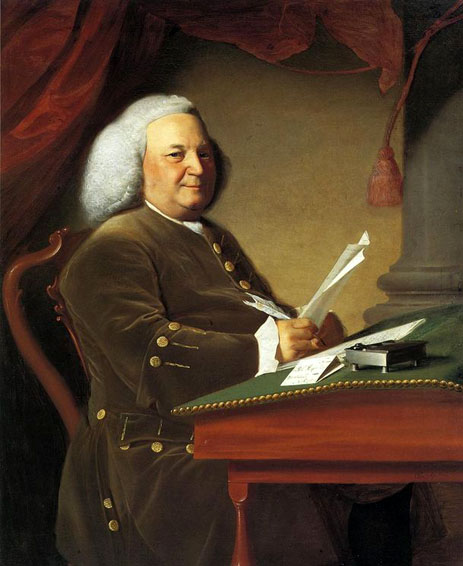

American Painter

1737 - 1815

From: The National Gallery of Art

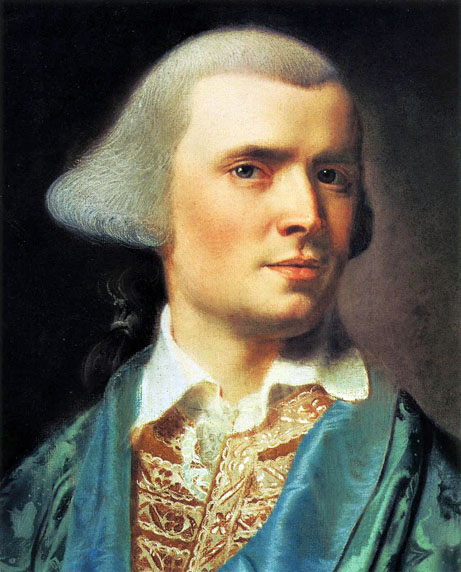

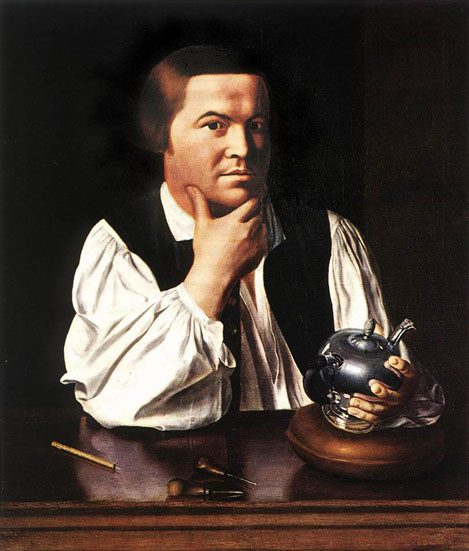

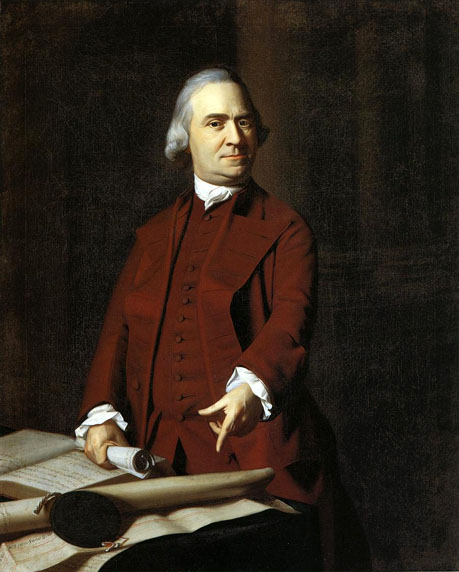

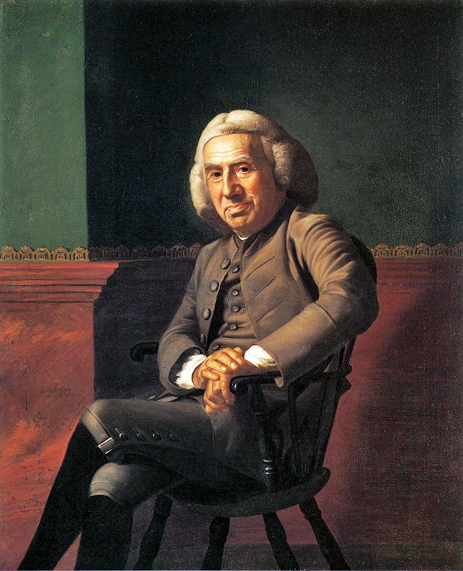

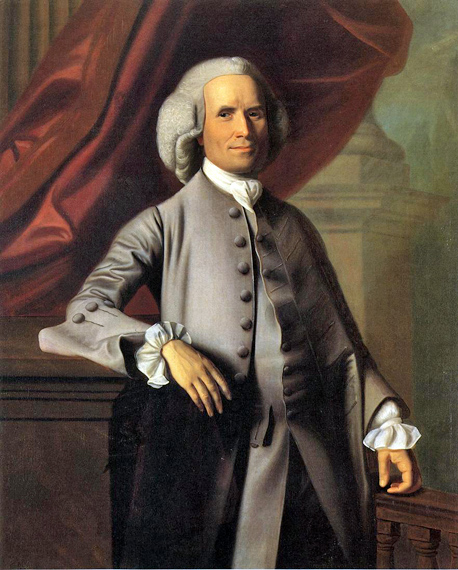

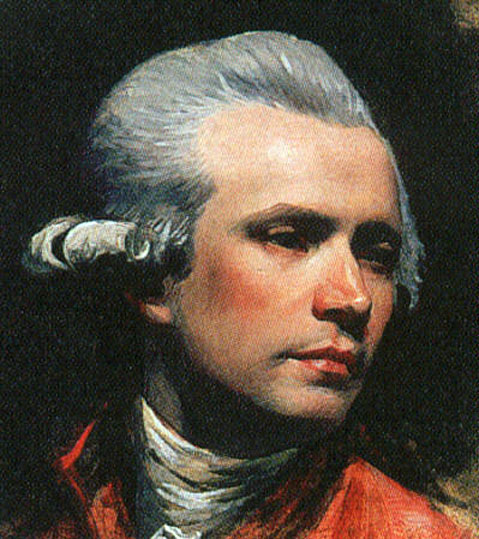

John Singleton Copley was an American painter, born presumably in Boston, Massachusetts and a son of Richard and Mary Singleton Copley, both Irish. He is famous for his portrait paintings of important figures in colonial New England, depicting in particular middle-class subjects. His paintings were innovative in their tendency to depict artifacts relating to these individuals' lives.

