American, Painter, Sculptor, and Draftsman

1856 - 1925

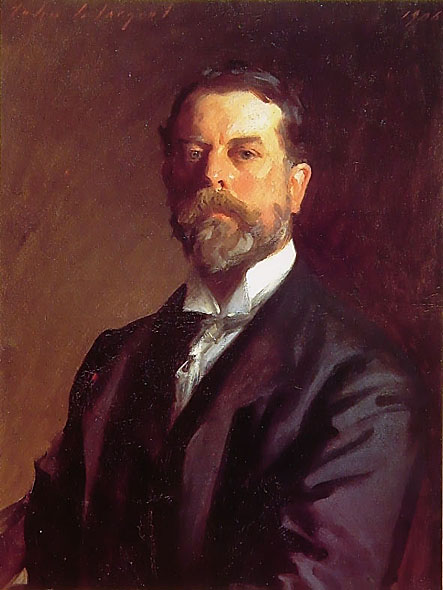

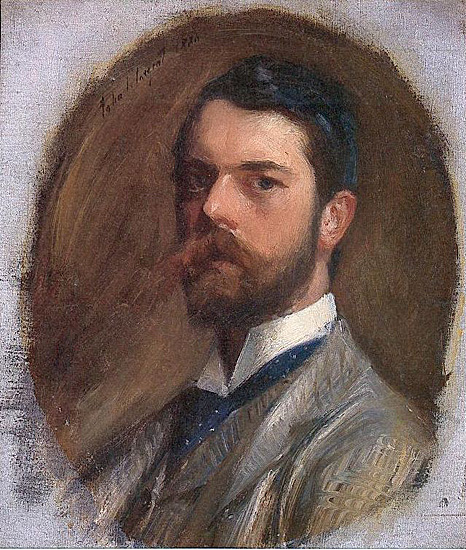

John Singer Sargent (January 12, 1856 - April 14, 1925) was the most successful portrait painter of his era, as well as a gifted landscape painter and watercolorist. Sargent was born in Florence, Italy to American parents. He studied in Italy and Germany, and then in Paris under Emile Auguste Carolus-Duran.

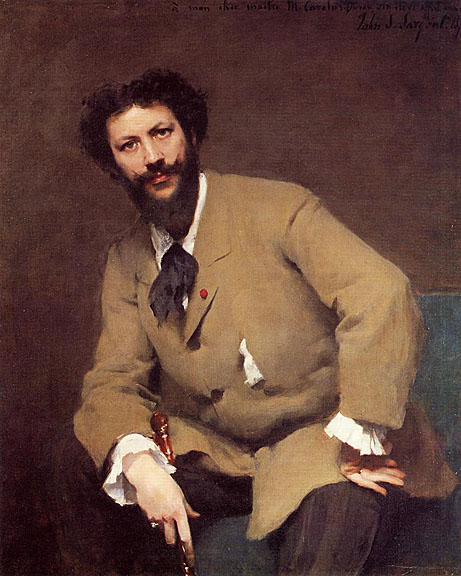

Sargent studied with Carolus-Duran, whose influence would be pivotal, from 1874-1878. Carolus-Duran's atelier was progressive, dispensing with the traditional academic approach which required careful drawing and underpainting, in favor of the alla prima method of working directly on the canvas with a loaded brush, derived from Diego Velázquez. It was an approach which relied on the proper placement of tones of paint.

In 1879 Sargent painted a portrait of Carolus-Duran; the virtuoso effort met with public approval, and announced the direction his mature work would take. Its showing at the Paris Salon was both a tribute to his teacher and an advertisement for portrait commissions. Of Sargent's early work, Henry James wrote that the artist offered 'the slightly "uncanny" spectacle of a talent which on the very threshold of its career has nothing more to learn'.

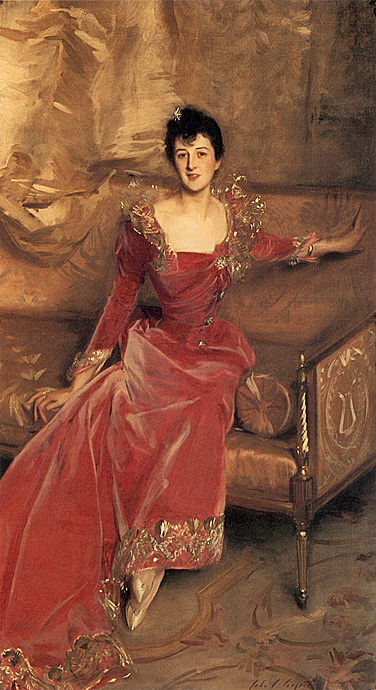

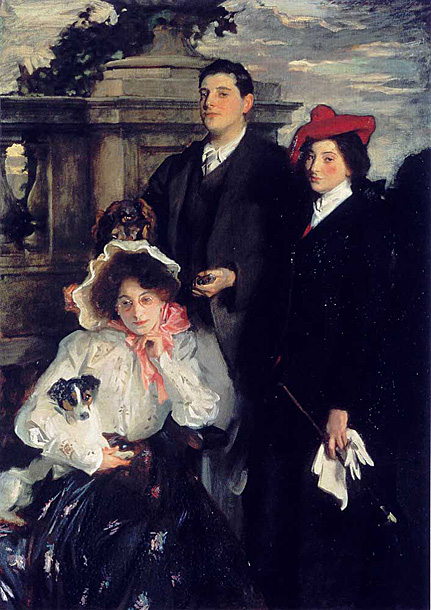

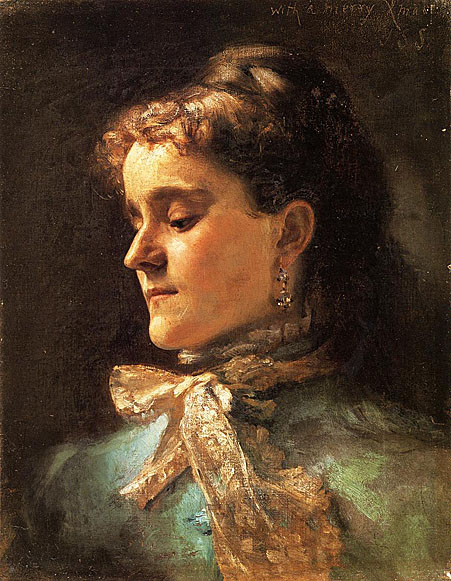

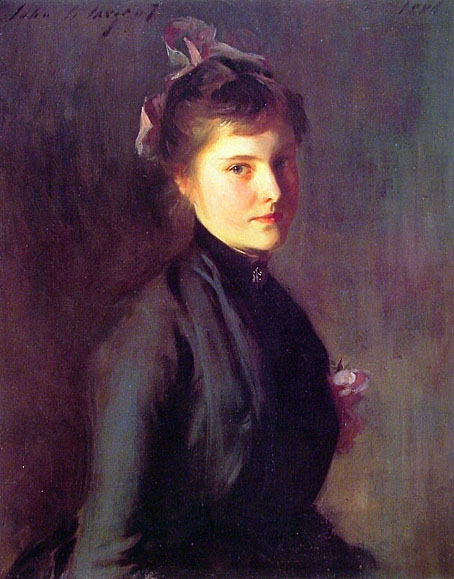

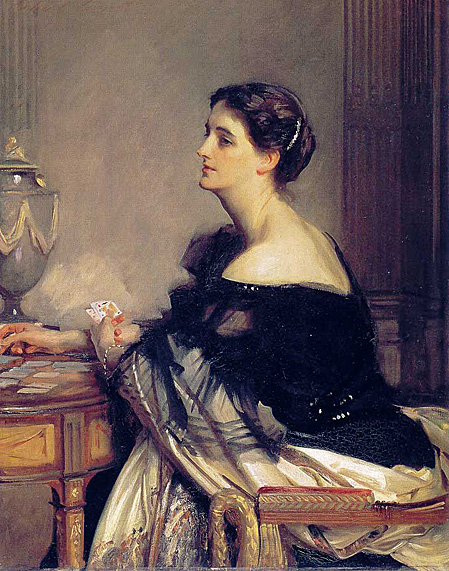

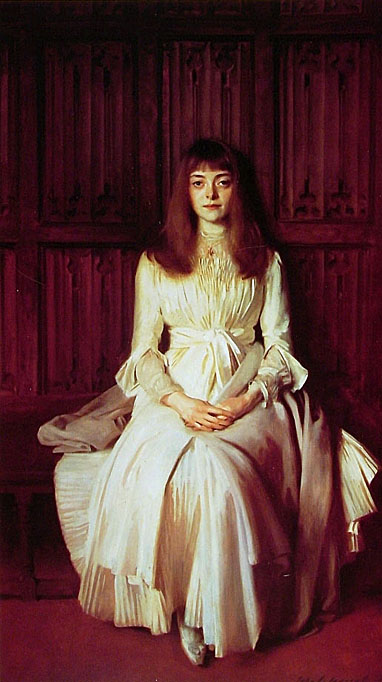

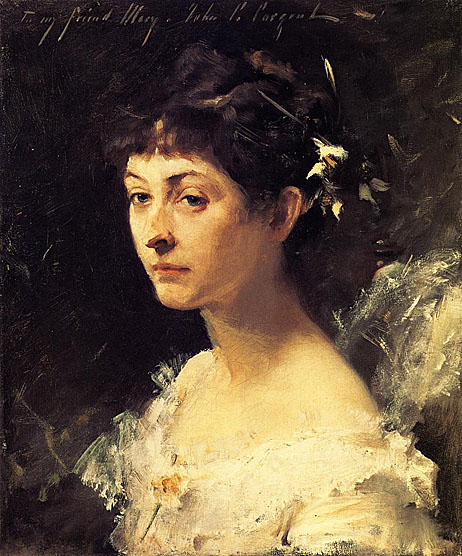

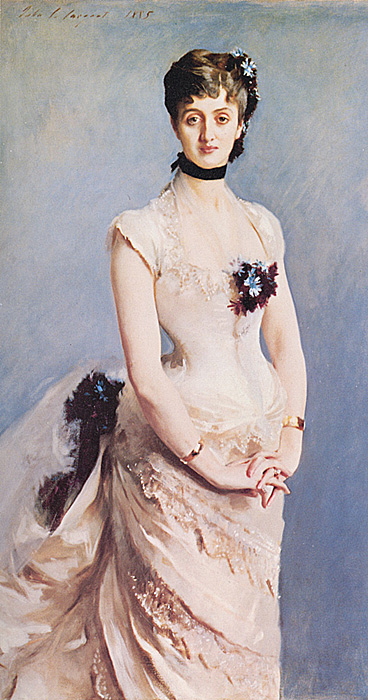

In the early 1880s Sargent regularly exhibited portraits at the Salon, and these were mostly full-length portrayals of women: Madame Edouard Pailleron in 1880, Madame Ramón Subercaseaux in 1881, and Lady with the Rose, 1882. He continued to receive positive critical notice.

In 1869, he produced the Gymnase theatre's Les Faux ménages, a four act comedy depending for its interest on the pathetic devotion of the Magdalene of the story. L'Étincelle (1879), a brilliant one-act comedy, secured another success, and in 1881 with Le Monde où l'on s'amuse Pailleron produced one of the most strikingly successful pieces of the period. The play ridiculed contemporary academic society, and was filled with transparent allusions to well-known people. None of his subsequent efforts achieved so great a success. Pailleron was elected to the Académie française in 1882.

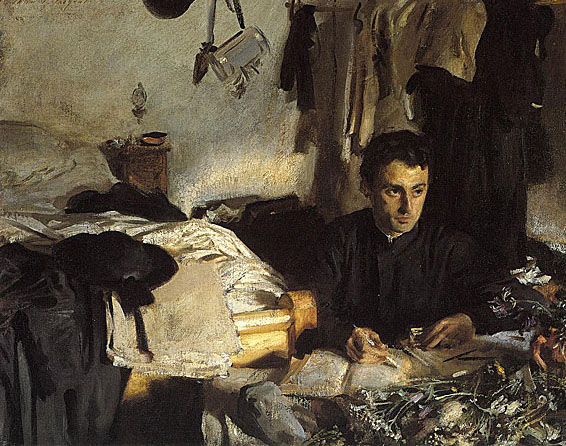

In 1880 Sargent showed this painting along with the subject painting Fumée d'Ambre Gris at the Paris salon.

The autumn setting with the yellow fallen leafs and wild flowers gives this a more unusual look for this formal portrait. Sargent had been lucky in patrons. The Paillerons were open to a more artistic interpretation of portraiture. The sitter was born Marie Buloz (1840-1913). Her father was the editor of the journal Revue des Deux Mondes and her husband was a successful dramatist and poet. Still, this wasn't that far out of the vogue of the time.

It was in Paris during the Spring of 1880 that Sargent painted my portrait which won the prize the following year (2nd place at the Salon). Shortly before this, when we were visiting the annual exposition, Ramon noted a small picture of an oriental woman perfuming her clothing with aromatic incense from a brazier (Fumee d'Ambre Gris). This picture was in clear colors - white and grey. In the catalogue, he located the name of the artist, John S. Sargent, and noted he was from the United States. A few days later, arrangements were made for Sargent to paint my portrait. We went to his atelier and found it to be very poor and bohemian while the artist himself seemed a very attractive gentleman and therefore we treated him as a real friend. He was very young at the time, only 24 years of age, but he was a man of very pleasant manners. He came to our apartment to arrange the setting, clothing and other details. He studied every single detail very carefully and was entirely free to arrange the composition of the portrait as he wished. It was not difficult to pose for him as his hours of work were neither long nor heavy. His way of painting was light, as his work showed afterwards. He concentrated on each detail and took great care of the effect of each object and color. He was a man of great skill who felt secure and at ease while working. He was very fond of music and had me play for him. He brought me several pieces from Gottschalk, music composer, whom he admired very much, specially his interpretations of Spanish and South American dances. He had been in Spain a short time and everything about that country left its impressions on him and from it he drew his inspirations. His teacher was Carolus Duran, and from him he became a great admirer of the great Spaniard Velazquez.

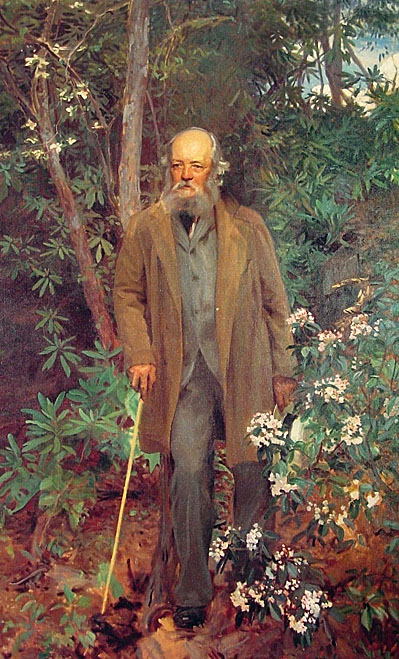

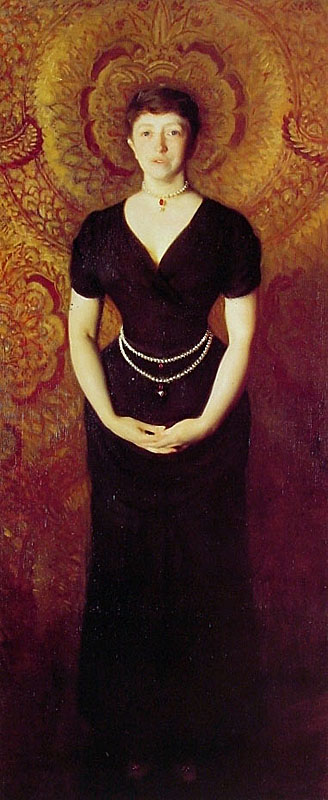

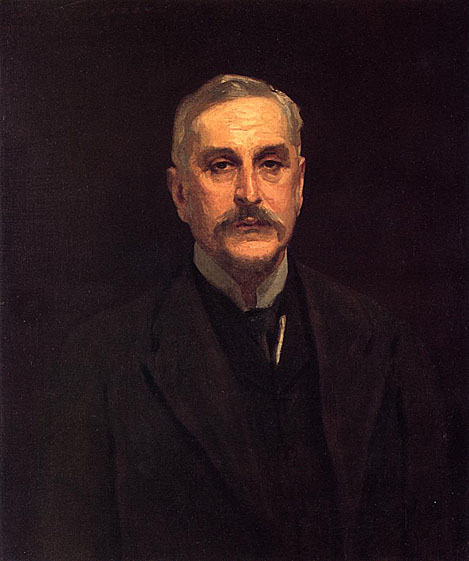

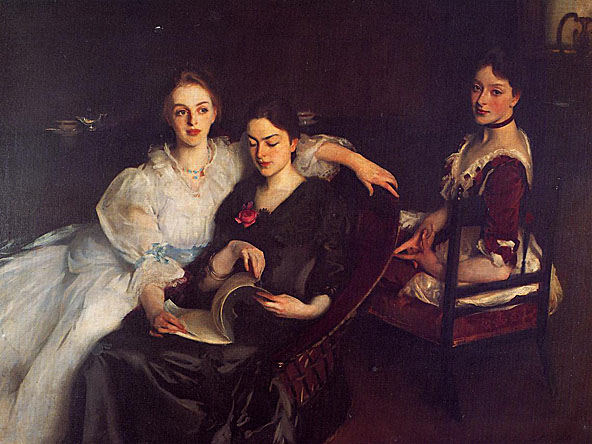

Frederick Law Olmsted, 1895, is one of Sargent's best portraits revealing the individuality and personality of the sitters; his most ardent admirers think he is matched in this only by Velázquez, who was one of Sargent's great influences. The Spanish master's spell is apparent in Sargent's The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit, 1882, a haunting interior which echoes Velázquez' Las Meninas. Sargent's Portrait of Madame X, done in 1884, is now considered one of his best works, and was the artist's personal favorite; eventually Sargent sold it to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. However, at the time it was unveiled in Paris at the 1884 Salon, it aroused such a negative reaction that it prompted Sargent to move to London. Prior to the Madame X Scandal of 1884, he had painted exotic beauties such as Rosina Ferrara of Capri, and the Spanish expatriate model, Carmela Bertagna, but the earlier pictures had not been intended for broad public reception.

