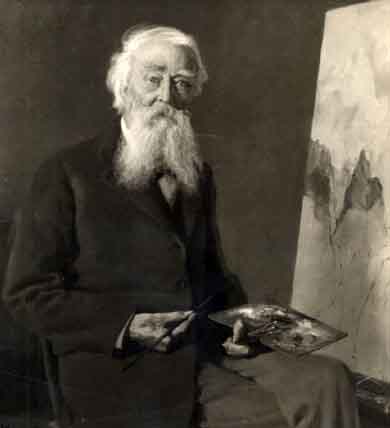

Painter, Engraver, Etcher, Illustrator,

Lithographer, Printmaker & Photographer

1837 - 1926

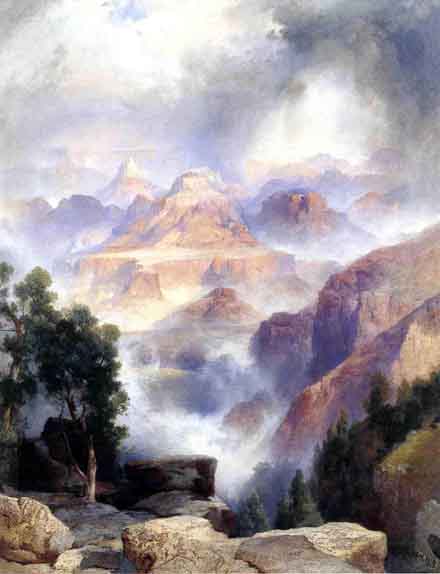

"We had reached the Canon on the second level or edge of the great gulf. Above and around us rose a wall of 2000 feet and below us a vast chasm 2500 feet in perpendicular depth and 1/2 a mile wide."

"From our camp at the pocket the wall of the Grand Canyon was visible some 15 miles down the valley."

"Here are no lofty peaks seeking the sky, no mighty glaciers or rushing streams wearing away the uplifted land. Here is land, tranquil in its quiet beauty, serving not as the source of water, but as the last receiver of it. To its natural abundance we owe the spectacular plant and animal life that distinguishes this place from all others in our country"

"During the night I was awakened by a wolf crunching the bones of a rabbit we had eaten. He was not more than 12 feet from where we were lying, and it being moonlight, I saw him clearly."

"The color of the Great Canon itself is red, a light Indian Red, and the material sandstone and red marble and is in terraces all the way down."

Thomas Moran was born on 12 February 1837 in Bolton, England, the son of a hand-loom weaver whose life had been irrevocably changed by the advent of the Industrial Revolution. Displaced by labor-saving machinery, Thomas Moran Sr. immigrated to America. He settled his family in Kensington, Pennsylvania (near Philadelphia), in 1844.

By the time young Thomas completed grammar school and entered an apprenticeship with a local engraving firm, his older brother Edward had embarked upon a career as an artist. Harboring the same ambition, Thomas terminated his apprenticeship prematurely and began working with Edward in his studio.

