Disclaimer

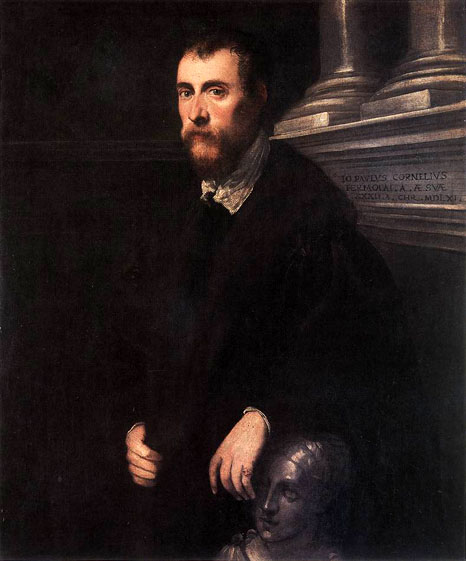

Jacopo Robusti Tintoretto

Mannerist Artist Italian

1518 - 1594

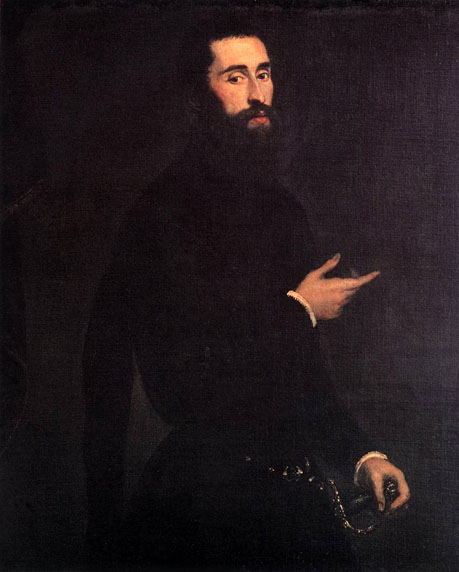

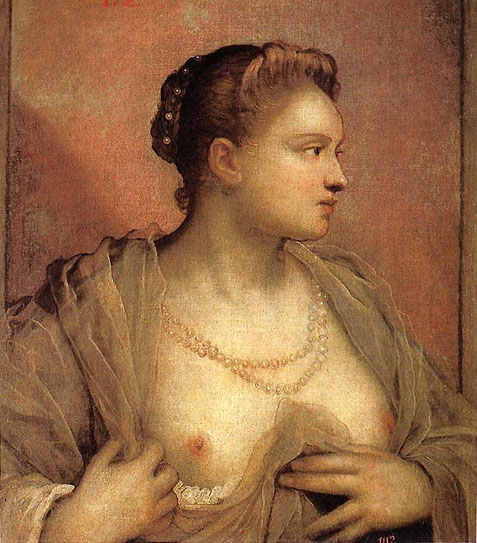

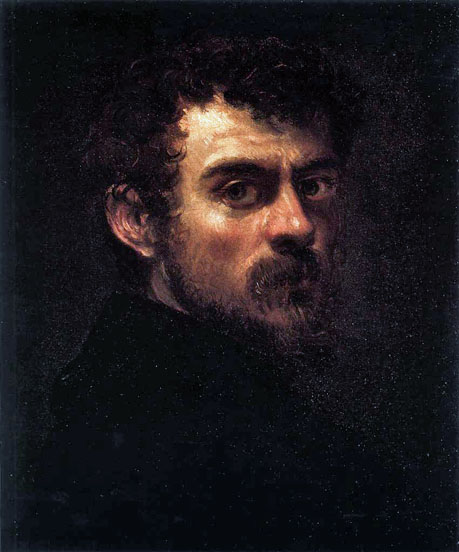

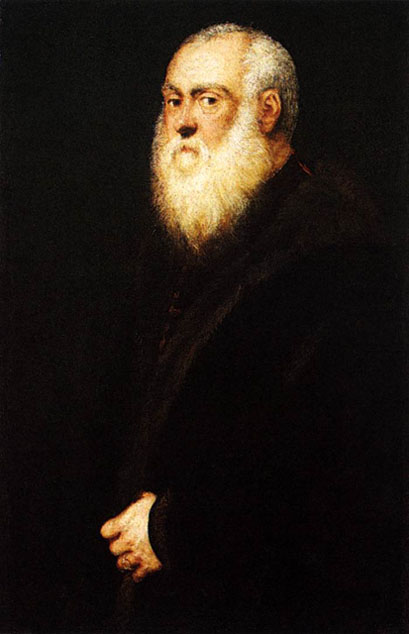

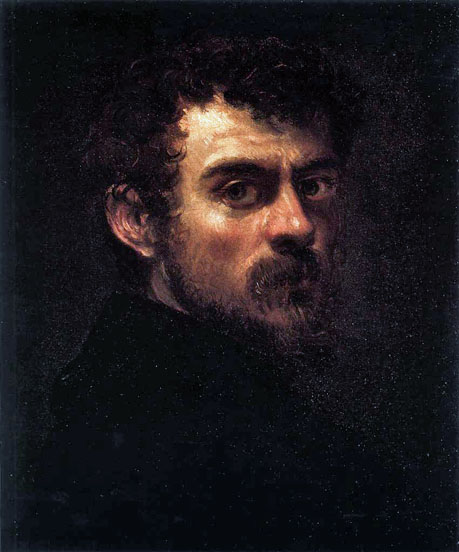

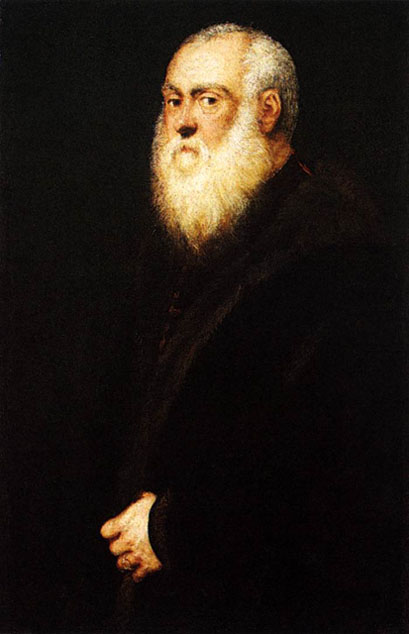

Tintoretto - Self Portrait

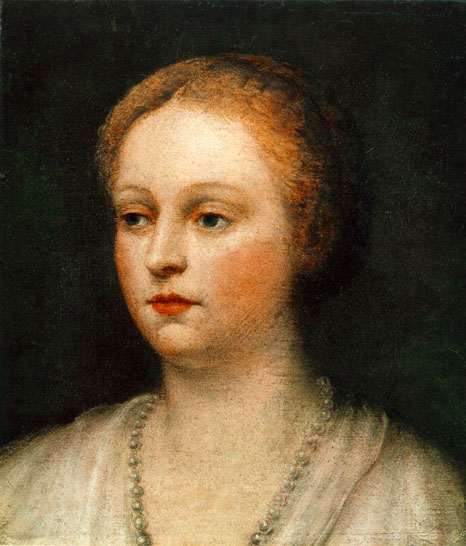

As if responding to a sudden call, the young Tintoretto turns to the viewer, his eyes wide open. Amidst his curly hair, his famous musical ear appears open like a stethoscope, on the alert for commissions, picking up intrigues. His forehead, illuminated by light falling on it from the side, and the inner radiance of his eyes convey inspiration, his sense of artistic mission, and his confidence in the early maturity of his own skill. Tintoretto seems to foresee that he will make his name with religious pictures, for his reddish-brown beard, still rather sparse, curls into two prophetic locks beneath his chin.

Beautiful colors can be bought in the shops on the Riato, but good drawing can only be bought from the casket of the artist's talent with patient study and nights without sleep.

~ Tintoretto

Tintoretto was one of the greatest painters of the Venetian School and probably the last great painter of the Italian Renaissance. In his youth he was also called Jacopo Robusti, as his father had defended the gates of Padua in a rather robust way against the imperial troops. His real name "Comin" has only recently been discovered by Miguel Falomir, the curator of the Museo del Prado, Madrid, and was made public on the occasion of the retrospective of Tintoretto at the Prado in 2007. Comin translates to the spice cumin in the local language.

For his phenomenal energy in painting he was termed Il Furioso, and his dramatic use of perspective space and special lighting effects make him a precursor of baroque art.

He was born in Venice in 1518, as the eldest of 21 children. His father, Giovanni, was a dyer, or tintore; hence the son got the nickname of Tintoretto, little dyer, or dyer's boy, which is anglicized as Tintoret. The family originated from Brescia, in Lombardy, then part of the Republic of Venice. Older studies gave the Tuscan town of Lucca as the origin of the family.

In childhood Jacopo, a born painter, began daubing on the dyer's walls; his father, noticing his bent, took him to the studio of Titian to see how far he could be trained as an artist. We may suppose this to have been towards 1533, when Titian was already fifty-six years of age.

Tintoretto had only been ten days in the studio when Titian sent him home once and for all, the reason being that the great master observed some very spirited drawings, which he learned to be the production of Tintoretto; and it is inferred that he became at once jealous of so promising a scholar. This, however, is mere conjecture; and perhaps it may be fairer to suppose that the drawings exhibited so much independence of manner that Titian judged that young Jacopo, although he might become a painter, would never be properly a pupil.

From this time forward the two always remained upon distant terms, Tintoretto being indeed a professed and ardent admirer of Titian, but never a friend, and Titian and his adherents turning the cold shoulder to him. Active disparagement also was not wanting, but it passed unnoticed by Tintoretto. The latter sought for no further teaching, but studied on his own account with laborious zeal; he lived poorly, collecting casts, bas-reliefs, &c., and practicing by their aid. His noble conception of art and his high personal ambition were evidenced in the inscription which he placed over his studio Il disegno di Michelangelo ed il colorito di Tiziano ("Michelangelo's design and Titian's color").

He studied more especially from models of Michelangelo's Dawn, Noon, Twilight and Night, and became expert in modeling in wax and clay method (practiced likewise by Titian) which afterwards stood him in good stead in working out the arrangement of his pictures. The models were sometimes taken from dead subjects dissected or studied in anatomy schools; some were draped, others nude, and Tintoretto was to suspend them in a wooden or cardboard box, with an aperture for a candle. Now and afterwards he very frequently worked by night as well as by day.

