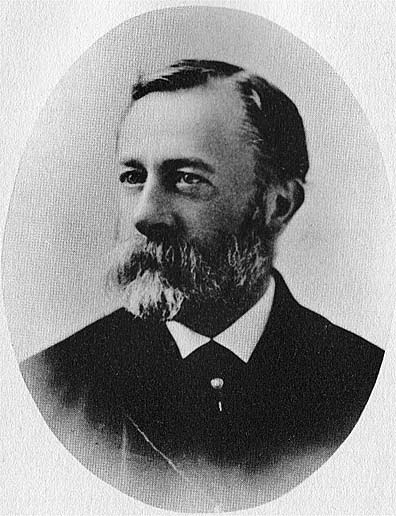

1830 - 1902

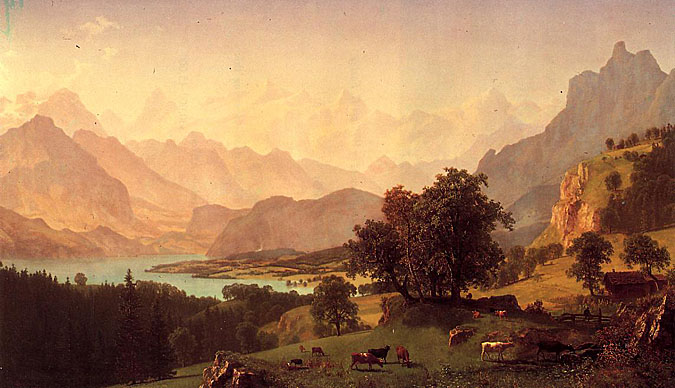

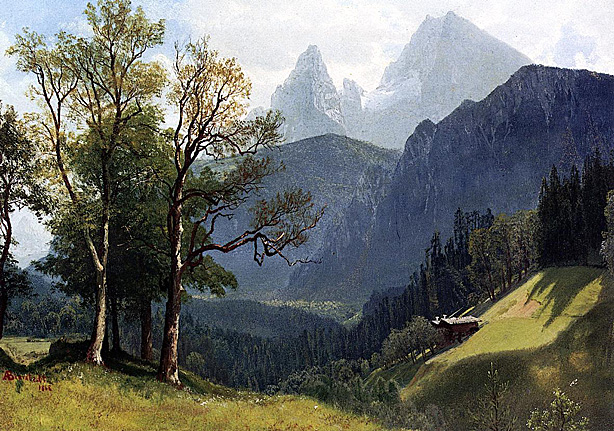

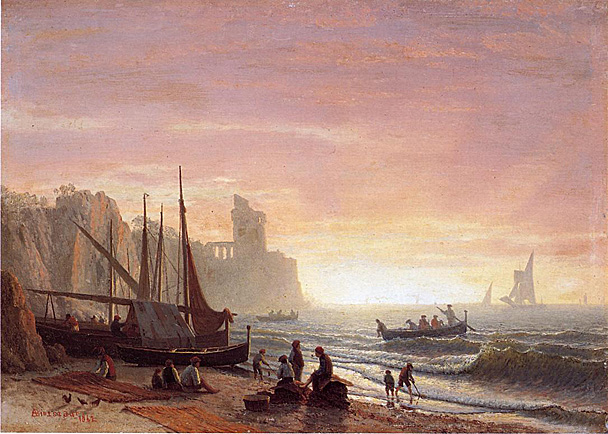

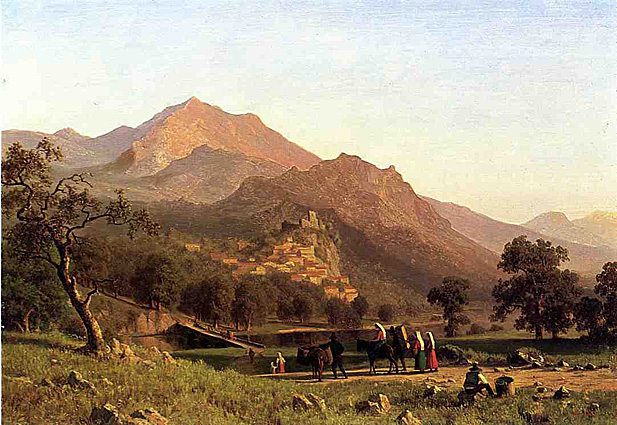

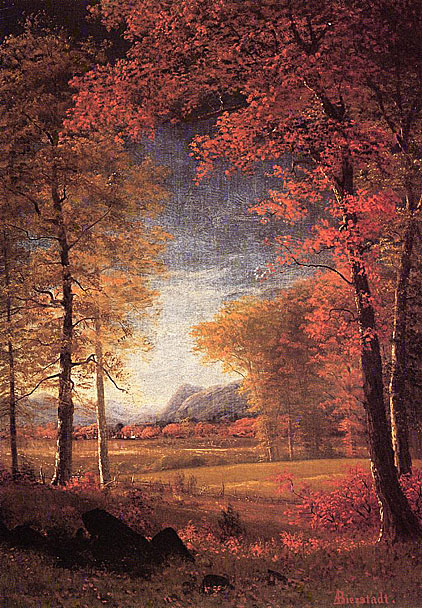

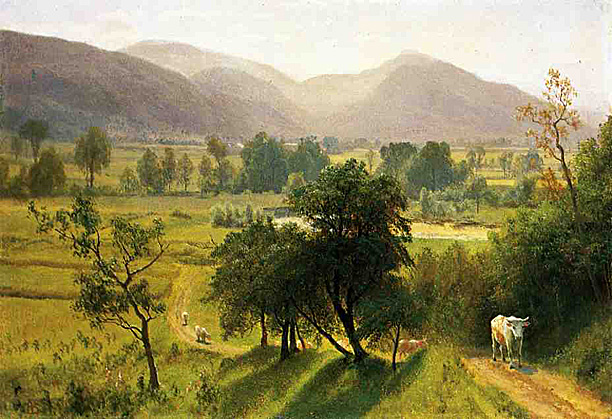

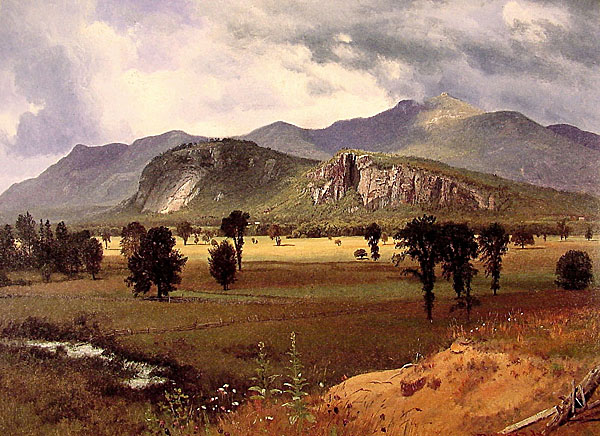

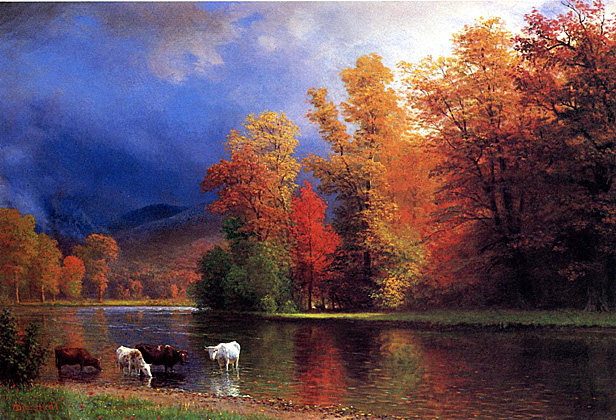

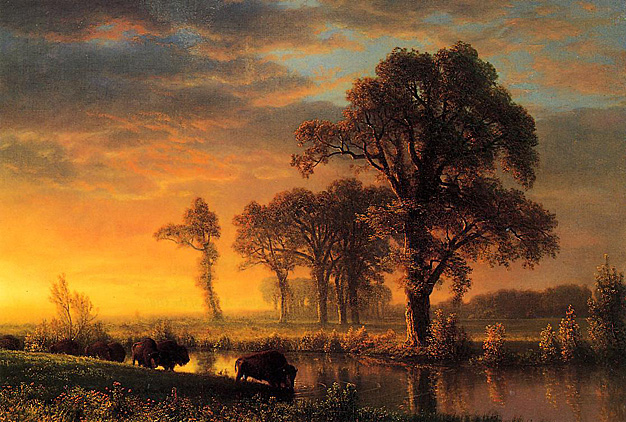

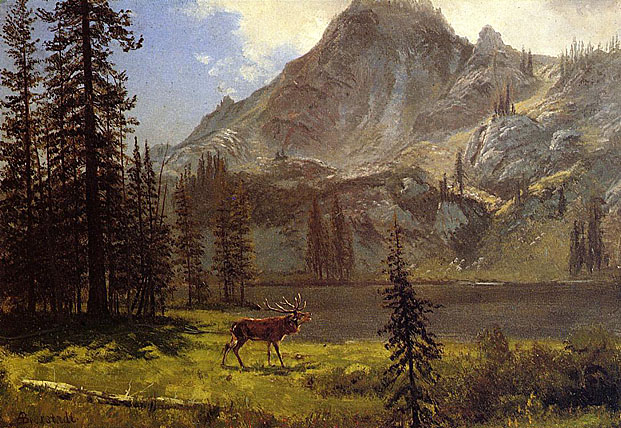

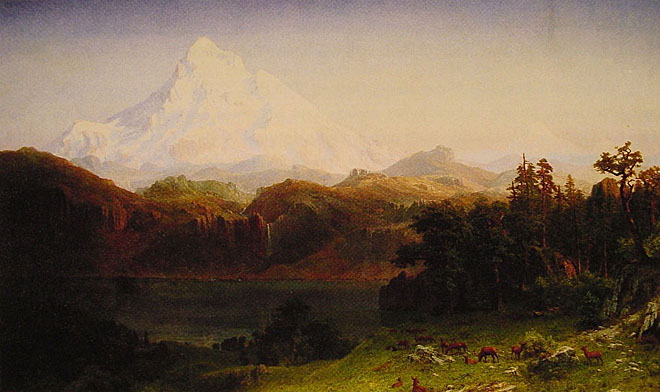

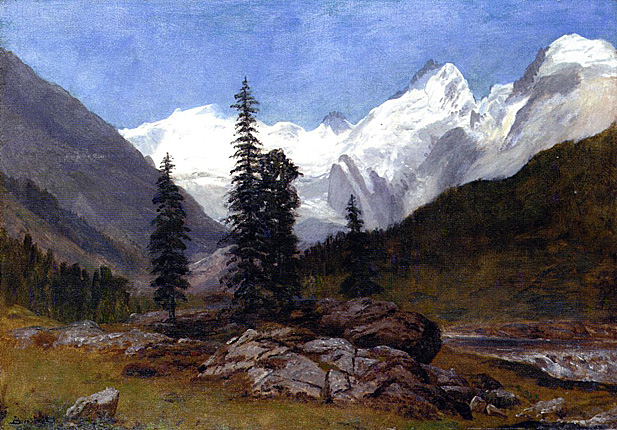

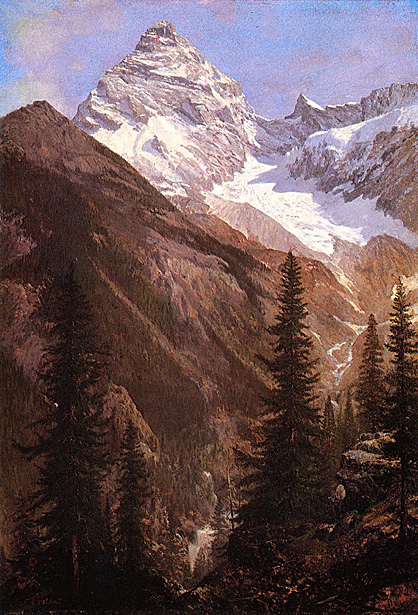

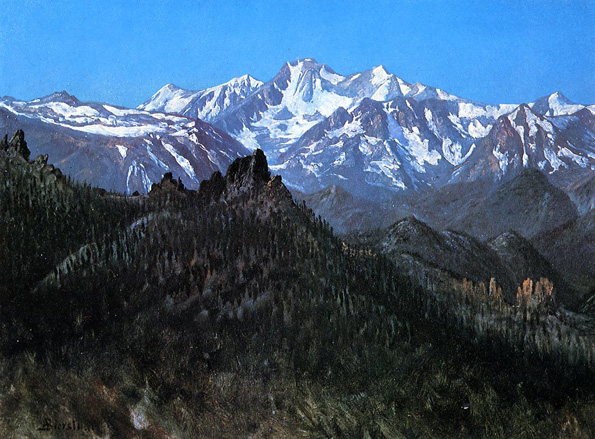

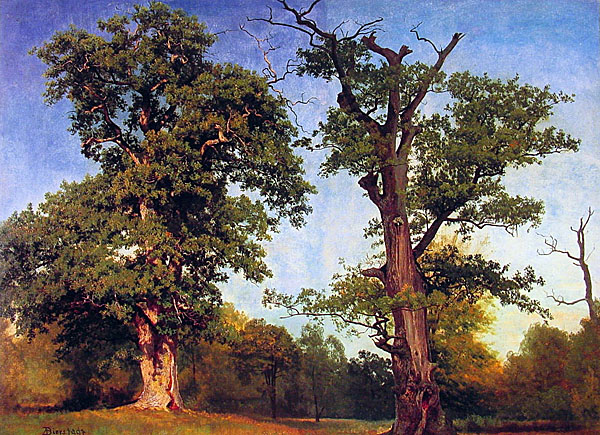

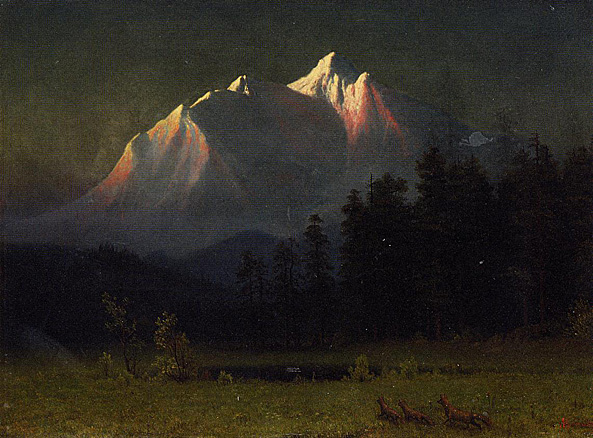

Bierstadt was part of the Hudson River School, not an institution but rather an informal group of like-minded painters. The Hudson River School style involved carefully detailed paintings with romantic, almost glowing lighting, sometimes called luminism.

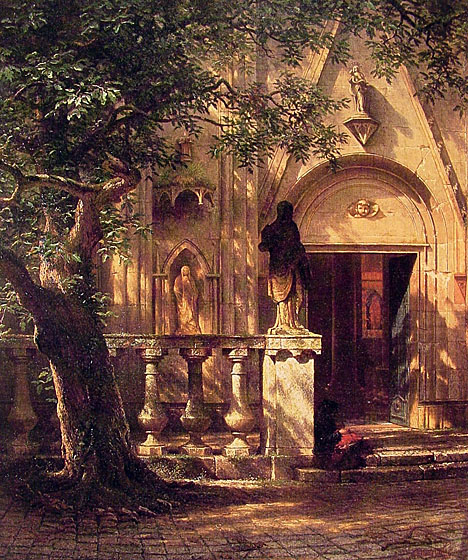

Bierstadt was born in Solingen, Germany. His family moved to New Bedford, Massachusetts, in 1833. He studied painting with the members of the Dusseldorf School in Dusseldorf, Germany from 1853 to 1857. He taught drawing and painting briefly before devoting himself to painting.

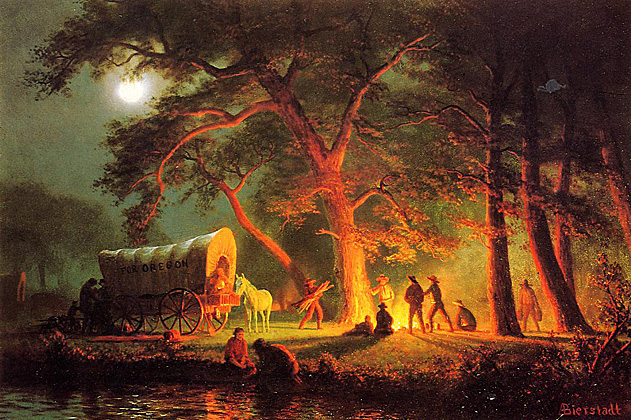

Bierstadt began making paintings in New England and upstate New York. In 1859, he traveled westward in the company of a Land Surveyor for the U.S. government, returning with sketches that would result in numerous finished paintings. In 1863 he returned West again, in the company of the author Fitz Hugh Ludlow, whose wife he would later marry. He continued to visit the American West throughout his career.

Yearly length change measurements have been recorded since 1878. For the period to 1998, the overall retreat was over 1.8 km with a mean annual retreat rate of approximately 17.2 m/y. This long-term average has markedly increased in recent years, receding 30 m/y from 1999-2005. Substantial retreat was ongoing through 2006 as well.