Copley's mother owned a tobacco shop on Long Wharf. The parents, who according to the artist's granddaughter, Martha Babcock Amory, came to Boston in 1736, were "engaged in trade, like almost all the inhabitants of the North American colonies at that time". The father was from Limerick; the mother, of the Singletons of County Clare, a family of Lancashire origin. Letters from John Singleton, Mrs. Copley's father, are in the Copley-Pelham collection. Richard Copley, described as a tobacconist, is said by several biographers to have arrived in Boston in ill health and to have gone, about the time of John's birth, to the West Indies, where he died. William H. Whitmore gives his death as of 1748, the year of Mrs. Copley's remarriage. James Bernard Cullen says: "Richard Copley was in poor health on his arrival in America and went to the West Indies to improve his failing strength. He died there in 1737." Neither of the foregoing dates have been confirmed.

Except for a family tradition that speaks of his early talent in drawing, nothing is known of Copley's schooling or of the other activities of his boyhood. His letters, the earliest of which is dated September 30, 1762, reveal a fairly well-educated man. He may have been taught various subjects, it is reasonably conjectured, by his future stepfather, who besides painting portraits and cutting engravings eked out a living in Boston by teaching dancing and, beginning September 12, 1743, by conducting an "Evening Writing and Arithmetic School", duly advertised. It is certain that the widow Copley was married to Peter Pelham on May 22, 1748 and that at about that time she transferred her tobacco business to his house in Lindall Street (a quieter, more respectable part of town), at which the evening school also continued its sessions. In such a household young Copley may have learned to use the paintbrush and the engraver's tools. Whitmore says plausibly: "Copley at the age of fifteen was able to engrave in mezzotint; his stepfather Pelham, with whom he lived three years, was an excellent engraver and skillful also with the brush."

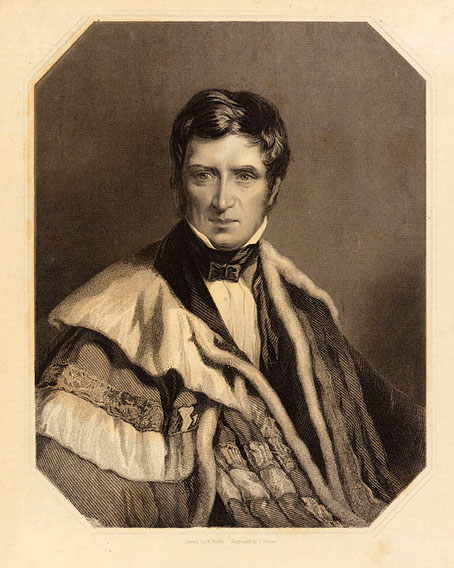

The artistic opportunities of the home and town in which Copley grew to manhood should be emphasized because he himself, as well as some of his biographers taking him too literally have made much of the bleakness of his early surroundings. His son, Lord Lyndhurst, wrote that "he (Copley) was entirely self taught, and never saw a decent picture, with the exception of his own, until he was nearly thirty years of age." Copley himself complained, in a letter to Benjamin West, written November 12, 1766: "In this Country as you rightly observe there is no examples of Art, except what is to be met with in a few prints indifferently executed, from which it is not possible to learn much". Variants of this thesis are found almost everywhere in his earlier letters.

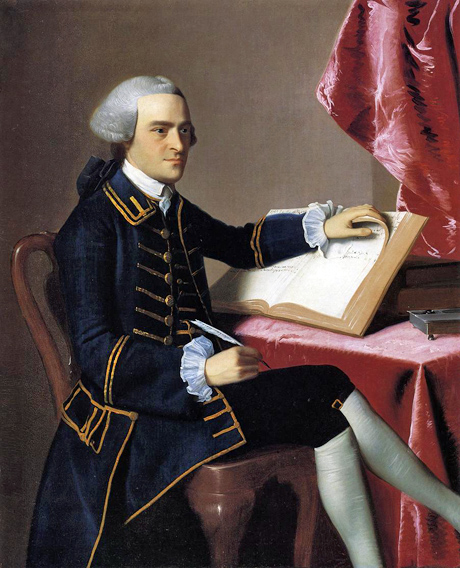

Copley was about fourteen and his stepfather had recently died, when he made the earliest of his portraits now preserved, a likeness of his half-brother Charles Pelham, good in color and characterization though it has in its background accessories which are somewhat out of drawing. It is a remarkable work to have come from so young a hand. The artist was only fifteen when (it is believed) he painted the portrait as well as an engraving of the Rev. William Welsteed, minister of the Brick Church in Long Lane, a work which, following Peter Pelham's practice, Copley personally engraved to get the benefit from the sale of prints. No other engraving has been attributed to Copley. A self-portrait, undated, depicting a boy of about seventeen in broken straw hat, and a painting of Mars, Venus and Vulcan, signed and dated 1754, disclose crudities of execution which do not obscure the decorative intent and documentary value of the works. Such painting would obviously advertise itself anywhere. Without going after business, for his letters do not indicate that he was ever aggressive or pushy, Copley was started as a professional portrait-painter long before he was of age. In October 1757, Capt. Thomas Ainslie, collector of the port of Quebec, acknowledged from Halifax the receipt of his portrait, which "gives me great Satisfaction", and advised the artist to visit Nova Scotia "where there are several people who would be glad to employ You." This request to paint in Canada was later repeated from Quebec, Copley replying: "I should receive a singular pleasure in excepting, if my Business was anyways slack, but it is so far otherwise that I have a large Room full of Pictures unfinished, which would engage me these twelve months if I did not begin any others."

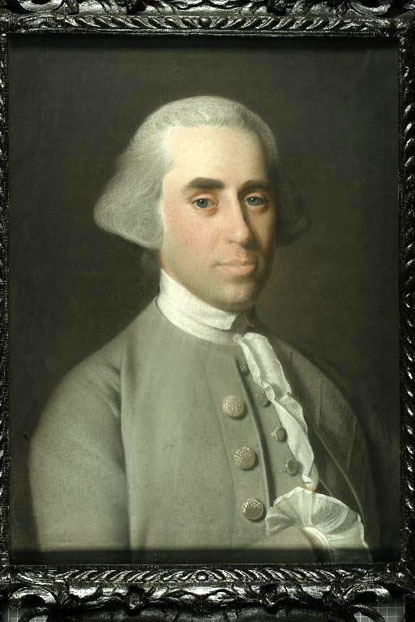

Besides painting portraits in oil, doubtless after a formula learned from Peter Pelham, Copley was a pioneer American pastel painting. He wrote, on September 30, 1762, to the Swiss painter Jean-Etienne Liotard, asking him for "a set of the best Swiss Crayons for drawing of Portraits." The young American anticipated Liotard's surprise "that so remote a corner of the Globe as New England should have any demand for the necessary utensils for practicing the fine Arts" by assuring him that "America which has been the seat of war and desolation, I would feign hope will one Day become the School of fine Arts." The requested pastels were duly received and used by Copley in making many portraits in a medium suited to his talent. By this time he had begun to demonstrate his genius for rendering surface textures and capturing emotional immediacy.

