An American Painter from Rhode Island

1755 - 1828

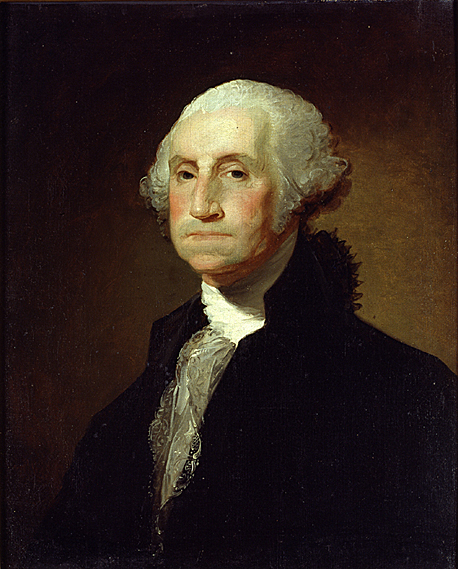

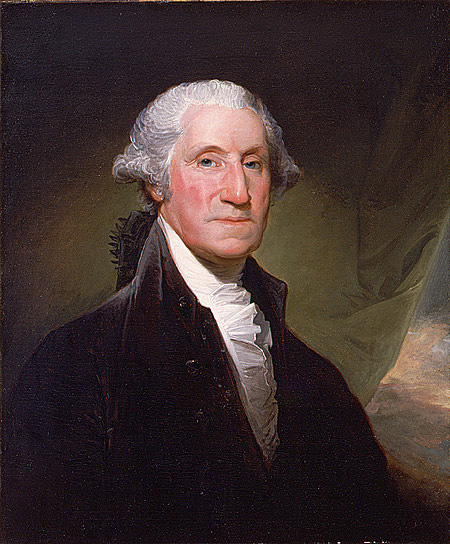

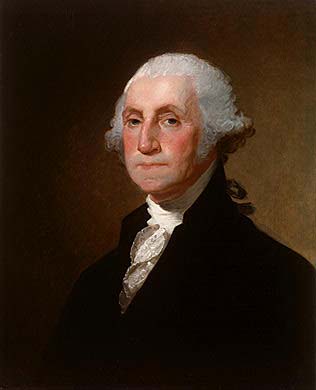

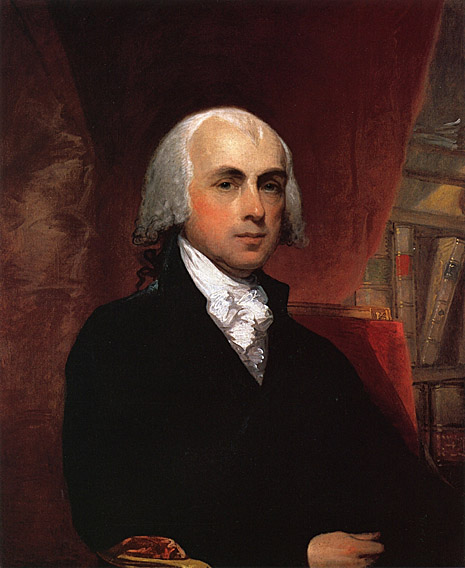

Gilbert Stuart is widely considered to be one of America's foremost portraitists. His best known work, the unfinished portrait of George Washington that is sometimes referred to as The Athenaeum, was begun in 1796 and left incomplete at the time of Stuart's death in 1828. The image of George Washington featured in the painting has appeared on the United States one-dollar bill for over one century.

Throughout his career, Gilbert Stuart produced portraits of over 1,000 people, including the first six Presidents of the United States. His work can be found today at art museums across the United States and the United Kingdom, most notably the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., the National Portrait Gallery in London, and the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.

Gilbert Stuart was born in Saunderstown, Rhode Island in 1755. He was the third son of Gilbert Stewart, a Scottish immigrant employed in the snuff-making industry, and Elizabeth Anthony Stewart, a member of a prominent land-owning family from Middletown, Rhode Island. Stuart's father worked in the first colonial Snuff Mill in America, which was located in the basement of the family homestead.

Gilbert Stuart moved to Newport, Rhode Island at the age of seven, where his father pursued work in the merchant field. In Newport, Stuart first began to show great promise as a painter. He was tutored by Cosmo Alexander, a Scottish painter. Under the guidance of Alexander, Stuart painted the famous portrait Dr. Hunter's Spaniels, which hangs today in the Hunter House Manison in Newport, when he was 12-years-old.

Stuart moved to Scotland with Alexander in 1771 to finish his studies. His mentor died in Edinburgh the following year. Attempting briefly and without success to earn a living as a painter, he returned to Newport in 1773.

Stuart's prospects as a portraitist were jeopardized by the onset of the American Revolution and its social disruptions. Following the example set by John Singleton Copley, Stuart departed for England in 1775. Unsuccessful at first in pursuit of his vocation, he then became a protégé of Benjamin West, with whom he studied for the next six years. The relationship was a beneficial one, with Stuart exhibiting at the Royal Academy as early as 1777.

By 1782 Stuart had met with success, largely due to acclaim for The Skater, a portrait of William Grant. At one point, the prices for his pictures were exceeded only by those of renowned English artists Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough. Despite his many commissions, however, Stuart was habitually neglectful of finances and was in danger of being sent to debtors' prison. In 1787 he fled to Dublin, Ireland, where he painted and accumulated debt with equal vigor.

Stuart returned to the United States in 1793, settling briefly in New York City. In 1795 he moved to Germantown, Pennsylvania, near (and now part of) Philadelphia, where he opened a studio. It was here that he would gain not only a foothold in the art world, but lasting fame with pictures of many important Americans of the day.

Stuart painted George Washington in a series of iconic portraits, each of them leading in turn to a demand for copies and keeping Stuart busy and highly paid for years. The most famous and celebrated of these likenesses, known as The Athenaeum, is currently portrayed on the United States one dollar bill. Stuart, along with his daughters, painted a total of 130 reproductions of The Athenaeum. However, Stuart never completed the original version; after finishing Washington's face, the artist kept the original version to make the copies. He sold up to 70 of his reproductions for a price of US$100 each, but the original portrait was left unfinished at the time of Stuart's death in 1828. The painting now hangs in Boston's Museum of Fine Arts.

Another celebrated image of Washington in the Lansdowne Portrait, a large portrait with one version is hanging in the East Room of the White House. During the burning of Washington by British troops in the War of 1812, this picture was saved through the intervention of First Lady Dolley Madison. Gilbert painted 12 versions of the portrait throughout his life. Most of the U.S. states feature a copy of the painting hanging in their state capitol. In 1803, Stuart opened a studio in Washington, D. C.

This is taken from a letter by First Lady Dolley Madison to her sister, Anna, written the day before Washington, D.C. was burned by British forces during the War of 1812. The letter describes the abandonment of the White House and Mrs. Madison's famous actions saving Gilbert Stuart's priceless portrait of George Washington. As Mrs. Madison fled she rendezvoused with her husband, and together, from a safe distance, they watched Washington burn.

My husband left me yesterday morning to join General Winder. He inquired anxiously whether I had courage or firmness to remain in the President's house until his return on the morrow, or succeeding day, and on my assurance that I had no fear but for him, and the success of our army, he left, beseeching me to take care of myself, and of the Cabinet papers, public and private. I have since received two dispatches from him, written with a pencil. The last is alarming, because he desires I should be ready at a moment's warning to enter my carriage, and leave the city; that the enemy seemed stronger than had at first been reported, and it might happen that they would reach the city with the intention of destroying it. I am accordingly ready; I have pressed as many Cabinet papers into trunks as to fill one carriage; our private property must be sacrificed, as it is impossible to procure wagons for its transportation. I am determined not to go myself until I see Mr. Madison safe, so that he can accompany me, as I hear of much hostility towards him. Disaffection stalks around us. My friends and acquaintances are all gone, even Colonel C. with his hundred, who were stationed as a guard in this inclosure. French John (a faithful servant), with his usual activity and resolution, offers to spike the cannon at the gate, and lay a train of powder, which would blow up the British, should they enter the house. To the last proposition I positively object, without being able to make him understand why all advantages in war may not be taken.

Wednesday Morning, twelve o'clock. -- Since sunrise I have been turning my spy-glass in every direction, and watching with unwearied anxiety, hoping to discover the approach of my dear husband and his friends; but, alas! I can descry only groups of military, wandering in all directions, as if there was a lack of arms, or of spirit to fight for their own fireside.

Three o'clock. -- Will you believe it, my sister? we have had a battle, or skirmish, near Bladensburg, and here I am still, within sound of the cannon! Mr. Madison comes not. May God protect us! Two messengers, covered with dust, come to bid me fly; but here I mean to wait for him... At this late hour a wagon has been procured, and I have had it filled with plate and the most valuable portable articles, belonging to the house. Whether it will reach its destination, the "Bank of Maryland," or fall into the hands of British soldiery, events must determine. Our kind friend, Mr. Carroll, has come to hasten my departure, and in a very bad humor with me, because I insist on waiting until the large picture of General Washington is secured, and it requires to be unscrewed from the wall. This process was found too tedious for these perilous moments; I have ordered the frame to be broken, and the canvas taken out. It is done! and the precious portrait placed in the hands of two gentlemen of New York, for safe keeping. And now, dear sister, I must leave this house, or the retreating army will make me a prisoner in it by filling up the road I am directed to take. When I shall again write to you, or where I shall be to-morrow, I cannot tell!

