Italian Early Renaissance Artist

1445 - 1510

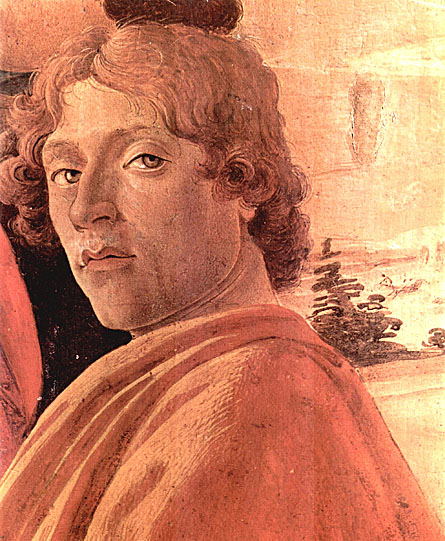

Alessandro di Mariano di Vanni Filipepi, better known as Sandro Botticelli or Il Botticello ("The Little Barrel") was an Italian painter of the Florentine school during the Early Renaissance. Less than a hundred years later, this movement, under the patronage of Lorenzo de' Medici, was characterized by Giorgio Vasari as a "golden age", a thought, suitably enough, he expressed at the head of his Vita of Botticelli. His posthumous reputation suffered until the late 19th century; since then his work has been seen to represent the linear grace of Early Renaissance painting, and The Birth of Venus and Primavera rank now among the most familiar masterpieces of Florentine art.

Details of Botticelli's life are sparse, but we know that he became an apprentice when he was about fourteen years old, which would indicate that he received a fuller education than did other Renaissance artists. Vasari reported that he was initially trained as a goldsmith by his brother Antonio. Probably by 1462 he was apprenticed to Fra Filippo Lippi; many of his early works have been attributed to the elder master, and attributions continue to be uncertain. Influenced also by the monumentality of Masaccio's painting, it was from Lippi that Botticelli learned a more intimate and detailed manner. As recently discovered, during this time, Botticelli could have traveled to Hungary, participating in the creation of a fresco in Esztergom, ordered in the workshop of Fra Filippo Lippi by Vitéz János, then archbishop of Hungary.

By 1470 Botticelli had his own workshop. Even at this early date his work was characterized by a conception of the figure as if seen in low relief, drawn with clear contours, and minimizing strong contrasts of light and shadow which would indicate fully modeled forms.

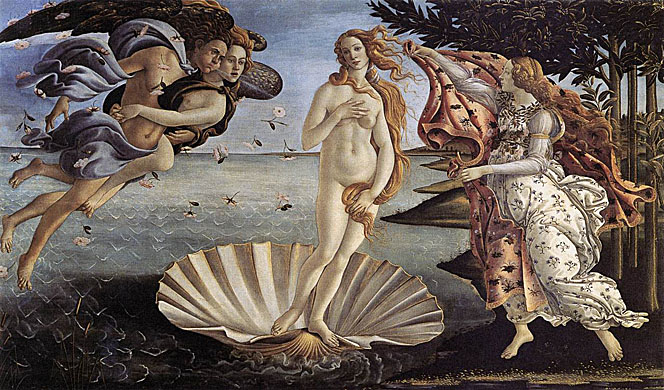

The masterworks Primavera (ca. 1478) and The Birth of Venus (ca. 1485) were both seen by Vasari at the villa of Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de' Medici at Castello in the mid-16th century, and until recently it was assumed that both works were painted specifically for the villa. Recent scholarship suggests otherwise: the Primavera was painted for Lorenzo's townhouse in Florence, and The Birth of Venus was commissioned by someone else for a different site. By 1499 both had been installed at Castello.

In these works the influence of Gothic realism is tempered by Botticelli's study of the antique. But if the painterly means may be understood, the subjects themselves remain fascinating for their ambiguity. The complex meanings of these paintings continue to receive scholarly attention, mainly focusing on the poetry and philosophy of humanists who were the artist's contemporaries. The works do not illustrate particular texts; rather, each relies upon several texts for its significance. Of their beauty, characterized by Vasari as exemplifying "grace", and by John Ruskin as possessing linear rhythm, there can be no doubt.

The Adoration of the Magi for Santa Maria Novella (ca. 1475-1476, now at the Uffizi) contains the portraits of Cosimo de' Medici ("the finest of all that are now extant for its life and vigor", his grandson Giuliano de' Medici, and Cosimo's son Giovanni. The quality of the scene was hailed by Vasari as one of Botticelli's pinnacles.

In 1481, Pope Sixtus IV summoned Botticelli and other prominent Florentine and Umbrian artists to fresco the walls of the Sistine Chapel. The iconological program was the supremacy of the Papacy. Sandro's contribution was moderately successful. He returned to Florence, and "being of a sophisticed turn of mind, he there wrote a commentary on a portion of Dante and illustrated the Inferno which he printed, spending much time over it, and this abstention from work led to serious disorders in his living." Thus Vasari characterized the first printed Dante (1481) with Botticelli's decorations; he could not imagine that the new art of printing might occupy an artist.

In the mid-1480's Botticelli worked on a major fresco cycle with Perugino, Ghirlandaio, and Filippino Lippi, for Lorenzo the Magnificent's villa near Volterra; in addition he painted many frescoes in Florentine churches.

In 1491 Botticelli served on a committee to decide upon a facade for the Florence Duomo. In 1502 he was accused of sodomy, though charges were later dropped. In 1504 he was a member of the committee appointed to decide where Michelangelo's David would be placed. His later work, especially as seen in a series on the life of Saint Zenobius, witnessed a diminution of scale, expressively distorted figures, and a non-naturalistic use of color reminiscent of the work of Fra Angelico nearly a century earlier.

In later life, Botticelli was one of Savonarola's followers, though the full extent of Savonarola's influence is uncertain. The story that he burnt his own paintings on pagan themes in the notorious "Bonfire of the Vanities" is not told by Vasari, who asserts that of the sect of Savonarola "he was so ardent a partisan that he was thereby induced to desert his painting, and, having no income to live on, fell into very great distress. For this reason, persisting in his attachment to that party, and becoming a Piagnone he abandoned his work.". Botticelli biographer Ernst Steinman searched for the artist's psychological development through his Madonnas. In the "deepening of insight and expression in the rendering of Mary's physiognomy", Steinman discerns proof of Savonarola's influence over Botticelli. This means that the biographer needed to alter the dates of a number of Madonnas to substantiate his theory; specifically, they are dated ten years later than before. Steinman disagrees with Vasari's assertion that Botticelli produced nothing after coming under the influence of Girolamo Savonarola. Steinman believes the spiritual and emotional Virgins rendered by Sandro follow directly from the teachings of the Dominican monk.

Earlier, Botticelli had painted an Assumption of the Virgin for Matteo Palmieri in a chapel at San Pietro Maggiore in which, it was rumored, both the patron who dictated the iconic scheme and the painter who painted it, were guilty of unidentified heresy, a delicate requirement in such a subject. The heretical notions seem to be Gnostic in character:

By the side door of San Piero Maggiore he did a panel for Matteo Palmieri, with a large number of figures representing the Assumption of Our Lady with zones of patriarchs, prophets, apostles, evangelists, martyrs, confessors, doctors, virgins, and the orders of angels, the whole from a design given to him by Matteo, who was a worthy and educated man. He executed this work with the greatest mastery and diligence, introducing the portraits of Matteo and his wife on their knees. But although the great beauty of this work could find no other fault with it, said that Matteo and Sandro were guilty of grave heresy. Whether this is true or not, I cannot say. (Giorgio Vasari)

This is a common misconception based on an error by Vasari. The painting referred to here, now in the National Gallery in London, is by the artist Botticini. Vasari confused their similar sounding names.

