Disclaimer

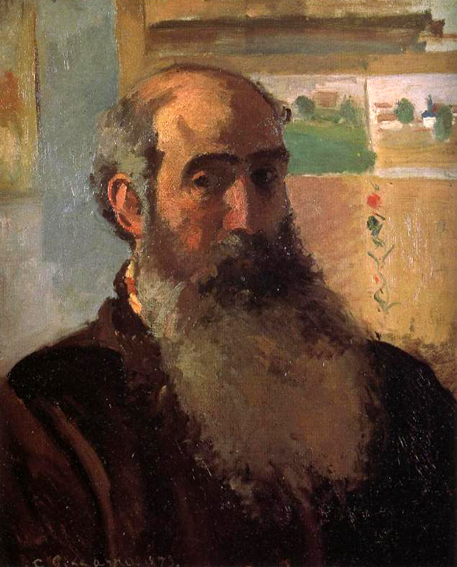

Camille Pissarro

French Impressionist Painter

1830 - 1903

Quotes by Camille Pissarro

Blessed are they who see beautiful things in humble places where other people see nothing.

Don't be afraid in nature: one must be bold, at the risk of having been deceived and making mistakes.

Everything is beautiful, all that matters is to be able to interpret.

It is only by drawing often, drawing everything, drawing incessantly, that one fine day you discover to your surprise that you have rendered something in its true character.

When you do a thing with your whole soul and everything that is noble within you, you always find your counterpart.

All the sorrows, all the bitternesses, all the sadnesses, I forget them and ignore them in the joy of working.

It is absurd to look for perfection.

Camille Pissarro was a French Impressionist painter. His importance resides not only in his visual contributions to Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, but also in his patriarchal standing among his colleagues, particularly Paul Cézanne and Paul Gauguin.

Jacob-Abraham-Camille Pissarro was born on the island of Saint Thomas, Virgin Islands, to Abraham Gabriel Pissarro, a Portuguese Sephardic Jew, and Rachel Manzano-Pomié, from the Dominican Republic. Pissarro lived in Saint Thomas until age 12, when he went to a boarding school in Paris. He returned to Saint Thomas where he spent his free time. Pissarro was attracted to political anarchy, an attraction that may have originated during his years in Saint Thomas. In 1852, he traveled to Venezuela with the Danish artist Fritz Melbye. In 1855, Pissarro left for Paris, where he studied at various academic institutions (including the École des Beaux-Arts and Académie Suisse) and under a succession of masters, such as Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Gustave Courbet, and Charles-François Daubigny. Corot is sometimes considered Pissarro's most important early influence; Pissarro listed himself as Corot's pupil in the catalogues to the 1864 and 1865 Paris Salons.

His finest early works (See Jalais Hill, Pontoise, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) are characterized by a broadly painted (sometimes with palette knife) naturalism derived from Courbet, but with an incipient Impressionist palette.

Jalais Hill, Pontois: 1867

Pissarro married Julie Vellay, a maid in his mother's household. Of their eight children, one died at birth and one daughter died aged nine. The surviving children all painted, and Lucien, the oldest son, became a follower of William Morris.

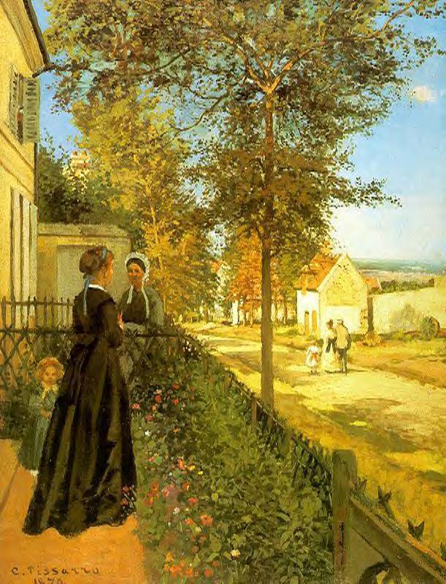

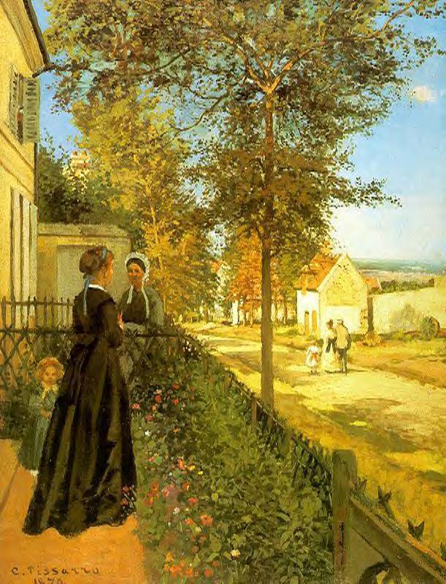

The Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71 compelled Pissarro to flee his home in Louveciennes in September 1870; he returned in June 1871 to find that the house, and along with it many of his early paintings, had been destroyed by Prussian soldiers. Initially his family was taken in by a fellow artist in Montfoucault, but by December 1870 they had taken refuge in London and settled at Westow Hill in Upper Norwood (today better known as Crystal Palace, near Sydenham). A Blue Plaque currently marks the site of the house on the building at 77a Westow Hill.

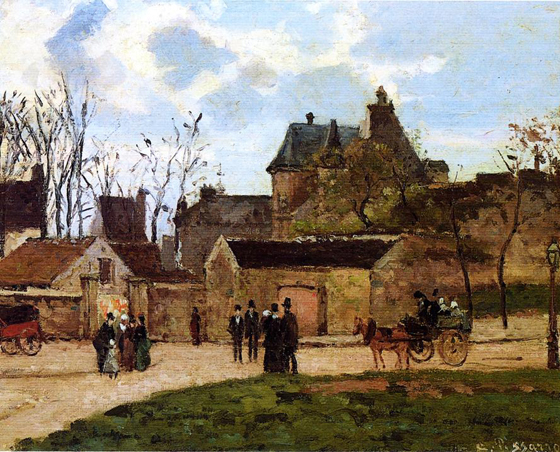

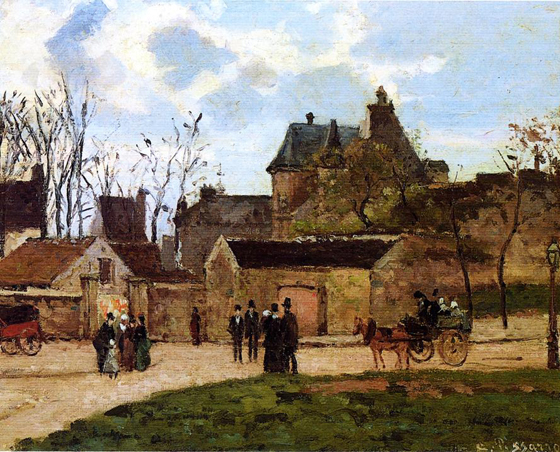

A Road in Louveciennes: 1872

Through the paintings Pissarro completed at this time, we can glimpse back to the days when Sydenham was a small satellite town recently connected to the capital by the arrival of the railway. One of the most appreciated of these paintings is a view of Saint Bartholomew's Church at the end of Lawrie Park Avenue, commonly known as The Avenue, Sydenham, in the collection of the London National Gallery. Twelve oil paintings date from his stay in Upper Norwood and are listed and illustrated in the catalogue raisonné prepared jointly by his fifth child Ludovic-Rodolphe Pissarro and Lionello Venturi and published in 1939. These paintings include Norwood Under the Snow, and Lordship Lane Station, views of The Crystal Palace relocated from Hyde Park, Dulwich College, Sydenham Hill, All Saints Church, and a lost painting of Saint Stephen's Church.

The Avenue, Sydenham: 1871

This painting is among the largest that Pissarro is known to have painted in London during the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1). These works mainly represent scenes in the area of Norwood (including 'Fox Hill, Upper Norwood'), where Pissarro stayed until June 1871.

This work depicts a scene that is little changed today. The painting conveys the atmosphere of an early spring day, with oak trees coming into leaf against a soft blue sky.

Technical analysis shows that the main outlines of the landscape were painted first and the figures added over the paint that had dried.

Norwood under Snow: 1870

Towards the end of 1870 Pissarro and his family took refuge in England from the Franco-Prussian war. He stayed in Upper Norwood, London until June 1871, and painted several views of Norwood and Sydenham including 'The Avenue, Sydenham'. Many of the houses in this street have been rebuilt but the general character of this view and the distinctive bend still correspond with Pissarro's painting.

Lordship Lane Station: 1871

The Crystal Palace: 1871

Camille Pissarro painted nearly a dozen works, including 'The Crystal Palace', during his brief, self-imposed exile in England at the time of the Franco-Prussian War and the Paris Commune (1870-71). Fleeing his home in Louveciennes, near Paris, to avoid the Prussian invasion of France and subsequent civil uprising in the streets of the capital, he moved his family first to Brittany, on the coast of the English Channel, and then to Lower Norwood, outside of London. In the neighboring suburb of Sydenham, he encountered the soaring, glass-and-iron Crystal Palace. Originally designed by Joseph Paxton in 1851 to house Prince Albert's "Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations" in London's Hyde Park, the structure-immediately acknowledged as a landmark of modern architecture-was dismantled and reassembled in Sydenham in 1853. (A fire destroyed it in 1936.)

Surprisingly, Pissarro chose to relegate what had been labeled the world's largest building to the left portion of the composition, while giving equal space to the recently constructed middle-class homes at the right and to the families and carriages parading down the street in the center. Perhaps the artist, who typically depicted rural settings, was initially captivated by the play of sunlight across two very different forms of contemporary construction; he established a striking juxtaposition between Paxton's impressive edifice and the ordinary row houses across the way by focusing on atmosphere rather than on disparity of scale. Rendering the Crystal Palace in a range of translucent, aquatic blues that blend into the swirling sky beyond, Pissarro lent the spectacular exhibition hall a light airiness that contrasts with the weighty solidity of the brick residences. Yet the painting accommodates both, presenting a balanced view of a unique, suburban landscape.

Dulwich College, London 1871

Saint Stephen's Church

A painting of Saint Stephen's Church by Camille Pissarro

The following is based on an extract of the history of Saint Stephen's entitled 'The story of St Stephen's Church South Dulwich, a beacon in times of Peace and War (by Michael Goodman, 2007, available on sale from the parish office)

Not long after Saint Stephen's was built, an event of subsequent significance occurred when Camille Pissarro, the renowned French Impressionist painter, brought his family to England to avoid the rigors of the Franco-Prussian war. In a letter to his friend Wynford Dewhurst in 1902 he wrote: 'In l870 I found myself in London with (Claude) Monet, and we met Daubigny and Bonvin. Monet and I were very enthusiastic over the London landscapes. Monet worked in the park' - he in fact stayed at The Savoy Hotel - 'while I, living in Lower Norwood, at that time a charming suburb, studied the effects of fog, snow and springtime.' During the time he was here, Pissarro painted several scenes in the Dulwich area, including 'Dulwich College', 'Crystal Palace Parade' and 'Lordship Lane Station' with a steam train very much in evidence, running past. In particular, he painted Saint Stephen's Church from what is now College Road, looking up the hill with the church on the right and the Crystal Palace looming over the trees in the distance (now the site of the BBC Television Mast!). The wood remains one of the few areas untouched since Pissarro's day by the spread of the city, save that the once tranquil scene is now disturbed by the rows of parked motor cars left there by commuters using Sydenham Hill Station.

While in Upper Norwood, Pissarro was introduced to the art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel, who bought two of his 'London' paintings. Durand-Ruel subsequently became the most important art dealer of the new school of French Impressionism.

In 1890 Pissarro returned to England and painted some ten scenes of central London. He came back again in 1892, painting in Kew Gardens and Kew Green, and also in 1897, when he produced several oils of Bedford Park, Chiswick.

Kew Gardens: 1892

Kew Green: 1892

Bedford Park

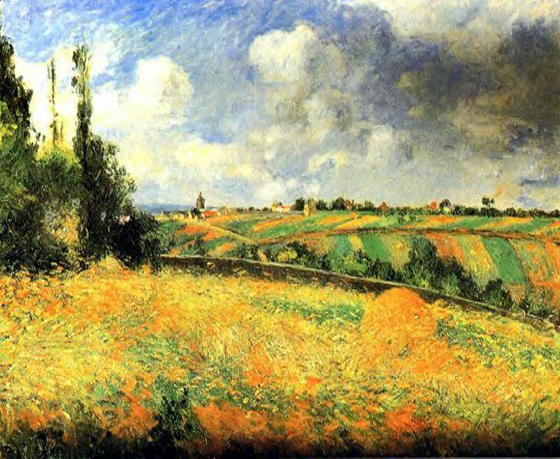

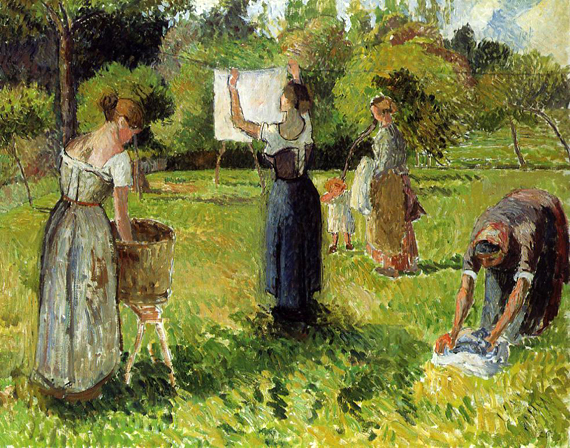

Known as the "Father of Impressionism", Pissarro painted rural and urban French life, particularly landscapes in and around Pontoise, as well as scenes from Montmartre. His mature work displays an empathy for peasants and laborers, and sometimes evidences his radical political leanings. He was a mentor to Paul Cézanne and Paul Gauguin and his example inspired many younger artists, including Californian Impressionist Lucy Bacon.

Pissarro's influence on his fellow Impressionists is probably still underestimated; not only did he offer substantial contributions to Impressionist theory, but he also managed to remain on friendly, mutually respectful terms with such difficult personalities as Edgar Degas, Cézanne and Gauguin. Pissarro exhibited at all eight of the Impressionist exhibitions. Moreover, whereas Monet was the most prolific and emblematic practitioner of the Impressionist style, Pissarro was nonetheless a primary developer of Impressionist technique.

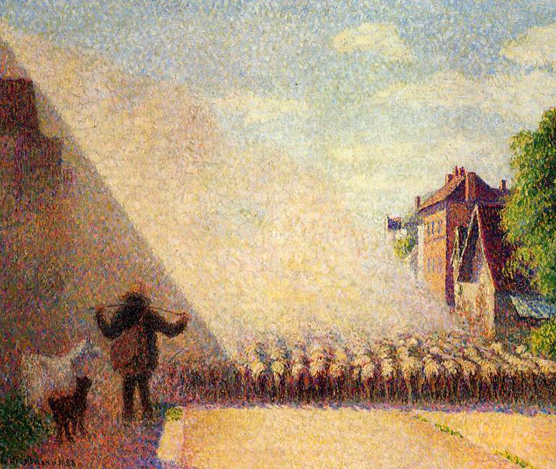

Pissarro experimented with Neo-Impressionist ideas between 1885 and 1890. Discontented with what he referred to as "Romantic Impressionism," he investigated Pointillism which he called "Scientific Impressionism" before returning to a purer Impressionism in the last decade of his life.

In March 1893, in Paris, Gallery Durand-Ruel organized a major exhibition of 46 of Pissarro's works along with 55 others by Antonio de La Gandara. But while the critics acclaimed Gandara, their appraisal of Pissarro's art was less enthusiastic.

Pissarro died in Éragny-sur-Epte on either November 12 or November 13, 1903 and was buried in Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris. On his tomb it reads November 12, 1903.

During his lifetime, Camille Pissarro sold few of his paintings. By 2005, however, some of his works were selling in the range of U.S. $2 to 4 million.

