American Artist

1861 - 1909

Art is a she-devil of a mistress, and if at times in earlier days she would not even stoop to my way of thinking, I have persevered and will so continue.

~ Frederic Remington

Frederic Sackrider Remington was an American painter, illustrator, sculptor, and writer who specialized in depictions of the Old American West, specifically concentrating on the last quarter of the 19th century American West and images of Cowboys, American Indians, and the U.S. Cavalry.

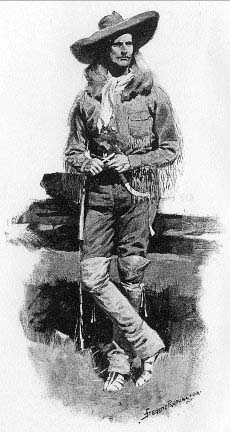

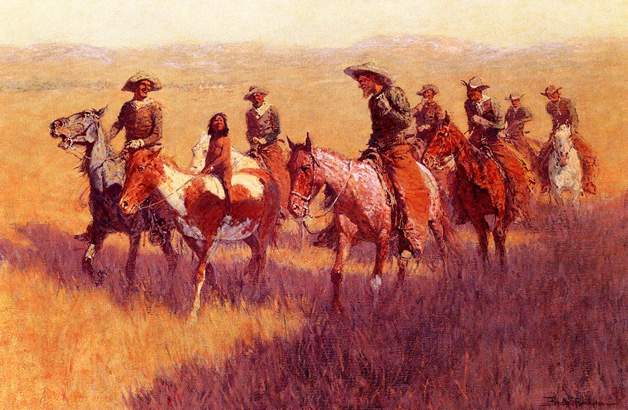

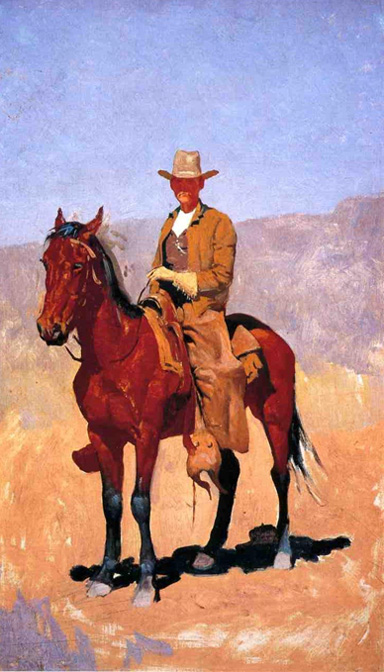

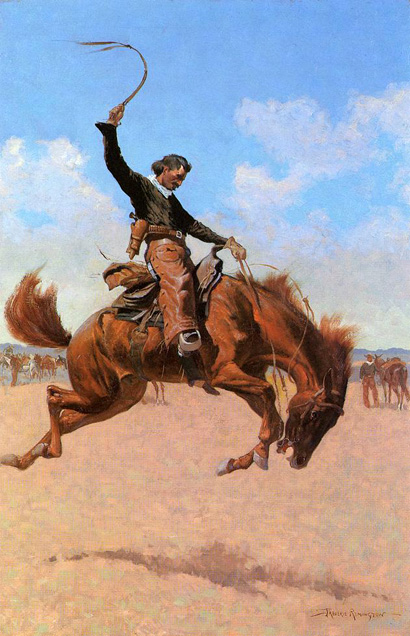

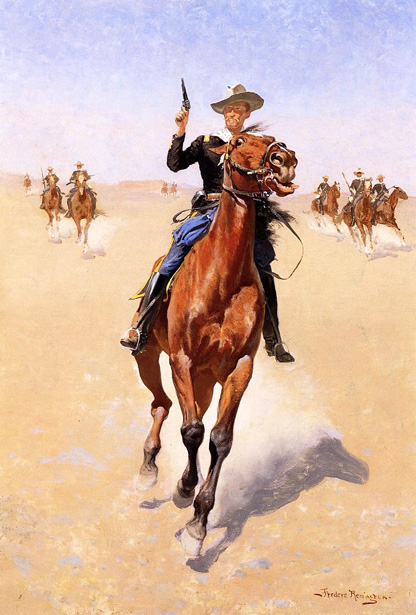

The rise of the cowboy as the romantic hero of the American West began shortly after the Civil War, and Remington was one of the principal artists to play a part in that development. One of the cowboy's most vocal supporters was the artist's friend Theodore Roosevelt; the cowboy in Remington's painting reflects what Roosevelt had to say about the cowboy as hero. In a series of articles illustrated by Remington on his experiences as a ranchman in the Dakota Territory published in Century Magazine in 1888-89, Roosevelt described the cowboys he knew as "hardy and self-reliant as any men who ever breathed." He praised the cowboy's strength of character, which included a "frank and simple" approach to life, a "whole-souled hospitality" to others, and an air of "grave courtesy" to outsiders. By the time the writer Owen Wister published his novel The Virginian in 1902, such traits were embedded in the central character, thus beginning a long line of western heroes that would later appear in fiction and film. Not surprisingly, Wister dedicated his novel to Roosevelt.

