1483 - 1520

Raphael (his full name Raffaello Sanzi or Santi), was an Italian painter and architect of the Italian High Renaissance. Raphael is best known for his Madonnas and for his large figure compositions in the Vatican in Rome. His work is admired for its clarity of form and ease of composition and for its visual achievement of the Neoplatonic ideal of human greatness.

Early years at Urbino

Raphael was the son of Giovanni Santi and Magia di Battista Ciarla; his mother died in 1491. His father was, according to the 16th-century artist and biographer Giorgio Vasari, a painter "of no great merit." He was, however, a man of culture who was in constant contact with the advanced artistic ideas current at the court of Urbino. He gave his son his first instruction in painting, and, before his death in 1494, when Raphael was 11; he had introduced the boy to humanistic philosophy at the court.

Urbino had become a center of culture during the rule of Duke Federico da Montefeltro, who encouraged the arts and attracted the visits of men of outstanding talent, including Donato Bramante, Piero della Francesca, and Leon Battista Alberti, to his court. Although Raphael would be influenced by major artists in Florence and Rome, Urbino constituted the basis for all his subsequent learning. Furthermore, the cultural vitality of the city probably stimulated the exceptional precociousness of the young artist, who, even at the beginning of the 16th century, when he was scarcely 17 years old, already displayed an extraordinary talent.

Apprenticeship at Perugia

The date of Raphael's arrival in Perugia is not known, but several scholars place it in 1495. The first record of Raphael's activity as a painter is found there in a document of Dec. 10, 1500, declaring that the young painter, by then called a "master," was commissioned to help paint an altarpiece to be completed by Sept. 13, 1502. It is clear from this that Raphael had already given proof of his mastery, so much so that between 1501 and 1503 he received a rather important commission - to paint the Coronation of the Virgin for the Oddi Chapel in the church of San Francesco, Perugia (and now in the Vatican Museum, Rome). The great Umbrian master Pietro Perugino was executing the frescoes in the Collegio del Cambio at Perugia between 1498 and 1500, enabling Raphael, as a member of his workshop, to acquire extensive professional knowledge.

In addition to this practical instruction, Perugino's calmly exquisite style also influenced Raphael. The Giving of the Keys to St Peter, painted in 1481-82 by Perugino for the Sistine Chapel of the Vatican Palace in Rome, inspired Raphael's first major work, The Marriage of the Virgin (1504; Brera Gallery, Milan). Perugino's influence is seen in the emphasis on perspectives, in the graded relationships between the figures and the architecture, and in the lyrical sweetness of the figures. Nevertheless, even in this early painting, it is clear that Raphael's sensibility was different from his teacher's. The disposition of the figures is less rigidly related to the architecture, and the disposition of each figure in relation to the others is more informal and animated. The sweetness of the figures and the gentle relation between them surpasses anything in Perugino's work.

Three small paintings done by Raphael shortly after The Marriage of the Virgin - Vision of a Knight, Three Graces, and St Michael - are masterful examples of narrative painting, showing, as well as youthful freshness, a maturing ability to control the elements of his own style. Although he had learned much from Perugino, Raphael by late 1504 needed other models to work from; it is clear that his desire for knowledge was driving him to look beyond Perugia.

Move to Florence

Vasari vaguely recounts that Raphael followed the Perugian painter Bernardino Pinturicchio to Siena and then went on to Florence, drawn there by accounts of the work that Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo were undertaking in that city. By the autumn of 1504 Raphael had certainly arrived in Florence. It is not known if this was his first visit to Florence, but, as his works attest, it was about 1504 that he first came into substantial contact with this artistic civilization, which reinforced all the ideas he had already acquired and also opened to him new and broader horizons. Vasari records that he studied not only the works of Leonardo, Michelangelo, and Fra Bartolomeo, who were the masters of the High Renaissance, but also "the old things of Masaccio," a pioneer of the naturalism that marked the departure of the early Renaissance from the Gothic.

Still, his principal teachers in Florence were Leonardo and Michelangelo. Many of the works that Raphael executed in the years between 1505 and 1507, most notably a great series of Madonnas including The Madonna of the Goldfinch (c. 1505; Uffizi Gallery, Florence), the Madonna del Prato (c. 1505; Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna), the Esterhzy Madonna (c. 1505-07; Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest), and La Belle Jardiniere (c. 1507; Louvre Museum, Paris), are marked by the influence of Leonardo, who since 1480 had been making great innovations in painting. Raphael was particularly influenced by Leonardo's Madonna and Child with St. Anne pictures, which are marked by an intimacy and simplicity of setting uncommon in 15th-century art. Raphael learned the Florentine method of building up his composition in depth with pyramidal figure masses; the figures are grouped as a single unit, but each retains its own individuality and shape. A new unity of composition and suppression of inessentials distinguishes the works he painted in Florence. Raphael also owed much to Leonardo's lighting techniques; he made moderate use of Leonardo's chiaroscuro (i.e., strong contrast between light and dark), and he was especially influenced by his sfumato (i.e., use of extremely fine, soft shading instead of line to delineate forms and features). Raphael went beyond Leonardo, however, in creating new figure types whose round, gentle faces reveal uncomplicated and typically human sentiments but raised to a sublime perfection and serenity.

In 1507 Raphael was commissioned to paint the Deposition of Christ that is now in the Borghese Gallery in Rome. In this work, it is obvious that Raphael set himself deliberately to learn from Michelangelo the expressive possibilities of human anatomy. But Raphael differed from Leonardo and Michelangelo, who were both painters of dark intensity and excitement, in that he wished to develop a calmer and more extroverted style that would serve as a popular, universally accessible form of visual communication.

Last years in Rome

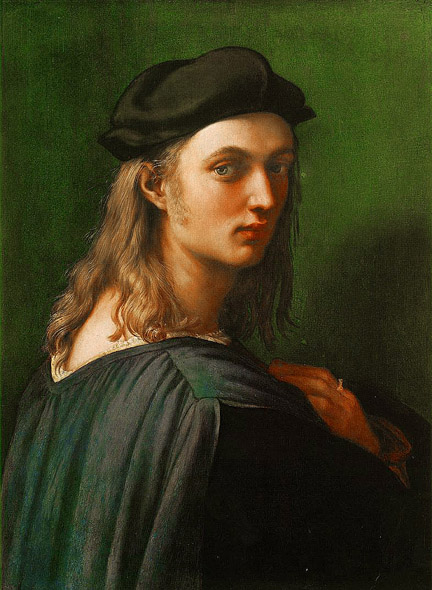

Raphael was called to Rome toward the end of 1508 by Pope Julius II at the suggestion of the architect Donato Bramante. At this time Raphael was little known in Rome, but the young man soon made a deep impression on the volatile Julius and the papal court, and his authority as a master grew day by day. Raphael was endowed with a handsome appearance and great personal charm in addition to his prodigious artistic talents, and he eventually became so popular that he was called "the prince of painters."

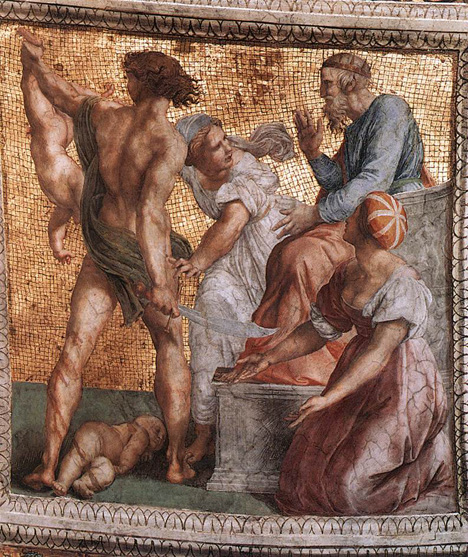

Raphael spent the last 12 years of his short life in Rome. They were years of feverish activity and successive masterpieces. His first task in the city was to paint a cycle of frescoes in a suite of medium-sized rooms in the Vatican papal apartments in which Julius himself lived and worked; these rooms are known simply as the Stanze. The Stanza della Segnatura (1508-11) and Stanza d'Eliodoro (1512-14) were decorated practically entirely by Raphael himself; the murals in the Stanza dell'Incendio (1514-17), though designed by Raphael, were largely executed by his numerous assistants and pupils.

The decoration of the Stanza della Segnatura was perhaps Raphael's greatest work. Julius II was a highly cultured man who surrounded himself with the most illustrious personalities of the Renaissance. He entrusted Bramante with the construction of a new basilica of St. Peter to replace the original 4th-century church; he called upon Michelangelo to execute his tomb and compelled him against his will to decorate the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel; and, sensing the genius of Raphael, he committed into his hands the interpretation of the philosophical scheme of the frescoes in the Stanza della Segnatura. This theme was the historical justification of the power of the Roman Catholic Church through Neoplatonic philosophy.