Stuart moved to Boston in 1805, continuing in critical acclaim and financial troubles. In 1824 he suffered a stroke, which left him partially paralyzed. Nevertheless, Stuart continued to paint for two years until his death in Boston at the age of 72. He was buried in the Old South Burial Ground of the Boston Common. As Stuart left his family deeply in debt, his wife and daughters were unable to purchase a grave site. Stuart was therefore buried in an unmarked grave which was purchased cheaply from Benjamin Howland, a local carpenter. When Stuart's family recovered from their financial troubles roughly ten years later, they planned to move his body to a family cemetery in Newport, Rhode Island. However, since his family could not remember the exact location of Stuart's body, it was never moved.

By the end of his career, Gilbert Stuart had taken the likenesses of over one thousand American political and social figures. He was praised for the vitality and naturalness of his portraits, and his subjects found his company agreeable:

Speaking generally, no penance is like having one's picture done. You must sit in a constrained and unnatural position, which is a trial to the temper. But I should like to sit to Stuart from the first of January to the last of December, for he lets me do just what I please, and keeps me constantly amused by his conversation.

- John Adams

Stuart was known for working without the aid of sketches, beginning directly upon the canvas. This was very unusual for the time period.

His works can be found today at art museums throughout the United States and Great Britain, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., the National Portrait Gallery in London, and the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.

Today, Stuart's birthplace in Saunderstown, Rhode Island is open to the public as the Gilbert Stuart Birthplace and Museum. The museum consists of the original house Stuart was born in, with copies of paintings from throughout his career hanging throughout the house. The museum opened in 1930.

I find it difficult to comprehend, as I write this in April of 2008, that the challenge and responsibility that were given to Mr. Jefferson, Mr. Adams, and Mr. Franklin in 1776 still remain unfulfilled and lack the affirmation of far too many Americans today. It seems that history is a phenomena that we still cannot learn or much less remember, so we find ourselves continually condemned to repeat imposing the sins of our fathers upon ourselves. If this is not cultural and moral insanity, I do not know what further retrenchment of this magnitude will bring to humanity. Then I read the dialogue that went on between Abigail and Sam Adams and wonder why we have been so little and so small that we still cannot comprehend the 'Enlightenment' that this woman possessed.

MARCH 31, 1776

ABIGAIL ADAMS TO JOHN ADAMS

"I long to hear that you have declared an independency. And, by the way, in the new code of laws which I suppose it will be necessary for you to make, I desire you would remember the ladies and be more generous and favorable to them than your ancestors."

"Do not put such unlimited power into the hands of the husbands."

"Remember, all men would be tyrants if they could. If particular care and attention is not paid to the ladies, we are determined to foment a rebellion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any laws in which we have no voice or representation."

"That your sex are naturally tyrannical is a truth so thoroughly established as to admit of no dispute; but such of you as wish to be happy willingly give up -- the harsh tide of master for the more tender and endearing one of friend."

"Why, then, not put it out of the power of the vicious and the lawless to use us with cruelty and indignity with impunity?"

"Men of sense in all ages abhor those customs which treat us only as the (servants) of your sex; regard us then as being placed by Providence under your protection, and in imitation of the Supreme Being make use of that power only for our happiness."

APRIL 14, 1776

JOHN ADAMS TO ABIGAIL ADAMS

"As to your extraordinary code of laws, I cannot but laugh."

"We have been told that our struggle has loosened the bonds of government everywhere; that children and apprentices were disobedient; that schools and colleges were grown turbulent; that Indians slighted their guardians, and negroes grew insolent to their masters."

"But your letter was the first intimation that another tribe, more numerous and powerful than all the rest, were grown discontented."

"This is rather too coarse a compliment, but you are so saucy, I won't blot it out."

"Depend upon it, we know better than to repeal our masculine systems. Although they are in full force, you know they are little more than theory. We dare not exert our power in its full latitude. We are obliged to go fair and softly, and, in practice, you know we are the subjects."

"We have only the name of masters, and rather than give up this, which would completely subject us to the despotism of the petticoat, I hope General Washington and all our brave heroes would fight."

MAY 7, 1776

ABIGAIL ADAMS TO JOHN ADAMS

"I cannot say that I think you are very generous to the ladies; for, whilst you are proclaiming peace and good-will to men, emancipating all nations, you insist upon retaining an absolute power over wives."

"But you must remember that arbitrary power is like most other things which are very hard, very liable to be broken; and, notwithstanding all your wise laws and maxims, we have it in our power, not only to free ourselves, but to subdue our masters, and without violence, throw both your natural and legal authority at our feet."

The right of women to vote was not recognized by the United States until 1920, more than 144 years after the Declaration of Independence. And that's not because no one earlier had thought of it!

1777 -- Women lose the right to vote in New York

1780 -- Women lose the right to vote in Massachusetts

1784 -- Women lose the right to vote in New Hampshire

1787 -- Women in all states except New Jersey lose the right to vote

On the night of April 26, 1777, Sybil Ludington, age 16, rode through towns in New York and Connecticut warning that the Redcoats were coming to Danbury, CT. She gathered enough volunteers to help beat back the British the next day. Her ride was twice the distance of Paul Revere's. Her hometown was renamed after her.

On June 28, 1778, while "attending the (artillery) piece" with her husband at the battle of Monmouth, N.J., a cannon shot passed between the legs of Mary Hays (Molly Pitcher) tearing off the lower part of her skirt -- and she kept on loading her cannon. When her husband was wounded, she either fired the cannon once alone or several times, depending on witnesses. In 1822, she was awarded a soldier's pension of $40 a year.

In October of 1778 Deborah Samson of Plymouth Massachusetts disguised herself as a young man and presented herself to the American army as a willing volunteer to oppose the common enemy. She enlisted for the whole term of the war as Robert Shirtliffe and served in the company of Captain Nathan Thayer of Medway, Massachusetts. For three years she served in various duties and was wounded twice -- the first time by a sword cut on the side of the head and four months later by a shot through the shoulder.

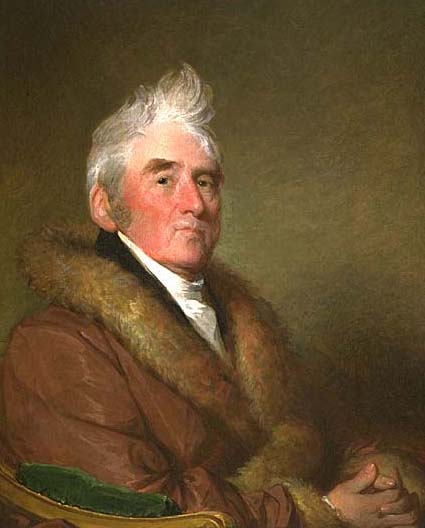

Gilbert Stuart (1755-1828)

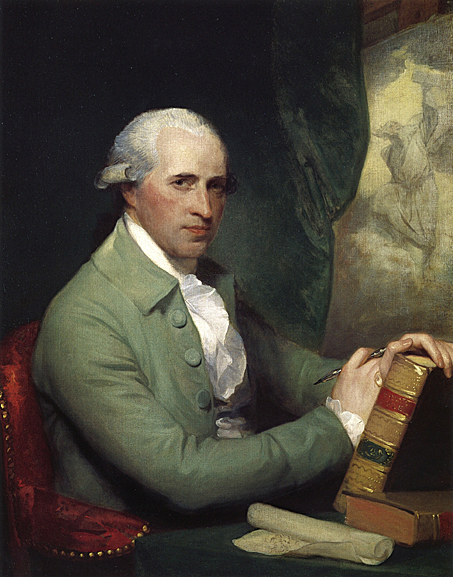

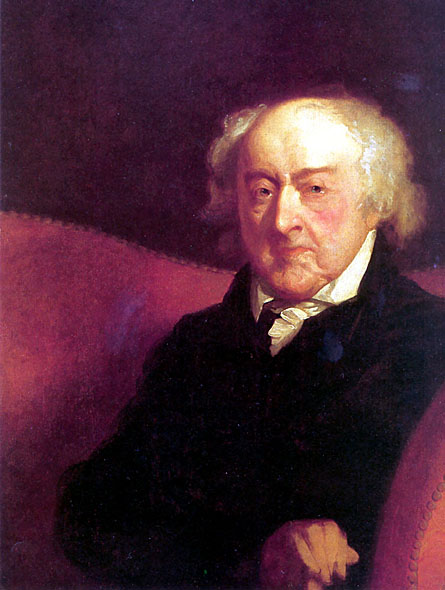

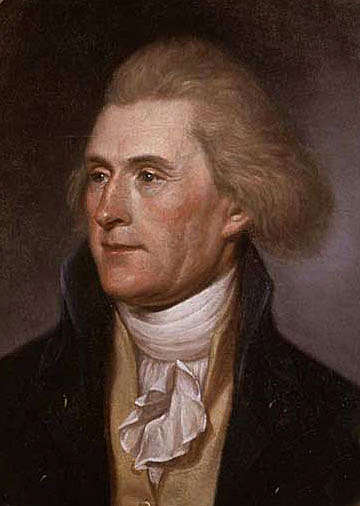

The most successful and resourceful portraitist of America's early national period, Gilbert Stuart possessed abundant natural talent which he devoted to the representation of human likeness and character, bringing his witty and irascible manner to bear on each of his works, including his incisive portraits of George Washington. Stuart's legacy is defined by the seemingly contradictory aspects of his life. He was quite prolific, executing more than 1,100 portraits, despite bouts of depression that sent him to his bed for weeks at a time. Like other artists of his caliber, he is remembered for his masterpieces, despite a pattern of failing to finish or summarily finishing works that bored him. He commanded high prices, but constantly teetered on the verge of bankruptcy. More than a few of the sitters who enjoyed his company and anticipated the skillful portrait that would result were disappointed that the painter's slow, dilatory work habits. Said John Adams, who sat for the artist several times, "Mr. Stuart thinks it the prerogative of genius to disdain the performance of his engagements."