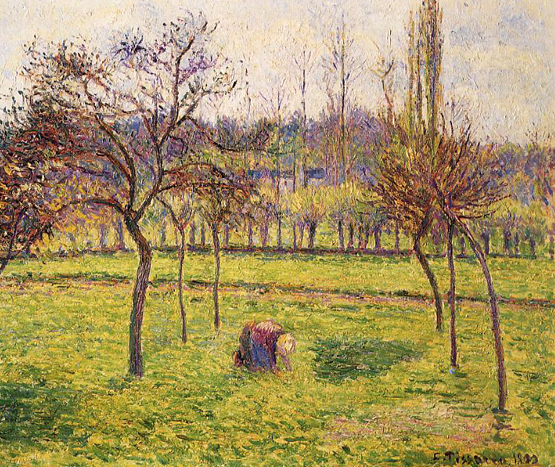

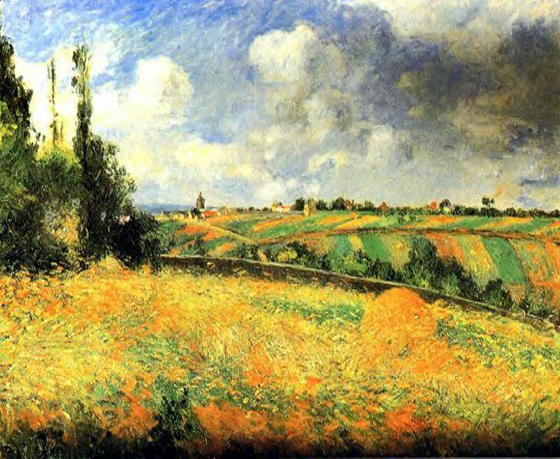

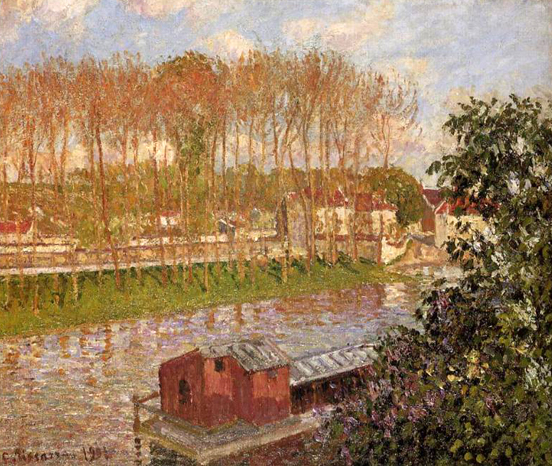

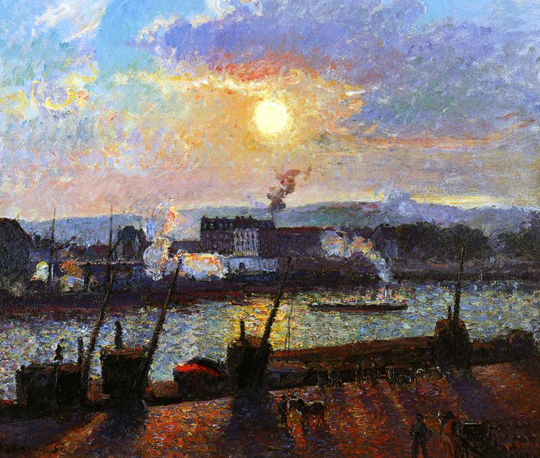

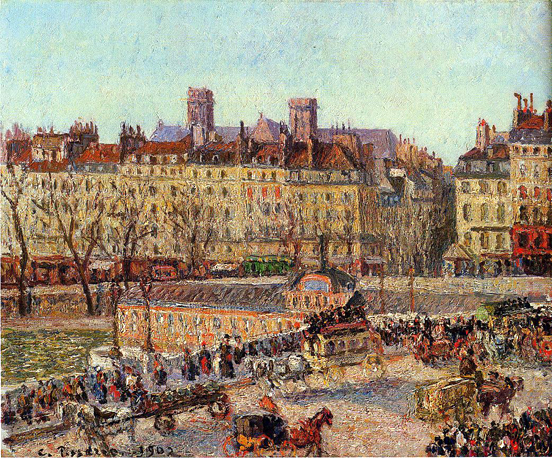

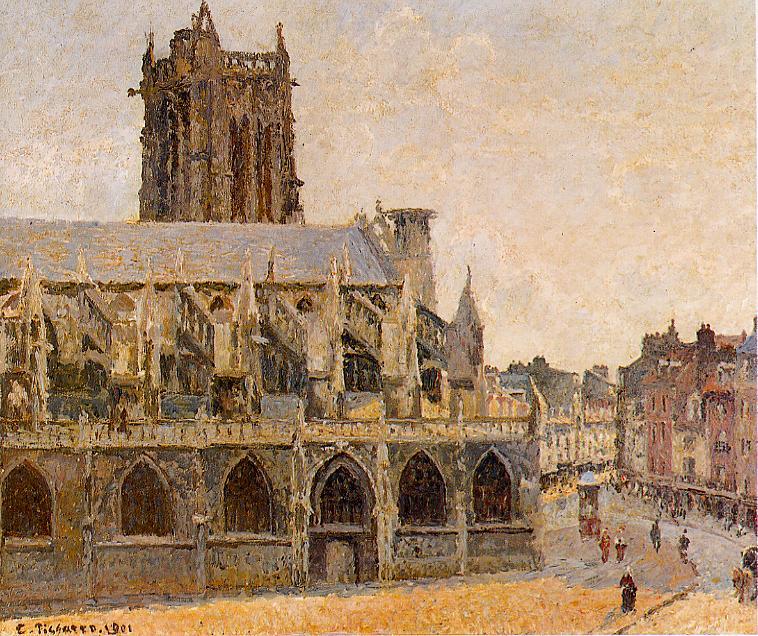

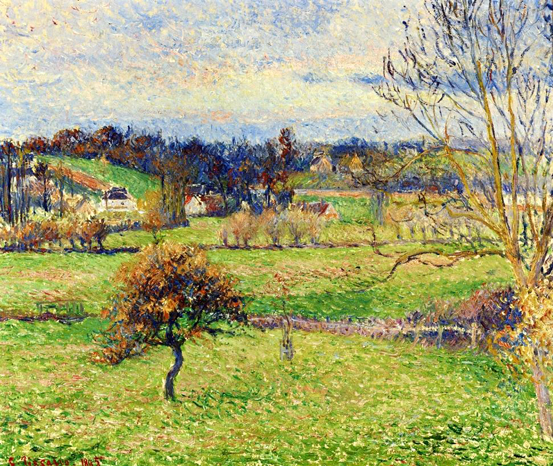

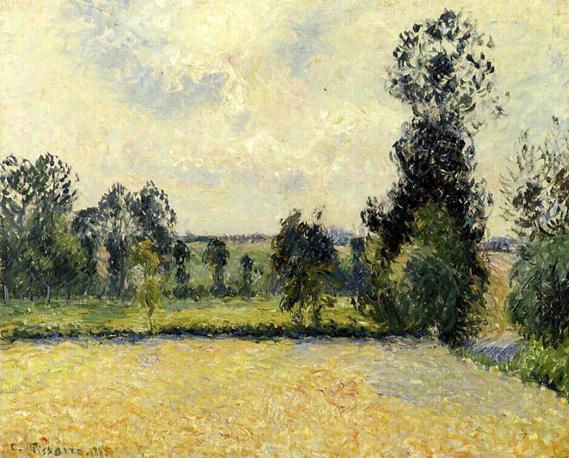

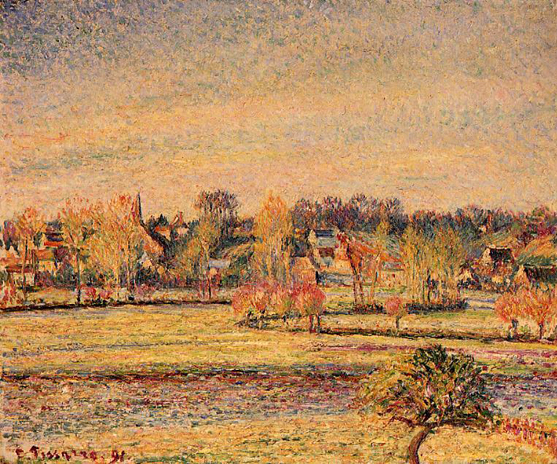

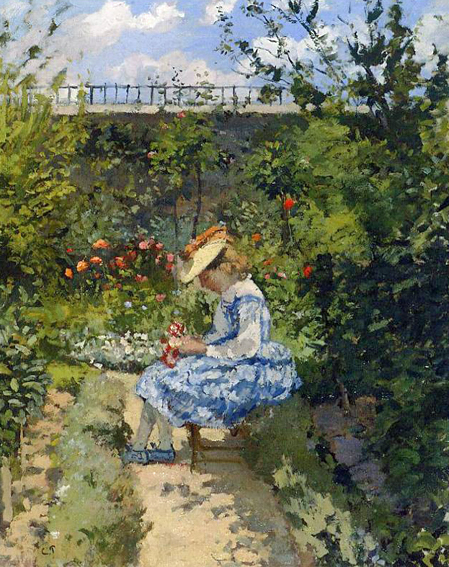

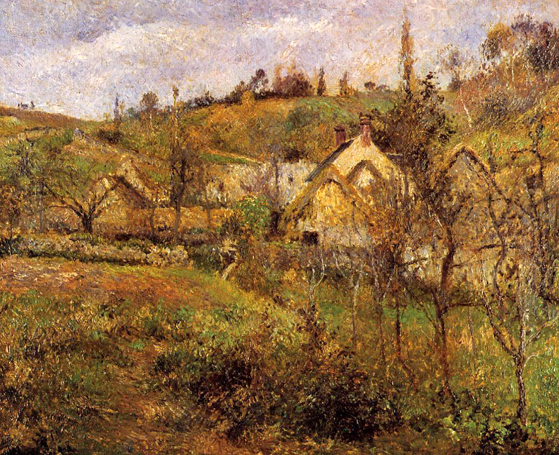

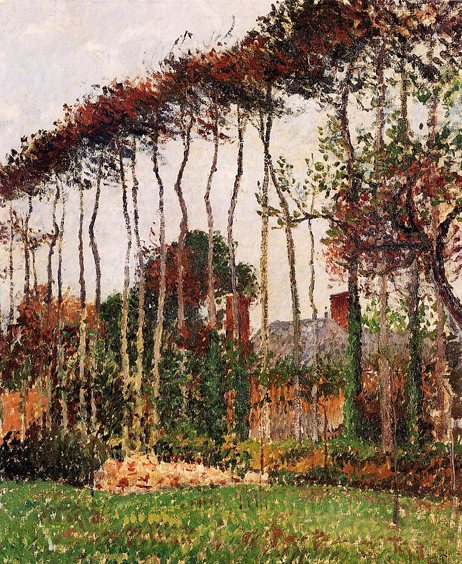

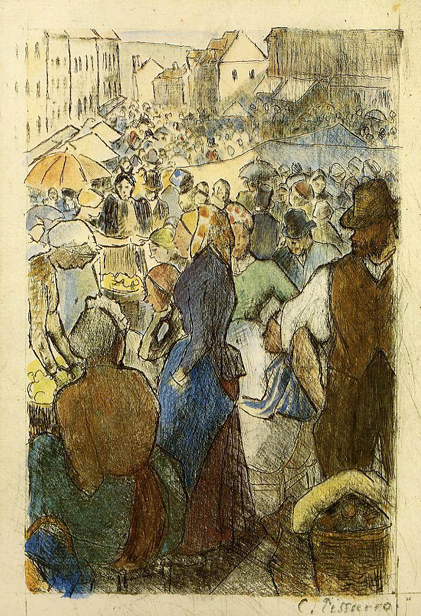

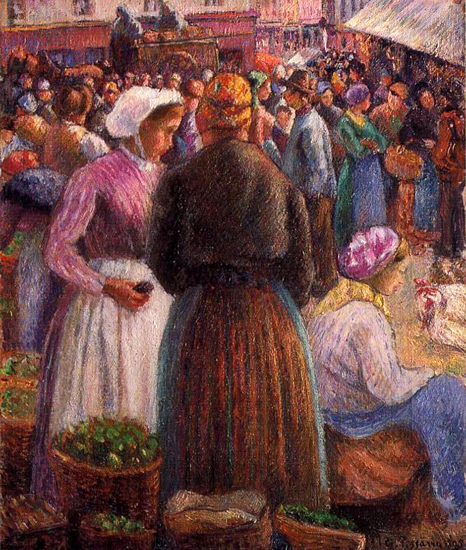

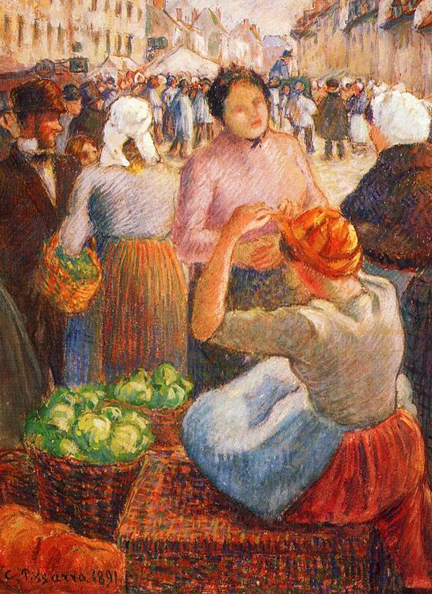

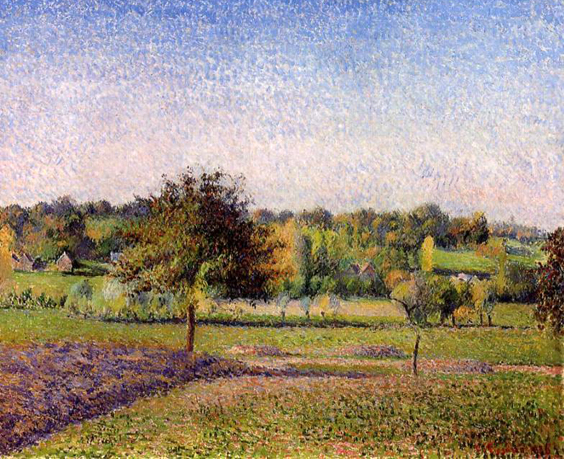

More Works of Camille Pissarro

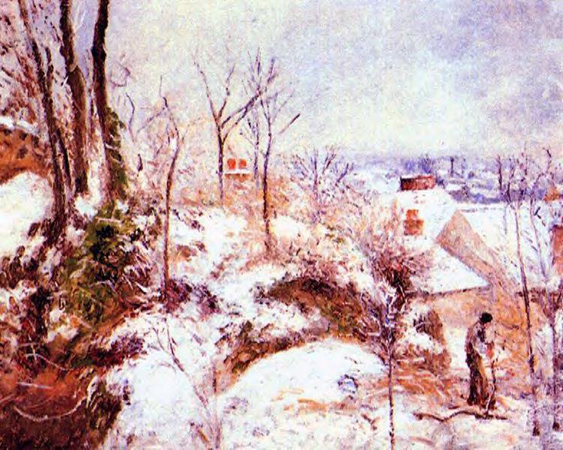

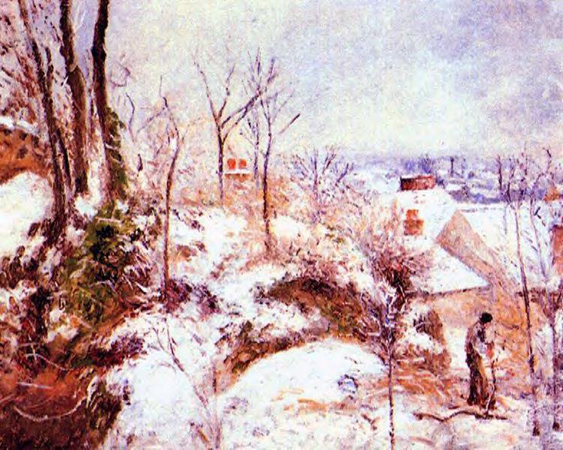

A Cottage in the Snow: 1879

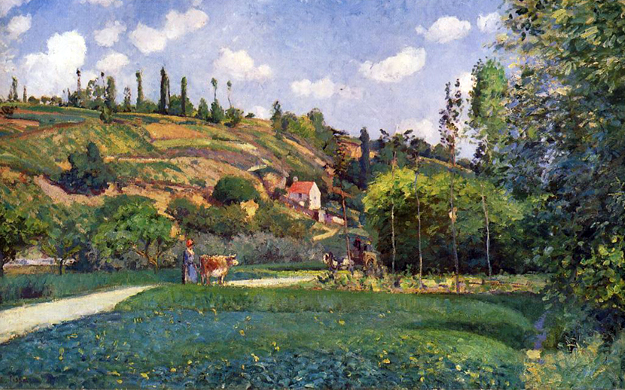

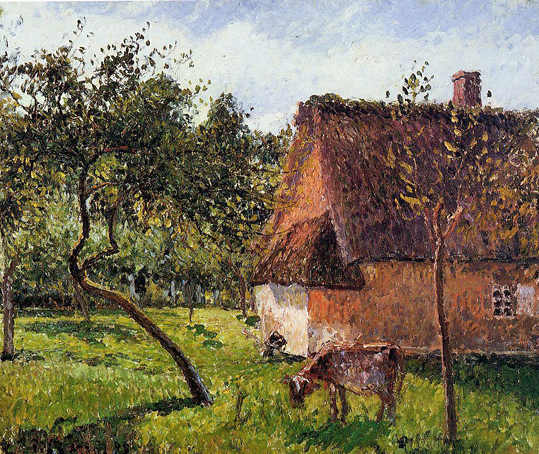

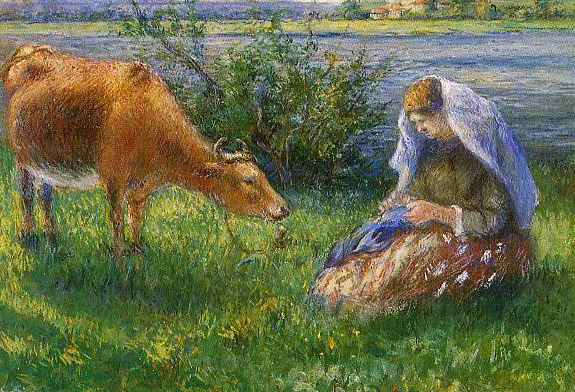

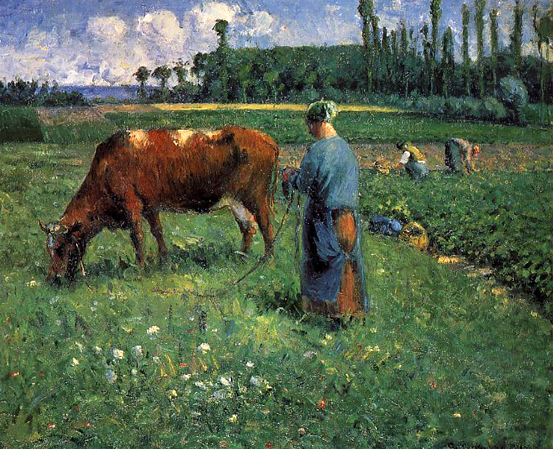

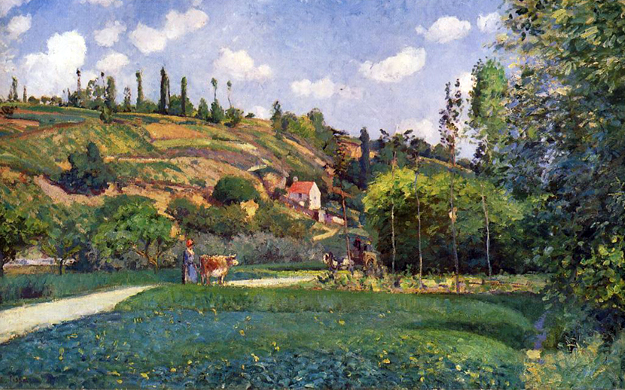

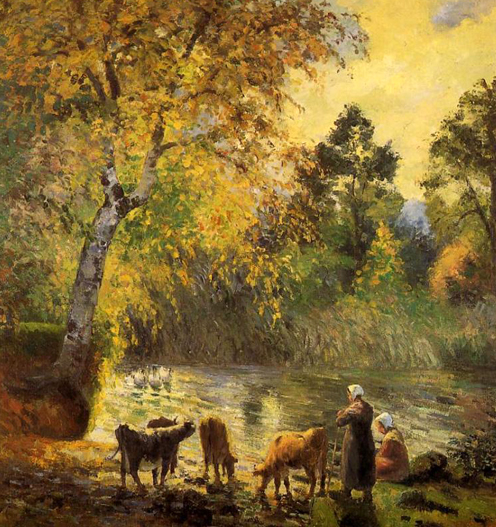

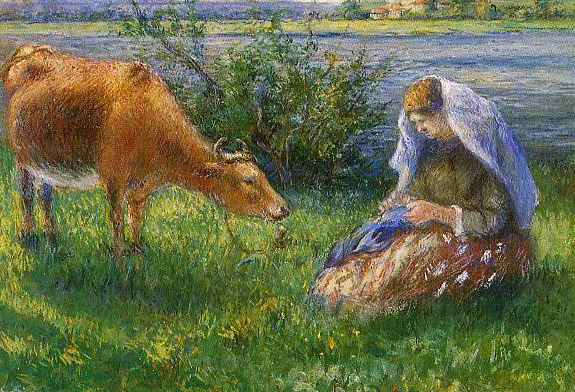

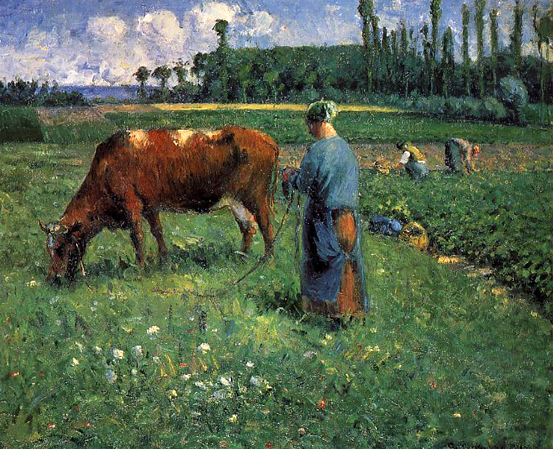

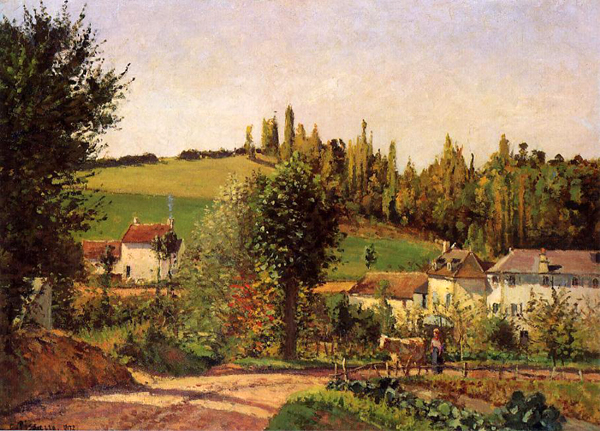

A Cowherd on the Route de Chou, Pontoise: 1874

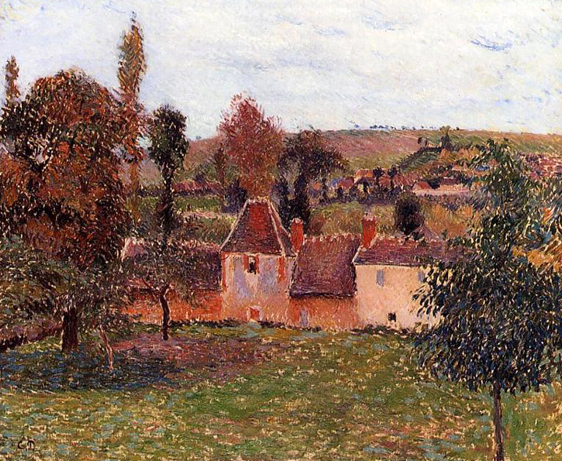

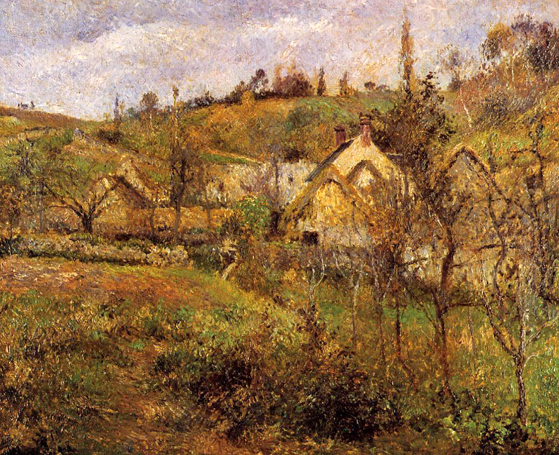

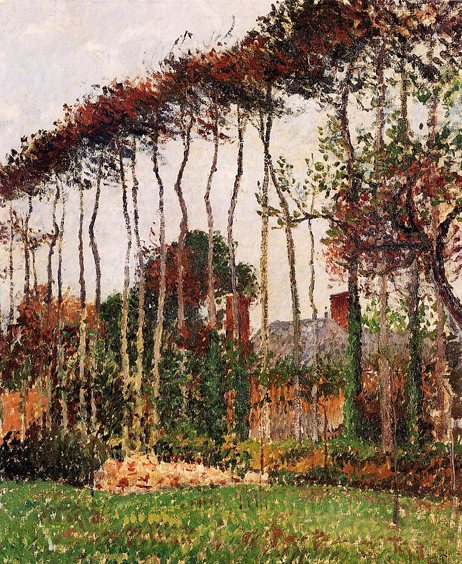

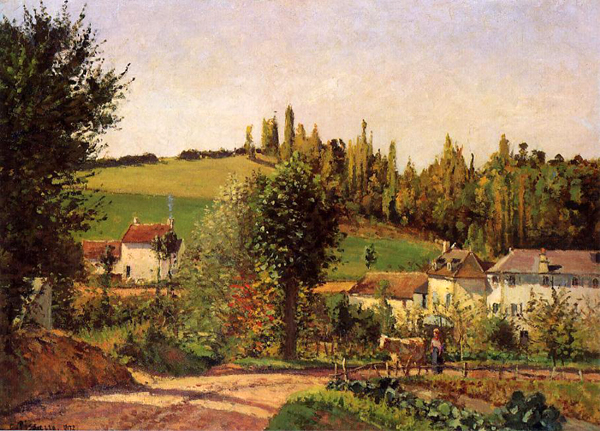

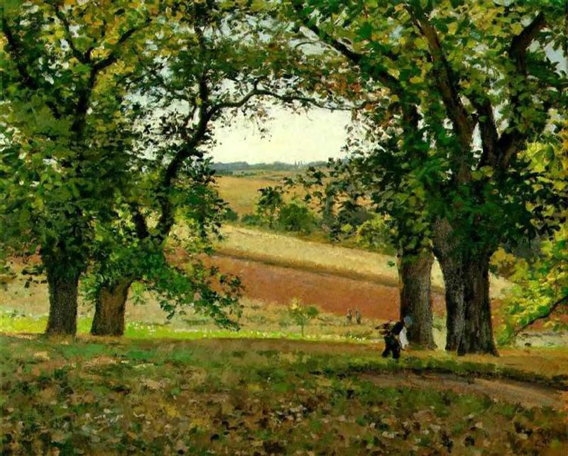

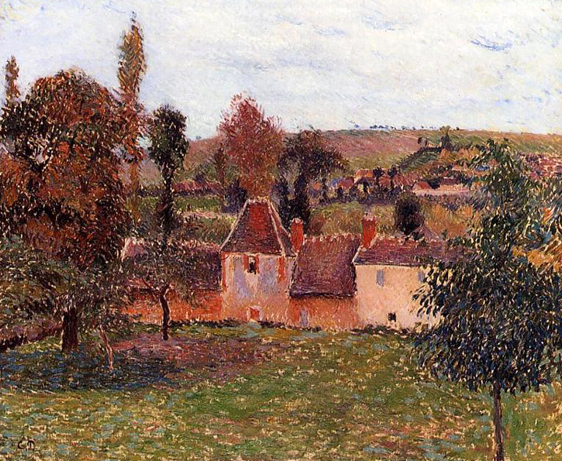

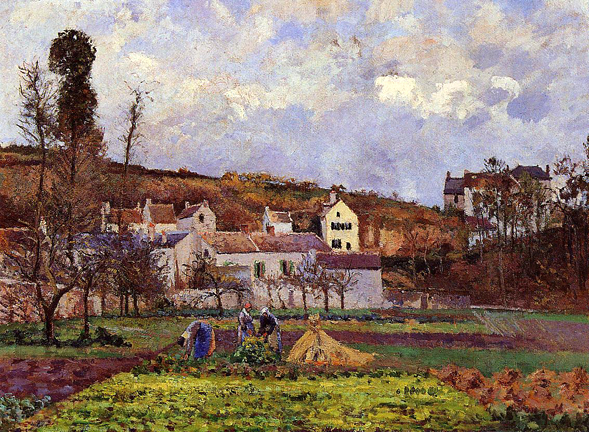

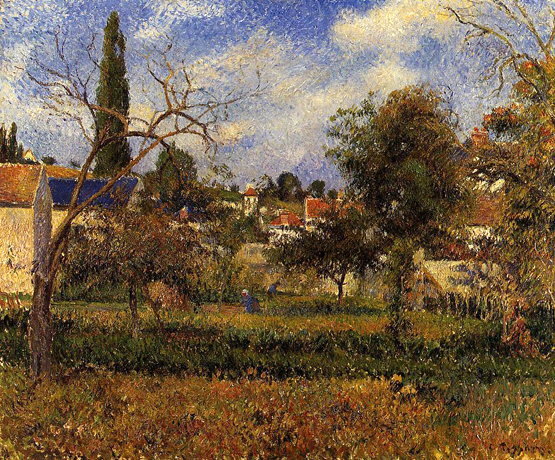

Pissarro lived in Pontoise, nestled in the Oise River valley just northwest of Paris, from 1866 to 1869, and he returned there in 1872. Over the next decade, Pissarro developed his approach to landscape painting, adapting the looser touch, broken brush strokes, and lighter palette of his younger Impressionist colleagues. He also enjoyed contact with Cézanne, who lived in nearby Auvers. With characteristic interest in the pulse of daily life, Pissarro routinely painted inhabited, as opposed to pure, landscapes, frequently depicting villagers walking on paths through the French countryside. Formerly known as "A Cowherd on the Route du Chou, Pontoise," this view actually shows the rue de Pontoise in the adjacent hamlet of Valhermeil in Auvers. Between 1873 and 1882, Pissarro painted some twenty works in the area, including a half dozen in which the red-roofed house adds a contrasting color note to the hillside's lush greenery.