"When I first saw this picture I found it rather odd myself. I felt the girls are curiously isolated from each other even before I read Charteris's account. The title of the painting clearly indicates that these are daughters, but it was my first inclination that the front two girls must be the daughters -- but what am I to make of the rear two girls? Why would he paint them in such a fashion? They are both clearly dressed in very similar clothes, almost a uniform -- could they be children of servants? The one in profile is almost unintelligible as if he was intentionally de-emphasizing the two from us. Why would he do this? Were the daughters close to the servants? Were they playmates? Why would they even be included in the picture?

As always (or nearly so) my first inclination was almost totally wrong. All four children, it turns out, are the daughters of Edward Darley Boit. But instead of answering questions, for me, it only raised more -- why are the rear daughters so obviously beyond the foreground of what one might expect of a portrait painting? Do you feel a sense of melancholy here? I did."

The following is from John Sargent, by Hon Evan Charteris, first published by Benjamin Blom, Inc. NY, in 1927, two years after the death of Sargent:

"In 1883 Sargent had begun a portrait which was to have a good deal of influence on his career. As far back as 1881 he met Madame Gautreau in Paris society, where she moved rather conspicuously, shining as a star of considerable beauty, and drawing attention as to one dressed in advance of her epoch. It was the period in which in London the professional beauty, with all the specialization which the term connoted, was recognized as having a definite role in social hierarchy. Madame Gautreau occupied a corresponding position in Paris. Immediately after meeting her, Sargent wrote to his friend del Castillo to find out if he could do anything to induce Madame Gautreau to sit [for] him. 'I have.' he wrote, 'a great desire to paint her portrait and have reason to think she would allow it and is waiting for someone to propose this homage to her beauty. If you are 'bien avec elle' and will see her in Paris you might tell her that I am a man of prodigious talent.'

"The necessary preliminaries were arranged, and the disillusionment seems to have begun quickly, for after the first few sittings he wrote to Vernon Lee from Nice on February 10 (1883): 'In a few days I shall be back in Paris, tackling my other 'envoi,' the Portrait of a Great Beauty. Do you object to people who are 'fardeés' to the extent of being uniform lavender or blotting-paper color all over? If so you would not care for my sitter; but she has the most beautiful lines, and if the lavender or chlorate of potash-lozenge color be pretty in itself I should be more than pleased.'

"In another letter, and again to Vernon Lee, he wrote: 'Your letter has just reached me still in this country house (Les Chêes Parramé) struggling with the unpaintable beauty and hopeless laziness of Madame Gaureau.'

"Even when the picture was nearing completion he was assailed by misgivings.'My portrait!' he wrote to Castillo, 'it is much changed and far more advanced than when you last saw it. One day I was dissatisfied with it and dashed a tone of light rose over the former gloomy background. I turned the picture upside down, retired to the other end of the studio and looked at it under my arm. Vast improvement. The élancée figure of the model shows to much greater advantage. The picture is framed and on a great easel, and Carolus has been to see it and said: 'Vous pouvez l'envoyer au Salon avec confiance.' Encouraging, but false. I have made up my mind to be refused.'

"The picture was accepted for the Salon of 1884. Varnishing day did nothing to assure the painter. On the opening day he was in a state of extreme nervousness. It was the seventh successive year in which he had exhibited. Every Salon had seen the critics more favorable, the public more ready to applaud. But without suggesting that the critics and the public of Paris are fickle, it is probably fair to say that popularity, fame and reputation are more subject to violent fluctuations there than other European capitals. This, at any rate, was to be Sargent's experience.

"The doors of the Salon were hardly open before the picture was damned. The public took upon themselves to inveigh against the flagrant insufficiency, judged by prevailing standards, of the sitters clothing; the critics fell foul of the execution. The Parisian public is always vocal and expressive.

The Salon was in an uproar. Here was an occasion such as they had not had since Le D'jeuner sur l'Herbe, L'Olympia and the Exhibition of Independents. The onslaught was led the lady's relatives. A demand was made that the picture should be withdrawn. It is not among the least of the curiosities of human nature, that while an individual will confess and even call attention to his own failings, he will deeply resent the same office being undertaken by someone else. So it was with the dress of Madame Gautreau. Here the distinguished artist was proclaimed to the public in paint a fact about herself which she had hitherto never made any attempt to conceal, one which had, indeed, formed one of her many social assets. Her sentiment was profound. If the picture could not be withdrawn, the family might at least bide its time, wait till the Salon was closed, the picture delivered, and then by destroying, blot it as an unclean thing from the records of the family. Anticipating this, Sargent, before the exhibition was over, took it away himself. After remaining many years in his studio it now figures as one of the glories of the Metropolitan Museum in New York."

"The scene at the Salon is described in a letter written by Sargent's friend and fellow-painter, Ralph Curtis, to his parents. It will be noted that at a certain point Sargent's forbearance gave way and his pugnacity . . . burst out:

"Sargent, who was twenty-eight, had been working for ten years in Paris. The Salon of 1884 was to have been a culmination of his efforts. He had painted what is now recognized as a masterpiece, displaying excellence which he was perhaps never to surpass. It had been received with a storm of abuse. Paris, which had been smooth and well-disposed and encouraging, had turned, and like a child splintering a plaything, had dealt a violent blow at its recognized favorite. He was not in the least in doubt of his own art, but he was always sensitive to atmosphere, always easily affected by unsympathetic environment. Paris had awakened suddenly one May morning in an uncongenial mood, its friendliness hidden in clouds; the accord which prevailed between painter and public was at an end."

"Vernon Lee summed it up this way: ". . . it seemed as if for years, he was engrossed in perpetually dissatisfied (and, as regards to Parisian public, disastrous) attempts to render adequately the 'strange, weird, fantastic, curious' beauty of that peacock-woman, Mme. Gautreau."

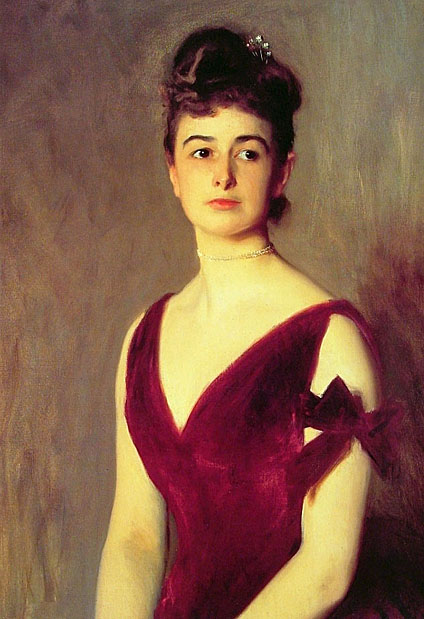

Before his arrival in England, Sargent began sending paintings for exhibition at the Royal Academy. These included the portraits of Dr. Pozzi at Home, 1881, a flamboyant essay in red, and the more traditional Mrs. Henry White, 1883. The ensuing portrait commissions encouraged Sargent to finalize his move to London in 1886. His first major success at the Royal Academy came in 1887, with the enthusiastic response to Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose, a large piece, painted on site, of two young girls lighting lanterns in an English garden. The painting was immediately purchased by the Tate Gallery. In 1894 Sargent was elected an associate of the Royal Academy, and was made a full member three years later. In the 1890s he averaged fourteen portrait commissions per year, none more beautiful than the genteel Lady Agnew of Lochnaw, 1892. As a portrait painter in the grand manner, Sargent's success was unmatched; his subjects were at once ennobled and often possessed of nervous energy (Mrs. Hugh Hammersley, 1892). With little fear of contradiction, Sargent was referred to as 'the Van Dyck of our times'.

The artist, John Singer Sargent was already a master of his craft - which, in 1881, was the careful selection and portrayal of the beau monde of Parisian society. Every aspect of his canvasses was carefully rehearsed and thought through - the exposure of flesh and musculature, the weight and significance of apparently unremarkable pieces of furniture or jewelry, there is a purpose and significance in everything included - and even in the very omissions from what appears on the canvass. A shoulder strap - a coat - the carvings on the almost hidden leg of a table - nothing was incidental.

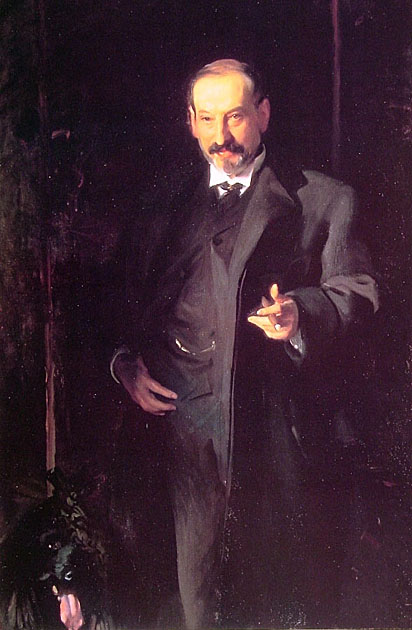

And then there is the selection of his subjects. Sargent was pro-active in going after the faces he wanted - and he was drawn, like much of Paris society - to Dr Samuel Jean Pozzi. This particular subject was an object of fascination and fevered gossip - a man renowned for his beauty - his work as a gynecologist to the ladies of the haute bourgeoisie - and his numerous and well-reported love affairs. A male coquette of immense vanity he reveled in the sobriquet given him by one of his lovers - the actress Sarah Berhardt - "Docteur Dieu". One can easily imagine Parisiennes of the haute bourgeoisie going to any lengths to secure the attentions of this particular "Dieu". His fame and notoriety lay not only in his face and frame - but also, of course, in his hands. And Sargent shows us his two fine, bird-like hands - slender, feminine and sensitive. Perhaps one could even divine his profession from the way the hands are portrayed - those long, busy fingers which seem to have a separate existence from the rest of Pozzi's calm, cerebral, and supremely controlled, form?

Pozzi was a man supremely confident in himself and his status and at the top of his profession. He made his own rules and invented his own procedures - the most extraordinary example perhaps being his insistence on carrying out bi-manual ovarine examinations. To Paris society in the 1880s it only served to make Docteur Dieu even more alluring. He did not hesitate to give demonstrations so others could see how a two handed gynacological examination could be carried out. And of course he did not use gloves or any form of barrier protection - the contact was intimate, unsheathed and naked.

Those who shared his passion for gynecological invasion were admitted to his private band that he called, with clear acknowledgement of the clitoris: "The League of the Rose". And he was their self-appointed High Priest. He stands before a heavy velvet curtain in his theatre of operations - his bedroom. He wears a dressing gown, heavy tassels hanging down between his legs like one testes dangling above the other - a broad phallic shadow lying to one side. Beneath the gown, his nightshirt is dazzling white, romantic, Byronesque. His right hand is clasped to his breast in the position of sincerita - a common gesture in 17th century portraits of noblemen - but here instead of the open straight-fingered hand there is a twist, the index finger bent over and the thumb hooked into the gown - an indication that here "sincerita" is not really present - a facsimile perhaps, hiding the Doctor's true intent.

Pozzi stands like Don Juan - a corrupt pleasure-seeker who even on being shown the open doors of hell refuses to repent. The pose is melodramatic - he looks down unconcerned and calm towards a bright source of light off frame to the right - the fire of his own damnation? Sargent seems at once fascinated and repulsed by the pleasure-seeking - pleasure-giving - scandal living and morally corrupt Dr Pozzi. This man was nothing less than the High Priest of the Vagina - and then it strikes you - Sargent has even gone as far as to show even this. Stand back and half close your eyes and Pozzi's body can also be seen as a fleshy hollow or void at the centre of the frame - the whole picture is itself both a portrait of Pozzi and a huge representation of a vagina with the clittoris head - the "rose" - proudly standing at the top.

In May 1882 "Dr Pozzi at Home" was exhibited and quickly became the best known of all Sargent's work to that time. The venue was London where the most prominent commentator on art (and in particular paintings) was then a young self-appointed arbiter of taste, named Oscar Wilde. Within two years Sargent was to be a guest at Wilde's wedding. We cannot say for certain whether Wilde himself was drawn to Pozzi's feet and marveled at the work and its subject - but it is surely inconceivable that the most famous work of his close friend would escape his attention and scrutiny.

It would be a few more years before Wilde would pen "The Picture of Dorian Gray" but perhaps the seeds were already being sown. "Dr Pozzi at Home" seems a perfect illustration for Wilde's assertion that "The moral life of a man forms part of the subject-matter of the artist".

And if we were to look for a prime example of a character who, like, Dorian Gray, reveled in his beauty at the cost of his immortal soul - need we look further than Dr Samuel Jean Pozzi?

ADAM SUTCLIFFE

(c) Copyright 2001

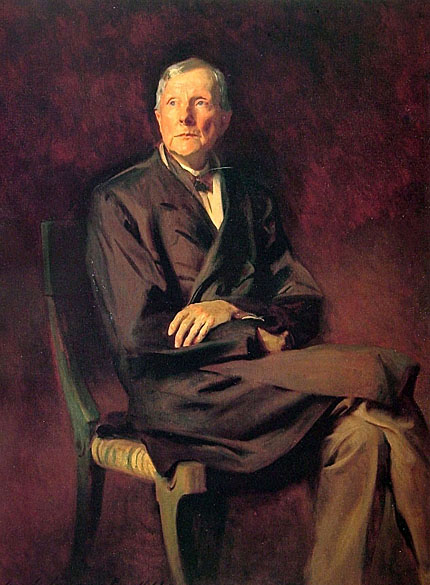

Sargent painted a series of three portraits of Robert Louis Stevenson. The second, Portrait of Robert Louis Stevenson and his Wife (1885), was one of his best known. He also completed portraits of two U.S. presidents: Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson as well as John D. Rockefeller..

When Sargent painted Stevenson he wrote to Henry James and said that RLS "seemed to me the most intense creature I had ever met."

Sargent was twenty-nine years old at the time and RLS was thirty-four. it was less than one year prior to the publication of RLS's hugely popular "masterpiece" The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886). It is fun to think that possibly Robert Louis Stevenson might have been working on the book, if not thinking about it, at the same time that Sargent painted him.

But Sargent wasn't going to have an easy time with the Rough Rider, trusts busting, Big Stick carrying, Panama Canal building President. Teddy, having been stung once, would take no nonsense from the artist no matter how renowned he was.

The two men surveyed the house and Sargent attempted to make sketches of his subject in various rooms trying to find the best lighting and pose, but nothing was working. This didn't sit well with the ever restless President. As they climbed the stairs to try and find a better arrangement on the second level, Teddy brusquely remarked that he didn't think Sargent had a clue as to what he wanted. Sargent, also loosing patients, shot back that he didn't think the President knew what was needed to pose for a portrait. Roosevelt, whom by then had reached the landing, planted his hand on the balustrade post, turned onto the ascending artist and said, "Don't I!"

Sargent had found his picture.

All I know is that Hugh Lane took up an idea started by another man (who repented) that he would give 10,000 pounds to the Red Cross if I would paint his portrait (the first man's). Hugh Lane of course had some other idea about whose portrait it was to be. Then Hugh Lane was drowned in the Lusitania]. He had left his estate to the National Gallery of Ireland, who had handed over the 10,000 pounds to the Red Cross in 1916 and have lately decided the portrait should be that of President Wilson.