Botticelli was already little employed in 1502; after his death his reputation was eclipsed longer and more thoroughly than that of any other major European artist. His paintings remained in the churches and villas for which they had been created, his frescoes in the Sistine Chapel upstaged by Michelangelo's. The first nineteenth century art historian to have looked with satisfaction at Botticelli's Sistine frescoes was Alexis-François Rio. Through Rio Mrs. Jameson and Sir Charles Eastlake were alerted to Botticelli, but, while works by his hand began to appear in German collections, both the Nazarenes and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood ignored him. Walter Pater created a literary picture of Botticelli, who was then taken up by the Aesthetic movement. The first monograph on the artist was published in 1893; then, between 1900 and 1920 more books were written on Botticelli than any other painter.

Botticelli's early works are recognized to be predominantly small and medium format panel paintings of the Madonna, the composition of which usually bears some relation to famous pictures by his teacher, Filippo Lippi. His earliest biblical history painting, an Adoration of the Magi, the first in a long tradition of Adoration pictures by Botticelli was painted in this period.

The Three Kings' magnificent retinue has reached the stable in Bethlehem. The eldest king is kneeling humbly in front of the child. The panel painting's unusual dimensions created difficulties for the young painter. When compared to the crowded group of figures on the left, the right side seems strangely empty.

Mary is enthroned on clouds in a glory of seraphim. The Christ Child, with the cruciform nimbus, is looking towards the observer and raising his hand in blessing. Botticelli has succeeded in expressing the tensions in this theme with sensitivity: the mother, who is fully aware of the Passion her son will suffer, is holding him protectively in her arms.

Arising strictly from the format of the picture, the arch structure frames the group of mother and child sitting on a stone bench. There is a powerful three-dimensional quality to the figures. Behind the Madonna we can look out onto a garden. A rose bush is clearly visible there, a traditional symbolic image referring to Mary.

Composition, shape and stylistic elements put this Madonna and Child close to another panel painted by Botticelli in his youth, the Fortitude, dated around 1470.

The figure of Fortitude is placed on a high throne with elaborately carved arms, a piece clearly traceable to Verocchio, but the feeling of tension that this thoughtful figure gives off surely comes from Antonio del Pollaiolo. The blue enamel work on the armor and the highlights on the metal are particularly interesting as they indicate a thorough knowledge of the goldsmith's art. The way in which the cloth is portrayed comes from Verocchio. The energy and vitality of the girl in armor, expressed in her face and her pose, is an original creation of Botticelli and shows clearly the very personal way in which he developed and enriched the styles of his contemporaries.

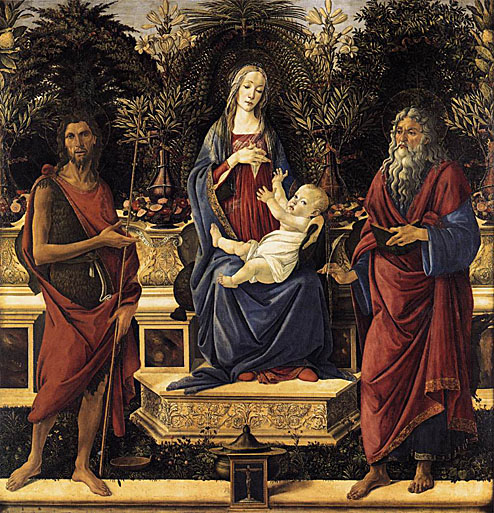

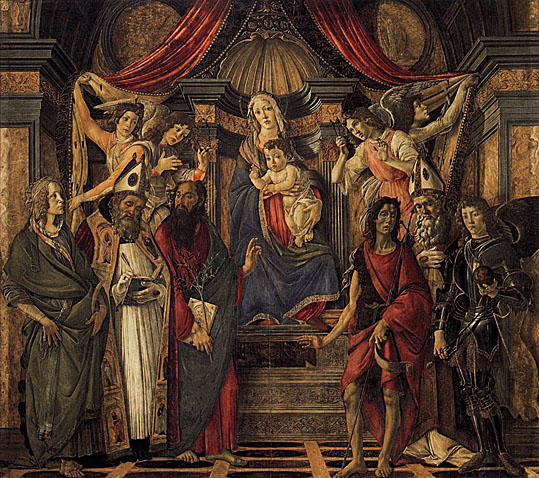

This type of altar painting is called a Sacra Conversazione, and it shows the enthroned Madonna surrounded by saints. To the left are Mary Magdalene with the ointment jar and St John the Baptist wearing furs, and to the right are Saint Francis of Assisi in the Franciscans' habit and Catherine of Alexandria with her wheel. The two kneeling saints, Cosmas and Damian, were patron saints of both the Medici's and doctors and pharmacists.

Behind the monumental, very sculptural figures is a broad, hilly landscape with a river. The boy-like angel appears to have just this moment stepped through the gap in the wall and come up to Mary and the child; he is presenting them with a bowl decorated with ears of grain and full of grapes. The Christ Child is blessing the gifts, which symbolize the bread and wine of the Eucharist.

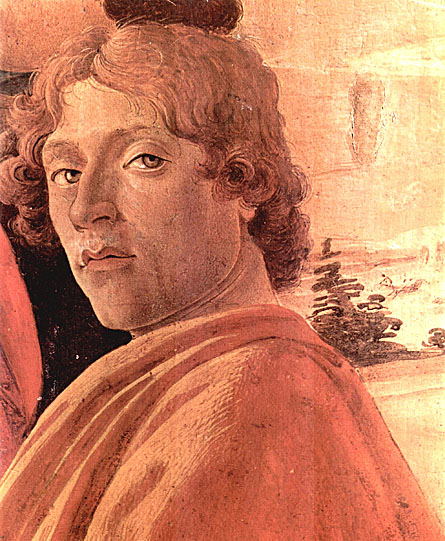

The Biblical tale of Judith, who slew Holofernes, the Assyrian king's commander-in-chief, because he represented a deadly threat for the Hebrews in Bethulia, was one of the favorite subjects of the Florentine Renaissance. Judith was considered the prototype of female strength, since she alone had summoned up the courage to murder the tyrant. In The Return of Judith to Bethulia, Botticelli shows us Judith together with Abra, her maid, the two of them striding out in a well-nigh furious manner. Abra is carrying Holofernes' severed head on her own head, while Judith has an olive branch in her hand as a symbol of peace, which she is bringing to the Hebrews. Botticelli has succeeded here in capturing both movement and stillness in a unique balance. Judith is pausing a moment in her striding forward to turn towards the observer, self-assured if not without a touch of melancholy, exactly as if she wished to present herself as the victor.

The soldiers are standing in dismay around the bed on which the headless body of their commander Holofernes is lying. They had expected to find him in Judith's arms, who, however, is already hurrying home. There is only a brief description of the scene in the Bible, and it clearly stimulated Botticelli's imagination. When compared to the other painting, however, the youthful well-formed body presents us with a contradiction: in that painting, the cut off head of Holofernes has the features of an older bearded man.

Surrounded by eight wingless angels, Mary is breastfeeding her Child. There is direct eye contact with the observer, involving him in the intimate scene. The angels are holding lilies, the sign of Mary's purity, and are engaged in antiphonal singing: while some of them are calmly waiting to start, the others are singing and reverently looking at a hymn book.

Botticelli created the additions to the scene with a great deal of loving detail, and the ensemble of boxes and a lavish fruit bowl is very much like a still-life. The parchment pages of the book, the materials and the transparent veils have an incredibly tangible quality to them. Another refinement of Botticelli's painting is the gold filigree with which he decorated the robes and objects. The use of expensive gold paint was a result of a contractual agreement made with the clients, which laid down the price of the painting.

The painting was lavishly covered with gold paint; like the Raczynski Tondo, it contains nearly life-size figures. The Virgin, crowned by two angels, is depicted as the Queen of Heaven. Two of the wingless angels are crowning the Queen of Heaven. The crown she is wearing is a delicate piece of goldsmiths work consisting of innumerable stars; they are an allusion to the 'Stella matutina' (morning star), one of the Mother of God's names in contemporary hymns devoted to Mary.