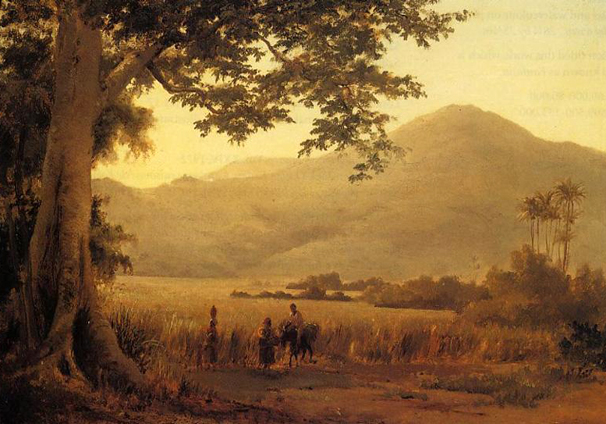

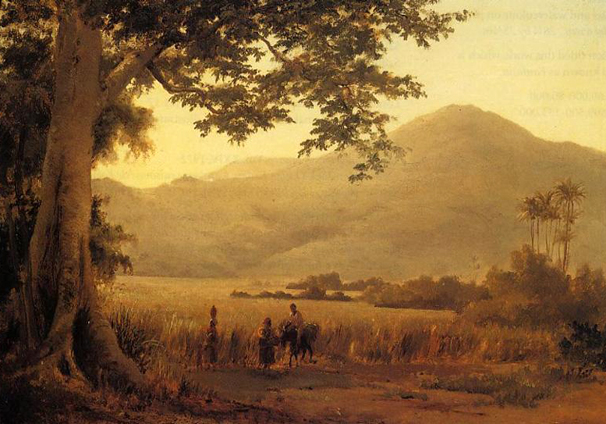

A Creek in Saint Thomas Antilles: 1856

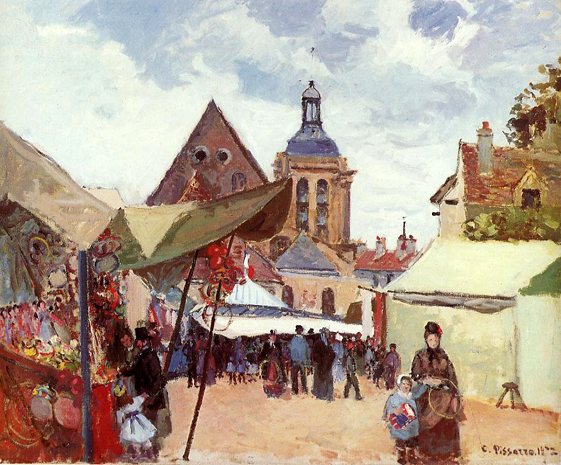

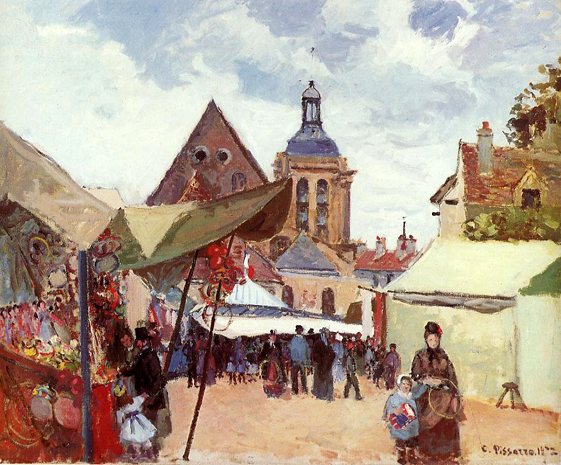

A Fair at l'Hermitage near Pontoise: 1878

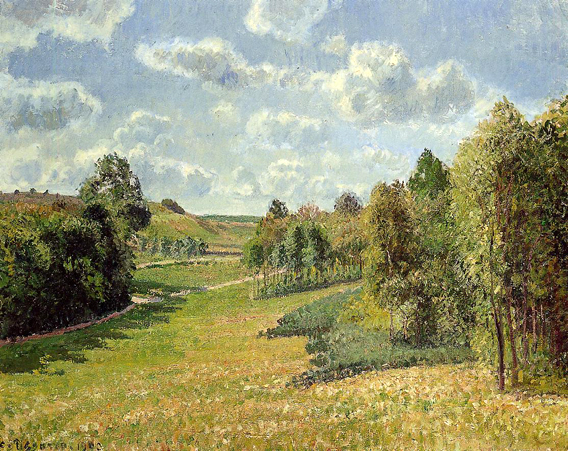

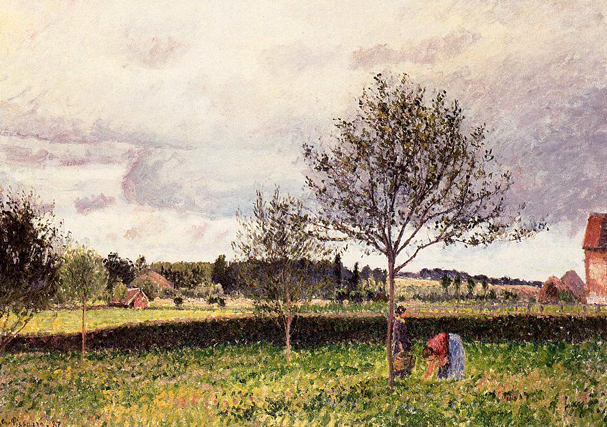

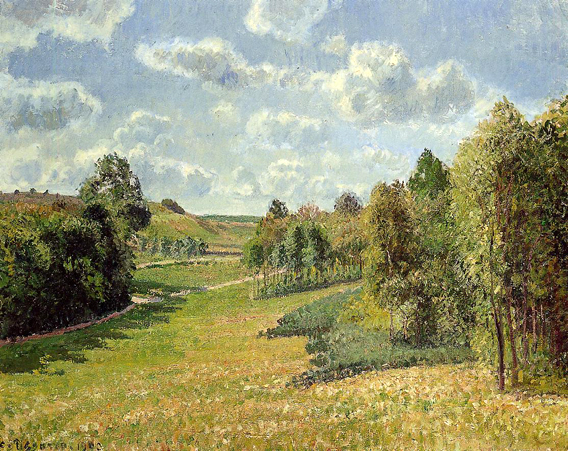

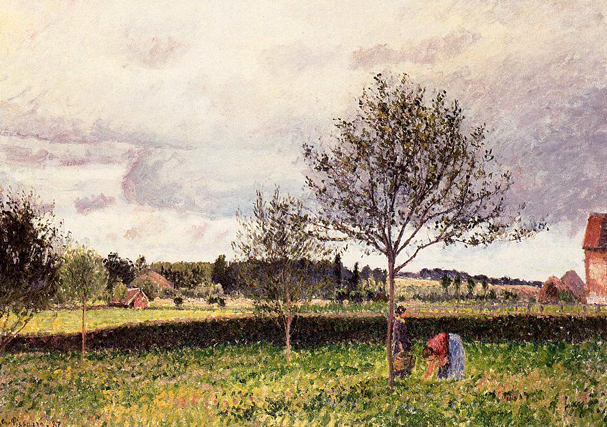

A Field in Varengeville: 1899

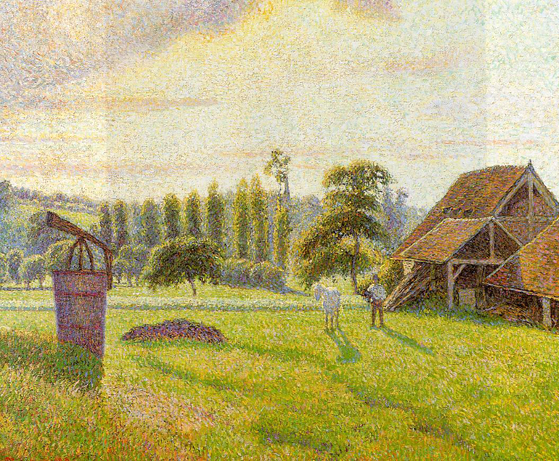

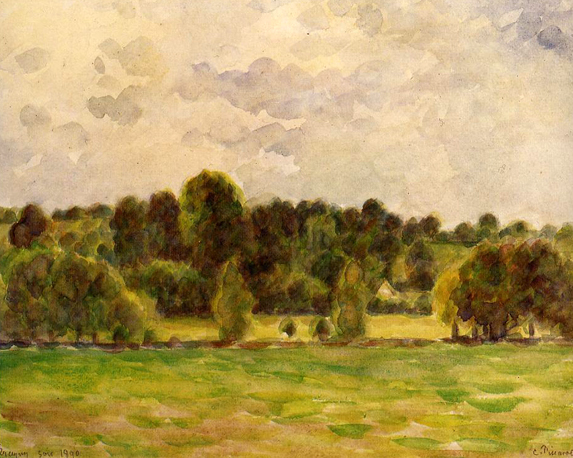

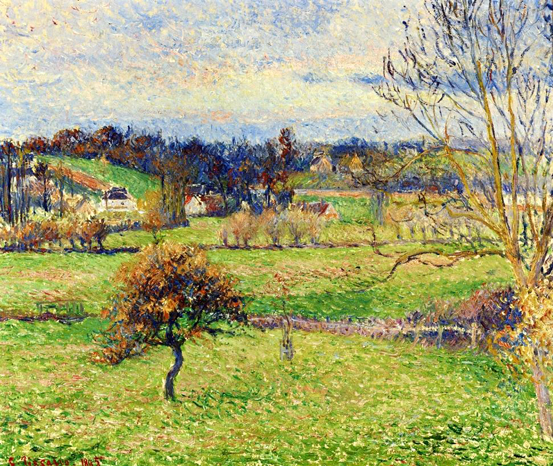

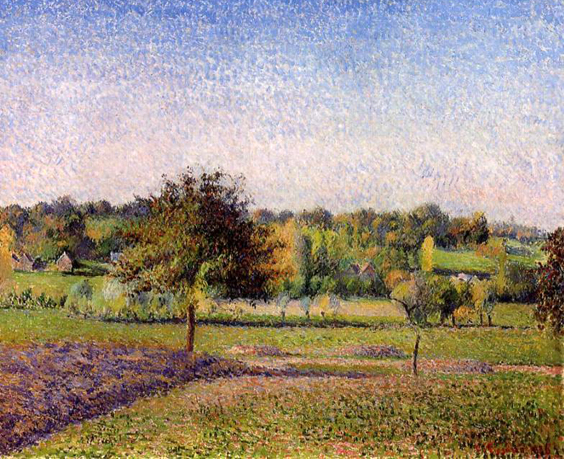

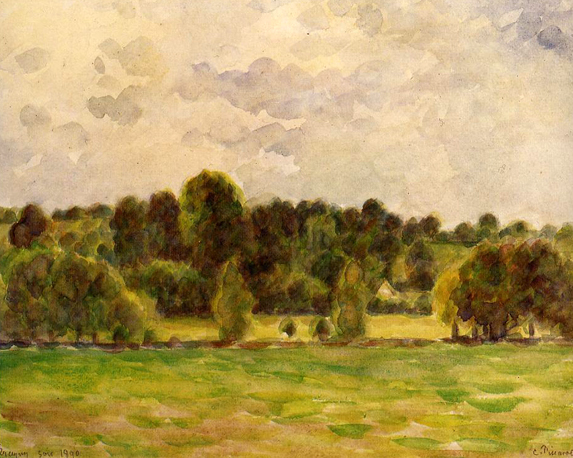

A Meadow in Eragny: 1889

A Meadow in Moret: 1901

A Path Across the Fields: 1879

A Path in the Woods, Pontoise: 1879

A Peasant in the Lane at l'Hermitage, Pontoise: 1876

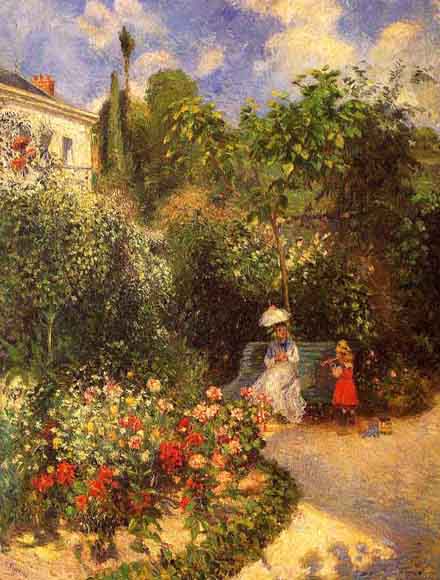

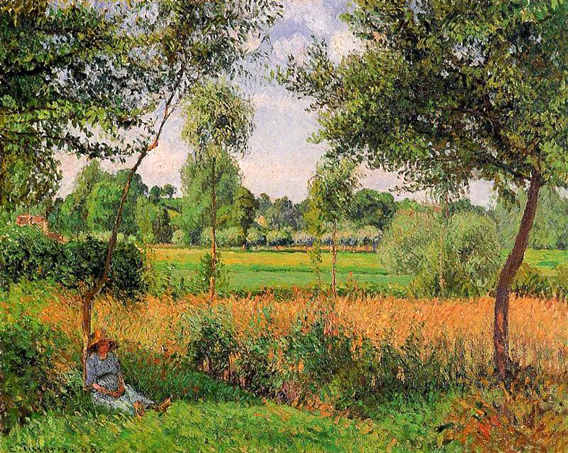

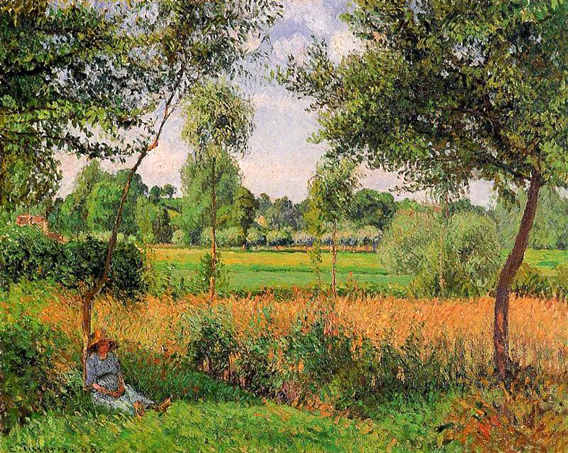

A Servant Seated in the Garden at Eragny: 1884

A Square in La Roche-Guyon: ca 1867

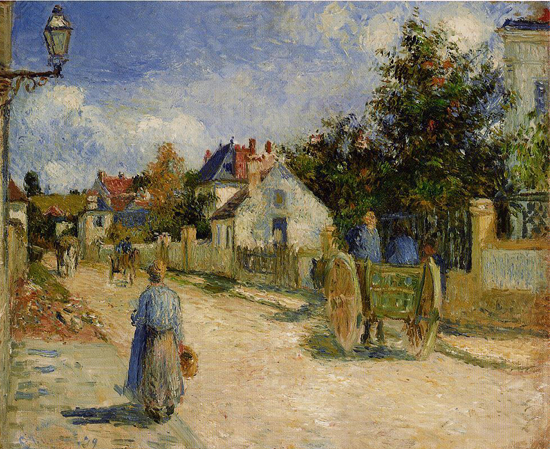

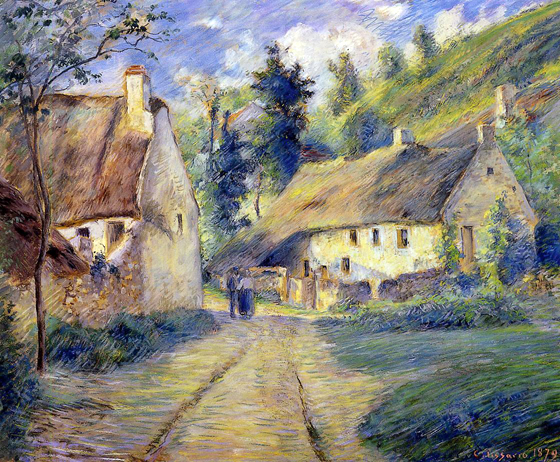

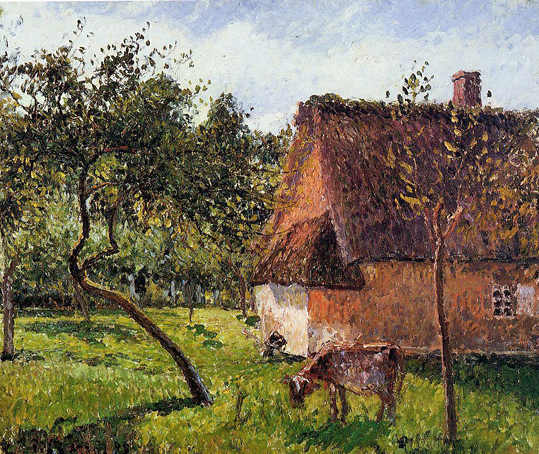

A Street in Auvers

(aka Thatched Cottages and a Cow): 1880

_1880.jpg)

