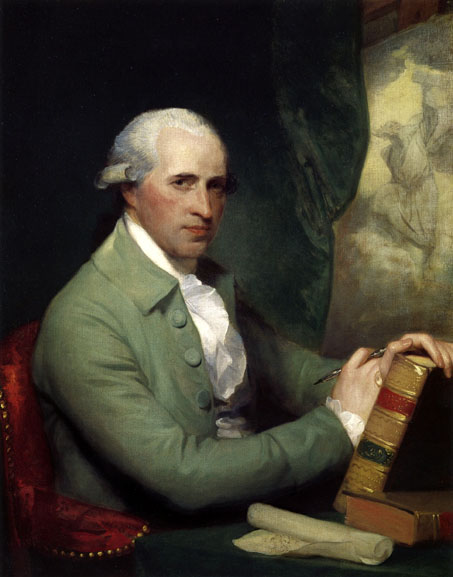

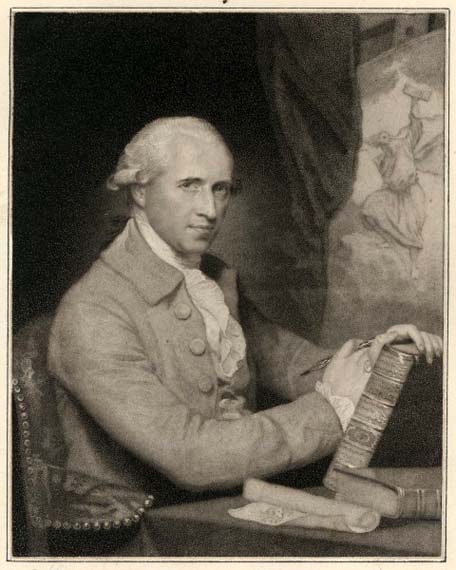

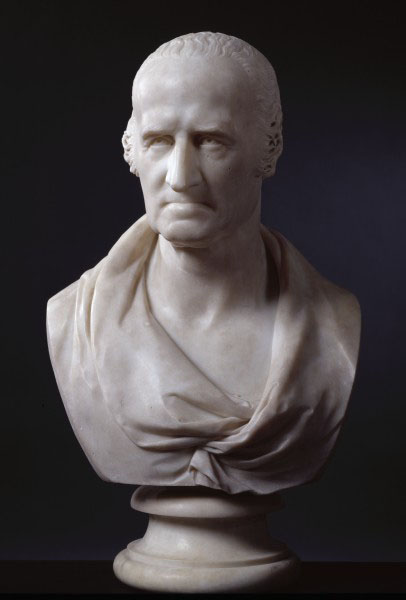

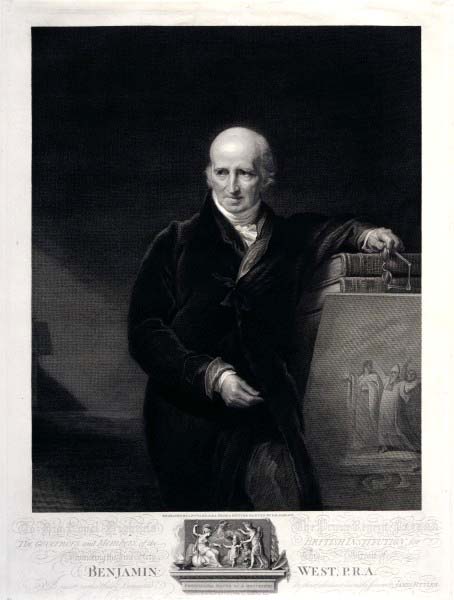

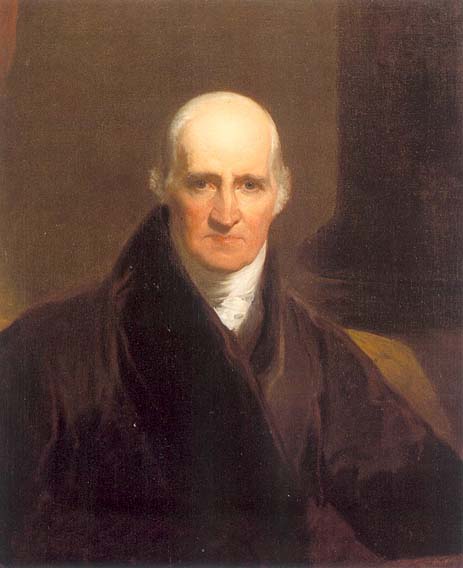

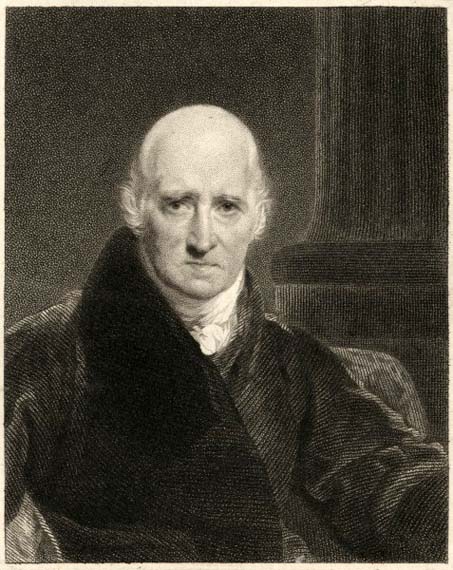

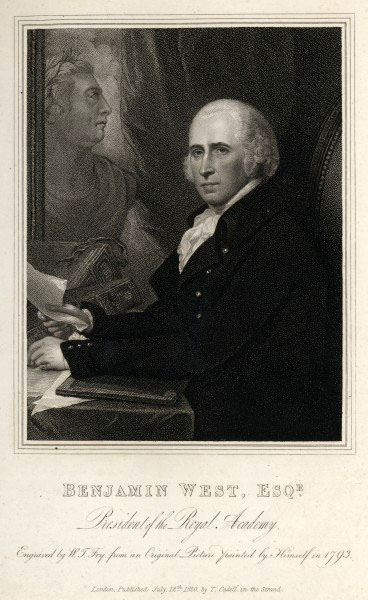

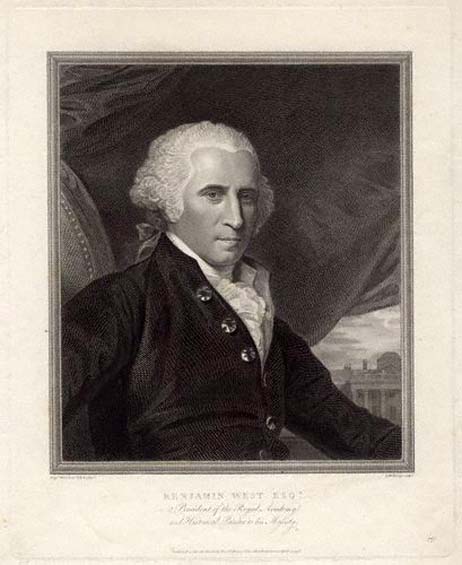

American Neoclassical Painter and Draftsman

1738 - 1820

One of the first American artists to win a wide reputation in Europe, Benjamin West exerted considerable influence on the development of art in the United States through such young American painters as Gilbert Stuart, Charles Willson Peale, and John Singleton Copley. West abandoned the tradition of painting people in Greek and Roman dress, the first major artist working in England to do so.

West was born on Oct. 10, 1738, of Quaker parents in Springfield (now Swarthmore) in the Pennsylvania colony. Young West was encouraged to draw, and it was said that he got his first paints from his Indian friends. When he was 16 his Quaker community approved art training for him. For a time West studied in Philadelphia and New York City. He also served as a militia captain in Indian campaigns in Pennsylvania. Then he went to Italy for three years of study. In 1763 he went to England and remained there for life.

Known in London as "the American Raphael," he became a friend of Sir Joshua Reynolds, England's leading painter. Soon other influential Londoners, Samuel Johnson for one, took an interest in the young American. King George III commissioned him to paint several pictures, and in 1772 he appointed West historical painter to the king with an annual allowance of 1,000 pounds. By another royal appointment West was made a charter member of the Royal Academy, succeeding Reynolds as president in 1792.

From: WebMuseum

Benjamin West was an Anglo-American painter of historical scenes around and after the time of the American War of Independence. He was the second president of the Royal Academy in London, serving from 1792 to 1805 and 1806 to 1820.

West was born in Springfield, Pennsylvania, in a house that is now in the borough of Swarthmore on the campus of Swarthmore College, as the tenth child of an innkeeper. The family later moved to Newtown Square, Pennsylvania, where his father was the proprietor of the Square Tavern, still standing in that town. West told John Galt, with whom, late in his life, he collaborated on a memoir, The Life and Studies of Benjamin West (1816, 1820) that, when he was a child, Native Americans showed him how to make paint by mixing some clay from the river bank with bear grease in a pot. Benjamin West was an autodidact (a person who has learned a subject without the benefit of a teacher or formal education); while excelling at the arts, "he had little (formal) education and, even when president of the Royal Academy, could scarcely spell".

From 1746 to 1759, West worked in Pennsylvania, mostly painting portraits. While in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, in 1756, West's patron, a gunsmith named William Henry, encouraged him to design a "Death of Socrates" based on an engraving in Charles Rollin's Ancient History; the resulting composition, which significantly differs from West's source, has been called "the most ambitious and interesting painting produced in colonial America." Dr William Smith, then the provost of the College of Philadelphia, saw the painting in Henry's house and decided to patronize West, offering him education and, more important, connections with wealthy and politically-connected Pennsylvanians. During this time West met John Wollaston, a famous painter who emigrated from London. West learned Wollaston's techniques for painting the shimmer of silk and satin, and also adopted some of "his mannerisms, the most prominent of which was to give all his subjects large almond-shaped eyes, which clients thought very chic".

In 1760, sponsored by Smith and William Allen, reputed to be the wealthiest man in Philadelphia, West traveled to Italy where he expanded his repertoire by copying the works of Italian painters such as Titian and Raphael.

West was a close friend of Benjamin Franklin, whose portrait he painted. Franklin was also the godfather of West's second son, Benjamin.

.jpg)

The kite being raised, a considerable time elapsed before there was any appearance of its being electrified. One very promising cloud had passed over it without any effect, when, at length, just as he was beginning to despair of his contrivance, he observed some loose threads of the hempen string to stand erect and to avoid one another, just as if they had been suspended on a common conductor. Struck with this promising appearance, he immediately presented his knuckle to the key, and (let the reader judge of the exquisite pleasure he must have felt at that very moment) the discovery was complete. He perceived a very evident electric spark. Others succeeded, even before the string was wet, so as to put the matter past all dispute, and when the rain had wet the string he collected electric fire very copiously. This happened in June 1752, a month after the electricians in France had verified the same theory, but before he heard of anything they had done."

