French Neoclassical Painter and Draftsman

1748 - 1825

David later became an active supporter of the French Revolution and friend of Maximilien Robespierre, and was effectively a dictator of the arts under the French Republic. Imprisoned after Robespierre's fall from power, he aligned himself with yet another political regime upon his release, that of Napoleon I. It was at this time that he developed his 'Empire style', notable for its use of warm Venetian colors. David had a huge number of pupils, making him the strongest influence in French art of the 19th century, especially academic Salon painting.

Jacques-Louis David was born into a prosperous family in Paris on August 30, 1748. When he was about nine his father was killed in a duel and his mother left him with his prosperous architect uncles. They saw to it that he received an excellent education at the Collège des Quatre-Nations, but he was never a good student: he had a facial tumor that impeded his speech, and he was always preoccupied with drawing. He covered his notebooks with drawings, and he once said, "I was always hiding behind the instructor's chair, drawing for the duration of the class". Soon, he desired to be a painter, but his uncles and mother wanted him to be an architect. He overcame the opposition, and went to learn from François Boucher, the leading painter of the time, who was also a distant relative. Boucher was a Rococo painter, but tastes were changing, and the fashion for Rococo was giving way to a more classical style. Boucher decided that instead of taking over David's tutelage, he would send David to his friend Joseph-Marie Vien, painter who embraced the classical reaction to Rococo. There David attended the Royal Academy, based in what is now the Louvre.

David attempted to win the Prix de Rome, an art scholarship to the French Academy in Rome, four times between 1770 and 1774; once, he lost according to legend because he had not consulted Vien, one of the judges. Another time, he lost because a few other students had been competing for years, and Vien felt David's education could wait for these other mediocre painters. In protest, he attempted to starve himself to death. Finally, in 1774, David won the Prix de Rome. Normally, he would have had to attend another school before attending the Academy in Rome, but Vien's influence kept him out of it. He went to Italy with Vien in 1775, as Vien had been appointed director of the French Academy at Rome. While in Italy, David observed the Italian masterpieces and the ruins of ancient Rome. David filled twelve sketchbooks with material that he would derive from for the rest of his life. While in Rome, he studied great masters, and came to favor above all others Raphael. In 1779, David was able to see the ruins of Pompeii, and was filled with wonder. After this, he sought to revolutionize the art world with the "eternal" concepts of classicism.

David's fellow students at the academy found him difficult to get along with, but they recognized his genius. David was allowed to stay at the French Academy in Rome for an extra year, but after 5 years in Rome, he returned to Paris. There, he found people ready to use their influence for him, and he was made a member of the Royal Academy. He sent the Academy two paintings, and both were included in the Salon of 1781, a high honor. He was praised by his famous contemporary painters, but the administration of the Royal Academy was very hostile to this young upstart. After the Salon, the King granted David lodging in the Louvre, an ancient and much desired privilege of great artists. When the contractor of the King's buildings, M. Pecol, was arranging with David, he asked the artist to marry his daughter, Marguerite Charlotte. This marriage brought him money and eventually four children. David had his own pupils, about 40 to 50, and was commissioned by the government to paint "Horace defended by his Father", but Jacques soon decided, "Only in Rome can I paint Romans." His father in law provided the money he needed for the trip, and David headed for Rome with his wife and three of his students, one of whom, Jean-Germain Drouais, was the Prix de Rome winner of that year.

In Rome, David painted his famous Oath of the Horatii, 1784. In this piece, the artist references Enlightenment values while alluding to Rousseau's social contract. The republican ideal of the general will becomes the focus of the painting with all three sons positioned in compliance with the father. The Oath between the characters can be read as an act of unification of men to the binding of the state. The issue of gender roles also becomes apparent in this piece, as the women in Horatii greatly contrast the group of brothers. David depicts the father with his back to the women, shutting them out of the oath making ritual; they also appear to be smaller in scale than the male figures. The masculine virility and discipline displayed by the men's rigid and confident stances is also severely contrasted to the slouching, swooning female softness created in the other half of the composition. Here we see the clear division of male-female attributes which confined the sexes to specific roles, under Rousseau's popular doctrines.

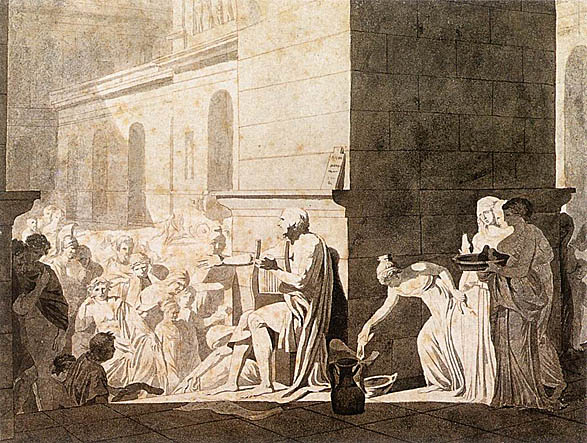

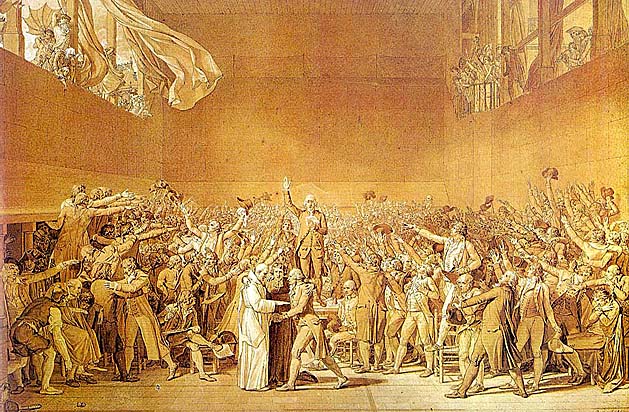

These themes and motifs would carry on into his later works Oath of the Tennis Court, 1791. This piece, although remaining unfinished, was to commemorate the National Assembly's resolve to take a solemn oath never to disband until the constitution was established and protected; the commitment to self-sacrifice for the republic. Commissioned by the Society of Friends of the Constitution, David set out in 1790, to transform the contemporary event into a major historical picture, which would appear at the Salon of 1791 as a large pen and ink drawing. As in the Oath of the Horatii, David represents the unity of men in the service of a patriotic ideal. What was essentially an act of intellect and reason, David creates with great drama in this work. The very power of the people appears to be "blowing" through the scene with the stormy weather, in a sense alluding to the storm that would be the revolution.

These revolutionary ideals are also apparent in the Distribution of Eagles. While Oath of the Horatii and Oath of the Tennis Court stress the importance of masculine self-sacrifice for one's country and patriotism, the Distribution of Eagles would ask for self-sacrifice for one's Emperor (Napoleon) and the importance of battlefield glory.

In 1787, David did not become the Director of the French Academy in Rome, which was a position he wanted dearly. The Count in charge of the appointments said David was too young, but said he would support him in 6 to 12 years. This situation would be one of many that would cause him to lash out at the Academy in years to come.

For the salon of 1787, David exhibited his famous Death of Socrates.