Long famed as a winter tourist destination with slopes for beginners, intermediates and the challenges of the Eiger glacier for the experienced, there are activities for the non-skiers, from tobogganing to groomed winter hiking tracks. It is the usual starting point for ascents of the Eiger and the Wetterhorn. Nowadays Grindelwald is also a popular summer activity resort with many miles of hiking trails across the Alps.

The Story and Prophecy

St. Thomas was born in 1225, in the Castle of Rocca Secca, perched high up in the mountains near the town of Aquinas, in Italy. His Father was Count of Aquinas and his Mother was Countess.

But before St. Thomas was born, a holy hermit known as Buono, went to the Castle of Rocca Secca and made a very great prophecy to his Mother. While speaking to the Countess he pointed to a picture of St. Dominic, (not yet canonized) saying, "Lady be glad, for you are about to have a son whom you will call Thomas. You and your husband will think of making him a monk in the Abbey of Mount Cassino (Benedictines), where lies the founder, St. Benedict, in the hopes that your son will attain to its honors and wealth. But God has disposed otherwise, because he will become a Friar of the Order of Preachers (Dominicans). And so great will be his learning and sanctity, that there will not be found in the whole world, another person like him!"

Countess Theodora was amazed at the prophecy and falling on her knees exclaimed, "I am most unworthy of bearing such a son, but God's will be done according to His good pleasure!"

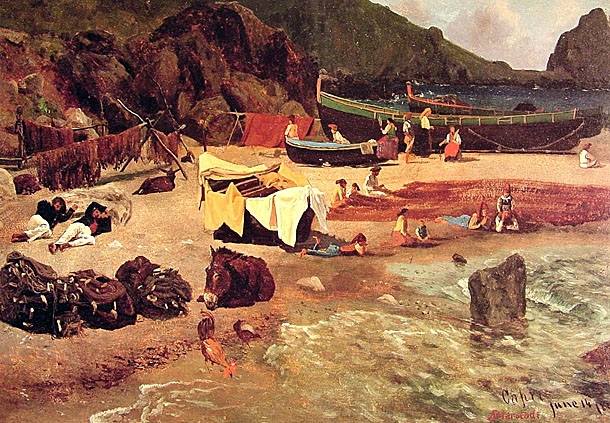

Features of the island are the Marina Piccola (Small Harbor), the Belvedere of Tragara, which is a high panoramic promenade lined with villas, the limestone masses that stand out of the sea (the Faraglioni), Anacapri, the Blue Grotto (Grotta Azzurra), and the ruins of the Imperial Roman villas.