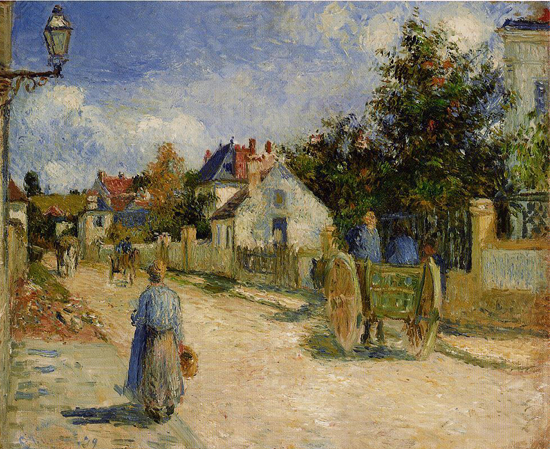

A Street in l'Hermitage, Pontoise: ca 1874

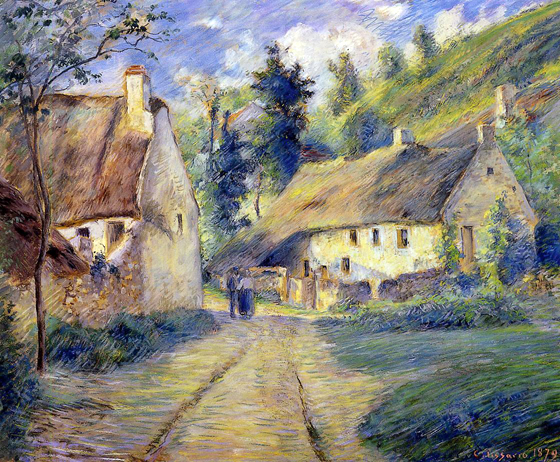

A Street in Pontoise: 1879

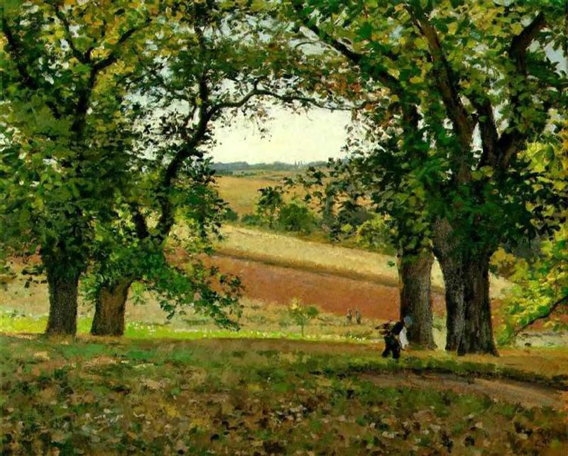

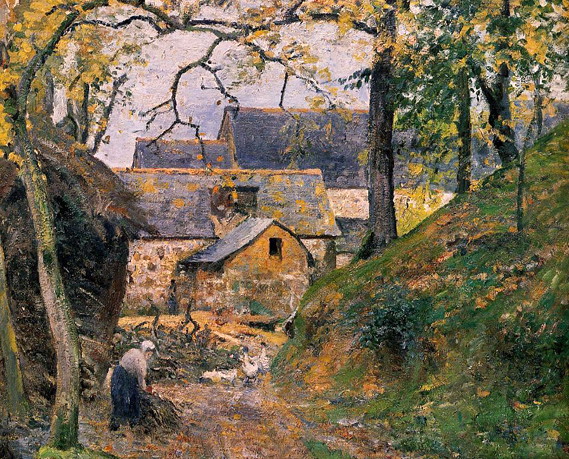

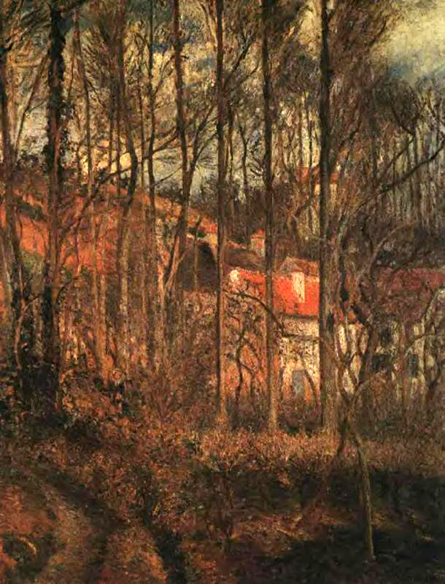

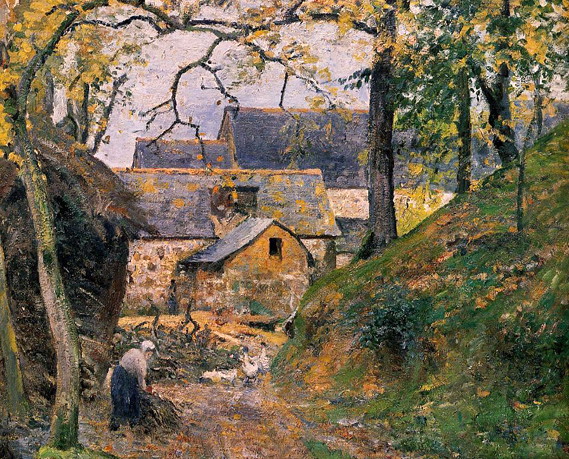

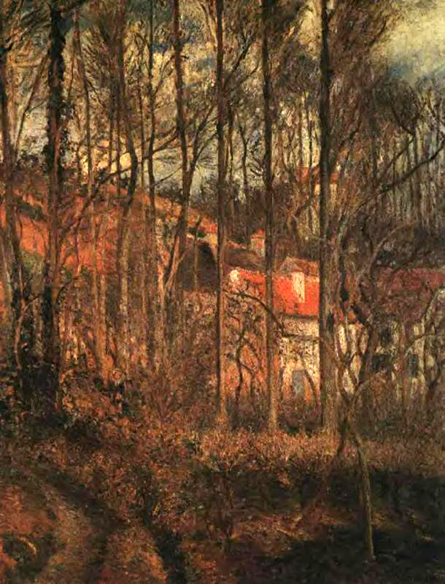

A Village through the Trees: ca 1868

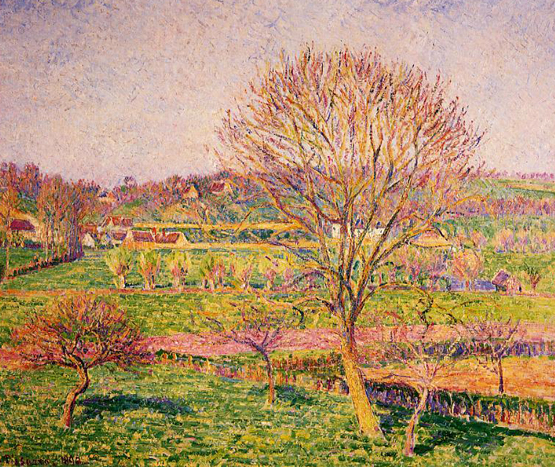

After the Rain - Autumn, Eragny: 1901

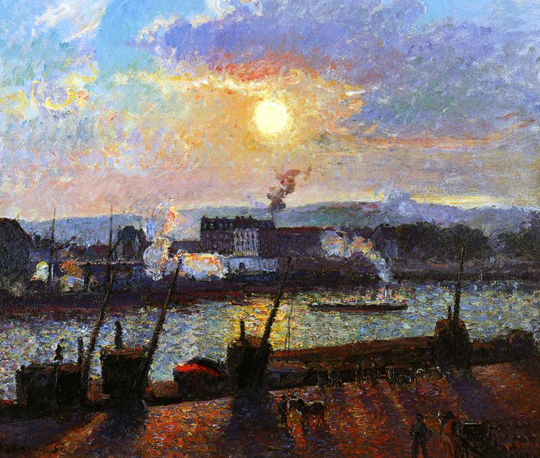

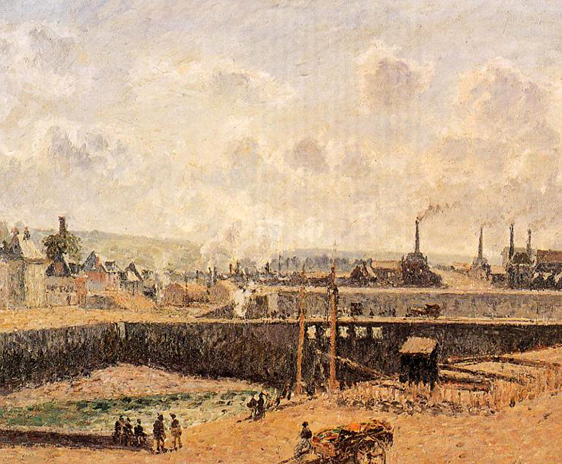

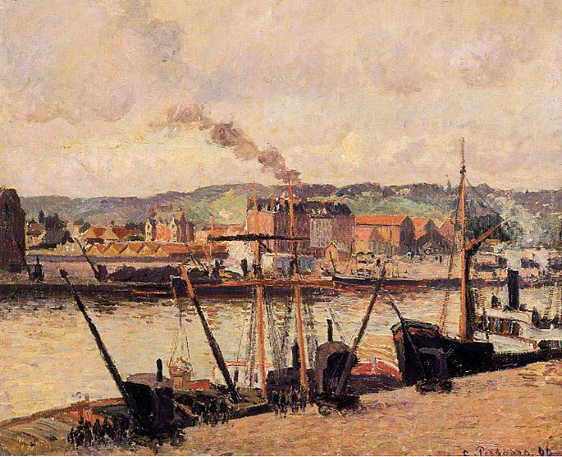

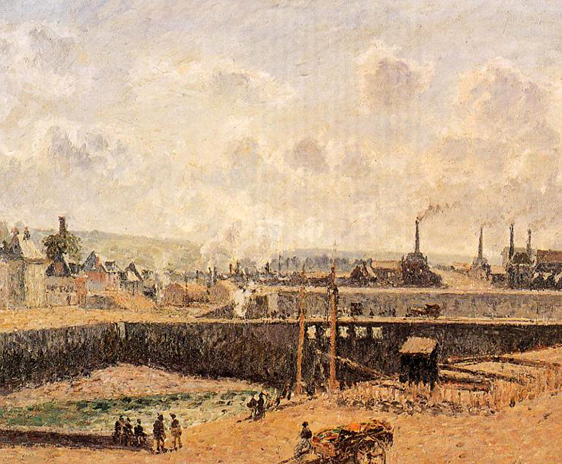

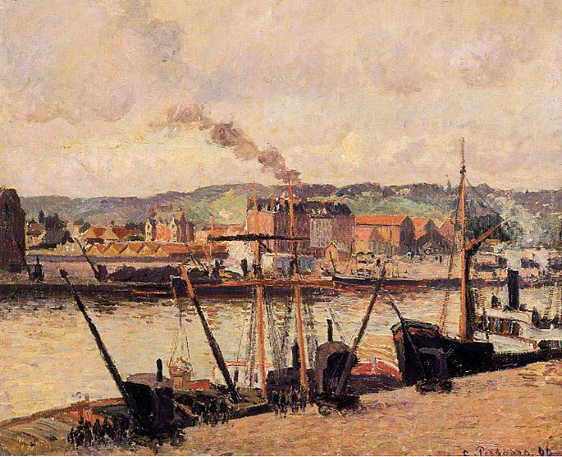

Afternoon Sun, Rouen: 1896

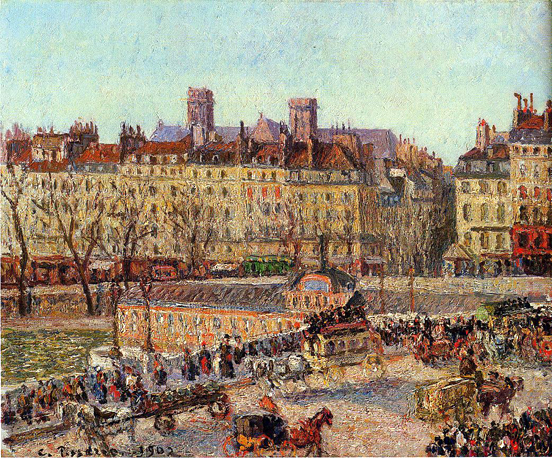

Afternoon Sun - the Inner Harbor, Dieppe: 1902

Afternoon the Dunquesne Basin, Dieppe Low Tide: 1902

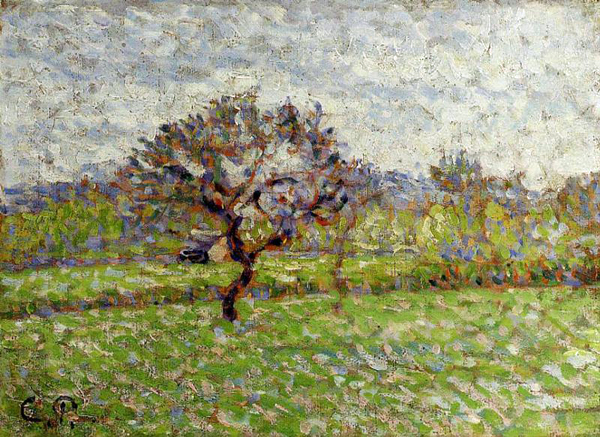

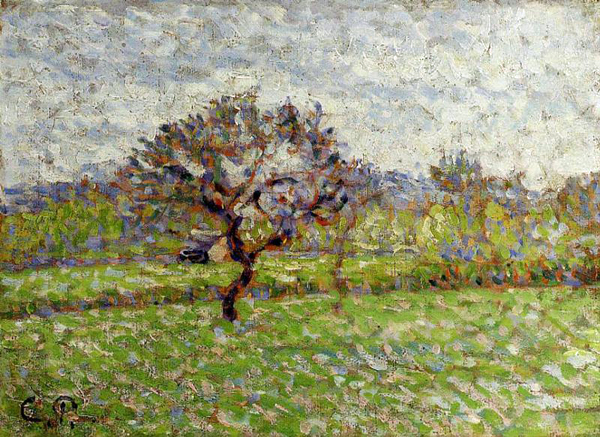

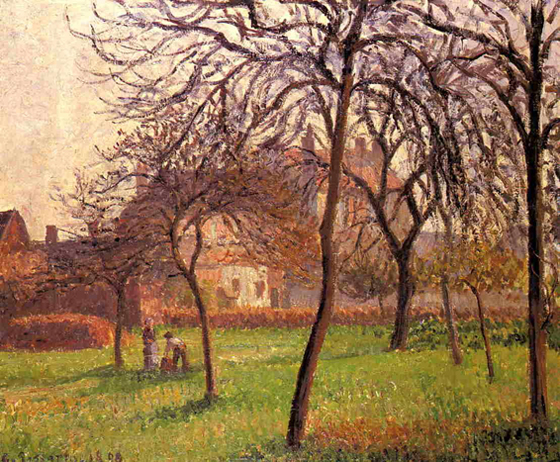

An Apple Tree at Eragny: 1887

Antilian Landscape, Saint Thomas: 1856

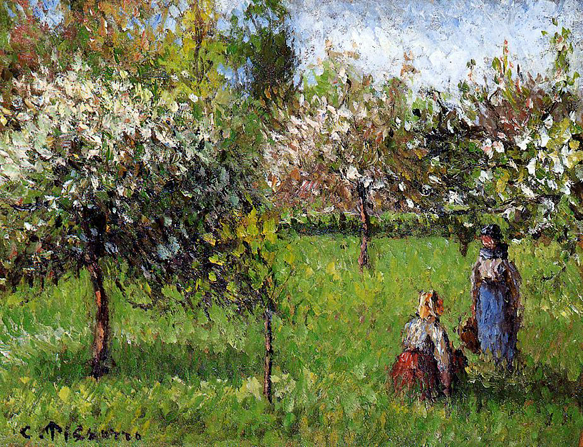

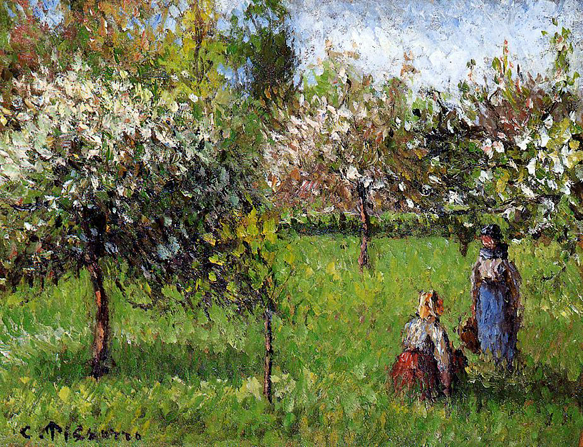

Apple Blossoms, Eragny: 1900

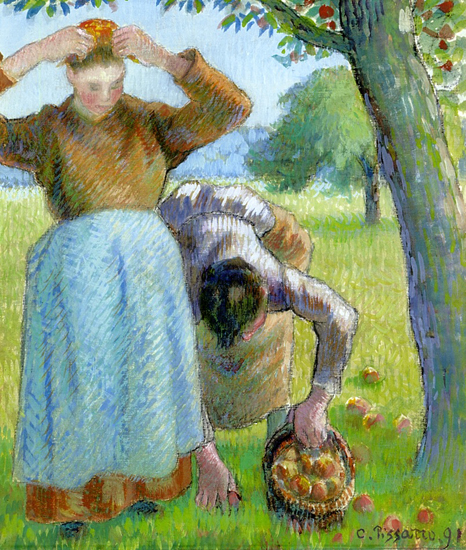

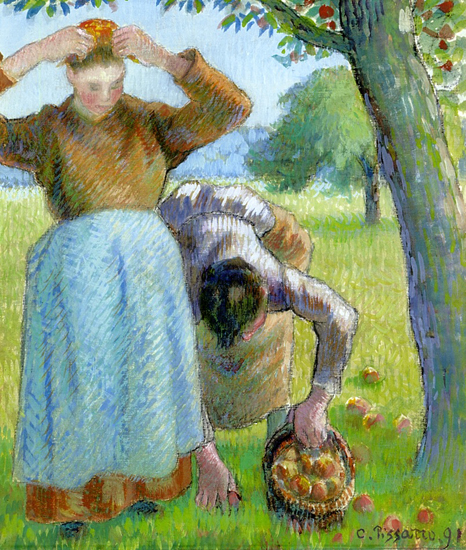

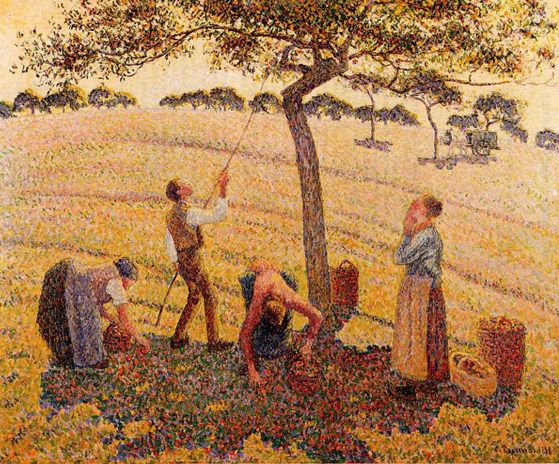

Apple Gatherers: 1891

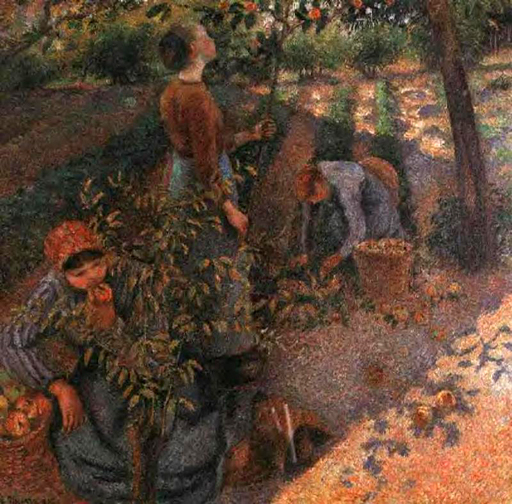

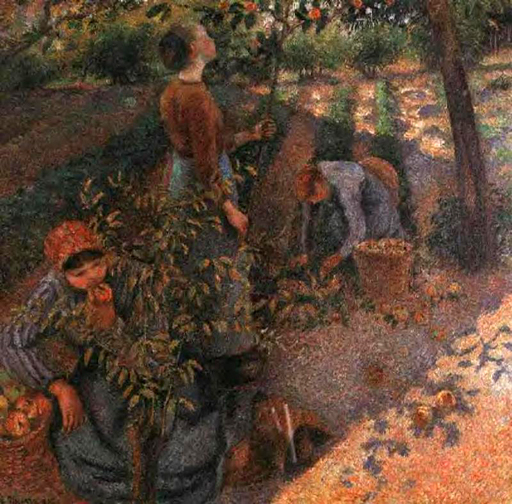

Apple Pickers, Eragny: 1888

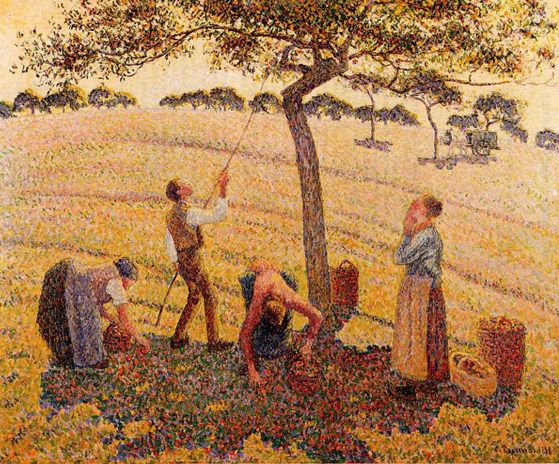

Apple Picking: 1886

Apple Tree at Eragny: 1884

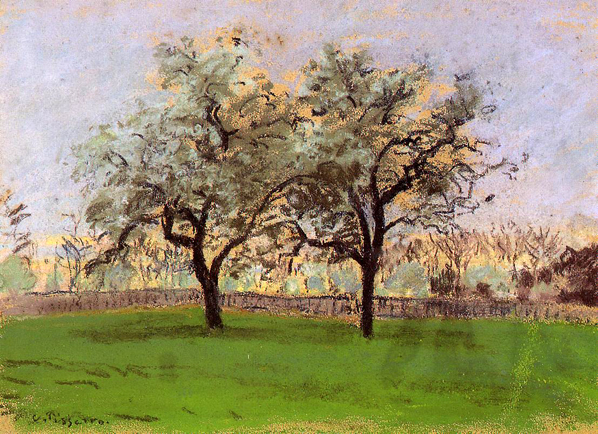

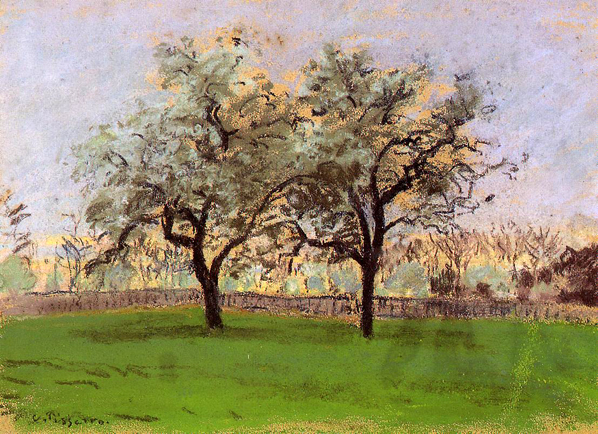

Apple Trees at Pontoise

(aka The Home of Pere Gallien): 1868

_1868.jpg)

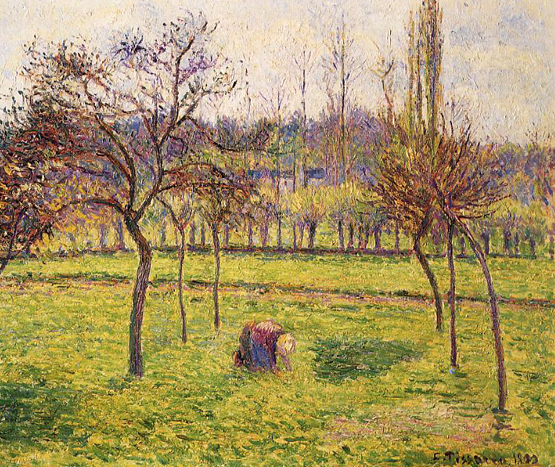

Apple Trees in a Field: 1892

Apple Trees Sunset, Eragny: 1896

Apples Trees at Pontoise: 1872

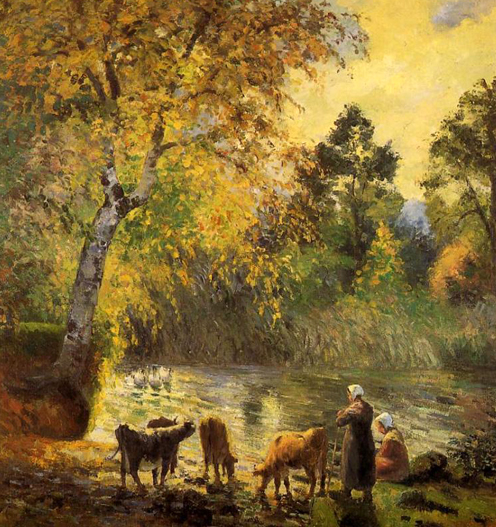

Autumn

(aka Path in the Woods): 1876

_1876.jpg)

Autumn Landscape near Pontoise

(aka Autumn Landscape near Louveciennes): 1871-72

_1871_72.jpg)

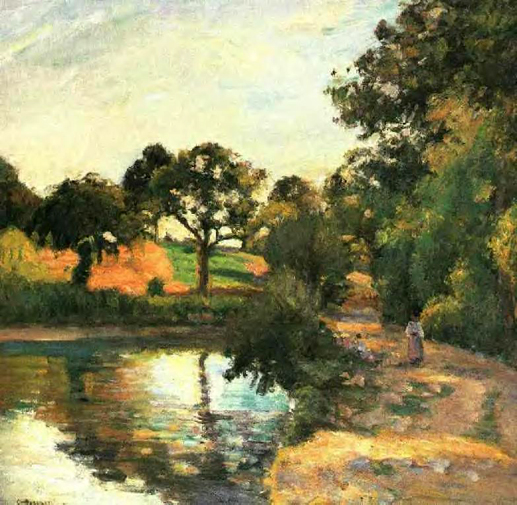

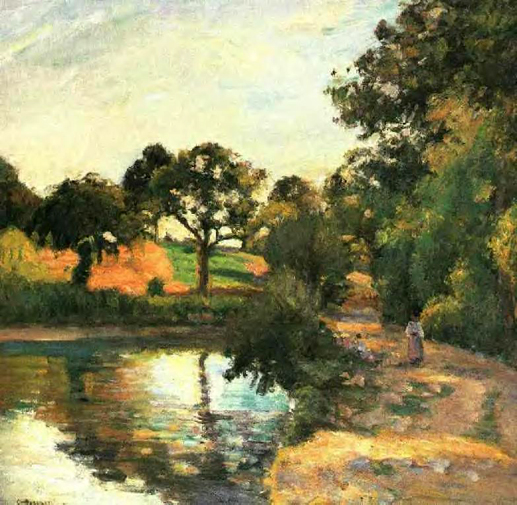

Autumn Montfoucault Pond: 1875

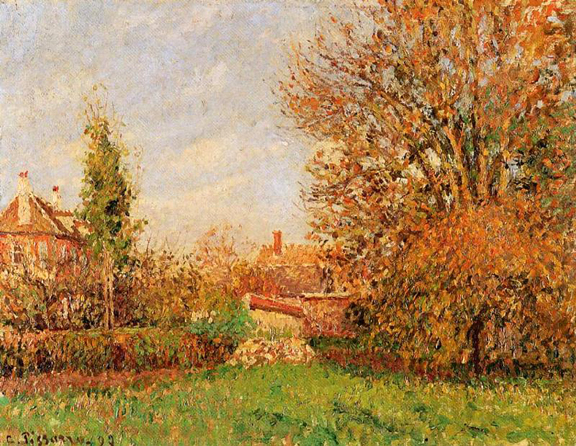

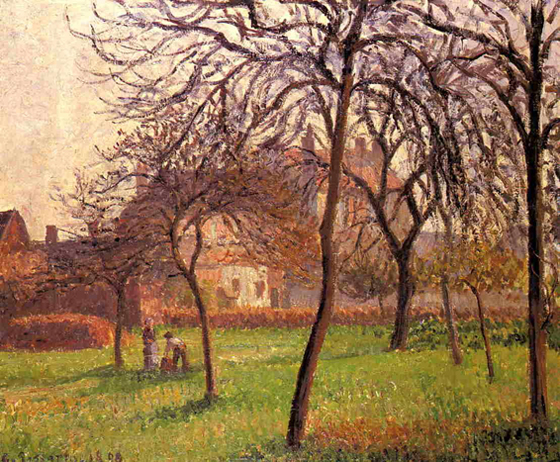

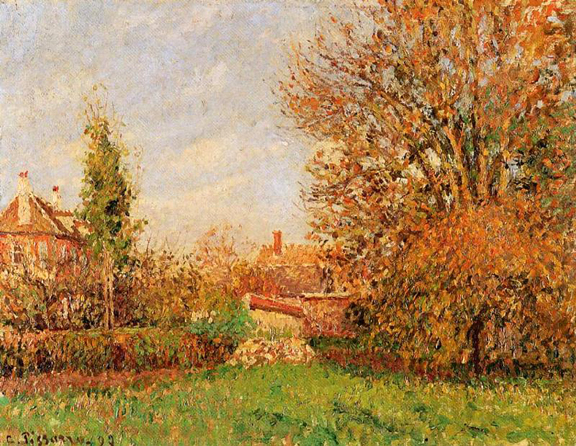

Autunm in Eragny: 1899

The Avenue de l'Opéra is a haussmanian avenue in the centre of Paris, France. It runs from the Louvre to the Palais Garnier, which was Paris main opera until it was replaced by the opéra Bastille.