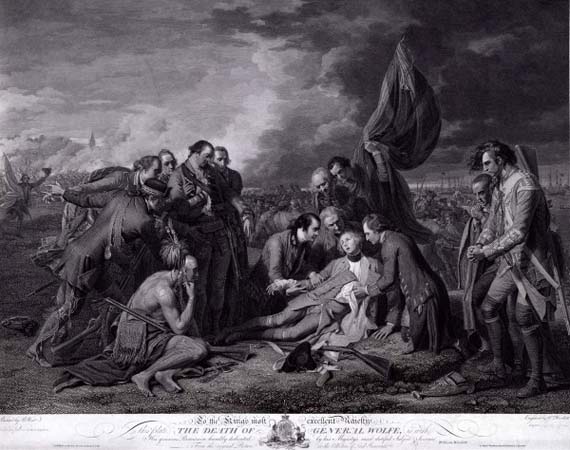

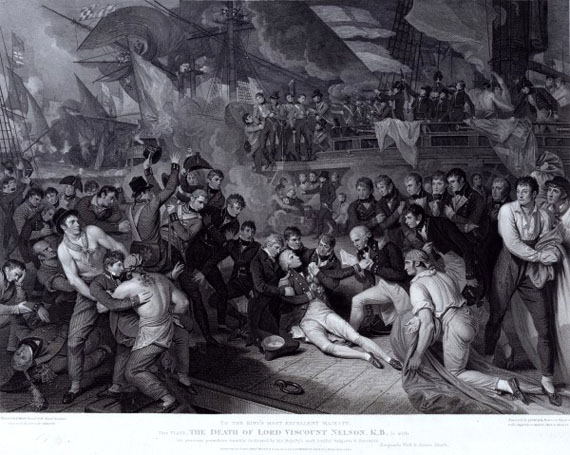

In 1763, West moved to England, where he was commissioned by King George III to create portraits of members of the royal family. The king himself was twice painted by him. He painted his most famous and possibly most influential painting, 'The Death of General Wolfe', in 1770, exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1771. Although originally snubbed by Sir Joshua Reynolds, the famous portrait painter and President of the Royal Academy, and others as over ambitious, the painting became one of the most frequently reproduced images of the period.

In 1772, King George appointed him historical painter to the court at an annual fee of £1,000. With Reynolds, West founded the Royal Academy of Arts in 1768. He was the second president of the Royal Academy from 1792 to 1805. He was re-elected in 1806 and was president until his death in 1820. He was Surveyor of the King's Pictures from 1791 until his death. Many American artists studied under him in London, including Charles Willson Peale, Rembrandt Peale, Gilbert Stuart, John Trumbull, and Thomas Sully.

West is known for his large scale history paintings, which use expressive figures, colors and compositional schemes to help the spectator to identify with the scene represented. West called this "epic representation".

He died in London.

Source: Wikipedia

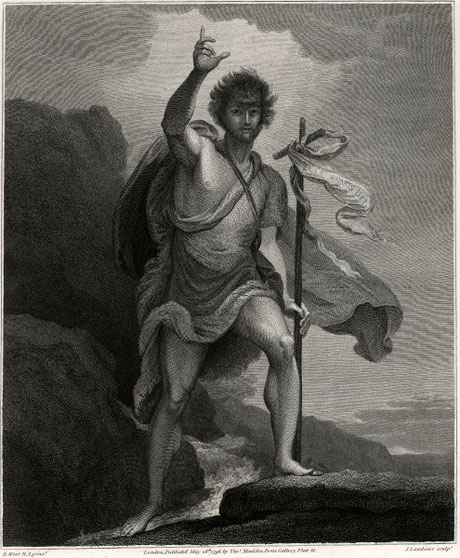

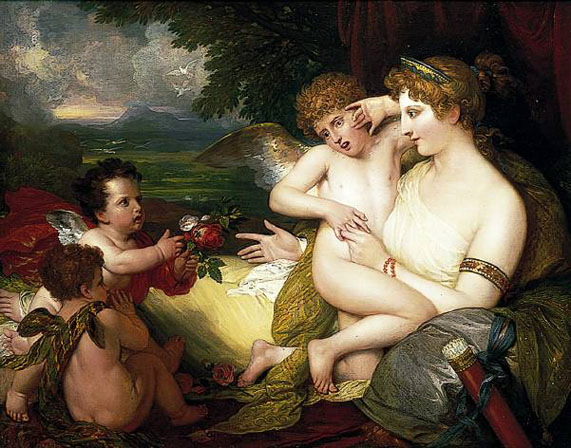

Bacchantes were the most important members of Bacchus' legendary retinue, the Thiasus. They were a popular subject in art dating from ancient Rome and Greece to the modern period. A Bacchante is often depicted semi-clothed in animal skins and vine leaves.

A Bacchante typically carries a thrysus, a staff made of giant fennel and topped with a pine cone, often wreathed in ivy. The thrysus was a sacred emblem of Bacchus, used in ceremonies and celebrations honoring the god. It symbolizes a union of forest: the pine cone, and farm: the fennel, and may also serve as a phallic symbol representing fertility.

The Bacchante is symbolic of both the ecstasy and the destructive power of the god she worships and his major attribute, wine. Though she sometimes appears in modern representations to be simply a free spirit, the Bacchante has a darker side. Bacchantes are possessed and act as if in a trance, completely abandoned to their physical natures. They are capable of ripping to shreds not only any animal that crosses their path, but humans as well, in a sacrificial rite known as sparagmos. Sometimes, the rite is followed by omophagia, in which Bacchantes eat the victim's remains.

_1831.jpg)

She married Aeneas, son of Anchises and Aphrodite, and bore him a son named Ascanius (Iulus).

After the fall of Troy, Aeneas fled with his father and son. He looked for Creusa, but she had gotten separated.

In the Aeneid, Aeneas tells Dido of his search for his wife, Creusa, after the siege of Troy.

Also, moreover, I, having dared to throw

voices through the shadow, filled up the

streets with a shout and, sad, I have called

Creusa repeating again and again in vain.

As I searched and rushed without end

among the roofs of the city, the unlucky

image of Creusa herself appeared before

the eyes for me and an image greater than

known.

I was stunned. Then she began to speak

and she took away my cares with these

words: "What does it help to indulge in

mad grief, O sweet husband? These things

didn't happen without the divine will of

the gods; it is neither the divine will for

you to carry your companion Creusa from

this place, nor does that ruler of proud

Olympus (Jupiter) allow it. [There will be]

long exiles for you, and the vast surface of

the sea must be plowed (by you) ... There

happy things and a kingdom and a

queenly wife await you. Repel your tears

for the beloved Creusa. I will not see the

proud seats of the Myrmidonian and

Dolopians, and I will not go to serve Greek

mothers, [I], descendant of Dardania, and

daughter-in-law of divine Venus.

"But the great mother of the gods detains

me on these shores: and now farewell and

save the love of our common son." When

she gave these words, she left [me] crying

and wishing to say many things, and she receded

into thin air.

There thrice having tried to surround her

neck with my arms: thrice in vain the

image, having been grasped, fled my

hands, equal to the light winds and very

like to a fleeting dream.

Although Creusa appears as a shade in the Aeneid, some say that she was not, in fact, dead, and had instead been detained alive by Aphrodite.

While Creusa plays a relatively minor role in the Aeneid, her son, Ascanius, was destined for greater things, and founded the Julian line when Aeneas reached Italy.

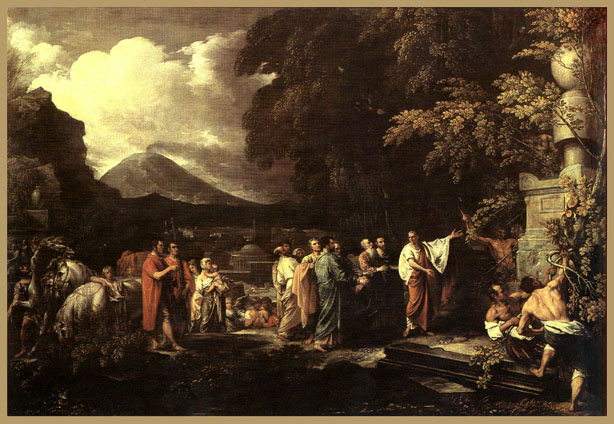

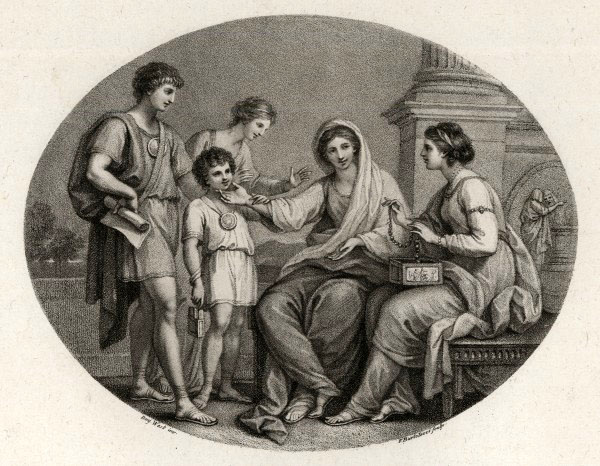

Agrippina subsequently plotted and planned for her son, Nero, to replace or succeed Tiberius as Emperor. She and two of her sons were then banished from Rome and were shortly thereafter executed on Tiberius' orders. Her third son, Gaius (identified in the painting as the smiling boy in the foreground) was to become the notoriously cruel Emperor Caligula.

This painting is a fine example of what has been called West's Stately Mode. It uses a monumental scale to elevate the subject from a sentimental episode to a moral statement. Agrippina can be regarded as a secularized Madonna - the religious overtones are deliberate as was made clear in a preliminary drawing which treats the subject as a variation on the Virgin and Child with the Infant Saint John.

This masterpiece shows the neo-classical influence that Italian art had exerted on West during his years in Rome. It was exhibited at the Royal Academy, London in 1773, the same year in which it was painted.

The painting is related to a previous painting, Agrippina Landing at Brundisium with the Ashes of Germanicus, which he had painted for King George III. The story of this military hero who died in the service of his country and the stoic grief of his wife who had accompanied him everywhere was seen as a noble example by the Enlightenment, as against the hedonism of the rococo.

West was active in England during the American Revolution and later during England's wars with Napoleon. He was an outspoken advocate of American liberty and in later years favored the French under Napoleon. After a visit to Paris in 1802, during which he met both Napoleon and David, he lost the favor and patronage of King George. He continued, however, to be both a popular and successful painter until his death in 1820.

John inherited the fortune and position of a country gentleman, but in politics was always opposed to the aristocratic party. In 1768 he successfully contested Hythe in opposition to this interest, and at once exerted himself in the House of Commons on behalf of Wilkes, who had been declared incapable of sitting for Middlesex. With Horne, Townshend, Oliver, and others, he helped to form the society known as the 'Supporters of the Bill of Rights'. In recognition of the assistance he had given to Wilkes, Sawbridge, who was a liveryman of the Framework Knitters' Company, was unanimously elected, with Townshend, as sheriff on Midsummer Day 1768, and in the following year (1 July) he was elected alderman for the ward of Langbourn. During his shrievalty he five times returned Wilkes as duly elected for Middlesex, in defiance of the house, and was threatened with a bill of pains and penalties from the government.

