1475 - 1564

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni (March 6, 1475 - February 18, 1564), commonly known as Michelangelo, was an Italian Renaissance painter, sculptor, architect, poet and engineer. Despite making few forays beyond the arts, his versatility in the disciplines he took up was of such a high order that he is often considered a contender for the title of Renaissance man, along with his rival and fellow Italian Leonardo da Vinci.

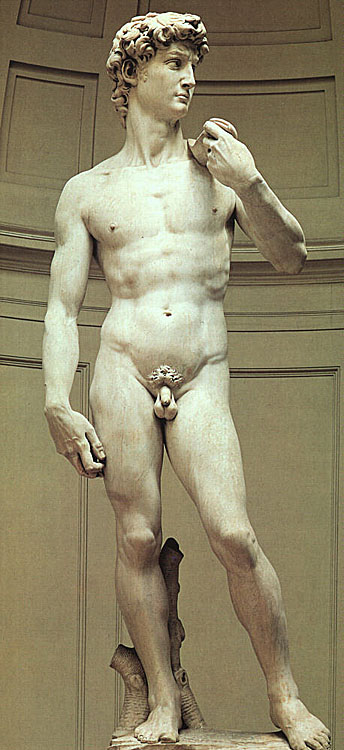

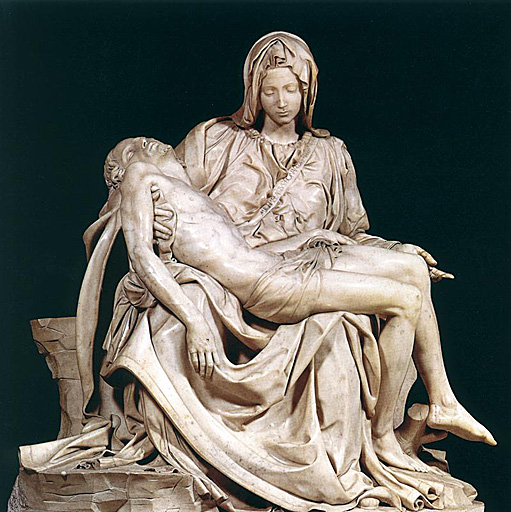

Michelangelo's output in every field during his long life was prodigious; when the sheer volume of correspondence, sketches and reminiscences that survive is also taken into account; he is the best-documented artist of the 16th century. Two of his best-known works, the Pieta and the David, were sculpted before he turned thirty. Despite his low opinion of painting, Michelangelo also created two of the most influential works in fresco in the history of Western art: the scenes from Genesis on the ceiling and The Last Judgment on the altar wall of the Sistine Chapel in Rome. Later in life he designed the dome of Saint Peter's Basilica in the same city and revolutionized classical architecture with his use of the giant order of pilasters.

In a demonstration of Michelangelo's unique standing, two biographies were published of him during his lifetime. One of them, by Giorgio Vasari, proposed that he was the pinnacle of all artistic achievement since the beginning of the Renaissance, a viewpoint that continued to have currency in art history for centuries. In his lifetime he was also often called Il Divino ("the divine one"). One of the qualities most admired by his contemporaries was his terribilita, a sense of awe-inspiring grandeur, and it was the attempts of subsequent artists to imitate Michelangelo's impassioned and highly personal style that resulted in the next major movement in Western art after the High Renaissance, Mannerism.

Michelangelo returned to Florence in 1499-1501. Things were changing in the city after the fall of Savonarola and the rise of the gonfaloniere Pier Soderini. He was asked by the consuls of the Guild of Wool to complete an unfinished project begun 40 years earlier by Agostino di Duccio: a colossal statue portraying David as a symbol of Florentine freedom, to be placed in the Piazza della Signoria, in front of the Palazzo Vecchio. Michelangelo responded by completing his most famous work, David in 1504. This masterwork, created out of marble from the quarries at Carrara, definitively established his prominence as a sculptor of extraordinary technical skill and strength of symbolic imagination.

Also during this period, Michelangelo painted the Holy Family and St John, also known as the Doni Tondo or the Holy Family of the Tribune: it was commissioned for the marriage of Angelo Doni and Maddalena Strozzi and in the 17th Century hung in the room known as the Tribune in the Uffizi. He also may have painted the Madonna and Child with John the Baptist, known as the Manchester Madonna and now in the National Gallery, London.

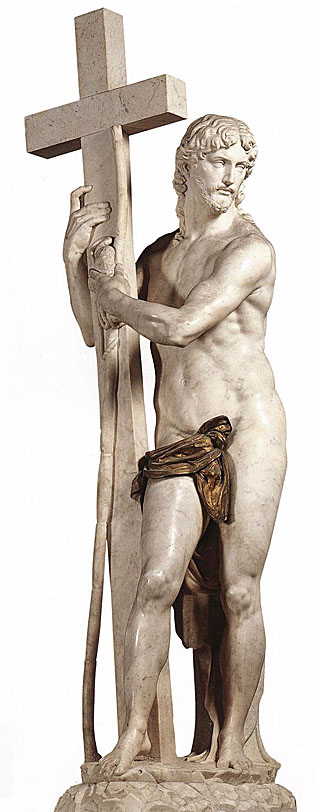

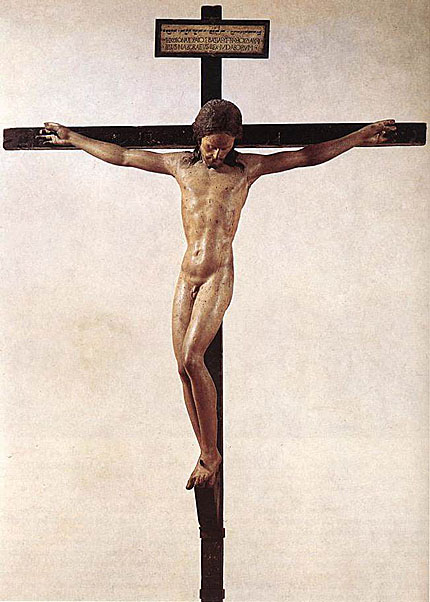

The work was commissioned in June 1514, by the Roman patrician Metello Vari, who stipulated only that the nude standing figure would have the Cross in his arms, but left the composition entirely to Michelangelo. Michelangelo was working on a first version of this statue in his shop in Macello dei Corvi around 1515, but abandoned it in roughed-out condition when he discovered a black vein in the white marble, remarked upon by Vari in a letter, and later by Ulisse Aldrovandini. A new version was hurriedly substituted in 1519-1520 to fulfill the terms of the contract. Michelangelo worked on it in Florence, and the move to Rome and final touches were entrusted to an apprentice, Pietro Urbano: the latter, however, damaged the work and had to be quickly replaced by Federico Frizzi after a suggestion from Sebastiano del Piombo.

The first version, rough as it was, was asked for by Metello Vari, and given him in January 1522, for the little garden courtyard of his palazzetto near Santa Maria sopra Minerva, come suo grandissimo onore, come fosse d'oro. There it remained, described by Ulisse Aldrovandi in 1556, and noted in some contemporary letters as apparently for sale in 1607, following which it was utterly lost to sight. In 2000 Irene Baldriga recognized the lost first version, extensively reworked in the seventeenth century, in the sacristy of the church of San Vincenzo Martire, at Basso Romano near Viterbo; the black vein is clearly distinguishable on Christ's left cheek.

Despite all these problems, the second version impressed the contemporaries. Sebastiano del Piombo declared that the knees alone were worthy of more than the whole Rome, "in one of the most curious praises ever sung about a work of art," William Wallace remarked, in reappraising the contemporary praise and modern distaste for one of the least favored works of Michelangelo.

Michelangelo's most individual contribution is the figure of St Paul; the intensity of his look and the way he clasps his garment can be seen as a study anticipating the Moses on Julius II's tomb. And the same time it is also clear how far the artist still had to go to reach that stage.

One must take these words of Vasari about the "divine beauty" of the work in the most literal sense, in order to understand the meaning of this composition. Michelangelo convinces both himself and us of the divine quality and the significance of these figures by means of earthly beauty, perfect by human standards and therefore divine. We are here face to face not only with pain as a condition of redemption, but rather with absolute beauty as one of its consequences.

