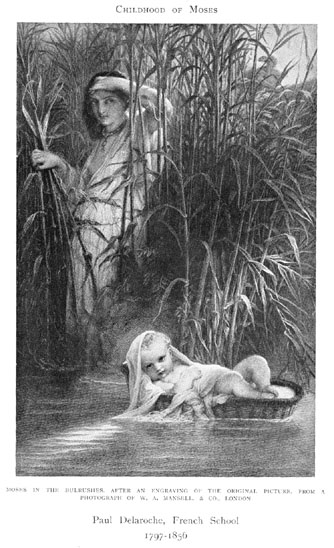

French Academic and History Painter

1797 - 1856

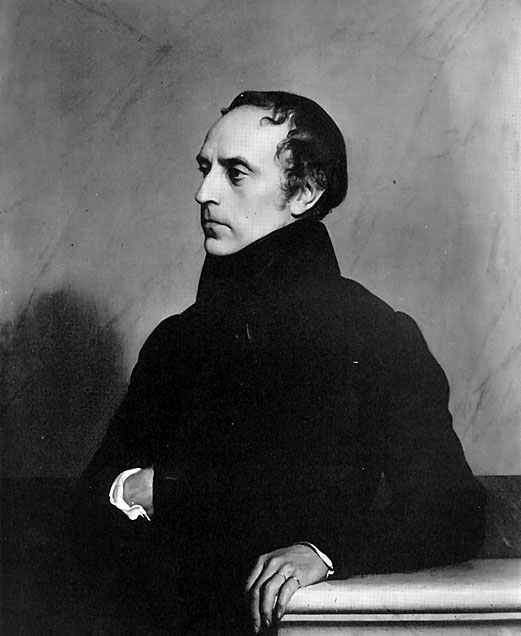

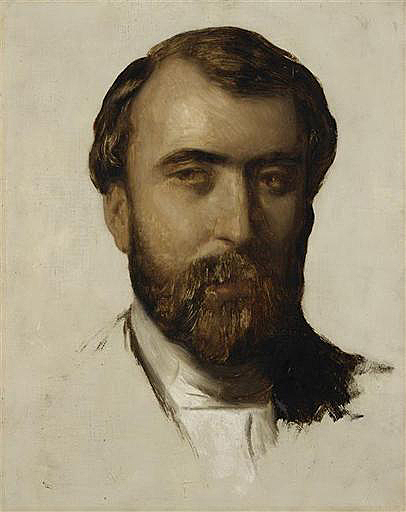

Hippolyte Delaroche, commonly known as Paul Delaroche (July 17, 1797 - November 4, 1856) was a French painter born in Paris.

Delaroche was born into a wealthy family and was trained by Antoine-Jean Gros, who then painted life-size histories and had many students.

The first Delaroche picture exhibited was the large "Josabeth saving Joas" (1822). This exhibition led to his acquaintance with Théodore Géricault and Eugène Delacroix, with whom he became friends. The three of them were the central group of a large body of historical painters, such as perhaps never before lived in one locality and at one time.

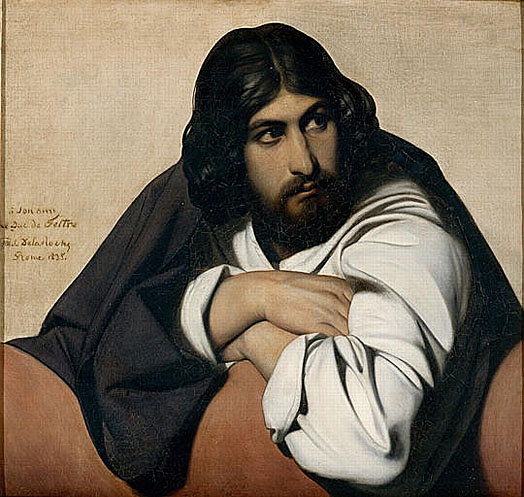

He visited Italy in 1838 and 1843, when his father-in-law, Horace Vernet, was director of the French Academy in Rome.

His studio in Paris was in the rue Mazarine. His subjects were painted with a firm, solid, smooth surface, which gave an appearance of the highest finish. This texture was the manner of the day and was also found in the works of Horace Vernet, Ary Scheffer, Louis-Leopold Robert and Ingres.

Delaroche's work was not always historically accurate. "Cromwell lifting the Coffin-lid and looking at the Body of Charles" is an incident only to be excused by an improbable tradition; but "The King in the Guard-Room, with villainous roundhead soldiers blowing tobacco smoke in his patient face," is a libel on the Puritans; and "Queen Elizabeth dying on the Ground," like a she-dragon no one dares to touch, is sensational; while "The Execution of Lady Jane Grey" is represented as taking place in a dungeon, which is badly inaccurate.

The painting was exhibited at the Salon of 1827/28.

The painting depicts the last moments on 12 February 1554 in the life of the seventeen-year old Jane Grey, a great granddaughter of Henry VII who was proclaimed Queen of England upon the death of young King Edward VI, a Protestant like herself. She reigned for nine days in 1553, but, through the machinations of the partisans of Henry VIII's Catholic daughter, Mary Tudor, she was convicted of high treason and sentenced to death in the Tower of London.

Delaroche, who based the painting on a sixteenth-century Protestant martyrology, has falsified the historical account the better to appeal to his contemporaries. Lady Jane Grey, a humanist-educated young married woman, was in fact executed out of doors. Attended by two gentlewomen, probably no less stoical than she, she resolutely made her own way to the block. She could not have worn a white satin dress of nineteenth-century cut with a whalebone corset, and her hair would have been tucked up, not streaming down over her shoulders. But a painting cannot be judged by the criteria of historical accuracy. Much more applicable to this particular picture are the standards of popular melodrama and tableau vivant.

