American Naturalist Painter, Engraver, Etcher & Illustrator

1836 - 1910

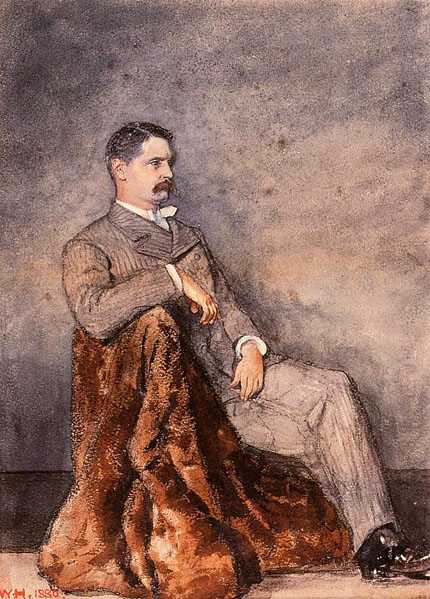

Winslow Homer was an American landscape painter and printmaker, best known for his marine subjects. He is considered one of the foremost painters in 19th century America and a preeminent figure in American art.

Largely self-taught, Homer began his career working as a commercial illustrator. He subsequently took up oil painting and produced major studio works characterized by the weight and density he exploited from the medium. He also worked extensively in watercolor, creating a fluid and prolific oeuvre, primarily chronicling his working vacations.

Born in Boston, Massachusetts in 1836, Homer was the second of three sons of Charles Savage Homer and Henrietta Benson Homer, both from long lines of New Englanders. His mother was a gifted amateur watercolorist and Homer's first teacher, and she and her son had a close relationship throughout their lives. Homer took on many of her traits, including her quiet, strong-willed, terse, sociable nature; her dry sense of humor; and her artistic talent. Homer had a happy childhood, growing up mostly in rural Cambridge, Massachusetts. He was an average student, but his art talent was on display early.

Homer's father was a volatile, restless businessman who was always looking to "make a killing". When Homer was thirteen, Charles gave up the hardware store business to seek a fortune in the California gold rush. When that failed, Charles left his family and went to Europe to raise capital for other get-rich-quick schemes that didn't materialize.

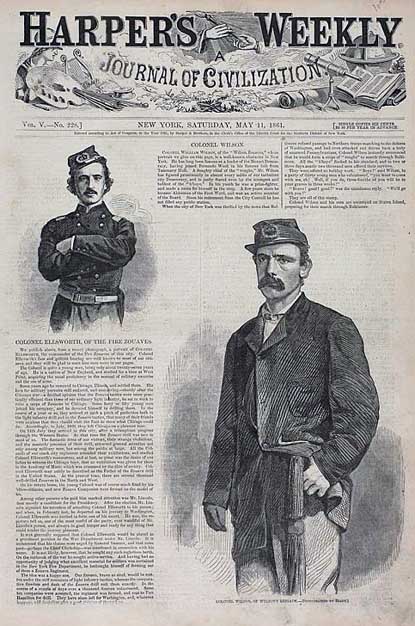

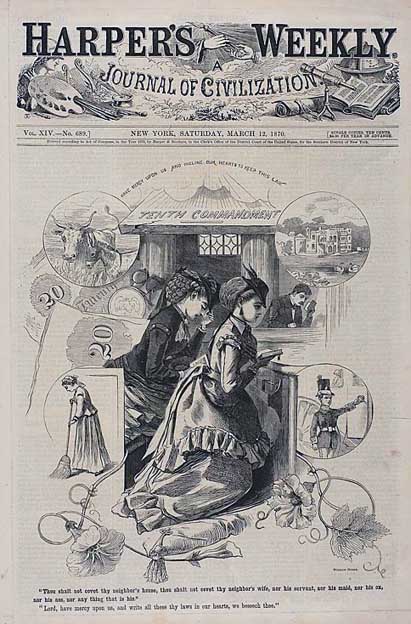

After Homer's high school graduation, his father saw an ad in the newspaper and arranged for an apprenticeship. Homer's apprenticeship to a Boston commercial lithographer at the age of 19 was a formative but "treadmill experience". He worked repetitively on sheet music covers and other commercial work for two years. By 1857, his freelance career was underway after he turned down an offer to join the staff of Harper's Weekly. "From the time I took my nose off that lithographic stone", Homer later stated, "I have had no master, and never shall have any."