Critics compared the Socrates with Michelangelo's Sistine Ceiling and Raphael's Stanze, and one, after ten visits to the Salon, described it as "in every sense perfect". Denis Diderot said it looked like he copied it from some ancient bas-relief. The painting was very much in tune with the political climate at the time. For this painting, David was not honored by a royal "works of encouragement".

For his next painting, David created The Lictors Bring to Brutus the Bodies of His Sons. The work had tremendous appeal for the time. Before the opening of the Salon, the French Revolution had begun. The National Assembly had been established, and the Bastille had fallen. The royal court did not want propaganda agitating the people, so all paintings had to be checked before being hung. David's portrait of Lavoisier, who was a chemist and physicist as well as an active member of the Jacobin party, was banned by the authorities for such reasons. When the newspapers reported that the government had not allowed the showing of The Lictors Bring to Brutus the Bodies of His Sons, the people were outraged, and the royals were forced to give in. The painting was hung in the exhibition, protected by art students. The painting depicts Lucius Junius Brutus, the Roman leader, grieving for his sons. Brutus' sons had attempted to overthrow the government and restore the monarchy, so the father ordered their death to maintain the republic. Thus, Brutus was the heroic defender of the republic, at the cost of his own family. On the right, the Mother holds her two daughters, and the grandmother is seen on the far right, in anguish. Brutus sits on the left, alone, brooding, but knowing what he did was best for his country. The whole painting was a Republican symbol, and obviously had immense meaning during these times in France.

The work stresses Andromache's nobility and courage in accepting this cruel fate. The colors are bold, but somehow still subordinate to the central message. All other figures have been removed, so that Troy's coming tragedy, now that her city's key hero has been killed, is somehow encapsulated into the moving drama of this one family.

The light leads the viewer to the face of Andromache, who is as exstatic with pain as Bernini's famous Theresa is ecstatic with faith. Her open right hand lies on the dea man's side and she pays little attention to her small son Astyanax, whose left hand reaches for her face. So many hands and arms linked to one another in a spiral with so many creases and folds. The little boy is particularly well painted, and is of one of David's pupils, Hennequin.

The painting shows a scene - Belisarius is recognized by one of the soldiers who served under him just as he receives alms from a woman - which is David's own invention, not having occurred in any of the written sources. This painting was the first fully resolved example of the new heroic and austere style that is now known as Neoclassicism. it is a picture with a serious subject that is painted in a sober and rational style. Few characters, set as if on a stage, exchange meaningful and easily understood gestures. Belisarius is a painting about charity, sympathy, dutiful patriotism and the reversal of fortune. Announcing the old man desperate situation, and appealing to the spectator's charitable sensibilities, the Latin inscription 'Date Obulum Belisario' (Give an obulus - an ancient Greek silver coin - to Belisarius) is displayed on the marker stone in the bottom right-hand corner.

In this painting David contrasted the violence of the rape with the pacification of the intervention. The image of family conflict in the Sabines was a metaphor of the revolutionary process which had now culminated in peace and reconciliation. The painting was a tribute to Madame David, and a recognition of the power of women as peacemakers.

In this painting David also deals with the subject of death in service of the state. This was an inflammatory subject in 1789, speaking out for self-sacrifice, the sacrifice of one's own flesh and blood for a higher ideal.

Lucius Junius Brutus (not to be confused with Julius Caesar's assassin Marcus Brutus, who lived some 500 years later), had helped to rid Rome of the last of its kings, the tyrannical Tarquin the Proud. This came about because Tarquin's son Sextus had raped the virtuous Lucretia. She then committed suicide in the presence of both her husband Collatinus and Brutus, who withdraw the knife from the fatal wound and swore on Lucretia's blood to avenge her death and destroy the corrupt monarchy. Tarquin was exiled and the first Roman Republic was established in 508 BC, with Brutus and Collatinus elected as co-consuls. As the picture title tells us, Brutus' two sons, Titus and Tiberius, were drawn into a royalist conspiracy to return Tarquin, and their father condemned them to death.

For the grim and terrible event depicted in the painting, David adopted a radical compositional format. The main character, Brutus, is placed at the extreme left, plunged into deep shadow. His body is tense and knotted as he broods over the consequences of his act; he grasps the death warrant and clenches his feet one across the other. This last detail, in addition to the position of his arms, was probably taken from the figure of the prophet Isaiah on the Sistine Chapel Ceiling by Michelangelo. For the sake of accuracy David based the features of Brutus on a famous antique bust, the so-called Capitoline Brutus, of which he owned a copy. On the other side of the image the inconsolable women are brightly illuminated. The center of the picture is taken up by a still-life of a sewing basket, an emblem of domesticity, which is rendered in stark clarity.

David skillfully illuminated the grief and allegorized the suffering, fear and pain of his figures. He shows the mother, accusing and suffering, her daughter beside her, hands raised defensively, and finally the younger daughter sunk down in pain at her impotence. Another figure at the right edge of the painting personifies grief. In the shadow sits the "hero" with the dark mien of a thinker. His features are stoic and harsh, his left hand is holding the written accusation in a claw-like grip, and he is seated in the shadow of the Roma, the symbol of the state to which the sacrifice is ultimately being made. Behind him, the son whose life has fallen victim to the requirements of the state is being borne in. A column strictly divides the theatrical arrangement into the representation of the dark force of destiny and the obvious emotional effect of the event.

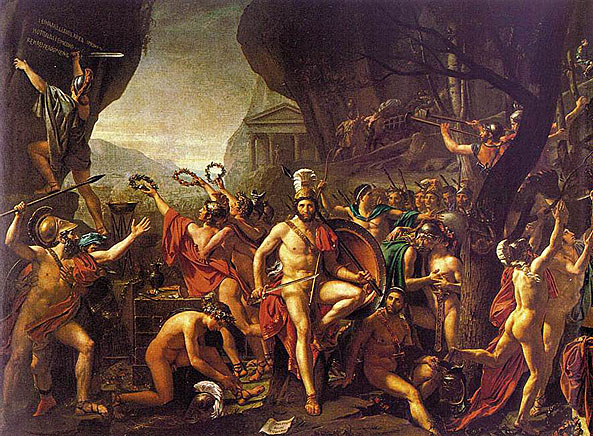

The subject concerns Leonidas, King of Sparta, who in 480 BC held the pass at Thermopylae against the invading Persian army of Xerxes. Vastly outnumbered, Leonidas and his 300 handpicked volunteers were killed, but only after their heroic defense had ensured the safe retreat of the Greek fleet.

In the final painting, as the sentinel trumpeters sound the call to arms, on the right two soldiers rush to gather their weapons that are hanging from the branches of an oak tree. Leonidas sits on a rock facing out at the viewer, contemplating his and his soldiers' fate. Seated at his right is Agis, his wife's brother, who looks to his commander for orders. To emphasize the fervent patriotism of the Spartans, David once again includes an oath, and behind Leonidas three young soldiers lift up wreaths above two altars dedicated to Hercules and Aphrodite.

On either side of Leonidas are two very young warriors, hardly more than boys, one of whom ties his sandal, while the other bids a last farewell to his aged father. Leonidas had tried to send the two young men away from the battle under the pretext of carrying a message, but they had refused to go. It is perhaps this undelivered scroll that is partially visible at Leonidas' feet; it reads in Greek, 'Leonidas, son of Anaxandrides, King to the Gerousia (Spartan Council of Elders). Greetings: The final sacrifices having been made, all these men are ready to die for the glory of Sparta and in the background the baggage train departs with the possessions they will no longer need in this world. At the top left the soldier climbs the rock to inscribe the poignant message with the pommel of his sword.