As on a stage, the heroine gropes her way towards the audience, gently guided by the elderly Constable of the Tower whose massive, dark, male presence acts as a foil to her own. A spotlight trained on her from above complements the dim stage lighting, reflecting from her immaculate dress and the straw which spills over into the front row of the stalls. The emotions of each actor are carefully delineated and distinguished, and we are left in no doubt as to the character of each even of the lady in the background who turns her back on the terrible sight.

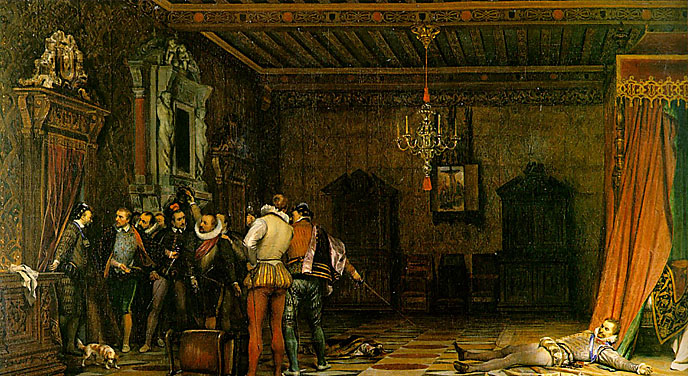

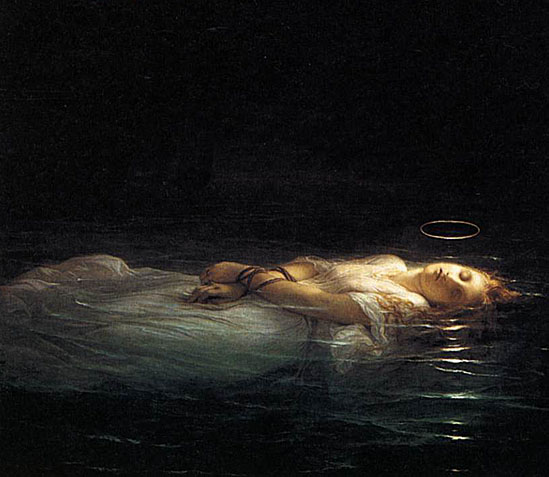

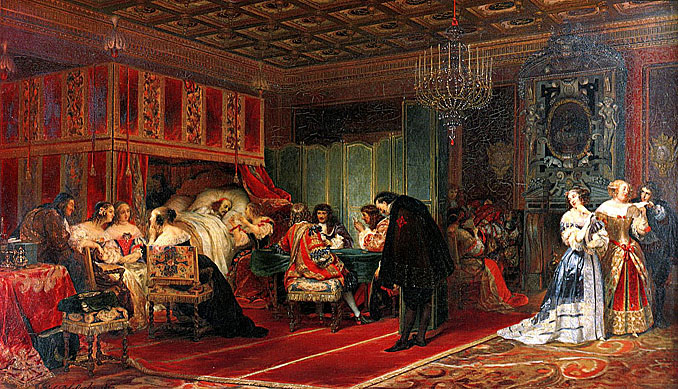

On the other hand, "Strafford led to Execution," when Laud stretches his lawn-covered arms out of the small high window of his cell to give him a blessing as he passes along the corridor, is perfect; and the splendid scene of Richelieu in his gorgeous barge, preceding the boat containing Cinq-Mars and De Thou carried to execution by their guards, is perhaps the most dramatic semi-historical work ever done. His 1835 "Assassination of the duc de Guise at Blois" is an exacting historical study was well a dramatic insight into human nature. Other important Delaroche works include "The Princes in the Tower" and the "La Jeune Martyr" (Young female Martyr floating dead on the Tiber).

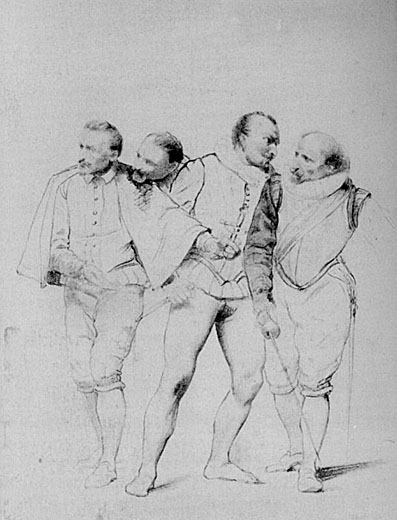

The Lords passed the Bill of Attainder, and it remained for the king to give or to withhold his consent. Some may think that it was Charles's duty to risk his life to defend Strafford. But the mob raged round Whitehall, howling for blood. Charles feared for the safety of the queen and his children, and he gave way. ' If my own person only were in danger', he told the Council, with tears in his eyes, 'I would gladly venture it to save Lord Strafford's life.' Three days later the earl was led to his execution in May 1641 in the presence of a crowd of 200000 people who had come to witness the end of 'Black Tom Tyrant'. No man ever died more bravely. 'I thank my God', he said, as he prepared to die, 'I am not afraid of death, but do as cheerfully put off my doublet at this time as ever I did when I went to bed.' The executioner offered to cover his eyes with a handkerchief. 'Thou shall not bind my eyes.' said Strafford, 'for I will see it done.' And so he placed his head upon the block.

At a meeting of the council at the Tower on the thirteenth of June, ostensibly to discuss Edward V's coronation, Gloucester, the Lord Protector, had William, Lord Hastings suddenly and unexpectedly arrested on a charge of treason. Hastings, while he detested the Woodvilles, had been a close friend of Edward IV and would never have countenanced the disinheriting of his children. He was executed, without trial, the same day on a block of wood.

