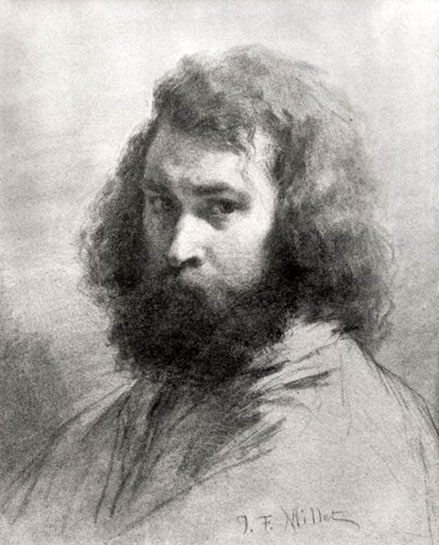

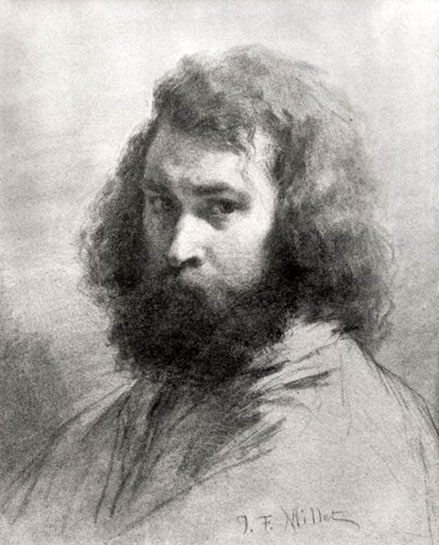

Self Portrait: ca 1845-46

Portrait of Baron Antoine Jean Gros Aged 20

by Francois Pascal Simon Baron Gerard

Madame J. F. Millet (Pauline-Virginie Ono): 1841

_1841.jpg)

Pauline Ono in Blue: 1841-42

Look at "Portrait of Pauline-Virginie Ono". Before painting peasants, he made his living by drawing portraits. This portrait is Millet's first wife who was sickly and died in her youth age. As you can tell by this painting, he seems not to be poor at drawing face. Features on Millet's peasant paintings don't have any specific model. You can find this feature also in other genre of Millet's paintings.

Portrait of Pauline Ono (d 1844)

.jpg)

19th Century French Young Woman (Catherine Lemaire)

.jpg)

Jean-François Millet (French, 1814-1875): Catherine Lemaire as a Young woman. Pencil on bluish green tinted paper. Long repaired tear snaking its way up from the lower left to the left shoulder. This work is strongly reminiscent of Millet's portrait of his wife in 1848-49 in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. The subject here is several years younger and is seen before she began giving birth to Millet's children. It seems to be one of the most tender, wistful, and lovely drawings of its kind.

Catherine Lemaire: 1848

Oedipus Taken Down from the Tree: 1847

This work from his Parisian period, inspired by the ancient Greek legend, is one of Millet's rare mythological subjects. Shepherds rescue the infant Oedipus, strung up in a tree and left to die because his father, Laius, believes the prediction that his son will kill him. Beneath the surface lies a painting of Saint Jerome, rejected by the Paris Salon the previous year.

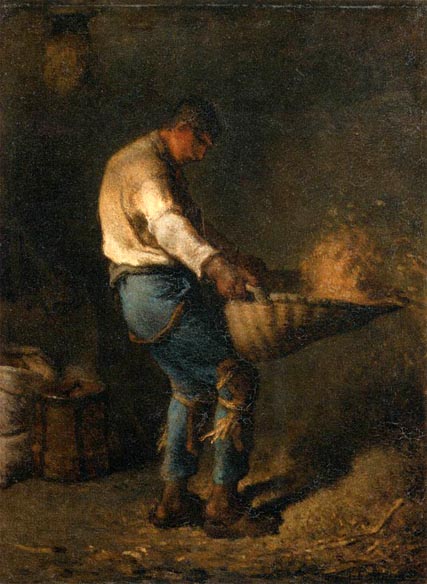

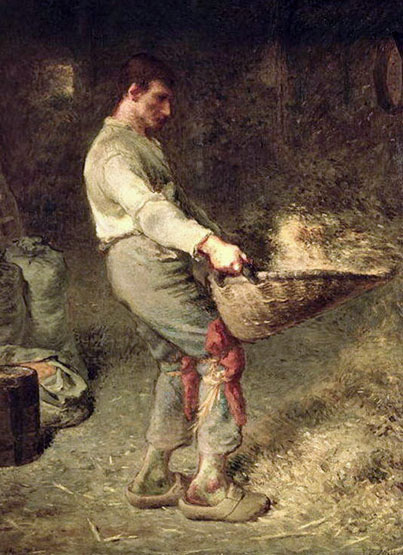

The Winnower: 1848

Millet's early works were modeled on eighteenth-century pastorals, but during the 1840's the influence of Daumier encouraged him to paint in a more vigorous and sober style. 'His Winnower of 1848' set the seal on this new direction.

The painting was exhibited at the Salon of 1848.

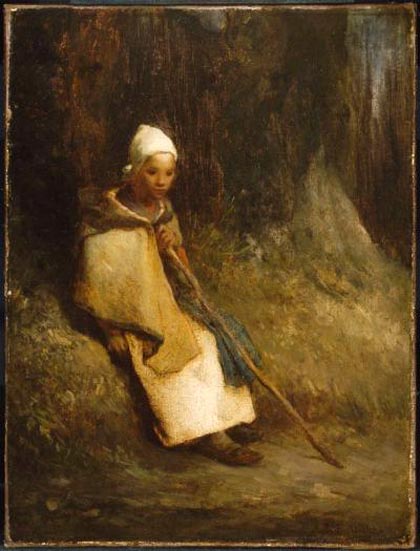

Shepherdess Sitting at the Edge of the Forest: ca 1848-49

The Hay Trussers: 1850-51

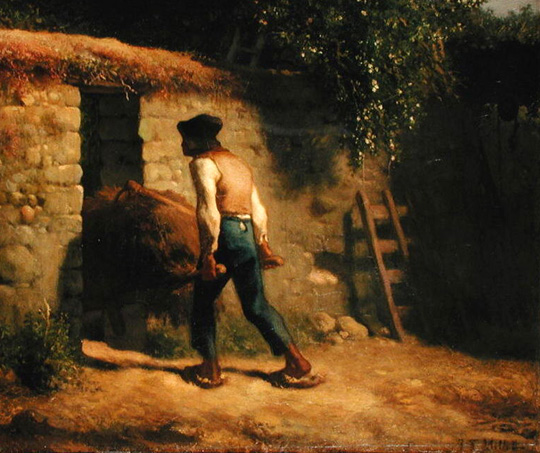

After 1848, Millet devoted himself to genre scenes glorifying the family life of the hard-working farmer population, whom he observed in the region of Barbizon. The thematic simplicity of these pictures does not belong to the anecdotal vein of genre painting. Millet paints the grandeur and dignity of peasants with thick, expressive and liberal brushwork.