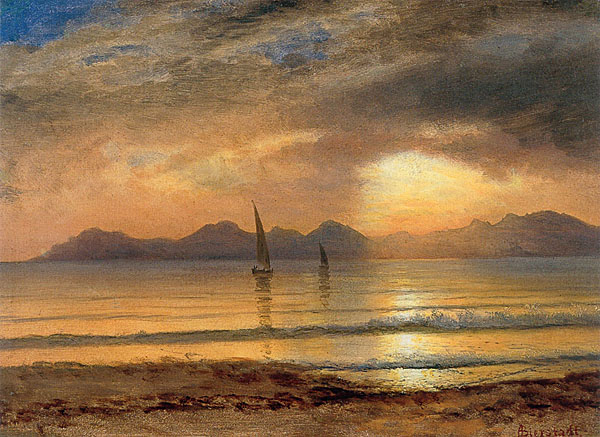

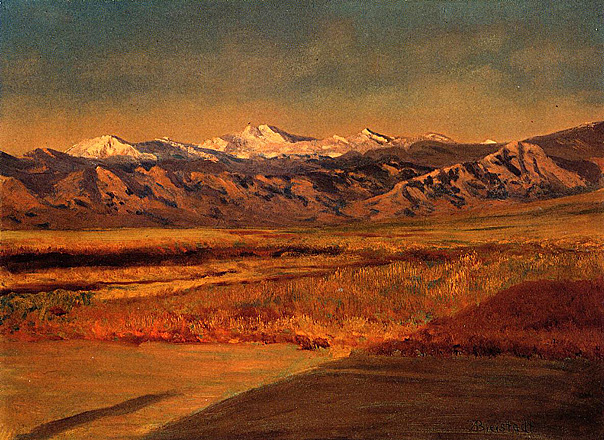

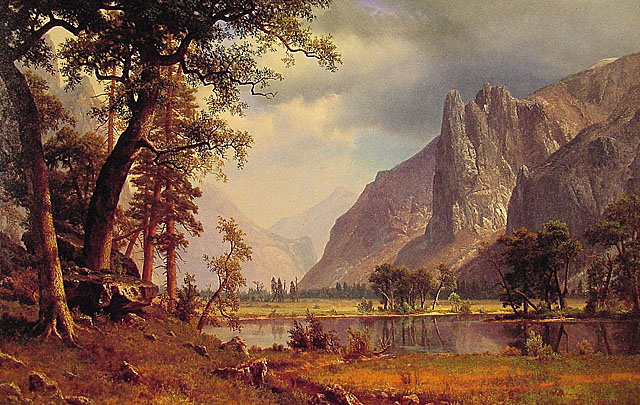

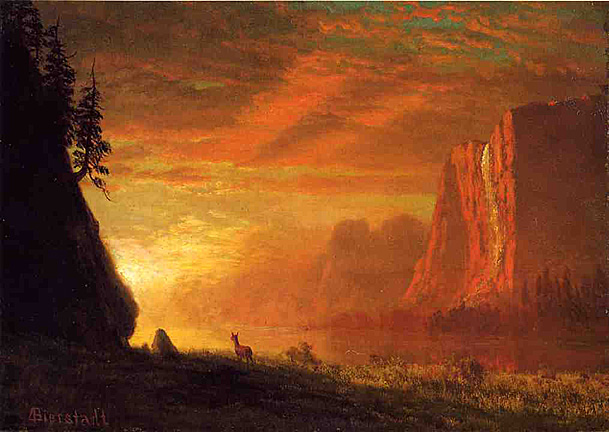

Bierstadt was always aware of the importance of the sky in his works and often brought it into active play as a source of illumination and an element of design. He seemed to delight in painting approaching storms, moonlit scenes, or billowy cloud banks. So varied are his skies and so persistently did they assert themselves in his works that it seems impossible and unnecessary to assign influences. He probably absorbed ideas and techniques from whatever sources were available to him throughout his career, including paintings or reproductions of paintings by Andreas Achenbach and Turner as well as the writings of John Ruskin, especially the lengthy section on clouds in the first volume of his Modern Painters, the first American edition of which was published in 1847. The study reproduced here, which is among Bierstadt's more detailed sky scenes, indicates the seriousness with which he studied light sources and cloud formations.

Comments by Matthew Biagell

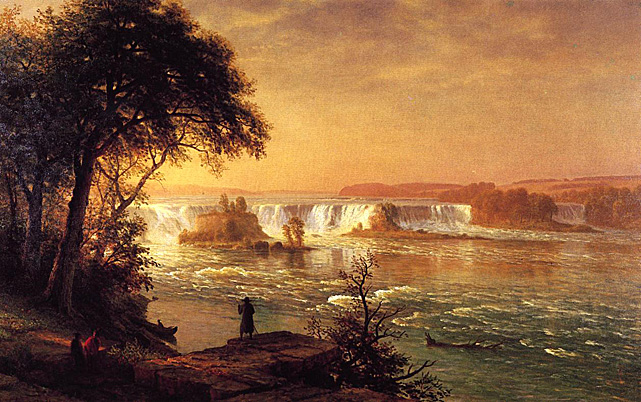

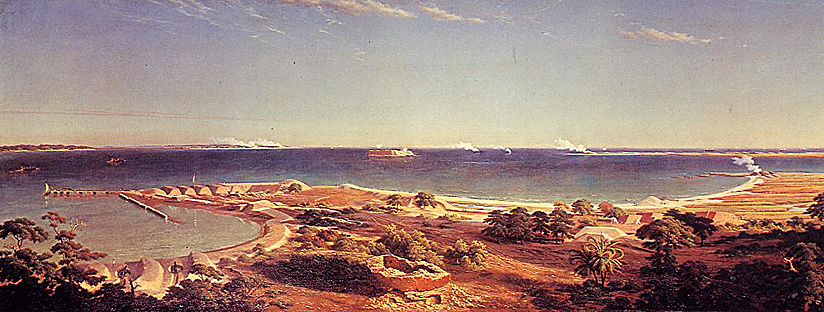

In October 1861, Bierstadt and Emanuel Leutze, whom he had befriended in Diisseldorf, received a five-day pass from General Winfield Scott to visit Union troops near the Potomac River. (At about the same time, Bierstadt's brothers, Charles and Edward, were in the same area obtaining stereographs and photographs.) As a result of this trip, the artist painted Guerrilla Warfare (Union Sharpshooters Firing on Confederates) (1862). His interest in war scenes thus aroused, Bierstadt painted The Bombardment, with the aid of subsequent newspaper accounts, since he was not in Charleston on April 12, 1861, when the thirty-four-hour attack began. It is a shockingly quiet and serene painting, despite the puffs of smoke registering from the Confederate batteries. The view is taken from a point abruptly above the coastal plain, well out of hearing of the guns. Looking down at rather than over the scene, the viewer is some distance from the encircled fort.

The Bombardment is one of Bierstadt's earliest and most insistent panoramic views. The horizon line cuts the painting in half, and the sand spits and piers emphasize its lateral sprawl. The clarity of focus allies this work to Gosnold at Cuttyhunk , although the focus is somewhat obfuscated by Bierstadt's habits of allowing textures to thicken in the painting of trees and preventing the horizon line from growing translucent. It is as if scenes set on the Atlantic coast challenged his ability to create an ambiance as transparent as possible--he probably tried to capture the light of Long Island or the New England shore for The Bombardment. This is also one of Bierstadt's least structured works, the wrecked bunker in the foreground and Fort Sumter itself providing a needed vertical axis around which the arcs of shoreline sweep. The painting is profoundly topographical and secular in mood, although it is tempting to add transcendent meaning--the loveliness of the American earth and the clarity and purity of its air and spirit remaining despite the fratricidal conflict. It may have served as a model for another descriptive panorama completed later in the decade, Jasper Cropsey's Narrows fiom Staten Island (1868).

Comments by Matthew Biagell

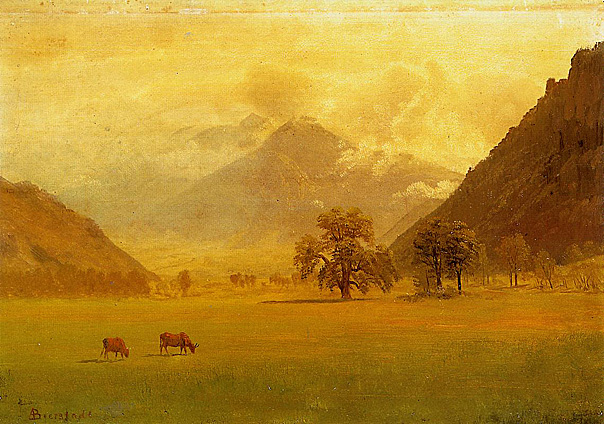

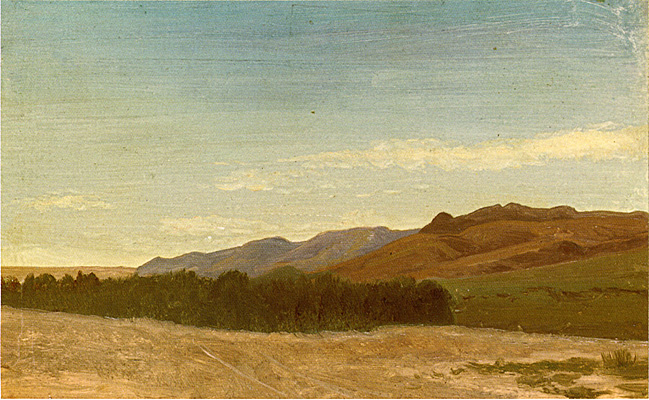

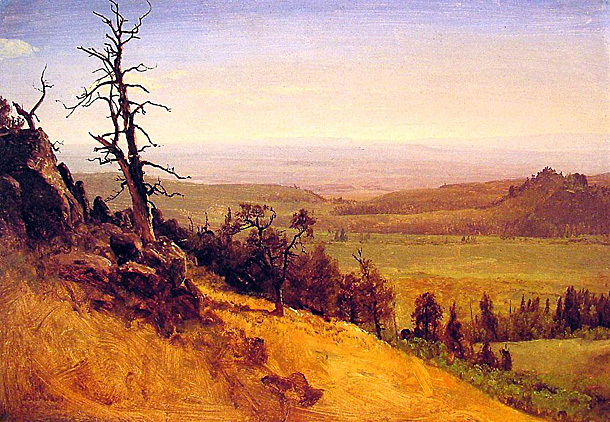

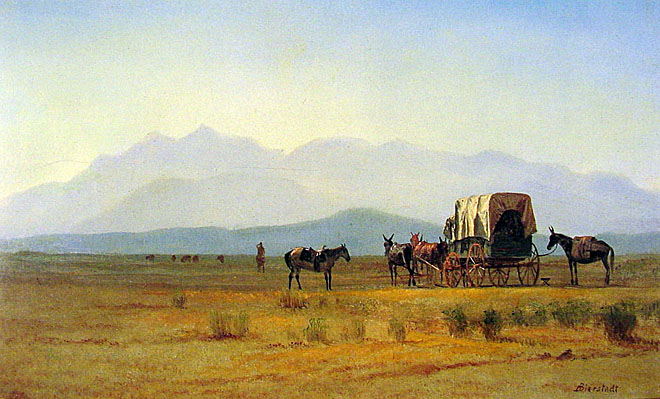

Although it is a small sketch, this work should be recognized as one of the talismanic paintings of the West. It probably records the shocking spatial disorientation triggered by seeing the endless plains and mountain ranges of the West for the first time. The wagon, the horses, and the rider are suspended in space somewhere in the open-ended plains.