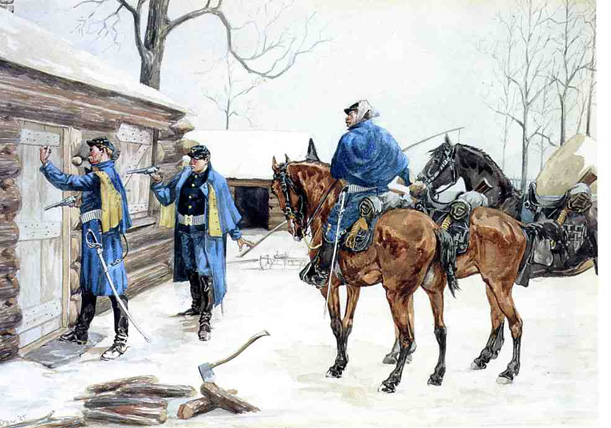

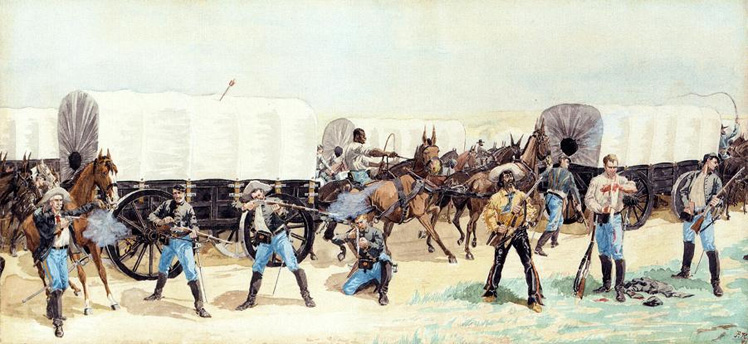

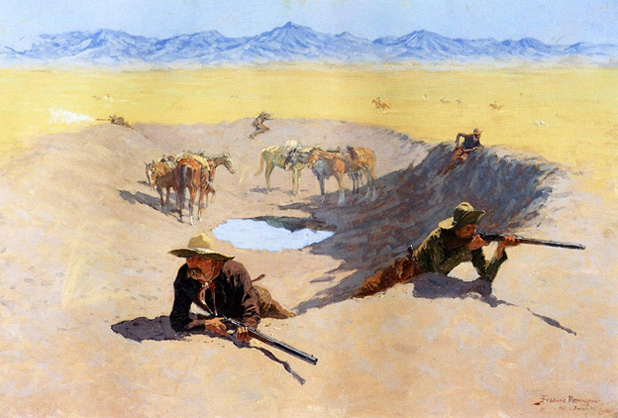

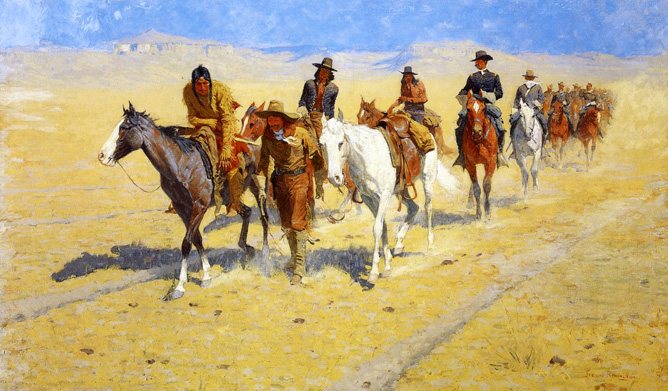

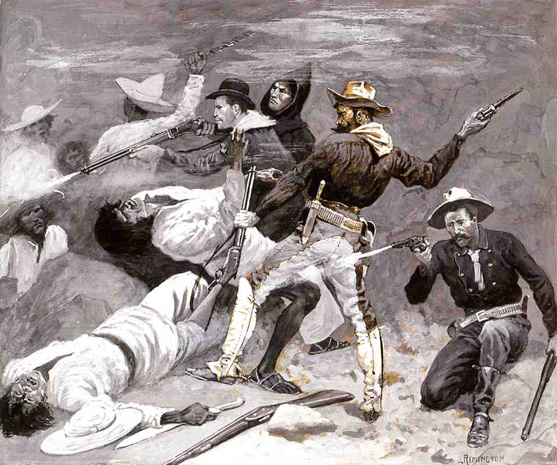

For the group of soldiers in the foreground, Remington actually borrowed an earlier composition of his own, a sketch done during a trip to Arizona and New Mexico in 1888. In this period Remington grew to become one of the most ardent spokesmen for the U.S. Cavalry, and reforms within the military infrastructure. General Nelson A. Miles, one of the senior officers who were thought to be in line for commander of the U.S. Army, was one of the artist's most important admirers. As the demand for Remington's work steadily increased, he continued to tap the wellspring of his earlier field work for inspiration. This painting was included in Remington's first one-man exhibition and auction, consisting of nearly one hundred works, held at the American Art Galleries in January 1893. Practically all of the pieces were sold, and the receipts nearly equaled those of the entire annual exhibition at the National Academy of Design.

Remington was born in Canton, New York in 1861 to Seth Pierre Remington and Clara Bascom Sackrider, whose paternal family owned hardware stores and emigrated from Alsace-Lorraine in the early 1700's. Remington's father was a colonel in the Civil War whose family arrived in the United States from England in 1637. He was a newspaper editor and postmaster, and the family was active in local politics and staunchly Republican. One of Remington's great grandfathers, Samuel Backcomb, was a saddle maker by trade, and the Remington's were fine horsemen. Frederic Remington was related by family bloodlines to Indian portrait artist George Catlin and cowboy sculptor Earl W. Bascom.

Colonel Remington was away at war during most of the first four years of his son's life. After the war, he moved his family to Bloomington, Illinois for a brief time and was appointed editor of the Bloomington Republican, but the family returned to Canton in 1867. Remington was the only child of the marriage, and received constant attention and approval. He was an active child, large and strong for his age, who loved to hunt, swim, ride, and go camping. He was a poor student, though, particularly in math, which did not bode well for his father's ambitions for his son to attend West Point. He began to make drawings and sketches of soldiers and cowboys at an early age.

The family moved to Ogdensburg, New York when Remington was eleven and he attended Vermont Episcopal Institute, a church-run military school, where his father hoped discipline would rein in his son's lack of focus, and perhaps lead to a military career. Remington took his first drawing lessons at the Institute. He then transferred to another military school where his classmates found the young Remington to be a pleasant fellow, a bit careless and lazy, good-humored, and generous of spirit, but definitely not soldier material. He enjoyed making caricatures and silhouettes of his classmates. At sixteen, he wrote to his uncle of his modest ambitions, "I never intend to do any great amount of labor. I have but one short life and do not aspire to wealth or fame in a degree which could only be obtained by an extraordinary effort on my part". He imagined a career for himself as a journalist, with art as a sideline.

Remington attended the art school at Yale University, the only male in the freshman year. However, he found that football and boxing were more interesting than the formal art training, particularly drawing from casts and still life objects. He preferred action drawing and his first published illustration was a cartoon of a "bandaged football player" for the student newspaper Yale Courant. Though he was not a star player, his participation on the strong Yale football team was a great source of pride for Remington and his family. He left Yale in 1879 to tend to his ailing father who had tuberculosis. His father died a year later, at age forty-six, receiving respectful recognition from the citizens of Ogdensburg. Remington's Uncle Mart secured a good paying clerical job for his nephew in Albany, New York and Remington would return home on weekends to see his girlfriend Eva Caten. After the rejection of his engagement proposal to Eva by her father, Remington became a reporter for his Uncle Mart's newspaper, then went on to other short-lived jobs.

Living off his inheritance and modest work income, Remington refused to go back to art school and instead spent time camping and enjoying himself. At nineteen, he made his first trip west, going to Montana, at first to buy a cattle operation then a mining interest but realized he did not have sufficient capital for either. In the Ol' West of 1881, he saw the vast prairies, the quickly shrinking buffalo herds, the still unfenced cattle, and the last major confrontations of U.S. Cavalry and Native American tribes, scenes he had imagined since his childhood. Though the trip was undertaken as a lark, it gave Remington a more authentic view of the West than some of the later artists and writers who followed in his footsteps, such as N. C. Wyeth and Zane Grey, who arrived twenty-five years later when the Ol' West had slipped into history. From that first trip, Harper's Weekly published Remington's first published commercial effort, a re-drawing of a quick sketch on wrapping paper that he had mailed back East. In 1883, Remington went to rural Peabody, Kansas, to try his hand at the booming sheep ranching and wool trade, as one of the "holiday stockmen", rich young Easterners out to make a quick killing as ranch owners. He invested his entire inheritance but Remington found ranching to be a rough, boring, isolated occupation which deprived him of the finer things of Eastern life, and the real ranchers thought him a lazy playboy.

Remington continued sketching but at this point his results were still cartoonish and amateurish. After less than a year, he sold his ranch and went home. After acquiring more capital from his mother, he returned to Kansas City to start a hardware business, but due to an alleged swindle it failed, and he reinvested his remaining money as a silent, half owner of a saloon. He went home to marry Eva Caten in 1884 and they returned to Kansas City immediately. She was unhappy with his saloon life and was unimpressed by the sketches of saloon inhabitants that Remington regularly showed her. When his real occupation became known, she left her husband and returned to Ogdensburg. With his wife gone and with business doing badly, Remington started to sketch and paint in earnest, and bartered his sketches for essentials.

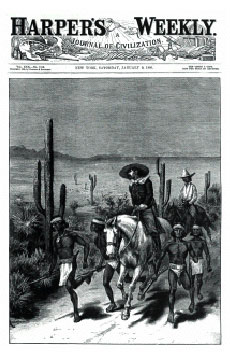

He soon had enough success selling his paintings to locals to see art as a real profession. Remington returned home again, his inheritance gone but his faith in his new career secured, reunited with his wife and moved to Brooklyn. He began studies at the Art Students League of New York and significantly bolstered his fresh though still rough technique. His timing was excellent as newspaper interest in the dying West was escalating. He submitted illustrations, sketches, and other works for publication with Western themes to Collier's and Harper's Weekly, as his recent Western experiences (highly exaggerated) and his hearty, breezy "cowboy" demeanor gained him credibility with the eastern publishers looking for authenticity. His first full page cover under his own name appeared in Harper's Weekly on January 9, 1886, when he was twenty-five. With financial backing from his Uncle Bill, Remington was able to pursue his art career and support his wife.

In 1885 Remington made the original drawing, The Apaches Are Coming, using an inked brush and a pen on paper. He sent the drawing to Harper's Weekly Magazine, where staff engravers copied it freehand onto the surface of a wood block in pencil. Then, with small, sharp metal tools, they created grooves. The wood lines that were not caved away would print the illustration. They engraved the block as a mirror image of the original so it would be oriented properly on the page.

The block appears white because talc was rubbed into the grooves to make the image more visible for display. It wasn't done until after the block was retired from printing.

The block was then fitted together adjoining text and printed in thousands of copies of the magazine.

In 1886, Remington was sent to Arizona by Harper's Weekly on a commission as an artist-correspondent to cover the government's war against Geronimo. Although he never caught up with Geronimo, Remington did acquire many authentic artifacts to be used later as props, and made many photos and sketches valuable for later paintings. He also made notes on the true colors of the West, such as "shadows of horses should be a cool carmine and Blue", to supplement the black and white photos. Ironically, art critics later criticized his palette as "primitive and unnatural" even though it was based on actual observation.