Stuart usually follows Benjamin West and John Singleton Copley in the canonical story of American art and, as a student of the former and admirer of the latter, his attachments to these elder painters are undeniable. His career nearly parallels that of his almost exact contemporary John Trumbull, whose equally complex and testy personality matched Stuart's erratic disposition. The principle difference between the two is that, while Trumbull alternated between anger at his patrons and guilt for not having pleased them, Stuart remained unfailingly sanctimonious. He knew well the conventions of portraiture, easily rendered the attributes of gentility and affluence, and succeeded time and again in executing portraits that fulfilled in pictorial terms the wishes and desires of his sitters. That said, he maintained that his success had little to do with a sitter's character or accomplishments, but rather more with his own artistic abilities. More than once, Stuart escorted to his studio door sitters who thought otherwise.

Stuart first proved his talent in Newport, Rhode Island, near his hometown of Kingston. In portraits executed there, Stuart revealed not merely precocious talent but adept technique controlled by his rather quirky and appealing take on contemporary British portraiture. He mastered the techniques of the English grand manner during his years in London (1777-87) and Dublin (1787-93). For an American painter, study in England was a prerequisite for attaining greatness, but Stuart traveled there more due to haphazard circumstances than deliberate action, a pattern that would be repeated again and again. It took him five years to achieve acclaim for his work in London, but after the exhibition of masterful full-length portraits like Captain John Gell, he joined the ranks of the best and most sought-after British painters.

Success abroad spurred Stuart toward greater ambition: to paint a portrait of George Washington. He left Dublin in early 1793 and headed for New York, where he garnered commissions from the rich and famous, such as General Horatio Gates (1977.234) and Josef de Jaudenes y Nebot and his American wife. He completed these commissions at an extraordinary pace and with remarkable skill, which may be attributed not only to the caliber of his clientele, but to the extra effort Stuart was willing to make in order to succeed in the work that really interested him-securing the requisite introductions to the President.

Stuart moved to Philadelphia in 1795, when arrangements with Washington were a certainty. He had several sittings with the sixty-three-year-old President, the result of which were numerous portraits of differing image, quality, and purpose. The first sitting was in March 1795, from which he executed the so-called Vaughan image, and he received another series of sittings in March 1796, when the full-length image was commissioned. Stuart's trouble with Washington belies the degree of spontaneity in many of the portraits. An artist accustomed to easily engaging and enlivening his clients with conversation and jokes, Stuart was at a loss with Washington: "Antipathy seemed to seize him and a vacuity spread over his countenance, most appalling to paint." Yet, despite the struggle to capture the President's elusive character, Stuart succeeded in executing the image that was then and is now considered to be a definitive and insightful likeness.

Carrie Rebora Barratt

Department of American Paintings and Sculpture, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Born in Switzerland, Gallatin immigrated to America in the 1780s, ultimately settling in Pennsylvania. He was politically active against the Federalist Party program, and was elected to the United States Senate in 1793, but was removed from office by a 14-12 party-line vote after a protest raised by his opponents suggested he had fewer than the required nine years of citizenship. In 1795 he was elected to the House of Representatives and served in the fourth through sixth Congresses, becoming House Majority Leader. He was an important leader of the new Democratic-Republican Party, and its chief spokesman on financial matters and opposed the entire program of Alexander Hamilton. He also helped found the House Committee on Finance (later the Ways and Means Committee) and often engineered withholding of finances by the House as a method of overriding executive actions to which he objected.

Lee was born in England to Irish parents. His father was a colonel in the British army and enrolled his son in a Swiss military school. Young Lee was commissioned as an ensign in the army at age 12. Three years later he entered regular service in his father's regiment.

During the French and Indian War, Lee was assigned to the American colonies, where he was counted among the survivors of Braddock's disastrous defeat in 1755, sharing his good fortune with comrades George Washington, Horatio Gates and Thomas Gage. Later in the conflict Lee purchased a military command in the Mohawk Valley, where he casually married a Mohawk woman and was adopted by the tribe. His unpredictable behavior and violent temper earned him the name of "Boiling Water" among the natives. Lee was a gangly man whose unhandsome face was dominated by a huge nose - a tempting target for caricaturists of the day. Despite an excellent education and a record of great achievement, he felt throughout his life the need to inflate his reputation with long-winded accounts of his adventures. He disliked most people, but made exceptions for fellow soldiers and prostitutes. His closest companions were dogs; he was nearly always surrounded by a pack of ill-trained hounds and his prized Pomeranian. His vanity led him to buy expensive tailored uniforms, but he seldom bothered to have them cleaned. Some of his contemporaries preferred the smell of the dogs to that of Lee himself.

Lee was badly wounded in the attack on Ticonderoga in 1758, but recovered in time to participate in the campaigns at Niagara and Montreal. He returned to England in 1760 before being assigned to Portugal, where he served under John Burgoyne. Like many career soldiers of the era, Lee sought employment in foreign armies during peacetime. He served twice in the Polish army and hoped to parlay that experience into a lucrative appointment from George III. During a face-to-face meeting with the king, who declined to offer the desired command, Lee rebuked the monarch and swore that he would never give the king an opportunity to break another promise. An embittered Lee became enmeshed in Whig politics and retired to America on half pay in 1773.

From the beginning of his new life in the colonies, Lee was an outspoken radical. He aligned himself with the emerging patriot cause and became an early advocate of a separate colonial army. After hostilities commenced, Lee's pride was slighted when the less experienced Washington was appointed commander of the American forces. Thanks to the support of the Adams cousins in Massachusetts (and encouraging words from Washington), Lee was made a major general and third in the line of command.

Following initial service at the siege of Boston, Lee was given command of the Southern Department in March 1776. His assignment was to protect Charleston, the most important port in the South, from a sea-based British force under Sir Henry Clinton. Hostilities in that theater commenced in June. The patriot forces succeeded in holding a fortified position on Sullivan's Island in Charleston Harbor. Lee emerged from the successful defense with a heightened reputation, despite the fact that much of the credit rightly belonged to Colonel William Moultrie. Both were honored by Congress for their efforts.

In the fall of 1776, Lee was summoned north to assist Washington in his attempts to stem the Continental Army's string of defeats. The grim military prospects did not prevent Lee from securing an advance payment of $30,000 from Congress. That sum equaled uncollectible debts owed him in England and was used to purchase an estate in Virginia. Despite his successes, controversy began to develop around Lee's military conduct. He served admirably at White Plains (October 1776), but after receiving a separate command, he was lethargic in responding to Washington's calls for assistance. Lee also began correspondence with Joseph Reed, the army's adjutant general, and members of Congress in which he repeatedly expressed strong reservations about Washington's military abilities. Some have speculated that Lee wanted to see his superior defeated so that he could take command.

In December 1776, Lee left his army to spend the evening in White's Tavern in Basking Ridge, New Jersey. The attractions were food, drink and the charms of one of the establishment's resident women. Accompanied by only a small guard, Lee was surprised the next morning by the arrival of a British party under Benastre Tarleton, a former comrade who had sworn an oath in a London club to track down and decapitate Lee. Following a brief skirmish during which escape routes were cut off, a humiliated Lee was taken prisoner and removed to New York City. Lee's unexpected capture was the cause of great celebrations at the British headquarters and officers there predicted a swift end to the conflict. A night of careless lust had allowed the British to capture the enemy's most able general and their most despised traitor.

Washington was distraught with the loss of his difficult subordinate and attempted to arrange a prisoner exchange. The Americans, however, held no high-ranking British captives and the effort failed. While in confinement, Lee drafted a battle plan for the British and received excellent treatment in return. He was provided with a comfortable three-room suite, food, wine and a personal servant. However, no effort was ever made by his captors to implement the war plan. Lee was released in an exchange in the spring of 1778, in the wake of the major British defeat at Saratoga the previous fall.

Lee reported to Washington at Valley Forge in May. When word was received of the impending British withdrawal from Philadelphia, Lee argued vigorously for allowing Clinton to depart unimpeded, leading some of his critics to question his judgment and others his loyalty. Washington chose to shadow the retreating British across New Jersey and hoped to engage them before they reached Middletown. Lee was chosen to lead an attack against the rear guard of the British force near Monmouth Court House. In action occurring on June 28, 1778, Lee's failure to perform resulted in a battlefield tongue lashing from an irate Washington, who personally halted the American retreat and helped to re-form the battle line. A day-long struggle ensued. Neither side emerged as the clear victor, but the British retreated under cover of night.

Lee was deeply stung by Washington's words and sent two letters demanding an apology from the commander and a court-martial to clear his name. Lee was found guilty of disobeying orders and insubordination and was removed from service for one year. This verdict was upheld by Congress in December 1778. Lee retired to his Virginia estate where he wrote letters attacking Washington and the Congress. He was officially dismissed from the army in 1780.

Lee's frequent criticisms of Washington offended many of the general's loyal supporters, including aide John Laurens, who challenged Lee to a duel. In the ensuing encounter, Lee was slightly wounded in the initial exchange of shots and only the intercession of Laurens' second, Alexander Hamilton, prevented further engagement. Lee's injury, however, prevented him from accepting a similar challenge from Anthony Wayne.