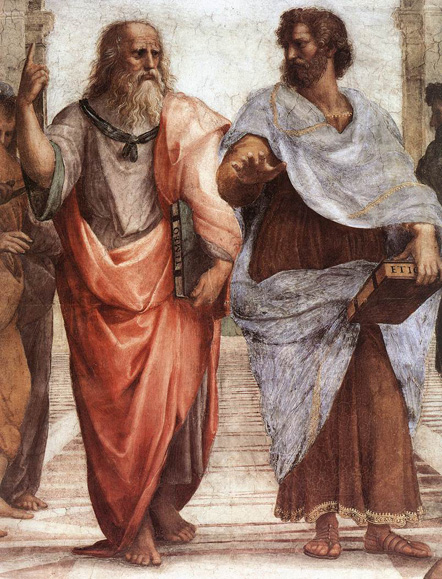

The four main fresco walls in the Stanza della Segnatura are occupied by the Disputa and the School of Athens on the larger walls and the Parnassus and Cardinal Virtues on the smaller walls. The two most important of these frescoes are the Disputa and the School of Athens. The Disputa, showing a celestial vision of God and his prophets and apostles above a gathering of representatives, past and present, of the Roman Catholic Church, equates through its iconography the triumph of the church and the triumph of truth. The School of Athens is a complex allegory of secular knowledge, or philosophy, showing Plato and Aristotle surrounded by philosophers, past and present, in a splendid architectural setting; it illustrates the historical continuity of Platonic thought. The School of Athens is perhaps the most famous of all Raphael's frescoes, and one of the culminating artworks of the High Renaissance. Here Raphael fills an ordered and stable space with figures in a rich variety of poses and gestures, which he controls in order to make one group of figures lead to the next in an interweaving and interlocking pattern, bringing the eye to the central figures of Plato and Aristotle at the converging point of the perspective of space. The space in which the philosophers congregate is defined by the pilasters and barrel vaults of a great basilica that is based on Bramante's design for the new St Peter's in Rome. The general effect of the fresco is one of majestic calm, clarity, and equilibrium.

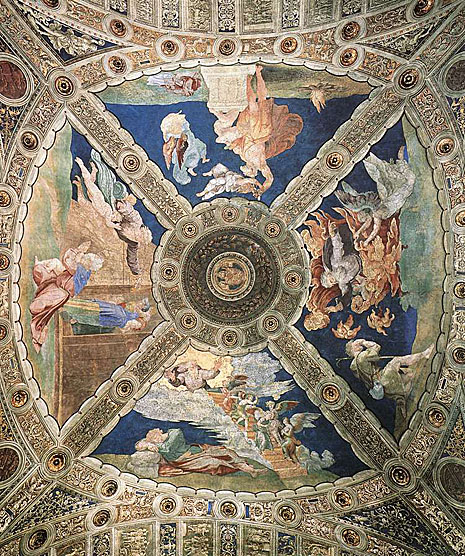

About the same time, probably in 1511, Raphael painted a more secular subject, the Triumph of Galatea in the Villa Farnesina in Rome; this work was perhaps the High Renaissance's most successful evocation of the living spirit of classical antiquity. Meanwhile, Raphael's decoration of the papal apartments continued after the death of Julius in 1513 and into the succeeding pontificate of Leo X until 1517. In contrast to the generalized allegories in the Stanza della Segnatura, the decorations in the second room, the Stanza d'Eliodoro, portray specific miraculous events in the history of the Christian Church. The four principal subjects are The Expulsion of Heliodorus from the Temple, The Miracle at Bolsena, The Liberation of St Peter, and Leo I Halting Attila. These frescoes are deeper and richer in color than are those in the earlier room, and they display a new boldness on Raphael's part in both their dramatic subjects and their unusual effects of light. The Liberation of St Peter, for example, is a night scene and contains three separate lighting effects - moonlight, the torch carried by a soldier, and the supernatural light emanating from an angel. Raphael delegated his assistants to decorate the third room, the Stanze dell'Incendio, with the exception of one fresco, the Fire in the Borgo, in which his pursuit of more dramatic pictorial incidents and his continuing study of the male nude are plainly apparent.

The Madonnas that Raphael painted in Rome show him turning away from the serenity and gentleness of his earlier works in order to emphasize qualities of energetic movement and grandeur. His Alba Madonna (1508; National Gallery, Washington) epitomizes the serene sweetness of the Florentine Madonnas but shows a new maturity of emotional expression and supreme technical sophistication in the poses of the figures. It was followed by the Madonna di Foligno (1510; Vatican Museum) and the Sistine Madonna (1513; Gemaldegalerie, Dresden), which show both the richness of colour and new boldness in compositional invention typical of Raphael's Roman period. Some of his other late Madonnas, such as the Madonna of Francis I (Louvre), are remarkable for their polished elegance. Besides his other accomplishments, Raphael became the most important portraitist in Rome during the first two decades of the 16th century. He introduced new types of presentation and new psychological situations for his sitters, as seen in the portrait of Leo X with Two Cardinals (1517-19; Uffizi, Florence). Raphael's finest work in the genre is perhaps the Portrait of Baldassare Castiglione (1516; Louvre), a brilliant and arresting character study.

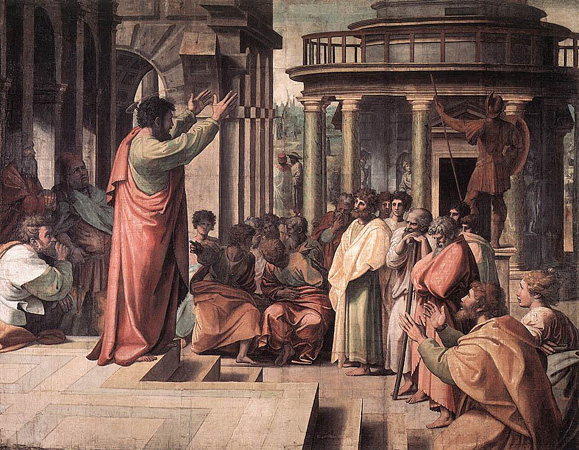

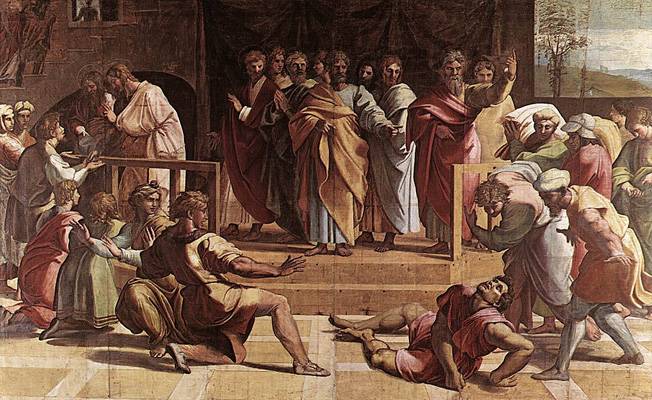

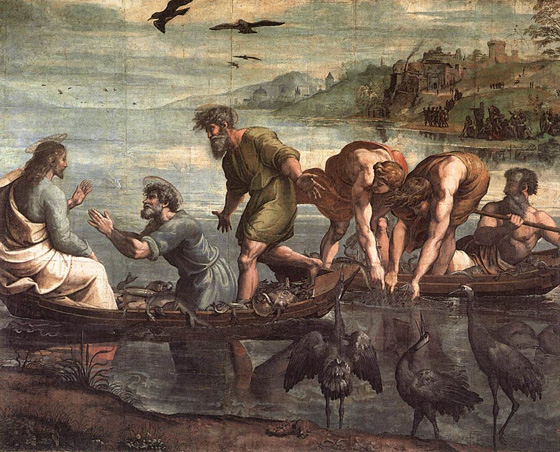

Leo X commissioned Raphael to design 10 large tapestries to hang on the walls of the Sistine Chapel. Seven of the ten cartoons (full-size preparatory drawings) were completed by 1516, and the tapestries woven after them were hung in place in the chapel by 1519. The tapestries themselves are still in the Vatican, while seven of Raphael's original cartoons are in the British royal collection and are on view at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. These cartoons represent Christ's Charge to Peter, The Miraculous Draught of Fishes, The Death of Ananias, The Healing of the Lame Man, The Blinding of Elymas, The Sacrifice at Lystra, and St Paul Preaching at Athens. In these pictures Raphael created prototypes that would influence the European tradition of narrative history painting for centuries to come. The cartoons display Raphael's keen sense of drama, his use of gestures and facial expressions to portray emotion, and his incorporation of credible physical settings from both the natural world and that of ancient Roman architecture.

