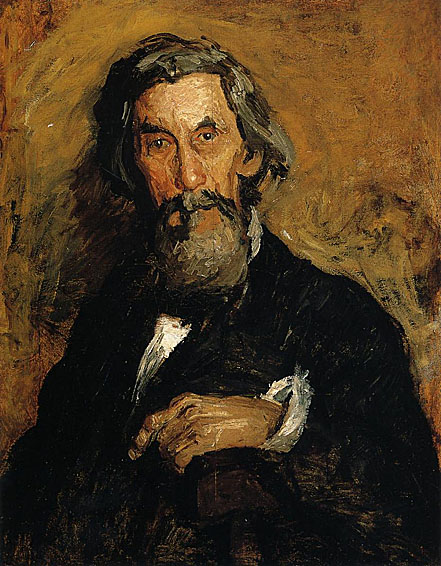

American Naturalist Painter, Sculptor, Photographer, and Teacher

1844 - 1916

Thomas Cowperthwait Eakins was a painter, photographer, sculptor, and fine arts educator. He was one of the greatest American painters of his time, an innovating teacher, and an uncompromising realist. He was also the most neglected major painter of his era in the United States.

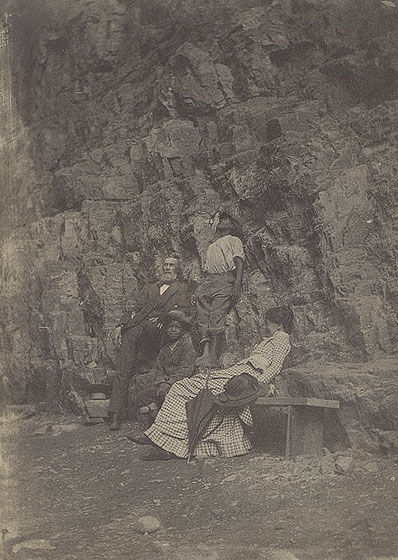

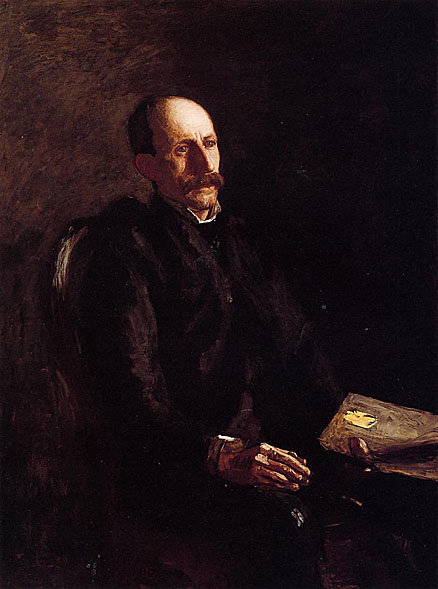

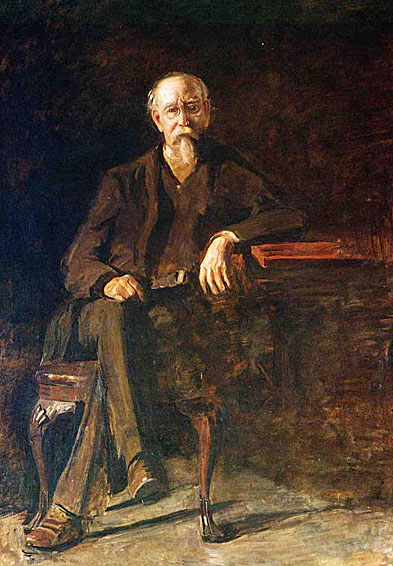

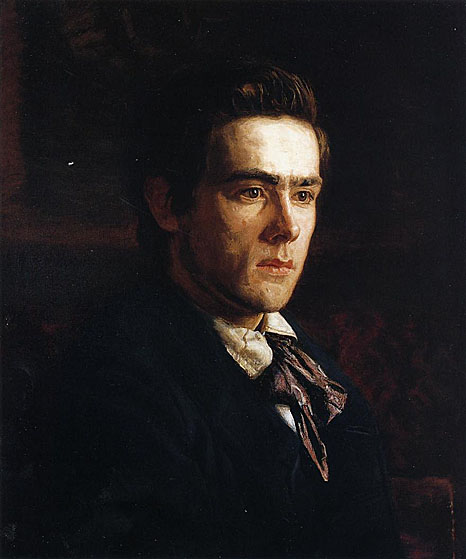

For the length of his professional career, from the early 1870's until his health began to fail some forty years later, Eakins worked exactingly from life, choosing as his subject the people of his hometown of Philadelphia. He painted several hundred portraits, usually of friends, family members, or prominent people in the arts, sciences, medicine, and clergy. Taken en masse, the portraits offer an overview of the intellectual life of Philadelphia in the late 19th and early 20th centuries; individually, they are incisive depictions of thinking persons. As well, Eakins produced a number of large paintings which brought the portrait out of the drawing room and into the offices, streets, parks, rivers, arenas, and surgical amphitheaters of his city. These active outdoor venues allowed him to paint the subject which most inspired him: the nude or lightly clad figure in motion. In the process he could model the forms of the body in full sunlight, and create images of deep space utilizing his studies in perspective.

No less important in Eakins' life was his work as a teacher. As an instructor he was a highly influential presence in American art. The difficulties which beset him as an artist seeking to paint the portrait and figure realistically were paralleled and even amplified in his career as an educator, where behavioral and sexual scandals truncated his success and damaged his reputation.

Eakins also took a keen interest in the new technologies of motion photography, a field in which he is now seen as an innovator. Misunderstood and ignored in his lifetime, his posthumous reputation places him as "the strongest, most profound realist in nineteenth-and early-twentieth-century American art".

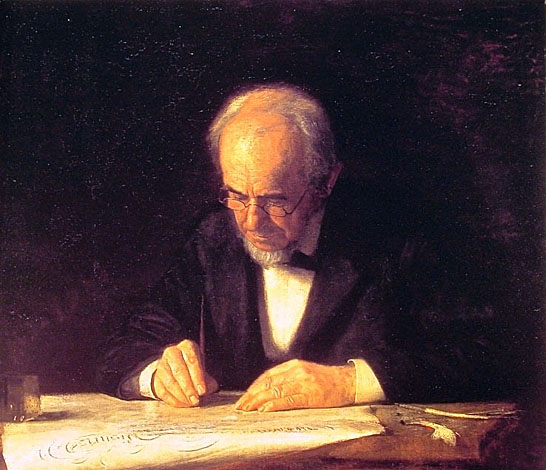

Eakins was born and lived most of his life in Philadelphia. He was the first child of Caroline Cowperthwait Eakins, a woman of English and Dutch descent, and Benjamin Eakins, a writing master and calligraphy teacher of Scots-Irish ancestry. Benjamin Eakins grew up on a farm in Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, the son of a weaver. He was successful in his chosen profession, and moved to Philadelphia in the early 1840's to raise his family. Thomas Eakins observed his father at work and by twelve demonstrated skill in precise line drawing, perspective, and the use of a grid to lay out a careful design, skills he later applied to his art.

He was an athletic child who enjoyed rowing, ice skating, swimming, wrestling, sailing, and gymnastics-activities he later painted and encouraged in his students. Eakins attended Central High School, the premier public school for applied science and arts in the city, where he excelled in mechanical drawing. He studied drawing and anatomy at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts beginning in 1861, and attended courses in anatomy and dissection at Jefferson Medical College from 1864-65. For a while, he followed his father's profession and was listed in city directories as a "writing teacher". His scientific interest in the human body led him to consider becoming a surgeon. Eakins then studied art in Europe from 1866 to 1870, notably in Paris with Jean-Léon Gérôme, being only the second American pupil of the French realist painter famous as a master of Orientalism. He also attended the atelier of Léon Bonnat, a realist painter who emphasized anatomical preciseness, a method adapted by Eakins. While studying at L'Ecole des Beaux-Arts, he seems to have taken scant interest in the new Impressionist movement, nor was he impressed by what he perceived as the classical pretensions of the French Academy. A letter home to his father in 1868 made his aesthetic clear:

Already at age 24, "Nudity and verity were linked with an unusual closeness in his mind." Yet his desire for truthfulness was more expansive, and the letters home to Philadelphia reveal a passion for realism that included, but was not limited to, the study of the figure.