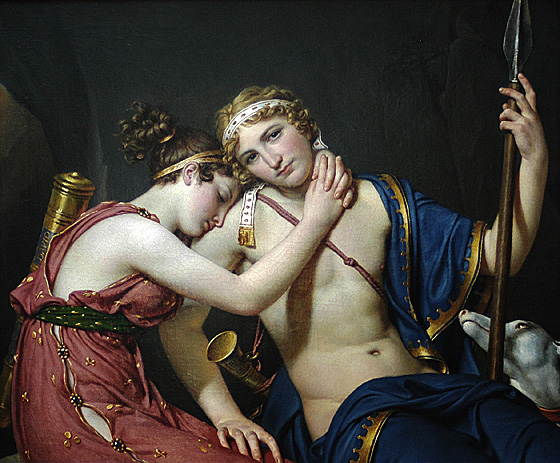

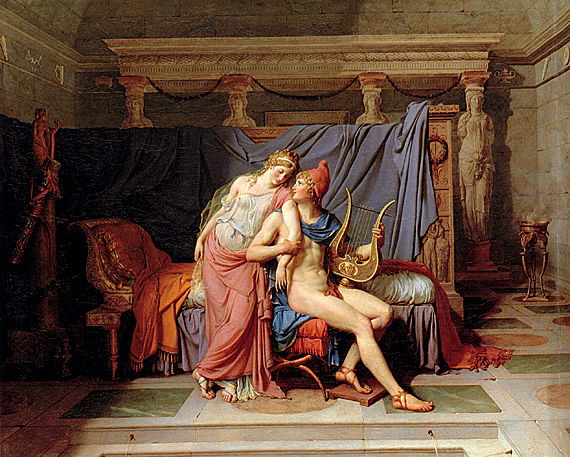

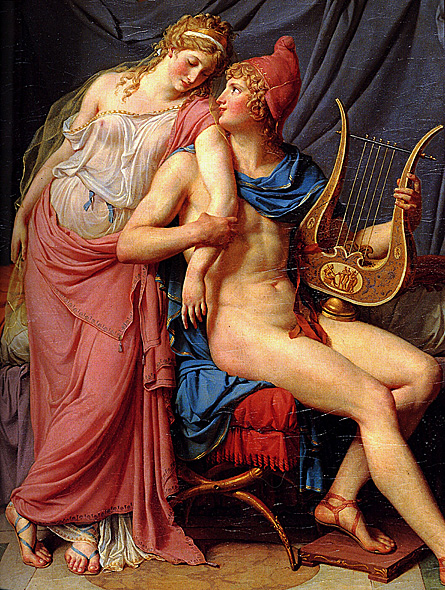

Mars, the god of war, is succumbing to the charms of Venus, but the outcome is still in doubt. Venus hesitates to place the crown of roses on his head - an emblem of submission to the pleasures of the flesh - and Cupid, who unties Mars' sandal, has put down his bow with the golden arrow of desire and the leaden arrow of repulsion side-by-side and not yet fired. Mars is shown nude and David delicately placed one of a pair of rather scruffy cooing doves to conceal his genitals for the sake of propriety. The pale Venus is an extremely delicate and sinuous form and much thinner than this voluptuous goddess is usually depicted. Behind the divine couple on the antique couch are the Three Graces who perform aimless tasks. One offers a cup of wine to Mars who has no free hand to take it, another rolls his shield as if it were a child's hoop and we can only wonder where the Grace on the left thinks she is putting Mars' helmet. Traditionally, the Graces were the beautiful handmaidens of Venus, but these are patently 'graceless Graces' and their gestures and expressions border on the absurd and comical.

The overall effect is certainly perplexing and unnerving and it is also painted in a highly colored hard-edged style that perhaps suggests considerable contributions from his Belgian assistants.

When he arrived to Rome, David rent a studio in the Via del Babuino. He worked in a very methodical manner on The Oath of the Horatii, drawing from life models and draped mannequins, and some very detailed studies survive for many of the main figures. He had accessories such as the swords and helmets made by local craftsmen so that they could serve as props. Drouais is supposed to have assisted David, painting the arm of the rear Horatii brother and the yellow garment of Sabina. The painting was finished at the end of July 1785, and was then exhibited in David's studio. David signed the painting and added the painting's place of origin to the signature and date: L David / faciebat / Romanae /Anno MDCCLXXXIV. The painting created a sensation, even the Pope wanted to view it.

The story is from the 7th century B.C., and it tells of the triplet sons of Publius Horatius, who decided the struggle between Rome and Albalonga. One survived, but he killed his own sister because she wept for one of the fallen foes, to whom she was betrothed. Condemned to death for the murder of a sibling, Horatius' son is pardoned by the will of the people.

Because of its austerity and depiction of dutiful patriotism, The Oath of the Horatii is often considered to be the clearest expression of Neoclassicism in painting. The painting's uncompromising directness, economy and tension made it instantly memorable and full of visual impact. Each of the three elements of the picture - the sons, the father and the women - is framed by a section of a Doric arcade, and the figures are located in a narrow stage-like space. David split the picture between the masculine resolve of the father and brothers and the slumped resignation of the women.. The focal point of the work is occupied by the swords that old Horatius is about to distribute to his sons. While the rear two brothers take the oath with their left hands, the foremost one swears with his right. Perhaps David did this simply as a way of grouping the figures together, but people at the time noticed this detail, and some supposed that this meant that the brother in the front would be the one to survive the combat.

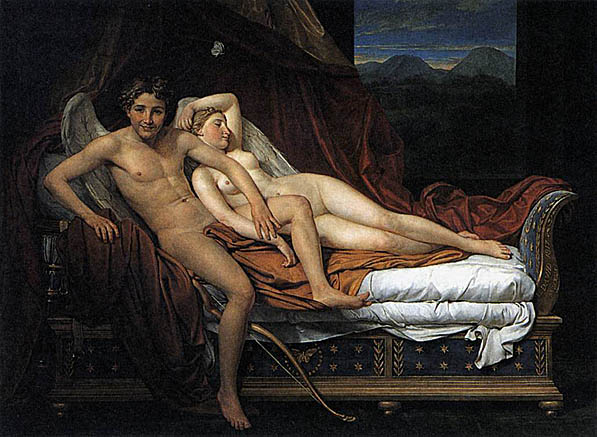

As related by the Roman writer Lucius Apuleius in The Golden Ass (late second century AD), Cupid, the god of love, fell in love with the beautiful Psyche and brought her to his palace, where he visited her every night without ever letting her see his face. But curiosity got the better of her, and one night Psyche looked at Cupid while he was asleep. Unfortunately a drop of hot oil fell from her lamp and awakened him, whereupon he abandoned her and the palace disappeared. From then on Psyche was condemned to wander the earth and perform impossible tasks in the vain hope of winning her lover back.