After returning back East, Remington was sent by Harper's Weekly to cover the Charleston, South Carolina earthquake of 1886. To expand his commission work, he also began doing drawings for Outing Magazine. His first year as a commercial artist had been successful, earning Remington $1,200, almost triple that of a typical teacher. He had found his life's work and bragged to a friend, "That's a pretty good break for an ex cow-puncher to come to New York with $30 and catch on it 'art'."

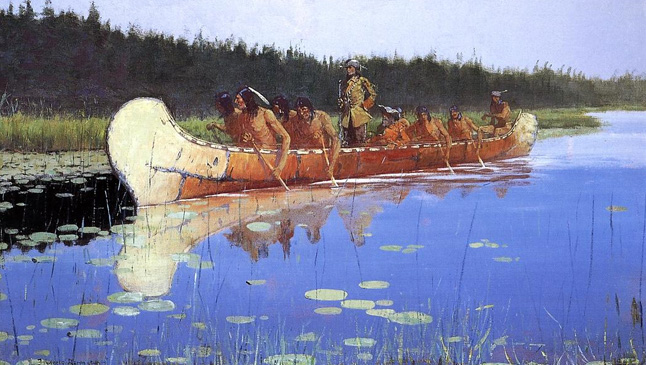

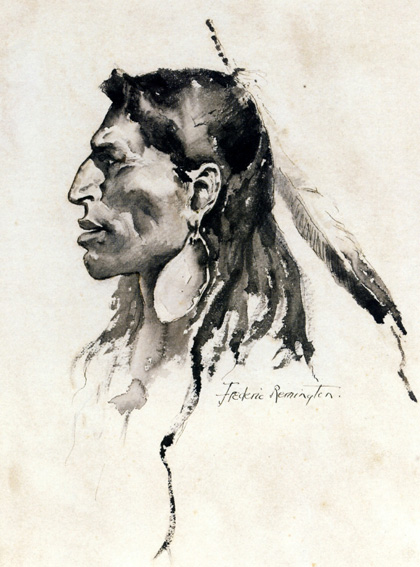

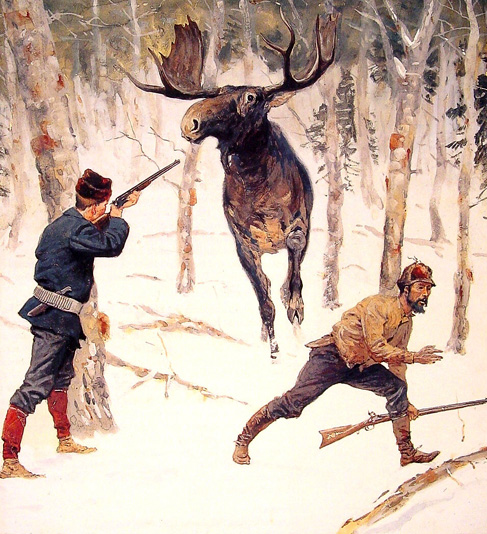

For commercial reproduction in black-and-white, he produced ink and wash drawings. As he added watercolor, he began to sell his work in art exhibitions. His works were selling well but garnered no prizes, as the competition was strong and masters like Winslow Homer and Eastman Johnson were considered his superiors. A trip to Canada in 1887, produced illustrations of the Blackfoot, the Crow Nation, and the Canadian Mounties, eagerly enjoyed by the reading public.

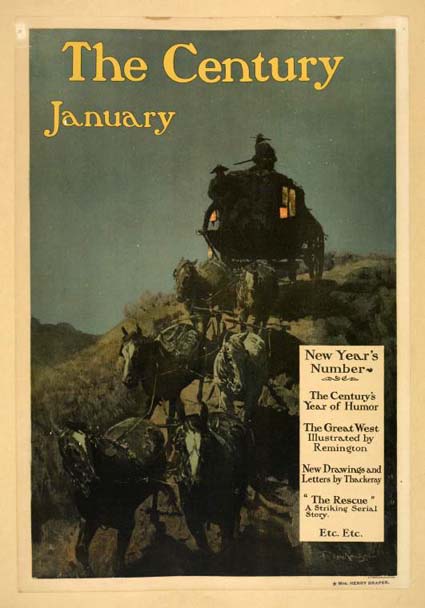

Later that year, Remington received a commission to do eighty-three illustrations for a book by Theodore Roosevelt, Ranch Life and the Hunting Trail, to be serialized in The Century Magazine before publication. The twenty-five year old Roosevelt had a similar Western adventure to Remington, losing money on a ranch in North Dakota the previous year but gaining experience which made him an "expert" on the West. The assignment gave Remington's career a big boost and forged a lifelong connection with Roosevelt.

His full-color oil painting Return of the Blackfoot War Party was exhibited at the National Academy of Design and the New York Herald commented that Remington would "one day be listed among our great American painters". Though not admired by all critics, Remington's work was deemed "distinctive" and "modern". By now, he was demonstrating the ability to handle complex compositions with ease, as in Mule Train Crossing the Sierras (1888), and to show action from all points of view His status as the new trendsetter in Western art was solidified in 1889 when he won a second-class medal at the Paris Exposition. He had been selected by the American committee to represent American painting, over Albert Bierstadt whose majestic, large-scale landscapes peopled with tiny figures of pioneers and Indians was now considered passé.

Around this time, Remington made a gentleman's agreement with Harper's Weekly, giving the magazine an informal first option on his output but maintaining Remington's independence to sell elsewhere if desired. As a bonus, the magazine launched a massive promotional campaign for Remington, stating that "He draws what he knows, and he knows what he draws." Though laced with blatant puffery (common for the time) claiming that Remington was a bona fide cowboy and Indian scout, the effect of the campaign was to raise Remington to the equal of the era's top illustrators, Howard Pyle and Charles Dana Gibson.

His first one-man show, in 1890, presented twenty-one paintings at the American Art Galleries and was very well received. With success all but assured, Remington became established in society. His personality, his "pseudo-cowboy" speaking manner, and "Wild West" reputation were strong social attractions. His biography falsely promoted some of the myths he encouraged about his Western experiences.

Remington's regular attendance at celebrity banquets and stag dinners, however, though helpful to his career, fostered prodigious eating and drinking which caused his girth to expand alarmingly. Obesity became a constant problem for him from then on. Among his urban friends and fellow artists, he was "a man among men, a deuce of a good fellow" but notable because he (facetiously) "never drew but two women in his life, and they were failures" (not counting Indian women). In 1890, Remington moved to posh New Rochelle, New York to his new estate "Endion", in order to have both more living space and extensive studio facilities, and also with the hope of gaining more exercise.

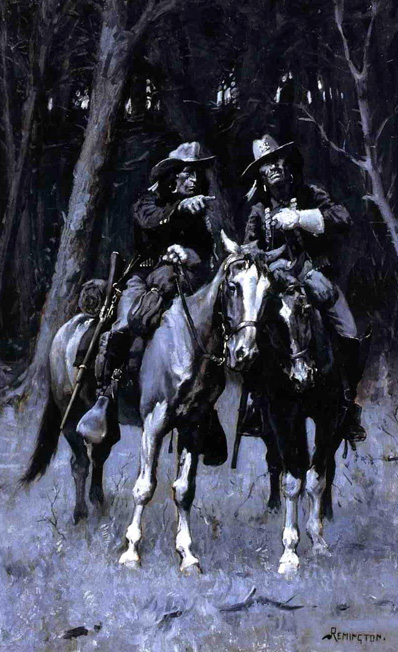

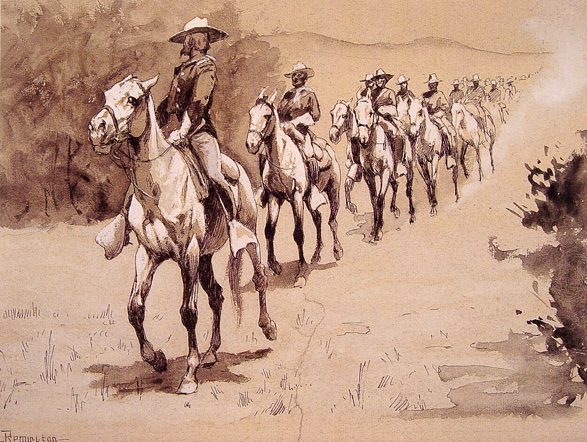

Remington's fame made him a favorite of the Western Army officers fighting the last Indian battles. He was invited out West to make their portraits in the field and to gain them national publicity through Remington's articles and illustrations for Harper's Weekly, particularly General Nelson Miles, an Indian fighter who aspired to the presidency of the United States. In turn, Remington got exclusive access to the soldiers and their stories, and boosted his reputation with the reading public as "The Soldier Artist". Remington arrived on the scene just after the Massacre at Wounded Knee, in which over 300 Sioux were slaughtered and which he reported it as "The Sioux Outbreak in South Dakota", praising the Army's "heroic" actions in dealing with the Indians. Some of the Miles paintings are monochromatic and have an almost "you-are-there" photographic quality, heightening the realism, as in The Parley (1898).