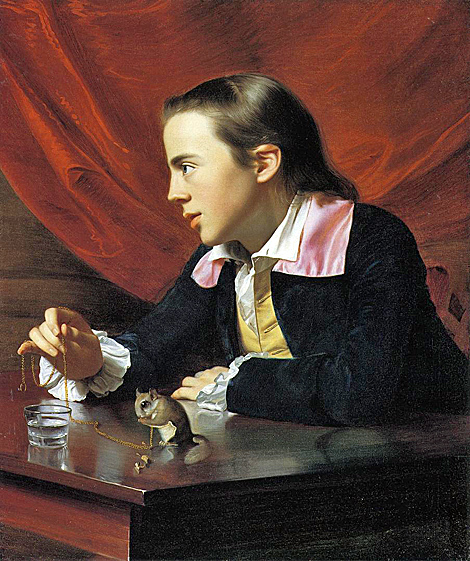

Copley's fame was established in England by the exhibition, in 1766, of 'The Boy with the Squirrel', which depicted his half-brother, Henry Pelham, seated at a table and playing with a pet squirrel. This picture, which made the young Boston painter a Fellow of the Society of Artists of Great Britain, by vote of September 3, 1766, had been painted the preceding year. Copley's letter of September 3, 1765, to Captain R. G. Bruce, of the John and Sukey, reveals that it was taken to England as a personal favor in the luggage of Roger Hale, surveyor of the port of London. An anecdote relates that the painting, unaccompanied by name or letter of instructions, was delivered to Benjamin West (whom Mrs. Amory describes as then "a member of the Royal Academy," though the Academy was not yet in existence). West is said to have "exclaimed with a warmth and enthusiasm of which those who knew him best could scarcely believe him capable, 'What delicious coloring worthy of Titian himself!'" The American squirrel, it is said, disclosed the colonial origin of the picture to the Pennsylvania-born Quaker artist. A letter from Copley was subsequently delivered to him. West got the canvas into the Exhibition of the year and wrote, on August 4, 1766, a letter to Copley in which he referred to Sir Joshua Reynolds's interest in the work and advised the artist to follow his example by making "a visit to Europe for this purpose (of self-improvement) for three or four years."

West's subsequent letters were considerably responsible for making Copley discontented with his situation and prospects in a colonial town. Copley in his letters to West of October 13 and November 12, 1766 gleefully accepted the invitation to send other pictures to the Exhibition and mournfully referred to himself as "peculiarly unlucky in Living in a place into which there has not been one portrait brought that is worthy to be called a Picture within my memory." In a later letter to West, of June 17, 1768, he displayed a cautious person's reasons for not rashly giving up the good living which his art gave him. He wrote: "I should be glad to go to Europe, but cannot think of it without a very good prospect of doing as well there as I can here. You are sensible that 300 Guineas a Year, which is my present income, is a pretty living in America. . . . And whatever my ambition may be to excel in our noble Art, I cannot think of doing it at the expense of not only my own happiness, but that of a tender Mother and a Young Brother whose dependence is entirely upon me". West replied on September 20, 1768, saying that he had talked over Copley's prospects with other artists of London "and find that by their Candid approbation you have nothing to Hazard in Coming to this Place."

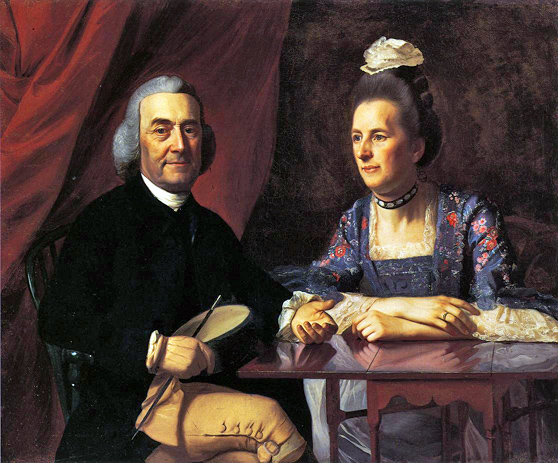

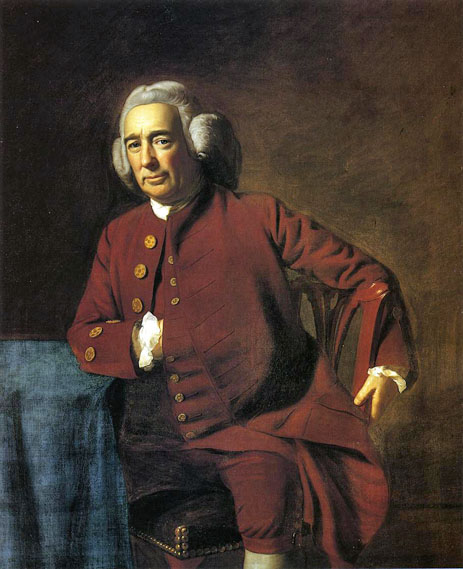

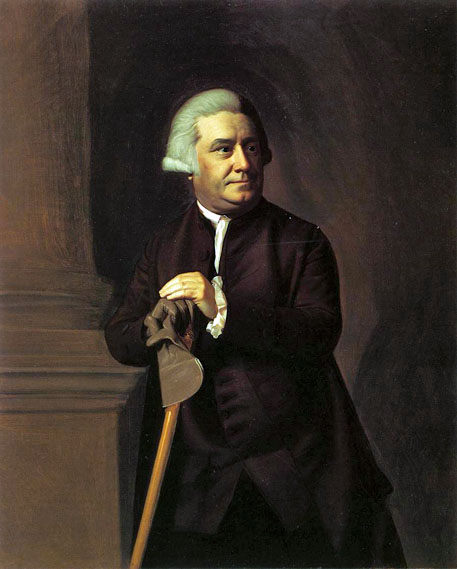

The income which Copley earned by painting in the 1760's was extraordinary for his town and time. It had promoted the son of a needy tobacconist into the local aristocracy. The foremost personages of New England came to his painting-room as sitters. He married, on November 16, 1769, Susanna Farnham Clarke, daughter of Richard and Elizabeth (Winslow) Clarke, the former being the very wealthy agent of the Honorable East India Company in Boston; the latter, a New England woman of Mayflower ancestry. The union was a happy one, and socially notable. Mrs. Copley was a beautiful woman of poise and serenity whose features are familiar through several of her husband's paintings. Copley had already bought land on the west side of Beacon Hill extending down to the Charles River. The newly-married Copley's who would have six children, moved into "a solitary house in Boston, on Beacon Hill, chosen with his keen perception of picturesque beauty". It was on the approximately site of the present Boston Women's City Club. Here were painted the portraits of dignitaries of state and church, graceful women and charming children, in the mode of faithful and painstaking verisimilitude which Copley had made his own. The family's style of living at this period was that of people of wealth. John Trumbull told Dunlap that in 1771, being then a student at Harvard College, he called on Copley, who "was dressed on the occasion in a suit of crimson velvet with gold buttons, and the elegance displayed by Copley in his style of living, added to his high repute as an artist, made a permanent impression on Trumbull in favor of the life of a painter."