The legitimacy of the young Edward V then began to be actively questioned, and the old claim of Edward IV not being the true son of Richard, Duke of York was resurrected by Buckingham, who stated that the late King's true father had been an archer named Blackburn, who was supposed to have had an adulterous affair with Cecily, Duchess of York.

He also argued that the late King Edward IV's marriage to Elizabeth Woodville was invalid, due to Edward's previous troth-plight to Lady Eleanor Butler, rendering both Princes bastards. He then called on Richard to ascend the throne as the true heir of York, pointing out his resemblance to his father. After an initial feigned show of reluctance, Richard then 'accepted' and was crowned in his nephew's place. Many saw through this dissembling, but since he was now all powerful, none were in a position to oppose him directly.

The two young princes had been seen playing in the Tower gardens at various times until then. Gradually, they began to appear less frequently. The last person to see them alive was Edward V's physician, Dr. Argentine, who had attended him at the Tower and found him in a state of abject melancholy.

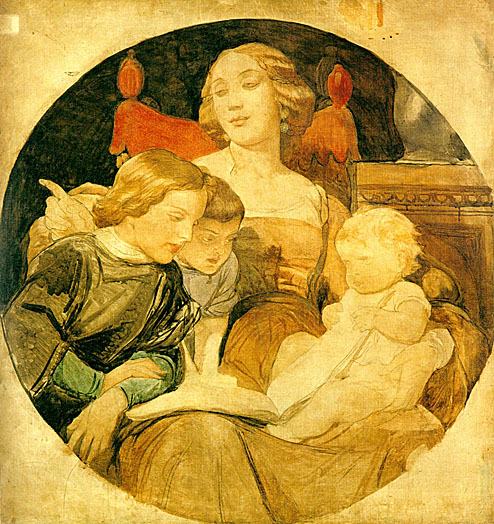

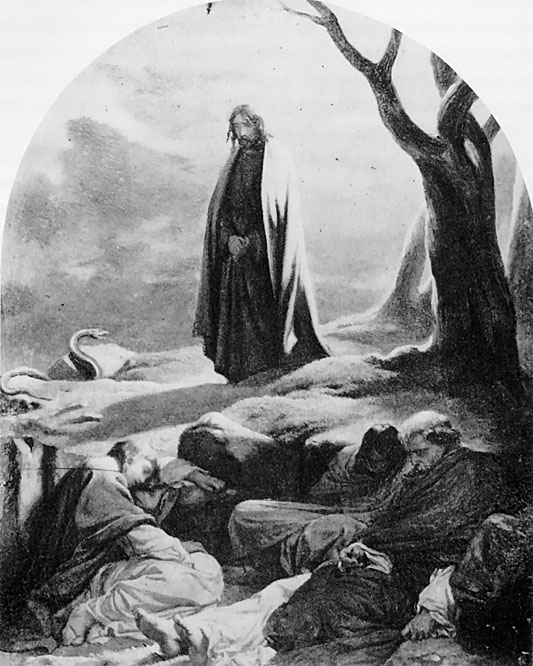

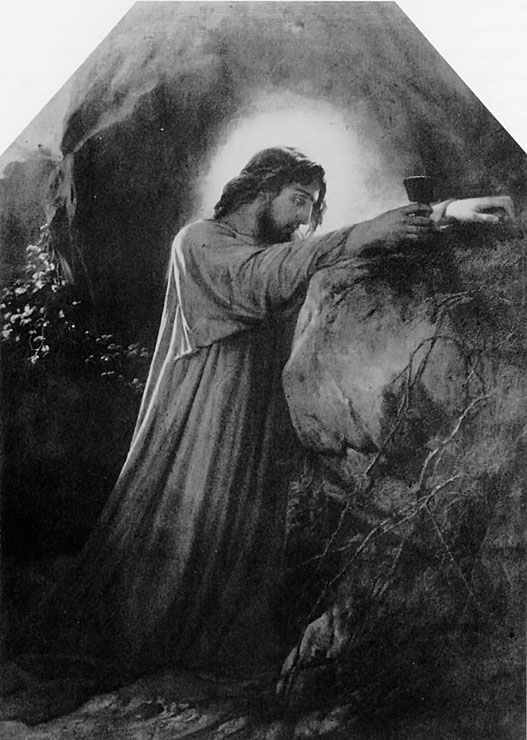

Delaroche's love for Horace Vernet's young daughter Louise was the absorbing passion of his life. In 1835, he exhibited the "Head of an Angel," which was based on a study of her. It is said that Delaroche never recovered from the shock of her 1845 death. After her death his finest works were the extremely serious sequence of small elaborate pictures of incidents in the Passion. Two of these, the Virgin and the other Manes, with the apostles Peter and John, within a nearly dark apartment, hearing the crowd as it passes hailing Christ to Calvary, and St John conducting the Virgin home again after all is over, are beyond all praise as exhibiting the divine story from a simply human point of view. They are pure and elevated, and also dramatic and painful.

The most serious charge, however, was that she sexually abused her son. This was according to Louis Charles, who, through his coaching by Hébert and his guardian, accused his mother. The accusation caused Marie Antoinette to protest so emotionally that the women present in the courtroom - the market women who had stormed the palace for her entrails in 1789 - ironically also began to support her. However, in reality the outcome of the trial had already been decided by the Committee of Public Safety around the time the Carnation Plot was uncovered, and she was declared guilty of treason in the early morning of October 16, after two days of proceedings. She was executed later that day, at 12:15 pm, two and a half weeks before her thirty-eighth birthday. Her body was thrown in an unmarked grave in the former La Madeleine cemetery (closed in 1794). Both her body and that of Louis XVI were exhumed on January 18, 1815. Proper Christian burial of the royal remains took place three days later, on January 21, in the necropolis of French Kings at St. Denis Basilica.

