Paulo Veronese

Italian Renaissance Painter

1528 - 1588

Self Portrait of Paulo Veronese

Paolo Veronese was an Italian painter of the Renaissance in Venice, famous for paintings such as The Wedding at Cana and The Feast in the House of Levi. He adopted the name Paolo Cagliari or Paolo Caliari, and became known as "Veronese" from his birthplace in Verona.

Veronese, Titian, and Tintoretto constitute the triumvirate of pre-eminent Venetian painters of the late Renaissance (16th century). Veronese is known as a supreme colorist, and for his illusionistic decorations in both fresco and oil. His most famous works are elaborate narrative cycles, executed in a dramatic and colorful Mannerist style, full of majestic architectural settings and glittering pageantry. His large paintings of biblical feasts executed for the refectories of monasteries in Venice and Verona are especially notable. His brief testimony with the Inquisition is often quoted for its insight into contemporary painting technique.

The census in Verona attests that Veronese was born some time in 1528 to a stonecutter named Gabriele, and his wife Catherina. By the age of fourteen Veronese apprenticed with the local master Antonio Badile, and perhaps with Giovanni Francesco Caroto. An altarpiece painted by Badile in 1543 includes striking passages that were most likely the work of his fifteen-year-old apprentice; Veronese's precocious gifts soon surpassed the level of the workshop, and by 1544 he was no longer residing with Badile. Though trained in the culture of Mannerism then popular in Parma, he soon developed his own preference for a more radiant palette.

He then moved briefly to Mantua in 1548 (where he created frescoes in that city's Duomo) before arriving in Venice in 1553. His first Venetian commission was a Sacra Conversazione from San Francesco della Vigna (ca.1552). In 1553, he obtained his first state commission, the fresco decoration of the Sala dei Cosiglio dei Dieci (the Hall of the Council of Ten) and the adjoining Sala dei Tre Capi del Consiglio. He then painted a History of Esther in the ceiling for the Church of San Sebastiano. It was his ceiling paintings for San Sebastiano, the Doge's Palace, and the Marciana Library, (the last for which Titian awarded him a prize), that established him as a master among his Venetian contemporaries. Already these works indicate Veronese's mastery for referencing both the subtle foreshortening of the figures of Correggio and the heroism of those by Michelangelo.

Paintings in the Church of San Sebastiano (1555-65)

by Paolo Veronese

Veronese painted a number of important works in the church which gradually, with its unassuming façade half hidden, was transformed into a radiant showcase of Veronese's art. Almost the whole of the available space inside is covered with paintings: in both fresco and oils, they cover the altars, organ loft, presbytery, ceiling and tribune. Even the friezes and other minor details are decorated. Veronese devoted special care to the decoration of the presbytery of the church, which has two long, dynamic paintings on the sides (Saints Mark and Marcellinus Being Led to Martyrdom; Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian) and a splendid painting on the high altar (Virgin and Child Enthroned with Saints).

The cycle of stories of Saint Sebastian can be compared in its great breadth and the many years spent on its execution to Tintoretto's grandiose painting cycle in the Scuola Grande di San Rocco. In the end Veronese chose to be buried here.Quoted From: Paintings in the church of San Sebastiano (1555-65)

Church of San Sebastiano View of the Façade 1505-48

This church was built by Antonio Abbondi (called Scarpagnino) between 1505 and 1548. The plain exterior fails to suggest the rich paintings inside or even the architecturally interesting interior. Veronese painted a number of important works in the church which gradually, with its unassuming façade half hidden, was transformed into a radiant showcase of Veronese's art.

Quoted From: Church of San Sebastiano View of the Façade

Paintings in the Chancel of San Sebastiano

by Paolo Veronese

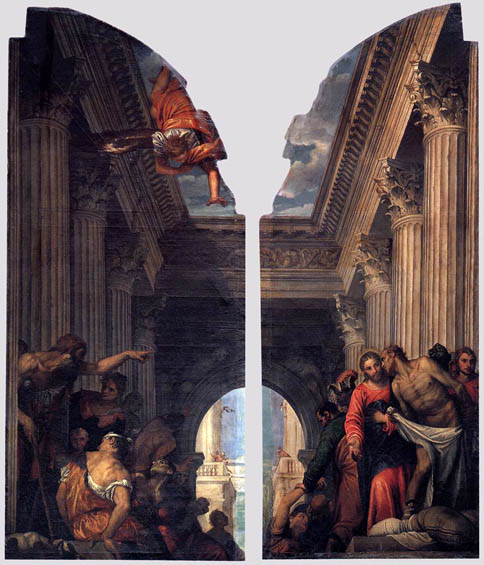

Saints Mark and Marcellinus Being Led to Martyrdom ca 1565

This painting is on the wall of the chancel (presbytery) of the church of San Sebastiano.

The Golden Legend of Jacopo da Voragine tells the story of the brothers Mark and Marcellinus and the events before their execution in great detail. The attempts by their despairing parents to get the two martyrs, strengthened in their faith by Saint Sebastian, to change their minds and abandon their faith is the subject of the crowded scene, which sticks very closely to the textual source. Idealized architecture conforming to the forms of Palladio and Sansovino provides the setting for the dramatic event. According to Ridolfi, the two paintings intended for the side walls of the "presbytery" were completed in 1565. This seems a credible date, and fits well with the report that Federico Zuccaro, who spent two and a half years in Venice from 1563, made drawings from both works.

Quoted From: Saints Mark and Marcellinus Being Led to Martyrdom

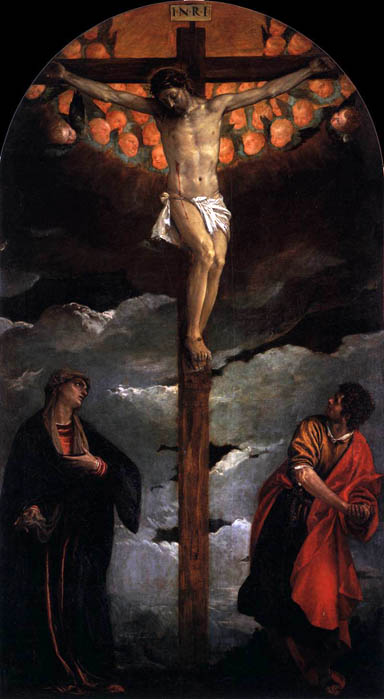

Virgin and Child Enthroned with Saints 1564-65

This painting is on the altar of the chancel (presbytery) of the church of San Sebastiano. The saints represented in the lower section of the painting are John the Baptist, Catherine, Elizabeth, Sebastian, Francis and Peter.

The altarpiece for the choir of the church of San Sebastiano was presumably painted at the same time as the two lateral canvases in the gallery (Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian, and Martyrdom of Saints Mark and Marcellinus). In doing the preliminary drawing for the architecture of the retable, Veronese worked once again as an architectural designer. The two female saints honor the memory of the founder Catharina Cornaro and her executrix Liza Querini. Veronese's biographer Ridolfi, writing in 1648, thought he could discern the portrait of the client, Fra Bernardo Torlioni, in the figure of Saint Francis.

Quoted From: Virgin and Child Enthroned with Saints

Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian: ca 1565

This painting is on the wall of the chancel (presbytery) of the church of San Sebastiano.

Veronese devoted special care to the decoration of the presbytery of the church, which has two long, dynamic paintings on the sides (Saints Mark and Marcellinus Being Led to Martyrdom; Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian) and a splendid painting on the high altar (Virgin and Child Enthroned with Saints).

This scene of the martyrdom of Saint Sebastian is unusual in that the saint is not shown pierced with arrows but in an earlier moment of his martyrdom, when he is stripped and flogged. Having miraculously survived the torment of the arrows in the altarpiece with the saint on the column, the resolute Sebastian repeats his confession of the Christian faith. This time, he will not escape the supreme sacrifice of martyrdom. Lighting and backlighting indicate grace and salvation.

Quoted From: Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian

Paintings in the Nave of San Sebastiano

by Paolo Veronese

Esther Crowned by Ahasuerus: 1556

The picture shows one of the three large paintings on the ceiling of the nave of the church of San Sebastiano: Esther Crowned by Ahasuerus (rectangular, in the center), The Triumph of Mordecai (oval), and The Banishment of Vashti (oval).

The strict diagonal composition offers a wealth of narrative detail, and like all other pictures in the series, takes into account the di sotto in su angle of vision, with its foreshortened perspectives, which pervades the space. The pictorial architecture provides a formal link between the pictorial fields. Columns, cornice and roof terraces form a continuous axis running through all three pictorial fields.

Technically, the light reflections on Haman's armor are particularly delicate: on closer inspection, they break up into spots of paint.Quoted From: Esther Crowned by Ahasuerus 1556

The Triumph of Mordecai: 1556

The picture shows one of the three large paintings on the ceiling of the nave of the church of San Sebastiano: Esther Crowned by Ahasuerus (rectangular, in the center), The Triumph of Mordecai (oval), and The Banishment of Vashti (oval).