While he was at work in the Stanza della Segnatura, Raphael also did his first architectural work, designing the church of Sant' Eligio degli Orefici. In 1513 the banker Agostino Chigi, whose Villa Farnesina Raphael had already decorated, commissioned him to design and decorate his funerary chapel in the church of Santa Maria del Popolo. In 1514 Leo X chose him to work on the basilica of St Peter's alongside Bramante; and when Bramante died later that year, Raphael assumed the direction of the work, transforming the plans of the church from a Greek, or radial, to a Latin, or longitudinal, design.

Raphael was also a keen student of archaeology and of ancient Greco-Roman sculpture, echoes of which are apparent in his paintings of the human figure during the Roman period. In 1515 Leo X put him in charge of the supervision of the preservation of marbles bearing valuable Latin inscriptions; two years later he was appointed commissioner of antiquities for the city, and he drew up an archaeological map of Rome. Raphael had by this time been put in charge of virtually all of the papacy's various artistic projects in Rome, involving architecture, paintings and decoration, and the preservation of antiquities.

Raphael's last masterpiece is the Transfiguration (commissioned in 1517), an enormous altarpiece that was unfinished at his death and completed by his assistant Giulio Romano. It now hangs in the Vatican Museum. The Transfiguration is a complex work that combines extreme formal polish and elegance of execution with an atmosphere of tension and violence communicated by the agitated gestures of closely crowded groups of figures. It shows a new sensibility that is like the prevision of a new world, turbulent and dynamic; in its feeling and composition it inaugurated the Mannerist movement and tends toward an expression that may even be called Baroque.

Raphael died on his 37th birthday. His funeral mass was celebrated at the Vatican, his Transfiguration was placed at the head of the bier, and his body was buried in the Pantheon in Rome.

The School of Athens is a depiction of philosophy. The scene takes place in classical times, as both the architecture and the garments indicate. Figures representing each subject that must be mastered in order to hold a true philosophic debate - astronomy, geometry, arithmetic, and solid geometry - are depicted in concrete form. The arbiters of this rule, the main figures, Plato and Aristotle, are shown in the centre, engaged in such a dialogue.

The School of Athens represents the truth acquired through reason. Raphael does not entrust his illustration to allegorical figures, as was customary in the 14th and 15th centuries. Rather, he groups the solemn figures of thinkers and philosophers together in a large, grandiose architectural framework. This framework is characterized by a high dome, a vault with lacunar ceiling and pilasters. It is probably inspired by late Roman architecture or - as most critics believe - by Bramante's project for the new St Peter's which is itself a symbol of the synthesis of pagan and Christian philosophies.

The figures who dominate the composition do not crowd the environment, nor are they suffocated by it. Rather, they underline the breadth and depth of the architectural structures. The protagonists - Plato, represented with a white beard (some people identify this solemn old man with Leonardo da Vinci) and Aristotle - are both characterized by a precise and meaningful pose. Raphael's descriptive capacity, in contrast to that visible in the allegories of earlier painters, is such that the figures do not pay homage to, or group around the symbols of knowledge; they do not form a parade. They move, act, teach, discuss and become excited.

The painting celebrates classical thought, but it is also dedicated to the liberal arts, symbolized by the statues of Apollo and Minerva. Grammar, Arithmetic and Music are personified by figures located in the foreground, at left. Geometry and Astronomy are personified by the figures in the foreground, at right. Behind them stand characters representing Rhetoric and Dialectic. Some of the ancient philosophers bear the features of Raphael's contemporaries. Bramante is shown as Euclid (in the foreground, at right, leaning over a tablet and holding a compass). Leonardo is, as we said, probably shown as Plato. Francesco Maria Della Rovere appears once again near Bramante, dressed in white. Michelangelo, sitting on the stairs and leaning on a block of marble, is represented as Heraclitus. A close examination of the intonaco shows that Heraclitus was the last figure painted when the fresco was completed, in 1511. The allusion to Michelangelo is probably a gesture of homage to the artist, who had recently unveiled the frescoes of the Sistine Ceiling. Raphael - at the extreme right, with a dark hat - and his friend, Sodoma, are also present (they exemplify the glorification of the fine arts and they are posed on the same level as the liberal arts).

The fresco achieved immediate success. Its beauty and its thematic unity were universally accepted. The enthusiasm with which it was received was not marred by reservations, as was the public reaction to the Sistine Ceiling.

In the center of the painting, in front of the painting's vanishing point, are the two undisputed main subjects, Plato on the left and his student Aristotle on the right. Both figures are holding copies of their own books in their left hands. Plato is holding Timaeus and Aristotle is holding his Nicomachean Ethics. In addition, the two figures are gesturing in different directions. Plato has his right arm pointing to the heavens, which is a reference to Plato's ideas of the The Forms. In contrast, Aristotle gestures to the earth, representing his belief in knowledge through empirical observation and experience.

The building is in the shape of a Greek Cross, which some have suggested was intended to show a harmony between pagan philosophy and Christian theology. The architecture of the building was inspired by the work of Bramante, who according to Vasari helped Raphael with the architecture in the picture. Some have suggested that the building itself was intended to be an advance view of St. Peter's Basilica. There are two sculptures in the background. The one on the left is the god Apollo holding a lyre. Apollo is the god of the sun, medicine/healing, light, truth, archery, and music. The sculpture on the right is Athena, in her Roman guise as Minerva. Athena was the goddess of wisdom.

After the master's death in 1520, Penni worked together with other members of Raphael's workshop to finish the commission to decorate with frescoes the rooms that are now known as the Stanze di Raffaello, in the Apostolic Palace in the Vatican. The Baptism of Constantine is located in the Sala di Costantino ("Hall of Constantine"). In the painting emperor Constantine I is seen shortly before his death, kneeling down to receive the sacrament from Pope Sylvester I in the Baptistery of the Lateran. The painter has given Sylvester the traits of Clement VII, the Pope who had ordered the frescoes to be finished, after the work was interrupted during the papacy of Hadrian VI.

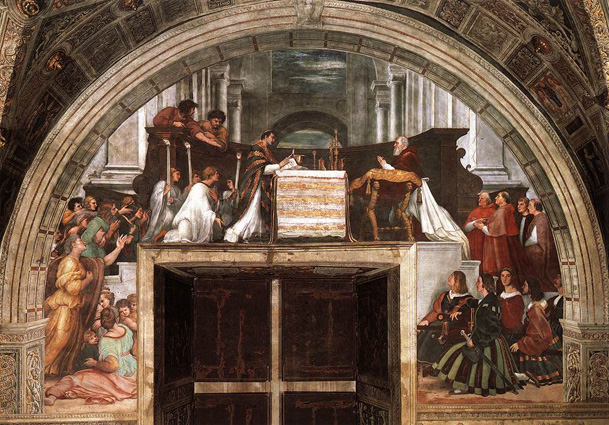

The Coronation of Charlemagne is a painting by the workshop of the Italian Renaissance artist Raphael. Though it is believed that Raphael did make the designs for the composition, the fresco was probably painted by Gianfrancesco Penni or Giulio Romano. The painting was part of Raphael's commission to decorate the rooms that are now known as the Stanze di Raffaello, in the Apostolic Palace in the Vatican. It is located in the room that was named after The Fire in the Borgo, the Stanza dell'incendio del Borgo. The painting shows how Charlemagne was crowned Imperator Romanorum by Pope Leo III (pontiff from 795 to 816) on Christmas Evening, 800. It is quite likely that the fresco refers to the Concordat of Bologna, negotiated between the Holy See and the kingdom of France in 1515, since Leo III is in fact a portrait of Leo X and Charlemagne a portrait of Francis I.

The Battle of Ostia is a painting by the workshop of Raphael. The painting was also part of Raphael's commission to decorate the rooms that are now known as the Stanze di Raffaelloin the Apostolic Palace in the Vatican. It was inspired by the naval battle fought in 849 between the Saracens of Sicily and Southern Italy and a Christian League of Papal, Neapolitan and Gaetan ships. In the painting Pope Leo IV, with the features of Pope Leo X, is giving thanks after the Arab ships were destroyed by a storm.

The Fire in the Borgo is a painting by the workshop of the Italian renaissance artist Raphael. Though it is assumed that Raphael did make the designs for the complex composition, the fresco was most likely painted by his assistant Giulio Romano. The painting was part of Raphael's commission to decorate the rooms that are now known as the Stanze di Raffaello, in the Apostolic Palace in the Vatican. It is located in the room that was named after it, the Stanza dell'incendio del Borgo ("The Room of the Fire in the Borgo").

The Fire in the Borgo shows an event that is documented in the Liber Pontificalis / Latin Text: a fire that broke out in the Borgo in Rome in 847 CE. According to legend, Pope Leo IV contained the fire with his benediction. The young man with an old man on his back in the foreground is an echo of the classical theme of Aeneas carrying his father Anchises from the fires of Troy; it is therefore an allusion to the traditional idea that Rome was the new Troy.

