French Baroque Painter

1594 - 1665

Nicolas Poussin was a French painter in the classical style. His work predominantly features clarity, logic, and order, and favors line over color. Until the 20th century he remained the dominant inspiration for such classically oriented artists as Jacques-Louis David and Paul Cézanne.

He spent most of his working life in Rome except for a short period when Cardinal Richelieu ordered him back to France as First Painter to the King.

Nicolas Poussin's early biographer was his friend Giovanni Pietro Bellori, who relates that Poussin was born near Les Andelys in Normandy and that he received an education that included some Latin, which would stand him in good stead. Early sketches attracted the notice of Quentin Varin, a local painter, whose pupil Poussin became, until he ran away to Paris at the age of eighteen. There he entered the studios of the Flemish painter Ferdinand Elle and then of Georges Lallemand, both minor masters now remembered for having tutored Poussin. He found French art in a stage of transition: the old apprenticeship system was disturbed, and the academic training destined to supplant it was not yet established by Simon Vouet; but having met Courtois the mathematician, Poussin was fired by the study of his collection of engravings by Marcantonio Raimondi after Italian masters.

After two abortive attempts to reach Rome, he fell in with Giambattista Marino, the court poet to Marie de Medici, at Lyon. Marino employed him on illustrations to his poem Adone (untraced) and on a series of illustrations for a projected edition of Ovid's Metamorphoses, took him into his household, and in 1624 enabled Poussin (who had been detained by commissions in Lyon and Paris) to rejoin him at Rome.

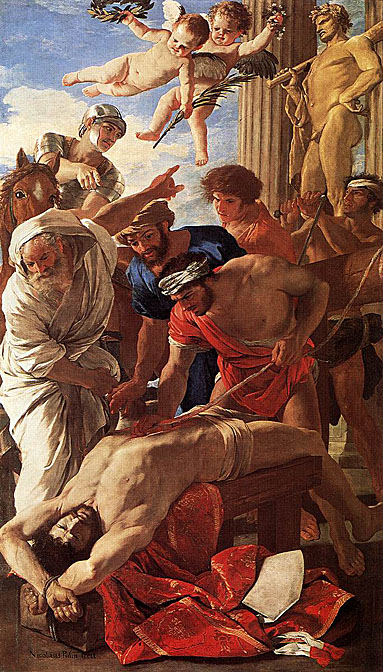

In Rome, his patron having died, Poussin, who lodged at first with Simon Vouet, fell into great distress, with the departure for Spain of his early patron Cardinal Francesco Barberini and the Cardinal's secretary, the antiquary Cassiano dal Pozzo, later a great friend and patron. The return of Barberini from Spain in 1626 stabilized and renewed the patronage of the Barberini and their circle. Two major commissions at this period resulted in Poussin's early masterwork the Barberini Death of Germanicus, partly inspired by the reliefs of the Meleager sarcophagus, and the commission for Saint Peter's that amounted to a public debut, the Martyrdom of Saint Erasmus (1630), with echoes of Pietro da Cortona. Falling ill at this time, he was received into the house of his compatriot Gaspard Dughet and nursed by his daughter Anna Maria to whom, in 1630, Poussin was married.

He lodged with the sculptor Francois Duquesnoy, of an equally classicizing artistic temperament, befriended Domenichino and joined an informal academy of artists and patrons opposed to the current Baroque style that formed around Joachim von Sandrart.

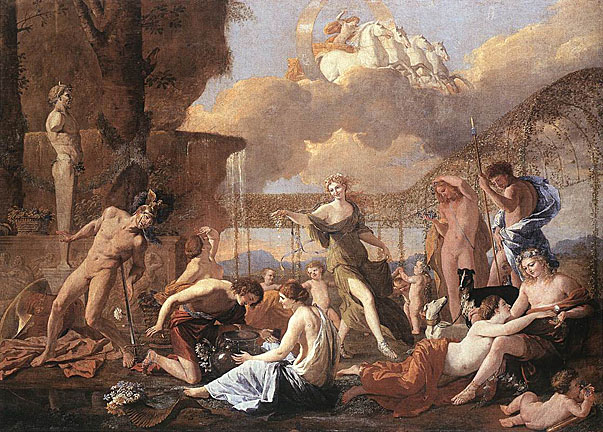

Among his first patrons, aside from Cardinal Francesco were: Cardinal Omodei, for whom he produced, in 1627, the Triumphs of Flora (Louvre); Cardinal de Richelieu, who commissioned a Bacchanal (Louvre); Vincenzo Giustiniani, for whom was executed the Massacre of the Innocents, of which there is a first sketch in the British Museum; Cassiano dal Pozzo, who became the owner of the first series of the Seven Sacraments (Belvoir Castle); and Paul Freart de Chantelou, with whom in 1640 Poussin, at the call of Sublet de Noyers, returned to France.

Louis XIII conferred on him the title of First Painter in Ordinary. In two years at Paris he produced several pictures for the royal chapels (the Last Supper, painted for Versailles, now in the Louvre), eight cartoons for the Gobelins tapestry manufactory, the series of the Labors of Hercules for the Louvre, the Triumph of Truth for Cardinal Richelieu (Louvre), and much minor work.