The painting was exhibited at the Salon of 1850.

The Sower

The Sower: 1847-48

Millet's 1850 piece "The Sower", which has come to be associated with the Social Realist movement, shows a peasant man striding through a plot of freshly tilled soil as he sows his crops. The sun shines in the top half of the painting just over the horizon to show that the peasant has risen at the crack of dawn in order to accomplish the day's work that lies ahead.

The painting is characterized as a Social Realist work because of its focus and subject matter, and additionally due to the manner in which the work is portrayed. Millet breaks from the traditional academic route with "The Sower" and it shows in his dark and muddy earth tones. Rather than idealizing the peasant man or ignoring him entirely, Millet portrays the peasant as a stocky, well-built young man wearing simple, practical peasant clothing.

An impasto brush stroke gives "The Sower" an aura of liberation from academic traditions. Millet balances the earthy lower portion of "The Sower" with a sunset over the horizon in the top of the painting, giving the work the simplicity of a peasant's day. The peasant portrayed has his face hidden by the front of his hat, and is presumably looking off into the distance, at the work that is left to be done in front of him.

All of these elements could lead the viewer to the conclusion that Millet's painting is simply intended to idealize the peasant and peasant life in general. One might even call this a pastoral work, focusing on idealized life out in nature. Why then did this work create controversy when it was shown for the first time in France?

One reason could be that Millet was associated with the more open and overtly Social Realist painter Gustave Courbet. Since Courbet also liked to portray members of the peasantry in dark and earthy tones, Millet's "The Sower" may have become associated with Courbet's works, (most notably "The Burial at Onans"), both for its subject matter, that is, the peasantry and the dark and naturalistic manners in which both artists presented their works.

When "The Sower" is looked at in light of its Social Realist associations, a whole new realm of icons and meanings can be grasped. The Sower himself or the peasant can be viewed as a sewer of social justice, a representative of the lower classes fighting for social mobility by sowing the seeds of protest and dissent. A bright sun is rising behind the peasant man indicating that the sewer has the forces of social justice on his side. The sun rise can also be interpreted as a symbol of change, in the Social Realist sense; this would mark the change from the bourgeoisie middle class dominance of the capital industrial era in France to one of socialist enlightenment.

Under this ideological lenses, it becomes apparent why "The Sower" created controversy in a France that was rapidly industrializing. In this France peasants or working class members of society were essential to do what needed to be done on the assembly lines, in the fields, in the textile mills, and so on. Up until this point art had focused on the upper classes, or idealized the peasant, making him a cheerful and productive member of society.

The Gleaners

(a black chalk drawing for summer)

chalk_drawing_for_summer.jpg)

Gleaners, or the women who scavenge for the stray ears of corn left by the harvesters, had appeared in several of Millet's drawings, but the first oil painting on the theme was one of a set of four representing the seasons. The painting, Summer, The Gleaners (1853, Private Collection) has an identical composition to The British Museum's drawing, shown here. This drawing may have immediately preceded the painting, but more likely was drawn from it, as Millet frequently repeated and recorded his favorite motifs. Millet was an important influence on later artists, including Van Gogh, who made copies of several of Millet's works.

The Angelus: 1857-59

The Angelus (Latin for Angel) is a Christian devotion in memory of the Incarnation. The name Angelus is derived from the opening words: Angelus Domini nuntiavit Mariæ and is practiced by reciting as versicle and response three Biblical verses describing the mystery; alternating with the salutation "Hail Mary!" The devotion was traditionally recited in Roman Catholic churches, convents, and monasteries three times daily: 6:00 am, noon, and 6:00 pm (many churches still follow the devotion, and some practice it at home). The devotion is also used by some Anglican and Lutheran churches. The Angelus is usually accompanied by the ringing of the Angelus bell, which is to spread good-will to everyone on Earth. The angel referred to in the prayer is the Angel Gabriel, a messenger of God who revealed to Mary that she would conceive a child to be born the Son of God. (Luke 1:26-38).

Jean François Millet's "The Angelus"

Millet's work is distinguished by an absolute truthfulness to Nature which was the guiding principle of his life. He saw the peasant bent at his work in the fields, and he pictured him in all his gaunt poverty and weariness, while he invested him, by his inspired vision, with the symbolic dignity of labor. Thus, in painting life, Millet reveals the sublime in the commonplace, the promise hidden in the pain, and the mercy that hovers over sorrow.

"The Angelus" completes a series of three pictures by Millet which are considered his masterpieces. "The Sowers" typifies the laborer going forth bearing good seed with him "The Gleaners" shows the end of the harvest which has supplied the people's wants and left something over for the needy. "The Angelus" depicts the laborers' thanks for the gift of plenty.

The last picture is the most popular of all the works of this artist, and it expresses in full measure the simplicity and devoutness of his nature. His wish was to make the spectator realize the vesper hour, when the soft chimes call the toiler to thankful rest. The man and the woman have worked well, as their full sacks bear witness, and they are bending their heads in gratitude to their Creator for His gifts. On a small canvas, twenty-five inches long and twenty-one inches high, the painter has created a scene that is at once a prayer and an inspiration, which will hold its strong appeal as long as the colors last.

Harvesters Resting

(Ruth and Boaz)

.jpg)

GALLERY VIEW; WHY WE NOW SEE MILLET DIFERENTLY - New York Times

The Gleaners: 1857

The Gleaners (Des glaneuses) is an oil painting by Jean-François Millet composed in 1857. It depicts three peasant women gleaning a field of stray grains of wheat after the harvest. The painting is famous for monumentalizing what were then the lowest ranks of rural society. The painting was received poorly by the French upper class.

Potato Planters: ca 1861

Spring: 1868-73

This work, commissioned at the end of Millet' career, forms part of an uncompleted series of pictures depicting the four seasons. It is a classic theme - explored by Poussin, among others -, though Millet handles it with a deliberately expressive touch, representing nature in a manner typical of the Barbizon school, of which he was a leading artist. The dialogue between man, here reduced to a minute figure, and the image of nature modeled by the artist, is both lyrical and poetic, thanks to the striking contrasts of light and darkness in the stormy sky.