A trip to Spain for six months confirmed his admiration for the realism of artists such as Diego Velazquez and Jusepe de Ribera. In Seville in 1870 he painted Carmelita Requeña, a portrait of a seven year old gypsy dancer more freely and colorfully painted than his Paris studies. That same year he attempted his first large oil painting, A Street Scene in Seville, wherein he first dealt with the complications of a scene observed outside the studio. Although he failed to matriculate and showed no works in the salons, Eakins succeeded in absorbing the techniques and methods of French and Spanish masters, and he began to formulate his artistic vision which he demonstrated in his first major painting upon his return to America. "I shall seek to achieve my broad effect from the very beginning," he declared.

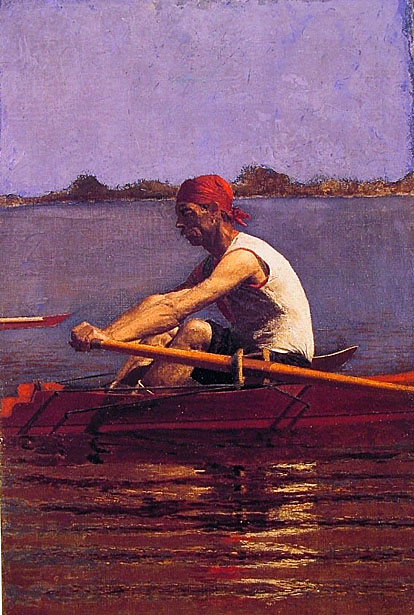

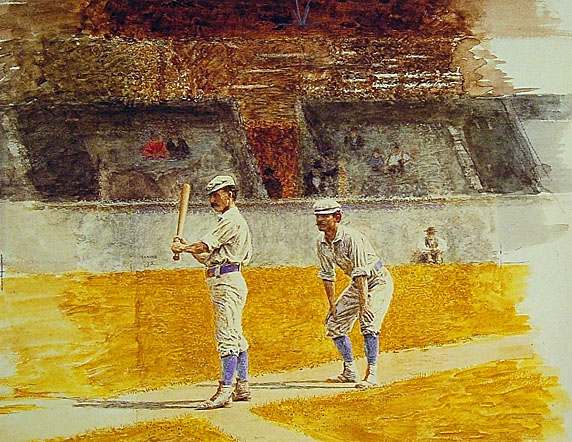

Eakins's first works upon his return from Europe included a large group of rowing scenes, eleven oils and watercolors in all, of which the first and most famous is The Champion Single Sculling, known also as 'Max Schmitt in a Single Scull'(1871). Both his subject and his technique drew attention. His selection of a contemporary sport was "a shock to the artistic conventionalities of the city". Eakins placed himself in the painting, in a scull behind Schmitt, his name inscribed on the boat.

Typically, the work entailed critical observation of the painting's subject, as well as preparatory drawings of the figure and perspective plans of the scull in the water. Its preparation and composition indicates the importance of Eakins' academic training in Paris. It was a completely original conception, true to Eakins' firsthand experience, and an almost startlingly successful image for the artist, who had struggled with his first outdoor composition less than a year before. His first known sale was the watercolor "The Sculler" (1874). Most critics judged the rowing pictures successful and auspicious, but after the initial flourish, Eakins never revisited the subject of rowing and went on to other sports themes.

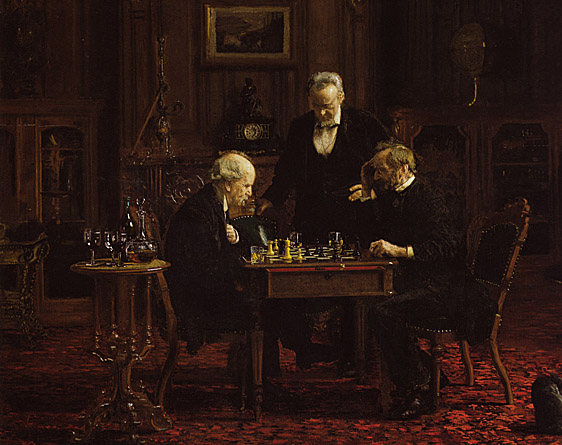

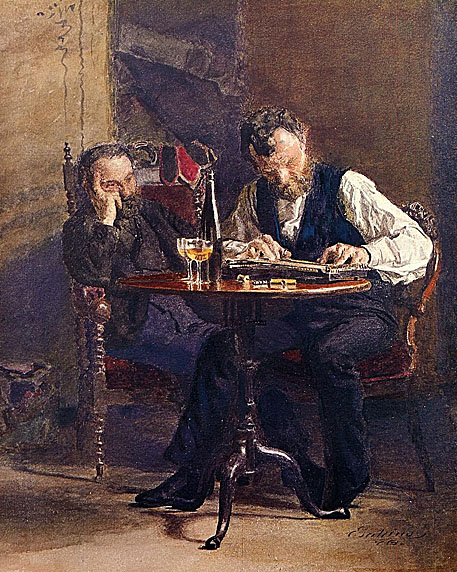

At the same time that he made these initial ventures into outdoor themes, Eakins produced a series of domestic Victorian interiors, often with his father, his sisters or friends as the subjects. "Home Scene" (1871), "Elizabeth at the Piano" (1875), "The Chess Players" (1876) , and "Elizabeth Crowell and her Dog" (1874), each dark in tonality, focus on the unsentimental characterization of individuals adopting natural attitudes in their homes. It was in this vein that in 1872 he painted his first large scale portrait, "Kathrin", in which the subject, Kathrin Crowell, is seen in dim light, playing with a kitten. In 1874 Eakins and Crowell became engaged; they were still engaged five years later, when Crowell died of meningitis in 1879.

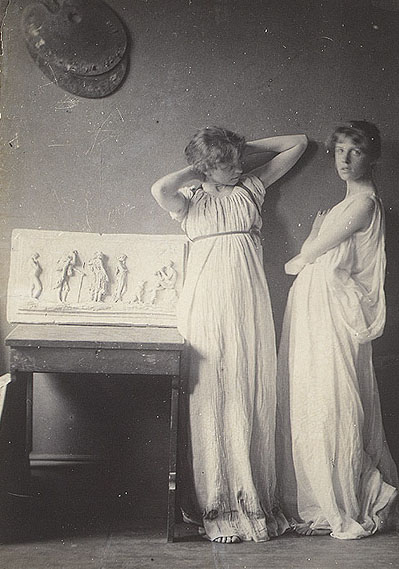

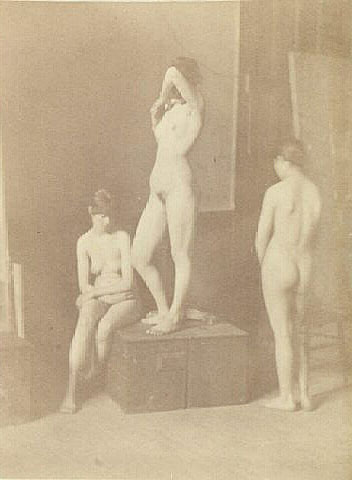

He returned to the Pennsylvania Academy to teach in 1876 as a volunteer after the opening of the school's new Frank Furness designed building, became a salaried professor in 1878, and rose to director in 1882. His teaching methods were controversial: there was no drawing from antique casts, and students received only a short study in charcoal, followed quickly by their introduction to painting, in order to grasp subjects in true color as soon as practical. He encouraged students to use photography as an aid to anatomy and the study of motion, and disallowed prize competitions. Although there was no specialized vocational instruction, students with aspirations for using their school training for applied arts, such as illustration, lithography, and decoration, were as welcome as students interested in becoming portrait artists.