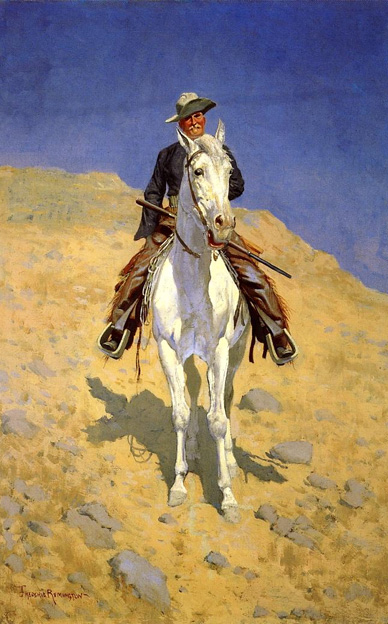

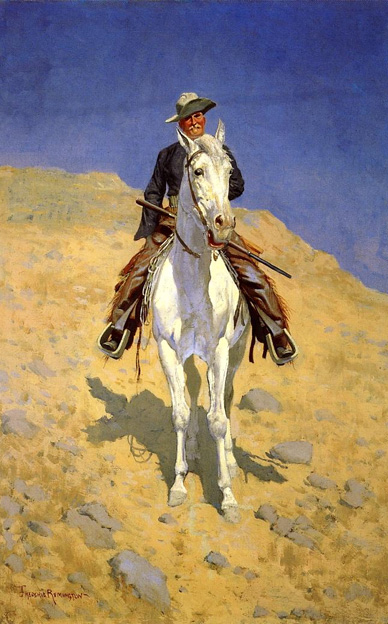

Remington's Self-Portrait on a Horse (1890) shows the artist as he wished he was, not the pot-bellied Easterner weighing heavily on a horse, but a tough, lean cowboy heading for adventure with his trusty steed. It was the image his publishers worked hard to maintain as well. In His Last Stand (1890), a cornered bear in the middle of a prairie is brought down by dogs and riflemen, which may have been a symbolized treatment of the dying Indians he had witnessed. Remington's attitude toward Native Americans was typical for the time. He thought them unfathomable, fearless, superstitious, ignorant, and pitiless-and generally portrayed them as such. White men under attack were brave and noble.

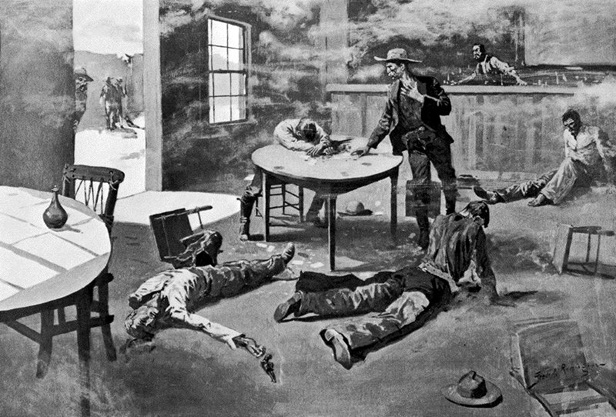

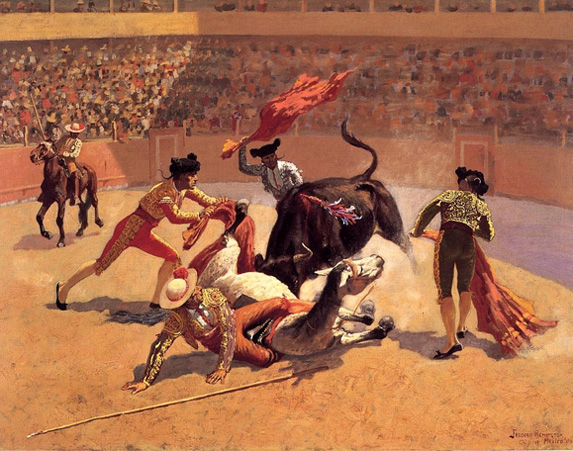

Through the 1890's, Remington took frequent trips around the U.S., Mexico, and abroad to gather ideas for articles and illustrations, but his military and cowboy subjects always sold the best, even as the Old West was playing out. Gradually, he transitioned from the premiere chronicler-artist of the Old West to its most important historian-artist. He formed an effective partnership with Owen Wister, who became the leading writer of Western stories at the time. Having more confidence of his craft, Remington wrote, "My drawing is done entirely from memory. I never use a camera now. The interesting never occurs in nature as a whole, but in pieces. It's more what I leave out than what I add." Remington's focus continued on outdoor action and he rarely depicted scenes in gambling and dance halls typically seen in Western movies. He avoids frontier women as well. His painting A Misdeal (1897) is a rare instance of indoor cowboy violence.

Remington had developed a sculptor's 360 degree sense of vision but until a chance remark by playwright Augustus Thomas in 1895, Remington had not yet conceived of himself as a sculptor and thought of it as a separate art for which he had no training or aptitude. With help from friend and sculptor Frederick Ruckstuhl, Remington constructed his first armature and clay model, a "Bronco Buster" where the horse is reared on its hind legs-technically a very challenging subject. After several months, the novice sculptor overcame the difficulties and had a plaster cast made, then bronze copies, which were sold at Tiffany's. Remington was ecstatic about his new line of work, and though critical response was mixed, some labeling it negatively as "illustrated sculpture", it was a successful first effort earning him $6,000 over three years.

Frederic Remington made his astonishing debut as a sculptor with 'The Bronco Buster'. His career in sculpture began with the active encouragement of the academically trained sculptor Frederick Ruckstull (1853-1942), who assured Remington that he could draw as clearly with clay as he could on paper. Ruckstull helped him with technical matters, urging him to think of a popular subject with "fine composition, correct movement, and expressive form." Remington, who knew little about the technical limitations of bronze casting, created a model that immediately challenged established conventions of sculptural composition. He excitedly wrote a friend to say that "I am modeling-I find I do well-I am doing a cowboy on a bucking bronco and I am going to rattle down through all the ages."

Remington was entirely self-taught as a sculptor, and this subject of a cowboy astride a rearing horse proved to be the artist's most popular work. This particular example-one of three casts in the Amon Carter Museum collection-was produced by the Henry-Bonnard Bronze Company in New York using a sand-casting process that involved the careful preparation of molds filled with a special type of fine sand. Approximately sixty-four largely identical castings appear to have been made by the Henry-Bonnard Bronze Company between 1895 and 1900. Remington's spirited sculpture of a bronco rider has become one of the most enduring images of the western experience. The work's perpetuation of western myths is due in part to its great popularity, and the fact that its image is instantly recognizable to a broad audience. "I propose to do some more," he told The Century Magazine shortly after the first casts of 'The Bronco Buster' were completed, "to put the wild life of our West into something that burglar won't have, moth eat, or time blacken."

During that busy year, Remington became further immersed in military matters, inventing a new type of ammunition carrier; but his patented invention was not accepted for use by the War Department. His favorite subject for magazine illustration was now military scenes, though he admitted, "Cowboys are cash with me". Sensing the political mood of that time, he was looking forward to a military conflict which would provide the opportunity to be a heroic war correspondent, giving me both new subject matter and the excitement of battle. He was growing bored with routine illustration, and he wrote to Howard Pyle, the dean of American illustrators, that he had "done nothing but potboil of late". (Earlier, he and Pyle in a gesture of mutual respect had exchanged paintings-Pyle's painting of a dead pirate for Remington's of a rough and ready cowpuncher). He was still working very hard, spending seven days a week in his studio.