Delaroche was not troubled by ideals, and had no affectation of them. His sound but hard execution allowed no mystery to intervene between him and his motif, which was intelligible to the million. Thus it is that essentially the same treatment was applied by him to the characters of distant historical times, the founders of the Christian religion, and the real people of his own day, such as "Napoleon at Fontainebleau," or "Napoleon at Saint Helena," or "Marie Antoinette leaving the Convention after her sentence."

By that time, Napoleon had ruled France and surrounding countries for twenty years. Originally an officer in the French Army, he had risen to become Emperor amid the political chaos following the French Revolution in which the old ruling order of French kings and nobility had been destroyed.

Napoleon built a 500,000 strong Grand Army which used modern tactics and improvisation in battle to sweep across Europe and acquire an Empire for France.

But in 1812, the seemingly invincible Napoleon made the fateful decision to invade Russia. He advanced deep into that vast country, eventually reaching Moscow in September. He found Moscow had been burned by the Russians and could not support the hungry French Army over the long winter. Thus Napoleon was forced to begin a long retreat, and saw his army decimated to a mere 20,000 men by the severe Russian winter and chaos in the ranks.

England, Austria, and Prussia then formed an alliance with Russia against Napoleon, who rebuilt his armies and won several minor victories over the Allies, but was soundly defeated in a three-day battle at Leipzig. On March 30, 1814, Paris was captured by the Allies. Napoleon then lost the support of most of his generals and was forced to abdicate on April 6, 1814.

In the courtyard at Fontainebleau, Napoleon bid farewell to the remaining faithful officers of the Old Guard...

Soldiers of my Old Guard: I bid you farewell. For twenty years I have constantly accompanied you on the road to honor and glory. In these latter times, as in the days of our prosperity, you have invariably been models of courage and fidelity. With men such as you our cause could not be lost; but the war would have been interminable; it would have been civil war, and that would have entailed deeper misfortunes on France.

I have sacrificed all of my interests to those of the country.

I go, but you, my friends, will continue to serve France. Her happiness was my only thought. It will still be the object of my wishes. Do not regret my fate; if I have consented to survive, it is to serve your glory. I intend to write the history of the great achievements we have performed together. Adieu, my friends. Would I could press you all to my heart.

Napoleon Bonaparte - April 20, 1814

Following this, Napoleon was sent into exile on the little island of Elba off the coast of Italy. But ten months later, in March of 1815, he escaped back into France. Accompanied by a thousand men from his Old Guard he marched toward Paris and gathered an army of supporters along the way.

Once again, Napoleon assumed the position of Emperor, but it lasted only a 100 days until the battle of Waterloo, June 18, 1815, where he was finally defeated by the combined English and Prussian armies.

A month later he was sent into exile on the island of St. Helena off the coast of Africa. On May 5, 1821, the former vain-glorious Emperor died alone on the tiny island abandoned by everyone. In 1840 his body was taken back to France and buried in Paris.

In 1801 Jacques Louis David had painted a flamboyant official portrait of Napoleon crossing the Alps on a rearing horse. In that work Napoleon is pointing to the sky with his cloak swirling dramatically around him. Delaroche's literal accuracy and careful detail shows the gradual development of realism in the 19th century.