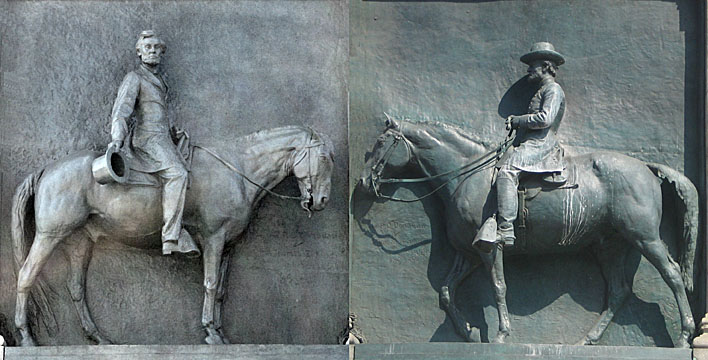

Most notable was his interest in the instruction of all aspects of the human figure, including anatomical study of the human and animal body and surgical dissection; there were also rigorous courses in the fundamentals of form, and studies in perspective which involved mathematics. As an aid to the study of anatomy, plaster casts were made from dissections, duplicates of which were furnished to students. A similar study was made of the anatomy of horses; acknowledging Eakins' expertise, in 1891 his friend the sculptor William Rudolf O'Donovan asked him to collaborate on the commission to create bronze equestrian reliefs of Abraham Lincoln and Ulysses S. Grant for the Soldiers' and Sailors' Memorial Arch in Grand Army Plaza In Brooklyn.

Owing to Eakins' devotion to working from life, the Academy's course of study was by the early 1880's the most "liberal and advanced in the world". Eakins believed in teaching by example and letting the students find their own way with only terse guidance. He stated his teaching philosophy bluntly, "A teacher can do very little for a pupil & should only be thankful if he don't hinder him … and the greater the master, mostly the less he can say." He believed that women should "assume professional privileges" as would men. Life classes and dissection were segregated but women had access to male models (who were nude but for loincloths). The line between impartiality and questionable behavior was a thin one. When a female student, Amelia Van Buren, asked about the movement of the pelvis, Eakins invited her to his studio, where he undressed and "gave her the explanation as I could not have done by words only". Such incidents, coupled with the ambitions of his younger associates to oust him and take over the school themselves, created tensions between him and the Academy's board of directors. He was ultimately forced to resign in 1886, for removing the loincloth of a male model in a class where female students were present. His poor judgment and provocative, disdainful behavior didn't help matters either. Eakins took the dismissal hard. His family was split, with his in-laws siding against him in public dispute. He struggled to protect his name against rumors and false charges, had bouts of ill health, and suffered a humiliation which he felt for the rest of his life. Eakins' popularity among the students was such that a number of them broke with the Academy and formed the Art Students' League of Philadelphia, where Eakins subsequently taught. He also lectured and taught at a number of other schools, including the Art Students League of New York, the National Academy of Design, Cooper Union, and the Art Students' Guild in Washington, D.C., until he withdrew from teaching by 1898.

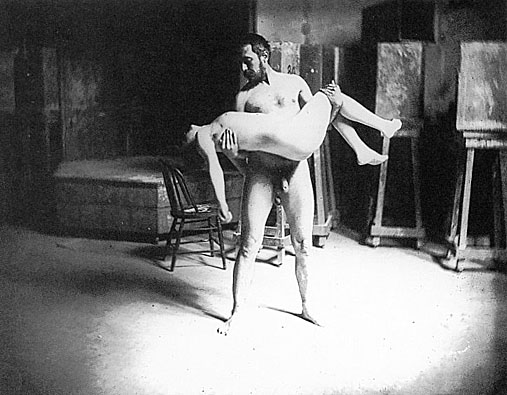

Eakins has been credited with having "introduced the camera to the American art studio". During his study abroad, he was exposed to the use of photography by the French realists, though the use of photography was still frowned upon as a shortcut by traditionalists. In the late 1870's he was introduced to the photographic motion studies of Eadweard Muybridge, particularly the equine studies, and became interested in using the camera to study sequential movement. He performed his own motion studies, usually involving the nude figure, and even developed his own technique for capturing movement on film. Where Muybridge's system relied on a series of cameras triggered to produce a sequence of individual photographs, Eakins preferred to use a single camera to produce a series of exposures on one negative. An excellent example is his painting A May Morning in the Park, which relied heavily on these motion studies to depict the true gait of the four horses pulling the coach of patron Fairman Rogers. But in typical fashion Eakins also employed wax figures and oil sketches to get the final effect he desired.

