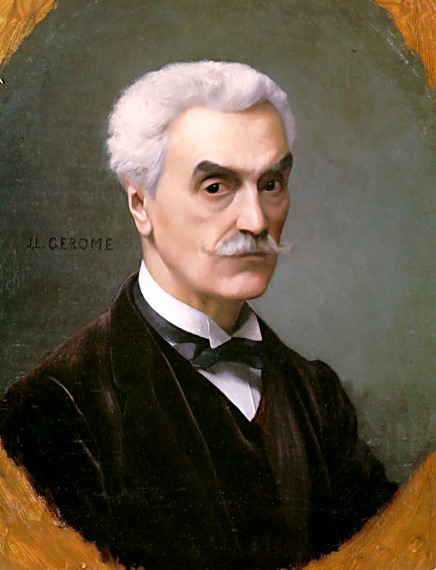

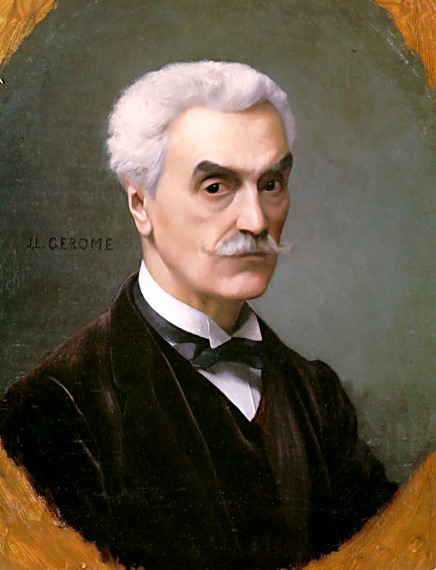

French Orientalist Painter and Draftsman

1824 - 1904

Born at Vesoul (Haute-Saône), he went to Paris in 1840 where he studied under Paul Delaroche, whom he accompanied to Italy (1843-1844). He visited Florence, Rome, the Vatican and Pompeii, but he was more attracted to the world of nature. Taken by a fever, he was forced to return to Paris in 1844. On his return he followed, like many other students of Delaroche, into the studio of Charles Gleyre and studied there for a brief time. He then attended the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. In 1846 he tried to enter the prestigious Prix de Rome, but failed in the final stage because his figure drawing was not adequate enough.

He tried to improve his skills by painting The Cockfight (1846), an academic exercise with a nude young man and a lightly draped girl with two fighting cocks and in the background the Bay of Naples. He sent this painting to the Salon of 1847, which gained him a third-class medal. This work was seen as the epitome of the Neo-Grec movement that had formed out of Gleyre's studio (such as Henri-Pierre Picou (1824-1895) and Jean-Louis Hamon), and was championed by the influential French critic Theophile Gautier.

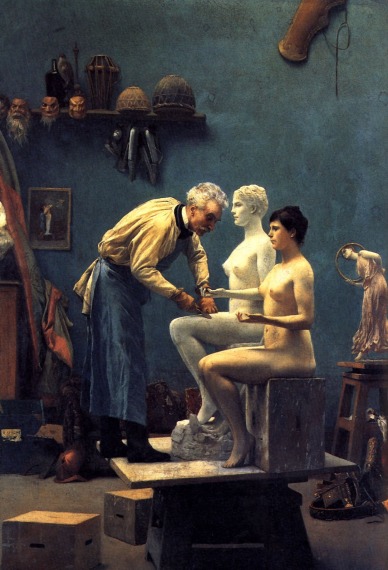

Gérôme abandoned his dream of winning the Prix de Rome and took advantage of his sudden success. His paintings The Virgin, the Infant Jesus and St John (private collection) and Anacreon, Bacchus and Cupid (Musée des Augustins, Toulouse, France) took a second-class medal in 1848. In 1849 he produced the paintings Michelangelo (also called in his studio) image of the painting and A portrait of a Lady (Musée Ingres, Montauban).

In 1851 he decorated a vase, later offered by Emperor Napoleon III of France to Prince Albert, now part of the Royal Collection at St. James's Palace, London. He exhibited Bacchus and Love, Drunk, a Greek Interior and Souvenir d'Italie, in 1851; Paestum (1852); and An Idyll (1853).

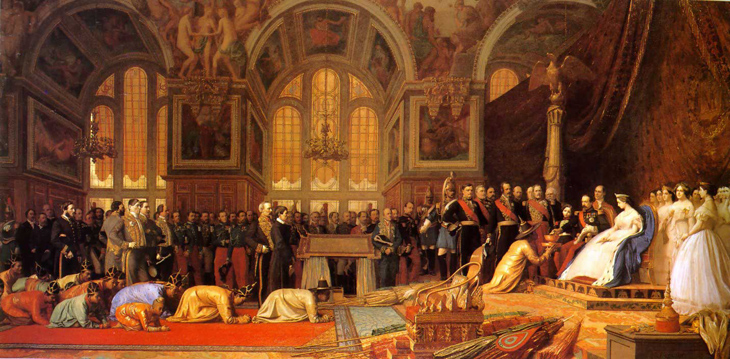

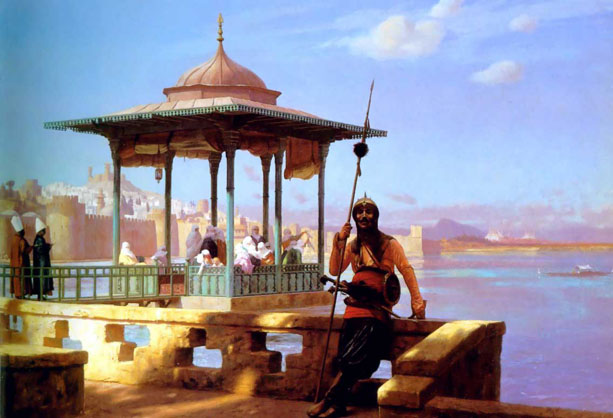

In 1822 Gérôme received a commission by Alfred Emilien Comte de Nieuwerkerke, Surintendant des Beaux-Arts to the Court of Napoleon III, for the painting of a large historical canvas, the Age of Augustus image of the painting. In this canvas he combines the birth of Christ with conquered nations paying homage to Augustus. Thanks to a considerable down payment, he was able to travel in 1853 to Constantinople, together with the actor Edmond Got. This would be the first of several travels to the East: in 1854 he made another journey to Turkey and the shores of the Danube, where he was present at a concert of Russian conscripts, making music under the threat of a lash.

In 1854 he completed another important commission of decorating the Chapel of St. Jerome in the Church of St. Séverin in Paris. His Last communion of St. Jerome in this chapel reflects the influence of the school of Ingres on his religious works.

To the exhibition of 1855 he contributed a Pifferaro, a Shepherd, A Russian Concert The Age of Augustus and Birth of Christ. The last was somewhat confused in effect, but in recognition of its consummate ability the State purchased it. However the modest painting, A Russian Concert (also called Recreation in the Camp) was more appreciated than his huge canvasses.