Except for the continuous mountains, there are no markers by which to measure anything--no wagon tracks, hoof prints, bushes, compositional diagonals, or zigzags. The travelers move through a land without leaving a trace and are unable to measure easily the miles they have traversed. There is no possibility of determining the yardage to the grazing animals except by means of atmospheric color; proximity and distance are based on clarity of contour and color alone. Ironically, this, too, is disorienting, since one can see both more and farther in the clear air of wilderness than in the polluted air of towns and cities.

For Bierstadt, the plains were probably impossible to organize into compositional units, a factor that might explain his preference for mountain-valley themes. A generation ago, this type of landscape might have been termed "alienated," since the artist refused to organize and control it. Today we are more interested in process and mechanistic explanations and might call it a "nonstructured" or "nonspatialized" space. This kind of open composition was used later, in the late 1860s and after, in western paintings by Worthington Whittredge and John Kensett; Whittredge traveled west in 1866 and 1870, and Kensett in about 1856-57, 1868, and 1870.

Comments by Matthew Biagell

The Eastern edge of the Rockies rises impressively above the Interior Plains of central North America, including the Front Range which runs from northern New Mexico to northern Colorado, the Wind River Range and Big Horn Mountains of Wyoming, the Crazy Mountains and the Rocky Mountain Front of Montana, and the Clark Range of Alberta, along with a series of ranges in Canada called the Continental Ranges. Mount Robson in British Columbia, at 12,972 feet is the highest peak in the Canadian Rockies.

The western edge of the Rockies, such as the Wasatch Range near Salt Lake City, Utah divides the Great Basin from other mountains further to the west. The Rockies do not extend into the Yukon or Alaska, or into central British Columbia. The Rocky Mountain System within the United States is a United States physiographic region.

Pikes Peak is a mountain in the Front Range of the Rocky Mountains, 10 miles west of Colorado Springs, Colorado, in El Paso County. It is named for Zebulon Pike, an explorer who led an expedition to the southern Colorado area in 1806. At 14,115 feet, it is one of Colorado's 54 fourteeners. An upper portion of Pikes Peak is a federally designated National Historic Landmark.

The first non-natives to sight Pikes Peak were the members of the Pike expedition, led by Zebulon Pike. After a failed attempt to climb to the top in November 1806, Pike wrote in his journal:

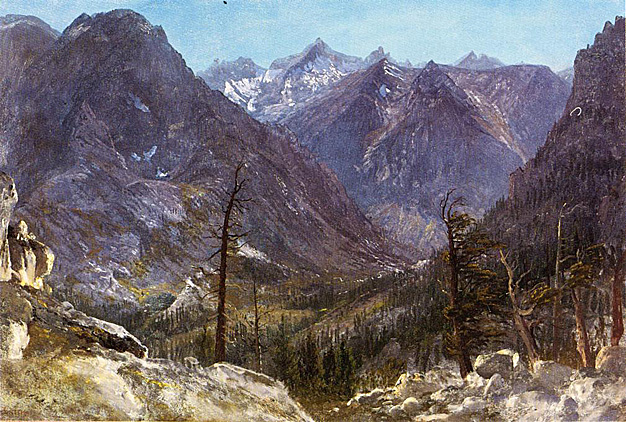

Once thought to be lost, A Storm, the masterpiece of Bierstadt's early career, was acquired by the Brooklyn Museum in 1976. Although the space-box format is used, the composition is quite unusual. Generally, Bierstadt balanced his large paintings by setting a central valley or body of water between flanking units of equal strength. But in A Storm, the mountains to the right obviously tower over those on the left, and in place of the standard valley floor and rising mountains, he created a complex sequence of elevations by adding an intermediate level in the foreground. To control the contrasts between solid mountains and open spaces, and between near and far distances, Bierstadt imposed a severe two-dimensional system of patterns that can be traced by following the connecting contours of objects, regardless of their position in depth. For instance, the left edges of the distant mountain in the center are visually continued along the edges of the clump of trees in the center foreground.

Landscape features and plant life are carefully studied in a manner quite different from the earlier The Rocky Mountains. Bierstadt added highlights in several colors to the large masses and varied the color scheme of the mountains much more subtly and intricately than before. But he also succumbed to his penchant for elaborating fantastic cloud formations hovering over the distant mountains, their rococo flourishes not always cohering visually with the generally descriptive style of painting. Nor do these clouds necessarily allow space to appear continuous from the foreground to infinity as in, for example, View of Donner Lake, California.

Bierstadt preferred keeping episodic elements to a minimum, but, consonant with the extravagant nature of A Storm, the results of an Indian hunt can be seen, horses are being chased, and an Indian encampment fills part of the valley. Never again would he paint such a complex and crowded work. A Storm is an attempt to show all at once the incredible beauty of the mountains; the vast western spaces; the phenomenal cloud formations; the variety of trees, bushes, and flowers; and a hint of the life-styles of the original inhabitants. The painting is truly a grand-scale celebration of the American West.

Comments by Matthew Biagell

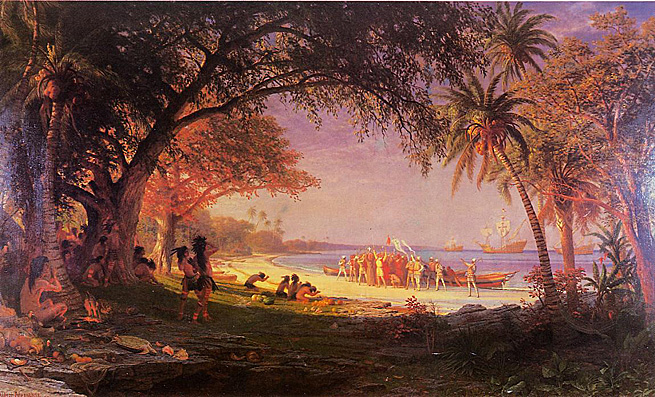

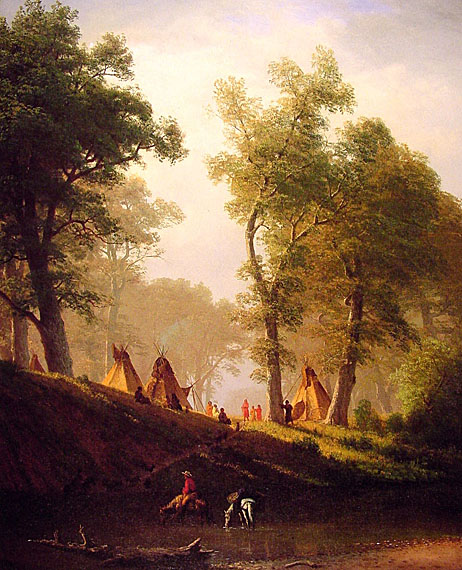

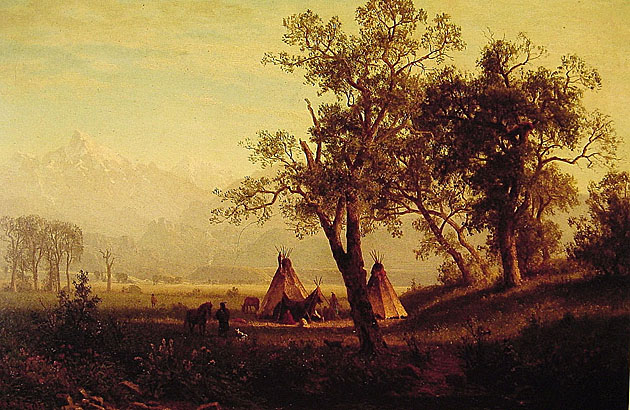

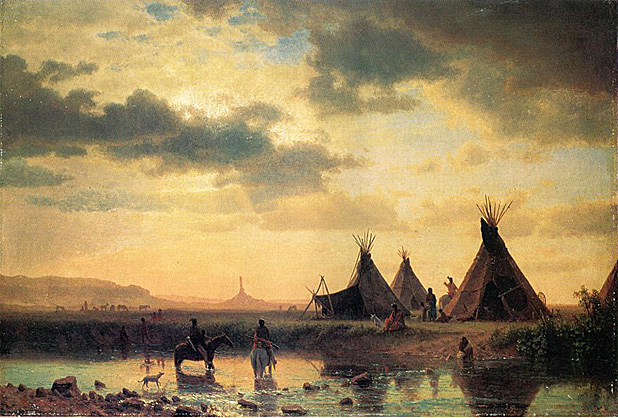

Although Bierstadt made probing studies of individual Indians during his travels in the West, he generalized their appearances and activities in his paintings. He placed them, as he placed European peasants in earlier works, in the middle distance so that we witness their presence in a landscape setting rather than focus on their movements. Indian Encampment, then, is the western equivalent of his European genre-ized landscapes and reveals Bierstadt's consistent attitude toward subject matter regardless of its locale. Here, between framing trees (a device he infrequently used), Indians are engaged in seemingly unrelated activities.

At the left, a figure points with a stick. Women in front of the tepee are playing with a dog and perhaps, since dogs were an Indian delicacy, are cooking one inside. To the right, a woman with a papoose follows a man on horseback. The painting, bathed in a golden glow, suggests nostalgia for a previous age when Native Americans were thought to have lived harmoniously with nature. Here they are not wily, wicked, or predatory, but are engaged instead in peaceful domestic industry.

Works such as this are obviously part of the broad western European tradition of Arcadian scenes, but in its American version the tradition assumes a particular complexity and ambivalence. Indian Encampment reveals the nobility of the Indians before their contact with Europeans and subsequent debasement. In time they would disappear, and for many, their disappearance was more important than their existence. Paintings displaying this attitude were both pseudo historical as well as fantasy-ridden in their reconstruction of Indian life. They undoubtedly provided the public with the images it wanted to see, especially during the years Indians were systematically being driven from their lands. Revealingly, many paintings of Indians of this period lack the documentary qualities of works by George Catlin (1796-1872) and Karl Bodmer (1809-93), painted when there was still ample space for everybody in the American West. These paintings also lack the viciousness of later works by Frederic Remington (1861-1909), done when Indians were being squeezed between new settlers and corporations exploring the mineral wealth of the land.