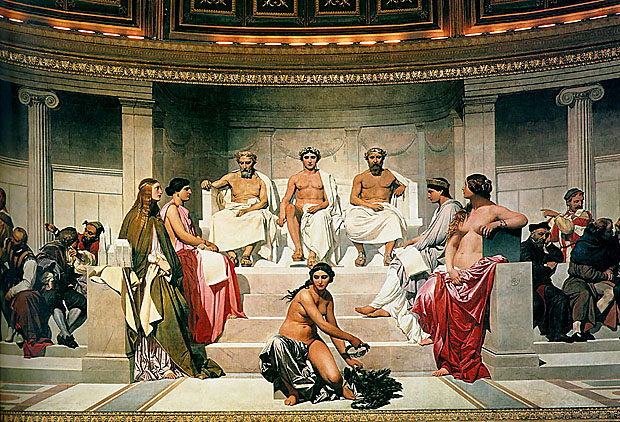

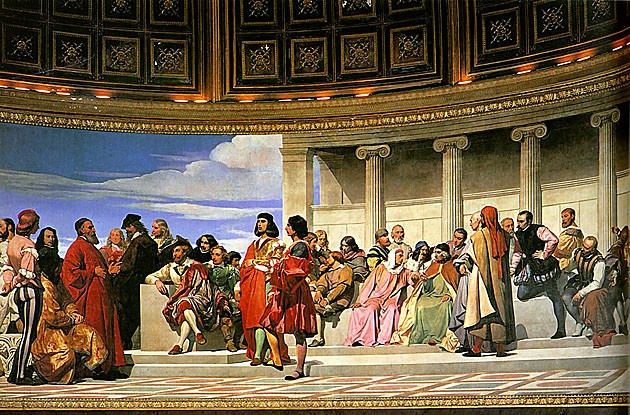

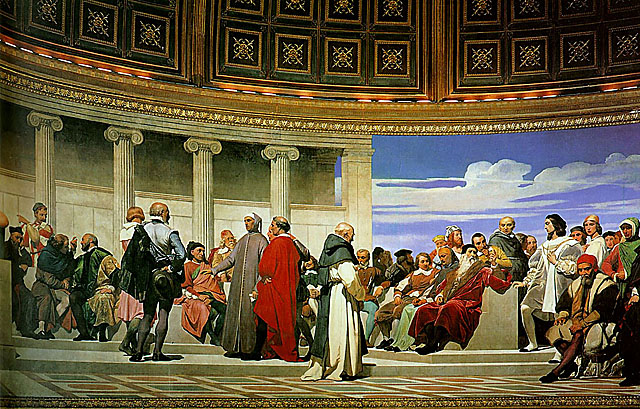

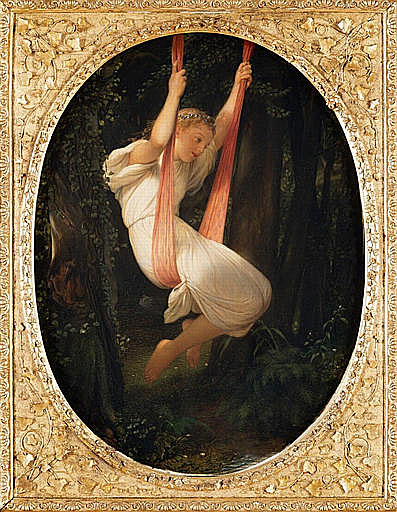

In 1837 Delaroche received the commission for the great picture, 27 metres long, in the hemicycle of the award theatre of the École des Beaux Arts. The commission came from the Ecole's architect, Felix Duban. This represents seventy-five great artists of all ages, in conversation, assembled in groups on either hand of a central elevation of white marble steps, on the topmost of which are three thrones filled by the creators of the Parthenon: architect Phidias, sculptor Ictinus, and painter Apelles, symbolizing the unity of these arts.

To supply the female element in this vast composition he introduced the genii or muses, who symbolize or reign over the arts, leaning against the balustrade of the steps, beautiful and queenly figures with a certain antique perfection of form, but not informed by any wonderful or profound expression. The portrait figures are nearly all unexceptionable and admirable. This great and successful work is on the wall itself, an inner wall however, and is executed in oil. It was finished in 1841, and considerably injured by a fire which occurred in 1855, which injury he immediately set himself to remedy (finished by Joseph-Nicolas Robert-Fleury); but he died before he had well begun, on the 4th of November 1856.

~Senex Magister

~Senex Magister

Guizot is famous as the originator of the quote "Not to be a republican at 20 is proof of want of heart; to be one at 30 is proof of want of head." This quote has been reworked many times especially in reference to socialism and liberalism. It has notably been used by and attributed to Winston Churchill, George Bernard Shaw, Benjamin Disraeli, Georges Clemenceau, Wendell L. Willkie, Aristide Briand, Woodrow Wilson, and Otto Von Bismarck, Lloyd George and William Casey and many others.

Joan asserted that she had visions from God that told her to recover her homeland from English domination late in the Hundred Years' War. The uncrowned King Charles VII sent her to the siege at Orléans as part of a relief mission. She gained prominence when she overcame the dismissive attitude of veteran commanders and lifted the siege in only nine days. Several more swift victories led to Charles VII's coronation at Reims and settled the disputed succession to the throne.

The renewed French confidence outlasted her own brief career. She refused to leave the field when she was wounded during an attempt to recapture Paris that autumn. Hampered by court intrigues, she led only minor companies from then onward and fell prisoner at a skirmish near Compiègne the following spring. A politically motivated trial convicted her of heresy. The English regent John of Lancaster, 1st Duke of Bedford had her burnt at the stake in Rouen. She had been the heroine of her country at 17 and died when only 19 years old. Some 24 years later, Pope Callixtus III reopened the case, and a new finding overturned the original conviction. Her piety to the end impressed the retrial court. Pope Benedict XV canonized her on May 16, 1920.,P.

She has remained an important figure throughout Western culture. From Napoleon to the present, French politicians of all leanings have invoked her memory. Major writers and composers who have created works about her include Shakespeare, Voltaire, Schiller, Verdi, Tchaikovsky, Twain, and Shaw. Depictions of her continue in film, television, song, and dance.

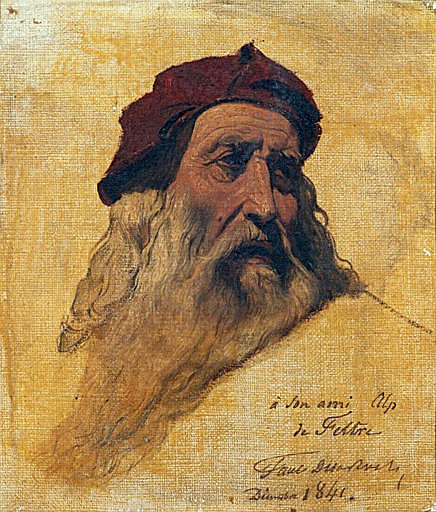

A True Renaissance Man

The illegitimate son of a 25-year-old notary, Ser Piero, and a peasant girl, Caterina, Leonardo was born on April 15, 1452, in Vinci, Italy, just outside Florence. His father took custody of the little fellow shortly after his birth, while his mother married someone else and moved to a neighboring town. They kept on having kids, although not with each other, and they eventually supplied him with a total of 17 half sisters and brothers.

Growing up in his father's Vinci home, Leonardo had access to scholarly texts owned by family and friends. He was also exposed to Vinci's longstanding painting tradition, and when he was about 15 his father apprenticed him to the renowned workshop of Andrea del Verrochio in Florence. Even as an apprentice, Leonardo demonstrated his colossal talent. Indeed, his genius seems to have seeped into a number of pieces produced by the Verrocchio's workshop from the period 1470 to 1475. For example, one of Leonardo's first big breaks was to paint an angel in Verrochio's "Baptism of Christ," and Leonardo was so much better than his master's that Verrochio allegedly resolved never to paint again. Leonardo stayed in the Verrocchio workshop until 1477 when he set up a shingle for himself.