In 1643, disgusted by the intrigues of Simon Vouet, Fouquieres and the architect Jacques Lemercier, Poussin withdrew to Rome. There, in 1648, he finished for de Chantelou the second series of the Seven Sacraments (Bridgewater Gallery), and also his noble Landscape with Diogenes (Louvre). This painting shows the philosopher discarding his last worldly possession, his cup, after watching a man drink water by cupping his hands. In 1649 he painted the Vision of Saint Paul (Louvre) for the comic poet Paul Scarron, and in 1651 the Holy Family (Louvre) for the duc de Crequy. Year by year he continued to produce an enormous variety of works, many of which are included in the list given by Felibien.

He suffered from declining health after 1650, and was troubled by a worsening tremor in his hand, evidence of which is apparent in his late drawings. He died in Rome on November 19, 1665 and was buried in the church of San Lorenzo in Lucina, his wife having predeceased him. Chateaubriand in 1820 donated the monument to Poussin.

Poussin left no children, but he adopted as his son Gaspard Dughet (Gasparo Duche), his wife's brother, who became a painter and took the name of Poussin.

The mythological story of Apollo and Daphne:

The nymph Daphne, the daughter of the river god Peneus, was the first and most celebrated of Apollo's loves, and was popular with artists in all ages. According to Ovid, Cupid, in a spiteful mood, was the cause. He struck Apollo with a golden arrow, the sort that kindles love, Daphne with a leaden one that puts love to flight. The god pursued the unwilling girl, and, when she had no more strength to flee, she prayed to her father to save her. Whereupon branches sprouted from her arms, roots grew from her feet, and she was changed into a laurel tree.

The theme symbolizes the victory of Chastity over Love.

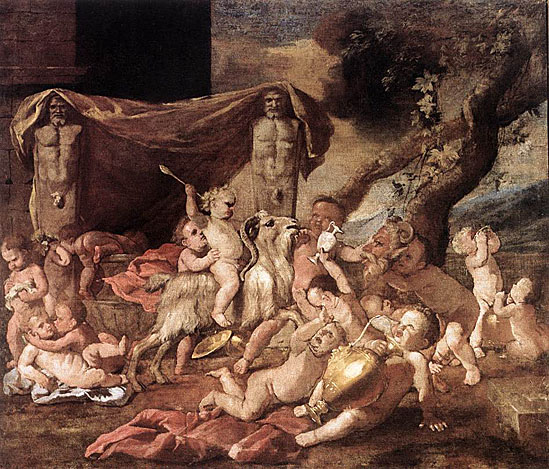

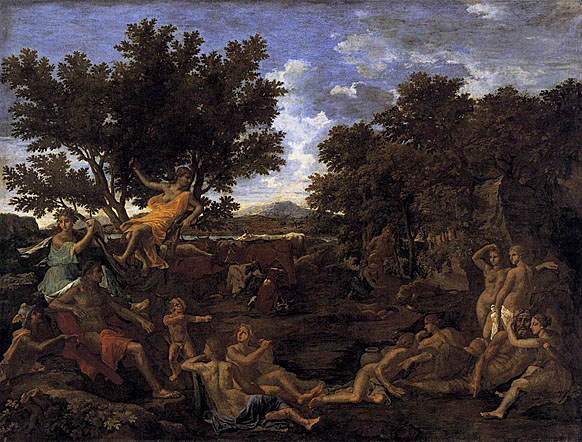

The execution of these two paintings fits perfectly with Poussin's interests and production during his first Roman years in Rome. Along with his colleagues Sandrart, Duquesnoy, Pietro da Cortona, Claude Lorrain and others, Poussin studied and drew from the Bacchanals of Titian at the Palazzo Aldobrandini and the Villa Ludovisi. Poussin actually copied certain details directly from Titian's famous Bacchanal of the Andrians, for example the "putto mingens" at the left of the larger picture. Other motifs echo the style of Poussin's fellow Frenchman Duquesnoy, with whom the painter shared Roman living quarters in 1626.

The Andrians were the inhabitants of the Aegean island of Andros, famous for its wine, and therefore a centre of the worship of Bacchus in antiquity. Legend told that the god visited the island annually when a fountain of water turned into wine.

In this representation Narcissus lies dead beside the water while Echo in the background grieves over him.

Midas is depicted penitently before Bacchus, a drunken Silenus sleeping nearby. Another version of the subject by Poussin (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) depicts Midas washing in the river, while the river god reclines on his urn.

The appearance of the muse Calliope has led to the suggestion that the picture was painted in honor of a recently dead poet.

Endymion, the beautiful youth who fell into an eternal sleep, has captured the imagination of poets and artists as a symbol of timelessness of beauty that is a 'joy forever.' Endymion, sent to sleep for ever by the command of Jupiter, in return for being granted perpetual youth, was visited nightly by the goddess. Poussin's painting shows Endymion awake, kneeling to welcome the arrival of the moon goddess, while her brother the sun-god is just beginning his journey across the heavens in his golden chariot.

This is one of the earliest paintings executed by Poussin in Rome. It was commissioned by the Sicilian nobleman Fabrizio Valguarnera.

Flora is the ancient Italian goddess of flowers. Her triumphal procession is led by Venus, Flora rides on a chariot drawn by putti.

