Disclaimer

Anthony Van Dyck

Flemish Baroque Painter

1599 - 1641

Self Portrait of Anthony Van Dyck

The painting represents the painter at 20, although it was painted later. The picture is based on an earlier, now lost, study. There are two other versions of the painting in Munich and in a private collection in New York, respectively.

Sir Anthony van Dyck was a Flemish Baroque artist who became the leading court painter in England. He is most famous for his portraits of King Charles I of England and Scotland and his family and court, painted with a relaxed elegance that was to be the dominant influence on English portrait-painting for the next 150 years. He also painted biblical and mythological subjects, displayed outstanding facility as a draftsman, and was an important innovator in watercolor and etching.

Van Dyck was born to prosperous parents in Antwerp. His talent was evident very early, and he was studying painting with Hendrick van Balen by 1609, and became an independent painter around 1615, setting up a workshop with his even younger friend Jan Brueghel the Younger. By the age of fifteen he was already a highly accomplished artist, as his Self-portrait, 1613-14, shows.

Self Portrait: 1613-14

He was admitted to the Antwerp painters' Guild of Saint Luke as a free master by February 1618. Within a few years he was to be the chief assistant to the dominant master of Antwerp, and the whole of Northern Europe, Peter Paul Rubens, who made much use of sub-contracting artists as well as his own large workshop. His influence on the young artist was immense; Rubens referred to the nineteen-year-old van Dyck as 'the best of my pupils'. The origins and exact nature of their relationship are unclear; it has been speculated that Van Dyck was a pupil of Rubens from about 1613, as even his early work shows little trace of van Balen's style, but there is no clear evidence for this. At the same time the dominance of Rubens in the small and declining city of Antwerp probably explains why, despite his periodic returns to the city, van Dyck spent most of his career abroad. In 1620, in the Rubens' contract for the major commission for the ceiling of the Jesuit church at Antwerp (now destroyed), van Dyck is specified as one of the "discipelen" who was to execute the paintings to Rubens' designs.

In 1620, at the instigation of the brother of the Duke of Buckingham, van Dyck went to England for the first time where he worked for King James I and James VI, receiving £100. It was in London in the collection of Earl of Arundel that he first saw the work of Titian, whose use of color and subtle modeling of form would prove transformational, offering a new stylistic language that would enrich the compositional lessons learned from Rubens.

After about four months he returned to Flanders, but moved on in late 1621 to Italy, where he remained for 6 years, studying the Italian masters and beginning his career as a successful portrait painter. He was already presenting himself as a figure of consequence, annoying the rather bohemian Northern artist's colony in Rome, says Bellori, by appearing with "the pomp of Xeuxis... his behavior was that of a nobleman rather than an ordinary person, and he shone in rich garments; since he was accustomed in the circle of Rubens to noblemen, and being naturally of elevated mind, and anxious to make himself distinguished, he therefore wore - as well as silks - a hat with feathers and brooches, gold chains across his chest, and was accompanied by servants."

He was mostly based in Genoa, although he also travelled extensively to other cities, and stayed for some time in Palermo in Sicily. For the Genoese aristocracy, then in a final flush of prosperity, he developed a full-length portrait style, drawing on Veronese and Titian as well as Ruben's style from his own period in Genoa, where extremely tall but graceful figures look down on the viewer with great hauteur. In 1627, he went back to Antwerp where he remained for five years, painting more affable portraits which still made his Flemish patrons look as stylish as possible. A life-size group portrait of twenty-four City Councilors of Brussels he painted for the council-chamber was destroyed in 1695. He was evidently very charming to his patrons, and, like Rubens, well able to mix in aristocratic and court circles, which added to his ability to obtain commissions. By 1630 he was described as the court painter of the Hapsburg Governor of Flanders, the Archduchess Isabella. In this period he also produced many religious works, including large altarpieces, and began his printmaking.

King Charles I was the most passionate and generous collector of art among the British monarchs, and saw art as a way of promoting his grandiose view of the monarchy. In 1628 he bought the fabulous collection that the Gonzagas of Mantua were forced to dispose of, and he had been trying since his accession in 1625 to bring leading foreign painters to England. In 1626 he was able to persuade Orazio Gentileschi to settle in England, later to be joined by his daughter Artemesia and some of his sons. Rubens was an especial target, who eventually came on a diplomatic mission, which included painting, in 1630, and later supplied more paintings from Antwerp. He was very well treated during his nine month visit, during which he was knighted. Charles' court portrait painter Daniel Mytens, was a somewhat pedestrian Fleming. Charles was extremely short (less than five foot tall) and presented challenges to a portrait painter.

Van Dyck had remained in touch with the English court, and had helped King Charles' agents in their search for pictures. He had also sent back some of his own works, including a portrait (1623) of himself with Endymion Porter, one of Charles's agents, a mythology (Rinaldo and Armida, 1629, now in the Baltimore Museum of Art), and a religious work for the Queen.

Rinaldo and Armida: 1629

Tasso, Torquato (1544-95), Italian poet, author of a romantic epic Rinaldo (1562), a pastoral play very popular in his time, Aminta (1573); the epic poem Jerusalem Delivered (150-81) about the first crusade. The subjects from his works were used by the artists.

Armida in Tasso's Jerusalem Delivered, is a powerful enchantress. She offered her service to the defenders of Jerusalem when it was besieged by the Christians under Godfrey de Bouillon; visiting the Christian camp she lured away by her beauty many of the principal knights. She enticed them by her magic power into a delicious garden, where they were overcome by apathy and pleasant half dream. Among her captives were Renaud (or Rinaldo) of Este and Tancred.

He had also painted Charles's sister, Queen Elizabeth of Bohemia in The Hague in 1632. In April that year, van Dyck returned to London, and was taken under the wing of the court immediately, being knighted in July and at the same time receiving a pension of 200 Pounds per year, in the grant of which he was described as principalle Paynter in ordinary to their majesties. He was well paid for paintings in addition to this, at least in theory, as King Charles did not actually pay over his pension for five years, and reduced the price of many paintings. He was provided with a house on the river at Blackfriars, then just outside the City and hence avoiding the monopoly of the Painters Guild. A suite of rooms in Eltham Palace, no longer used by the Royal family, was also provided as a country retreat. His Blackfriars studio was frequently visited by the King and Queen (later a special causeway was built to ease their access), who hardly sat for another painter while van Dyck lived.

Eltham Palace Today

The original palace was given to Edward II in 1305 by the Bishop of Durham, Anthony Bek, and used as a royal residence from the 14th to the 16th century. According to one account the incident which inspired Edward III's foundation of the Order of the Garter took place here. As the favorite palace of Henry IV it played host to Manuel II Palaiologos, the only Byzantine emperor ever to visit England, from December 1400 to January 1401, with a joust being given in his honor. There is still a jousting tilt yard. Edward IV built a Great Hall in the 1470's, and Prince Henry also grew up here; it was here that he met and impressed the scholar Erasmus. Tudor courts often used the palace for their Christmas celebrations. With the grand rebuilding of Greenwich Palace, which was more easily reached by river Eltham was less frequented, save for the hunting in its enclosed parks, easily reached from Greenwich, "as well enjoyed, the Court lying at Greenwich, as if it were at this house itself". The deer remained plentiful in the Great Park, of 596 acres, the Little or Middle Park, of 333 acres, and the Home Park, or Lee Park, of 336 acres. In the 1630's, by which time the palace was no longer used by the royal family, Sir Anthony van Dyck was given the use of a suite of rooms as a country retreat. During the English Civil War, the parks were denuded of trees and deer. John Evelyn saw it 22 April 1656: "Went to see his Majesty's house at Eltham; the palace and chapel in miserable ruins, the noble wood and park destroyed by Rich the rebel". The palace never recovered. Eltham was bestowed by Charles II on John Shaw and- in its ruinous condition, reduced to Edward IV's Great Hall, the former buttery, called "Court House", a bridge across the moat and some walling- remained with Shaw's descendants as late as 1893. In 1995 English Heritage assumed management of the palace.