There is such a complex solution to the sequence of crowded figures in front of the stone window that it is possible to look out between Mary and the angels on the left onto a broad landscape laid out according to the rules of atmospheric perspective. The three angels have moved towards the Virgin and Child. The one at the front is kneeling and holding an open book and inkwell. Encouraged by the Christ Child, the Virgin is about to dip her quill and write the last words of the Magnificat, beginning on the right page with the large initial "M". The pomegranate which the mother and child are both holding is a symbol of the Passion and adds to the basic melancholy and meditative mood of the painting.

The background of the picture opens out into a landscape, in similar manner to the background in the Madonna del Libra where the open window allows the observer a glimpse of the view outside. These landscapes point to the influence exerted upon Botticelli by contemporary Netherlands' artists such as Jan van Eyck, Rogier van der Weyden and Hubert van der Goes. Trading relations between Italy and the Netherlands had been growing more intensive since the 15th century, resulting in many Florentine merchants and bankers travelling northwards. Among the mementos which these people brought back were paintings revealing other artistic conceptions and ideals. The Italian painters particularly admired the detailed execution of individual pictorial motifs, the realistic fashioning of the figures in the pictures, and the atmospheric effect of the landscapes as rendered in the art of their colleagues north of the Alps, and each incorporated the motifs of the latter into his own pictures after his own manner.

This portrait of the Virgin represents the costliest tondo that Botticelli ever created: in no other painting did he employ so much gold as in this one, using it for the ornamentation of the robes, for the divine rays, and for Mary's crown, and even utilizing it to heighten the hair color of Mary and the angels. As the most expensive paint, gold was normally used only sparingly. Its liberal employment here will therefore have been at the express wish of the person commissioning the work.

The Christ Child, whose hand is raised in blessing, is lying securely in the arms of Mary, but the sad, melancholy expression on the faces of mother and child are intended to remind the observer of the torments the Son of God will suffer in the future. The angels are worshipping Mary with lilies and garlands of roses. The Rosary is a prayer that was created in its present form in the 15th century, and rapidly became widespread. The beginning of this prayer is embroidered on the left angel's stola: AVE GRAZIA PLENA (Hail Mary, full of grace).

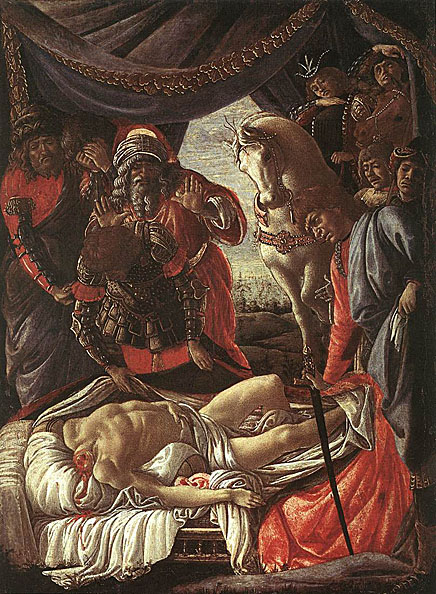

Portrayed as the so-called Madonna lactans, the Virgin is baring her breast in order to feed her child. The client, Giovanni de' Bardi, chose the two saints John the Baptist and John the Evangelist, his patron saints, as intercessors. The Baptist, being the patron saint of Florence, was accorded the place of honor to the right of the Mother of God, and he is pointing the observer towards the Madonna and child. At his feet lies the instrument of his work, the baptismal bowl. The Evangelist to the left of Mary is an old man; he is holding a quill and book, and the eagle behind him is his evangelist's symbol.

The composition of this Sacra Conversazione clearly shows his originality. Botticelli produced a different solution to the classical three-part structure of such paintings, showing the enthroned Madonna and Child flanked by saints, from that of his artistic colleagues. He did not simply use architectural elements to structure the picture surface, but mainly used naturalistically painted niches of foliage to form a deferential backdrop for the holy figures.

The political and religious crisis of the 1490's clearly left its mark on Botticelli's late work. He created fewer monumental works and devoted himself principally to producing devotional pictures and small altars. His themes were now almost exclusively religious ones. In his style there was a decisive change to a hitherto unknown degree of soberness and strictness. In his compositions, he increasingly dispensed with lively decorations, concentrating instead on expressive structuring of the figures. It would be oversimplifying to ascribe this evident change in Botticelli's later works exclusively to the influence of Savonarola, as Vasari does. If he is to be believed, Botticelli was a keen follower of Savonarola, and neglected his work to such an extent that he became impoverished. But quite the opposite must have been the case, he was reasonably well off, and he continued to work until after 1500, as is proven by existing works and documents.

However, the artist did not remain unaffected by the events of his time. The change in Botticelli's style appears to be an indicator of the spirit of the time shortly before the end of the century, shaped as it was by political unrest and a belief that the last days were at hand.

The dead Christ is lying lifelessly on a fine cloth in his mother's lap, and she has fallen back in a swoon against the shoulders of his favorite disciple, John. The two Mary's are gently supporting the head and feet of the crucified man. Mary Magdalene is fearfully and sorrowfully gazing at the crucifixion nails. Saint Jerome, Saint Paul and Saint Peter are observing the moving scene. The fervent gestures and postures of the figures express their grief at the death of Christ - a religious emotion intended to include the observer.

Originally the painting was in the church of San Paolino in Florence. After restoring in the Galleria degli Uffizi in 1813 it was purchased by the King of Bavaria.

As in the earlier Lamentation in Munich, the scene is brought vividly close to the observer, in order to create feelings of sympathy in him. The group of mourners in front of the dark rock tomb is arranged in the form of a cross. At its top is Joseph of Arimathea. He is gazing painfully up to heaven as he holds out the instruments of Christ's Passion.

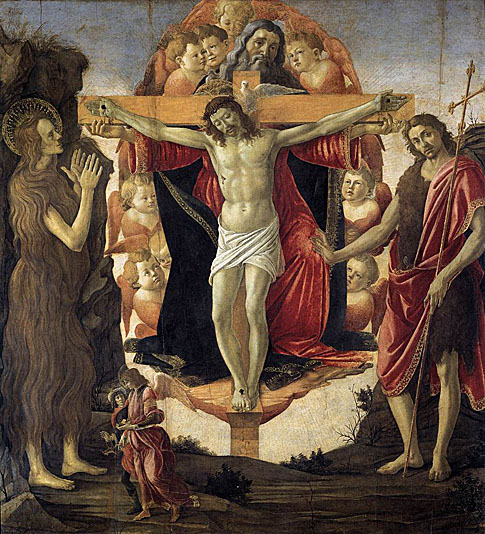

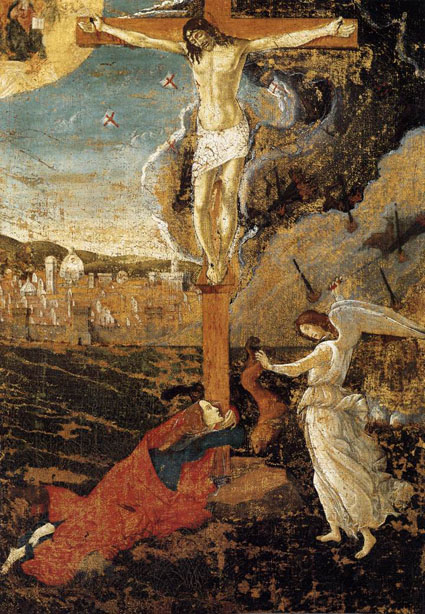

The Holy Trinity appears as a vision between the penitent saints Magdalene and John in a bleak desert landscape. The Baptist is inviting the observer to worship the Trinity, and Mary Magdalene is turning to face it full of emotion. The exhausted figure of the penitent, a late work of Donatello's, had a decisive influence on Botticelli's Magdalene.

The penitent sinner was the patron saint of the nuns' monastery of the Magdalenes, and this pala or altarpiece was ordered for their church. The figures of Tobias and the angel are very small compared to the others. They might be a reference to the donors of the altar, the guild of doctors and apothecaries: Archangel Raphael was their patron saint.