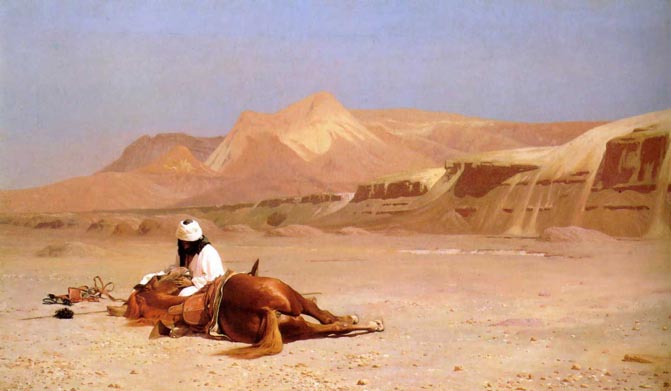

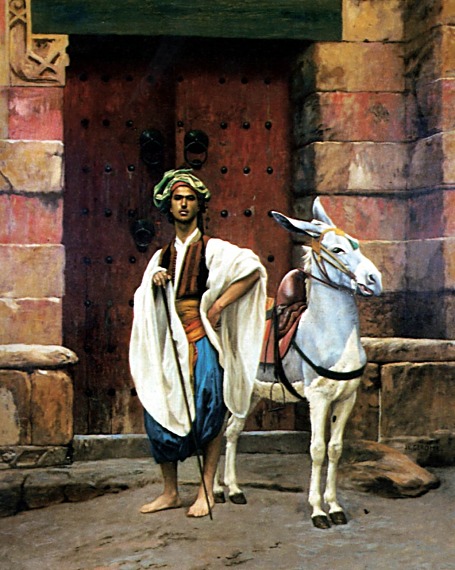

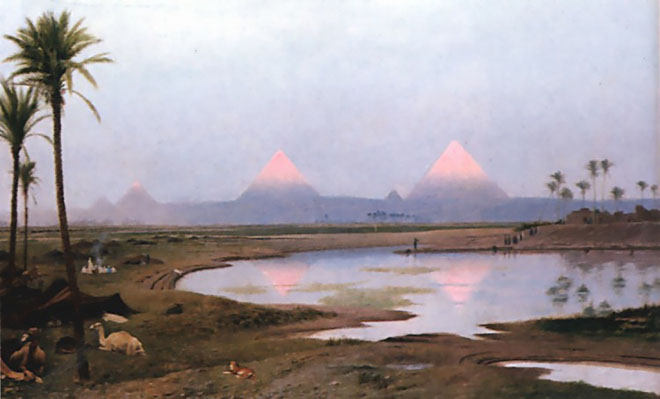

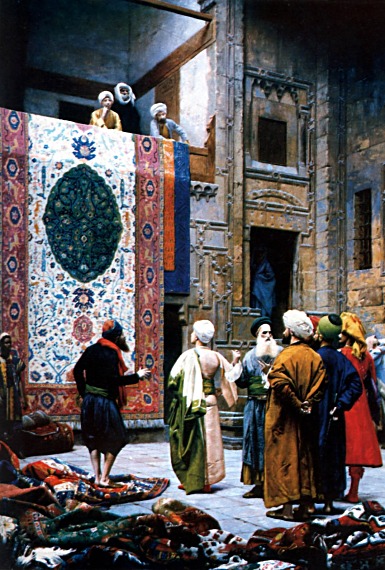

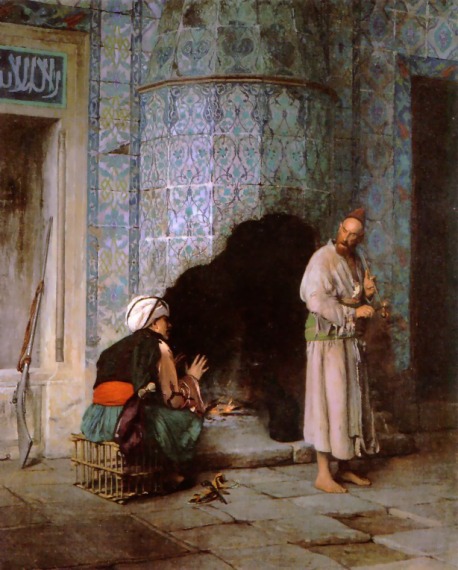

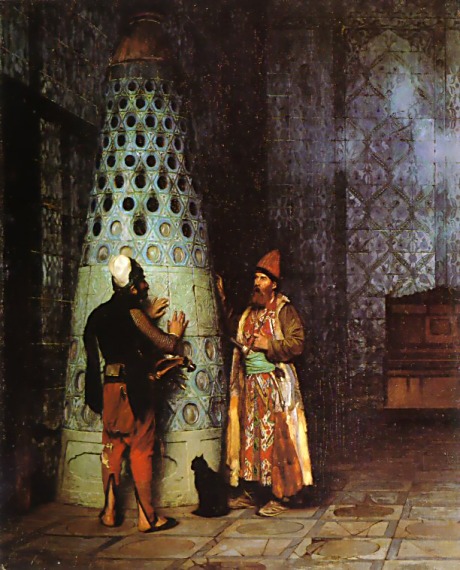

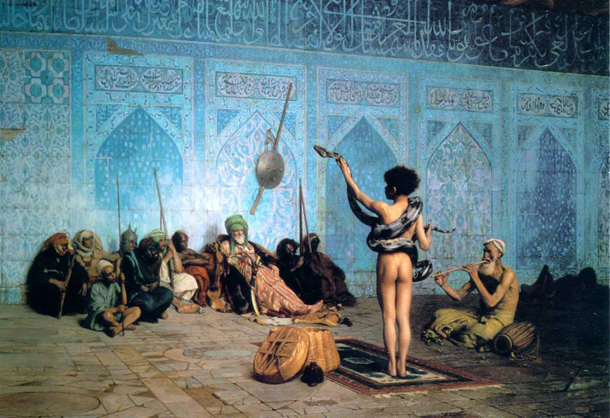

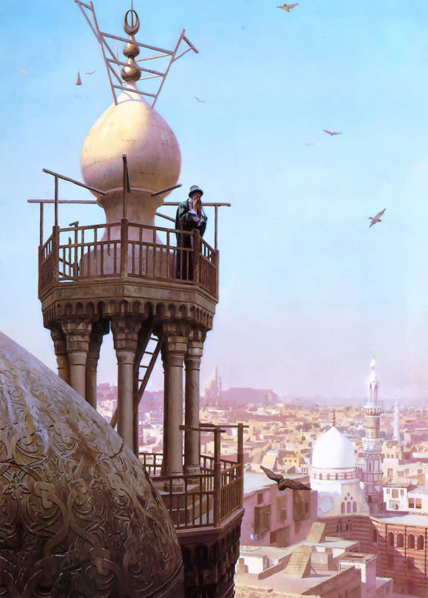

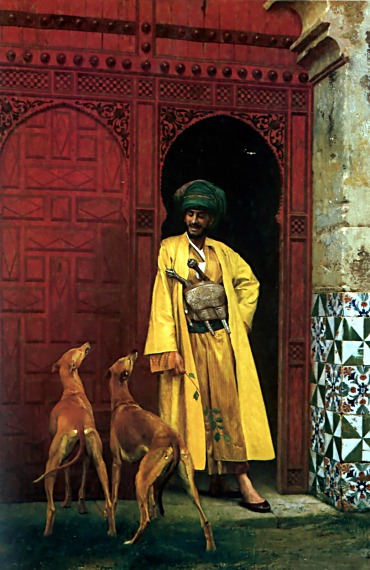

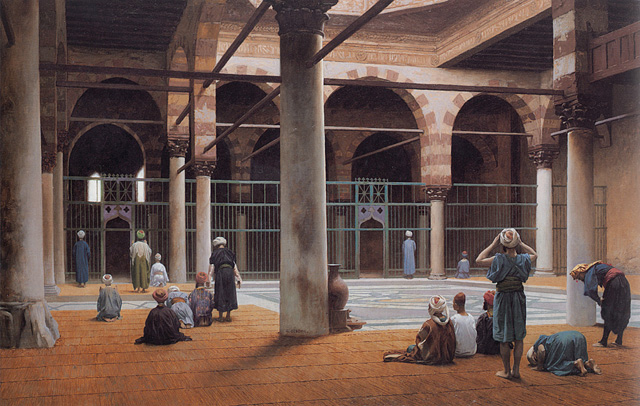

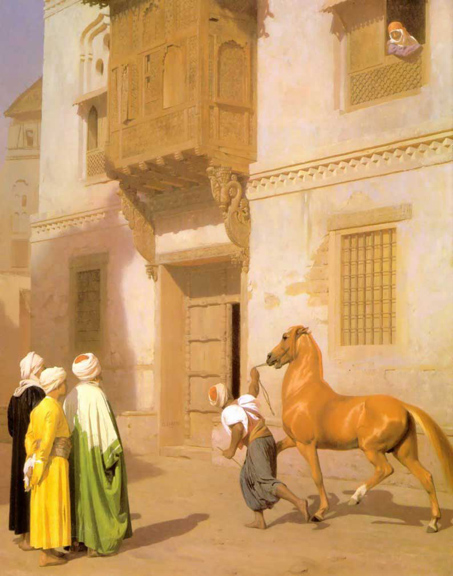

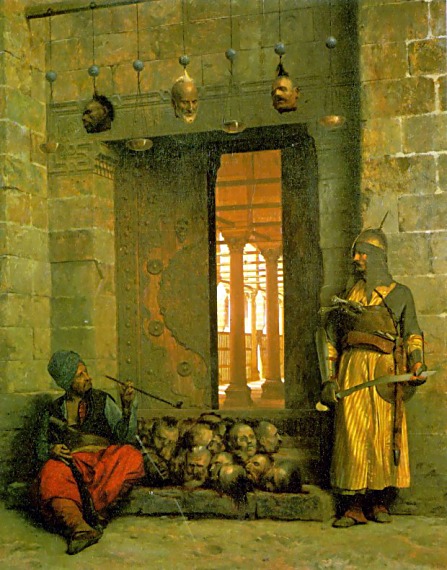

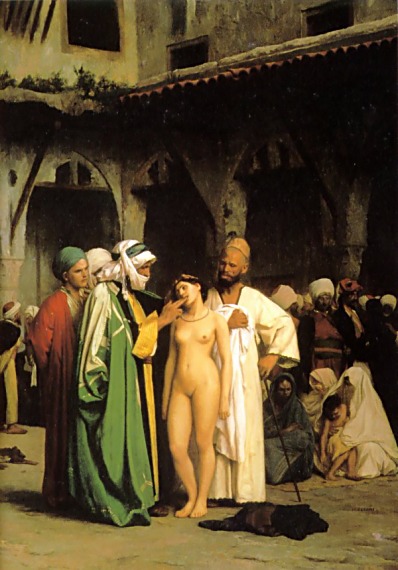

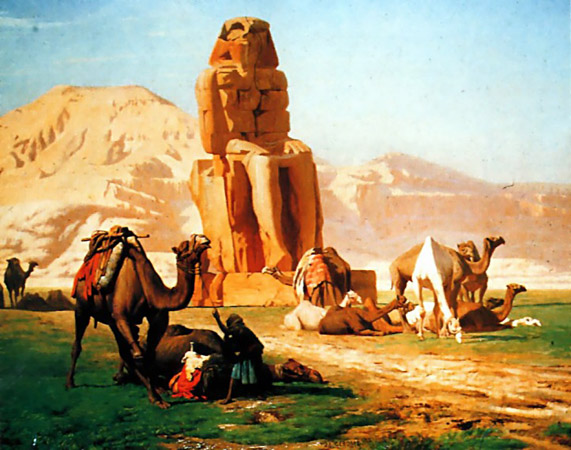

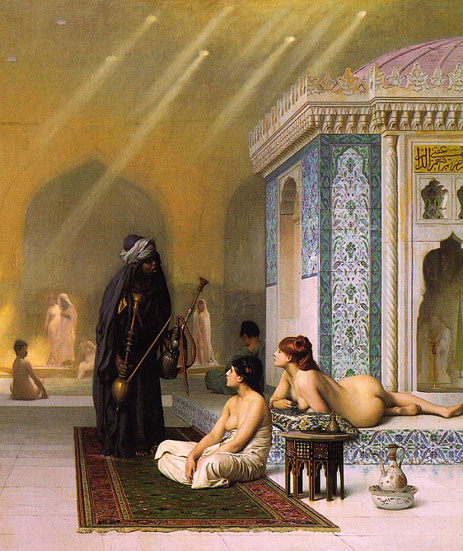

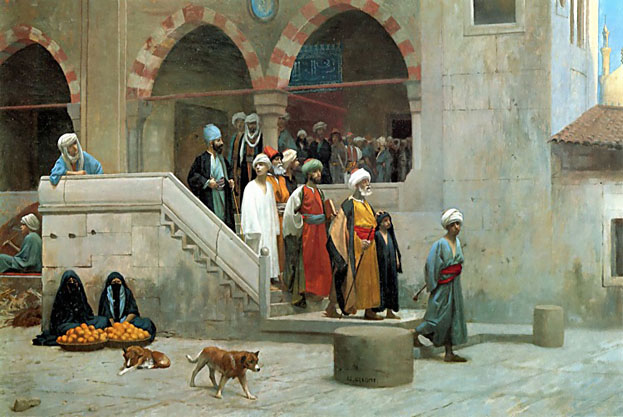

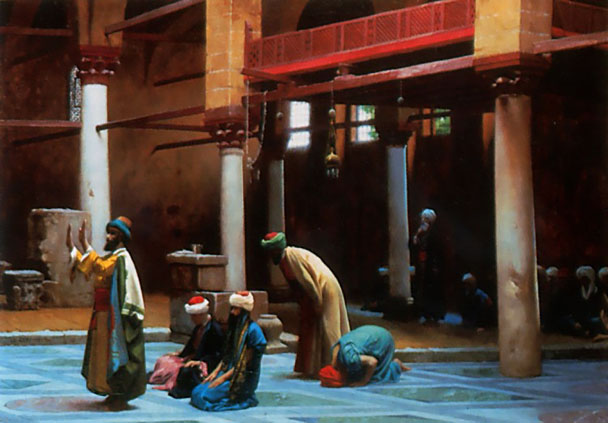

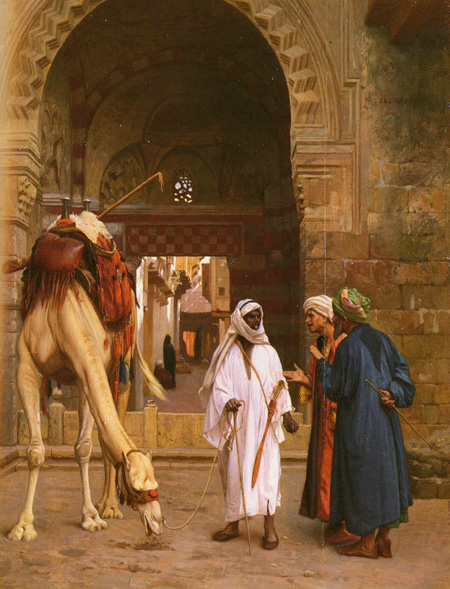

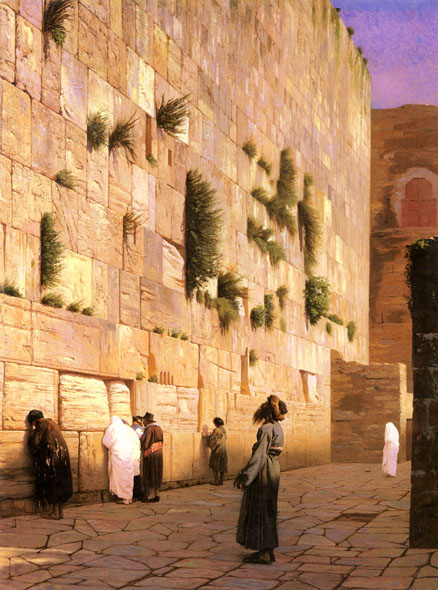

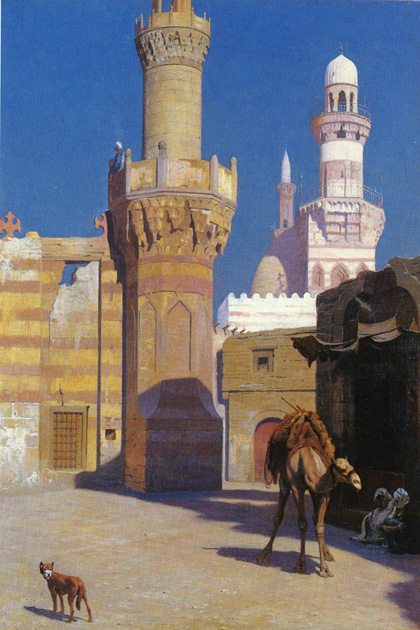

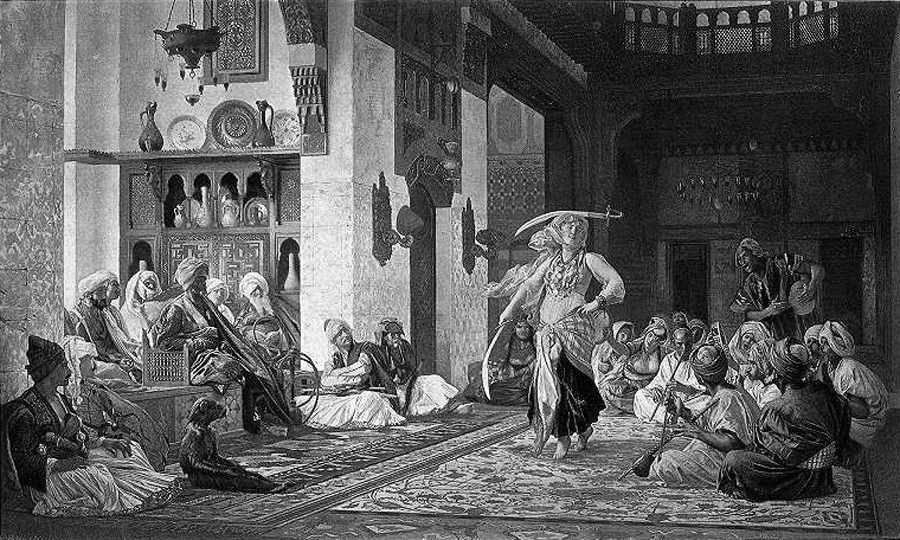

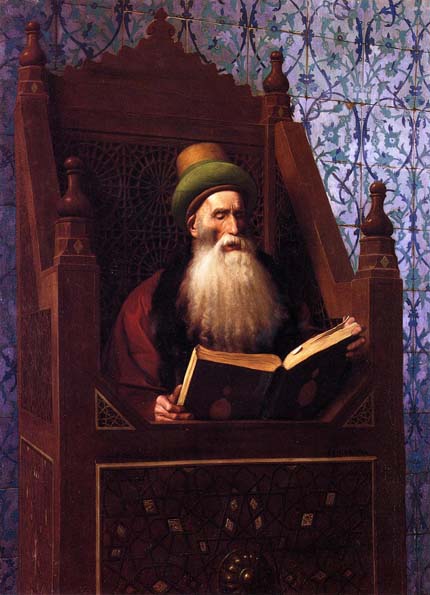

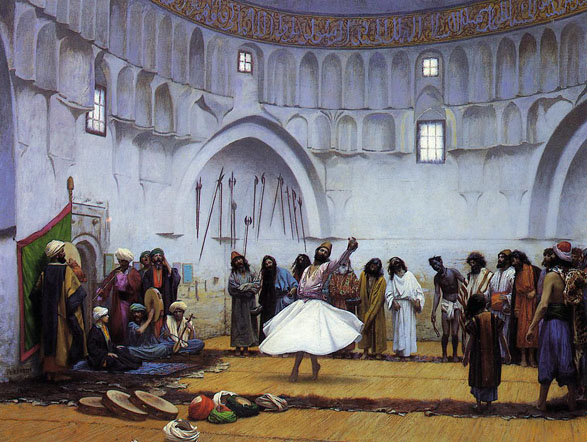

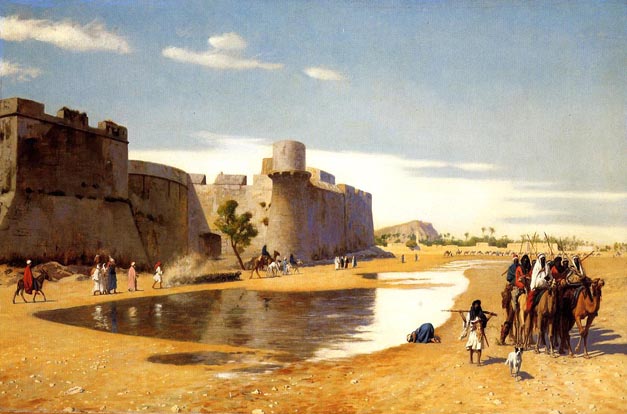

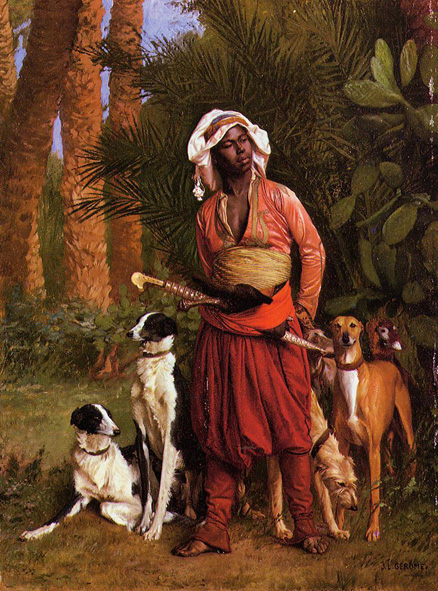