He was an immediate success in England, rapidly painting a large number of portraits of the King and Queen Henrietta Maria, as well as their children. Many portraits were done in several versions, to be sent as diplomatic gifts or given to supporters of the increasingly embattled king. Altogether van Dyck has been estimated to have painted forty portraits of King Charles himself, as well as about thirty of the Queen, nine of Earl of Strafford and multiple ones of other courtiers. He painted many of the court, and also himself and his mistress, Margaret Lemon. In England he developed a version of his style which combined a relaxed elegance and ease with an understated authority in his subjects which was to dominate English portrait-painting to the end of the 18th century. Many of these portraits have a lush landscape background. His portraits of Charles on horseback updated the grandeur of Titian's Emperor Charles V, but even more effective and original is his portrait of Charles dismounted in the Louvre: "Charles is given a totally natural look of instinctive sovereignty, in a deliberately informal setting where he strolls so negligently that that he seems at first glance nature's gentleman rather than England's King" Although his portraits have created the classic idea of "Cavalier" style and dress, in fact a majority of his most important patrons in the nobility, such as Lord Wharton and the Earls of Bedford, Northumberland and Pembroke, took the Parliamentarian side in the English Civil War that broke out soon after his death.

Charles I, King of England at the Hunt: ca 1635

This painting, commissioned by the King, is one of the masterpieces of the artist.

Charles I on Horseback: ca 1635

This likeness of the king on horseback takes as its point of departure the archetypal image on the obverse of all the Great Seals of England: the sovereign as warrior. King Charles is wearing Greenwich-made armor and holding a commander's baton. A page carries his helmet. In keeping with the imperial claim of the inscription (in Latin on the tablet tied to the tree in this portrait: CAROLUS REX MAGNAE BRITANIAE - Charles King of Great Britain), the pose and woodland setting echo Titian's equestrian portrait of the Emperor Charles V at Muhlberg. (Titian's painting itself recalled the famous Roman bronze of the Emperor Marcus Aurelius on horseback.) Over his armor Charles wears a gold locket bearing the image of Saint George and the Dragon, the so-called Lesser George. He wore it constantly; it contained a portrait of his wife, and was with him the day he died. Here, however, it identifies him with the Order of the Garter of which Saint George was patron. As Garter Sovereign he is riding, like Charles V, at the head of his chivalrous knights in defense of the faith. In a profound sense the portrait is a visual assertion of Charles's claim to Divine Kingship. Albeit high above our heads - the horizon line ensures that our viewpoint is roughly at the level of his stirrup - his face is undistorted by foreshortening. Van Dyck's three-quarter view refines his features, and he bestrides his horse with a remote air of noble contemplation.

Equestrian Portrait of Charles I, King of England: 1635-40

Charles I, King of England: 1636

Charles I (1600-1649) king of Great Britain and Ireland, second son of James VI and I and Anne of Denmark. He married Henrietta Maria, sister of French king Louis XIV in 1625, after he succeeded his father in March 1625. He was under the influence of the Duke of Buckingham until his assassination in 1628. Three Parliaments were summoned and dismissed in the first four years of his reign; then for eleven years Charles ruled without one. His extension of the ship tax to the inland counties met resistance of the landowners and his attempt in 1637 to Anglicize the Scottish Church resulted in the active resistance of the Scots. In 1640, Charles was forced to summon the Parliament to raise money for the war. The "Short Parliament" was dismissed in three weeks, the "Long Parliament" outlasted the King. Parliament demanded from Charles to remove his chief advisors the Earl of Strafford and Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury. The Earl of Strafford was sacrificed by the King to insure the Queen's safety and was executed in May 1641 by the Act of Parliament. Charles was also forced to sign a document which stated that the existing parliament would not be dissolved without his own consent. In 1642, Charles tried to arrest five members of the Parliament, which led to the Civil War (1642-1646). Charles was defeated and on the 5th of May, 1646 he surrendered to the Scots at Newark. He was subjected to trial at Westminster. Charles faced it bravely and with dignity. Three times he refused to plead, denying the authority of such a court, he was found guilty and sentenced to public execution. On the 30th of January 1649 he died on the scaffold in front of the Whitehall with courage worthy of a martyr. Charles had six children, who outlived him: Charles II (1630-1685), James II (1633-1701), Mary, Princess of Orange (1631-1660), Elizabeth (1635-1650), Henry, Duke of Gloucester (1639-1660) and Henrietta Anne, Duchess of Orleans (1644-1670).

Charles I in Three Positions: 1635-36

This Portrait of Charles I From Three Angles was painted by Van Dyck for the Italian sculptor Bernini, who was commissioned by Pape Urban VIII to make the bust of Charles I. The bust was indeed created by Bernini in 1636 and was greatly admired by the King. Unfortunately it was lost in the fire in the Whitehall Palace in 1698. See the copy of it.

Charles I of England and Henrietta of France

In April 1632 King Charles I (1600-49) succeeded in attracting Van Dyck, in demand as a painter of religious and mythological pictures as well as of portraits in Antwerp, to London. In July of that year the artist, now Principal Painter in Ordinary to their Majesties was knighted at Saint James's. From that time he was to have a virtual monopoly of portraits of the king and queen on the scale of life, having rendered the work of his predecessors at court old-fashioned. In a series of huge canvases strategically placed at the end of great galleries in the king's various residences, he displayed the power and splendor of the British monarchy and of the early Stuart dynasty, modernizing traditional themes of royal homage and tribute.

Queen Henrietta Maria: 1632

On 8 August 1632, Charles I authorized payment to Van Dyck for 20 Pounds for 'One of our royal Consort'. This was perhaps the first single portrait of Queen Henrietta Maria painted by Van Dyck after his arrival in London, and it provided a type from which many variations by the artist and his assistants followed.

The charm of the portrait is matched by the lightness of tone and touch with which it is painted: the silvery-grey dress, against dark green, setting off pale pinkish scarlet bows and the pink roses under her right hand. The flesh is modeled with extreme delicacy and her fashionable dress is also recorded with great care. The curtain originally projected more to the left and seems to have been altered by Van Dyck to its present form, and there are signs of alterations down the shadowed area of the Queen's left sleeve. This painting was probably the source of the Queen's portrait in the series of royal portraits in the Mortlake tapestry at Houghton Hall, Norfolk.

Inscribed centre left, with her monogram, HMR, under a crown.

Henrietta Maria and the Dwarf Sir Jeffrey Hudson: 1633

The queen's love of amusement is symbolized by the presence of the dwarf and monkey, both royal favorites. Jeffrey Hudson, the fourteen-year-old dwarf, had been given to her as a gift and remained a faithful companion until her death.

s

The portrait is a superb demonstration piece of van Dyck's working methods and the reasons for his phenomenal success. Henrietta probably posed only briefly for a sketch, so the painting itself had to be executed from a model or mannequin attired in the queen's costume. The artist shows a tall woman with an oval face, pointed chin, and long nose. According to sketches done from life, however, she actually was a tiny person with a petite figure, round head, and small features. She thus has been greatly idealized. The fluted column emphasizes her already exaggerated height, and the crown and cloth of gold signify her royalty.