The painting was inspired by the Bacchanal of Titian in the Villa Aldobrandini in Rome.

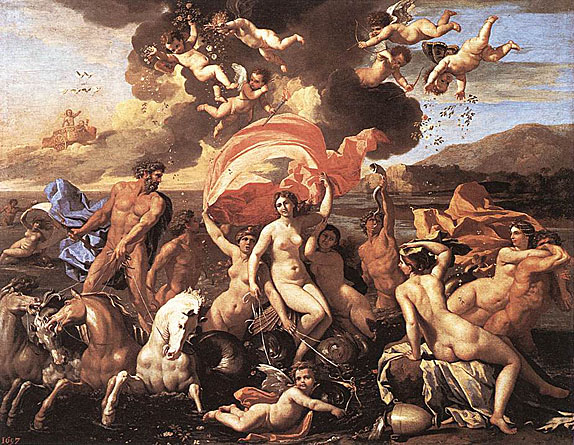

The mythological story :

Amphitrite fled from Neptune's wooing, but he sent dolphins after her which succeeded in persuading her to return to become his bride. She rides beside his chariot on a dolphin's back, an arch of drapery billows over her head, a common feature of sea-goddesses from antiquity. They are surrounded by a retinue of Tritons (the name for mermen in general) and Nereids (sea-nymphs, the daughters of Nereus, the 'old man of the sea' in Greek mythology).

The painting was probably painted for Cardinal Richelieu. It has been subject to widely differing interpretations.

Poussin's early period in Italy was barely easier than his years in Paris. As well as Raphael, engravings, statuary and a famous ancient wall-painting then in a princely collection, he studied Domenichino and Guido Reni and discovered Titian, whose Bacchus and Ariadne among other mythological scenes had just been brought to Rome from Ferrara. Not until he was about 35 did Poussin find his own voice, and patrons to heed it. From about 1630, with the exception of an unhappy interlude in Paris working for the king in 1640-2, he mainly painted smallish canvases for private collectors. Out of his very limitations, he created a new kind of art: the domestic 'history painting' with full-length but small-scale figures, for the edification and delight of the few. Seldom has a painter been more intense, more serious and, in the event, more influential.

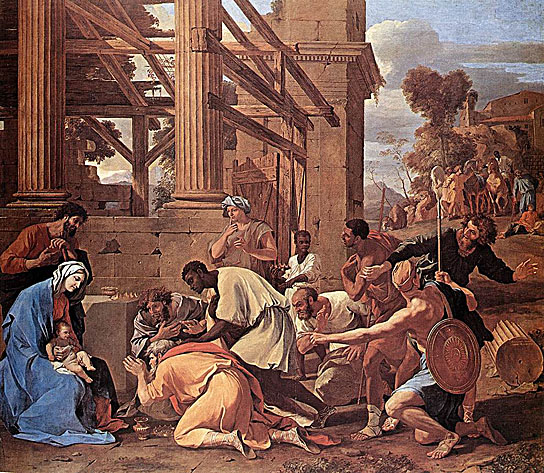

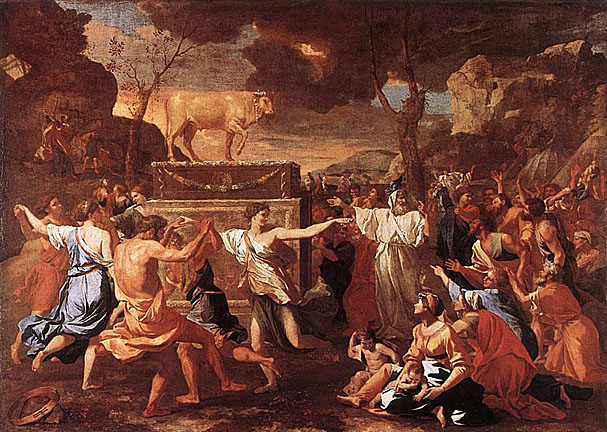

The Adoration of the Golden Calf was originally paired with the Crossing of the Red Sea now in Melbourne. Both illustrate episodes from Exodus in the Old Testament; this painting relates to chapter 32. In the wilderness of Sinai the children of Israel, disheartened by Moses' long absence, asked Aaron to make them gods to lead them. Having collected all their gold earrings, Aaron melted them down into the shape of a calf, which they worshipped. In the background on the left Moses and Joshua come down from Mount Sinai with the tablets of the Ten Commandments. Hearing singing and seeing 'the calf and the dancing...Moses' anger waxed hot, and he cast the tablets out of his hands, and brake them beneath the mount.' The tall bearded figure in white is Aaron still 'making proclamation' of a feast to the false god.

Poussin is said to have made little figures of clay to use as models, and the story is confirmed by the dancers in the foreground. They are a mirror image of a pagan group of nymphs and satyrs carousing in Poussin's earlier Bacchanalian Revel also in the National Gallery. Within a majestic landscape painted in the bold colors Poussin learned from Titian, before a huge golden idol more bull than calf (and many earrings' worth), these Israelite revelers give homage to the potency of Poussin's vision of antiquity. As on a sculpted relief or painted Greek vase, figures are shown in suspended animation, heightened gestures or movements isolated from those of their neighbors, so that the effect of the whole is at one and the same time violent and static.