Many other artists saw the lovers as innocent, tender and poetic, but David deliberately drew attention to the sexual aspect of the relationship. Normally Cupid was shown as a beautiful young man, but David depicted him as a grinning adolescent who seems proud of his recent conquest. A great contrast is set up between Cupid's coarse ruddy features and awkward angular limbs, and the pale, smooth and languid beauty of the sleeping Psyche. Unusually for David, the colors are bright and intense; in Brussels he looked at the colors used by Flemish Renaissance artists such as Jan van Eyck.

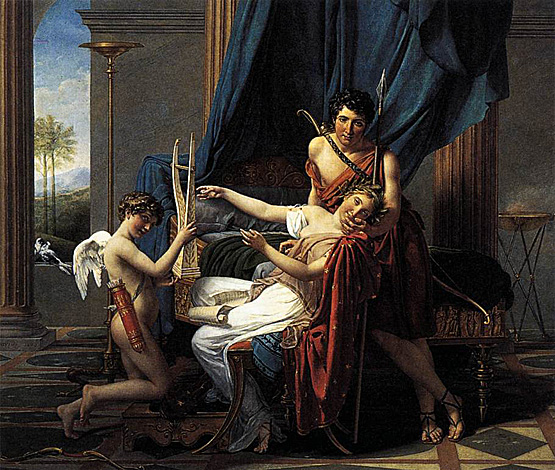

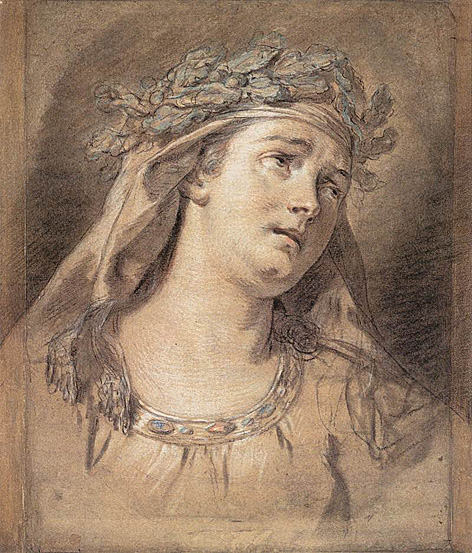

Sappho was a poetess on the Greek island of Lesbos and her affection for the young women of the cult of Aphrodite was the origin of the word 'lesbian'. However, she fell in love with the beautiful youth Phaon, the protégé of Venus, and when he only briefly reciprocated her love; she leapt to her death from the rocks at Leucadia.

Though this theme of legendary or mythological lovers was similar to that of The Loves of Paris and Helen of 1788, in this painting the couple are not totally self-absorbed and instead look out at the viewer, Phaon staring intensely and Sappho intoxicated with delight at her lover's touch. Indeed, so transported is she that she still believes herself to be playing the lyre that is now held by Cupid. For this picture about the power of physical love and its effect on the individual, David gave his lovers an almost portrait-like degree of characterization, placing them very close to the edge of the picture plane and near to the spectator. To add to the almost unreal sense of mythology come to life he also bathed the scene in harsh daylight and used bright colors and hard contours.

In the beginning, David was a supporter of the Revolution, a friend of Robespierre and a member of the Jacobin Club. While others were leaving the country for new and greater opportunities, David stayed to help destroy the old order; he was a regicider who voted in the National Assembly for the Execution of Louis XVI. It is uncertain why he did this, as there were many more opportunities for him under the King than the new order; some people suggest David's love for the classical made him embrace everything about that period, including a republican government.

Others believed that they found the key to the artist's revolutionary career in his personality. Undoubtedly, David's artistic sensibility, mercurial temperament, volatile emotions, ardent enthusiasm, and fierce independence might have been expected to help turn him against the established order but they did not fully explain his devotion to the republican regime. Nor did the vague statements of those who insisted upon his "powerful ambition. . . and unusual energy of will" actually account for his revolutionary connections. Those who knew him maintained that "generous ardor", high-minded idealism and well meaning, though sometimes fanatical, enthusiasm rather than selfishness and jealousy, motivated his activities during this period.

Soon, David turned his critical sights on Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture. This attack was probably caused primarily by the hypocrisy of the organization and their personal opposition against his work, as seen in previous episodes in David's life. The Royal Academy was full of royalists, and David's attempt to reform it did not go over well with the members. However, the deck was stacked against this symbol of the old regime, and the National Assembly ordered it to make changes to conform to the new constitution.

David then began work on something that would later hound him: propaganda for the new republic. David's painting of Brutus was shown during the play Brutus, by the famous Frenchman, Voltaire. The people responded in an uproar of approval. On June 20, 1790, the anniversary of the first act of defiance against the King, the oath of the tennis court was celebrated. David was there wanting to commemorate the event in a painting, the Jacobins, revolutionaries that had taken to meeting in the Jacobin Monastery, decided that they would choose the painter whose "genius anticipated the revolution". David accepted, and began work on a mammoth canvas. The picture was never fully completed, because of its immense size (35ft. by 36ft.) and because people that needed to sit for it disappeared in the Reign of Terror, but several finished drawings exist and parts of the original canvas also exist showing nude figures with fully painted heads

. When Voltaire died in 1778, the church denied him a church burial, and his body was interred near a monastery. A year later, Voltaire's old friends began a campaign to have his body buried in the Panthéon, as church property had been confiscated by the French Government. In 1791 David was appointed to head the organizing committee for the ceremony, a parade through the streets of Paris to the Panthéon. Despite rain, and opposition from conservatives based on the amount of money that was being spent, the procession went ahead. Up to 100,000 people watched the "Father of the Revolution" be carried to his resting place. This was the first of many large festivals organized by David for the Republic. He went on to organize festivals for martyrs that died fighting royalists. These funerals echoed the religious festivals of the pagan Greeks and Romans and are seen by many as Saturnalian.

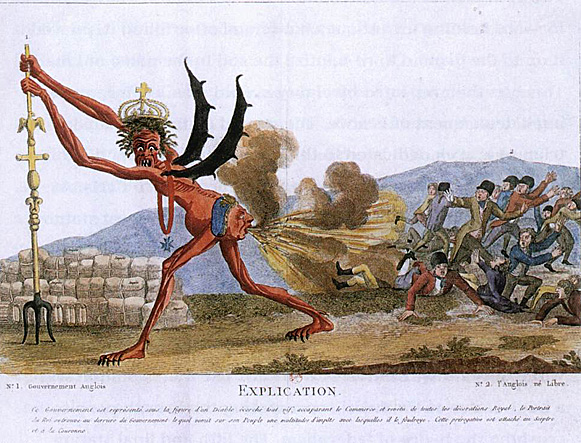

David incorporated many revolutionary symbols into these theatrical performances and orchestrated ceremonial rituals; in effect radicalizing the applied arts, themselves. The most popular symbol David was responsible for as propaganda minister was drawn from classical Greek images; changing and transforming them with contemporary politics. In an elaborate festival held on the anniversary of the revolt that brought the monarchy to its knees, David's Hercules figure was revealed in a procession following the lady Liberty (Marianne). Liberty, the symbol of Enlightenment ideals was here being overturned by the Hercules symbol; that of strength and passion for the protection of the Republic against disunity and factionalism. In his speech during the procession, David "explicitly emphasized the opposition between people and monarchy; Hercules was chosen, after all, to make this opposition more evident". It was the ideals that David linked to his Hercules that single-handedly transformed the figure from a sign of the old regime into a powerful new symbol of revolution. "David turned him into the representation of a collective, popular power. He took one of the favorite signs of monarchy and reproduced, elevated, and monumentalized it into the sign of its opposite." Hercules, the image, became to the revolutionaries, something to rally around.