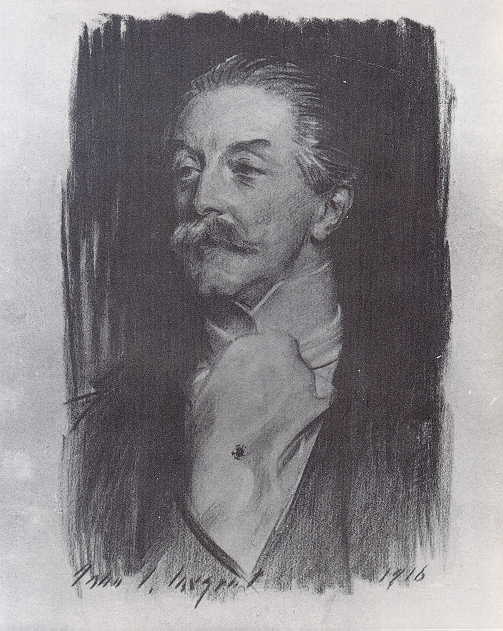

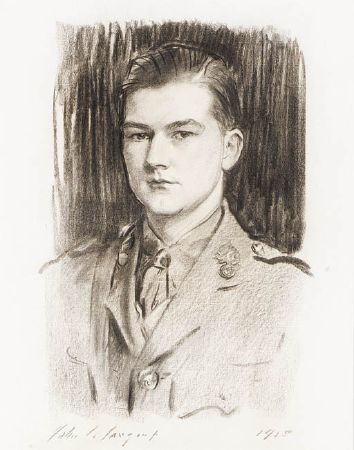

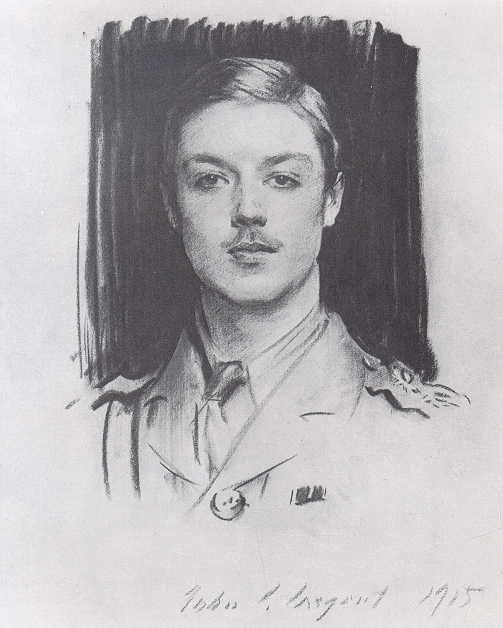

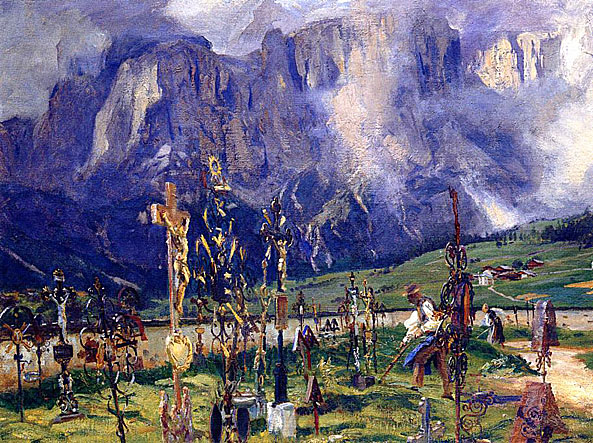

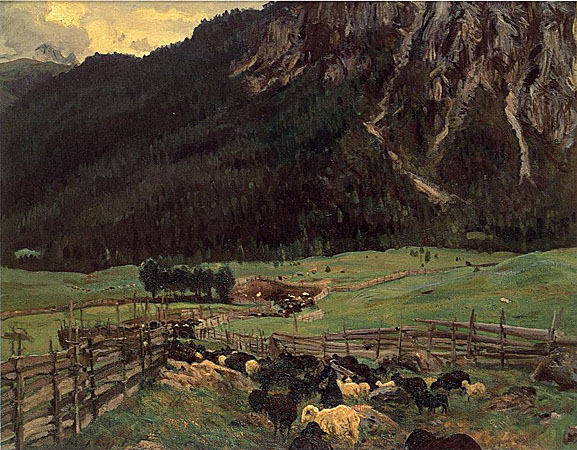

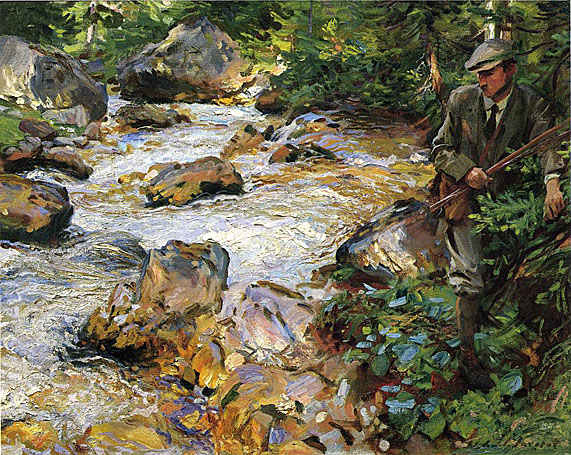

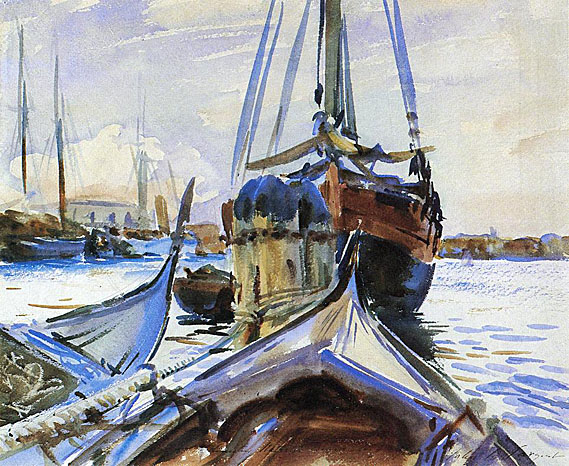

During the greater part of Sargent's career, he created roughly 900 oil paintings and more than 2,000 watercolors, as well as countless sketches and charcoal drawings. From 1907 on Sargent forsook portrait painting and focused on landscapes in his later years; he also sculpted later in life. His oeuvre documents worldwide travel, from Venice to the Tyrol, Corfu, Montana and Florida, and each destination offered pictorial treasure. As a concession to the insatiable demand of wealthy patrons for portraits, however, he continued to dash off rapid charcoal portrait sketches for them, which he called "Mugs". Forty-six of these, spanning the years 1890-1916, were exhibited at the Royal Society of Portrait Painters in 1916.

Date: Sat, 22 May 2004

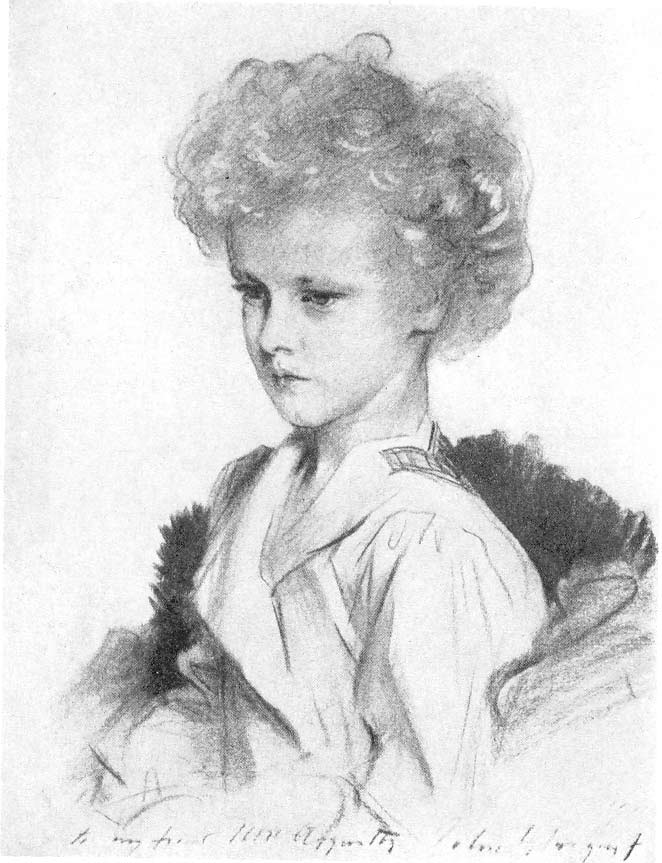

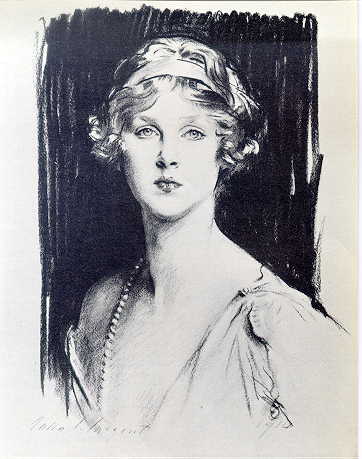

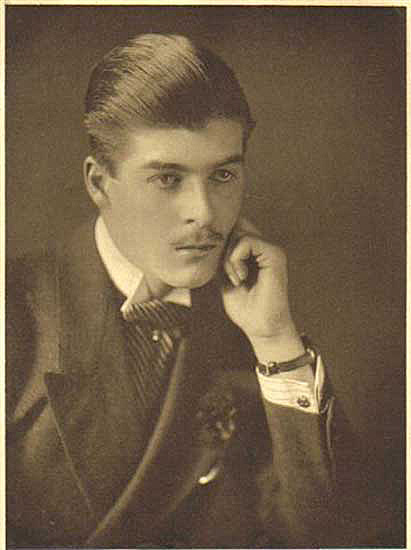

After 24 years my wife and I finally had a chance to visit her home in Paris from which her daughter had recently been removed to a nursing home. We met a relative who by chance was in town and looked around the apartment - it was a kind of shrine to Elizabeth Asquith Bibesco as far as I could see - everything that had been on the walls in 1920 was still on the walls - including two portrait drawings by Sargent - one of Elizabeth Asquith and the other of her brother Anthony (the movie director) done in 1914 when she was 17 and he was 12.

Unthinkingly I only snapped a picture of Elizabeth (I was too excited to finally see the Vuillard of Elizabeth to look at much else. Anyway here is the portrait of Elizabeth Asquith (did she use it in the 1916 show she organized?) taken through glass at a bit of an angle. The two portraits (image size) were probably about 24 X 16 inches and were framed to show lots of margin.

Perhaps you remember my interest in Augustus John's "Princess Bibesco".

Regards, Paul

His father was the British Prime Minister and he grew up in 10 Downing Street from when he was six years old to fifteen (1908-1916).

To the dismay of his political father, however, he didn't take after his half siblings who where into politics or the law, but more after his mother who was more of a free spirit and artistically minded.

He did go to Oxford, like his father had, and studied the classics. After graduating he traveled to Hollywood at a time when things were really taking off and stayed with Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks, Sr. -- How about having Charlie Chaplin as a neighbor, nice, huh? When he returned to England the only job he could get was at the lowest level (tea boy) but with his family connections he moved up pretty quickly and by the age of twenty-five co-directed his first movie "Shooting Stars" (1928) with A.V. Bramble which today apparently is widely considered to a small classic and Britain's greatest silent film -- at the time his salary was to £2 a week. His father thought the whole thing was a joke and was waiting for him to grow up.

Puffin continued on, regardless; but the film industry was going through some substantial growing pains into talkies and he struggled with the critics (artistically) who called his films too arty.

It seems his second break came in 1938 when he was allowed to co-direct the movie "Pygmalion" because of his close relations with George Bernard Shaw who wrote the play (1914). The movie was a hit staring Leslie Howard (this success, however, would later totally be eclipse by another adaptation of Shaw's work under the musical named "My Fair Lady" (1964) with Rex Harrison and Audrey Hepburn.)

But in 1938, Puffin was back in the drivers seat and he would never look back, Over the course of the next quarter century he would crank out a number of admirable films and would work with some of the greatest actors of the time: Laurence Olivier, Edith Evans, Rex Harrison, Elizabeth Taylor, Richard Burton, Shirley MacLaine, Ingrid Bergman, Sophia Loren, Peter Sellers, Leslie Caron, David Niven, Dirk Bogarde.

He wasn't considered a Great Director, and after the time of his death a lot of his work was looked down on as not being cutting edge, but he was a Good Director and worked in what was England's equivalent of the Hollywood studio system - cranking them out.

I personally haven't seen a lot of his work - I intend to, but from what I can gather some of his more notable films also included: "Quiet Wedding" (1940); "The Importance of Being Earnest" (1952) a theatrical version of Oscar Wilde's play; "The Winslow Boy" (1948); "Carrington VC" (1954); "The Millionairess" (1960);and "The Way To The Stars" (1945) - a movie I have seen but it was so long ago I don't really remember much other than it was a WWII movie.

Apparently he had a kind heart and was generous to a fault and he struggled with alcoholism and died from complications from that - I think.

I wonder if his father ever came around to appreciating his choice of careers.

"We went to the Grafton Gallery to see the exhibition of Sargent drawings. It's a real nightmare to see so many of one's friends so blatantly depicted staring at one from four walls - I think the one of me presents the foulest woman I have ever seen."

After two years the embattled Mr. Smyth gave in, and Ethel went to Leipzig, where her larger-than-life personality found an aesthetic outlet in the development of a Brahmsian idiom. She gained some recognition in England with the performance of her Mass in D for chorus and orchestra in 1893, and struggled to get her operas performed.

A woman of boisterous vitality who fell prey to inconvenient passions for persons of both sexes, Smyth was affectionately caricatured in E.F. Benson's Dodo novels and mocked by Virginia Woolf. In 1910, Smyth met Emmaline Pankhurst, the founder of the British women's suffrage movement and head of the militant and extremely well organized Women's Social and Political Union. Struck by Mrs. Pankhurst's mesmerizing public speeches, Smyth pledged to give up music for two years and devote herself to the cause of votes for women.

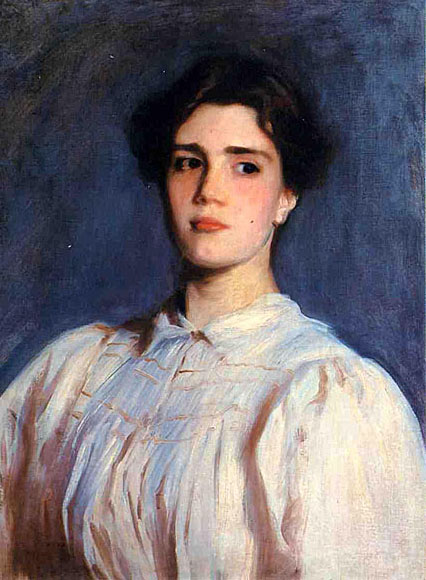

If I'm guessing their ages correctly, Lady Elcho, would be the one on our left, she is Mary Constance neè Wyndham (1862-1937) -- the oldest. She married Hugo Richard Wemyss Charteris Douglas, Lord Echo in 1883. Her brother-in-law was the Honorable Evan Charteris who did that first biography of Sargent shortly after John's death. Mary would have been roughly thirty-seven at the time of sitting.

Mrs Adeane, would be the one standing, she was Madeline neè Wyndham (1869-1941) and she married Charles R.W. Adean in 1889. He was the Lord Lieutenant of Cambridgeshire. Madeline would have been about thirty.

Mrs. Tennant, sitting on the right and obviously the youngest, was Pamela neè Wyndham (1871-1928). She married Edward Tennant in 1895 and she became Lady Glenconner when her husband took title in 1911. When her husband died in 1920, she married Viscount Grey of Fallodon in 1922. Pamela would have been about twenty-eight at the time of sitting.

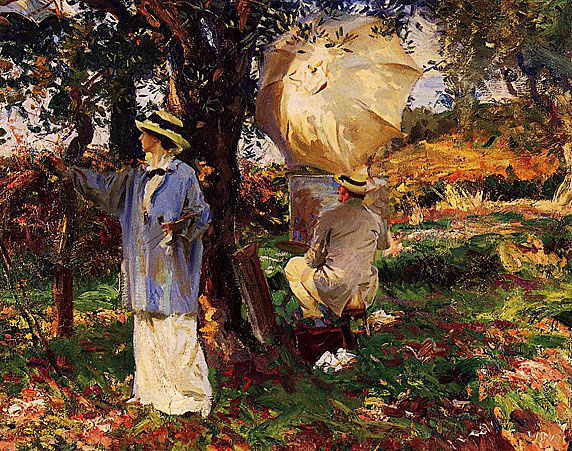

Sargent is usually not thought of as an Impressionist painter, but he sometimes used impressionistic techniques to great effect, and his Claude Monet Painting at the Edge of a Wood is rendered in his own version of the impressionist style.