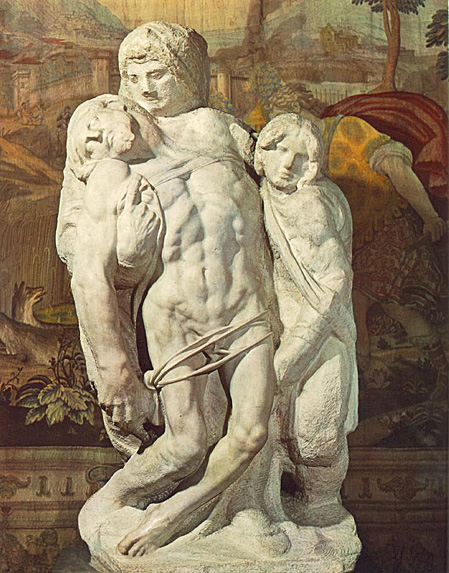

Michelangelo' last sculptures were two (or three if the Pieta Palestrina is his work) Pietas. Some of them were probably planned to decorate his tomb. According to Vasari, the artist's wish was to be buried in Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome, at the feet of the Pietà on which he had worked between 1547 and 1553; this was before he smashed it in 1555, because one leg had broken off and because the block of marble was defective. This is the Pieta, which is now in Florence Cathedral Museum. After having broken the statue, he let his servant take the pieces. Later the servant sold them and the new owner had it reconstructed following Michelangelo's models, so that the work has been preserved.

Michelangelo, in this Pieta, did not portray any precise historical moment; instead he erected a personal admonishment to himself, "One does not think how much blood it costs." He had once written this line from the Divine Comedy on a drawing for a Pieta, and from the composition of this drawing he took this marble group. Nicodemus has taken the place of the Madonna and she, with Mary Magdalen now does what the angels did, supports the body. There is no longer only the mother, but three people are now surrounding the body, and Christ's deadness is expressed more effectively by the falling movement in which he is caught halfway. The figures are not isolated from the emaciated dead body: they are blended, in their fear, desperation and pain, into a single setting. The bodies are denied any independent power and there is nothing to point to a higher meaning of this suffering, such as redemption.

_1552_64.jpg)

More than half a century separates this work from the Pieta in San Pietro, half a century of artistic evolution are here recognizable in their extreme poles. But this also marks the development undergone by the whole European culture: from the Renaissance, from the revival of Antiquity and the rediscovery of nature, to the splitting up of the Christian Church, the return of faith after the Counter Reformation and the Manneristic art of an El Greco. Only the figures of this Spanish artist, glowing signs of faith, can in some way be compared to the work which Michelangelo fashioned up to six days before his death: the Pieta Rondanini.

According to Vasari, he had already begun to work on it in 1555, before smashing the Florentine Pieta. He destroyed the first version of this, too, as can be seen in the second face of Christ in the final version. This version, still unfinished at the sartist's death, was probably begun not much later then 1555. The unity between Mother and Son is even more intimate. It is almost impossible to tell whether it is the Mother supporting the Son, or the Son supporting the Mother, overcome by despair. Both are in need of help, and both hold themselves up in the act of invocation and lament before the world and God.

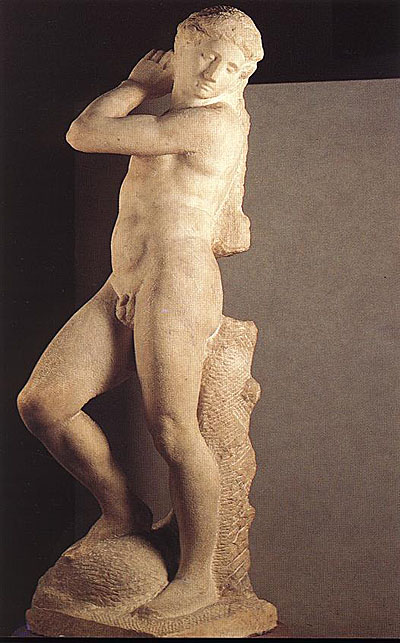

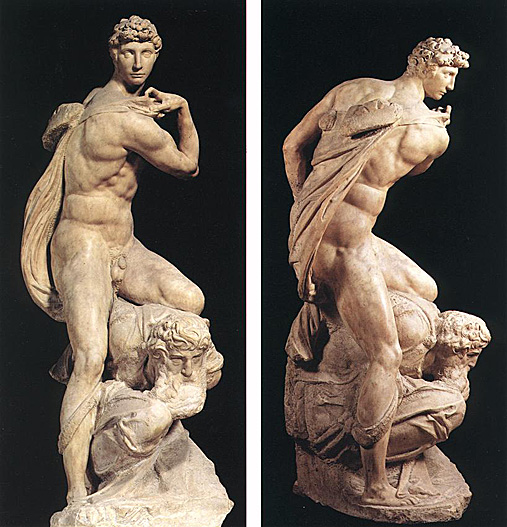

The statue was commissioned by the hated Papal Governor of Florence, Baccio Valori. Michelangelo used a pragmatic and political approach. This figure has had its double name for a long time, since it was not certain whether it was a representation of the Old Testament hero David or the Greek God of Art, Apollo. But in the round rock under the youth's foot one can probably recognize the head of Goliath: so once again Michelangelo has created a David.

There is a blatant difference between this figure and the one which in 1504 rose to the position of the most powerful symbol of the Republic. In the place of Strength and Wrath, we have Melancholy, almost Regret. The victorious hero no longer celebrates his triumph; the blood that has been shed seems to have shown him the meaning of his actions and of its consequences. Michelangelo could not have admonished Baccio Valori in a deeper, more meaningful and yet more respectful way.

The statue of Bacchus was commissioned by the banker Jacopo Galli for his garden and he wanted it fashioned after the models of the ancients. The body of this drunken and staggering god gives an impression of both youthfulness and of femininity. Vasari says that this strange blending of effects is the characteristic of the Greek god Dionysus. But in Michelangelo's experience, sensuality of such a divine nature has a drawback for man: in his left hand the god holds with indifference a lionsksin, the symbol of death, and a bunch of grapes, the symbol of life, from which a Faun is feeding. Thus we are brought to realize, in a sudden way, what significance this miracle of pure sensuality has for man: living only for a short while he will find himself in the position of the faun, caught in the grasp of death, the lionskin.

The statue was transferred to Florence in 1572.

_1504.jpg)

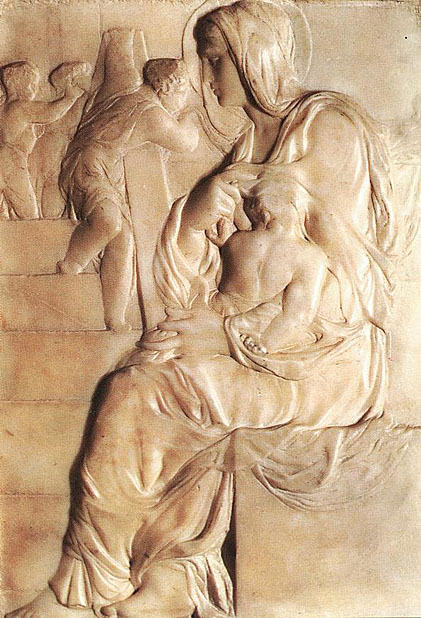

This is the earliest extant work of Michelangelo. The waxy, translucent slab, like alabaster, is reminiscent of Desiderio. Carved in "rilievo schiacciato" it represents Michelangelo's exploration of quattrocento techniques. In both form and content we see the influence of Greek "stelai". The Madonna's face is in classical profile and she sits on a square block, Michelangelo's hallmark. He chose not to show the Child's face but placed him in an odd position, either nursing or sleeping and encased in drapery, suggesting protection. In the background, four youths handle a long cloth, identified either the one used to lower Christ from the cross or a shroud. Altogether the relief is much closer to Donatello's Pazzi Madonna then the intervening lyrical madonnas by Rossellino and Desiderio.

The statue of Madonna and Child are located in the Medici Chapel above the simple tomb of "Magnifici". In the figures of the Madonna and Child there is but little human contact, despite their physical closeness: the most glorious of women is moved by the Child in the same way as by the contemplation of the highest Platonic thought, and this seems to transpire from her face.