Lee later moved to Philadelphia and lived in obscurity until his death in a tavern in October 1782. His passing revived considerable public interest in his career. Washington and a host of other dignitaries attended the funeral. Lee's will stipulated that he not be buried in a churchyard, explaining that "I have kept so much bad company when living that I do not choose to continue it when dead."

For half a century she was the most important woman in the social circles of America. To this day she remains one of the best known and best loved ladies of the White House--though often referred to, mistakenly, as Dorothy or Dorothea.

She always called herself Dolley, and by that name the New Garden Monthly Meeting of the Society of Friends, in Piedmont, North Carolina, recorded her birth to John and Mary Coles Payne, settlers from Virginia. In 1769 John Payne took his family back to his home colony, and in 1783 he moved them to Philadelphia, city of the Quakers. Dolley grew up in the strict discipline of the Society, but nothing muted her happy personality and her warm heart.

John Todd, Jr., a lawyer, exchanged marriage vows with Dolley in 1790. Just three years later he died in a yellow-fever epidemic, leaving his wife with a small son.

By this time Philadelphia had become the capital city. With her charm and her laughing blue eyes, fair skin, and black curls, the young widow attracted distinguished attention. Before long Dolley was reporting to her best friend that "the great little Madison has asked...to see me this evening."

Although Representative James Madison of Virginia was 17 years her senior, and Episcopalian in background, they were married in September 1794. The marriage, though childless, was notably happy; "our hearts understand each other," she assured him. He could even be patient with Dolley's son, Payne, who mishandled his own affairs--and, eventually, mismanaged Madison's estate.

Discarding the somber Quaker dress after her second marriage, Dolley chose the finest of fashions. Margaret Bayard Smith, chronicler of early Washington social life, wrote: "She looked a Queen...It would be absolutely impossible for any one to behave with more perfect propriety than she did."

Blessed with a desire to please and a willingness to be pleased, Dolley made her home the center of society when Madison began, in 1801, his eight years as Jefferson's Secretary of State. She assisted at the White House when the President asked her help in receiving ladies, and presided at the first inaugural ball in Washington when her husband became Chief Executive in 1809.

Dolley's social graces made her famous. Her political acumen, prized by her husband, is less renowned, though her gracious tact smoothed many a quarrel. Hostile statesmen, difficult envoys from Spain or Tunisia, warrior chiefs from the west, flustered youngsters--she always welcomed everyone. Forced to flee from the White House by a British army during the War of 1812, she returned to find the mansion in ruins. Undaunted by temporary quarters, she entertained as skillfully as ever.

At their plantation Montpelier in Virginia, the Madison's lived in pleasant retirement until he died in 1836. She returned to the capital in the autumn of 1837, and friends found tactful ways to supplement her diminished income. She remained in Washington until her death in 1849, honored and loved by all. The delightful personality of this unusual woman is a cherished part of her country's history.

On October 21, 1799, in Marlborough, Elisabeth Bender married David Greenough (1774-1836), of Boston. David Greenough was the fourth of seven children born in Welfleet, Massachusetts, to John Greenough (1742-1781) and Mehitable Dillingham (1747-1798). John Greenough, a Yale graduate, taught school and operated a store in Welfleet, where his political sympathies were questioned during the Revolution after he admitted to selling tea. In 1781 Greenough moved his family to Boston, where he died in July of that year, when David Greenough was only seven. David Stoddard Greenough (1752-1826), his father's half brother became the guardian of David Greenough and his siblings, although their mother was still alive.

David Greenough became a builder and a real estate developer in Boston.7 Between 1810 and 1814, he built two houses on Colonnade Row, designed by the architect Charles Bulfinch (1763-1844), and in 1818 he was involved in the erection of a block of buildings with stone facades on Brattle Street.8 His transactions were noted frequently in the Boston records. For instance, in exchange for the purchase of part of a lot on West Street owned by the school house in 1814, Greenough was asked to build a new school house to replace the old one. On another occasion, Greenough was the leader of a petition to build a new market house near Dock Square. The petition was rejected in 1819 because "the rights and interests of the Town would be injuriously affected by the erection of any new Market in the vicinity of the old Market near Faneuil Hall by any individual citizens and for their private benefit. In addition to real estate, it appears that Greenough invested in ship building and in a cotton mill in Clinton.

Elisabeth and David Greenough had eleven children. The eldest daughter, Mehitable, died in infancy in October 1801, and the third child, Laura Ann, died at thirteen. They were the parents of the renowned sculptors Horatio Greenough (1805-1852), their fourth child, and Richard Saltonstall Greenough (1819-1904), their youngest. Their fifth child, Henry Greenough (1807-1883), was best known for his work as an architect, and their oldest son John Greenough (1801-1852) was a portrait and landscape painter. Although Elisabeth's daughter-in-law Francis Boott Greenough stated that Elisabeth had "neither knowledge nor appreciation of art," her sons wrote to her about art, and she was proud of their accomplishments. For instance, after Horatio Greenough's commission for James Fenimore Cooper, Chanting Cherubs (1828, un-located), arrived in Boston in May 1831, Elisabeth wrote to her son Henry in Florence, "Alfred no doubt has informed you how the Cherubs have been received; has he told you how much your mother admires them? Congratulate Horatio on his flattering prospects." Her letter also reported Washington Allston's comments to her in praise of the sculpture.

The Greenoughs moved frequently. In 1805 they resided at Green Street, and from about 1810 to 1819 they lived in the houses that David Greenough had built at Colonnade Row. In 1819 they moved to Jamaica Plain, where David Stoddard Greenough, Jr. (1787-1830), noted their social visits and business dealings in his diary. They moved back to Colonnade Row about 1824 and later moved to Chestnut Street and Beacon Street.

Elisabeth's granddaughter Laura Huntington Wagnière (b. 1849) described her grandmother as "a great lover of Nature, flowers, birds, and books. Her daughter-in-law Frances, however, indicated that Elisabeth "always tended to look on the dark side" and was "with the best intentions . . . subject to jealousies and suspicions," which made her "a thorn to herself, and those about her.

Elisabeth wrote poetry throughout her life, and near its close she had a small collection of her poems dating from 1798 until 1864 privately printed and published under the title Occasional Verses. She wrote "To Little Hetty" after the death of her first child in 1801 and "To Laura in Heaven" after her thirteen-year-old daughter died in 1816. In an untitled poem also lamenting the loss of her daughter, she announced that she would change the name of another daughter to Laura Ann so that, "when I hear her sisters call / That dear and well-known name / The sweet delusion I'll embrace / and think it is the same. Still mourning Laura's death two years later, she wrote "On Seeing Children on the Common" and "On Hearing my Bird Sing in Winter. Finding a measure of comfort in her spiritual beliefs, in 1838 she instructed the transcendentalists to "boast not of superior light, nor of some new-born sense" in her five-stanza poem "Transcendentalism." Some of her later poems reflect her thoughts on her own mortality and her faith in God. "On Seeing a Leaf Fall in Autumn" was dated two years before her death. In the final stanza she wrote, "Then hushed be every anxious thought, / Though we like vegetation die, / And this frail body turns to naught, / the Spirit soars to God on high.

Elisabeth's husband, David, died in Boston on July 27, 1836. A probate inventory revealed his real estate holdings totaled $149,000 and his personal estate $10,017.50, but his estate was heavily mortgaged. By 1845 Elisabeth had moved to Cambridge, where she remained in her son Henry's house while he and his family spent five years in Europe.

Elisabeth Bender Greenough died on January 11, 1866, at age ninety. Her obituary appeared the following week in the Boston Daily Evening Transcript." She was buried in Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, where her husband had been interred. A large marble monument contains the inscription "Elisabeth/wife of/David Greenough/Born Sept. 10th 1776/Died Jan. 11th 1866/Loved and Honored.

Analysis

Elisabeth Bender Greenough (Mrs. David Greenough) was painted on panel in the artist's bust-length format, which was very popular with his Boston patrons, but the portrait appears to have been cut down. For his bust portraits, Stuart positioned the sitter in front of either a neutral-colored wall or added grand manner elements to the background, like the red curtain and the bit of cloud-filled blue sky in Greenough's portrait. Elisabeth Bender Greenough (Mrs. David Greenough), however, is somewhat smaller than Stuart's other bust portraits, which were typically head-and-shoulder views of the sitter from above the elbows, as in the portrait Ann Frazier King (Mrs. William King) (about 1806, Maine State House Portrait Collection, Augusta). Greenough's portrait ends rather abruptly just below the bustline of her high-waisted black dress. On the back of the panel, there are drip marks on the top edge that descend from the presentation surface, but no drips mark the other edges, which suggests that the side and bottom edges may have been trimmed.

Stuart started a portrait of an unidentified man on the reverse of the panel of Elisabeth Bender Greenough (Mrs. David Greenough) and left it unfinished. Underneath the layer of dull yellow paint, infrared vidicon revealed the sitter's head turned to the viewer's left. Although the top of his head is bald, there is hair on the sides. His eyes, nose, and lips were roughly defined before the portrait was discarded and covered with yellow. It was not unusual for Stuart to leave a portrait unfinished. In some instances, Stuart's unfinished portraits were even completed by other artists. The 1828 inventory of Stuart's estate listed "8 unfinished sketches of Heads" in the front chamber of his house, including Sarah Wentworth Apthorp Morton (Mrs. Perez Morton). The hidden portrait sketch on the reverse of Elisabeth Bender Greenough (Mrs. David Greenough) demonstrates that at least one of Stuart's unfinished portraits was recycled and used for a new commission.