The young painter Andrea Schiavone, four years Tintoretto's junior, was much in his company. Tintoretto helped Schiavone gratis in wall-paintings; and in many subsequent instances he worked also for nothing, and thus succeeded in obtaining commissions. The two earliest mural paintings of Tintoretto - done, like others, for next to no pay - are said to have been Belshazzar's Feast and a Cavalry Fight. These are both long since perished, as are all his frescoes, early or later. The first work of his to attract some considerable notice was a portrait-group of himself and his brother - the latter playing a guitar - with a nocturnal effect; this also is lost. It was followed by some historical subject, which Titian was candid enough to praise.

One of Tintoretto's early pictures still extant is in the church of the Carmine in Venice, the Presentation of Jesus in the Temple; also in Saint Benedetto are the Annunciation and Christ with the Woman of Samaria. For the Scuola della Trinity (the scuole or schools of Venice were more in the nature of hospitals or charitable foundations than of educational institutions) he painted four subjects from Genesis. Two of these, now in the Venetian Academy, are The Temptation of Adam and The Murder of Abel, both noble works of high mastery, which leave us in no doubt that Tintoretto was by this time a consummate painter - one of the few who have attained to the highest eminence in the absence of any formal training.

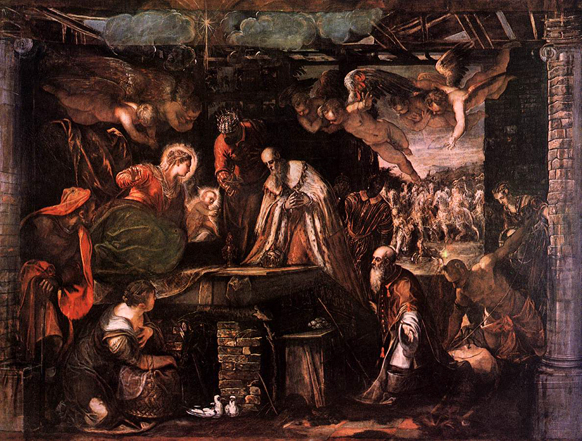

The Adoration of the Shepherds: 1579-81

The Presentation of Christ in the Temple: 1550-55

On the altar steps, which are imitated from Titian's Portrait of the Vendramin Family (ca. 1543/47), Tintoretto sets a scene of action unfolding almost like a film: as the young mother in the foreground of the picture goes down the steps after performing the ritual, Mary has approached the altar. Once she has made the requisite offerings for ritual purification and presented her son, the next woman, already visible with her child in her arms below the altar, will ascend the steps to the priest. The special importance of the presentation of Christ is expressed by the intent manner of the bystanders as they watch what is going on at the altar.

The Temptation of Adam: 1551-52

This work together with the Creation of Animals and the Murder of Abel, created between 1550 and 1553, was originally in the Scuola della Trinità.

Adam and Eve are depicted not in a landscape thrown into confusion by the hand of the Creator but in a more serene, more human dimension. In the leafy arbor the two nude figures moving around the trunk of the tree form the parallel diagonals of the composition. A strong light gives a sculptural effect to their ivory-pink flesh. But in the background, on the right, the tranquility of the foreground scene gives way to the tumultuous epilogue to the fact of human disobedience to Divine will. With rapid brushstrokes Tintoretto evokes the fiery angel who drives Adam and Eve out into the distant desolate hills and plains.

Eve, temptation personified, is pressing close to the tree of knowledge; her arms prolong the line of the serpent thrusting down from above. Tintoretto confidently shows that he has now perfectly mastered not only the sculptural structure of a muscular, sinewy male body (a particular strength of Florentine painters, especially of Michelangelo) but also the reproduction of female grace and tenderness (the domain of Venetian artists, particularly Titian).

The Murder of Abel: 1551-52

This work together with the Creation of Animals and the Temptation of Adam, created between 1550 and 1553, was originally in the Scuola della Trinità.

On seeing from the rising smoke that God has accepted the animal sacrificed by his brother Abel rather than the fruits of the field he himself brought as an offering, Cain's jealousy makes him the first murderer. Tintoretto portrays the scene as a primeval drama, with Abel sacrificed, as it were, on his own altar. He is already bleeding from a gaping head wound, and next Cain will strike him with the splintered end of his club. Ideas for the male nude, shown contorted and foreshortened, came from a painting by Andrea Schiavone (Galleria Palatina, Florence) and a ceiling picture by Titian (Santa Maria della Salute, Venice).

Creation of the Animals: ca 1540

One of the major achievements of Tintoretto's early works is the series of canvases painted in about 1550 for the Sala dell'Albergo of the Scuola della Santissima Trinita. And of these the Creation of the Animals is certainly unique for the swirling rhythm of the composition. In a blaze of golden light, which does not entirely escape the darkness still partly enveloping the newly created earth God the Father is portrayed as if suspended in mid-air in the act of creation. The animals rush forward from behind him while the birds shoot across the sky and the fishes dart through the water like arrows from his hand. The dramatic wind-swept scene is furrowed by the profiles of the animals which cross the canvas in running lines, conveying with extraordinary concision and expressiveness the theme of the work.

Like Pietro Aretino's novel on the subject of Genesis, Tintoretto's painting shows the unicorn (right). The alleged curative and decontaminating qualities of the narwhal tusk, an essential item in every Renaissance cabinet of curiosities, were regarded as proof of the existence of this fabulous creature. Exotic creatures like the ostrich walking on the shore were much admired as gifts from guests to the princely courts of northern Italy, and were portrayed in drawings or engravings. As a true Venetian, however, Tintoretto here devotes particular artistic skill to the fishes, including sturgeon, salmon and red mullet.

Tintoretto's model for this composition was Titian's Bacchus and Ariadne (National Gallery, London); he adopted the flying divine figure as well as the setting.

Towards 1546 Tintoretto painted for the church of the Madonna dell'Orto three of his leading works - the Worship of the Golden Calf, the Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple, and the Last Judgment now shamefully repainted. He took the commission for two of the paintings, the Worship of the Golden Calf and the Last Judgment, on a cost only basis in order to make himself better known. He settled down in a house hard by the church. It is a Gothic edifice, looking over the lagoon of Murano to the Alps, built in the Fondamenta de Mori, which is still standing.

The Presentation of the Virgin: 1553-56

This painting, consisting of two vertical halves now stitched together in the middle, once adorned the outsides of two organ wings. The monumental stairway indicates the musical connection; its 15 steps or "grades" refer to the 15 graduals, the psalms sung by pilgrims in annual temple processions. The singers' gallery above the organ was also painted by Tintoretto. The dark carving of the breastwork and the frames of the wings were partly gilded, like the stairway in the painting; Tintoretto picked out its undulating ornamentation in gold leaf. This "Byzantine" stylistic element is particularly effective in the shadowy area on the left, where it produces a sense of mystic illumination. The richly decorated steps on Mary's way into the temple are reminiscent of the Scala dei Giganti in the interior courtyard of the Ducal Palace, the lower section of which, like the stairway up to the temple, has 15 steps. Like the high priest in Tintoretto's picture, the Doge used to receive important guests on this staircase.

The Last Judgment: 1560-62

In the years when Veronese was producing his monumental banqueting scenes, Tintoretto also painted some large scale works: the Adoration of the Golden Calf and the Last Judgment in the presbytery of Madonna dell'Orto are both almost fifteen meters high. The difference between the painters is evident. Veronese's works are brilliantly variegated, but Tintoretto deliberately dispenses with harmony and composure. Instead he favors a glaring, sultry light, in which the tense postures of the figures and the strained perspective are used for expressive effect.

Tintoretto's Last Judgment is a systematic summary of Titian's and Michelangelo's great models in a judgment that resembles a flood. The height of the painting and a skilful manipulation of the point of view enable the artist to create the illusion that the slanting cosmic deluge is poring over to the viewer.

Iconographically, this is probably Tintoretto's most complex painting, and it has still not been fully interpreted. The artist shows the Last Judgment as a raging elemental event of cosmic dimensions. If, as is often claimed, Tintoretto ever strove to achieve a synthesis of Titian and Michelangelo, then it was here, where he combines the composition of the Gloria of 1553 for Charles V with the monumentality of the wall painting of the Sistine Chapel. As in late medieval northern panel painting, Christ is shown as judge of the world, with the lily of mercy and the sword of righteousness, while the Virgin Mary and John the Baptist intercede for resurrected mankind. A particularly unusual feature is the depiction of The Last Judgment as a catastrophe involving flooding.

Moses Receiving the Tables of the Law: 1560-62

While Moses, transfigured by divine light, receives the tablets, the Jews collect gold from which to fashion the calf. A clay model has already been prepared. The enormous dimensions of the work emphasize the contrast of high against low, religion against idolatry, and the spiritual splendor of heaven against the material brilliance of metal.

The giving of donations to make the Golden Calf is depicted in the lower part of this picture: four strong men carry a wax or clay model of the calf through the Israelite camp, and jewelry and golden vessels are being collected in baskets. Women are helping each other to remove their earrings. Aaron, maker of the idol, is seated in the foreground right. In conversation with the skilled craftsman Belzaleel (with compasses) and his assistant Oholiab, he is giving orders for the placing of the Calf - it is to go on the altar in front of the picture, in the choir of the Madonna dell'Orto itself.

Other Paintings in the Church of Madonna dell'Orto (1552-62)

The Martyrdom of Saint Paul: ca 1556

Just before he is beheaded with a huge two-handed sword, Paul raises his bound hands in a last prayer. An angel is bringing him a laurel wreath and the palm of martyrdom. The armor, which appears much too powerful for his emaciated old body, is armor in the ancient Roman style.

The Vision of Saint Peter: ca 1556

According to the legend, a vision of the Cross brought Peter back to Rome where he was crucified upside down. The four angels, reminiscent of flying figures in Michelangelo's Last Judgment, have partially transparent wings of different colors. They may be the four archangels Michael, Gabriel, Raphael, and Uriel, or they may symbolize the four theological virtues of the Love of God, Charity, Faith, and Hope. The two angels at the top, at least, were probably painted from the same three-dimensional model. Tintoretto intentionally places the golden key of heaven between Saint Peters thighs. Contemporary comedies leave us in no doubt about the erotic symbolism of the key. It was also the subject of the satirical piece La chiave (The Key) by Tintoretto's friend Anton Francesco Doni. Since Peter is clearly shown here as the first pope, this daring pictorial joke may be seen as evidence of the widespread anti-papal feeling in Renaissance Venice.

The Miracle of Saint Agnes: ca 1577

The fifteen-year-old Agnes rejected the advances of Licinius, son of the Roman prefect, on the grounds that she was the Bride of Christ, and was thereupon taken away to a brothel. When Licinius came with his companions to rape her, God struck him dead. At the pleas of the prefect - shown here clad in majestic red - Agnes brought him back to life through her prayers, but was then executed as a witch. The gang rape of a prostitute, unfortunately, was not unknown in Venice: known as trentuno ("thirty-one") it was popular among the sons of patricians as a way of "punishing" insubordinate courtesans.