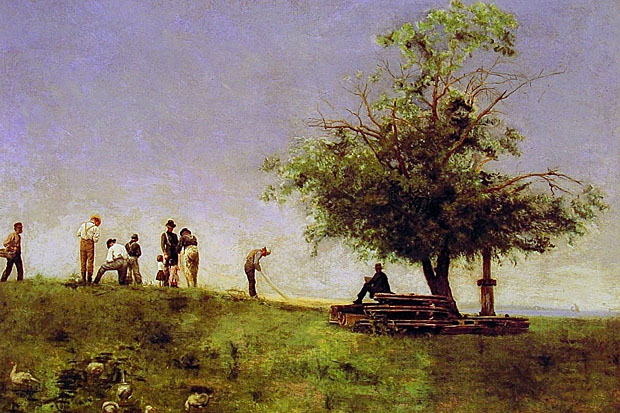

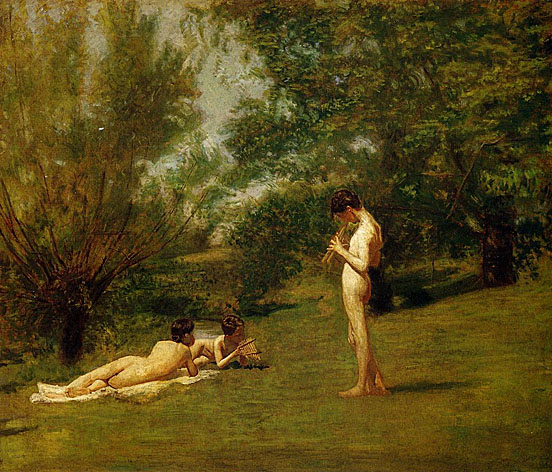

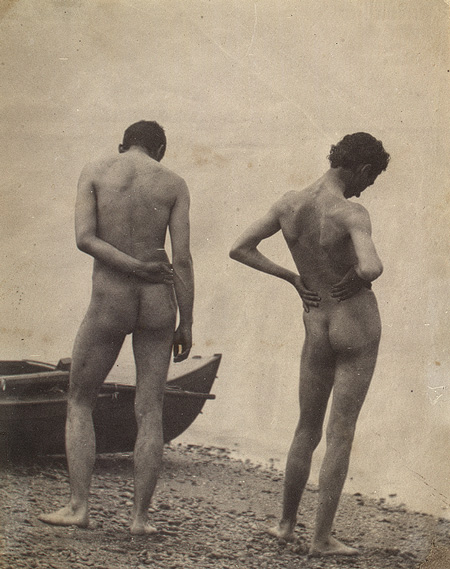

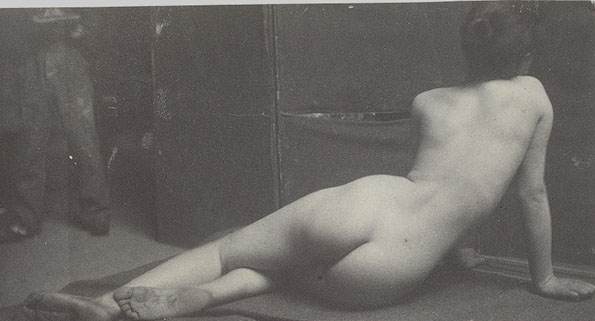

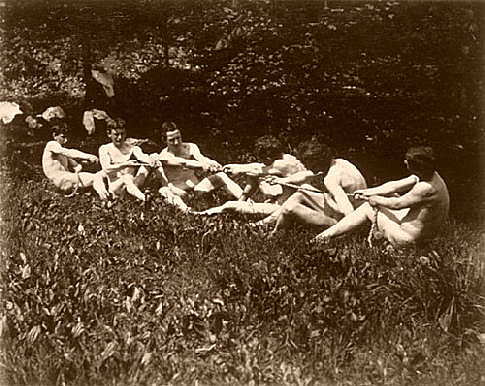

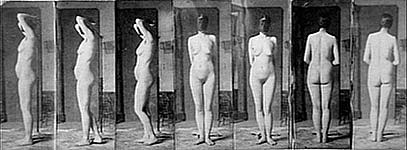

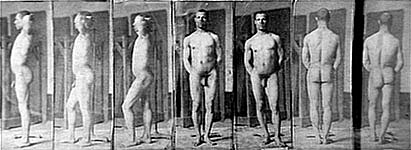

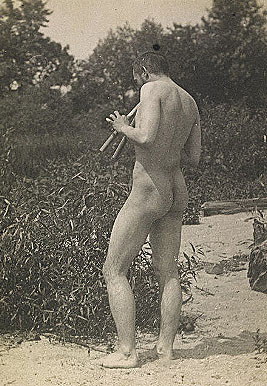

After Eakins obtained a camera in 1880, several paintings, such as Mending the Net (1881) and Arcadia (1883), are known to have been derived at least in part from his photographs. Some figures appear to be detailed transcriptions and tracings from the photographs by some device like a magic lantern, which Eakins took pains to cover up with oil paint. Eakins' methods appear to be meticulously applied, and rather than shortcuts, were likely used in a quest for accuracy and realism. The so-called "Naked Series", which began in 1883, were nude photos of students and professional models which were taken to show real human anatomy from several specific angles, and were often hung up and displayed for study at the school. Later, less regimented poses were taken indoors and out, of men, women, and children, including his wife. The most provocative and the only ones combining males and females were nude photos of Eakins and a female model. Although witnesses and chaperones were usually on site, and the poses were mostly traditional in nature, the sheer quantity of the photos and Eakins' overt display of them may have undermined his standing at the Academy. In all, about eight hundred photographs are now attributed to Eakins and his circle, most of which are figure studies, both clothed and nude, and portraits. No other American artist of his time matched Eakins' interest in photography, nor produced a comparable body of photographic works.

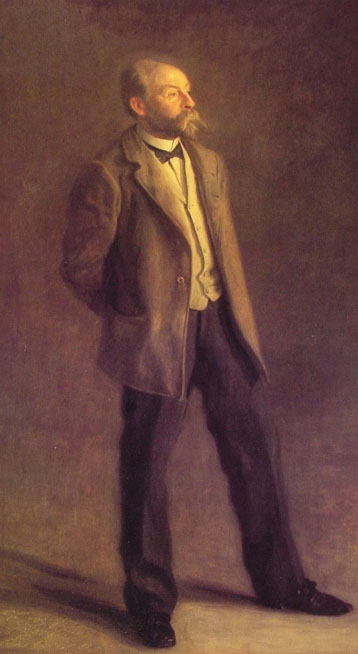

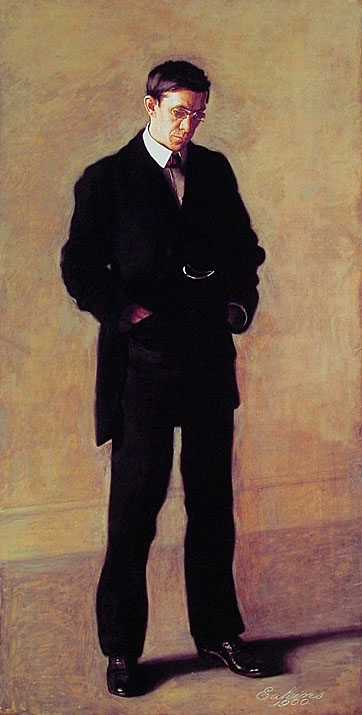

For Eakins, portraiture held little interest as a means of fashionable idealization or even simple verisimilitude--it provided the opportunity to reveal the character of an individual through the modeling of solid anatomical form. This meant that, notwithstanding his youthful optimism, he would never be a commercially successful portrait painter. Few commissions came his way. But his total output of some two hundred and fifty portraits is characterized by "an uncompromising search for the unique human being".

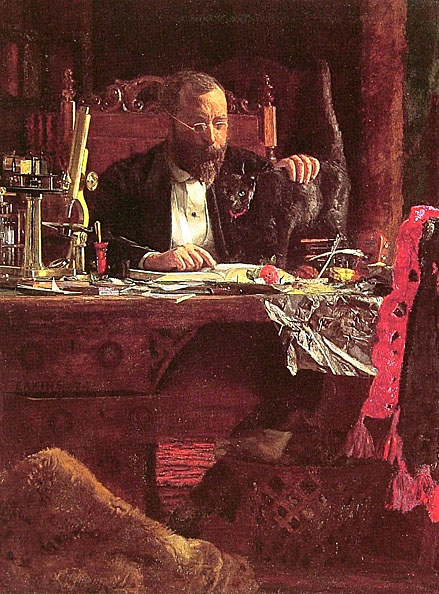

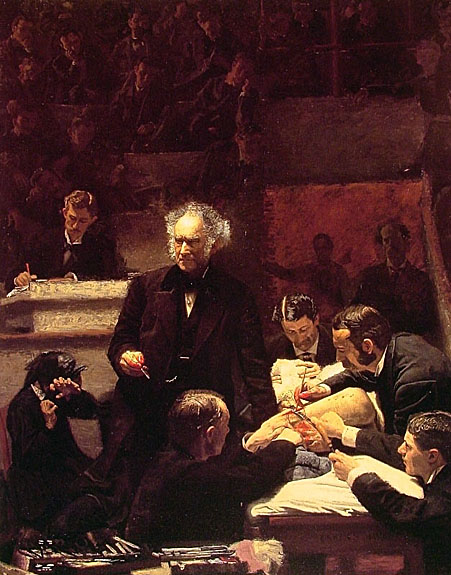

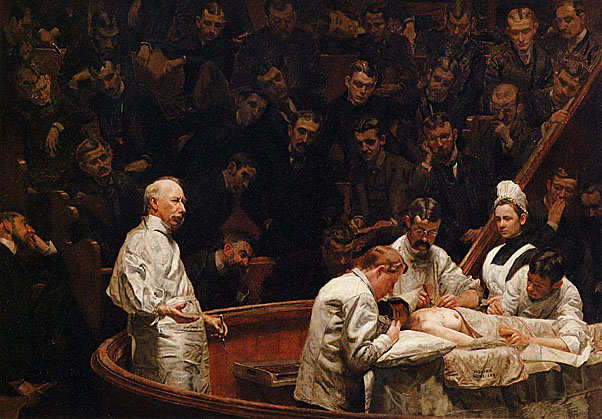

Often this search for individuality required that the subject be painted in their working environment. His Portrait of Professor Benjamin H. Rand (1874) was a prelude to what many consider his most important work. In The Gross Clinic (1875), a renowned Philadelphia surgeon, Dr. Samuel D. Gross, is seen presiding over an operation to remove part of a diseased bone from a patient's thigh. Gross lectures in an amphitheater crowded with students at Jefferson Medical College. Eakins spent nearly a year on the painting, again choosing a novel subject, the discipline of modern surgery, in which Philadelphia was in the forefront. He initiated the project and may have had the goal of a grand work befitting a showing at the Centennial Exhibition of 1876. Though rejected for the Art Gallery, the painting was shown on the centennial grounds at an exhibit of a U.S. Army Post Hospital. In sharp contrast, The Chess Players was accepted by the Committee and was much admired at the Centennial Exhibition, and critically praised.