The circumstances of the commission of Greenough's portrait are not known, but Stuart was certainly a familiar name to the Greenough's. In 1825, when Horatio Greenough was a senior at Harvard, he entered a public competition to design the Bunker Hill Monument. Stuart was chairman of the Board of Artists and approved Greenough's model for an obelisk, although it was not his version that was eventually constructed. In his memorial tribute to Horatio Greenough, the author and critic Henry Tuckerman suggested that "Stuart's masterpieces" were an influence on the young sculptor. Horatio Greenough's acquaintance with the artist is documented in an 1828 letter to Samuel Morse, in which he predicted, just a few months before Stuart's death, that "Mr. Stuart I fear is going-"

By J. L. BELL

He is a Massachusetts writer who specializes in (among other things) the start of the American Revolution in and around Boston. He is particularly interested in the experiences of children in 1765-75. He has published scholarly papers and popular articles for both children and adults. He was consultant for an episode of History Detectives, and contributed to a display at Minute Man National Historic Park.

Abortion case in 1742 Connecticut

I didn't expect to stay so long on the topic of American Revolutionaries' religious views, but this morning I learned that Prof. Larry Cebula of Missouri Southern State has posted some more primary sources on the topic on a page called Faiths of the Founders.

Prof. Cebula is coming from an environment where many students have simply assumed the founders basically shared their own form of Christianity. To help them examine those assumptions, he's chosen several documents in which big-name founders express deistic and Unitarian views. Traditional eighteenth-century Anglicanism, Congregationalism, and Presbyterianism are therefore underrepresented relative to their dominance at the time. We should also remember the minority religions of the colonies: Quaker, Baptist, Shepardic Jewish, Moravian, Sandemanian, Native American, West African, &c. Finally, I think it might be too easy to assume that, say, a Presbyterian service of the 1800s would feel familiar to a Presbyterian today; customs and values have changed so much that it would probably be more like going into a completely new church or temple and trying to follow along.

Prof. Cebula also has a page of primary documents on A Colonial Abortion Drama. This case was first studied by Cornelia Hughes Dayton in a 1991 article for the William & Mary Quarterly. In 1742, Sarah Grosvenor of Pomfret, Connecticut, died, apparently from the effects of a combined medicinal-surgical abortion that had produced a miscarriage. Four years later, Grosvenor's sexual partner, Amasa Davis, and the abortion provider, Dr. John Hallowell of Killingley, were indicted for her murder.

Prof. Cebula has posted the grand jury indictment, written testimony, jury verdict, and notes on what became of the principal figures in the case. I won't give away the ending of the story since the point of his webpage is for visitors to use the documents to figure out what happened for themselves.

But here are some observations:

This example of abortion in colonial America would never have come to light without the court case. If Grosvenor had survived and/or if the families had decided to keep the situation private, there would have been no public record to examine. Davis and Hallowell were tried to killing Grosvenor, not for inducing the miscarriage.

It was quite common for couples like Grosvenor and Davis to conceive a child before marrying. Indeed, in the mid-1700s historians have counted 30% of New England couples' first children being born within seven months of their marriage. That number is considerably higher than for the late 1600s, telling me that the oppressive moral regime of the Puritans did affect people's private behavior.

In eighteenth-century New England, if a young unmarried woman became pregnant, the father-to-be was expected to marry her. Then they'd have as many more children as they could, with little said about the circumstances of the first pregnancy. In some cases, such as Ebenezer Richardson, the father-to-be couldn't marry the mother-to-be because he already had a wife. Amasa Davis was unusual in being free to marry Sarah Grosvenor, but refusing.

The four-year lag between Grosvenor's death and the legal move is intriguing-as is the jury's focus on Dr. Hallowell. In cases like these, I wonder if there was some knowledge in the community that didn't get into the legal record. For instance, had Grosvenor's family become upset by Davis's behavior in the years after she died? Had townspeople come to distrust Hallowell as a doctor? We'll never know.

"…one of the Greatest battles that Ever was fought in Amarrca…"

Major Henry Dearborn

The Revolutionary War is enshrined in American memory as the beginning of a new nation born in freedom. In this memory the conflict was quick and easy, the adversaries are little more than cartoon-like tin soldiers whose brightly colored uniforms make them ideal targets for straight-shooting American frontiersmen.

In actuality, the very year of Independence was a time of many military disasters for the fledgling republic; the first year of its existence was almost its last. New York was the stage for much of the drama that unfolded.

During the summer of 1776, a powerful army under British General Sir William Howe invaded the New York City area. His professional troops defeated and outmaneuvered General George Washington's less trained forces. An ill advised American invasion of Canada had come to an appalling end, its once confident regiments reduced to a barely disciplined mob beset by smallpox and pursuing British troops through the Lake Champlain Valley.

As 1776 ended, the cause for American Independence seemed all but lost. It was true that Washington's successful gamble at the battles of Trenton and Princeton kept hopes alive, but the British were still holding the initiative. Royal Garrisons held New York and its immediate environs, Newport, Rhode Island and Canada. Additionally the Royal Navy allowed the British to strike at will almost anywhere along the eastern seaboard.

In hopes of crushing the American rebellion before foreign powers might intervene, the British concocted a plan to invade New York from their base in Canada in 1777. Essentially, two armies would follow waterways into the Rebel territory, unite and capture Albany, New York. Once the town was in their possession, these British forces would open communications to the City of New York, and continue the campaign as ordered. It was believed that by capturing the Hudson River's head of navigation (Albany) and already holding its mouth (the City of New York), the British could establish their control of the entire river. Control of the Hudson could sever New England-the hot bed of the rebellion-from the rest of the colonies.

The architect of the plan, General John Burgoyne, commanded the main thrust through the Lake Champlain valley. Although the invasion had some initial success with the capture of Fort Ticonderoga, the realities of untamed terrain soon slowed the British triumphant advance into an agonizing crawl. Worse for the British, a major column en route to seek supplies in Vermont was overrun, costing Burgoyne almost irreplaceable 1000 men. Hard on the heels of this disaster, Burgoyne's contingent of Native Americans decided to leave, word came from the west that the second British column was stalled by the American controlled Fort Stanwix and that the main British army would not be operating near the city of New York. Although his plans were unraveling, Burgoyne refused to change his plans and collected enough supplies for a dash to Albany.

For the Americans, the British delays and defeats had bought them enough time to re-organize and reinforce their army. Under a new commander, General Horatio Gates, the American army established itself at a defensive position along the Hudson River called Bemis Heights. With fortifications on the flood plain and cannon on the heights, the position dominated all movement through the river valley. Burgoyne's army was entirely dependent upon the river to haul their supplies, and the American defenses were an unavoidable and dangerous obstacle.

Learning of the Rebels' position, Burgoyne attempted to move part of his army inland to avoid the danger posed by the American fortifications. On September 19th 1777, his columns collided with part of General Gates' army near the abandoned farm of Loyalist John Freeman. During the long afternoon, the British were unable to maintain any initiative or momentum. Pinned in place, they suffered galling American gunfire as they strove to hold their lines. Late in the day, reinforcements of German auxiliary troops turned the tide for Burgoyne's beleaguered forces. Although driven from the battlefield, the British had suffered heavy casualties and Gates' army still blocked his move south to Albany.

General Burgoyne elected to hold what ground he had and fortify his encampment, hoping for assistance from the City of New York. On October 7th, with supplies running dangerously low and options running out, Burgoyne attempted another flanking move. The expedition was noticed by the Rebels who fell upon Burgoyne's column. Through the fierce fighting the British and their allies were routed and driven back to their fortifications. At dusk, one position held by German troops, was overwhelmed by attacking Americans. Burgoyne had to withdraw to his inner works near the river and the following day tried to withdraw northward toward safety. Hampered by bad roads made worse by frigid downpours, the British retreat made only eight miles in two days to a small hamlet called Saratoga; Gates' army followed and surrounded Burgoyne and his army. With no other option Burgoyne capitulated on 17 October 1777.

The American victory at Saratoga was a major turning point in the war for Independence, heartening the supporters of independence and convincing France to enter in the war as an ally of the fledgling United States. It would be French military assistance that would keep the rebel cause from collapse and tip the balance at Yorktown, Virginia in 1781 - winning America its ultimate victory as a free and independent nation. The war also would reach to nearly every quarter of the globe as Spain and the Netherlands would become involved. But more importantly ideals of the rebel Americans would be exported as well, inspiring people throughout the world with the hope of liberties and freedom.

The preceding information was provided by the staff at the Saratoga National Historical Park.