In 1548 he was commissioned for four pictures in the Scuola di S. Marco - the Finding of the body of Saint Mark in Alexandria (now in the church of the Angeli, Murano), the Saint's Body brought to Venice, a Votary of the Saint delivered by invoking him from an Unclean Spirit (these two are in the library of the royal palace, Venice), and the highly and justly celebrated Miracle of the Slave. This last, which forms at present one of the chief glories of the Venetian Academy, represents the legend of a Christian slave or captive who was to be tortured as a punishment for some acts of devotion to the evangelist, but was saved by the miraculous intervention of the latter, who shattered the bone-breaking and blinding implements which were about to be applied.

Four paintings for the Scuola Grande di San Marco -1548

The walls of the Chapter Hall of the Scuola Grande di San Marco were once adorned with pictures by Tintoretto and later additions by his son Domenico. During the Napoleonic period Tintoretto's paintings were dispersed. The Scuola was converted into a hospital, and the former Chapter Hall now contains a library of medical history.

Tintoretto's Miracle of Saint Mark Freeing the Slave, which was installed on the southern end wall of the Chapter Hall in April 1548, is now in the Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan. The later three-part cycle representing miracles worked posthumously by Saint Mark, commissioned from Tintoretto in 1562 is now in the Gallerie dell'Accademi in Venice.

The Miracle of Saint Mark Freeing the Slave: 1548

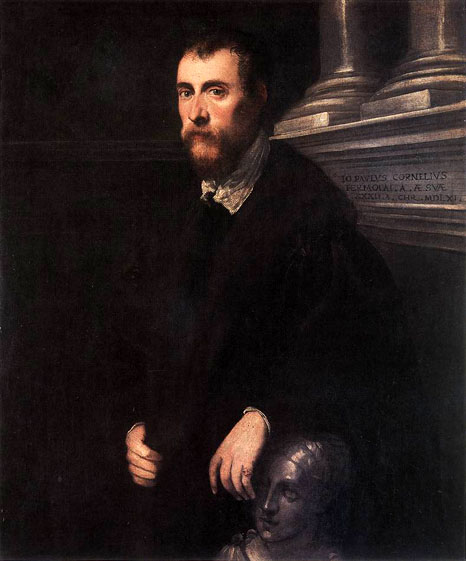

The painting is the first of a series of works, painted in 1548 for the Scuola Grande di San Marco while Marco Episcopi, his future father-in-law was Grand Guardian of the School.

The subject of the huge canvas is the miraculous appearance of Saint Mark to rescue one of his devotees, a servant of a knight of Provence, who had been condemned to having his legs broken and his eyes put out for worshipping the relics of the Saint against his master's will. The scenes takes place on a kind of proscenium which seems to force the action out of the painting towards the spectator who is thus involved in the amazement of the crowd standing in a semi-circle around the protagonists: the fore-shortened figure of the slave lying on the ground, the dumbfounded executioner holding aloft the broken implements of torture, the knight of Provence starting up from his seat out of the shadow into the light, while the figure of Saint Mark swoops down from above.

In keeping with the drama of the action is the tight construction of the painting, the dramatic fore-shortening of the forms and sudden strong contrast of light and shade.

Saint Mark Working Many Miracles: 1562-66

This painting was executed for the hall of the Scuola Grande di San Marco with three other canvases (now in the Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice).

A masterpiece of Tintoretto's full maturity, this painting is a profound expression of his originality. It creates a lyric spectacle out of extreme disquietude. In fact, it expresses a visionary notion that borders on the hallucination, and in this way the scene of the stealing of the body becomes a meteoric display. A memorable image is created that has the impact of a clap of thunder at a witches' ritual.

It has recently been shown that this picture does not, as was long assumed, show the rediscovery of the body of Saint Mark on June 25, 1094, but various miracles of healing worked by the Patron Saint of Venice: he is depicted raising a man from the dead, restoring a blind man's sight, and casting out devils. As in The Miracle of the Slave, which he painted for the same location, Tintoretto illustrates the power of Saint Mark by placing the invisible guidelines of his construction of the perspective in the Saint's outstretched hand. The donor Tommaso Rangone, who claimed great healing powers for himself, thereby making large sums of money, had his own figure painted kneeling humbly, but none the less wearing the magnificent golden robe of a cavalier aurato. Doge Girolamo Priuli had only recently bestowed the title of "Golden Knight" on him.

Tintoretto has adopted here and carried further the expressive means of Tuscan and Roman Mannerism. There is the explosive perspective (note how the peak of the visual pyramid coincides with the raised hand of the saint performing the miracle). There are the dynamic crossing of the compositional diagonals, the nervous contortion and the bold foreshortening of the figures. Then there is the light from various sources that erupts from the tombs or spreads from the mouth of the Long Hall, like a nocturne in the porticoes of Saint Mark's. It prints rainbow along the bays, leaving an impression of instability and obsession. Finally there is the macabre element of the tomb-robbing scene and the anxiety of the jumble of figures in the foreground. Unreality reaches a peak in the pictorial rendering. The disintegration of the color, an inheritance from Titian's late work, is seen in the dissociation of the brushstrokes from the material and their flickering, like a multitude of flames, against a somber and blurred surface.

The Stealing of the Dead Body of Saint Mark: 1562-66

In 1562 Tintoretto was commissioned by the Guardian Grande, Tommaso Rangone to complete the decoration of the School of Saint Mark. This work from the Sala Capitolare relates the episode in which the Christians of Alexandria, taking advantage of a sudden hurricane, take possession of the Michelangelesque body of the Saint which was about to be burned by the pagans. The group in the foreground (where Rangone himself is depicted bearing the head of the Saint) stands out sculpturally from the vertiginous depth of the background created by the use of light and by the obsessive architectural sequence of arcades and mullioned windows which terminate in the phosphorescence of the construction outlined against a reddish sky heavy with clouds. Light assumes an elemental role in this phantasmagoric scene. A curiously prominent role is played by the dromedary that has escaped from his owner.

Saint Mark Rescuing a Saracen from Shipwreck: 1562-66

The picture was originally intended to be the left "wing" of a three-part cycle showing posthumous miracles of Saint Mark. The Saint's soul has materialized in this painting top right, where Saint Mark is shown as a flying figure coming in haste to rescue a Saracen who has called on him in his hour of need, and conveying him to a lifeboat as a reward for his conversion. The symbol of the power of God's own aid symmetrically balances the figure of the Saint, manifesting itself as a mysterious cloud in human form. The lower edge of the picture shows the donor Tommaso Rangone with his golden knightly robe flung back, helping another Muslim into the Christian boat.

The figures form a diagonal which is continually broken to indicate the fury of the natural elements. The stormy sea and wind-tossed clouds evoke the meteorological conditions in

a way which is almost over-dramatized. This is, however, a superb example of the visionary and fantastical style of Tintoretto, who uses light to convey the desired appearance of reality.

These four works were greeted with signal and general applause, including that of Titian's intimate, the too potent Pietro Aretino, with whom Tintoretto, one of the few men who scorned to curry favor with him, was mostly in disrepute. It is said, however, that Tintoretto at one time painted a ceiling in Pietro's house; at another time, being invited to do his portrait, he attended, and at once proceeded to take his sitter's measure with a pistol (or a stiletto), as a significant hint that he was not exactly the man to be trifled with. The painter having now executed the four works in the Scuola di S. Marco, his straits and obscure endurances were over.

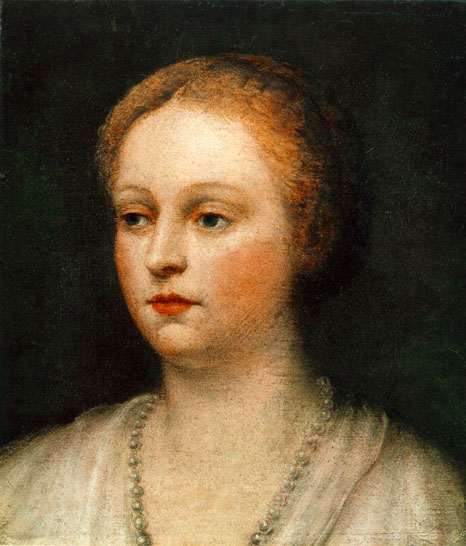

In 1550 he married Faustina de Vescovi daughter of a Venetian nobleman and a prominent member of the Scuola de San Marcos. She appears to have been a careful housewife, and one who both would and could have her way with her not too tractable husband. Faustina bore him several children, probably two sons and five daughters. The mother of Jacopo's daughter Marietta, a portrait painter herself, was probably a German woman, who had an affair with Jacopo before his marriage to Faustina.

The next conspicuous event in the professional life of Tintoretto is his enormous labor and profuse self-development on the walls and ceilings of the Scuola di S. Rocco, a building which may now almost be regarded as a shrine reared by Tintoretto to his own genius. The building had been begun in 1525 by the Lombardi, and was very deficient in light, so as to be particularly ill-suited for any great scheme of pictorial adornment. The painting of its interior was commenced in 1560.

In that year five principal painters, including Tintoretto and Paolo Veronese, were invited to send in trial-designs for the centre-piece in the smaller hall named Sala dell'Albergo, the subject being S. Rocco received into Heaven. Tintoretto produced not a sketch but a picture, and got it inserted into its oval. The competitors remonstrated, not unnaturally; but the artist, who knew how to play his own game, made a free gift of the picture to the saint, and, as a bylaw of the foundation prohibited the rejection of any gift, it was retained in situ, Tintoretto furnishing gratis the other decorations of the same ceiling.

In 1565 he resumed work at the scuola, painting the magnificent Crucifixion, for which a sum of 250 ducats was paid. In 1576 he presented gratis another centre-piece - that for the ceiling of the great hall, representing the Plague of Serpents; and in the following year he completed this ceiling with pictures of the Paschal Feast and Moses striking the Rock accepting whatever pittance the confraternity chose to pay.

Paintings in the Scuola Grande di San Rocco

The Scuola Grande di San Rocco was founded in the late fifteenth century. It is one - and certainly the best preserved - of Venice's six Scuole Grandi (Major Guilds) which for many centuries, together with the minor Confraternities, formed the network of brotherhoods of religious nature. These were set up to help the poor and sick, or to protect the interests of individual professions, or to help the weak and needy members of non-Venetian communities living in the city. The Scuola Grande di San Rocco was very popular because its patron saint was renowned for offering protection from the plague, an increasingly common threat. The guild, dedicated to San Rocco of Montpellier who died in Piacenza in 1327 and whose remains are thought to have been brought to Venice in 1485, was legally recognized in 1478.