Admired for its uncompromising realism, "The Gross Clinic" has an important place documenting the history of medicine-both because it honors the emergence of surgery as a healing profession (previously, surgery was associated primarily with amputation), and because it shows us what the surgical theater looked like in the nineteenth century. The painting is based on a surgery witnessed by Eakins, in which Gross treated a young man for osteomyelitis of the femur. Gross is pictured here performing a conservative operation as opposed to an amputation (which is how the patient would normally have been treated in previous decades). Here, surgeons crowd around the anesthetized patient in their frock coats. This is just prior to the adoption of a hygienic surgical environment. "The Gross Clinic" is thus often contrasted with Eakins's later painting "The Agnew Clinic", which depicts a cleaner, brighter, surgical theater. In comparing the two, we see the advancement in our understanding of the prevention of infection.

Interestingly, the sex of the patient is not established by anything concrete in the painting itself. This fact makes "The Gross Clinic" somewhat unique, as it presents the spectator with a body that is naked and exposed, and yet is not entirely legible as male or female. Another intriguing element of this painting is the lone woman in the painting, seen in the middle ground of the painting, cringing in distress. She can be read as a female relative of the patient, acting as a chaperone. Her dramatic figure functions as a strong contrast to the calm, professional demeanor of the men who surround the patient. This bloody and very blunt depiction of surgery was shocking at the time it was first exhibited, and remains so for many viewers of the painting today.

Stunningly illuminated, Dr. Gross is the embodiment of heroic rationalism, a symbol of American intellectual achievement. At 96 by 78 inches, it is one of the artist's largest works, and arguably his greatest. Eakins was elated by the project and stated that "it is very far better than anything I have ever done". But if Eakins hoped to impress his home town with the picture, he was to be disappointed; public reaction to the painting of a realistic surgical incision and the resultant blood was ambivalent at best, and it was finally purchased by the college for the unimpressive sum of $200. Eakins borrowed it for subsequent exhibitions, where it drew strong reactions, such as that of the New York Daily Tribune, which both acknowledged and damned its powerful image, "but the more one praises it, the more one must condemn its admission to a gallery where men and women of weak nerves must be compelled to look at it. For not to look it is impossible…No purpose is gained by this morbid exhibition, no lesson taught-the painter shows his skill and the spectators' gorge rises at it-that is all." The college now describes it thus: "Today the once maligned picture is celebrated as a great nineteenth-century medical history painting, featuring one of the most superb portraits in American art".

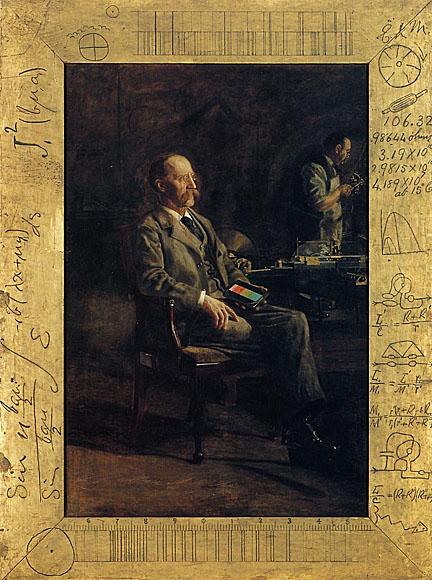

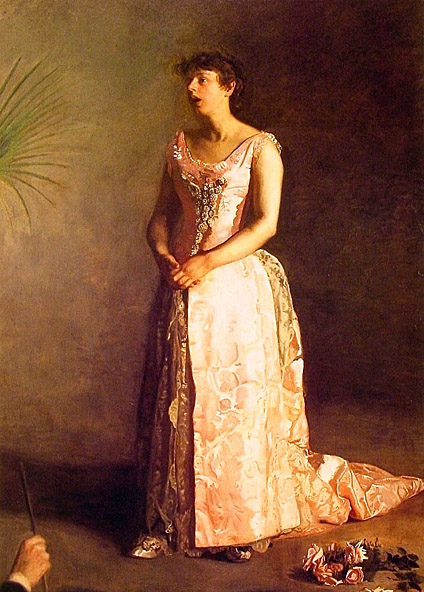

In 1876, Eakins completed a portrait of Dr. John Brinton, surgeon of the Philadelphia Hospital, and famed for his Civil War service. Done in a 'dignified', more informal setting than the Gross Clinic, it was a personal favorite of Eakins, and The Art Journal proclaimed "it is in every respect a more favorable example of this artist's abilities than his much-talked-of composition representing a dissecting room." Other outstanding examples of his portraits include The Agnew Clinic (1889), Eakins' most important commission and largest painting, which depicted another eminent American surgeon, Dr. David Hayes Agnew, performing a mastectomy; The Dean's Roll Call (1899), featuring Dr. James W. Holland, and Professor Leslie W. Miller (1901), portraits of educators standing as if addressing an audience; Frank Hamilton Cushing (ca. 1895), in which the prominent ethnologist is seen performing an incantation in a Zuñi pueblo; Professor Henry A. Rowland (1897), a brilliant scientist whose study of spectroscopy revolutionized his field; Antiquated Music (1900), in which Mrs. William D. Frismuth is shown seated amidst her collection of musical instruments; and The Concert Singer (1890-92), for which Eakins asked Weda Cook to sing "O rest in the Lord", so that he could study the muscles of her throat and mouth. In order to replicate the proper deployment of a baton, Eakins enlisted an orchestra conductor to pose for the hand seen in the lower left-hand corner of the painting.