Comments by Matthew Biagell

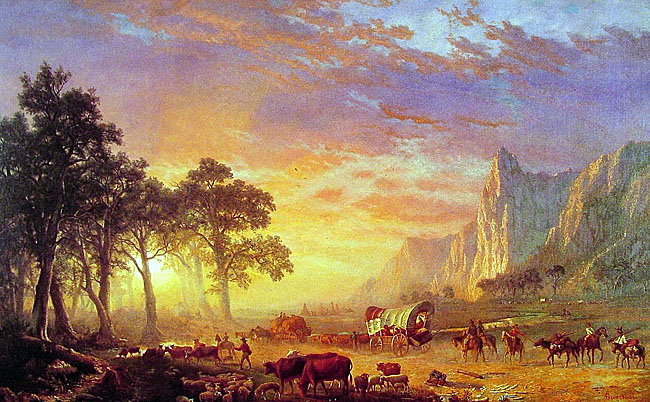

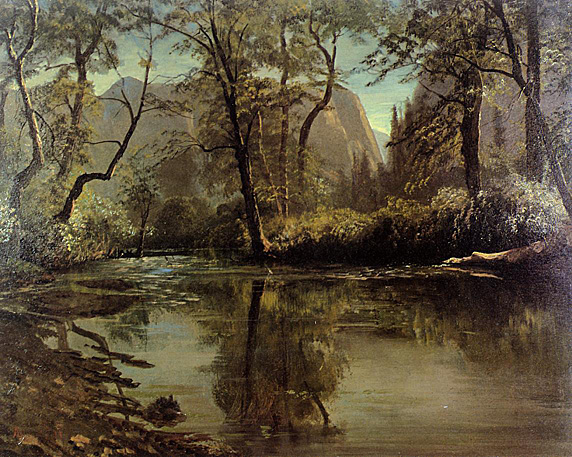

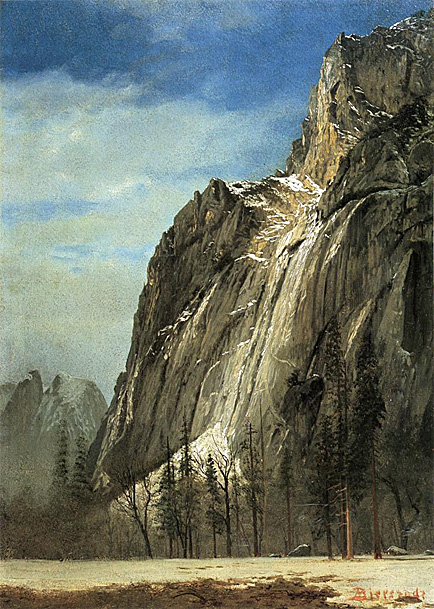

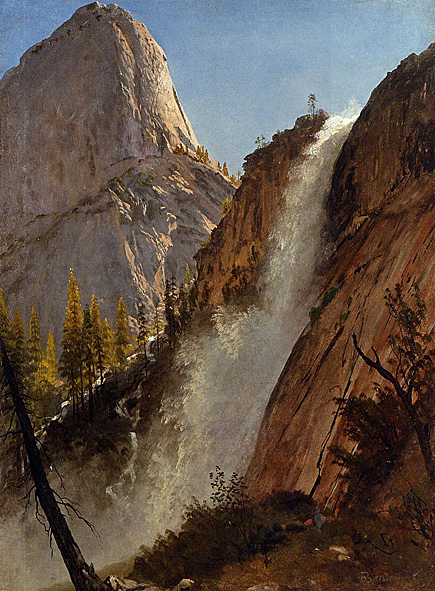

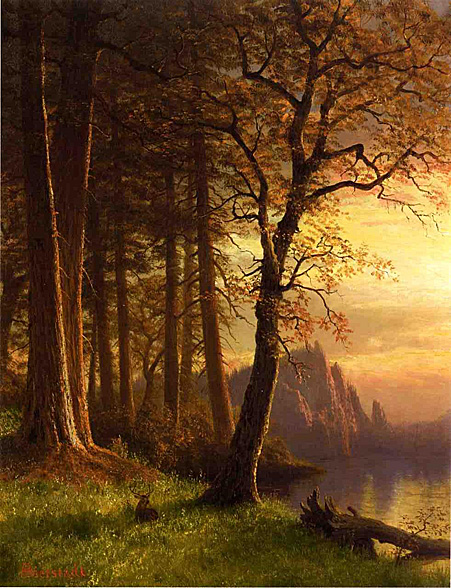

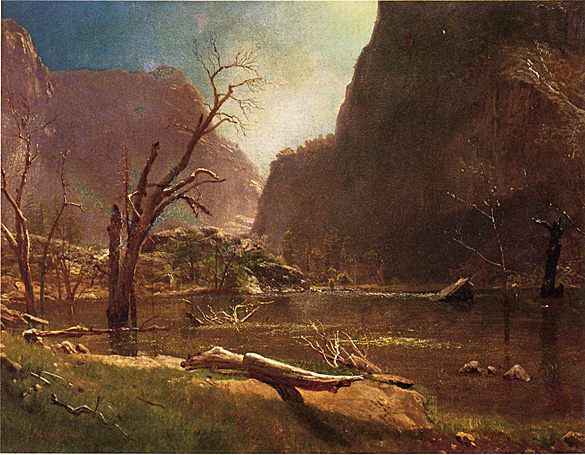

Bierstadt first visited the Yosemite Valley in 1863 and subsequently painted it in all seasons, climates, moods, and hours as well as in its several aspects--as a wondrous marvel and a pleasant park bordered by precipitously rising mountains, as an intimate place for a picnic or rest, and as a snow-covered desolate wilderness. He painted it in small and monumental scale, on small and enormous canvases. He was so charmed by the site that one historian has even conjectured that Bierstadt planned his second western trip only after seeing Carleton Watkins's photographs of the valley in Goupil's Gallery in New York City in 1862.

This work shows Yosemite as a parklike enclosure, even though the valley floor was still wilderness. Despite threatening skies, the serenity of the view describes Yosemite's Edenic qualities. (Bierstadt usually preferred wildemess to garden scenes.) In fact, this is one of the artist's most harmoniously composed Yosemite scenes. The balances between forms and the continuities of movement (for example, from cliff profiles to tree trunks to reflections in the water) are studied more carefully than usual and point to the influence of Watkins. Even though Watkins, as a photographer, had less control over his subjects than a painter would have, he had the breathtaking ability to position his camera so that linkages between units and patterns of surface movement appear obvious and inevitable. He also attempted to restrict the number of forms and details in a scene, a characteristic that has a sympathetic echo in this work.

Comments by Matthew Biagell

Paiute and Sierra Miwok peoples lived in the area for decades before the first white explorations into the region. A band of Native Americans called the Ahwahneechee lived in Yosemite Valley when the first non-indigenous people entered it.

The California Gold Rush in the mid-19th century dramatically increased white travel in the area. United States Army Major Jim Savage led the Mariposa Battalion into the west end of Yosemite Valley in 1851 while in pursuit of around 200 Ahwahneechees led by Chief Tenaya as part of the Mariposa Wars. Accounts from this battalion were the first confirmed cases of Caucasians entering the valley. Attached to Savage's unit was Dr. Lafayette Bunnell, the company physician, who later wrote about his awestruck impressions of the valley in The Discovery of the Yosemite. Bunnell is credited with naming the valley from his interviews with Chief Tenaya. Bunnell wrote that Chief Tenaya was the founder of the Pai-Ute Colony of Ah-wah-nee. The Miwoks (and most white settlers) considered the Ahwahneechee to be especially violent due to their frequent territorial disputes, and the Miwok word "yohhe'meti" literally means "they are killers". Correspondence and articles written by members of the battalion helped to popularize the valley and surrounding area.

Tenaya and the rest of the Ahwahneechee were eventually captured and their village burned; they were removed to a reservation near Fresno, California. Some were later allowed to return to the valley, but got in trouble after attacking a group of eight gold miners in the spring of 1852. The band fled and took refuge with the nearby Mono tribe; but after stealing some horses from their hosts, the Ahwahneechees were tracked down and killed by the Monos. A reconstructed "Indian Village of Ahwahnee" is now located behind the Yosemite Museum, which is next to the Yosemite Valley Visitor Center.

Entrepreneur James Mason Hutchings, artist Thomas Ayres and two others ventured into the area in 1855, becoming the valley's first tourists. Hutchings wrote articles and books about this and later excursions in the area, and Ayres' sketches became the first accurate drawings of many prominent features. Photographer Charles Leander Weed took the first photographs of the Valley's features in 1859. Later photographers included Ansel Adams.

Wawona was an Indian encampment in what is now the southwestern part of the park. Settler Galen Clark discovered the Mariposa Grove of Giant Sequoia in Wawona in 1857. Simple lodgings were built, as were roads to the area. In 1879, the Wawona Hotel was built to serve tourists visiting the Grove. As tourism increased, so did the number of trails and hotels.

Concerned by the effects of commercial interests, prominent citizens including Galen Clark and Senator John Conness advocated for protection of the area. A park bill passed both houses of the U.S. Congress, and was signed by President Abraham Lincoln on June 30, 1864, creating the Yosemite Grant. This is the first instance of park land being set aside specifically for preservation and public use by action of the U.S. federal government, and set a precedent for the 1872 creation of Yellowstone as the first national park. Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove were ceded to California as a state park, and a board of commissioners was proclaimed two years later.

Galen Clark was appointed by the commission as the Grant's first guardian, but neither Clark nor the commissioners had the authority to evict homesteaders (which included Hutchings). The issue was not settled until 1875 when the homesteader land holdings were invalidated. Clark and the reigning commissioners were ousted in 1880, and Hutchings became the new park guardian.

Access to the park by tourists improved in the early years of the park, and conditions in the Valley were made more hospitable. Tourism significantly increased after the First Transcontinental Railroad was completed in 1869, but the long horseback ride to reach the area was a deterrent. Three stagecoach roads were built in the mid-1870s to provide better access for the growing number of visitors to the Valley.

Scottish-born naturalist John Muir wrote articles popularizing the area and increasing scientific interest in it. Muir was one of the first to theorize that the major landforms in Yosemite were created by large alpine glaciers, bucking established scientists such as Josiah Whitney, who regarded Muir as an amateur. Muir wrote scientific papers on the area's biology.