Ovid tells of the palace of Helios and his retinue - Day, Month, Year, and the Four Seasons and so on. Here Phaeton presented himself and persuaded an unwilling father to allow him for one day to drive his chariot across the skies. The Hours yoked the team of four horses to the golden car, Dawn threw open her doors, and Phaeton was off. Because he had no skill he was soon in trouble, and the climax came when he met the fearful Scorpion of the zodiac. He dropped the reins; the horses bolted and caused the earth itself to catch fire. In the nick of time Jupiter, father of the goods, put a stop to his escapade with a thunderbolt which wrecked the chariot and sent Phaeton hurtling down in flames into the River Eridanus. He was buried by nymphs. Phaetons's reckless attempt to drive his father's chariot made him the symbol of all who aspire to that which lies beyond their capabilities.

On the painting the sun-god, having Apollo's appearance and attributes, sits on a cloudy throne framed in the zodiacal belt, a lyre beside him; Phaeton kneels in front of him.

The Cabinet de la Chambre du Roy in Richelieu's château celebrated the cardinal's 'gift' to Louis XIII of mastery of the seas. The room, with its 'Combat of Wealth and Art', as a contemporary panegyric puts it, and furnished in addition to paintings and paneling with porphyry vases and ancient busts, must have presented a formidable challenge to Poussin. Not only would he be competing with some of the foremost Italian Renaissance artists, his pictures also had to contend with the glittering decor - hence the colors here are among the most brilliant he ever lavished on a painting. Sadly, the room was dismantled long ago and the pictures dispersed, so we can judge the full effect only in our mind's eye.

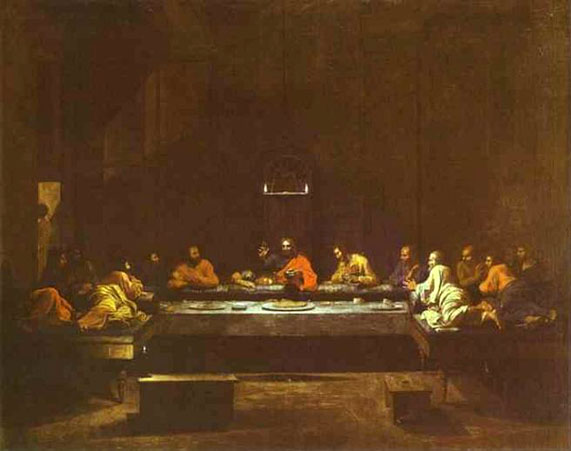

Poussin carefully allowed for the spectator's point of view. Nimble visitors to the Gallery can sit on the floor to look at this picture in order better to appreciate its spatial construction, and thus its full significance. The revelers occupy a raised stage extending back to where rocks and vine-hung trees screen off the backdrop of sky and distant mountains. Propped up vertically against this earthen stage are a timbrel and two masks - an ancient satyr mask and a modern Italian Columbine. Behind them a Punchinello mask joins a still life drawn from the imagery of ancient bacchanals: thyrsoi - staffs wreathed with ivy and surmounted by pine cones - the crooked stick and pipes of Pan, wine in a metal bowl or crater, and a Greek wine jar showing the god Dionysus, the Roman Bacchus.

The composition is indebted to an engraving after Giulio Romano, a pupil of Raphael, but Poussin also demonstrates his first-hand access to antiquarian lore. The mixture of modern and ancient masks, and the stage-like construction, allude to the origins of theatre in bacchic rites. The main scene represents the 'triumph' or worship of the armless bust of a horned deity mounted on a pillar, his face smeared red with the juice of boiled ivy stems. This is the 'term' of Pan, Arcadian god of shepherds and herdsmen, and Priapus, a phallic god of fertility, protector of gardens, whose cult was imported into Greece from the Near East. Confused with each other, both were associated with Dionysus/Bacchus: Dionysus, god of the grape-vine, who died, descended into Hades then rose again was himself identified with seasonal decay and rebirth. All the participants are members of his entourage (as we find them in Titian's Bacchus and Ariadne): nymphs and their lewd playmates the satyrs; maenads who rend deer limb from limb or strew flowers from the winnowing basket sacred to Dionysus. A world of pagan imaginings is brought to life in all its cruel and seductive charm, without a hint of anachronistic moralizing.

The rejection of Venetian coloring, the sharper modeling, and the evolution of a composition based on carefully balanced movements are apparent in a small group of works which must be dated about 1637, of which the exquisite Nurture of Jupiter is typical.

Jupiter was the son of Saturn, the god who devoured his children because it was prophesied that one of them would usurp him. Jupiter's mother fled to Crete where she gave birth to him in a cave. She gave Saturn a large stone wrapped in swaddling clothes which he unsuspectingly swallowed instead. Jupiter was brought up on the slopes of Cretan Mount Ida by nymphs who fed him on wild honey and on milk from the goat Amalthea.

In this representation of the subject the goat suckles Jupiter.

In the painting of Poussin, a nymph has Jupiter in her arms, holding a jug of milk to his lips, while another gathers honeycombs, and a shepherd milks the goat.