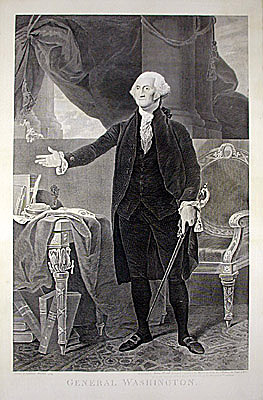

General Washington

Black-and-white engraving

London: ca. 1800 or later

Lower left: Painted by Gabriel Stuart 1797

Lower right: Engraved by James Heath Historical Engraver to his Majesty and to his Royal Highness the Prince of Wales from the original Picture in the Collection of the Marquis of Lansdowne (sic)

This portrait engraving is based upon the famous painting of George Washington by Gilbert Stuart in 1796. It is known as the Lansdowne Portrait, because it was a gift to the Marquis of Lansdowne, a British supporter of American independence, from Senator and Mrs. William Bingham of Pennsylvania. Washington is depicted as a stalwart representative of democracy, surrounded by objects metaphorically representing his public life. This is probably the best known portrait engraving by British printmaker James Heath, and was originally produced in 1800. The print is captioned, "Painted by Gabriel Stuart 1797," but this is incorrect, perhaps deliberately so -- James Heath produced this engraving without consulting Gilbert Stuart, who was distressed that Heath had violated his copyright, and complained publicly in an attempt to discredit the print. For the rest of his life, Stuart worried about unauthorized versions of his Washington portraits, and did successfully sue other copiers. Washington had died in 1799 and there was great demand in America for images of their national hero, and such prints sold well. The original painting is in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C., and an extensive explanatory text can be found on the Smithsonian web site. The print is also in their collection and can be viewed on their site.

James Heath was a London-based engraver in line and stipple. Heath studied under Joseph Collyer and established his career over an eight-year period engraving plates after Thomas Stothard for the Novelist's Magazine. He engraved book illustrations for many prominent publishers of the day, including John Boydell. He also re-engraved William Hogarth's plates and produced separately-issued prints after the works of renowned painters, the most celebrated of which was after John Singleton Copley's painting Death of Major Peirson. Heath's best-known portrait is probably his engraving after Gilbert Stuart's painting of George Washington (1800). He was made an associate engraver by the Royal Academy in 1791 and exhibited there from 1795 to 1834. From 1793 to 1834 he was Historical Engraver to the King.

Stuart did paint another set of the first five presidents. However, while that group was on loan to the Capitol in 1851, three of the portraits burned during a fire in the congressional library. Engraved prints of that set were enormously popular during the Federal period, earning the nickname "The American Kings."

Born in 1732 into a Virginia planter family, he learned the morals, manners, and body of knowledge requisite for an 18th century Virginia gentleman.

He pursued two intertwined interests: military arts and western expansion. At 16 he helped survey Shenandoah lands for Thomas, Lord Fairfax. Commissioned a lieutenant colonel in 1754, he fought the first skirmishes of what grew into the French and Indian War. The next year, as an aide to Gen. Edward Braddock, he escaped injury although four bullets ripped his coat and two horses were shot from under him.

From 1759 to the outbreak of the American Revolution, Washington managed his lands around Mount Vernon and served in the Virginia House of Burgesses. Married to a widow, Martha Dandridge Custis, he devoted himself to a busy and happy life. But like his fellow planters, Washington felt himself exploited by British merchants and hampered by British regulations. As the quarrel with the mother country grew acute, he moderately but firmly voiced his resistance to the restrictions.

When the Second Continental Congress assembled in Philadelphia in May 1775, Washington, one of the Virginia delegates, was elected Commander in Chief of the Continental Army. On July 3, 1775, at Cambridge, Massachusetts, he took command of his ill-trained troops and embarked upon a war that was to last six grueling years.

He realized early that the best strategy was to harass the British. He reported to Congress, "we should on all Occasions avoid a general Action, or put anything to the Risque, unless compelled by a necessity, into which we ought never to be drawn." Ensuing battles saw him fall back slowly, then strike unexpectedly. Finally in 1781 with the aid of French allies--he forced the surrender of Cornwallis at Yorktown.

Washington longed to retire to his fields at Mount Vernon. But he soon realized that the Nation under its Articles of Confederation was not functioning well, so he became a prime mover in the steps leading to the Constitutional Convention at Philadelphia in 1787. When the new Constitution was ratified, the Electoral College unanimously elected Washington President.

He did not infringe upon the policy making powers that he felt the Constitution gave Congress. But the determination of foreign policy became preponderantly a Presidential concern. When the French Revolution led to a major war between France and England, Washington refused to accept entirely the recommendations of either his Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, who was pro-French, or his Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton, who was pro-British. Rather, he insisted upon a neutral course until the United States could grow stronger.

To his disappointment, two parties were developing by the end of his first term. Wearied of politics, feeling old, he retired at the end of his second. In his Farewell Address, he urged his countrymen to forswear excessive party spirit and geographical distinctions. In foreign affairs, he warned against long-term alliances.

Washington enjoyed less than three years of retirement at Mount Vernon, for he died of a throat infection December 14, 1799. For months the Nation mourned him.

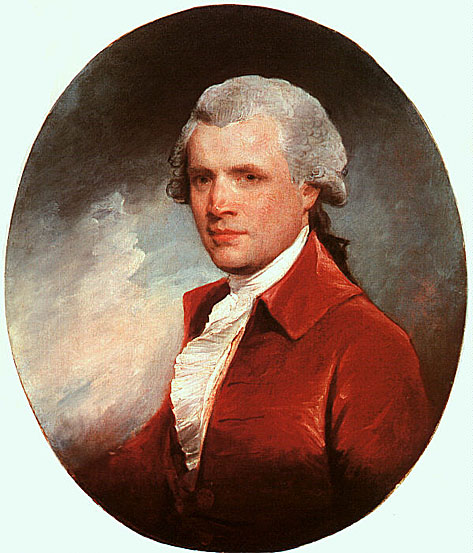

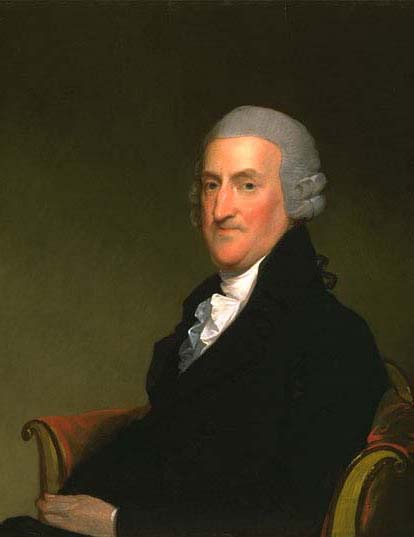

Although the second president was a patient sitter, the impish painter later delighted in telling a friend, "Isn't it like? Do you know what he is about to do? He is about to sneeze!" (Both the artist and the sitter habitually used snuff.)

In this sketch from life, soft brushstrokes merely suggest rustling movement and indistinct contours in the hair and lace. The portrait subtly expresses the inquisitive, analytic aspects of Adams' character; seated low in the composition, he confronts the viewer directly.

Adams was born in the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1735. A Harvard-educated lawyer, he early became identified with the patriot cause; a delegate to the First and Second Continental Congresses, he led in the movement for independence.

During the Revolutionary War he served in France and Holland in diplomatic roles, and helped negotiate the treaty of peace. From 1785 to 1788 he was minister to the Court of St. James's, returning to be elected Vice President under George Washington.

Adams' two terms as Vice President were frustrating experiences for a man of his vigor, intellect, and vanity. He complained to his wife Abigail, "My country has in its wisdom contrived for me the most insignificant office that ever the invention of man contrived or his imagination conceived."

When Adams became President, the war between the French and British was causing great difficulties for the United States on the high seas and intense partisanship among contending factions within the Nation.

His administration focused on France, where the Directory, the ruling group, had refused to receive the American envoy and had suspended commercial relations.

Adams sent three commissioners to France, but in the spring of 1798 word arrived that the French Foreign Minister Talleyrand and the Directory had refused to negotiate with them unless they would first pay a substantial bribe. Adams reported the insult to Congress, and the Senate printed the correspondence, in which the Frenchmen were referred to only as "X, Y, and Z."

The Nation broke out into what Jefferson called "the X. Y. Z. fever," increased in intensity by Adams's exhortations. The populace cheered itself hoarse wherever the President appeared. Never had the Federalists been so popular.

Congress appropriated money to complete three new frigates and to build additional ships, and authorized the raising of a provisional army. It also passed the Alien and Sedition Acts, intended to frighten foreign agents out of the country and to stifle the attacks of Republican editors.

President Adams did not call for a declaration of war, but hostilities began at sea. At first, American shipping was almost defenseless against French privateers, but by 1800 armed merchantmen and U.S. warships were clearing the sea-lanes.

Despite several brilliant naval victories, war fever subsided. Word came to Adams that France also had no stomach for war and would receive an envoy with respect. Long negotiations ended the quasi war.

Sending a peace mission to France brought the full fury of the Hamiltonians against Adams. In the campaign of 1800 the Republicans were united and effective, the Federalists badly divided. Nevertheless, Adams polled only a few less electoral votes than Jefferson, who became President.

On November 1, 1800, just before the election, Adams arrived in the new Capital City to take up his residence in the White House. On his second evening in its damp, unfinished rooms, he wrote his wife, "Before I end my letter, I pray Heaven to bestow the best of Blessings on this House and all that shall hereafter inhabit it. May none but honest and wise Men ever rule under this roof."

Adams retired to his farm in Quincy. Here he penned his elaborate letters to Thomas Jefferson. Here on July 4, 1826, he whispered his last words: "Thomas Jefferson survives." But Jefferson had died at Monticello a few hours earlier.