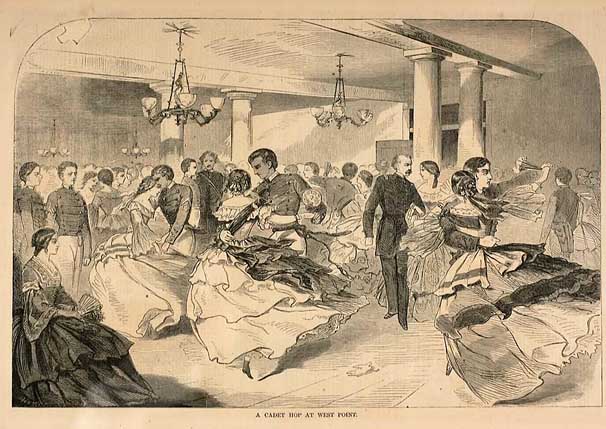

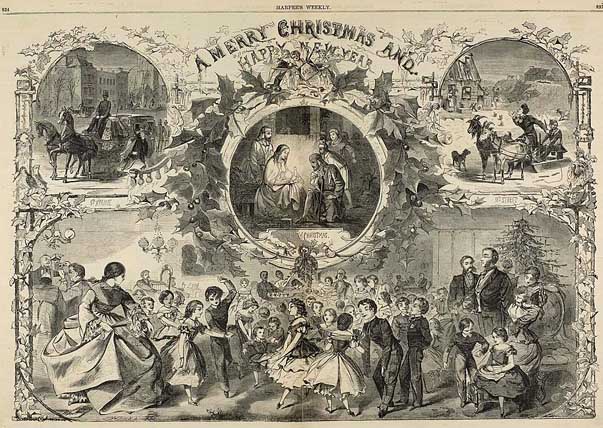

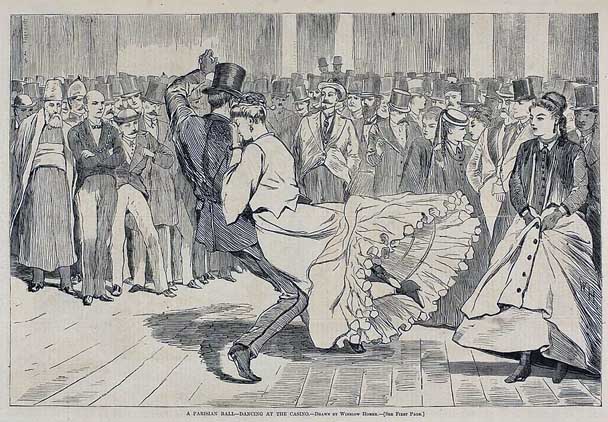

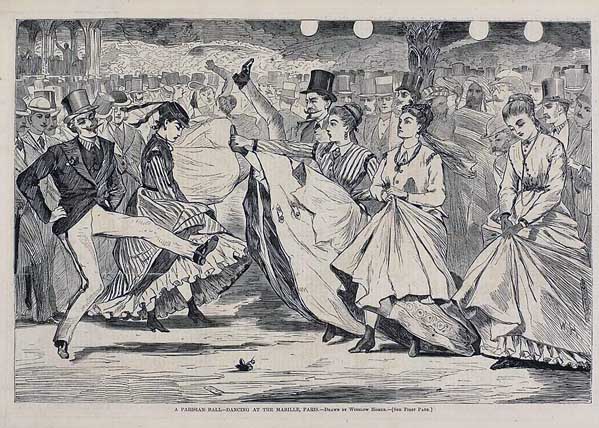

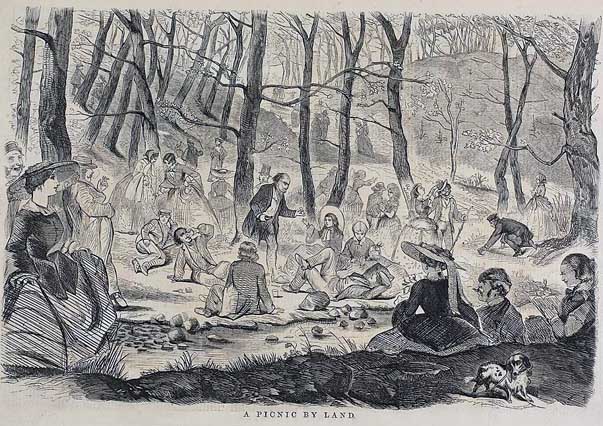

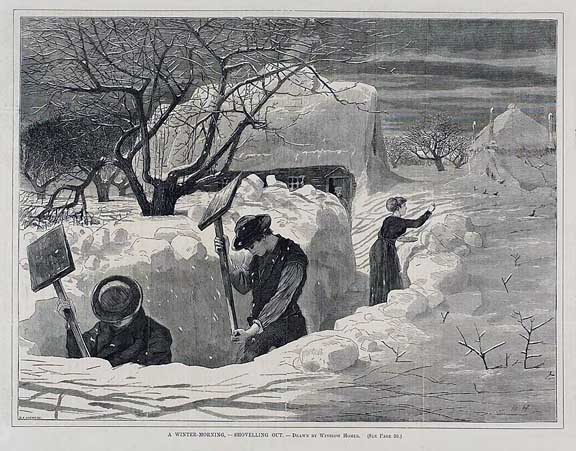

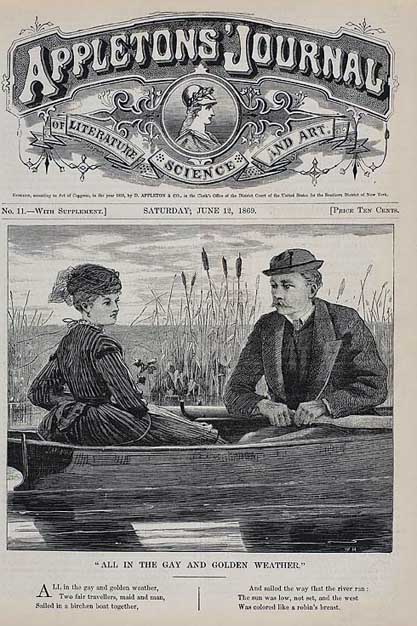

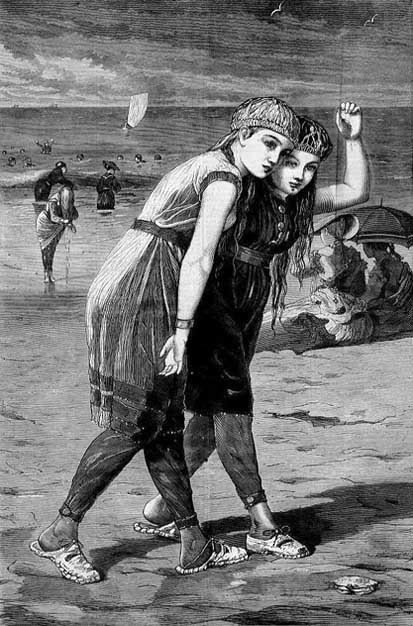

Homer's career as an illustrator lasted nearly twenty years. He contributed to magazines such as Ballou's Pictorial and Harper's Weekly, at a time when the market for illustrations was growing rapidly, and when fads and fashions were changing quickly. His early works, mostly commercial engravings of urban and country social scenes, are characterized by clean outlines, simplified forms, and dramatic contrast of light and dark, and lively figure groupings- qualities that remained important throughout his career. His quick success was mostly due to this strong understanding of graphic design and also to the adaptability of his designs to wood engraving.

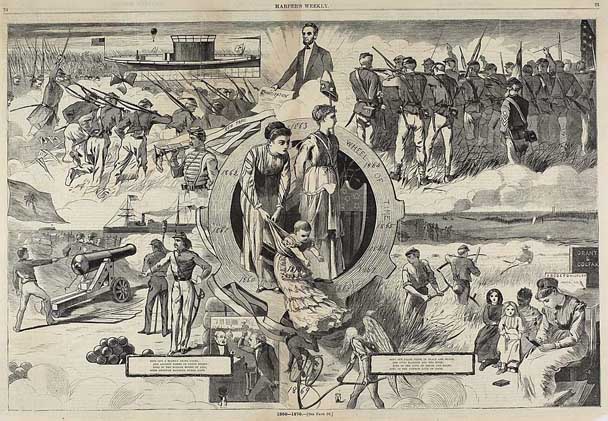

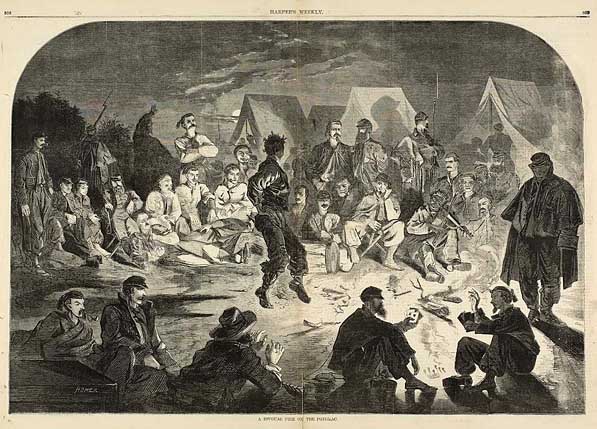

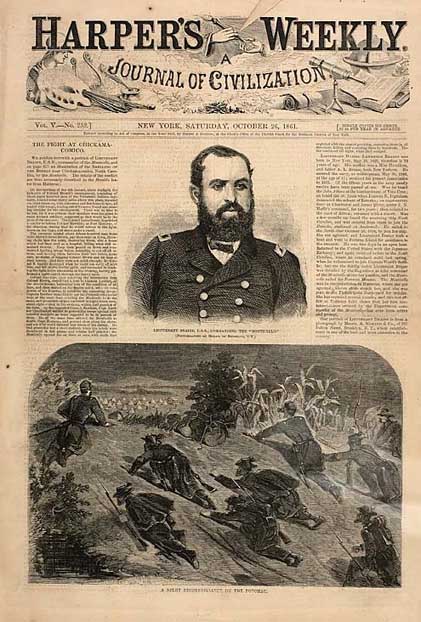

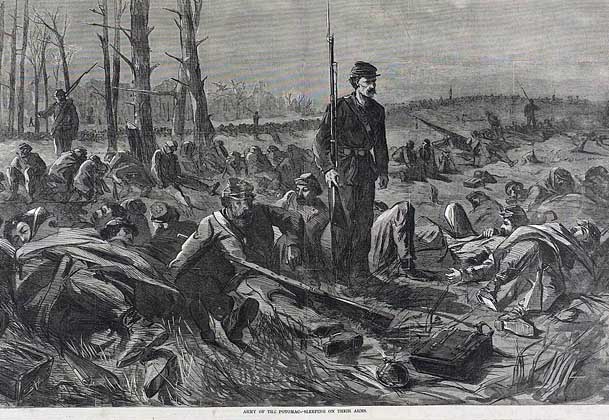

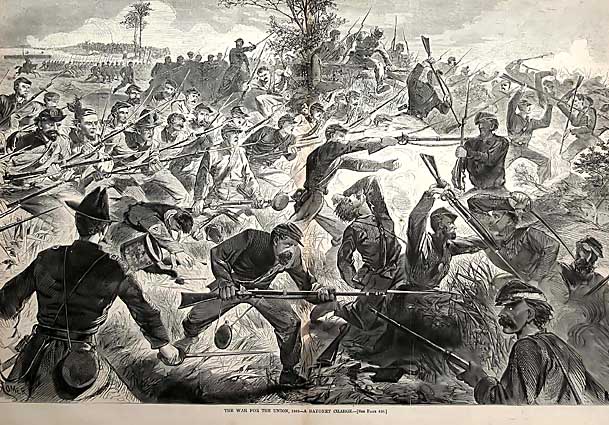

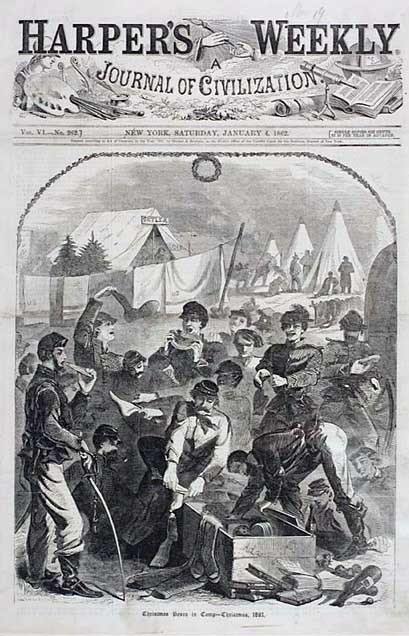

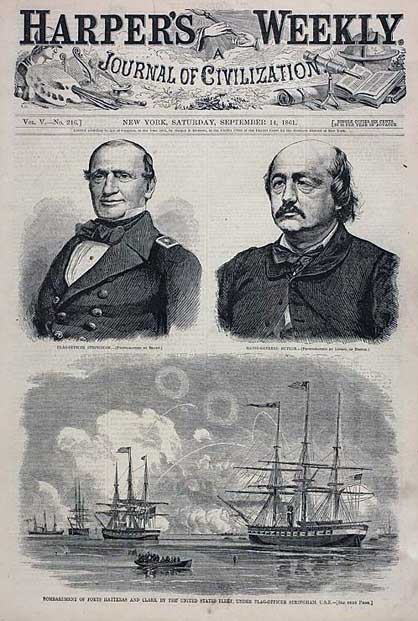

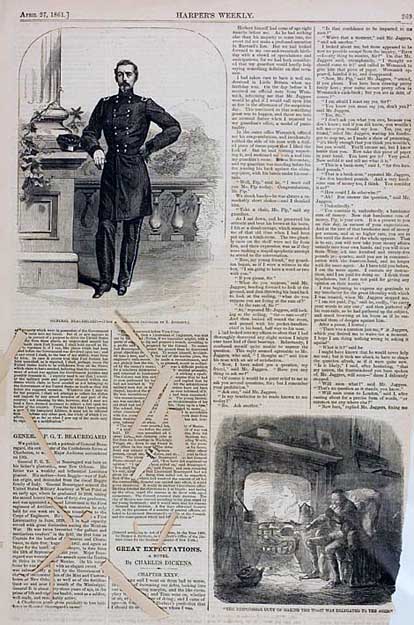

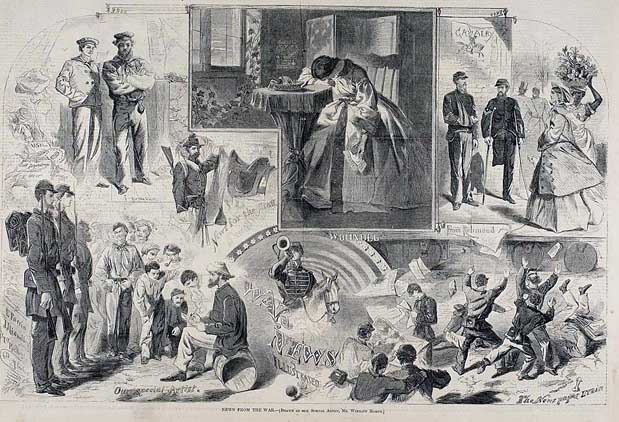

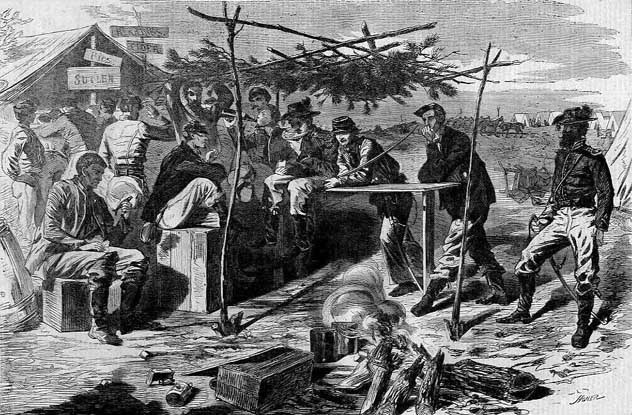

In 1859, he opened a studio in the Tenth Street Studio Building in New York City, the artistic and publishing capital of the United States. Until 1863 he attended classes at the National Academy of Design, and studied briefly with Frédéric Rondel, who taught him the basics of painting. In only about a year of self-training, Homer was producing excellent oil work. His mother tried to raise family funds to send him to Europe for further study but instead Harper's sent Homer to the front lines of the American Civil War (1861 - 1865), where he sketched battle scenes and camp life, the quiet moments as well as the murderous ones. His initial sketches were of the camp, commanders, and army of the famous Union officer, Major General George B. McClellan, at the banks of the Potomac River in October, 1861.