The Meeting of Leo the Great and Attila is a fresco by the Italian Renaissance artist Raphael and his assistant Giulio Romano. It was painted in 1514 as part of Raphael's commission to decorate the rooms in the Apostolic Palace in the Vatican.

The painting depicts the meeting between the Pope Leo I and Attila the Hun, and includes the images of Saint Peter and Saint Paul in the sky bearing swords. Initially, Raphael depicted Leo I with the face of Pope Julius II but after Julius' death, Raphael changed the painting to resemble the new pope, Leo X.

This group portrait (which created a sensation, notwithstanding the existence of precedents) is focused on the central figure of the Pope. The two Cardinals, Luigi de' Rossi on Leo's right and Giulio de' Medici on his left, act as a royal escort. An illuminated prayer book lies open on the table in front of Pope Leo. On the same table rests a finely carved bell. Both objects undoubtedly reveal the exquisite tastes of the Pope who was an active patron of the arts.

Perhaps those who connect Raphael's name only with beautiful Madonnas and idealized figures from the classical world may even be surprised to see this portrait. There is nothing idealized in the slightly puffed head of the near-sighted Pope, who has just examined an old manuscript (somewhat similar in style and period to the Queen Mary's Psalter). The velvets and damasks in their various rich tones add to the atmosphere of pomp and power, but one can well imagine that these men are not at ease. These were troubled times, for at the very period when this portrait was painted Luther had attacked the Pope for the way he raised money for the new St Peter's. It so happens that it was Raphael himself whom Leo X had put in charge of this building enterprise after Bramante had died in 1514, and thus he had also become an architect, designing churches, villas and palaces and studying the ruins of ancient Rome.

The uniform tone of colour, expressed in various red nuances; the quiet atmosphere, alluding to the power of the Pope and the splendour of his court; and the compositional harmony, make this portrait one of the most admired and significant works of Raphael.

This portrait shows the eminent man of letters and librarian of Pope Leo X, born in Volterra in 1470, with an absorbed expression, in the act of writing. It is assumed that Inghirami worked with Raphael on the program of the Stanza della Segnatura. Inghirami became praefect of Vatican Library under Julius II. The portrait is an exceptional work for its fullness of vision and vibrant colors, without being excessively grandiose or dramatic.

The red of the Cardinal's clothing dominates both. Inghirami's crossed eyes, a physical defect which the artist does not leave out, acquire a discreet tone which almost dissolves in the inspired pose of the figure. Without idealizing, but also without falling into unpleasant naturalism, Raphael maintains a harmonic equilibrium between realism and dignified celebration, a primary characteristic of portrait painting.

The picture was part of the collection of Cardinal Leopoldo de Medici. It was stolen by the French in 1799 and returned in 1816.

Baldassarre Castiglione was a literary figure active at the court of Urbino in the early years of the 16th century. The portrait may or may not have been in fact painted by Raphael. According to a letter of 1516 from Pietro Bembo to Cardinal Bibbiena, "The Portrait of M. Baldassare Castiglione... [and that of Duke Guidobaldo da Montefeltro would seem to be by the hand of one of Raphael's pupils". But the high quality and masterful combination of pictorial elements which distinguish the painting (note the affection inherent in the intelligent and calm face of Castiglione) lead one to believe that the master participated in some way in its execution. Certainly the shaded tonalities of the clothing and the unusually light background indicate the hand of a skillful and experienced painter. Moreover, the direct glance of the subject establishes an immediate, intimate contact with the observer.

_c1518.jpg)

The Portrait of a Young Woman (also known as La fornarina) is a painting by the Italian High Renaissance master Raphael, made between 1518 and 1520. It is housed in the Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica in Palazzo Barberini, Rome.

The woman is traditionally identified with the fornarina (bakeress) Margherita Luti, the semi-legendary Roman lover of Raphael, though, probably, the true meaning of the picture has still to be cleared up. The woman is pictured with an oriental style hat and bare breasts. She is making the gesture to cover her left breast, or to turn it with her hand, and is illuminated by a strong artificial light coming from the external. Her left arm has a narrow band carrying the signature of the artist, RAPHAEL URBINAS.

_detail1.jpg)

The picture shows a detail from the portrait known as La Fornarina. The painting is signed, in Latin, "Raphael from Urbino". The signature is engraved on the thin ribbon that the girl wears just under her left shoulder.

Described by Vasari, the Fornarina was also painted by Raphael as the famous veiled lady now in the Palazzo Pitti, as well as in numerous Raphael school paintings. The figure of the Fornarina was at the center of the nineteenth century pseudo-historical romantic myth that grew up around the artist's personality and the figure of his muse-lover. Identification, though not a historically provable one, has been made between Raphael's mythical lover and one Margherita Luti: recorded as the daughter of Francesco Senese, she entered the Convent of Santa Apollonia immediately following the painter's death.

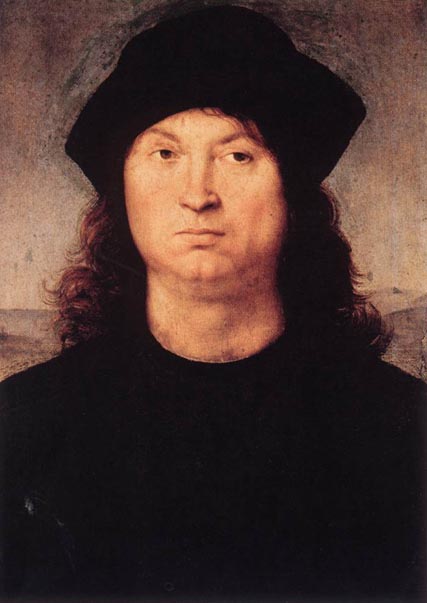

This austere double portrait of great stylistic restraint, set against a green background, in which the two figures, perhaps intentionally conceived by the artist in the manner of Roman busts, seem not to communicate with one another, has never roused a great deal of enthusiasm on the part of critics. In fact, no one has ever seriously studied of this painting and, even though it is now almost universally agreed to be the work of Raphael, the identity of the two figures has remained highly debatable. Some have seen them as Luther and Calvin, or as Bartolo da Sassoferrato and Baldo degli Ubaldi, two fourteenth-century jurists, or as Andrea Doria and Christopher Columbus, an interesting idea, or finally, as Andrea Navagero and Agostino Beaziano, a highly plausible identification that has been accepted by the most recent literature. However a degree of uncertainty must remain and the problem of Raphael's Double Portrait in the Galleria Doria Pamphilj is simply unsolved fact of history.

Tradition identifies the subject with "la Fornarina", the woman whom the painter loved in his last years and whose face reappeared in both his paintings (e.g. in the Sistine Madonna) and those of his followers. However, the woman, has never been decisively identified. She seems to represent Raphael's ideal of beauty at this time.

The painting shows greater attention to colour and to the rendering of skin and clothes in respect to previous female portraits. The regular oval of the young woman's face stands out against the dark background and her eyes hold an intense and penetrating look. The silk of her sleeves contrasts with her ivory-like skin, and is closely associated with the thin pleating of the dress, held up by a corset with golden embroidery.

The merchant Agnolo Doni married Maddalena Strozzi in 1503, but Raphael's portraits were probably executed in 1506, the period in which the painter studied the art of Leonardo most closely. The composition of the portraits resembles that of the Mona Lisa: the figures are presented in the same way in respect to the picture plane, and their hands, like those of the Mona Lisa, are placed on top of one another. But the low horizon of the landscape background permits a careful assessment of the human figure by providing a uniform light which defines surfaces and volumes. This relationship between landscape and figure presents a clear contrast to the striking settings of Leonardo, which communicate the threatening presence of nature.

But the most notable characteristic that distinguishes these portraits from those of Leonardo is the overall sense of serenity which even the close attention to the materials of clothes and jewels (which draw one's attention to the couple's wealth) is unable to attenuate. Every element - even those of secondary importance - works together to create a precise balance.

This portrait is more noticeably covered with a marked craquelure than its counterpart. These hairline cracks in the paint, which appear as the paint ages, particularly affect Maddalena's even features and full decollete.

.jpg)

An example of his ability to resolve natural elements in a synthetic vision which transcends particular situations is the portrait of a woman called La Donna Gravida in the Pitti Gallery, Florence. The subject is a pregnant woman, conscious of her approaching motherhood, who looks intensely toward the spectator, with her hand on her abdomen. The portrait is finely balanced. Solid forms are reduced to pure spherical volumes, overlaid with carefully chosen colours. The sense of colour which this painting shows will be used again by Raphael in his portrait of Cardinal Fedra Inghirami.