Buckwheat Harvest: Summer

In 1868, the artist was commissioned by his patron, Félix Hartmann, for painting a series representing the four seasons. The Spring in the Musée d'Orsay, was the first of the series, the Summer (Buckwheat Harvest) is in Boston, the Autumn (Haystacks) in New York, and the Winter in Philadelphia.

Haystacks Autumn: ca 1874

In 1868, Millet received a commission from Frédéric Hartmann, an Alsatian industrialist and patron of Millet's friend the artist Théodore Rousseau, to paint a series representing the Four Seasons. Millet worked on the commission intermittently for the next seven years.

In Autumn, with the harvest finished, the gleaners have departed and the sheep are left to graze. Beyond the haystacks lie the plain of Chailly and the rooftops of Barbizon. The work has the loose, sketch like execution characteristic of Millet's late style: patches of the dark lilac-pink ground color are deliberately exposed, and the under drawing is visible, particularly in the outlines of the haystacks and the sheep.

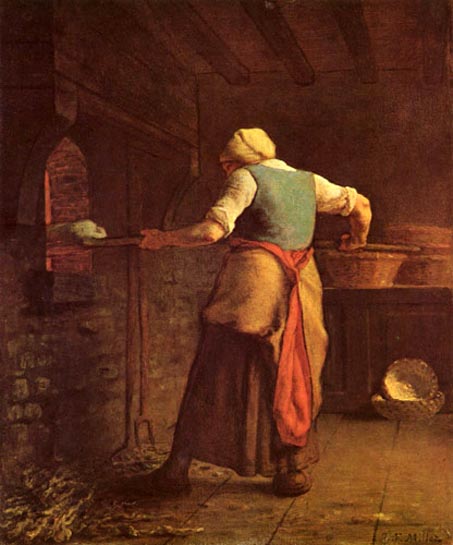

Woman Baking Bread: 1854

Millet's modest background had a great influence on the subject matter of his works. "I was born as a peasant and shall die as a peasant", Millet once said (although, after achieving success, Millet did learn to appreciate a more comfortable life). Millet's works are a nostalgic tribute to farmers and laborers. He felt great compassion for people who worked the soil with their own hands--it is here that Van Gogh and Millet connect.

Van Gogh began doing studies after Millet works as early as 1880. These early studies helped Van Gogh to learn the disciplines necessary in order to paint. Van Gogh felt that no one could offer him a finer example:

"Millet is father Millet . . . counselor and mentor in everything for young artists," Vincent wrote to Theo in 1885.

Pastures in Normandy

Man with a Hoe: 1860-62

The Man with the Hoe

by Edwin Markham

Bowed by the weight of centuries he leans

Upon his hoe and gazes on the ground,

The emptiness of ages in his face,

And on his back the burden of the world.

Who made him dead to rapture and despair,

A thing that grieves not and that never hopes.

Stolid and stunned, a brother to the ox?

Who loosened and let down this brutal jaw?

Whose was the hand that slanted back this brow?

Whose breath blew out the light within this brain?

Is this the Thing the Lord God made and gave

To have dominion over sea and land;

To trace the stars and search the heavens for power;

To feel the passion of Eternity?

Is this the Dream He dreamed who shaped the suns

And marked their ways upon the ancient deep?

Down all the stretch of Hell to its last gulf

There is no shape more terrible than this -

More tongued with censure of the world's blind greed -

More filled with signs and portents for the soul -

More fraught with menace to the universe.

What gulfs between him and the seraphim!

Slave of the wheel of labor, what to him

Are Plato and the swing of Pleiades?

What the long reaches of the peaks of song,

The rift of dawn, the reddening of the rose?

Through this dread shape the suffering ages look;

Time's tragedy is in the aching stoop;

Through this dread shape humanity betrayed,

Plundered, profaned, and disinherited,

Cries protest to the Powers that made the world.

A protest that is also a prophecy.

O masters, lords and rulers in all lands,

Is this the handiwork you give to God,

This monstrous thing distorted and soul-quenched?

How will you ever straighten up this shape;

Touch it again with immortality;

Give back the upward looking and the light;

Rebuild in it the music and the dream,

Make right the immemorial infamies,

Perfidious wrongs, immedicable woes?

O masters, lords and rulers in all lands

How will the Future reckon with this Man?

How answer his brute question in that hour

When whirlwinds of rebellion shake all shores?

How will it be with kingdoms and with kings -

With those who shaped him to the thing he is -

When this dumb Terror shall rise to judge the world.

After the silence of the centuries?

Various works of Jean François Millet

A Farmer's Wife Sweeping: 1867

A Shepherdess and her Flock

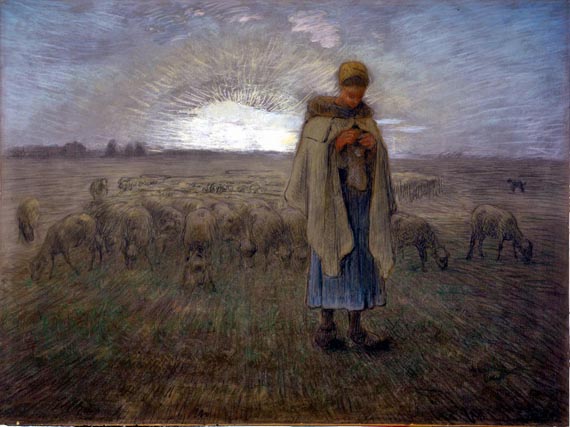

Shepherdess with her Flock: 1864

Calm, serenity and harmony triumph in this painting. Wearing a woolen cape and a red hood, the young shepherdess (perhaps the painter's own daughter) is standing in front of her flock. She is knitting, looking down at her work. In a monotonous landscape stretching, unbroken, to the horizon, she is alone with her animals. The flock forms a patch of undulating light, reflecting the rays of the setting sun. The scene is an admirable mixture of accuracy and melancholy. Millet observed the minutest details, like the small flowers in the foreground. He makes use of the perfect harmony of blues, reds and golds.

Since 1862, Millet had been thinking about a picture of a shepherdess guarding her sheep. He didn't tell anyone about it, but Alfred Sensier recounts that the theme "had taken hold of him".

On completion, the work was presented at the 1864 Salon where it was warmly received. "An exquisite painting" for some, "a masterpiece" for others, this most peaceful of scenes captivated all those who preferred images of idyllic country scenes to those of peasant squalor. Bergère avec son troupeau was even awarded a medal, and the State, which until then had shown little interest, was eager to acquire it. However, the work had already been promised to the collector Paul Tesse. Like a number of other paintings by Millet, this one finally entered the national collections in 1909, thanks to a bequest by Alfred Chauchard, the director of the Grands Magasins du Louvre.