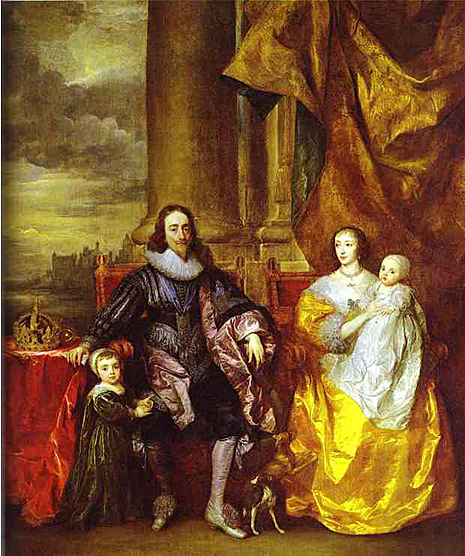

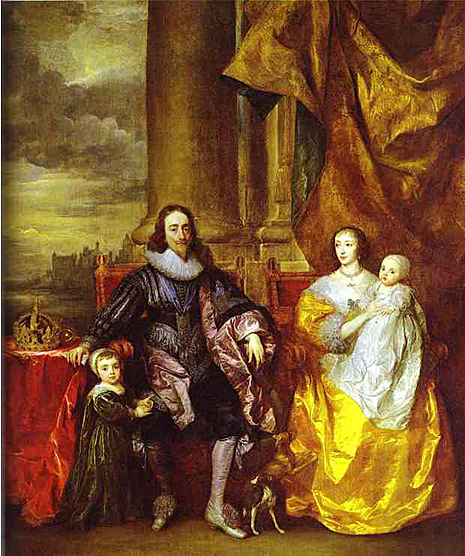

Charles I and Queen Henrietta Maria with Charles Prince of Wales and Princess Mary: 1632

The Children of Charles I of England-painting by Sir Anthony van Dyck: 1637

Van Dyck's masterful painting acknowledges both the youth and the status of its royal subjects, breaking with the earlier tradition of presenting royal children as miniature adults. The picture was commissioned by Charles I but left the Royal Collection twice, during the Commonwealth and under James II, before being repurchased by George III in 1765 and hung (by 1774) in the King's Apartments at Buckingham House. The synthesis that Van Dyck achieved in the portrait was described by the nineteenth-century artist Sir David Wilkie: 'the simplicity of inexperience shows them in most engaging contrast with the power of their rank and station, and like the infantas of Velasquez, unite all the demure stateliness of the court, with the perfect artlessness of childhood.

George III's admiration for the early Stuarts and the aesthetic of Charles I's court was reflected in this purchase and he hung many of his finest Van Dyck's in Buckingham House. However, eighteenth-century attitudes towards childhood, which was increasingly regarded as a distinct, innocent phase of life, are reflected in many of the portraits of George III's children.

George III's taste for Van Dyck might have been sparked by that of his father, Frederick, Prince of Wales, who had a high regard for the collection of Charles I and had purchased Van Dyck's double portrait of Thomas Killigrew and William, Lord Crofts, in 1748. Similarly, George IV's interest in the later Stuarts, and his attempts to reclaim items associated with the exiled dynasty, may equally have been inspired by his father.

Signed and dated Antony van dyck Eques Fecit, / 1637

Portrait of Charles II When Prince of Wales

The design of this portrait dates from 1637 or early 1638. The Prince does not wear the insignia of the Garter (he was installed on 21 May 1638) and the portrait is so close in type to the figure of the Prince in the painting of 'The Five Eldest Children of Charles I' of 1637 as to suggest it derived from the same sittings. It was painted for the royal family portrait gallery in the Cross Gallery at Somerset House and its unusual shape may have been dictated by its original position there, possibly over a door.

William II Prince of Orange and Princess Henrietta Mary Stuart daughter of Charles I of England: 1641

Princess Mary Stuart (1631-1660), the eldest daughter of Charles I, she was married at the age of 10, in 1641 to Prince William of Orange (future William II), stadholder and captain-general of the Netherlands. They had a son, future English King William III, husband of Mary II.

Van Dyck became a "denizen", effectively a citizen, in 1638 and married Mary, the daughter of Lord Ruthven and a Lady in waiting to the Queen, in 1639-40; this may have been instigated by the King in an attempt to keep him in England. He had spent most of 1634 in Antwerp, returning the following year, and in 1640-41, as the Civil War loomed, spent several months in Flanders and France. He left again in the summer of 1641, but fell seriously ill in Paris and returned hurriedly to London, where he died soon after in his house at Blackfriars. He left a daughter each by his wife and mistress, the first only ten days old. Both were provided for, and both ended up living in Flanders.

He was buried in Old Saint Paul's Cathedral, where the king erected a monument in his memory:

Anthony returned to England, and shortly afterwards he died in London, piously rendering his spirit to God as a good Catholic, in the year 1641. He was buried in Saint Paul's, to the sadness of the king and court and the universal grief of lovers of painting. For all the riches he had acquired, Anthony van Dyck left little property, having spent everything on living magnificently, more like a prince than a painter.

With the partial exception of Holbein, van Dyck and his exact contemporary Velazquez were the first painters of pre-eminent talent to work mainly as Court portrait painters. The slightly younger Rembrandt was also to work mainly as a portrait painter for a period. In the contemporary theory of the Hierarchy of genres portrait-painting came well below History painting (which covered religious scenes also), and for most major painters portraits were a relatively small part of their output, in terms of the time spent on them (being small, they might be numerous in absolute terms). Rubens for example mostly painted portraits only of his immediate circle, but though he worked for most of the courts of Europe, he avoided exclusive attachment to any of them.

A variety of factors meant that in the 17th century demand for portraits was stronger than for other types of work. Van Dyck tried to persuade Charles to commission him to do a large-scale series of works on the history of the Order of the Garter for the Banqueting House, Whitehall, for which Rubens had earlier done the huge ceiling paintings (sending them from Antwerp).

A sketch for one wall remains, but by 1638 Charles was too short of money to proceed. This was a problem Velazquez did not have, but equally van Dyck's daily life was not encumbered by trivial court duties as Velázquez's was. In his visits to Paris in his last years van Dyck tried to obtain the commission to paint the Grande Gallerie of the Louvre without success.

A list of history paintings produced by van Dyck in England survives, by Bellori, based on information by Sir Kenelm Digby; none of these still appear to survive, although the Cupid and Psyche done for the King does. But many other works, rather more religious than mythological, do survive, and though they are very fine, they do not reach the heights of Velzquez's history paintings. Earlier ones remain very much within the style of Rubens, although some of his Sicilian works are interestingly individual.

Cupid and Psyche: 1639-40

Cupid and Psyche is without doubt one of the most beautiful paintings undertaken by Van Dyck for Charles I. It is a late work, possibly dating from 1639-40, thinly painted throughout with several changes visible to the naked eye and some passages, particularly in the landscape, unresolved to the extent that the painting might not have been properly finished. Significantly, when first recorded in the Long Gallery at Whitehall Palace the picture was unframed. Both these factors might have some bearing on the circumstances of the commission. It has been suggested, for example, that the subject relates to the decoration of the Queen's Cabinet at Greenwich, which was initiated towards the end of 1639 by Rubens and Jacob Jordaens but was never completed - although a certain amount of preparatory material by Jordaens is recorded. Alternatively, the painting could have been made in the context of the celebrations for the marriage of Princess Mary to William II of Orange (April-May 1641).

The story of Cupid and Psyche was well known at the English court. The source is The Golden Ass by Apuleius (Books 4-6). Van Dyck has chosen the moment when Cupid discovers Psyche overcome by sleep after opening the casket which Venus had requested her to bring back, unopened, from Proserpine in Hades. This was one of the tricks set by Venus in Psyche's attempt to find Cupid. Compositionally, there is a kinship with paintings of Adam and Eve or the Annunciation. It is stated traditionally that Psyche's features resembled those of Van Dyck's mistress, Margaret Lemon.