In search of new challenges and the big bucks, he entered the service of the Duke of Milan in 1482, abandoning his first commission in Florence, "The Adoration of the Magi". He spent 17 years in Milan, leaving only after Duke Ludovico Sforza's fall from power in 1499. It was during these years that Leonardo hit his stride, reaching new heights of scientific and artistic achievement.

The Duke kept Leonardo busy painting and sculpting and designing elaborate court festivals, but he also put Leonardo to work designing weapons, buildings and machinery. From 1485 to 1490, Leonardo produced a studies on loads of subjects, including nature, flying machines, geometry, mechanics, municipal construction, canals and architecture (designing everything from churches to fortresses). His studies from this period contain designs for advanced weapons, including a tank and other war vehicles, various combat devices, and submarines. Also during this period, Leonardo produced his first anatomical studies. His Milan workshop was a veritable hive of activity, buzzing with apprentices and students.

Alas, Leonardo's interests were so broad, and he was so often compelled by new subjects, that he usually failed to finish what he started. This lack of "stick-to-it-ness" resulted in his completing only about six works in these 17 years, including "The Last Supper" and "The Virgin on the Rocks," and he left dozens of paintings and projects unfinished or unrealized (see "Big Horse" in sidebar). He spent most of his time studying science, either by going out into nature and observing things or by locking himself away in his workshop cutting up bodies or pondering universal truths.

Between 1490 and 1495 he developed his habit of recording his studies in meticulously illustrated notebooks. His work covered four main themes: painting, architecture, the elements of mechanics, and human anatomy. These studies and sketches were collected into various codices and manuscripts, which are now hungrily collected by museums and individuals (Bill Gates recently plunked down $30 million for the Codex Leicester!).

Back to Milan... after the invasion by the French and Ludovico Sforza's fall from power in 1499, Leonardo was left to search for a new patron. Over the next 16 years, Leonardo worked and traveled throughout Italy for a number of employers, including the dastardly Cesare Borgia. He traveled for a year with Borgia's army as a military engineer and even met Niccolo Machiavelli, author of "The Prince." Leonardo also designed a bridge to span the "golden horn" in Constantinople during this period and received a commission, with the help of Machiavelli, to paint the "Battle of Anghiari."

About 1503, Leonardo reportedly began work on the "Mona Lisa." On July 9, 1504, he received notice of the death of his father, Ser Piero. Through the contrivances of his meddling half brothers and sisters, Leonardo was deprived of any inheritance. The death of a beloved uncle also resulted in a scuffle over inheritance, but this time Leonardo beat out his scheming siblings and wound up with use of the uncle's land and money.

From 1513 to 1516, he worked in Rome, maintaining a workshop and undertaking a variety of projects for the Pope. He continued his studies of human anatomy and physiology, but the Pope forbade him from dissecting cadavers, which truly cramped his style.

Following the death of his patron Giuliano de' Medici in March of 1516, he was offered the title of Premier Painter and Engineer and Architect of the King by Francis I in France. His last and perhaps most generous patron, Francis I provided Leonardo with a cushy job, including a stipend and manor house near the royal chateau at Amboise.

Although suffering from a paralysis of the right hand, Leonardo was still able to draw and teach. He produced studies for the Virgin Mary from "The Virgin and Child with St. Anne", studies of cats, horses, dragons, St. George, anatomical studies, studies on the nature of water, drawings of the Deluge, and of various machines.

Leonardo died on May 2, 1519 in Cloux, France. Legend has it that King Francis was at his side when he died, cradling Leonardo's head in his arms.

The subject of countless books, films and works of art, Peter the Great is probably the most famous member of the Romanov family. He single-handedly changed the course of Russian history, turning the country into a powerful empire ranking alongside the other European powers. The imperial period of Russian history begins with Peter I.

Peter was born in Moscow on 30 May, 1672, and baptized at the Monastery of the Miracle on 29 June, 1672. He began walking at the age of six months. At the age of five, he was introduced to his first tutor--Nikita Zotov, a deacon of the petitions department. Although he learnt to read and write, he did not receive a good education.

On the death of his father on 27 April, 1682, Peter was proclaimed tsar at the age of ten. The intrigues of the Miloslavksy family, however, led to the Streltsy revolt and the murder of his mother's allies in Moscow in May 1682. The upshot was the crowning of two co-tsars with Sophia as regent. Peter and his mother were forced to leave Moscow and live in Preobrazhenskoe, once the favorite residence or, in the words of Vasily Klyuchevsky, "a stopping place on the way to St. Petersburg."

Peter was haunted by the memories of the Streltsy uprising and fears for the future. There was no force at Preobrazhenskoe capable of defending him and his mother should the Streltsy revolt break out again. He decided to create his own army.