Shepherdess

A Winnower: 1866-68

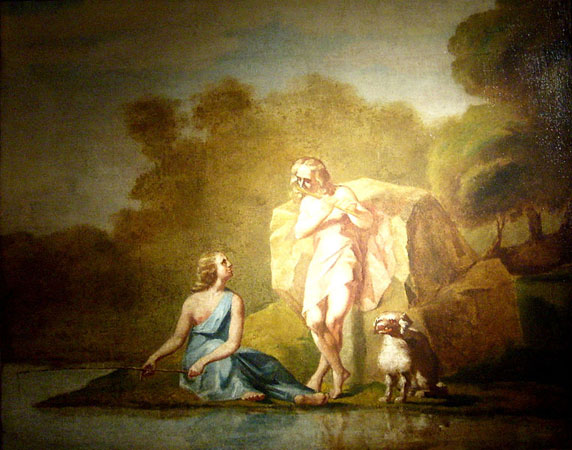

Arcas and Callisto

Callisto was the favorite companion of the goddess Diana. She accompanied Diana on the hunt and attended her at her bath after the hunt. One day the god Jupiter caught a glimpse of the beautiful Callisto and fell in love with her. Knowing that Diana had warned Callisto of the deceitful ways of men and gods, Jupiter assumed the guise of Diana.

In this disguise, Jupiter seduced the beautiful Callisto. Callisto succumbed to the beautiful seductive words of Jupiter, and in Jupiter's loving embrace, she conceived a child. When Jupiter's wife Juno saw this evidence of Jupiter's infidelity she became enraged, and changed Callisto into a bear.

Callisto was ashamed and afraid, and fled into the woods, not to see her son for many years. One day, when Arcas was a young man, he decided to go hunting and went into the woods where his mother Callisto, the bear, resided. Callisto saw her son, whom she had not seen for many years. Forgetting she was a bear, she rushed forward to embrace him. Arcas only saw a bear rushing down on him. He lifted his bow and let fly an arrow to the mark.

At the last moment Jupiter intervened and cast Callisto and her son into the heavens as the constellations Ursa Major, the Great Bear, and Bootes, the Bear Warden. Arcas is always standing next to his mother. Arcas became the ancestor of the Arcadian race in the Peloponnesus.

Autumn Landscape with a Flock of Turkeys

In a letter of February 18, 1873, to his patron Frédéric Hartmann, Millet wrote that he had nearly completed this painting and hoped to deliver it to his dealer Durand-Ruel within the week: "It is a hillock, with a single tree almost bare of leaves, and which I have tried to place rather far back in the picture. The figures are a woman seen from behind and a few turkeys. I have also tried to indicate the village in the background on a lower plane." The setting is near Barbizon, where Millet lived for most of his career; the distinctive tower of the neighboring hamlet of Chailly-en-Bière is visible in the distance.

Bergers d'Arcadie

Arcadia is an actual region of Greece, a series of valleys surrounded by high mountains and therefore difficult of access. In very ancient times, the people of Arcadia were known to be rather primitive herdsmen of sheep, goats and bovines, rustic folk who led an unsophisticated yet happy life in the natural fertility of their valleys and foothills. Soon, however, their down-to-earth culture came to be closely associated with their traditional singing and pipe playing, an activity they used to pass the time as they herded their animals. Their native god was Pan, the inventor of the Pan pipes (seven reeds of unequal length held together by wax and string). The simple, readily accessible and moving music Pan and the Arcadian shepherds originated soon gained a wide appreciation all over the Greek world. This pastoral (in Latin "pastor" = shepherd) music began to inspire highly educated poets, who developed verses in which shepherds exchanged songs in a beautiful natural setting preserved pristine from any incursions from a dangerous "outside." In the third century BC, a Sicilian poet, Theocritus, created a literary genre called "bucolic poetry" (from the Greek "bukolos," a herdsman), poems called "Idylls" that used these exchanges of verses by fictional shepherds as a compositional strategy. Mainly, these idealized shepherds recounted their heterosexual or homosexual love affairs and praised the poetry they loved and the master singers they admired. Two centuries later, the greatest of Roman (and perhaps of European) poets, Virgil (70-19 BC), used Theocritus's Greek Idylls in order to create masterpieces of bucolic poetry, known as the "Eclogues" or "Bucolics." Unlike Theocritus, who had placed his shepherds in Sicily, Virgil locates them back in Arcadia, an Arcadia, however, which has features strikingly resembling those of Northern Italy, where Virgil was born. Just as their Theocritean counterparts, the inhabitants of Virgil's Arcadia sing about love and its poetry, but they also make several crucial references to the political situation of Virgil's turbulent times. Many subsequent readers have in fact insisted that the "Eclogues" are stuffed full of references to politics and politicians, such as Julius Caesar and Octavian (Augustus Caesar). Virgil's poetic superiority has insured that his "Eclogues" never remained unknown in all the subsequent centuries of European culture. They became especially popular and imitated in the Italian, Spanish, French and English Renaissances of the 14th to 17th centuries, a period in which a type of verse called Pastoral Poetry was much appreciated by the intellectual and cultural elite.

Millet's Bergers d'Arcadie was inspired by Nicolas Poussin's "The Arcadian Shepherds" or as "ET IN ARCADIA EGO" (1647).

ET IN ARCADIA EGO: 1647

by Nicolas Poussin

Parallel to the literary vogue of pastoral there existed in this period a rich pictorial tradition, paintings and prints representing shepherds and shepherdesses in a bucolic or idyllic setting of forests and hills. In the seventeenth century, the French painter Nicolas Poussin (1594-1665) used this pictorial tradition to paint one of his most famous canvasses, known as "The Arcadian Shepherds" or as "ET IN ARCADIA EGO" (1647). This painting represents four Arcadians, in a meditative and melancholy mood, symmetrically arranged on either side of a tomb. One of the shepherds kneels on the ground and reads the inscription on the tomb: ET IN ARCADIA EGO, which can be translated either as "And I [= death] too (am) in Arcadia" or as "I [= the person in the tomb] also used to live in Arcadia." The second shepherd seems to discuss the inscription with a lovely girl standing near him. The third shepherd stands pensively aside. From Poussin's painting, Arcadia now takes on the tinges of a melancholic contemplation about death itself, about the fact that our happiness in this world is very transitory and evanescent. Even when we feel that we have discovered a place where peace and gentle joy reign, we must remember that it will end, and that all will vanish.