Remington was further irritated by the lack of his acceptance to regular membership by the Academy, likely due to his image as a popular, cocky, and ostentatious artist. Remington kept up his contact with celebrities and politicos, and continued to woo Theodore Roosevelt, now the New York City Police Commissioner, by sending him complimentary editions of new works. Despite Roosevelt's great admiration for Remington, he never purchased a Remington painting or drawing.

Remington's association with Roosevelt paid off, however, when the artist became a war correspondent and illustrator during the Spanish-American War in 1898, sent to provide illustrations for William Randolph Hearst's New York Journal. He witnessed the assault on San Juan Hill by American forces, including those led by Roosevelt. However, his heroic conception of war, based in part on his father's Civil War experiences, were shattered by the actual horror of jungle fighting and the deprivations he faced in camp. His reports and illustrations upon his return focused not on heroic generals but on the troops, as in his Scream of the Shrapnel (1899), which depicts a deadly ambush on American troops by an unseen enemy. When the Rough Riders returned to the U.S., they presented their courageous leader Roosevelt with Remington's bronze statuette, The Bronco Buster, which the artist proclaimed, "the greatest compliment I ever had…After this everything will be mere fuss." Roosevelt responded, "There could have been no more appropriate gift from such a regiment."

In 1888, he achieved the public honor of having two paintings used for reproduction on U. S. Postal stamps. In 1900, as an economy move, Harper's dropped Remington as their star artist. To compensate for the loss of work, Remington wrote and illustrated a full-length novel, The Way of an Indian, which was intended for serialization by a Hearst publication but not published until five years later in Cosmopolitan. Remington's protagonist, a Cheyenne named Fire Eater, is a prototype Native American as viewed by Remington and many of his time.

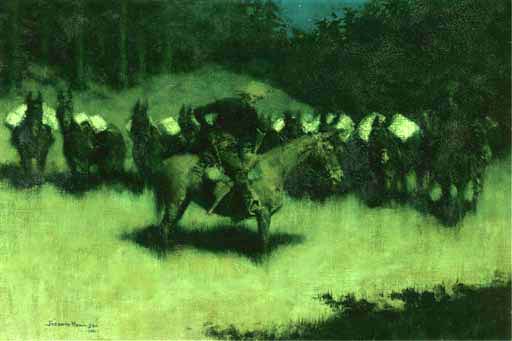

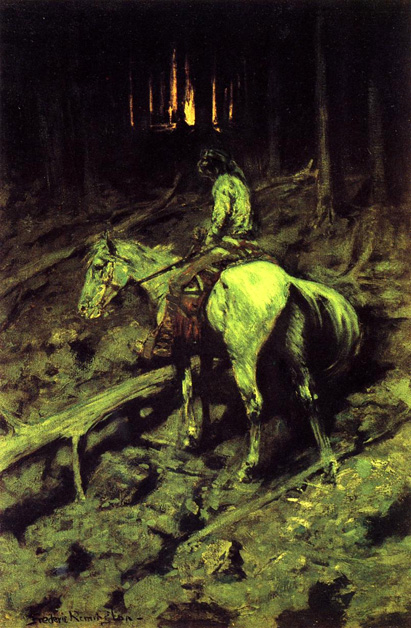

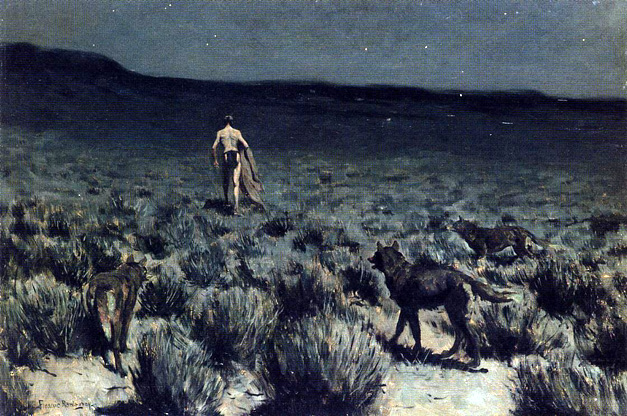

Remington then returned to sculpture, and produced his first works produced by the lost wax method, a higher quality process than the earlier sand casting method he had employed. By 1901, Collier's was buying Remington's illustrations on a steady basis. As his style matured, Remington portrayed his subjects in every light of day. His nocturnal paintings, very popular in his late life, such as A Taint on the Wind and Scare in the Pack Train, are more impressionistic and loosely painted, and focus on the unseen threat.

Remington completed another novel in 1902, John Ermine of the Yellowstone, a modest success but a definite disappointment as it was completely overshadowed by the best seller The Virginian, written by his sometime collaborator Owen Wister, which became a classic Western novel. A stage play based on "John Ermine" failed in 1904. After "John Ermine", Remington decided he would soon quit writing and illustration (after drawing over 2700 illustrations) to focus on sculpture and painting.

In 1905, Remington had a major publicity coup when Collier's devoted an entire issue to the artist and his art, showcasing his latest works. His large outdoor sculpture of a "Big Cowboy", which stands on the Kelly Drive in Philadelphia, was another late success. His "Explorers" series, depicting older historical events in western U.S. history, did not fare well with the public or the critics. The financial panic of 1907 caused a slowdown in his sales and in 1908, fantasy artists, such as Maxfield Parrish, became popular with the public and with commercial sponsors. Remington tried to sell his home in New Rochelle to get further away from urbanization. One night he made a bonfire in his yard and burned dozens of his oil paintings which had been used for magazine illustration (worth millions of dollars today), making an emphatic statement that he was done with illustration forever. He wrote, "there is nothing left but my landscape studies". Near the end of his life, he moved to Ridgefield, Connecticut. In his final two years, under the influence of The Ten, he was veering more heavily to Impressionism, and he regretted that he was studio bound (by virtue of his declining health) and could not follow his peers who painted "plein air".

Frederic Remington died after an emergency appendectomy led to peritonitis on December 26, 1909. His extreme obesity (weight nearly 300 lbs.) had complicated the anesthesia and the surgery, and chronic appendicitis was cited in the post-mortem examination as an underlying factor in his death.

The Frederick Remington House was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1965.

Remington was the most successful Western illustrator in the "Golden Age" of illustration at the end of the 19th Century and the beginning of the 20th Century, so much so that the other Western artists such as Charles Russell and Charles Schreyvogel were known during Remington's life as members of the "School of Remington". His style was naturalistic, sometimes impressionistic, and usually veered away from the ethnographic realism of earlier Western artists such as George Catlin. His focus was firmly on the people and animals of the West, with landscape usually of secondary importance, unlike the members and descendants of the Hudson River School, such as Frederic Edwin Church, Albert Bierstadt, and Thomas Moran, who glorified the vastness of the West and the dominance of nature over man. He took artistic liberties in his depictions of human action, and for the sake of his readers' and publishers' interest. Though always confident in his subject matter, Remington was less sure about his colors, and critics often harped on his palette, but his lack of confidence drove him to experiment and produce a great variety of effects, some very true to nature and some imagined.

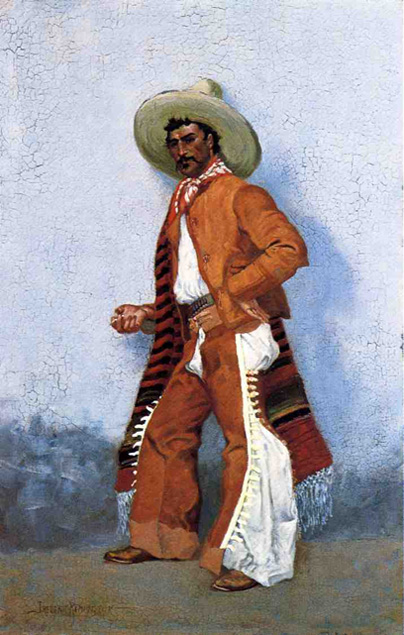

His collaboration with Owen Wister on The Evolution of the Cowpuncher, published by Harper's Monthly in September 1893, was the first statement of the mythical cowboy in American literature, spawning the entire genre of Western fiction, films, and theater that followed. Remington provided the concept of the project, its factual content, and its illustrations and Wister supplied the stories, sometimes altering Remington's ideas. (Remington's prototype cowboys were Mexican rancheros but Wister made the American cowboys descendants of Saxons-in truth, they were both partially right, as the first American cowboys were both the ranchers who tended the cattle and horses of the American Revolutionary army on Long Island and the Mexicans who ranched in the Arizona and California territories).