Flanked by St Cosimo and St Damian, the Virgin forms the spiritual centre of the Medici Chapel; the eyes of Lorenzo and Giuliano de' Medici are turned towards her. Like the first Madonna carved by Michelangelo (a relief in the Casa Buonarroti, Florence), she is suckling her child, who clings to her strongly. The dynamic interlocking spirals in space of the two figures suggest a different order of movement than that visible in the other figures, and it has been suggested that the group was originally intended for one of the earlier versions of the tomb of Julius II, and was later employed in the Medici Chapel.

In architecture, detail is everything: the curves and outlines of the almost rhomboid cupola surpass all other silhouettes of its kind, even that of Brunelleschi's cupola for the Duomo in Florence and those of the great mosques of Istanbul and Cairo. If one views the dome of Saint Peter's from the south or west, whence the weaknesses of later architects are not apparent, its impact, the testament of the aged Michelangelo, makes one wonder what the secret of this dome can be. Theoretically, it should not have been difficult to design. In fact only one man was capable of devising it, and granted the inspiration to carry it out. In harmonizing elements which are eternally and fundamentally opposed, his genius drew upon the accumulated wisdom of his life. The pointed cupola reveals the mystery of the universe; the miracle of reconciliation between God and man. Shining above the Eternal City, the silver-grey dome radiates love.

Michelangelo projected a dome in a slightly pointed form, and this was the shape adopted by the builders. As with Brunelleschi's Florence dome, the pointed shape exerts less thrust, and it was this which was decisive when, between 1585 and 1590, it was built by Giacomo della Porta with the assistance of Domenico Fontana, who was probably the best engineer of the day.

The dome, finished after Michelangelo's death, became the largest in the world. The central aisle has been spoilt by a nave and a facade whose cold secularity is redeemed solely by Bernini's magnificent colonnades. One must see Michelangelo's Saint Peter's from the west side to appreciate what was intended here; likewise one should cross the nave and, disregarding the bronze canopy and all later Baroque additions, look at the cruciform transepts and up towards the vaulted cupola.

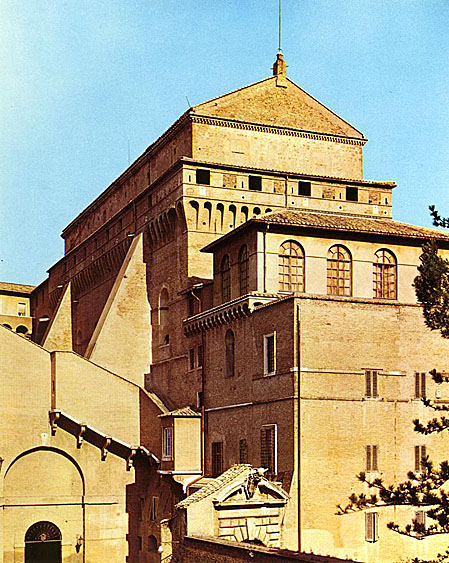

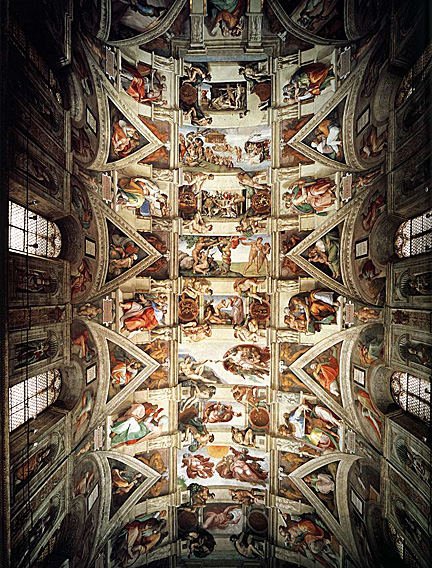

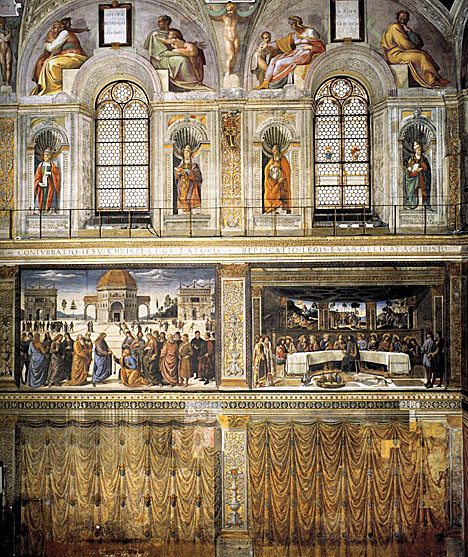

Built between 1475 and 1483, in the time of Pope Sixtus IV della Rovere, the Sistine Chapel has originally served as Palatine Chapel. The Chapel is rectangular in shape and measures 40,93 meters long by 13,41 meters wide, i.e. the exact dimensions of the Temple of Solomon, as given in the Old Testament.

The architectural plans were made by Baccio Pontelli and the construction was supervised by Giovanino de'Dolci.

The chapel was built between 1475 and 1483, in the time of Pope Sixtus IV della Rovere. A basic feature of the chapel itself, so obvious that it is sometimes ignored, is the papal function, as the pope's chapel and the location of the elections of new popes. Furthermore, the building was in some respects a personal monument to the Della Rovere family, since Sixtus IV saw to its actual construction and the frescoes beneath the vaults, and his nephew Julius II commissioned the ceiling decoration. Oak leaves and acorns abound, heraldic symbols of the family whose name means literally "from the oak."

The Chapel is rectangular in shape and measures 40,93 meters long by 13,41 meters wide, i.e. the exact dimensions of the Temple of Solomon, as given in the Old Testament. It is 20,70 meters high and is surmounted by a shallow barrel vault with six tall windows cut into the long sides, forming a series of pendentives between them. A marble mosaic floor of exquisite workmanship describes the processional itinerary up to and beyond the marble screen, to the innermost space, where it offers a surround for the papal throne and the cardinals' seats. The architectural plans were made by Baccio Pontelli and the construction was supervised by Giovanino de'Dolci.

The walls are divided into three orders by horizontal cornices; according to the decorative program, the lower of the three orders was to be painted with fictive "tapestries," the central one with two facing cycles - one relating the life of Moses (left wall) and the other the Life of Christ (right wall), starting from the end wall, where the altar fresco, painted by Perugino, depicted the Virgin of the Assumption, to whom the chapel was dedicated. The upper order is endowed with pilasters that support the pendentives of the vault. Above the upper cornice are situated the lunettes. Between each window below the lunettes, in fictive niches, run images of the first popes - from Peter to Marcellus - who practiced their ministry in times of great persecution and were martyred.

The wall paintings were executed by Pietro Perugino, Sandro Botticelli, Domenico Ghirlandaio, Cosimo Rosselli, Luca Signorelli and their respective workshops, which included Pinturicchio, Piero di Cosimo and Bartolomeo della Gatta. The ceiling was frescoed by Piero Matteo d'Amelia with a star-spangled sky.

Michelangelo was commissioned by Pope Julius II della Rovere in 1508 to repaint the ceiling; the work was completed between 1508 and 1512. He painted the Last Judgement over the altar, between 1535 and 1541, being commissioned by Pope Paul III Farnese.

The chapel was built between 1475 and 1483, in the time of Pope Sixtus IV della Rovere. A basic feature of the chapel itself, so obvious that it is sometimes ignored, is the papal function, as the pope's chapel and the location of the elections of new popes. Furthermore, the building was in some respects a personal monument to the Della Rovere family, since Sixtus IV saw to its actual construction and the frescoes beneath the vaults, and his nephew Julius II commissioned the ceiling decoration. Oak leaves and acorns abound, heraldic symbols of the family whose name means literally "from the oak."

The Chapel is rectangular in shape and measures 40,93 meters long by 13,41 meters wide, i.e. the exact dimensions of the Temple of Solomon, as given in the Old Testament. It is 20,70 meters high and is surmounted by a shallow barrel vault with six tall windows cut into the long sides, forming a series of pendentives between them. A marble mosaic floor of exquisite workmanship describes the processional itinerary up to and beyond the marble screen, to the innermost space, where it offers a surround for the papal throne and the cardinals' seats. The architectural plans were made by Baccio Pontelli and the construction was supervised by Giovanino de'Dolci.