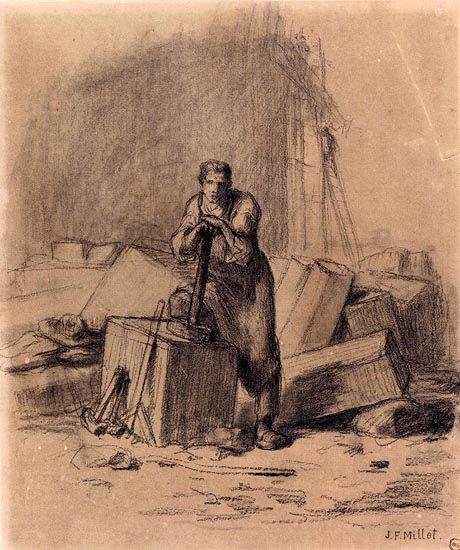

Bucheron preparant des Fagots

Capture of the Daughters of D. Boone and Callaway by the Indians

Churning Butter: 1866-68

Composition de F. Millet

Couseuse Endormie

Dandelions: 1867-68

Death and the Woodcutter

Where we were walking in the day's light, seeing

the flight of bones to the stars, the voyage of dead men,

those who go forth like dead leaves on the air

in the long journey, those who are swept

on the last current, the cold and shoreless ones,

who do not speak, do not answer, have no names,

nor are assembled again by any thought, but voyage

in the wide circle, the great circle

where we were talking, in the day's light, watching...

-from Time in the Rock; Conrad Aiken

Faggot Carriers

Farmer Inserting a Graft on a Tree: 1865

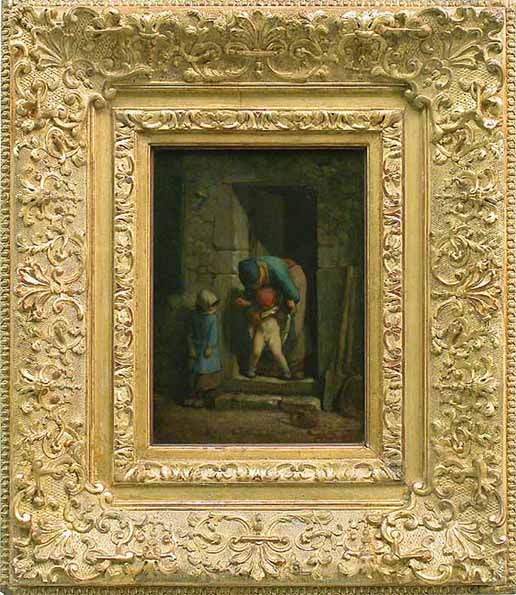

Feeding the Young: 1850

I once went to a hospital to make some tests, and had to wait in a line for an hour or so. I hadn't brought a book to occupy myself with, and, as it happens in such cases, entertained myself by looking around and stealthily examining the people waiting for their call. After a few minutes a couple with twin babies arrived, maybe one-year-olds, the mother was the patient, not the children. Behind them walked a fussing grandmother, constantly reminding the younger woman that it was time to "feed the young." Eventually the mother conceded the role of the nurturer and the feast began: the old lady took out a jar of commercial fruit mush and began forcing giant sized spoons into the babies' mouths, cheering if at least half of the mix ended up inside. The babies seemed unhappy… they were so plump as it is, and their cheeks were almost the size of their head! After less than two spoons they were turning their lips away, peeping. The children on the painting in front of us, however, don't seem to suffer from overfeeding.

Jean-Francois Millet | Art & Critique

Femme Etandant Sonligne

Fishermen: 1869-70

Flight into Egypt

Black and brown Conté crayon, with pen and black ink and traces of black pastel, over bands of variously colored gray washes, on cream wove paper, edge-mounted on laminated woodpile board.

Garden

Garden Scene

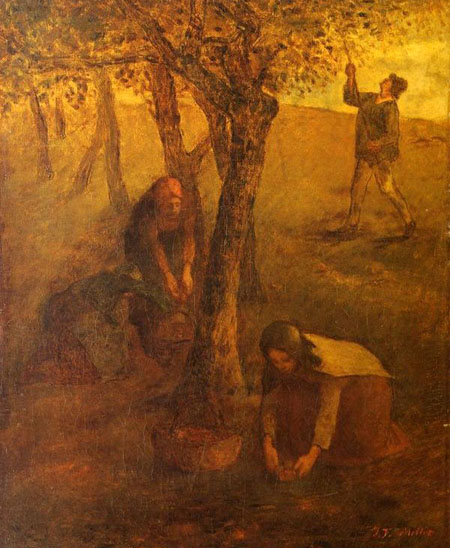

Gathering Apples

Grazing in the Vosges

Idyllic Landscape

In the Garden: 1862

La Ferme du Tourp

La femme au puits: ca 1866

La fileuse, chevriere auvergnate

L'Amour Vainqueur

Landscape

Landscape - Hillside in Gruchy, Normandy: 1869-70

Landscape with a Burning City

Landscape with Conopion Carrying the Ashes of Phocion

Landscape with Two Peasant Women

Collecting Brushwood

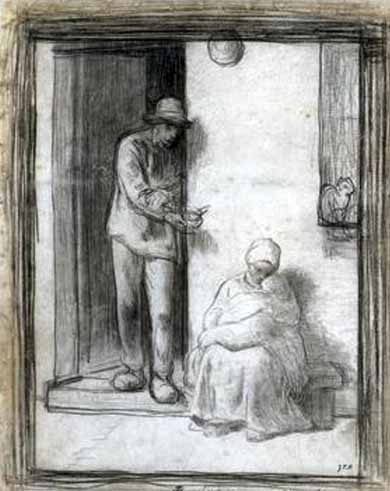

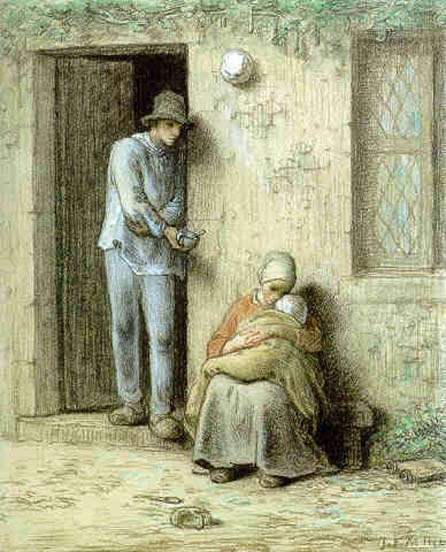

The Sick Child: 1858

Jean-François Millet's paintings of French rural life, especially those of peasants and farmers in their working environment, redefined the imagery of everyday life in the nineteenth century. Large-scale paintings such as 'The Gleaners', from 1857, presented the poorest of laborers with a dignity and nobility informed by classical traditions in French painting. At the same time he was working on major paintings for public exhibitions, Millet was also making smaller scale drawings. Since drawings were less expensive, there was a much larger market for this type of work, and Millet created finished sheets in both black crayon and pastel as he catered to this demand.