In 1856 he visited Egypt for the first time. This would herald the start of many orientalist paintings depicting Arab religion, genre scenes and North African landscapes.

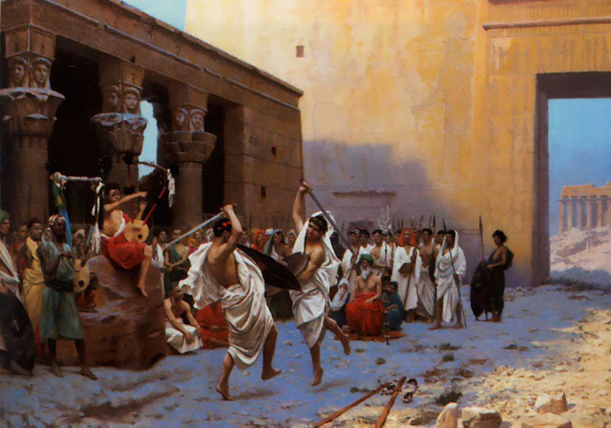

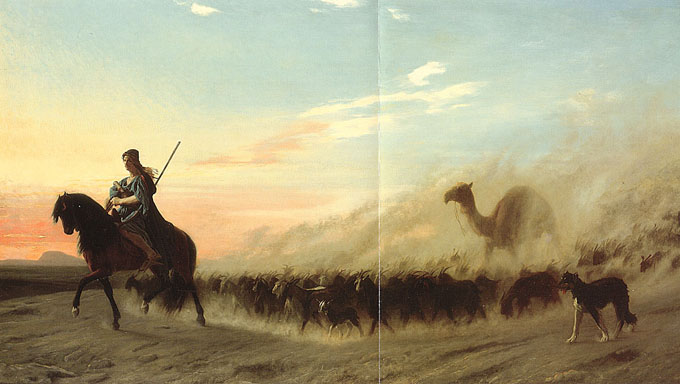

Gérôme's reputation was greatly enhanced at the Salon of 1857 by a collection of works of a more popular kind: the Duel: after the Masked Ball (Musée Condé, Chantilly), Egyptian Recruits Crossing the Desert, Memnon and Sesostris and Camels Watering, the drawing of which was criticized by Edmond About.

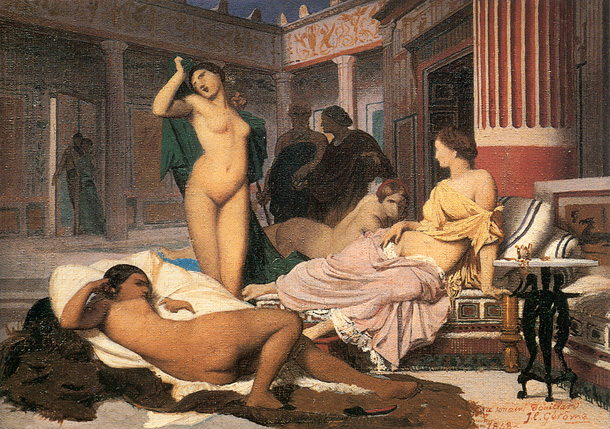

In 1858 he helped to decorate the Paris house of Prince Napoléon Joseph Charles Paul Bonaparte in the Pompeian style. The prince had bought his Greek Interior (1850), a depiction of a brothel also in the Pompeian manner.

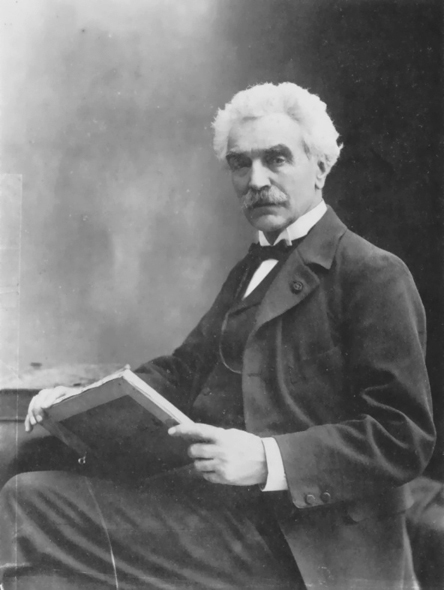

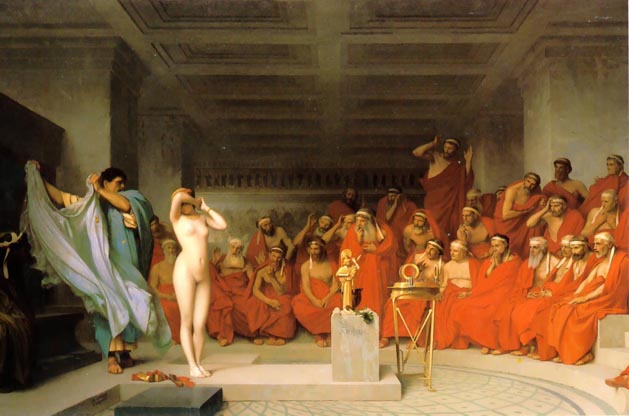

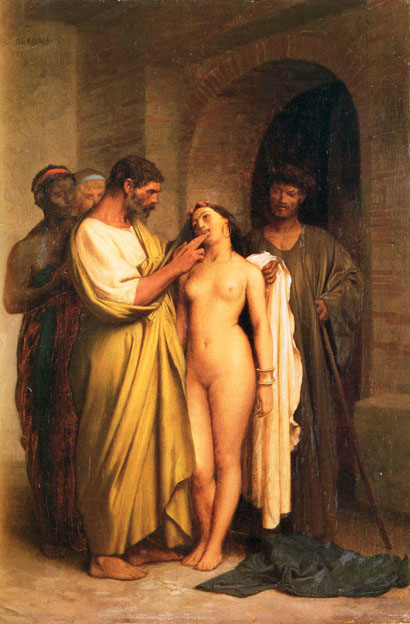

In Caesar (1859) Gérôme tried to return to a severer class of work, the painting of Classical subjects, but the picture failed to interest the public. Phryne before the Areopagus, King Candaules and Socrates finding Alcibiades in the House of Aspasia (1861) gave rise to some scandal by reason of the subjects selected by the painter, and brought down on him the bitter attacks of Paul de Saint-Victor and Maxime Du Camp. At the same Salon he exhibited the Egyptian Chopping Straw, and Rembrandt biting an Etching, two very minutely finished works.

He married Marie Goupil (1842-1912), the daughter of the international art dealer Adolphe Goupil. They had four daughters and one son. Upon his marriage he moved to a house in the Rue de Bruxelles, close to the music hall Folies Bergère. He expanded it into a grand house with stables and a sculpture studio below and a painting studio on the top floor.

Gérôme was elected, at the fifth attempt, a member of the Institut de France in 1865. Already a knight in the Légion d'honneur, he was promoted to an officer in 1867. In 1869 he was elected an honorary member of the British Royal Academy. The King of Prussia Wilhelm I awarded him the Grand Order of the Red Eagle, Third Class. His fame had become such that he was invited, along with the most eminent French artists, to the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869.