In August 1771 Junius, in a secret correspondence with Wilkes, urged him to procure Sawbridge's election as lord mayor on the ensuing Michaelmas day. Brass Crosby was reported to be desirous of re-election, and Wilkes, who had quarreled with Sawbridge, refused to desert Crosby. At the election the show of hands was declared in favor of Sawbridge and Crosby, but a poll was demanded for four other candidates, Bankes, Nash, Hallifax, and Townshend. In spite of Junius' appeals, the livery returned Nash and Sawbridge to the court of aldermen. The former, the 'ministerial candidate,' was elected.

Sawbridge obtained the mayoralty chair in Michaelmas 1775, the year following Wilkes's mayoralty. During his year of office by his severe denunciation of press warrants he succeeded in keeping press gangs out of the city. He was elected M.P. for London in 1774, and re-elected in 1780, 1784, and 1790. In April 1782 he strongly opposed the grant of a pension of £100 a year to Robinson, one of the secretaries of the treasury, and boldly charged Lord North with indolence and a share in the secretary's alleged misconduct in public office of funds. Wraxall describes his invectives against Lord North as coarse.

In May 1783 Sawbridge introduced a motion to shorten the duration of parliaments, and, although the motion failed, it was strongly supported by Pitt and other leaders of the house. Wraxall describes him as a stern republican in principles, almost hideous in aspect, of a coarse figure and still coarser manners, but possessing an ample fortune and a strong understanding. He was the greatest proficient at whist to be found among the clubs in St. James's Street, and since the death of Beckford, and with the exception of Crosby and Wilkes, no lord mayor had attained greater popularity. In the general election of July 1784 Sawbridge's attachment to Fox nearly lost him his seat for the city, which he retained only by seven votes. He was a magistrate of Kent, and for many years colonel of the East Kent regiment of militia.

He died on 21 February 1795 at his town residence in Gloucester Place, Portman Square, and was buried in the parish church of Wye. His will, dated 8 September 1791, was proved in the Prerogative Court of Canterbury 16 March 1795. He was possessed of several manors in Kent, some of which he inherited.

Sawbridge married, first, on 15 November 1763, Mary Diana, daughter of Sir Orlando Bridgeman, bart., who brought him a fortune of £100,000. On her death within a few months, he married, secondly, in June 1766, Anne, daughter of Alderman Sir William Stephenson. By his second wife he had three sons and one daughter.

This article was written by Charles Welch and was published in 1897

_1786.jpg)

Benjamin West's 'The Angel of the Resurrection' 1801, for example, generally considered to be 'the first lithograph of artistic merit ever done in any country', is noteworthy for its symbolic apposition of light and dark. Although clearly derived from an engraving technique, even today this pen drawing on stone has a bravura directness. In an interesting aside, Study of a tree 1802 by West's son, Raphael Lamar West, was included in the second series of Specimens of Polyautography (The act or practice of multiplying copies of one's own handwriting, or of manuscripts, by printing from stone, -- a species of lithography.), published in 1806 by G.J. Vollweiler, who had taken over the André presses the year before.

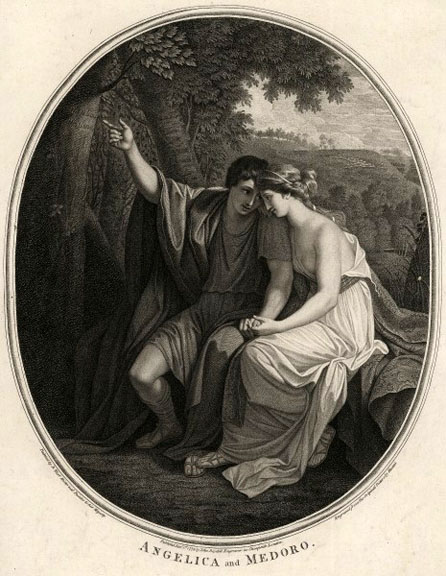

They were of a lowly stock on the coast of Syria, and in all the various fortunes of their lord had shown him a special attachment. Cloridan had been bred a huntsman, and was the more robust person of the two. Medoro was in the first bloom of youth, with a complexion rosy and fair, and a most pleasant as well as beautiful countenance. He had black eyes, and hair that ran into curls of gold; in short, looked like a very angel from heaven.

These two were keeping anxious watch upon the trenches of the defeated army, when Medoro, unable to cease thinking of the master who had been left dead on the field, told his friend that he could no longer delay to go and look for his dead body, and bury it. "You," said he, "will remain, and so be able to do justice to my memory, in case I fail."

Cloridan, though he delighted in this proof of his friend's noble-heartedness, did all he could to dissuade him from so perilous an enterprise; but Medoro, in the fervor of his gratitude for benefits conferred on him by his lord, was immovable in his determination to die or to succeed; and Cloridan, seeing this, determined to go with him.

They took their way accordingly out of the Saracen camp, and in a short time found themselves in that of the enemy. The Christians had been drinking over-night for joy at their victory, and were buried in wine and sleep. Cloridan halted a moment, and said in a whisper to his friend, "Do you see this? Ought I to lose such an opportunity of revenging our beloved master? Keep watch, and I will do it. Look about you, and listen on every side, while I make a passage for us among these sleepers with my sword."

Without waiting an answer, the vigorous huntsman pushed into the first tent before him. It contained, among other occupants, a certain Alpheus, a physician and caster of nativities, who had prophesied to himself a long life, and a death in the bosom of his family. Cloridan cautiously put the sword's point in his throat, and there was an end of his dreams. Four other sleepers were dispatched in like manner, without time given them to utter a syllable. After them went another, who had entrenched himself between two horses; then the luckless Grill, who had made himself a pillow of a barrel which he had emptied. He was dreaming of opening a second barrel, but, alas, was tapped himself. A Greek and a German followed, who had been playing late at dice; fortunate, if they had continued to do so a little longer; but they never counted a throw like this among their chances.

By this time the Saracen had grown ferocious with his bloody work, and went slaughtering along like a wild beast among sheep. Nor could Medoro keep his own sword unemployed; but he disdained to strike indiscriminately--he was choice in his victims. Among these was a certain Duke La Brett, who had his lady fast asleep in his arms. Shall I pity them? That will I not. Sweet was their fated hour, most happy their departure; for, embraced as the sword found them, even so, I believe, it dismissed them into the other world, loving and enfolded.

Two brothers were slain next, sons of the Count of Flanders, and newly-made valorous knights. Charlemagne had seen them turn red with slaughter in the field, and had augmented their coat of arms with his lilies, and promised them lands beside in Friesland. And he would have bestowed the lands, only Medoro forbade it.

The friends now discovered that they had approached the quarter in which the Paladins kept guard about their sovereign. They were afraid, therefore, to continue the slaughter any further; so they put up their swords, and picked their way cautiously through the rest of the camp into the field where the battle had taken place. There they experienced so much difficulty in the search for their master's body, in consequence of the horrible mixture of the corpses, that they might have searched till the perilous return of daylight, had not the moon, at the close of a prayer of Medoro's, sent forth its beams right on the spot where the king was lying. Medoro knew him by his cognizance, argent and gules. The poor youth burst into tears at the sight, weeping plentifully as he approached him, only he was obliged to let his tears flow without noise. Not that he cared for death--at that moment he would gladly have embraced it, so deep was his affection for his lord; but he was anxious not to be hindered in his pious office of consigning him to the earth. The two friends took up the dead king on their shoulders, and were hasting away with the beloved burden, when the whiteness of dawn began to appear, and with it, unfortunately, a troop of horsemen in the distance, right in their path.

It was Zerbino, prince of Scotland, with a party of horse. He was a warrior of extreme vigilance and activity, and was returning to the camp after having been occupied all night in pursuing such of the enemy as had not succeeded in getting into their entrenchments.

"My friend," exclaimed the huntsman, "we must even take to our heels. Two living people must not be sacrificed to one who is dead."

With these words he let go his share of the burden, taking for granted that the friend, whose life as well as his own he was thinking to secure, would do as he himself did. But attached as Cloridan had been to his master, Medoro was far more so. He accordingly received the whole burden on his shoulders. Cloridan meantime scoured away, as fast as feet could carry him, thinking his companion was at his side: otherwise he would sooner have died a hundred times over than have left him.

In the interim, the party of the Scottish prince had dispersed themselves about the plain, for the purpose of intercepting the two fugitives, whichever way they went; for they saw plainly they were enemies, by the alarm they showed.

There was an old forest at hand in those days, which, besides being thick and dark, was full of the most intricate cross-paths, and inhabited only by game. Into this Cloridan had plunged. Medoro, as well as he could, hastened after him; but hampered as he was with his burden, the more he sought the darkest and most intricate paths, the less advanced he found himself, especially as he had no acquaintance with the place.

On a sudden, Cloridan having arrived at a spot so quiet that he became aware of the silence, missed his beloved friend. "Great God!" He exclaimed, "What have I done? Left him I know not where, or how!" The swift runner instantly turned about, and, retracing his steps, came voluntarily back on the road to his own death. As he approached the scene where it was to take place, he began to hear the noise of men and horses; then he discerned voices threatening; then the voice of his unhappy friend; and at length he saw him, still bearing his load, in the midst of the whole troop of horsemen. The prince was commanding them to seize him. The poor youth, however, burdened as he was, rendered it no such easy matter; for he turned himself about like a wheel, and entrenched himself, now behind this tree and now behind that. Finding this would not do, he laid his beloved burden on the ground, and then strode hither and thither, over and round about it, parrying the horsemen's endeavors to take him prisoner. Never did poor hunted bear feel more conflicting emotions, when, surprised in her den, she stands over her offspring with uncertain heart, groaning with a mingled sound of tenderness and rage. Wrath bids her rush forward, and bury her nails in the flesh of their enemy; love melts her, and holds her back in the middle of her fury, to look upon those whom she bore.

Cloridan was in an agony of perplexity what to do. He longed to rush forth and die with his friend; he longed also still to do what he could, and not to let him die unavenged. He therefore halted awhile before he issued from the trees, and, putting an arrow to his bow, sent it well-aimed among the horsemen. A Scotsman fell dead from his saddle. The troop all turned to see whence the arrow came; and as they were raging and crying out, a second stuck in the throat of the loudest.

"This is not to be borne," cried the prince, pushing his horse towards Medoro; "you shall suffer for this." And so speaking, he thrust his hand into the golden locks of the youth, and dragged him violently backwards, intending to kill him; but when he looked on his beautiful face, he couldn't do it.

The youth betook himself to entreaty. "For God's sake, sir knight!" cried he, "be not so cruel as to deny me leave to bury my lord and master. He was a king. I ask nothing for myself--not even my life. I do not care for my life. I care for nothing but to bury my lord and master."