Avenue de l'Opera - Morning Sunshine: 1898

Avenue de l'Opera - Place du Thretre Francais - Misty Weather: 1898

Avenue de l'Opera - Rain Effect: 1898

Avenue de l'Opera - Snow Effect: 1898

Avenue de l'Opera - Snow Effect: 1899

Avenue de l'Opera - Sunshine Winter Morning: 1898

Banks of a River with Barge: 1864

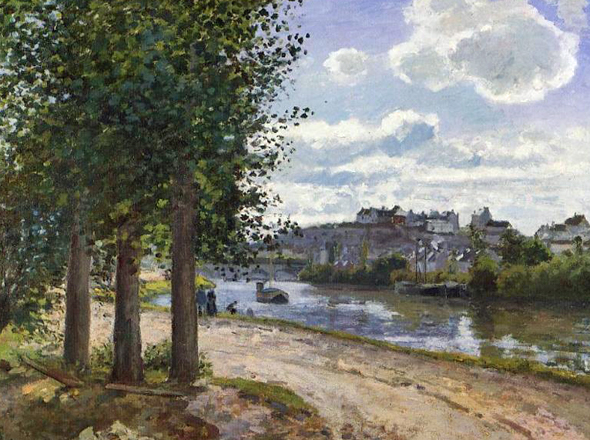

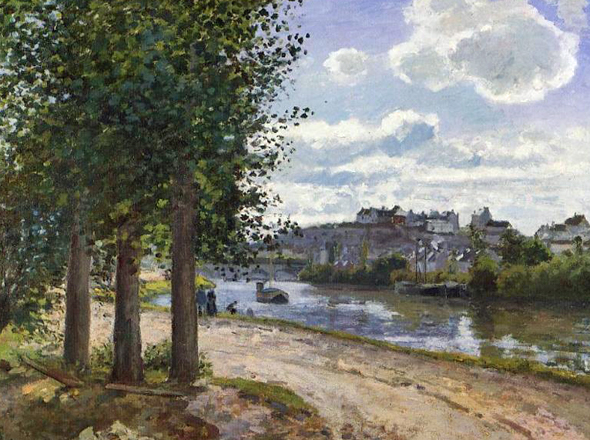

Banks of the Oise: 1872

Banks of the Oise in Pontoise: 1870

Barges at Le Roche Guyon: 1865

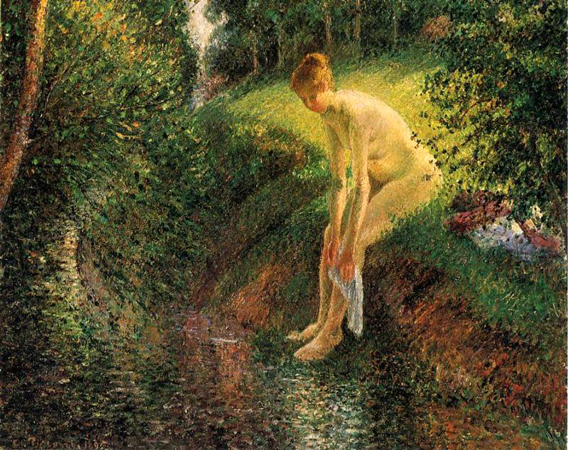

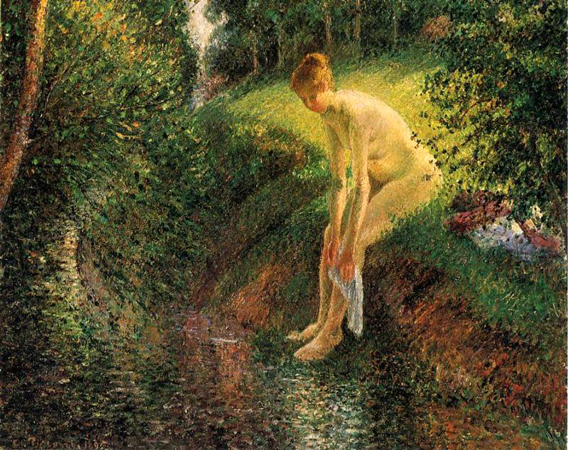

Bather in the Woods: 1895

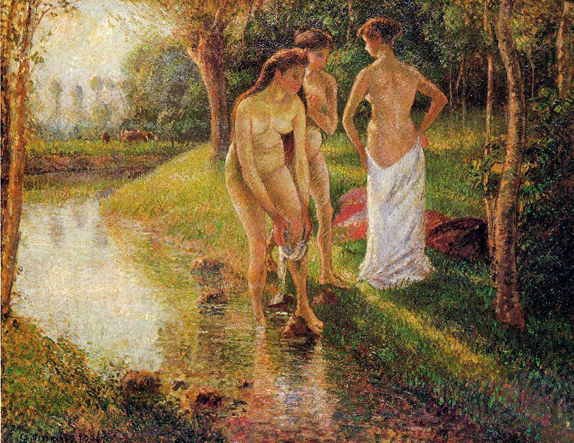

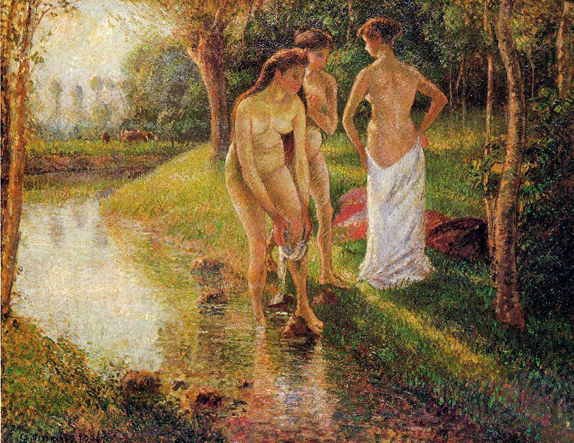

Bathers: 1894

Bathers: 1895

Bathers: 1896

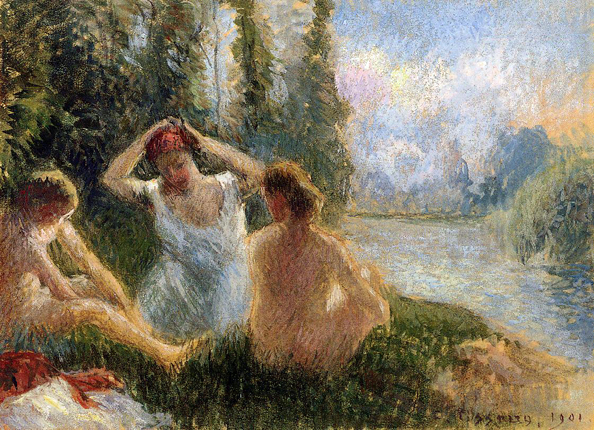

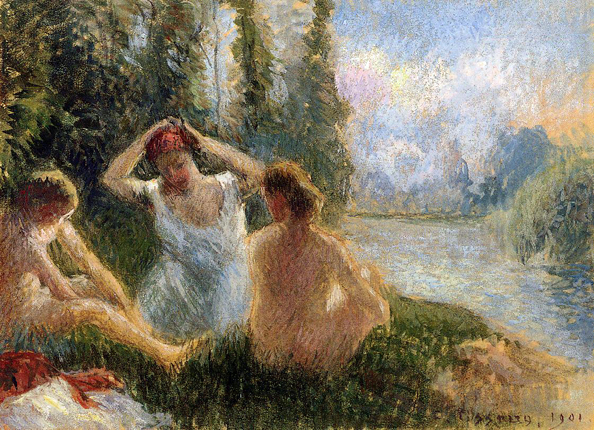

Bathers Seated on the Banks of a River: 1901

Bathing Goose Maidens

Berneval Meadows Morning: 1900

Big Walnut Tree at Eragny: 1892

Boats at Dock

Boats Sunset, Rouen: 1898

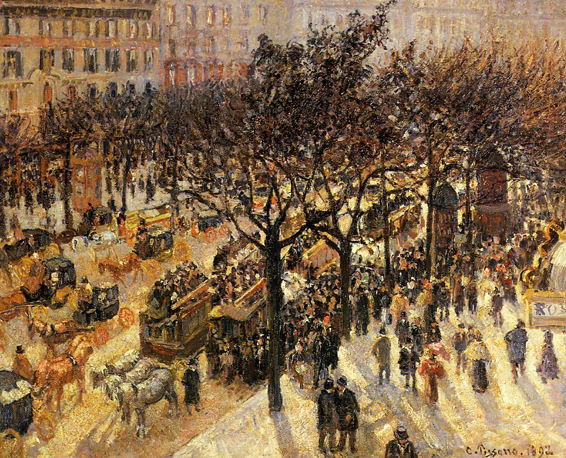

Boulevard de Clichy - Winter Sunlight Effect: 1880

Boulevard des Batignolles: 1878-79

Boulevard des Italiens - Afternoon: 1897

Boulevard des Italiens - Morning Sunlight: 1897

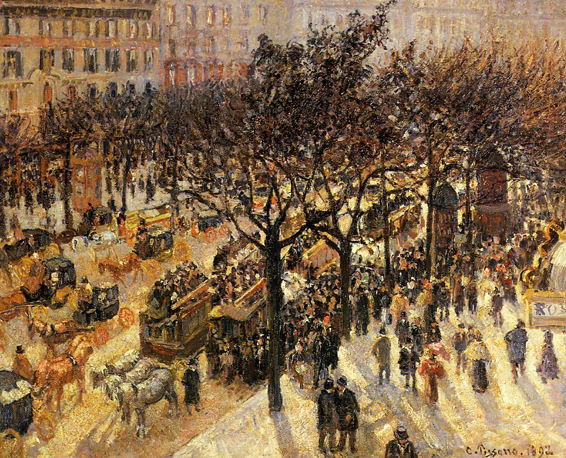

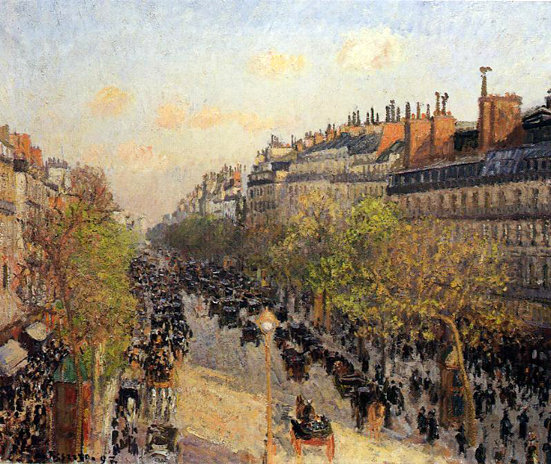

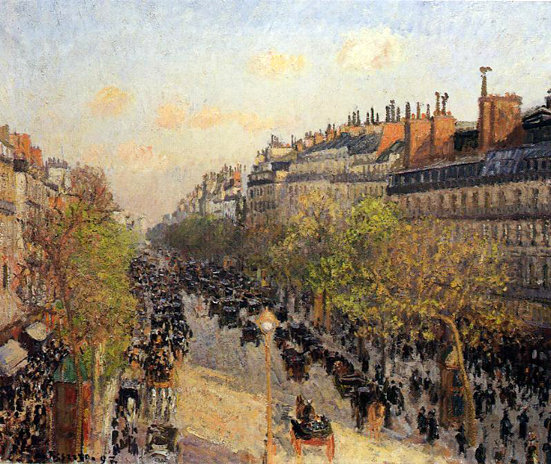

The Boulevard Montmartre is one of the four grand boulevards of Paris. It was constructed in 1763. Contrary to what its name may suggest, the road is not situated on the hills of Montmartre. It is the easternmost of the grand boulevards.

Boulevard Montmartre - Afternoon in the Rain

(aka Boulevard Montmartre Apres-midi temps de pluie): 1897

_1897.jpg)

Boulevard Montmartre - Afternoon Sunlight

(aka Boulevard Montmartre Apres midi soleil): 1897

_1897.jpg)

Boulevard Montmartre - Foggy Morning: 1897

Boulevard Montmartre - Mardi Gras: 1897

Boulevard Montmartre - Morning Grey Weather: 1897

Boulevard Montmartre - Morning Sunlight and Mist: 1897

Boulevard Montmartre - Night Effect

(aka Boulevard Montmartre effet de nuit): 1897

_1897.jpg)

Boulevard Montmartre - Spring: 1897

Boulevard Montmartre - Spring Rain: 1897

Boulevard Montmartre - Spring: 1897

Boulevard Montmartre - Sunset: 1897

Boulevard Montmartre - Winter Morning: 1897

Bourgeois House in l'Hermitage, Pontoise: 1873

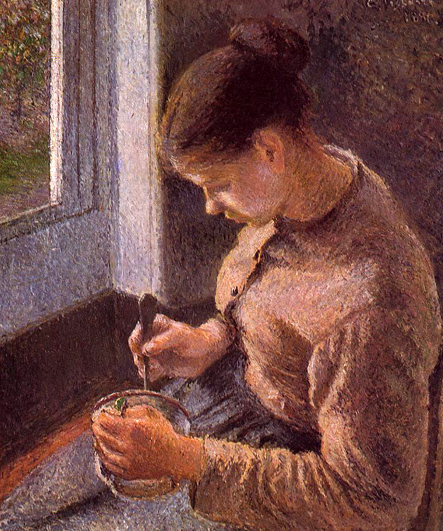

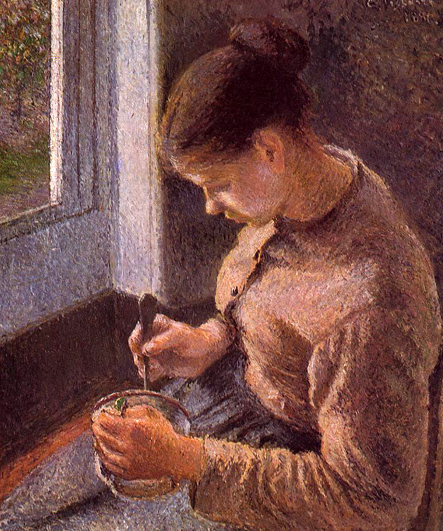

Breakfast - Young Peasant Woman Taking Her Coffee: 1881

Brickworks at Eragny: 1888

Bridge at Montfoucault: 1874

By the Oise at Pontoise: 1867

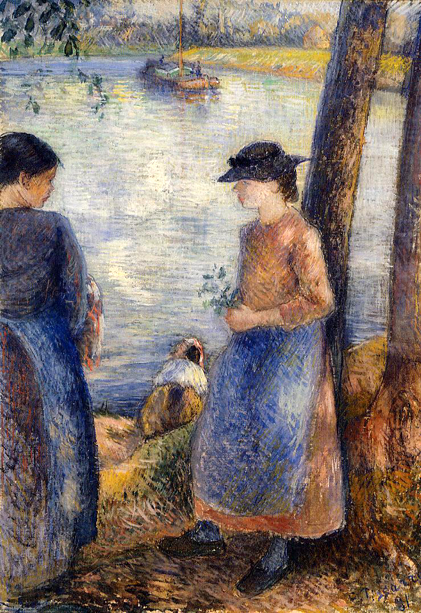

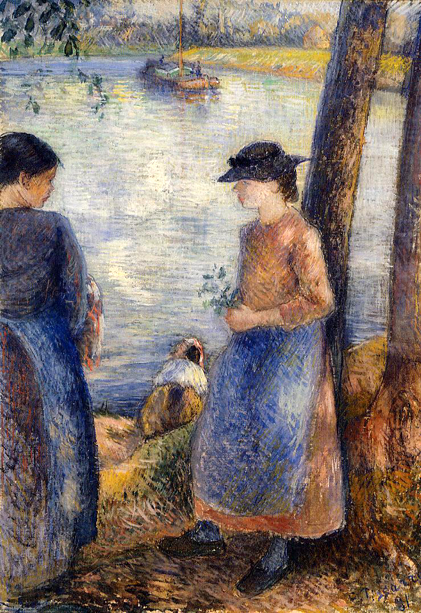

By the Water: 1881

Chaponval Landscape: 1880

Charing Cross Bridge, London: 1890

Thames Charing Cross Railway Bridge

Chestnut Orchard in Winter: 1872

Chestnut Trees at Osny: 1873

Chestnut Trees, Louveciennes Spring: 1870

Children in a Garden at Eragny: 1897

Church at Kew: 1892

Saint Anne's Church, Kew

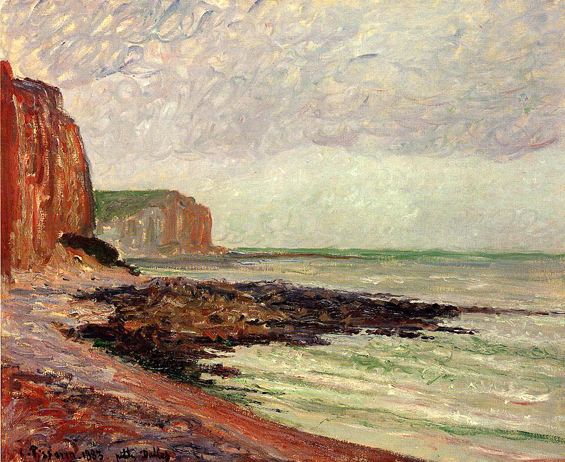

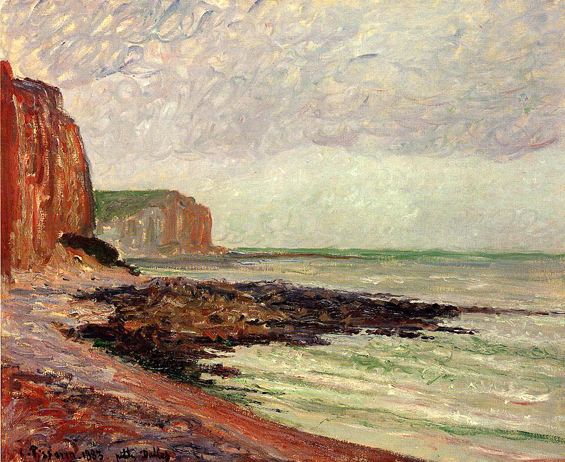

Cliffs at Petit Dalles: 1883

Corner of the Garden in Eragny: 1897

Cottage at Pontoise in the Snow: 1879

Cottages at Auvers near Pontoise: 1879

Cour du Havre Gare Saint Lazare: 1893

Painted in 1893, 'La Place du Havre et la gare Saint-Lazare' was one of the very first group of Camille Pissarro's views of Paris that have come to be recognized as such revolutionary Impressionist masterpieces. The small group of pictures that Pissarro painted from his hotel room near the Gare Saint-Lazare at the end of 1892 and beginning of 1893 marked the beginning of a new strain in his pictures, as he captured the ever-shifting kaleidoscopic beauty of the hustle and bustle of urban life.

Cowgirl Eragny: 1887

Cowherd: 1883

Cowherd at Eragny: 1884

Cowherd in a Field at Eragny: 1890

Cowherd Pontoise: 1880

Cowherd Pontoise: 1882

Crossroads at l'Hermitage Pontoise: 1876

Dieppe - Dunquesne Basin Low Tide Sun Morning: 1902

Dieppe

Dieppe - Dunquesne Basin Sunlight Effect, Morning Low Tide

Ducks on the Pond at Montfoucault: 1874

Elderly Woman Mending Old Clothes, Moret: 1902

Enclosed Field at Eragny: 1896

Entering a Village: ca 1863

Entering the Forest of Marly

(Snow Effect): ca 1869

_ca_1869.jpg)