Overgrazing of meadows (especially by sheep), logging of Giant Sequoia, and other damage caused Muir to become an advocate for further protection. Muir convinced prominent guests of the importance of putting the area under federal protection; one such guest was Robert Underwood Johnson, editor of Century Magazine. Muir and Johnson lobbied Congress for the Act that created Yosemite National Park on October 1, 1890. The State of California, however, retained control of the Valley and Grove. Muir also helped persuade local officials to virtually eliminate grazing from the Yosemite High Country.

The newly created national park came under the jurisdiction of the United States Army's Fourth Cavalry Regiment on May 19, 1891, which set up camp in Wawona. By the late 1890s, sheep grazing was no longer a problem, and the Army made many other improvements. The Cavalry could not intervene to help the worsening condition of the Valley or Grove.

Muir and his Sierra Club continued to lobby the government and influential people for the creation of a unified Yosemite National Park. In May 1903, President Theodore Roosevelt camped with Muir near Glacier Point for three days. On that trip, Muir convinced Roosevelt to take control of the Valley and the Grove away from California and return it to the federal government. In 1906, Roosevelt signed a bill that did precisely that.

The National Park Service was formed in 1916, and Yosemite was transferred to that agency's jurisdiction. Tuolumne Meadows Lodge, Tioga Pass Road, and campgrounds at Tenaya and Merced lakes were completed in 1916. Automobiles started to enter the park in ever-increasing numbers following the construction of all-weather highways to the park. The Yosemite Museum was founded in 1926 through the efforts of Ansel Franklin Hall.

In 1903, a dam in the northern portion of the park was proposed. Located in the Hetch Hetchy Valley, its purpose was to provide water and hydroelectric power to San Francisco. Preservationists like Muir and his Sierra Club opposed the project, while conservationists like Gifford Pinchot supported it. In 1913, the U.S. Congress authorized the O'Shaughnessy Dam through passage of the Raker Act. More recently, preservationists persuaded Congress to designate 677,600 acres, or about 89% of the park, as the Yosemite Wilderness - a highly protected wilderness area.

Although Bierstadt had traveled to the West several times in the 1860s and 1870s, he did not visit the Yellowstone area until 1880. Of the varied scenery he saw there, he was most attracted to the geysers and Yellowstone Falls. His finished paintings tended to be medium-sized, indicating that he was not as attracted to the area as Thomas Moran. Or perhaps he chose not to compete with Moran, whose famous Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone was completed in 1872. Bierstadt's Lower Yellowstone Falls was probably based on his own sketches and the photographs of William Henry Jackson. In his version, Bierstadt provided the falls with greater vertical lift by steepening the diagonals of the canyon and accenting the cliff at the upper right. He also raised the horizon line nearly to the top of the painting, a device used by American painters at least by the 1850s. In the foreground Bierstadt placed a few trees, a device Hans Gude had used in Dusseldorf, to provide a sense of distance between the viewer and the falls.

Except for these few alterations, including the emphasized crossed diagonals in the center and the profile of the lower rocks echoing the contour of the lip of the falls, the painting is an unaffected exercise in realistic depiction. A larger painting, undoubtedly based on this study, is another matter. There, violent contrasts of dark and light throw the foreground trees into theatrical, as opposed to merely dramatic, relief. The cliffs assume a candy-coated quality. Additional and exaggerated amounts of foam lather up from the base of the falls, and the mountain in the distance detracts from the central compositional climax of the falls themselves. Clearly, the smaller study appeals more to our contemporary taste, and it probably appealed to the informed taste of 1881 as well.

Comments by Matthew Biagell

Lake Louise is named after the Princess Louise Caroline Alberta (1848-1939), the fourth daughter of Queen Victoria, and the wife of the Marques of Lorne, who was the Governor General of Canada from 1878 to 1883.

The unique emerald color of the water comes from rock flour carried into the lake by melt-water from the glaciers that overlook the lake (Lefroy glacier). The lake has a surface of (0.3 sq mi), and is drained through the 3 km long Louise Creek into the Bow River.

In the foothills, the water from the river is impounded at Pine Flat Dam. In the Central Valley, the river flows south of Fresno, California, where its water is diverted for agriculture. The river channel feeds into the Tulare Lake basin, which is currently dry.

The Kings River was named by Lieutenant Gabriel Moraga on one of the first expeditions by the Spanish to the Central Valley of California in 1806. The Kings River was originally named Rio de los Santos Reyes (River of the Holy Kings).

On the valley floor the Kings River is responsible for certain groundwater recharge. There is evidence in the Hanford area that depths to groundwater are increasing, indicating concern for safe yields of this basin.

For Bierstadt's Eyes Alone

by Mary Terence McKay

Nineteenth-century America epitomized the age of Romanticism. "The great cultural project of the...century was to explore the relations between man and nature.... No previous age had brought such passionate scrutiny...or projected [onto nature] so many human aspirations."

The century had begun on the pure note of transcendental creed. "The age was ocular," mused Ralph Waldo Emerson, but "the health of the eye seems to demand a horizon. We are never so tired as long as we can see far enough." Thus by mid-century, America was fueled by the energy of exploration and empire, an energy which faced westward with prophetic dreams of a Passage to India voiced by the great orators of the day, Thomas Hart Benton and William Gilpin, and intoned in verse by Walt Whitman himself.

The age thus embodied both the real and the ideal, and all of America was caught up in the complexity of these two conflicting paradigms. On the one hand, America regarded herself as a bucolic and pastoral Eden, an Arcadia in which nature was thought to be "the fingerprint of God's creation [and]...a direct clue to his intentions." On the other, she enacted a policy of imperialism dignified by the phrase "Manifest Destiny" implying the inevitable supremacy of America as conqueror of "the western spaces" by divine sanction!

Increasingly, as America strove to reach her potential -- embracing the industrialization which hurtled her toward the age of technology -- the American wilderness moved west and became the West which soon embodied not only America's future but finally American identity itself. Every youth knew Fenimore Cooper's "Leather-Stocking Tales" and dreamed of one day exploring the West like Cooper's frontier scout, Natty Bumppo.

In this conflicted and highly energized world, young Albert Bierstadt, too, dreamed of the West. (Family history purported that at age twelve, he even wrote a school composition on "The Rocky Mountains." The sixth child of Henry and Christina Bierstadt, Albert was born in 1830 in Solingen, Prussia, a small town close to Düsseldorf. The family immigrated to America when he was two, settling in New Bedford, Massachusetts where his father, a cooper by profession, could find work.

As a young man Bierstadt "worked the bench" at Shaw's Frame Factory, a "Looking Glass and Picture Frame Manufacturer." In 1852, he contracted with artist George Harvey "to tour the latter's 'Dissolving Views of American Scenery,'" painted on glass and projected to fifteen by seventeen feet in a theater setting by means of a device known as a Drummond Light. The admission fee was twenty-five cents, and the hall where these images were projected was "nightly thronged with admiring spectators," a phenomenon that made a lasting impression on the enterprising Bierstadt.

He used the proceeds from this endeavor to travel in 1853 to Düsseldorf, the site of an international artists' colony and academy which was much admired by American painters of the day for its technical strengths -- "good composition, accurate drawing and faithful and elaborate finish." Upon his arrival there, Bierstadt began to study informally with Worthington Whittredge and Emmanuel Leutze, two prominent American painters in residence at the time. Whittredge, in fact, took Bierstadt under his wing:

After working in my studio for a few months, he fitted up a paint box, stool and umbrella which he put with a few pieces of clothing into a large knapsack, and shouldering it one cold April morning, he started out to try his luck among the Westphalian peasants.... He remained away without a word until late autumn when he returned loaded down with innumerable studies of all sorts.... It was a remarkable summer's work for anybody to do, and for one who had little or no instruction, it was simply marvelous. He set to work in my studio immediately on large canvas composing and putting together parts of studies he had made and worked with an industry which left no daylight to go to waste.

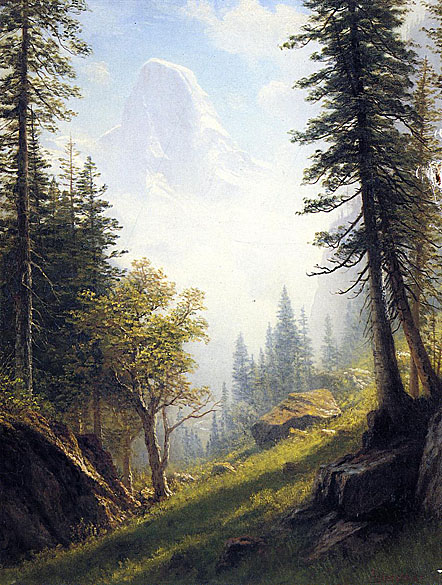

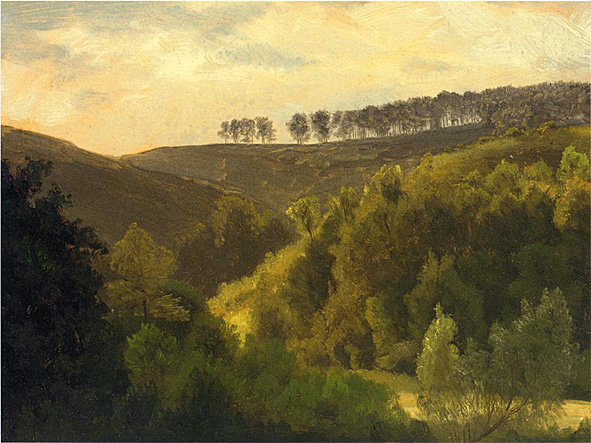

Remaining in Europe for three-and-a-half years, Bierstadt first sketched the surrounding German countryside, then traveled for fifteen months with Whittredge, Sanford Gifford and other artists through Switzerland, over the Bernese and Italian Alps and into Italy, sketching all the while and sending paintings home to New Bedford as quickly as he could complete them.

Returning to the United States in September 1857, Bierstadt had acquired the reputation of a serious painter. He spent the next year-and-a-half working his many European sketches into paintings, but he became restless and soon began to look about for new material.

The perfect: opportunity arose in April 1859, when Colonel Frederick West Lander, chief engineer of the central division of the Overland Trail, was ready to improve a "cut-off' route which he had forged the previous year. On the strength of his reputation first as a painter, and secondly as a photographer, Albert Bierstadt impressed Lander sufficiently to wrangle from him an invitation to join the expedition bound for the Rocky Mountains.