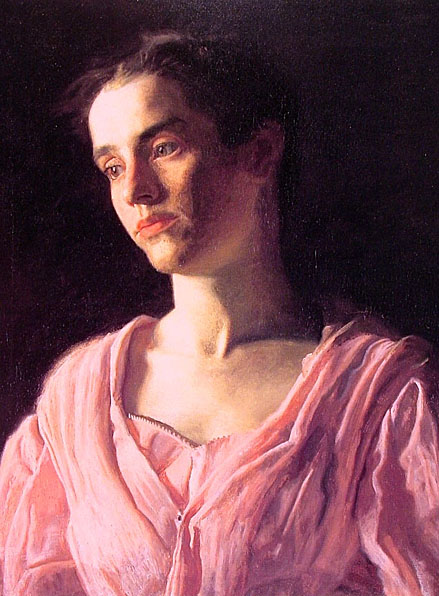

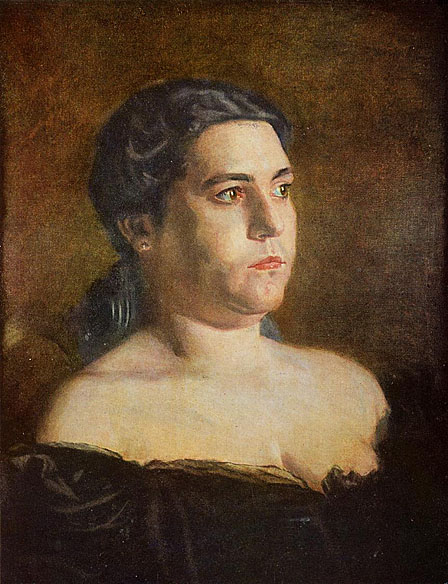

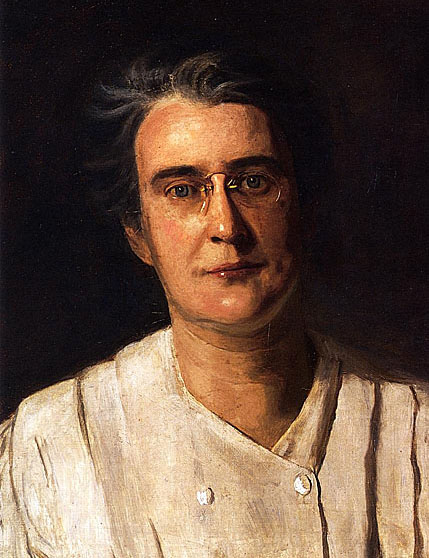

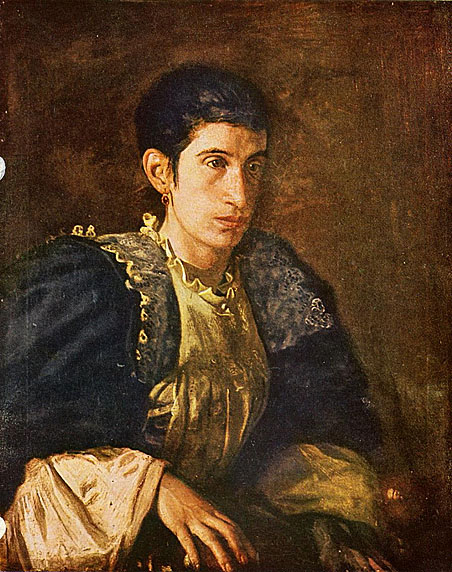

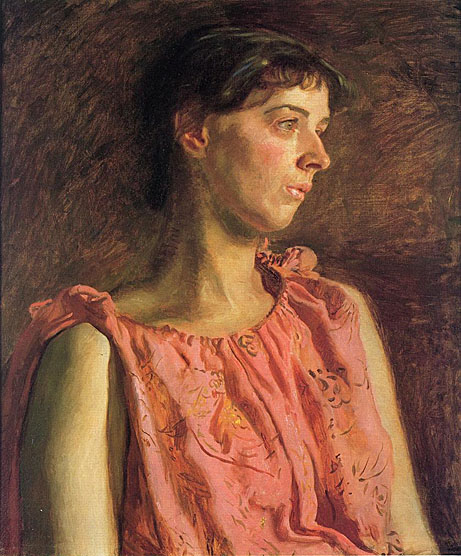

Of Eakins' later portraits, many took as their subjects women who were friends or students. Unlike most portrayals of women at the time, they are devoid of glamour and idealization. For Letitia Wilson Jordan (1888), Eakins painted the sitter wearing the same evening dress in which he had seen her at a party. She is a substantial presence, a vision quite different from the era's fashionable portraiture. So, too, his portrait of Maud Cook (1895), where the obvious beauty of the subject is noted with "a stark objectivity".

The portrait of Miss Amelia C. Van Buren (ca. 1890), a friend and former pupil, suggests the melancholy of a complex personality, and has been called "the finest of all American portraits". Even Susan Macdowell Eakins, a strong painter and former student who married Eakins in 1884, was not sentimentalized: despite its richness of color, The Artist's Wife and His Setter Dog (ca. 1884-89) is a penetratingly candid portrait.

Eakins centered his attention on Van Buren's face and hands, creating through subtle means-deft highlights, distant glance, and relaxed yet tensile hands-an image of great psychological complexity. Her weary head leans on her curved hand, while her other hand rests in her lap. She looks absently towards but not into the strong light, which emanates from the left and defines her face. Eakins establishes in this passage Van Buren's character, her quiet strength and determination. And it is in this manner, through a portrait of his friend and fellow artist's contemplative state, that Eakins comments on his own achievements at the end of a long, tumultuous career.

The sitter, Van Buren, is an elusive, but fascinating figure. Born in 1856 she was recorded by 1880 as an "artist in color." Her lifelong friendship with the Eakins family began when she took the artist's life classes at the Pennsylvania Academy in 1884. Van Buren later became interested in photography, an enthusiasm she may have initially acquired from Eakins, who himself had used photographs extensively in his work. She turned from painting to work exclusively as a photographer. She may have found the expressive potential of photography challenging, seeing photography as an art form in its own right, and, too, Van Buren may have believed that for a woman, photography offered a better chance for recognition.

Duncan Phillips appreciated Eakins's brilliant sense of color and texture, as well as the artist's respect for the sitter as an individual; writing:

Expressing his belief in Eakins's influential place in the history of American art, Phillips stated that "the American old masters pointed the way and they (modern American artists) have followed."

Some of his most vivid portraits resulted from a late series done for the Catholic Clergy, which included paintings of a cardinal, archbishops, bishops, and monsignors. As usual, most of the sitters were engaged at Eakins' request, and were given the portraits when Eakins had completed them. In portraits of His Eminence Sebastiano Cardinal Martinelli (1902), Archbishop William Henry Elder (1903), and Monsignor James P. Turner (ca. 1906), Eakins took advantage of the brilliant vestments of the offices to animate the compositions in a way not possible in his other male portraits.

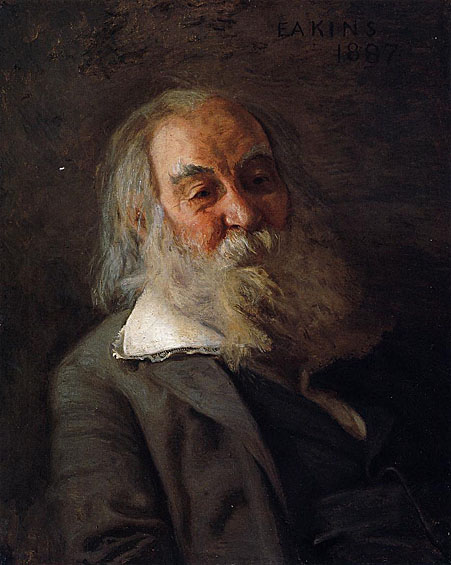

Deeply affected by his dismissal from the Academy, Eakins's later career focused on portraiture. His steadfast insistence on his own vision of realism, in addition to his notoriety from his school scandals, combined to impact his income negatively in later years. Even as he approached these portraits with the skill of a highly trained anatomist, what is most noteworthy is the intense psychological presence of his sitters. However, it was precisely for this reason that his portraits were often rejected by the sitters or their families. As a result, Eakins came to rely on his friends and family members to model for portraits. His portrait of Walt Whitman (1887-1888) was the poet's favorite.

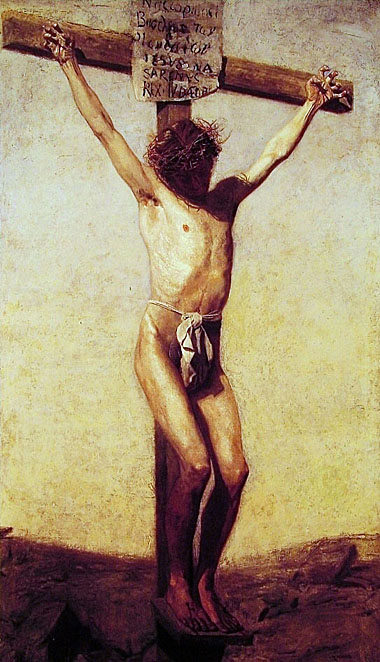

Eakins' lifelong interest in the figure, nude or nearly so, took several thematic forms. The rowing paintings of the early 1870's constitute the first series of figure studies. In Eakins' largest picture on the subject, The Biglin Brothers Turning the Stake (1873), the muscular dynamism of the body is given its fullest treatment.