Besides the children of the boyars, the tsar was joined at Preobrazhenskoe by a large number of courtiers. From their ranks he formed a toy (poteshny) brigade, which gradually, under the guise of childhood games, turned into a military unit. This detachment was called the Preobrazhensky Toy Regiment. When the number of amateur forces grew, a second battalion was formed in the neighboring village of Semyonovskoe, called the Semyonovsky Toy Brigade. The forces were trained by foreign officers in the West European manner. They fought mock battles with real weapons, often leading to serious injuries and several deaths. Peter's steward, Prince Ivan Dolgoruky, was killed during one such battle, while the tsar's face was badly burnt in an artillery barrage. The first mock battles were more like village fistfights. The two regiments would line up against a detachment of Streltsy guards on the bank of the River Yauza. Brawny representatives of each "army" came forward and began insulting one another. The situation became increasingly heated, with the two sides eventually coming to blows. The foreign instructors gradually began to develop these battles into regular maneuvers along Western lines. A fortress called Pressburg--a miniature copy of the fort in modern-day Bratislava--was built on the River Yauza to study the art of defending and besieging fortifications. Besides infantry formations, there were also artillery and cavalry detachments and a toy navy on Lake Pereyaslavl.

The toy forces were officially renamed the Preobrazhensky and Semyonovsky Regiments in 1687. The four hundred officers were mostly foreigners, although only Russian noblemen could fill the rank of sergeant. Both regiments were headed by General Artamon Golovin. The size of the regiments gradually grew. By the mid-1690s, the Preobrazhensky Regiment had ten companies, including a bomber sqaud. The Preobrazhensky and Semyonovsky regiments gave Peter the means to defend himself from possible enemies and a tool to resolve important matters of state.

In August, 1689, he learned that Sophia and her new lover, Feodor Shaklovity, were preparing a coup d'etat. Peter left Preobrazhenskoe for the safety of the Trinity Monastery at Sergiev Posad, where he was joined by the Preobrazhensky and Semyonovsky regiments. He managed to isolate and overthrow the "third, discreditable person," as he referred to Sophia in his letters to his brother Ivan. She was incarcerated in the Novodevichy Convent, while her Streltsy supporters went to the scaffold.

Peter did not abandon his war games after securing his hold on the throne. He entrusted all affairs of state to his mother, a shrewd, but, however, not very intelligent woman. She was helped by Prince Vasily Golitsyn (a heavy drinker and a shrewd politician) and her brother Lev (another heavy drinker and a poor politician). Her council included Tikhon Streshnev, a master of intrigue whom many believed to be Peter's real father. The tsar often referred to him as "father" and appointed him Minister of War in 1701. In his poem Russia, Maximilian Voloshin describes one of Peter's attempts to learn the truth of his origin:

Natalia Naryshkina sometimes made independent decisions, such as the decree banishing the Jesuits from Russia or burning of Kulman the Mystic at the stake on Red Square. Patrick Gordon, a Scottish general in Russia service, complained in a letter to London in July 1690 that Peter was completely uninterested in governing. He divided his time between drinking sessions and toy battles, leading what Vasily Klyuchevsky called "the life of a homeless, itinerant student. "The Crimean Tatars, meanwhile, defeated Prince Golitsyn and captured a number of Russian provinces. Russia's prestige in Europe fell. When a new sultan assumed power in Turkey, he informed all the European rulers, with the exception of the Russian tsar .

When Peter's mother died in 1694, he was forced to take over the running of the state. In 1695 and 1696, he led two attempts to capture the Turkish fortress of Azov. The second attempt was successful and Peter founded a Russian fleet at Azov. In 1697, he decided to go on a fact-finding mission to Europe. The Great Embassy left Moscow in March, with the tsar travelling incognito as "Peter Mikhailov, sergeant of the Preobrazhensky regiment." Peter I visited Holland, England, Germany and Austria, where he studied shipbuilding, anatomy, dentistry and many other skills and crafts. His plans to visit Italy in 1698 were thwarted when he received news of another revolt of the Streltsy guards in support of Sophia. Although the tsar hurried back to Moscow, by the time he arrived the revolt had already been put down by his "toy" regiments.

Prince Feodor Romodanovsky of the Preobrazhensky Office launched an official investigation into the revolt. Streltsy guards were exectuted en masse, with Peter himself chopping off several heads. In February 1699 the Streltsy detachments were disbanded and any surviving guards were banished to the far reaches of the country.

Peter decided to make a clean sweep by confining his wife Eudokia to a convent. When he was nineteen, his mother had married him to the sixteen-year-old daughter of Illarion Lopukhin on 27 January, 1689. Although her name was actually Praskovia Illarionovna, Peter's mother thought that Eudokia sounded better. She did not like the father's name either and he was forced to change it to Feodor. Praskovia Illarionovna thus became Eudokia Feodorovna. Prince Boris Kurakin describes her as a handsome girl of "only average intelligence." Peter and Eudokia's marriage was initially happy. Eudokia gave birth to a son called Alexei in 1690, followed by two more boys. Peter then tired of his wife and began a relationship with Anna Mons, the daughter of a wine trader in the German Suburb (foreigners' settlement).

Following the breakdown of their marriage, Peter decided to rid himself of Eudokia. He banished her to the Convent of the Intercession in Suzdal on 23 September, 1698. The following year, he sent Semyon Yazkov to the convent to inform Eudokia that she was to join the sisterhood as Sister Helen. In 1709, Peter's former wife began a nine-year love affair with Captain Stepan Glebov. This came to light in 1718, when the tsar was investigating the flight abroad of their son, Tsarevich Alexei. Both were harshly punished. Stepan Glebov was impaled, while Eudokia was tortured and moved to the Convent of the Dormition in Staraya (Old) Ladoga.

Eudokia's troubles did not end there. When Peter's second wife ascended the throne in 1725, she was imprisoned at Schlusselburg and only released on October 1727, during the reign of her grandson, Peter II. The former tsarina spent the rest of her life at the Novodevichy Convent in Moscow, where she died in 1731. She was buried there alongside three of Peter's half-sisters--Sophia, Ekaterina and Eudokia.