After several transfers the Scuola's headquarter was built on the Campo di San Rocco. The grandiose building was begin in 1517 and the finishing touches lasted until 1560. Four years later Jacopo Tintoretto began his pictorial decorations of the rooms. This work, which took him until 1588, constitutes one of the most fascinating pictorial undertakings ever known: from 1564 to 1567 the 27 canvases on the ceiling and walls of the Sala dell'Albergo (Hall of the Hostel), from 1576 to 1581 the 25 canvases on the ceiling and walls of the Sala Superiore (Upper Hall); from 1582 to 1587 the eight large canvases in the Sala Inferiore (Ground Floor Hall); in 1588 the altarpiece.

View of Campo di San Rocco: 1517-60

The Scuola Grande di San Rocco is the best preserved, as regards the architecture and fittings, of Venice's six Scuole Grandi (Major Guilds) which for many centuries, together with the minor Confraternities, formed the thick network of brotherhoods of a religious nature. These were set up to help the poor and the sick, or to protect the interests of individual professions, or to help the weak and needy members of non-Venetian communities living in the city.

The guild dedicated to San Rocco of Montpellier who died in Piacenza in 1327 and whose remains are thought to have been brought to Venice in 1485, was legally recognized in 1478. Its aim was to relieve the suffering of the sick, especially those stricken by the epidemics.

The present building of the Scuola was begun in 1517 by Bartolomeo Bon who designed it and supervised the work until 1524. The basic part of it was finished in 1549, but the finishing touches to the building lasted until 1560.

The photo shows the Campo di San Rocco with the Scuola at the left and the church of San Rocco at the right.

View of the Sala dell Albergo: 1564-67

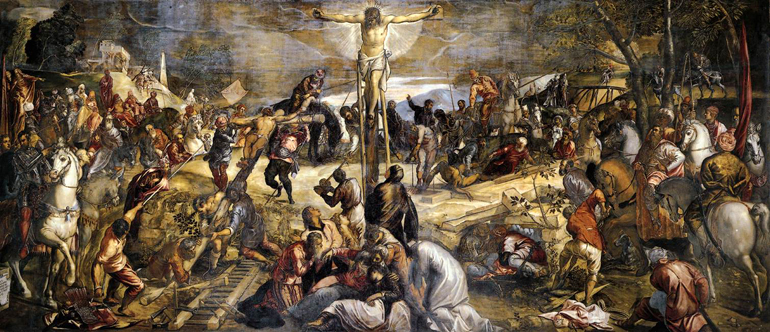

In 1564, Tintoretto decorated the ceiling of the Sala dell'Albergo with a central oval canvas, representing the Apotheosis of St Roch, surrounded by 16 allegories of various size: the Seasons, the allegories of the Scuole Grandi of Venice, the Virtues. On the largest wall of the room he finished the huge Crucifixion in 1565, then for the other walls, in 1566-67 he painted three more canvases related to the Passion of Christ (Christ before Pilate, Crowning with Thorns, Christ Carrying the Cross). Two figures of prophets were added to the decoration by Tintoretto's workshop.

The Sala dell Albergo: 1564-67

The Sala dell'Albergo was the first room of the Scuola decorated by Tintoretto. The decoration contains scenes of Christ's Passion. The paintings are memorable for their stringent compositional vigor and intense pathos.

On the end wall is an immense Crucifixion, which is one of the painter's most remarkable achievements. The painting focuses on the dramatic moment when the Cross is being raised upright. The scenes of the Christ before Pilate, Ecce Homo, and Christ Carrying the Cross form a dramatic trio on the wall facing the Crucifixion. Tintoretto varied the compositions and proportions of the paintings, yet managed to keep the narrative coherent.

Christ Carrying the Cross: 1565-67

Tintoretto decorated the walls of the Sala dell'Albergo by paintings showing important moments from the Passion of Christ and he finished them in the early months of 1567.

This agitated scene is set along a route rising at an acute angle; the first side, reading from left to right, is in deep shadow against which the chromatic tones of white, red, green, blue, yellow-orange of the robes of the two thieves and their escorts stand out vividly; the second part of the procession is done in full light against the sulphur-colored sky streaked with pink. It opens up with the dominating soldier seen against the light in the foreground who is holding the rope tied around Christ's neck and it is closed by the brightly colored group of pious women preceded by the soldier who lets the pale pink standard flutter in the wind.

Christ before Pilate: 1566-67

Tintoretto decorated the walls of the Sala dell'Albergo by paintings showing important moments from the Passion of Christ and he finished them in the early months of 1567.

The most admired has always been Christ before Pilate. Perhaps while painting it Tintoretto partially kept in mind one of the wood-engravings by Albrecht Durer, evidence of the lasting spell held by German graphics of the first half of the 16th century over the imagination of the protagonists of Venetian Mannerist interpretations. The dramatic staging of the scene is however completely original. In a very fine and measured luministic web the figure of Christ, wrapped in a white mantle, stands out like a shining blade against the crowd and the architectural scenery. He is centered by a bright ray of light and stands tall in front of the hypocritically bureaucratic judge that is Pilate who is portrayed in red robes and as if sunk in shadows. Certainly taking up the idea of Carpaccio in his Saint Ursula cycle, Tintoretto portrays the old secretary at the foot of Pilate's throne. He leans against a stool covered with dark green cloth and with great diligent enthusiasm notes down every moment, every word spoken by the judge amid the murmurings of the pitiless crowd which obstinately clamors for the death of Christ.

Christ before Pilate (Detail): 1566-67

The small crowd is stunned, Pilate shuns responsibility, the Turkish dignitary tugs at the stole that marks his rank, and the scribe does not know what to write. In any case, what can he possibly record if Christ, wearing the white robe of madness, says not a single word?

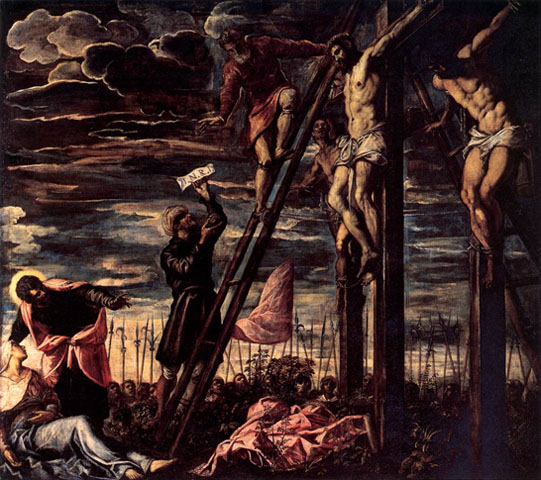

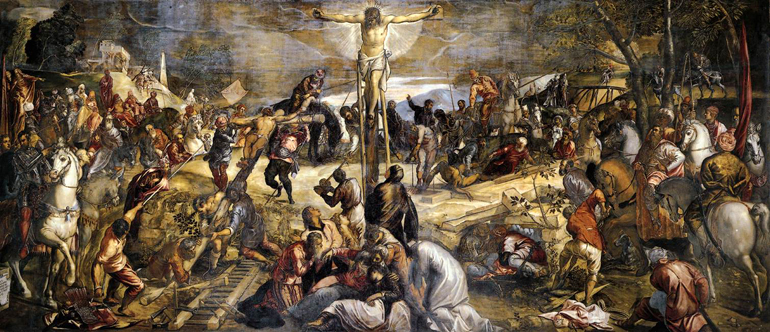

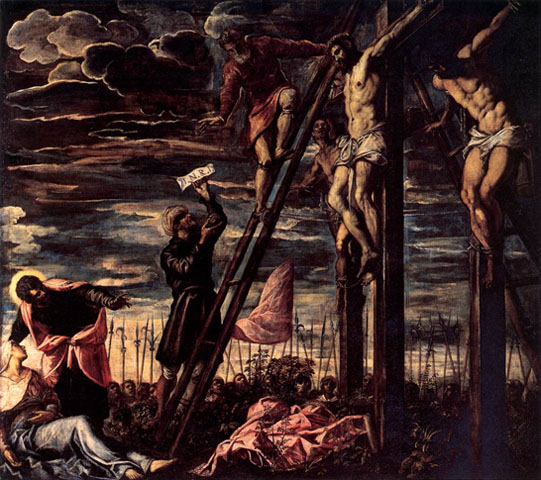

Crucifixion: 1565

Tintoretto's Crucifixion in the Sala dell'Albergo presents a panorama of Golgotha populated by a crowd of soldiers, executioners, horsemen, and apostles. At the left the cross of the penitent thief is being partly lifted, partly tugged into place by ropes; at the right the impenitent thief is about to be tied to his cross. A soldier on a ladder behind Christ reaches down to take the reed with the sponge soaked in vinegar from another soldier on the ground. The tumult of the crowd, the grief of the apostles, and the yearning of the penitent thief seem to come to a focus in the head of Christ.

Owing to Tintoretto's light-on-dark technique, his figures sometimes have a tendency to look a bit ghostly, but the foreground figures in the Crucifixion, grouped in a massive pyramid at the base of the cross, are defined by vigorous contours and are modeled to create a strong sculptural effect. The little group, huddled as if for protection against the hostile crowds, form the base of the composition.

Crucifixion (Detail): 1565

_1565.jpg)

This detail represents the central part of the huge composition.

Crucifixion (Detail): 1565

_1565.jpg)

In the good and bad thieves to the left and right of Christ, who is already crucified, Tintoretto depicts different phases of the execution.

Tintoretto used Hans Baldung Grien's print as the model for the erection of the cross of the Good Thief. The likeness is particularly evident in the angle of the upright of the cross and the figures of the four executioners in front. He has moved the centurion from the right to the left of the picture. Tintoretto's greater consistency of perspective foreshortenings in the bodies of the executioners and their victim suggests that as usual he checked his model against living sitters.

Paintings in the church of San Rocco

Saint Roch in the Hospital: 1549

In this painting on the wall of the church of San Rocco, depicting the story of the healer saint's visit to the lazar house, the preoccupations of assistance combine with hospital propaganda at the scuola Grande di San Rocco. It is a breathtaking interpretation of an astonishing court of miracles.

Saint Roch in the Hospital (Detail): 1549

_1549.jpg)

The plague was a constant danger in the harbor city of Venice, and the state sought to counter it by taking careful precautionary measures, for instance the building of the Lazzaretto Nuovo as a quarantine hospital around 1470. Tintoretto's painting could equally well show the plague hospital of the Lazzaretto Vecchio, also built on an island in the lagoon as early as 1423. The young women shown here entering from the sides of the picture to wash the sick, bind up their sores, and feed them, are probably unemployed prostitutes, who were pressed into service in the Lazzaretto Vecchio in times of plague.