This ceiling painting above the entrance to the presbytery illustrating Mordecai's triumph over the conspirator Haman represents a dramatic climax. With Haman and his black steed about to fall, Mordecai, with the insignia of royalty, triumphs on his white horse.

Haman has tried in vain to get the king to execute Mordecai, but is instead instructed to take Mordecai in state round the city on horseback. Esther and Ahasuerus watch the triumphal procession from the roof terrace of the royal palace.

Quoted From: The Triumph of Mordecai

The Banishment of Vashti: 1556

The picture shows one of the three large paintings on the ceiling of the nave of the church of San Sebastiano: Esther Crowned by Ahasuerus (rectangular, in the center), The Triumph of Mordecai (oval), and The Banishment of Vashti (oval).

The interpretation of this pictorial subject is controversial. Veronese's biographer Carlo Ridolfi and subsequent authors identified the picture as Esther confronting Ahasuerus, but a different interpretation is now more widely accepted. Only when the Persian king Ahasuerus had repudiated his disobedient wife Vashti did he choose Esther as his wife. This scene is the moment of repudiation. Relieved of her crown, Vashti leaves the royal palace with her retinue.

Quoted From: The Banishment of Vashti

Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian: 1558

Veronese painted the frescoes on the upper part of the Nave of San Sebastiano between March and September 1558. The main pictures here are representing Saint Sebastian Reproving Diocletian and the Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian. Painted architecture plays a preponderant role in these paintings: a mock portico with columns, niches and windows frames them. They are treated like theatrical scenery.

Quoted From: Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian

Saint Sebastian Reproving Diocletian: 1558

Three Archers: 1558

This fresco is part of the decoration of the upper part of the Nave in the church of San Sebastiano.

Quoted From: Three Archers

Monk with a Black Boy: 1558

This fresco is part of the decoration of the upper part of the Nave in the church of San Sebastiano.

Quoted From: Monk with a Black Boy

Saint Sebastian: 1558

Annunciation: 1558

The Announcing Angel and the Virgin of the Annunciation, with their limpid colors and iridescent vibrations, are painted on the pendentives of the triumphal arch that leads into the presbytery.

Quoted From: Annunciation

Presentation in the Temple: 1560

This scene adorns the outside wings of the carved organ of San Sebastiano. Parts of the figurative composition largely repeat an earlier picture on the same subject in Dresden. Here, the structure is much more clearly articulated and harmonious and enclosed by a large round arch. A typical feature is the introduction of various subsidiary figures required less for the event itself than for formal reasons. Also, Veronese delighted in using painterly means to explore certain movements or the qualities of the colour and appearance of expensive materials.

Quoted From: Presentation in the Temple

Healing of the Lame Man at the Pool of Bethesda: 1560

When opened, the painted wings of the organ of San Sebastiano show an interior court surrounded by Corinthian colonnades. The latter allude to the mention of five porches around the pool in Jerusalem in the story as told in St. John 5:1-8. In it "lay a great multitude of sick folk, of blind, halt and withered", is waiting for the angel who "went down at a certain season into the pool and troubled the water". The first person to enter the water after the "stirring" was cured. The depiction is among the miracles of Christ: with the words, "Rise, take up thy bed and walk", he heals a lame man who is always too late to reach the water. Veronese's accommodation of the throng of moving figures to the architecture from the depth to the foreground is masterly.

Quoted From: Healing of the Lame Man at the Pool of Bethesda

Coronation of the Virgin: 1555

This ceiling painting in the sacristy of San Sebastiano has an unusual iconography compared with older depictions. Mary is being crowned by Christ, while God the Father touches His Son's shoulder with his left hand. The date of completion of the ceiling painting is recorded in a book in one of the four corner tondos held by a winged angel. The inscription reads: M.D.L.V./ DIE XXIII/ NOVEMBER (November 23, 1555).

Quoted From: Coronation of the Virgin 1555

Paintings in the Chapel of Our Lady of the Rosary, Basilica dei Santi Giovanni e Paolo (1558-80)

by Paolo VERONESE

The Chapel of Our Lady of the Rosary was destroyed by fire in 1867. The gilded wooden ceiling with its paintings by Tintoretto, Palma Giovane and Leandro Corona, as well as 34 other paintings displayed on the walls were lost. The restored chapel was reopened only in 1959. In the new carved ceiling of the nave, three oval paintings by Veronese, which were once in the deconsecrated church of the Umiltà on the Zattere, were inset: the Adoration of the Shepherds, the Assumption, and the Annunciation. The walls are decorated with many paintings from the 16th-17th centuries, among them another version of the Adoration of the Shepherds by Veronese. The ceiling of the chancel of the chapel contains works by Veronese coming from the deconsecrated church of San Nicolò in Lattuga.

Quoted From: Paintings in the Chapel of Our Lady of the Rosary

Adoration of the Shepherds: 1558

The Chapel of Our Lady of the Rosary was destroyed by fire in 1867. The restored chapel was reopened only in 1959. In the new carved ceiling of the Nave, three oval paintings by Veronese, which were once in the deconsecrated church of the Umiltà on the Zattere, were inset: the Adoration of the Shepherds, the Assumption, and the Annunciation. They are works of very high chromatic quality and great inventiveness of composition, and can be considered to be on the same level as the scenes he painted for the ceiling of the Nave in San Sebastiano.

Quoted From: Adoration of the Shepherds

Adoration of the Shepherds: 1558 Two

Assumption: 1558

Assumption: 1558 Two

Annunciation: 1558

Annunciation: 1558 Three

Adoration of the Magi: 1582

The Chapel of Our Lady of the Rosary was destroyed by fire in 1867. The restored chapel was reopened only in 1959. The new carved ceiling of the Nave continues to the presbytery and includes other paintings by Veronese. In the center, there is the quatrefoil Adoration of the Magi, at the sides the Four Evangelists. These paintings come from the deconsecrated church of Nicolò in Lattuga.

Quoted From: Adoration of the Magi

Adoration of the Shepherds

In addition to the oval ceiling painting Adoration of the Shepherds, another, rectangular version of the same subject by Veronese is displayed on the end wall of the Chapel of Our Lady of the Rosary.

Quoted From: Adoration of the Shepherds

By 1556 Veronese was commissioned to paint the first of his monumental banquet scenes, the Feast in the House of Simon, which would not be concluded until 1570. However, owing to its scattered composition and lack of focus, it was not his most successful refectory mural. In the late 1550's, during a break in his work for San Sebastiano, Veronese decorated the Villa Barbaro in Maser, a newly-finished building by the architect Andrea Palladio. The frescoes were designed to unite humanistic culture with Christian spirituality; wall paintings included portraits of the Barbaro family, and the ceilings opened to blue skies and mythological figures. Veronese's decorations employed complex perspective and trompe l'oeil, and resulted in a luminescent and inspired visual poetry. The encounter between architect and artist was a triumph.

The Wedding at Cana, painted in 1562-1563, was also collaboration with Palladio. It was commissioned by the Benedictine monks for the San Giorgio Maggiore Monastery, on a small island across from Saint Mark's, in Venice. The contract insisted on the huge size (to cover 66 square meters), and that the quality of pigment and colors should be of premium quality. For example, the contract specified that the blues should contain the precious mineral lapis-lazuli. The contract also specified that the painting should include as many figures as possible. There are three hundred portraits (including portraits of Titian, Tintoretto, and Veronese himself) staged upon a canvas surface nearly ten meters wide. The scene, taken from the New Testament Book of John, II, 1-11, represents the first miracle performed by Jesus, the making of wine from water, at a marriage in Cana, Galilee. The foreground celebration, a frieze of figures painted in the most shimmering finery, is flanked by two sets of stairs leading back to a terrace, Roman colonnades, and a brilliant sky.

In the refectory paintings, as in The Family of Darius before Alexander (1565-1570), Veronese arranged the architecture to run mostly parallel to the picture plane, accentuating the processional character of the composition. The artist's decorative genius was to recognize that dramatic perspectival effects would have been tiresome in a living room or chapel, and that the narrative of the picture could best be absorbed as a colorful diversion. These paintings offer little in the representation of emotion; rather, they illustrate the carefully composed movement of their subjects along a primarily horizontal axis. Most of all they are about the incandescence of light and color. The exaltation of such visual effects may have been a reflection of the artist's personal well-being, for in 1565 Veronese married Elena Badile, the daughter of his first master, and by whom he would eventually have four sons and a daughter.

In 1573 Veronese completed the painting which is now known as the Feast in the House of Levi for the rear wall of the refectory of the Basilica di Santi Giovanni e Paolo. The painting was originally intended as a depiction of the Last Supper, designed to replace a canvas by Titian that had been lost in a fire. It measured more than five meters high and over twelve meters wide, depicted another Venetian celebration and was a culmination of his banquet scenes, which this time included not only the Last Supper, but also German soldiers, comic dwarves, and a variety of animals; in short, the exotica which were standard to his narratives. Even as Veronese's use of color attained greater intensity and luminosity, his attention to narrative, human sentiment, and a more subtle and meaningful physical interplay between his figures became evident.

