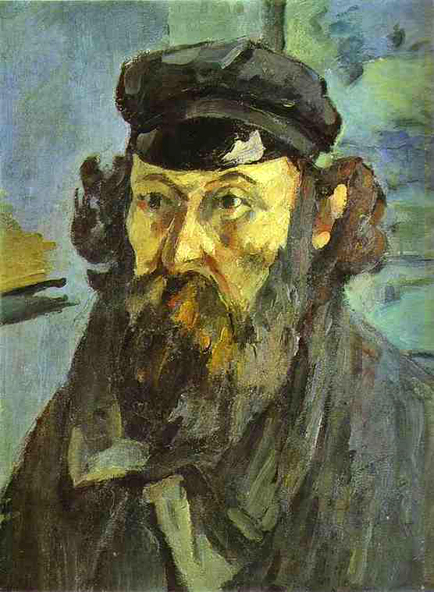

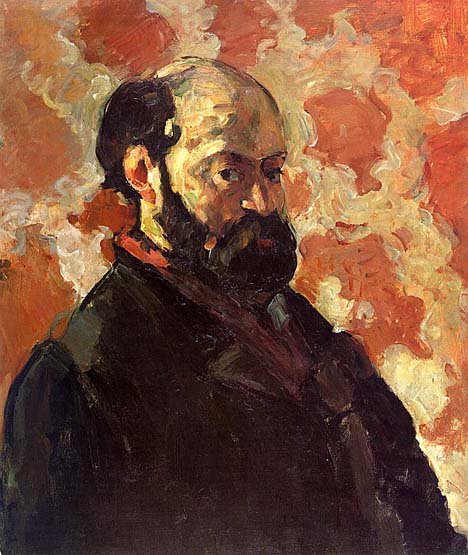

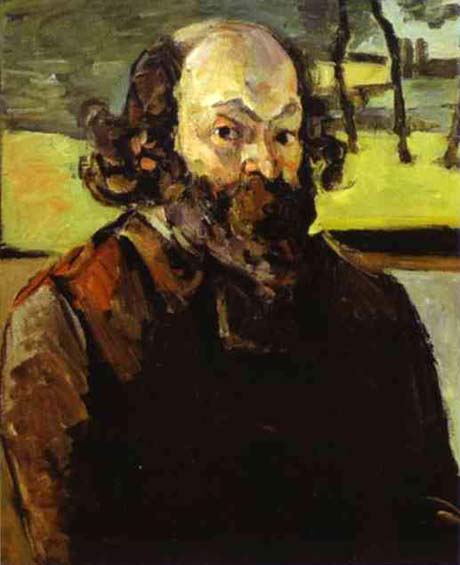

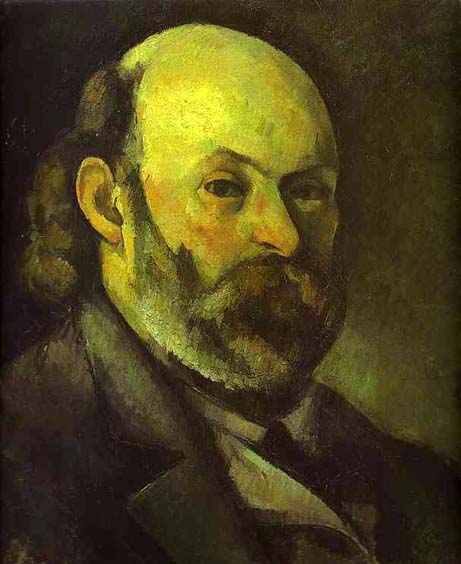

Post-Impressionist Painter

1839 - 1906

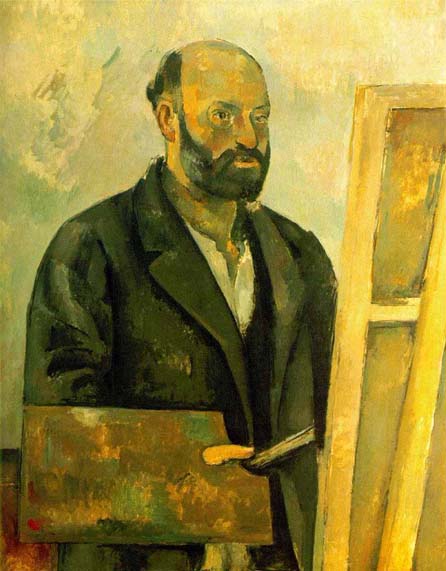

Paul Cezanne was a French artist and Post-Impressionist painter whose work laid the foundations of the transition from the 19th century conception of artistic endeavor to a new and radically different world of art in the 20th century. Cézanne can be said to form the bridge between late 19th century Impressionism and the early 20th century's new line of artistic enquiry, Cubism. The line attributed to both Matisse and Picasso that Cézanne "is the father of us all" cannot be easily dismissed.