In town and church affairs Copley took almost no part. He referred to himself as "desirous of avoiding every imputation of party spirit - Political contests being either pleasing to an artist or advantageous to the Art itself." His name appeared on January 29, 1771, on a petition of freeholders and inhabitants to have the powder house removed from the town whose existence it imperiled. Records of the Church in Brattle Square disclose that in 1772 Copley was asked to submit plans for a rebuilt meeting-house, and that he proposed an ambitious plan and elevation "which was much admired for its Elegance and Grandeur," but which on account of probable expensiveness was not accepted by the society. Copley's sympathy with the politicians who were working toward American independence appears to have been genuine but not so vigorous as to lead him to participate in any of their plans.

It was known to earlier biographers that Copley at one time painted portraits in New York City. The circumstances of this visit, which was supplemented by a few days in Philadelphia, were first disclosed through Professor Guernsey Jones' discovery of many previously unpublished Copley and Pelham documents in the Public Record Office, London. From these letters and papers, published by the Massachusetts Historical Society in 1914, it appears that in 1768 Copley painted in Boston a portrait of Myles Cooper, president of King's College, who then urged his visiting New York. Accepting the invitation later, Copley, between June 1771 and January 1772, painted thirty-seven portraits in New York, setting up his easel "in Broadway, on the west side, in a house which was burned in the great conflagration on the night the British army entered the city as enemies." Copley's letters to Henry Pelham, whom he left in charge of his affairs in Boston, describe minutely the journey across New England, his first impressions of New York, which "has more Grand Buildings than Boston, the streets much cleaner and some much broader," and the successful search for suitable lodgings and a painting-room; thereafter they give detailed accounts of sitters and social happenings. The correspondence also contains Copley's careful instructions to Pelham concerning the features of a new house then being built on his Beacon Hill "farm," giving elevations and specifications of the addition of "piazzas" which the artist saw for the first time in New York. Copley at the time had a lawsuit respecting title to some of his lands. His letters reveal a man who allowed such disputes to worry him considerably.

In September 1771, Mr. and Mrs. Copley visited Philadelphia, where, at the home of Chief Justice William Allen, they "saw a fine Copy of the Titian Venus and Holy Family at whole length as large as life from Correggio". On their return journey they viewed at New Brunswick, New Jersey several pictures attributed to Van Dyck. "The date is 1628 on one of them," wrote Copley; "it is without doubt I think Van Dyck did them before he came to England." Back in New York Copley wrote, on October 17, requesting that a certain black dress of Mrs. Copley's be sent over at once. "As we are much in company," he said, "we think it necessary Sukey (his wife) should have it, as her other Clothes are mostly improper for her to wear". On December 15 Copley informed Pelham that "this Week finishes all my Business, no less than 37 Busts; so the weather permitting by Christmas we hope to be on the road." Thus ended Copley's only American tour away from Boston. Accounts of his having painted in the South are without foundation. Most of the Southern portraits that have been popularly attributed to him were made by Henry Benbridge.

His correspondents in England continued to urge Copley to undertake European studies. He saved an undated and unsigned letter from someone who wrote: "Our people here are enraptured with him; he is compared to Van Dyck, Rueben and all the great painters of Old." His brother-in-law Jonathan Clarke, already in London, advised his "coming this way." West wrote, on January 6, 1773: "My Advice is, Mrs. Copley to remain in Boston till you have made this Tour (to Italy), after which, if you fix your place of residence in London, Mrs. Copley to come over."

Political and economic conditions in Boston were increasingly turbulent. Copley's father-in-law, Mr. Clarke, was the merchant to whom was consigned the tea that provoked the Boston Tea Party. Copley's family connections were all Loyalists. He defended his wife's relatives at a meeting described in his letter of December 1, 1773. He wrote on April 26, 1774, of an unpleasant experience when a mob visited his house demanding the person of Colonel George Watson, a Loyalist mandamus counselor who had gone elsewhere. The patriots having threatened to have his blood if he "entertained any such Villain for the future," Copley exclaimed: "What a spirit! What if Mr. Watson had stayed (as I pressed him to) to spend the night. I must either have given up a friend to the insult of a Mob or had my house pulled down and perhaps my family murdered."

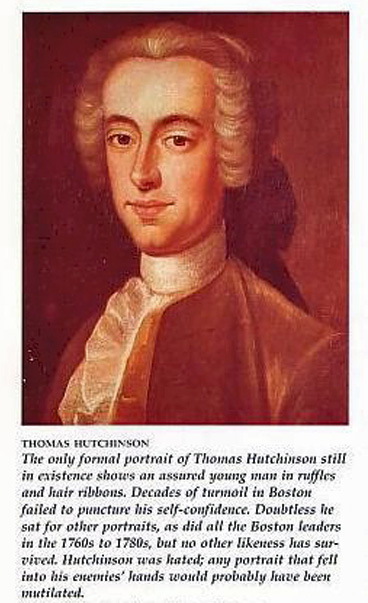

With many letters of introduction, all of which are published in the Copley-Pelham correspondence, Copley sailed from Boston in June 1774, leaving his mother, wife, and children in Henry Pelham's charge. He wrote on July 11 from London "after a most easy and safe passage." An early call was upon West, to "find in him those amiable qualities that make his friendship both desirable as an artist and as a Gentleman." The American was duly introduced to Sir Joshua Reynolds and was taken to "the Royal Academy where the Students had a naked model from which they were drawing." In London Copley took no sitters at this time though urged to do so. Shortly before leaving for Italy he "dined with Governor Hutchinson, and I think there was 12 of us altogether, and all Bostonians, and we had Choice Salt Fish for Dinner."

On September 2, 1774, Copley chronicled his arrival at Paris (the beginning of a nine-month European tour), where he saw and painstakingly described many paintings and sculptures. His journey toward Rome was made in company of an artist named Carter, described as "a captious, cross-grained and self conceited person who kept a regular journal of his tour in which he set down the smallest trifle that could bear a construction unfavorable to the American's character." Carter was undoubtedly an uncongenial companion. Copley, however, may at times have been both depressing and bumptious. He found fault, according to Carter, with the French firewood because it gave out less heat than American wood, and he bragged of the art which America would produce when "they shall have an independent government." Copley's personal appearance was thus described by his uncharitable comrade: "Very thin, a little pock-marked (presumably a souvenir of the Boston smallpox epidemic described by Copley in a letter of January 24, 1764), prominent eyebrows, small eyes, which after fatigue seemed a day's march in his head." Copley afterward wrote of Carter: "He was a sort of snail which crawled over a man in his sleep and left its slime, and no more." Mrs. Amory relates that "both parties were undoubtedly glad to separate on their arrival at their destination." October 8, 1774 found Copley at Genoa, where he wrote to his wife describing, among other things, the cheapness of the silks: "The velvet and satin for which I gave seven guineas would have cost fourteen in London." He reached Rome on October 26. "I am very fortunate," he wrote, "in my time of being here, as I shall see the magnificence of the rejoicing on the election of the Pope; it is also the year of jubilee, or Holy Year."