That the subject was indeed a Last Supper, and then some, was not lost on the Inquisition. A decade earlier the monks who commissioned the Wedding at Cana had requested that the artist squeeze the maximum number of figures into the painting, but the Counter-Reformation had since exerted its influence in Venice, and in July of 1573 Veronese was summoned to explain the inclusion of extraneous and indecorous details in the painting.

The tone of the hearing itself was cautionary rather than punitive; Veronese explained that "we painters take the same liberties as poets and madmen", and rather than repaint the picture, he simply and pragmatically retitled it to the less sacramental version by which it is known today.

In addition to the ceiling creations and wall paintings, Veronese also produced altarpieces (The Consecration of Saint Nicholas, 1561-2, London's National Gallery, paintings on mythological subjects (Venus and Mars, 1578, New York Metropolitan Museum of Art), and portraits (Portrait of a Lady, 1555, Louvre). A significant number of compositional sketches in pen, ink and wash, figure studies in chalk, and chiaroscuro modelli and ricordi are in circulation. Veronese was one of the first painters whose drawings were sought by collectors during his lifetime.

He headed a family workshop, including his brother Benedetto, sons Carlo and Gabriele, which remained active after his death in Venice in 1588. Among his pupils were his contemporary Giovanni Battista Zelotti and later Giovanni Antonio Fasolo and Luigi Benfatto (also called dal Friso; 1559-1611).

In 1648 Carlo Ridolfi wrote of the Feast in the House of Levi that it "gave rein to joy, made beauty majestic, made laughter itself more festive".

A modern assessment of Veronese's achievement by Sir Lawrence Gowing is worth quoting at length:

The French had no doubts, as the critic Théophile Gautier wrote in 1860, that Veronese was the greatest colorist who ever lived-greater than Titian, Rubens, or Rembrandt because he established the harmony of natural tones in place of the modeling in dark and light that remained the method of academic chiaroscuro. Delacroix wrote that Veronese made light without violent contrasts, "which we are always told is impossible, and maintained the strength of hue in shadow.

This innovation could not be better described. Veronese's bright outdoor harmonies enlightened and inspired the whole nineteenth century. He was the foundation of modern painting. But whether his style is in fact naturalistic, as the Impressionists thought, or a more subtle and beautiful imaginative invention must remain a question for each age to answer for itself.

Quoted From: Paolo Veronese - Wikipedia

Additional Sources

Web Gallery of Art, image collection, virtual museum, searchable database of European fine arts (1000-1850)

Paintings of Feasts (Banquets) (1560-1573)

by Paolo Veronese

The magnificent decorative style, developed in the Villa Barbaro at Maser, was taken even further in the 1560's, in a series of large paintings on the common theme of suppers at which Christ was present. Veronese used the stories from the Gospels as an excuse to stage sumptuous feasts in sixteenth-century dress inside grandiose and theatrical architectural perspectives, producing realistic representations of social life at the highest level, dominated by the magnificence of the surroundings and the refined elegance of the clothing worn by the guest. The Supper in Emmaus (Louvre, Paris), the Feast in the House of Simon, painted for the dining room of the Benedictines in San Nazaro e Celso in Verona, (now in the Galleria Sabauda, Turin), and the Marriage at Cana, executed for the refectory of the convent of San Giorgio Maggiore at Venice (now in the Louvre, Paris) belong to the series.

In the 1570's Veronese returned to the theme of the feasts, painting the Feast at the House of Simon for the monastery of Saint Sebastian (now in the Pinacoteca di Brera), the same subject for the refectory of the Servites (which the Venetian Republic donated to King Louis XIV of France in 1664 and now is at Versailles), the Feast in the House of Gregory the Great for the sanctuary of Monte Berico at Vicenza (1572), and finally the Feast in the House of Levi for the refectory of the Santi Giovanni e Paolo in Venice (now in the Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice).

In each case it was the local context that determined the huge format and particular form of the pictures. All of them were once attached to the walls at the end of the monastery refectories where, supported by the use of symmetrical pictorial architectures, they created a loose painted extension of the real space.

Quoted From: Paintings of Feasts (Banquets) 1560-1573

Supper in Emmaus: ca 1560

The magnificent decorative style, developed in the Villa Maser, was taken even further in the 1560's, in a series of large paintings on the common theme of suppers at which Christ was present. Veronese used the stories from the Gospels as an excuse to stage sumptuous feasts in sixteenth-century dress inside grandiose and theatrical architectural perspectives, producing realistic representations of social life at the highest level. The Supper in Emmaus (Louvre, Paris), the Supper in the House of Simon (Galleria Sabauda, Turin), and the Marriage at Cana (Louvre, Paris) belong to the series.

Quoted From: Supper in Emmaus

The Marriage at Cana: 1563

This immense canvas was executed for the refectory of the convent of San Giorgio Maggiore at Venice. It was removed in 1799 and taken to the Louvre. The picture portrays a sumptuous imaginary palace with about a hundred and thirty guests, portraits of celebrities of the period, of Veronese himself and of his friends dressed in richly colored costumes.

Quoted From: The Marriage at Cana

Feast in the House of Simon: 1560's

The magnificent decorative style, developed in the Villa Maser, was taken even further in the 1560's, in a series of large paintings on the common theme of suppers at which Christ was present. Veronese used the stories from the Gospels as an excuse to stage sumptuous feasts in sixteenth-century dress inside grandiose and theatrical architectural perspectives, producing realistic representations of social life at the highest level. The Supper in Emmaus (Louvre, Paris), the Supper in the House of Simon (Galleria Sabauda, Turin), and the Marriage at Cana (Louvre, Paris) belong to the series.

Quoted From: Feast in the House of Simon

Feast at the House of Simon: 1567-70

Veronese's biographer Ridolfi dates this painting to 1570. Until 1817, it hung in the dining room of the Jeronymite monastery of San Sebastiano in Venice. Weaknesses in the depiction of individual heads result from the involvement of assistants.

Quoted From: Feast at the House of Simon

Feast at the House of Simon: 1570-72

The picture intended for the refectory of the Venetian monastery of Santa Maria dei Servi forms a logical development of Veronese's Feast at the House of Simon in the Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan. Magnificent architecture reminiscent of contemporary work by Palladio and Jacopo Sansovino frames and articulates the crowded scene. In the early 1660's, numerous princely collectors vied for the picture, which in 1664 was finally given by the Serenissima to the French King Louis XIV as a politically motivated gift.

Quoted From: Feast at the House of Simon

Marriage at Cana: 1571-72

This version of the wine miracle repeats a subject already painted by Veronese in 1562-63. The structure of the work is far simpler here and more relaxed in its coloration, but nonetheless was considered in the 17th century as a perfect example of the artist's wealth of invention.

The painting - together with three other large-size works (the Adoration of the Virgin by the Coccina Family, the Adoration of the Magi, and the Road to Calvary) - was executed for the palace

Quoted From: Marriage at Cana

Feast in the House of Levi: 1573

This work, painted for the Dominican order of SS. Giovanni e Paolo to replace an earlier work by Titian destroyed in the fire of 1571, is the last of the grandiose "suppers" painted by Veronese for the refectories of Venetian monasteries.

The sumptuous banquet scene is framed by the great arches of a portico. Against the pale green shot silk effect of the background architecture, the figures on either side of Christ move in a turbulence of polychromatic splendor and interaction of pose and gesture. We seem to see here the sublime notions of form and colour of Piero della Francesca. The interaction of form and colour is calculated to contain the monumental figuration within the terms of a fascinating and imaginative decorative painting.

The expressive hedonism so alien to the religious context - the subject in fact appears to be a purely pagan one in exaltation of love of life in 16th century Venice - aroused the suspicions of the Inquisition. On July 18th 1573 Veronese was summoned by the Holy Office to appear before the Inquisition accused of heresy. If the questions of the inquisitors show the first signs of the rigors of the Counter-reformation, Veronese's answers show clearly his unfailing faith in the creative imagination and artistic freedom. Not wishing to yield to the injunction of the Inquisition to eliminate the details which offended the religious theme of the Last Supper, he changed the title to "Feast in the House of Levi", a subject which tolerated the presence of fools and armed men dressed up "alla tedesca".

Quoted From: Feast in the House of Levi

Last Supper: ca 1585

In the eighties Paolo returned once again to the theme of the Lord's Supper in the canvas painted around 1585 for the Venetian church of Santa Sofia, where it was until 1811 and now is in Brera. Here too the painter substantially modified the compositional structure he had adopted in the past for similar pictures. In particular, he changed the location of Christ, who no longer dominates the center of the scene but is placed on the left-hand edge of the canvas, while the long table is now set diagonally instead of being viewed from the front. In addition, the triumphant architectural setting of the feasts he painted in the sixties and seventies has vanished completely and the event now takes place in modest surroundings, emphasizing Christ's message of humility and poverty.

Quoted From: Last Supper

Frescoes in the Villa Barbaro, Maser (1560-61)

by Paolo Veronese

Around 1560-61, Veronese was commissioned by Daniele Barbaro to provide the interior frescoes for Barbaro's Palladian villa in Maser. The construction of the villa to a design by Andrea Palladio was completed around 1558. The decoration reflects the taste of Daniele Barbaro, a cultured humanist, and his brother Marcantonio.