Saint Roch in Prison Visited by an Angel: 1567

The death in prison of Saint Roch serves as the pretext for a pitilessly realistic depiction of a prison cell. As if in an image of hell, various levels of punishment can be made out. While the seated man in the left foreground is closely chained to the damp wall, the prisoner standing next to him can exchange a few words with the guard at the round hatch. A thief with his hand cut off as punishment is visible through the grating in the floor. A companion lowers food into this desolate dungeon. To the amazement of the prisoners, an angel of comfort comes flying in, unimpeded by the iron grating on the right of the cell.

The flying angel was obviously painted from the same three-dimensional model as Saint Mark in The Miracle of the Slave of some 20 years earlier. Since even the hem of the garment fluttering up above the left calf is exactly the same in both paintings, we may assume that the wax or clay figure which served Tintoretto as model was clad in fabric stiffened with glue or plaster. The fragile model probably hung for decades from a beam in the roof of Tintoretto's dark, private laboratory, and was thus preserved from damage.

Paintings in the Sala Inferiore - 1583-87

Between July 1583 and August 1587, Tintoretto returned to work in the Scuola Grande di San Rocco. Nearly seventy years old, he painted eight large canvases on the walls of the Sala Inferiore (Ground Floor Hall), a fine interior whose roof beams are supported by two rows of slender columns. The tempestuous energy and passion for the light that animated the earlier works for the Scuola had given way to a more contemplative and spiritual vision. In August 1587 the placing of the Circumcision in the Sala Inferiore completed the decoration of the receiving rooms of the Scuola.

View of the Sala Inferiore: 1583-87

Between July 1583 and August 1587, Tintoretto returned to work in the Scuola Grande di San Rocco. Nearly seventy years old, he painted eight large canvases on the walls of the Sala Inferiore (Ground-floor Hall), a fine interior whose roof beams are supported by two rows of slender columns. The tempestuous energy and passion for the light that animated the earlier works for the Scuola had given way to a more contemplative and spiritual vision.

The Annunciation: 1583-87

The painting is on the wall of the Sala Inferiore of the Scuola Grande di San Rocco. With its unusual perspective that places the viewer in mid-air, looking down into the house of Mary, this Annunciation is one of the most intimate works of the cycle in the room. Tintoretto multiples the perspective details, such as the straw-bottomed chair below the angel, which emphasizes the poverty of the Virgin.

Of the eight phases into which the Venetian Theatine monk Giovanni Marinoni (1490-1562) divided the story of the Annunciation, Tintoretto's painting shows the second, following the angel's greeting: "And when she saw him, she was troubled at his saying, and cast in her mind what manner of salutation this should be" (Luke 1:29). In late medieval painting north of the Alps, Mary's conception is often shown as a depiction of the infant Christ flying toward the Virgin on a divine ray of light, like a naked putto. As if to follow the path of the heavenly child's flight exactly, Tintoretto multiplies this motif into a whole phallic swarm of putti.

The announcement of the imminent divine maternity is given by the Angel to Mary in surroundings where everything is realistically described down to be the smallest detail: the dilapidated brick base and column; the two-colored floor of large marble tiles; the straw-bottomed chair which clearly shows the passing of time; the work basket and its contents at the Virgin's feet; in the background the large bed covered by a canopy. No less realistic, even if in a theatrically scenographic sense, is the outside setting where Joseph is busy with his work surrounded by carpenter's tools hung outside the hut. Such objective description of the surroundings is contrasted with the visionary intensity of the miraculous apparition of the heavenly messenger and the joyful evangelical song, which break in from the left. They are preceded by the Holy Spirit in the form of a snow-white dove with unfolded wings, almost perpendicularly above the Virgin's head.

In some details the hand of Domenico Robusti, Tintoretto's son, has been correctly recognized.

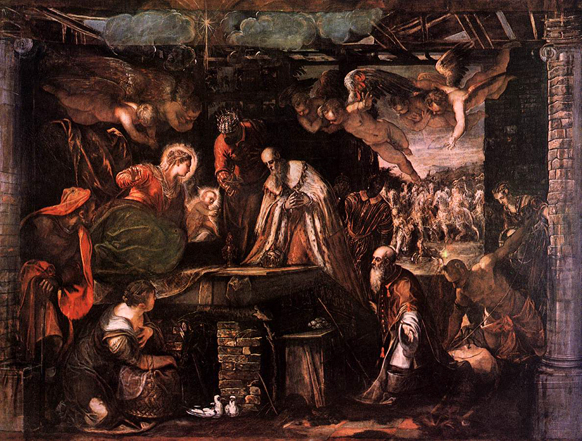

The Adoration of the Magi: 1582

The Adoration of the Magi was completed in July 1582 and was therefore the first of the canvases of this series in the Ground Floor Hall to be carried out.

Above and along the brick walls and the wooden planks, the episode unfolds frontally under bright light which makes the physical and emotional gestures of the Wise Men stand out. The harmonious night setting of the foreground gives way in the background on the right to the apparition of the procession of the Three Kings, broken up by traces of glowing light. The procession advances slowly from far-off lands guided by the star which has arrived directly above the Holy Child's head.

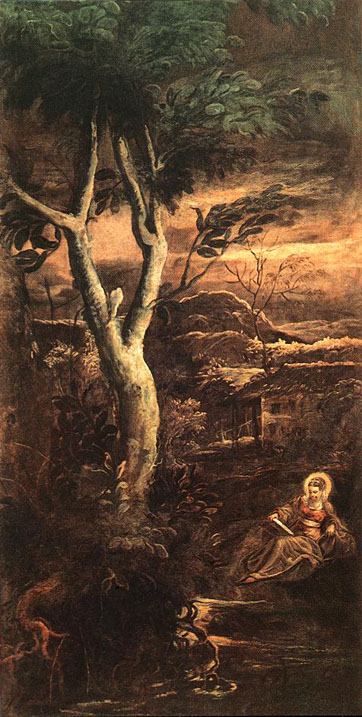

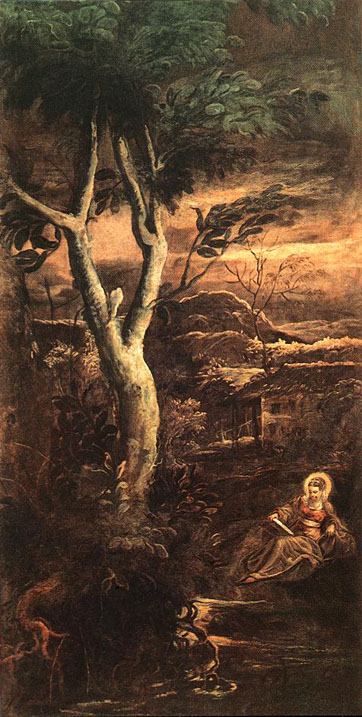

The Flight into Egypt: 1582-87

As so often with Tintoretto, this painting is matched with the utmost exactitude to its situation on the ground floor Sala Inferiore of the Scuola Grande di San Rocco: in the arching branch on the left, the curve of the palm fronds on the right, and the roughly circular view of the sky at the centre, the painter echoes the shape of the windows flanking the picture with astonishing precision. Like the needy people who waited for charitable donations on the bench below the painting, the Holy Family seems to be fleeing hopefully out of the picture and into the Sala Inferiore of the Confraternity of Saint Roch itself.

In the wooded hollow, after furtively avoiding every inhabited place, Mary and Joseph together with the Holy Child, prepare to take a rest. On the left, in the foreground, in the web of dull greens, browns and whites of the landscape, the group of fugitives and their humble packs are depicted with concise reality in every element of form and color. On the right the landscape scene, built up with extraordinary, quick brush-strokes and enlarged into fathomless depths, opens out.

Tintoretto's sensitivity to simple and popular forms of religious practice, with subdued yet mystical overtones, here produces an intensely poetic effect. The trees, water, living creatures, and clouds all seem caressed by a glimmering light that gives them an unearthly intensity.

The Massacre of the Innocents: 1582-87

This is a violently dramatic, cruel scene, every figurative borrowing from Michelangelo, from Raphael and from the Mannerist sculptors, in particular from Giambologna, is transferred and absorbed in a new image of Tintoretto's vision of harmonious dramatic force.

With intense inner involvement, Tintoretto presents a picture of masculine brutality and feminine courage. As always, he uses not faces but bodies, draperies, lighting, color, and artistic technique to convey expression. The dreadful marks on the ramp of the stairway, for instance, appear as if painted in real blood. The glance of the woman at the lower edge of the picture suggests that her right arm, cut short by the edge of the picture itself, was once stretched out into the viewer's own world in a plea for help. To achieve this literally gripping effect, Tintoretto may have attached an arm made of plaster or stucco to the picture, as many Baroque painters later did.

On the left a high wall blocks all means of escape; on the right in the background a portico can be glimpsed which opens onto a wooded landscape where the cruel massacre continues. All the details are of epic expressive violence and some attain high points of poetic effectiveness.

Saint Mary Magdalen: 1582-87

In the Sala Inferiore there are two paintings of a solitary woman in a twilit, well-wooded and -watered landscape. Traditionally, but unconvincingly, the women are identified as Saint Mary Magdalen and Saint Mary of Egypt, penitent hermits who have nothing to do with context of the decoration of the room. The woman is the same in both paintings sitting in two adjacent spots by the same stream and wearing the same clothes. In one painting she faces the observer virtually head-on and in the other almost completely turns her back on us. In one pose she lowers her gaze to her closed book and in the other raises her eyes from the now open book in rumination. In all likelihood this is a dual picture of Mary as the protagonist of the story of redemption.

Saint Mary Magdalen is captured from the front, engrossed in reading, and given prominence like the large tree trunk on the left by a phosphorescent light falling on a magically mysterious nature. She is succinctly defined in the final fleeting instant before the night shadows fall on the outline of the rustic cottages, on the rolling plains, on the ridges of the hills and mountains.

Like the landscape with the figure of Saint Mary of Egypt, this work too was influenced by northern models: it suggests the paintings and prints of the Danube School (for instance by Albrecht Altdorfer and Wolf Huber), and woodcuts by Hans Baldung Grien, the Nuremberg graphic artist Virgil Solis, and the mysterious artist, known only by his monogram of HWG, who depicts Saint John the Evangelist on Patmos, surrounded by a fantastic landscape.

Saint Mary of Egypt: 1582-87

The Circumcision: ca 1587

This richly colored, busy scene is the last canvas painted for the Ground Floor Hall and it was placed in its actual position in August 1587. Restoration in 1970 has confirmed the participation of Tintoretto's workshop, including Tintoretto's son Domenico, in the painting, a fact already recognised by all the critics.