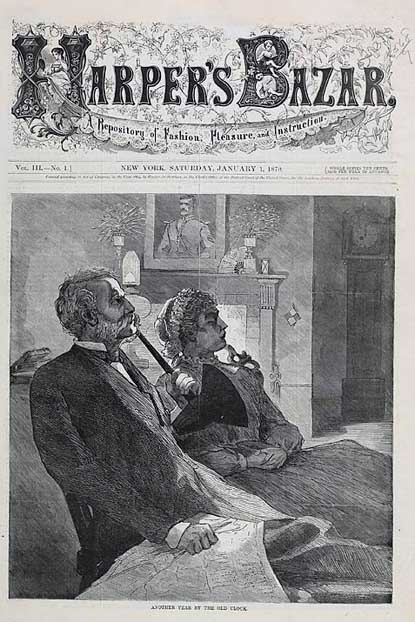

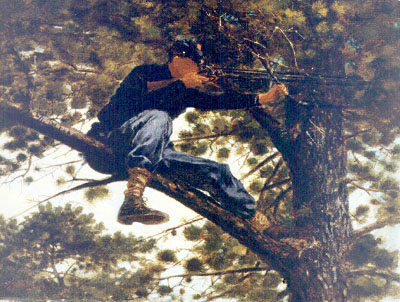

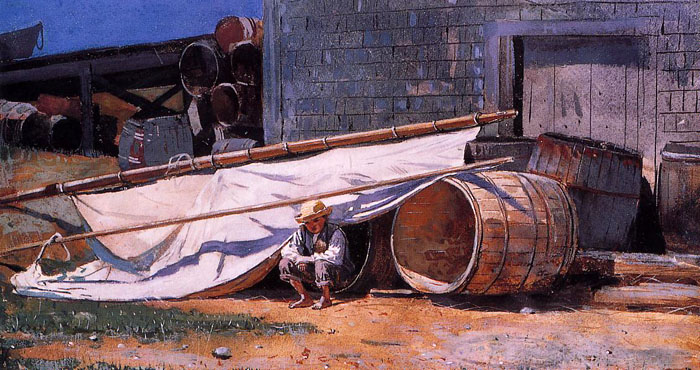

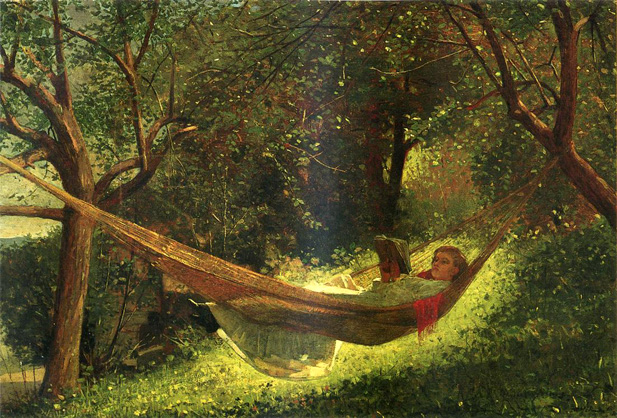

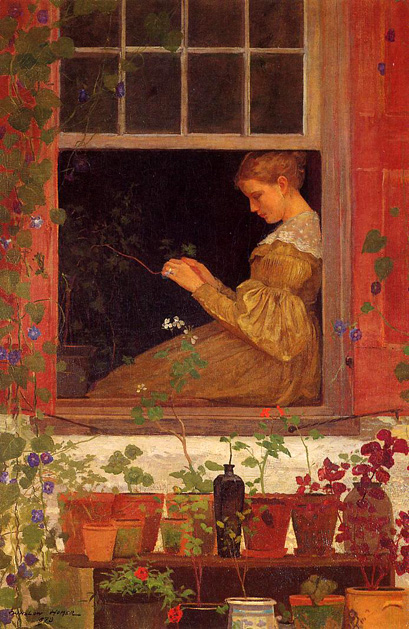

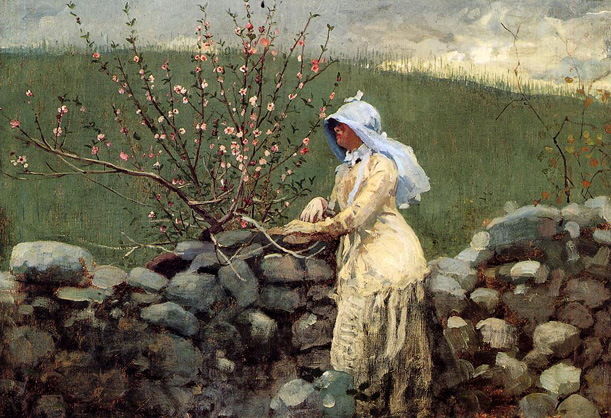

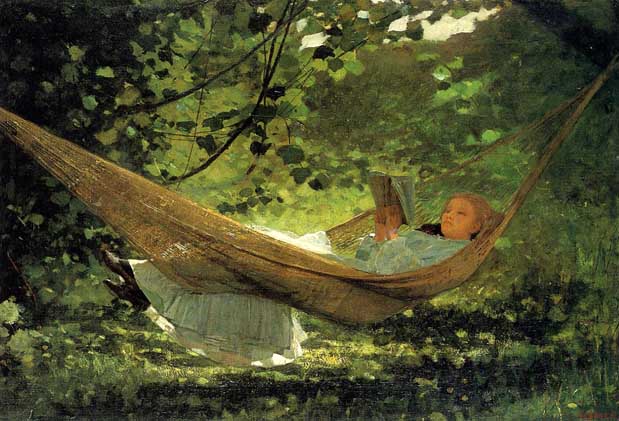

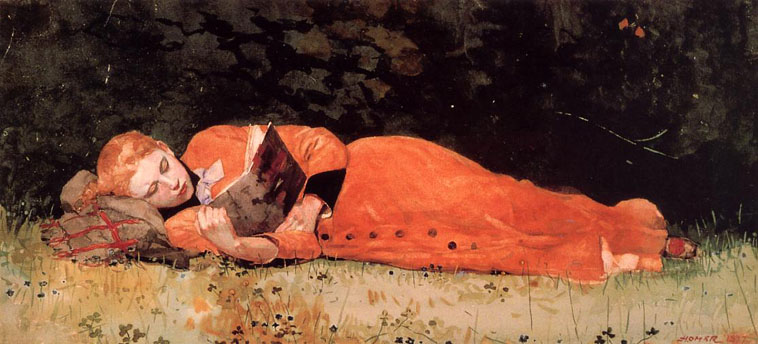

Although the drawings did not get much attention at the time, they mark Homer's expanding skills from illustrator to painter. Like with his urban scenes, Homer also illustrated women during war time, and showed the effects of the war on the home front. The war work was dangerous and exhausting. Back at his studio, however, Homer would regain his strength and re-focus his artistic vision. He set to work on a series of war-related paintings based on his sketches, among them Sharpshooter on Picket Duty (1862), Home, Sweet Home (1863), and Prisoners from the Front (1866). He exhibited Home, Sweet Home at the National Academy and its remarkable critical reception resulted in its quick sale and in the artist being elected an Associate Academician, then a full Academician in 1865. After the war, Homer turned his attention primarily to scenes of childhood and young women, reflecting his own, and the country's, nostalgia for simpler times.

.jpg)

The subject of this engraving is based on Homer's first oil painting. An emblematic image of the Civil War, the lone figure of a sharpshooter reveals the changing nature of modern warfare. With new, mass-produced weapons such as rifled muskets, killing became distant, impersonal, and efficiently deadly. Despite public admiration for sharpshooters' skill, ordinary soldiers looked upon them as cold-blooded, mechanical killers. Many years after the war, Homer wrote an old friend, "I looked through one of their rifles once....The...impression struck me as being as near murder as anything I could think of in connection with the army and I always had a horror of that branch of the service."

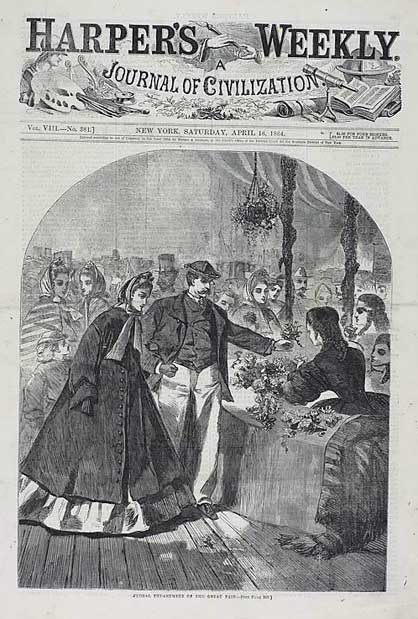

This picture, exhibited in New York in 1863, was enthusiastically admired and quickly sold. The title refers to the song frequently played by the Union regimental band, a piece that no doubt inspired homesickness and longing in the infantry men who listened to it.

But the title also refers to the soldiers' present "home," shown with all of its domestic details-a small pot on a smoky fire, hard biscuits on a tin plate-that Homer, who did the cooking and washing when he was on the front, knew intimately, and that, with surely intended irony, was far from "sweet."