Van Dyck's role as court painter seems primarily to have been directed towards portraiture, even though he was a supremely able painter of poesie in the Italian tradition. Cupid and Psyche is the only mythological composition known to survive from the time of the artist's full employment at the English court (after 1632). Bellori records that other mythological paintings were made but these are now lost. This accounts for the long gap between the Rinaldo and Armida (Baltimore, Museum of Art), which the king commissioned in 1630 before the artist settled permanently in London, and Cupid and Psyche. In many ways the later painting may be seen as a summation of Van Dyck's art in this field. The composition successfully combines the artist's feeling for landscape with his understanding of the human form, both aspects being conveyed through superb draftsmanship, here successfully conflated by the skilful use of diagonals. The sense of movement implied by Cupid's arrival contrasts with the stillness of Psyche asleep to create a tension that is the very essence of the picture, matching perfectly the contrast within the story itself between Beauty (Psyche) and Desire (Cupid). Such ethereal neo-Platonic ideals, which were open to various interpretations about love and the soul, were nurtured as part of the court life of Charles I and Henrietta Maria.

Stylistically, the principal inspiration is Titian, whose pictures were such a major feature of Charles I's collection, but the highly charged poetic feeling, refined use of colors balancing warm and cold hues, and delicate modeling of human flesh that Van Dyck brings to the painting anticipate French Rococo art, especially the work of Watteau. In addition, it should not be forgotten that Cupid and Psyche was painted on the eve of the outbreak of the Civil War, so in many respects the choice of subject and the poetic intensity of the painting have a certain poignancy when seen in an historical context.

Van Dyck's portraits certainly flattered more than Velazquez's; when Sophia, later Electoress of Hanover, first met Queen Henrietta Maria, in exile in Holland in 1641, she wrote: "Van Dyck's handsome portraits had given me so fine an idea of the beauty of all English ladies, that I was surprised to find that the Queen, who looked so fine in painting, was a small woman raised up on her chair, with long skinny arms and teeth like defense works projecting from her mouth..." Some critics have blamed van Dyck for diverting a nascent tougher English portrait tradition, of painters such as William Dobson, Robert Walker and Issac Fuller into what certainly became elegant blandness in the hands of many of van Dyck's successors, like Lely or Kneller. The conventional view has always been more favorable: "When Van Dyck came hither he brought Face-Painting to us; ever since which time England has excelled all the World in that great Branch of the Art'. Thomas Gainsborough is reported to have said on his deathbed "We are all going to heaven, and Van Dyck is of the Company."

A fairly small number of landscape pen and wash drawings or watercolors made in England played an important part in introducing the Flemish watercolor landscape tradition to England. Some are studies, which reappear in the background of paintings, but many are signed and dated and were probably regarded as finished works to be given as presents. Several of the most detailed are of Rye, a port for ships to the Continent, suggesting that van Dyck did them casually while waiting for wind or tide to improve.

Portrait of a Man in Armour with Red Scarf: 1625-27

During his extended stay in Italy from 1621 to 1627, spending the majority of his time in Genoa, Van Dyck made his mark as a portraitist, and numbered many important families from the upper strata of Genoese society among his clients. It has yet to be clarified whether or not the Portrait of a Man in Armor with Red Scarf was one of these commissions; various attempts to identify the man in the picture have been inconclusive. It is also possible that the painting is not a portrait but an allegory.

Portrait of a Member of the Balbi Family: ca 1625

Balbi was a large Genoese family with banking and commercial interests in Antwerp.

Portrait of Prince Charles Louis, Elector Palatine: 1641

The sitter of this portrait is the young Prince Charles Louis (1617-1680), the nephew of King Charles I. The excellent portrait was painted directly from the life in London a few months before the death of van Dyck.

Portrait of the Painter Cornelis de Wae: ca 1627

Diana Cecil, Countess of Oxford: 1638

Portrait of Marcello Durazzo: 1642

During his first three years in Genoa, Van Dyck was paid for portraits of Marcello Durazzo and his wife Caterina Balbi (now in Genoa). The traditional configuration features celebratory elements, such as the column and drapes, but the relaxed execution and the nobleman's insouciant pose point to a new and entirely individual sensitivity.

With his usual freedom, Van Dyck painted this Genoese Marquis leaning against a pillar in a relaxed and negligent pose; yet the keen, forceful gaze also suggests the nobleman's spirited, imperious character.

Cornelis van der Geest: Ante 1620

An early work by Van Dyck, pupil of Rubens that time. Cornelis van der Geest was a merchant and art collector in Antwerp, and the friend of Rubens.

Portrait of a Young General: 1622-27

Van Dyck executed this painting during his stay in Italy. It represents a young general standing at the entrance of a tent. The sitter of the portrait is unknown, probably he was a member of the Gonzaga family.

An Aristocratic Genoese: 1622-26

The companion-piece of this painting represents the wife of the sitter.

Wife of an Aristocratic Genoese: 1624-26

Marchesa Elena Grimaldi: ca 1623

The Genoese noblewoman is shown on the terrace of her palace. The soaring columns and cloud-swept sky add a sense of height and dignity to the majestic figure, while the brilliant red parasol relieves the otherwise somber color scheme. The Genoese nobility, wealthy from the trade of its powerful merchant marine, had many ties with members of the Spanish court and adopted many customs from them, including the sumptuous but sober fabrics of courtly dress. Van Dyck, in these portraits of his Genoese period, has immortalized the dignity and splendid scale of living of his patrons.

Philippe Le Roy: 1630

Philippe Le Roy was Councellor to the Archduke Ferdinand. The companion portrait of his young wife was painted the following year.

Marie de Raet: 1631

The painting is the companion piece of the portrait of Philippe Le Roy. It was painted on the occasion of their marriage in 1631 when she was sixteen years old.

Portrait of a Lady: 1634-35

The sitter is probably Amelia of Solms, Princess of Orange.

Portrait of a Gentleman: 1624

Self Portrait: 1621

Self-portrait with a Sunflower: ca 1632

Marchesa Geronima Spinola: 1624-26

This portrait from Van Dyck's Genoese period shows his genius for portraiture of rare elegance and profundity.

Portrait of Nicolaes van der Borght: 1620's

The sitter of this portrait is Nicolaes van der Borght, a merchant of Antwerp. His coat of arms is displayed in the top left corner.

Isabella Brandt: ca 1621

The subject is the first wife of Rubens to whom the painting was attributed formerly. The ornamental gateway which Rubens built in his garden in Antwerp forms the architectural background. Van Dyck presented the painting to Rubens as a gift before he left for Italy in 1621. The sitter is about thirty, she died five years later, in 1626, probably of the plague.

Portrait of Philadelphia and Elisabeth Cary: 1635-38

Portrait of a Married Couple

After the years studying in Rubens's workshop and a sojourn in Italy, Van Dyck settled in his native city of Antwerp and soon became one of the most popular portrait painters of the wealthy bourgeoisie. For the most part he painted full-length official likenesses, or else family portraits with the sitters posed in setting of homely intimacy. He devised many different arrangements and poses, suiting them to the character and rank of the sitter, but the effect was always serious, noble and distinguished, and the impression of solemnity and reserve was enhanced by the dark costumes - high-necked black garments with starched ruffs - as in the portrait of the couple in Budapest.

In this picture attention is focused on the sharply characterized faces and expressive, delicately depicted hands, while the black and white of the clothes, the red of the armchair, and the gold of the gloves provide a marvelously harmonious background. We do not know the identity of the married couple, unfortunately, and to discover their connection with any particular Antwerp family seems hardly possible today.