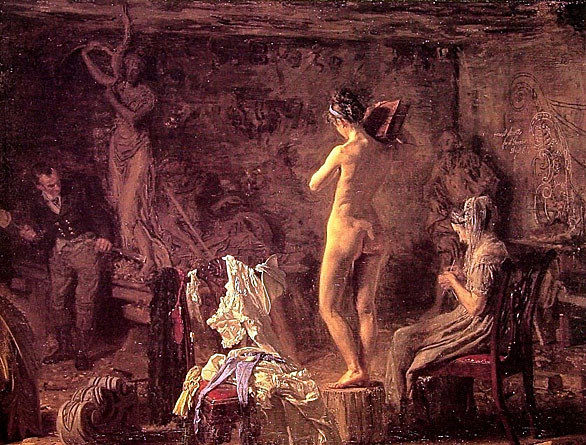

In 1877 he painted the female nude as integral to a historical subject, William Rush Carving his Allegorical Figure of the Schuylkill River, even though there is no evidence that the model who posed for Rush did so in the nude. The Centennial Exhibition of 1876 helped foster a revival in interest in Colonial America and Eakins participated with an ambitious project employing oil studies, wax and wood models, and finally the portrait in 1877. William Rush was a celebrated Colonial sculptor and ship carver, a revered example of an artist-citizen who figured prominently in Philadelphia civic life and a founder of the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts where Eakins had started teaching. Despite his sincerely depicted reverence for Rush, Eakins' treatment of the human body once again drew criticism. This time it was the nude model and her heaped-up clothes depicted front and center, with Rush relegated to the deep shadows in the left background, that stirred dissatisfaction. Nonetheless, Eakins found a subject which referenced his native city, an earlier Philadelphia artist, and allowed for an assay on the female nude seen from behind. When he returned to the subject many years later, the narrative became more personal: In William Rush and his Model (1908), gone are the chaperon and detailed interior of the earlier work. The professional distance between sculptor and model has been eliminated, and the relationship has become intimate. The nude is seen from the front, being helped down from the model stand by an artist who bears a strong resemblance to Eakins.

The Swimming Hole (1884-85) features Eakins' finest studies of the nude, in his most successfully constructed outdoor picture. The figures are those of his friends and students, and include a self-portrait. Although there are photographs by Eakins which relate to the painting, the picture's powerful pyramidal composition and sculptural conception of the individual bodies are completely distinctive pictorial resolutions. The work was painted on commission, but was refused.

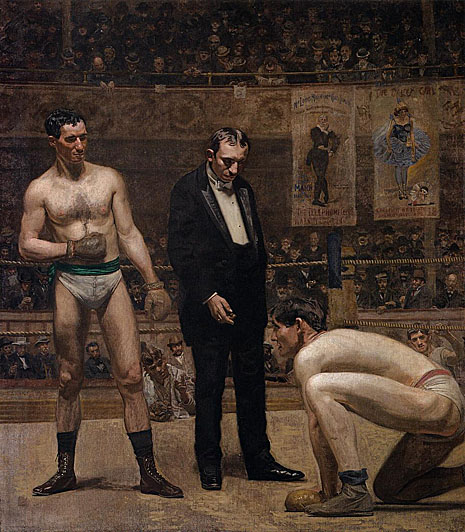

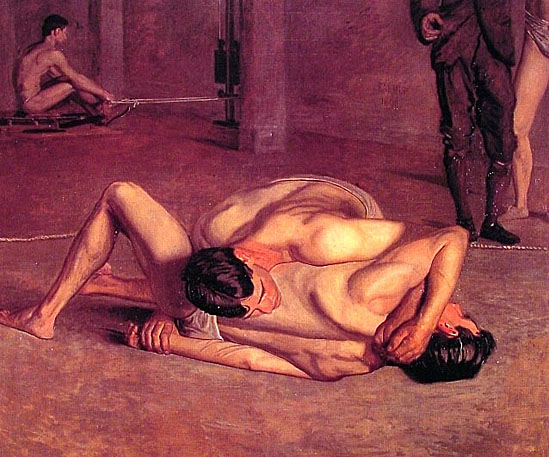

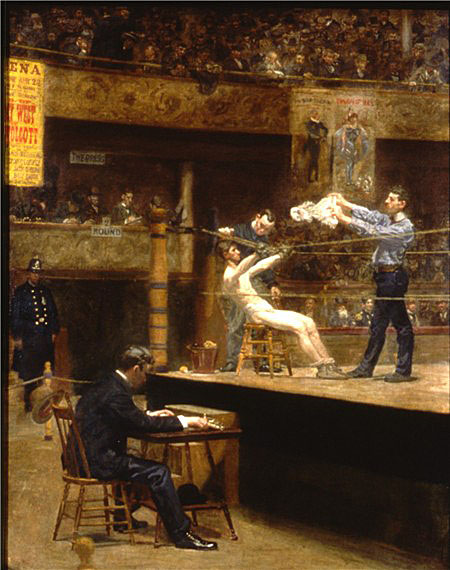

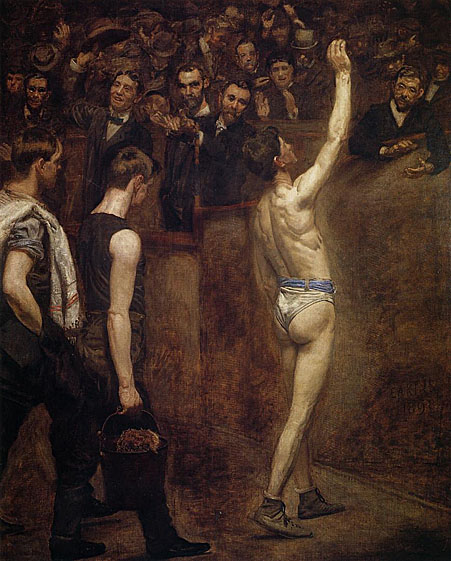

In the late 1890's Eakins returned to the male figure, this time in a more urban setting. Taking the Count (1896), a painting of a prizefight, was his second largest canvas, but not his most successful composition. The same may be said of Wrestlers (1899). More successful was Between Rounds (1899), for which boxer Billy Smith posed seated in his corner at Philadelphia's Arena; in fact, all the principles were posed for by models re-enacting their roles in what had been an actual fight. Salutat (1898), a frieze-like composition in which the main figure is isolated, "is one of Eakins' finest achievements in figure-painting."

In his later years Eakins persistently asked his female portrait models to pose in the nude, a practice which would have been all but prohibited in conventional Philadelphia society. Inevitably, his desires were frustrated.

Eakins married Susan Hannah MacDowell, one of his students at the Academy, in 1884. She was the fifth of eight children of a Philadelphia engraver, well known in the artistic community.

She was 25 when Eakins met her at the Hazeltine Gallery where "The Gross Clinic" was being exhibited in 1875. Unlike many, she was impressed by the controversial painting and she decided to study with him at the Academy, which she attended for 6 years, adopting a sober, realistic style similar to her teacher's. She was an outstanding student and winner of the Mary Smith prize for the best painting by a matriculating woman artist.

After their marriage, she only painted sporadically and spent most of her time supporting her husband's career, entertaining guests and students, and faithfully backing him in his difficult times with the Academy, even when some members of her family aligned against Eakins.

She and Eakins both shared a passion for photography, both as photographers and subjects, and employed it as a tool for their art. She also posed nude for many of his photos and took images of him. Both had separate studios in their home.

After his death in 1916, she returned to painting, adding considerably to her output right up to the 1930's, in a style that became warmer, looser, and brighter in tone. She died in 1938. Thirty-five years after her death, in 1973, she had her first one-woman exhibition at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts.

Late in life Eakins did experience some recognition. In 1902 he was made a National Academician. In 1914 the sale of a portrait study of D. Hayes Agnew for the Agnew Clinic to Dr. Albert C. Barnes precipitated much publicity when rumors circulated that the selling price was fifty thousand dollars. In fact, Barnes bought the painting for four thousand dollars.

In the year after his death Eakins was honored with a memorial retrospective at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and in 1917-18 the Pennsylvania Academy followed suit. Susan Macdowell Eakins did much to preserve his reputation, including gifting the Philadelphia Museum of Art with more than fifty of her husband's oil paintings. After her death in 1938, other works were sold off, and eventually another large collection of art and personal material was purchased by Joseph Hirshhorn, and now is part of the Hirshhorn Museum's collection. Since then, Eakins' home in North Philadelphia was put on the National Register of Historic Places list in 1966, and Eakins Oval, across from the Philadelphia Museum of Art on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway, was named for the artist.

