal form the concept of balanced and integrated humanity. The smile stands for the movement of life, and the mystery of the soul. The misty Blue Mountains, towering above the plain and its river, symbolize the universe.

Quoted From: The Web Gallery of Art

Mona Lisa ("La Gioconda") ca 1503-05

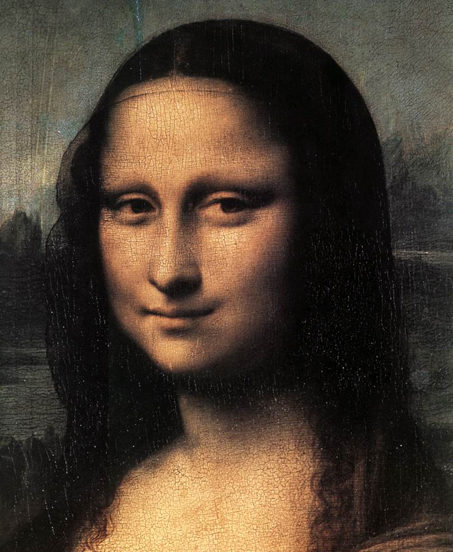

Mona Lisa (Detail): 1503-05

There is a suggestion of a smile both in the Mona Lisa's eyes and on the lips and in the corners other mouth; it appears unfathomable and mysterious and during the course of the centuries has given rise to any number of interpretations. Giorgio Vasari, writing about the arts, provided an amusing explanation: Leonardo wanted to depict the lady in a happy mood and for that reason arranged for musicians and clowns to come to the portrait sittings. This anecdote was ingeniously supported by the name he gave the portrayed woman: "La Gioconda", which means nothing less than "the merry one".

In the essay "On the perfect beauty of a woman'', by the 16th-century writer Firenzuola, we learn that the slight opening of the lips at the corners of the mouth was considered in that period a sign of elegance. Thus Mona Lisa has that slight smile which enters into the gentle, delicate atmosphere pervading the whole painting. To achieve this effect, Leonardo uses the sfumato technique, a gradual dissolving of the forms themselves, continuous interaction between light and shade and an uncertain sense of the time of day.

Quoted From: The Web Gallery of Art

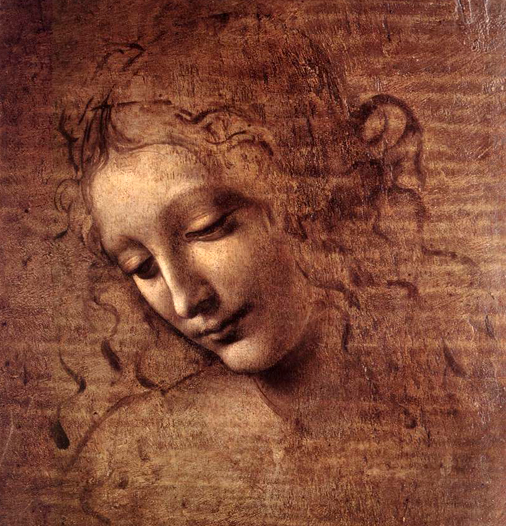

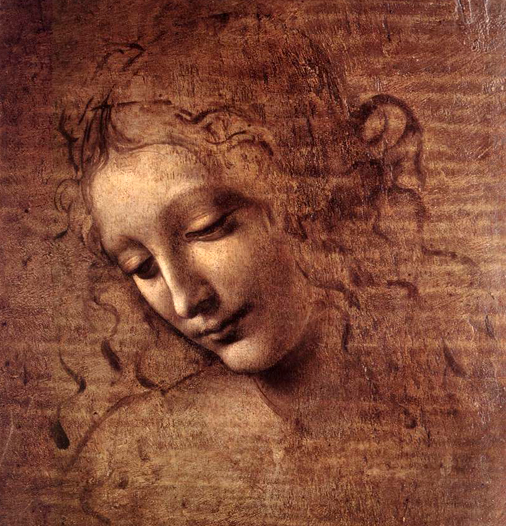

Female Head (La Scapigliata): ca 1508

The face of La Scapigliata is more powerfully executed than that of the standing Leda, though her head is bowed in a similar manner. Given the lack of accessories, it is possible that this face with its thoughtful gaze belongs to a Madonna. The effectively placed powerful brushstrokes in the hair are unusual for Leonardo and possibly a later addition.

The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne: ca 1510

The theme of the Christ Child on the knee of the Virgin, who is herself seated on Saint Anne's lap, is fairly rare, but examples of it can be found from the Middle Ages onwards - the stream of life flowing through three generations. (Anna metterza: Saint Anne with the Virgin and Child.) Leonardo must have chosen this unusual theme for symbolic reasons, which have been variously interpreted. Sigmund Freud made out the shape of a vulture in the Virgin's garment, and suggested a psychoanalytical explanation: since as a child Leonardo dreamt that he had been attacked in his cradle by a vulture.

There is a cartoon in the National Gallery in London by Leonardo of the same subject but differing in important respects from the Louvre painting. We know from a letter that Leonardo made another cartoon, now lost. The painting was commissioned by the Servites in Florence. It is unfinished; perhaps it was abandoned because of the artist's sudden interest in mathematics, and his engagement as engineer in the service of Cesare Borgia. Another hand seems to have finished the lamb which he had perhaps only sketched in; the landscape, Saint Anne, the Virgin and the Child Christ are the work of Leonardo himself. The paint is applied thinly, it is limpid and transparent, so that in some places the underlying sketch is visible. This has become apparent since the very dark varnish was lightened and some over-painting removed in 1953.