Bierstadt was aware of the intense curiosity Americans had for their distant frontier, a curiosity aroused by writers such as Richard Henry Dana, Francis Parkman, John C. Fremont and others. The anticipation had been that the Rockies might prove a match for the European Alps, an important consideration "for they offered the last real hope that mountain grandeur on a European scale might be found within American borders." It was, after all, the awe-inspiring sublimity of the Alps that poets and writers had extolled for generations, and it became a matter of national pride for Americans to find something comparable at home.

While George Catlin, Karl Bodmer, Alfred Jacob Miller and John Mix Stanley had all preceded Bierstadt out West, none had primed his paintings with the experience of sketching the Alps that Bierstadt had garnered in Europe. From the base of the Rockies, he wrote a letter to the Crayon, New York's primary art magazine of the 1850s:

The mountains are very fine, as seen from the plains; they resemble very much the Bernese Alps, one of the finest ranges of mountains in Europe, if not in the world....Their jagged summits, covered with snow and mingling with the clouds, present a scene which every lover of landscape would gaze upon in unqualified delight....We see many spots in the scenery that remind us of our New Hampshire and Catskill hills, but when we look up and measure the mighty perpendicular cliffs that rise hundreds of feet aloft, all capped with snow, we then realize that we are among a different class of mountains. In September 1859, Bierstadt returned to New Bedford with "a full complement of sketches, photographs and Indian artifacts" which he used to compose what would later be termed his "Great Pictures." The most important painting to derive from the Lander expedition, The Rocky Mountains, Lander's Peak, 1863, represented a scene in the Wind River Range of Nebraska Territory complete with two exquisite waterfalls tumbling into a lake (which doubled as a reflecting pool) and an encampment of Shoshone Indians -- all "projected" onto a 6' x 10' canvas -- a scale recalling George Harvey's views enlarged with the aid of the Drummond Light. Further playing upon national sentiment, Bierstadt named the mountain which dominated the scene after Lander, recently martyred in the Civil War.

A critic for the Chicago Times seized upon the imaginative powers of the artist calling the painting "wondrously full of invention. Even James Jackson Jarves, who would become Bierstadt's most formidable critic, commented that "in the quality of American light, clear, transparent, and sharp in outlines, he is unsurpassed."

The Rocky Mountains typified many of the western paintings which would follow. In essence, "Bierstadt invented the Western American landscape," suggests Bierstadt scholar Nancy Anderson, "by skillfully joining passages of carefully observed and meticulously rendered detail with freely configured composition that met national needs." The paintings which resulted from this first expedition proved enormously successful with the American public, so much so that within a few short years one reviewer commented in jest what was in fact partly true that "Bierstadt had already copyrighted all the principal mountains."

A second trip in 1863 to the West Coast to document Yosemite and any other alpine peaks which might present themselves was even more artistically and financially rewarding. To facilitate this success, Bierstadt honed his skills at self-promotion to a fine edge, presenting the "Great Pictures" which resulted as if they were on stage:

The light is most carefully excluded from that part of the room occupied by the spectators, both by day and night. The walls about the end of the room where the picture is are carefully and gracefully draped with dark stuff, which absorbs most of the light that does not fall directly upon the picture. As the painting represents a view of an extensive valley from a considerable eminence, two galleries have been constructed from which a down view can be obtained, thus heightening the illusion. In the night time this deceptive effect is stronger than can be obtained from a day view, and is not unlike that of a set in a theatre.

Bierstadt's marketing technique, however, invited controversy, as contemporary opinion dictated that an artist should be "a priestly figure whose life as a quasi-religious vocation [was] free of worldly goals." Asher B. Durand, the dean of the Hudson River School, clarified its position: "We cannot serve God and Mammon. It is better to make shoes or dig potatoes than seek the pursuit of Art for the sake of gain.... This is one of the principal causes operating to the degradation of Art, perverting it to the servility of a mere trade." James Jackson Jarves was more to the point: "Within proper limits, the zest of gain is healthful; but if pushed to excess, it will reduce art to the level of trade."

While the nineteenth century remembered Bierstadt both adoringly and critically for his monumental and idealized paintings of what would come to be called "the American sublime," it is ironic that twentieth-century art historians were first attracted to his "fresh and brilliant" plein air sketches which they found "surprisingly modern" and which they saw as precursors to the gestural work of their own mid-century artists. In 1963, the Florence Lewison Gallery in New York mounted the first of three exhibitions devoted to these sketches which contributed to a re-discovery and re-evaluation of the artist's entire oeuvre.

Bierstadt was hardly the first to excel at painting in the open air. The plein air tradition in America had begun with the earliest landscape painters, the patriarchs of the Hudson River School, who were greatly influenced by the Claudian mode and the extraordinary plein air sketches of Claude Lorraine himself (1600-1682).

"Every herb and flower of the field has its specific, distinction, and perfect beauty, ...its peculiar habitation, expression and function," intoned the English art critic, John Ruskin. "The highest art is that which seizes this specific character, which assigns to it its proper position in the landscape.... Every class of rock, every kind of earth, every form of cloud, must be studied with equal industry, and rendered with equal precision." The landscape painter should study atmospheric changes "daily and hourly," added Durand, because "the degrees of clearness and density, scarcely two successive days the same -- local conditions of temperature -- dryness and moisture -- and many other causes, render anything like specific direction impracticable."

In the 1850s, the plein air sketch began to gain favor, especially among devotees of Durand, though the problem of sketch versus finished painting was even more complex in America than in Europe. Delacroix's musings on the subject suggest that even he suffered from an art audience which preferred "finish" over "vague suggestion":

Here we come back, as always, to the question of which I have spoken before: the finished work compared with the sketch -- the great edifice when only the large guiding lines are visible and before the finishing and coordinating of the various parts has given it a more settled appearance and therefore limited the effect on our imagination, a faculty that enjoys vagueness, expands freely and embraces vast objects at the slightest hint.

From the time of her earliest limners, and because of them, America had demonstrated a preference for "linear boundedness," "linear distinctness." Thus, while the idea behind the sketch -- apprehending the specificity of nature -- was applauded, it was rarely ever felt that the sketch might stand on its own merit.

As the nineteenth-century American artist had, for the most part, no patronage for his sketch, one can appreciate Bierstadt's sketches as intimate and intensely private documents which were a significant part of his artistic process. Journeying with him for a moment back into the West which he loved, we glimpse something of his acuity at sketching through William Byers, then editor of the Rocky Mountain News.

Byers had offered to take Bierstadt into the Rockies to show him a particularly stunning view for what would become his most ambitious Rocky Mountain painting, Storm in the Rocky Mountains, Mt. Rosalie, completed in 1866. The excursion had begun on a day of dismal and stormy weather, but when Bierstadt finally "caught sight of the chosen view, he was transformed":

He said nothing, but his face was a picture of intense life and excitement. Taking in the view for the moment, he slid off his mule, glanced quickly to see where the hack was that carried his paint outfit, walked sideways to it and began fumbling at the lash-ropes, all the time keeping his eyes on the scene up the valley.... As he went to work he...[remarked], "I must get a study in colors; it will take me fifteen minutes!" He said nothing more. It was indeed a notable, a wonderful view. In addition to the natural topographic features of the scene, storm-clouds were sweeping across...from north-west to south-east.... Eddies of wind from the great chasm following up the face of the cliff were again caught in the air-current at its crest and drove the broken clouds in rolling masses through the storm-drift.... Soft hailstones were falling [and]... rays of sunlight were breaking through the broken, ragged clouds and lighting up in moving streaks the falling storm.... Bierstadt worked as though inspired. Nothing was said by either of us. At length the sketch was finished to his satisfaction. The glorious scene was fading as he packed up his traps. He asked: "There, was I more than fifteen minutes?" I answered: "Yes, you were at work forty-five minutes by the watch!"

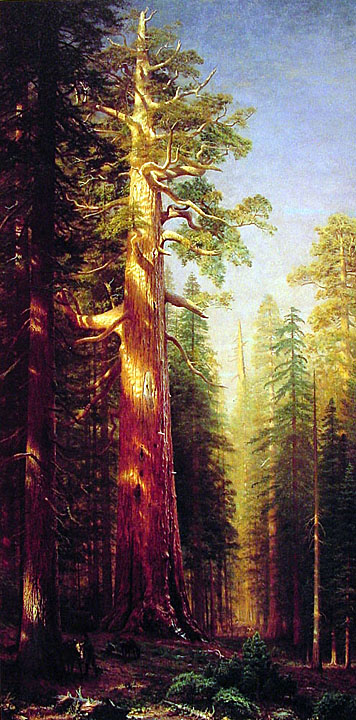

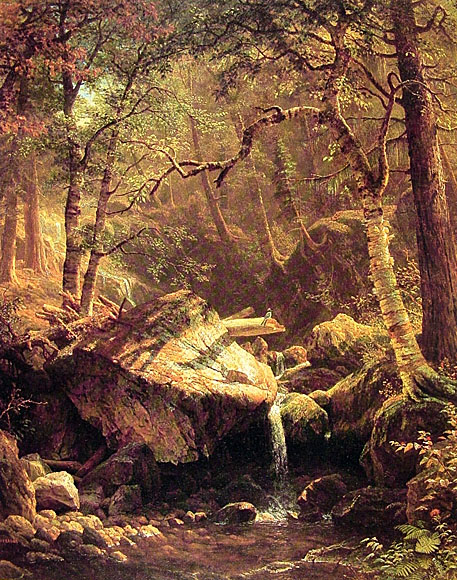

In Among the Sierra Nevada Mountains, California, (1868) one becomes aware of the extraordinary power of Bierstadt's plein air sketch transposed into the larger panoramic scene. While the viewer might need to see this large painting from a distance of thirty or so feet, Bierstadt "lavished" an inordinate amount of time on the exquisite detail "of rocks, foliage and shoreline.... For the especially observant viewer, the artist offered a technical tour de force -- a fish visible beneath the surface of the crystalline mountain water and otherwise unnoticeable from the farther distance!"