The Assumption of the Virgin: 1582-97

The Virgin rises up to heaven pushed by a sudden gust of wind which separates the postures of the apostles. Each one is caught in a particular emotional moment in front of the miraculous happening and is drawn in by numerous feelings: incredulity, marvel, ecstatic adoration.

From the seventeenth century onwards this painting underwent many restorations which considerably altered it.

Tintoretto next launched out into the painting of the entire scuola and of the adjacent church of Saint Rocco. He offered in November 1577 to execute the works at the rate of 100 ducats per annum, three pictures being due in each year. This proposal was accepted and was punctually fulfilled, the painter's death alone preventing the execution of some of the ceiling-subjects. The whole sum paid for the scuola throughout was 2447 ducats. Disregarding some minor performances, the scuola and church contain fifty-two memorable paintings, which may be described as vast suggestive sketches, with the mastery, but not the deliberate precision, of finished pictures, and adapted for being looked at in a dusky half-light. Adam and Eve, the Visitation, the Adoration of the Magi, the Massacre of the Innocents, the Agony in the Garden, Christ before Pilate, Christ carrying His Cross, and (this alone having been marred by restoration) the Assumption of the Virgin are leading examples in the scuola; in the church, Christ curing the Paralytic.

It was probably in 1560, the year in which he began working in the Scuola di S. Rocco, that Tintoretto commenced his numerous paintings in the ducal palace; he then executed there a portrait of the Doge, Girolamo Priuli. Other works which were destroyed in the great fire of 1577 succeeded - the Excommunication of Frederick Barbarossa by Pope Alexander III and the Victory of Lepanto.

After the fire Tintoretto started afresh, Paolo Veronese being his colleague; their works have for the most part been disastrously and disgracefully retouched of late years, and some of the finest monuments of pictorial power ever produced are thus degraded to comparative unimportance.

In the Sala deilo Scrutinio Tintoretto painted the Capture of Zara from the Hungarians in 1346 amid a Hurricane of Missiles; in the hail of the senate, Venice, Queen of the Sea; in the hall of the college, the Espousal of Saint Catherine to Jesus; in the Sala dell Anticollegio, four extraordinary masterpieces - Bacchus, with Ariadne crowned by Venus, the Three Graces and Mercury, Minerva discarding Mars, and the Forge of Vulcan which were painted for fifty ducats each, besides materials, towards 1578; in the Antichiesetta, Saint George and Saint Nicholas, with Saint Margaret (the female figure is sometimes termed the Princess whom Saint George rescued from the dragon), and Saint Jerome and Saint Andrew; in the hall of the great council, nine large compositions, chiefly battle-pieces.

We here reach the crowning production of Tintoretto's life, the last picture of any considerable importance which he executed, the vast Paradise, reputed to be the largest painting ever done upon canvas. It is a work so stupendous in scale, so colossal in the sweep of its power, so reckless of ordinary standards of conception or method, so pure an inspiration of a soul burning with passionate visual imagining and a hand magical to work in shape and color, that it has defied the connoisseurship of three centuries, and has generally (though not with its first Venetian contemporaries) passed for an eccentric failure; while to a few eyes it seems to be so transcendent a monument of human faculty applied to the art pictorial as not to be viewed without awe.

While the commission for this huge work was yet pending and unassigned Tintoretto was wont to tell the senators that he had prayed to God that he might be commissioned for it, so that paradise itself might perchance be his recompense after death. Upon eventually receiving the commission in 1588 he set up his canvas in the Scuola della Misericordia and worked indefatigably at the task, making many alterations and doing various heads and costumes direct from nature.

When the picture had been nearly completed he took it to its proper place and there finished it, assisted by his son Domenico for details of drapery, etc. All Venice applauded the superb achievement, which has since suffered from neglect, but little from restoration. Tintoretto was asked to name his own price, but this he left to the authorities. They tendered a handsome amount; he is said to have abated something from it, an incident perhaps more telling of his lack of greed than earlier cases where he worked for nothing at all.

Paintings in the Palazzo Ducale - 1580

Several paintings by Tintoretto were destroyed by the fires in the Palazzo Ducale in 1574 and 1577. After the fires he received commissions for the Palazzo Ducale for allegories, votive pictures and historical paintings. In order to meet his deadlines, Tintoretto delegated to his workshop many of these paintings. However, the four allegorical paintings now in the Anticollegio were executed by Tintoretto himself: the Three Graces and Mercury, the Minerva Sending Away Mars from Peace and Prosperity, the Ariadne, Venus and Bacchus, and the Forge of Vulcan.

The monumental canvas in Sala del Maggior Consiglio representing the Paradise was executed by Tintoretto's workshop under the supervision of his son, Domenico Robusti.

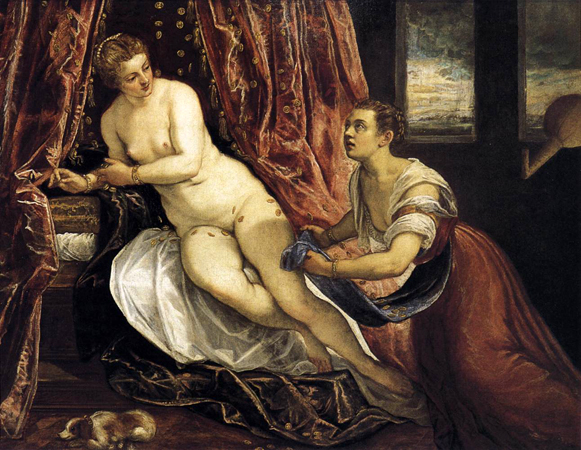

Bacchus, Venus, and Ariadne: 1576-77

Four almost square paintings by Tintoretto, Bacchus, Venus and Ariadne; Minerva Sending Away Mars from Peace and Prosperity; Vulcan's Forge; Mercury and the Graces) are set in stucco frames and arranged symmetrically on the walls of the Sala dell'Anticollegio in the Palazzo Ducale. Originally they were on the walls of the Atrio Quadrato (Square Anteroom) in the same palace. The four works have mythological or allegorical subjects and were originally part of a compact program to celebrate the good government of Doge Gerolamo Priuli. The figures and landscapes enshrine images of concord and prosperity and are classical in inspiration. The paintings were meant by the author to extol the unity and glory of the Venetian Republic.

In Bacchus, Venus and Ariadne, Bacchus arrives from the sea with his wreath and skirt of vine leaves, bearing a bunch of grapes and a ring. Among her rocks and drapes, Ariadne feebly extends her ring finger as an airborne Venus crowns her with stars. Ariadne - discovered by Bacchus on the island of Naxos and crowned by Venus to be received amongst the gods - stands for Venice, born on the sea, graced by divine favor and crowned by freedom. The imagery suggests the mythical marriage of Venice with the sea.

Minerva Sending Away Mars from Peace and Prosperity: 1576-77

In Minerva Sending Away Mars from Peace and Prosperity, a well-nourished Peace, crowned with an olive wreath, and Prosperity, peeping into the scene to fill her cup with splendid fruit, are protected by Minerva. She has left almost all her instruments of war on the ground and pushes back a formidable Mars fully armed.

Vulcan's Forge: 1576-77

Forge, having put to one side the now useless armor, the smith god and his helpers set about making new tools for the progress of humanity. It is winter, yet the olive of peace endures In Vulcan's.

Mercury and the Graces: 1576-77

In the Mercury and the Graces, the Graces intermingle, as complementary and contiguous as the sides of a die, flaunting the rose and myrtle of Venus under Minerva's olive tree. Mercury monitors this admixture of reason, love and peace.

View of the Sala del Collegio

This chamber of the Doge's Palace was used by the Doges for audiences with foreign ambassadors. The ceiling contains paintings by Veronese, while the paintings that line the walls are mostly by Tintoretto.

Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine: 1576

_1576.jpg)

The painting belongs to the series on the wall of the Sala del Collegio by Tintoretto. The sequence of paintings extols the devotion of the Doges. The scenes are rather contrived, since they had to combine the Doges' portraits with a votive subject. Tintoretto invariably managed to avoid the repetitiveness that tended to mar the decorations in the palace after his death. This painting shows the Doge Francesco Donà surrounded by Prudence, Temperance, Eloquence, and Charity.

Doge Nicolo da Ponte Invoking the Protection of the Virgin: 1584

The paintings on the walls of the Sala del Collegio, above the sculpted and gilded wooden wainscot, were executed by Tintoretto and his workshop between 1581 and 1584. The paintings, which include Doge Nicolo da Ponte Invoking the Protection of the Virgin, depict particular moments of the religious and social life of a few doges. The doges are accompanied by their protector saints and the symbolic figures of their human virtues.

View of the Hall of the Senate

The picture shows the view toward the throne in the Hall of the Senate. Above the throne Tintoretto's The Dead Christ Adored by Doges Pietro Lando and Marcantonio Trevisan can be seen. In the centre of the ceiling decoration is the Triumph of Venice by Tintoretto and his son, Domenico Robusti.

Triumph of Venice: 1584

The wooden part of the ceiling of the Hall of the Senate was completed in 1587. The pictorial work began to be realized in 1581 and went on for many years, well beyond 1603. The central painting by Tintoretto (with the assistance of his son, Domenico Robusti) portrays the Triumph of Venice as an ascending vortex of mythological sea creatures which rise towards Venice, seated above, to offer gifts and recognition.

The Dead Christ Adored by Doges Pietro Lando and Marcantonio Trevisan: 1580's

Tintoretto's dramatic painting is on wall above the throne in the Hall of the Senate.

The Dead Christ Adored by Doges Pietro Lando and Marcantonio Trevisan (Detail): 1580's

_1580_s.jpg)

The detail shows the left part of the painting with Doge Pietro Lando.

The Dead Christ Adored by Doges Pietro Lando and Marcantonio Trevisan (Detail): 1580's

_1580_s_Two.jpg)

The detail shows the right part of the painting with Doge Marcantonio Trevisan.

Conquest of Zara: 1584

The Sala dello Scrutinio (Voting Hall) is the second largest hall of the Doge's Palace. The balloting and secret votes of the magistracies and the doge took place in this hall with the very complicated systems that the Venetian Republic had created to avoid intrigues and subterfuge during the elections and, above all, to ensure that the vote could not be bought especially from the poor nobility in favor of its richer equivalent.