Copley's plan of study and mode of living at Rome are described in several letters. He found time for excursions. He visited Naples in January 1775, writing to his wife: "The city is very large and delightfully situated but you have no idea of the dirt, . . . and the people are as dirty as the streets,-indeed, they are offensive to such a degree as to make me ill". The excavations at Pompeii greatly interested him and in company with Ralph Izard of South Carolina (whose family portrait he later painted) he extended his journey to Paestum. At Rome early in 1775 he copied Correggio's Saint Jerome on commission from Lord Grosvenor, and other works for Mr. and Mrs. Izard. About May 20 he started on a tour northward through Florence, Parma, Mantua, Venice, Trieste, Stuttgart, Mainz, Cologne, and the Low Countries. From Parma he wrote to Henry Pelham urging that the whole family leave America at once since, "if the Frost should be severe and the Harbor frozen, the Town of Boston will be exposed to an attack; and if it should be taken all that have remained in the town will be considered as enemies to the Country and ill treated or exposed to great distress." This anxiety was groundless, for Mrs. Copley and the children had already sailed on May 27, 1775 from Marblehead in a ship crowded with refugees. She arrived in London some weeks before Copley returned from the Continent, making her home with her brother-in-law, Henry Bromfield. Her father, Richard Clarke, and her brothers came soon after. Copley happily rejoined his family and set up his easel, at first in Leicester Fields and later at 25 George St., Hanover Square, in a house built by a wealthy Italian and admirably adapted to an artist's requirements. Here Mr. and Mrs. Copley and their son Lord Lyndhurst lived and died.

Seated opposite each other are a polished porphyry table, Mr. and Mrs. Izard are surrounded by opulent furnishings and classical references that connote their wealth, discriminating taste, and cultural sophistication. The high-style table and elaborately carved chairs are Roman in design, while the column and plinth behind Ralph Izard are faced with "verde antiqua," a rare green marble from Thessaly. The distant view includes the Coliseum, symbol of ancient Rome and the most important monument for early American travelers to Italy. Ralph Izard holds a drawing of the sculptural group located directly behind them. The inclusion of this sculpture, often identified as "Orestes and Electra," and the fifth century B.C. Greek vase at the upper left, are important reminders of the Izards' interest in art and antiquities. The antique objects also communicate themes of erotic and fraternal love, a reference by Copley to the Izards' love for each other. The Izards never took possession of their portrait, having left Rome late in 1775 to return to London, and moved to Paris during the Revolutionary War. Copley completed the painting, which he then took to London; it may have been the picture exhibited at the Royal Academy, London in 1776, titled "A Conversation."

This text has been adapted from E. Jones in T. Stebbins, et al., "The Lure of Italy:

American Artists and the Italian Experience, 1760-1914," exhibition catalogue, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1992.

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Edward Ingersoll Brown Fund, 1903

As an English painter Copley began in 1775 a career promising at the outset and destined from personal and political causes to end in gloom and adversity. His technique was so well established, his habits of industry so well confirmed, and the reputation that had preceded him from America was so extraordinary, that he could hardly fail to make a place for himself among British artists. He himself, however, "often said, after his arrival in England, that he could not surpass some of his early works". The deterioration of his talent was gradual, however, so some of the "English Copley's" are superb paintings.

Following a fashion set by West and others, Copley began to paint historical pieces as well as portraits. His first foray into this genre was 'A Youth Rescued from a Shark', its subject based on an incident related to the artist by Brook Watson, who had been attacked by a shark while swimming in Havana Harbor as a 14-year-old boy. It is likely that Watson, who went on to a successful career despite the attack and the loss of his leg below the knee, commissioned the painting as a lesson for other unfortunates, including orphans like himself, in the fact that even the severest adversity can be overcome. Engravings from this work achieved an enduring popularity.

Brook Watson bequeathed the painting to a London orphanage, where it conveyed the reassuring moral that anyone can succeed through "activity and exertion" as stated by the biographical plaque on the original frame. In spite of being orphaned himself and also disabled, Watson had earned ennoblement as a baronet.

The depiction of a noteworthy event in an ordinary person's life was an American innovation. European painters normally restricted such harrowing scenes to saints' martyrdoms. This unusual canvas caused a sensation that assured Copley's international reputation after its exhibition at the Royal Academy in 1778. A full-scale replica that the artist painted for himself is in Boston's Museum of Fine Arts.

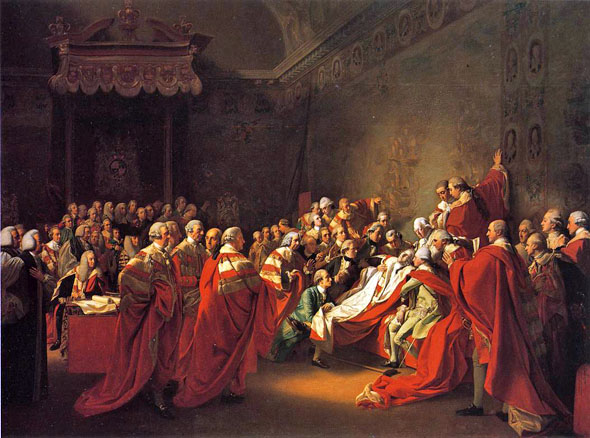

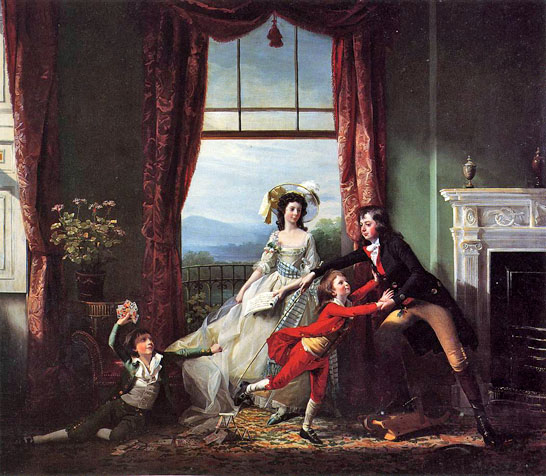

For a place over the fireplace of the George Street dining room was painted the great family picture now at Boston, which, when first publicly shown by Lord Lyndhurst at the Manchester exhibition, 1862, was "pronounced by competent critics to be equal to any, in the same style, by Van Dyck". But the artist's fame as a historical painter was made by 'The Death of Lord Chatham'. The painting, however, brought him denunciation from Sir William Chambers, president of the Royal Academy, who objected to its being exhibited privately in advance of the Academy's exhibition. In an open letter Chambers accused Copley of purveying his picture like a "raree-show" and of aiming for "either the sale of prints or the raffle of the picture." To this censure, obviously unfair to one newly-arrived in London and uninformed as to the professional ethics of exhibiting, Copley one morning wrote a caustic reply, and in the evening wisely threw it into the fire. Engravings from the Chatham picture later sold well in England and America.