Entering the Village of Voisins: 1872

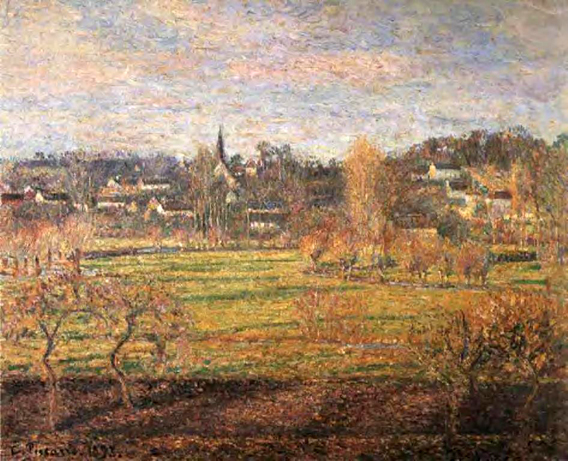

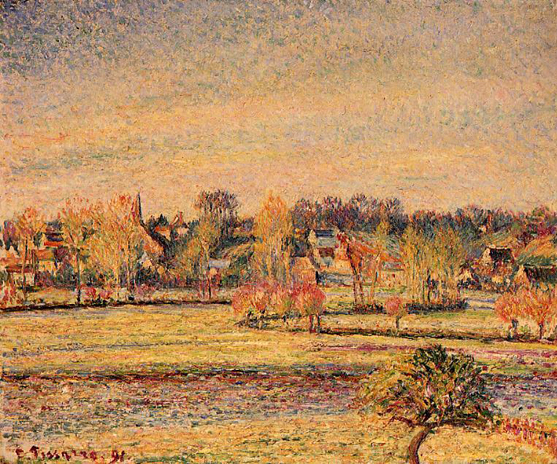

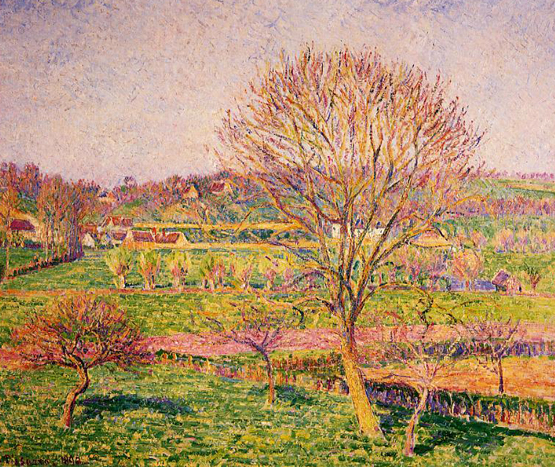

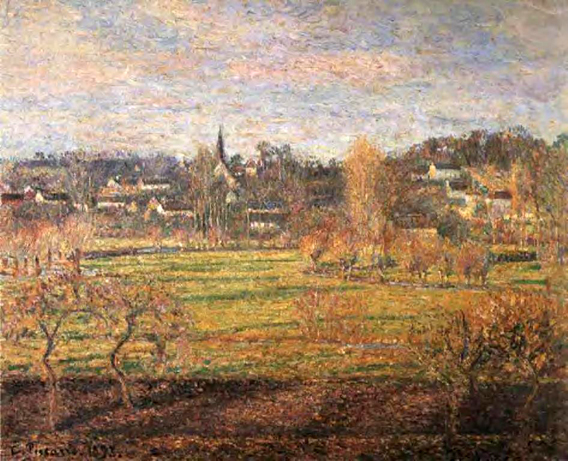

Eragny: 1890

Eragny Landscape Le Pre: 1897

Eragny Twilight: 1890

Eugene Murer at His Pastry Oven: 1877

Family Garden

Farm at Basincourt: ca 1884

Farm at Montfoucault: 1874

Farm at Montfoucault: 1874

Farmyard: 1863

Farmyard at the Maison Rouge, Pontoise: 1877

Farmyard in Pontoise: 1874

February Sunrise, Bazincourt: 1893

Field at Eragny: 1885

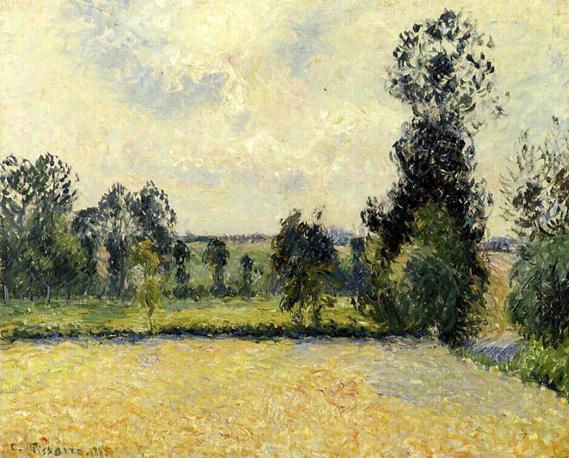

Field of Oats in Eragny: 1885

Fields: 1877

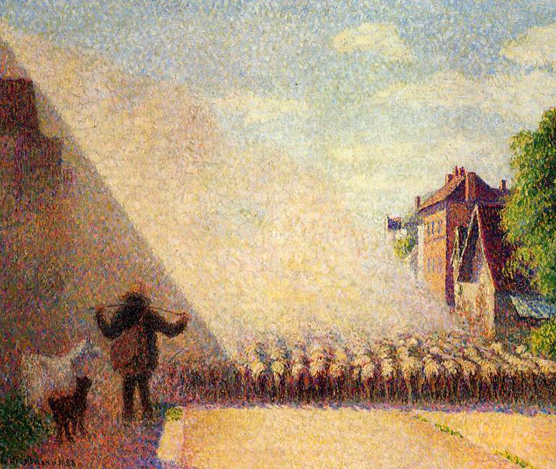

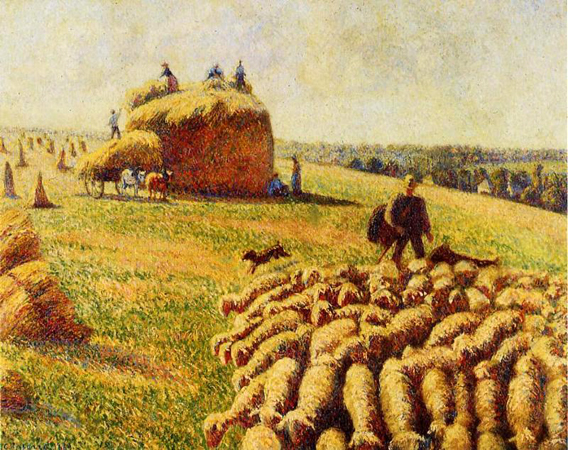

Flock of Sheep: 1888

Flock of Sheep in a Field after the Harvest: 1889

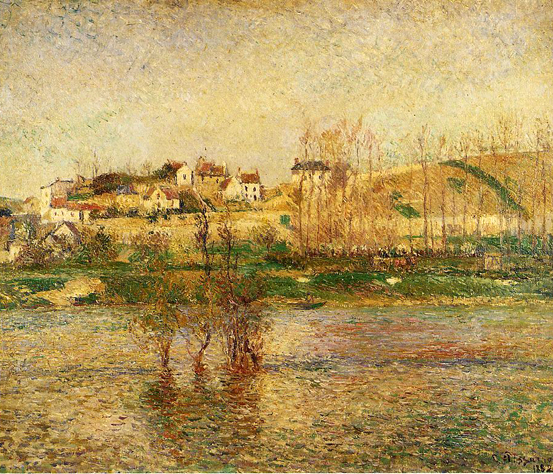

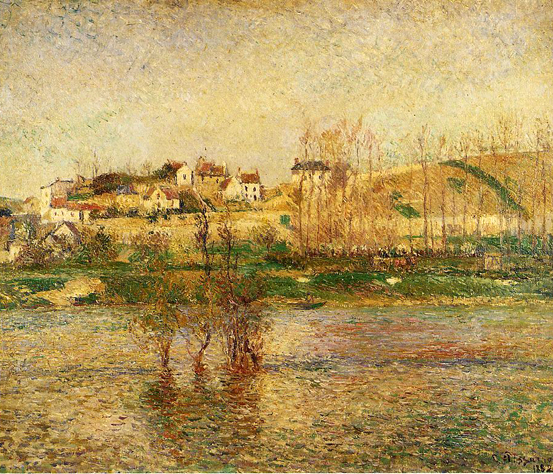

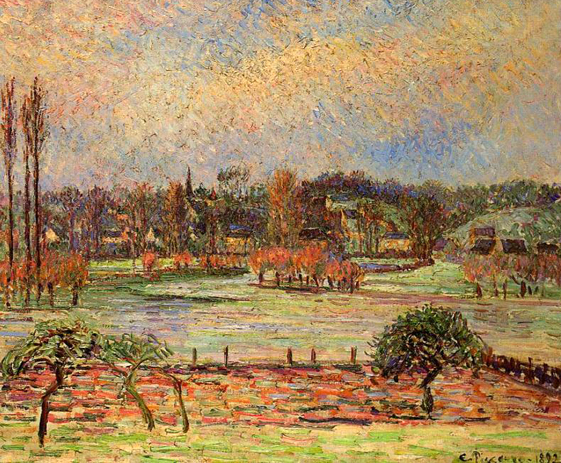

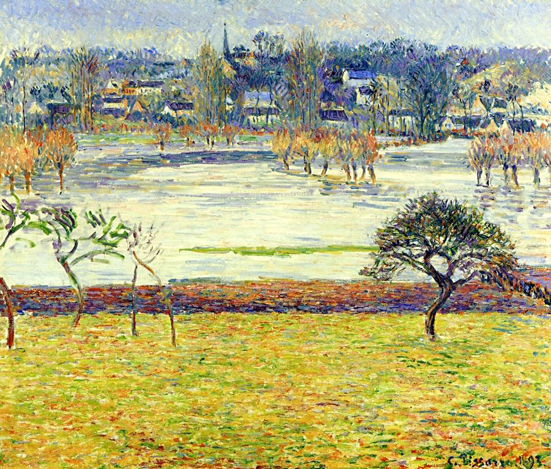

Flood in Pontoise: 1882

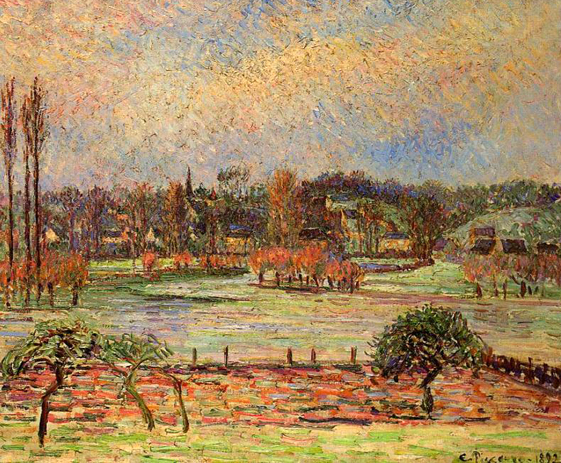

Flood Morning Effect, Eragny: 1892

Flood Twilight Effect, Eragny: 1893

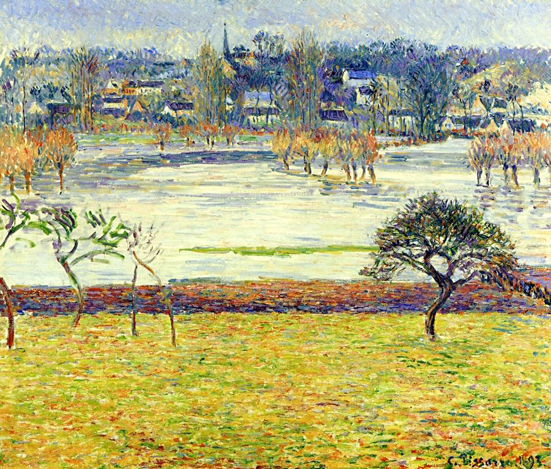

Flood White Effect, Eragny: 1893

Flowering Apple Trees at Eragny: 1888

Flowering Plum Trees: ca 1890

Fog in Eragny: 1890-99

Fog Morning, Rouen: 1896

Foggy Morning Rouen: 1896

Frost View fom Bazincourt: 1891

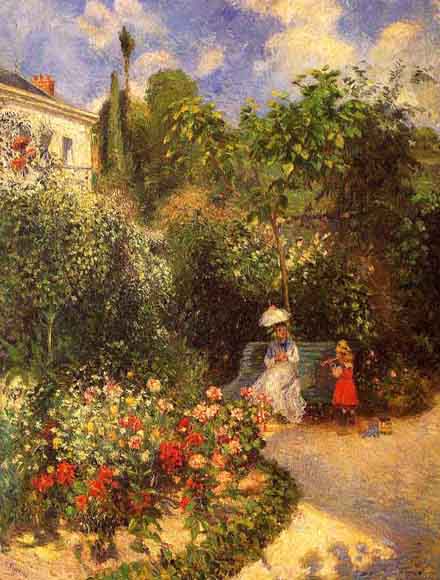

Garden at Eragny: 1899

Garden at Eragny (Study): 1899-1900

_1899_1900.jpg)

Garden of Les Mathurins: 1876

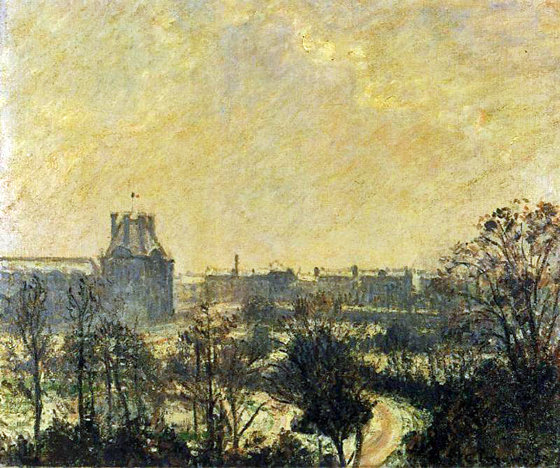

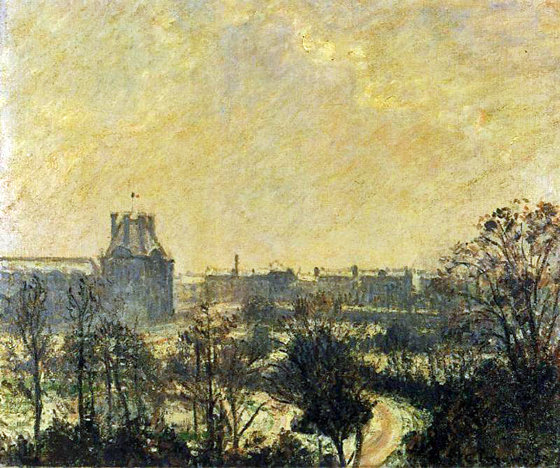

Garden of the Louvre - Fog Effect: 1899

Garden of the Louvre - Morning Grey Weather: 1899

Garden of the Louvre - Snow Effect: 1899

Gathering Herbs: 1882

Girl Sewing: 1895

Girl Tending a Cow in a Pasture: 1874

Gizors New Section: ca 1885

Goose Girl: 1890

Grey Day Banks of the Oise: 1878

Grey Weather Morning with Figures, Egagny: 1899

Groves of Chestnut Trees at Louveciennes: 1872

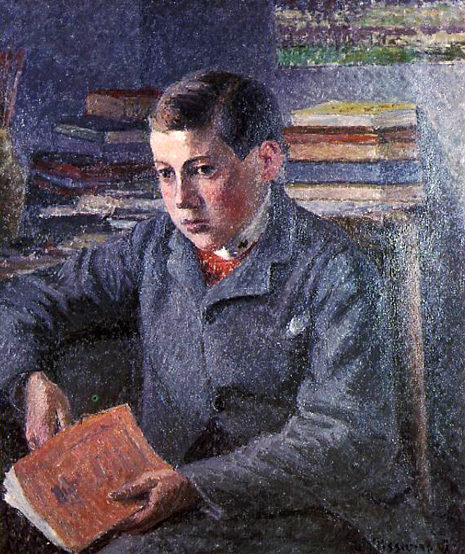

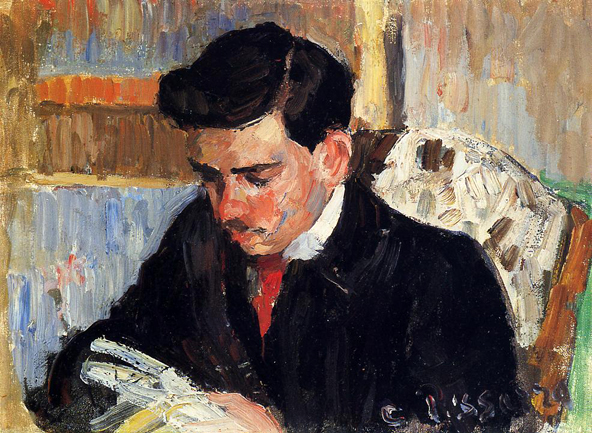

Half Length Portrait of Lucien Pissarro: ca 1875

Hampton Court Green: 1890

Hampton Court Green, London: 1891

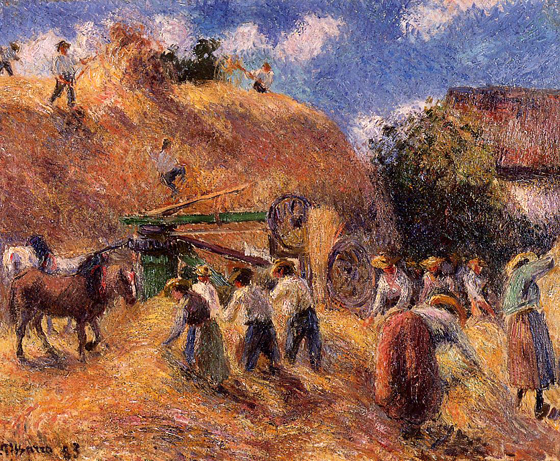

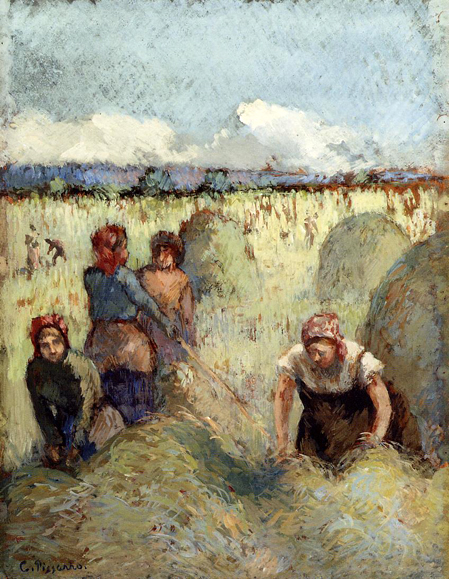

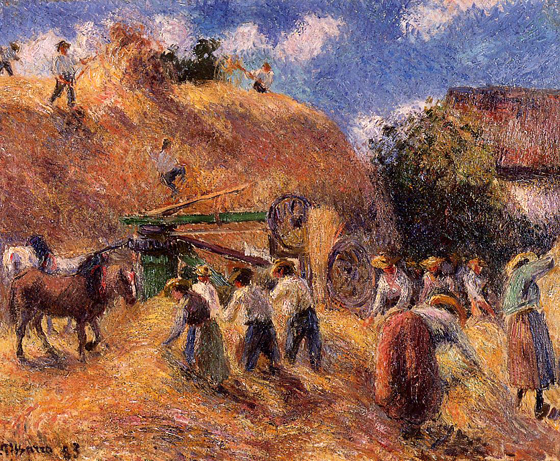

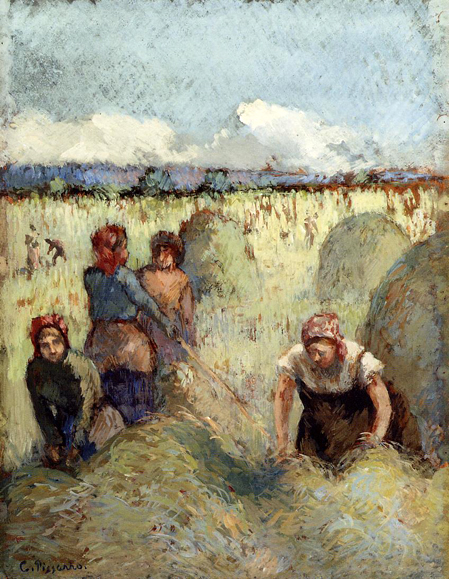

Harvest: 1883

Harvest at Eragny: 1901

Harvesting the Orchard, Eragny: ca 1899

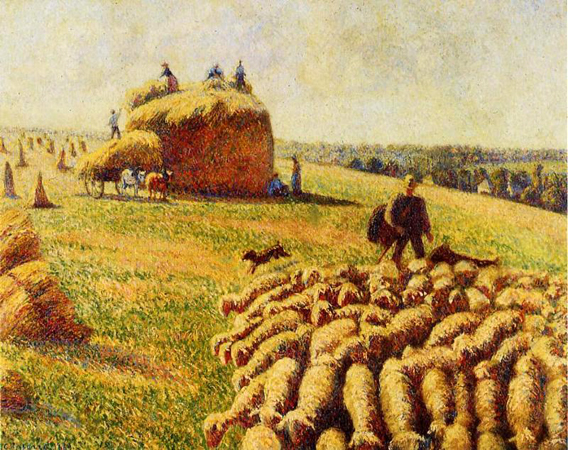

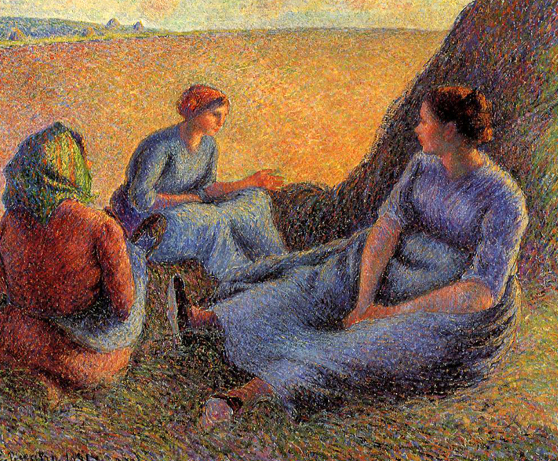

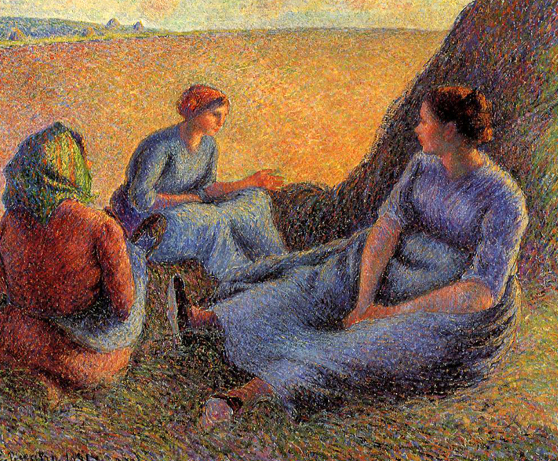

Haymakers at Eragny: 1889

Haymakers at Rest: 1891

Haymaking at Eragny: 1891

Haymaking: ca 1895

Haymaking in Eragny: 1901

Homes near the Osny: 1872

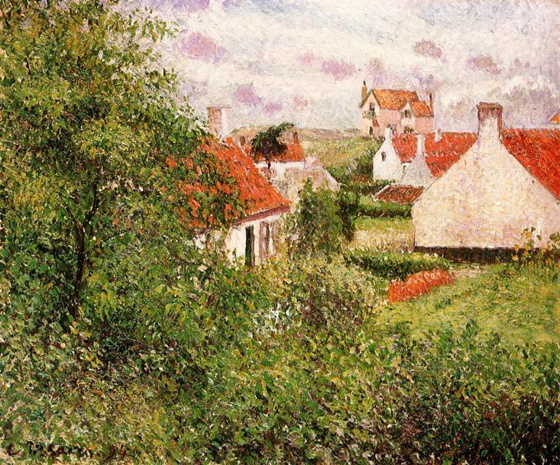

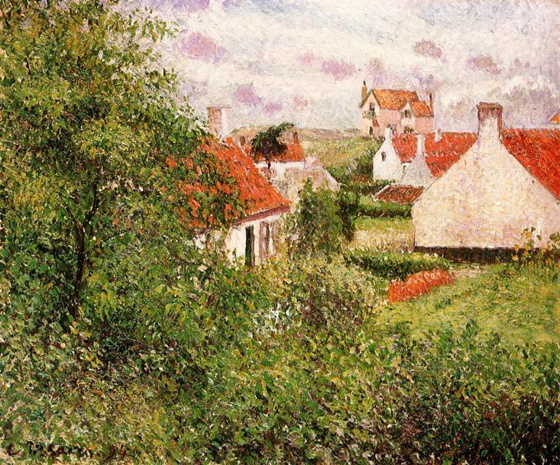

Houses at Knocke, Belgium: 1894

Houses of l'Hermitage, Pontoise: 1879

In the Woods: 1864

Jeanne Cousant: 1900

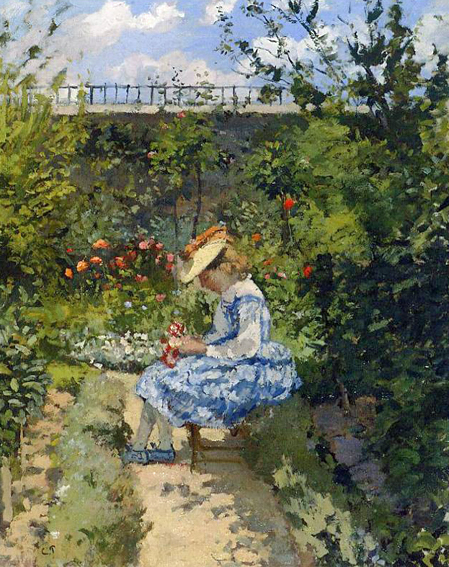

Jeanne in the Garden, Pontoise: 1872

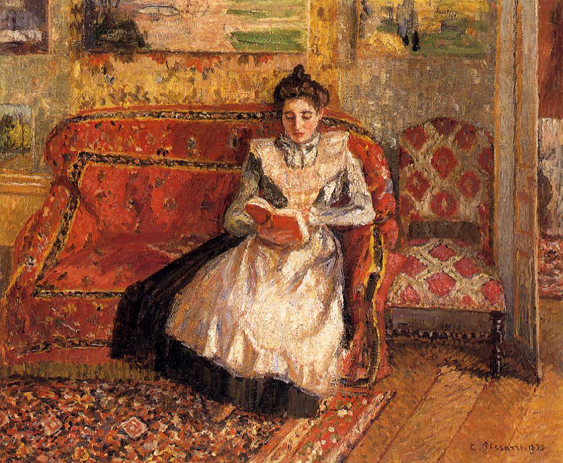

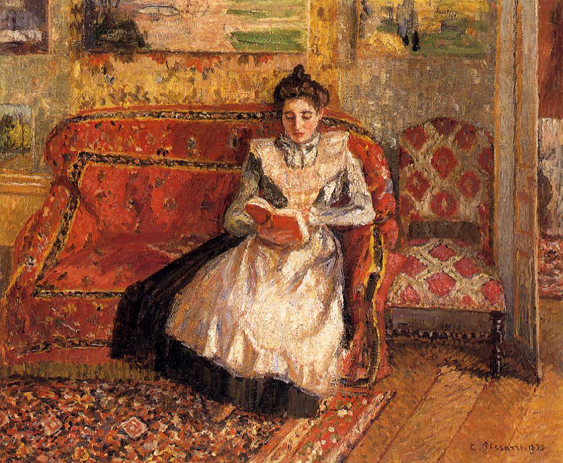

Jeanne Reading: 1899

Kensington Gardens, London: 1890

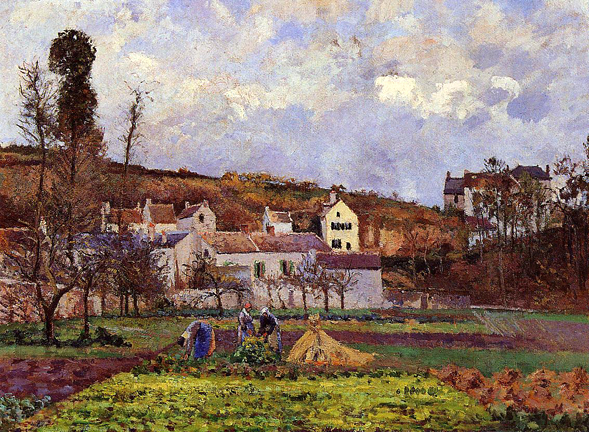

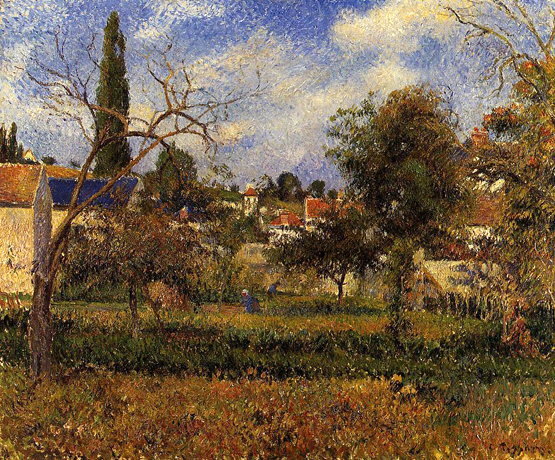

Kitchen Gardens at l'Hermitage, Pontoise: 1873

Kitchen Gardens, Pontoise: 1881

La Cote du Jallais, Pontoise: 1875

La Mere Gaspard: 1876

La Valhermeil near Pontoise: 1880

Landscape at Varengeville: 1899

Landscape Varenne Saint Hilaire: 1864-65

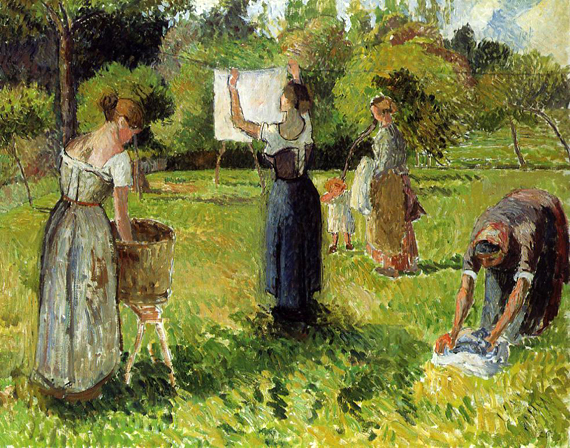

Laundresses at Eragny: 1901

Le Chou a Pontoise

(aka La Moussiere): 1882

_1882.jpg)

Le Parc aux Charrettes Pontoise: 1878

Le Pont Neuf: 1901

The Pont Neuf (French for "New Bridge") is the oldest standing bridge across the river Seine in Paris. Its name, which was given to distinguish it from older bridges that were lined on both sides with houses, has remained.