The subject of the work is the moment in which Saint Jerome receives the sacred Host from the hands of his companion, Saint Eusebius, for the last time before the former's death. The painter has opened one of the walls of the hut and has depicted the events in a bare room covered with wickerwork. According to apocryphal tradition, the saint died in a monastery close to Bethlehem. The painting, which is designed for the observers spiritual edification, presents an exemplary view of the saint's modest way of life.

Two angels are ceremoniously opening the curtains of a baldachin-like tent, underneath which a further heavenly messenger is carrying the Christ Child to his mother. Mary is kneeling and has bared her breast in order to feed the child. The unusual size of the figure of Mary is a characteristic of Botticelli's late work; he frequently emphasized the importance of the main figures in his scenes by increasing their size.

The city of Florence may be seen in the background, spread out in bright light under a clear sky. Within the city walls, the dome of the Cathedral, the Campanile, the Baptistery and the Palazzo Vecchio - the seat of government - to name but a few buildings, are readily recognizable.

The painting was probably executed by the workshop after Botticelli's design.

In the earlier work, the picture was dominated by movement and lively gracefulness; now, concentrated pictorial composition and simplicity come to the fore. With the former picture, the observer's thoughts were distracted by the detailed presentation of the figures and the background; in the later version, Botticelli has left out everything that could divert attention from the principal figure, from Judith herself. Thus, Abra the maid no longer appears next to Judith, but is relegated to the dark opening of the tent in the background. At the same time, Botticelli has reduced everything of a decorative nature to a minimum. Background and earth appear merely as a monotone surface, while the dark, unadorned garments remind one that the elegant flow of folds found in the bright, richly ornamented dress of the earlier portrayals is absent here. In this work too, the form of Judith herself strikes us as having overlong proportions, such as strangely distort her and present a crass contrast to the gracefulness of the earlier Judith. Botticelli was evidently less concerned in this late phase with entertaining the observer, concentrating rather on a form of his pictorial subject matter which would edify and instruct.

It has been suggested that this picture, the only surviving work signed by Botticelli, was painted for his own private devotions, or for someone close to him. It is certainly unconventional, and does not simply represent the traditional events of the birth of Jesus and the adoration of the shepherds and the Magi or Wise Men. Rather it is a vision of these events inspired by the prophecies in the Revelation of Saint John. Botticelli has underlined the non-realism of the picture by including Latin and Greek texts, and by adopting the conventions of medieval art, such as discrepancies in scale, for symbolic ends. The Virgin Mary, adoring a gigantic infant Jesus, is so large that were she to stand she could not fit under the thatch roof of the stable. They are, of course, the holiest and the most important persons in the painting.

The angels carry olive branches, which two of them have presented to the men they embrace in the foreground. These men, as well as the presumed shepherds in their short hooded garments on the right and the long-gowned Magi on the left, are all crowned with olive, an emblem of peace. The scrolls wound about the branches in the foreground, combined with some of those held by the angels dancing in the sky, read: 'Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace, goodwill toward men' (Luke 2:14). As angels and men move ever closer, from right to left, to embrace, little devils scatter into holes in the ground. The scrolls held by the angels pointing to the crib once read: `Behold the Lamb of God, which taketh away the sin of the world' the words of John the Baptist presenting Christ (John 1:29). Above the stable roof the sky has opened to reveal the golden light of paradise. Golden crowns hang down from the dancing angels' olive branches. Most of their scrolls celebrate Mary: 'Mother of God', 'Bride of God', 'Sole Queen of the World'.

The puzzling Greek inscription at the top of the picture has been translated: 'I Sandro made this picture at the conclusion of the year 1500 in the troubles of Italy in the half time after the time according to the 11th chapter of Saint John in the second woe of the Apocalypse during the loosing of the devil for three and a half years then he will be chained in the 12th chapter and we shall see [...] as in this picture.' The missing words may have been 'him burying himself'. The 'half time after the time' has been generally understood as a year and a half earlier, that is, in 1498, when the French invaded Italy, but it may mean a half millennium (500 years) after a millennium (1000 years): 1500, the date of the painting. Like the end of the millennium in the year 1000, the end of the half millennium in 1500 also seemed to many people to herald the Second Coming of Christ, prophesied in Revelation.

At a time when Florentine painters were recreating nature with their brush, Botticelli freely acknowledged the artificiality of art. In the pagan Venus and Mars he turned his back on naturalism in order to express ideal beauty. In the 'Mystic Nativity' he went further, beyond the old-fashioned to the archaic, to express spiritual truths - rather like the Victorians who were to rediscover him in the nineteenth century, and who associated the Gothic style with an 'Age of Faith'.

Botticelli had been receiving more and more commissions from clients outside Florence since the end of the 1470's; the most influential of these was Pope Sixtus IV, upon whose orders Botticelli was summoned to Rome in 1481. Together with his Florentine colleagues Domenico Ghirlandaio and Cosimo Rosselli and the Perugian Pietro del Perugino, Botticelli was to decorate the walls of the papal electoral chapel - called the "Sistine Chapel" after its builder, Sixtus IV - with frescoes. However, it was not until the later work on it by Michelangelo, who executed the frescoes on the ceiling and the altar wall between 1508 and 1512 under Julius II, that the chapel would achieve its greatest fame.

The painting of the walls took place over an astonishingly short period of time, barely eleven months, from July, 1481 to May, 1482. The painters were each required first to execute a sample fresco; these were to be officially examined and evaluated in January, 1482. However, it was so evident at such an early stage that the frescoes would be satisfactory that by October 1481, the artists were given the commission to execute the remaining ten stories.

The pictorial program for the chapel was comprised a cycle each from the Old and New Testament of scenes from the lives of Moses and Christ. The narratives began at the altar wall - the frescoes painted there yielding to Michelangelo's Last Judgment a mere thirty years later - continued along the long walls of the chapel, and ended at the entrance wall. A gallery of papal portraits was painted above these depictions, and the latter were completed underneath by representations of painted curtains. The individual scenes from the two cycles contain typological references to one another. The Old and New Testament are understood as constituting a whole, with Moses appearing as a representation of Christ.

The typological positioning of the Moses and Christ cycles has a political dimension going beyond a mere illustrating of the correspondences between Old and New Testament. Sixtus IV was employing a precisely conceived program to illustrate through the entire cycle the legitimacy of his papal authority, running from Moses, via Christ, to Peter, whose ultimate authority, conferred by Christ, finds its continuation in the Popes. The portraits of the latter above the narrative depictions served emphatically to illustrate the ancestral line of their God-given authority.

The two most important scenes from the fresco cycle Perugino's Christ Gives the Keys to Peter and Botticelli's The Punishment of Korah, both reveal in the background the triumphal arch of Constantine, the first Christian emperor, who gave the Pope temporal power over the Roman western world. The triumphal arch serves here as a prominent allusion to the power of the Pope, granted him by the Emperor. Sixtus IV was thereby not only illustrating his position in a line of succession starting in the Old Testament and continuing through the New Testament up to contemporary times, but was simultaneously declaring his view of himself as the legitimate successor to the Roman emperorship.

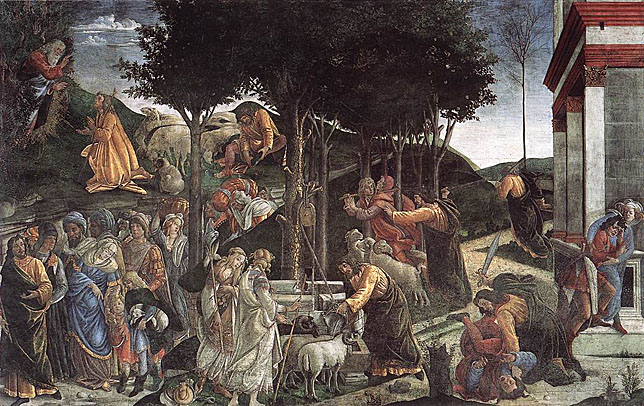

Botticelli painted three scenes within the short period of eleven months: Scenes from the Life of Moses, The Temptation of Christ and The Punishment of Korah. He also painted, with much help from his workshop, in the niches above the biblical scenes, some portraits of popes which have been considerably painted over. In all these works his painting appears relatively weak.