The theme of his Death of Caesar (1867) was repeated in his historical canvas Death of Marshall Ney, that was exhibited at the Salon of 1867, despite official pressure to withdraw it as it raised painful memories. He returned successfully to the Salon in 1874 with his painting Eminence grise (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston). In 1896 he painted Truth Rising from her Well, an attempt to describe the transparency of an illusion. He therefore welcomed the rise of photography as an alternative to his photographic painting. In 1902 he said "Thanks to photography, Truth has as last left her well".

Jean-Léon Gérôme died in his studio on 10 January 1904. He was found in front of a portrait of Rembrandt and close to his own painting "The Truth". At his own request, he was given a simple burial service, even without flowers. But the Requiem Mass given in his memory, was attended by a former president of the Republic, most prominent politicians and many painters and writers. He was buried in the Montmartre Cemetery in front of the statue Sorrow that he had cast for his son Jean, who had died in 1891.

He was the father-in-law of the painter Aimé Morot.

In 1853 Gérôme moved to the Boîte à Thé, a group of studios in the Rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs, Paris. This would become a meeting place for other artists, writers and actors. George Sand entertained in the small theatre of the studio the great artists of her time such as the composers Hector Berlioz, Johannes Brahms and Gioachino Rossini and the novelists Théophile Gautier and Ivan Turgenev. He started an independent studio at his house in the Rue de Bruxelles between 1860 and 1862.

He was appointed as one of the three professors at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. He started with sixteen students, most who had come over from his own studio. His influence became extensive and he was a regular guest of Empress Eugénie at the Imperial Court in Compiègne.

When he started to protest and show a public hostility to "decadent fashion" of Impressionism, his influence started to wane and he became unfashionable. But after the exhibition of Manet in the Ecole in 1884, he eventually admitted that "it was not so bad as I thought".

Several stories of how the Heraclid Dynasty of Candaules ended and the Mermnadae dynasty of Gyges began has been related by different authors throughout history, mostly in mythical tones. In Plato's Republic, Gyges used a magical ring to become invisible and usurp the throne, a plot device which reappeared in numerous myths and works of fiction throughout history, perhaps most famously in J.R.R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings saga. The earliest story, related by Herodotus in the fifth century BCE, has Candaules betrayed and executed by his wife in a cautionary tale against pride and possession.

According to The Histories of Herodotus, Candaules bragged of his wife's incredible beauty to his favorite bodyguard Gyges. "It appears you don't believe me when I tell you how lovely my wife is," said Candaules. "A man always believes his eyes better than his ears; so do as I tell you - contrive to see her naked."

Gyges refused; he did not wish to dishonor the Queen by seeing her nude body. He also feared what the King might do to him if he did accept.

Candaules was insistent, and Gyges had no choice but to obey. Candaules detailed a plan by which Gyges would hide behind a door in the royal bedroom to observe the Queen disrobing before bed. Gyges would then leave the room while the Queen's back was turned.

The next day, the Queen summoned Gyges to her chamber. Although Gyges thought nothing of the routine request, she confronted him immediately with her knowledge of his misdeed and her husband's. "One of you must die," she declared. "Either my husband, the author of this wicked plot; or you, who have outraged propriety by seeing me naked."

Gyges pleaded with the Queen not to force him to make this choice. She was relentless, and eventually he chose to betray the King so that he should live.

The Queen prepared for Gyges to kill Candaules by the same manner in which she was shamed. Gyges hid behind the door of the bedroom chamber with a knife provided by the Queen, and killed him in his sleep. Gyges married the Queen and became King, and father to the Mermnad Dynasty.

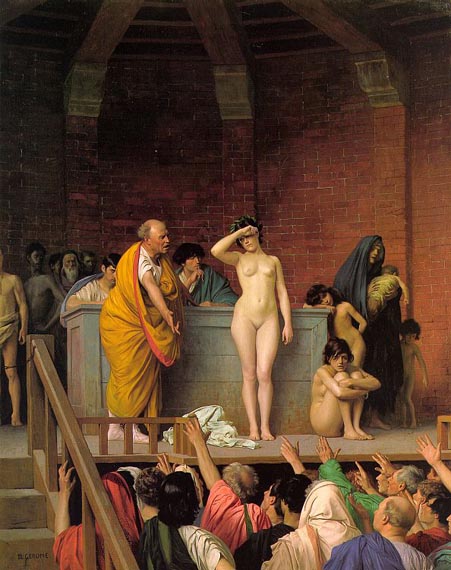

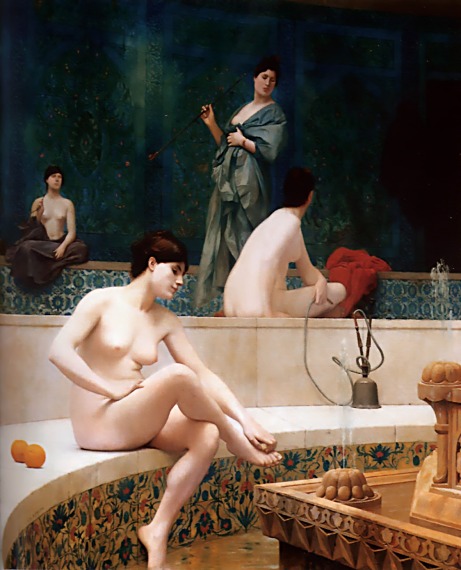

Aspasia was probably a hetaira. There is no English word to accurately translate hetairai, but they were more than courtesans. They were indeed sexual partners, but they were also companions, better educated than other Greek women. They were educated in philosophy, history, politics, science, art and literature, so that they could converse intelligently with sophisticated men. Aspasia was considered by many to be the most beautiful and intelligent of the city's hetairai.

Born in Ionian Greece, Aspasia was born a citizen of Miletus, but was either orphaned or unwanted. It is possible that her father offered her to the Temple of Aphrodite, an honorable way to get rid of unwanted female children, where they would serve Aphrodite with their bodies. Or she may have come to Athens as an orphan when Alcibiades returned from exile. In any event, she became a courtesan.

Aspasia entertained the most powerful men of Athens at her symposia (dinner parties). Though men openly attended such parties, wives did not. The women at these parties were hetairai. Aspasia's house became a fashionable place for the elite of Athens to go.

Pericles met Aspasia and immediately moved in with her. He may have divorced his wife to make this possible but in any event, they lived together as man and wife until Pericles died of the plague. The city's laws prevented marriage.

He lived with her as her husband and treated her as an equal. This was unseemly for a respectable man, and for a man of Pericles' standing, unheard of. He was often criticized for his relationship with Aspasia, and for his obvious reliance on her help and judgment. Women were not part of Athenian public life, and there was a place for hetairai, but it was in the bedroom and dining room, not in politics.

By all accounts Pericles loved Aspasia with a passion that brought him to openly flout such conventions. Plutarch (Life of Pericles) and Athenaeus (The Deipnosophistae), who later wrote about Pericles, commented that he was so smitten that he kissed her when he left in the morning and again when he returned at night. Apparently this was a very unusual practice.

They had a son together called Pericles, who because of their illegal relationship, could not be a citizen (later, after his legitimate sons had died in the plague, Pericles unsuccessfully made an emotional plea to the Assembly to grant citizenship status to his son - it was not until after his death that his wish was granted).

The gossip in Athens was always vicious, and Pericles and Aspasia were popular topics. They and their illegitimate son were ridiculed. She was called, among other things, a "dog-eyed whore." Many felt that Aspasia had too much influence on Pericles. Some accused her of persuading Pericles to go to war with Samos in order to help her native Miletus. Some even blamed her for the war with Sparta (the Peloponnesian War).

The busy tongues of Athens also called her a "Socratic." This was not a compliment. The Athenians did not like the funny looking little man who is often called the father of ethical philosophy. Socrates and Aspasia conversed often and probably influenced each other. Though Socrates did not write down his teachings, his students (the most famous was Plato) wrote Socratic dialogues which contained his teachings. She appears in one called Aspasia (by Aeschines of Sphettus), where she argues for more equality in marriage:

"If your neighbor had gold that was purer than yours," Aspasia asked Xenophon's wife, "would you rather have her gold or yours? "Hers," was the reply. "And if she had richer jewels and finer clothes?" "I would rather have hers." "And if she had a better husband than yours?" At the woman's embarrassed silence, Aspasia began to question the husband, asking him the same things, but substituting horses for gold and land for clothes and asking him finally if he would prefer his neighbor's wife if she were better than her own. At his embarrassed silence, reading their thoughts, she said, "Each of you would like the best husband or wife: and since neither of you has achieved perfection, each of you will always regret this ideal."

The comic poets were especially harsh. Aristophanes wrote that the war started over a dispute about prostitutes in The Acharnians the war:

When some drunken youths went for the whore, Simaetha, and stole her away, then the Megarians, garlicked with the pain, stole in return two whores of Aspasia. Then the start of the war burst out for all Hellenes because of three strumpets. Then Pericles, the Olympian, in his wrath thundered, lightened, threw Hellas into confusion.

She may also have been the model for the main character in the comedy Lysistrata. Lysistrata is the outspoken woman who leads the women of Athens to a creative solution to end the war - they simply denied the men their beds until they made peace.