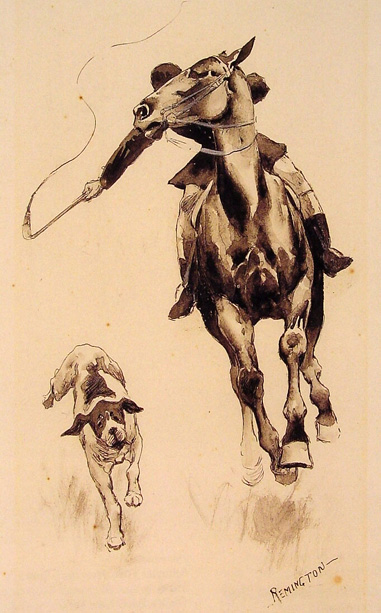

Remington was one of the first American artists to illustrate the true gait of the horse in motion (along with Thomas Eakins), as validated by the famous sequential photographs of Eadweard Muybridge. Previously, horses in full gallop were usually depicted with all four legs pointing out, like "hobby horses". The galloping horse became Remington's signature subject, copied and interpreted by many Western artists who followed him, adopting the correct anatomical motion. Though criticized by some for his use of photography, Remington often created depictions that slightly exaggerated natural motion to satisfy the eye. He wrote, "the artist must know more than the camera... (the horse must be) incorrectly drawn from the photographic standpoint (to achieve the desired effect)."

Also, noteworthy was Remington's invention of "cowboy" sculpture. From his inaugural piece, The Bronco Buster (1895), he created an art form which is still very popular among collectors of Western art.

An early advocate of the photoengraving process over wood engraving for magazine reproduction of illustrative art, Remington became an accepted expert in reproduction methods, which helped gain him strong working relationships with editors and printers. Furthermore, Remington's skill as a businessman was equal to his artistry, unlike many other artists who relied on their spouses or business agents or no one at all to run their financial affairs. He was an effective publicist and promoter of his art. He insisted that his originals be handled carefully and returned to him in pristine condition (without editor's marks) so he could sell them. He carefully regulated his output to maximize his income and kept detailed notes about his works and his sales.

The "cowboy picture" Remington was referring to is 'A Dash for the Timber', which launched his career as a major painter when it was exhibited to critical acclaim at the National Academy later that year. "This work marks an advance on the part of one of the strongest of our younger artists, who is one of the best illustrators we have," praised a writer in the New York Herald. "The drawing is true and strong, the figures of men and horses are in fine action, tearing along at a full gallop, the sunshine effect is realistic and the color is good." Indeed, Remington's skillful delineation of the horses is a particular artistic triumph; they charge toward the viewer with nostrils flaring and every muscle strained to its limits. The headlong motion of horses and riders seems suspended above patches of cool purple and shadowy blue, contrasting with warmer hues of yellow and orange in the surrounding landscape. The overall effect of the painting is truly cinematic, and the action-filled portrayal of the struggle of life on a dangerous frontier anticipates the many western films that were to follow after the turn of the century, when Remington's western images were already deeply embedded in the popular imagination.

_ca_1894.jpg)

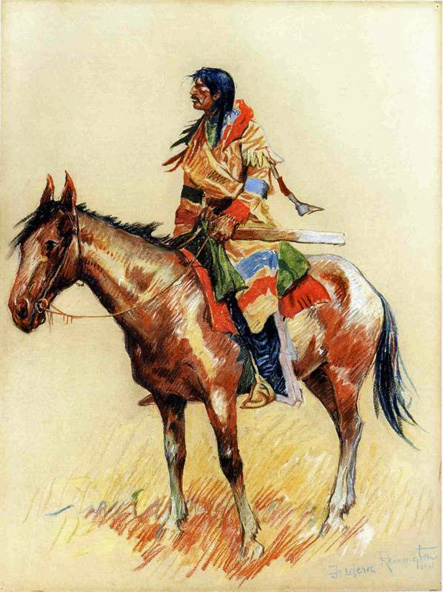

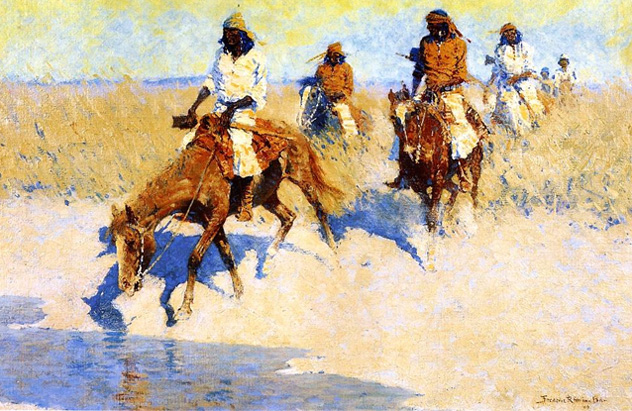

The painting also served as an illustration for an article by Colonel Theodore A. Dodge, titled "Some American Riders," which appeared in Harper's New Monthly Magazine in May 1891. Dodge noted that the figure in the painting could be a Cree or a Blackfoot, "whom one was apt to run across in the Selkirk Mountains or elsewhere, on the plains of the British Territories, or well up north in the Rockies." The trapper wears a Huson's Bay Company blanket coat, and fringed leggings and moccasins decorated with beadwork. His hat, of a typical Blackfoot type, is made of animal fur, and suitable for the cold climate. A rolled-up buffalo coat or robe can be seen behind his saddle, and a two-bladed "beaver tail" knife in a colorful scabbard is visible against the red sash around his waist. The trapper grips a tack-studded quirt in his left hand, while cradling a rifle that shows the same type of decoration. The horse is the typically lithe, hammer-headed variety that Remington frequently depicted in his works; here, its sleek black coat shimmers in the stark light of the alpine landscape.

Remington indeed left the color out of this study of a cavalry unit caught in a sudden sandstorm; it appeared in Harper's Weekly for September 14, 1889, as an illustration to a story by a former cavalry soldier about an Arizona desert sandstorm his unit had experienced. "All in one moment the whole sky seemed to rush down upon us as if it were a big pepper-box with the lid off, and instantly all was dark as night, and I felt as if forty thousand ants were eating me up at once," he recalled. "You should have seen how the beasts whisked round to get their backs to it, and ducked their heads down! And how the men shut their eyes and pulled their hats down over their faces, and covered their mouths with their hands! But it was no use trying to keep the dust out; it seemed to get inside one's very skin. When it cleared off we all looked as if we'd been bathing in brown sugar, and you might have raked a match on any part of my skin, and it would have lit right away."

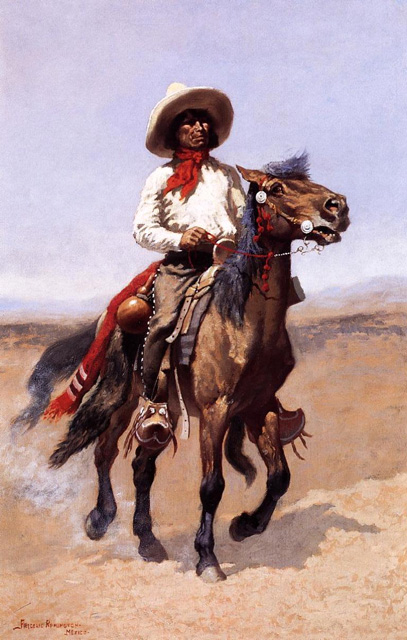

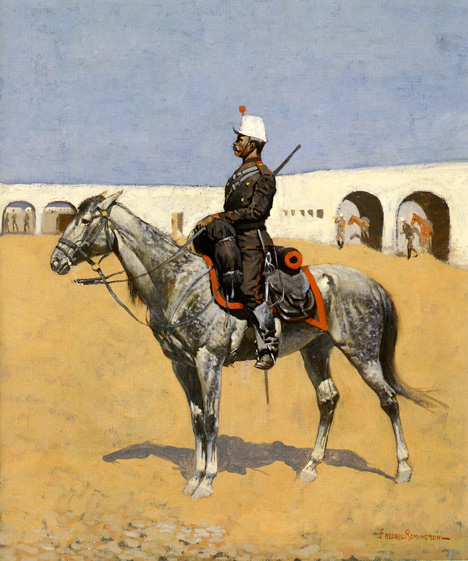

"The scene is an arid upland in a white glare of sunlight beneath an unchanging blue sky," the article began. It went on to describe the "strikingly picturesque" figure of a horseman sitting erect in his saddle, "with all the esprit of his profession," a soldier who was not likely to be prevented from "carrying out to the letter the orders of his official superiors or his individual ideas of military duty. These qualities are evident in Remington's respectful portrayal of the cavalryman, whose unit was efficient enough to be a dreaded enemy even to the fierce Apaches. Remington's depiction of the dappled horse in this painting is particularly accomplished, the result of much careful study in the field. Mexican horses were smaller than their American counterparts but also "wiry, fleet, enduring animals, light of foot and very effective for a short dash," the writer for Harper's Weekly observed. "They can live upon little, and pick up subsistence where larger, more carefully trained horses would starve."