Veronese decorated six rooms in the 'piano nobile' (the main floor) of the villa, as well as one wall of the last room of the eastern suite of rooms. The piano nobile is laid out in the shape of a double "T", the decorated rooms are: the Sala dell'Olimpo, the Sala a Crociera, the Stanza dell'Amore Coniugale, the Stanza di Bacco, the Stanza del Cane, the Stanza della Lucerna. The spacious Sala a Crociera (Cross-Shaped Room) connects the front and the two rooms to the south (the Stanza dell'Amore Coniugale and the Stanza di Bacco) with the large square room (the Sala dell'Olimpo) that opens onto the internal garden to the north. At the sides of the Sala dell'Olimpo are located the rooms facing onto the courtyard (the Stanza del Cane and the Stanza della Lucerna).

The frescoed scenes in the six rooms are supported and framed respectively by a system of decoration that, along with the white stuccoed molding of the door frames and fireplace, is not insignificant in determining the overall impression of the space. Floor to ceiling marble columns or pilasters subdivide the walls in all the rooms. In between, beyond low parapets, one catches sight of far-off landscapes seen from high vantage points that compete with the views from the villa's windows.

Quoted from: Frescoes in the Villa Barbaro, Maser 1560-61

Illusory Door: 1560-61

In the Sala a Crociera (Cross-Shaped Room) the theme of music and dance is represented by eight music-making figures, a pair of them flanking each of the illusory doors in the transept vestibules through which visitors appear to enter the room.

Quoted From: Illusory Door

Girl in the Doorway 1560-61

The picture shows a girl, presumably a member of the Barbaro household, apparently entering the Sala a Crociera almost by chance, but it is in fact one of the painted trompe l'oeil that still captivate visitors to the Villa Barbaro in Maser.

Quoted From: Girl in the Doorway

Muse with Tambourine 1560-61

The eight music-making Muses stand in the "transept" of the Sala a Crociera at the Villa Barbaro as symbols of harmony, thematically closely related to the dome fresco in the Sala dell'Olimpo. Only there does Thalia, daughter of Apollo Musagetes, god of music and leader of the Muses, appear in a central position. The robes worn by the Muses owe their particular colorful attractiveness to the fall of light from the side.

Quoted From: Muse with Tambourine

Muse with Lyre: 1560-61

As in most villas by Palladio, the interiors of the Villa Barbaro contain few architectural features as articulation, which is effected by paintings instead. The life-size Muses, who appear to be stepping out of niches, are part of the painted decoration as are the architecture, landscapes and the occasional children.

Quoted From: Muse with Lyre

View into the Cruciform Sala a Crociera: 1560-61

Painted Corinthian columns and "arcades", presumably carried out by Veronese's brother and assistant Benedetto Caliari, form a light architectural framework for the extraordinarily delightful trompe l'oeil landscapes with small figures and classical buildings. A continuous plaster cornice provides an upper edge and three-dimensional wall articulation, and was - like the door frames - presumably done to a design by the painter. In 1648, Veronese's biographer Carlo Ridolfi was the first to identify the musicians as muses. A pair of them flanked each of the illusory doors in the "transept" vestibules through which visitors appear to enter the room. The final elements of the decoration are the grisaille equestrian scenes below, which are in the style of cameos.

Quoted From: View into the Cruciform Sala a Crociera

View of the Sala a Crociera: 1560-61

Illusionistic fantastic landscapes in the Sala a Crociera, framed by painted arcades and columns, establish a dialog with those windows out of which one can see out onto landscape of the nearer surroundings.

The vaults, whitewashed in the nineteenth century, were originally configured as a fictive pergola.

Quoted From: View of the Sala a Crociera

Ceiling of the Sala dell'Olimpo: 1560-61

The colorful fresco decoration of the Villa Barbaro reaches its climax in the Sala dell'Olimpo. The ceiling shows Saturn, Jupiter, Mars, Apollo, Venus, Mercury and Diana, the seven gods of the sky, gathered around the figure of a woman riding a headless snake, who has been interpreted, inter alia, as an allegory of divine wisdom. As Richard Cocke has explained, however, it could be Thalia, who in conjunction with the eight muses of the transept and the gods of the sky illustrates the real theme of the dome fresco, i.e. the harmony of the spheres. The adjacent pictorial fields in the octagon illustrate the elements of fire, earth, water and air, represented by figures of the gods Vulcan, Cybele, Neptune and Juno. In between, they include four allegories inscribed in cartouches.

Quoted From: Ceiling of the Sala dell'Olimpo

Figures behind the Parapet: 1560-61

In the Sala dell'Olimpo, Veronese configured the lower part of the vault as a loggia, and standing the balustrade of this loggia are various figures dressed in contemporary clothing. The prevailing interpretation of the woman in patrician garb is that she is Giustinia Giustiniani, the wife of Marcantonio Barbaro; the simply dressed older woman next to her is then the wet nurse Giustinina's children. However, there are many arguments against this identification.

Quoted From: Figures behind the Parapet

Bacchus and Ceres: 1560-61

In the northern lunette of the Sala dell'Olimpo Bacchus and Ceres personify summer and autumn. Ceres, the goddess who taught the human race agriculture, is easy to recognize by the shafts of wheat in her hand and in her hair. The juice that Bacchus squeezes from a bunch of grapes is caught in a bowl by Ceres. The pair is surrounded by four additional figures, perhaps the Hours.

Quoted From: Bacchus and Ceres

Vulcan and Venus: 1560-61

In the southern lunette of the Sala dell'Olimpo Vulcan and Venus personify winter and spring. The figure dressed in green behind Venus is Proserpina who returns to earth each spring, remaining female figures may be nymphs.

Quoted From: Vulcan and Venus

View from the Sala dell'Olimpo, facing south: 1560-61

Around 1560-61, Veronese was commissioned by Daniele Barbaro to provide the interior frescoes for Barbaro's Palladian villa in Maser. The construction of the villa to a design by Andrea Palladio was completed around 1558. The decoration reflects the taste of Daniele Barbaro, a cultured humanist, and his brother Marcantonio.

Veronese decorated six rooms in the 'piano nobile' (the main floor) of the villa, as well as one wall of the last room of the eastern suite of rooms. The piano nobile is laid out in the shape of a double "T", the decorated rooms are: the Sala dell'Olimpo, the Sala a Crociera, the Stanza dell'Amore Coniugale, the Stanza di Bacco, the Stanza del Cane, the Stanza della Lucerna. The spacious Sala a Crociera (Cross-Shaped Room) connects the front and the two rooms to the south (the Stanza dell'Amore Coniugale and the Stanza di Bacco) with the large square room (the Sala dell'Olimpo) that opens onto the internal garden to the north. At the sides of the Sala dell'Olimpo are located the rooms facing onto the courtyard (the Stanza del Cane and the Stanza della Lucerna). The frescoed scenes in the six rooms are supported and framed respectively by a system of decoration that, along with the white stuccoed molding of the door frames and fireplace, is not insignificant in determining the overall impression of the space. Floor to ceiling marble columns or pilasters subdivide the walls in all the rooms. In between, beyond low parapets, one catches sight of far-off landscapes seen from high vantage points that compete with the views from the villa's windows.Quoted From: View from the Sala dell'Olimpo, facing south

Bacchus, Vertumnus and Saturn 1560-61

This ceiling fresco, which has lent its name to the room (Stanza di Bacco), has been variously interpreted. As a symbol of all-creative Nature, the vegetation god Bacchus, who is pressing the juice from grapes into a chalice, refers to the agricultural use of the villa. However, the combination with Saturn is unusual. Together with Bacchus, who appears here in the form of Apollo as leader of the muses, the old Roman god, lost in reverie as he listens to the music, seems to be an allusion to the harmony of the spheres.

Quoted From: Bacchus, Vertumnus and Saturn

Landscape: 1560-61

This landscape in the Stanza di Bacco is one of the illusionistic landscapes with villas and antique ruins, painted by Veronese in the Villa Barbaro.

Quoted From: Landscape

Nemesis: 1560-61

In the Stanza del Lucerna there are once again two pairs of allegorical figures, on the one side Prudence with her traditional attribute, the mirror; leaning on her is an older man with the attributes of Hercules, a lion's skin and a club, who is the personification of Manly Virtue. On the other side is the curious image of a man who has put a bridle on a woman. The bridle and measuring rod are the attributes of Nemesis, thus in this allegory the man assumes the role of Nemesis.