Eusebius tells us that Constantine was baptized just prior to his death, but he also allowed himself to be worshipped within the army as Mithras which was solely for political support. However, there was significant religious settlement in AD 313 that would eventually have a far reaching impact on the Christian Church. This settlement is more commonly known as the Edict of Milan only resulted in religious toleration for Christians, but Christianity was not officially given a position of Primacy in a Pagan World.

Since we saw that freedom of worship ought not to be denied, but that to each man's judgment and will the right should be given to care for sacred things according to each man's free choice, we have already some time ago bidden the Christians to maintain the faith of of their own sect and worship. But since in that edict by which such right was granted to the aforesaid Christians many and varied conditions clearly appeared to have been added, it may well perchance have come about that after a short time many were repelled from practicing their religion. This I, Constantine Augustus, and I, Licinius Augustus, had met at Mediolanum (Milan) and were discussing all those matters which relate to the advantage and security of the State, among the other things which we saw would benefit the majority of men we were convinced that first of all those conditions by which reverence for the Divinity is secured should be put in order by us to the end that we might give to the Christians and to all men the right to follow freely whatever religion each had wished, so that thereby whatever of Divinity there be in the heavenly seat may be favorable and propitious to us and to all those are placed under our authority. And so by a salutary and most fitting line of reasoning we came to the conclusion that we should adopt this policy -- namely our view should be that to no one whatsoever should we deny liberty to follow either the religion of the Christians or any other cult which of his own free choice he has thought to be best adapted for himself, in order that the supreme Divinity, to whose service we render our free obedience, may bestow upon us in all things his wonted favor and benevolence. Wherefore we would that your Devotion should know that is is our will that all those conditions should be altogether removed which were contained in our former letters addressed to you concerning the Christians (and which seemed to be entirely perverse and alien from our clemency) --- those should be removed and now in freedom and without restriction let all those who desire to follow the aforesaid religion of the Christians hasten to follow the same without any molestation or interference. We have felt that the fullest information should be furnished on this matter to your carefulness that you might be assured that we have given to the aforesaid Christians complete and unrestricted liberty to follow their religion. Further, when you see that this indulgence has been granted to others also a similar free and unhindered liberty of religion and of our times, so that it may be open to every man to worship as he will. This has been done by us so that we should not seem to have done dishonor to any religion.

Licinius attempted to revive persecution in his attempt to challenge Constantine for sole authority in the Roman World. Constantine defeated Licinius and became the sole emperor in 324. However, it was not until 380 when Emperor Theodosius made Christianity the official religion of the Empire. Just a little clarification for a little better understanding of actually when this confluence between politics and religion began within the Christian Church.

Senex Magister

The portraits of the popes are imaginary. As can be seen in the figure of Sixtus II, a namesake of the pope who commissioned the work, they are full length figures placed in niches and painted, so as to be seen from far below, high up on the walls of the room. All popes are shown wearing pontifical robes and the tiara.

The Scenes from the Life of Moses is located in the second compartment on the south wall of the Chapel. Botticelli integrated seven episodes from the life of the young Moses into the landscape with considerable skill, by opening up the surface of the picture with four diagonal rows of figures. The scenes should be read from right to left: Moses in a shining yellow garment angrily strikes an Egyptian overseer and then flees to the Midianites. There he disperses a group of shepherds who were preventing the daughters of Jethro from drawing water at the well. After the divine revelation in the burning bush at the top left, Moses obeys God commandment and leads the people of Israel in a triumphal procession from slavery in Egypt.

As the Moses cycle starts on the wall behind the altar, the scenes should, unlike the pictures of the temptations of Christ, be read from right to left: Moses in a shining yellow garment angrily strikes an Egyptian overseer and then flees to the Midianites. There he disperses a group of shepherds who were preventing the daughters of Jethro from drawing water at the well. After the divine revelation in the burning bush at the top left, Moses obeys God commandment and leads the people of Israel in a triumphal procession from slavery in Egypt.

The message of this painting provides the key to an understanding of the Sistine Chapel as a whole before Michelangelo's work. The fresco, located in the fifth compartment on the south wall, reproduces three episodes, each of which depicts a rebellion by the Hebrews against God's appointed leaders, Moses and Aaron, along with the ensuing divine punishment of the agitators. On the right-hand side, the revolt of the Jews against Moses is related, the latter portrayed as an old man with a long white beard, clothed in a yellow robe and an olive-green cloak. Irritated by the various trials through which their emigration from Egypt was putting them, the Jews demanded that Moses be dismissed. They wanted a new leader, one who would take them back to Egypt, and they threatened to stone Moses; however, Joshua placed himself protectively between them and their would-be victim, as depicted in Botticelli's painting.

The center of the fresco shows the rebellion, under the leadership of Korah, of the sons of Aaron and some Levites, who, setting themselves up in defiance of Aaron's authority as high priest, also offered up incense. In the background we see Aaron in a blue robe, swinging his incense censer with an upright posture and filled with solemn dignity, while his rivals stagger and fall to the ground with their censers at God's behest. Their punishment ensues on the left-hand side of the picture, as the rebels are swallowed up by the earth, which is breaking open under them. The two innocent sons of Korah, the ringleader of the rebels, appear floating on a cloud, exempted from the divine punishment.

The principal message of these scenes is made manifest by the inscription in the central field of the triumphal arch: "Let no man take the honor to himself except he that is called by God, as Aaron was." The fresco thus holds a warning that God's punishment will fall upon those who oppose God's appointed leaders. This warning also contained a contemporary political reference through the portrayal of Aaron in the fresco, depicted wearing the triple-ringed tiara of the Pope and thus characterized as the papal predecessor. It was a warning to those questioning the ultimate authority of the Pope over the Church. The papal claims to leadership were God-given, their origin lay in Christ giving Peter the keys to the kingdom of heaven and thereby granting him privacy over the young Church. Perugino painted this crucial element of the doctrine of papal supremacy immediately opposite Botticelli's fresco.

The fresco which Botticelli began in July, 1481, is the third scene within the Christ cycle and depicts the Temptation of Christ. Christ's threefold temptation by the Devil, as described in the Gospel according to Matthew, can be seen in the background of the picture, with the devil disguised as a hermit. At top left, up on the mountain, he is challenging Christ to turn stones into bread; in the centre, we see the two standing on a temple, with the Devil attempting to persuade Christ to cast himself down; on the right-hand side, finally, he is showing the Son of God the splendor of the world's riches, over which he is offering to make Him master. However, Christ drives away the Devil, who ultimately reveals his true devilish form. On the right in the background, three angels have prepared a table for the celebration of the Eucharist, a scene which only becomes comprehensible when seen in conjunction with the event in the foreground of the fresco. The unity of these two events from the point of view of content is clarified by the reappearance of Christ with three angels in the middle ground on the left of the picture, where He is apparently explaining the incident occurring in the foreground to the heavenly messengers. We are concerned here with the celebration of a Jewish sacrifice, conducted daily before the Temple in accordance with ancient custom. The high priest is receiving the blood-filled sacrificial bowl, while several people are bringing animals and wood as offerings.

At first sight, the inclusion of this Jewish sacrificial scene in the Christ cycle would appear extremely puzzling; however, its explanation may be found in the typological interpretation. The Jewish sacrifice portrayed here refers to the crucifixion of Christ, who through His death offered of His flesh and blood for the redemption of mankind. Christ's sacrifice is reconstructed in the celebration of the Eucharist, alluded to here by the gift table prepared by the angels.

The Guild of Doctors and Apothecaries (a very important organization in Florence) commissioned from Botticelli this very grand altarpiece for the church of San Barnaba of which the Guild was the patron. The painting shows the Madonna enthroned with Saint Catherine of Alexandria, Saint Augustine, Saint Barnabas, Saint John the Baptist, Saint Ignatius and Saint Michael.