The work shown here is the first version of a theme the artist drew again in pastel in a more finished version (now lost). This crayon drawing shows, on the other hand, Millet's thinking process. We can see him working out the composition because several changes are visible, most notably in the bowl held by the father and the cat in the window. Though taken from everyday life, Millet's tender treatment of this family group recalls the biblical subject of the Holy Family.

Le Nourrisson or L'enfant Malade: 1858

Le rocher du Castel Vendon: 1848

Leconte de Lisle: 1840-41

Charles Marie René Leconte de Lisle was a French poet of the Parnassian Movement.

Leconte de Lisle was born on the island of Réunion. His father, an army surgeon, who brought him up with great severity, sent him to travel in the East Indies with a view to preparing him for a commercial life. After this voyage he went to Rennes to complete his education, studying especially Greek, Italian and history. He returned once or twice to Réunion, but in 1846 settled definitely in Paris. His first volume, La Venus de Milo, attracted to him a number of friends many of whom were passionately devoted to classical literature. In 1873 he was made assistant librarian at the Luxembourg Palace; in 1886 he was elected to the Académie française in succession to Victor Hugo. His Poèmes antiques appeared in 1852; Poèmes et poésies in 1854; Le Chemin de la croix in 1859; the Poèmes barbares, in their first form, in 1862; Les Érinnyes, a tragedy after the Greek model, in 1872; for which occasional music was provided by Jules Massenet; the Poèmes tragiques in 1884; L'Apollonide, another classical tragedy, in 1888; and two posthumous volumes, Derniers poèmes in 1899, and Premières poésies et lettres intimes in 1902. In addition to his original work in verse, he published a series of admirable prose translations of Theocritus, Homer, Hesiod, Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides, Horace. He died at Voisins, near Louveciennes, in the department Yvelines.

Liberty

Liberty relates to Jean-François Millet's entrance into the 1848 competition for an official painted figure representing the second French Republic. Millet did not win the competition and his painted Republic no longer exists, but this representation of a related concept-Liberty-was inspired by his contest participation. He also drew allegories of the other two fundamental concepts in French Republicanism: Equality and Fraternity.

Louise Antoinette Feuardent: 1841

Before Jean-François Millet achieved international success as a painter of peasant life, he earned his early living as a portraitist. Here, he depicted Louise-Antoinette Feuardent, the wife of his lifelong friend Félix-Bienaimé Feuardent, a clerk in the library at Cherbourg. In this portrait painted shortly after her marriage, Louise-Antoinette prominently displays her wedding band on her left hand. In a style reminiscent of seventeenth-century Dutch painters, Millet painted the modestly dressed sitter against a plain background using a limited palette. Louise-Antoinette looks out of the picture, her brown eyes calmly assessing the viewer. Through a tightly controlled composition and a careful balance of monochromatic tones, Millet captured Louise-Antoinette's self-containment, reserve, and poised composure.

Charles Feuardent

Louise Millet: ca 1863

Madame Eugene Felix Lecourtois

Madame Lefranc: ca 1841-42

Maternal Care: 1855-57

Monsieur Martin: 1840

Millet and the other members of the Realist movement were renowned for not only producing realistic images, but for typically injecting their pictures with political, spiritual, or social messages. Sensitive to the human psyche and the rise of the bourgeoisie, Millet used a simple, almost monochromatic background to focus attention on the face of Monsieur Martin, a middle-class veterinarian and meat inspector. Indeed, Martin's beard, hair style, clothing, even his common French name, and the fact that he could afford portraits of himself and his wife (now lost) convey that he belonged to the prosperous middle class.

This small portrait shows Millet's extraordinary skill as a painter. He depicted the highlights on Martin's face by adding patches of flat, unblended color, and some of the brushstrokes suggest the loose, quick movement of the artist's hands over the canvas.

Monsieur Frigot: 1841

Mother and Two Infants

Mountainous Landscape with a Citadel

Millet, who trained in France and travelled to England and Holland, studied the work of Poussin and made his reputation with austere classical landscapes in his manner. Some were engraved at an early date, providing virtually the only documentation for his work. The chronology of his paintings is difficult to establish. It depicts a richly varied, extensive landscape, with a solitary traveler on the left providing a romantic note.

Noonday Rest: 1886

Norman Milkmaid

Offering to Pan

Peasant Spreading Manure: 1854-55

Peasant with a Wheelbarrow: 1848

Millet moved from Paris to the nearby village of Barbizon in 1849 in search of rustic subject matter. The group of painters working in the countryside surrounding the Forest of Fontainebleau frequently painted out-of-doors in order to create fresh and accurate views of nature. While most of the Barbizon artists focused primarily on landscape, Millet also represented peasants. His works celebrate the nobility and dignity of people living close to the soil, symbols of the stability and continuity lacking in modern life.

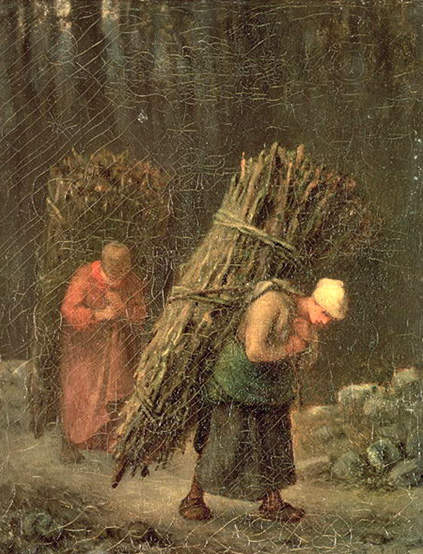

Peasant Women with Brushwood: ca 1858

Millet devoted his talent to the depiction of scenes from peasant life, and this is a typical example of his work. Being of peasant origin, Millet knew from his own experience the hard rural life. Here two women in rough homespun clothes and wooden clogs, bent beneath the weight of their load, are returning home in the twilight along a forest road. Their low-sunk heads and bent backs, the slow steps and hands tightly gripping the cord tell us of the utmost tension of their force. Using dark subdued coloring, the artist rendered the evening illumination which softens the outlines of the figures and makes them blend with the landscape.