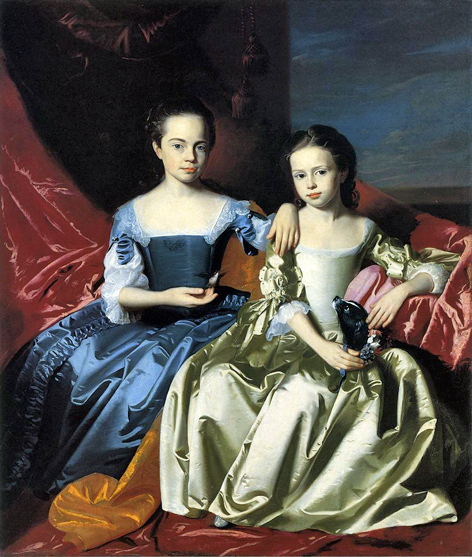

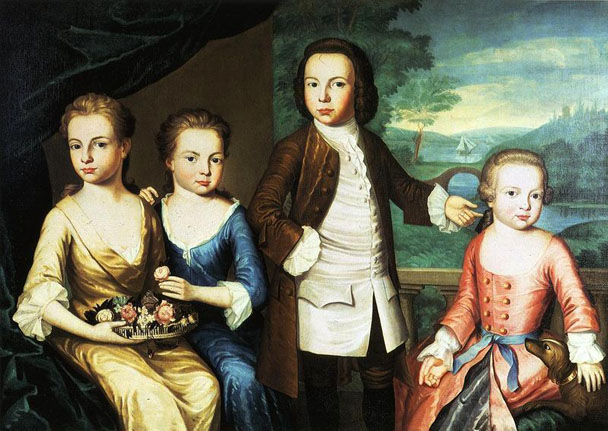

The imaginary setting acts as a dual allegory of the Copleys' civilized sophistication, represented by the elegant furnishings, and their natural simplicity, recalled by the Arcadian landscape. Exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1777, the ambitious picture demonstrated Copley's recent studies on the Continent, where he had learned to integrate a large number of figures into a coherent design. For example, he placed the babies high up on a sofa and in a lap so that their tiny heads would be on a level with their standing siblings.

In proper academic procedure, Copley first used browns and grays to work out the overall distribution of the scene before considering the color scheme and details. Sunshine pours in from a roundel window over the throne canopy, spotlighting the stricken Pitt. The pencil lines drawn over this study create a proportional grid called "squaring" that enabled the artist to transfer and enlarge the design. In 1781, after two years' work, Copley installed his ten-foot-wide picture in a pavilion and charged admission to his popular one-work show. How Copley had persuaded fifty-five noblemen to sit for their portraits became the talk of British society.

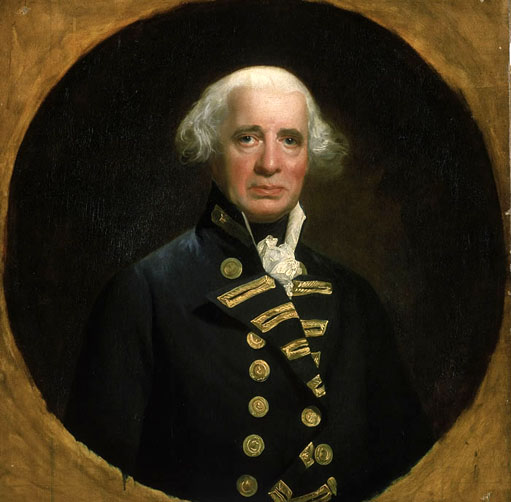

Copley's adventures in historical painting were the more successful because of his painstaking efforts to obtain good likenesses of personages and correct accessories of their periods. He traveled much in England to make studies of old portraits and actual localities. At intervals came from his studio such pieces as 'The Red Cross Knight', 'Abraham Offering up Isaac', 'Hagar and Ishmael in the Wilderness', 'The Death of Major Peirson', 'The Arrest of Five Members of the Commons by Charles the First', 'The Siege of Gibraltar', 'The Surrender of Admiral DeWindter to Lord Camperdown', 'The Offer of the Crown to Lady Jane Grey by the Dukes of Northumberland and Suffolk', 'The Resurrection', and others. He continued to paint portraits, among them those of several members of the royal family and numerous British and American celebrities. Between 1776 and 1815 he sent forty-three paintings to exhibitions of the Royal Academy, of which he was elected an associate member in the former year. His election to full membership occurred in 1783.

The models were the artist's own handsome children, now seventeen years older than when they posed for The Copley Family. John, the boy hugging his mother in that painting, is the Red Cross Knight. Elizabeth, the daughter standing in the center of the family portrait, is Faith, and Mary, the infant on the sofa, is Hope. The Red Cross Knight, Copley's only painting inspired by literature, was shown at the Royal Academy in 1793.

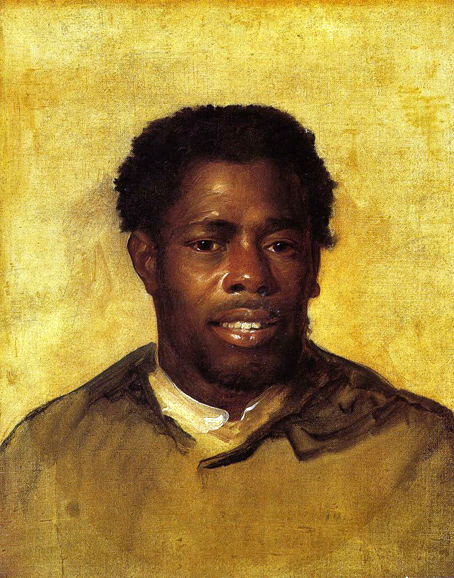

Lord Dunmore's Proclamation in November 1775 promised freedom to all slaves that could cross British lines and join the royal army. The strategy was successful; nearly 800 runaway slaves joined Dunmore nearly doubling his troops. One of the more prominent members of the regiment was runaway slave Titus, later known as Colonel Tye. A slave named Yellow Peter served in Dunmore's regiment and became known as Captain Peter.