Only four of the original seven small panel paintings of the altar's predella still remain, these depict scenes from the lives of the saints in the main altar painting; the probable center was the panel showing a scene of Christ's Passion.

The poor state of preservation of the painting is the result of attempts at restoring and over painting in the early 18th century. It was also enlarged and only in 1930 was it restored to its original size.

It must be pointed out that, on the steps of the throne, there is for the first time in history of painting an inscription in Italian. The line comes from Dante's Divine Comedy. This is the first evidence of Botticelli's interest in Dante's poetry.

According to a legend, Saint Augustine the Bishop, while he was thinking about the Holy Trinity, met a child on the beach who was attempting to use a spoon to transfer the waters of the ocean into a small hole. When Augustine explained to him that this was not possible, the child replied that it was far more foolish to try to find an explanation for the mystery of the Trinity.

The beginning of Botticelli's late period of creativity is marked by the painting Coronation of the Virgin with Angels and Saint John the Evangelist, Saint Augustine, Saint Jerome and Saint Eligius. This altarpiece was painted for the chapel belonging to the Guild of the Goldsmiths in the Church of San Marco in Florence. The chapel was dedicated to Saint Eligius. The fact that the altarpiece was commissioned by the Guild of Goldsmiths explains the generous employment of expensive gold; it was of course unthinkable that the goldsmiths be sparing with this material.

Since 1919 the painting is in the Uffizi together with the predella (five scenes painted on a single panel) but without the superb original frame. It used to be in such poor condition that for half a century it was not possible to exhibit the picture. Following extensive restoration, which mainly consisted of reattaching those pieces of paint that had become loose, it was possible to put the painting on show once more in 1990.

The four saints - John the Evangelist, the Fathers of the Church Saint Augustine and Saint Jerome, and Saint Eligius - are standing in a semicircle on a meadow. Behind them, on either side of a lake, is an extensive landscape. As is typical of Botticelli's economical and schematic composition, it is merely a decorative addition to the monumental figures. The coronation of the Virgin in a glory of seraphs and cherubs is all the more lavish. God the Father and the Virgin are enthroned on an airy carpet of clouds, setting them apart from the dancing groups of angels. Two artistic qualities become clear in this heavenly scene: Botticelli's exceptional feeling for the ornamental structuring of forms and his artistic inventiveness. He fits the heavenly aureole into the semicircular top of the picture, which reflects the domed architecture of the Eligius Chapel. He playfully groups the whirlwind round dance of the angels about the heavenly scene and this creates an illusion of depth.

Saint John was exiled to the Greek island of Patmos by the Roman Emperor Domitian (81-96). This is where he was believed to have written the Book of Revelations. Surrounded by the waves, the saint is sitting with his legs crossed on a bare rock and is writing down his visions.

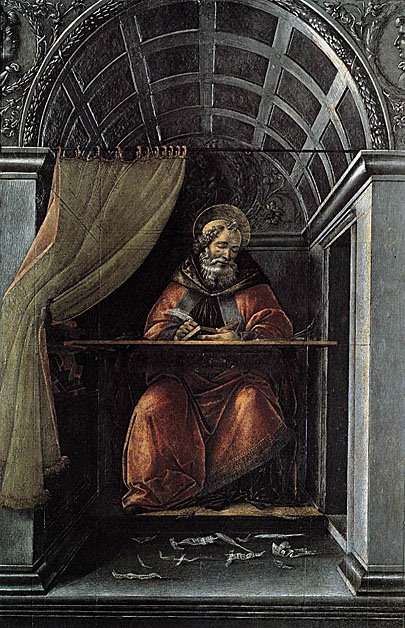

The scholar Bishop is sitting thoughtfully at his desk. Next to him, an open book is lying on the chest seat, and there is a pile of other manuscripts in the wall cupboard behind him. The divine light entering the room from the left is painted as a gold hatching. It appears to be inspiring the saint, for he is holding his hand to his chest in a gesture of great emotion.

The angel Gabriel has just made a sweeping entry into Mary's astonishingly bare chamber, and is kneeling reverently before her and raising his hand in blessing. The Virgin has stopped reading and is humbly bowing her head. There is a door in the center of the plain, gray walls, opening out onto a broad landscape.

Scantily clad in a red cloak, St Jerome is kneeling as a penitent on a bare rock and is holding a stone in his hand in order to castigate himself. The book lying next to him refers to his translation of the Bible, and the red cardinal s hat hanging from a branch to his sacred office.

According to legend, Saint Eligius shod a horse that was possessed by devils. He cut one of the horse's legs off, and after completing his work reattached it while making the sign of the Cross. The Devil, portrayed as a woman with horns, is watching the holy smith. A groom is having considerable difficulty controlling the impetuous horse.

The 1480's were Botticelli's most productive years. While he was one of the most desirable painters in Florence even before he left for Rome, by the time he returned, after the large project working on the frescoes for the Pope, his reputation was firmly established. He gained commissions from the families in high society who increasingly chose classical themes for the luxurious decoration of their town houses.

In this period Botticelli created the large format mythological and allegorical paintings (Primavera, Pallas and the Centaur, Venus and Mars, Birth of Venus) that are some of his best-known works. These paintings constitute an unusually homogenous group, not only in pictorial content but also in stylistic expression. Despite research by art historians that has continued for over a century, they are still a mystery. The difficulty in deciphering them lies in the fact that there are no known predecessors, nor can their pictorial programs be conclusively derived from written sources. Rather, they are a blending of classical and modern sources. These paintings were not originally intended to be seen by a larger audience, but were hung in private rooms, tailored precisely to the requirements of the client and reflecting their particular interests in the classical body of thought. The study of antiquity was particularly encouraged in the humanist circle associated with the Medici's, and Botticelli's patrons also belonged to it.

The series of mythological paintings is brought to a close by two frescoes which originally decorated the country villa of Lemmi, near Florence.

Such large format paintings were nothing new in high-ranking private residences. The Primavera is, however, special in that it is one of the first surviving paintings from the post-classical period which depicts classical gods almost naked and life-size. Some of the figures are based on ancient sculptures. These are, however, not direct copies but are translated into Botticelli's own unconventional formal language: slender figures whose bodies at times seem slightly too long. Above all it is the women's domed stomachs that demonstrate the contemporary ideal of beauty.

Venus is standing in the centre of the picture, set slightly back from the other figures. Above her, Cupid is aiming one of his arrows of love at the Three Graces, who are elegantly dancing a roundel. The garden of the goddess of love is guarded by Mercury on the left. Mercury, who is lightly clad in a red cloak covered with flames, is wearing a helmet and carrying a sword, clearly characterizing him as the guardian of the garden. The messenger of the gods is also identified by means of his winged shoes and the caduceus staff which he used to drive two snakes apart and make peace; Botticelli has depicted the snakes as winged dragons. From the right, Zephyr, the god of the winds, is forcefully pushing his way in, in pursuit of the nymph Chloris. Next to her walks Flora, the goddess of spring, who is scattering flowers.

Various interpretations of the scene exist. Leaving aside the suppositions there remains the profoundly humanistic nature of the painting, a reflection of contemporary cultural influences and an expression of many contemporary texts.

One source for this scene is Ovid's Fasti, a poetic calendar describing Roman festivals. For the month of May, Flora tells how she was once the nymph Chloris, and breathes out flowers as she does so. Aroused to a fiery passion by her beauty, Zephyr, the god of the wind, follows her and forcefully takes her as his wife. Regretting his violence, he transforms her into Flora, his gift gives her a beautiful garden in which eternal spring reigns. Botticelli is depicting two separate moments in Ovid's narrative, the erotic pursuit of Chloris by Zephyr and her subsequent transformation into Flora. This is why the clothes of the two women, who also do not appear to notice each other, are being blown in different directions. Flora is standing next to Venus and scattering roses, the flowers of the goddess of love. In his philosophical didactic poem, De Rerum Natura the classical writer Lucretius celebrated both goddesses in a single spring scene. As the passage also contains other figures in Botticelli's group, it is probably one of the main sources for the painting: "Spring-time and Venus come,/ And Venus' boy, the winged harbinger, steps on before,/ And hard on Zephyr's foot-prints Mother Flora,/ Sprinkling the ways before them, filleth all/ With colors and with odors excellent."