The walls are divided into three orders by horizontal cornices; according to the decorative program, the lower of the three orders was to be painted with fictive "tapestries," the central one with two facing cycles - one relating the life of Moses (left wall) and the other the Life of Christ (right wall), starting from the end wall, where the altar fresco, painted by Perugino, depicted the Virgin of the Assumption, to whom the chapel was dedicated. The upper order is endowed with pilasters that support the pendentives of the vault. Above the upper cornice are situated the lunettes. Between each window below the lunettes, in fictive niches, run images of the first popes - from Peter to Marcellus - who practiced their ministry in times of great persecution and were martyred.

The wall paintings were executed by Pietro Perugino, Sandro Botticelli, Domenico Ghirlandaio, Cosimo Rosselli, Luca Signorelli and their respective workshops, which included Pinturicchio, Piero di Cosimo and Bartolomeo della Gatta. The ceiling was frescoed by Piero Matteo d'Amelia with a star-spangled sky.

Michelangelo was commissioned by Pope Julius II della Rovere in 1508 to repaint the ceiling; the work was completed between 1508 and 1512. He painted the Last Judgement over the altar, between 1535 and 1541, being commissioned by Pope Paul III Farnese.

According to the original decorative program (1475-83), the walls are divided into three orders by horizontal cornices; the lower of the three orders was to be painted with fictive "tapestries," the central one with two facing cycles - one relating the life of Moses (left wall) and the other the Life of Christ (right wall), starting from the end wall, where the altar fresco, painted by Perugino, depicted the Virgin of the Assumption, to whom the chapel was dedicated. The upper order is endowed with pilasters that support the pendentives of the vault. Above the upper cornice are situated the lunettes. Between each window below the lunettes, in fictive niches, run images of the first popes - from Peter to Marcellus - who practiced their ministry in times of great persecution and were martyred.

Michelangelo later (1508-12) frescoed the ceiling with the pendentives, and the lunettes. After Michelangelo painted the ceiling, it was radically different in appearance from the chapel Sixtus IV had rebuilt and decorated. The artist did not overlook any element - beginning with a remarkable use of colour - that could harmonize his frescoes with those of the fifteenth-century decorative cycle, especially the figures of the popes in the niches between the windows, immediately below the lunettes. The visitor's attention is at once attracted by the great power of the whole composition of the ceiling and the tremendous energy of the individual figures.

This is a reconstruction of the interior of the Sistine Chapel in the days of Sixtus IV, before Michelangelo's alterations to the ceiling, showing its former decoration of star-spangled frescoes by Pier Matteo d'Amelia. The chamber is better lit and afford a more coherently enclosed volume, the walls having a concerted rhythm of division via cornices and pilasters. The 'cancellata' can be seen in its earlier place, before being moved closer to the entrance to leave more room for the 'papal chapel'

In planning the architectural design Michelangelo first had to accommodate his program to the pre-existing building, including the windows, which were the source of light for his decoration. The wreath of openings still provides the principal viewing light.

Michelangelo devised a long central area framed by a fictive marble cornice and separated into nine sections by broad pilaster strips bent across the ceiling, also in imitation white marble. Sections of alternating dimensions are framed between wider and narrower bands. Within them Michelangelo varied the size of the actual narratives, giving only the smaller ones a marble frame. Four ignudi (male nudes), among the most admired elements of the ceiling, ostensibly support ribbons attached to large medallions painted to look like bronze. Twenty in all, they are in different poses, producing, together with the Prophets and Sibyls, a "handbook" of alternatives for the seated figure for later artists.

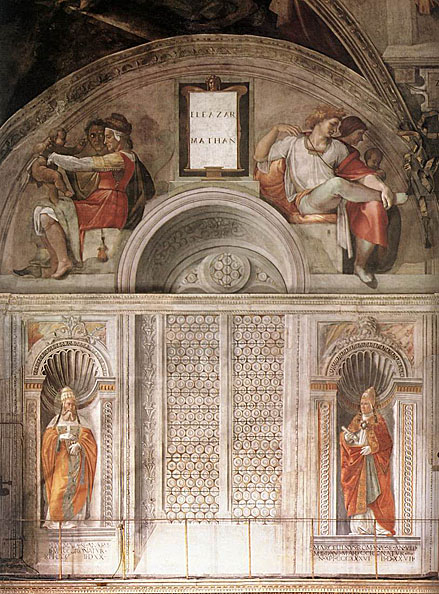

At the corners of the ceiling Michelangelo has painted four salvation subjects, including David and Goliath and Judith and Holofernes. Triangular-shaped compartments are repeated in a continuous band along the entire border of the ceiling; they contain bronze-colored nudes that alternate with the renowned Prophets and Sibyls set into marble thrones which, in turn, have paired marble putti in a variety of poses and positions that expand upon the tradition of Donatello and Luca della Robbia. The ancestors of Christ are painted on the flat side walls, the only section of the decoration that did not require the visual adjustments posed by painting on a curved surface.

In planning the architectural design Michelangelo first had to accommodate his program to the pre-existing building, including the windows, which were the source of light for his decoration. The wreath of openings still provides the principal viewing light.

Michelangelo devised a long central area framed by a fictive marble cornice and separated into nine sections by broad pilaster strips bent across the ceiling, also in imitation white marble. Sections of alternating dimensions are framed between wider and narrower bands. Within them Michelangelo varied the size of the actual narratives, giving only the smaller ones a marble frame. Four ignudi (male nudes), among the most admired elements of the ceiling, ostensibly support ribbons attached to large medallions painted to look like bronze. Twenty in all, they are in different poses, producing, together with the Prophets and Sibyls, a "handbook" of alternatives for the seated figure for later artists.

At the corners of the ceiling Michelangelo has painted four salvation subjects, including David and Goliath and Judith and Holofernes. Triangular-shaped compartments are repeated in a continuous band along the entire border of the ceiling; they contain bronze-colored nudes that alternate with the renowned Prophets and Sibyls set into marble thrones which, in turn, have paired marble putti in a variety of poses and positions that expand upon the tradition of Donatello and Luca della Robbia. The ancestors of Christ are painted on the flat side walls, the only section of the decoration that did not require the visual adjustments posed by painting on a curved surface.

In the scheme of divisions, the key elements are the thrones of the seers flanked by plinths and colonnettes decorated with pairs of putti supporting the cornice running above the crowns of the spandrels, at about a third of the way across the curve of the vault. Beyond the cornice, the vertical frames flanking the thrones are prolonged as the arches crossing the vault. They divide it into nine compartments in which the stories of Genesis - from the Separation of Light from Darkness to the Drunkenness of Noah - are represented as if they were seen above the space of the chapel, beyond and through the imposing structure of the painted architecture.

In the five compartments above the thrones, the field of the narrative scenes is limited in size by the presence of four figures of ignudi, sitting on plinths and bearing garlands of oak leaves and acorns, and of two medallions painted to resemble bronze, with episodes drawn from the books of Genesis, Samuel, Kings, and Maccabees.

Lastly, under the cornice and the thrones, in the spandrels and the lunettes at the tops of the walls, are depicted the forty generations of the Ancestors of Christ, from Abraham to Joseph, while the corner pendentives contain representations of biblical scenes associated with the theme of the divine protection of the Jews: Judith and Holofernes, David and Goliath, the Brazen Serpent, and the Punishment of Haman.