Peasants Bringing Home a Calf Born in the Fields

In 'Peasants Bringing Home a Calf Born in the Fields', which was exhibited in the 1864 Salon in Paris, Jean-François Millet shows two peasant men carrying a newborn calf on a wooden support down a path toward a house where two young girls await their return. The strong, hardworking peasants, with torn clothes and humble living conditions, reflect Millet's commitment to the Realist aesthetic and his connection to the rural countryside. Born into a middle-class family in the small town of Cherbourg, France in 1814, Millet never lost touch with his rustic upbringing. While living in Barbizon, he became the central figure of an artist's colony dedicated to images of rural France.

Millet's Realist portrayal of the life of peasants was not well received by French critics of his day. Writer Ernest Chesneau described the figures in the painting as "types of cretins from the countryside." Some critics saw a resemblance to biblical scenes, such as the Nativity or a procession carrying the Ark of the Covenant, and the alleged incongruity of an elevated theme illustrated with lowly figures angered audiences. Not everyone was disturbed by Millet's subjects and style, however. Vincent van Gogh was one of numerous 19th-century painters and sculptors who admired Millet's empathetic depiction of peasants as noble figures whose virtue was a function of their closeness to nature and, by extension, to God.

Portrait de Javain

Early in 1841 the Municipal Council of Cherbourg had commissioned Millet to paint a posthumous portrait of Colonel Javain, a former mayor of the town. Millet was supplied with a poor miniature that dated from Javain's youth. He was to be paid three hundred francs for the portrait, intended for the assembly hall of the Municipal Council. The likeness presented to the council on March 30, 1841, however, was judged unsatisfactory. The Council's displeasure was aggravated by a rumor that Millet had modeled the portrait's hands on those of a boy who had been imprisoned. Millet defended his painting, arguing that the portrait conformed to the commission as he and the subject's son and son-in-law understood it. The work was not "a family portrait whose principal quality was its completely bourgeois resemblance"; it was intended, rather, to represent for posterity a man "worthy to fulfill the mission with which he was charged during his life."

Portrait of a Man, said to be Leopold Desbrosses

Portrait of a Man: ca 1840-41

Portrait of a Man: ca 1845

Portrait of a Naval Officer: 1845

Portrait of a Woman

Portrait of Armand Ono

(aka The Man with the Pipe): 1843

Portrait of Catherine Roumy

Portrait of Eugene Canoville: 1840

Portrait of Madame Alfred Sensier

Portrait of Madame Ono: 1844

Portrait of the Artist's Sister, Emily: ca 1841-45

Portrait of the Widow Roumy

Reclining Female Nude: ca 1844-45

Return from the Fields: 1846-47

This idealized vision of noble peasant life was painted during a period of intense industrialization in France, accompanied by economic depression and the abandonment of farms. Nostalgic peasant scenes were especially popular in the 1840's, a stark contrast to the disillusionment and tension that would violently surface in the Revolution of 1848. The vague shapes and faces of the family seen here make them symbols of the land, rather than individuals.

The Return of the Flock

Seated Shepherdess

Seated Shepherdess

Millet was a farmer's son and in the late 1840's he became increasingly disenchanted with urban life and the rapacious progress of industrialisation. Nostalgia for the calm, settled rural life of his youth led him to make everyday rural life the central theme of his work.

Sheep Grazing along a Hedgerow

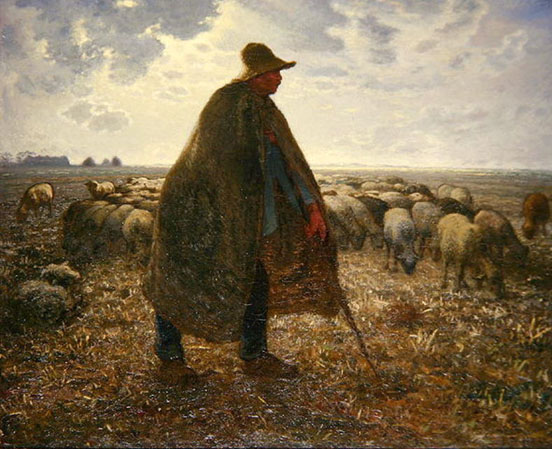

Shepherd Tending His Flock

The son of farmers, Millet understood both the reassuring cycle of the seasons and the frightening prospect of ruin at nature's whim. From the late 1840s', he dedicated his career to a simultaneously heroic and bleak depiction of the peasants of Barbizon, the farming community outside Paris where he lived. Millet's uncompromising representation of the French peasantry earned him the scorn of conservative critics. In this painting, Millet endows the shepherd with an imposing monumentality, bringing him to the foreground of the image, where he looms above the horizon line. Yet the figure hunches over his staff, his nearly featureless face gape-mouthed, perhaps with exhaustion or pain. And while Millet's shepherd tends a large flock, the parched yellow and brown grass in the foreground has been interpreted as a suggestion of future scarcity. Other scholars have offered religious readings of the image, likening the shepherd to Christ.

Shepherdess Seated in the Forest

Shepherdesses Seated in the Shade

Standing Spinner

Susanna and the Elders: ca 1846-49

Millet's 'Susanna and the Elders' is not the traditional representation of a maiden who is spied upon by old men while she bathes, but instead shows a young woman subjected to a violent sexual attack. It is a highly confronting reading of the story that is told in The Apocrypha.

After Millet moved from Paris to Barbizon in 1849, he abandoned Biblical and historic subjects for paintings of peasant life like 'The Angelus and The Gleaners'.

The Baby's Cereal: 1867

The Bather: 1846-48

The Bather: 1863

The Boiler: 1853-54

La lessiveuse: 1853-54

The Bouquet of Margueritas

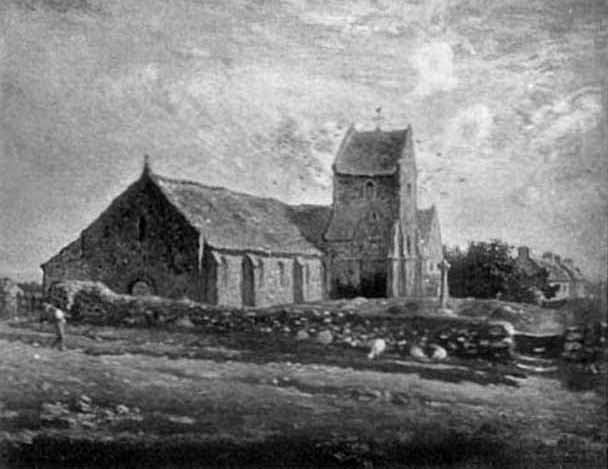

The Church at Greville: ca 1871-74

Years passed and the boy became a man and the man became a famous artist. But the path to fame had been a toilsome one, and as Millet pressed on his way he was able to return but seldom to the spots he had loved in his youth, and then only on sad errands. At length the time came (1871) when the artist brought his entire family to his native Grenville to spend a long summer holiday. Millet made many sketches of familiar scenes which gave him material for work for the next three years. One of these pictures was that of the village church, which he began to paint sitting at one of the windows of the inn where the family were staying.