At nearly the beginning of his painting career, the twenty-seven year old Homer demonstrated a maturity of feeling, depth of perception, and mastery of technique which was immediately recognized. His realism was objective, true to nature, and emotionally controlled. One critic wrote, "Winslow Homer is one of those few young artists who make a decided impression of their power with their very first contributions to the Academy...He at this moment wields a better pencil, models better, colors better, than many whom, were it not improper, we could mention as regular contributors to the Academy." And of Home, Sweet Home specifically, "There is no clap-trap about it. The delicacy and strength of emotion which reign throughout this little picture are not surpassed in the whole exhibition." "It is a work of real feeling, soldiers in camp listening to the evening band, and thinking of the wives and darlings far away. There is no strained effect in it, no sentimentality, but a hearty, homely actuality, broadly, freely, and simply worked out."

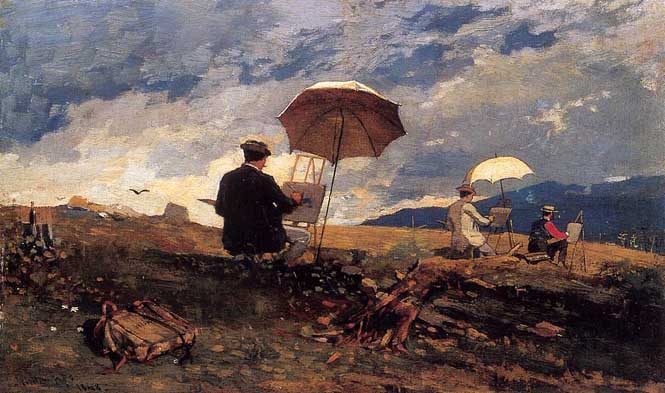

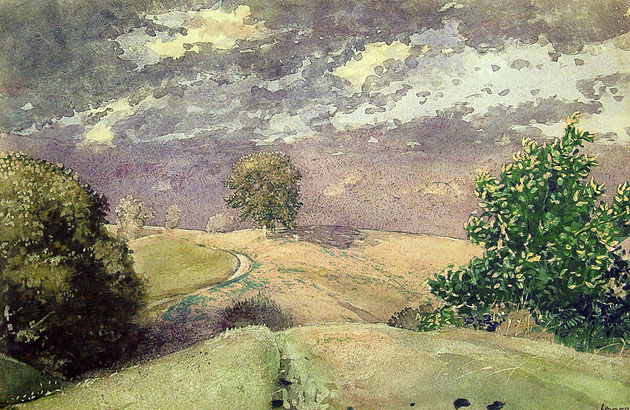

After exhibiting at the National Academy of Design, Homer finally traveled to Paris, France in 1867 where he remained for a year. His most praised early painting, Prisoners from the Front, was on exhibit at the Exposition Universelle in Paris at the same time. He did not study formally but he practiced landscape painting while continuing to work for Harper's, depicting scenes of Parisian life.

Homer painted about a dozen small paintings during the stay. Although he arrived in France at a time of new fashions in art, Homer's main subject for his paintings was peasant life, showing more of an alignment with the established French Barbizon School and the artist Millet, then with newer artists Manet and Courbet. Though his interest in depicting natural light parallels that of the early impressionists, there is no evidence of direct influence as he was already a plein-air painter in America and had already evolved a personal style which was much closer to Manet than Monet. Unfortunately, Homer was very private about his personal life and his methods (even denying his first biographer any personal information or commentary), but his stance was clearly one of independence of style and a devotion to American subjects. As his fellow artist Eugene Benson wrote, Homer believed that artists "should never look at pictures" but should "stutter in a language of their own."

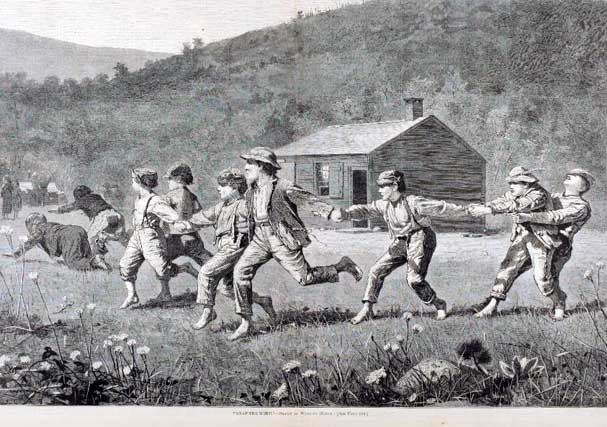

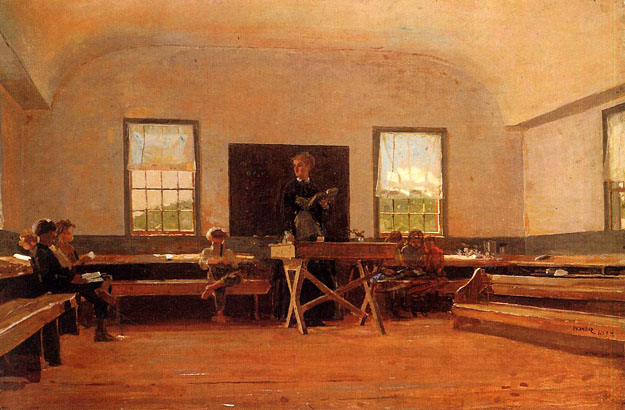

Throughout the 1870's Homer continued painting mostly rural or idyllic scenes of farm life, children playing, and young adults courting, including Country School (1871) and The Morning Bell (1872). In 1875, Homer quit working as a commercial illustrator and vowed to survive on his paintings and watercolors alone. Despite his excellent critical reputation, his finances continued to remain precarious. His popular 1872 painting, Snap-the-Whip, was exhibited at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, as was one of his finest and most famous paintings Breezing Up (1876). Of his work at this time, Henry James wrote:

_1872.jpg)

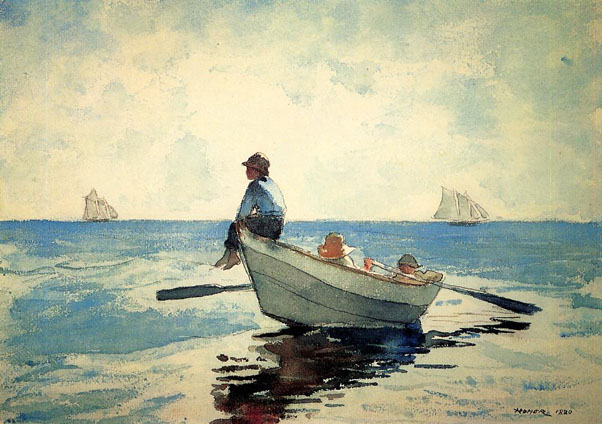

The apparent spontaneity bears out Homer's statement, "I try to paint truthfully what I see, and make no calculations." In actual practice, however, Homer did carefully calculate his compositions, including this one. The oil painting, exhibited to popular and critical acclaim in 1876, began with a watercolor study probably done on the spot three years earlier in Gloucester harbor.

Comparison with the initial watercolor and laboratory examination of this final oil reveal many changes in design. Originally, the tiller was guided by the old man instead of a boy. A fourth boy once sat in the place now occupied by the anchor, a symbol of hope. Because in 1876 the United States was celebrating its centennial as a nation, Homer may have made these alterations to suggest the promise of America's youth.

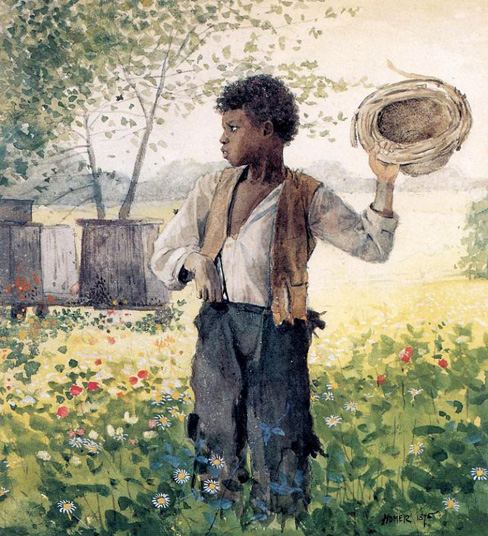

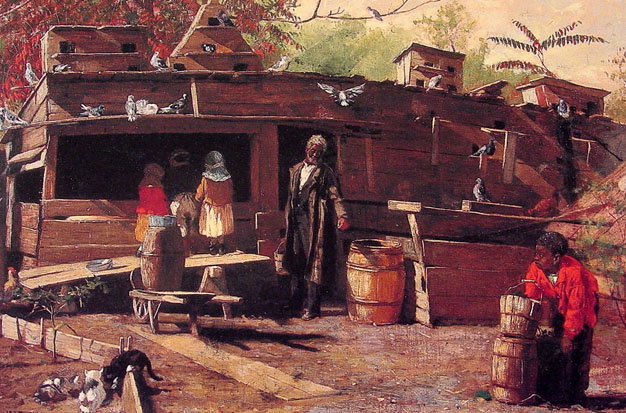

Many disagreed with James. Breezing Up, Homer's iconic painting of four boys out for a leisurely sail, received wide praise. The New York Tribune wrote, "There is no picture in this exhibition, nor can we remember when there has been a picture in any exhibition, that can be named alongside this." Visits to Petersburg, Virginia around 1876 resulted in paintings of rural African American life. The same straightforward sensibility which allowed Homer to distill art from these potentially sentimental subjects also yielded the most unaffected views of African American life at the time, as illustrated in Dressing for the Carnival (1877) and A Visit from the Old Mistress (1876).

In 1877, Homer exhibited for the first time at the Boston Art Club with the oil painting, An Afternoon Sun, (owned by the Artist). From 1877 through 1909 Homer exhibited often at the Boston Art Club. Works on paper, both drawings and watercolors, were frequently exhibited by Homer beginning in 1882. A most unusual sculpture by the Artist, Hunter with Dog - Northwoods, was exhibited in 1902. By that year Homer had switched his primary Gallery from the Boston based Doll and Richards to the New York City based Knoedler & Co.

Homer became a member of The Tile Club, a group of artists and writers who met frequently to exchange ideas and organize outings for painting, as well as foster the creation of decorative tiles. For a short time, he designed tiles for fireplaces. Homer's nickname in The Tile Club was "The Obtuse Bard". Other well known Tilers were painters William Merritt Chase, Arthur Quartley, and the sculptor Augustus Saint Gaudens.