These words were spoken in a manner so earnest, that the good prince could feel nothing but pity; but a ruffian among the troop, losing sight even of respect for his lord, thrust his lance into the poor youth's bosom right over the prince's hand. Zerbino turned with indignation to smite him, but the villain, seeing what was coming, galloped off; and meanwhile Cloridan, thinking that his friend was slain, came leaping full of rage out of the wood, and laid about him with his sword in mortal desperation. Twenty swords were upon him in a moment; and perceiving life flowing out of him, he let himself fall down by the side of his friend.

The Scotsmen, supposing both the friends to be dead, now took their departure; and Medoro indeed would have been dead before long, he bled so profusely. But assistance of a very unusual sort was at hand.

A lady on a palfrey happened to be coming by, who observed signs of life in him, and was struck with his youth and beauty. She was attired with great simplicity, but her air was that of a person of high rank, and her beauty inexpressible. In short, it was the proud daughter of the lord of Cathay, Angelica herself. Finding that she could travel in safety and independence by means of the magic ring, her self-estimation had risen to such a height, that she disdained to stoop to the companionship of the greatest man living. She could not even call to mind that such lovers as the County Orlando or King Sacripant existed and it mortified her beyond measure to think of the affection she had entertained for Rinaldo.

"Such arrogance," thought Love, "is not to be endured." The little archer with the wings put an arrow to his bow, and stood waiting for her by the spot where Medoro lay.

Now, when the beauty beheld the youth lying half dead with his wounds, and yet, on accosting him, found that he lamented less for himself than for the unburied body of the king his master, she felt a tenderness unknown before creep into every particle of her being; and as the greatest ladies of India were accustomed to dress the wounds of their knights, she bethought her of a balsam which she had observed in coming along; and so, looking about for it, brought it back with her to the spot, together with a herdsman whom she had met on horseback in search of one of his stray cattle. The blood was ebbing so fast, that the poor youth was on the point of expiring; but Angelica bruised the plant between stones, and gathered the juice into her delicate hands, and restored his strength with infusing it into the wounds; so that, in a little while, he was able to get on the horse belonging to the herdsman, and be carried away to the man's cottage. He would not quit his lord's body, however, nor that of his friend, till he had seen them laid in the ground. He then went with the lady, and she took up her abode with him in the cottage, and attended him till he recovered, loving him more and more day by day; so that at length she fairly told him as much, and he loved her in turn; and the king's daughter married the lowly-born soldier.

O County Orlando! O King Sacripant! That renowned valor of yours, say, what has it availed you? That lofty honors, tell us, at what price is it rated? What is the reward ye have obtained for all your services? Show us a single courtesy which the lady ever vouchsafed, late or early, for all that you ever suffered in her behalf.

O King Agrican! If you could return to life, how hard would you think it to call to mind all the repulses she gave you--all the pride and aversion and contempt with which she received your advances! O Ferragus! O thousands of others too numerous to speak of, who performed thousands of exploits for this ungrateful one, what would you all think at beholding her in the arms of the courted boy!

Yes, Medoro had the first gathering of the kiss off the lips of Angelica--those lips never touched before--that garden of roses on the threshold of which nobody ever yet dared to venture. The love was headlong and irresistible; but the priest was called in to sanctify it; and the bride's woman of the daughter of Cathay was the wife of the cottager. The lovers remained upwards of a month in the cottage. Angelica could not bear her young husband out of her sight. She was forever gazing on him, and hanging on his neck. In-doors and out-of-doors, day as well as night, she had him at her side. In the morning or evening they wandered forth along the banks of some stream, or by the hedge-rows of some verdant meadow. In the middle of the day they took refuge from the heat in a grotto that seemed made for lovers; and wherever, in their wanderings, they found a tree fit to carve and write on, by the side of fount or river, or even a slab of rock soft enough for the purpose, there they were sure to leave their names on the bark or marble; so that, what with the inscriptions in-doors and out-of-doors (for the walls of the cottage displayed them also), a visitor of the place could not have turned his eye in any direction without seeing the words:

"ANGELICA AND MEDORO"

Written in as many different ways as true-lovers' knots could run.

Having thus awhile enjoyed themselves in the rustic solitude, the Queen of Cathay (for in the course of her adventures in Christendom she had succeeded to her father's crown) thought it time to return to her beautiful empire, and complete the triumph of love by crowning Medoro king of it. She took leave of the cottagers with a princely gift. The islanders of Ebuda had deprived her of everything valuable but a rich bracelet, which, for some strange, perhaps superstitious, reason, they left on her arm. This she took off, and made a present of it to the good couple for their hospitality; and so bade them farewell.

The bracelet was of inimitable workmanship, adorned with gems, and had been given by the enchantress Morgana to a favorite youth, who was rescued from her wiles by Orlando. The youth, in gratitude, bestowed it on his preserver; and the hero had humbly presented it to Angelica, who vouchsafed to accept it, not because of the giver, but for the rarity of the gift.

The happy bride and bridegroom, bidding farewell to France, proceeded by easy journeys, and crossed the mountains into Spain, where it was their intention to take ship for the Levant. Descending the Pyrenees, they discerned the ocean in the distance, and had now reached the coast, and were proceeding by the water-side along the high road to Barcelona, when they beheld a miserable-looking creature, a madman, all over mud and dirt, lying naked in the sands. He had buried himself half inside them for shelter from the sun; but having observed the lovers as they came along, he leaped out of his hole like a dog, and came raging against them.

But, before I proceed to relate who this madman was, I must return to the cottage which the two lovers had occupied, and recount what passed in it during the interval between their bidding it adieu and their arrival in this place.

From: Legends of Charlemagne or Romance of the Middle Ages by Thomas Bulfinch

_ca_1790_1795.jpg)

_ca_1805.jpg)

The myth of Belisarius as a blind beggar:

According to a story that seems to have developed during the Middle Ages, Justinian is said to have ordered Belisarius' eyes to be put out, and reduced him to the status of homeless beggar condemned to asking passers-by to "Give a Coin to Belisarius", before pardoning him. This account became a popular subject for painters in the 18th century, who saw parallels between the supposed actions of Justinian and the repression imposed by contemporary rulers. Belisarius was depicted as a kind of secular saint, sharing the suffering of the downtrodden poor. The most famous of these paintings, by Jacques-Louis David, combines the themes of charity (the alms giver), injustice (Belisarius), and the radical reversal of power (the soldier who recognizes his old commander). Others portray him being helped by the poor after his rejection by the powerful.

_1811.jpg)

Better known as the inventor of the electric telegraph, Samuel F. B. Morse was also a professor of painting and sculpture at New York University, which was founded in 1832. His appointment that year to the first such professorship in the United States represents a milestone in his mission to promote the fine arts as truly American.

Morse's reputation alternated between recognition and neglect throughout his artistic career. His training in England from 1811 to 1815 sparked his ambition to create a more nurturing environment for the fine arts in his native country. But the material realities of the American art scene, which lacked institutional support and private patronage, forced Morse to adapt his grandiose plans, and he soon resorted to portraiture as the only marketable genre. After working as an itinerant portraitist in New Hampshire and Vermont, he resided for a while in Charleston, South Carolina, and finally settled in New York City. His clients included not only local dignitaries but also eminent national figures such as President James Monroe.

For Morse, however, portrait painting exemplified America's materialism. Like Sir Joshua Reynolds, he considered history painting to be the most elevated genre of art. Following in the footsteps of his compatriots Benjamin West and John Trumbull, Morse modernized history painting for an American audience. His House of Representatives (1822-23; Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.), with its attention to contemporary costume and lack of a single dramatic moment, illustrates this approach. Set in the newly- renovated Hall of Congress, it includes individual portraits of dozens of congressmen, Supreme Court justices, journalists, and janitors, all participating in the orderly process of democratic government. Here, Morse was able to domesticate the grand ideal by fusing it with a more casual tone.

The Gallery of the Louvre (1832-33; Terra Museum of American Art, Chicago), begun the year Morse assumed his teaching post at NYU, best captures his educational agenda. It features an art teacher surrounded by students in the Louvre museum in Paris. In this self-contained ideal world, where students interact with works of art from various old-master traditions, Morse conceived the past in animated relation to the present.

In 1835 he moved into NYU's new University Building, constructed in the then-fashionable neo-Gothic style at Washington Square East-on the site of the current Silver Center, the home of the Grey Art Gallery. He took the northwest tower as his studio, as well as six other rooms for himself and his students, who received both theoretical and practical instruction. As an unpaid faculty member, Morse collected fees for instruction directly from his students and was responsible for their welfare. But, greatly disappointed by his failure to secure a commission to paint a mural in the Capitol Rotunda in Washington, D.C., Morse soon drew back from the arts and turned his attention to the telegraph and to his groundbreaking research in photography, conducted in collaboration with NYU Professor of Chemistry John Draper. Although he no longer taught after 1841, Morse continued to be listed as Professor of the Literature of the Arts of Design until just before his death in 1872.

Morse never realized his dream of developing a truly American public art, one that educated the populace to new heights of artistic awareness while fostering enthusiasm for a distinctly American heritage. Yet the founding of the National Academy of Design, over which he presided from 1826 to 1842, and his presentation there, first in 1826, then in 1828-29 and 1831-32, of the first educational art lectures in America (published as Lectures on the Affinity of Painting with the Other Fine Arts) were significant steps in the encouragement of the arts in America. And his paintings remain as records of his progressive contribution to the American art scene. His idealistic vision of the role of art education in developing America as a preeminent cultural force is best embodied in the Allegorical Landscape of New York University (1835-36; New-York Historical Society, New York). Here Morse transposes NYU's University Building from Washington Square to a timeless classical landscape inspired by the work of the seventeenth-century French master Claude Lorrain. Such a struggle to fuse old and new characterizes all of Morse's involvements in American cultural life.

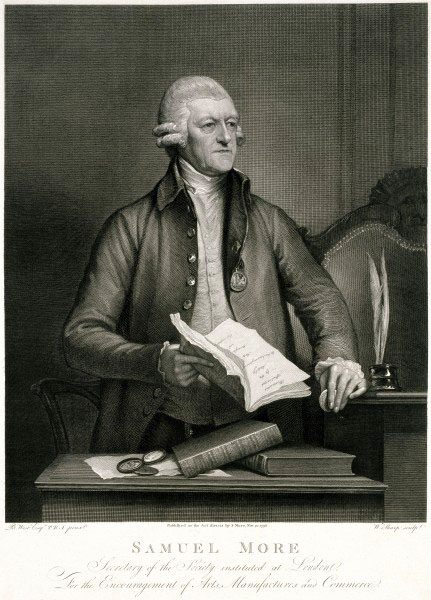

Holloway was apprenticed to a seal engraver named Stent at a young age. He went on to study engraving at the Royal Academy beginning in 1773, during which time he resided at 11 Beaches Row, near Charles Square, Hoxton, and exhibited pastel portraits at the Society of Artists in 1777. He later lived in Orme House in Hampton, Edgefield, Norfolk, and Coltishall, Norfolk. He became a court engraver in 1792 and is noted for his arduous engravings of cartoons by Raphael at Windsor Castle in 1800, on which he worked for 30 years.