In 1791, the King attempted to flee the country and was within 30 miles of the Swiss border when he had a hunger attack that led to his arrest and eventual execution. Louis XVI had made secret requests to Emperor Joseph II of Austria, Marie-Antoinette's brother, to restore him to his throne. This was granted and Austria threatened France if the royal couple were hurt. In reaction, the people arrested the King. This led to an Invasion after the trials and execution of Louis and Marie-Antoinette. The Bourbon monarchy was destroyed by the French people in 1792-it would be restored after Napoleon, and then destroyed again with the Restoration of the House of Bonaparte. When the new National Convention held its first meeting, David was sitting with his friends Jean-Paul Marat and Robespierre. In the Convention, David soon earned a nickname "ferocious terrorist". Soon, Robespierre's agents discovered a secret vault of the king's proving he was trying to overthrow the government, and demanded his execution. The National Convention held the trial of Louis XVI and David voted for the death of the King, which caused his wife, a royalist, to divorce him.

When Louis XVI was executed on January 21, 1793, another man had already died as well - Louis Michel Le Peletier de Saint-Fargeau. Le Peletier was killed on the preceding day by a royal bodyguard, in revenge for having voted the death of the King. David was called upon to organize a funeral, and he painted Le Peletier Assassinated. In it the assassin's sword was seen hanging by a single strand of horsehair above Le Peletier's body, a concept inspired by the proverbial ancient tale of the Sword of Damocles, which illustrated the insecurity of power and position. This underscored the courage displayed by Le Peletier and his companions in routing an oppressive king. The sword pierces a piece of paper on which is written 'I vote the death of the tyrant', and as a tribute at the bottom right of the picture David placed the inscription 'David to Le Peletier. 20 January 1793'. The painting was later destroyed by Le Peletier's royalist daughter, and is known only by a drawing, an engraving, and contemporary accounts. Nevertheless, this work was important in David's career, because it was the first completed painting of the French Revolution, made in less than three months, and a work through which he initiated the regeneration process that would continue with The Death of Marat, David's masterpiece.

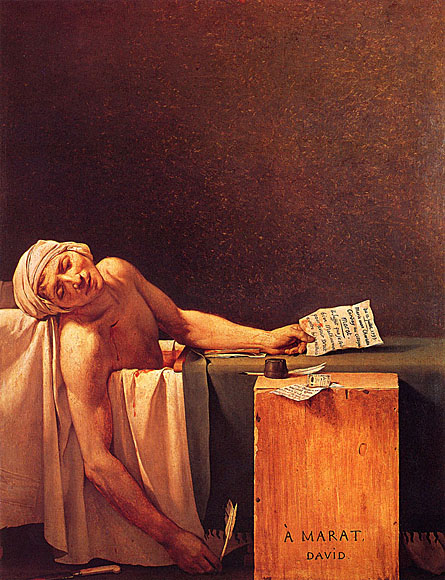

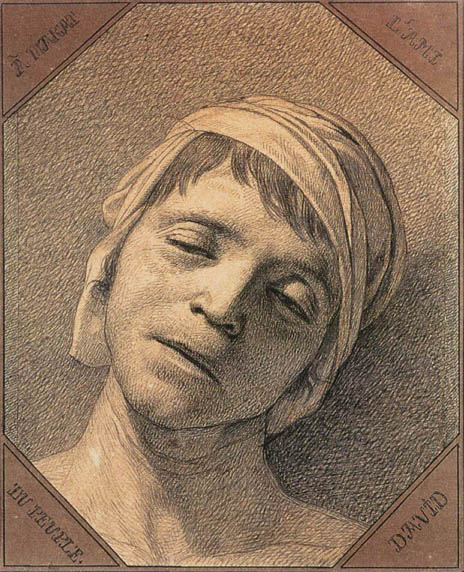

On the 13th of July 1793, David's friend Marat was assassinated by Charlotte Corday with a knife she had hidden in her clothing. She gained entrance to Marat's house on the pretense of presenting him a list of people who should be executed as enemies of France. Marat thanked her and said that they would be guillotined next week upon which Corday immediately fatally stabbed him. She was guillotined shortly thereafter. Corday was of an opposing political party, whose name can be seen in the note Marat holds in David's subsequent painting, The Death of Marat. Marat, a member of the National Assembly and a journalist, had a skin disease that caused him to itch horribly. The only relief he could get was in his bath over which he improvised a desk to write his list of suspect counter-revolutionaries which were to be quickly tried and if convicted, guillotined. David once again organized a spectacular funeral, and Marat was buried in the Panthéon. Because Marat died in the bathtub, writing, David wanted to have his body submerged in the bathtub during the funeral procession. This did not play out because the body had begun to putrefy. Instead, Marat's body was periodically sprinkled with water as the people came to see his corpse, complete with gaping wound. The Death of Marat, perhaps David's most famous painting, has been called the Pietà of the revolution. Upon presenting the painting to the convention, he said "Citizens, the people were again calling for their friend; their desolate voice was heard: David, take up your brushes.., avenge Marat... I heard the voice of the people. I obeyed." David had to work quickly, but the result was a simple and powerful image.

The Death of Marat, 1793 became the leading image of the Terror and immortalized both Marat, and David in the world of the revolution. This piece stands today as "a moving testimony to what can be achieved when an artist's political convictions are directly manifested in his work". A political martyr was instantly created as David portrayed Marat with all the marks of the real murder, in a fashion which greatly resembles that of Christ or his disciples. The subject although realistically depicted remains lifeless in a rather supernatural composition. With the surrogate tombstone placed in front of him and the almost holy light cast upon the whole scene; alluding to an out of this world existence. "Atheists though they were, David and Marat, like so many other fervent social reformers of the modern world, seem to have created a new kind of religion." At the very center of these beliefs, there stood the Republic.

Marie Antoinette on the Way to the Guillotine, 1793 October 16After executing the King, war broke out between the new Republic and virtually every major power in Europe. David, as a member of the Committee of Public Safety which was headed by Robespierre contributed directly to the reign of Terror. The committee was severe. Marie Antoinette went to the guillotine; an event recorded in a famous sketch by David. Portable guillotines killed failed generals, aristocrats, priests and perceived enemies. David organized his last festival: the festival of the Supreme Being. Robespierre had realized what a tremendous propaganda tool these festivals were, and he decided to create a new religion, mixing moral ideas with the republic, based on the ideas of Rousseau, with Robespierre as the new high priest. This process had already begun by confiscating church lands and requiring priests to take an oath to the state. The festivals, called fêtes, would be the method of indoctrination. On the appointed day, 20 Prairial by the revolutionary calendar, Robespierre spoke, descended steps, and with a torch presented to him by David, incinerated a cardboard image symbolizing atheism, revealing an image of wisdom underneath. The festival hastened the "Incorruptible's" downfall. Later, some see David's methods as being taken up by Lenin, Mussolini and Hitler. These massive propaganda events brought the people together.