Cezanne's work demonstrates a mastery of design, color, composition and draftsmanship. His often repetitive, sensitive and exploratory brushstrokes are highly characteristic and clearly recognizable. He used planes of color and small brushstrokes that build up to form complex fields; at once both a direct expression of the sensations of the observing eye and an abstraction from observed nature. The paintings convey Cézanne's intense study of his subjects, a searching gaze and a dogged struggle to deal with the complexity of human visual perception.

The Cezannes came from the small town of Cesana now in West Piedmont, and it has been assumed that they were ultimately of Italian origin. Paul Cezanne was born on 19 January 1839 in Aix-en-Provence, one of the southernmost regions of France. On 22 February, Paul was baptized in the parish church, with his grandmother and Uncle Louis as godparents. His father, Louis-Auguste Cezanne, was the cofounder of a banking firm that prospered throughout the artist's life, affording him financial security that was unavailable to most of his contemporaries and eventually resulting in a large inheritance. On the other hand, his mother, Anne-Elisabeth Honorine Aubert, was vivacious and romantic, but quick to take offense. It was from her that Paul got his conception and vision of life. He also had two younger sisters, Marie, with whom he went to a primary school every day, and Rose.

At the age of ten, Paul entered the Saint Joseph boarding-school, where he studied drawing under Joseph Gibert, a Spanish monk, in Aix. In 1852 Cezanne entered the Collège Bourbon (now College Mignet), where he met and became friends with Emile Zola, who was in a less advanced class. He stayed there for six years, though in the last two years he was a day scholar. From 1859 to 1861, complying with his father's wishes, Cezanne attended the law school of the University of Aix, while also receiving drawing lessons. Going against the objections of his banker father, he committed himself to pursuing his artistic development and left Aix for Paris in 1861.

He was strongly encouraged to make this decision by Zola, who was already living in the capital at the time. Eventually, his father reconciled with Crzanne and supported his choice of career. Cezanne later received an inheritance of 400,000 francs from his father, which rid him of all money fears.

In Paris, Cezanne met the Impressionists, including Camille Pissarro. Initially the friendship formed in the mid-1860's between Pissarro and Cezanne was that of master and mentored, with Pissarro exerting a formative influence on the younger artist. Over the course of the following decade their landscape painting excursions together, in Louveciennes and Pontoise, led to a collaborative working relationship between equals.