"All the long time the war has lasted, we have endured in modest silence all you men did; you never allowed us to open our lips. We were far from satisfied, for we knew how things were going; often in our homes we would hear you discussing, upside down and inside out, some important turn of affairs. Then with sad hearts, but smiling lips, we would ask you: Well, in today's Assembly did they vote peace?-But, "Mind your own business!" the husband would growl, "Hold your tongue, please!" And we would say no more. …But presently I would come to know you had arrived at some fresh decision more fatally foolish than ever. "Ah! my dear man," I would say, "what madness next!" But he would only look at me askance and say: 'Just weave your web, please; else your cheeks will smart for hours. War is men's business!' "

Her influence was so great that Plato later joked that she had written Pericles' most famous speech, The Funeral Oration. Both Aspasia and Pericles were intellectually curious and on the cutting edge of philosophy, art, architecture and politics. They entertained intellectuals at their home. With her help and support Percales built magnificent public spaces such as the Parthenon. They lived together for nearly twenty years and ushered in the "golden age of Greece," that flowering of culture which continues to inspire us.

The relevant point being, that beautiful things need to be seen in the flesh.

Phryne is said to have modeled for Praxiteles and Apelles, and several Victorian artists took up the challenge of painting her. The most famous picture is Gérome's 'Phryné devant l'Aréopage' (1861, now in the Kunsthalle, Hamburg), in which our girl is shown covering her face at the very moment that her cloak is removed. This pose was heavily criticized, as it was felt that beauty on such a scale should transcend mere modesty. From what one knows of Phryne -- not really a shy girl -- this seems to be a fair criticism of the painting; from what one knows of 4th-Century Athens, large bribes probably came into the story somewhere.

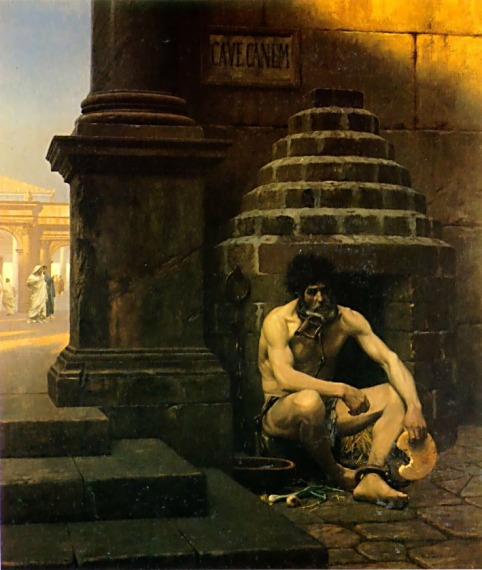

It is disputed whether Diogenes left anything in writing. If he did, the texts he composed have since been lost. In Cynicism, living and writing are two components of ethical practice, but Diogenes is much like Socrates and even Plato in his sentiments regarding the superiority of direct verbal interaction over the written account. Diogenes scolds Hegesias after he asks to be lent one of Diogenes’ writing tablets: “You are a simpleton, Hegesias; you do not choose painted figs, but real ones; and yet you pass over the true training and would apply yourself to written rules” (Diogenes Laertius, Lives of Eminent Philosophers, Book 6, Chapter 48). In reconstructing Diogenes’ ethical model, then, the life he lived is as much his philosophical work as any texts he may have composed.

ANACREONTIC SONG

As Sung at the Crown and Anchor Tavern in the Strand

1

To ANACREON in Heav'n, where he sat in full Glee,

A few Sons of Harmony sent a Petition,

That He their Inspirer and Patron wou'd be;

When this Answer arriv'd from the JOLLY OLD GRECIAN

"Voice, Fiddle, and Flute,

"No longer be mute,

"I'll lend you my Name and inspire you to boot,

"And, besides, I'll instruct you like me, to intwine

"The Myrtle of VENUS with BACCHUS's Vine.

2

The news through OLYMPUS immediately flew;

When OLD THUNDER pretended to give himself Airs

If these Mortals are suffer'd their Scheme to pursue,

The Devil a Goddess will stay above Stairs.

"Hark! already they cry,

"In Transports of Joy

"Away to the Sons of ANACREON we'll fly,

"And there, with good Fellows, we'll learn to intwine

"The Myrtle of VENUS with BACCHUS'S Vine.

3

"The YELLOW-HAIR'D GOD and his nine fusty Maids

"From HELICON'S Banks will incontinent flee,

"IDALIA will boast but of tenantless Shades,

"And the bi-forked Hill a mere Desart will be

"My Thunder, no fear on't,

"Shall soon do it's Errand,

"And, dam'me! I'll swinge the Ringleaders I warrant,

"I'll trim the young Dogs, for thus daring to twine

"The Myrtle of VENUS with BACCHUS'S Vine.

4

APOLLO rose up; and said, "Pr'ythee ne'er quarrel,

"Good King of the Gods with my Vot'ries below:

"Your Thunder is useless_then, shewing his Laurel,

Cry'd. "Sic evitabile fulmen, you know!

"Then over each Head

"My Laurels I'll spread

"So my Sons from your Crackers no Mischief shall dread,

"Whilst snug in their Club-Room, they Jovially twine

"The Myrtle of VENUS with BACCHUS'S Vine.

5

Next MOMUS got up, with his risible Phiz,

And swore with APOLLO he'd cheerfull join

"The full Tide of Harmony still shall be his,

"But the Song, and the Catch, & the Laugh shall bemine

"Then, JOVE, be not jealous

Of these honest Fellows,

Cry'd JOVE, "We relent, since the Truth you now tell us;

"And swear, by OLD STYX, that they long shall entwine

"The Myrtle of VENUS with BACCHUS'S Vine.

6

Ye Sons of ANACREON, then, join Hand in Hand;

Preserve Unanimity, Friendship, and Love!

'Tis your's to support what's so happily plann'd;

You've the Sanction of Gods, and the FIAT of JOVE.

While thus we agree

Our Toast let it be.

May our Club flourish happy, united and free!

And long may the Sons of ANACREON intwine

The Myrtle of VENUS with BACCHUS'S Vine.

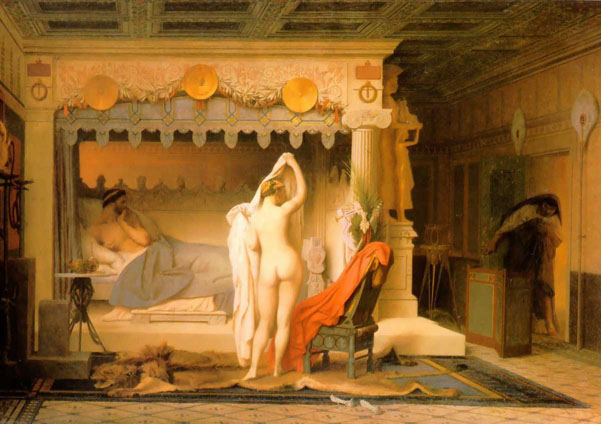

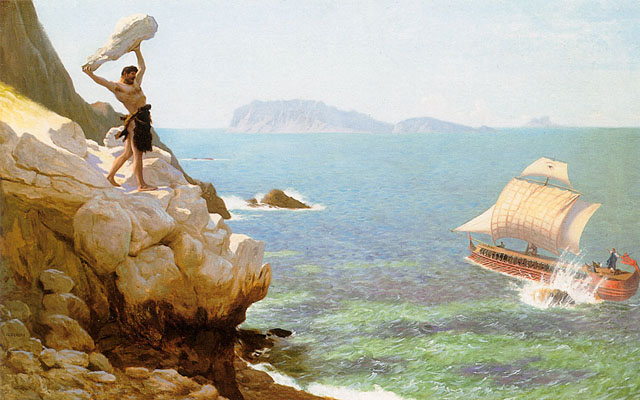

In the "Neo-Grec" style, characterized by a taste for meticulous finish, pale colours and smooth brushwork, Gérôme portrays a couple of near-naked adolescents at the foot of a fountain. Their youthfulness contrasts with the battered profile of the Sphinx in the background. The same opposition is found between the luxuriant vegetation and the dead branches on the ground, and in the fight between the two roosters, one of which is doomed to die.

In the chorus of praise for the work, few commentators noticed the artist's disillusioned attitude. Hardly anyone but Baudelaire criticized the canvas, calling Gérôme the leader of the "meticulous school", and finding him weak and artificial. The public preferred the opinion of Théophile Gautier who saw in The Cock Fight "wonders of drawing, action and color". At the age of twenty-three, Gérôme therefore made a brilliant entry into the art world and thereafter pursued the official career he had planned for himself, punctuated with honors and rewards.