The iconographic theme of the Hall of the Sala dello Scrutinio was inspired by the Venetian naval victories on the Eastern seas shown in the numerous ceiling canvases depicting virtues and symbolic figures. Tintoretto's Conquest of Zara is on the right wall upon entering, and it depicts an event of the Fourth Crusade. The Fourth Crusade was the first act of an expedition that aimed at conquering the Holy Land. It ended up subduing the revolt of Zara against Venice and taking over the city of Constantinople after a terrible and systematic pillage. Baldwin of Flanders was elected the new Christian emperor. The Venetian fleet was led by the old but still energetic doge, Enrico Dandolo. The event took place between 1202 and 1204.

View of the Sala del Maggior Consiglio: 1585-90

The picture shows a view of the Sala del Maggior Consiglio (Hall of the Great Council) in the Ducal Palace in Venice. On the end wall Tintoretto and his pupils painted the enormous representation of Paradise. The oval ceiling painting visible here is the Triumph of Venice by Veronese and pupils.

Defence of Brescia: 1584

The present decoration of the Sala del Maggior Consiglio (Hall of the Great Council) in the Palazzo Ducale was realized after the disastrous fire of 1577 during which all the structures of the ship's-keel Gothic ceiling and the wall-paintings were destroyed. An immense flat ceiling, in accordance with the taste of the end of the century, was constructed with gilded cornices sculpted in high-relief, which framed a series of paintings. The canvases were dedicated, thematically, to the Glorification of Venice, in remembrance of the numerous military undertakings in the East or on the mainland by the Venetian ground troops. On the ceiling great importance was given to the victories of the Venetian army in conquering the mainland; along the wall to the dispute between Alexander III and Frederick Barbarossa, who reached an agreement in Venice with the political mediation of Doge Sebastiano Ziani; and to the events of the Fourth Crusade, led by Doge Enrico Dandolo in the early years of the 13th century.

Tintoretto's Defense of Brescia is one of the thirty five panels on the ceiling of the Sala del Maggior Consiglio.

Doge Nicolo da Ponte Receiving a Laurel Crown from Venice: 1584

This painting is one of the large central canvases on the ceiling of the Sala del Maggior Consiglio. It portrays Venice offering an olive-branch crown to Doge Nicolo da Ponte accompanied by the Signoria and scarlet-robed senators.

Paradise: Post 1588

Major fires in the Doge's Palace in 1574 and 1577 necessitated the wholesale renovation of its pictorial decoration, and artists received explicit instructions about subject and even composition, the idea being to emulate the visual authority of the destroyed works as closely as possible. Tintoretto painted several large ceiling panels for the elaborate program, which emphasized Venice's military achievements, celebrated the city's unique form of government, touted civic freedom, and claimed Venice's parity with the papacy and the Holy Roman Empire.

Tintoretto's most important contribution to the enterprise was the replacement of Guariento's 1365 Coronation of the Virgin, located behind the dais on which the Doge and leading patricians sat during meetings of the Great Council. It had been decided that the replacement would continue to center around Christ and Mary, preserving the general paradisiacal theme of Guariento's composition. However, the focus of Tintoretto's Paradise composition was to be Christ rather than Mary, eliminating the flanking scenes of the Annunciation and setting Christ as the supreme authority, to whom Mary is subsidiary. The seething crowds of saints and angels purposefully suggest a Last Judgment, reminding Great Council members of the gravity and enduring significance of their deliberations and actions.

Paradise: Post 1588

In 1557 a serious fire in the Palazzo Ducale destroyed the Sala del Maggior Consiglio, originally the meeting place for the Venetian legislature. The ruined fresco by Guariento was replaced in 1594 by the immense canvas (reputedly the world's largest painting on canvas) planned and painted by Tintoretto and his workshop. Hung above the gilded throne, it depicts the image of Paradise with hundreds of figures placed according to a series of curved lines in concentric perspective with the representations of angels and saints. The movement builds up towards a brilliant central point on high dominated by the figures of Christ and the Virgin.

_Post_1588.jpg)

_Post_1588_Two.jpg)

Paradise: ca 1565

The best description of this picture is by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe: "A Paradise by Tintoretto, or rather the coronation of Mary as Queen of Heaven in the presence of all the patriarchs, prophets, saints, angels, etc., a nonsensical idea executed with the greatest genius. There is such ease of brushwork, spirit, and wealth of expression here that to admire and enjoy the piece properly one would have to own it, since the work may be said to be infinite, and the least of the angels' heads have character [...]."

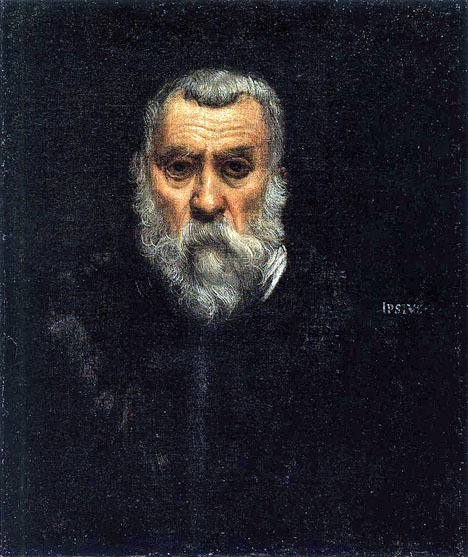

After the completion of the Paradise Tintoretto rested for a while, and he never undertook any other work of importance, though there is no reason to suppose that his energies were exhausted had his days been a little prolonged.

In 1592 he became a member of the Scuola di Mercanti.

In 1594, he was seized with severe stomach pains, complicated with fever that prevented him from sleeping and almost from eating for a fortnight. Finally, on May 31, 1594 he died. He was buried in the church of the Madonna dell'Orto by the side of his favorite daughter Marietta, who had died in 1590 at the age of thirty. Tradition suggests that as she lay in her final repose, her heart-stricken father had painted her final portrait.

Marietta had herself been a portrait-painter of considerable skill, as well as a musician, vocalist and instrumentalist, but few of her works are now traceable. It is said that up to the age of fifteen she used to accompany and assist her father at his work, dressed as a boy. Eventually, she married a jeweler, Mario Augusta. In 1866 the grave of the Vescovi and Tintoretto was opened, and the remains of nine members of the joint families were found in it. The grave was then moved to a new location, to the right of the choir.

Tintoretto had very few pupils; his two sons and Martin de Vos of Antwerp were among them. His son Domenico (1562-1637) frequently assisted his father in the groundwork of great pictures. He himself painted a multitude of works, many of them of a very large scale. At best, they would be considered mediocre and, coming from the son of Tintoretto, are exasperating. In any event, he must be regarded as a considerable pictorial practitioner in his way. There are reflections of Tintoretto to be found in the Greek painter of the Spanish Renaissance El Greco, who likely saw his works during a stay in Venice.

Tintoretto scarcely ever travelled out of Venice. He loved all the arts and as a youth played the lute and various instruments, some of them of his own invention, and designed theatrical costumes and properties. He was also versed in mechanics and mechanical devices while being a very agreeable companion. For the sake of his work, he lived in a mostly retired fashion, and even when not painting was wont to remain in his working room surrounded by casts. Here he hardly admitted any, even intimate friends, and he kept his mode of work secret, with the exception of his assistants. He abounded in pleasant witty sayings, whether to great personages or to others, but he himself seldom smiled.

Out of doors, his wife made him wear the robe of a Venetian citizen; if it rained she tried to induce him with an outer garment which he resisted. When he left the house, she would also wrap money up for him in a handkerchief, expecting a strict accounting on his return. Tintoretto's customary reply was that he had spent it on alms to the poor or to prisoners.

An agreement is extant showing a plan to finish two historical paintings, each containing twenty figures, seven being portraits in a two month period of time. The number of his portraits is enormous; their merit is unequaled, but the really fine ones cannot be surpassed. Sebastiano del Piombo remarked that Tintoretto could paint in two days as much as himself in two years; Annibale Carracci that Tintoretto was in many pictures equal to Titian, in others inferior to Tintoretto. This was the general opinion of the Venetians, who said that he had three pencils - one of gold, the second of silver and the third of iron.

A comparison of Tintoretto's final The Last Supper with Leonardo da Vinci's treatment of the same subject provides an instructive demonstration of how artistic styles evolved over the course of the Renaissance. Leonardo's is all classical repose. The disciples radiate away from Christ in almost-mathematical symmetry. In the hands of Tintoretto, the same event becomes dramatic, as the human figures are joined by angels. A servant is fore grounded, perhaps in reference to the Gospel of John 13:14-16. In the restless dynamism of his composition, his dramatic use of light, and his emphatic perspective effects, Tintoretto seems a baroque artist ahead of his time.

Paintings of Religious Subject-Matter - 1540's

The Martyrdom of the Ten Thousand (Fragment): ca 1538

_ca_1538.jpg)

This early work by Tintoretto is the lower half of a picture originally some three meters high, a copy to scale of Vittore Carpaccio's The Martyrdom of the Ten Thousand (Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice). Carpaccio's canvas was painted in 1515 to go above an altar donated by the Ottobon family in the side aisle of the Church of Sant'Antonio di Castello. It shows an entire army which converted to Christianity after a victory over rebels, and was then executed by the Persian king Sapor on Mount Ararat by order of the Roman Emperor Hadrian. As a kind of catalog of male nudes, this painting was a suitable object of study for aspiring painters of historical pictures like the young Tintoretto.

The Supper at Emmaus: 1542-43

Tintoretto began his career as one of Titian's pupils and was later much influenced by Parmigianino and Michelangelo, but his own art, dramatic and animated, passionate and visionary, kept a highly individual note that was in many respects totally original.

The Supper at Emmaus is considered by experts to have been painted in about 1540, when he was a young man. Unlike his paintings of the Last Supper - a frequent subject of his later years - this painting is a more balanced composition in the Renaissance style, with the figures arranged parallel to the picture plane. The figures are relatively large and statuesque, and there is not such effective use of contrasting light and shade or spatial arrangement as in the more mature works. It is primarily by means of gestures and vigorous poses that the painter conveys the dramatic and tense atmosphere inherent in the scene.

The Conversion of Saul: ca 1545

This large canvas shows the Conversion of Saul, formerly a persecutor of Christians and later known as Paul, when he was flung to the ground by a bright light on his way to Damascus, blinded, and addressed by the loud voice of God. Echoes of famous works by Leonardo, Raphael and Titian demonstrate the young Tintoretto's huge ambition. He is already emulating the great battle paintings of the High Renaissance.

The Conversion of Saul (Detail): ca 1545

_ca_1545.jpg)

The ambitious young Tintoretto makes the theme of the Conversion of Saul the occasion for a battle picture. He took the river landscape with horsemen galloping over a bridge and the soldiers sliding down the slope from a famous painting by Titian for which a preparatory drawing has survived. Like Leonardo's Battle of Anghiari and Michelangelo's Battle of Cascina, Titian's Battle of Spoleto was long regarded as an exemplary model for the depiction of warfare.