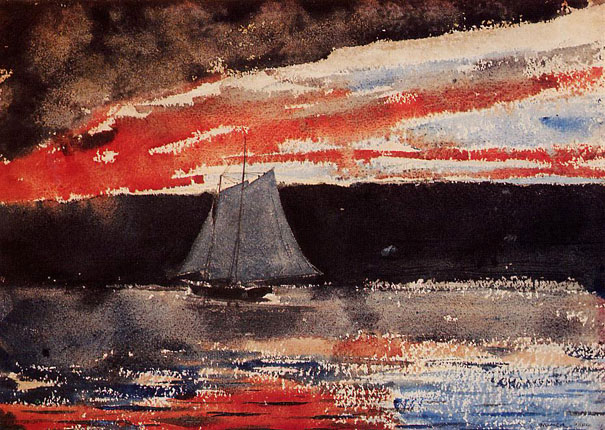

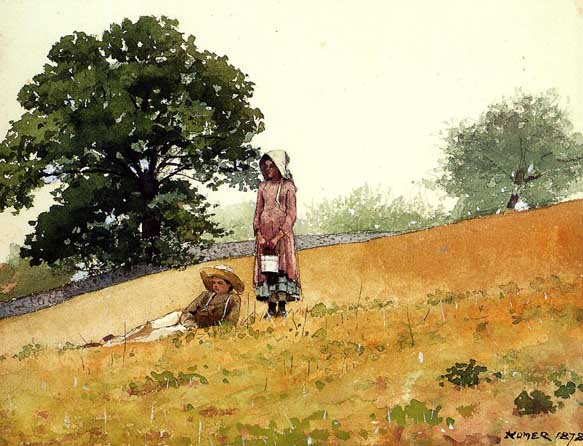

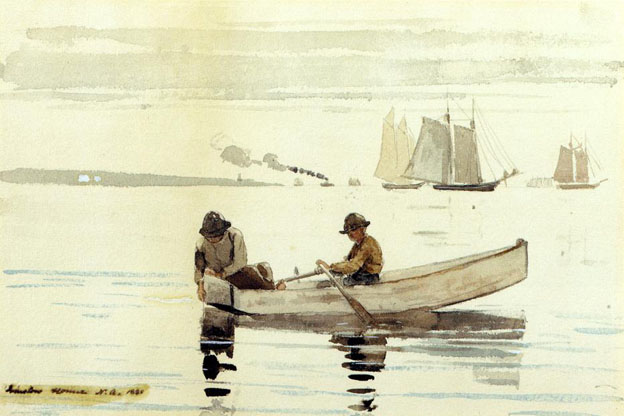

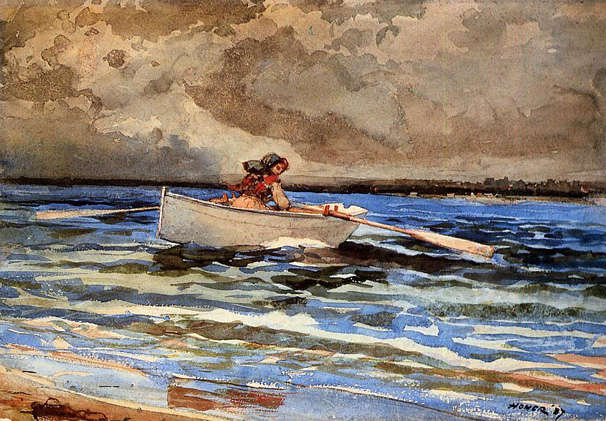

Homer started painting with watercolors on a regular basis in 1873 during a summer stay in Gloucester, Massachusetts. From the beginning, his technique was natural, fluid and confident, demonstrating his innate talent for a difficult medium. His impact would be revolutionary. Here, again, the critics were puzzled at first, "A child with an ink bottle could not have done worse." Another critic said that Homer "made a sudden and desperate plunge into water color painting". But his watercolors proved popular and enduring, and sold more readily, improving his financial condition considerably. They varied from highly detailed (Blackboard - 1877) to broadly impressionistic (Schooner at Sunset - 1880). Some watercolors were made as preparatory sketches for oil paintings (as for "Breezing Up") and some as finished works in themselves. Thereafter, he seldom traveled without paper, brushes and water based paints.

The marks on the blackboard puzzled scholars for many years. They now have been identified as belonging to a method of drawing instruction popular in American schools in the 1870's. In their earliest lessons, young children were taught to draw by forming simple combinations of lines, as seen on the blackboard here. Rather than being a polite accomplishment, drawing was viewed as having a practical application, playing a valuable role in industrial design. Homer playfully signed the blackboard in its lower-right corner as though with chalk.

As a result of disappointments with women or from some other emotional turmoil, Homer became reclusive in the late 1870's, no longer enjoying urban social life and living instead in Gloucester. For a while, he even lived in a lighthouse on an island (with the keeper's family). In re-establishing his love of the sea, Homer found a rich source of themes while closely observing the fishermen, the sea, and the marine weather. After 1880, he rarely featured genteel women at leisure, focusing instead on working women.

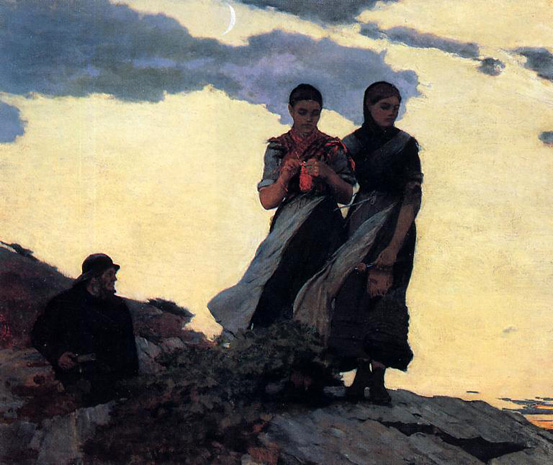

Homer spent two years (1881 - 1882) in the English coastal village of Cullercoats, Northumberland. Many of the paintings at Cullercoats took as their subjects working men and women and their daily heroism, imbued with a solidity and sobriety which was new to Homer's art, presaging the direction of his future work. He wrote, "The women are the working bees. Stout hardy creatures." His palette became constrained and sober; his paintings larger, more ambitious, and more deliberately conceived and executed. His subjects were more universal and less nationalistic, more heroic by virtue of his unsentimental rendering. Although he moved away from the spontaneity and bright innocence of the American paintings of the 1860's and 1870's, Homer found a new style and vision which carried his talent into new realms.

Back in the U.S. in November 1882, Homer showed his English watercolors in New York. Critics noticed the change in style at once, "He is a very different Homer from the one we knew in days gone by", now his pictures "touch a far higher plane...They are works of High Art." Homer's women were no longer "dolls who flaunt their millinery" but "sturdy, fearless, fit wives and mothers of men" who are fully capable of enduring the forces and vagaries of nature alongside their men.

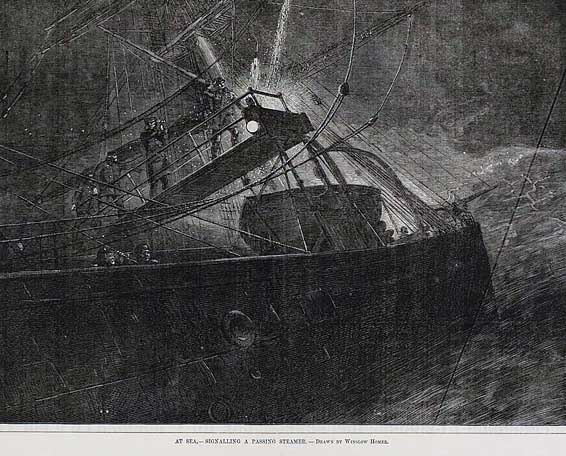

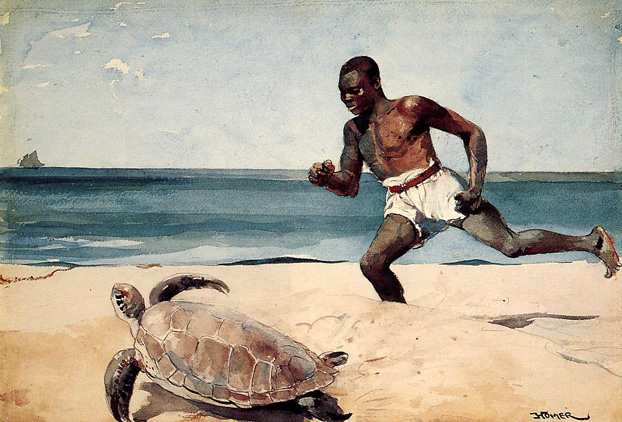

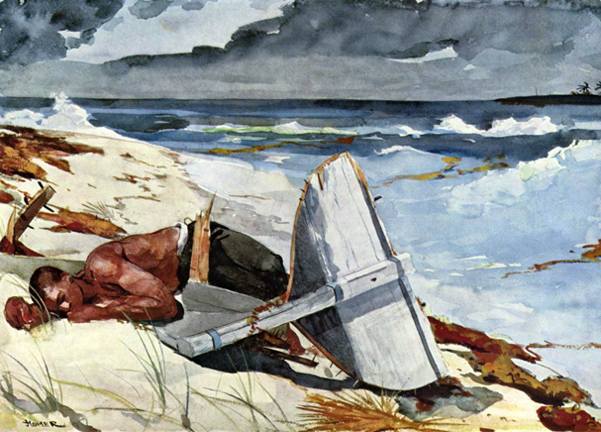

In 1883, Homer moved to Prout's Neck, Maine (in Scarborough) and lived at his family's estate in the remodeled carriage house just seventy-five feet from the ocean. During the rest of the mid-1880's, Homer painted his monumental sea scenes. InUndertow (1886), depicting the dramatic rescue of two female bathers by two male lifeguards, Homer's figures "have the weight and authority of classical figures". In Eight Bells (1886), two sailors carefully take their bearings on deck, calmly appraising their position and by extension, their relationship with the sea; they are confident in their seamanship but respectful of the forces before them. Other notable paintings among these dramatic struggle-with-nature images are Banks Fisherman, The Gulf Stream, Rum Cay, Mending the Nets, and Searchlight, Harbor Entrance, Santiago de Cuba. Some of these he repeated as etchings.