Holloway was a Baptist, and at one point lectured on his brother's behalf on the theory of animal magnetism. He died unmarried.

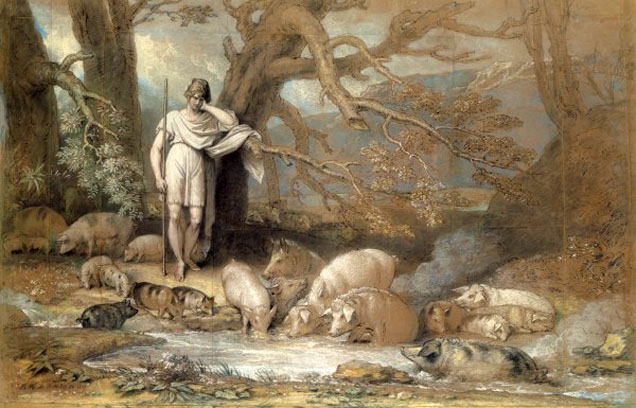

The story of Bladud and the pigs was particularly popular during the eighteenth century, although by this stage it was not necessarily considered to be historically correct as the Roman origins of Bath were known. These stories would therefore have been current in Bath when Benjamin West made an extended visit to the city with his wife between July and November 1807. This drawing is inscribed 'Bath 20 Sept 1807' indicating that West decided on this subject and certainly started working on it while he was still in Bath. The subject matter is particularly appropriate given that the reason for the artist's visit to the ancient city was in the hope of an improvement in his wife's health.

_1767_1769.jpg)

_1824.jpg)

The letter assured him:

"The works of an artist which ornament the palace of his King cannot fail to honor him in his native land."

West's response was positive and he wrote:

"The subject I have chosen is analogous to the situation. It is the Redeemer of mankind extending his aid to the afflicted of all ranks and condition."

"Christ Healing the Sick in the Temple" was completed and exhibited in 1811. It excited such interest in England, however, that officers of the British Institution pressured West to sell it as the first work to be hung in a proposed National Gallery. It was purchased for 3,000 guineas, the largest sum ever paid for a modern work.

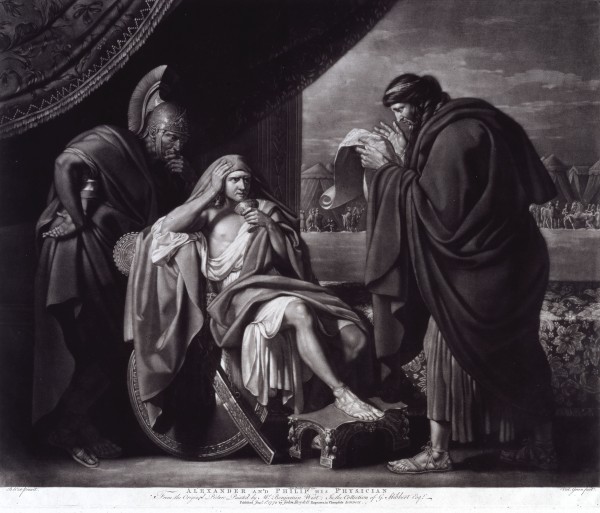

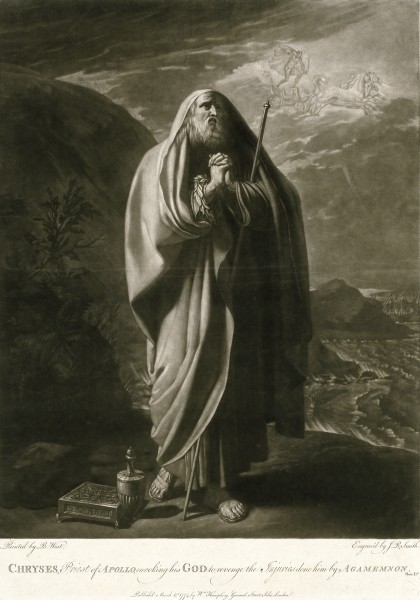

In the tenth year of the Trojan War, Agamemnon captured Chryseis, daughter of Chryses, a priest of Apollo, and intended to keep the girl as a prize, take her home, and turn her into both a slave and a concubine. Chryses, a loving father if compared to the king, came then to see Agamemnon and, having blessed the whole army, offered a generous ransom for her daughter's freedom. The troops applauded the priest, but Agamemnon was not a man inclined to let his will be curbed. So he denied Chryses' request and, in an arrogant display of authority, threatened the old man, who left the Achaean camp humiliated.

Apollo's Wrath

The best time to address the gods is when humans refuse to listen, so Chryses prayed to Apollo as soon as he found himself alone. He asked the god to let the Achaeans pay through his golden arrows the tears he was shedding. That is why Apollo, who otherwise is known as the bright one, on hearing the prayer and learning the outrage his priest had suffered, came down from Olympus, as they say, darker than night, letting his arrows rain on the Achaean camp, which means that an epidemic spread in the army, taking many lives.

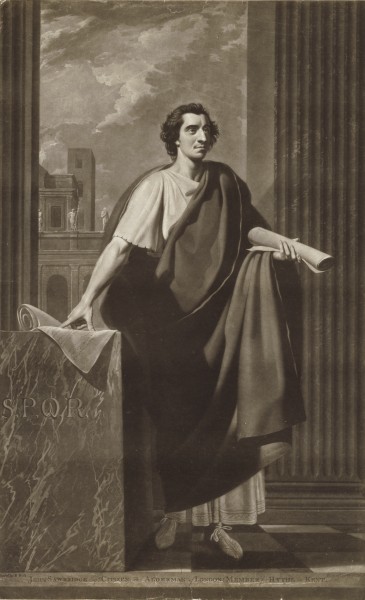

Thomas Provis and his daughter Ann, a miniaturist, had convinced West and a number of high-profile Royal Academicians that the manuscript was genuine, persuading them to pay a subscription to see it. The hoax was exposed shortly after West exhibited Cicero Discovering the Tomb of Archimedes, and his second version of the same scene, painted in 1804, can be seen as an 'atonement' painting. West was particularly susceptible to this scam because the coloring of his work had often been criticized.

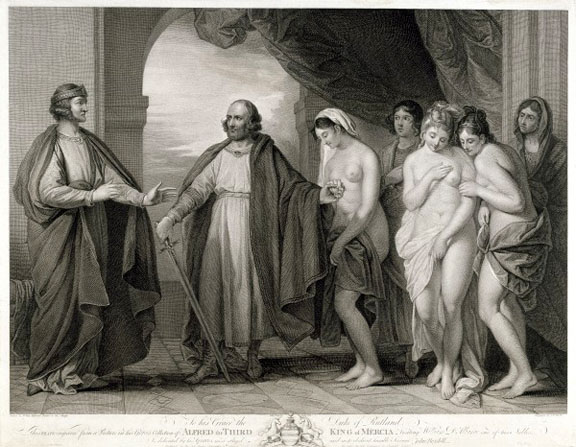

His subject is an incident from ancient Greek history. Leonidas, King of Sparta, was usurped by his son-in-law, Cleombrutus. When Leonidas returns looking for revenge, his daughter pleads for her husband's life. Leonidas is moved by her tears, and commutes Cleombrutus's death sentence to banishment.

Plutarch wrote that: "after the death of Scipio who overthrew Hannibal, (Tiberius Sempronius) was thought worthy to match with his daughter Cornelia, though there had been no friendship or familiarity between Scipio and him, but rather the contrary."

Cornelia bore 12 children, however only three lived to adulthood, the famous brothers Tiberius and Caius, who died championing the rights of the common people, and daughter Sempronia, wife of Scipio Aemilianus (Scipio the Younger) the destroyer of Carthage.

After the death of her husband Tiberius in 154 BCE: "Cornelia, taking upon herself all the care of the household and the education of her children, approved herself so discreet a matron, so affectionate a mother, and so constant and noble-spirited a widow, that Tiberius seemed to all men to have done nothing unreasonable in choosing to die for such a woman; who, when King Ptolemy himself proffered her his crown, and would have married her, refused it, and chose rather to live a widow."

Cornelia reared Tiberius, Caius and Sempronia" with such care that though they were without dispute in natural endowments and dispositions the first among the Romans of their time, yet they seemed to owe their virtues even more to their education than to their birth."

Cornelia is credited with inspiring her children towards civic duty, and ensuring that they obtained the education necessary to accomplish great deeds. As the attitudes towards the agrarian democratic reforms proposed by her sons ranged from outrage to admiration, so too does opinion towards Cornelia, as to whether she motivated her sons action, or sought to temper their brashness.

Plutarch continues, "Some have also charged Cornelia, the mother of Tiberius, with contributing towards it, because she frequently upbraided her sons, that the Romans as yet rather called her the daughter of Scipio, than the mother of the Gracchi."

Cornelia lived in a period of political turmoil, of which her family was often the center. Clearly Cornelia exercised political influence. Her son Caius "proposed two laws. The first was, that whoever was turned out of any public office by the people, should be thereby rendered incapable of bearing any office afterwards; the second, that if any magistrate condemn a Roman to be banished without a legal trial, the people be authorized to take cognizance thereof.

One of these laws was manifestly leveled at Marcus Octavius, who, at the instigation of Tiberius, had been deprived of his tribuneship. The other touched Popilius, who, in his praetorship, had banished all Tiberius's friends; whereupon Popilius, being unwilling to stand the hazard of a trial, fled out of Italy. As for the former law, it was withdrawn by Caius himself, who said he yielded in the case of Octavius, at the request of his mother Cornelia."

The Roman citizenry "had a great veneration for Cornelia, not more for the sake of her father than for that of her children; and they afterwards erected a statue of brass in honor of her, with this inscription, Cornelia, the mother of the Gracchi."

Plutarch ends his Life of Caius Gracchus with an eloquent description of Cornelia:

"It is reported that as Cornelia, their mother, bore the loss of her two sons with a noble and undaunted spirit, so, in reference to the holy places in which they were slain, she said, their dead bodies were well worthy of such sepulchers.

"She removed afterwards, and dwelt near the place called Misenum, not at all altering her former way of living. She had many friends, and hospitably received many strangers at her house; many Greeks and learned men were continually about her; nor was there any foreign prince but received gifts from her and presented her again.

"Those who were conversant with her were much interested, when she pleased to entertain them with her recollections of her father Scipio Africanus, and of his habits and way of living.

"But it was most admirable to hear her make mention of her sons, without any tears or sign of grief, and give the full account of all their deeds and misfortunes, as if she had been relating the history of some ancient heroes. This made some imagine, that age, or the greatness of her afflictions, had made her senseless and devoid of natural feelings.