Quoted From: The Web Gallery of Art

Saint John the Baptist: 1513-16

Saint John the Baptist is looking at the observer impressively and declaring his identity by means of gestures and gazes. The picture is probably one of the three works which Antonio de Beads saw in Leonardo's studio in Clos-Lucé in 1517. It is the last painting to be produced by Leonardo himself, and was probably already completed in Rome. The attribution is without any doubts since the X-ray investigation that was carried out in 1952.

The Pinacoteca Ambrosiana in Milan owns a further version that depicts St John in a landscape, which is related to the painting of the Madonna and Child with St Anne in the Louvre.

Quoted From: The Web Gallery of Art

Copies and Workshop Works by the Workshop and Followers of Leonardo da Vinci

Madonna with the Yarnwinder: ca 1501

The painting was executed by the workshop, however, Leonardo is thought to have taken part in producing this version of the Madonna with the Yarnwinder, a fact suggested primarily by the rock in the foreground and the boy's face. Martin Kemp even considers this panel to be a version produced immediately after the commission of 1501.

Quoted From: The Web Gallery of Art

Madonna with the Yarnwinder: After 1510

The painting shows a later version of the 1501 Madonna with the Yarnwinder. Because of its background it is dated to 1516, for the landscape suggests that the Mona Lisa was painted beforehand. The high quality suggests that it was produced in Leonardo's workshop. The history of the panel can be traced back to 1756, when it was sold in France.

Quoted From: The Web Gallery of Art

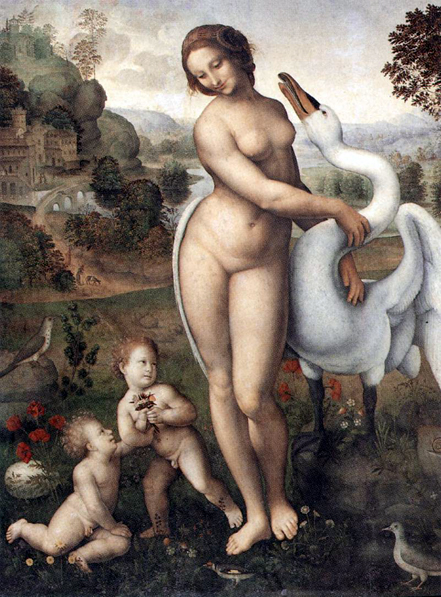

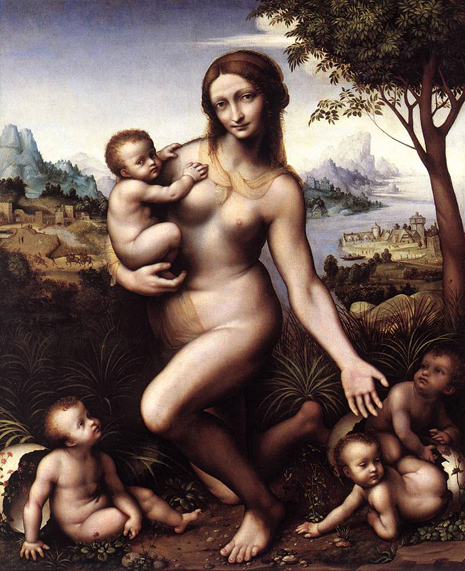

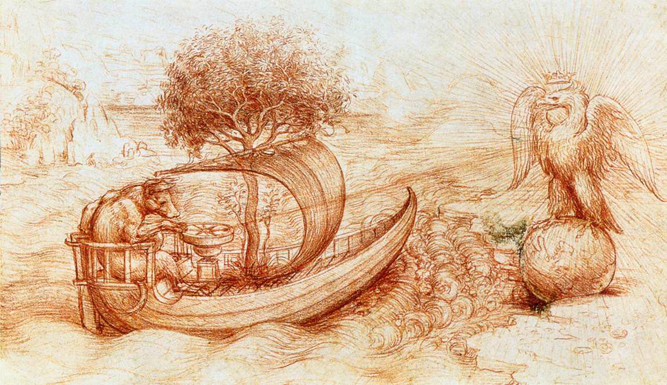

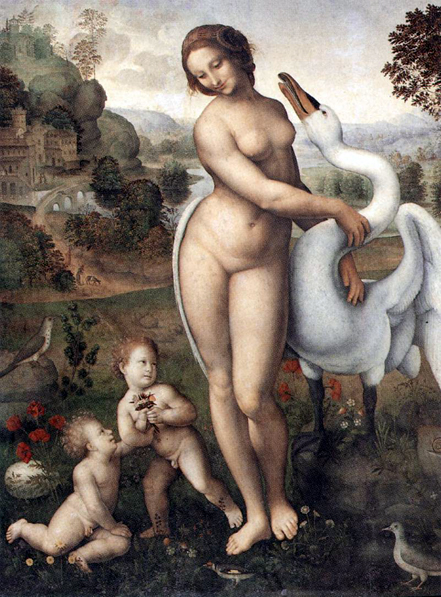

Leda: 1508-15

This painting belongs to the school of Leonardo. Three paintings, in the style of Leonardo, of the standing Leda are known which can be closely connected to a cartoon produced by Leonardo which has not been preserved. It is uncertain when this cartoon was created and when the versions dependent on it were produced.