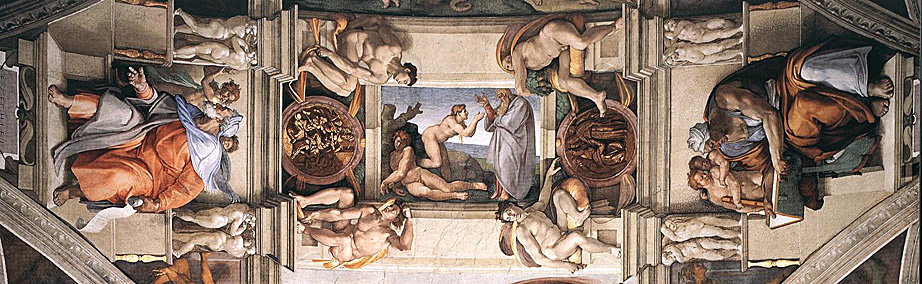

The picture shows a transversal section of the ceiling with a smaller field of the apex of the ceiling. It demonstrates the following design elements:

Thrones for the Prophets and Sibyls;

One of the seven Prophets (Ezekiel), one of the five Sibyls (Cumaean);

Two of the twenty-four square pedestals forming niches for the Prophets and Sibyls and surmounted by twin 'putti' (a boy and a girl) in relief;

Two small angels as a background to the enthroned figures;

Two of the ten white angular cornices joining the capitals of the putti-pilasters;

Four of the twenty 'ignudi' occupying the cornices, holding cornucopias, ribbons and garlands of fruit;

Two of the ten gold medallions in reliefs depicting scenes from the Book of Kings and supported by two ignudi;

One of the five smaller fields of the apex of the ceiling guarded by four ignudi and covered by a scene from the Genesis (The Creation of Eve).

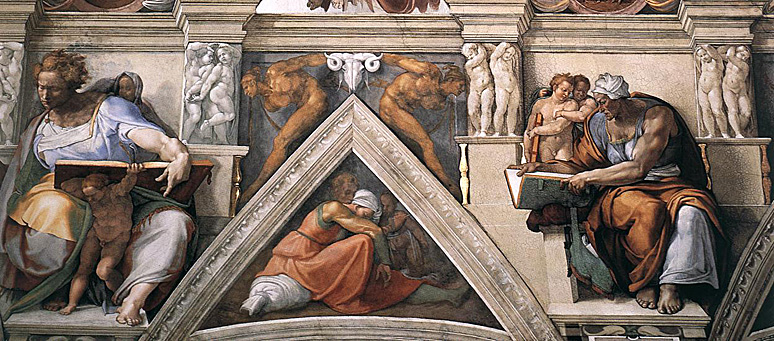

The picture shows a transversal section of the ceiling with a larger field of the apex of the ceiling. It demonstrates the following additional design elements:

Two of the eight spheric triangles above the lunettes, with frescoes depicting the ancestors of Christ;

Four of the twenty-four bronze nudes flanking ram heads at the triangles and spandrels;

One of the four larger fields of the apex containig a scene from the Genesis (The Creation of Adam).

The picture shows a longitudinal section of the ceiling between a Prophet and a Sibyl. It demonstrates the following design elements:

Thrones for the Prophets and Sibyls;

One of the seven Prophets (Daniel), one of the five Sibyls (Cumaean);

Three of the twenty-four square pedestals forming niches for the Prophets and Sibyls and surmounted by twin 'putti' (a boy and a girl) in relief;

Two small angels as a background to the enthroned figures;

Two of the twenty-four bronze nudes flanking ram heads at the triangles and spandrels;

One of the eight spheric triangles above the lunettes, with frescoes depicting the ancestors of Christ.

If Ezekiel saw the beginning and the origin of creation, the first emanation of the Godhead, the youthful Titan Daniel knows of ultimate things and of the Judgement which Michelangelo was to paint much later above the altar of the Sistine Chapel. Assisted by his genius half hidden in his lilac mantle, the man who lived unharmed in a lion's den silently sets down in the Book of Life what he has seen. The seer's hand with the foreshortened arm expresses quiet dedication to his task. And it should be said here that Michelangelo's vaunted foreshortening perspectives were never feats of artistic bravado, as was the case with his countless imitators, but always met a psychological necessity or expressed some truth; they are therefore aesthetically satisfying, never grotesque as so often in Baroque art.

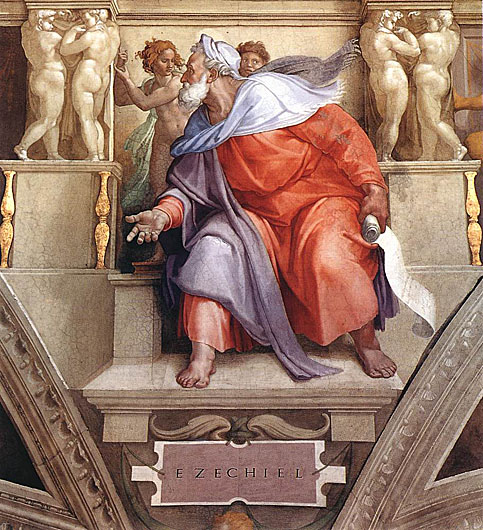

Ezekiel, the Prophet of the Merkabah, the divine throne and chariot of fire, the heavenly hierarchy and the four cherubim, is shown contorted by his vision. His expressive Hebrew profile faces Zechariah to the left. There is surely some meaning in the fact that this Prophet's head is wrapped in a white turban; holy dread is written on his countenance - the brightness of the vision might have blinded him. The other Prophets are bareheaded, while the Sibyls, like the young Delphica and the old Persica, closer to earth, are veiled or shrouded so as to protect them from an excess of light. The movement of the Prophet's right hand indicates three things: surprise, self surrender, and the imparting of his vision. Michelangelo thus succeeded by sheer, direct simplicity, in endowing a simple gesture with manifold meaning. The contrast of Ezekiel's sombre, heavy garment painted in brown and lilac makes his rapture all the more poignant. The wind of the spirit brushes the fringes on his shoulder. The earth-sprite behind the old man looks terrified, while the beautiful and angelic boy beside him points heavenward with a gesture reminding us of Leonardo's 'John the Baptist' and his 'Bacchus'; late works which Michelangelo may not have seen. But great men who are ahead of their time often express some new idea simultaneously.

Isaiah is altogether different in character. He seems to listen intently. His forehead may express bewilderment yet he is clad in the green cloak of hope. As he listens, his genii point excitedly into the distance whence the great voice addresses him. The powerful left arm is raised as though commanding stillness or silence. He has an intimation of the mystery of the Son. The naked feet are crossed, and the entire figure expresses veneration, expectation and readiness. What is the significance of the half closed book which he marks with his inserted finger? Surely, that the book is nothing; books may fail, the voice alone is infallible. Note how the contours of the figure form a circle from which only the head and one hand emerge. The left arm, the left hand, and the head together with the genii, describe an oval superimposed on the circle. The face, with lips parted in expectation, bears an expression of rapt attention; the hair of indeterminate colour, and the vigorously drawn neck emerging from light-toned draperies in blue, green and red, symbolizing faith, hope and charity, indicate that this exalted figure is poised on the threshold of two worlds; it is intent of hearing, it is rapt in attention, and its genius points at Noah's offering.

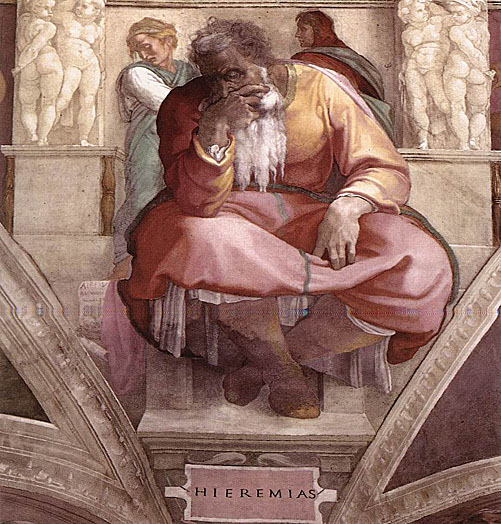

The melancholy, abstracted Jeremiah, more than any other figure, is a deeply moving moral self portrait. Sorrowful unto death, he rests from his spiritual vision, to reflect on the hardship and frustration of earthly existence. We share the artist's pity for this noble being, prematurely aged and steeped in the anguish of the universe who, alone among the Prophets, must carry the weight of earthly existence. His hand grasps his beard with a saturnine gesture that seems to be second nature to him. The genii of Jeremiah are the strangest of the whole series. The one to the left is feminine and, as it were, an image of the Prophet's afflicted soul, painfully conscious of the absence of pure goodness and beauty on the earthly plane, unless it be in art; and even that was all too often suspect to the zealous among Christian and Jewish communities where iconoclasm was forever lurking in the dark recesses of the mind. In short, the genius is a symbol of Platonism defeated in Michelangelo's youth by Savonarola. Platonism itself found expression in the most sublime among the ignudi on the Prophet's left. The shaping of the limbs the perfect torso and magnificent, calmly musing profile surpass, if that be possible, the Greek ideal of beauty. The monkish, hooded figure on the Prophet's right is an unmistakable allusion to Savonarola; to the summons of duty and conscience, to the injunction not to linger unduly in the realms of Greek art. That is why the ignudo above resembles a bent Atlas straining under the weight of his cornucopia, bearing a world that casts a shadow upon his shoulders.