The story of Pan and Syrinx is told by Ovid. Pan was pursuing a nymph of Arcadia named Syrinx when they reached the river Ladon which blocked her escape. To avoid the god's clutches she prayed to be transformed, and Pan unexpectedly found himself holding an armful of tall reeds. The sound of the wind blowing through them so pleased him that he cut some and made a set of pipes which are named after the nymph.

Poussin chooses the moment in which Pan has almost caught the fleeing nymph: but movement becomes posing, time stands still, and Syrinx escapes through her transformation. Despite the terpsichorean harmony of the two, their contrary desires are convincingly written into their figures: the joyous yearning and onwards urge of Pan, and Syrinx's timid wish to preserve herself. The sensual vitality of the shepherd-god and the chaste beauty of the nymph are also clearly characterized by the artist's choice of colors: Pan, a reddish brown, and Syrinx pale in color.

Flying above the pair is Cupid as a winged boy holding a torch and a lead-tipped arrow, which he is about to cast at Syrinx. Ovid tells us that Cupid had various arrow-tips: a golden tip awakened love, while that of lead had the opposite effect.

The dramatic events of the pursuit and the transformation take place within a landscape suffused with light; a light which, with its delicate, atmospheric sfumato, would have been more fitting for an idyll than this dramatic scene. The putti at the bottom of the picture cast themselves aside in fright. The tree trunk on the far right has been painted over Pan's hoof. Evidently Poussin added the tree at a later stage, to produce greater articulation in the picture's spatial structure.

The river-god Ladon checks the two central protagonists, allowing the picture's suspense and dynamism to culminate at its centre. His face, reminiscent of that of the Antique sculpture of Laocoon in his death throes, seems to bear the ineluctable suffering of Antique tragedies, with a depth and emotion that goes beyond all human contingency. From the moment of its discovery in 1506 in Rome, the Hellenistic sculpture of the Trojan priest and his sons entwined by serpents awoke the especial interest of artists, for it showed a restrained formulation of agonizing death that was valid for all time.

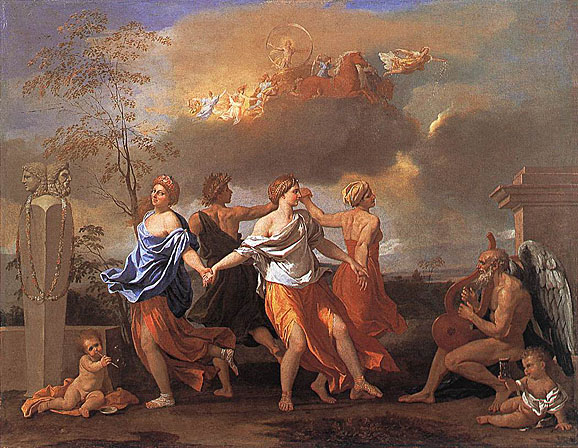

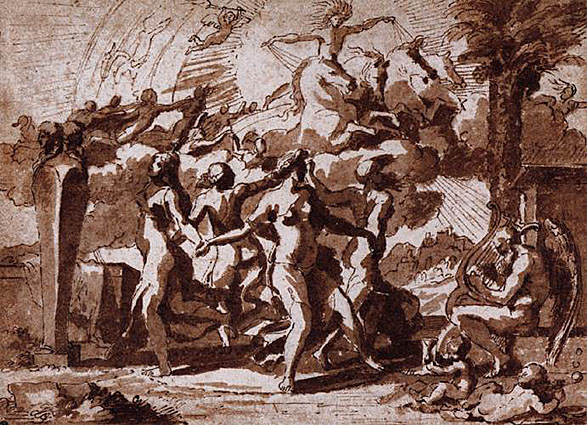

For Poussin drawing was a practical necessity, rather than a source of delight; this is, however, one of his most appealing studies, in which the sensual figures are defined as slightly abstracted forms, consistently lit from the upper left, as they appear to cavort upon a stage. In the painting the composition becomes more austere and measured. The title now used for it is a creation of the twentieth century, and has become widely known as it was adopted for a famous series of novels by Anthony Powell.

In the hands of Poussin who made two versions the sense was gradually modified. Shepherds are seen before a tomb deciphering the inscription with an air of melancholy curiosity. The skull is no longer significant or is omitted. The words now seem to imply an epitaph on the person - perhaps a shepherdess - who lies entombed: 'I too once lived in Arcady', an alteration to the meaning that somewhat stretches the grammar of the original Latin.

In this version all sense of surprise has been removed, and instead, the shepherds are arranged in attitudes of contemplation round the tomb in the countryside. The artist has lost all interest in story-telling, and has concentrated on a totally static scene. No pleasure is taken in surface texture, and the whole is hard and cold, with the figures in statuesque poses.

The other, less severe version of the subject by Poussin is at Chatsworth.

Almost as soon as he arrived in Rome, Poussin was fortunate enough to come into contact with the scholarly and benevolent Cassiano dal Pozzo, who was to be his patron for the next thirty years until his death in 1657. Their relationship in its early years seems to have consisted mainly of Pozzo collecting a number of Poussin's first works, almost out of charity for the struggling young artist, as the pictures were indeed of modest pretensions. In the later 1630's the catalyst for a development towards an extreme was undoubtedly Cassiano dal Pozzo, who commissioned Poussin to paint his first set of Sacraments.