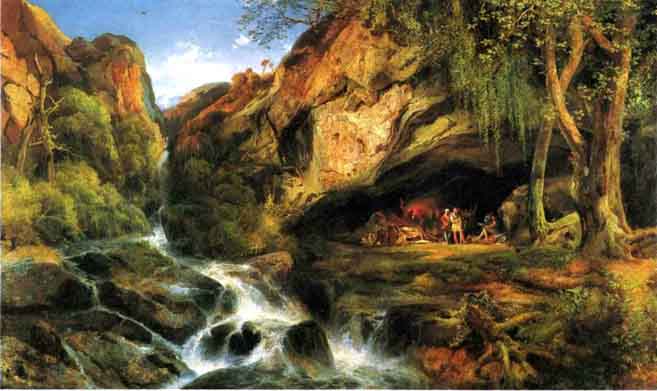

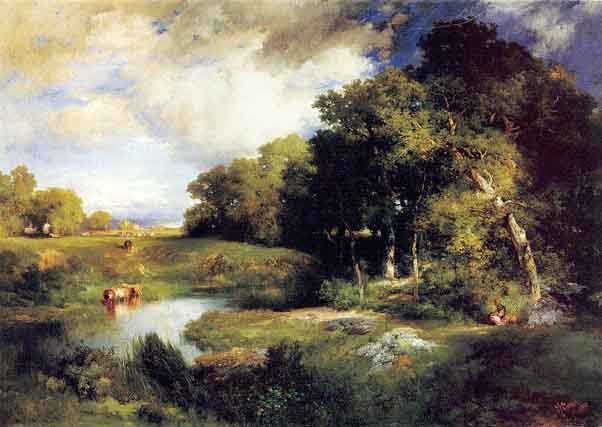

Encouraged by his brother and informally instructed by several Philadelphia painters, Moran began to exhibit accomplished paintings during the early 1860's. His love of literature resulted in a number of "fantasy" pictures, including Salvator Rosa and the Brigands. During the 1860's Thomas and Edward (often joined by their brother John, a professional photographer) undertook numerous sketching trips in the forests surrounding Philadelphia. The studio paintings that resulted from these excursions, including The Autumnal Woods, reflect the influence of the American Pre-Raphaelites whose fascination with the natural world generated extraordinarily detailed landscape studies.

_1865.jpg)

_1862.jpg)

Of even greater importance to young Moran was the work of England's foremost landscape painter, J.M.W. Turner, which Moran knew primarily through prints and engravings. Eager to see Turner's art, Thomas and Edward traveled to England in 1862.

In London they made copies of paintings by Turner and later followed his sketching route along the coast of England, noting the "liberties" he had taken with the landscape. In 1866 Thomas returned to Europe to study paintings by European masters and to exhibit his major early work, Children of the Mountain, in the Exposition Universelle in Paris in the spring of 1867. At times mistaken for a western landscape, the picture was in fact an artistic invention. In 1867 Moran had not yet crossed the Mississippi River or seen the Rocky Mountains. Four years later, he used this painting as collateral to help finance the western trip that changed the course of his career.

Thomas Moran saw Yellowstone for the first time in the summer of 1871. A few months earlier he had been asked to rework sketches submitted as illustrations for an article on Yellowstone published in Scribner's Magazine. Titled "The Wonders of Yellowstone", this article was the first extensive description published in the East of the landscape long rumored to be "the place where hell bubbled up."

Moran quickly recognized Yellowstone as a new and exciting "subject for pictures," and within weeks he had arranged to join the first government-sponsored survey of Yellowstone, led by geologist Ferdinand V. Hayden, who had been instructed to map and measure the region. Traveling across the country aboard the newly completed transcontinental railroad, Thomas Moran joined Hayden in Virginia City, Montana.

Although he was so thin that he required a pillow on his saddle, Moran quickly adapted to the rigors of the trail. In a journal entry dated 11 July he wrote:

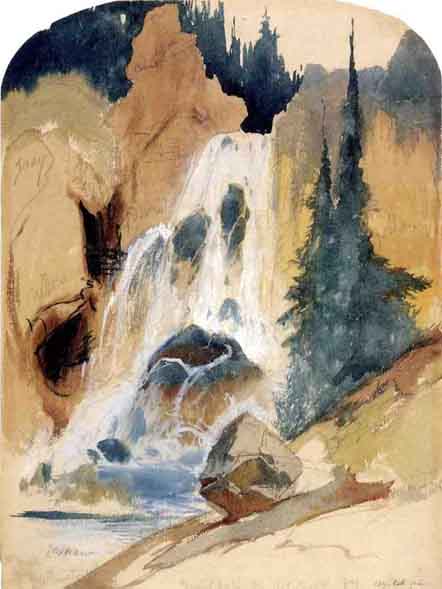

During the next two months he produced dozens of watercolor studies that would serve as the basis for numerous paintings. The field sketches completed during this trip were the first color images of Yellowstone ever seen in the East.

Working with William Henry Jackson, the expedition photographer, Moran completed numerous watercolor sketches of Yellowstone's hot springs, mud pots, geysers, and waterfalls. From his loosely sketched and broadly painted field studies, Moran composed highly structured, exquisitely painted watercolors in his studio.

Occasionally Moran created larger watercolor images for exhibition, such as this view of the hot springs on Gardiner's River in Yellowstone. In a letter to Hayden dated 28 January 1873, he wrote: "I shall send down the large water color drawings of the Springs next week to Barlow on Penna Av. (Washington, D.C.) for exhibition for a week or two. It will attract attention I think."

Soon after Moran returned east, Ferdinand Hayden and others (including executives of the Northern Pacific Railroad), began promoting the idea that Yellowstone should be protected and preserved as a national park. Because no member of Congress had seen Yellowstone, Hayden and his colleagues brought Moran's watercolors, along with the photographs taken by William Henry Jackson on the 1871 expedition, to Capitol Hill. Their images were later reported to have played a decisive role in the debate that led to the establishment of Yellowstone as the first national park in March 1872.