Quoted From: Nemesis

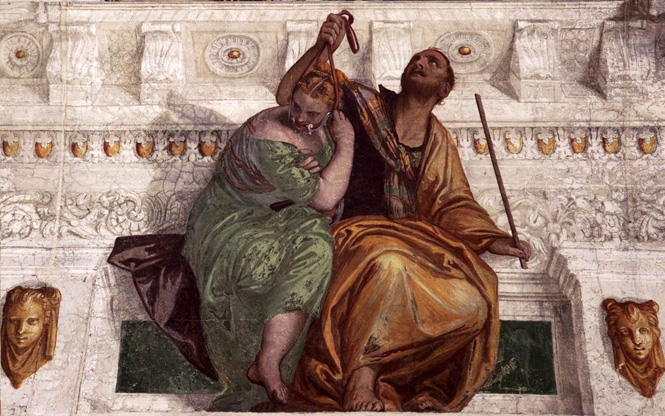

Prudence and Manly Virtue: 1560-61

In the Stanza del Lucerna there are once again two pairs of allegorical figures, on the one side Prudence with her traditional attribute, the mirror; leaning on her is an older man with the attributes of Hercules, a lion's skin and a club, who is the personification of Manly Virtue. On the other side is the curious image of a man who has put a bridle on a woman. The bridle and measuring rod are the attributes of Nemesis, thus in this allegory the man assumes the role of Nemesis.

Quoted From: Prudence and Manly Virtue

Mortal Man Guided to Divine Eternity: 1560-61

The allegory on the ceiling in the Stanza del Lucerna depicts mortal man guided to divine eternity by Charity and Faith. It is characterized entirely by Christian iconography. The figure of Charity, clad in red, entrusts a poor, half-naked man to Faith. While Charity places her foot on the worldly goods that must be renounced by the believer, Fides points to heaven where above a rainbow one can see the snake of eternity biting its own tail.

Quoted From: Mortal Man Guided to Divine Eternity

The Holy Family (Madonna della pappa): 1560-61

_1560_61.jpg)

Like the Stanza del cane, the Stanza della Lucerna has a picture of the Holy Family as part of the iconographical program. The Madonna della pappa stresses the role of Joseph as a provident 'pater familias', and is closely related thematically with the allegorical ceiling fresco, which symbolizes the precedence of the eternal values of faith.

Quoted From: The Holy Family - Madonna della pappa

Saturn (Time) and Historia: 1560-61

_and_Historia_1560_61.jpg)

Immediately under the ceiling painting in the Stanza del Cane there are two allegorical pairs of figures, on one side the personification of Chance (another form of Fortune) crowning a sleeping man, on the other side Saturn (who was also understood as the personification of time) and Historia.

Quoted From: Saturn (Time) and Historia

Chance Crowning a Sleeping Man: 1560-61

Immediately under the ceiling painting in the Stanza del Cane there are two allegorical pairs of figures, on one side the personification of Chance (another form of Fortune) crowning a sleeping man, on the other side Saturn (who was also understood as the personification of time) and Historia.

Quoted From: Chance Crowning a Sleeping Man

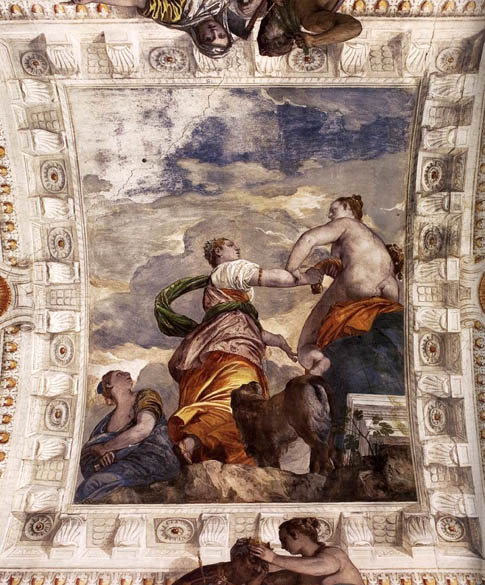

Fortune: 1560-61

The ceiling painting in the Stanza del Cane shows that fortune cannot be obtained by force: a crowned figure accompanied by a lion tries to wrest the cornucopia from Fortune, who is seated on a globe, while a third figure turns aside, concealing a knife in her breast. A possible interpretation of these figures could be that they represent Pride and Deceit.

Quoted From: Fortune

End Wall of the Stanza del Cane: 1560-61

The end wall of the Stanza del Cane (Room of the Dog) is decorated with an illusionistic landscape. Above, in the lunette, the Holy Family with St Catherine and the Infant Saint John is depicted. The room received its name owing to the presence of a small dog curled up on one side of the room.

Quoted From: End Wall of the Stanza del Cane

Landscape with Harbor: 1560-61

With Titian and Tintoretto, Veronese formed the great triad of Venetian painters in the advanced sixteenth century. With the assistance of his workshop, he decorated the interiors of the villa in Maser designed by Andrea Palladio. The wall opposite the windows, under a religious motif of The Mystical Betrothal of Saint Catherine, is occupied by an illusionistic landscape view. The flanking trompe-l'oeil architecture includes painted marble statues of two allegorical figures, and beneath the "window" on the landscape sits a little dog, made not of flesh and blood but likewise of eye-deceiving paint.

Quoted From: Landscape with Harbor

Hymen, Juno, and Venus: 1560-61

On the ceiling of the Stanza dell'Amore Coniugale (Room of Conjugal Love) there is an allegory in which we see Hymen, Juno and Venus facing a happy couple, perhaps Marcantonio and Giustiniana Barbaro.

Quoted From: Hymen, Juno, and Venus

Nobleman in Hunting Attire: 1560-61

Like the painted figures in the transepts of the Sala a Crociera, the nobleman returning from the hunt belongs to the contemporary viewer's world. East of the Stanza della Lucerna at the end of the suite of rooms, he enters the room through a trompe I'oeil door.

Quoted From: Nobleman in Hunting Attire

Paintings in Palazzo Ducale

by Paolo Veronese

Veronese worked on the decoration of many halls of the Doge's Palace, namely in the Sala del Collegio (Hall of the College), in the Sala del Consiglio dei Dieci (Hall of the Council of Ten), and in the Sala del Maggior Consiglio (Hall of the Great Council).

Quoted From: Paintings in Palazzo Ducale

Paintings in the Sala del Collegio (1575-82)

by Paolo Veronese

The Sala del Collegio (the Hall of the College) was the room where foreign delegations or important, famous personages were received and granted an audience by the College, a magistracy composed of the doge and six councilors. The hall was completely redecorated after the fire in 1574. The renovated gilded ceiling frames a series of works by Veronese between 1578 and 1582. Veronese also painted the immense canvas above the throne on the end wall of the hall.

In the antechamber (Sala di Anticollegio) hangs Veronese's Rape of Europa, among Tintoretto's canvases.

Quoted From: Paintings in the Sala del Collegio

View of the Sala del Collegio

The picture shows a view toward the throne of the Hall of the College in the Doge's Palace. The wooden gilded ceiling frames a series of works by Veronese painted between 1578 and 1582. Veronese's commemorative painting of the Allegory of the Battle of Lepanto can be seen above the throne. The paintings on the walls, above the sculpted and gilded wooden wainscot, were executed by Tintoretto and his workshop between 1581 and 1584.

Quoted From: View of the Sala del Collegio

Ceiling Paintings: 1578-82

The fire in the Doges Palace in 1574 also destroyed the decoration in the Sala del Collegio. Restoration work commenced immediately, and Veronese was commissioned to do the ceiling paintings.

The picture shows paintings by Veronese in the gilt wooden ceiling of the Sala del Collegio. The three central panels (Mars and Neptune; Faith and Religion; Venice Ruling with Justice and Peace) are surrounded by eight more canvases of alternating "T" and "L" shapes containing personifications of the Christian Virtues, interspersed on the longer sides by six more monochrome panels with Scenes from the Greek and Roman History. The allegorical program, the glorification of the "good governance" of the Venetian Republic, is clearly defined in the inscriptions that appear in the coffers next to the three biggest canvases: "Robur imperii" above Mars and Neptune, "Nunquam derelicta" and "Reipublicae fundamentum" above and below Faith and Religion and "Custodes libertatis" under Venice Ruling with Justice and Peace. The eight figures of the Virtues can be identified by the attributes that accompany them: a dog for Fidelity, a lamb for Gentleness, an ermine for Purity, a die and a crown for Reward, an eagle for Moderation, a cobweb for Dialectics, a crane for Vigilance and a cornucopia for Prosperity. These sumptuous female figures dressed in silks and brocades, splendid in their precious and limpid decorative effects and wonderfully lustrous and transparent colors, almost cancel out the limits of the restricted space to which they are confined by their lavish gilded frames, for they are set against an architectural background that seems to extend from one panel to another, creating a marvelous unity of space. The three central panels on the contrary, though characterized by the same colorings as the individual figures, appear to be separate.Quoted From: Ceiling Paintings

Religio and Fides (Religion and Faith): 1575-77

_1575_77.jpg)

The central painting of the ceiling of the Sala del Collegio in the Doge's Palace, along with the Neptune and Mars, as well as Venetia between Justitia and Pax, symbolizes in allegorical form the Republic of Venice's claims to political power. It also reminds the Council of its specific obligations, one of which was monitoring matters of faith. Although a fixed written program for the ceiling has not survived and the putative authorship of Marcantonio Barbaro cannot be proven, it is assumed that the painter was forced to follow the requirements of the clients in terms of content and presentation.