The dates of execution for this first set are unknown, but they were not completed until 1642, when the final one was sent by Poussin from Paris to Rome. Cassiano owned a Poussin executed in the late 1630's, a 'Baptism of Christ' now in the Getty Museum at Malibu, and it may well have been this carefully calculated composition which spurred Cassiano on to commission Poussin to create the Sacraments, one of the most important single commissions of his career. The seven pictures, though executed over several years, were intended to be seen together, presumably in a relatively small room. Five of them - Marriage, Extreme Unction, Confirmation, Ordination and Eucharist - are now at Belvoir Castle, Leicestershire, hung in different places in the house; the sixth, Baptism, is in the National Gallery of Art, Washington; and the seventh, Penance, was lost in the fire which destroyed Belvoir in 1816. It is difficult to know whether Poussin worked out his artistic theories after he had solved his problems on canvas, or whether he thought in the abstract and tried to prove his point by painting to a chosen formula. Whatever the explanation, the result was an extremely cerebral approach, epitomized by this first set of Sacraments.

In spite of his great rigidity of theory, and in spite of some very dry pictures in which there seems to be little feeling of any kind, a surprisingly large number of Poussin's best pictures are tense with emotion. This is nowhere better seen than in the first set of Sacraments: it is as if all Poussin's energies and ideas are concentrated in these relatively small canvasses.

The Sacraments, a microcosm of Poussin's art, reveal his working methods. It is known that he kept a small box rather like a miniature theatre, in which he arranged wax models and altered the lighting in order to help him with the layout of his complex compositions. He then made numerous rough drawings, trying out the compositions until the final solution was reached. It is easy to see that all the interior scenes of the Sacraments are arranged like a theatrical tableau, which gives them their curiously static quality and enhances their gravity.

In the Berlin painting Poussin has introduced realistic impressions of nature, deriving ostensibly from the Tiber valley at Aqua Acetosa not far from Rome. But there is no question of an exact reproduction of the topographical features, such as the North European artists in Italy so often tried to achieve. As in all Poussin's works, the composition here is essentially imaginative: the double bend of the river conveys the full depth of the valley, while the soaring tower of a distant ruin is the dominant vertical feature of the landscape, lending emphasis to the quiet dialogue between Evangelist and angel; his own features shaded, Matthew looks up at the divine messenger who stands bathed in a bright light. The remains of the building material, stones cut in cubic and cylindrical forms, not only provide depth and perspective but also lend a note of gravity to this heroic landscape, and are so placed as to achieve the maximum artistic effect.

At the end of the eighteenth century this painting formed part of a legacy to the Colonna di Sciarra family, and its presence in their palazzo was confirmed in 1820. In 1873 it was acquired for the Berlin Gallery.

The subject was borrowed from "Metamorphoses" by Ovid. A terrible one-eyed giant Polyphemus enamored of nymph Galathea is singing of his love on a pipe.

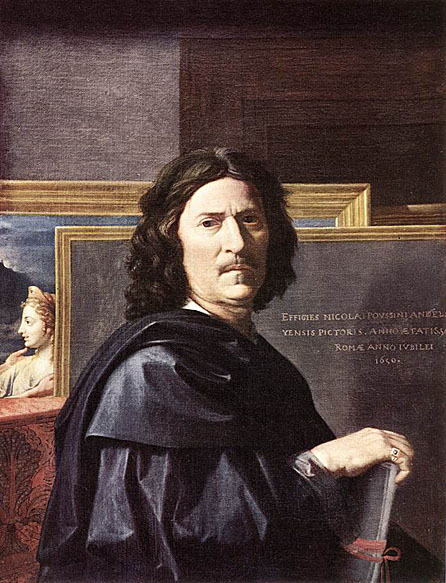

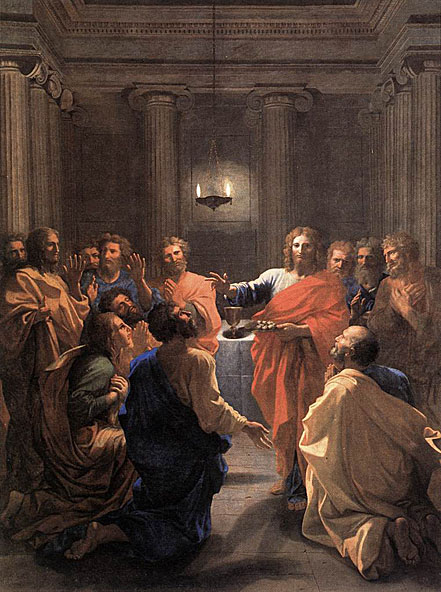

The second series of Sacraments have a solemnity wholly lacking in the more picturesque first series. This is perhaps most apparent in the Eucharist, one of Poussin's most severe compositions. The scene is set in a room of the utmost simplicity, without ornament, and articulated only with plain Doric pilasters. The Apostles are shown lying on couches round the table and are dressed in Roman togas. The artist has chosen a moment which enables him to combine the two main themes which the subject involves: the dramatic and the sacramental. Christ has given the bread to the apostles and is about to bless the cup, but on the left of the composition we see the figure of Judas leaving the room. That is to say, Poussin represents primarily the institution of the Eucharist, but at the same time reminds the spectator of Christ's words: 'One of you shall betray me'. The double theme is made even clearer in the actions of the apostles, which are defined with great precision. Some are engaged in eating the bread; others show their realization of the significance of what is taking place by gestures of astonishment, while Saint John's expression of sorrow shows that he is thinking of Christ's words about Judas.