_1893.jpg)

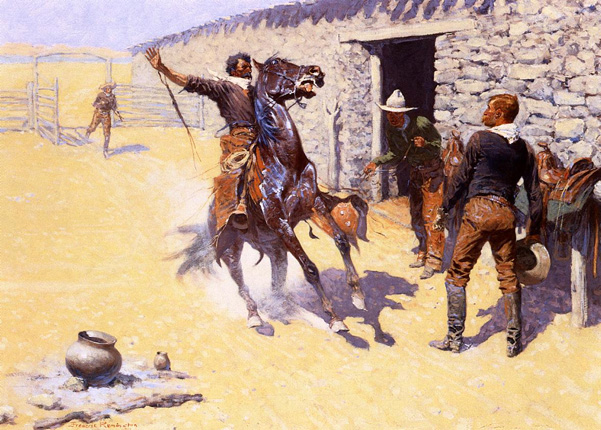

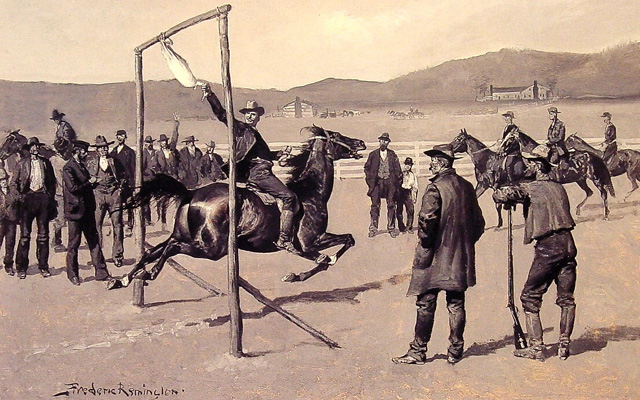

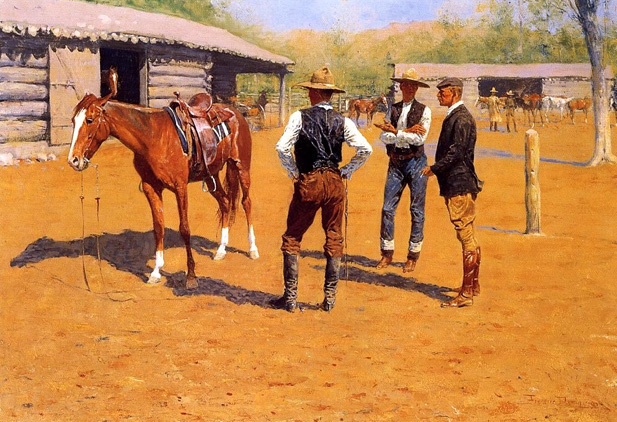

Those colors can be seen in the sun and shadow of Remington's painting, as two cowhands make ready to break a wary and frightened horse, whose right rear leg has been tied up to keep him off balance. The men seem to resemble Remington's description of the Texas foremen at the ranch, each of whom wore "heavy chaparras, a slouch hat, and a white 'boiled' shirt." The foremen's duties, according to the artist, comprised "anything and everything," including breaking recalcitrant horses that no one else could ride. Remington's painting is notable for its looser brushwork and vibrant colors-both the result of his interest in the impressionist style. The sunlit foreground contains small islands of dappled color amidst violet shadows; warm hues of burnt orange and mustard yellow are set against patches of iridescent green the artist himself accurately described as "burning bright like opals."

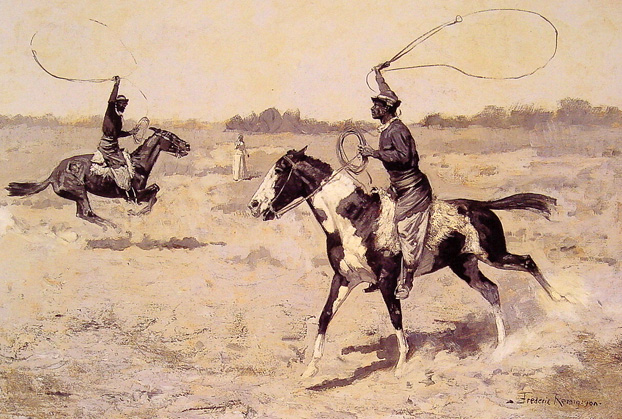

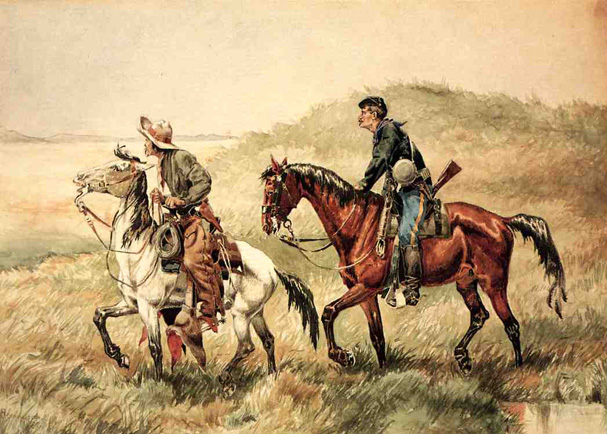

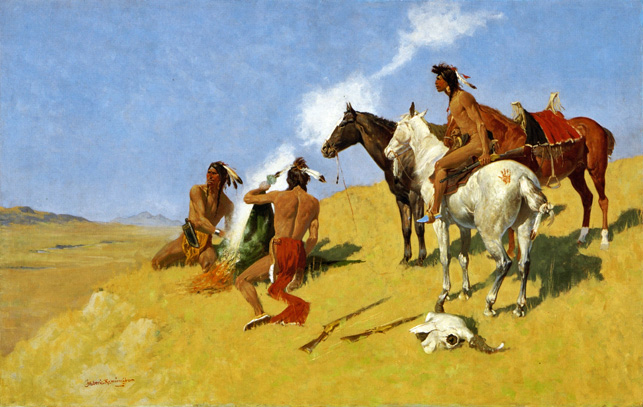

This watercolor was reproduced in "Indians as Irregular Cavalry," an article that Remington wrote for the December 27, 1890 issue of Harper's Weekly. In the article, the artist took a somewhat enlightened attitude towards the plight of Indians on the reservations, arguing that they be allowed to serve in some branches of the military. He praised the units of Indian scouts and soldiers he had seen, adding that there was no way for them to earn a regular living on their reservations. "We are year after year oppressing a conquered people, until now it is assuming the magnitude of a crime," he wrote. At the same time, he praised officers like Robertson as exemplary soldiers who understood the Indians and tried to work with them, asserting that "this is the sort of man who should take the place of the halfpenny politician who has been nurtured in the belief that to plunder the Indians is a natural reward for good service in his district."