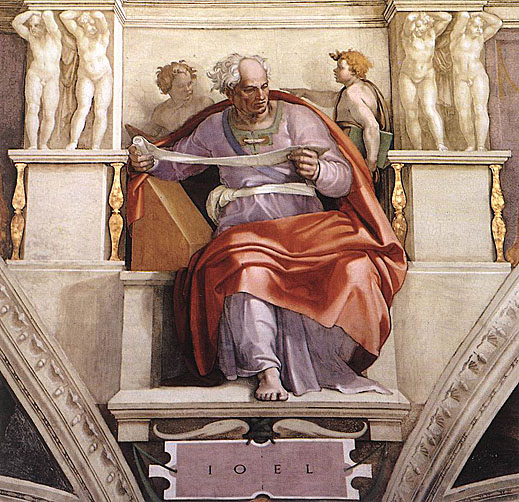

In Joel the state of inspiration, expressed by the light scrolls unfurled like a pennon and the flaming hair, has taken the place of acquired knowledge. The book is under the Prophet's feet, half hidden by the steep folds of his garment. The genii flanking the magnificent head re-enact the process: while one of them closes his book and raptly gazes across the Prophet's shoulder, the other brings his folio and acts as the devil's advocate and the spokesman of mere intellectual learning. Joel's shock is emphasized by a shifting of his body axis to the left. We find this grandiose diagonal movement again in the other giants: in Ezekiel, Daniel, and even more pronounced in Jonah. Joel in particular foresaw the coming of the Holy Ghost, and it is as though he shrank back before the consuming flame by which he none the less longs to be devoured. The lineal treatment of the Roman head - giving it the air of the mighty poet whom the High Renaissance failed to produce - carries to new heights the art form used by Signorelli.

God allows the youthful Jonah, the seer of Nineveh whom he rescued from the belly of the whale within three days - the time between Christ's death and his resurrection, - to challenge him in his bold nakedness, The figure mocks every law of composition and perspective. Michelangelo conceived Jonah as an Old Testament Prometheus touched by grace and presents us with a solution to the riddle of good and evil. An artist, himself a rebellious Titan, proffers a solution that spells deliverance in what may be the grandest piece of dialectical theology ever stated in terms of art. The rebellious Prophet, whom God would not have otherwise, looks up directly at his self begetting and affirming Maker. In his expression, scorn and rebellion are giving place to joy, delight, love and filial response, and the ecstatic contemplation of God. The monster of the sea, the calabash tree of the texts, and the turbulent genii form an animated background, unusually bucolic and idyllic for Michelangelo.

On entering the Chapel (generally through the east door, for contrary to prevalent custom the altar with the 'Last Judgement' occupies the west wall), one can see the Prophet Zechariah enthroned above. In ecclesiastical tradition Zechariah is young, but Michelangelo painted him as a man hoary with age, with a long beard and an ample green cloak, perhaps indicative of the unfathomable depth of his prophecies. This may be the earliest figure; it is extremely powerful but still somewhat clumsy, hardly suggesting a being who has received illumination. The old man is reading from his book, perhaps reciting the passages on the reconstruction of the temple, which he advocated.

Some scholars thought that Julius II and his counselors took it as a reference to the rebuilding of Saint Peter's. Zechariah prophesied the coming of a king riding into Jerusalem on a donkey, that is, Palm Sunday; and the Descent of the Holy Ghost, the Pentecost - both of which played a prominent part in the Church ritual of the Vatican. A crest with the oak of the della Rovere is placed on the console of Zechariah. Twin genii peer over the shoulder of the Prophet with the book.

Zechariah was one of the twelve 'lesser' prophets. Michelangelo chose two more, Joel and Jonah, from among them, in addition to the four major prophets Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel and Daniel. The remaining thrones are occupied by five of the twelve traditional Sibyls.

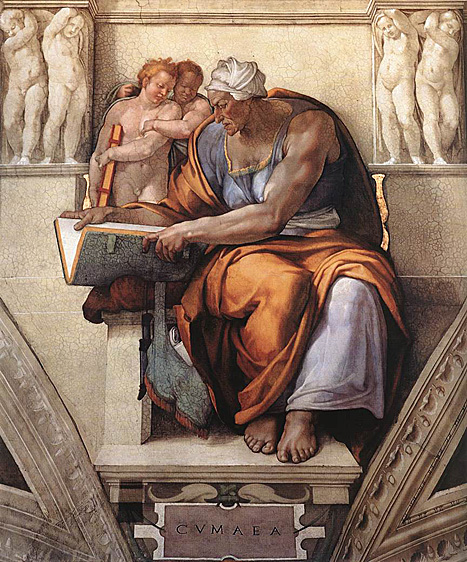

The Cumaean Sibyl oppresses by the sheer weight of her bulk and a commanding ugliness. With the open folio bound in green and her two genii gazing at its pages over her shoulders she has become one of the Fates, a towering shape with human features. Whenever Sibyls are mentioned, the Cumaea at once comes to mind. In the art of Michelangelo and other painters her powerful presence overshadows every other Sibyl, even her younger and more beautiful sisters, such as the Delphica.

Unwinding a scroll with her left hand, the Delphic Sibyl seems to be turning toward the viewer. The effect of movement is accentuated by the swirls of the light blue mantle lined with yellow fabric with red shadows and the pattern of the folds of the light green tunic. The very refined colours are characterized by delicate tonal passages and enamel-like surfaces.

The unique female figures and representations of the eternal mother are overwhelming. Of course, the Sibyls differ vastly from the Prophets, for Michelangelo remained mindful of the saying 'mulier taceat in ecclesia'. With the exception of the Pythia of Delphi, they are not conceived as priestesses. It is that which is beautiful and most characteristic, in short, their essentially feminine quality, that is brought out. As a group, including not only the three beautiful young women but the others too, they represent the Renaissance ideal of the virago, in the original sense of the word; a woman physically and mentally heroic. One must imagine these Sibyls free of male bondage, chiefly because their male aspect, existing side by side with the female - for they are not masculine women - is very much in evidence in the form of strength and power. This, admittedly, applies least of all to the Pythia of Delpbi who shines with a priestly and inspired radiance, which does not prevent this pagan servant of Apollo from being a young and enchanting girl.

The Delphic virgin is coifed with a white priestly band beneath a peacock blue headdress draped like a crown or diadem; she gives true oracles and lives on in the great Holy Virgins of Christian art, who often wear a sibylline expression. The left arm bent over the open scroll is prefigured in the 'Madonna Doni', the fair hair is blown back by the wind of the spirit.

The Erythraea (Erithraea in Michelangelo's spelling), is richly dressed and pensively turns the pages of a book, while one of her genii lights a votive lamp. The other echoes her state of trance. It is as though she were under some deep compulsion to rouse herself. The strange headdress threaded with her abundant tresses lends the head with its heavy-lidded eyes a dream-like quality. There is no indication of the Judgement she foresaw. Perhaps its only signs are the scared eyes of the ignudo to the left above her throne, who appears overcome by some frightful vision.