Formally Poussin has concentrated his group into a symmetrical relief pattern. His choice of a low view-point has enabled him to foreshorten the front apostles, so that they form a compact group with those on the other side of the table.

In this picture a drama is taking place, but it is not immediately apparent. It was Poussin's aim to bring about this realization slowly in the spectator, through contemplation. A man lies dead in the foreground in the coils of a snake, and another man has come across the spectacle and is fleeing in terror. In the background a woman reacts to the terror of the man in flight, and in turn her reaction is noticed by a fisherman. Poussin has depicted a series of emotions in this extensive panorama which is painted in dense blues, greens and browns. The gloom of the scene is intended to provoke the spectator to contemplate the triumph of nature over man.

The painting probably was painted for one of Poussin's main patrons, Pointel.

Orpheus is a legendary Thracian poet, famous for his skill with the lyre. He married Eurydice, a wood nymph, and at her death descended into the underworld in an unsuccessful attempt to bring her back to earth.

The biblical story depicted:

The patriarch Abraham, wishing to find a wife for his son Isaac, sent his servant Eliezer, to look for a suitable bride among his own kindred in Mesopotamia, rather than among the people of Canaan where he lived. When the servant reached the city of Nahor in Chaldea he prayed for guidance, asking that whoever gave him and his camels water at the well would be an eligible woman. This proved to be Rebecca, a virgin, one of the family of Abraham through his brother Nahor. She invited Eliezer to drink from her jar, and drew water for his camels. Eliezer gave his presents of gold and received hospitality at her parents' house. He then took her back to Canaan.

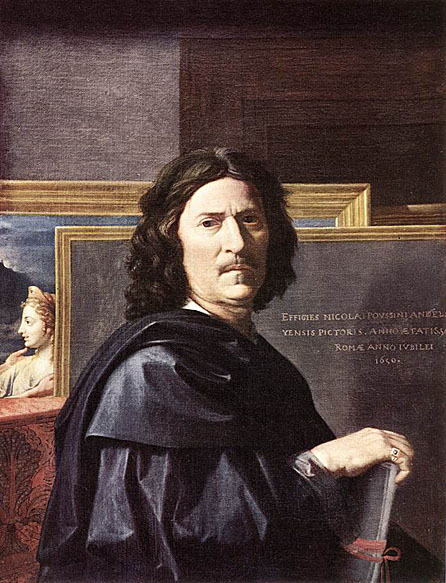

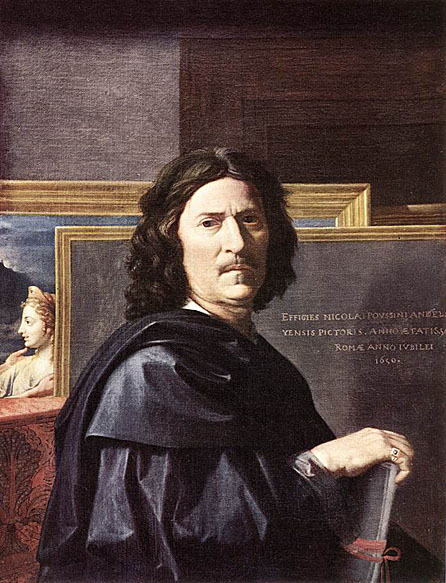

The most conspicuous motif of the earlier self-portrait is the "memento mori". The artist present himself before a sepulchral monument - anticipating his own - flanked by putti; the expression on his face is almost cheerful. Viewed from a distance he appears to be smiling, while his head, inclined slightly to one side, suggest a melancholic mood. Cheerfulness in the face of death demonstrated the composure of the Stoics, a philosophy for which Poussin had some sympathy.

According to the biblical story Solomon was called upon to judge between the claims of two prostitutes who dwelt in one house, each of whom had given birth to a child at the same time. One infant had died and each woman then claimed that the other belonged to her. To determine the truth the king ordered a sword to be brought, saying, 'Cut the living child in two and give half to one and half to the other.' At this, the true mother revealed herself by renouncing her claim to the child in order that its life might be spared. The child was restored to her.

The scene, widely depicted in Christian art, shows Solomon on his throne, the two suppliant women before him. An executioner stands holding the living child aloft in one hand, with a sword in the other. The dead child lies in the hand of one of the women. The subject was made to prefigure the 'Last Judgment', and came to be used as a symbol of Justice in a wider sense.

There are many preparatory drawings to this painting in various French museums.

A tiny but highly significant detail is the ring Poussin is wearing on the little finger of his right hand, which rests on a fastened portfolio. The stone is cut in a four-sided pyramid. As an emblematic motif, this symbolized the Stoic notion of Constantia, or stability and strength of character.