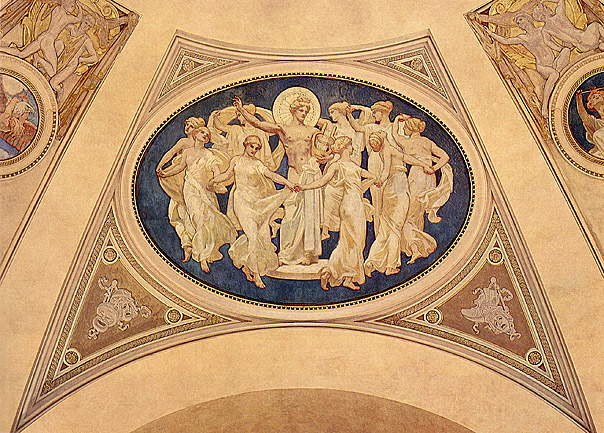

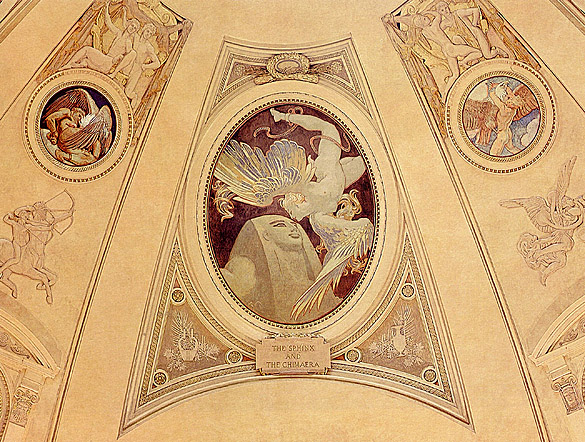

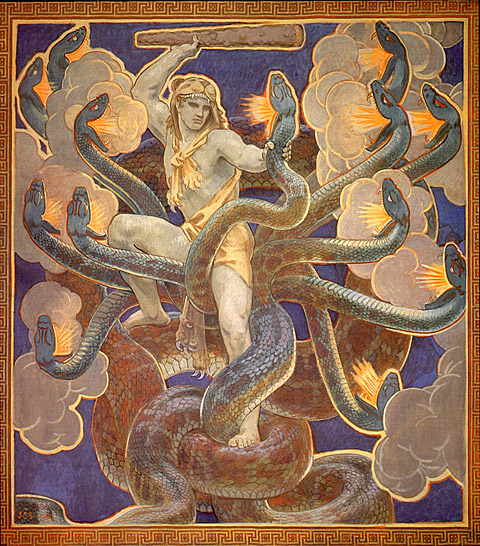

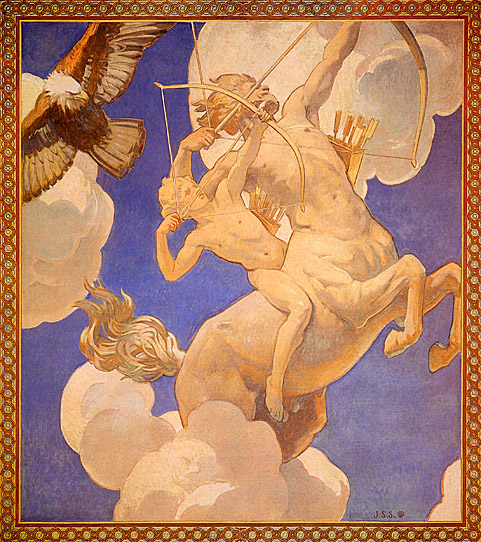

Although Sargent was an American expatriate, he returned to the United States many times, often to answer the demand for commissioned portraits. Many of his most important works are in museums in the U.S.; in 1909 he exhibited eighty-six watercolors in New York City, eighty-three of which were bought by the Brooklyn Museum. His mural decorations grace the Boston Public Library. For this commission, a series of oils on the theme of The Triumph of Religion that were attached to the walls of the library by means of marouflage, Sargent made numerous visits to the United States in the last decade of his life, including a stay of two full years from 1915-1917.

A brilliant painter of society portraits, John Singer Sargent also devoted many years at the height of his career to a project of an entirely different order: an ambitious, multi-media decoration titled Triumph of Religion (1890-1919) for the Boston Public Library. The library cycle Sargent imagined as his most important work, however, would ultimately remain unfinished, quietly abandoned in the face of religious opposition, one critical painting short of completion. Truncation dramatically altered possible readings of Triumph, redirecting its narrative energies and generating new meanings in tension with the idea Sargent had proposed. In Painting Religion in Public, Sally Promey tells the story of an artist of international stature and the complex and consuming pictorial program he pursued in Boston. Highly celebrated in its day, with individual panels retaining immense popularity even in the years of discord, this artistic project and its constituent images tell us much about broad cultural and political exchanges concerning the public representation of religious content in the United States.

Sargent's library decoration attracted the attention of multiple audiences and engaged concurrent debates about class, race, art, and religion. Representatives of various religious and cultural backgrounds hailed portions of the cycle as indicative of the strength of their own positions, and reproductions of the images appeared in everything from books and encyclopedias to stained glass and public pageantry. Promey analyzes the conception and production of the cycle, persuasively demonstrating that Triumph of Religion, far from promoting a narrowly sectarian version of religious practice, represented instead Sargent's public recommendation of the privacy of modern belief. The artist recast contemporary religion as spirituality, she argues, linking it not with institutions and dogma but with personal subjectivity. For Sargent, this ideal was a sign of Western, especially American, progress. Carefully reconstructing patterns of reception in an increasingly diverse religious climate, and exploring the extent and character of Sargent's personal and artistic investment, Promey boldly illuminates the work Sargent hoped to make his masterpiece. At the same time, she enriches understanding of religious images in public places and popular imagination.

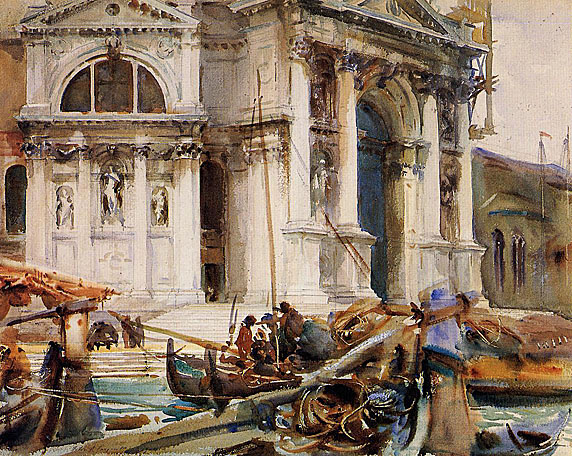

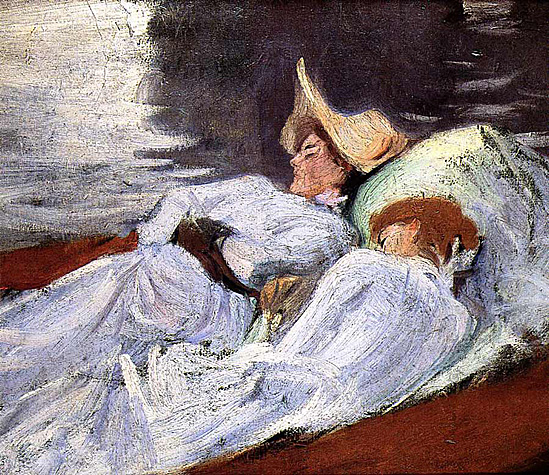

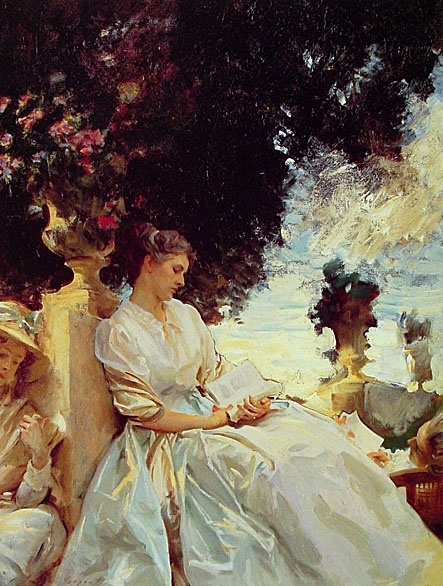

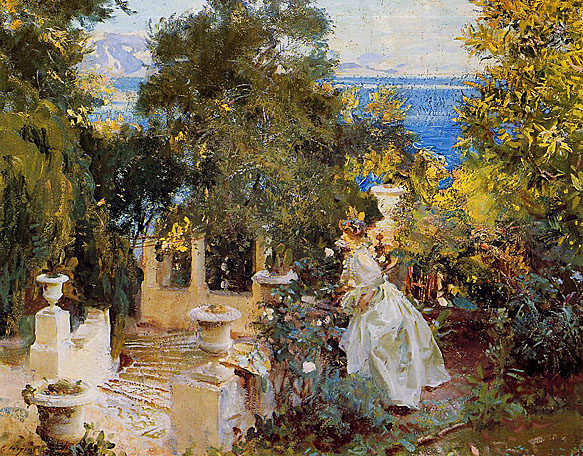

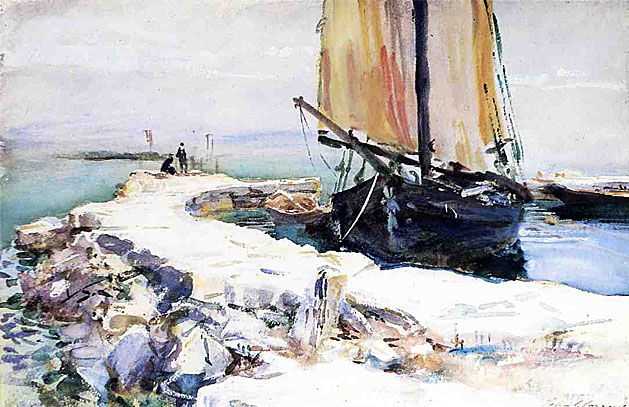

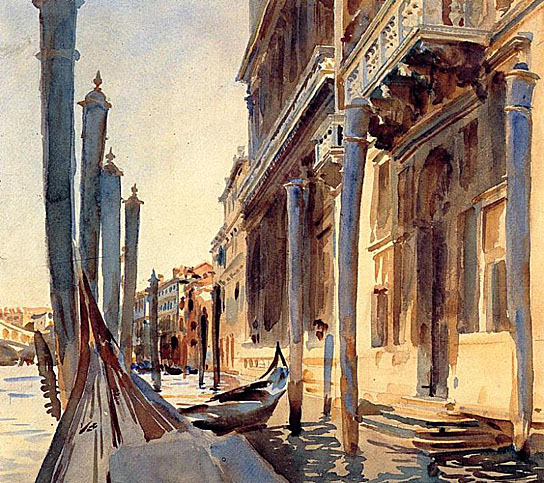

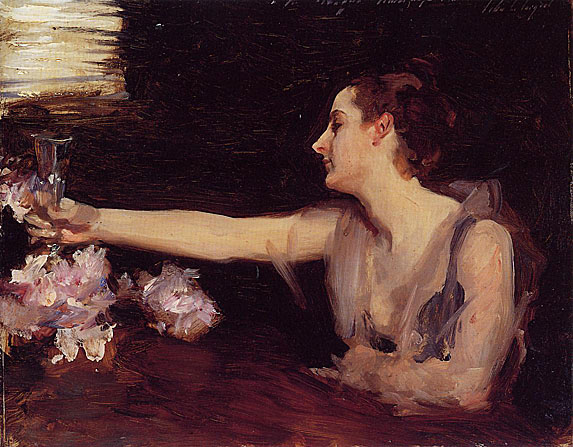

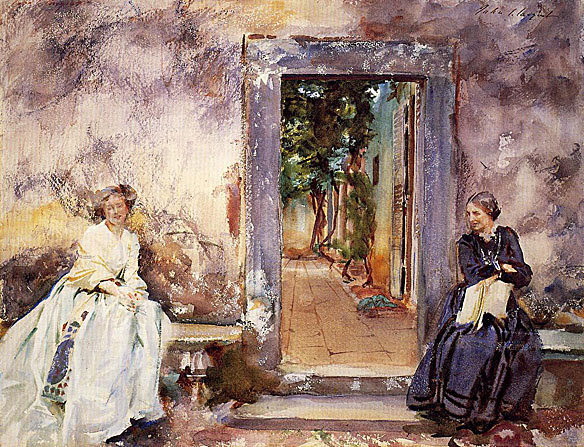

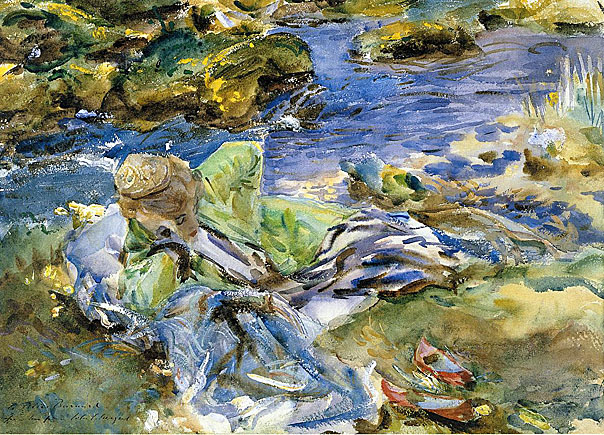

It is in some of his late works where one senses Sargent painting most purely for himself. His watercolors, often of landscapes documenting his travels (Santa Maria della Salute, 1904, Brooklyn Museum of Art), were executed with a joyful fluidness. In watercolors and oils he portrayed his friends and family dressed in Orientalist costume, relaxing in brightly lit landscapes that allowed for a more vivid palette and experimental handling than did his commissions (The Chess Game, 1906).

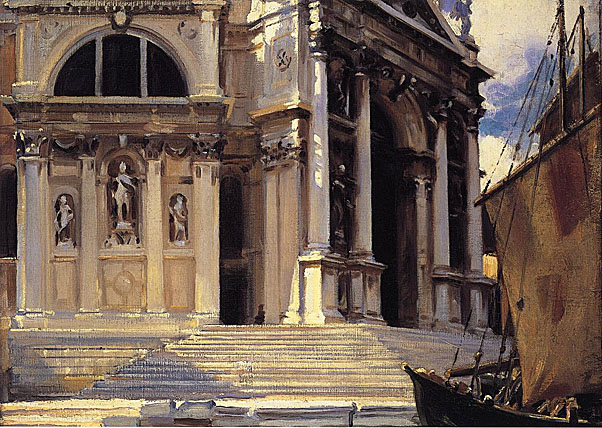

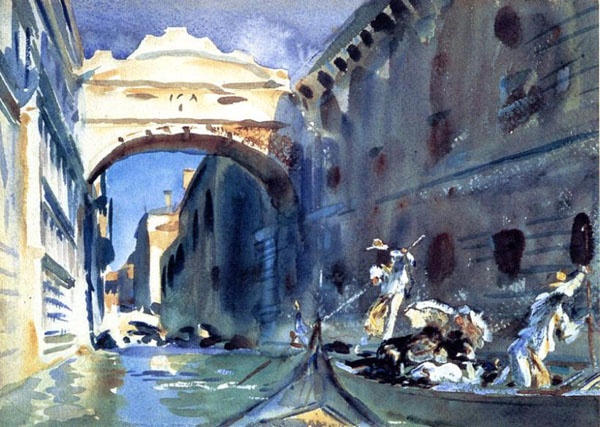

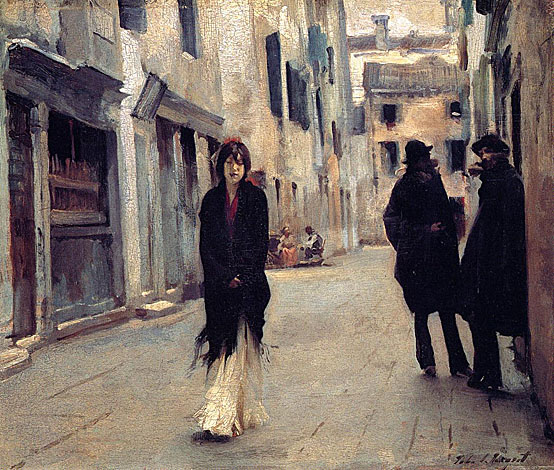

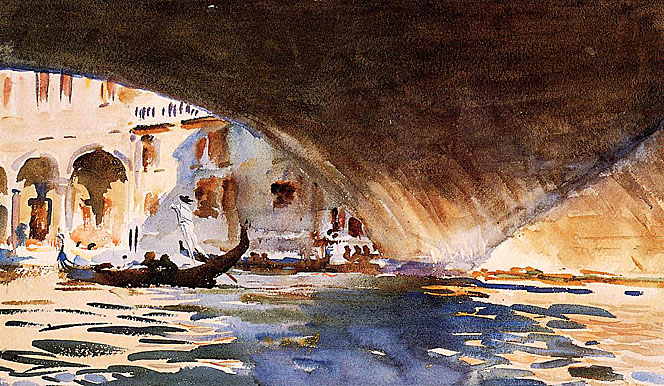

He characterized his paintings in Venice as "snapshots" and wanted very much to capture the feel of the place from an "every-man's" point of view and not necessarily from the typical tourist vantage.

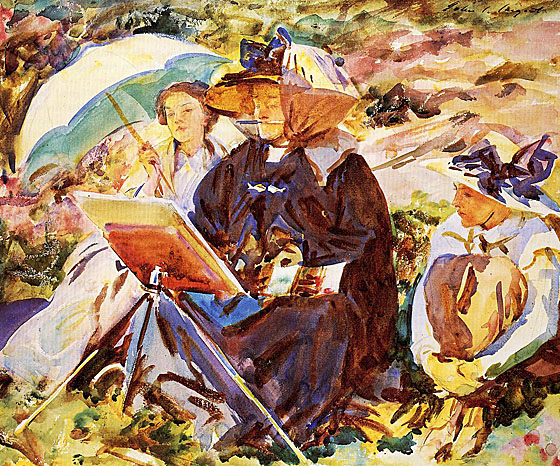

In the summer of 1907 Sargent takes a trip to Purtud which is a little town in the Val d'Aosta on the Italian-Swiss border and there he paints his nieces and friends.

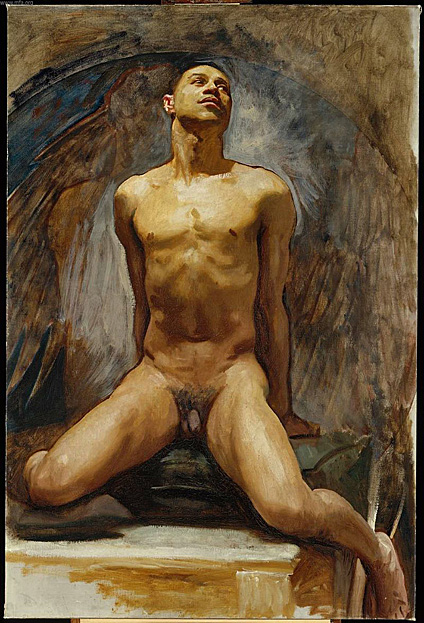

Just like his formal commissioned portraits were he often picked out the dresses for the women he painted, he often packed away in preparation for these long trips, exotic shawls and clothes to have his friends and family wear when he painted them. The Chess Game was such an occasion and here we see Nicola d'Inverno, Sargent's personal valet, along with probably one of his nieces. D'Inverno first started posing for JSS in 1891 for the Boston Library murals.