Primordial, totally detached, her eyes focused on things outside this world, and she herself almost a cave of mystery - such is the Persica of the Sistine Chapel. Something of Leonardo's chiaroscuro has crept into her composition. She is a presence still more powerful and secretive, magical and abstracted than the Cumaean Sibyl.

his fresco was commissioned by Pope Clement VII (1523-1534) shortly before his death. His successor, Paul III Farnese (1534-1549), forced Michelangelo to a rapid execution of this work, the largest single fresco of the century. The first impression we have when faced with the Last Judgment is that of a truly universal event, at the centre of which stands the powerful figure of Christ. His raised right hand compels the figures on the lefthand side, who are trying to ascend, to be plunged down towards Charon and Minos, the Judge of the Underworld; while his left hand is drawing up the chosen people on his right in an irresistible current of strength. Together with the planets and the sun, the saints surround the Judge, confined into vast spacial orbits around Him. For this work Michelangelo did not choose one set point from which it should be viewed. The proportions of the figures and the size of the groups are determined, as in the Middle Ages, by their single absolute importance and not by their relative significance. For this reason, each figure preserves its own individuality and both the single figures arid the groups need their own background.

The figures who, in the depths of the scene, are rising from their graves could well be part of the prophet Ezechiel's vision. Naked skeletons are covered with new flesh, men dead for immemorable lengths of time help each other to rise from the earth. For the representation of the place of eternal damnation, Michelangelo was clearly inspired by the lines of the Divine Comedy:

Charon the demon, with eyes of glowing coal/Beckoning them, collects them all,/Smites with his oar whoever lingers.

According to Vasari, the artist gave Minos, the Judge of the Souls, the semblance of the Pope's Master of Ceremonies, Biagio da Cesena, who had often complained to the Pope about the nudity of the painted figures. We know that many other figures, as well, are portraits of Michelangelo's contemporaries. The artist's self-portrait appears twice: in the flayed skin which Saint Bartholomew is carrying in his left-hand, and in the figure in the lower left hand corner, who is looking encouragingly at those rising from their graves. The artist could not have left us clearer evidence of his feeling towards life and of his highest ideals.

The painting is a turning point in the history of art. Vasari predicted the phenomenal impact of the work: "This sublime painting", he wrote, "should serve as a model for our art. Divine Providence has bestowed it upon the world to show how much intelligence she can deal out to certain men on earth. The most expert draftsman trembles as he contemplates these bold outlines and marvellous foreshortenings. In the presence of this celestial work, the senses are paralysed, and one can only wonder at the works that came before and the works that shall come after".

_1506.jpg)

The Doni tondo is Michelangelo's sole unanimously accepted panel painting. His only other documented easel painting, The Leda and the Swan, seems to have been destroyed and must be reconstructed from autograph drawings and copies. The tondo was probably produced for the same Doni for whom Raphael painted the pair of portraits, now in the Palazzo Pitti.

The Holy Family is in the foreground. The Virgin, a muscular young woman, is turning round with a complicated movement to take the Christ Child Joseph is handing to her over her shoulder. The meaning of this scene is both theologically and philosophically obscure, as is the significance of the naked young men in the background.

The spectacular gilt wood frame, attributed to the Tasso family of woodcarvers, displays the Doni family arms with lions on them intermingled with Strozzi crescents. As well as grotesques, the frame contains the heads of two prophets and two sybils surmounted by one of Christ. The outstanding quality of these busts - evoking similar figures of Lorenzo Ghiberti's Gates of Paradise - has lead some scholars to believe that Michelangelo may have had a hand in designing the frame.

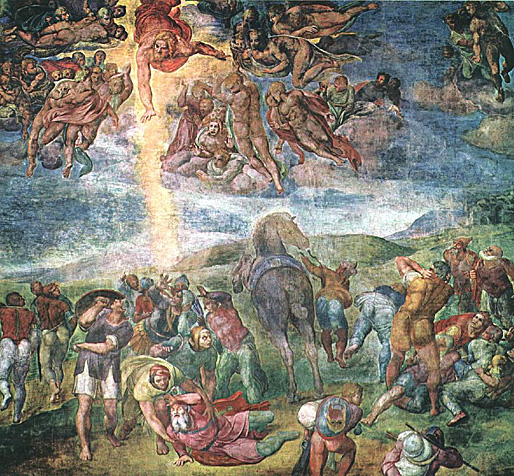

The conversion of Saul (St Paul) is the best-known and most widely represented of the Pauline themes (Acts 9:1-9). On the road to Damascus, where he was going to obtain authorization from the synagogue to arrest Christians, Paul was struck to the ground, blinded by a sudden light from heaven. The voice of God, heard also by Paul's attendants, as artists make clear, said, 'Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me?' They led him to the city where, the voice had said, he would told what he had to do. According to a tradition, connected with the medieval Custom of representing pride as a falling horseman, Paul made the journey on horseback. He lies on the ground as if just thrown from his horse, prostrate with awe, or unconcious. He may be wearing Roman armour. Christ appeares in the heavens, perhaps with three angels. Paul's attendants run to help him or try to control the rearing horses.

In Michelangelo's fresco the composition shows great depth of feeling obtained by the use of light and darkness that foreshadows Rembrandt and testifies to the heroic virtuosity of the aged master. A focal line traverses the the painting, its progression at once reveals the meaning of the composition. Starting at the top left it flows diagonally, along the figure of Christ descending and a beam of light. It follows a figure with raised fingers and another, bent over the fallen Saul, and circumscribes the ellipse of this body. From his right leg it curves back and upward in the direction of a horse galloping in the background, and loses itself in the undulating contours of the mountains with a vision of the heavenly Jerusalem faintly outlined in their folds - unless we accept a more literal explanation and call it Damascus. Note that this line has the shape of a bishop's staff and sums up the whole incident in symbolic form: Saul destined to be shepherd and overseer of people. (The term 'bishop' means overseer.) The high-light on the head of Saul and on the horse's head confirms the symbolic meaning; the dim awarness of fallen man is touched by the lightning flash of grace, and as universal conciousness awakens in him, he loses his animal torpor and gains true knowledge.

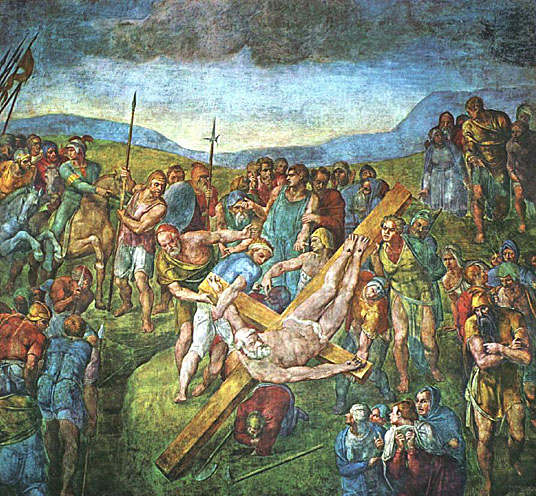

According to tradition, Peter was at his own wish crucified upside down, either on the Janiculum hill or in a circus arena between two metae, the pair of turning-posts or conical columns set in the ground at each end of the course. Artists have used both settings, depicting Peter on the cross at the moment of being lifted by soldiers, often surrounded by onlookers, or already raised in position, with a small group of women standing by in allusion to the similar group at Christ's crucifixion. A vision of the apostle's crucifixion appeared to Peter Nolasco.

In Michelangelo's composition everything is centred in the fearful event; in triumph over pain and suffering. Solace comes from the spectacle of fortitude, confidence and will-power; the intrepid character of Saint Peter. As in the fresco of St Paul, the main protagonists fits into an ellipse placed in the centre of the cross, extended on four sides by the disposition of the figures. This device lends to the design a clarity and strength which is absent from the restless Damascus scene, because there the fallen Saul appears suspended in mid-air at the lower edge of the picture, and the accompanying figures occupy different levels of space. In the Crucifixion, on the other hand, most of the figures are vertical; only those near the centre give the impression of rotating round the martyr. Their features betray the utmost horror, especially those of the women on the lower right who tremble with terror, and several onlookers seem on the verge of madness.

The horizontally of the long reading room is unexpected after the verticality of the vestibule. At first sight the room looks more conventional than the vestibule. However, the disturbing aspect of the room is that it has no reasonable focus or terminus. Pilasters, ceiling beams, and floor patterns produce a continuous cage of space in which the reading desks (also designed by Michelangelo) are trapped, two to a bay, and the observer with them. Since each of the bays is identical, the succession could contain two more or three less with no effect on the purely additive composition.