Much has been written about Peter's physical appearance, particularly his great height. The closest physical likeness to the tsar is Mikhail Shemyakin's famous statue in the Peter and Paul Fortress. Valentin Serov, a fin-de-siecle Russian artist who painted a series of works dedicated to Peter the Great, a figure he admired, compiled his own image of the tsar: "It is regretful that a man who did not have a single jot of sweetness about him is always portrayed as some operatic hero or beauty. He was frightening to look at--a long body on thin, scrawny legs, with such a small head in comparison to the rest of his body that he must have looked more like a scarecrow with a badly fitting head than a living person. He was forever grimacing, winking, twitching his mouth and slapping his chin. He took enormous strides and his companions were forced to run to keep up with him. I can imagine what a monster he must have seemed to foreigners and how frightening he was to the people of St. Petersburg. A freak with a constantly twitching head . . . a terrible person."

Peter had a nervous character. He was quick to fly into a rage, when his face would begin to twitch--possibly a nervous reaction brought on by the shock of the Streltsy revolt in his childhood. Vasily Klyuchevsky noted another of his traits: "In keeping with Old Russian habits, Peter did not like wide rooms or high ceilings. He always avoided magnificent royal palaces whenever he was abroad. A son of the endless Russian steppe, he felt suffocated among the hills of a narrow German valley. Strangely enough, growing up in the open air and accustomed to wide spaces, he could not live a room with a high ceiling. Whenever he found himself in one, he would order a special canvas ceiling to be hung low. Perhaps the cramped conditions of his childhood left its mark on him."

Peter the Great had an iron will and boundless energy. He was ambitious, intuitive, despotic, courageous, cruel and self-assured. The tsar could be decisive, forceful, convulsive and fidgety. He combined an amazing capacity for work with an equal unquenchable thirst for amusement. His curious and lively mind led him to acquire knowledge in many different crafts and sciences, including shipbuilding, artillery, fortifications, diplomacy, military tactics, mechanics, medicine and astronomy. The tsar held audiences with such leading scientists as Gottfried Wilhelm Leibnitz and Sir Issac Newton and was elected an honorary member of the French Academy of Sciences in 1717.

Peter the Great developed Russian industry, opening many new factories, mills and mines and building the Vyshny Volochek and Ladoga Canals. The merchant class was divided into guilds, while craftsmen were grouped in corporations. Medical institutes, a public theatre and schools of translators were opened. New forms of clothing, assemblies, taxes and letterhead notepaper were introduced. New silver coins were minted. The reforms of Peter the Great affected virtually every aspect of Russian life. Peter created a pyramidal form of state structure. The peasantry served the nobility, the nobility served the monarch and the monarch served the state.

On 5 February, 1722, Peter signed a decree altering the way in which the Russian throne was inherited. Instead of the crown passing from father to son, the sovereign would henceforth nominate his own successor from the members of his family. In 1724, Peter signed a document bequeathing the throne to Catherine, who was crowned empress in the Dormition Cathedral in Moscow on 7 May, 1724. Later that year, Peter learned of Catherine's love affair with the chamberlain William Mons. They were only discovered by accident, during an investigation into an accusation of bribery and embezzlement. William Mons was executed and Peter tore up the document naming Catherine as his successor.

Peter began 1725 in poor health. On 16 January, he took to his bed. The pains grew worse and his groans and cries could be heard throughout the palace. Under the terms of his manifesto changing the rules of inheritance, the emperor was obliged to name his own successor. On 27 January, he sat down to write his will, but managed to command Leave everything to . . .

On 28 January, 1725, Peter died in great pain from a stone in his bladder. He was buried in the still unfinished St. Peter and St. Paul Cathedral in St. Petersburg. The tsar was officially proclaimed "Emperor Peter the Great of All the Russias." Many, however, believed that he was the Antichrist, sent to punish Russia for her sins. Public opinion was sharply split over the merits of his reign.

Peter the Great died without leaving an official heir. A meeting of senators, clergymen, generals and guards officers was split over who should inherit the throne. Members of the old aristocracy--the Dolgoruky, Golitsyn and Repnin families--wanted to offer the crown to Alexei's son Peter, the eleven-year-old grandson of Peter the Great. They regarded Catherine as a Lithuanian laundress not worthy of even approaching the Russian throne. Peter's protégés--Menshikov, Yaguzhinsky and Tolstoy--supported Catherine. The second group carried the day thanks to the brilliant oratory of Archbishop Feofan Prokopovich and the actions of General Ivan Buturlin, who stationed two guards regiments beneath the palace windows. Catherine was declared empress.

Royal Russia and Gilbert's Royal Books

© 2007

Eusebius in his Historia Ecclesiastica (vii 18) tells how at Caesarea Philippi lived the woman whom Christ healed of an issue of blood (Matt ix 20). Legend was not long in providing the woman of the Gospel with a name. In the West she was identified with Martha of Bethany; in the East she was called Berenike, or Beronike, the name appearing in as early a work as the Acta Pilati, the most ancient form of which goes back to the fourth century. It is interesting to note that the fanciful derivation of the name Veronica from the words Vera Icon (eikon) "true image" dates back to the "Otia Imperialia" of Gervase of Tilbury, who says: "Est ergo Veronica pictura Domini vera".

Source: Web Gallery of Art

Source: Art Renewal Center

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page

Streshnev on the rack:

"Tell me, am I your son or not?"

"The devil knows who you are;

The tsarina was often on her back!"

At even tide

When I seek haven

from my daily care

You'll find me by her side,

It seems so peaceful

there.

I kneel in my solitude

And silently pray,

That heav'n will

protect you dear,

And there'll come a day,

The storm will be over,

And that we'll

meet again,

AT THE SHRINE

OF SAINT CECILIA.