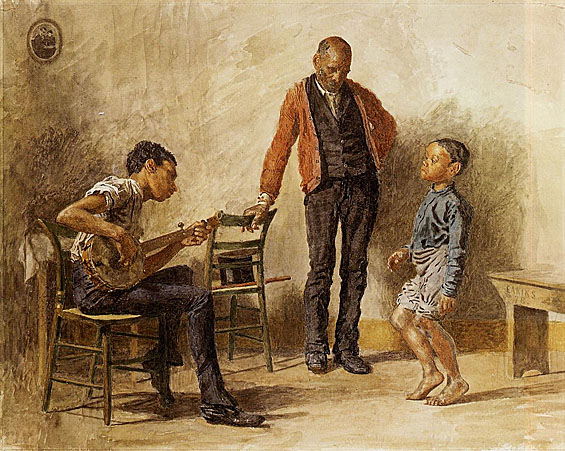

Eakins's attitude toward realism in painting, and his desire to explore the heart of American life proved influential. He taught hundreds of students, among them his future wife Susan Macdowell, African-American painter Henry Ossawa Tanner, and Thomas Anshutz, who taught, in turn, Robert Henri, George Luks, John Sloan, and Everett Shinn, future members of the Ashcan School, and artistic heirs to Eakins' philosophy. Though his is not a household name, and though during his lifetime Eakins struggled to make a living from his work, today he is regarded as one of the most important American artists of any period.

Since the 1990's, Eakins has emerged as a major figure in sexuality studies in art history, for both the seeming homoeroticism of his male nudes and for the complexity of his attitudes toward women. Controversy shaped much of his career as a teacher and as an artist. He insisted on teaching men and women "the same", used nude male models in female classes and vice versa, and was accused of abusing female students. Recent scholarship suggests that these controversies were grounded in more than the "puritanical prudery" of his colleagues (as has been assumed). Today, scholars see these controversies as caused by a combination of factors such as the bohemianism of Eakins and his circle (in which students, for example, sometimes modeled in the nude for each other), and Eakins's inclination toward provocative behavior.

On November 11, 2006 the Board of Trustees at Thomas Jefferson University agreed to sell The Gross Clinic to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., and the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas for a record $68,000,000, the highest price for an Eakins painting as well as a record price for an individual American-made portrait. On December 21, 2006, a group of donors agreed to pay $68,000,000 in order to keep the painting in Philadelphia. It will be displayed at the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts.

On October 29, 1917, Robert Henri wrote an open letter to the Art Students League about Eakins:

In 1982 Lloyd Goodrich completed his comprehensive study of Eakins by writing, in part:

John Canaday, art critic for The New York Times, in 1964:

In accord with late nineteenth-century attitudes about education, she has progressed from infantile pursuits to more advanced stages of development. By stacking up the blocks, the child practices language and motor skills. Eakins communicates his niece's serious concentration by arranging her into a solid, pyramidal mass that is nearly life-size and aligned geometrically with the toys, blocks, and paved walk. The brown bricks show Eakins' expertise in mechanical drafting and, with the dark shrubbery, set off Ella's sunlit figure.

Eakins' skill in modeling with light and shadow also marks three small oil studies in the National Gallery of Art. These quick life sketches of African-American subjects are the same size as their final pictures. Two relate to Negro Boy Dancing of 1878, a watercolor now in New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art. For an oil painting of 1908 now in The Brooklyn Museum, Eakins made 'The Chaperone', in which an old servant knits while a young girl poses nude for a sculptor.

_ca_1900.jpg)

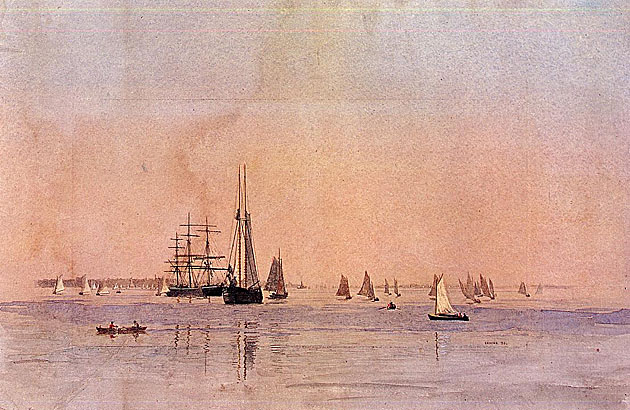

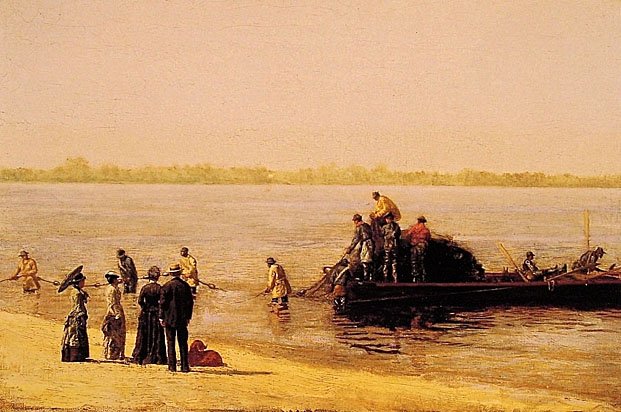

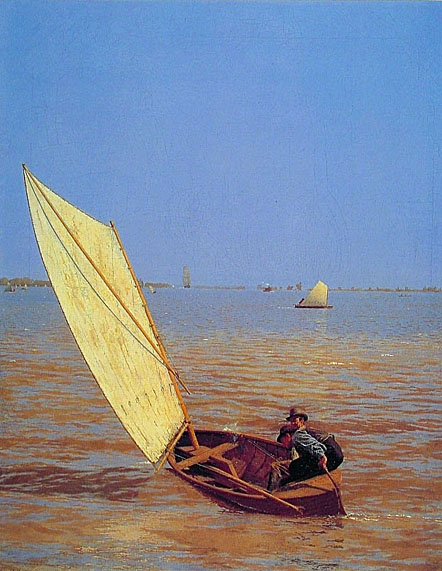

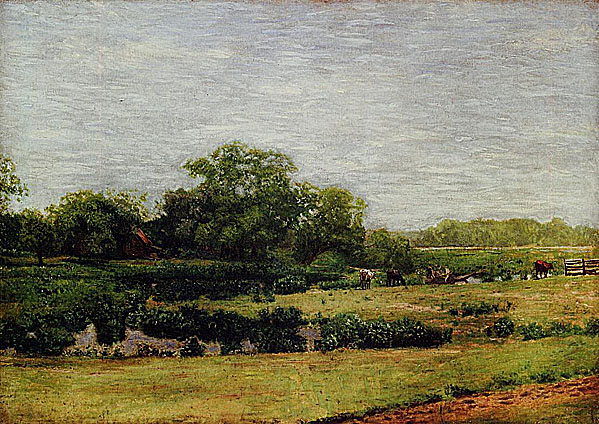

Drifting simply and directly captures the play of light across the water and on the sails of the boats. Eakins reduced the scene to a few basic elements: the shoreline; a tall, dark sail silhouetted against the sky with the hull of another boat positioned at an oblique angle behind it; and a small boat with a white sail in the right foreground. Although 'Drifting' would not have required the complex calculations needed to depict the foreshortening of the racing shells seen in his well-known rowing images, the artist may have used perspective sketches to calibrate the wave patterns and the recession in space toward the horizon line. The extraordinary detail in this work may also owe something to Eakins' experiments with photography.

_1900.jpg)

_ca_1890_95.jpg)

Eakins constructed his compositions with painstaking care. Eakins made a number of meticulous perspective drawings for this picture. The painting that resulted is so accurate; scholars were able to determine the precise length of the boat and to pinpoint the exact time of day to 7:20 p.m. Eakins actually wrote an entire textbook on the subject of linear perspective, though it was never published. His well-known command of perspective was matched by a less known, but equally rigorous quest to record natural light faithfully.

Source: Art Renewal Center

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.