There are very few examples of portraits of a pregnant woman in Renaissance painting. Raphael shows great sensitivity for the special situation of the mother-to-be by showing both her fragility and her calm pride. Her left hand, resting protectively, gently emphasizes the swell of her stomach, while her gaze rests directly on the onlooker.

The subject has been associated with Francesco Maria Della Rovere, and possibly correctly: the portrait reached Florence with the Della Rovere patrimony in 1631 on the marriage of Vittoria Della Rovere to the future Grand Duke Ferdinand II.

In St Paul Preaching in Athens, the viewers become the listeners, joining the circle of those people the Apostle is addressing. In this scene Raphael succeeded in creating a classical mood by integrating into the composition motifs from Roman reliefs and classical figures, buildings, and statues.

The Transfiguration is the last bequest of an artist whose brief life was rich in inspiration, where doubt or tension had no place. Raphael's life was spent in thoughts of great harmony and balance. This is one of the reasons why Raphael appears as the best interpreter of the art of his time and has been admired and studied in every century.

On 6 April 1520, precisely 37 years after he was born, Raphael died in Rome, the city that he had helped make the most important centre of art and culture that had ever existed.

The balance of this composition impressed Vasari. Ezekiel is so small he can scarcely be recognized in the bottom left of the background, the scenes being completely dominated by his vision.

As subject Raphael chose a verse from a poem by the Florentine Angelo Poliziano which had also helped to inspire Botticelli's 'Birth of Venus'. These lines describe how the clumsy giant Polyphemus sings a love song to the fair sea-nymph Galatea and how she rides across the waves in a chariot drawn by two dolphins, laughing at his uncouth song, while the gay company of other sea-gods and nymphs is milling round her.

Raphael's fresco shows Galatea with her gay companions; the giant is depicted in a fresco by Sebastiano del Piombo which stands to the left of Raphael's Galatea. However long one looks at this lovely and cheerful picture, one will always discover new beauties in its rich and intricate composition. Every figure seems to correspond to some other figure, every movement to answer a counter-movement.

To start with the small boys with Cupid's bows and arrows who aim at the heart of the nymph: not only do those to right and left echo each other's movements, but the boy swimming beside the chariot corresponds to the one flying at the top of the picture. It is the same with the group of sea-gods which seems to be 'wheeling' round the nymph. There are two on the margins, who blow on their sea-shells, and two pairs in front and behind, who are making love to each other. But what is more admirable is that all these diverse movements are somehow reflected and taken up in the figure of Galatea herself. Her chariot had been driving from left to right with her veil blowing backwards, but, hearing the strange love song, she turns round and smiles, and all the lines in the picture, from the love-gods' arrows to the reins she holds, converge on her beautiful face in the very centre of the picture.

By these artistic means Raphael has achieved constant movement throughout the picture, without letting it become restless or unbalanced. It is for this supreme mastery of arranging his figures, this consummate skill in composition, that artists have admired Raphael ever since. Just as Michelangelo was found to have reached the highest peak in the mastery of the human body, Raphael was seen to have accomplished what the older generation had striven so hard to achieve: the perfect and harmonious composition of freely moving figures.

There was another quality in Raphael's work that was admired by his contemporaries and by subsequent generations - the sheer beauty of his figures. When he had finished the 'Galatea', Raphael was asked by a courtier where in all the world he had found a model of such beauty. He replied that he did not copy any specific model but rather followed "a certain idea" he had formed in his mind. To some extent, then, Raphael, like his teacher Perugino, had abandoned the faithful portrayal of nature which had been the ambition of so many Quattrocento artists. He deliberately used an imagined type of regular beauty. If we look back to the time of Praxiteles, we remember how what we call an "ideal" beauty grew out of a slow approximation of schematic forms to nature. Now the process was reversed. Artists tried to modify nature according to the idea of beauty they had formed when looking at classical statues - they "idealized" the model. It was a tendency not without its dangers, for, if the artist deliberately "improves on" nature, his work may easily look mannered or insipid. But if we look once more at Raphael's work, we see that he, at any rate, could idealize without any loss of vitality and sincerity in the result. There is nothing schematic or calculated in Galatea's loveliness. She is an inmate of a brighter world of love and beauty - the world of the classics as it appeared to its admirers in sixteenth-century Italy.

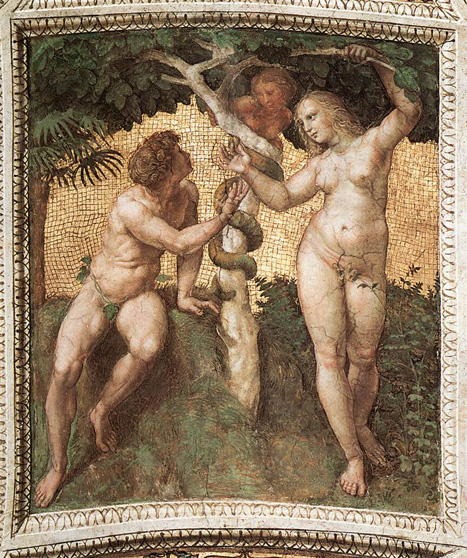

Three Graces are the personification of grace and beauty and the attendants of several goddesses. In art they are often the handmaidens of Venus, sharing several of her attributes such as the rose, myrtle, apple and dice. Their names according to Hesoid (Theogony 905) were Aglaia, Euphrosyne and Thalia. They are typically grouped so that the two outer figures face the spectator, the one in the middle facing away. This was their antique form, known and copied by the Renaissance.

The group has been the subject of much allegorising in different ages. Seneca (c. 4 B.C.-A.D. 65) (De Beneficiis l.3:2) described them as smiling maidens, nude or transparently clothed, who stood for the threefold aspect of generosity, the giving, receiving and returning of gifts, or benefits: "ut una sit quae det beneficium, altera quae accipiat, tertia quae reddat." The Florentine humanist philosophers of the 15th century saw them as three phases of love: beauty, arousing desire, leading to fulfillment; alternatively as the personification of Chastity, Beauty and Love, perhaps with the inscription "Castitas, Pulchritudo, Amor."

The Three Graces is Raphael's first study of the female nude in both front and back views. It was probably not based on living models, however, but on the classical sculpture group of the Three Graces in Siena.

The figures occupy a trabeated loggia, on two levels. The structure of the loggia reflects the architecture of the chapel: its arches coincide with those of the window and entrance. The Prophets (Habakkuk, Jonah, David and Daniel, according to the most widely accepted interpretation) are generally attributed to a collaborator (perhaps Timoteo Viti) who must have based them on an original drawing by Raphael, for they are highly coherent. The Sibyls (Cumaean, Persian, Phrygian and Tiburtine) are attributed to Raphael. Like the Virtues in the Stanza della Segnatura, each of the figures is accompanied by an angel who indicates the divine spirit present in their prophecies. Between the Sibyls at the top of the arch is a small angel holding a lighted torch, the symbol of prophecy, which enlightens the darkness of the future.

A scientific examination using infra-red light has proved this cartoon to be by Raphael himself. Detailed underdrawings were found beneath the layer of paint, which are recognizably by Raphael's sure hand. The drop of paint running vertically down the cartoon shows that it was hung up for painting.

The scene The Miraculous Draught of Fishes is unique not merely for changing the iconography of tapestry weaving. Dawn is breaking over the lake, birds fly out from the depths of the picture and pass over the fishermen. These are powerfully built men dressed in simple shirts or tunics, and we can see their reflections in the water. An atmospheric light fills the whole composition. The arm of one of the fisherman extends into the depths of the picture and is shown 'contre jour', one side catching the red glow of the dawn. Glowing highlights accentuate the garments and model the muscular bodies. These painterly effects presented a great challenge to the tapestry weavers. In particular, the shirt of the Disciple who is so amazed by the miracle that he has jumped up in the boat in utter bewilderment tested the skills and resources of the Brussels weavers to their limits. Here, Raphael painted highlights shading into yellow together with bluish-gray shadows on a green half tint shot through with orange.

The composition of this fresco clearly reflects the order and unity of the Mass of Bolsena. But the story is broken down into three distinct episodes, taken from the Acts of the Apostles. The first shows the dismay of the guards; the second the appearance of the Angel of Freedom in the saint's cell; the third, the bewildered Peter led by the hand of the divine messenger. The barred cell is on an upper level (like the altar in the Mass) and is reached by steps to the left and right. A group of agitated figures occupies the stairway at the left. Here, a soldier - whose armor reflects the light of the moon asks his sleepy and bewildered comrades what is going on. At right, the angel leads the stunned and still-sleepy St Peter past another sleeping guard. Here, for the first time, Raphael attempts a "night effect", using both the natural light of the moon and the autonomous light of the angel.