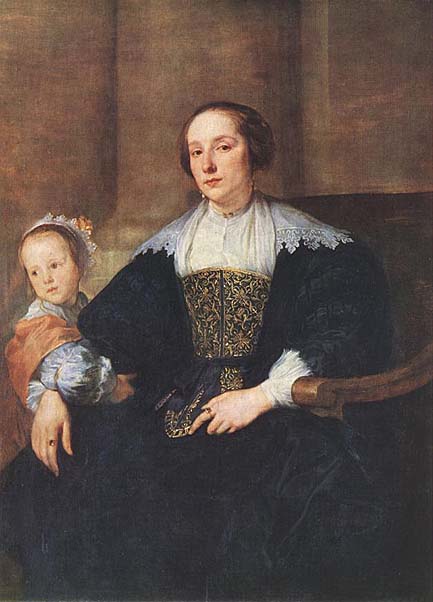

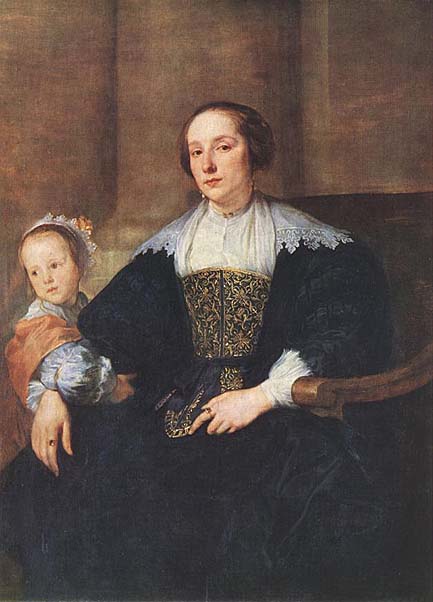

The Wife and Daughter of Colyn de Nole

Sir Endymion Porter and the Artist: 1632-41

Endymion Porter (1587-1649) was a favorite courtier of King Charles I, for whom he bought works of art. His father was a large landowner in Gloucestershire but he was brought up by his grandparents in Spain. He was a judicious collector of pictures, and as the friend of Rubens, Van Dyck, Daniel Mijtens and other painters, and as agent for Charles in his purchases abroad he had a considerable share in forming the King's magnificent collection.

Porrtrait of the Sculptor Duquesnoy: 1627-29

In this portrait by Anthony van Dyck, a brown-haired man, wearing a beard and a moustache, is represented in three-quarter profile, turned to the left against a dark, uniform background. He is wearing a dark cloth garment, decorated with a ruff and white cuffs, and holds a stone sculpted head representing a satyr. The dark colors serve to emphasize the sitter's attentive gaze and elegant hand, whilst the vivacity of the face contrasts with the immobility of the sculpture. For a long time this painting was held to be a portrait of the Brussels sculptor François Duquesnoy, who lived and worked in Rome from 1618 to 1643, where he developed a classical style that was strongly influenced by his study of antique sculpture and by the works of French painter Nicolas Poussin. This portrait would then have been painted during a trip that Anthony van Dyck made to Rome around 1622/23, where he supposedly struck up a friendship with the sculptor.

However, this famous painting presents problems as to the date of painting and in particular the identity of the sitter. The traditional identification was based on an engraving by Pieter van Bleeck in 1751 from the portrait in the Brussels museum, with an inscription mentioning the sculptor's name and a short biographical text. This has recently been called into question. Bellori's biography of the sculptor, published in 1672, mentions neither a friendship between the two men in Rome, nor a portrait of his compatriot by Van Dyck. What the biography does mention is that Duquesnoy was fair-haired and had blue eyes. Moreover, the engraved portrait illustrating his text, repeated in 1675 by Joachim von Sandrart in the Teutsche Academie, shows little resemblance to the present portrait, nor to the late engraving from it by Pieter van Bleeck. In addition, stylistic analysis has shown that the picture could not belong to Anthony van Dyck's Italian period, but must be placed in his second Flemish period, where the color range was more contained. This portrait is indeed by Van Dyck, but after his Italian trip, around 1627/29, when the painter was back in the country to which the Brussels sculptor never returned.

Portrait of Father Jean-Charles della Faille, S.J.: 1629

Van Dyck portrayed the Jesuit Jean-Charles della Faille with, as very prominent attributes, the instruments on the table to his left. The learned divine, from a wealthy Antwerp merchant family, entered the Company of Jesus in 1613. At the highly-reputed Antwerp school he advanced his mathematical skills with two famous teachers and fellow-Jesuits, Franciscus Aguilonius and Gregorius a Sancto Vincentio, going on to teach the subject himself at Dôle , Leuven and Lier, until summoned in 1629 to lecture at Philippe IV's recently founded Collegium Imperiale in Madrid. His activities in Spain were not limited to theory and teaching and from 1637 he served the court as a cosmographer and a specialist in warfare. It was commonplace in the early 17th century for a mathematician to master also related, often practical disciplines such as surveying and astronomy, and the instruments with which he is portrayed can be used in all these areas.

Next to a celestial globe we recognize a Dutch circle, a quadrant and plumb line, a compass in his hand and some scientific writings. The sector is from the workshop of Antwerp instrument maker Michiel Coignet. Jean-Charles della Faille kept up a regular correspondence with his fellow-cosmographer at the Spanish court in Brussels, Michael Florentius van Langren. In his position as a military engineer, the Jesuit father travelled to regions in rebellion against the Spanish crown, among them Portugal, Naples and Catalonia, but never returned to his native Netherlands. We can thus assume that Van Dyck portrayed him shortly before his departure in 1629, probably as a commission by his family. This is also the date mentioned on the canvas, together with the age of 32. Although of a later hand, both data appear to be acceptable.

This lively portrait records the inquisitive look of the Jesuit, presented in three-quarter profile. Two engravings of this painting are also preserved, a 17th century one by Adriaan Lommelin and a 19th century one by François de Meersman. The latter print belonged to a series of Belgian mathematicians, which is surprising bearing in mind that in the 20th century della Faille's importance in scientific history was hardly known.

Family Portrait: 1618-20

The identity of the family is not known. Earlier the painting was supposed to be the family portrait of the painter Frans Snyders. However, Snyders had no children.

Thomas Killigrew and William, Lord Croft: 1638

Van Dyck's double portraits usually explore such themes as kinship or friendship, but the present painting depicts two figures united by grief. The circumstances in which the painting was undertaken and the elegiac mood created by the subtle monochromatic tones make this one of the most moving double portraits painted by Van Dyck. Thomas Killigrew (1612-83), a royalist poet, playwright and wit, is seated on the left looking out of the composition. The pose with the head supported by the hand is traditionally associated with melancholy.

This state of mind in a man who was only twenty-six years of age was induced by the recent death of his wife, Cecilia Crofts. She died (possibly from plague) on 1 January 1638 after two years of marriage. He wears his wife's wedding ring attached to his left wrist by a black band. A silver cross inscribed with her intertwined initials is attached to his other sleeve. He holds a piece of paper on which there are drawings, possibly made with a funerary monument in mind. The other figure has been variously identified, but the most satisfactory suggestion is that he is William, Lord Crofts (c.1611-77), Killigrew's brother-in-law, who suffered a double loss at the beginning of 1638, since another sister, Anne, Duchess of Cleveland, died shortly after Cecilia. The paper held by Crofts is blank, but clearly it formed the basis for discussion between the two sitters - a discussion presumably meant to console, but from which Killigrew is distracted by grief. The mood of the picture, therefore, unifies the composition on one level, but so do the contrasting poses, with one figure seen from the front and the other from the back with the face turned in profile. There is also an allegorical link provided by the broken column, a symbol both of mortality and of fortitude.