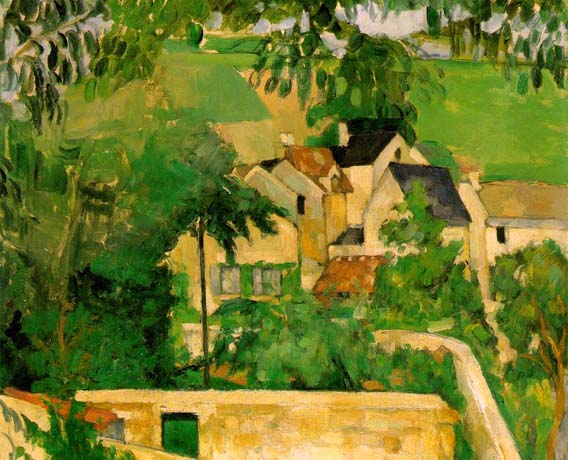

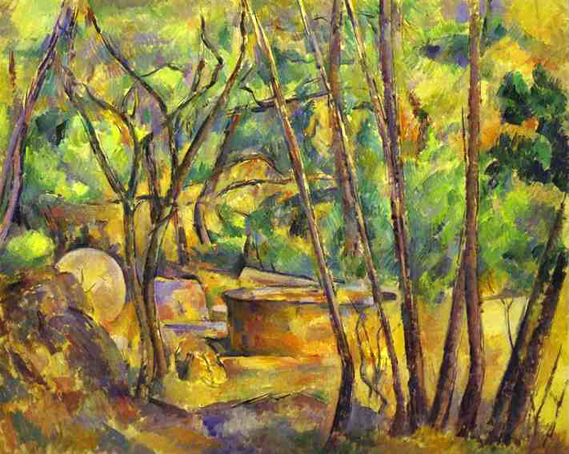

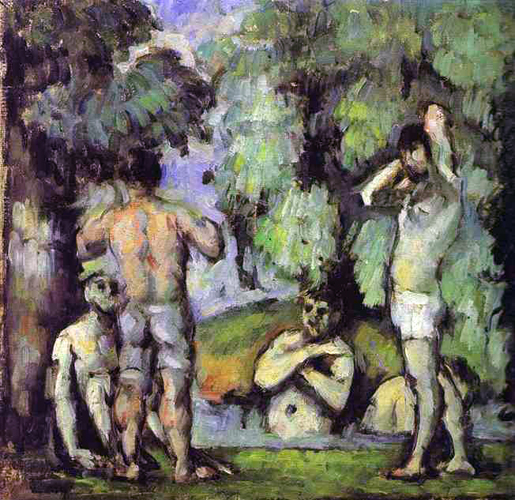

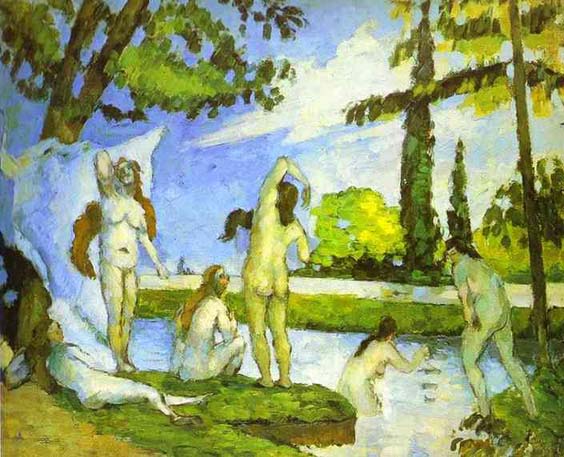

Cezanne's early work is often concerned with the figure in the landscape and comprises many paintings of groups of large, heavy figures in the landscape, imaginatively painted. Later in his career, he became more interested in working from direct observation and gradually developed a light, airy painting style that was to influence the Impressionists enormously. Nonetheless, in Cezanne's mature work we see the development of a solidified, almost architectural style of painting. Throughout his life he struggled to develop an authentic observation of the seen world by the most accurate method of representing it in paint that he could find. To this end, he structurally ordered whatever he perceived into simple forms and color planes. His statement "I want to make of impressionism something solid and lasting like the art in the museums", and his contention that he was recreating Poussin "after nature" underscored his desire to unite observation of nature with the permanence of classical composition.