Raphael's assistants played a greater role in painting the Eliodoro cycle than in the Stanza della Segnatura. This is clearly a consequence of the growing number of commissions which the Romans granted to Raphael. The hand of Giulio Romano, one of his most faithful pupils, is visible in the episode showing the Liberation of St Peter.

This painting is the last fresco that can be attributed to Raphael with any certainty. The large cycles which follow (except for the Sibyls of Santa Maria della Pace) were entrusted mainly to assistants.

The Madonna dell'Impannata in the Pitti Gallery in Florence was also painted with the help of assistants. According to some critics, the assistants executed the entire painting. But others see the master's hand at least in the major figures (some say in the Christ Child, some in St Elizabeth, some in both figures). The composition is innovative in respect to the usual iconography of the holy family. It shows St Catherine, St Elizabeth, Christ, the Virgin and St John gathered together in a group. A large tent is visible in the background and a window covered by linen (the impannata, or cloth covering of a window, which gives the painting its name) can be seen at the extreme right. Like many other works by Raphael, this painting was carried off by the French in 1799 and was not returned until after the Congress of Vienna, in 1815.

A letter which Raphael sent to the painter, Francesco Francia, provides proof of this journey. According to a legend, Francesco Francia died after seeing the St Cecilia which Raphael painted for the Church of San Giovanni in Monte in Bologna. The story is almost credible, for the Bolognese artistic environment still revolved around the style of Perugino. The painting was commissioned by Elena Duglioli dall'Olio of Bologna. She was famous for having visions and ecstatic fits in which music played a great part, which is probably why she asked for a picture of St Cecilia, the patron saint of music. Raphael decided on a painting in the style of a Sacra Conversazione, with St Cecilia in the centre surrounded by saints. The altarpiece, which is now in the Museum of Bologna, was placed in San Giovanni in Monte in 1515. It was painted some time before, however.

The glorification of purity is the central idea behind this painting. This is expressed by the figures seen on both sides of the principal figure: St John the Evangelist is the patron saint of the church, and St Paul symbolizes innocence, while St Augustine and St Mary Magdalene stand for purity regained through atonement after sinful aberration. The four saints who surround the protagonist form a niche which is strengthened by the poses and gestures of the figures (the glances of the Evangelist and St Augustine cross, St Paul's is lowered and the Magdalene turns hers toward the spectator). Only St Cecilia raises her face toward the sky, where a chorus of angels appears through a hole in the clouds. The monumentality of the figures, typical of Raphael's activity during this period, dominates the other figurative elements.

In the legend of St Cecilia, too, the painter emphasizes her desire to preserve her purity. As they were escorting Cecilia to the house of her betrothed, to the accompaniment of musical instruments, in her heart she called out only to God, beseeching Him to preserve the chastity of her heart and her body.

So runs the fifth-century legend, and accordingly in this picture Cecilia does not hear the profane music, her eyes raised toward the heavens connects her directly with the choir of angels. This much is in complete agreement with the story of the Roman martyr.

In 1263 a Bohemian priest, troubled by doubts about the doctrine of transubstantiation (the belief that the body and blood of Christ are present in the Eucharist), started out on a pilgrimage to Rome. On his way he celebrated mass at Bolsena, and during the consecration the Eucharist began, miraculously, to bleed. Each time he wiped the blood away with a cloth a cross of blood would reappear on the Host, a miracle that swept away the priest's doubts. The cloth became a venerated relic and was later kept at Orvieto Cathedral which was rebuilt (in its present form) to honour the occasion.

Raphael represents the priest, the protagonist of the event, close to the centre of the composition. As he raises the Host, two devotees lean over the semicircular screen which forms the background of the scene. This is a further attempt by Raphael to represent figures in a more dynamic way. Some critics believe he was inspired by Lorenzo Lotto, who was among the artists who had begun to paint the Stanza della Segnatura before his intervention. Pope Julius appears at the right of the scene, a symbol of ecclesiastical authority's presence during, and approval of, the miracle. The Pope's attendants stand one step below and behind him.

The asymmetry of the composition regards time as well as space: the excitement of the figures at the left represents a reaction to the supernatural event, which they witness; the stillness of the Pope and his attendants indicates their spiritual presence, achieved through a meditative evocation of the event.

So-called after the Spanish ducal family of Alba, who owned it for over a century, this painting was later purchased for the Hermitage in St. Petersburg, from which it was acquired for the Mellon Collection. The painting is a perfect expression of the Renaissance art theory. Harmony and balance of design are found in Raphael's ability to stabilize the circular form of the painting with a triangular arrangement of the figures and the strong horizontal line behind them, composed of the river and trees.

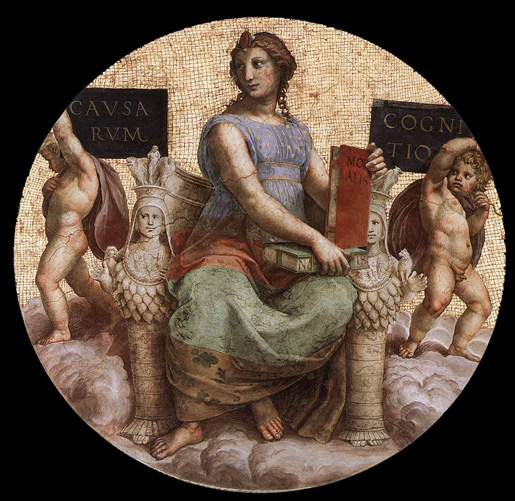

The allegory was intended to include the figure of Justice as well. But Justice, being considered superior to the other virtues from a hierarchical point of view, is represented separately in one of the medallions of the vault. Three winged genii symbolize the theological virtues (Charity, gathering the fruits of the oak; Hope, in the centre with a flaming torch; and Faith, at the extreme right, pointing toward the sky). Two additional putti complete the composition, giving the whole scene a free and graceful movement.

The focal point of the scene is no longer at the centre. Rather, it is shifted to the right. Here Heliodorus and his followers, profaning the Temple of Jerusalem, are driven out by an armed rider and by two running figures. In the depiction of the rider and the two hovering youths, Raphael follows the text from Maccabees in the Apocrypha exactly. The horse owes a debt to Leonardo's design for the Battle of Anghiari in the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence.

In the centre, the expanse of the wide nave, illuminated by the reflections of light in the vault, is a more effective space-determining motif than the large patches of blue sky which appeared through the coffered ceiling in the School of Athens.

At the extreme left, Pope Julius II dominates the bystanders, and he reappears in subsequent scenes as well.

Raphael's new compositional formula, so unexpected after the extremely controlled compositions of the Stanza della Segnatura, is visible in all its dynamic evidence from this fresco onward.

Raphael's pictorial research had been enriched by his solutions regarding the use of light in the Expulsion of Heliodorus and the Liberation of St Peter. These pictorial devices reappear in the Madonna of Foligno, now in the Vatican Museum. The Madonna and Child, borne by a cloud of angels and framed by an orange disk, dominate the group of saints below them, among whom is the donor. This group includes - from left to right - St John the Baptist, St Francis, Sigismondo de' Conti and St Jerome. A small angel at the centre of the composition holds a 'small plaque which was originally intended to carry the dedicatory inscription.

The painting was commissioned to commemorate a miracle in which the donor's house in Foligno was struck by lightning or - according to another version - was struck by a projectile during the siege of Foligno, although it was not damaged. The stormy atmosphere of the landscape background and the flash of lightning (or explosion) which strikes the Chigi Palace (visible at left) illustrate the legend. The strong characterization of the figures, the volumetric fullness of the putti and the refined chiaroscuro distinguish the panel (which was taken as loot by Napoleon's army in 1799 and returned in 1815) as a work of the mature artist.

.jpg)

.jpg)

The Small Cowper Madonna is a more analytical variant of the homogeneous and resolute group of the Madonna del Granduca. Here the painter expresses the influence of Leonardo in a broad, soft landscape. This landscape contains a small church with a cylindrical dome, which may be an allusion to Bramante's architecture; it could be the Franciscan convent of San Bernardino near Raphael's native city of Urbino.

.jpg)

The painting is built around the monstrance containing the consecrated Host, located on the altar. Figures representing the Triumphant Church and the Militant Church are arranged in two semicircles, one above the other, and venerate the Host. God the Father, bathed in celestial glory, blesses the crowd of biblical and ecclesiastical figures from the top of the composition. Immediately below, the resurrected Christ sits on a throne of clouds between the Virgin (bowed in adoration) and St John the Baptist (who, according to iconographic tradition, points to Christ). Prophets and saints of the Old and New Testament are seated around this central group on a semicircular bank of clouds similar to that which constitutes the throne of Christ. They form a composed and silent crowd and, although they are painted with large fields of colour, the figures are highly individuated.