Christ Washing the Feet of His Disciples: ca 1547

It was long supposed that this work was executed for the Church of San Marcuola in Venice, but the copy still in the church better accords with another version of the subject now in Newcastle. However, there is no doubt about Tintoretto's autograph authorship of the Prado painting, which was almost certainly painted at about the same time.

Typical of Tintoretto throughout his career is the dramatic setting for the scene, the long diagonal vistas serving to transform the humble event into an apocalyptic vision. The coloring, however, is bright and sumptuous, the modeling firm, and the space and light clear and still - a sign of the fairly early date of the work in the artist's career.

Tintoretto copied the animal in the foreground from a painting by Jacopo Bassano.

The Miracle of Saint Augustine: ca 1549

The painting shows Saint Augustine, in his bishop's robes, appearing to forty pilgrims bound for Rome, some crippled and some blind, and pointing the way to his own tomb in Pavia with the promise of a cure. Tintoretto sets the scene in a dried-up river course. In the background of this bleak lunar landscape the façade of a church hovers as a vision of hope. Tintoretto painted the picture for the altar of the Porto Godi Family in the chapel of Saint Augustine at San Michele in Vicenza (the church no longer stands). In the middle ground of the picture, below the church tower on the right, a portrait of the white-bearded donor in miniature can be seen.

The Visitation (Detail): ca 1549

_ca_1549.jpg)

After the Angel Gabriel had announced the coming birth of Christ to Mary she visited Elisabeth, who was pregnant herself with John the Baptist. The movement of her own child in the womb told Elisabeth that the future mother of God stood before her. Her first words of greeting, a confirmation to Mary of the Annunciation itself, are inscribed on the rocky plinth at her feet: "Blessed art thou among women." Similarly, the opening words of the Magnificat, Mary's song of praise, are inscribed at her own feet: "My soul doth magnify the Lord." To leave space for the resonance of these words, Tintoretto does not depict Mary and Elisabeth embracing or exchanging the kiss of peace, but greeting each other from a distance.

Saints Helen and Barbara Adoring the Cross

The painting, originally in the church of Santa Croce in Milan, represents Saints Helen, Barbara, Andrew and Macario, another saint and the donor.

Saint Nicholas

The painting probably was part of a larger painting.

Paintings of Religious Subject-Matter - 1550's

Christ and the Woman Taken in Adultery: ca 1550

This painting was described by Ridolfi in 1642 in his biography of Tintoretto. Ridolfi writes that the picture "is painted of the adulteress at the moment when Our Lord writes the letters in the dirt with his hand, and the Scribes and Pharisees depart, one after the other, concealing themselves among the columns of a portico that is represented with the most rare perspective skill; and it is a picture filled with much erudition". The pictorial erudition that so struck Ridolfi is demonstrated in the perspective structure, yet Tintoretto did not achieve this effortlessly: x-rays have revealed errors and redrawing in the lines of the architecture, above all in the patterning of the pavement. There is a strong centrifugal movement to the scene, and its quality of space extended by light seems to prefigure the artist's trilogy of paintings of the life of Saint Mark.

In his painting of the encounter of Christ and the Woman Taken in Adultery, Tintoretto provides a literal depiction of the biblical account (in John 8: 1 -11): the adulteress stands "in the midst" before Christ, who is seated in the temple preaching, and his disciples; on the right, the scribes and Pharisees are leaving the scene of their defeat, "beginning with the eldest, even unto the last." Christ's judgment frees the woman from the power other accusers: "He that is without sin among you, let him first cast a stone at her."

The prevailing opinion of the critics places this painting in the years between 1545 and 1550. The painting belongs to a group of works of medium size and similar format which treat the theme of Christ and the woman taken in adultery in various ways. The best known of these, along with the canvas in Rome, is the version at the Rijskmuseum in Amsterdam.

Saint Jerome and Saint Andrew: ca 1552

The works of Tintoretto after the middle of the 16th century demonstrate still more clearly the search for strong sculptural effects achieved by use of chiaroscuro, a complex scenographic spatial representation and the use of clear, bright color in direct contrast to the more subdued harmonies of Titian's 'magica alchimia cromatica'. The work 'Saint Jerome and Saint Andrew' is a major example of these tendencies. It was commissioned for one of the rooms of the Magistrato del Sale in the Palazzo dei Camerlenghi at Rialto by Andrea Dandolo and Girolamo Bernardo, magistrates who left office between September and October 1552.

The search for a Manneristic figural rhythm within the overall compositional plan is evident. The figure of Saint Andrew takes up the whole of the small space to the left of the cross, leaving more room for Saint Jerome alongside the curvilinear outline of the rock. The scenic effect of the figures constrained in a small space is given unity and the poetic sense of an intense spiritual life by the expressive force of light which brings out all the gradations of color.

Saint Louis, Saint George, and the Princess: ca 1553

This work, commissioned by Giorgio Venier and Alvise Foscarini who left the Magistratura del Sale respectively on September 13th 1551 and May 10th 1553, is a fine example of Tintoretto's achievement of a dynamic compositional tension. The incisive force of the line combines with rich and luminous color to create the firmly modeled figures. The self-conscious statement of dramatic style became another pretext for the continuing polemic between Tintoretto and Titian. Dolce clearly alludes to it when, in his 'Dialogo della pittura' of 1558, he criticizes the unfortunate position of the princess, whom he takes to be St. Margaret, astride the dragon.

The Birth of Saint John the Baptist: ca 1540

The Archangel Gabriel announced to Zacharias that his wife Elizabeth, already advanced in years and considered infertile, would bear him a son, and when Zacharias doubted the angel he was struck dumb. Tintoretto shows Zacharias (on the right of the picture) recovering his power of speech and breaking into a song of praise to the Lord.

Tintoretto, a painter of the late Renaissance, transferred the evangelical birth of John the Baptist into the contemporary context of a rich 16th century Venetian household.

The Birth of Saint John the Baptist (Detail): ca 1540

A painter of the late Renaissance, Tinoretto, transferred the evangelical birth of John the Baptist into the contemporary context of a rich 16th century Venetian household.

The Assumption: 1555

The painting comes from the now demolished church of the Crociferi. According to the sources, this color-rich composition was deliberately painted in the style of Veronese, the artist the donors originally chose.

Christ and the Adulteress: ca 1555

This version of the subject was executed by the workshop of Tintoretto.

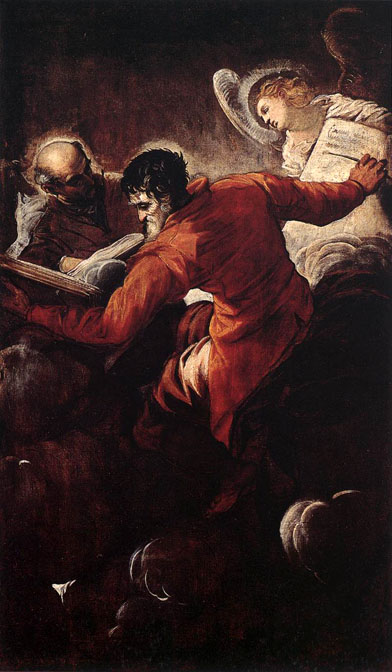

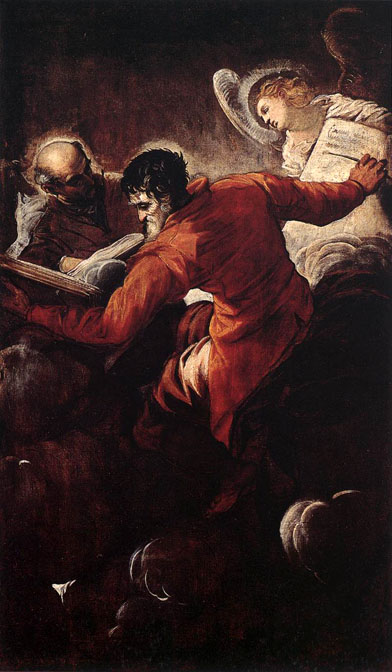

The Evangelists Mark and John: 1557

Like its counterpart, the Evangelists Luke and Matthew, this painting can almost be described as brunaille (painting in brown on brown). Where the hem of Saint Mark's garment hangs down, it can be seen that Tintoretto left large areas of the dark ground as it was; he had to paint the picture and deliver it ready for installation within a very short time.

These two paintings adorned the inner sides of two organ wings, and were therefore visible when the organ was being played. Tintoretto ingeniously refers to this by showing all four Evangelists turning as they sit on their clouds to listen to the organ. Its sound is therefore equated with the music of heaven and the source of scriptural inspiration.

The Evangelists Luke and Matthew: 1557

Like its counterpart, the Evangelists Mark and John, this painting can almost be described as brunaille (painting in brown on brown).

These two paintings adorned the inner sides of two organ wings, and were therefore visible when the organ was being played. Tintoretto ingeniously refers to this by showing all four Evangelists turning as they sit on their clouds to listen to the organ. Its sound is therefore equated with the music of heaven and the source of scriptural inspiration.

Saint George and the Dragon: 1555-58

Saint George and the Dragon is a small, even miniature, painting in the context of Tintoretto's work, detailed and highly finished. It was probably commissioned as a private altarpiece, and the conventional arched vertical format had never before, and has rarely since, been used to such dynamic and disturbing effect. The imagery also is unusual. The story of Saint George of Cappadocia, Roman officer and Christian martyr, was made popular in Western Europe through The Golden Legend, a calendar-book of tales of the lives of the saints compiled in the late thirteenth century. It is there that we find the story of a dragon terrorizing the countryside demanding human sacrifice. When the fatal lot fell to Cleodolinda, the daughter of the king, Saint George, riding by on his charger, turned to help her and vanquished the dragon 'in the name of Christ'. In a departure from tradition, Tintoretto has shown the livid cadaver of a previous victim in the pose of the crucified Christ and included God the Father in the heavens blessing the victory of good over evil. The terrified princess, fleeing uphill from the dragon climbing out of the sea, nearly stumbles out of the foreground. Saint George has galloped into the painting from our right, the direction of a hidden source of light which picks out the trunks of the trees, the rump of the horse, the armor of the knight and the flesh and garments of Cleodolinda.

The Deposition: 1557-59

This painting was probably commissioned for an altar in a private chapel. Tintoretto painted several variants of the theme of the Deposition, this canvas is a particularly moving representation of the subject.

Paintings of Religious Subject-Matter - 1560's

Lamentation over the Dead Christ: ca 1560