Killigrew's friendships with other poets are also significant for appreciating this portrait. Thomas Carew wrote a poem commemorating the marriage of Killigrew and Cecilia Crofts (29 June 1636), while Francis Quarles wrote an elegy on the deaths of the two sisters. By showing the two sitters in conversation Van Dyck is demonstrating the sense of loss while also suggesting a means for its cure, since, according to contemporary literary convention, words had the power to heal the troubled soul. At the same time, in pictorial terms the device of depicting figures in the act of talking was a way of evoking their actual presence more effectively. The thematic and psychological interactions that characterize this double portrait are a supreme demonstration of Van Dyck's abilities as a portrait painter.

Portrait of Joost de Hertoghe: 1635

The portraits of Joost de Hertoghe and his wife Anna van Craesbecke represent full-length marriage portraits. They were painted during van Dyck's stay in Brussels, the city where the knight Joost de Hertoghe, Lord of Franoy, had his residence.

Portrait of Anna van Craesbecke: 1635

The portraits of Joost de Hertoghe and his wife Anna van Craesbecke represent full-length marriage portraits. They were painted during van Dyck's stay in Brussels, the city where the knight Joost de Hertoghe, Lord of Franoy, had his residence.

Portrait of Justus van Meerstraeten: 1634-35

In 1634-35 Anthony van Dyck undertook several journeys on the continent, being one of the portrait painters most in demand. He travelled also to Brussels, where the double portraits of Justus van Meerstraeten and his wife Isabella van Assche were painted. As syndic, Meerstraeten was the holder of the city's highest office, and this is how the artist has portrayed him.

Justus van Meerstraeten is clearly indoors, while in the companion piece his wife Isabella van Assche is shown in something like a grotto, opening on the right into a wooded landscape.

Portrait of Isabella van Assche: 1634-35

This is the companionpiece of the portrait of Justus van Meerstraeten, husband of the sitter.

Portrait of the Artist Marten Pepijn

Rubens, Van Dyck and Jordaens, often named in the same breath, are the most prominent artists of the Flemish Baroque. The trio dominated artistic life in the Southern Netherlands throughout the 17th century. All three made an enormous contribution to the fame of the city of Antwerp, but it is Rubens who bears the greatest authority, because he was the most versatile and talented.

The youngest of the three great masters was Anthony van Dyck. He worked with Rubens for a time in his youth, after which he spent most of his career in England and Italy. He was even more admired in England than in his own country, and he had a significant influence upon English painting. Van Dyck's oeuvre, less varied than that of Rubens, consists mainly of brilliant portraits. His sensitive personality and restless temperament were brought to bear in penetrating psychological studies of members of leading families, the nobility and royalty. His sober Portrait of Marten Pepijn shows the artist as an energetic man of fifty-eight years, depicted in a black jerkin with a refined pleated collar.

Portrait of Porzia Imperiale and Her Daughter: ca 1628

During his trip to Italy and in particular when he was living in Genoa, Anthony van Dyck painted many portraits of members of patrician families. These were strongly influenced by those that Peter Paul Rubens had produced for the same families almost two decades earlier. From these Van Dyck borrowed the structures and the chromatic oppositions between the dark, court clothing and the bright ruffs, embroideries and jewels. The painting in the Brussels museum is a good example of this type of official representation.

Porzia Imperiale and her daughter Maria Francesca belonged to a family of Genoese bankers. On 5 August 1610 the mother married Bartolomeo Imperiale, probably a distant cousin. Born in around 1586, she must have been between 35 and 40 when Anthony van Dyck stayed in Genoa. Maria Francesca's date of birth is not known, but the inscription Virtute Gaudet (she rejoices in virtue) on the virginal, exalting the young girl's honor, shows that she was of marriageable age. Women occupied a special place in the Republic of Genoa. It is therefore not surprising to see them associated with Virtue, a quality with heroic connotations that is more generally ascribed to men.

Porzia Imperiale, seated here, is dressed in a black gown, its severity softened by an imposing ruff, a double chain, engraved buttons and lace-edged cuffs. In her left hand she carries a closed fan, whilst her right hand rests on the arm of the chair. Her daughter wears a light-colored gown with silvery reflections, decorated with gilded braid and a ruff, its moiré reflections very finely balancing the dark mass of her mother's gown. Porzia Imperiale's determined face contrasts with Maria Francesca's gentle and innocent looks. The background architectural details and the heavy red drapery confer a monumental aspect to the painting, further accentuated by the way in which the figures literally dominate the spectator, who views them from a low-angle position. The subtlety with which Van Dyck renders the different dark nuances is proof of an uncommon skill.

Double Portrait of the Painter Frans Snyders and his Wife: ca 1621

Anthony van Dyck was not only celebrated throughout Europe for his portraits of persons of rank, but was also highly regarded by his colleagues. Evidence of this are the portraits commissioned from him by artists, like this double portrait of Frans Snyders, a painter of animals and still-lifes, and his wife Margaretha de Vos.

The depiction of both spouses on a single panel makes it possible to portray a more intimate relationship, and this was the format that Anthony van Dyck tended to prefer, especially for his fellow artists. The joined hands, which originally stood for the promise of marriage, are here a sign of marital fidelity and mutual affection.

Lord John and Lord Bernard Stuart: ca 1638

Early in 1639 the two Stuart brothers, cousins of King Charles I and younger sons of the third Duke of Lennox, set off on a three-year tour of the Continent. They must have posed for Van Dyck just before their departure. Since his arrival at the court, the artist had developed a new portrait type: the double portrait recording friendship, often, but not necessarily, between relatives. The two brothers are shown as if poised on the point of departure, waiting perhaps for servants to bring up their carriage. Both were to die a few years later in the Civil War, and hindsight gives the image an added valedictory poignancy.

Van Dyck's compositional skill is surpassed only by his matchless ability to depict satin, lace and meltingly-soft kid leather. But these carefully described effects are somehow not local: the whole surface of the canvas is brought alive with a flickering touch. The costumes, so fashionably similar, are beautifully contrasted - receding warm gold and brown on Lord John, cooler and advancing silver and blue on Lord Bernard - so that the two brothers, complementing each other in apparel, seem to form one shimmering, indivisible whole.

An Apostle with Folded Hands: 1618-20

Some of Van Dyck's Apostles were painted for cycles along Spanish lines. They suggest spiritual self-portraits as defined by their subjects. These busts share an informal authenticity and lack of academic decorum.

An Apostle: ca 1618

Some of Van Dyck's Apostles were painted for cycles along Spanish lines. They suggest spiritual self-portraits as defined by their subjects. These busts share an informal authenticity and lack of academic decorum.

The Brazen Serpent: 1618-20

The authenticity of this painting is doubtful. It bears an inscription: P.P. Rubens fecit".

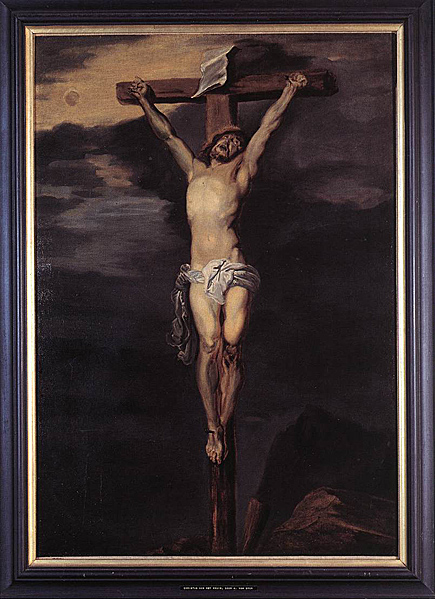

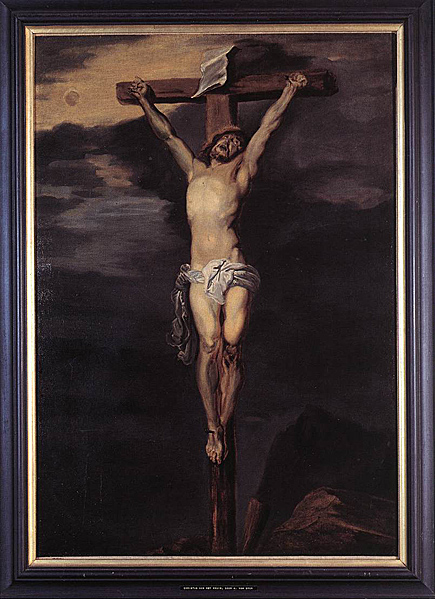

Christ on the Cross

The Capture of Christ: 1618-20

This painting belongs to the Italian period of the painter.