_1888.jpg)

_1896.jpg)

Remington's spirited bronze of 'The Cheyenne' was one of the first subjects produced by Roman Bronze Works using the lost-wax casting process. The foundry's owner, Riccardo Bertelli, was anxious to please Remington as a potential client, and the early casts of the warrior on horseback are among the finest in terms of texture and detail that the foundry ever created for the artist. Remington was particularly anxious for the final bronze to retain a strong sense of motion. In a letter to Bertelli, he provided a sketch of the model with a vertical axis drawn to show how he wanted the buffalo robe to support the figure but to the rear of the center. "I very much want to preserve the effect of the action which would be ruined by bringing it too far forward," he wrote. To the artist's relief, Bertelli was able to comply with the request. Remington supervised only twenty casts of this work before he destroyed the mold. Only the first six casts display a beautiful brownish yellow patina, instead of the dark greenish black coloring used on later examples such as the one illustrated here. In general the casts made during Remington's lifetime have the highest degree of finish and surface detail.

Wister's article, titled "The Evolution of the Cow-Puncher," finally appeared in the September 1895 issue of Harper's Monthly, accompanied by a number of illustrations by Remington. One of these was the painting shown here. Beneath leaden skies of gunmetal gray, two cowboys have halted their horses in a bleak wintry landscape. One of them has dismounted to remove the rails of a fence gate so they can pass through. The whole scene is infused with the slow rhythms and somber tones of an elegy; a lament for something that has gone forever. Remington, like his friend Theodore Roosevelt, also a great popularizer of the West in this period, viewed the cowboy as the last great figure of America's frontier history; hardy and self reliant, but doomed to extinction in the wake of civilization's steady progress. This mythic image was soon to be immortalized in the pages of Owen Wister's The Virginian, published to wide acclaim in 1902-arguably the first western novel.

This painting was included in a highly successful exhibition of Remington's work that opened at the Knoedler Galleries in December 1908. "Frederic Remington sounds a purely American note," one newspaper critic noted. "His color is purer, more vibrant, more telling, and his figures are more in atmosphere." The New York Times agreed, adding that "the types of western character are like what we see in imagination when we call to mind a western scene." Such observations were what the artist wanted to hear. Following the exhibition he worked feverishly to paint what he termed "that very illusive thing," and he was hard on himself when he felt he had not succeeded. He grew to thoroughly dislike much of his earlier work. "I would buy them all if I were able and burn them up," he wrote morosely in his diary.

_1903.jpg)

'The Long-Horn Cattle Sign' is a prime example of a work that was intended, in Remington's own words, "to glow and quiver until it seems to exude the palpitating quality which light holds." Indeed, the men and horses in the painting seem to be dissolving into patches of color-laden brushstrokes, while the surrounding landscape shimmers in broad areas of vibrant hues. Overall, Remington's scene has a dreamlike quality, as if it is happening in another time. It conveys a true sense of Remington's own West-a world that existed only in the artist's imagination. In this painting, he uses light and color, as he once said, to make the viewer "feel the details and not see them." What counts in this painting is the basic visual impression, and its emotive feeling. With paintings such as this Remington felt he had turned a corner in his art. Unfortunately, he had little time to explore this further, for in less than a year he would be dead.

The need for vigilance seems to be the subject of Remington's painting, which shows a stagecoach traveling in a nocturnal landscape. Sitting atop the coach and silhouetted against the starlit sky is a watchful figure holding a rifle. The whole work is loosely painted with shadowy hues that occasionally are marked with glimmering highlights of color. Just a few years earlier, in 1899, Remington had seen an exhibition of nocturnal scenes by the California artist Charles Rollo Peters at the Union League Club. Inspired by that exhibition, Remington began to experiment with a more narrow and muted color range in some of his paintings, including 'The Old Stage Coach of the Plains'. Gradually, as he does here, Remington began to eliminate detail from his works in favor of a more general mood and atmosphere. In this painting, the viewer senses a feeling of tension and foreboding, evoked not only by the artist's use of subject matter, but also color and form.

In the final bronze version of 'The Outlaw', as can be seen here, both of the horse's front legs are attached to the base. During Remington's lifetime, approximately fifteen casts were produced; beyond that, it is estimated that another twenty-five were made. For Remington, the success of this composition depended on the carefully contrived degree of pitch of the horse and rider relative to the base. If the figures were not balanced just beyond the perceived center of gravity, the sculpture would lose the sense of forward movement. The unnumbered cast reproduced here is a posthumous cast that lacks the refinements of a lifetime example. The horse and rider pitch too far forward; textural details are largely absent, and certain elements such as the horse's mane or the foliage on the base are oddly stylized.

Remington completed an initial version of 'The Rattlesnake' in January 1905, and he was immensely pleased with its daring off-balance composition. However, three years later, after ten casts were produced, he grew dissatisfied with the original design, reworking the plaster model into a larger, more massive form. The changes included tucking the horse's forelegs and straightening its rear legs, thus increasing the tension of the animal's pose, and thrusting the rider forward so he became more integral with the sidelong motion of the composition. It is estimated that only four casts were completed under his supervision.

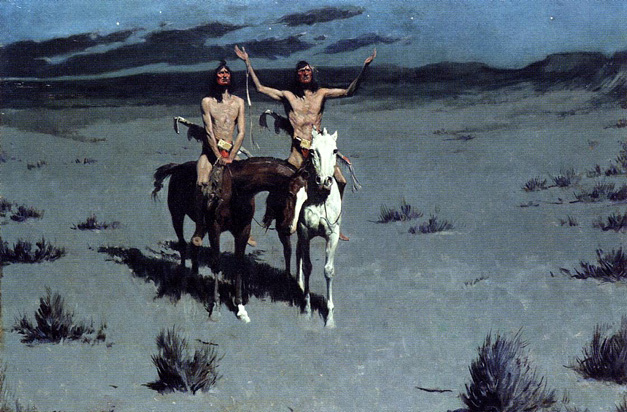

_1900.jpg)

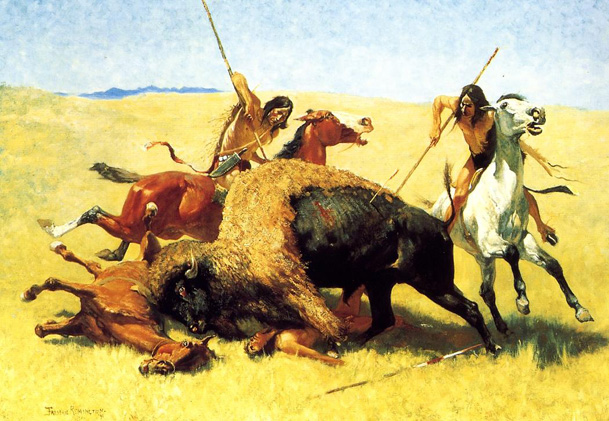

The Indians in Remington's painting have stripped themselves to essential clothing and weapons and have tied their horses' tails with feathers-indications that they are on a war expedition. The red handprint on the white horse's rump signified to some plains tribes that its rider had "ridden over an enemy" in battle. Despite Remington's customary attention to detail, there seem to be some mistakes. The high pommels and cantles on the saddles mark them as women's saddles, rather than those used by men. Also, the warrior on the left has a single-edged knife in a tack-decorated sheath; it looks more like a typical woman's skinning knife than the two-edged "beaver tail" knife that were favored by the men of the tribe.

Finally the remaining Cheyenne retreated to well-fortified bluffs for a last stand. "Within nine feet of the pits was a rim-rock ledge over which the Indian bullets swept, and here the charge was stopped," Remington wrote. "It now became a duel. Every time a head showed on either side, it drew fire like a flue hole." Suddenly, Sergeant Johnson "sprang on the ledge, and like a trill on a piano poured a six-shooter into the entrenchment, and dropped back." He soon found himself in a duel with a warrior named White Antelope, who answered the sergeant volley for volley, until "through the smoke sprang the daring soldier" to deliver the fatal bullets to his worthy adversary. Remington considered Johnson's bravery the high point of the bloody conflict and immortalized it in this painting, but his story also goes on to record Johnson's disgust at a victory over an embattled, outnumbered enemy that included many helpless victims. He was repelled by the many bodies laying "writhed and twisted on the packed snow, among them many women and children, cut and furrowed with lead."

.jpg)

_ca_1892_93.jpg)

The horrific experiences of the Spanish-American War (1898), in which Remington served as an artist-correspondent, seem to have left him with a heightened sympathy for Indians and their imperiled way of life. "When His Heart Is Bad," painted in 1908, a year before Remington's own death, shows an aged Indian warrior, seated alone on a hillside, silhouetted against the setting sun.

Source: Art Renewal Center

Source: Frederic Remington Online

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.