Standing by the western point of the Île de la Cité, the island in the middle of the river that was the heart of medieval Paris, it connects the Rive Gauche of Paris with the Rive Droite.

The bridge is composed of two separate spans, one of five arches joining the left bank to the Île de la Cité, another of seven joining the island to the right bank. Old engraved maps of Paris show how, when the bridge was built, it just grazed the downstream tip of the Île de la Cité; since then, the natural sandbar building of a mid-river island, aided by stone-faced embankments called quais, has extended the island. Today the island is the Square du Vert-Galant, a park named in honor of Henry IV, nicknamed the "Green Gallant."

Louveciennes the Road to Versailles: 1870

Lucien Pissarro in an Interior: ca 1875

March Sun, Pontoise: 1875

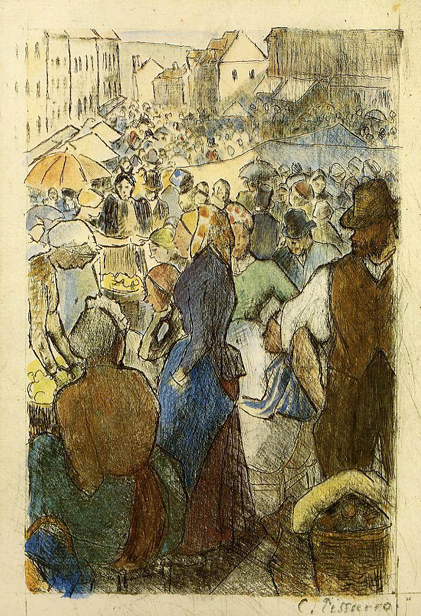

Market at Gisors Rue Cappeville: 1904-05

Market at Pontoise: 1895

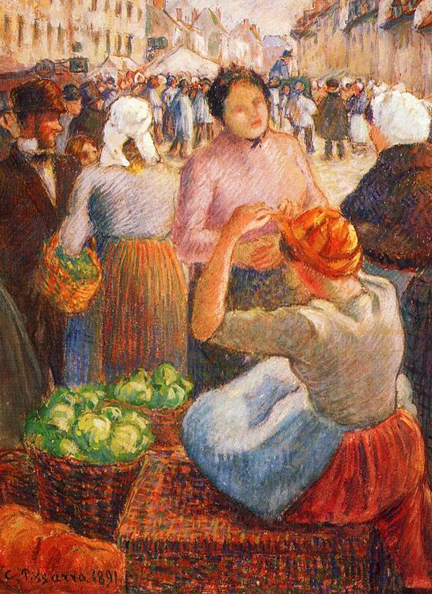

Marketplace, Gisors: 1891

Meadow at Bazincourt: 1885

Meadows at Eragny: 1886

Mirbeau's Garden the Terrace: ca 1892

Morning Overcast Day, Rouen: 1896

Morning Rouen the Quays: 1896

Morning Sun Effect, Eragny: 1899

Mother Jolly: 1874

Mother Lucien's Field at Eragny: 1898

Near Pontoise: ca 1877-79

Near Sydenham Hill Looking towards Lower Norwood: 1871

Neaufles Sant Martin near Gisors: 1885

Old Houses at Eragny: ca 1885

Old Wingrower in Moret

(aka Interior): 1902

_1902.jpg)

On Orchard in Pontoise in Winter: 1877

Orchards at Louveciennes: 1872

Path of l'Hermitage at Pontoise: 1872

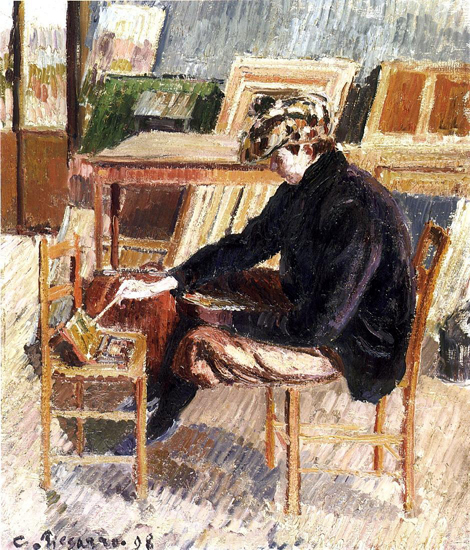

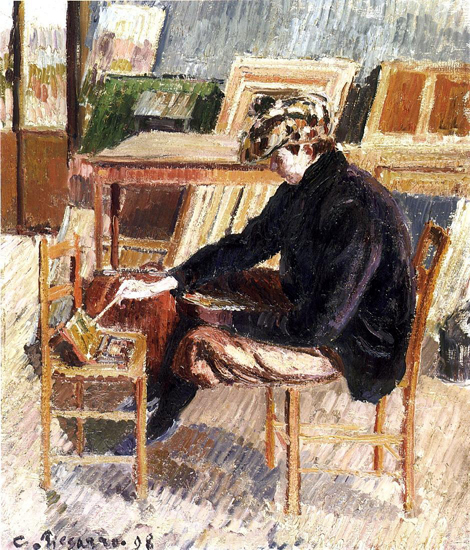

Paul Painting (Study): 1898

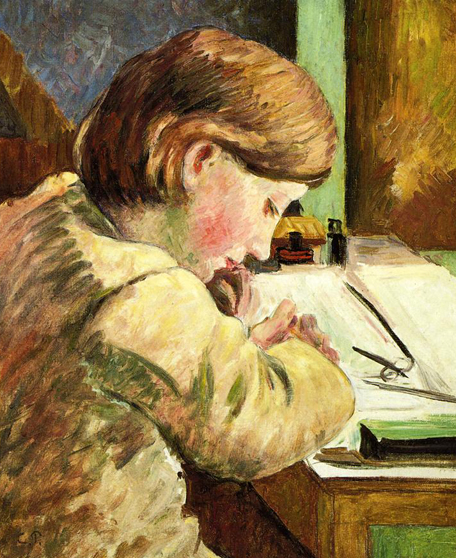

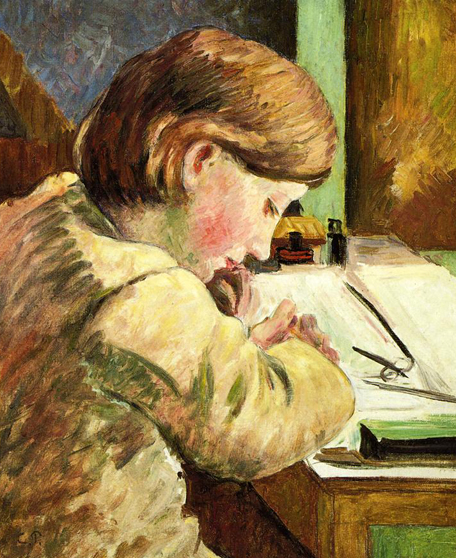

Paul Writing: ca 1894

Paul-Emile Pissarro: 1890

Paysage a Osny pres de l'abreuvoir: 1883

Pear Tress in Bloom Eragny Morning: 1886

Peasant Crossing a Stream: ca 1894

Peasant Woman and Child, Eragny: 1893

Peasant Woman Warming Herself: 1883

Peasant Women Planting Stakes: 1891

Peasants Chatting in the Farmyard, Eragny: 1895-1902

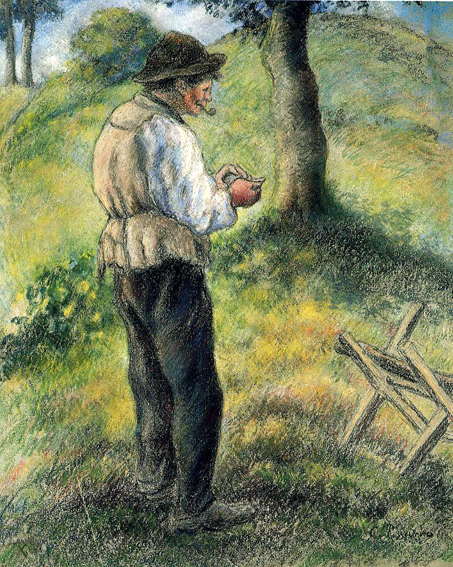

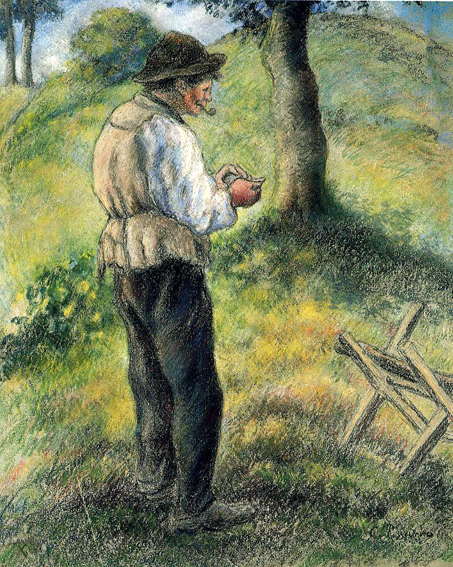

Pere-Melon Lighting His Pipe: ca 1879-80

Place du Carrousel, the Tuileries Gardens: 1900

In the winter of 1898, Pissarro decided to rent an apartment in Paris rather than to take hotel rooms, as he had done during his previous visits to the capital. In a letter to his son Lucien dated 4th December 1898, Pissarro wrote: 'We have engaged an apartment at 204 rue de Rivoli, facing the Tuileries, with a superb view of the Garden, the Louvre to the left, in the background the houses on the quais behind the trees, to the right the Dôme des Invalides, the steeples of Ste. Clothilde behind the solid mass of chestnut trees. It is very beautiful. I shall paint a fine series'. Due to adverse weather in the winter months of 1898-99 the artist was making a slow progress, but in a letter of 12th April 1899 he reported to have done much work on his Tuileries series. On 23rd May he wrote: 'I sent Durand-Ruel eleven of my Tuileries canvases, I am keeping three of them'. Among the eleven works mentioned in the letter is the present painting Le Carrousel, matin d'automne. During the first half of 1900 Pissarro executed a second series of the Jardin des Tuileries, painted from the same viewpoint.

Being settled in an apartment, rather than frequently moving between short-term accommodations, allowed Pissarro to spend more time working on a particular series of paintings, and to meditate and experiment with the subject matter. This resulted in a great variation within the series, as the artist was able to observe and depict his subject in different weather conditions, and in different seasons and times of the day. Moving from one window to the next, the artist captured the urban landscape in front of him from three slightly different vantage points, thus creating three distinctive views within the Tuileries series: a frontal viewpoint showing the Bassins des Tuileries a view of the Louvre's Pavillon de Flore and the southern wing, Aile Denon, and, moving eastwards, a view of the Pavillon de Marsan to the left, with Jardin du Carrousel in the centre and the Aile Denon in the background, as in the present work.

Having completed a series of the Boulevard Montmartre, with its wide spaces pulsating with horse-drawn carriages, pedestrians and other signs of the busy life of the metropolis, in the Tuileries series Pissarro took pleasure in painting the calmer, greener parts of Paris, in depicting nature within the city. This series, representing bastions of art and tradition such as the Louvre, stand in contrast to Pissarro's paintings of the new areas of Paris, recently transformed and modernized by the popular boulevards designed by Baron Hausmann. The Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel, visible in the middle distance of the present work, was built in the first decade of the nineteenth century, to commemorate the Napoleonic victories of 1805. Based on the Arch of Septimius Severus in Rome, it stands as a romantic symbol of the French empire and its grandeur. With its fascinating architecture and history, the Jardin des Tuileries captured the imagination of other Impressionist artists, including Claude Monet who, in 1876, depicted a view from the apartment only a few doors away from that occupied by Pissarro, at 198 rue de Rivoli.

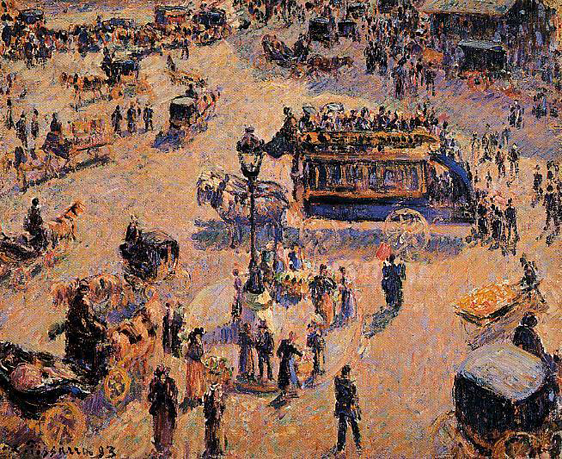

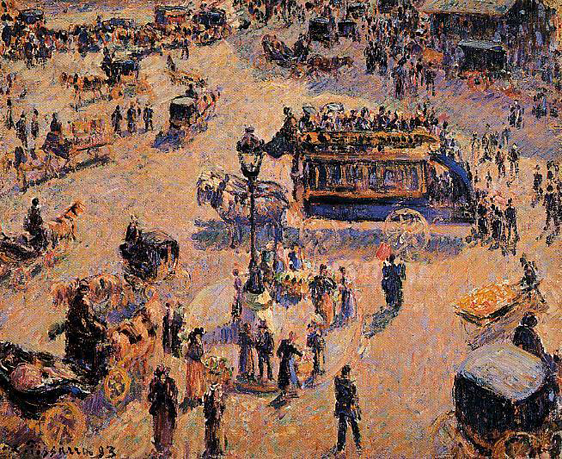

Place du Havre, Paris: 1893

In the 1890's, after experimenting briefly with the Neo-Impressionist style developed by Georges Seurat, Camille Pissarro returned to the more gestural surface treatment associated with Impressionism. The 'Place du Havre, Paris' is one of four canvases the artist painted in February 1893 from his room at the Hôtel Garnier, overlooking the rue St. Lazare, during a temporary stay in Paris. Like several of his fellow Impressionists, most notably Gustave Caillebotte and Claude Monet, Pissarro-the great painter of rural life-found himself drawn to the teeming activity of the capital's boulevards. Retaining the bright, primary hues of Neo-Impressionism for his representations of frenetic urban bustle, he applied them in an array of flickering, multidirectional brush strokes, an approach that epitomizes the Impressionist painting technique.

During this period, Pissarro began working in series, a practice initiated by Monet several years earlier and exemplified in his famous 'Stacks of Wheat'. Pissarro typically began such canvases on site, recording significant atmospheric effects, and then finished them in his studio. He depicted Paris several times throughout his career, rendering metropolitan activity in a full range of seasons and weather conditions, much as he had done for more rustic settings. The 'Place du Havre' is among the largest of the Paris compositions, all of which feature a high vantage point. Pissarro wrote of this series in 1898: "Perhaps it is not really aesthetic, but I am delighted to be able to try to do these Paris streets which people usually call ugly, but which are so silvery, so luminous, and so vital. . . . This is so completely modern."

Place du Theatre Francais, Afternoon Sun in Winter: 1898

Place Saint-Lazare: 1893

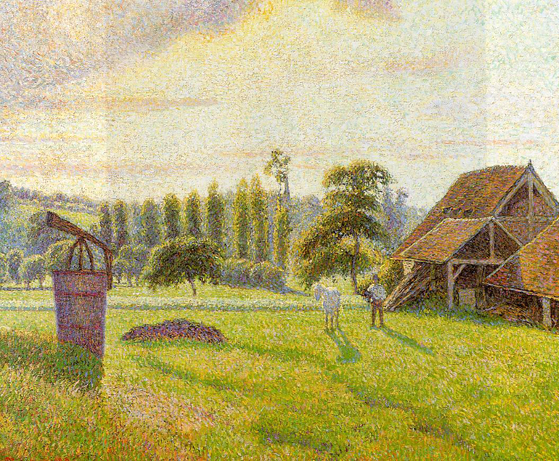

Anarchist-Communism

The nondescript peasant of Camille Pissarro's Hoarfrost (1873) hunches over, gathering firewood in an endless landscape. As an example of Pissarro's rural imagery, the golden fields seem to swallow him up as he traverses alone through the calm, peaceful scenery. The anarchist intellectual Octave Mirbeau declared that in Pissarro's depictions of rural life, "man is always in perspective in a vast telluric harmony". The anarchist vision of man in harmony with nature appears again and again in Pissarro's paintings with his attention to rural themes. Agrarian subjects, peasants in particular, represented the healthy life of people free from confining economic and institutionalized patterns. An anarchist himself, Pissarro believed in a peaceful society based on rural communities without the oppressive bourgeoisie. Pissarro painted rural images for the majority of his life, choosing to focus on idealized, idyllic scenes without machinery.

Pissarro belonged to a movement now termed, 'anarchist-communism' that incorporated beliefs from economic communism and individual anarchism. Besides being friends with Mirbeau, Pissarro also gave substantial financial assistance to Jean Grave, the dominant figure in the French anarchist-communist movement. These anarchists thought that man worked best in small groups, with communal, rather than national, collective ownership. In Pissarro: His Life and Work, Ralph Shikes explains that "anarchism was opposed to all authoritative institutions that curbed man's freedom - the state (especially), the church, private property, even, some anarchists believed, the family". Critics isolate Pissarro's anarchism to his earlier rural works, linking his idealized, idyllic scenes without machinery to his belief in a peaceful society founded on rural communities. This easy connection between anarchism and rural imagery satisfies most art historians, but limits any political expression to only a part of Pissarro's paintings; during the last eight years of his life, Pissarro departed from his rural topics and painted eleven series set in Paris, Rouen, Le Havre, and Dieppe. However, Pissarro's anarchist views extended far beyond the timeframe of his rural period. This affinity for the anarchists is perhaps most evident in his stance during the Dreyfus Affair, when he sided with the Dreyfusards against the Army and Church, institutions he regarded as corrupt.

Pont Neuf - Fog: 1902

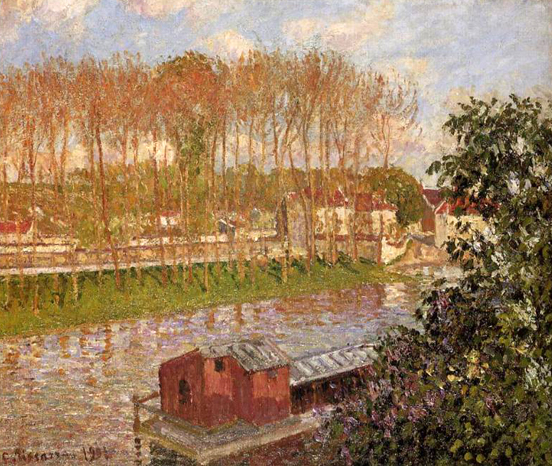

Pontoise Dam: 1872

Pontoise Les Mathurins: 1873

Pontoise the Road to Gisors in Winter: 1873

Pont Neuf the Statue of Henri IV, Sunny Weather Morning: 1900

Poplars Afternoon in Eragny: 1899

Portal from the Abbey Church of Saint-Laurent: 1901

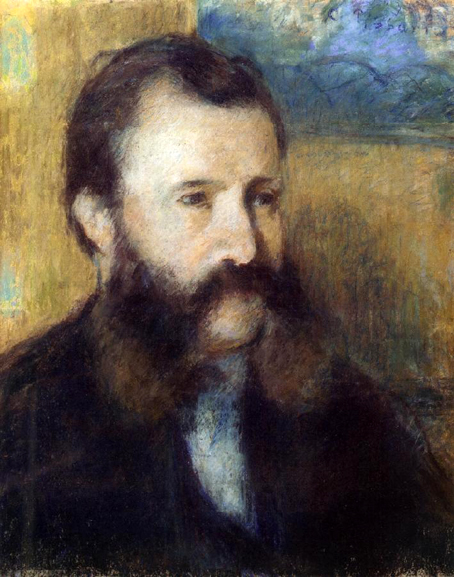

Portrait of Eugene Murer: 1878

Portrait of Eugenie Estruc: 1876

Eugénie Estruc, called Nini by her family, was the daughter of Louis and Felicie Estruc, and niece of the artist.

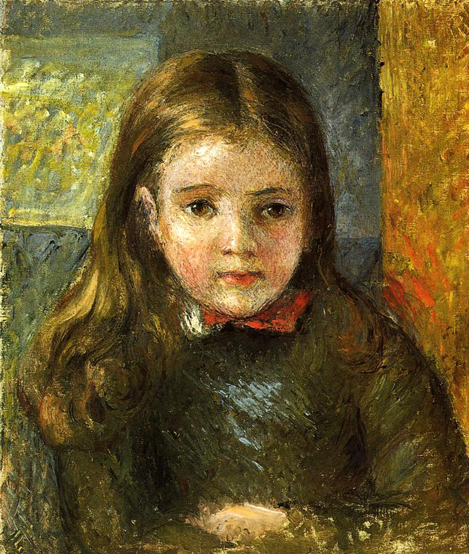

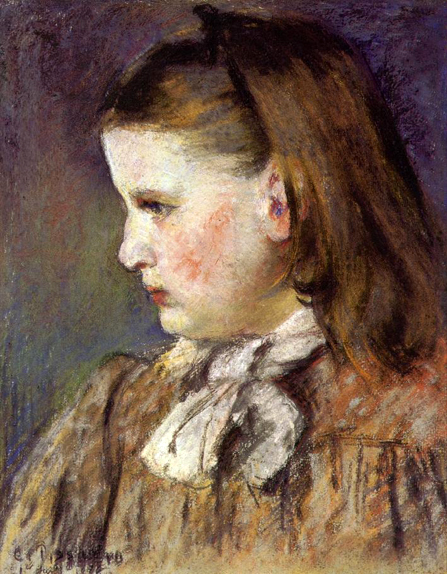

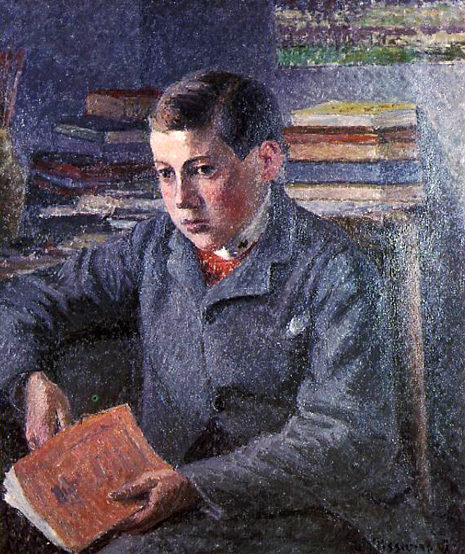

Portrait of Felix Pissarro: 1881

Félix-Camille (1874 - 1897), also known as Titi, was the third son of Camille and Julie Pissarro. This portrait, showing him at the age of seven, is one of several paintings and drawings of him by his father.

Before his premature death in London in 1897, Félix worked as a painter, engraver and caricaturist under the pseudonym Jean Roch.

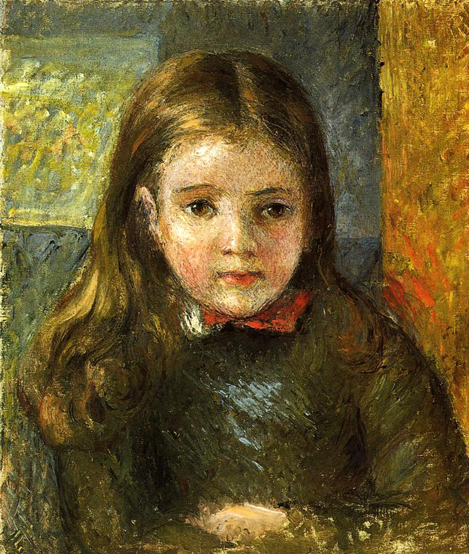

Portrait of Georges: 1881

He was survived by one daugher, Jeanne Pissarro, and through her a generation of other artists would be born. Lelia Pissarro, Henri Bonin-Pissarro (also known as BOPI) and Claude Bonin-Pissarro.