Crowning with Thorns: 1618-20

The contrast between the serenity of Christ and the villainy of his captors is vigorously conveyed in this early work by Van Dyck. The composition, as so often, is based on a prototype by Titian, of whom Van Dyck was a passionate admirer. But the influence of Rubens is also crucial, and the presentation is typically baroque: the viewer is forced into the role of a close but helpless witness of the violence enacted. The effect is reinforced by Van Dyck's textures - for instance the exposed and brilliant chest of Christ against the gleaming precision of the axe above or the fluid musculature of the tormentor beside it.

Deposition: 1634

Emperor Theodosius Forbidden by Saint Ambrose To Enter Milan Cathedral: 1619-20

Saint Ambrose, the fearsome fourth-century Archbishop of Milan, is said to have refused Theodosius entry into the cathedral because of the emperor's vengeful massacre of the inhabitants of Thessalonica. Theodosius impetuously thrusts his face upwards towards the saint. Ambrose's sturdy vigor has been transferred to the crosier as if the priest who holds it for the saint were ready to bring it crashing down on the emperor.

This painting is a free copy by Van Dyck of a large painting now in Vienna executed in Rubens's studio. The finely drawn profile to the right of Saint Ambrose has been identified as a portrait of Nicolaas Rockocx, the friend for whom Rubens painted Samson and Delilah.

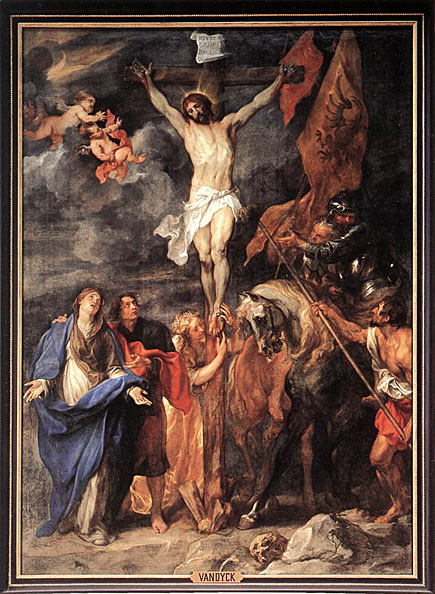

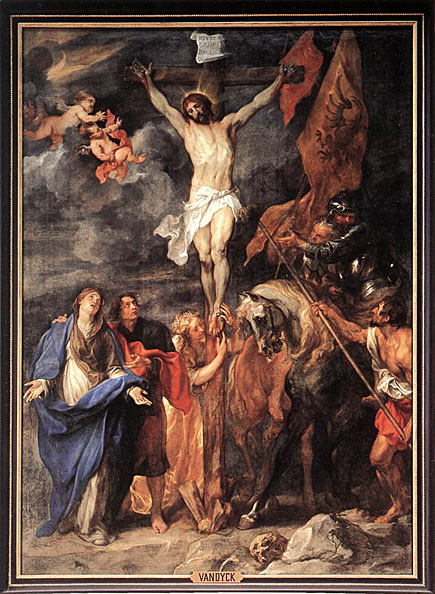

Golgotha: 1630

Blessed Joseph Hermann: 1629

Joseph Hermann lived in Cologne in the 13th century. He was a monk to whom the Virgin Mary appeared several times in his visions.

Jupiter and Antiope

Anthony van Dyck was the third leading member of the Antwerp School (beside Rubens and Jordaens). This youthful work shows Jupiter in the guise of a satyr, accompanied by his eagle attribute, discovering the sleeping nymph Antiope. The work, of which several versions are known, shows similarities with the style of Rubens and Jordaens, with both of whom the young Van Dyck collaborated.

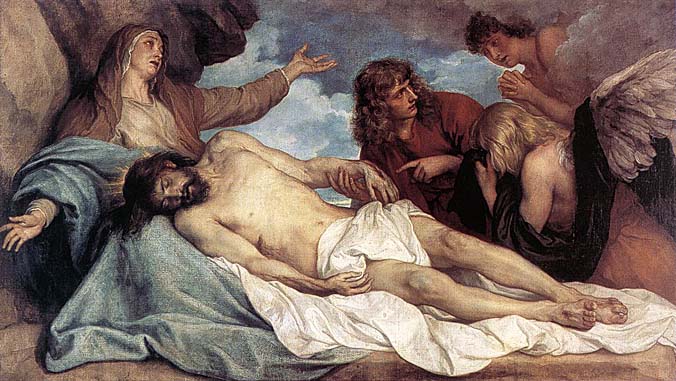

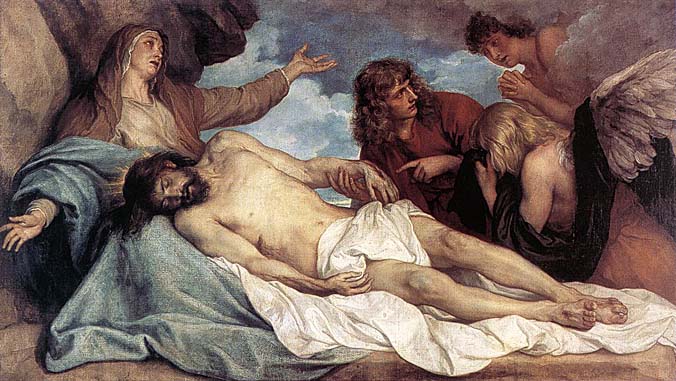

The Lamentation of Christ

In addition to portraits, Van Dyck also painted grandiose religious and mythological compositions. His Lamentation of Christ, executed as a commission from an Italian abbot, is imbued with something of a theatrical character by Mary's expansive gestures. Van Dyck shows his sense of the monumental in this biblical theme in which the intimate emotion of the depicted characters enjoys the viewer's fullest attention.

Pentecost: 1618-20

This painting belongs to a series of five works (two destroyed in World War II) painted in Rubens's studio for a Bridgettine Cloister at Hoboken.