Homer's depiction seems to transcend "mere realism" and reveal an element of heroism in the mundane activities of his protagonists. A contemporary critic noted that the artist "has caught the color and motion of the greenish waves, white-capped and rolling, the strength of the dark clouds broken with a rift of sunlight, and the sturdy, manly character of the sailors at the rail. In short, he has seen and told in a strong painter's manner what there was of beauty and interest in the scene."

Although large steam trawlers had begun to replace smaller boats as fishing craft in Cullercoats, Homer preferred to focus on the old ways. In 'Mending the Nets', he conveys the idea of skills acquired through generations of families at work. Mending, along with dividing the catch and distributing the fish at market, occupied the fisherwomen's' time for most of the day.

The composition suggests Homer's familiarity with classical sculpture. The overlapping figures of the women create a compact group in a relatively shallow space, recalling relief sculpture such as the Parthenon friezes that Homer may have seen at the British Museum. The neutral background silhouettes the two figures starkly, emphasizing their strong sculptural quality. In this way, Homer presents these women at their daily tasks as timeless archetypes, imbued with a sober and noble simplicity.

At fifty years of age, Homer had become a "Yankee Robinson Crusoe, cloistered on his art island" and "a hermit with a brush". These paintings established Homer, as the New York Evening Post wrote, "in a place by himself as the most original and one of the strongest of American painters." But despite his critical recognition, Homer's work never achieved the popularity of traditional Salon pictures or of the flattering portraits by John Singer Sargent. Many of the sea pictures took years to sell and Undertow only earned him $400.

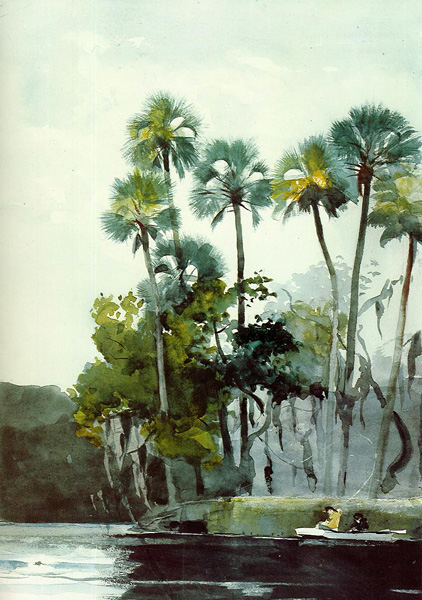

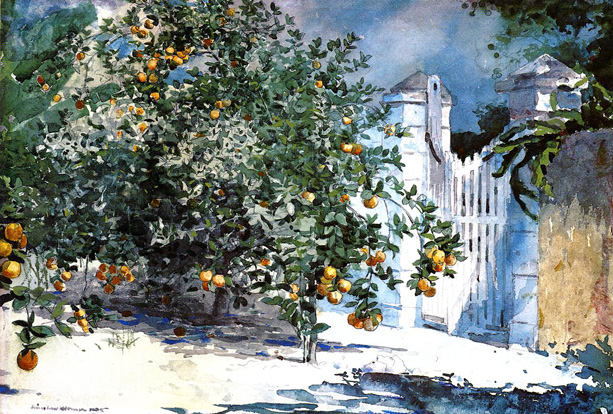

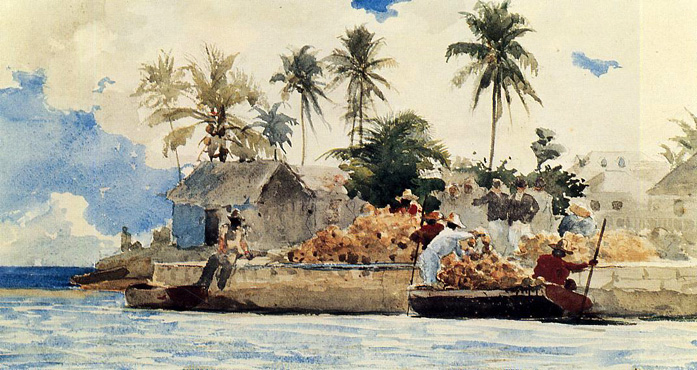

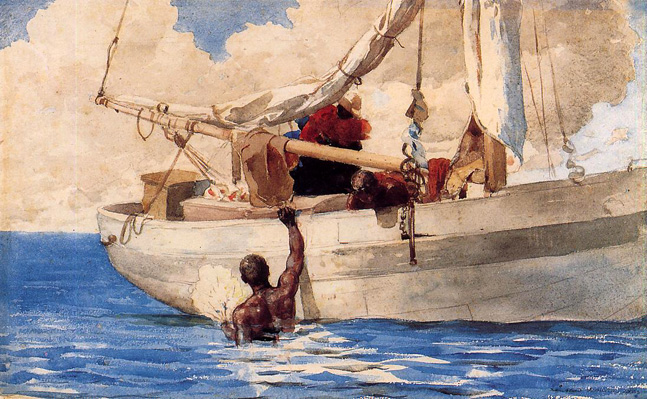

In these years, Homer received emotional sustenance primarily from his mother, brother Charles, and sister-in-law Martha ("Mattie"). After his mother's death, Homer became a "parent" for his aging but domineering father and Mattie became his closest female intimate. In the winters of 1884-5, Homer ventured to warmer locations in Florida, Cuba, and the Bahamas, and did a series of watercolors as part of a commission for Century Magazine. He replaced the turbulent green storm-tossed sea of Proust's Neck with the sparkling blue skies of the Caribbean, and the hardy New Englanders with the leisurely Black natives, further expanding his watercolor technique, subject matter, and palette. His tropical stays inspired and refreshed him in much the same way as Paul Gauguin's trips to Tahiti. A Garden in Nassau (1885) is one of the best examples of these watercolors. Once again, his freshness and originality were praised by critics, but proved too advanced for the traditional art buyers and he "looked in vain for profits." Homer lived frugally, however, and fortunately, his affluent brother Charles provided financial help when needed.