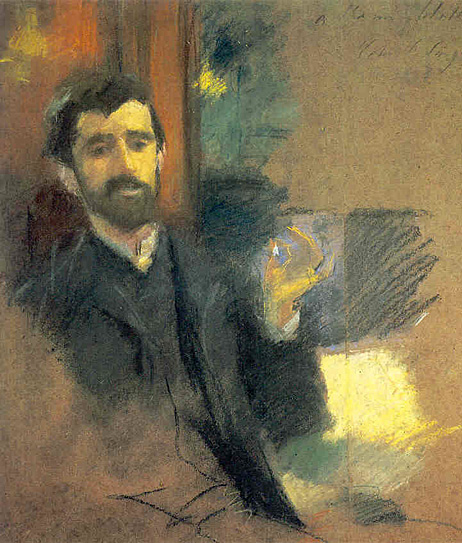

Among the artists with whom Sargent associated were Dennis Miller Bunker, Carroll Beckwith, Edwin Austin Abbey (who also worked on the Boston Public Library murals), Francis David Millet, Wilfrid de Glehn, Jane Emmet de Glehn and Claude Monet, whom Sargent painted. Sargent developed a life-long friendship with fellow painter Paul César Helleu, whom he met in Paris in 1878 when Sargent was 22 and Helleu was 18. Sargent painted both Helleu and his wife Alice on several occasions, most memorably in the impressionistic Paul Helleu Sketching with his Wife, 1889. His supporters included Henry James, Isabella Stewart Gardner (who commissioned and purchased works from Sargent, and sought his advice on other acquisitions), and Edward VII, whose recommendation for knighthood the artist declined.

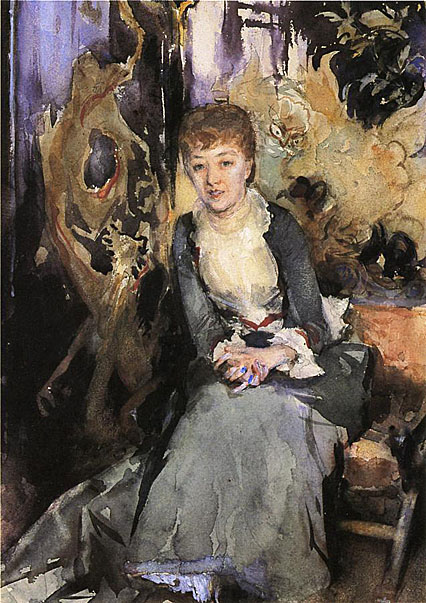

Paul César Helleu (French, 1859-1927) met Alice Louise Guérin in Paris in 1884 and they married two years later. Alice became Paul's favorite model. Over the years he painted her in oils, pastels, and lithographs. When they visited Sargent she was nineteen years old and he thirty.

Paul was one of Sargent's closest friends. They had met in Paris in 1878 when Paul was 18 years old and Sargent 22. Sargent was becoming known to the public and getting commissions for work. Helleu on the other hand was at very low ebb in his life. The story goes that Paul Helleu was terribly despondent, financially strapped with hardly any money to even eat. He was at the edge of the precipice of having to leave his studies in art for lack of funds. He had not sold anything and was deeply discouraged.

Sargent, having heard this, went and visited Helleu at his gallery and without mentioning Paul's financial straits, picked out one of his paintings, and praised its merits. Paul was so flattered the successful Sargent would think so kindly of his work that he offered to give it to him.

Sargent responded, "I shall gladly accept, Helleu, but not as a gift. I sell my own pictures, and I know what they cost me by the time they are out of my hand. I should never enjoy this pastel if I hadn't paid you a fair and honest price for it." And he paid him a thousand-franc note. Paul had never even seen a thousand-franc note before.

Helleu never forgot that and they remained fast and dear friends. In Sargent's own troubled moments, as when the loss of his father, it was Paul and his wife, among others, who visited and stayed a while in England. And it was the two of them along with other artists that went to the Netherlands to in 1883 to study Frans Hals.

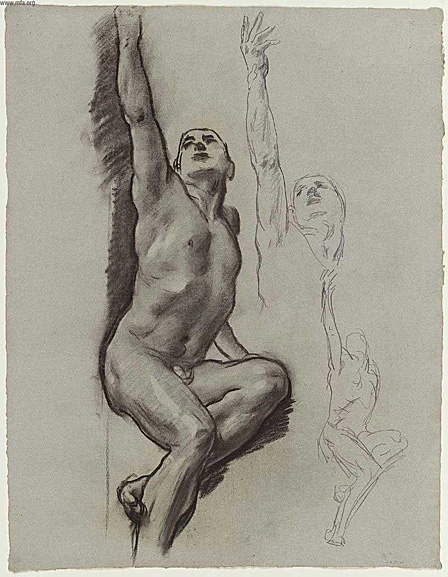

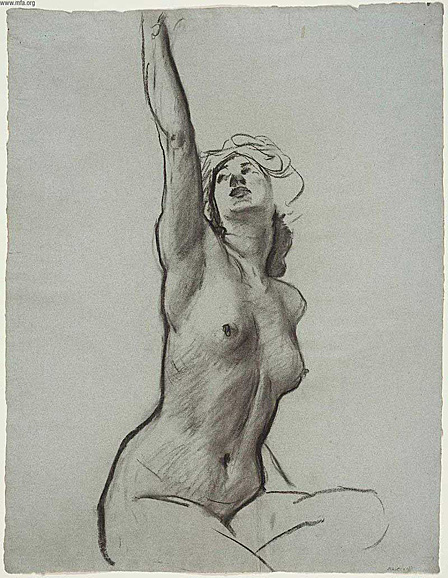

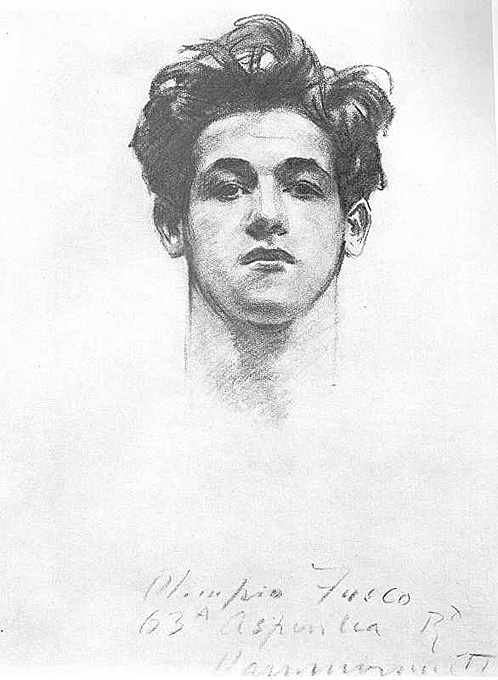

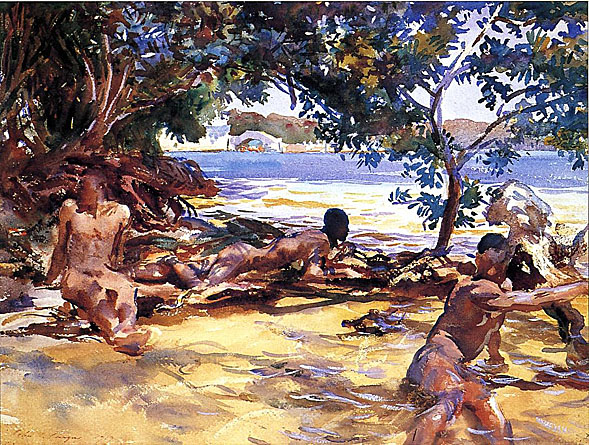

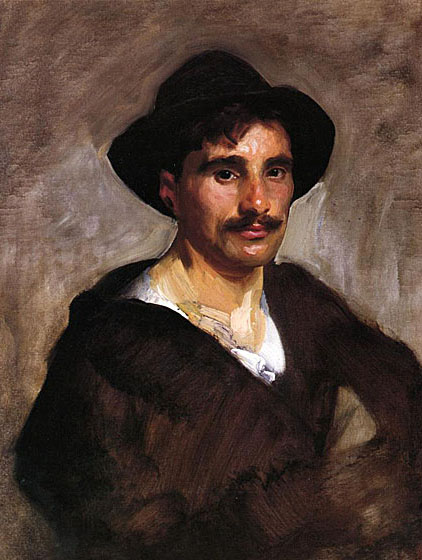

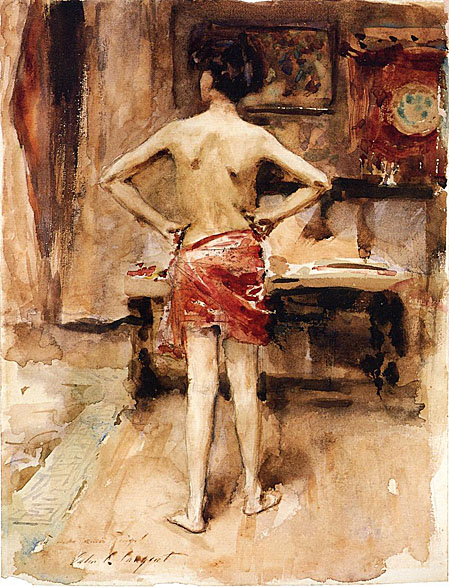

Sargent was extremely private regarding his personal life, although the painter Jacques-Émile Blanche, who was one of his early sitters, said after his death that Sargent's sex life "was notorious in Paris, and in Venice, positively scandalous. He was a frenzied bugger." The truth of this may never be established. Some scholars have suggested that Sargent was homosexual. He had personal associations with Prince Edmond de Polignac and Count Robert de Montesquiou. His male nudes reveal complex and well-considered artistic sensibilities about the male physique and male sensuality; this can be particularly observed in his portrait of Thomas E. McKeller, but also in Tommies Bathing, nude sketches for Hell and Judgement, and his portraits of young men, like Bartholomy Maganosco and Head of Olimpio Fusco. However, there were many friendships with women, as well, and a similar sensualism informs his female portrait and figure studies (notably Egyptian Girl, 1891). The likelihood of an affair with Louise Burkhardt, the model for Lady with the Rose, is accepted by Sargent scholars.

In a time when the art world focused, in turn, on Impressionism, Fauvism, and Cubism, Sargent practiced his own form of Realism, which brilliantly referenced Velázquez, Van Dyck, and Gainsborough. His seemingly effortless facility for paraphrasing the masters in a contemporary fashion led to a stream of commissioned portraits of remarkable virtuosity (Arsène Vigeant, 1885, Musées de Metz ; Mr. and Mrs. Isaac Newton Phelps-Stokes, 1897, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) and earned Sargent the moniker, "the Van Dyck of our times." Still, during his life his work engendered critical responses from some of his colleagues: Camille Pissarro wrote "he is not an enthusiast but rather an adroit performer", and Walter Sickert published a satirical turn under the heading "Sargentolatry". By the time of his death he was dismissed as an anachronism, a relic of the Gilded Age and out of step with the artistic sentiments of post-World War I Europe. Foremost of Sargent's detractors was the influential English art Critic Roger Fry, of the Bloomsbury Group, who at the 1926 Sargent retrospective in London dismissed Sargent's work as lacking aesthetic quality.

Despite a long period of critical disfavor, Sargent's popularity has increased steadily since the 1960s, and Sargent has been the subject of recent large-scale exhibitions in major museums, including a retrospective exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1986, and a 1999 "blockbuster" travelling show that exhibited at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the National Gallery of Art Washington, and the National Gallery, London.

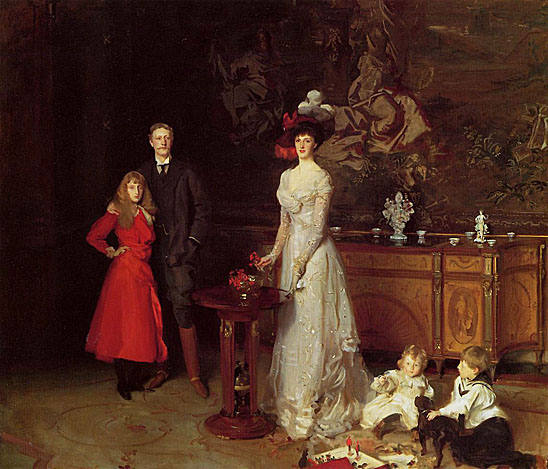

It has been suggested that the exotic qualities inherent in his work appealed to the sympathies of the Jewish clients whom he painted from the 1890s on. Nowhere is this more apparent than in his portrait Almina, Daughter of Asher Wertheimer (1908), in which the subject is seen wearing a Persian costume, a pearl encrusted turban, and strumming an Indian Sarod, accoutrements all meant to convey sensuality and mystery. If Sargent used this portrait to explore issues of sexuality and identity, it seems to have met with the satisfaction of the subject's father, Asher Wertheimer, a wealthy Jewish art dealer living in London, who commissioned from Sargent a series of a dozen portraits of his family, the artist's largest commission from a single patron. The paintings reveal a pleasant familiarity between the artist and his subjects. Wertheimer bequeathed most of the paintings to the National Gallery.

In 1898, John would embark on his largest private portrait commission that would, when it was finally finished, span ten years and include twelve oil portraits. This suite of paintings would be unmatched by anything outside his mural work.

It started simple enough. Asher Wertheimer had hired John to paint his wife and himself in two pendent portraits which would celebrate their silver wedding anniversary. As so many had before them, the Wertheimer fell in love with the charming artist. Unlike others though, they were utterly insatiable for his work in depicting their family. With one portrait done, Asher and his wife would want another, and then another, and then yet another after that. John would joke that he felt he was in a state of "chronic Wertheimerism." The bond between them would become so strong that the family held a chair at their dinner table in reserve for whenever he wanted to drop in -- and he would.

In October of 1999, The Jewish Museum of New York put together the entire group of twelve portraits for the first time since they hung privately in the family's home.

John Singer Sargent is interred in Brookwood Cemetery near Woking, Surrey.

As one faces the markers: to the right is John Singer Sargent's gravestone sharing with his sister Emily. To the left, and of the same style, is the stone of his other sister Violet with her husband, Louis Francis Ormond.

LABORARE EST ORARE

JOHN S. SARGENT R.A.

BORN IN FLORENCE

JAN 12th 1856

DIED IN LONDON

APRIL 15th 1925

ALSO HIS SISTER

EMILY SARGENT

BORN JAN 29TH 1857

DIED MAY 22ND 1936

At the base of the stone reads:

HE GIVETH HIS BELOVED SLEEP

Also at the grave is another stone identical in style that marks the grave of his other sister, Violet, and her husband, Louis Francis Ormond.

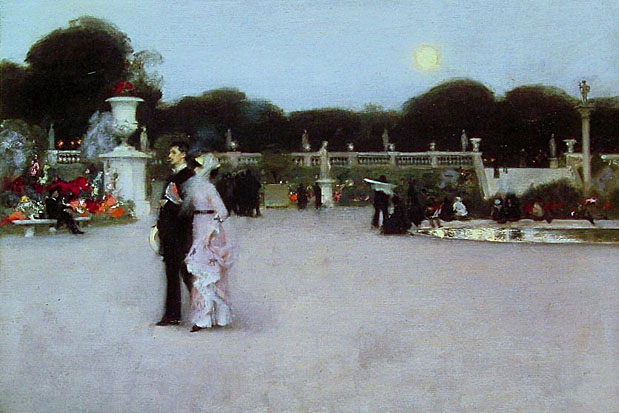

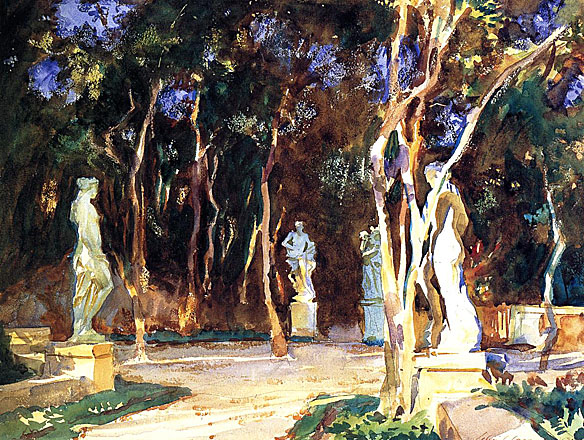

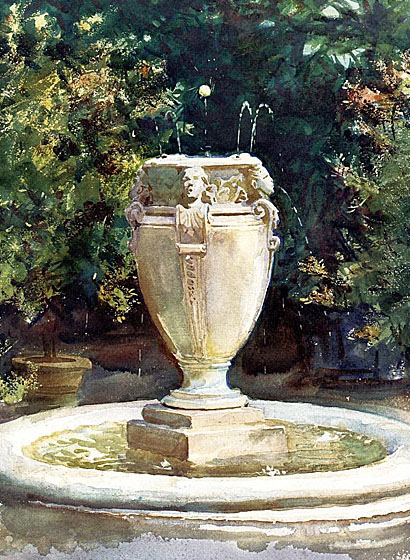

The gardens are part formal garden with terraces and gravel paths, part "English garden" of lawns, and part amusement centre for gardenless Parisians. The gardens were (and still are) one of the city's most popular public spaces. Dotted around is a veritable gallery of French sculpture, from a looming Cyclops on the 1624 Fontaine de Médicis, wild animals, to queens of France, and one of Sainte-Gèneviève -- the patron saint of Paris. There are orchards, and flowering trees.