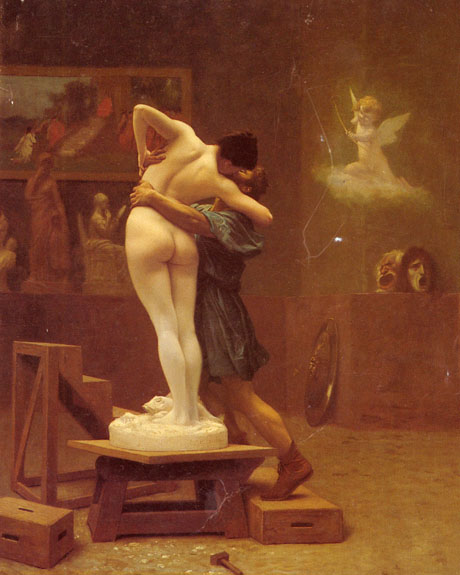

Gerome was a technical master (notice the very subtle vertical transformation of stone to flesh, right down to the skeletal flexibility), but this painting exceeds the technical requirements of good art. It is the emotion imbued in the work that presents the sweeping exhilaration of romantic love and makes Pygmalion and Galatea stand out.

Ovid's Metamorphosis: Pygmalion had seen them, spending their lives in wickedness, and, offended by the failings that nature gave the female heart, he lived as a bachelor, without a wife or partner for his bed. But, with wonderful skill, he carved a figure, brilliantly, out of snow-white ivory, no mortal woman, and fell in love with his own creation. He marvels: and passion, for this bodily image, consumes his heart. Often, he runs his hands over the work, tempted as to whether it is flesh or ivory, not admitting it to be ivory. he kisses it and thinks his kisses are returned; and speaks to it; and holds it, and imagines that his fingers press into the limbs, and is afraid lest bruises appear from the pressure. The day of Venus's festival came…when Pygmalion, having made his offering, stood by the altar, and said, shyly: "If you can grant all things, you gods, I wish as a bride to have…" and not daring to say "the girl of ivory" he said "one like my ivory girl." Golden Venus, for she herself was present at the festival, knew what the prayer meant, and as a sign of the gods' fondness for him, the flame flared three times, and shook its crown in the air. When he returned, he sought out the image of his girl, and leaning over the couch, kissed her. She felt warm: he pressed his lips to her again, and also touched her breast with his hand. The ivory yielded to his touch, and lost its hardness, altering under his fingers….The lover is stupefied, and joyful, but uncertain, and afraid he is wrong, reaffirms the fulfillment of his wishes, with his hand, again, and again.

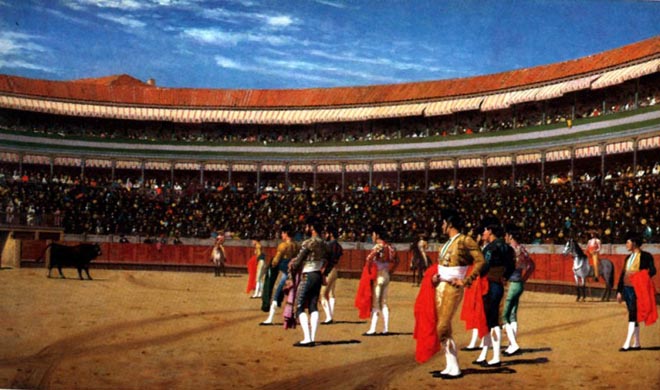

and the crowd for their judgment of the vanquished foe beneath

his foot.

The verdict? Thumbs Down!

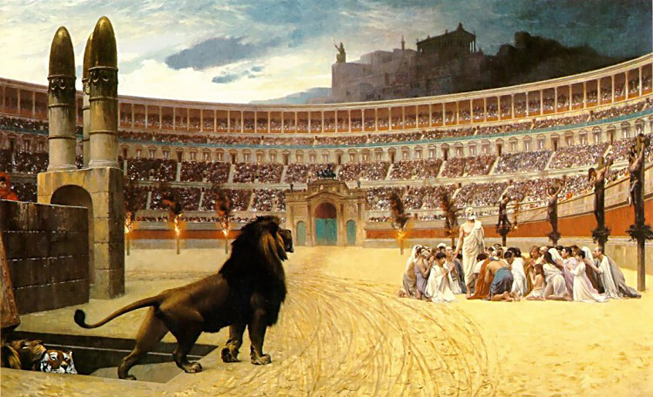

The Museum's unfinished painting is one of the two earlier versions referred to by Gérôme and gives insight into the artist's academic method. The visible grid lines were used to enlarge a smaller sketch accurately; they demonstrate the extent to which drawing formed the basis for his work. Thin layers of carefully applied paint establish compositional values. One can see that Gérôme originally painted the martyrs in the foreground, as the figures can faintly be seen. Gérôme painted over them and inserted the group farther back in the composition. This painting captures the dramatic moment at which the animals appear before the public. In the left foreground a fearsome lion emerges from a subterranean chamber, soon to be followed by another lion and a tiger. Christians of all ages huddle in prayer around a patriarchal figure. In the final version, other believers are bound to crosses and burned, a method of execution common during Nero's reign. An extremely influential painter and teacher in his day, Gérôme continued the traditions of academic realism into the late nineteenth century.

Meanwhile, the Senate was gathering at Pompey's theater, likely to grant Caesar one final and particularly anti-Republican honor: the title of king of all Roman territory outside of Italy. The conspirators plan was rather simple, they snuck in daggers, some in boxes intended for documents, others just concealed in flowing folds of their togas. When Caesar arrived all involved were expected to approach Caesar and stab him at least once each, thereby unifying the group and spreading the 'guilt' among them all. Gaius Trebonius was to keep Antony occupied in conversation outside the theater; to prevent him from helping Caesar, but some have speculated that Antony may even have been involved. The motivation definitely could've been there since at this time the contents of Caesar's will were unknown (the naming of Octavian as his heir) and it stood to reason that Antony (as one of Caesar's strongest supporters and right hand men) would be expected to inherit Caesar's vast fortune. However, Antony gained tremendously from following in the footsteps of Caesar, and his relentless support of the dictator makes this scenario unlikely.

Cassius Dio wrote that the conspirators had gladiators waiting nearby to control the violence and confusion that would certainly follow the assassination of Caesar, but this is unconfirmed. Judging things by the events after the murder, it seems that the conspirators had little or no plan to take control. Perhaps the all encompassing fear and anxiety of such a deed prevented clear focus on what would need to be done. Regardless, as time passed in the morning hours, it soon became evident that Caesar might not show at all. When word was delivered that this was indeed the case, the conspirators were likely on the verge of panic. This would simply be the only reasonable time when the plot could take place, and it was imperative that Caesar come to the Senate meeting. Decimus Brutus, Caesar's close friend and likely the least suspected member of the group, was dispatched to Caesar's home to convince him to come. He played on Caesar's dignity, mocking the priestly auspices that supposedly prevented Caesar from coming. He dismissed Calpurnia's dreams as silly, and appealed to Caesar's vanity by suggesting that the Senate was ready to vote him in as King. Certainly Caesar couldn't refuse the title that would assure him a guaranteed victory over the Parthians, as pre ordained by the Sybilline books. By 11 o' clock it seems that Caesar was convinced of the rightness of attending the meeting and set out with Decimus Brutus, despite his wife's pleas.

While the praetors Marcus Junius Brutus and Gaius Cassius Longinus (both important members of the plot) kept the Senate occupied by conducting state business during the morning hours, Caesar made his way towards Pompey's theatre. While he traveled in his litter, two meetings occurred that are likely as much a part of Caesar's legend as they are the truth. The first meeting was with a man, named Artemidorus by Plutarch, who approached Caesar's litter and handed him a scroll revealing the plot. Caesar, however, because of the great crowds that always approached him as he traveled the streets of Rome, was unable to read it. The second incident came with the soothsayer Spurinna who originally warned Caesar to beware the Ides. Upon seeing here, Caesar said "The Ides have come", as if suggesting that there was really nothing to fear. The reply was simple but eerie, "Aye Caesar, but not gone."

Caesar finally approached the Curia of Pompey and made his way inside. The Senators took their seats along with the conspirators, as if nothing was amiss. Trebonius kept Antony outside the meeting as planned, and Caesar took his place upon the gilded chair at the head of the forum. As was customary, Senators approached Caesar to petition him with various things, but this time, he was approached by 60 men bent on his death. With daggers concealed under their togas, they surrounded Caesar and waited for the signal that would send shockwaves rippling throughout the world.

Tillius Cimber was the man expected to deliver it. He petitioned Caesar to pardon his exiled brother, likely knowing full well that Caesar would refuse. When Caesar did so, the conspirators gathered more tightly around him, forcing Caesar to stand. Cimber then grabbed and pulled Caesar's purple robe from his shoulders, the signal to send the conspirators into action. Publius Servilius Casca, who positioned himself behind Caesar, was the first to strike the mark. He stabbed Caesar in the upper shoulder, near the neck, and Plutarch wrote that Caesar said, "Vile Casca" or Casca what is this? Reacting with the tenacity of a grizzled legionary veteran he apparently grabbed Casca's arm, stabbing it with his own writing pen, probably still completely unaware of the scope of the plot. At this point, the ferocity of the attack was revealed in earnest. The assassins stabbed Caesar relentlessly, each taking a shot at the dictator. The attack was so rapid and vicious that several conspirators wounded each other. Brutus, the great symbol of Republican virtue and freedom for tyranny was wounded in the hand by an errant dagger, as he himself stabbed Caesar in the groin. Though the line made famous by Shakespeare, "Et tu Brute" (translated as "You too Brutus", "You too my son", or "even you Brutus") was supposedly spoken by Caesar as he saw Brutus approach with dagger in hand, this is likely a complete dramatic fabrication. The ancient sources suggest that Caesar said nothing, and this seems most likely, considering the duress he was under. After the initial attack, though many say Caesar fought valiantly in his defense, he likely had little idea where all the shots were coming from.