At the bottom of the picture space, inserted in a vast landscape dominated by the altar and the eucharistic sacrifice, are saints, popes, bishops, priests and the mass of the faithful. They represent the Church which has acted, and which continues to act, in the world, and which contemplates the glory of the Trinity with the eyes of the mind. Following a fifteenth century tradition, Raphael has placed portraits of famous personalities, both living and dead, among the people in the crowd. Bramante leans on the balustrade at left; the young man standing near him has been identified as Francesco Maria Della Rovere; Pope Julius II, who personifies Gregory the Great, is seated near the altar Dante is visible on the right, distinguished by a crown of laurel. The presence of Savonarola seems strange, but may be explained by the fact that Julius II revoked Pope Alexander VI's condemnation of Savonarola (Julius was an adversary of Alexander, who was a Borgia).

The structure of the composition is characterized by extreme clarity and simplicity, which Raphael achieved through sketches, studies and drawings containing notable differences in pose. References to other artists are visible throughout the composition (the young Francesco Maria Della Rovere, for example, possesses a Leonardo-like physiognomy). But the layout, the gestures and the poses are original products of Raphael's research, which here reaches a degree of admirable balance and high expressive dignity.

The background of the painting probably shows a landscape near to Rome.

.jpg)

Michelangelo's influence on Raphael is evident in this composition. The pyramidal structure of the figure group recalls Leonardo (whose cartoon for the St Anne was shown in 1506 in the Church of Santissima Annunziata). But Raphael exerts his own balancing capacity on the Leonardesque volumetric conception, infusing it with the idyllic serenity which characterizes his paintings from this period. The work as a whole is structurally harmonic, from the figure group (dominated by the affectionate figure of the Virgin Mary who supports the Child and glances tenderly at the young St John) to the sweeping landscape (made luminous by the mirror-like lake which stretches from one side of the panel to the other). The twisting figures of the two children clearly reflect Michelangelo's figurative research.

.jpg)

The Ansidei altarpiece, of a type known as sacra conversazione (Italian for `holy conversation'), in which the enthroned Virgin and Child and their attendant saints seem to commune together, was commissioned by Bernardino Ansidei for his family chapel in a Perugian church. The chapel was dedicated to Saint Nicholas of Bari, and the bishop saint is shown with his attribute of three golden balls (the origin of pawnbrokers' signs) representing the bags of gold he donated as dowries to three poor girls. John the Baptist, who foretold the coming of Christ and baptised him, wears the camel tunic of his desert sojourn and a crimson prophet's cloak. Instead of his usual reed cross, he holds a wonderfully transparent cross of crystal. Pointing to the Child on the Virgin's lap, he looks up gravely to the Latin inscription above her, `Hail, Mother of Christ'. Beads of scarlet coral, a common charm against evil, the colour of Christ's blood, hang from the canopy. The vaulted niche open onto the luminous Umbrian countryside was designed to seem continuous with the actual architecture of the chapel.

The luminous landscape background and the high baldachin remotely recall the art of Piero della Francesca, but the figure types, still vaguely Peruginesque in their contours, are psychologically more complex and structurally more volumetric. The compositional scheme is reduced to a large arch whose central axis is represented by the baldachin. The result is a sense of monumentality and harmonic proportion which were to become constant in Raphael's art.

One of the three predella panels for this altarpiece survives and is also in the National Gallery, Saint John the Baptist Preaching, which must have been placed to the left, beneath the figure of the saint. Below the Virgin and Child there was once a scene of the Marriage of the Virgin, and Saint Nicholas saving the Lives of Seafarers originally supported Nicholas's image on the right.

In spite of the fact that this painting is in part changed by the drastic nineteenth century restoration which included the repainting of the background and of the dress, it has still remained one of the finest creations of Raphael in his early period, at the time, when having come to Florence after his first formation under Perugino, he became acquainted with Florentine art at the beginning of the Cinquecento; and as is clearly seen in this work, was especially impressed by the painting of Leonardo. In the Madonna del Granduca both the Peruginesque and the Leonardesque influences are fused and assimilated by the young artist into a marvellous harmony which extends to the whole composition, from the spacing of the two figures in the space with that sense of flowing rhythm to the magic of the colour which softly dissolves into delicate shadow.

Raphael's greatest paintings seem so effortless that one does not usually connect them with the idea of hard and relentless work. To many he is simply the painter of sweet Madonnas which have become so well known as hardly to be appreciated as paintings any more. For Raphael's vision of the Holy Virgin has been adopted by subsequent generations in the same way as Michelangelo's conception of God the Father We see cheap reproductions of these works in humble dwellings, and we are apt to conclude that paintings with such a general appeal must surely be a little 'obvious'. In fact, their apparent simplicity is the fruit of deep thought, careful planning and immense artistic wisdom. A painting like Raphael's 'Madonna dell Granduca', is truly 'classical' in the sense that it has served countless generations as a standard of perfection in the same way as the works of Pheidias and Praxiteles. It needs no explanation. In this respect it is indeed 'obvious'. But, if we compare it with the countless representations of the same theme which preceded it, we feel that they have all been groping for the very simplicity that Raphael has attained. We can see what Raphael did owe to the calm beauty of Perugino's types, but what a difference there is between the rather empty regularity of the master and the fullness of life in the pupil! The way the Virgin's face is modeled and recedes into the shade, the way Raphael makes us feel the volume of the body wrapped in the freely flowing mantle, the firm and tender way in which she holds and supports the Christ Child - all this contributes to the effect of perfect poise. We feel that to change the group ever so slightly would upset the whole harmony. Yet there is nothing strained or sophisticated in the composition. It looks as if it could not be otherwise, and as if it had so existed from the beginning of time.

.jpg)

Raphael met the challenge of creating a round composition when he painted this delicate Madonna. He provides a stable structure for the round picture by means of the vertical figure of the Madonna and the horizontal lines of the landscape. The Madonna's head is gently inclined and the contour of her left hand flows rhythmically into the outline of the Christ Child's body, thus responding to the circular form.

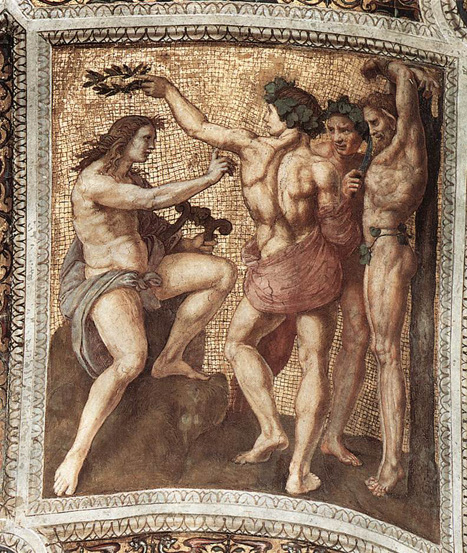

Mount Parnassus, the home of Apollo, is, like the hill of the Vatican, a place where in ancient times there was a shrine to Apollo dedicated to the arts. This has a direct bearing on the picture because through the window on the wall where the fresco is painted there is a view of the Cortile del Belvedere and the hill of the Vatican. There were newly discovered classical sculptures in the Cortile, such as the Ariadne that Raphael used as a model for the muse to the left of Apollo.

Apollo plays a lira da braccio (an anachronism which, according to some, was meant to symbolize the perpetual value of the poetic message). He sits under a laurel grove with the nine Muses (who personify the nine types of art). The most eminent classical and contemporary poets are depicted together in a harmonic ascending and descending movement from left to right. Homer is flanked by Virgil and Dante, Ovid and Horace are next to Sappho, while from the "ranks" of moderns we can identify Petrarch, Boccaccio and Ariosto. Petrarch is recognizable in the group in the left foreground; so is Sappho, who holds a scroll bearing her name; Ennius is seated above them, listening to the song of the blind Homer (who appears as a protagonist, like Apollo), behind him stands Dante, who had also appeared in the Disputa as a theologist, evidently because of the doctrinal content of the Divine Comedy. Some see the portrait of Michelangelo in the bearded figure immediately to the right of the central group, although it is more readily identified with Tebaldeo or Castiglione, for the scene is, after all, a celebration of poetry.

Raphael in several sketches significantly changed some of the details, including the musical instruments used. In the early versions Apollo played on a traditional stylized classical lyre, but this fresco shows him playing a Renaissance lira da braccio with a bow. The bow was unknown in Antiquity, although later they attributed its invention to Sappho. It has nine, instead of seven, strings to match the number of Muses; this, in Raphael's conception, signifies timelessness, just as the fact that the classical and contemporary poets are depicted together.