Soon, the war began to go well; French troops marched across Belgium, and the emergency that had placed the Committee of Public Safety in control was no more. Then plotters seized Robespierre at the National Convention and he was later guillotined; in effect ending the reign of terror. During this seizure, David yelled to his friend "if you drink hemlock, I shall drink it with you." After this, he supposedly fell ill, and did not attend the evening session because of "stomach pain", which saved him from being guillotined along with Robespierre. David was arrested and placed in prison. There he painted his own portrait, showing him much younger than he actually was, as well as that of his jailer.

A debate quickly ensued as to how the Third Estate could protect themselves from those in positions of authority; those who wanted to destroy them. Some deputies believed that they should retreat to Paris where the people would be more likely to protect them from the King's army. Mounier warned that such a step would be blatantly revolutionary and politically dangerous. Therefore, Mounier proposed that the Third Estate adopt an oath of allegiance. The proposed oath was to read that they would remain assembled until a constitution had been written, meeting wherever it was required and resisting pressures form the outside to disband. The proposal was a success. It was promptly written and signed by 577 members of the Third Estate. Later, the document was named the Tennis Court Oath.

The Tennis Court Oath was an assertion that the sovereignty of the people did not reside with King, but in the people themselves, and their representatives. It was the first assertion of revolutionary authority by the Third Estate and it united virtually all its members to common action. Its success can be seen by the fact that a scant one week later, Louis XVI called for a meeting of the Estates General for the purpose of writing a constitution.

.jpg)

Marat often sought the comfort of a cold bath to ease violent itching due to a skin disease long said to have been contracted years earlier, when he was forced to hide from his enemies in the Paris sewers. More recent examination of Marat's symptoms has led to the assertion that Marat's skin eruptions came from coeliac disease, an allergy to gluten, found most commonly in wheat.

David was a close friend of Marat, as well as a strong supporter of Robespierre and the Jacobins. He was overwhelmed by their natural capacity for convincing crowds with their speeches, something he hadn't yet easily achieved through painting (not to mention his difficulty to speak, due to a facial deformation caused by an injury during a duel). Determined to memorialize his friend, David not only organized for him a lavish funeral, but painted his portrait soon afterwards. He was asked to do it because of his previous painting, The Death of Lepelletier de Saint-Fargeau. (After 1826, nobody saw this work, representing the first martyr of the Revolution, a deputy murdered on January 20. The official reason for his death was for having voted for the death of King Louis XVI, though he was possibly also the victim of some obscure plot implicating Spain.)

Despite the haste in which the portrait of Marat was painted (the work was completed and presented to the National Convention less than four months after Marat's death), it is generally considered to be David's best work, a definite step towards modernity, and an inspired and inspiring political statement.

The painting remained unfinished.

After David's wife visited him in jail, he conceived the idea of telling the story of the Sabine Women. The Sabine Women Enforcing Peace by Running between the Combatants, also called The Intervention of the Sabine Women is said to have been painted to honor his wife, with the theme being love prevailing over conflict. The painting was also seen as a plea for the people to reunite after the bloodshed of the revolution.

This work also brought him to the attention of Napoleon. The story for the painting is as follows: "The Romans have abducted the daughters of their neighbors, the Sabines. To avenge this abduction, the Sabines attacked Rome, although not immediately-since Hersilia, the daughter of Tatius, the leader of the Sabines, had been married to Romulus, the Roman leader, and then had two children by him in the interim. Here we see Hersilia between her father and husband as she adjures the warriors on both sides not to take wives away from their husbands or mothers away from their children. The other Sabine Women join in her exhortations." During this time, the martyrs of the revolution were taken from the Pantheon and buried in common ground, and revolutionary statues were destroyed. When he was finally released to the country, France had changed. His wife managed to get David released from prison, and he wrote letters to his former wife, and told her he never ceased loving her. He remarried her in 1796. Finally, wholly restored to his position, he retreated to his studio, took pupils and retired from politics.

In one of history's great coincidences, David's close association with the Committee of Public Safety during the Terror resulted in his signing of the death warrant for one Alexandre de Beauharnais, a minor noble. De Beauharnais's widow, Rose-Marie Josèphe de Tascher de Beauharnais would later be known to the world as Joséphine Bonaparte, Empress of the French. It was her coronation by her husband, Napoleon I that David depicted so memorably in the Coronation of Napoleon and Josephine 2 December 1804.

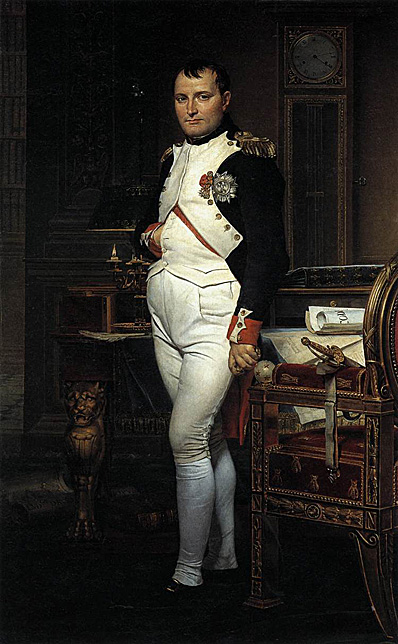

David had been an admirer of Napoleon from their first meeting, struck by the then-General Bonaparte's classical features. Requesting a sitting from the busy and impatient general, David was able to sketch Napoleon in 1797. David recorded the conqueror of Italy's face, but the full composition of General Bonaparte holding the peace treaty with Austria remains unfinished. Napoleon had high esteem for David, and asked him to accompany him to Egypt in 1798, but David refused, claiming he was too old for adventuring and sending instead his student, Antoine-Jean Gros.

After Napoleon's successful coup d'etat in 1799, as First Consul he commissioned David to commemorate his daring crossing of the Alps. The crossing of the St. Bernard Pass had allowed the French to surprise the Austrian army and win victory at the Battle of Marengo on June 14, 1800. Although Napoleon had crossed the Alps on a mule, he requested that he be portrayed "calm upon a fiery steed". David complied with Napoleon Crossing the Saint-Bernard. After the proclamation of the Empire in 1804, David became the official court painter of the regime.

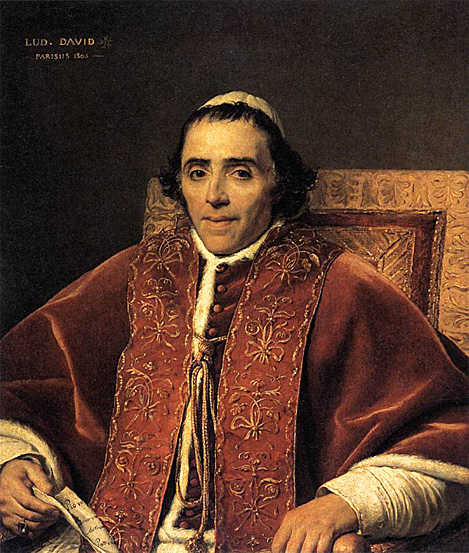

One of the works David was commissioned for was The Coronation of Napoleon in Notre Dame. David was permitted to watch the event. He had plans of Notre Dame delivered and participants in the coronation came to his studio to pose individually, though never the Emperor (the only time David obtained a sitting from Napoleon had been in 1797). David did manage to get a private sitting with the Empress Josephine and Napoleon's sister, Caroline Murat, through the intervention of erstwhile art patron, Marshal Joachim Murat, the Emperor's brother-in-law. For his background, David had the choir of Notre Dame act as his fill-in characters. The Pope came to sit for the painting, and actually blessed David. Napoleon came to see the painter, stared at the canvas for an hour and said "David, I salute you". David had to redo several parts of the painting because of Napoleon's various whims, and for this painting, David received only 24,000 Francs.