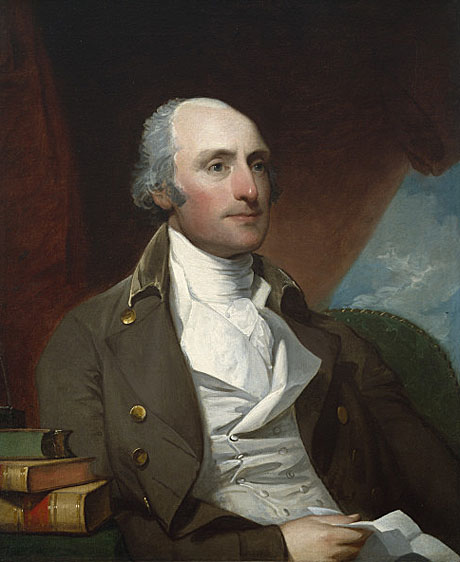

This powerful advocate of liberty was born in 1743 in Albemarle County, Virginia, inheriting from his father, a planter and surveyor, some 5,000 acres of land, and from his mother, a Randolph, high social standing. He studied at the College of William and Mary, then read law. In 1772 he married Martha Wayles Skelton, a widow, and took her to live in his partly constructed mountaintop home, Monticello.

Freckled and sandy-haired, rather tall and awkward, Jefferson was eloquent as a correspondent, but he was no public speaker. In the Virginia House of Burgesses and the Continental Congress, he contributed his pen rather than his voice to the patriot cause. As the "silent member" of the Congress, Jefferson, at 33, drafted the Declaration of Independence. In years following he labored to make its words a reality in Virginia. Most notably, he wrote a bill establishing religious freedom, enacted in 1786.

Jefferson succeeded Benjamin Franklin as minister to France in 1785. His sympathy for the French Revolution led him into conflict with Alexander Hamilton when Jefferson was Secretary of State in President Washington's Cabinet. He resigned in 1793.

Sharp political conflict developed, and two separate parties, the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans, began to form. Jefferson gradually assumed leadership of the Republicans, who sympathized with the revolutionary cause in France. Attacking Federalist policies, he opposed a strong centralized Government and championed the rights of states.

As a reluctant candidate for President in 1796, Jefferson came within three votes of election. Through a flaw in the Constitution, he became Vice President, although an opponent of President Adams. In 1800 the defect caused a more serious problem. Republican electors, attempting to name both a President and a Vice President from their own party, cast a tie vote between Jefferson and Aaron Burr. The House of Representatives settled the tie. Hamilton, disliking both Jefferson and Burr, nevertheless urged Jefferson's election.

When Jefferson assumed the Presidency, the crisis in France had passed. He slashed Army and Navy expenditures, cut the budget, eliminated the tax on whiskey so unpopular in the West, yet reduced the national debt by a third. He also sent a naval squadron to fight the Barbary pirates, who were harassing American commerce in the Mediterranean. Further, although the Constitution made no provision for the acquisition of new land, Jefferson suppressed his qualms over constitutionality when he had the opportunity to acquire the Louisiana Territory from Napoleon in 1803.

During Jefferson's second term, he was increasingly preoccupied with keeping the Nation from involvement in the Napoleonic wars, though both England and France interfered with the neutral rights of American merchantmen. Jefferson's attempted solution, an embargo upon American shipping, worked badly and was unpopular.

Jefferson retired to Monticello to ponder such projects as his grand designs for the University of Virginia. A French nobleman observed that he had placed his house and his mind "on an elevated situation, from which he might contemplate the universe."

He died on July 4, 1826.

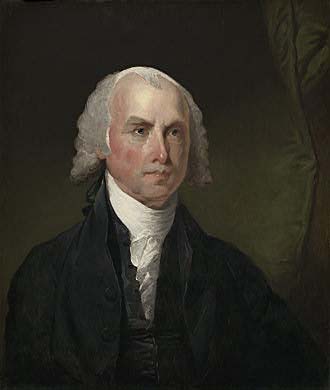

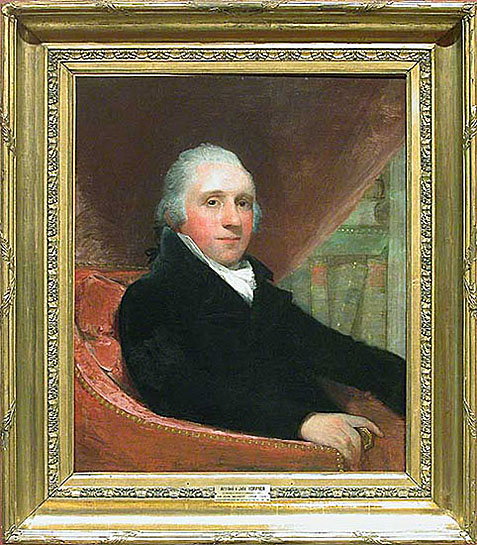

Born in 1751, Madison was brought up in Orange County, Virginia, and attended Princeton (then called the College of New Jersey). A student of history and government, well-read in law, he participated in the framing of the Virginia Constitution in 1776, served in the Continental Congress, and was a leader in the Virginia Assembly.

When delegates to the Constitutional Convention assembled at Philadelphia, the 36-year-old Madison took frequent and emphatic part in the debates.

Madison made a major contribution to the ratification of the Constitution by writing, with Alexander Hamilton and John Jay, the Federalist essays. In later years, when he was referred to as the "Father of the Constitution," Madison protested that the document was not "the off-spring of a single brain," but "the work of many heads and many hands."

In Congress, he helped frame the Bill of Rights and enact the first revenue legislation. Out of his leadership in opposition to Hamilton's financial proposals, which he felt would unduly bestow wealth and power upon northern financiers came the development of the Democrat-Republican, or Jeffersonian, Party.

As President Jefferson's Secretary of State, Madison protested to warring France and Britain that their seizure of American ships was contrary to international law. The protests, John Randolph acidly commented, had the effect of "a shilling pamphlet hurled against eight hundred ships of war."

Despite the unpopular Embargo Act of 1807, which did not make the belligerent nations change their ways but did cause a depression in the United States, Madison was elected President in 1808. Before he took office the Embargo Act was repealed.

During the first year of Madison's Administration, the United States prohibited trade with both Britain and France; then in May, 1810, Congress authorized trade with both, directing the President, if either would accept America's view of neutral rights, to forbid trade with the other nation.

Napoleon pretended to comply. Late in 1810, Madison proclaimed non-intercourse with Great Britain. In Congress a young group including Henry Clay and John C. Calhoun, the "War Hawks," pressed the President for a more militant policy.

The British impressment of American seamen and the seizure of cargoes impelled Madison to give in to the pressure. On June 1, 1812, he asked Congress to declare war.

The young Nation was not prepared to fight; its forces took a severe trouncing. The British entered Washington and set fire to the White House and the Capitol.

But a few notable naval and military victories, climaxed by Gen. Andrew Jackson's triumph at New Orleans, convinced Americans that the War of 1812 had been gloriously successful. An upsurge of nationalism resulted. The New England Federalists who had opposed the war--and who had even talked secession--were so thoroughly repudiated that Federalism disappeared as a national party.

In retirement at Montpelier, his estate in Orange County, Virginia, Madison spoke out against the disruptive states' rights influences that by the 1830's threatened to shatter the Federal Union. In a note opened after his death in 1836, he stated, "The advice nearest to my heart and deepest in my convictions is that the Union of the States be cherished and perpetuated."

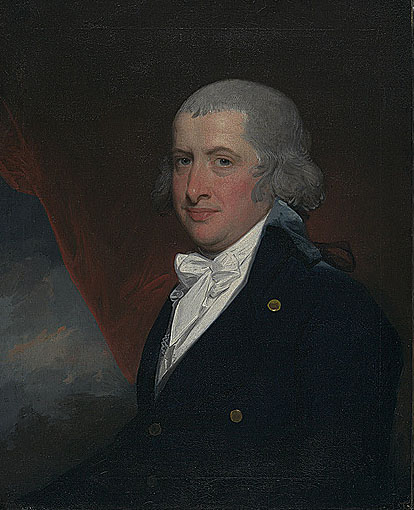

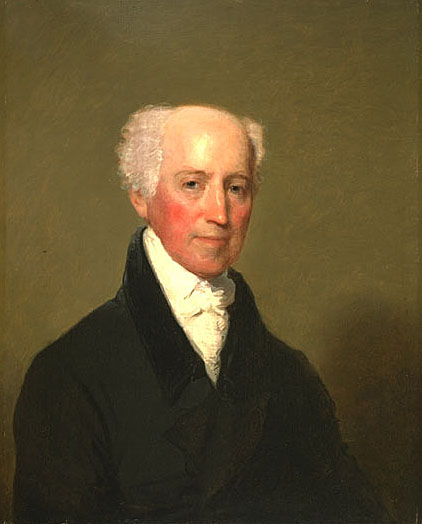

"He is tall and well formed. His dress plain and in the old style.... His manner was quiet and dignified. From the frank, honest expression of his eye ... I think he well deserves the encomium passed upon him by the great Jefferson, who said, 'Monroe was so honest that if you turned his soul inside out there would not be a spot on it.' "

Born in Westmoreland County, Virginia, in 1758, Monroe attended the College of William and Mary, fought with distinction in the Continental Army, and practiced law in Fredericksburg, Virginia.

As a youthful politician, he joined the anti-Federalists in the Virginia Convention which ratified the Constitution, and in 1790, an advocate of Jeffersonian policies, was elected United States Senator. As Minister to France in 1794-1796, he displayed strong sympathies for the French cause; later, with Robert R. Livingston, he helped negotiate the Louisiana Purchase.

His ambition and energy, together with the backing of President Madison, made him the Republican choice for the Presidency in 1816. With little Federalist opposition, he easily won re-election in 1820.

Monroe made unusually strong Cabinet choices, naming a Southerner, John C. Calhoun, as Secretary of War, and a northerner, John Quincy Adams, as Secretary of State. Only Henry Clay's refusal kept Monroe from adding an outstanding Westerner.