From these runaways, Dunmore formed the Ethiopian Regiment. The regiment was trained in formation marching and musket shooting. On their uniforms, they proudly had embroidered the slogan, "Liberty to Slaves" in order to antagonize the liberty seeking patriots.

The Ethiopian Regiment easily overtook the Americans at Kemp's landing with the use of a surprise attack. Overconfident, Dunmore ordered the group to attack fortified positions at Norfolk. It was there that they suffered a debilitating defeat at the Battle of Great Bridge.

After their defeat, the regiment was forced to withdraw. After Dunmore's troops boarded onto the British fleet, many of the soldiers died of disease and others were evacuated and granted their freedom in exile.

-Demanding-the-Five-Members-in-the-House-of-Commons-in-1642.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

The effort with which Copley labored over his compositions was exemplary, but at times it may have injured his health and disposition. "He has been represented to me by some," wrote Cunningham, "as a peevish and peremptory man while others describe him as mild and unassuming." Both descriptions probably fitted Copley depending on his mood: he might be nervous from overwork and worry or in a normal condition. His granddaughter, Mrs. Amory, recalls that he usually painted continuously from early morning until twilight. In the evening his wife or a daughter read English literature for his benefit. He took but little exercise-probably not enough for health.

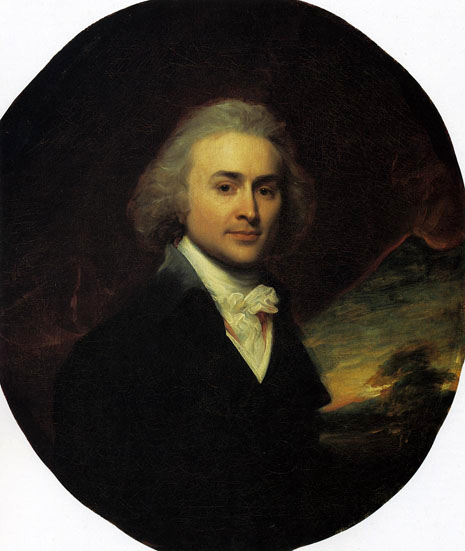

He would have liked to return to America but his professional routine prevented this. He was politically more liberal than were his relatives. He painted the Stars and Stripes over a ship in the background of 'Elkanah Watson's Portrait' on December 5, 1782, after listening to George III's speech formally acknowledging American independence. "He invited me into the studio," wrote Watson in his Journal, "and there, with a bold hand, a master's touch, and I believe an American heart, attached to the ship the Stars and Stripes; this was, I imagine, the first American flag hoisted in Old England." Copley's contacts with New England people continued to be many. He painted portraits of John Adams, John Quincy Adams, and other Bostonians who visited England. His daughter Elizabeth was married in August 1800 to Gardiner Greene of Boston, a wealthy gentleman whose descendants preserved much of the correspondence of the Copley family.

.jpg)

Prior to this marriage of his daughter, Copley had sold his Beacon Hill estate to a syndicate of speculators headed by Dr. Benjamin Joy. He felt himself victimized when he learned that the purchasers knew of a project of building the Massachusetts State House at the top of the hill, and he sent his son John Singleton Copley, Jr., then at the beginning of his brilliant legal career, to Boston in 1796 seeking to annul the arrangement. The letters which the future Lord Chancellor wrote during his visit to the United States are interesting reading but his quest was unsuccessful. "I do not believe," he wrote to his father, "that any person could have obtained from them one shilling more." Despite this report the artist made further efforts to recover his "farm." The subject of his grievance frequently recurs in the family correspondence, but it is not certain that Copley had any reason to feel himself defrauded. A memorandum prepared for him by Gardiner Greene stated that long after the land "had passed out of Copley's possession it, or a part of it, was offered at no higher price than was paid to his son." Allen Chamberlain, whose Beacon Hill gives a detailed summary of the complicated negotiations surrounding this purchase, holds that Copley was fairly compensated at a price three times what he had paid for property from which he had had rents of considerable amount.

In his last fifteen years, though painting persistently, Copley experienced much depression and disappointment. The Napoleonic Wars brought hard times. The household at 25 George Street was expensive to maintain. The education of a talented son was costly. It grieved the father that after the young barrister began to earn his way it became necessary to accept his help in supporting the home. Lord Campbell quotes the jurist as saying that "his father, having lived rather expensively, accumulated little for him." Mrs. Amory makes out a case for Mrs. Copley's admirable management, but it appears that a standard of living difficult to maintain in the changed circumstances made much borrowing inevitable. Copley was chagrined by the failure of his 'Equestrian Portrait of the Prince Regent' to "bring a financial return." Cunningham says, "No customer made his appearance for Charles and the impeached members." Other canvases involving years of labor were unsold. Troubles with engravers were many, whether the fault was theirs or the painter's. Copley's letters to his son-in-law in Boston usually concerned loans made to him and frequently extended.

The aging artist's physical and mental health produced anxiety. In 1810 he had a bad fall which kept him from painting for a month. He incessantly bewailed the loss of his Boston property. Mrs. Copley wrote on December 11, 1810: "Your father has been led to feel this affair (his unsuccessful litigation to recover the "farm") more sensibly from the present state of things in this country where every difficulty of living is increasing and the advantages arising from his profession are decreasing". In October 1811, Copley wrote to Greene in distress, craving an additional loan of 600 Pounds. And on March 4, 1812 he wrote: "I am still pursuing my profession in the hope that, at a future time, a proper amount will be realized from my works, either to myself or family, but at this moment all pursuits which are not among the essentials of life are at a stand". In August 1813, Mrs. Copley wrote that, although her husband was still painting, "he cannot apply himself as closely as he used to do." She reported in April 1814: "Your father enjoys his health but grows rather feeble, dislikes more and more to walk; but it is still pleasant for him to go on with his painting." In June 1815, the Copley's entertained as visitor John Quincy Adams, with whom they jubilantly discussed the new terms of peace between the United States and the United Kingdom. In the letter describing this visit the painter's infirmities are said to have been increased by "his cares and disappointments." A note of August 18, 1815, informed the Greene's that Copley while at dinner had had a paralytic stroke. He seemed at first to recover. Late in August his prognosis was favorable to his painting again. A second shock occurred, however, and he died on September 9, 1815. "He was perfectly resigned," wrote his daughter Mary, "and willing to die, and expressed his firm trust in God, through the merits of our Redeemer." He was buried in Highgate Cemetery in a tomb belonging to the Hutchinson family.

How deep into debt Copley had fallen in his latest years was hinted at in Mrs. Copley's letter of February 1, 1816, to Gardiner Greene in which she gave details of his assets and borrowings and predicted: "When the whole property is disposed of and applied toward the discharge of the debts a large deficiency must, it is feared, remain." The estate was settled by Copley's son, later Lord Lyndhurst, who maintained the establishment in George Street, supported his mother down to her death in 1836, and kept the ownership of many of the artist's unsold pictures until March 5, 1864, when they were sold at auction in London. Several of the works then dispersed are now in American collections.