According to the inventory of 1499 which lists the property of Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco, the painting Pallas and the Centaur hung above a door in the same room as the Primavera. Its bare landscape focuses one's gaze on the two figures. A centaur has trespassed on forbidden territory. This lusty being, half horse and half man, is being brought under control by a guard armed with a shield and halberd, and she has grabbed him by the hair. The woman has been identified both as the goddess Pallas Athena and the Amazon Camilla, chaste heroine of Virgil's Aeneid. What is undisputed is the moral content of the painting, in which virtue is victorious over sensuality.

This painting marks the end of Botticelli's Medicean period, from this point onwards the subject-matter of his paintings changes and becomes increasingly religious.

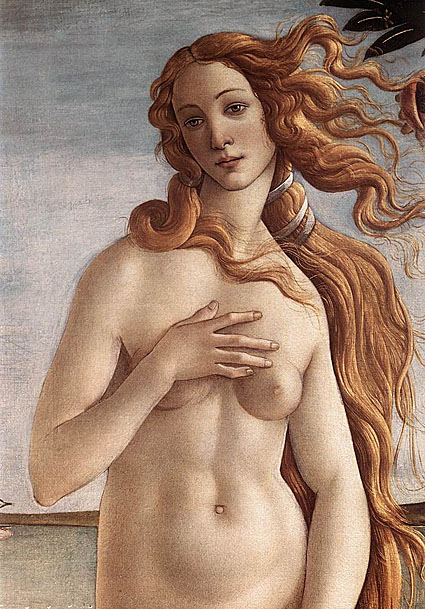

The god of the winds, Zephyr, and the breeze Aura are in a tight embrace, and are gently driving Venus towards the shore with their breath. She is standing naked on a golden shining shell, which reaches the shore floating on rippling waves. There, a Hora of Spring is approaching on the tips of her toes, in a graceful dancing motion, spreading out a magnificent cloak for her. Venus rises with her marble-colored carnations above the ocean next to her, like a statue. Her hair, which is playfully fluttering around her face in the wind, is given a particularly fine sheen by the use of fine golden strokes. The unapproachable gaze under the heavy lids gives the goddess an air of cool distance. The rose is supposed to have flowered for the first time when Venus was born. For that reason, gentle rose-colored flowers are blowing around Zephyr and Aura in the wind.

The goddess of love, one of the first non-biblical female nudes in Italian art, is depicted in accordance with the classical Venus pudica. She is, however, as little a precise copy of her prototype as the painting is an exact illustration of Poliziano's poetry. The group comprising Venus and the Hora of spring demonstrates Botticelli's flexible use of Christian means of depiction.

It is uncertain who commissioned the painting. In the first half of the 16th century, it was kept in the Castello villa, owned by the descendants of Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de' Medici. However, it was never mentioned in inventories of his property. It is, though, extremely likely that the Birth of Venus was commissioned for a country seat. In contrast to the Primavera, the painting is painted on canvas. This was a medium normally chosen for paintings that were destined to decorate country houses, for canvas was less expensive and easier to transport than wooden panels.

The goddess of love, who is clothed in a costly gown, is watching over the sleeping naked Mars, while little fauns are playing mischievously with the weapons and armor of the god of war. Botticelli's theme is that the power of love can defeat the warrior's strength. The boisterous little fauns that form part of the retinue of Bacchus, the god of wine, are depicted by Botticelli, in accordance with ancient tradition, with little goats' legs, horns and tails. The Triton's shell with which one of the fauns is blowing into Mars' ear was used in classical times as a hunting horn.

Botticelli let himself be inspired by classical models. The mischievous little satyrs playing practical jokes nearby were probably suggested by a description of the famous classical painting Wedding of Alexander the Great to the Persian princess Roxane, written by the Greek poet Lucian. Botticelli replaced the amoretti which Lucian describes playing with Alexander's weapons with little satyrs. His painting is one of the earliest examples in Renaissance painting to depict these boisterous and lusty hybrids in this form. They are playing with the war god's helmet, lance and cuirass. One of them is cheekily blowing into his ear through a sea shell. But he has as little chance of disturbing the sleeping god as the wasps nest to the right of his head. The wasps may be a reference to the clients who commissioned the painting. They are part of the coat of arms of the Vespucci family, whose name derives from vespa, Italian for wasp. Given that its theme is love, this painting was possibly also commissioned on the occasion of a wedding.

It is supposed the frescoes were executed to commemorate the marriage of Lorenzo Tornabuoni and Giovanna degli Albizzi.

The frescoes are in a very poor state of preservation, because they were damaged when taken down from the wall. Two of the three fragments found were transferred to canvas and later sold to the Louvre in Paris. The two compositions were originally separated only by a window.

One of the fragments probably represents Venus and the Three Graces Presenting Gifts to a Young Woman, the other A Young Man Being Introduced to the Seven Liberal Arts.

On this painting there is a strange lack of certainty as to the identity of the group of four young classically dressed women, who are gracefully stepping towards a young woman in front of the splashing spring in order to bring her gifts. They may be Venus and the Three Graces, symbolizing chastity, beauty and love.

In the 1480's Botticelli gained commissions from the families in high society. Increasingly they chose classical themes for the luxurious decoration of their town houses, but they also included some from contemporary literature. In order to be able to carry out his multiple commissions, Botticelli had to work together with other painters as well as members of his own workshop. The four-part Nastagio degli Onesti cycle, Botticelli's reworking of a novella in Boccaccio's Decameron, was produced with the aid of Bartolomeo di Giovanni, an artist who had also worked for Ghirlandaio.

Nastagio degli Onesti, a knight from Ravenna, whose beloved initially refused to marry him, finally weds her after all. First of all, however, he must remind her of the eternal agony in hell of another merciless woman, one who had also refused marriage, her rejected lover had to pursue her until he had caught up with her, killed her, torn out her heart and intestines and fed them to his dogs.

The occasion for which Botticelli's patron, Antonio Pucci, ordered these pictures was the wedding of his son Giannozzo to Lucrezia Bini. The paintings originally decorated a room in the old Pucci palace and were set into a 'spalliera', a type of wall paneling. Botticelli was the first to adapt Boccaccio's story for panel painting, and his pictures, which were freely copied shortly afterwards, were in many respects exemplary for spalliera painting.

While the first two paintings restricted themselves to the events in the novella, the third and fourth panels translated the story, which takes place in Ravenna, to the situation in Florence. The father of the bridegroom, Antonio Pucci, is portrayed on the third painting amidst the guests, and on the fourth is even shown in a group of other prominent public figures in the city. Above each of the banqueting tables are Florentine family coats of arms, on the left that of the father of the bridegroom, on the right that of the newly-founded Pucci-Bini family. In the centre, the Medici coat of arms is emblazoned. It is probable that Lorenzo de' Medici arranged the marriage.

_ca_1483.jpg)

_ca_1483.jpg)

_ca_1483.jpg)

_ca_1483.jpg)

A considerable contribution to the execution of this panel by Jacopo del Sellaio is assumed.

The ability to give the written word visual form in painted pictures is also something that sets Botticelli's later scenic works apart. The small painting of the Calumny of Apelles was not a commissioned work. It is not certain why Botticelli created it, executed with the fineness of a miniature. Many interpretations have been suggested for the painting, without any of them becoming entirely clear.

Botticelli also set dramatic scenes amidst a lavishly decorated architecture in the paintings of the Story of Virginia and The Story of Lucretia. It is thought that the two panels formed a pair. The Ancient Roman writer Livy, who told the stories of the two Roman heroines, also connected Virginia and Lucretia with each other.