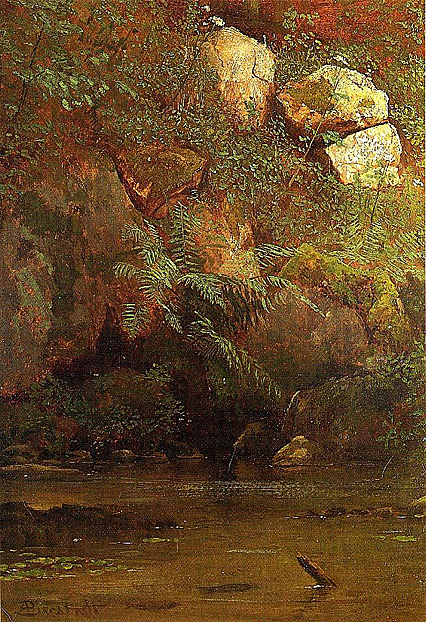

The plein air sketch -- meant for Bierstadt's eyes alone -- became the impetus for his resulting paintings and an integral part of them. In the sketches, he could explore subtle shades of color under varying conditions of light; or record mist, fog, storm and sunshine -- dawn, twilight, sunset and a multiplicity of variations in between -- nuances which, when interjected into his paintings, imbued them with a powerful, temporal quality.

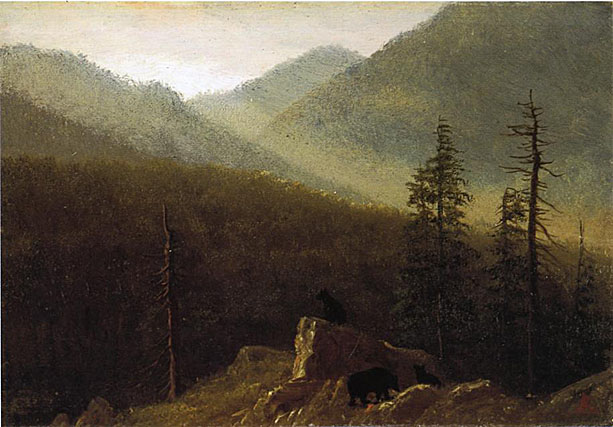

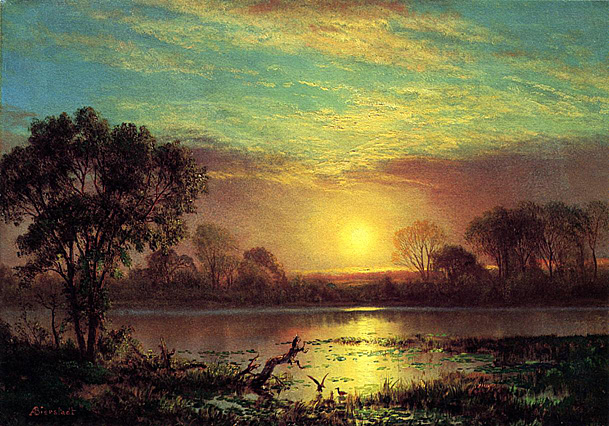

That peculiar opalescent pink (found at the heart of a conch shell) that dawn brings to San Francisco Coast is one example; scudding clouds lifting off a flawless sheen of water as a storm clears -- his preoccupation in After the Storm -- is another. Bierstadt also learned to convey the humid heat and mid-August haze at the height of a New England summer. White Mountains - New Hampshire and Forest Scene were both executed during the summer of 1874 when he and his brothers advanced on the White Mountains to sketch and photograph them.

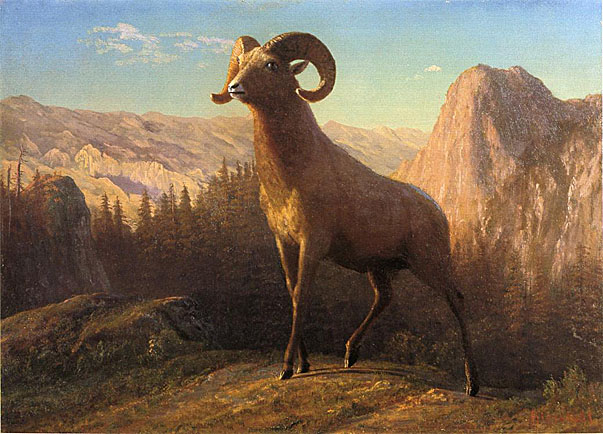

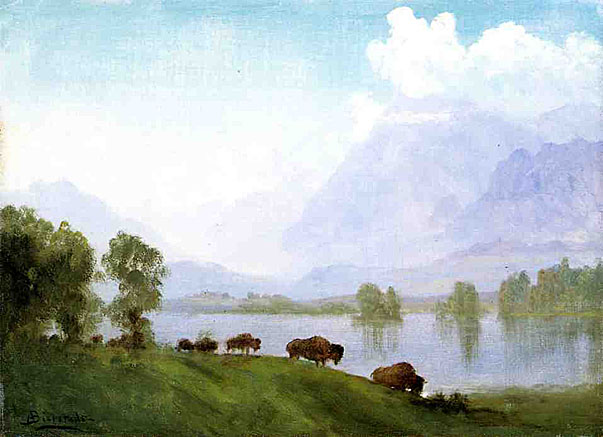

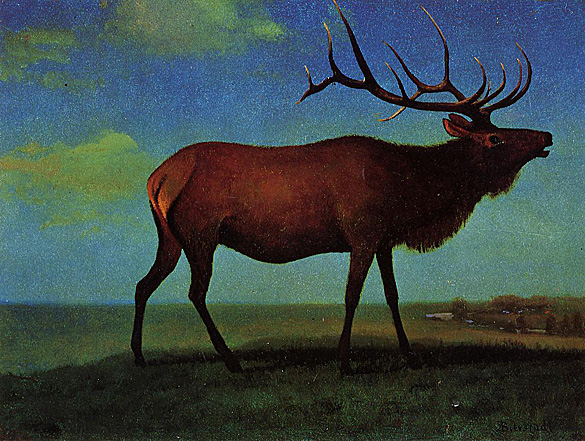

If "vanishing" came to convey the essence of the West, another Bierstadt drama -- sometimes stated, often implied -- was evoked by the tension created when the artist juxtaposed the temporal fragility of man or animal against the timeless indifference of Nature. A prominent member of Teddy Roosevelt's Boone and Crockett (hunting) Club in New York, Bierstadt, with his keen powers of observation, noted the wildlife he encountered everywhere in the wilderness including the wild horses which graze upon and are almost subsumed by the rich grass at the side of a mountain river (Owen's Valley) and the frail bravado of two Rocky Mountain Sheep (ca. 1870-1880) silhouetted against the sharp precipices of the treacherous terrain which surrounds them.

The waterfall was another fascinating character in the Bierstadt drama, one that he used repeatedly in his depictions of the Rocky Mountains and the Sierra Nevadas. Waterfall, probably executed in upper New York state between 1860 and 1870, shows Bierstadt's interest in the action of falling water, the force with which it planes across the crumbling mill and hurtles into the pool below.

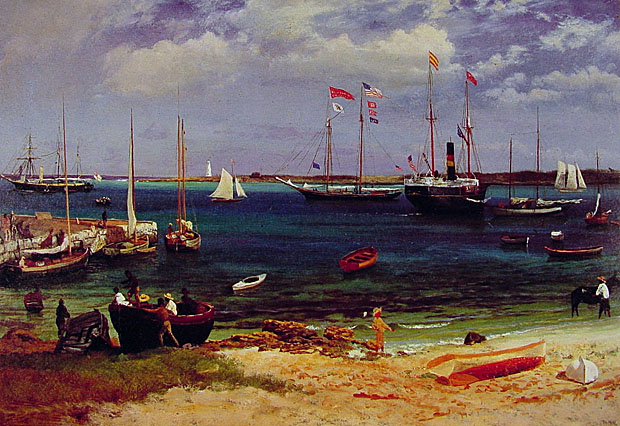

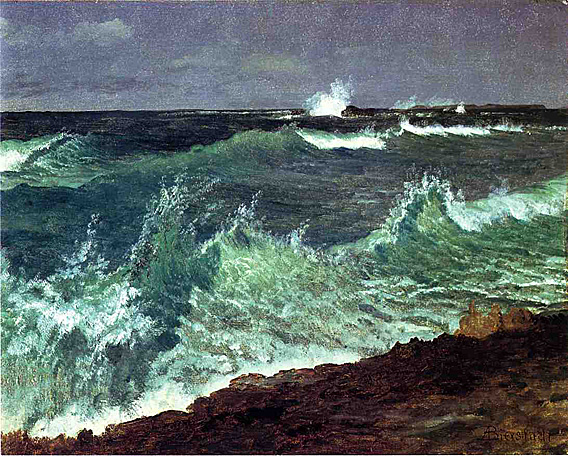

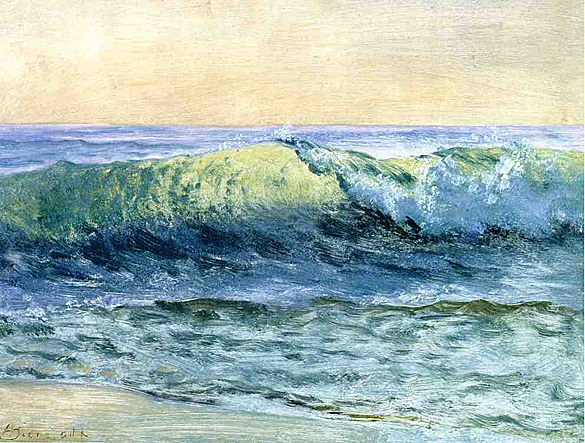

Wave (1878) captures both the structure and the tourmaline-blue translucence of a Caribbean breaker off the island of New Providence one split second before it crashes upon the shore. Inspired by Bierstadt's earliest visits to the Caribbean, where his wife convalesced in the winters of 1877 to 1893, this oil sketch preceded his most important marine painting, The Shore of the Turquoise Sea (1878).

On a three-month trip to Yellowstone in July 1881, Bierstadt's quick brush and sharp vision even captured the geothermal sterility, the barren otherworldliness, of Yellowstone National Park where every sixty-six minutes, the geyser Old Faithful erupts 300 feet into the air under the watchful gaze of a "red-eyed" crater (Old Faithful -- Yellowstone).

Much like the West itself, the Wagnerian themes of Bierstadt's exuberant paintings helped to shape America's self image. But the plein air oil sketches provided the "real" material that made Albert Bierstadt's "ideal" landscapes both credible and incredible. Though they were used as building blocks to construct his heroic works, one can readily conclude that they stand freely on their own merit -- spare, fresh, and unforgettable.

Source: Art Renewal Center

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.