Exile

After the Bourbons returned to power, David was on the list of proscribed former revolutionaries and Bonapartists, as he had voted for the execution of Louis XVI and probably had something to do with the death of Louis XVII. Mistreated and starved, Louis XVII had been forced to confess to an incestuous relationship, while in prison, with his mother, Marie-Antoinette. (This allegation helped to guillotine her, but it was a lie as Louis was separated from his mother and not allowed to see her.) The new Bourbon King, Louis XVIII, however, granted David amnesty and even offered him a position as a court painter. David refused this offer, preferring instead to seek a self-imposed exile in Brussels. There, he painted Cupid and Psyche and lived out the last days of his life quietly with his wife, whom he had remarried. During this time, he largely devoted his efforts to smaller-scale paintings of mythological scenes and to portraits of Bruxellois and Napoleonic émigrés, such as the Baron Gerard.

His last great work, begun in 1822 and finished the year before his death, was a subject from Greek mythology, Mars Disarmed by Venus and the Three Graces. In December 1823, he wrote: "This is the last picture I want to paint, but I want to surpass myself in it. I will put the date of my 75 years on it and afterwards I will never again pick up my brush." The finished canvas-reminiscent in its limpid coloration of a painting on porcelain-was first shown in Brussels and then was sent to Paris, where David's former students flocked to see the painting. The exhibit managed to bring in after operating costs, 13,000 francs, meaning there were more than 10,000 visitors, a huge number for the time.

When David was leaving the theater, he was hit by a carriage and later died of deformations to the heart in December 29, 1825. After his death, some of his portrait paintings were sold at auction in Paris, where they sold for very small sums. His famous painting of Marat was shown in a special secluded room so as not to outrage the public. David's body was not allowed to return to France, despite pleas of his family, because of David's part in the execution of Louis XVI and was therefore buried at Evere Cemetery, Brussels. His heart was buried at Père Lachaise, Paris.

David was commissioned by Napoleon to paint a large composition commemorating his consecration, which had taken place in Notre Dame in Paris, on 2 December 1804. The picture was exhibited in the Salon Carré in the Louvre in 1808, then in the Salon of that year; it was next placed in the Tuileries, in the Salle des Gardes. Under Louis Philippe it was installed at Versailles in a room decorated in imitation of the Empire style, together with David's Distribution of the Eagles and Gros' Battle of Aboukir; in 1889 it was transferred to the Louvre, and its place at Versailles was taken by Roll's Marseillaise. In 1947 this latter picture was replaced by a replica of David's Consecration of Napoleon, begun by the painter in 1808 and not finished till 1822, in Brussels; this replica was bought by the Musées de France in England, in 1946.

David seems to have derived his general composition from Rubens' Coronation of Queen Marie de Medici.

In accordance with David's usual method, numerous studies, both painted and drawn, preceded the actual execution of the work. The best-known of these is the portrait of Pius VII, now in the Louvre. The painter then made a model, where he arranged dolls in costume.

David had originally intended to portray the event faithfully, showing Napoleon crowning himself. The Emperor, remembering the quarrels between the Pope and the Holy Roman Empire, placed the crown on his own head to avoid giving a pledge of obedience of the temporal power to the Pontiff. But he evidently felt that it would not be desirable to perpetuate this somewhat disrespectful action in paint; so David painted the coronation of Josephine by Napoleon, with the Pope blessing the Empress.

Grouped round the altar, near Napoleon, are the chief dignitaries - Cambécères, the Lord Chancellor, Marshal Berthier, Grand Veneur, Talleyrand, the Lord Chamberlain, and Lebrun, the Chief Treasurer. Madame de la Rochefoucauld carries the Empress's train; behind her are the Emperor's sisters, and his brothers Louis and Joseph. In front of the central stand are some of the marshals, and in it is Marie Laetitia, Madame Mère (the Emperor's mother), who was in fact not present at the ceremony.

.jpg)

_2.jpg)

Grouped round the altar, near Napoleon, are the chief dignitaries — Cambécères, the Lord Chancellor, Marshal Berthier, Grand Veneur, Talleyrand, the Lord Chamberlain, and Lebrun, the Chief Treasurer. Madame de la Rochefoucauld carries the Empress's train; behind her are the Emperor's sisters, and his brothers Louis and Joseph. In front of the central stand are some of the marshals, and in it is Marie Laetitia, Madame Mère (the Emperor's mother), who was in fact not present at the ceremony.

_3.jpg)

_4.jpg)

David and his studio executed four versions of this painting, differing only slightly in the colour of the mantle.

Although he did not pay for it, Napoleon liked the picture and said: 'You have found me out, dear David; at night I work for my subjects' happiness, and by day I work for their glory.'

Potocki came from one of the most celebrated Polish families, and had recently become very wealthy thanks to his wife's dowry. He was also a scholar, and translated and commented on the work of Winckelmann. Obviously his portrait had to be impressive and suggestive of his status. Therefore David depicted him on horseback, subduing a skittish horse with consummate ease. David turned to the example of the great Baroque portraitist Anthony van Dyck to create a work that was similar in scale and impact.

Although David made his name with large heroic narrative pictures on themes from antiquity, some of his finest works are portraits of contemporaries, in which he combines lifelike realism with the severe compositions, controlled color range and unostentatious brushwork of the Neo-classical style. Jacobus Blauw is an especially fine example, and interestingly combines the painter's political and artistic concerns. The sitter was a leading Dutch patriot who, in 1795 or, as David dates the painting, year 4 of the French Revolutionary Calendar helped to establish the Batavian Republic. When the French army invaded the Netherlands later that year Blauw, along with his countryman Caspar Meyer, was sent to Paris to negotiate a peace settlement. It was then that they commissioned David to paint their portraits (the one of Meyer is in the Louvre). It is clear, however, that of the two it was Blauw whom David found more sympathetic.

Blauw is shown seated writing an official document, a device which enables the artist to organise the composition with strict geometry, predominantly horizontal and vertical lines meeting at a right angle and echoing the shape of the canvas. (Or one can think of the sitter as forming a pyramid above the desk.) The fiction that Blauw has just turned from his work to pause for thought provides the motive for presenting him in full-face view. David softens the discomfort felt in such direct confrontation, however, by placing the head off-center and by leaving the eyes unfocused. The pose combines great stability with a sense of momentary action, and seems to give us an insight into Blauw's character. He is shown in simple dress befitting a republican: a plain coat, a soft cravat, his own hair powdered, instead of an aristocrat's wig. A wonderful touch enlivens his brass buttons: gleams of red, implying unexplained reflections from the artist's studio, the viewer's space.