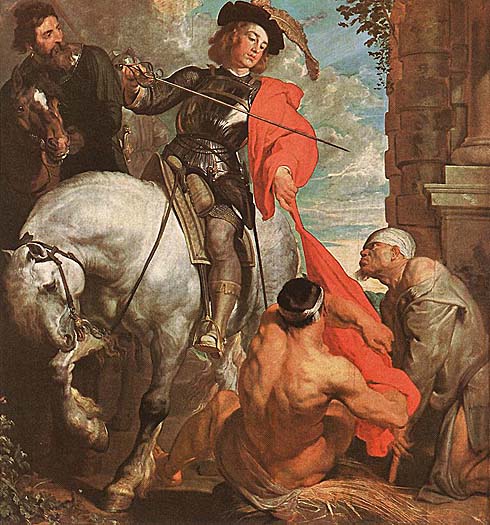

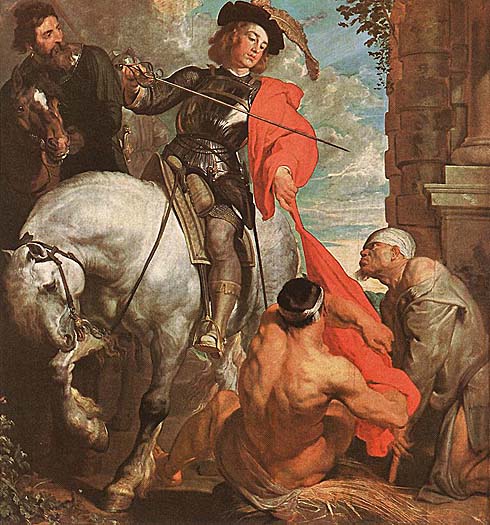

Saint Martin Dividing his Cloak: ca 1618

Saint Martin was born in Pannonia (now Hungary), joined the Roman army and served in Italy and then in Gaul, where the famous episode of his 'charity' took place. One winter day in 337 he met a beggar shivering with cold. Martin cut his cloak in two and handed one to the pauper. At night he saw a dream, in which Christ, wearing the half of his cloak came and thanked him. Martin left the Roman army and converted to Christianity. He founded a monastery of Liguge in Poitou, in 370 he was elected bishop of Tours. Until his death in 397 he fulfilled his Episcopal functions, worked as a missionary throughout western France. He founded the monastery of Marmoutier, which became one of the largest abbeys in the west. His religious work gave him the name Apostle of the Gauls.

Saint Martin is a patron saint of soldiers and knights, as well as of drapers, furriers and tailors. He is also one of the patrons of French monarchy.

Saint George and the Dragon

Studies of a Man's Head

The preparatory work for large paintings was not usually confined to one or more oil sketches, but generally included detail studies as well. The Studies of a Man's Head painted from life by Van Dyck are an excellent example of this.

Susanna and the Elders: 1621-22

Susanna a chaste wife of a wealthy man, Joachim, was taking a bath in her garden, when two lusty elders, judges by profession, saw her and demanded her favors. She cried for help, but the elders raised the alarm themselves and accused her of infidelity: they said they saw her with a young man under a tree. She was sentenced to death, but Saint Daniel, then a young boy, stopped the executors and asked the elders to be interrogated separately; they were asked to show the tree under which they had spied Susanna with her lover. The elders showed different trees, Susanna was justified, and her accusers were stoned.

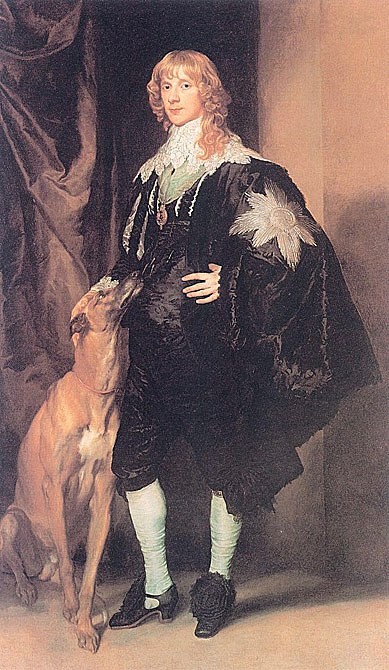

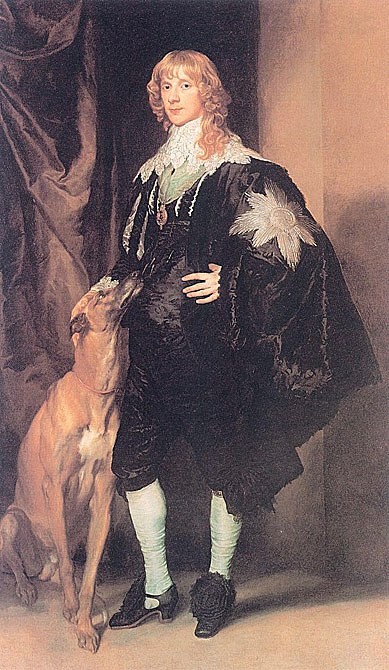

James Stuart, Duke of Lennox and Richmond: 1633

James Stuart, Fourth Duke of Lennox, was made First Duke of Richmond by his cousin, Charles I, in 1641. In 1637, he married Mary Villiers, daughter of the king's favorite, the Duke of Buckingham. It has been suggested plausibly that van Dyck painted this canvas in London just before or after his stay in the Netherlands (early 1634 to early 1635) in order to celebrate Stuart's investiture into the Order of the Garter in November 1633. The Order's insignia are conspicuously displayed amidst van Dyck's masterful description of luxurious materials: the silver star on the mantle; the red and gold Jewel, or lesser George, on the green ribbon (to which the greyhound seems to refer); and the garter itself, behind the bow at the duke's left knee. The composition recalls Titian's famous Charles V with a Hound (Museo del Prado, Madrid), which was then in Charles I's collection.

Philip, Fourth Lord Wharton: 1632

Philip Wharton, 4th Baron Wharton (1613 - February 4, 1696) was an English peer.

A Parliamentarian during the English Civil War, he served in various offices including soldier, politician and diplomat. He was appointed as the Lord Lieutenant of Buckinghamshire by Parliament in July 1642. He was a Puritan and a favorite of Oliver Cromwell, which is why, from 1660 onwards he often ran into difficulty with the Crown. In 1676 he was imprisoned in the Tower of London and later (in 1685) fled the country when King James II came to the throne.

He spent time while abroad in the Court of the Prince of Orange and subsequently his family line was back in Royal favor when the latter came to the throne of England in 1688.

He had two daughters by his first lady Elizabeth. Their names were Philadelphia and Elizabeth. Anthony Van Dyck completed a painting of the two in 1640 called "Philadelphia and Elizabeth Whartons".

Portrait of Philadelphia and Elisabeth Cary: 1635-38

Portrait of a Girl as Erminia Accompanied by Cupid: 1638

Van Dyck showed himself capable of creating brilliantly accurate likenesses of his subjects, while he also developed a repertoire of portrait types that served him well in his later work at the court of Charles I of England. Back in Antwerp from 1627 to 1632, van Dyck worked as a portraitist and a painter of church pictures. In 1632 he settled in London as chief court painter to King Charles I, who knighted him shortly after his arrival. Van Dyck painted most of the English aristocracy of the time, and his style became lighter and more luminous, with thinner paint and more sparkling highlights in gold and silver. At the same time, his portraits occasionally showed a certain hastiness or superficiality as he hurried to satisfy his flood of commissions. In 1635 van Dyck painted his masterpiece, Charles I in Hunting Dress (Louvre, Paris), a standing figure emphasizing the haughty grace of the monarch. Van Dyck was one of the most influential 17th-century painters. He set a new style for Flemish art and founded the English school of painting; the portraitists Sir Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough of that school were his artistic heirs. He died in London on December 9, 1641.

Portrait of Anne Carr, Countess of Bedford

Margaret Lemon

The informal drawing, in black and white chalks, is very unusual in his work, but also highly personal. It is of particular interest to art historians since so little biographical information has survived of Van Dyck - there are no journals or diaries, and very few letters.

It portrays his mistress, Margaret Lemon, a courtesan noted for her beauty, her jealousy, and her vile temper. She disliked the amount of time he spent painting ravishing young women. Her jealousy was justified. He left her and married the much younger Mary Ruthven in 1639.

Portrait of Maria Lugia de Tassis: 1629

Saint John the Baptist in the Wilderness

Samson and Delilah: ca 1630

GenoannHauteur from the Lomelli Family: 1623

Portrait of Henri II de Lorraine, Duc de Guise: 1634

Henri II de Lorraine, Duc de Guise (1614-1684). This portrait was painted in Brussels during Van Dyck's visit to the southern Netherlands in 1633-1634. Henri II had just fled from the French Duchy of Lorraine after the failure of his intrigue against Louis XIII's prime minister.

Source: Web Gallery of Art

Source: Art Renewal Center

This page is the work of Senex Magister

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.