Saint Zenobius, Florence's first Bishop, was particularly venerated. In the 15th century an active cult dedicated to this local saint, who died in 417, was revived. Botticelli created a four-part cycle of paintings in which he depicted the deeds and miracles of Saint Zenobius. A description of the life of the saint, published in 1487, may well have been one of the artist's sources.

In his painting, Botticelli kept the scenic structure of the composition of the figures to Lucian's description, and created a lavishly decorated architectural backdrop for them.

An innocent man is dragged before the king's throne by the personifications of Calumny, Malice, Fraud and Envy. They are followed to one side by Remorse as an old woman, turning to face the naked Truth, who is pointing towards heaven. The nakedness of Truth places her in a relationship with the innocent youth, whose folded hands are also an appeal to a higher power.

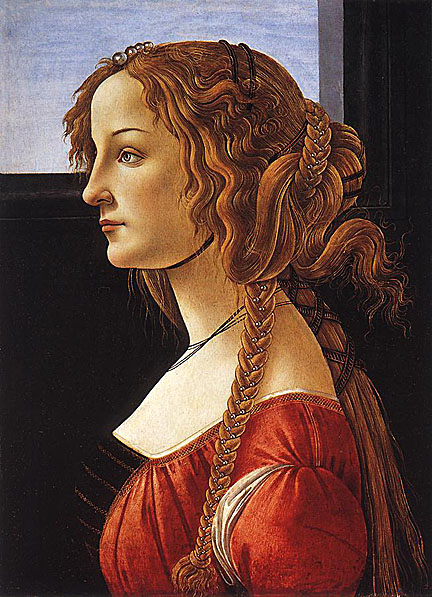

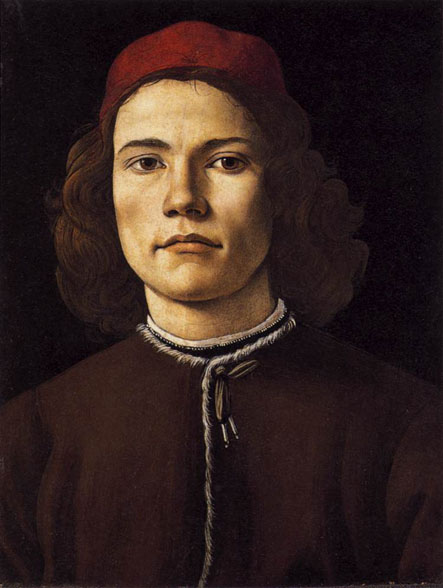

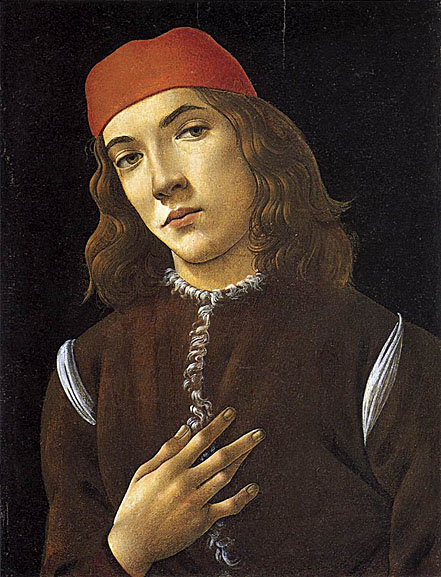

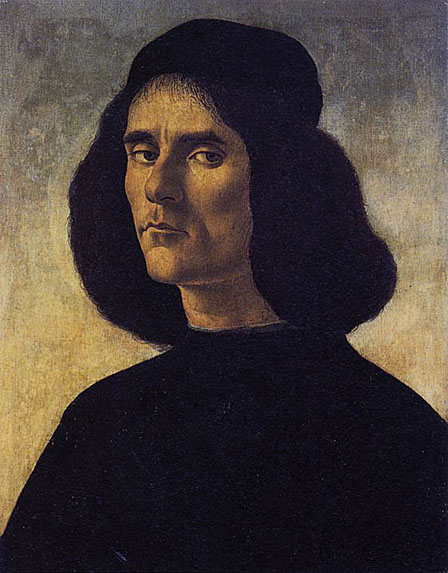

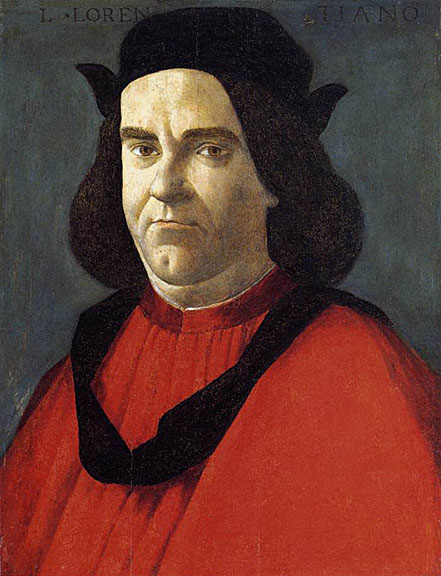

Botticelli established a reputation as a portraitist in the 1470's. It is evidenced by several portraits from this period. Particular attention is drawn to the Portrait of a Man holding up towards the observer a medallion bearing the likeness of Cosimo Medici the Elder, as well as the portraits of Giuliano de' Medici, the younger brother of Lorenzo the Magnificent. The early portraits typically show their subjects in a three-quarter view, a new ambitious form of portrait which did not become widespread in Florence until about 1470.

Botticelli's late portraits, similarly to the secular stories like the Calumny of Apelles, reveal the stylistic change in his work. Now he no longer added landscape vistas or the view of inner rooms, as he had done in his earlier portraits. Instead he reduced the background to a surface of one color alone, in order that the observer's attention not be distracted from the depicted person. This reductive manner of painting, sometimes almost ascetic in its effect, reflects Botticelli's breaking away from the sumptuously ornamented, decorative style in which he previously treated his pictorial subjects.

The sitter of the portrait is probably Gianlorenzo de' Medici, and it could very well be Botticelli's first commissioned work, and from the hair and the clothes, the portrait must date from no later than 1469.

The lock of hair coming loose from her bun gives a more spontaneous feeling to this severe profile portrait. The half length figure is slightly to the left of the center of the picture. Behind her is a dark window frame and it contrasts with the gentle flow other contours. The attribution of the work to Botticelli is disputed.

The picture of this unidentified young man is one of the most unusual portraits of the Early Renaissance. The man is gazing at the observer and is holding up a medal bearing the profile of the head of Cosimo de' Medici, who died in 1464. Botticelli set the medal into the painting as a gilded plaster cast.

The painting is a a half length portrait in front of an extensive light landscape with a river, and the man's head projects above the horizon. The light, which falls on the subject from the left, clearly shapes his striking features, and there are stronger shadows on the side of his face closer to the observer. The poor drawing of his hands makes the experimental nature of this portrait more than clear. It is one of the earliest Italian portraits to make the hands a part of the portrait's theme.

The commemorative medal of Cosimo dates from about 1465-70 and has given rise to an entire series of suggestions concerning the identity of the man depicted. So far it has not been possible to give a definitive answer to the question whether this is a close relative or supporter of the Medici's, or perhaps the man who created the medal.

The portrait of Giuliano de' Medici (1453-1478), the younger brother of Lorenzo the Magnificent, is turned to the right and there are no less than three known version of it. Giuliano had been killed on 26 April 1478, while mass was being celebrated in Florence Cathedral, during the course of an attack made by the Pazzi family, who were the Medicis' rivals for power and banking business.

Botticelli placed this portrait in a most skilful relationship with the framing forms. In the background, one window shutter is open, allowing us to see the blue sky, and the other is behind the subjects bowed head. The dove by the window jamb is a symbol of loyalty, and for this reason it is thought that Giuliano commissioned this portrait following the death of his courtly love, Simonetta.

Source: Web Gallery of Art

Source: Art Renewal Center

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.