The proximity of the gardens is very near the Latin Quarter were Sargent lived when he was studying in Paris and so he probably spent a great deal of time here

. It's interesting to keep in mind that when Sargent came to Paris to study in 1874, it was only three years after The Paris Commune (a brief civil war/revolt) that killed over twenty thousand Parisians and had left the Palais du Luxembourg badly burned. In its wake the Third Republic was formed and was rebuilding the damanged parts of the city. So it was in this light that Carolus-Duran was commissioned to paint "The triumph of Maria de Medici" for the remodeled Palace in 1877 which Sargent took part -- though the painting wouldn't end up there.

What seems most unique about Sargent is that his paintings appear so effortless. He doesn't hide every brushstroke, as some painters do. He just daubs it on with great confidence, and it ends up looking like the most natural thing in the world.

In fact it's well worth enlarging this painting to its actual size (see option #3 above), just so that you can appreciate the sheer size of the brushstrokes - for example, the horizontal section of wall immediately above the sofa.

Three days of arid Paris contain less delights than one Cancalaise hour.

When Sargent visited there in 1877, many of the men were away -- as they would often be through the nineteenth century -- sailing far into the ocean bound for the rich fisheries of Newfoundland, gambling big on a catch that might pay handsomely. Fathers, sons, brothers, sometimes many of the eligible men in a household might be gone for as long as six months from spring till fall.

In their absence, and left to their own resources, the women and children could not live on promises of a Newfoundland catch alone. What they did have, however, were conditions along a coastline that were so unusual, that as far back as the Romans, the area had been harvested for oysters.

When Sargent visited there in 1877, many of the men were away -- as they would often be through the nineteenth century -- sailing far into the ocean bound for the rich fisheries of Newfoundland, gambling big on a catch that might pay handsomely. Fathers, sons, brothers, sometimes many of the eligible men in a household might be gone for as long as six months from spring till fall.

In their absence, and left to their own resources, the women and children could not live on promises of a Newfoundland catch alone. What they did have, however, were conditions along a coastline that were so unusual, that as far back as the Romans, the area had been harvested for oysters.

With this representation of a North African woman infusing her robes and senses with the musky perfume of ambergris (a resinous substance extracted from whales and considered an aphrodisiac as well as a guard against evil spirits), Sargent entered into the list of artists who, from the 1860s to the turn of the century, popularized exotic images of Near-Eastern culture to Western audiences. However, unlike artists such as Jean-Léon Gérôme (French, 1824-1904), who relied upon heightened realism to lend veracity to the narrative of their paintings, Sargent's preoccupation in Fumée d'ambre gris was not with the subject matter.

In July of 1880 he wrote to a friend about a "little picture I perpetrated in Tangier....the only interest in the thing was the color."

Indeed, the painting is a nuanced study of creams and whites wherein Sargent subordinates the subject matter-through a tour-de-force presentation-to the act of painting itself. In this favoring of style over subject, Fumée d'ambre gris is an expression of the artist's alignment with the art-for-art's-sake movement that prevailed in the last quarter of the nineteenth century.

The color sense and painterly handling exhibited in Fumée d'ambre gris generated enthusiastic praise from critics on both sides of the Atlantic. Even the canny sophisticate, Henry James, was not impervious to the painting's seductive charm. Under the spell of its mesmerizing effect, the famous author expressed the essence of the mystery that still beguiles the viewer in our own day: "I know not who this stately Mohammedan may be, nor in what mysterious domestic or religious rite she may be engaged; but in her muffled contemplation and her pearl-colored robes, under her plastered arcade, which shines in the Eastern light, she is beautiful and memorable...."

The bridge was built around 1600, significantly after the Council of Ten and the advent of the secrete state police, but it has always been associated, especially today, with a symbol of that period -- though be it belated.

.jpg)

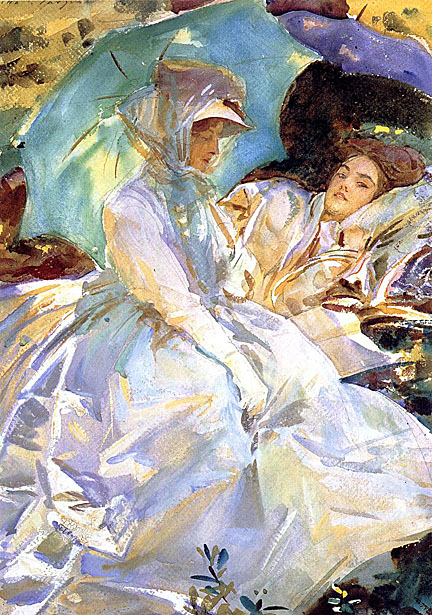

Group with Parasols (A Siesta) is a beautiful example of the 'world of dreamy reverie' and is evocative of the newfound intimacy in Sargent's work. The painting captures the Harrison brothers Peter and Ginx, Dos Palmer and Lillian Mellor enjoying a mid-afternoon slumber amid the grassy hills of the region. The closeness of the figures, the fluid intertwining of limbs and the juxtaposition of male and female represents an unusual familiarity between the sexes that would have challenged Victorian convention. Mr. Ormond writes, "There is a deliberate contrast between the two sides of the composition, softly rounded contours and delicate materials for the women, angular knees, elbows and creased trousers for the men. At the same time the rhythm of the curving bodies, arms, and heads unites the figures in a tightly interlocking group". Ilene Susan Fort notes that the Alpine Pictures "display contradictions in time, gender orientation, and degree of sexuality that can be understood only within the social context of the age. Sargent was a personality not only aesthetically progressive but also socially bohemian; his opinions and taste were sometimes at odds with, and too modern for, the strictest Victorian society".

The intimacy of the subjects is further emphasized by the essentially closed composition in which the surrounding landscape is closely cropped and bordered. Ms. Fort observes, "Sargent placed his models in an intimate and virtually anonymous outdoor environment, thereby creating the notion of a 'landscape interior.' He repeatedly depicted a small forest glade that marked the boundaries of his personal domain. By cropping and deleting horizons, Sargent made the landscape appear to be pushed forward, parallel to the picture plane. His models exist in this limited space with no suggestion of a world beyond the painted scene"

I have found very little on the model Gigia Viani but to see her, to see her in the settings that Sargent has placed her -- the everyday life of the everyday person makes me want to know so much more about her. A beauty not unlike Rosina Ferrara from Capri, begs the question of what is the story behind this remarkable face?

The cup is half full, Alan. I have little doubt that what we see here is Venice, not in how the tourist might see it, but in how the locals see it in everyday life in the year 1882.

This is street-life on a chilly day in the fall or winter with men in top coats and the woman in a warm wrap, on an old narrow street with locals who talk to their neighbors.

In 1883, Sargent sent A Street in Venice to the Societe Internationale des Peintres et Sculpteurs, Rue de Seze, Paris. One critic called Sargent's work "banal and worn-out".

M. Sargent leads us into obscure squares and dark streets where only a single ray of light falls. The women of his Venice, with their messy hair and ragged clothes, are no descendents of Titian's beauties. Why go to Italy if it is only to gather impressions like these.

Arthur Baigneres, critic for the Gazette des beaux-arts: Abbeville Press, New York, 1982.

This is the real Venice on a cool autumn or winter day. And knowing Sargent, though it might not be pretty at first impression, it is probably a very accurate depiction of local life.

In Charles Merril Mount biography of Sargent, he speculates that Carmencita may have been a possible lover, but I find this unlikely from what I've learned. What is probably more accurate is that their public flirtations would be just in line with Carmencita's personality and their friendship and not any real indication of a serious romance.

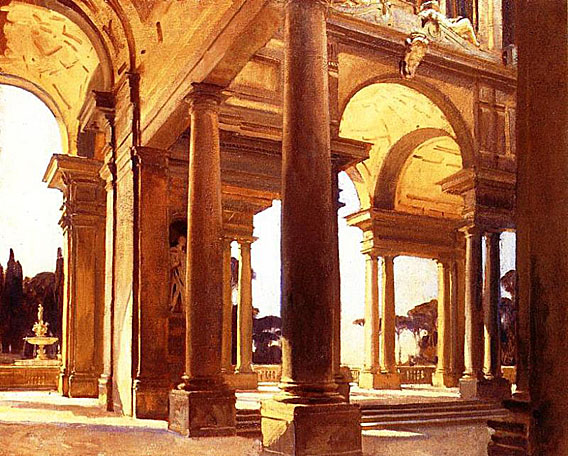

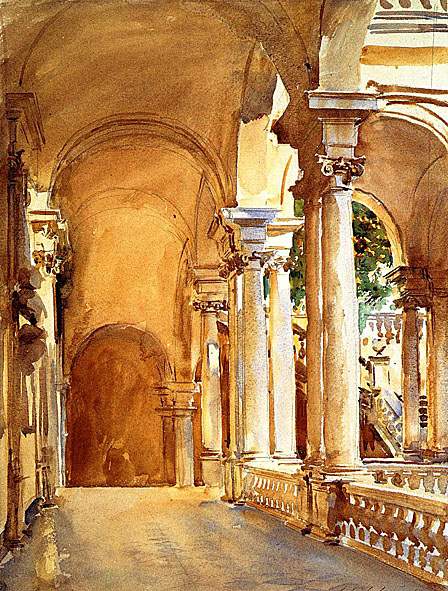

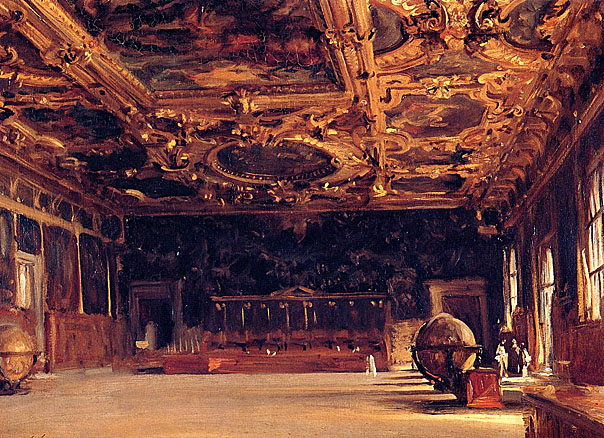

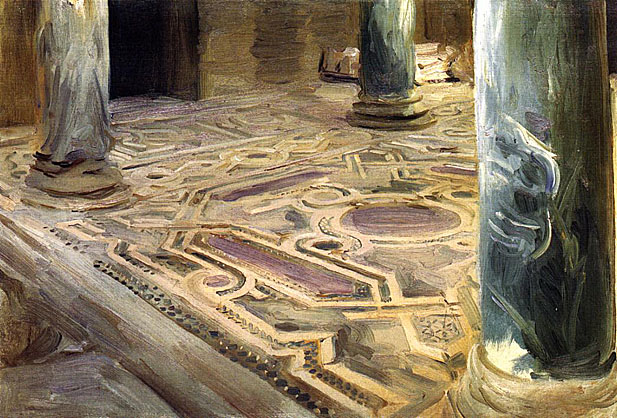

Sargent is trying to capture not the entire structure but the wondrously poetic sense of this beautiful space.

In 1577, the room was destroyed by fire but rebuilt with even more luxury then before, including a gilded ceiling which we see in Sargent's painting -- In fact the ceiling is a prominent feature in the composition. The room was decorated by the greatest artists of the time such as Palma, Tintoretto, Veronese, and Bassano.

Sargent has set his easel to face east and we can see, somewhat, Tintoretto's Paradise along the far wall -a massive painting measuring 22 x 7 meters. In fact this is the largest surviving painting of that time period -- anywhere.

The oval ceiling painting (located center) is by Paolo Veronese called "Triumph of Venice" and proclaimed the greatness of this island nation.

The Cathedral of Tarragona is located in (square) Pl. de la Seu right in front of the Gothic porches and next to the University of Tarragona.

Its most important offer here is one of the most important collection of tapestries (most important in Europe) also has gothic paintings. But there is more, also has a fantastic collection of baroque sculptures and renaissance paintings.

One cannot leave this museum without visiting the cloister with its impressive entrance and an spectacular Arab arch, a unique piece in the whole Catalonia. This building is a mix of romantic and baroque, it is a place one must take some time to visit.

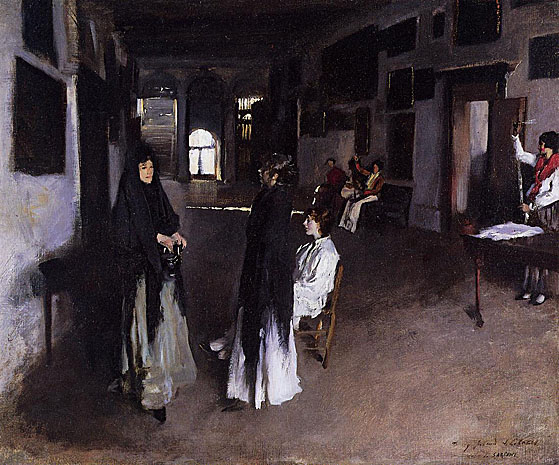

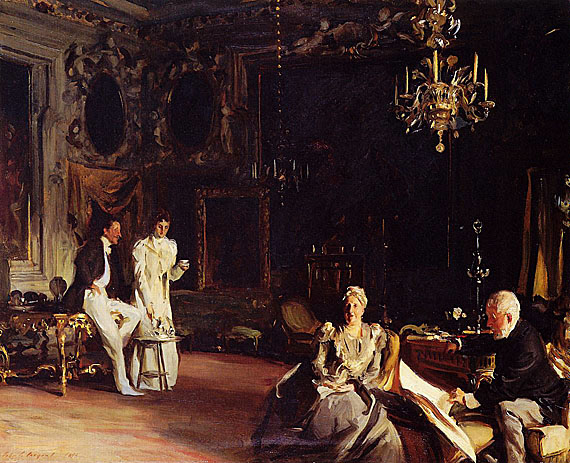

In his Diploma work Sargent depicts the couple, their son Ralph and his wife Lisa in the grand salon of the Palazzo. The dark interior and use of dashingly bold highlights relates to the work of DiegoVelázquez (1599-1660), which Sargent greatly admired. Comparing An Interior in Venice with seventeenth-century Dutch interiors, Whistler dismissed Sergeant's 'little picture' as 'smudge everywhere'.

Sargent originally intended this painting as a gift for Mrs Curtis (who he nicknamed 'the Dogaressa') but she declined it as she thought it made her look too old and because she believed that her son was not depicted with appropriate decorum.

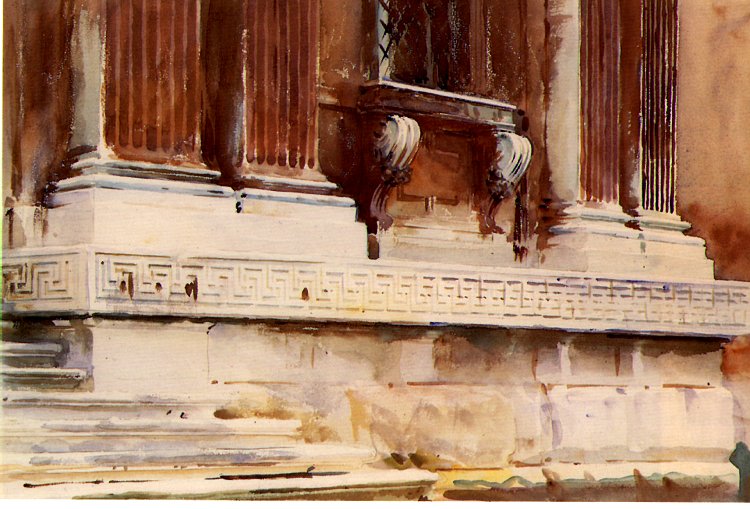

Venice was nearly a second home to Sargent who had known the city from his early youth. In the 1880s, his somber-toned Venetian paintings focused on local life seen through doorways and along the narrow streets far removed from the activity along the canals. After the turn of the century, he began to look closely at the architecture of the city and the effects of light on its spectacular facades and stone surfaces. He visited Venice nearly every year through 1913 and often stayed with his cousins, Mr. and Mrs. Daniel Curtis and their son Ralph, who lived at the Palazzo Barbaro on the Grand Canal.

The subject of this oil is the Venetian church of San Stae, not the Gesuiti as it had first been identified in the artist's studio sale (after his death in 1925). The facade, cut off just above the pediment of the main door, is characteristic of Sargent's Venetian architectural paintings.

One window of the red Scuola dei Battiloro e Tiraoro is seen to the left. Sargent painted only one other oil of the Church of San Stae (private collection) in which he omitted the elaborate architectural detail of the entrance and facade.