The painting is signed and dated: EFFIGIES NICOLAI POUSSINI ANDELYENSIS PICTORIS, ANNO AETATIS 56. ROMAE ANNO JUBILEI 1650.

This painting is one of the few large-scale works of the master. It depicts the story of Pyramus and Thisbe as Ovid tells in Metamorphoses. The lovers, forbidden by their parents to marry, planned to meet in secret one night beside a spring. Thisbe arrived first but as she waited a lioness, fresh from a kill, came to quench its thirst, its jaws dripping blood. Thisbe fled, in her haste dropping her cloak which the beast proceeded to tear to shreds. When Pyramus arrived and discovered the bloody garment he believed the worst. Blaming himself for his lover's supposed death he plunged his sword into his side. Thisbe returned to find her lover dying and so, taking his sword, threw herself upon it. This story became widely popular in post-Renaissance painting.

From Early Christian times the Old Testament was read by Christians for its analogies with the New. Thus the waters of the Nile to which the infant Moses is consigned by his mother in 'an ark of bulrushes', following Pharaoh's cruel order to drown all the male Israelite babies (Exodus 1:2), were likened to the waters of baptism. But Poussin's interest in Moses may have been prompted also by his identification with pagan deities; as a contemporary writer influenced by these ideas wrote of this picture: 'He is Moses, the Mosche of the Hebrews, the Pan of the Arcadians, the Priapus of the Hellespont, the Anubis of the Egyptians.'

All these ideas reverberate throughout the painting. The baby on whom Pharaoh's daughter has taken pity resembles the Christ Child blessing the Magi or the shepherds in a scene of the Adoration. In the background on the left an Egyptian priest worships the dog-shaped god Anubis (barely visible now that the surface paint has grown thin and transparent). We know we are in Egypt because on the rock above the main scene a river god, symbolizing the Nile, embraces a sphinx, palm trees stand on the shore and an obelisk rises up behind a stately temple. (Curiously, the many-windowed buildings with which Poussin, who had never been there, endows Pharaoh's country now resemble modern resort hotels.)

The main interest and beauty of the painting, however, do not reside in its possible symbolism, but in the wonderful grouping of the figures, all women to contrast with an analogous group of men in 'Christ healing the Blind Man' (now in the Louvre), painted for the same patron the year before. Each plays her role in the dramatic tale, the princess generous and commanding, and the maids curious and delighted. The humbler figure in a white shift at Moses' head may be his sister who watched from nearby to see what would happen to him, and recommended their mother to Pharaoh's daughter as a wet nurse. It is tempting to see their brilliant draperies as a compliment to Poussin's patron, the Lyon silk merchant Reynon. Bodies and color each distinct and separate combine in ample rhythms across the picture surface, echoed by the rocks beyond. It is at once solemn and joyful, as befits a scene in which a child is rescued from death, and through him an entire people is saved.

The change is in the completely different handling of paint, which shows his preoccupation with surface texture, and a relaxation of mood. His sense of severity and order has disappeared and been replaced by a mood much more akin to the last works of Titian, such as the Diana and Actaeon in the National Gallery, London. In the New York picture the forms are less rigid than previously, and there is a return to the sense of rhythm last seen in his work of the 1630's. The landscape becomes a much more sensual interpretation of such types of painting as the Diogenes.

In Greek mythology Orion was a hunter of gigantic stature. Drunk with wine he once tried to rape a princess of Chios, but her father punished Orion by blinding him. An oracle told him to travel east to the furthest edge of the world where the rays of the rising sun would heal his sight. On his journey he passed the forge of Vulcan whence he carried off an apprentice named Cedalion to guide him on his way. In due course Orion's sight was restored.

Poussin shows the giant, bow in hand, striding through a wooded countryside towards a distant sea. Cedalion perches on his shoulders. Vulcan stands at the roadside pointing out the way. A cloud, wafting round Orion's face, suggests that his sight is veiled. Another myth tells how Orion eventually died at the hand of Diana who set his image among the stars. She is seen floating above him.

The biblical story depicted in Summer:

Ruth was a Moabite woman and great-grandmother of David, and therefore an ancestress of Christ, hence her place in Christina art. She was married to a Hebrew immigrant in Moab and after his death left her native land and went with her mother-in-law Naomi, to Bethlehem. Here she was allowed to glean the corn in the fields belonging to Boaz, a rich farmer and kinsman of Naomi. Ruth, true to her nature, maintained, on Naomi's advice, a modest demeanor among the young men working at the harvest. One night she went and lay at the feet of Boaz as he slept in the field. By this act Boaz saw her virtue and later decided to assume responsibilities towards her of a kinsman. In due course he married her.

These pictures exist on a complex series of levels, and even the most unscholarly spectator must be aware that Poussin was trying to balance moods and ideas in a much more subtle and intricate way than usual. Firstly, the pictures are a sequence, and they are hung in this way in the Grande Galerie of the Louvre. Spring is cool in tone, Summer and Autumn are warm, and Winter is cold. Even this obvious modulation of tones has its own rhythm. In all but Winter man is seen in harmony with nature, especially in Spring, surely one of the most perfect evocations of Paradise since the subject was attempted by fifteenth-century Netherlands' painters.

Source: Web Gallery of Art

Source: Art Renewal Center

Return to Pagina Artis