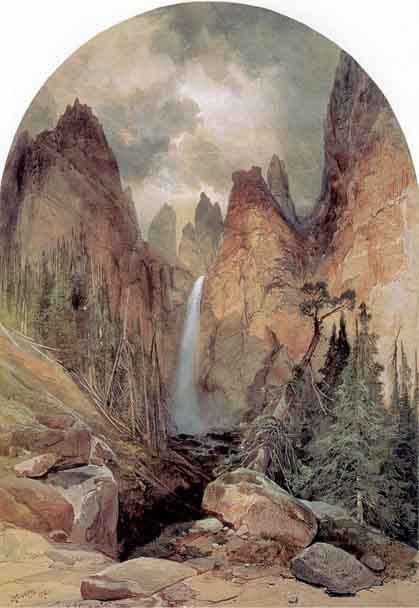

Shortly thereafter Congress appropriated $10,000 for the purchase of Moran's Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, the painting that launched his career. Measuring seven by twelve feet, the panoramic view of Yellowstone Canyon featured the distant falls and a striking display of the canyon's golden walls. In the foreground Moran placed a group of figures that includes F.V. Hayden and the artist himself.

Two years later Congress purchased a second, equally grand landscape by Moran, Chasm of the Colorado, painted following the artist's 1873 trip with John Wesley Powell to the Grand Canyon of the Colorado River.

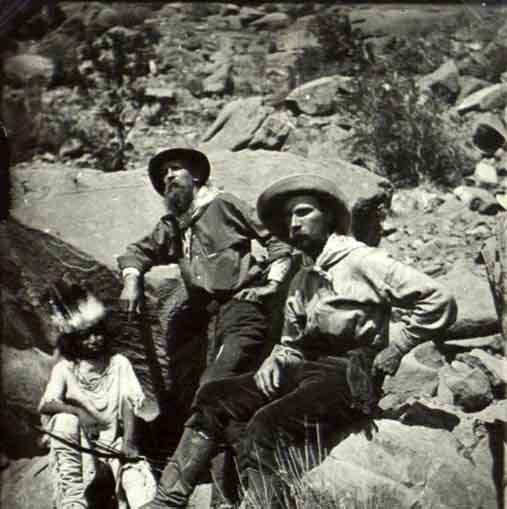

In the summer of 1873 Moran headed west to join John Wesley Powell on a trip to the Grand Canyon. Four years earlier Powell had captured the nation's attention when he led a small group of men in custom-crafted boats through the whitewater of the Colorado River. Already planning a pendant for Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, Moran accepted Powell's invitation to join him the following summer. Accompanying the party was Justin E. Colburn, a correspondent, who, during the trip, sent letters east for publication in the New York Times. Vivid, candid, and insightful, Colburn's letters offer a clear view of a forbidding landscape and a firsthand account of the often difficult journey he and Moran made with Powell to the Grand Canyon. Moran wrote his wife Mary a humorous and revealing account of his adventures on 13 August 1873.

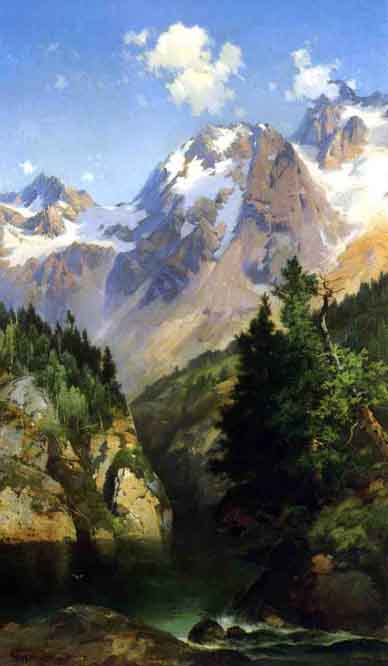

In 1875 Moran completed the third of his great western landscapes, Mountain of the Holy Cross, a view of a famous Colorado peak with a cross of snow on its side. In an attempt to capture the "true impression" of the scene rather than a topographical view, Moran freely invented the foreground waterfall in his painting. Forthright about his approach, Moran declared, "I place no value upon literal transcripts from Nature. My general scope is not realistic; all my tendencies are toward idealization....Topography in art is valueless."