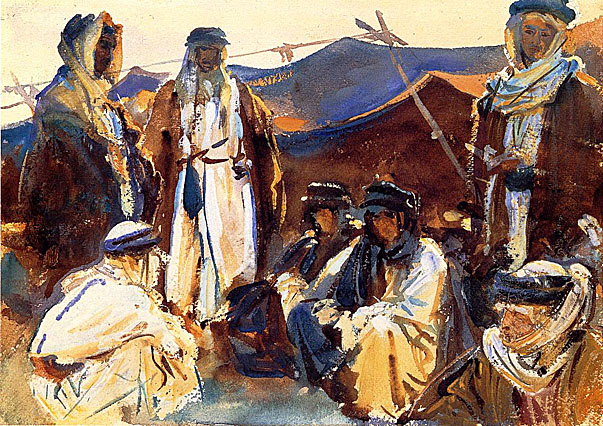

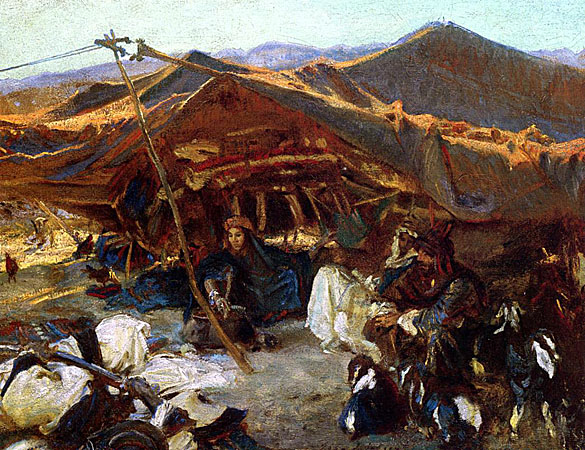

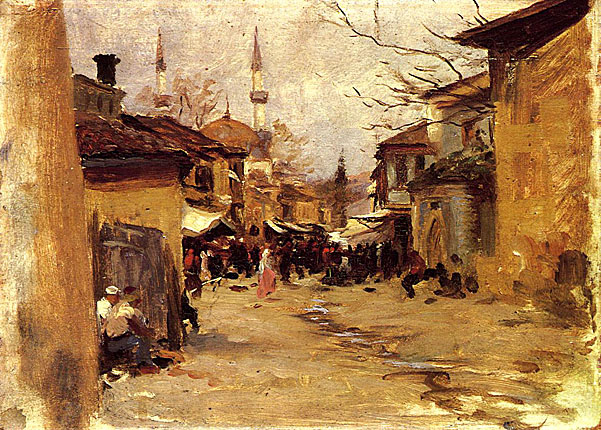

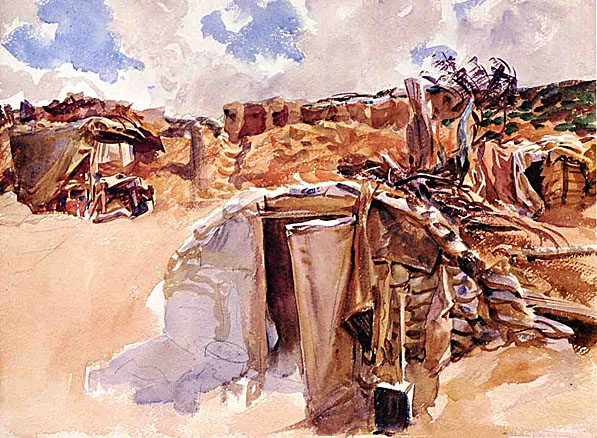

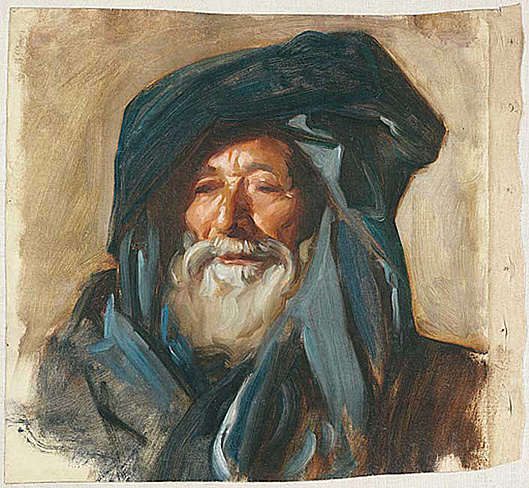

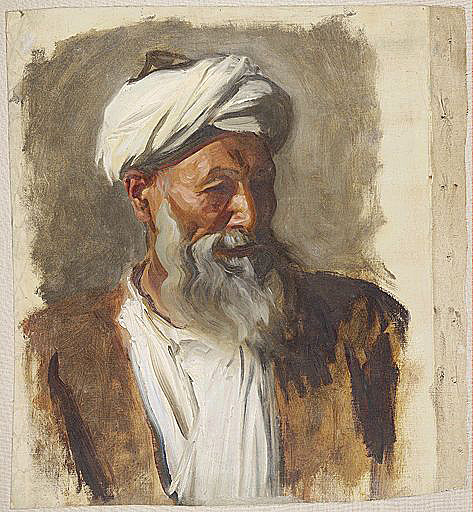

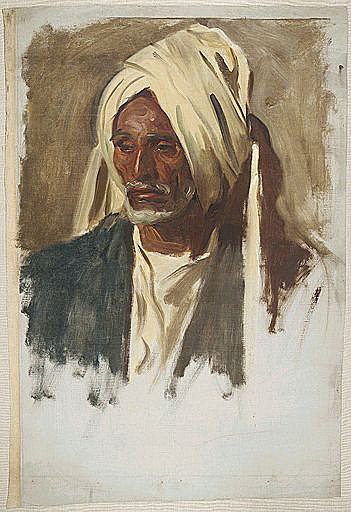

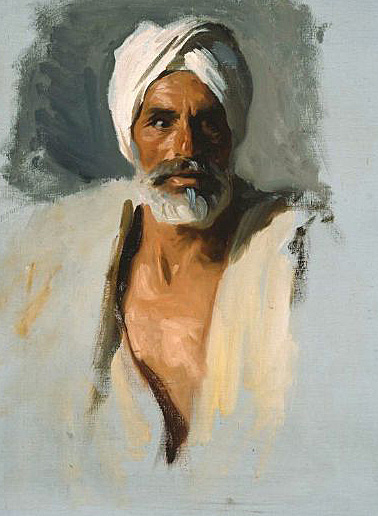

Yet Sargent, despite his phenomenal success as a portrait painter, also produced an astonishing number of sketches and paintings of the Middle East: Egypt, Palestine, today's Syria and Lebanon and the nearby deserts.

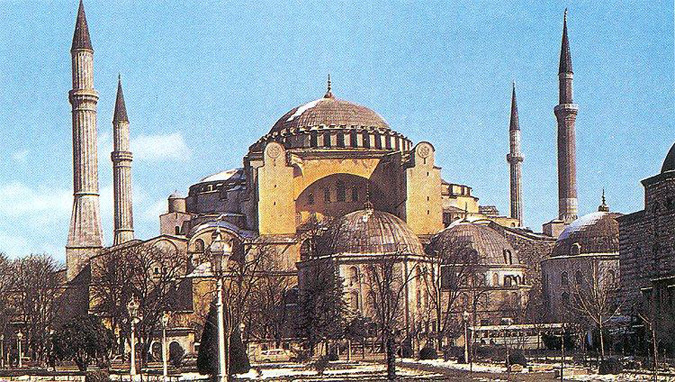

Curiously, that aspect of Sargent's career developed out of his success as a portrait painter. Restless and discontented despite his fame, he began to seek more creative styles and subjects and, in 1890, accepted a commission to paint decorative murals for the Boston Public Library; like many of his contemporaries he saw murals as the highest form of art. It was, in any case, a new artistic challenge, one that engaged his attention for the next 26 years. It also led him to Egypt in 1890, to the Holy Land in 1905 and, eventually, to a series of works that trace the development of western religious thought from paganism through Judaism, to Christianity.

Sargent was commissioned in 1890 to do the murals for the Boston Public Library. Receiving that commission delighted Sargent, and he threw himself into the project with enthusiasm. Immediately upon accepting the commission, he set off for Egypt to study the ancient pharaonic world of temples, tombs and sculpture. During a busy month there, he sketched figures and designs from the monuments in Cairo, Luxor, Philae and Fayyum. These sketches were incorporated later in the library's north-wall mural, actually a huge canvas symbolizing the Israelite captivity in Egypt. In addition, Sargent, during his Egyptian travels, painted landscapes and portraits: Indigo Dyers, Sunset Over Cairo, Water Carriers on the Nile and Temple of Denerah, few of which are, unfortunately, readily available to the public today. Some are unaccounted for, others are privately owned and a few, from the Metropolitan's collection of 11 paintings, are on loan to government agencies. One portrait, for example, Egyptian Women, is currently part of an exhibition of American painting in Moscow.

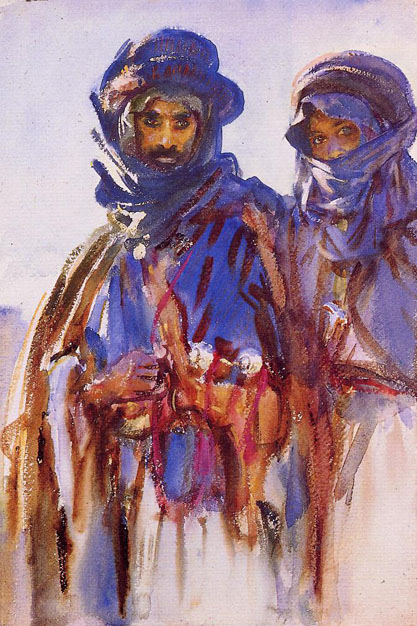

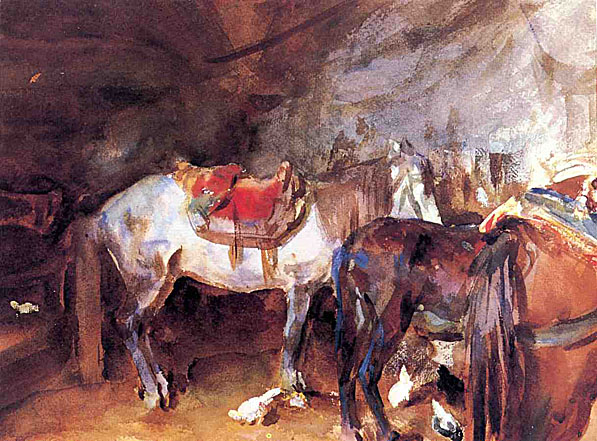

Turning to the desert, he joined a Bedouin tribe, travelled and lived with the tribe and produced a series of watercolors that record in a bold, vibrant and fluid style vignettes of desert life: meals over the open fire, black tents with mysterious interiors, fiery desert sunsets, handsome Arabian horses and barren parched lands. By juxtaposing large patches of colored wash with bold colors and combining them with selected details, often abstracted at the edges of the painting, Sargent offered convincing scenes executed with consummate skill and bravura. He captured, moreover, the immutable quality of desert life and the personal strength that develops from coping with a harsh environment. The striking portrait Bedouins is a good example. A vivid watercolor of two desert men dressed in thobes and wearing bandoliers, this painting, like all his desert watercolors, explores the optical transformation of the actual colors into very intense colors under the angled desert sun. He paints, for example, the normally somber, monochromatic thobes in the brightest cobalt blue - a form of impressionism - but renders the faces in detail to achieve, finally, a realistic portrait with poetic overtones.

Another painting from this trip is the Hills of Galilee, with distant hills in orange and lavender, recently tilled farmland in a bright, burnt red and a misty farmer and his ox, at once impressionistic and realistic. And a third is the Arab Stable, a unique work which led Sargent, in a letter to Mrs. Gardner, to explain the unrealistic touch of cobalt blue on the hindquarters of a horse: "They ought to have blue ribands plaited into their tails and manes, like Herod's horses in Flaubert's beautiful Herodiade." Since there are areas in the painting left undefined which disintegrate into abstraction, Sargent called this "a watercolor sketch."

To those paintings Sargent also added hundreds of small sketches, charming snapshot pieces sometimes done with quick minimal lines, other times in surprising detail; the sketch called Syrian Arab is a good example. He also, enroute to London after he learned of his mother's death, added two charming watercolors: Melon Boats and In a Levantine Port. Altogether these Middle Eastern works display Sargent's finest moments and talents.

In retrospect, Sargent's search for "new fuel" for his murals was unsuccessful. As, eventually, were the murals themselves. Sargent himself saw those murals - and others commissioned for the Boston Museum of Fine Arts and the Widener Library at Harvard University - as the culmination of his training and background. But after his death, public interest in murals waned as tastes changed and more impressionistic art forms came into vogue. On the other hand, the second Middle East trip also marked, and possibly brought about, a turning point in Sargent's career. Not long after his return, he began to devote most of his time, when not working on the murals, to freer, more impressionist watercolors. And in 1908 he sold 83 watercolors to the Brooklyn Museum, the largest body of his watercolors ever sold until then. He still did an occasional portrait, such as those of John D. Rockefeller and President Wilson, but generally, in his last years, he tended to paint only close friends or, to keep his fashionable clientele happy, dash off a quick charcoal sketch. And when he died, in 1925, his studio was filled not only with portraits, but with watercolors, many of them of the Middle East and its endlessly fascinating people.

By Joy Wilson

Rose-Marie Ormond

Widow of Robert André-Michel

killed at Saint-Gervais, on Good Friday, 1918

by German bombardment

"On March 29, 1918, Sargent's niece Rose Marie, daughter of Mrs. (Violet) Ormond and widow of Robert Andre' Michel who had fallen while fighting on October 13, 1914 was killed in Paris. She was attending a Good Friday service in the church of St. Gervais when a German shell struck the building, killing seventy people, among whom was Madame Michel. She was a person of singular loveliness and charm, and had figured in Sargent's works, notably in Chashmere, The Pink Dress and the Brook .. .. She had traveled with him on some of his sketching tours, and her youth and high spirits and the beauty of her character had won his devotion. Her death made a deep impression on him."

By 1918 Rose-Marie Ormond Michel would have been approximately 28 years old. John, of course, had never married and was childless. He must have been drawn to her like a doting father for he was very close to all his family and I think Rose-Marie was his favorite model. The loss he felt must have been no less than the loss of a parent.

The war has hit home now -- twice. John's sister Violet won't leave Britain because her boys are enlisting, and Emily won't leave her sister Violet. In the tragic aftermath and with Sargent still in the States, he feels the growing isolated from his sisters.

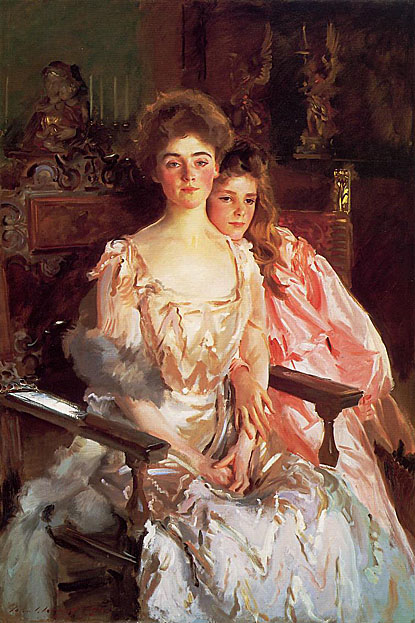

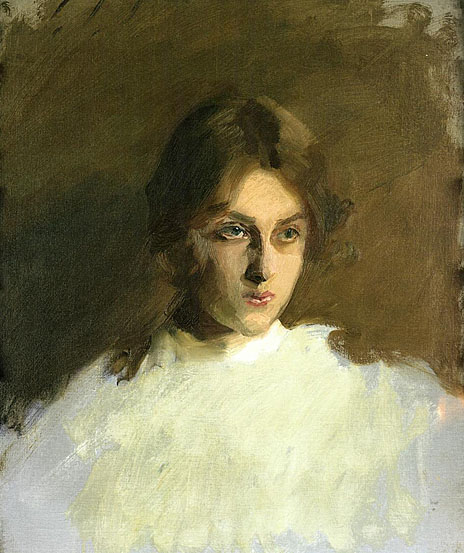

This portrait was unique -- not entirely -- but among many. Sargent had asked Alice's parents for permission to paint her, he wasn't asked. John had been executing a commission for her father, the lawyer and newspaper publisher Elliott Fitch Shepard when they met. She was only thirteen at the time and was recovering from a riding accident. Her mother, whom was the subject of the original commission agreed on the condition that Sargent wouldn't tire her out with long sittings.

As he had done in some of his other works, the face here is thinly and delicately painted to reveal her stunning countenance with her blouse and jacket in a slightly more bravura style.

She attended the Radcliffe College of Harvard University. She was an honorary member of the Phi Beta Kappa society. She also received an honorary doctorate in Literary Science from Syracuse University "as special recognition of the field of study that you have made your own, the field of the international auxiliary language." She was Vice President of the World Service Council of the YWCA USA.

From her youth, Morris was troubled by ill health and was forced to spend much of her time on a sofa. Despite her illness, she initiated what was probably the most extensive linguistic research undertaken to date. During her stay at a clinic, Morris found a brochure on the artificial language Esperanto. She became interested in the idea of a neutral auxiliary language that could facilitate communication among diverse groups of people. Frederick Gardner Cottrell, later a well-known American chemist, persuaded Morris to tackle the problem of an auxiliary language, but objectively and scientifically.