Quoted From: Religio and Fides (Religion and Faith)

Venetia between Justitia and Pax: 1575-77

This painting is on the ceiling of the Sala del Collegio in the Doge's Palace.

Flanked by the allegories of gentleness, fidelity, vigilance and prosperity, this ceiling painting presents the personifications of Justitia and Pax before the throne of Venetia. Again, this is a political allegory symbolizing the just and peaceful rule of the Republic of Venice.

Quoted From: Venetia between Justitia and Pax

Mars and Neptune: 1575-78

Here, with Mars and Neptune, against the backdrop of the bell tower of Saint Mark's and the flag-bedecked masts of the ships, the lion plays an important role. Note the amusing parallel between the warrior god's helmet and the enormous shell of the sea god.

Quoted From: Mars and Neptune

Dialectics: 1578-82

The eight figures of the Virtues can be identified by the attributes that accompany them: a dog for Fidelity, a lamb for Gentleness, an ermine for Purity, a die and a crown for Reward, an eagle for Moderation, a cobweb for Dialectics, a crane for Vigilance and a cornucopia for Prosperity. These sumptuous female figures dressed in silks and brocades, splendid in their precious and limpid decorative effects and wonderfully lustrous and transparent colors, almost cancel out the limits of the restricted space to which they are confined by their lavish gilded frames, for they are set against an architectural background that seems to extend from one panel to another, creating a marvelous unity of space.

This picture shows the Dialectics of "T" shape.

Quoted From: Dialectics

Moderation: 1578-82

The eight figures of the Virtues can be identified by the attributes that accompany them: a dog for Fidelity, a lamb for Gentleness, an ermine for Purity, a die and a crown for Reward, an eagle for Moderation, a cobweb for Dialectics, a crane for Vigilance and a cornucopia for Prosperity. These sumptuous female figures dressed in silks and brocades, splendid in their precious and limpid decorative effects and wonderfully lustrous and transparent colors, almost cancel out the limits of the restricted space to which they are confined by their lavish gilded frames, for they are set against an architectural background that seems to extend from one panel to another, creating a marvelous unity of space. The three central panels on the contrary, though characterized by the same colorings as the individual figures, appear to be separate.

This picture shows the Moderation of "L" shape.

Quoted From: Moderation

Votive Portrait of Doge Sebastiano Venier: 1581-82

The immense composition is set on the end wall of the Sala del Collegio, above the thrones reserved for the members of the Collegio (the doge, six councilors, the ministers, the heads of the Council of Ten, and the general chancellor of the Republic). The Doge, on the right offers thanks to the Redeemer for the victory of Lepanto. He is attended by saints and the allegorical figures of Faith and Justice.

Quoted From: Votive Portrait of Doge Sebastiano Venier

The Rape of Europa: ca 1578

This painting is part of the decoration in the Sala di Anticollegio. This room functioned as the antechamber of honor before being received by the College in the Sala del Collegio. Painted between 1576 and 1580, the picture was reported by Zanetti as hanging in its present place in 1755; it was removed by the French in 1797 and taken to Paris, where it was restored and altered. It represents the mythical rape of Europa by Jupiter in the guise of a bull, as she prepares to mount on the god's back with the help of her maids. The action unfolds towards the right in the manner of a stage sequence, in successive scenes down to the final plunge into the waves of the sea. The composition clearly marks the moment of transition from Renaissance Classicism to seventeenth-century Arcadia. The sumptuous decor and rich coloring were to provide a seminal experience for subsequent Baroque painting. Thus the painting initiates the exaltation of the ruling class through court mythology intended to rekindle the aristocracy's love of pomp and circumstance by allegories with which it could identify itself.

Quoted From: The Rape of Europa

Paintings in the Sala del Consiglio dei Dieci (1575-82)

by Paolo Veronese

Veronese made his artistic debut in the Palazzo Ducale as assistant of the painter Giovan Battista Ponchino in 1554-55 when, at the age of twenty-six, in the Sala del Consiglio dei Dieci he painted canvases for the gilded wood ceiling which was constructed in the previous years. Veronese's main paintings on the ceiling are the Jupiter Hurling Thunderbolts at the Vices (oval, now in the Louvre, replaced here by a nineteenth-century copy), Aged Oriental with a Young Woman (oval), Juno Showering Gifts on Venetia (rectangular), and The Triumph of Virtue over Vice (rectangular).

Quoted From: Paintings in the Sala del Consiglio dei Dieci

View of the Sala del Consiglio dei Dieci: ca 1551

The much-feared Consiglio dei Dieci (Council of Ten) was responsible for Venice's security. Its meeting-place is the first of a series of rooms used for the administration of justice. Paolo Veronese and Giambattista Zelotti made their Venetian debut here as the assistants of the painter Giovan Battista Ponchino.

Quoted From: View of the Sala del Consiglio dei Dieci

Jupiter Hurling Thunderbolts at the Vices: 1554-56

This oval ceiling painting was originally the central picture gracing the ceiling of the Sala del Consiglio dei Dieci in the Doge's Palace. In 1797 it was confiscated by the art commissars of Napoleon Bonaparte and removed to Paris. In 1863 Jacopo di Andrea made a copy at the behest of the government, and this now replaces the looted original in Venice.

A principal feature of the picture is the bold use of foreshortened perspectives, of which the ceiling painter was a supreme master. The sculpturally rounded figures stand out dramatically against the blue of the sky.

Quoted From: Jupiter Hurling Thunderbolts at the Vices

Aged Oriental with a Young Woman: 1554-56

This oval painting is on the left of the main picture (Jupiter Hurling Thunderbolts at the Vices) on the ceiling of the Sala del Consiglio dei Dieci in the Palazzo Ducale.

For the Venetian painter Palma il Giovane, it was a masterpiece of painting: in this, he considered Veronese had achieved something extraordinary, successfully blending the greatest advances made in antiquity with his own maniera. The subject of the picture is not known, the modern name being just for convenience. The bearded old man, sunk in thought on the ruins of ancient architecture, may have reminded Palma of pictures of classical philosophers.

There are many interpretative cruxes in the introspective allegory, whose subject is as obscure as its colour is bright: Youth and Old Age, or Venice and the East, or Venus and Saturn.

Quoted From: Aged Oriental with a Young Woman

Juno Showering Gifts on Venetia: 1554-56

This painting is on the ceiling of the Sala del Consiglio dei Dieci in the Palazzo Ducale.

The goddess Juno, wife of Jupiter, is (like the personification of Venetia) shown in sharp bottom view. The gilt framework of the ceiling acts as the base of the composition, the frame being linked with the main central picture by a narrow band. Gold crowns, jewels, and money cascade onto Venice, with the Doge's hat and a plain olive wreath. The vocation to power and the vocation to peace are seen as two sides of the same coin.Quoted From: Juno Showering Gifts on Venetia

The Triumph of Virtue over Vice: 1554-56

This painting is on the ceiling of the Sala del Consiglio dei Dieci in the Palazzo Ducale.

Laurel wreath and palm bough indicate that the brilliantly weighted Virtue has triumphed over Vice. As with all the other ceiling paintings in the rooms of the Council of Ten, the Triumph of Virtue over Vice has a strongly moralizing tone. Like mute admonitions, the paintings remind the Council of Ten as guardians of order and decency of one of their main tasks - fighting vice.Quoted From: The Triumph of Virtue over Vice

Paintings in Sala del Maggior Consiglio

by Paolo Veronese

The present decoration of the Sala del Maggior Consiglio (Hall of the Great Council) in the Palazzo Ducale was realized after the disastrous fire of 1577 during which all the structures of the ship's-keel Gothic ceiling and the wall-paintings were destroyed. An immense flat ceiling, in accordance with the taste of the end of the century, was constructed with gilded cornices sculpted in high-relief, which framed a series of paintings. The canvases were dedicated, thematically, to the Glorification of Venice, in remembrance of the numerous military undertakings in the East or on the mainland by the Venetian ground troops.

On the ceiling great importance was given to the victories of the Venetian army in conquering the mainland; along the wall to the dispute between Alexander III and Frederick Barbarossa, who reached an agreement in Venice with the political mediation of Doge Sebastiano Ziani; and to the events of the Fourth Crusade, led by Doge Enrico Dandolo in the early years of the 13th century.Quoted From: Paintings in Sala del Maggior Consiglio

View of the Sala del Maggior Consiglio: Post 1577

The Sala del Maggior Consiglio (Hall of the Great Council) is the heart of the Palazzo Ducale. This immense chamber was used for assemblies of the Great Council, the largest organ of government in the Venetian state, attended by all patricians over the age of twenty-five. Devastated in the fire of 1577, it was rapidly rebuilt and redecorated. The thirty-five ceiling canvases, some of them by Veronese, celebrate the glory of Venice allegorically and illustrate the Republic's military history. On the end wall Tintoretto and his pupils painted the enormous representation of Paradise.