In David's portrait, noble simplicity, expressed by the simple dress and the Spartan decoration, is also eloquent in the open face. This might well appear more to the modern viewer than Gérard's version, which was judged to be more representative and flattering at the time. And comparisons with portraits of Madame Récamier by other artists suggest that Gérard had achieved a better likeness than David. The Spartan severity of David's composition, the Neoclassical sparseness of the arrangement, the cool handling of the room, the distanced pose, with the lady turning her shoulder to the viewer, were all elements with which Neoclassicism had operated for long enough.

Gérard, by contrast, sets the lady in a noble park loggia, where she seems to be inviting to conversation. Her low-cut bodice is seductive; the red curtain flatters the subject and gives the flesh a rosy tint. Where David gave the beautiful woman a rather severe touch around the mouth, Gérard embellishes her features with the hint of a gentle smile, making her look younger. By contrast, David's portrait in the antique manner looks rather forced. Perhaps these were the reasons why his painting was never finished. Madame Récamier gave Gérard's portrait of her to her admirer Prince Augustus of Prussia, a nephew of Frederick II, who had met the French beauty at the salon of Madame de Staël. For state reasons a marriage was impossible, but in the painting Madame Récamier was ever present in the palace which Schinkel furnished for the Prince in 1817.

In 1771, Lavoisier married the 13-year-old Marie-Anne Pierrette Paulze, the daughter of a co-owner of the Ferme. Over time, she proved to be a scientific colleague to her husband. She translated documents from English for him, including Richard Kirwan's Essay on Phlogiston and Joseph Priestley's research. She created many sketches and carved engravings of the laboratory instruments used by Lavoisier and his colleagues. She also edited and published Lavoisier's memoirs (whether any English translations of those memoirs have survived was unknown as of the summer of 2007) and hosted parties at which eminent scientists discussed ideas and problems related to chemistry.

Lavoisier received a law degree and was admitted to the bar, but never practiced as a lawyer. He did become interested in French politics, and at the age of 26 he obtained a position as a tax collector in the Ferme Générale, a tax farming company, where he attempted to introduce reforms in the French monetary and taxation system to help the peasants. While in government work, he helped develop the metric system to secure uniformity of weights and measures throughout France.

As one of twenty-eight French tax collectors and a powerful figure in the unpopular Ferme Générale, Lavoisier was branded a traitor during the Reign of Terror by French Revolutionists in 1794. Lavoisier had also intervened on behalf of a number of foreign-born scientists including mathematician Joseph Louis Lagrange, granting them exception to a mandate stripping all foreigners of possessions and freedom. Lavoisier was tried, convicted, and guillotined on May 8 in Paris, at the age of 50.

The image of Caspar Mayer is formal and distant. He was a shrewd and circumspect diplomat and David placed him in a self-conscious pose. Due to political reasons, Mayer never collected the painting from David's studio, where it remained until the artist's death.

These two portraits were testaments of friendship and, by showing them at the 1795 Salon, he could prove that he was still able to paint after his ordeals.

David had been an admirer of Napoleon from their first meeting, struck by the then-General Bonaparte's classical features. Requesting a sitting from the busy and impatient general, David was able to sketch Napoleon in 1797. David recorded the conqueror of Italy's face, but the full composition of General Bonaparte holding the peace treaty with Austria remains unfinished. Napoleon had high esteem for David, and asked him to accompany him to Egypt in 1798, but David refused, claiming he was too old for adventuring and sending instead his student, Antoine-Jean Gros.

After Napoleon's successful coup d'état in 1799, as First Consul he commissioned David to commemorate his daring crossing of the Alps. The crossing of the St. Bernard Pass had allowed the French to surprise the Austrian army and win victory at the Battle of Marengo on June 14, 1800. Although Napoleon had crossed the Alps on a mule, he requested that he be portrayed "calm upon a fiery steed". David complied with Napoleon Crossing the Saint-Bernard. After the proclamation of the Empire in 1804, David became the official court painter of the regime.

The Coronation of Napoleon, (1806).One of the works David was commissioned for was The Coronation of Napoleon in Notre Dame. David was permitted to watch the event. He had plans of Notre Dame delivered and participants in the coronation came to his studio to pose individually, though never the Emperor (the only time David obtained a sitting from Napoleon had been in 1797). David did manage to get a private sitting with the Empress Josephine and Napoleon's sister, Caroline Murat, through the intervention of erstwhile art patron, Marshal Joachim Murat, the Emperor's brother-in-law. For his background, David had the choir of Notre Dame act as his fill-in characters. The Pope came to sit for the painting, and actually blessed David. Napoleon came to see the painter, stared at the canvas for an hour and said "David, I salute you". David had to redo several parts of the painting because of Napoleon's various whims, and for this painting, David received only 24,000 Francs.

David's frank but sympathetic portrait catches not only the homeliness of his wife's features, but her intelligence and directness as well. Unlike many of David's works, this portrait was painted entirely by his own hand. Its technique is freer than the austere style he applied to less intimate subjects. The satiny texture of her dress, unadorned by jewelry as Madame David surrendered hers in support of the revolution, is created with heavy brushes of thick pigment, the plume with lighter strokes of thinner color. These exuberant surfaces contrast with the restrained precision of the accessories in Napoleon's portrait.

Conclusions:

I think that it is difficult for any amateur or would be historian not to find the period of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Era to be intriguing as well as confusing at the same time. Jacques-Louis David, I believe, is a reflection of the time in which he lived. How can you be a son of the Revolution with the under girding of the thoughts and words of a man like Voltaire and then become the engine of empire to ensure that liberté, égalité, fraternité are a reality and not some vague dream of an altruistic lie? How can you oppose and fight against despotism just to redefine authoritarianism to allow the despot to emerge as a dictator no matter what title you might give him or what veiled trappings of decency to disguise an utter disregard for human dignity?

Napoleon Bonaparte as First Consul of the Republic issued his First Proclamation to the French People in December of 1799 after seizing control of the French government and establishing the Consulate along with a new constitution written by his own hand. Napoleon said, "Citizens, the Revolution is established on the principles which began it! It is ended." There are historians and social scientists today who believe that there is a 'Pattern of Revolution' that can turn a democratic egalitarian movement into an authoritarian controlled state through 'common consent' of the people. Certain situation and circumstances may vary but you will see a logical pattern of events emerge.

On the eve of the revolution, the government had failed to meet the needs of the people, and had denied political power to new and powerful social or economic groups, and lost the support of intellectuals.

The revolution began with a dramatic act that demonstrated the inability of government to control the course of events.

Moderates in the revolutionary movement seize power and attempt a program of moderate reform.

The moderate reform program arouses opposition and violence --- by counterrevolutionary forces within the country and by fearful foreign countries.

To preserve the revolution in the "crisis stage", the extremists of the Revolutionary movement seize control and employ force and terror against enemies of the revolution.

It is the "tendency for power to go from the conservatives to the moderates and then to the radicals or extremists."

With the crisis surmounted and the public sick of the bloodletting, the terror comes to an end.

In the ensuing period of political instability, a powerful leader emerges, seizes power, and rules as a dictator.

The problem for us today is that dictatorship and revolution are inevitably closely associated because revolutions to a certain extent break down, or at least weaken laws, customs, habits, beliefs which bind a society together.

The public acceptance of the dictator is based on the belief that he will preserve some of the revolution while at the same time providing political stability and social cohesion.

Source: Web Gallery of Art

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.