"But they who so thought were themselves more truly insensible not to see how much a noble nature and education avail to conquer any affliction; and though fortune may often be more successful, and may defeat the efforts of virtue to avert misfortunes, it cannot, when we incur them, prevent our hearing them reasonably."

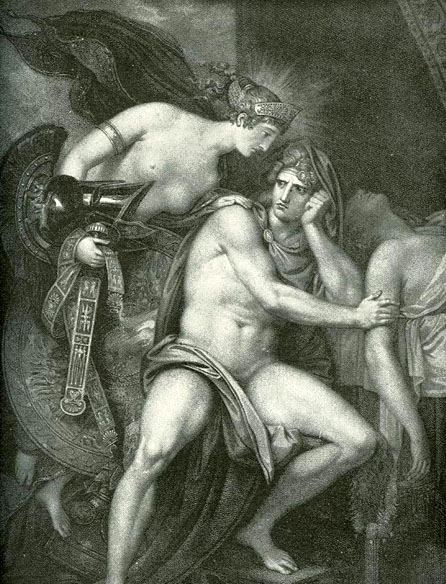

However, the subject that West chose is one of the less commonly represented episodes of the story of Cupid and Psyche in 'The Golden Ass'. Psyche, who has fainted after opening the vase she was given in Hades by Proserpina and commanded by Venus not to open, is revived by Cupid's kiss.

With honied words, around his form

With fond devotion now she twines,

With rapt'rous kisses pressed and warm

Each soothing, witching art combines.

Forgetting his celestial race

Unconscious of his own misdeeds

He yields to her resistless grace

Who can resist when woman pleads?

West's treatment of Cupid and Psyche follows that found in several other well-known works from the period, in particular that by François Gérard of 1798 and Antonio Canova's sculptural group of 1793 (both Louvre, Paris). The emphatic profiles of both Cupid and Psyche in the present work suggest a lingering influence of the French Neoclassical paintings that West had seen on a visit to Paris in 1802.

_1755_1756.jpg)

A series of eight paintings illustrating events from the reign of Edward III was commissioned from West by George III to decorate the Audience Chamber at Windsor Castle. The task took three years to complete from 1786 to 1789, but the arrangement was dismantled by George IV during the mid-1820's when much of Windsor Castle was redesigned by Jeffry Wyatville. However, a view of the Audience Chamber with the pictures still in place is included in W. H. Pyne's 'The History of the Royal Residences of 1819'. The present painting was double-hung on the left of the throne balancing 'The Burghers of Calais' on the right, positioned above the door.

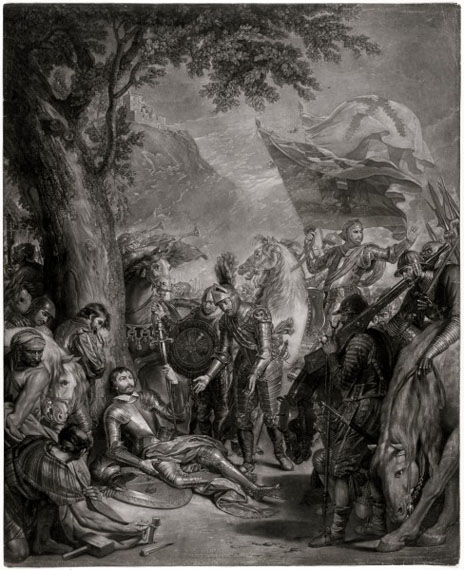

The series illustrates Edward III's campaign in northern France during the summer of 1346. Edward III crossing the Somme is the first in the sequence and shows an incident preceding the Battle of Crécy, when the king was trying to cross the River Somme at Blanche Tache, near Abbeville, in order to escape the French army. Edward III encountered and engaged a part of the French force under Godemar de Faye, the outcome of which, like the Battle of Crécy itself, was dependent upon the skill of the English archers seen in the upper right of the composition. The king is on horseback just to the right of centre and the figures accompanying him can be identified with the aid of a key provided by the artist for George III. An oil sketch of the composition is in the Santa Barbara Museum of Art, California.

A subject taken from medieval history was an unusual choice for this date. According to West's earliest biographer, John Galt, it was George III who, 'recollecting that Windsor Castle had, in its present form, been created by Edward the Third, said, that he thought the achievements of his splendid reign were well calculated for pictures, and would prove very suitable ornaments to the halls and chambers of that venerable edifice.' In addition to his military prowess, Edward III had also been the founder of the 'Order of the Garter' that is so closely associated with Windsor Castle. The paintings by West must be seen, therefore, as part of a revival of interest in the Middle Ages that was being pioneered by antiquarians such as Joseph Struttz and Francis Grose, to whose works the artist clearly referred for details of the arms, armor, and dress. For the historical narrative the primary sources in English were an early translation of the Chronicles (1325-1400) of Jean Froissart and the 'History of England' (1754-62) by David Hume. West's work showed that ideal truth could be sought in themes unrelated to antiquity, and his lively treatment of such subject matter reveals his innovative qualities as an artist.

Elizabeth, daughter of Peter Beckford, was first married to Thomas Howard, 2nd Earl of Effingham, and then George Howard.

Leeds was a Member of Parliament for Eye in 1774 and for Helston from 1774 to 1775; in 1776 having received a writ of acceleration as Baron Osborne, he entered the House of Lords, and in 1777 Lord Chamberlain of the Queen's Household. In the House of Lords he was prominent as a determined foe of the Prime Minister, Lord North, who, after he had resigned his position as chamberlain, deprived him of the office of Lord Lieutenant of the East Riding of Yorkshire in 1780. He regained this, however, two years later.

Early in 1783 Leeds was selected as ambassador to France, but he did not take up this appointment, becoming instead Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs under William Pitt the Younger in December of the same year. As secretary he was little more than a cipher, and he left office in April 1791. Subsequently he took little part in politics.

Leeds married firstly Lady Amelia, daughter of Robert Darcy, 4th Earl of Holderness, who became Baroness Conyers in her own right in 1778, in 1773. They were divorced in 1779. He married secondly Catherine, daughter of Thomas Anguish, in 1788. There were children from both marriages. Leeds died in London in January 1799, aged 48, and was succeeded in the dukedom by his eldest son from his first marriage, George. His second son from his first marriage, Lord Francis Osborne, was created Baron Godolphin in 1832. The Duchess of Leeds died in October 1837, aged 73. Leeds's Political Memoranda were edited by Oscar Browning for the Camden Society in 1884, and there are eight volumes of his official correspondence in the British Museum.

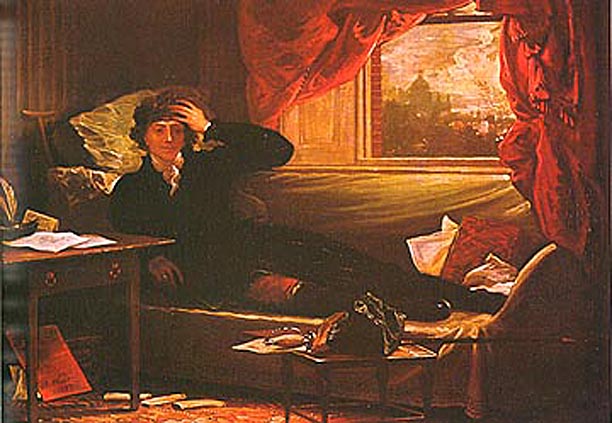

The drawing's provenance is unusual. West dedicated this work to the Polish patriot Thaddeus Kosciuszko during the Pole's brief visit to London in June 1797 after his release from a Russian prison. They met on June 7, and Kosciuszko received the drawing three days later. By December he had moved to Philadelphia, where he became close friends with then-Vice President Thomas Jefferson. Kosciuszko later presented the drawing to Jefferson, who kept it at his home Monticello.

The Polish general and patriot Thaddeus Kosciusko (Tadeusz Kosciuszko, 1746-1817) was one of many foreign officers who served in the American Revolutionary War. He was also a leader in his own country's valiant but doomed fight for independence from Russian domination during the early 1790's. Kosciusko was wounded in battle at Maciejowice in 1794 and taken to Russia as a prisoner. Upon the death of Catherine II and ascension of Paul I as czar in 1796, he was released and--still recovering from wounds received two years earlier--traveled to America via Sweden and London. Kosciusko and an entourage of Polish officers arrived in London in late May 1797, and stayed for a few weeks before sailing for Philadelphia on 19 June. During this time the noted general received visits from many prominent citizens, including Benjamin West.

West's visit on 7 June was described by the English landscape painter and diarist Joseph Farington in his journal entry for 8 June 1797: "West saw General Koscioscou yesterday. He went with Dr. Bancroft and Trumbull.--The General was laid on a couch--had a black silk band round his head and was drawing Landscapes, which is his principal amusement. He speaks English, appears to be about 45 years of age; and about 5 feet 8 Inches high. One side of him is paralytic--the effect of a cannon shot passing over him--He had two stabs in his back--one cut in his head....He lodges at the Hotel in Leicester Fields formerly the house of Hogarth. West showed me a small picture which he yesterday began to paint from memory of Koscioscow on a Couch." Evidently Kosciusko declined to pose for a portrait for West or any other artist, or to even allow them to sketch his likeness. Although West (as Farington notes) composed the present painting from memory in his studio, details of the setting correspond with other surreptitious likenesses of the Polish visitor and thus the work probably offers a reasonably accurate transcription of reality. In West's portrait, Kosciusko reclines upon a couch, favoring his wounded back and thigh; the crutch propped against the wall at left emphasizes his convalescent state. On a stool or small table in the foreground are a Polish officer's cap--indicating the sitter's nationality--and a ceremonial sword presented to Kosciusko by a contingent of English Whigs. The books and papers scattered casually about the small room--some presumably the landscape sketches mentioned by Farington and others--suggest the pastimes of an invalid; the view of Saint Paul's Cathedral localizes the scene and situates it during the Polish hero's brief stay in London. Kosciusko's dramatic pose, with one hand pressed to his bandaged forehead, simultaneously suggests "reverie and melancholy as well as debilitated health." The gesture alludes to the recurrent headaches he suffered as a result of his battle wounds, and more generally, invokes the Romantic notion of the "defeated leader": a valiant hero who has exerted great spiritual effort in an ultimately tragic cause. West painted this moving and sympathetic portrait not on commission, but to satisfy his personal admiration and respect for Kosciusko as a true contemporary hero. In this aspect, the Oberlin painting can be linked to West's dramatic, monumental scenes from contemporary history, although the unusually small scale and delicate execution of the present work, as well as its appealing informality, create a sense of intimacy unique among West's portraits of contemporary heroes.

Three days after visiting Kosciusko and commencing this portrait, on 10 June 1797, West presented the Polish general with a drawing of 'Hector Taking Leave of Andromache'. As Staley has noted, this subject--probably chosen specifically by West--"translated into a Homeric vocabulary Kosciusko's own role in the doomed cause of his country's independence from Russian domination." In 1826, six years after Benjamin West's death, the 'Portrait of General Thaddeus Kosciusko' was among 150 works offered for sale by the artist's sons to the United States as the foundation of a national gallery. The offer was rejected, and the paintings sold at auction in 1829.