Quoted From: View of the Sala del Maggior Consiglio

Apotheosis of Venice: 1585

This painting was commissioned by the Venetian government for the ceiling of the Sala del Maggior Consiglio of the Palazzo Ducale. It is one of the thirty five panels on the ceiling.

Rising above the bank of clouds, the royally garbed personification of Venice sits enthroned between the twin towers of the city's Arsenal, about to be crowned with laurel by flying victories. Arrayed at her feet and offering her wise counsel are personifications of peace, abundance, fame, happiness, honor, security, and freedom. An especially splendid triumphal arch, fronted by twisting columns, marks the top of an enormous balcony which seems to burst through the ceiling into the ether beyond in order to accommodate the multitudes of celebrating people stipulated in the commission. At the base, Venice's smiling subjects seem undisturbed by the enormous size and energy of careening horsemen in their midst reminder of Venice's considerable military might. Illusionistic foreshortenings and dramatic light effects serve to give political allegory a previously unimagined dynamism and visual excitement.Quoted From: Apotheosis of Venice

Siege of Scutari: 1585

On the ceiling decoration of the Sala del Maggior Consiglio great importance was given to the victories of the Venetian army in conquering the mainland; along the wall to the dispute between Alexander III and Frederick Barbarossa, who reached an agreement in Venice with the political mediation of Doge Sebastiano Ziani; and to the events of the Fourth Crusade, led by Doge Enrico Dandolo in the early years of the 13th century.

Veronese's Siege of Scutari is one of the thirty five panels on the ceiling of the Sala del Maggior Consiglio.Quoted From: Siege of Scutari

Conquest of Smyrna: 1585

On the ceiling decoration of the Sala del Maggior Consiglio great importance was given to the victories of the Venetian army in conquering the mainland; along the wall to the dispute between Alexander III and Frederick Barbarossa, who reached an agreement in Venice with the political mediation of Doge Sebastiano Ziani; and to the events of the Fourth Crusade, led by Doge Enrico Dandolo in the early years of the 13th century. Veronese's Conquest of Smyrna is one of the thirty five panels on the ceiling of the Sala del Maggior Consiglio. It depicts Pietro Mocenigo leading the attack on Smyrna.

Quoted From: Conquest of Smyrna

Paintings in the Salon of the Biblioteca Marciana (1556-60)

by Paolo Veronese

The wooden ceiling of the Salon of the Biblioteca (Libreria) Marciana contains twenty-one canvases painted between 1556 and 1559 by seven different artists including Veronese, chosen, according to the records, by Jacopo Sansovino and Titian. The side walls are also richly decorated with canvases by various hands representing the Philosophers. Paolo Veronese did the two beside the portal, Plato and Aristotle.

Quoted From: Paintings in the Salon of the Biblioteca Marciana

View of the Biblioteca

The Biblioteca Marciana was designed by Jacopo Sansovino to house the about thousand illuminated manuscripts donated to the Republic by Cardinal Bessarion. The interior was adorned with paintings by Tintoretto, Paolo Veronese, Giovanni de Mio, Battista Franco, Giuseppe Salviati, Andrea Schiavone, and Giovan Battista Zelotti.

Quoted From: View of the Biblioteca

Honor: 1556-57

This tondo belongs to a series of 21 such circular pictures adorning the ceiling of the great room of the Libreria Vecchia.

Even Vasari, who interpreted the ruler on the throne as the personification of Honor, got no further in 1568 than a mere description of this enigmatic scene. The ruler's throne is decorated on each side by small, carved figures. The one on his left holds a scepter, the tip of which forms an eye. Various figures present themselves in front of the throne, including a woman with a child (Caritas?), a kneeling figure bearing an animal sacrifice and a bearded old man with a crown woven of laurel boughs. A comparison of the tondi in the Biblioteca Marciana shows that Veronese supplied works of very differing approaches and quality. The harmoniously grouped figures in Music translate the dramatic pictorial resources of the ceiling paintings of San Sebastiano into a calm, classic style. In contrast, the two figures with their backs turned to us in Honor resound with Mannerist echoes. Veronese here applies Tintoretto's principle of divergence to the arrangement of moving figures.Quoted From: Honor

Music, Astronomy and Deceit: 1556-57

This tondo belongs to a series of 21 such circular pictures adorning the ceiling of the great room of the Libreria Vecchia.

This central tondo is introduced by a kneeling female figure who, holding a flute in her left hand, turns her head to gaze upwards. Presumably, she represents music. Assigned to her is a young woman, who is studying a book with astronomical plates. Standing on a sheet of music, she appears to be listening to the sounds of heaven. On the right, the scene concludes with a woman examining a book with geometrical diagrams. The back of her head is covered by the mask of an old man.Quoted From: Music, Astronomy and Deceit

Music: 1556-57

This tondo belongs to a series of 21 such circular pictures adorning the ceiling of the great room of the Libreria Vecchia. Sansovino and Titian awarded the work a golden chain as the best painting, the chain being later recorded in the estate of Veronese's heirs. The Libreria Vecchia housed not only reading and lecture rooms but also the offices of the procurators. It is not known whether a specific program and defined sequence underlay the decoration. Even the iconography of most of the pictures throws up puzzles.

Corresponding to the purpose of the room and function of the building, the pictures illustrate allegories of education, the arts and sciences. Contemporary commentators related the decoration to the good conduct of government and its foundations, which required not just a virtuous, but also an erudite ruler.Quoted From: Music

Music: 1556-57 Two

This tondo, one of the twenty-one painted for the ceiling of the celebrated library, won the golden chain prize for the artist.

On the painting, the Apollonian serenity of the noble winged instruments is offset by the Dionysiac presence of the mutilated statue of the predatory faun.Quoted From: Music 1556-57

Plato: 1560's

The wooden ceiling of the Salon of the Biblioteca (Libreria) Marciana contains twenty-one canvases painted between 1556 and 1559 by seven different artists, chosen, according to the records, by Jacopo Sansovino and Titian. The side walls are also richly decorated with canvases by various hands representing the Philosophers. Paolo Veronese did the two beside the portal, Plato and Aristotle.

Quoted From: Plato 1560's

Aristotle: 1560's

Paintings of Mythological and Allegorical Subjects

by Paolo Veronese

Honor et Virtus Post Mortem Floret: Ante 1567

Marked top left with the inscription (HO)NOR ET VIRTVS/ (P)OSTMORTE(M) FLORET, this picture is also described as Hercules between Virtue and Vice, alluding to the story told in Hesiod when Hercules meets two beautiful women at a fork in the road. The youthful hero of the allegory is an elegantly clad Venetian in white silk garments, who was taken at the end of the 17th century, when the picture was in the collection of Queen Christina of Sweden in Rome, to be a self-portrait of the artist. Unhesitatingly he turns to Virtue, who is crowned with a laurel wreath. Drops of blood on his ripped leg covering testify to the fruitless attempt by Vice - Lust and Pleasure, in the long run the death-bringing opponent of Virtue - to hold back the man of honor and win him over.

Quoted From: Honor et Virtus Post Mortem Floret

Allegory of Wisdom and Strength: ca 1580

Wisdom, personified by a female figure, looks upward to heaven, standing over a globe symbolizing the world. Below her are crowns, scepters, jewels, coins, and military banners. Cupid sits on the right, while Hercules with his lion's skin stands as a symbol of power.

Quoted From: Allegory of Wisdom and Strength

Venice, Hercules, and Ceres: 1575

This painting, which dates from 1575, originally decorated the ceiling of the Magistrato delle Biade in the Doge's Palace. In the skillful perspective and in the limpid intensity of tone the figures stand out against the blue sky broken by white-gold clouds achieving a perfect balance in space with a rhythmic natural elegance and Olympian beauty. Even the figures in half-light are endowed with the same intense luminous colour. The figure of Venice enthroned is of particular beauty. As usual, Venice is enthroned in glory, but for once the triumphant fanfares, and even Hercules's club yield center stage to the luxuriance of Ceres's wheat, and of her body.

Quoted From: Venice, Hercules, and Ceres

Allegory of Love I Infidelity ca 1575

This canvas is one of a series of four evidently representing various attributes of love, or perhaps different stages of love culminating in happy union. They were clearly designed as compartments of a decorated ceiling and might conceivably relate to a nuptial bedchamber. Veronese used this type of 'oblique perspective' for ceiling decorations in Venice: the angle of foreshortening corresponds to a viewpoint obliquely beneath the painting, avoiding the extreme distortion of figures imagined as directly above the viewer's head. By 1637 the four allegories, now all in the National Gallery, were recorded in the collection at Prague of the Emperor Rudolph II, the great art patron of his age, who probably commissioned them.