Early in his administration, Monroe undertook a goodwill tour. At Boston, his visit was hailed as the beginning of an "Era of Good Feelings." Unfortunately these "good feelings" did not endure, although Monroe, his popularity undiminished, followed nationalist policies.

Across the facade of nationalism, ugly sectional cracks appeared. A painful economic depression undoubtedly increased the dismay of the people of the Missouri Territory in 1819 when their application for admission to the Union as a slave state failed. An amended bill for gradually eliminating slavery in Missouri precipitated two years of bitter debate in Congress.

The Missouri Compromise bill resolved the struggle, pairing Missouri as a slave state with Maine, a Free State, and barring slavery north and west of Missouri forever.

In foreign affairs Monroe proclaimed the fundamental policy that bears his name, responding to the threat that the more conservative governments in Europe might try to aid Spain in winning back her former Latin American colonies. Monroe did not begin formally to recognize the young sister republics until 1822, after ascertaining that Congress would vote appropriations for diplomatic missions. He and Secretary of State John Quincy Adams wished to avoid trouble with Spain until it had ceded the Floridas, as was done in 1821.

Great Britain, with its powerful navy, also opposed re-conquest of Latin America and suggested that the United States join in proclaiming "hands off." Ex-Presidents Jefferson and Madison counseled Monroe to accept the offer, but Secretary Adams advised, "It would be more candid ... to avow our principles explicitly to Russia and France, than to come in as a cock-boat in the wake of the British man-of-war."

Monroe accepted Adams's advice. Not only must Latin America be left alone, he warned, but also Russia must not encroach southward on the Pacific coast. ". . . The American continents," he stated, "by the free and independent condition which they have assumed and maintain, are henceforth not to be considered as subjects for future colonization by any European Power." Some 20 years after Monroe died in 1831; this became known as the Monroe Doctrine.

In March, 1743, Brant was born at Cuyahoga Ohio Country on the banks of the Cuyahoga River, near present-day Akron, Ohio. This was during the hunting season when Mohawks traveled to the area. He was named Thayendanegea, which can mean two wagers (sticks) bound together for strength, or possibly "he who places two bets." He was a Mohawk of the Wolf Clan (his mother's clan). Fort Hunter church records indicate that his parents were Christians and their names were Peter and Margaret Tehonwaghkwangearahkwa. Peter died before 1753. Other sources cite the father's name as Nickus Kanagaradankwa.

His mother Margaret, or Owandah, the niece of Tiaogeara, a Caughnawaga sachem, took Joseph and his older sister Mary (known as Molly) to Canajoharie, on the Mohawk River in east-central New York, where they had lived before her family moved to the Ohio River. His mother remarried on 9 September 1753 in Fort Hunter (Church of England) a widower named Brant Canagaraduncka, who was a Mohawk sachem. Her new husband's grandfather was Sagayendwarahton, or "Old Smoke," who visited England in 1710. The marriage bettered Margaret's fortunes and the family lived in the best house in Canajoharie, but it conferred little status on her children, as Mohawk titles descended through the female line. However, Brant's stepfather was also a friend of William Johnson, who was to become General Sir William Johnson, Superintendent for Northern Indian Affairs. During Johnson's frequent visits to the Mohawks he always stayed at the Brant's house. Johnson married Joseph's sister, Molly.

Starting at about age 15, Brant took part in a number of French and Indian War expeditions, including James Abercrombie's 1758 invasion of Canada via Lake George, William Johnson's 1759 Battle of Fort Niagara, and Jeffery Amherst's 1760 siege of Montreal via the St. Lawrence River. He was one of 182 Indians who received a silver medal for good conduct.

In 1761, Johnson arranged for three Mohawks including Joseph to be educated at Eleazar Wheelock's Moor's Indian Charity School in Connecticut, the forerunner of Dartmouth College, where he studied under the guidance of the Reverend Eleazar Wheelock. Wheelock wrote Brant was "of a sprightly genius, a manly and gentle deportment, and of a modest, courteous and benevolent temper". Brant learned to speak, read, and write English. Brant met Samuel Kirkland at the school. In 1763, Johnson prepared to place Brant at King's College in New York City, but the outbreak of Pontiac's Rebellion upset these plans and Brant returned home. After Pontiac's rebellion Johnson thought it was not safe for Brant to return to the school.

In March 1764, Brant participated in one of the Iroquois war parties that attacked Delaware Indian villages in the Susquehanna and Chemung valleys. They destroyed three good-sized towns and burned 130 houses and killed their cattle. No enemy warriors were even seen.

On July 22, 1765, he married Peggie (also known as Margaret) in Canajoharie. Peggie was a white captive sent back from western Indians and said to be the daughter of a Virginia gentleman. They moved into Brant's parent's house and when his father died in the mid-1760s the house became Joseph's. He owned a large and fertile farm of 80 acres near the village of Canajoharie on the south shore of the Mohawk. He raised corn, kept cattle, sheep, horses, and hogs. He also kept a small store. Brant dressed in "the English mode" wearing "a suit of blue broad cloth". With Johnson's encouragement the Mohawk's made Brant a war chief and their primary spokesman. In March, 1771 his wife died from consumption.

In the spring of 1772, he moved to Fort Hunter to live with the Reverend John Stuart. He became Stuart's interpreter, teacher of Mohawk, and collaborated with him in translating the Anglican catechism and the Gospel of Mark into the Mohawk language. Brant became a lifelong Anglican.

In 1773, Brant moved back to Canajoharie and married Peggie's half-sister Susanna.

Brant spoke at least three and possibly all of the Six Nations languages. He was a translator for the department of Indian affairs since at least 1766 and in 1775, was appointed as departmental secretary with the rank of Captain for the new British Superintendent for Northern Indian affairs, Guy Johnson. In May, 1775 he fled the Mohawk valley with Guy Johnson and most of the Indian warriors from Canajoharie to Canada, arriving in Montreal on July 17. His wife and children went to Onoquaga. On November 11, 1775, Guy Johnson took Brant along with him when he traveled to London. Brant hoped to get the Crown to address past Mohawk land grievances, and the government promised the Iroquois people land in Canada if he and the Iroquois nations would fight on the British side. In London, Brant became a celebrity, and was interviewed for publication by James Boswell. While in public he carefully dressed in the Indian style. He also became a Mason, and received his apron personally from king George III.

Brant returned to Staten Island, New York in July 1776 and immediately became involved with Howe's forces as they prepared to retake New York. Although the details of his service that summer and fall were not officially recorded, he was said to have distinguished himself for bravery, and it has been deduced that he was with Clinton, Cornwallis, and Percy in the flanking movement at Jamaica Pass in the Battle of Long Island in August 1776. It was at this time that he embarked on a lifelong relationship with Lord Percy, later Duke of Northumberland, the only lasting friendship he shared with a white man.

In November, Brant left New York City travelling northwest through American held territory. Disguised, traveling at night and sleeping during the day, he reached Onoquaga where he met up with his family. At the end of December he was at Fort Niagara. He traveled from village to village in the confederacy urging the Iroquois to abandon neutrality and to enter the war on the side of the British. The Iroquois balked at Brant's plans because the full council of the Six Nations had previously decided on a policy of neutrality and had signed a treaty of neutrality at Albany in 1775, and also because they considered Brant a minor war chief from a relatively weak people, the Mohawks. Frustrated, Brant freelanced by heading in the spring to Onoquaga to conduct war his way. Few Onoquaga villagers joined him, but in May he was successful in recruiting Loyalists who wished to strike back. This group became known as Brant's Volunteers. In June, he led them to Unadilla to obtain supplies. At Unadilla, he was confronted by 380 men of the Tryon County militia led by Nicholas Herkimer. Herkimer requested that the Iroquois remain neutral while Brant said the Indians owed their loyalty to the King.

In July, 1777 the Six Nations council decided to abandon neutrality and to enter the war on the British side. Brant was not present at this council. Sayenqueraghta and Cornplanter were named to be the war chiefs of the confederacy. Brant had previous been made a war chief of the Mohawk's the other major Mohawk war chief was John Deseronto.

In July, Brant led his Volunteers north to link up with St. Leger at Fort Oswego. In August 1777, Brant played a major role at the Battle of Oriskany in support of a major offensive led by General John Burgoyne. After St. Leger's retreat, Brant travelled to Burgoyne's main army and told him the news of St. Leger's retreat from Fort Stanwix. Burgoyne's restrictions on native warfare caused Brant to depart for Fort Niagara where he spent the winter planning the next years campaign. His wife Susanna likely died at Fort Niagara that winter.

In April 1778, Brant returned to Onoquaga, becoming the most active partisan commander engaging in raids mostly with his Volunteers on the Americans, stealing their cattle, burning their houses, and killing many. On May 30, he led an attack on Cobleskill (Battle of Cobleskill) and in September, along with Captain William Caldwell, he led a mixed force of Indians and Loyalists in a raid on German Flatts.

In October, 1778, Continental soldiers and local militia attacked Brant's base of Onoquaga while Brant's Volunteers were away on a raid. The American commander described Onoquaga as "the finest Indian town I ever saw; on both sides of the river there was about 40 good houses, square logs, shingles and stone chimneys, good floors, glass windows". The soldiers burned the houses, killed the cattle, chopped down the apple trees, spoiled the growing corn crop, and killed some native children they found in the corn fields. On November 11, 1778 Brant was a leader in the attack in the Cherry Valley massacre.