If the building had lost the grandeur it possessed for his childish imagination, it was still full of artistic possibilities for a beautiful picture.

It is a solid structure, and we fancy that the builders did not have far to bring the stone of which it is composed. The great granite cliffs which rise from the sea must be an inexhaustible quarry. The building is low and broad, to withstand the bleak winds. A less substantial structure, perched on this plateau, would be swept over the cliffs into the sea. There is something about it suggestive of the sturdy character of the Norman peasants themselves, strong, patient, and enduring. It is very old; the passing years have covered the walls with moss, and nature seems to have made the place her own. It is as if, instead of being built with hands, it were a portion of the old cliffs themselves.

The grassy hillock against which the church nestles is filled with graves, a cross here and there marking the place where some more important personage is buried. Here is the sacred spot where Millet's saintly old grandmother was laid to rest. A rough stone wall surrounds the churchyard, as old and moss-grown as the building itself. Some stone steps leading into the yard are hollowed by the feet of many generations of worshippers. In the rear is a low stone house embowered in trees.

The square bell-tower lifts a weather-vane against the sky, and the birds flock about it as about an old home. The rather steep roof is slightly depressed, as if beginning to sink in.

With a painter's instinct Millet chose the point of view from which all the lines of the church would be most beautiful and whence we may see to the best advantage the quaint outlines of the tower. Beside this, he took for his work the day and hour when that great artist, the sun, could lend most effective help. So we see the simple little building at its best. The sky makes a glorious background, with fleecy clouds delicately veiling its brilliancy. The bright light throws a shadow of the tower across the roof, breaking the monotony of its length. The bareness of the big barn-like end is softened by the shadow in which it is seen. The plain side is decorated with the shadows of the buttresses and window embrasures.

The sheep are as much at home here as the birds. They nibble contentedly in the road by the wall, and are undisturbed by the approach of a villager. Beyond, at the left, is a glimpse of the level stretch of the sea. This is a spot where earth and sky and water meet, where the fishermen from the sea and the ploughmen from the fields come to worship God.

The First Steps

The Flight into Egypt

The Good Samaritan: 1846

The Goosegirl: ca 1866

The Gust of Wind: 1871-73

The Keeper of the Herd: 1871-74

The Little Shepherdess

The Knitting Lesson

Educated at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, Millet lived most of his life in rural Barbizon. There he found in the routines and rituals of peasant life the subjects that would occupy him throughout his career. This intimate scene of a mother teaching her young daughter to knit reflects the influence of Dutch genre painting, although Millet's approach is unstinting in its honesty and self-effacement.

The Laundress

The Nobleman of Capernaum

The Old Mill: 1866-70

Pastel with stumping, pen and black ink, and touches of black chalk, on cream wove paper, laid down on wood pulp board.

The Peasant Family: 1871-72

Begun in 1871-72 but left unfinished, this haunting scene depicts a Norman peasant family in their farmyard. It embodies a primitivism which may draw upon Egyptian sculpture and Quattrocento paintings seen by Millet in the Louvre. The British painter Sickert commented: 'The sublime man and his stolid spouse face the spectator with all the gravity and symmetry of two caryatids, while the child essays, a baby Samson, the strength of the pillars of his house'.

The Pig Killers

From medieval times, the slaughter of the fatted pig was associated with November or December. Under a grey sky, the scene is rendered in somber tones in keeping with the subject. Millet has chosen to illustrate the dramatic moment when the animal resists being pushed, pulled, or coaxed across the courtyard to the slaughtering block.

The Potato Harvest: 1855

The Seamstress

The Sheepfold, Moonlight: 1856-60

The Shooting Stars

The Stubble Burner

The Walk to Work: 1851

The Whisper: ca 1846

The title is traditional in the 19th century the picture was called 'Peasant and Child'. This picture was probably painted in about 1846, and is one of a number of pastoral subjects painted by Millet during his early career in his so-called 'manière fleurie'.

The Wood Sawyers: 1848

This is a very dynamic image: the bodies of the workers are sharply bent towards different, sometimes opposing directions, creating a swirling rhythm that dominates the scene completely. Labor - the activity of logging - becomes the protagonist; faces are covered to let the bodily movements speak. The three men form a triangle that serves as an abstract geometrical formula for the sweaty dance they perform. Every part of the body engages in the process. The leg muscles of the central figure are bulging, the shoulders and the back of the man on the left are fully engaged and the torso of the farthest logger is strained to the maximum. The giant trees further emphasize the energy involved in their cutting; they are formidable opponents and give in slowly and without the enthusiasm of the men. The monumental struggle between the two sides reveals the hardships of this livelihood, but also marks it as aesthetically and symbolically meaningful. A sense of pride and self-respect hovers above these hard workers.

Jean-Francois Millet | Art & Critique

The Woodchopper: 1858-66

Another Woodchopper

un Tailleur De Pierres

(The Stone Cutter)

Vert Vert, the Nun's Parrot: 1839

Woman Carrying Firewood and a Pail

Woman Grazing her Cow: 1858

Woman Reclining in a Landscape: 1846-47

Woman Sewing by Lamplight

It has been suggested that Millet's many scenes of peasant women and their families working by lamplight were inspired by his fondness for Latin bucolic poetry, especially certain lines from Virgil's Georgics. Similar treatments by Rembrandt and other Dutch painters may also have influenced his choice of themes, but ultimately this picture relates most closely to what the artist was witnessing in his own home, as he wrote to a friend the year the canvas was completed: "I write this, today, November 6th at 9 o'clock in the evening. Everyone is at work around me, sewing, and darning stockings. The table is covered with bits of cloth and balls of yarn. I watch from time to time the effects produced on all this by the light of the lamp. Those who work around me at the table are my wife and grown-up daughters."

Woman with a Rake: ca 1856-57

Millet first treated this subject in a woodcut, one of a series of ten "Labors of the Fields" published in a popular periodical in 1853. The art dealer Martinet, in whose gallery such avant-garde artists as Courbet and Manet exhibited, included this painting in a show in 1860.

Wood Chopper Bucheron

Young Girl Playing a Mandolin

Young Shepherdess: ca 1871

Young Woman: 1844-45

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.