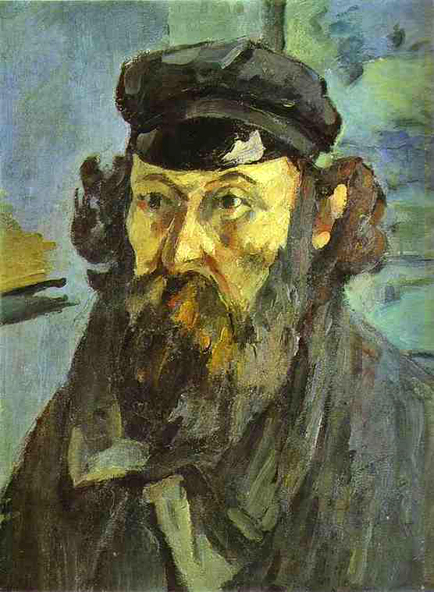

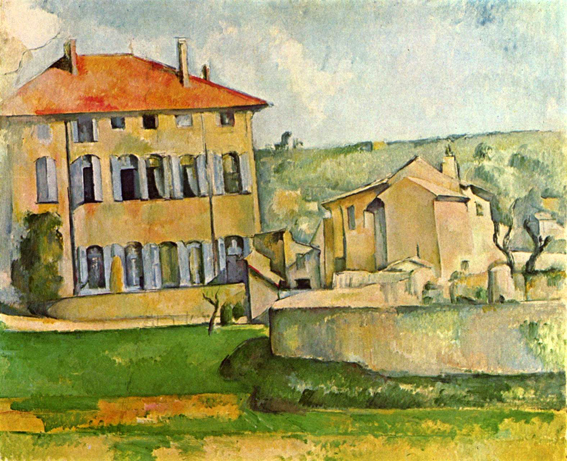

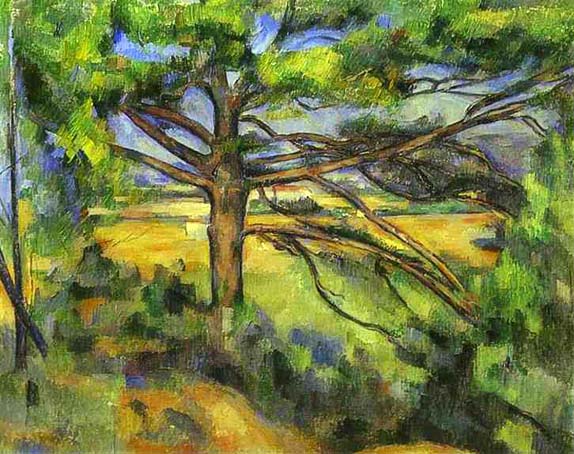

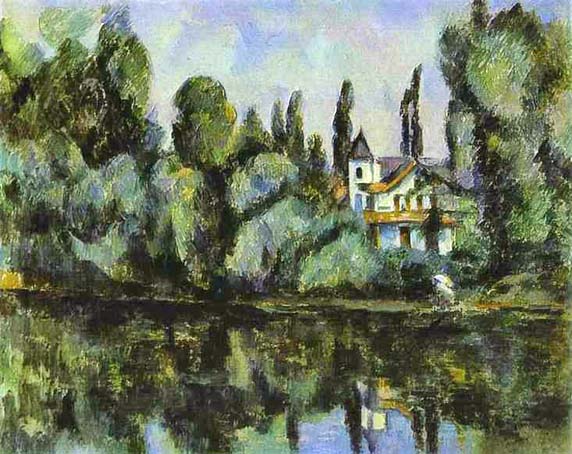

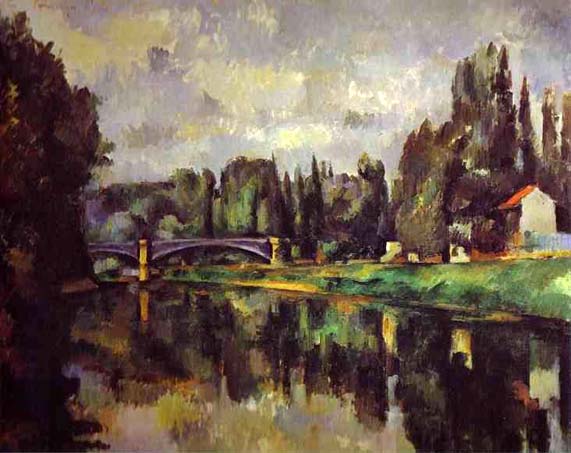

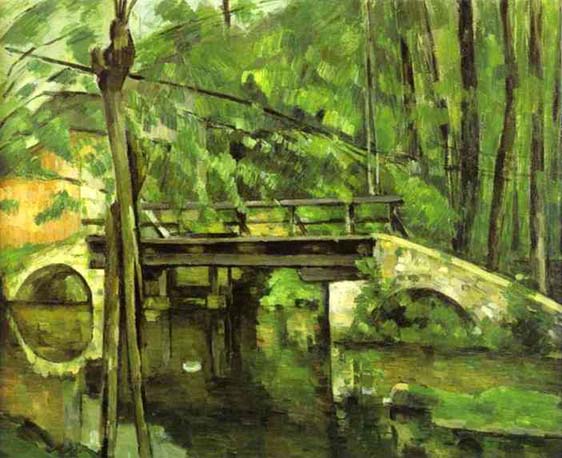

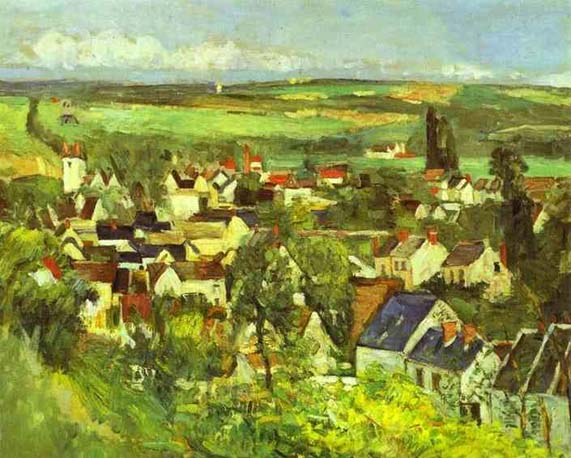

Cezanne immortalized the Provençal countryside with his broad, panoramic views. Often these are framed in branches, sometimes with architectural elements, but seldom with human activity. These too are still lifes. Cézanne's landscapes were not painted in the open air, as were those of the Impressionists, nor were they captured first with a camera. He composed the pictures the way he wanted them -- arranging the trees and the houses, probably gleaned from his sketchbooks, on the canvas in the configurations he decided upon.