Despite the overwhelming assault on him, Caesar still had the presence of mind to maintain his dignity for posterity purposed. Resigning himself to the assassination, Caesar pulled the folds of his toga over his head so as to prevent anyone seeing his face at death. In all, Caesar was stabbed 23 times, and inevitably collapsed. At the foot of the blood splattered statue of his old friend, rival and son-in-law, Pompey, Gaius Julius Caesar died at the age of 55, on March 15, 44 BC.

In 1852, Jean-Léon Gérôme received a state commission to paint a large mural of an allegorical subject of his choosing. In selecting this subject, Gérôme perhaps sought to flatter Emperor Napoleon III, whose government commissioned the painting and who was identified as a "new Augustus."

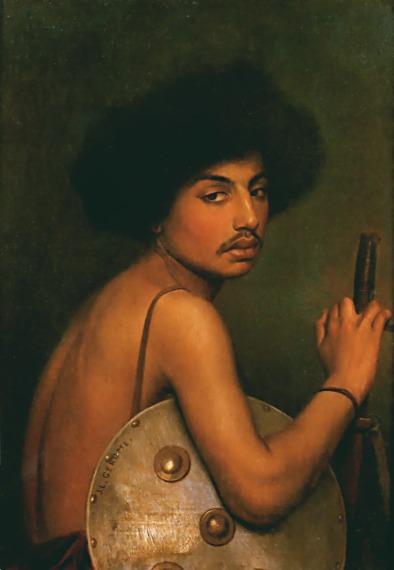

In preparation for his large mural, Gérôme traveled all over to find the appropriate ethnic types to portray the different peoples of the ancient world. When The Age of Augustus, The Birth of Christ was shown in 1855 at the Universal Exposition, his skill in depicting various nationalities led some to remark that Gérôme gave a lesson whenever he painted a picture.

Louis became king at the age of nine. Therefore, as a minor, France was governed by a Regent - in this case, his mother Marie de Medici. She allowed her favorites, Galigai and Concini, to do as they wished; thereby discrediting the monarchy after the exalted heights Henry IV had taken it to.

From 1614 on, Louis became more and more influenced by Charles, Duke de Luynes, who favored an extension of royal absolutism. Both Luynes and Louis were implicated in the murder of Concini and the concocted trial that found Galigai guilty of being a witch, a decision that lead to her execution. Once both former favorites were out of his way, Luynes used his position to expand his power, but also the power of Louis.

From 1617 on, France witnessed an expansion of monarchical power at the expense of the power of the magnates. Marie de Medici was exiled to a chateau at Blois and kept out of the royal court

. Louis had married at the age of 14. His wife was Anne of Austria, the Spanish Infanta. It was an arranged marriage (it had been settled as early as 1611 in the Treaty of Fontainbleau) and it was not a happy marriage. Louis and Anne spent years living apart, and the birth of their son, the future Louis XIV, surprised many but was the result of a rare night spent together. "It was probably out of a sense of duty to his kingdom."

Louis was a mass of contradictions. He came across as modest and reserved but he could be very cruel and ruthless - as the murder of Concini indicated. He was a very religious man who sanctioned murder. He was also a hypochondriac who always believed that he was ill yet he enjoyed leading his soldiers into battle.

Louis knew that he did not possess the ability to grasp the detail needed to run his kingdom well - hence his reliance on Luynes and Richelieu. However, both men were in favour of absolute monarchy and they formed a formidable team between 1617 and 1643; Luynes until his death in 1621 and Richelieu until the death of the king in 1643. The final decision on policy always rested with Louis.

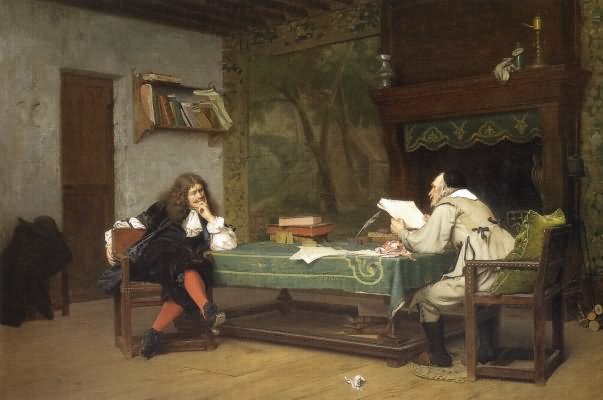

From a prosperous family and having studied at the Jesuit Clermont College (now Lycee Louis-le-Grand), Moliere was well suited to begin a life in the theatre. Thirteen years as an itinerant actor helped to polish his comic abilities while he also began writing, combining Commedia dell'Arte elements with the more refined French comedy.

Through the patronage of a few aristocrats including the brother of Louis XIV, Molière procured a command performance before the King at the Louvre. Performing a classic play by Pierre Corneille and a farce of his own, Le Docteur amoureux (The Doctor in Love), Molière was granted the use of Salle du Petit-Bourbon at the Louvre, a spacious room appointed for theatrical performances. Later, Molière was granted the use of the Palais-Royal. In both locations he found success among the Parisians with plays such as Les Précieuses ridicules (The Affected Ladies), L'École des maris (The School for Husbands) and L'École des femmes (The School for Wives). This royal favour brought a royal pension to his troupe and the title "Troupe du Roi" (The King's Troupe). Molière continued as the official author of court entertainments.

Though he received the adulation of the court and Parisians, Moliere's satires attracted criticisms from moralists and the Church. Tartuffe ou l'Imposteur (Tartuffe or the Hypocrite) and its attack on religious hypocrisy roundly received condemnations from the Church while Don Juan was banned from performance. Molière's hard work in so many theatrical capacities began to take its toll on his health and, by 1667, he was forced to take a break from the stage. In 1673, during a production of his final play, Le Malade imaginaire (The Imaginary Invalid), Moliere, who suffered from pulmonary tuberculosis, was seized by a coughing fit and a haemorrhage while playing the hypochondriac Argan. He finished the performance but collapsed again and died a few hours later. In his time in Paris, Molière had completely reformed French comedy.

Within a century of the prophet Muhammad's final revelation in the Qur'an, an Islamic state stretched from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to Central Asia in the east. This new polity soon broke into a civil war known to Islamic historians as the First Fitna, and later affected by a Second Fitna. Through its history, there would be rival dynasties claiming the caliphate, or leadership of the Muslim world, and many Islamic states and empires offered only token obedience to a caliph unable to unify the Islamic world.

Disclaimer: I include this site for fairness and to be as complete as possible. However, I do not have the time to verify its entire content; but there is sufficient information on the 'Net' that with careful research you can easily do that on your own.

In the 18th and 19th centuries A.D., Islamic regions fell under the sway of European imperial powers. Following World War I, the remnants of the Ottoman empire were parcelled out as European protectorates. Since then, no major widely-accepted claim to the caliphate (which had been last claimed by the Ottomans) remained.

When we talk of the Middle East today at least from a Western perspective, we are talking about an area that encompasses the modern countries of Egypt, Iraq, Turkey, Israel, Palestinian Authority, Lebanon, Jordan, Syria, and I would also include Iran as well. It has been a part of the world that has always held a certain mystique or mystery for most of us in the West. Yet, it is also a part of the world that has become a source of conflict and hostility and has become a modern 'Killing Field' especially since the end of World War II. I think it is foolish to deny that there isn't a cultural and religious bias on the part of the West that has moved us in that direction. There is also the old American or Western ideal of pure unadulterated greed that governs almost every governmental decision we see being made. The tragic reality in this part of the world is the 'Terrorists' who are responsible for such heinous crimes as 9/11 are never the ones who suffer from an intervention that never should have happened in the first place. There has been an entire life time of suffering and dislocation as well as dysfunction within the Arab World since 1945. It becomes an even more difficult issue to discuss when the question of Israel is introduced to the entire dilemma of the Middle East. The West first has to come to terms with the truth and reality that Israel was created by a UN Resolution in 1948 because of Anti-Semitism in nations such as the United States and Great Britain. These nations didn't want to open their doors to Jewish refugees at the end of World War II because of Anti-Semitic prejudice and bigotry that plagued both nations. Does Israel have a right to exist? Yes, of course it does and it is a reality that no one can deny. However, that same right is also shared by Palestine and there is a serious moral misjudgment when the West allows the Palestinians to become victims of the same prejudice and bigotry that Jews faced in the years after World War II. These are simple questions that should have simple answers. There needs to be a world created and forged for the future where Moslems, Jews, and Christians love their children more than they hate each other.

.jpg)

Source: Art Renewal Center

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.