Although he had hoped to exhibit all three paintings in the Philadelphia exposition celebrating the nation's centennial in 1876, Moran's plans were thwarted when Congress refused to lend the two pictures it had purchased for the Capitol. He did exhibit Mountain of the Holy Cross in the Philadelphia Exposition. Intended to form a grand triptych, the three paintings are seen together for the first time in this exhibition. As a visual reflection of the American debate that set westward expansion and "progress" in opposition to the preservation of "sacred landscapes," the paintings occupy a central position in American cultural history.

By 1876 Moran had established himself as one of the major landscape painters of his day, rivaling in stature even Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902), who had introduced the panoramic western landscape a decade earlier. Unlike Bierstadt, who painted almost exclusively in oil, Moran created some of the most dazzling watercolors of the late nineteenth century. Often begun in the field, Moran's watercolor sketches frequently served as the basis for multiple studio variations. Among the most compelling is the Yellowstone watercolor Great Springs of the Firehole River. Beneath broad strokes of transparent color, the pencil sketch and notes Moran used to define the landscape are still visible.

In the later studio version of the same image, Lower Geyser Basin, Moran translated his field notations, including the word "stumps," into literal elements.

In 1876 a variation on the same image was published by Louis Prang in a portfolio of chromolithographs (color reproductions made from specially prepared stones). This remarkable printing effort helped spread news of Yellowstone and Moran to a wide audience. Prang's portfolio was heralded as one of the most spectacular publications of the age.

When Moran journeyed west for the first time in 1871, his sights were set on Yellowstone, but the trail to the land of geysers passed through another remarkable landscape--one that would become as closely associated with Moran as Yellowstone--the Green River Valley of Wyoming. Once the site of the fur trappers' annual rendezvous, Green River had more recently served as the western terminus for the Union Pacific Railroad. By the time Moran arrived, the burgeoning town on the banks of the river could boast a schoolhouse, church, hotel, and brewery. Exercising a degree of artistic license worthy of Turner, Moran erased all signs of commercial development, concentrating instead on the multicolored buttes rising above the river. In paintings that contained more fiction than fact, Moran replaced railroad tracks with Indian caravans. Skillfully combining the spectacular Landscape of Green River with figures that reflected an increasingly nostalgic view of Indian life, Moran produced a series of paintings that were so popular that he continued to sell variations on the theme well into the twentieth century.

While he was enjoying critical and commercial success with his paintings of the West, Moran also found inspiration in other subjects. He was an artist of broad interests whose body of work included images based on historical and literary works, marine subjects, pastoral views, and, surprisingly, urban and industrial scenes.

In the 1880's his long-time enthusiasm for marine painting grew stronger following his move to East Hampton, Long Island. From the cottage and large studio he built on Main Street in 1884, the artist had easy access to the beach, where he could study the sea in all its moods. Moran's numerous marine paintings include several shipwrecks-- disasters all too common along the eastern shore of Long Island.

During the same decade Moran began to paint pastoral views of Long Island that soon rivaled his western landscapes in popularity.

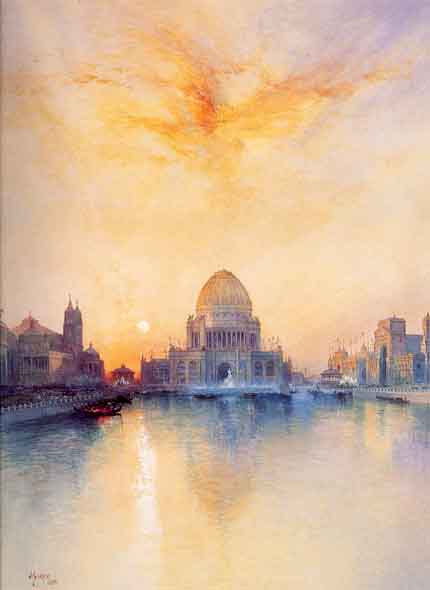

Equally notable are Moran's industrial scenes of the early 1880's. One of the most impressive is Lower Manhattan from Communipaw, New Jersey. Looking across the Hudson River from the sugar refineries on the Jersey waterfront, Moran offered a shimmering view of the Manhattan skyline. Moran was extraordinarily adept at capturing the reflective interplay of sunlight, water, and a city's façade.