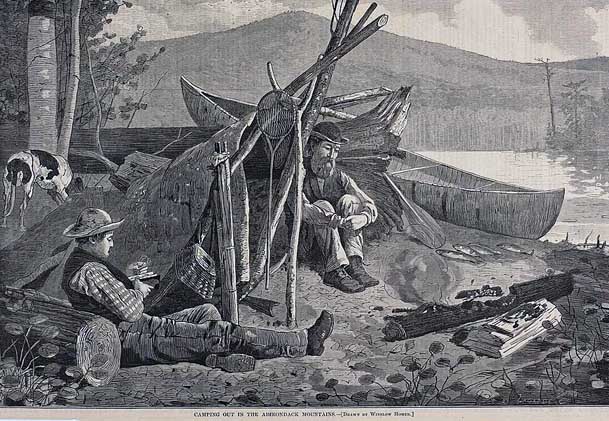

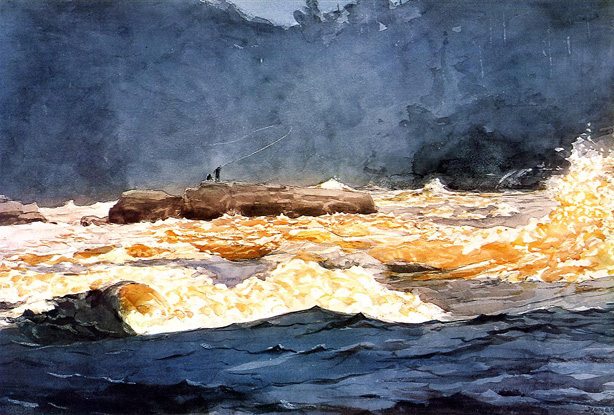

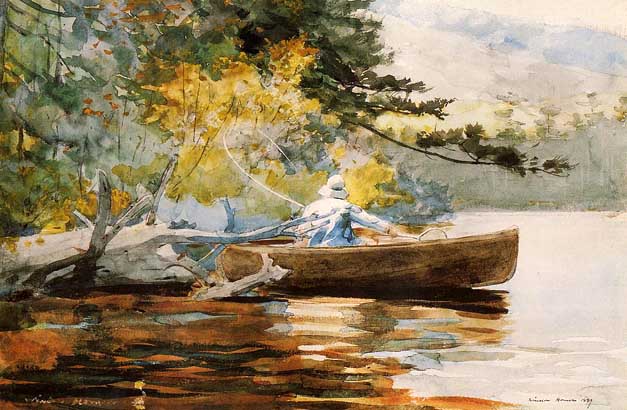

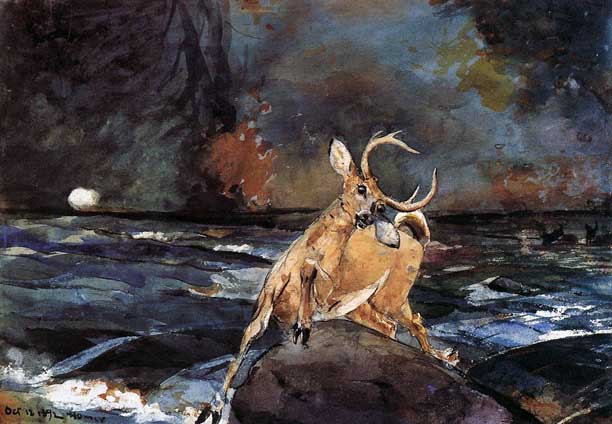

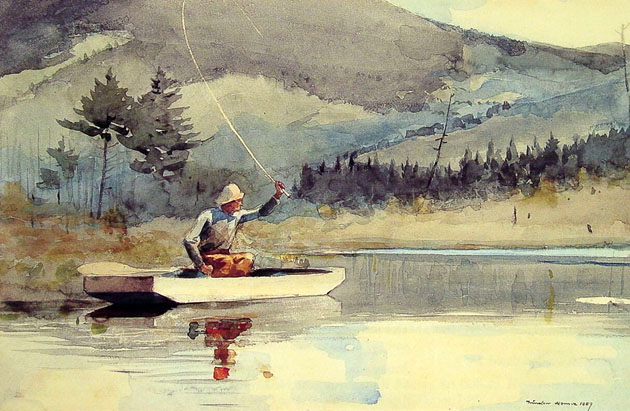

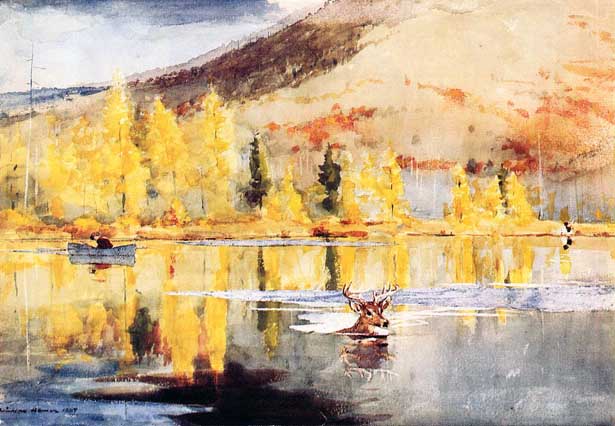

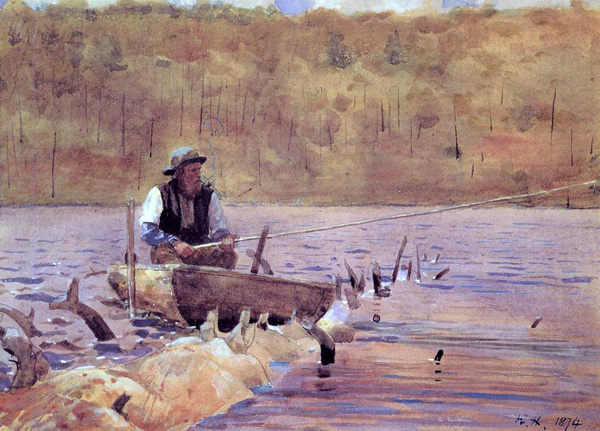

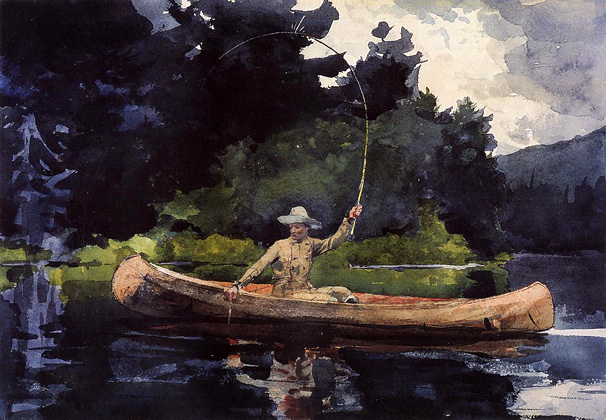

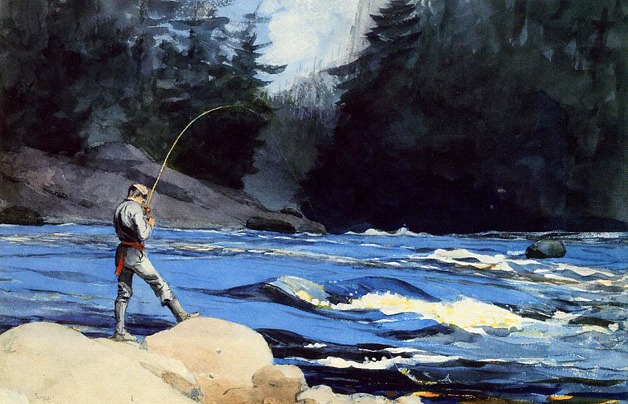

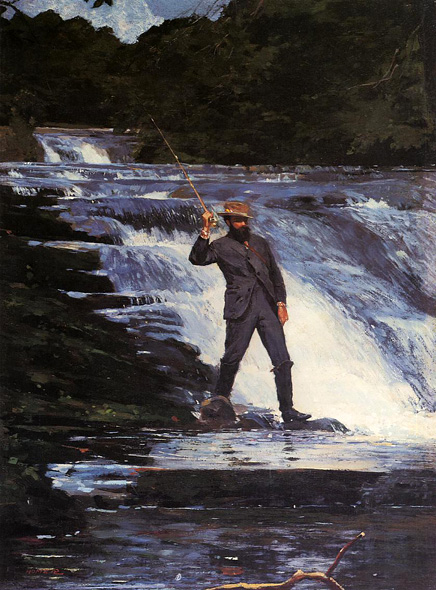

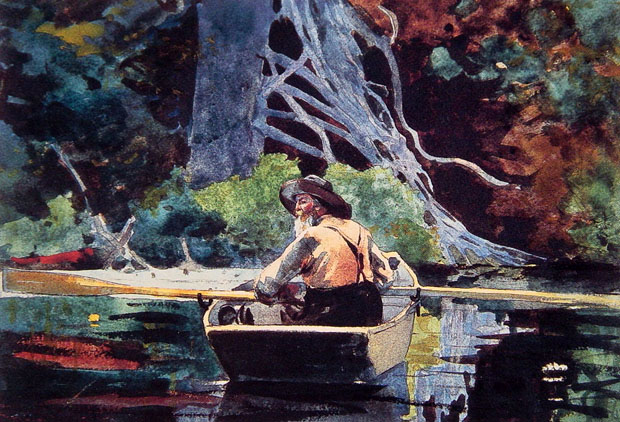

Additionally, Homer found inspiration in a number of summer trips to the North Woods Club, near the hamlet of Minerva, New York in the Adirondack Mountains. It was on these fishing vacations that he experimented freely with the watercolor medium, producing works of the utmost vigor and subtlety, hymns to solitude, nature, and to outdoor life. Homer doesn't shrink from the savagery of blood sports nor the struggle for survival. The color effects are boldly and easily applied. In terms of quality and invention, Homer's achievements as a watercolorist are unparalleled: "Homer had used his singular vision and manner of painting to create a body of work that has not been matched."

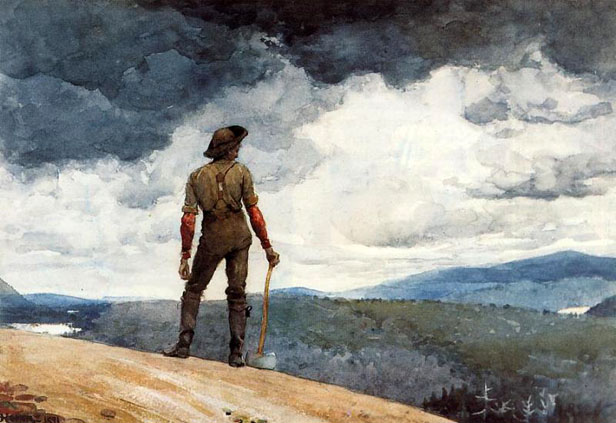

In 1893, Homer painted one of his most famous "Darwinian" works, The Fox Hunt, which depicts a flock of starving crows descending on a fox slowed by deep snow. This was Homer's largest painting and it was immediately purchased by the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, his first painting in a major American museum collection. In Huntsman and Dogs (1891), a lone, impassive hunter, with his yelping dogs at his side, heads home after a hunt, with deer skins slung over his right shoulder. Another late work, The Gulf Stream (1899), shows a Black sailor adrift in a damaged boat, surrounded by sharks and an impending maelstrom.

By 1900, Homer finally reached financial stability, as his paintings fetched good prices from museums and he began to receive rents from real estate properties. He also became free of the responsibilities of caring for his father who had died two years earlier. Homer continued producing excellent watercolors, mostly on trips to Canada and the Caribbean. Other late works include seascapes absent of human figures, mostly of waves crashing against rocks in varying light. In his last decade, he at times followed the advice he gave a student artist in 1907, "Leave rocks for your old age-they're easy".

Homer died in 1910 at the age of 74 in his Prout's Neck studio and was interred in the Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts. His painting, Shooting the Rapids, Saguenay River, remains unfinished.

His Prout's Neck studio is now owned by the Portland Museum of Art.

Homer never taught in a school or privately, as did Thomas Eakins, but his works strongly influenced succeeding generations of American painters for their direct and energetic interpretation of man's stoic relationship to an often neutral and sometimes harsh wilderness. Robert Henri called Homer's work an "integrity of nature."

American illustrator and teacher Howard Pyle revered Homer and encouraged his students to study him. His student and fellow illustrator, N. C. Wyeth (and through him Andrew Wyeth and Jamie Wyeth), shared the influence and appreciation, even following Homer to Maine for inspiration. The elder Wyeth's respect for his antecedent was "intense and absolute," and can be observed in his early work Mowing (1907). Perhaps Homer's austere individualism is best captured in his admonition to artists:

Contemporary commentators endorsed croquet as a socially approved physical activity for women, who had few other opportunities to exercise both body and mind in the open air, in public, and in mixed company. It could be played with equal facility by men and women, skill and ingenuity being much more important to success than mere physical strength. The young woman in blue is probably Homer's cousin Florence. The woman in red seems about to strike her own ball so that it hits another and gains her a point. The intended victim of the shot calmly adjusts her hat while waiting her turn.

As clicked and clacked

in an area of green grass

the croquet balls are clattered around

through silver rings of metal

by wooden sticks

with the ends looking of wooden cans

POP! the ball goes........

swish swish swish it continually rolls

until CLAT!

it is sprung off to the side of the metal ring

As the man of the game

suddenly peers at the sight of the stopped ball

trying to align the ball with its opponent

to clatter the two together as if again to repeat the process,

Dead stop!

the game is in a complete hault.

The women stand around

as not knowing what to do

gazing down at the man by their shoe

but before the man stands up

the ball stands up and cries

"please don't tap me just let me go!"