The appearance of all four paintings has been badly affected by the irreversible discoloration of the smalt - a comparatively cheap blue pigment made from pulverized glass colored with cobalt oxide - used to paint the sky, which now gives it a pale grey tinge instead of its original warm blue. With age, some of the green copper resonates of the foliage have oxidized to brown. In most respects this is the best preserved of the four pictures, and the one where Veronese's own hand, as opposed to his workshop assistants', is most visible.Quoted From: Allegory of Love I Infidelity

The Allegory of Love II: Scorn ca 1575

This canvas is one of a series of four evidently representing various attributes of love, or perhaps different stages of love culminating in happy union. They were clearly designed as compartments of a decorated ceiling and might conceivably relate to a nuptial bedchamber. Veronese used this type of 'oblique perspective' for ceiling decorations in Venice: the angle of foreshortening corresponds to a viewpoint obliquely beneath the painting, avoiding the extreme distortion of figures imagined as directly above the viewer's head. By 1637 the four allegories, now all in the National Gallery, were recorded in the collection at Prague of the Emperor Rudolph II, the great art patron of his age, who probably commissioned them.

The appearance of all four paintings has been badly affected by the irreversible discoloration of the smalt - a comparatively cheap blue pigment made from pulverized glass colored with cobalt oxide - used to paint the sky, which now gives it a pale grey tinge instead of its original warm blue. With age, some of the green copper resonates of the foliage have oxidized to brown. In most respects this is the best preserved of the four pictures, and the one where Veronese's own hand, as opposed to his workshop assistants', is most visible. As befits an allegory, the meaning of the picture must be teased out. A nearly naked man is lying writhing on a ruinous ledge - perhaps an altar - in front of a statue in a niche holding a set of Pan pipes against its hairy thigh. The marble torso to the left of the statue has the goatish features of a satyr. This is a crumbling temple to the pagan divinities of unbridled sexuality. Cupid uses his bow mercilessly to beat the man, watched by two women: a shimmering bare-breasted beauty in a silver-striped dress with rose and yellow kirtle, accompanied by a duenna. Enfolded within her green mantle the chaperon holds a small white beast - an ermine, symbol of chastity, thought to prefer death to impurity. The general significance, then, is clear. The man has been felled by lust for a sensuous yet chaste woman, and is being punished. But the trite verbal translation does not begin to do justice to Veronese's robustly and wittily imagined scene: the ferocious plump Cupid astride his hapless victim, the scornful femme fatale drawing aside her skirts.Quoted From: The Allegory of Love II: Scorn

Allegory of Love III: Respect ca 1575

In the 1570's, Veronese did not confine his attention to religious subjects. He was also intensively active in the field of profane painting, often with an erotic content. The series of the so-called Allegories of Love in the National Gallery in London belongs to the latter group. The four painting, which were probably originally intended to decorate the ceiling of a single room, were in the eighteenth century entitled Infidelity, Disillusionment, Respect, and Happy Union. However, since then the paintings have been given differing interpretations. The most widely accepted hypothesis is that they represent the sorrows and pleasures of love in contrasting pairs - joy and disenchantment, faithfulness and unfaithfulness.

Quoted From: Allegory of Love III: Respect

Allegory of Love IV: Happy Union ca 1575

Lucretia: 1580's

Lucretia, the virtuous wife of Lucius Tarquinius Collatinus, committed suicide, as she could not endure the shame of being raped by Sextus Tarquinius, as Livy related. This deed secured the legendary Roman lady a place in the series of exemplary females that in European painting, particularly in court circles, were depicted as examples of virtue.

Quoted From: Lucretia

Venus and Adonis: ca 1562

The subject of this painting and the scheme of composition are clearly derived from the mythological and erotic paintings that Titian referred to as his poesie ("poems"). However, the warm and cheerful palette is entirely Veronese's.

Quoted From: Venus and Adonis ca 1562

Susanna and the Elders: 1585-88

In the last decade of his life Veronese painted a major cycle of religious pictures made up of ten oblong canvases of equal size inspired by stories from the Old and New Testament, known to scholars as the Duke of Buckingham series, after the name of the nobleman who owned them in the early seventeenth century. The canvases, now divided among the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, which has seven of them, the National Gallery in Washington (one) and the Narodni Galerie in Prague (two), were probably intended for a convent. They are the following: Lot and his Daughters Leaving Sodom, Hagar in the Wilderness, Rebecca at the Well, Susanna and the Elders, Esther and Ahasver, Adoration of the Shepherds, Christ and the Centurion, Christ and the Adulteress, Christ and the Woman of Samaria, and Christ Washing the Feet of the Disciples.

The striking feature of the series, to which the canvas Susanna and the Elders belongs, is the unusual monumentality of the figures, most of them located in the foreground.

Quoted From: Susanna and the Elders 1585-88

Paintings of Religious Subjects (1540's)

by Paolo Veronese

Raising of the Daughter of Jairus: ca 1546

This painting is considered a modello for a now lost painting said by Carlo Ridolfi in 1648 to be in the church of San Bernardino in Verona. It shows Jesus visiting the house of the synagogue elder Jairus, whose 12-year-old daughter had just died. When he enters the sick girl's chamber, he asks the minstrels and the wailing women to leave the house. He then takes her hand and brings her back to life, saying: "Maiden, I say unto thee, arise." This miracle, told in the gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke, is set by Veronese in the forecourt of a Renaissance palace. The viewer's eye is led through the arch to the musicians and wailing women, who were induced to leave the scene of the event.

Quoted From: Raising of the Daughter of Jairus

Madonna Enthroned with Child, Saint John the Baptist, Saint Louis of Toulouse and Donors: 1546-48

Despite several formal inconsistencies, the altar painting for the church of San Fermo Maggiore in Verona is an expression of Veronese's early mastery. It was apparently commissioned by Giovanni Bevilacqua-Lazise, and he and his deceased wife Lucrezia Malaspina are probably the donors in the picture.

Quoted From: Madonna Enthroned with Child, Saint John the Baptist, Saint Louis of Toulouse and Donors: 1546-48

Lamentation over the Dead Christ: ca 1547

The unusual feature of the iconography is that it is not Joseph of Arimathaea that holds the body of Christ as would be customary, but Nicodemus, identifiable because he is younger, has a dark beard and wears turban-style headgear. His hands are covered to avoid direct physical contact. Joseph of Arimathaea on the other hand appears in the background as an old man with a white beard and hair in a well-chosen three-quarters profile. His features are undoubtedly presented as a portrait so that one could imagine him as a prominent member of the monastic community, perhaps even the patron who commissioned the devotional picture. In view of the sketch-like, summary execution of some parts of this very well-preserved picture, it has been assumed that it was a preparatory oil sketch for a larger-format painting that was never carried out. An argument against this is the masterly, delicate palette of reds, yellows, greens and blues providing delightful contrasts with violet and pink.

The composition is based on an etching by Parmigianino. Characteristic of Veronese's free treatment of motifs and stylistic mannerisms is the way he adapts the gesture of Parmigianino's Joseph of Arimathaea and the emotional intensity of individual figures.

Quoted From: Lamentation over the Dead Christ

Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine: 1547

This picture shows the Holy Family with Saint Catherine of Alexandria and Saint Anne. According to a 9th-century legend, Saint Catherine was a princess converted to Christianity by a hermit. The child Jesus appeared to her later in a dream and handed her a ring as a sign of her engagement. Under the worried gaze of Joseph, the saint - dressed as an elegant Venetian woman - turns lovingly towards the child sitting in his mother's lap, who reacts with excited pleasure.

Quoted From: Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine

Conversion of Mary Magdalene: ca 1547

The interpretation of the subject is controversial. The Magdalene's usual attribute of a pot of ointment is missing, and therefore the crowded painting has been rather unconvincingly interpreted as Jesus and the Woman Taken in Adultery (St. John 8, 3 -11) or even The Healing of the Woman with the Issue of Blood {St. Mark 5, 25-34).

Quoted From: Conversion of Mary Magdalene

Deposition of Christ: 1548-49

Many of the Veronese's paintings that can be dated to the period prior to 1550 contain typical Mannerist elements. Common to all these works are a graphic structure of evident Mannerist inspiration and the superb quality of the colour, characterized by the contrast of paler tones, enlivened by luminous reflections.

Quoted From: Deposition of Christ

Paintings of Religious Subjects (1550's)

by Paolo Veronese

Holy Family with Saints Anthony Abbot, Catherine and the Infant John the Baptist: 1551

This altarpiece is referred to as the Pala Giustinian, since it was commissioned by Antonio Giustinian, provveditore della fabbrica (building inspector), who would have been the painter's paymaster.

Clearly contrasting cool colors in the service of precise, dramatically constructed forms are the main characteristics of Veronese's first altar painting for a Venetian church. Infrared reflectography recently brought to light a surprising technical finding: originally, parts of the pictorial architecture in the background of the picture were differently arranged. In an early phase, the column behind Mary was roughly in the center of the picture. As the painting proceeded, it was overpainted and moved right. Clearly not initially envisaged, therefore, was the awkward-looking pier fragment with its engaged half-column, whose relationship with the other architectural motifs produces inconsistencies of perspective. When Agostino Carracci copied the large painting around 1582, one of the things that he corrected was the harsh arris at the top of the pier.Quoted From: Holy Family with Saints Anthony Abbot, Catherine and the Infant John the Baptist

Temptation of Saint Anthony: 1552

Perhaps this drawing was a never implemented modello for a painting.

Quoted From: Temptation of Saint Anthony

The Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine: ca 1555