An indefatigable traveler, Moran and his family returned to Bolton, England, early in 1882, where the native son was celebrated in local newspapers. Ever the businessman, he mounted a sizable exhibition--including 22 oil paintings, 100 watercolors, a series of 25 illustrations from Longfellow's Hiawatha, a series of etchings and proof engravings, and the complete set of Prang chromolithographs of Yellowstone. Sales were apparently brisk, since a Boston newspaper later reported, "His paintings and etchings have been warmly commended by critics, and he has sold nearly all of them to eager purchasers." The true highlight of the European trip came later, after a side trip to Scotland, when Moran and his wife visited London and met John Ruskin, the eminent English critic, who purchased some of Moran's work. Winning approval from Turner's champion must have been a true high point of Moran's professional career.

Shortly after returning from England, Moran embarked on a trip to Cuba and Mexico. Tireless in his pursuit of new subject matter, Moran completed a large number of sketches, including several extraordinary views of the Trojes Mine in central Mexico.

On yet another journey to Europe, Moran completed sketches of the icebergs that figure prominently in Spectres from the North. Studies executed while in Italy also resulted in numerous Venetian paintings that explored the reflective interplay of water and light.

Moran saw Venice for the first time in 1886, but he was well acquainted with the city before he arrived, for Venice had been one of Turner's favorite subjects. Having seen the city first through Turner's eyes, Moran traveled to familiar sites to secure the watercolor sketches he would need to produce studio paintings when he returned home. In these Venetian pictures he used a compositional technique quite similar to that he had employed with his Green River paintings. Moran often "anchored" these paintings with recognizable architecture and then freely invented foreground elements, in place of the Indian caravans that frequently made their way across the foregrounds of the Green River pictures. Gondolas and fishing vessels filled with brightly costumed figures often float in the foreground of the Venetian works. In the United States, views of Venice were enormously popular near the end of the nineteenth century, in part because the city seemed a poetic, Old World refuge from an industrialized America that was pushing full speed into a new age.

In addition to his studio paintings, Moran often accepted commissions for book and magazine illustrations that required travel. In 1877 he journeyed to Florida to prepare illustrations for an article in Scribner's. Shortly thereafter he began work on an ambitious history painting, Ponce de Leon in Florida. Engaged in a spirited rivalry for government patronage with fellow artist Albert Bierstadt, Moran had hoped to sell Ponce de Leon to Congress. Bierstadt won the battle, less on merit, perhaps, than on the compromise premise that Congress had already purchased two paintings by Moran and only one by Bierstadt.

Setting aside the disappointment he must have felt at the outcome of this competition, Moran quickly made plans to return west. Accompanied by his brother Peter, Moran clearly was on a mission to collect new material for pictures. Surviving sketches indicate that Thomas and Peter traveled to Donner Pass in the Sierra Nevada range and sketched near Lake Tahoe and Salt Lake City before turning north toward Fort Hall and the Snake River Country of Idaho. It was during this trip that Moran sketched the Teton Mountains for the first time--a subject he returned to several times in the 1890's. Years earlier, F.V. Hayden had named one of the Teton peaks "Mount Moran" in his honor.

In the spring of 1892 Moran journeyed to Flagstaff, Arizona, where he was joined by his longtime friend William Henry Jackson. Together they returned to the Grand Canyon and later Yellowstone--the landscapes that had made both men famous twenty years earlier.

It was on this 1892 trip that Moran created one of his finest field sketches. Titled In the Lava Beds, the small watercolor juxtaposes the massive lava walls of the Grand Canyon with delicate wisps of smoke rising from the campfire built by Moran and his companions. In the foreground, isolated and spare, is Jackson's camera. Mounted on spindly legs that appear to have been painted with single strokes from a tiny brush, the camera seems aptly emblematic of the fragility of the human enterprise in a landscape as overpowering as that of the Grand Canyon.

Increasingly, during the 1890's, the landscape of Long Island became one of Moran's most frequent subjects. The artist's contemporaries, intrigued by the pastoral qualities of paintings like June, East Hampton, noted that the famous painter of American wilderness was equally adept producing quiet scenes on a much smaller scale.

Fully aware of changes in the market, Moran told a Denver reporter in June 1892, "I prefer to paint western scenes, but the Eastern people don't appreciate the grand scenery of the Rockies. They are not familiar with mountain effects and it is much easier to sell a picture of a Long Island swamp than the grandest picture of Colorado."

Well into the twentieth century, Moran continued producing works that reflected his travels in the West. Among these were a group of paintings showing the pueblos and cliff dwellings of the ancient people who had once lived in the American southwest.