Antonio da Sangallo the Younger died in 1546, and the bulk of his unfinished work fell to Michelangelo. How he grappled with his task is evident from the palace which Cardinal Alessandro Farnese had long ago ordered Sangallo to build. Elected to the Papacy, Alessandro announced a contest for the cornice design, which Michelangelo won; whereupon he was left to finish the building. The master changed the character of the edifice completely by adding an impressive cornice with Farnese lilies and a superstructure to the uppermost storey, and by emphasizing the centre storey with a noble window and balcony, surmounted by the family escutcheon. Two more crests on either side are a later addition. An excellent drawing of 1840 by the architect of the Louvre, Hector Martin Lefuel, shows the façade as it was before it was spoilt by additions to the central axis.

The vertical edges of the building were reinforced by rustic work. The windows of the upper storey, with Romanesque arches surmounted by detached triangular cornices, lend an air of organic growth and lightness to the otherwise massive and portentous palace. Where Sangallo had wavered between a unity composed of many harmonious elements, and a single, dominant theme, Michelangelo brought everything under a common denominator. The airy, charming arcades of the courtyard were surmounted by stern walls with angulate pilasters and exceptionally beautiful windows with detached cornices.

The palaces at either side of the square were altered by Giacomo della Porte after Michelangelo's death, but much of Michelangelo's original work remains. From the point of view of architectural history the most important innovation made in these palaces was the introduction of the so-called Giant Order; that is, a pilaster or column which runs through two whole storeys.

_c1513.jpg)

_1519_36.jpg)

_1519_36.jpg)

_1519_36.jpg)

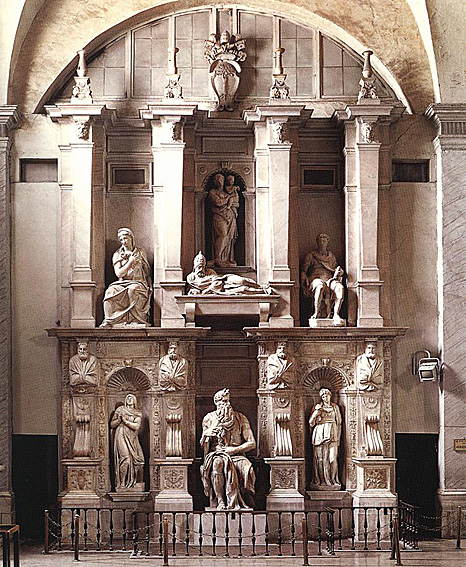

When, by the will of Pope Julius della Rovere (1503-13), Michelangelo went to Rome in 1505, the Pope commissioned him to build in the course of five years a tomb for the Pope. Forty life-sized statues were to surround the tomb which was to be 7 meter wide, 11 meter deep and 8 meter high; it was to be a free-standing tomb and to contain an oval funerary cell. Never, since classical times, had anything like this, in the West, been built for one man alone.

According to the iconographic plan, which we are able to reconstruct from written sources, this was to be an outline of the Christian world: the lower level was dedicated to man, the middle level to the prophets and saints, and the top level to the surpassing of both former levels in the Last Judgement. At the summit of the monument, there was to have been a portrayal of two angels leading the Pope out of his tomb on the day of the Last Judgement.

Michelangelo immediately began his preparations for this task, but the capricious Pope, in doubt of finding an appropriate place in which to erect his tomb, planned something even more grandiose: the restoration and remodelling of St Peter's. Thus Michelangelo was ordered to make other commissions, first in Bologna then in Rome, the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

After the death of the Pope in 1513 Michelangelo and the Pope's heirs reached a new agreement concerning the tomb. It was decided that the tomb was to be smaller and placed against a wall. After several further changes and simplifications the tomb was finally set up in San Pietro in Vincoli in Rome in 1545.

The slaves (four in Florence and two in Paris) were intended to the lower level, while the Moses for the middle level.

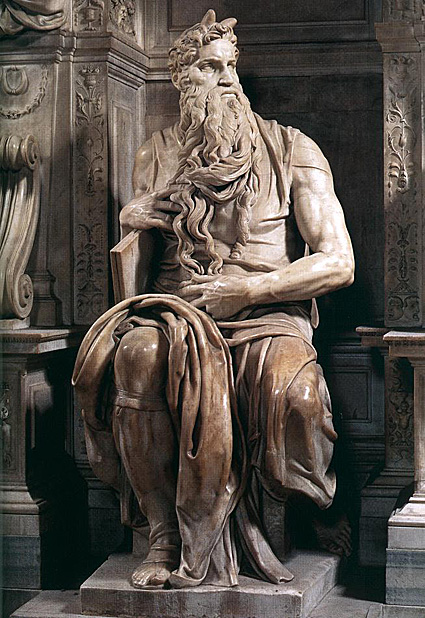

The statue of Moses is the summary of the entire monument, planned but never fully realized as the tomb of Julius II. It was intended for one of the six colossal figures that crowned the tomb. Elder brother to the Sistine Prophets, the Moses is also an image of Michelangelo's own aspirations, a figure in de Tolnay's words, "trembling with indignation, having mastered the explosion of his wrath".

The Moses was executed for Michelangelo's second project for the tomb of Julius II. Inspired perhaps by the medieval conception of man as microcosm, he brought together the elements in allegorical guise: the flowing beard suggests water, the wildly twisting hair fire, the heavy drape earth. In an ideal sense, the Moses represents also both the artist and the Pope, two personalities who had in common what is known as "terribilità". Conceived for the second tier of the tomb, the statue was meant to be seen from below and not as it is displayed today at eye-level.

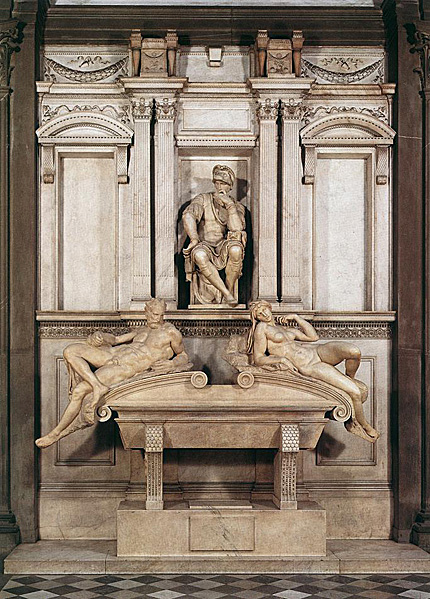

Medici Chapel (Cappella Medicea) is the chapel housing monuments to members of the Medici family, in the New Sacristy of the Church of San Lorenzo in Florence. The funereal monuments were commissioned in 1520 by Pope Clement VII (formerly Cardinal Giulio de' Medici), executed largely by Michelangelo from 1520 to 1534, and completed by Michelangelo's pupils after his departure.

The two monumental groups (for the tombs of Lorenzo, duke di Urbino, and Giuliano, duke de Nemours) are each composed of a seated armed figure in a niche, with an allegorical figure reclining on either side of the sarcophagus below. The seated figures, representing the two dukes, are not treated as portraits but as types. Lorenzo, whose face is shaded by a helmet, personifies the reflective man; Giuliano, who is holding the baton of an army commander, portrays the active man. At his feet recline the figures of "Night" and "Day." "Night," a giantess, is twisting in uneasy slumber; "Day," a herculean figure, looks wrathfully over his shoulder. Just as imposing, but far less violent, are the two companion figures reclining between sleep and waking on the sarcophagus of Lorenzo. The male figure is known as "Dusk," the female figure as "Dawn."

Lorenzo the Magnificent and his brother Giuliano the Elder were buried at the entrance wall, and over them was set up a marble group consisting of a "Madonna and Child" and the Medici patron saints Cosmas and Damian. The "Madonna" is a work of imposing majesty, completely by Michelangelo's own hand; the saints are the work of pupils after models by the master.

The picture shows the tomb of Giuliano de' Medici (at left) and the Virgin and Child between Sts Cosmas and Damian.

When Pope Leo X entered Florence in triumph in 1515, he and his cousins Giulio (later Pope Clement VII) initiated a series of commissions at San Lorenzo which built upon the projects of their Medici ancestors at that church. The new Sacristy, now generally known as the Medici Chapel, was designed as a burial pantheon for the Medici family.

Source: Web Gallery of Art

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.