Copley was the greatest and most influential painter in colonial America, producing about 350 works of art. With his startling likenesses of persons and things, he came to define a realist art tradition in America. His visual legacy extended throughout the nineteenth century in the American taste for the work of artists as diverse as Fitz Henry Lane and William Harnett. In Britain, while he continued to paint portraits for the elite, his great achievement was the development of contemporary history painting, which was a combination of reportage, idealism, and theatre. He was also one of the pioneers of the private exhibition, orchestrating shows and marketing prints of his own work to mass audiences that might otherwise attend exhibitions only at the Royal Academy, or who previously had not gone to exhibitions at all.

Source: Wikipedia

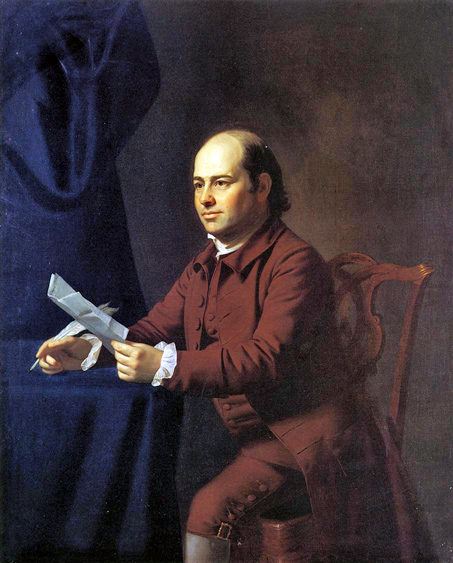

The artist painted three copies of this portrait so that each of the sitter's daughters could have one. This one is thought to have belonged to the third daughter. The prime version was painted, with a pendant pair of Admiral Samuel Barrington, to flank a panoramic painting of Howe's 'Relief of Gibraltar', 1782, all three originally being part of the presentation of Copley's vast painting of the 'Siege of Gibraltar' now in the Guildhall Art Gallery. The American-born artist was active as a portrait painter in Boston until 1774. After a year of study in Italy and following the outbreak of the American Revolution in 1775, he settled in London, where he spent the rest of his life. There he continued to paint portraits and innovatively combine portraiture with history painting.

_ca_1774.jpg)

_ca_1763.jpg)

_ca_1772.jpg)

_1770.jpg)

_ca_1764.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

While the faces in the portraits were their own, the sitters mixed and matched elements from Copley's array of props, including flowers, fruits, pets, drapery, and clothing. Sitters may have picked the poses and costumes from the portfolio of prints that Copley kept in his studio. They may also have admired other portraits in progress in the studio and expressed an interest in the same for themselves.

Lydia Lynde was born in Salem or Boston in 1741 and married Reverend William Walter, minister of Boston's Trinity Church, in 1766. To avoid the Revolution, Lydia and her Loyalist husband fled with their six children to Nova Scotia, returning to Boston in 1792. Lydia was the only known member of the Lynde or Walter family to sit for a Copley portrait, which may confirm speculation that Lydia's portrait marked a special occasion in the young woman's life.

Returning to Britain, Montgomerie became a Member of Parliament for the Scottish region of Ayrshire, serving intermittently up until 1796. That year, he was appointed Lord Lieutenant of Ayrshire. In 1798, after succeeding to the earldom, he was elected a representative peer and received a seat in the House of Lords. In 1806, he was created Baron Ardrossan in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. In 1814, he was made a Knight of the Thistle.

_1765.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_1753.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Both the material richness of the sitter's stylish dress and her air of languorous if well-bred ease advertise the wealth and social standing of her family. The identity of the sitter in 'Portrait of a Lady in a Blue Dress', which descended in the family of the artist, has never been known. Scholars have suggested that she is Margaret Sanford (Mrs. Thomas Hutchinson Sr.) or her daughter-in-law Sarah Oliver (Mrs. Thomas Hutchinson Jr.). But she also bears a close resemblance to Deborah Scollay, the subject of a miniature painting Copley made around 1762. In several instances Copley painted miniature portraits in conjunction with full-size likenesses. Moreover, in 1763, the year Copley painted Lady in a Blue Dress, he also executed portraits of Deborah's parents. The artist had close professional ties to both the Hutchinson's and the Scollay's, but while his documented connection with the former family ceased in 1761, Scollay relations were commissioning portraits from him as late as 1774, the year he closed his Boston studio and departed for Europe.

_1771.jpg)

In France, only the aristocracy had their portraits painted in such apparel. Yet it is the prerogative of the bourgeois Rebecca Boylston to adopt this dress as a sign of her confidence and imperturbable dignity. The thin fabric also gives Copley a chance to emphasize Rebecca's slender figure, showing her firm and youthful breasts beneath the satin sheen. At the same time, in the intelligent and slightly mocking gaze of her dark eyes, Copley suggests that this is a woman of experience. Six years later, Rebecca married a wealthy landowner who commissioned Copley to paint a second portrait of his beautiful wife.

The fact that Copley did not portray his model in the stiffly prestigious setting of a salon, but in a park, further underlines the natural charm of this millionaire. There is nothing contrived or affected in the way she holds the little basket of rose blossoms in her hands; it is almost as though she had just picked the flowers in the famous gardens of the Boylston villa. The slightly cramped Rococo attitude of Copley's earlier paintings succumbs here to a new and distinctly American directness and spontaneity.

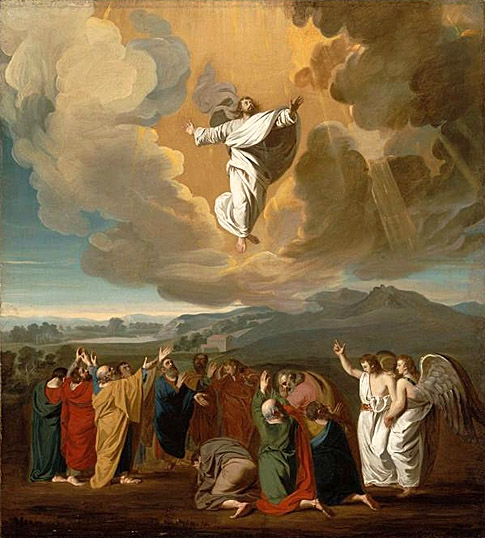

The narrative of the incident is clearly illustrated in this composition. Strong lighting and bold colors emphasize Christ's importance, and the other apostles are suitably varied in pose and appearance. Some of these compositional elements were taken from an engraving of Rubens's painting Christ giving the Keys to Saint Peter.

Franklin Kelly, Curator of American and British Paintings

National Gallery of Art, Washington

.jpg)

Source: Web Gallery of Art

Source: Art Renewal Center

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.