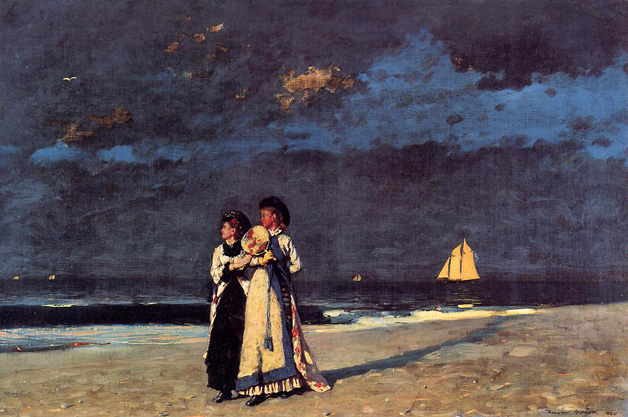

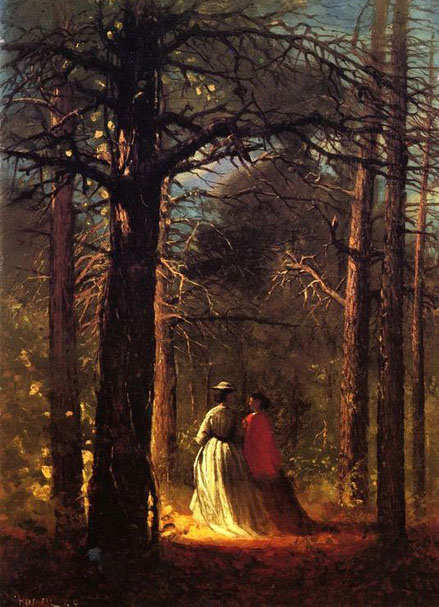

This nocturnal scene by the sea transcends observed reality through a keen sense of poetry and mystery. The light and shade effects blur shapes, while the ghostly silhouettes of two women dance on the shore. Although it may well have been influenced by Courbet's Waves, the lyricism tinged with mysticism expressed by Homer helped develop a feeling for nature that is peculiarly American.

During his stay in Cullercoats, Homer devoted much of his efforts to watercolor. Formerly held to be a genteel and somewhat frivolous medium better suited to women and amateurs, watercolor began gaining ground among American painters, including Homer, during the 1870's. In his Cullercoats paintings, Homer became one of the first to test the limits of watercolor, creating works of depth and power that could hold their own alongside works done in oil on canvas. In 'Fishwives', Homer saturates the paper with masses of somber color, creating a bold image that stands in stark contrast to the delicately tinted flower studies and landscapes that were typically associated with the medium.

'Fishwives' was one of the many gifts of art that Homer presented to his brother Charles Savage Homer Jr. Since the artist's death in 1910, it has been recognized as an important work and has appeared in a number of significant exhibitions, including Homer memorial exhibitions at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (both 1911), the Paris Exposition of 1923, and the Homer centennial exhibition of the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 1936. Most recently it was included in the major Homer retrospective staged by the National Gallery of Art in 1995-96. Following the death of Charles Homer's widow in 1937, Fishwives passed into the hands of relatives, from whom it was purchased by the Currier Museum of Art through the William Macbeth Gallery in 1938.

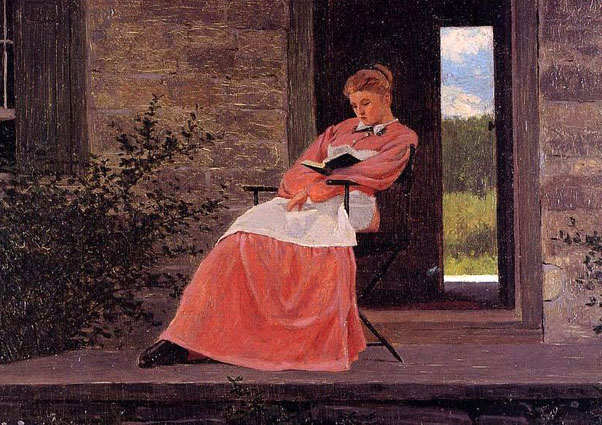

Homer often reused the same figures in different scenes. The girl in this work appeared previously in a drawing, an oil painting, and two watercolors. More generally, she is related to the many solitary figures of women that appear in Homer's work especially during the 1870's, including The Sick Chicken and Fresh Eggs.

Homer spent several months during the summer and late fall of 1878 at Houghton Farm, the country residence of a patron in Mountainville, New York. There he created dozens of watercolors of farm girls and boys playing and pursuing various tasks, including 'Warm Afternoon'. Painted quickly and often outdoors, these watercolors present idyllic scenes of rural life that follow in the European tradition of pastoral painting.

Once in the lake, the deer would be clubbed, shot, or drowned easily by hunters in boats. In Sketch for "Hound and Hunter," a young boy struggles to secure a dead deer while also attending to his dog. It was an unusual subject that many found disturbing; critics mistakenly believed that the hunter here was struggling to drown a live deer when in fact, as Homer explained, the deer was already dead.

Such hearty, industrious women were a constant source of inspiration to Homer. During the year and a half he remained in Cullercoats, the artist produced some of his most lyrically beautiful work. Sparrow Hall, wonderfully conceived, brightly colored, and superbly painted, stands very high among those works and indeed among Homer's images from any period. This is one of the few finished oils produced in Cullercoats; most of his work abroad was done in watercolor. Homer's stay in Cullercoats marked a critical turning point in the artist's career; upon his return to the United States, his painting took on a newfound sense of gravity and monumentality that would characterize his mature style.

Like many of his 1870's images featuring farm children, 'Fog Warning' is a story-telling picture. However, its story is disturbing rather than charming. As is indicated by the halibut in his dory, the fisherman in this picture has been successful. But the hardest task of the day, the return to the main ship, is still ahead of him. He turns to look at the horizon, measuring the distance to the mother ship, and to safety. The seas are choppy, and the dory rocks high on the waves, making it clear that the journey home will require considerable physical effort. But more threatening is the approaching fog bank, whose streamers echo-even mock-the fisherman's profile. Contemporary descriptions of the fishing industry in New England make clear that the protagonist's plight-the danger of losing sight of his vessel-was an all-too-familiar one.

The dramatic tension of 'Fog Warning' is all the greater because Homer does not specify the fisherman's fate. However, Homer's 'Lost on the Grand Banks', another painting in the series, shows that the fishermen's peril was a deadly one. An account from the 1876 history The Fisheries of Gloucester of the insidious horrors to which the fishermen were prey could well have served as a description of 'Fog Warning': "His frail boat rides like a shell upon the surface of the sea…a moment of carelessness or inattention, or a slight miscalculation, may cost him his life. And a greater foe than carelessness lies in wait for its prey. The stealthy fog enwraps him in its folds, blinds his vision, cuts off all marks to guide his course, and leaves him afloat in a measureless void."

This remarkably fertile period in Homer's career brought him great critical acclaim. The 'Life Line' was an immediate success, but Homer's work held little commercial appeal. Its striking composition and strong dramatic mood did not match the prevailing aesthetic taste. After viewing Homer's work in a National Academy exhibition, one critic remarked that his paintings had a "rude vigor and grim force that is almost a tonic in the midst of the namby-pambyism of many of the other pictures on display."

The size of this watercolor and its highly finished state suggest that Homer was attempting to create what English artists called "exhibition watercolors"-works that were intended to rival the aesthetic power and impact of oil paintings.

He created his first series in Gloucester, Massachusetts, in 1873, and by the time he painted his last watercolor, in 1905, he had become the unrivaled master of the medium in America.

Some critics found fault in Homer's early watercolors for their apparent lack of finish and their commonplace subject matter. Yet Homer valued them from the start. He priced 'The Sick Chicken', a delicate work that demonstrates his early technique of filling in outlined forms with washes of color, at the steep price of one hundred dollars.

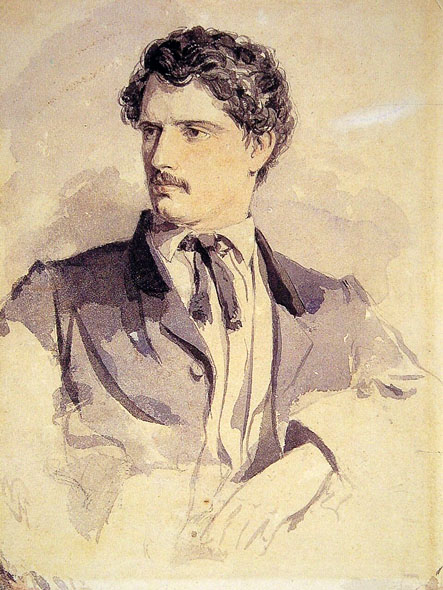

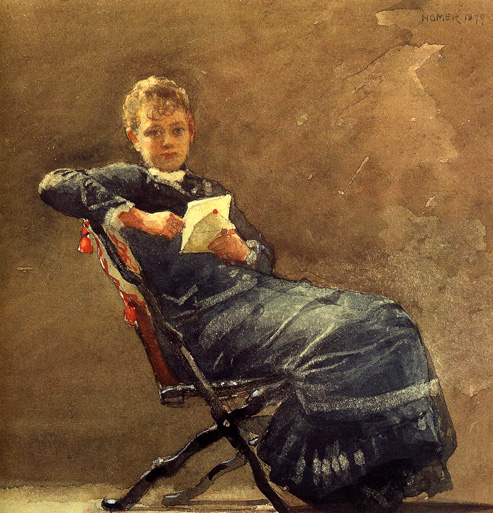

It is not certain when Homer's romantic interest in de Kay began to stir. He may already have had her on his mind in the summer of 1868 when he painted 'The Bridle Path' set in the White Mountains of New Hampshire. David Tatham has put forward a case for identifying the model as Martha Bennett Phelps of Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. Yet in 1873, Mary Hallock, then living in Milton in Ulster County, New York, wrote to de Kay saying that when her little nephew Gerald "looks at a photograph of 'The Bridle Path' he says 'Helena---ride--horseback.'--this is his own idea."

Although it is dated 1892, 'Watching from the Cliffs' does not relate to Homer's Adirondack and Florida watercolors of that period but returns to a subject dealt with in the watercolors made in England a decade earlier. Indeed, the central motif in this work, a woman with a child, occurs in an 1881 watercolor once owned by E. K. Warren. In that work the foreground was a grassy hillside with the same slope as in this one. The use of opaque white in 'Watching from the Cliffs' is highly unusual for Homer's work of the 1890's and is not generally found in his watercolors on white paper after the English period. The design also contains one odd inconsistency: the women's garments are shown swirling to the right, but the smoke from the house in the distance is shown blowing to the left.

Source: Art Renewal Center

Source: Winslow Homer Online

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.