While working on this fresco, the artist may have become acquainted with that ancient sarcophagus from Asia Minor which is adorned with the relief sculpture of the nine Muses. This was his source for the three additional instruments shown in this fresco: Erato's kithara, to the right of Apollo, the Lydian aulos of Eutherpe, on the other side, and below, the strange, tortoise-shell lyre of Sappho - all of which he rendered striving for archeological accuracy.

In this fresco, music fills the role of moving force behind the Apollonian universe, at the same time being the symbol of poetry.

Compositional harmony and visual counterpoint characterize the fresco: the groups of figures are bound together by continuous lines and the single characters are represented in opposed but corresponding poses. Although the Parnassus lacks the high originality of the School of Athens, it demonstrates Raphael's illustrative ability. It is enriched by classical elements which must have held great appeal for a cultural class excited by the recent archaeological discoveries. Thus we must add Raphael's capacity to interpret contemporary taste to his genuine artistic skills.

This painting is the highpoint of all Raphael's Florentine Madonnas. The bodies occupy the space with great freedom, while the figures interact with deep feeling. The arch formed by the frame completes the composition harmoniously. Raphael put the date of the picture into the hem of the Virgin's mantle, as he often did, but it is not clear if the Roman numerals are meant to be read as 1507 or 1508.

The artist detaches himself both formally and iconographically from traditional representations of the scene. He does not depict the deposition itself, but the carrying of the dead Christ. The protagonists of the scene do not demonstrate their sorrow violently, but are reduced, through the Raphaelesque mode of feeling, to a sort of painful resignation. The vision of space is less geometric than the Florentine vision, and it appears freer and closer to nature. The influence of Michelangelo is strong, however, and can be perceived without doubt in the limp arm of Christ as well as in the female figure at the extreme right. The latter mirrors the figure of the Virgin in the Tondo Doni, which Michelangelo executed between 1504 and 1506. The formal vigour and sense of open space which characterize Michelangelo's painting certainly must have had a profound effect on Raphael.

There are three compositions (Faith, Hope and Charity) of the predella executed in a delicate monochrome (today in the Vatican Museum). Both the main panel and the predella were carried from Perugia to Rome by Pope Paul V. They were replaced by copies in 1608. The painting was subsequently included among the works taken by the French troops and was exhibited in Paris in the Napoleonic Museum from 1797 to 1815 when, following the restitutions ordered by the Congress of Vienna, it was returned to Rome.

The reproduction shows the painting before restoration. In 1982 the German conservator Hubert von Sonnenburg undertook a careful restoration of this picture and removed a distorting blue overpaint, dating from the 18th century, from the sky area which covered the putti on the upper left and right.

The St Michael and St George and the Dragon in the Louvre, and the St George of the National Gallery in Washington are bound together both by their subject - an armed youth fighting a dragon - and by stylistic elements. All three are assigned to the Florentine period and echo those stimuli which Raphael received from the great masters who worked in Florence or whose paintings were visible there. The influence of Leonardo - whose fighting warriors from the Battle of Anghiari (1505) in the Palazzo della Signoria provided an extraordinary example of martial art (the painting deteriorated very rapidly because of shortcomings in Leonardo's experimental technique and so is no longer visible) - predominates in these works. But references to Flemish painting suggest the environment of Urbino, where Northern influences were still quite vivid.

Raphael's imagination which is particularly developed in the details of the St Michael, is more balanced in the figure of the Archangel, the focus of the entire composition. This sense of balance and composure is developed further in the other two panels, where the landscape, still of Umbrian derivation, accentuates the serenity of the figures, notwithstanding the dramatic character of the subject. These small panels are indicative of a moment in which the painter gathers the stylistic fruits of what he has assimilated so far and, at the same time, poses pictorial problems which will be developed in the future.

Saint George is one of the most popular of Christian saints and is the patron saint of England. He was also a favourite subject of Renaissance artists, who depicted him slaying the dragon. According to legend, this monster infested a marsh outside the walls of a city and, with his fiery breath, could poison all who came near. In order to placate the dragon, the city furnished him with a few sheep every day. But when the supply of sheep was exhausted, the sons and daughters of the citizens became the victims. The lot fell one day on the princess, and the King reluctantly sent her forth to the dragon. Saint George happened to be riding by and, seeing the maiden in tears, commended himself to God and transfixed the dragon with his spear.

St George's lance has been broken in the struggle, but the proud knight is about to vanquish the dragon with the sword, and so free the princess, who is fleeing on the right. By the middle of the 16th century this panel formed a pair with Raphael's St. Michael. Even though the latter was painted somewhat earlier, the fact that they are the same size and have a comparable iconography implies that Raphael intended that the saints should belong together.

.jpg)

A young knight is asleep in front of a laurel tree that divides the picture into two equal parts. There is a figure of a beautiful young woman in each half on the left the personification of Virtue is holding a book and a sword above the sleeping figure, while the figure on the right is presenting a flower as a symbol of sensual pleasure. The probable meaning of the allegory is that the young man's task is to bring both sides of life into harmony.

.jpg)

The composition derives from other panels on the same subject painted by Perugino; for example, the imposing Chigi Altarpiece for Sant'Agostino in Siena. But the rigorous correspondences of gesture that distinguish Raphael's figures from the sentimental and obvious poses of the master, clearly set the young pupil apart. The faces are treated with a subtler chiaroscuro and the volumes are, as a result, more slender than those of Perugino. Thus Raphael - even though he is unwilling and, perhaps, unable to break away from Perugino's influence - shows his true temperament in this painting. This temperament includes an extraordinary feeling for proportion and an acute visual sensibility. It is even more evident in the two predella compartments - one in the Cook Collection in Richmond and the other in the Lisbon Gallery - with Stories from the Life of St Jerome.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Sebastian is holding an arrow, the symbol of his martyrdom, his little finger held up elegantly. Wearing a gorgeous red cloak and a gold embroidered shirt, with his hair elegantly arranged, there is nothing about this figure that recalls the torments St Sebastian suffered for his faith. This is a typical early work unanonimously attributed to Raphael and, in its ornamental beauty and elegiac mood, it is very reminiscent of the works of Perugino.

The picture represents slight variations of Perugino's motives. Here, graceful Peruginesque poses and the hazy transparency of colour characteristic of Francesco Francia, are fused together in a way that clearly indicates Raphael's presence. His ability to compose clear and balanced forms becomes typical from this work on, as does the discreet and harmonious distillation of the formal elements of other painters in the clear, serene vision which seems characteristic of his artistic temperament.

.jpg)

According to Raphael's preliminary study (Musee des Beaux-Arts, Lille) the figure stood on the lower left, next to St. Nicholas of Tolentino. The powerful modelling of the angel's head, and the emphatic expression on his face as he gazes upwards, indicate that it is an early work by Raphael.

2.jpg)

Critics believe the painting to be inspired by two compositions by Perugino: the celebrated Christ Delivering the Keys to St Peter from the fresco cycle in the Sistine Chapel and a panel containing the Marriage of the Virgin now in the Museum of Caen.

By painting his name and the date, 1504, in the frieze of the temple in the distance, Raphael abandoned anonymity and confidently announced himself as the creator of the work. The main figures stand in the foreground: Joseph is solemnly placing the ring on the Virgin's finger, and holding the flowering staff, the symbol that he is the chosen one, in his left hand. His wooden staff has blossomed, while those of the other suitors have remained dry. Two of the suitors, disappointed, are breaking their staffs.

The polygonal temple in the style of Bramante establishes and dominates the structure of this composition, determining the arrangement of the foreground group and of the other figures. In keeping with the perspective recession shown in the pavement and in the angles of the portico, the figures diminish proportionately in size. The temple in fact is the centre of a radial system composed of the steps, portico, buttresses and drum, and extended by the pavement. In the doorway looking through the building and the arcade framing the sky on either side, there is the suggestion that the radiating system continues on the other side, away from the spectator.

Caught at the culminating moment of the ceremony, the group attending the wedding also repeats the circular rhythm of the composition. The three principal figures and two members of the party are set in the foreground, while the others are arranged in depth, moving progressively farther away from the central axis. This axis, marked by the ring Joseph is about to put on the Virgin's finger, divides the paved surface and the temple into two symmetrical parts.

A tawny gold tonality prevails in the colour scheme, with passages of pale ivory, yellow, blue-green, dark brown and bright red. The shining forms appear to be immersed in a crystalline atmosphere, whose essence is the light blue sky.

The structure of Raphael's painting, which includes figures in the foreground and a centralized building in the background, can certainly be compared to the two Perugino paintings. But Raphael's painting features a well developed circular composition, while that of Perugino is developed horizontally, in a way still characteristic of the Quattrocento. The structure of the figure group and of the large polygonal building clearly distinguish Raphael's painting from that of his master. The space is more open in Raphael's composition, indicating a command of perspective which is superior to Perugino's.

Source: Art Renewal Center

Source: Web Gallery of Art

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.