In 1924, Morris and her husband founded the International Auxiliary Language Association (IALA). Morris had studied Esperanto, so the neutrality of IALA was often a dilemma for her. Nevertheless, she succeeded in remaining neutral. In 1945, she co-authored with Mary C. Bray the General Report of IALA. Morris was actively involved in the association - and remained its honorary Secretary - for the rest of her life.

Morris died in 1950 in New York. She was 75. About six months later, the Interlingua-English Dictionary was published, presenting to the world her life's work, Interlingua.

In 1999, Julia S. Falk of Michigan State University published the book Women, Language and Linguistics - Three American Stories from the First Half of the Twentieth Century. The women portrayed were Gladys Amanda Reichard, E. Adelaide Hahn, and Alice Vanderbilt Morris.

His whole life, Sargent would have a love affair with Spanish music and its culture. He would say that it is the most beautiful music and that all great music had, in one form or another, some roots to Spanish music. Even his original thoughts for the Boston Public Library murals were to be on Spanish literature.

Unlike most of his paintings, this one was not painted on site but reconstructed in his Paris studio from memories and sketches that he did during his Spanish trip of the fall and winter of 1879/80.

In May of 1882 he exhibits El Jaleo at the Paris Solan with resounding applause. Here was man capable of much more than just portrait paintings with a passion and mystery that the public liked. Sargent is feeling his oats and loving it.

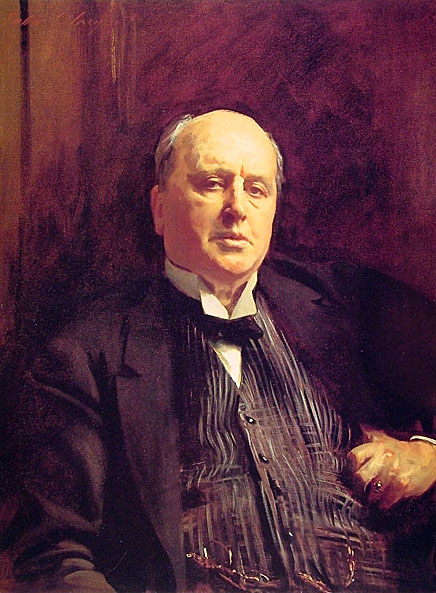

James lived for a period in Paris but hated it and finally found his home in London and was a big supporter of JSS coming to England after the Madame X scandal.

During his period at Broadway with Sargent in 1885, he was writing the Bostonians and The Princess (1884-1886). His reputation by then had already been well founded along with his age, being one of the oldest, made him by far the dean of this small colony of artists gathered there.

It was James, who was one of the first to recognize Sargent, and praised him to American audiences. When Sargent eventually ventured to the United States in 1887 for his first portrait commissions on this side of the ocean, Henry James introduced Americans to this American painter in an unheard of (for such a young artist) nine page spread extolling his talents for Harper's New Monthly Magazine. The clout that James had with Harper's and the generous appraisal from his friend went a long way at promoting Sargent's career in the eyes of the public -- John would never forget that.

When Sargent did this portrait of James, it was for his seventieth birthday (Sargent was 57). John had tried to paint James earlier in their friendship but both had felt the painting had been a failure.

While the portrait is on display the following year (1914) at the Royal Academy, the painting was attacked by a women's suffragette in the attempt to bring notice to her cause. Sargent would later fix it.

Higginson was born in New York City, the second child of George and Mary (Cabot Lee) Higginson, and a distant cousin of Thomas Wentworth Higginson. When he was four years old his family moved to Boston, making him by birth part of the elite class of Bostonians known as the "Boston Brahmins." However, like his father and mother before him and most of his boyhood, (poor) friends, who divorced themselves from these "rule only by the elite" "Brahmins" opting instead for republican political and ethical reasons, to remain NON-Brahmins. Henry's father, George, had a modest education, who came back to Boston from New York reluctantly, to escape poverty. George jointly founded a brokerage as a junior partner, was extremely patriotic, and never owned a house or a horse of his own until within a few years of his death. Henry's mother died of tuberculosis, from which she suffered for some time, when Henry was 15. After withdrawing twice due to eye fatigue problems, he graduated from Boston Latin School in 1851, and began studies at Harvard College. However after 4 months he withdrew since his fatigued eyes grew too weak to study, and he was sent to Europe. Upon returning to Boston in March 1855, Henry's father secured a position for him in the office of Messrs. Samuel and Edward Austin, India merchants, a small shipping counting house on India Wharf where he worked as the sole company clerk and bookkeeper.

He entered the Union Army on May 11, 1861, as second lieutenant of Company D in Colonel George H. Gordon's 2nd Massachusetts Regiment. In the First Battle of Bull Run, his regiment was ordered to hold the nearby town of Harpers Ferry. Higginson was commissioned major in the cavalry on March 26, 1862. On June 17, 1863, the 1st Massachusetts Cavalry engaged the soldiers of General J.E.B. Stuart and General Fitzhugh Lee's cavalry at the Battle of Aldie. During this battle, Higginson crossed sabers with a foe and was knocked out of his saddle with three saber cuts and two pistol wounds. As his wounds slowly healed in Boston, he married Ida Agassiz, daughter of Harvard professor Louis Agassiz, on December 5, 1863.

After the war, he worked as an agent for the Buckeye Oil Company in Ohio, January to July 1865, purchasing equipment and contracting laborers to work in the oil fields. In October 1865, he and friends paid $30,000 for five thousand acres (20 km²) of cotton-farming land in Georgia. This failed philanthropic adventure left him more than $10,000 in debt. Reluctantly at first, out of desperation, he started as a clerk, and later became a junior partner in his father's business of Lee, Higginson and Co on January 1, 1868, which at that time, was a modest brokerage. His father had been a junior partner until 1858 and worked till his death in 1889 at age 85.

This brokerage and banking company eventually became very profitable, and in March 1881, Higginson published (for Boston newspapers) his plan for a Boston orchestra that would perform as a "permanent orchestra, offering the best music at low prices, such as may be found in all the large European cities". This became the Boston Symphony Orchestra and its "concerts of a lighter kind of music" offspring, the Boston Pops Orchestra, which he generously funded for many years. It is fair to say that neither would have existed without Higginson's extraordinary energy and generosity.

It should be noted that as sole administrator of the BSO during these early years, Higginson assured success of his new organization by tightly controlling the professional musicians who worked under him. In 1882, Higginson forged a new contract requiring his musicians to make themselves available on a regular working basis (unusual for musicians of the time) and to "play for no other conductor or musical association." Other established Boston orchestras simply couldn't keep up with Higginson financially, making them "unable to compete for the services of Boston's musicians."

Despite an outcry from the press, Higginson rode out the controversy and went on to further strengthen his grip on his musicians. For example, Higginson aggregated control by "threatening to break any strike with the importation of European players." Furthermore, over time he dropped musicians with ties to Boston, and imported men from Europe of "high technical accomplishment, upon whose loyalty he could count."

From the very beginning through at least the first 30 years of the BSO, through a key contact, a Jewish friend in Vienna (Julius Epstein), Higginson had access to a continuous stream of the best musical artists in the world that happened to be mostly European and German speaking. (most, learning well from the time of Friedrich Schiller up through the turmoil of the Revolutions of 1848, liked the American Republic a lot, especially since all the attempts at similar constitutional republics in Europe were all crushed out by one despot after another).

In 1882, he was awarded an honorary Master of Arts degree from Harvard University and served as the first president of the new Harvard Club of Boston during a time when Higginson helped raise a lot of money to send non-wealthy, non-Brahmins to Harvard especially with the principal goal to train-well, many future teachers for the Republic, from all walks of life.

He was awarded an honorary LL.D. from Yale University in 1901. He served as president of the Boston Music Hall and as director of the New England Conservatory of Music. His minor autocratic tendencies towards the musicians under him (he wanted all Beethoven Symphonies performed at least once per season) was tempered by a generous philanthropic public persona characterized by substantial acts of charity[10](some anonymously) For example, on June 5, 1890, Higginson presented Harvard College a gift of 31 acres of land, which he called the Soldier's Field, given in honor of his friends James Savage, Jr., Charles Russell Lowell, Edward Barry Dalton, Stephen George Perkins, James Jackson Lowell, Robert Gould Shaw, all of whom perished in the Civil War.

Higginson was very active in promoting quality education to citizens from all walks of life. Unlike the worst of the Brahmin, he truly believed that "All men are created equal." In 1891, Higginson established the Morristown School for young men in Morristown, New Jersey, declining to be named as the school's founder. (In 1971 it merged with Miss Beard's School to become today's Morristown-Beard School.) In 1899, Higginson contributed $150,000 for the construction of the Harvard Union, a "house of fellowship" for all students of Harvard and Radcliffe, where they could dine, study, meet, and listen to lectures. In 1916, he accepted election to honorary membership in Phi Mu Alpha Sinfonia music fraternity. He is buried in Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

She was born the daughter of David Stewart, a business owner from New York and Adelia Smith. She married a wealthy Boston financier John Lowell Gardner in 1860 at the age of twenty. Everyone called him Jack, and everyone called her Mrs. Jack. From her home in Boston which acted as the center of her own little solar system, she seemed to continually hold aloft a whole host of artists - musicians, writers, painters, all floating around her in various orbits. She had a bundle of energy and seemed to delight in ruffling the feathers of her fellow Bostonian socialites with her audaciousness.

As fast as her husband brought in their huge fortune, she was just as determined to spend it on art, and by the time of her death had amassed an amazing collection that is now part of a museum which bears her name.

The first time Mrs. Jack met Sargent was in England in 1886 by introduction of Henry James. When he finally paints her two years later it would be on his first professional trip to America. The painting started in December of 1887 in Boston. For Sargent, it proved difficult. She was a restless sitter, given her high energy, she would continually look out the window to see what was happening on the river outside their home at 152 Beacon Street, Boston. Sargent grew frustrated and after eight unsuccessful attempts was willing to give the entire enterprise up but Mrs. Jack was reported to have insisted " . . . as nine was Dante's mystic number, they must make the ninth try a success" and it was.

Sybil was the wife of Sir William Eden, and mother of Elfrida Marjorie Eden (1887-1943). Marjorie or Miss Eden is the subject of the rare watercolor portrait we see here (I believe it dates from1905). Marjorie married Guy, Lord Brooke, in 1909, and became Countess of Warwick in 1924.

At this time, Sargent was far more popular with Americans and although Elsie herself was American it would be paintings such as this that did much to break the ice with the British and eventually bring them around to Sargent style.

"The mysterious and rather nervy face of Mrs Russell is characteristic of Sargent's elegant female portraits. The palette of ochres, silvers and pale pink is rather sober, while the rapid brushstroke is a characteristic example of Sargent's great skill and refinement."

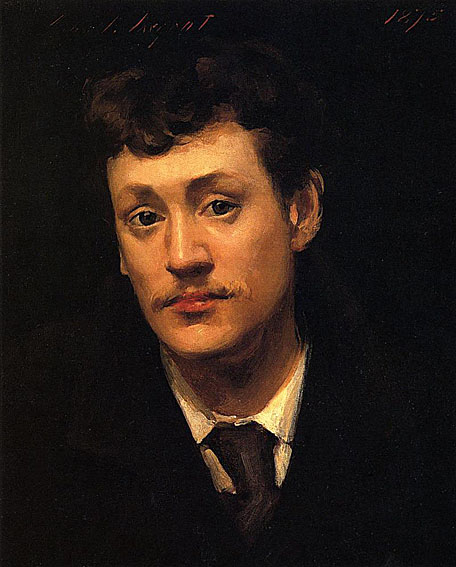

Sargent obviously cared for the kid and Albert seemed to have been in awe of the rising star of Paris and clearly the most talented in Carolus-Duran's atelier. Albert took the kidding and did the things underclassmen do in order to learn -- playing gofer, cleaning brushes, stoking the fire in the stove in the winter, and modeling.

Albert is featured in many drawings and sketches by Sargent and when every nuance and feature had been explored, Sargent just plopped a Spanish hat and coat he'd brought back from his trip to Spain in order to give him something else to paint.

Parallels between Sargent's own family and Bessie are strong. Sargent's sister Emily suffered from deformity of the spine at an early age as a result of a diving accident; and she, like Bessie, took on much of the responsibility of the family domestic life from Sargent's mother who was always suffering from one ailment or another as they were growing up and traveling throughout Europe.

Sargent's admiration for this spirited woman is most evident both in this painting and his observations to others. She was, in effect, the type of woman Sargent admired most and reported to have said that Bessie had the face of the Madonna and the eyes of a child.

There is no way the image here shows adequately the thick paint, and the rapid brush strokes of this portrait, but it’s typical of many of Sargent’s paintings which he did of friends in his bravura style.

Alberto Falchetti (Born 1878- died-1956 - or there about) is the son of Giuseppe Falchetti (b1843-died in Torino 1918) both from Caluso, Italy. From my understanding Alberto studied with the masters. But I have no confirmation of that. Even though his paintings that I've seen show the style of that period -- 1800's. Both Giuseppe & Alberto [father and son] are painters.

We just found out last year Alberto Falchetti is a direct relative.

My Father-in-laws' Parents both were born in Caluso, Italy & from what I have found out, Guy Falchetti was a youngest of several children. His parents died & he was sent to Brazil to be raised by his sister. Then he moved on to Pennsylvania. This is where the family has been since.

My niece went to Caluso a couple of summers ago, and it seems the Falchetti home has been turned into a Museum. I just thought maybe someone would have some other information.

I have been doing some research on the web, and to take a peek at his other works. He's got some magnificent works in his home place of Turin, Italy. Some of his miniatures have been bought and have made it to the US. If you have any additional information for my father in law who is named after this artist.

Much appreciation,

Cheri Falchetti

.jpg)

Supposedly, the painting was given to Antonio (the sitter) in appreciation as a gift, who in turn inscribed it (sometime later in London) under Sargent's signature with the words: "Mancini ringrazia / devotamente Mr Sargent / che e così buono / con il pittore cattivo Manciney / Londra-- It was then dated, but illegible to us now.

("Mancini thanks/devotedly Mr Sargent/whom is so good/to this bad painter Manciney/London")

Mancini then gave the painting away to the cook of Asher Wertheimer -- both men knew the Wertheimers well -- you can see Sargent had painted him with one of Wertheimer's daughters in '04. Somehow, sometime, Sargent's gift made it's way back to Sargent -- it's thought by Asher Wetheimer. Mancini's inscriptions is known because it's shown up in photos of the painting in Sargent's studio, but it has since been cut away -- believed done by Sargent.

John, we know, believed Mancini to be a great painter and Sargent went to great lengths to promote the artist to clients. To have his gift find its way back with that inscription and knowing his friend's history of melancholy and emotional instability would have been tough.

When exactly the painting made its way back, we don't know. But Sargent kept it with his personal collection (uncropped, or at least long enough to be caught in a photo), along with a number of paintings by Mincini (which he cherished) and only near the end of his life -- and in honor to his friend -- did he part with it -- as a gift (less the Mincini's inscription) to the Galleria Nazional d'Arte Moderna, Rome, in 1925, where it would pay proper tribute to his friend and painter.

The ancestors of the Vlasto family have been traced back to the island of Chios (Greece) and Constantinople (Turkey) of the 15th century. They were a noble family but were scatted in the 16th century to escape persecution from the Turks. By the 1800's they were all over Europe. Although Catherine was born in London, her father -- Alexandre (Antoine) Vlasto -- was born in Trieste, Italy (1833), and his father was born on the Greek island of Chios (1804).

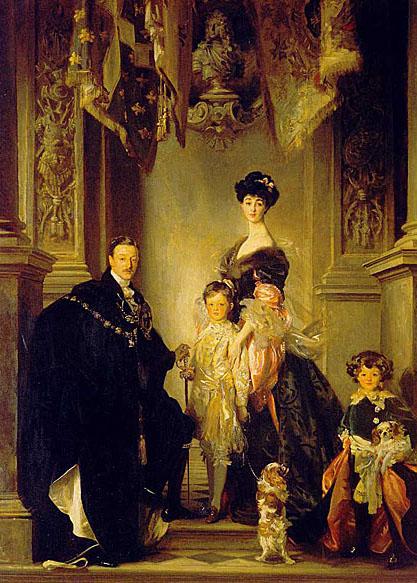

In ''Lord Londonderry,'' the central figure, dressed in white, holds a massive sword firmly in his hands. ''It's called the `Great Sword of State,' and it is a symbol of all the majesty of the king,'' Rogers says. ''I think it's kept in the Tower of London. It's not quite 4 feet, but it looks pretty big.''

From: Wilfredo Fernandez

I am a member of the family of Benjamin Nunez del Castillo, now in Miami since 1964.

Sargent was indeed a long time friend of my cousin Ben, Madame x was a cousin of his (Ben's) on his mother side of the family, and according to family info, Sargent was sort of in love with her. The descendants of Ben are all Italians and that's where they are, they still hold several of his paintings.

I am trying to obtain copies of the portraits of my family, Laura Spinola Nunez del Castillo and her son Rafael, by Sargent, I have no addresses of his descendants in Italy. I have a good copy of Laura and have seen photos of the painting of Rafael which was stolen years ago, but have never seen the painting of Benjamin; he was a cousin of my grandfather. My name is Wilfredo Gabriel Fernandez-Nunez del Castillo.