Using sketches and photographs as memory aids, Moran gathered information that he would use--sometimes years later--to produce his studio paintings.

In the summer of 1900, a few months after the death of his beloved wife Mary, Moran returned to Yellowstone, accompanied by his youngest daughter Ruth. During the next two decades Thomas and Ruth frequently spent the winter months at the Grand Canyon. In exchange for rail passes and hotel accommodations, Moran produced paintings of the canyon that were used as promotional tools in hotels, offices, and railroad cars. Additional images were distributed on calendars in guidebooks and brochures, even on stationery.

Commissioned by the Santa Fe Railroad to produce a painting of the Grand Canyon that could be used for marketing purposes, Moran entered a business relationship with the railroad that would prove one of the most sustained and profitable of his career. Eventually the artist became so closely identified with the canyon that the railroad used his picture in advertisements.

In the three decades since Moran had first visited Yellowstone, Congress had expanded the initial legislation setting aside additional "parks" including Yosemite in 1890. Inextricably linked through his paintings to numerous landscapes that eventually became national parks, Moran would one day be known as the "father" of the national park system. Yellowstone had become a tourist Mecca. The railroads, stage lines, and hotels that transported and served increasing numbers of tourists were thriving. Congressional action may have curtailed commercial excess within the park, but outside the entry gates commercial enterprise was faring very well. Moran created and marketed images which came as much from the imagination as from experience. A master at mixing fact and fiction, Moran used the technique to great advantage, producing some of the most remarkable American landscapes of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Moran's Yellowstone trip of 1900 was part of a larger journey that included stops in Utah and Idaho. It was the Idaho leg of the trip--the rail and stage expedition to Shoshone Falls on the Snake River--that resulted in Moran's last major western landscape. Unlike Yellowstone, at the turn of the century Shoshone Falls was a "fresh" subject. The large scale of the image suggests that from the outset, Moran conceived the work as a picture for a special exhibition; it is likely he hoped to exhibit the painting in the Pan-American Exposition to be held in Buffalo, New York, the following year. As early as 1866, Shoshone Falls had been called the "Niagara of the West," when a newspaper article described the cataract as "a world wonder which for savage scenery and power sublime stands unrivaled in America." Western enthusiasts were quick to point out that Shoshone Falls was approximately fifty feet higher than Niagara and that the rush of water over the lava cliffs was every bit as magnificent.

Like Chasm of the Colorado, Moran's Shoshone Falls is a grand statement about the power of water, as the turbulent Snake River plunges more than 200 feet over a serrated edge. Thunderclouds, dark and threatening, move swiftly along the horizon, and the "roar" of the water is almost palpable. Ironically at the time of Moran's visit that roar was about to be significantly reduced. During the coming decades, an enormous reclamation project that tapped the Snake River as a source of irrigation water was set in motion. Shoshone Falls would never again appear as Moran painted it. When shown at the Pan-American Exposition, the painting was awarded a silver medal, but his last large western panorama remained unsold at the time of his death. Taste and the times had changed.

Blessed with good health and energy, Moran maintained a daunting travel schedule that included four more trips to Europe during the last years of his life. In 1911, just back from Europe, Moran told a reporter from the New York World, "I looked at the Alps, but they are nothing compared to the majestic grandeur of our wonderful Rockies. I have painted them all my life and I shall continue to paint them as long as I can hold a brush. I am working as hard as I ever did...."

Moran continued to paint well into the 1920's, as documented in this ten-second video of Moran in his garden (left frame)--the only existing motion picture footage of the artist, who was then in his late eighties. A contemporary article in the Kansas City Star acknowledged: "Thomas Moran is confessedly America's greatest landscape painter, as he is also the painter of America's greatest landscapes.... His has ever been the perspective of a country upon which Nature had lavished colossal splendors.... He has evinced a combination of realism and idealism that sets his work superlatively apart from the many workers in the same field."

More than many of his contemporaries realized, Moran was an imaginative painter and a skilled promoter. With a technical virtuosity inspired by artists he admired (such as Turner), Moran's subject matter extended the range of the romantic landscape from the ancient volcanic landscape of distant Idaho to the cavernous abyss of the Grand Canyon.

Moran died at the age of 89 at his home in Santa Barbara, California, on 25 August 1926. During his long and prolific career he produced some of the most remarkable landscapes of the nineteenth century and was recognized, in his old age, as the "dean of American painters."

Source: Art Renewal Center

Source: Thomas Moran

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.