M. E. Wieseman

Alone in the wilderness Hagar and Ishmael ran out of water. When they were near to death, an angel appeared and showed Hagar a well. Later Ishmael became the forefather of the Arab people.

In this story there are some different aspects which interested western artists. At first there is the terrible expulsion of the helpless mother and her child. The second is how the both where near to death in the wilderness and then saved by an angel. Some artists depict how Sarah presents Hagar to her husband, Ishmael as an archer or other scenes. But above all remain the two: the expulsion and the saving by the angel.

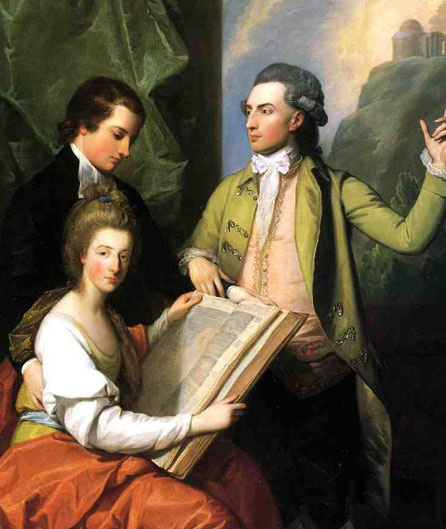

West represented the moving story of Jacob Blessing the Sons of Joseph with delicacy and classical restraint. At left, a devoted servant tenderly supports the aged patriarch as he performs the blessing. With an anxious expression, Joseph firmly grasps his father's right hand and gestures towards the figure of Manasseh in an attempt to rectify the perceived error. At the far right stands the richly garbed figure of Asenath, Joseph's wife and the daughter of an Egyptian priest.

As the Oberlin painting amply demonstrates, by the mid to late 1760's, West had established himself "not only as the most advanced proponent of the Neo-Classical style, but also as the foremost history painter in England." Works executed between 1766 and 1769 are characterized by a predominantly cool, muted palette; carefully modulated gestures and expressions; a pervasive feeling of dignity and gravitas; and an almost iconic simplicity of form and composition. The resemblance to the art of antiquity is further heightened by the conspicuous use of classical garments and accessories, and the arrangement of figures within a shallow, frieze-like space, before an architectural backdrop that lends a rhythmic unity to the scene.

Jacob Blessing was exhibited at the Society of Artists in London in 1768 together with another Old Testament scene, Elisha Raising the Shunamite's Son, also datable to 1766. The two paintings have identical dimensions, were both engraved in mezzotint by Valentine Green in 1768, and were in the same collections into the twentieth century. They are, moreover, the only biblical scenes the artist exhibited during the 1760's. It has been suggested that the thematic emphasis on children in the two pendants may bear some relation to events in the artist's own life, as his family grew and he was reunited in England with his American father.

There is some confusion surrounding the date of the Oberlin 'Jacob Blessing Ephraim and Manasseh', which is customarily given as 1766. A drawing of the composition in the collection of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts is dated 1768. Differences in detail between the drawing and the painting have suggested to Von Erffa and Staley that the drawing was a preliminary study for the Oberlin picture, and that the now-effaced date on the painting would more likely have also been 1768. Moreover, Jacob Blessing was not exhibited until 1768, and it would have been unusual for West to wait two years before exhibiting a finished painting. Nonetheless, the companion picture, 'Elisha Raising the Shunamite's Son', also bears (or bore) a date of 1766. It is possible that West began the painting now at Oberlin in about 1766, but completed it only in 1768.

M. E. Wieseman

As a young barrister, John Eardley Wilmot was taken up by Charles Talbot, 1st Baron Talbot, who was Lord Chancellor from 1733 to 1737, Philip Yorke, 1st Earl of Hardwicke, the next Lord Chancellor, 1737 to 1756, and Sir Dudley Ryder, an Attorney General and Lord Chief Justice. Bishop John Hough of Worcester wrote to Wilmot's aunt on 4 May 1737:

"I hear everybody speak of your nephew Wilmot, as one of the most hopeful young gentlemen at the Bar... he may, without presumption aspire to anything in the course of his profession; and has no small encouragement from what he has seen, since his acquaintance with Westminster-hall, in four or five of the long Robe, who have reached the top in the prime of their years."

He joined the Midland Circuit and was an advocate at the Derby Assizes. Dudley Ryder appointed Wilmot a junior counsel to the Treasury, and in 1753 he was offered promotion to King's Counsel and to sergeant-at-law, but declined and returned to Derbyshire. However, in February 1755 he accepted the appointment as a judge of the King's Bench and sergeant-at-law, and was knighted. In 1756, he became a Commissioner of the Great Seal and was proposed as Lord Chancellor, but said he didn't want it.

William Blackstone, author of the famous Commentaries on the Laws of England (four volumes, 1765-1769) was one of Wilmot's close friends. Blackstone wrote to him on 22 February 1766, after the publication of the first volume of the Commentaries: "Sir, Lord Mansfield did me the honor to inform me, that both you and himself had been so obliging as to mark out a few of the many errors, which I am sensible are to be met with in the Book which I lately published. Nothing can flatter me so much as that you have thought it worth the pains of such a revisal."

In August 1766, Wilmot became Chief Justice of the Common Pleas, and in September 1766 joined the Privy Council. In 1770, he again refused appointment as Lord Chancellor, and in January 1771 resigned as Chief Justice.

In the aftermath of the American Revolutionary War, Wilmot was appointed as a royal commissioner to investigate claims by American Loyalists for compensation for the losses they had suffered as a result of the war.

He died in London in 1792 and was buried at Berkswell, Warwickshire, a country estate which had been inherited by his wife.

In West's portrait he wears a Maori cloak and stands beside other trophies from New Zealand and Polynesia, as if in rebuke of his more conventional contemporaries who were portrayed in Rome with their purchases of classical antiquities.

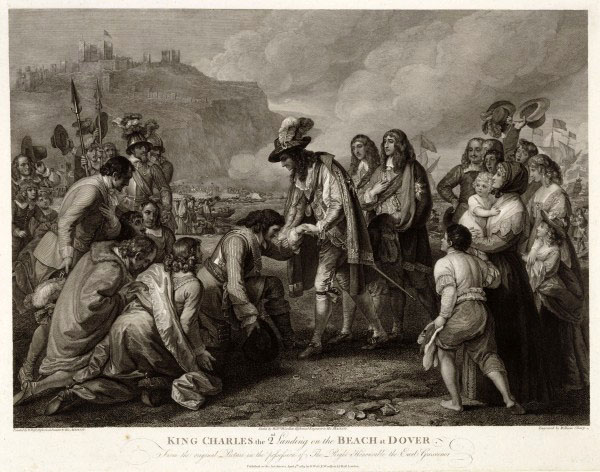

Charles was greeted by a tumultuous welcome from the vast crowds gathered on the beach and a salute was fired from the guns of the Castle. This acclamation must have, in some part, been due to a feeling of relief at the prospect of having once more a King and settled government after the turmoil of the Civil War. The King must have been greatly moved by the welcome he received, as letters which he wrote afterwards show. The diarist Samuel Pepys was in the King's entourage and described the event, and an extract from the Dover Corporation Records gives some further details of this historic scene:

Memorandum: "That the 25th May, 1660, the King arrived in Dover Roads from Holland with twenty sail of His Majesty's great ships and frigates, the Right Honorable Edward Lord Montague being General, and landed the same day being attended by 'His Excellency the Lord General Monck' who first met His Majesty upon the bridge let into the sea for His Majesty's more safe and convenient landing, and at His Majesty's coming from the bridge, the Mayor of this Town, Thomas Broome, Esq., made a speech to His Majesty upon his knees, and Mr. John Reading, Minister of the Gospel, presented His Majesty with the Holy Bible as a gift from this town, and Mr. Reading thereupon made a speech likewise to His Majesty and His Gracious Majesty laying his hand upon his breast , told Mr. Mayor nothing would be more dear to him than the Bible. His Excellency the Lord General was accompanied with the Earl of Winchelsea and a great number of nobility and gentry of England and his life guard all most richly accoutered."

Lot is most famous for his dramatic escape from the city of Sodom after he offered hospitality to two angels and tried to protect them from men of the city, who sought to do them grievous harm. After Sodom was destroyed, Lot lived with his two daughters in a cave and, according to the biblical account, fathered sons by them. In this way, he became the ancestor of the Ammonites and the Moabites.

When Genesis 19 opens, Lot no longer lived in tents and tended his flocks, but had settled in Sodom with his wife and two daughters, none of whom is named in the text. Two angels arrived in Sodom on a mission from God to destroy the town for its wickedness. However, they first warned the relatively righteous Lot and gave him and his family a chance to escape. Lot offered the angels-here called "men"-hospitality. However, the wicked men of Sodom demanded that the visitors be brought out to them to rape them (19:5). Horrified at this outrage, Lot offered the men his virgin daughters instead (19:8), but the would-be attackers only threatened to break down the door in order to have their way with Lot's guests.

The angels immediately struck the townsmen with blindness and warned Lot of the impending doom that God has pronounced on Sodom. At their suggestion, Lot attempted to warn his sons-in-law-who were legally pledged but not yet married to his daughters-of the catastrophe, but they did not take his warning seriously.

At dawn, the angels led Lot and his family out of the city, taking each of them by the hand when Lot hesitated. "Flee for your lives!" one of them commanded. "Don't look back, and don't stop anywhere in the plain! Flee to the mountains or you will be swept away!"

Lot feared he had insufficient time to reach the mountains and asked instead to find shelter in the small town of Zoar. The angels agreed not to destroy this town, on the grounds that it was only a small village and therefore not very wicked. With Lot safe in Zoar and the sun now fully risen, God destroyed both Sodom and Gomorrah, as well as the surrounding plain and all of its vegetation. Lot's wife, however, made the tragic mistake of looking back toward Sodom while the destruction proceeded, and was turned into a pillar of salt as a result.

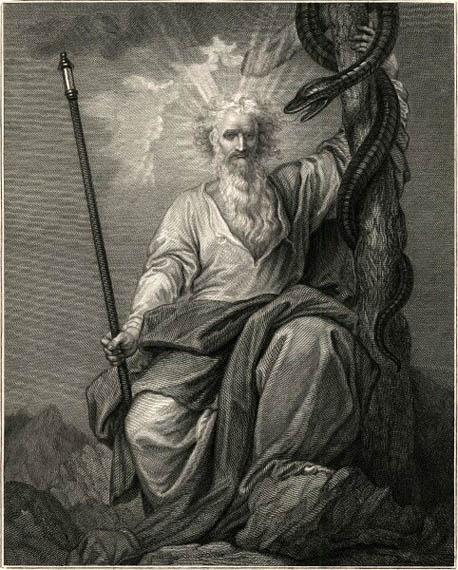

Then God commanded Moses to take the rod with which he had struck the rock in Horeb, and before all the people to speak to a certain rock, which He pointed out, and it should give water for them and their cattle.