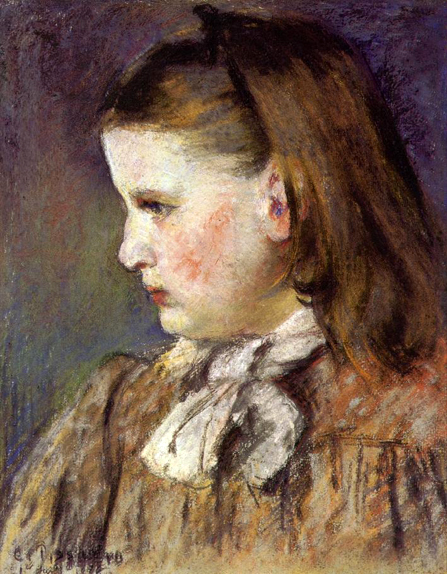

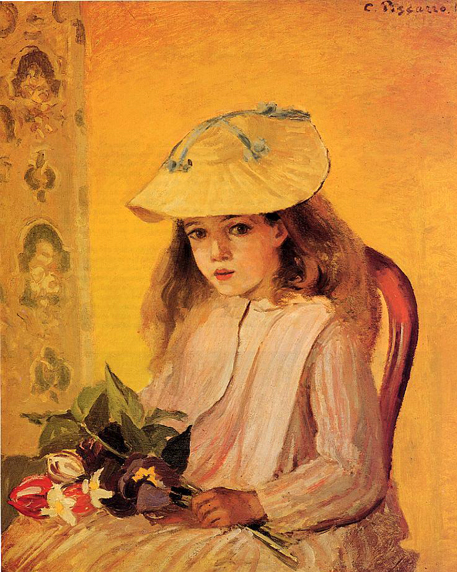

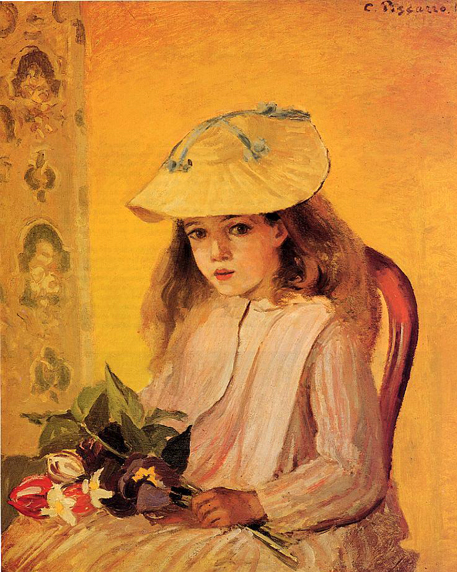

Portrait of Jeanne: 1872

Portrait of Jeanne: 1892

Portrait of Jeanne: ca 1898

Portrait of Jeanne in a Pink Robe: ca 1897

Portrait of Jeanne, the Artist's Daughter

Portrait of Jeanne with a Fan: ca 1873

Portrait of Jeanne-Rachel (Minette): 1872

("Minette" was the nickname of Pissarro's daughter, Jeanne-Rachel.)

_1872.jpg)

Portrait of Madame Felicie Vellay Estruc: ca 1874

Executed circa 1874, this portrait shows the sister-in-law of Camille Pissarro, executed in the year of the first Impressionist exhibition in Paris.

Portrait of Madame Pissarro: 1883

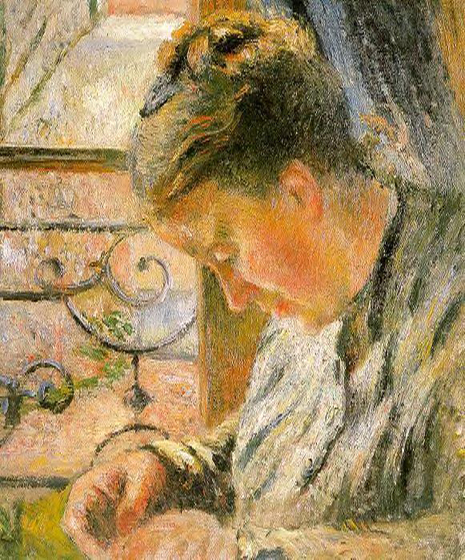

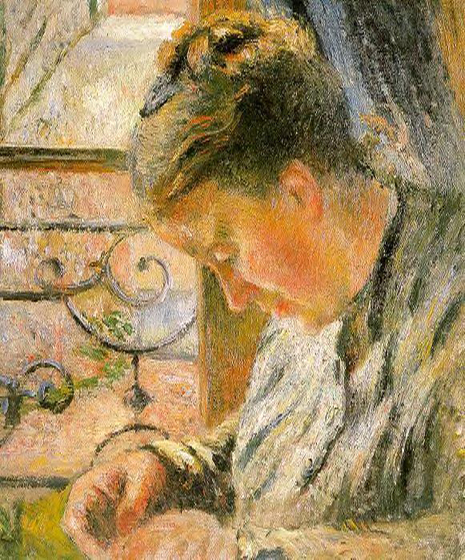

Portrait of Madame Pissarro Sewing near a Window: 1878-79

Portrait of Monsieur Louis Estruc: ca 1874

Portrait of Nini: 1884

'Portrait de Nini' is an extremely rare work, both because of its somber yet brilliant colors; and the importance of the sitter to Pissarro. Also because Pissarro painted relatively few portraits. In depth of feeling and quality of painting, it ranks with his finest portraits.

Eugenie Estruc (1863-1931) known affectionately as 'Nini' in the Pissarro family, was the niece of Pissarro's wife Julie who had been a maid to Pissarro's mother. Like her aunt, Nini was Christian and of peasant stock. Pissarro drew, painted, and etched Nini.

On the 22nd July 1883, Pissarro writes to his eldest son Lucien, 'I had Nini pose as a butcher's girl at the Place du Grand Martoy; the painting will have, I hope a certain naive freshness'.

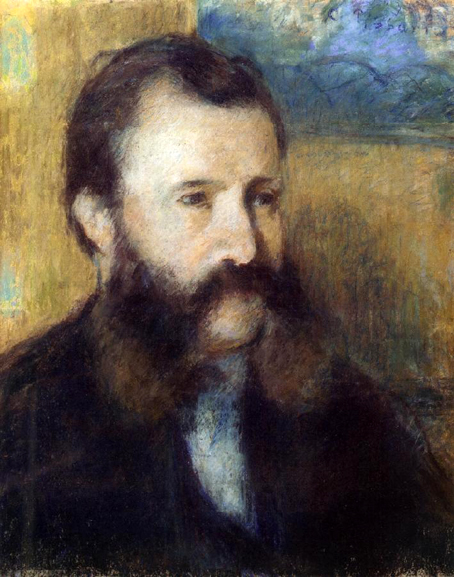

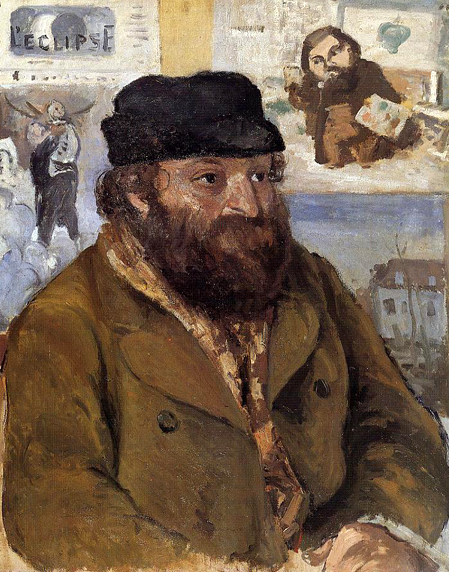

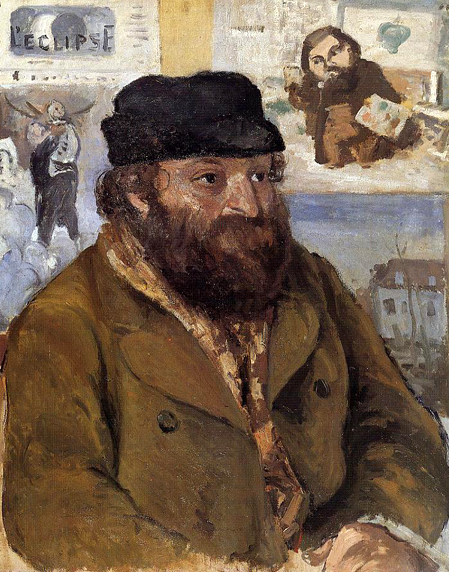

Portrait of Paul Cezanne: 1874

Pissarro's influence profoundly changed the direction of Cézanne's art as they worked together at Pontoise in the early 1870's. In this portrait of Cézanne, a painting by Pissarro hangs at the lower right. Two political prints show the statesman Adolphe Thiers on the left and the painter Courbet on the right, famous men of the day who both seem to acknowledge Cézanne. The portrait is a tutor's affectionate testament of support and friendship for a brilliant protégé, and a humorous prediction that fame and glory would one day be his.

The portrait hung in Pissarro's studio until his death in 1903.

Portrait of Paulemile: ca 1894

Portrait of Paulemile: ca 1899

Paulemile Pissarro

Of all Camille Pissarro's sons, Paulemile may have been the most naturally talented. Among his father's papers (found after he died), was a very precocious drawing of a white horse done when the boy was five. The drawing had been much praised by the French writer Mirbeau. Paulemile entered college at the age of fifteen but left after a short time to study and travel with his father. And, unlike his brothers, Paulemile's art education was not limited to just that of his father's tutelage. He attended a private art academy in Paris during the winter months when his by now modestly well-off parents lived in the city. Paulemile was just nineteen when his father died in 1903.

After his father's death, Paulemile moved with his mother to their summer home near Eragny. Eragny was a mere 30 km from Giverny, the home of his father's closest friend, Claude Monet. And, as he grew older, it was to Monet that Paulemile gravitated, adopting him both as a father figure, teacher, and friend. And it was Monet, as much or more than his father, who was to influence his art as the youngest Pissarro yearned to follow in his father's footsteps. Paulemile exhibited for the first time in the 1905 Salon des Independants. The entry was an Impressionist landscape entitled Bords de l'Epte a Eragny. But, like most young artists, despite his family name and in his case, no pleas from his father not to use it, Paulemile struggled. It was a struggle his mother recognized all too well, and a life she hated. It was not one she wished to pass on to her son. She encouraged him to give up his art. For a time, Paulemile worked as an auto mechanic and test driver, later as a lace and textile designer. His work allowed him virtually no time to paint.

It was his oldest brother, Lucien, who rescued him. He wrote from London and asked Paulemile to send him some early watercolors. Perhaps because of the Pissarro name, the work quickly sold to British collectors. Paulemile quit the lace factory, married, and spent the W.W. I years painting in the north of France (illness kept from military service) and selling his work through his brother in London. The individuality and confidence he acquired during this time, along with the teachings of Monet and the strong influence of Cézanne in his work, made him immensely popular, especially in England. His older brother shepherded his career, gaining him entrance into the New English Art Club, The Allied Artists' Association, and the Baillie Gallery, where his work sold steadily. In France, along with his close friends van Gongen, Vlaminck, de Segonzac, and Raoul Dufy, he became one of the stars of Postimpressionism. He adopted the palette knife over the brush as his preferred painting tool and, more than his father's or even Monet's work, his own painting began to resemble more closely that of Cézanne.

The 1920's and 1930's were to be the strongest period in Paulemile Pissarro's painting career. In 1930 he divorced his first wife and married a second. They purchased a home near Clecy on the Orne River in the area of hills and valleys known as Swiss Normandy. There they raised three children - two sons and a daughter. His oldest son, Hugues-Claude also became a painter. In 1967, Paulemile Pissarro had his first one-man show in the United States at the Wally Findlay Galleries in New York, which led to wide recognition and success in this country, far in excess of that of his brothers, or even his father during his lifetime. The last of the first-generation Pissarros, Paulemile died in 1972, and today his work often rivals his father's in popularity with collectors and museums. In all this, one has to wonder how much of his success can be attributed to being the "baby" in the family.

Portrait of Pere Papeille Pontoise: ca 1874

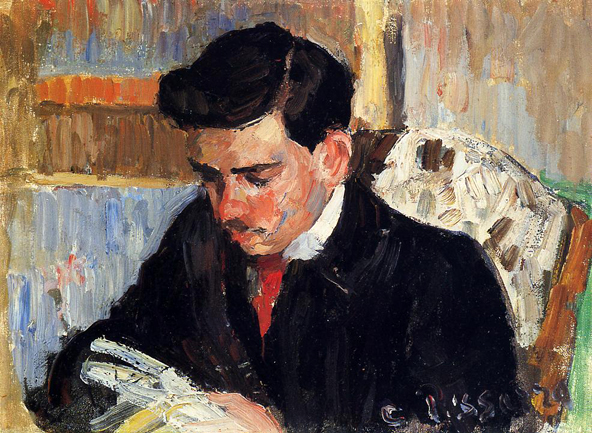

Portrait of Rodo Pissarro Reading: 1899-1900

Ludovic-Rodolphe would like to have been remembered as a great painter too. Instead, he's most recalled today as an art historian, responsible for cataloguing the life's work of his father, Camille Pissarro. The two volume work, published in 1939, took him some twenty years to compile and has become the standard to which all other art historians turn in studying his father's work. Yet this fourth son of Camille and Julie Pissarro was by turns also an Impressionist, a wood engraver, a Fauvist, a practitioner of the decorative arts, and a political activist (allying himself with French anarchists as a young man). By rights, Ludovic-Rodolphe Pissarro should have been a famous painter. He had all the right breaks. Like his brothers, he had perhaps the best art teacher in the world at the time. His kindly father has long been revered for his warmth and effective influence upon several young artists seeking his steady hand and critical eye. And he knew all the right people. A great number of famous and soon-to-be-famous artists of his time vied for a seat at Camille Pissarro's table. And though he was first and foremost a student of his father, Rodo picked up much from them - artists as diverse as Maurice Vlaminck, Raoul Dufy, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

Born in 1878, Ludovic-Rodolphe Pissarro, it could be argued, may have had too many influences. Unlike his older brother, Lucien, Rodo never seemed to settle into a single groove (or rut, depending upon one's view) but instead, found himself constantly turning to new things, often before completely mastering any of them. Of all his father's sons, Rodo was closest to him, the only one to be with him at his death in 1903. After that, Rodo followed Lucien to London where they shared studio space and despite his family's position in the art world, he struggled as an artist. In Paris, he displayed at the 1905 Salon des Indépendants as a Fauvist, though in all likelihood he was not enough of a Fauvist to gain much notice. In London, several times he was rejected by the New English Art Club. His paintings of London street life rendered through windows several floors up are fascinating, if hardly remarkable. In 1915, with the help of his brother and a few friends, he started their own club, calling it the Monarro Group, formed specifically as an alternative means of gaining public recognition for their work. Perhaps too, Ludovic-Rodo struggled because, like all his brothers, except for Lucien, he was encouraged by his father not to trade upon the Pissarro name.

Though Rodo could hardly be considered a failure as an artist, his star was perhaps the least lustrous of all the Pissarro offspring. And though he was unable to polish his own work and image as an artist, his long, diligent, scholarly effort in pulling together his father's vast exploration of various forms of artistic expression has added immeasurably to the understanding and luster of Camille Pissarro's oeuvre and indirectly, to that of the entire family. Ludovic-Rodo died in 1952 having acquiesced to the fact that he was a Pissarro in name only, and hardly that. Yet ironically, his literary contribution to the art world may well be remembered long after the paintings of his more talented siblings have long been forgotten.

Potato Harvest: 1893

Potato Market, Boulevard des Fosses, Pontoise: 1882

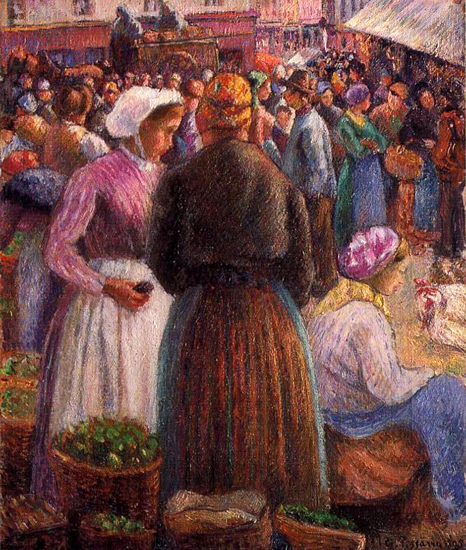

Poultry Market at Gisors: 1889

Poultry Market, Pontoise: 1892

Quai Malaquais in the Afternoon Sunshine: 1903

Quai Malaquais Morning Sunny Weather: 1903

Rainbow, Pontoise: 1877

Red Roofs Corner of a Village Winter

(aka Cote de Saint Denis at Pontoise): 1877

_1877.jpg)

Riverbanks in Pontoise: 1872

Rue de l'Eppicerie, Rouen Morning Grey Weather: 1898

Rue de l'Hermitage Pontoise: 1874

Rue Saint Honore, Sun Effect - Afternoon: 1898

Saint Martin near Gisors: 1885

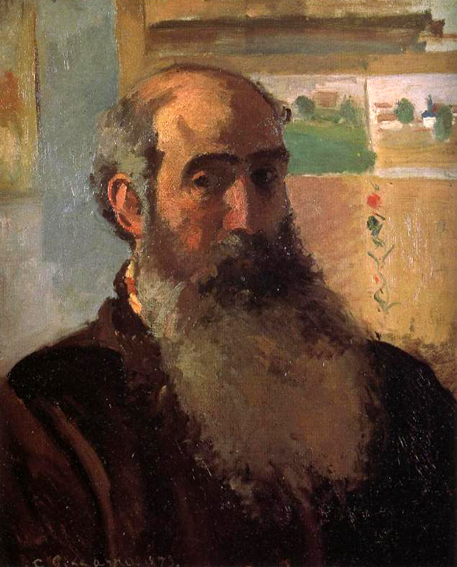

Self Portrait: 1873

Self Portrait: 1903

September Celebration, Pontoise: 1872

Setting Sun at Moret: 1901

Sunlight Afternoon La Rue de l'Epicerie, Rouen: 1898

Sunset, Rouen: 1898

The Artist's Garden at Eragny: 1898

The Avenue Sydenham: 1871

The Banks of the Marne: 1864

The Baths of Samaritaine Afternoon: 1902

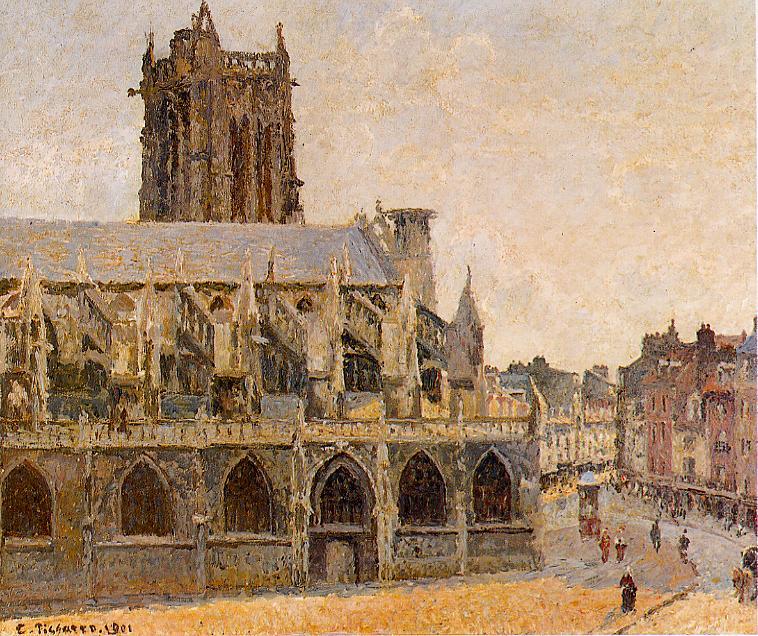

The Church of Saint Jacques, Dieppe: 1901

The Court House, Pontoise: 1873

The Effect of Snow - Sunset, Eragny: 1895

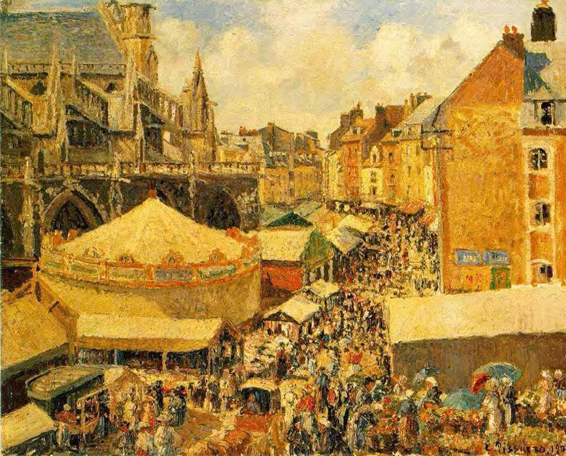

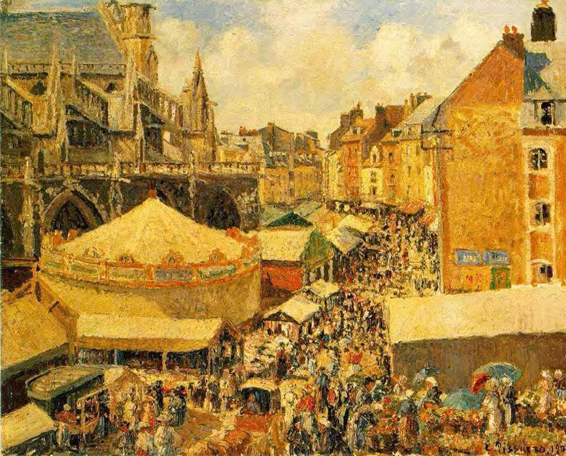

The Fair in Dieppe Sunny Morning: 1901

The Inner Harbor Le Havre: 1903

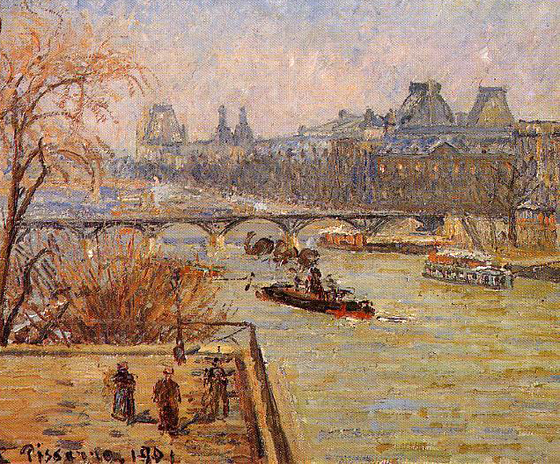

The Louvre: 1901

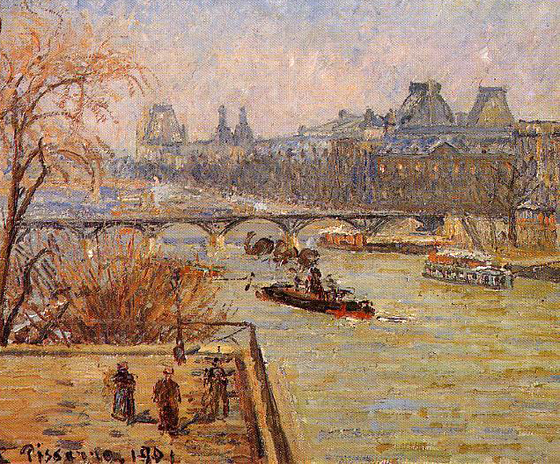

The Louvre and the Seine from the Pont Neuf: 1902

The Pavillion de Flore and the Pont Royal: 1902

Source: Art Renewal Center

Source: Camille Pissarro Online

Viatores

Viatores

This page is the work of Senex Magister

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.

_1880.jpg)

_1868.jpg)

_1876.jpg)

_1871_72.jpg)

_1897.jpg)

_1897.jpg)

_1897.jpg)

_ca_1869.jpg)

_1899_1900.jpg)

_1882.jpg)

_1902.jpg)

_1872.jpg)

_1877.jpg)