But now both Moses, and Aaron, who was to go with him, did wrong. They thought that speaking to the rock, as God had said, would not be sufficient; so Moses struck it twice with his rod, angrily asking the multitude whether he and Aaron must fetch them water out of the rock.

And though, notwithstanding their disobedience, the water, when the rock was struck, flowed out in such abundance that all had enough, God told Moses and Aaron that because they had not obeyed Him when He bade them speak to it only, they should neither of them enter into the Promised Land.

Aaron, whom God had appointed chief priest, died very soon afterward, on Mount Hor, and Eleazar, his son, was chosen by God as priest in his place.

The land of Edom, which God had given to Esau, now lay between the Israelites and the way by which they were to go to Canaan. So Moses sent messengers to the King of Edom, asking leave to pass through.

But the king not only refused to let them pass through, but threatened to lead out his army against the Israelites; so they were obliged to turn aside, and go round Edom. There they met with so many difficulties that they got quite dispirited, and, as before, murmured against God.

Then God, to punish them, sent among them fiery serpents, which stung great numbers of the people, so that they died. The fear of death made the Israelites repent, and confess their sin in speaking against God.

So they asked Moses to pray for them, that God would take away those dreadful serpents. And when Moses prayed, God told him to make an image in brass in the likeness of one of the serpents, and to set it up on a pole, and He promised that everyone who was stung should be cured when he looked up to it.

Moses did as he was commanded. And every one who looked upon the brazen serpent was healed.

And the people thirsted there for water; and the people murmured against Moses, and said, Wherefore is this that thou hast brought us up out of Egypt, to kill us and our children and our cattle with thirst?

And Moses cried unto the LORD, saying, What shall I do unto this people? …

And the Lord said unto Moses, Go on before the people, and take with thee of the elders of Israel; and thy rod, wherewith thou smote the river, take in thine hand, and go.

Behold, I will stand before thee there upon the rock in Horeb; and thou shalt smite the rock, and there shall come water out of it that the people may drink. And Moses did so in the sight of the elders of Israel.

In Christian art, the rock is traditionally said to symbolize Christ while the water represents everlasting life. However, there is also a more negative connotation to this story as a very similar incident is related in Numbers (Chapter 20) in which Moses is instructed to speak to the rock but strikes it instead. As punishment, God forbids him from entering the Promised Land.

West's composition is dependent on his knowledge of the Old Masters. The grand style and emotive tone of the image correspond with other scenes that West planned to paint for the King's new chapel at Windsor in which he intended to illustrate the theme of 'Revealed Religion'. This drawing was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1784 as a design for the chapel, alongside 'Death on the Pale Horse' and 'The Last Supper', but it was dropped from the programme shortly afterwards, West substituting different scenes from the life of Moses in its place.

West retouched this composition and that of 'Death on the Pale Horse' in 1803. The diarist and artist Joseph Farington recorded: 'West showed me several drawings begun at different periods, - now retouching them. - said He knew as much of Composition when he was 26 years old as now, but his judgment in heightening, and of effect is better.'

Peter joined the Jamaican House of Assembly and became the Speaker. In 1710, during a debate at the Assembly, things became extremely heated and some members drew their swords and threatened Peter, the Speaker. The Governor responded to shouts for assistance and the doors of the chamber were forced open. The Assembly was dissolved in the name of the Queen. The aged Peter Beckford Senior was among those who had come to his rescue. In the general confusion, he slipped and fell down the long staircase. Suffering a mortally injury, he died soon after.

Like his father, Beckford suffered a severe temper. As a young man, he was accused of killing the Deputy Judge Advocate of Jamaica in a fit of temper. He was finally acquitted after a lengthy court case.

In 1720, he was one of the prominent people in Jamaica about whom the governor Sir Nicholas Lawes complained had "anarchical principles".

Peter married Bathshua Herring and they had thirteen children. He died in 1735. His will included a legacy of 2,000 Pounds to found a school in Spanish Town, which was started there in 1744. This school merged with another school started with 3,000 Pounds donated by Francis Smith forming the Beckford and Smith School in 1869.

His son, William was born in 1709. He immigrated to England and had a prominent career in politics, defending the West Indian Interest as a Member of Parliament and Lord Mayor of London.

In Euripides' play Heracleidae, Hebe granted Iolaus' wish to become young again in order to fight Eurystheus. Hebe had two children with her husband Heracles: Alexiares and Anicetus. The name Hebe comes from Greek word meaning "youth" or "prime of life".. In art, Hebe is usually depicted wearing a sleeveless dress.

This poem is in Book III of the Metamorphoses, and tells the story of a "talkative nymph" who "yet a chatterbox, had no other use of speech than she has now, that she could repeat only the last words out of many." She falls in love with Narcissus, whom she catches sight of when he is "chasing frightened deer into his nets." Eventually, after "burning with a closer flame," Echo's presence is revealed to Narcissus, who, after a comic yet tragic scene, rejects her love. Echo wastes away, until she "remains a voice" and "is heard by all." This is the explanation of the aural effect which was named after her.

Then, Narcissus "tired from both his enthusiasm for hunting and from the heat" rests by a spring, and whilst drinking, "a new thirst grows inside him" and he is "captivated by the image of the beauty he has seen" and falls deeply in love with "all the things for which he himself is admired." He then wastes away with love for himself, echoing the manner in which Echo did earlier on. A while later his body is gone and in its place is a narcissus flower that came upon his actions.

The Long Parliament is the name of the English Parliament called by Charles I, on 3 November 1640, following the Bishops' Wars. It received its name from the fact that through an Act of Parliament, it could only be dissolved with the agreement of the members, and those members did not agree to its dissolution until after the English Civil War and at the end of Interregnum in 1660. It sat from 1640 until 1649, when it was purged by the New Model Army of those who were not sympathetic to the Army's concerns. Those members who remained after the Army's purge became known as the Rump Parliament. During the Protectorate, the Rump was replaced by other Parliamentary assemblies, only to be recalled after Oliver Cromwell's death in 1658 by the Army in the hope of restoring credibility to the Army's rule. When this failed, General George Monck allowed the members barred in 1649 to retake their seats so that they could pass the necessary legislation to initiate the Restoration and dissolve the Long Parliament. This cleared the way for a new Parliament, known as the Convention Parliament, to be elected.

.jpg)

Colonel Johnson is shown in a relaxed pose, with an Indian cloak draped over his uniform and moccasins on his feet. Behind him, in the half shadow, stands an Indian chief who is smiling down on the seated man and pointing out, with a gesture of his left hand, the peaceful existence of his tribe, visible in the background. The fresh, clear face of the colonel, the Indian attributes and the chief himself all suggest a love of liberty without violence, and a sense of honest and egalitarian cooperation.

Prince Octavius was born, on 23 February 1779, at Buckingham Palace, London, England. His father was George III, his mother Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz. His name derives from Latin octavus, the eighth, showing that he was the eighth son of his parents.

Octavius was christened on 23 March 1779, in the Great Council Chamber at Saint James's Palace, by Frederick Cornwallis, The Archbishop of Canterbury. His godparents were The Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbuttel, The Duke of Mecklenburg and The Duchess of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach.

The Prince Octavius died (possibly from fever), on 3 May 1783, at Kew Palace, London, aged four years old. Octavius's death devastated his father. Shortly afterward, King George said "There will be no heaven for me if Octavius is not there."

.jpg)

Octavius Hanover, Prince of Great Britain and Ireland gained the title of HRH Prince Octavius of Great Britain and Ireland.

Alfred Hanover, Prince of Great Britain and Ireland was born on 22 September 1780 at Windsor Castle, Windsor, Berkshire, England. He was the son of George III Hanover, King of Great Britain and Sophie Charlotte Herzogin von Mecklenburg-Strelitz. He died on 20 August 1782 at age 1 at Windsor Castle, Windsor, Berkshire, England.

Alfred Hanover, Prince of Great Britain and Ireland gained the title of HRH Prince Alfred of Great Britain and Ireland.

Amelia Hanover, Princess of the United Kingdom was born on 7 August 1783 at Royal Lodge, Windsor, Berkshire, England. She was the daughter of George III Hanover, King of Great Britain and Sophie Charlotte Herzogin von Mecklenburg-Strelitz. She died on 2 November 1810 at age 27 at Augusta Lodge, Windsor, Berkshire, England, from erysipelas. She was buried at St. George's Chapel, Windsor Castle, Windsor, Berkshire, England.

Amelia Hanover, Princess of the United Kingdom gained the title of HRH Princess Amelia of the United Kingdom. She and General Honorable Charles FitzRoy were associated. There is conflicting evidence as to whether these two were married. She has an extensive biographical entry in the Dictionary of National Biography.

Newton was educated at Trinity College, Cambridge, and was subsequently elected a fellow of Trinity. He was ordained in the Church of England, and continued scholarly pursuits. His best remembered works include his annotated edition of Paradise Lost, including a biography of John Milton published in 1749. In 1754 he published a large scholarly analysis of the prophecies of the Bible, titled Dissertations on the Prophecies.

Title page of a 1752-1761 edition of Newton's extensively annotated works of John Milton, particularly Paradise Lost and Paradise Regained. Newton was elevated to Bishop of Bristol in 1761, and was recognized again in 1768 by being named the Dean of St Paul's Cathedral in London. He was a Christian Universalist.

One of Newton's famous quotes concerns the Jewish people:

"The preservation of the Jews is really one of the most signal and illustrious acts of divine Providence... and what but a supernatural power could have preserved them in such a manner as none other nation upon earth hath been preserved. Nor is the providence of God less remarkable in the destruction of their enemies, than in their preservation... We see that the great empires, which in their turn subdued and oppressed the people of God, are all come to ruin... And if such hath been the fatal end of the enemies and oppressors of the Jews, let it serve as a warning to all those, who at any time or upon any occasion are for raising a clamor and persecution against them"

While returning from the Crusade, Richard was captured and imprisoned by Henry VI, Holy Roman Emperor. John is said to have sent a letter to Henry asking him to keep Richard away from England for as long as possible. But Richard's supporters paid a ransom for his release because they thought that John would make a terrible King. On his return to England in 1194, Richard forgave John and named him as his heir.

Other historians argue that John did not attempt to overthrow Richard, but rather did his best to improve a country ruined by Richard's excessive taxes used to fund the Crusade. It is most likely that the image of subversion was given to John by later monk chroniclers, who resented his refusal to go on the ill-fated Fourth Crusade.

Queen Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1744-1818) married George III in 1761; the couple had fifteen children - six daughters and nine sons. Their court was reputed to be the dullest in Europe. According to one legend Queen Charlotte introduced the Christmas tree to England from her native Germany. Mecklenburg County, North Carolina was named in the Queen's honor, as was its largest city, Charlotte.