Cezanne understood that a painting could not really do its subject justice. He knew that colors in nature and their combination with natural light could never be truly reproduced. He saw himself as an interpreter who had to accept the limitations of the medium and tried to transfer the images onto canvas the best way he could. He attempted to bridge the natural and artistic worlds. Hence Cézanne's works, in comparison with the paintings of many other Impressionists, only make sense as a whole, not in snippets, as the brush strokes and colors are meant to be interdependent on one another. This is especially true for pictures painted in the latter part of his career, when he used color in short strokes or in almost mosaic patches, all of equal intensity, throughout an entire painting. In his striving for perfection, this meant retouching the entire picture to recreate the all-important harmony. No wonder he scared his sitters.

He sometimes worked on the same picture for years, never satisfied with the results. He seldom signed his works, because he never considered them finished. Those he did sign had his mark of approval.

During the last decade of his life, Cezanne's paintings became more simplified, the objects in his landscapes reduced to components -- cylinders, cones and spheres. He is often seen as anticipating cubist and abstract art, because he reduced the imperfect forms of nature to these essential shapes. By the time of his death in 1906, Picasso and Braque were in the midst of exploring the most radical implications of his style. Maybe the world has finally caught up with Cezanne. Complexity is more admired now than it was 100 years ago, and since his reputation precedes him, perhaps the exhibition at the Grand Palais will make his work more accessible to the average museum-goer.

_ca_1881.jpg)

_ca_1876.jpg)

House of the Hanged Man, a motif from Auvers-sur-Oise, was probably painted in the spring of 1873. It is among the most heavily worked of Cezanne's canvases from this decade, and the rare appearance of a signature, and the fact that--with Cezanne's consent--it was exhibited several times during his lifetime, suggest that it was one of the rare paintings with which he was satisfied. It was executed on a standard portrait 15 canvas, whose squarish shape complements the composition and the solid block-like shapes within it. The ground, although undoubtedly pale because of the striking luminosity of the picture, is hard to identify with confidence without removing the work from its frame. The ground is effectively obliterated by the dense, thick opaque paint layer, although slight paint losses at the outer edges reveal both raw canvas and what is possibly a pale gray or putty-colored ground.

Repeated re-workings over almost the entire surface, characterize this painting. Canvas texture is practically irrelevant, but the effects of stiff, crusty paint dragged across previously dried brushstrokes, are fundamental to the grainy appearance of the picture. The tactile quality of natural surfaces, the crumbly limestone walls, roof thatch, and dusty road, are recreated by the built-up paint texture. Stiff hog's hair brushwork is combined with buttery slabs of color applied with a palette knife. In the foreground path this catches on previous brushstrokes, breaking the color to allow earlier colors to show through. This imitates the texture of natural surfaces and creates a vibrant, fragmented paint layer which scatters light, optically enhancing the picture's paleness and luminosity. Dabbed brush marks of subtly varied colors construct the thatched roof and the grass bank beneath it, on which the movement of the brushstrokes suggests the movement into space. This directs the eye toward the central pivotal point, which is the sunlit patch of ground between the two main houses.

Cezanne was interested in the simplification of naturally occurring forms to their geometric essentials, he wanted to "treat nature by the cylinder, the sphere, the cone" (a tree trunk may be conceived of as a cylinder, a human head a sphere, for example). Additionally, the concentrated attention with which he recorded his observations of nature resulted in a profound exploration of binocular vision, which results in two slightly different simultaneous visual perceptions, and provides us with depth perception and a complex knowledge of spatial relationships. We see two different views simultaneously; Cezanne employed this aspect of visual perception in his painting to varying degrees. The observation of this fact, coupled with Cézanne's desire to capture the truth of his own perception, often compelled him to render the outlines of forms so as to at once attempt to display the distinctly different views of both the left and right eyes. Thus Cezanne's work augments and transforms earlier ideals of perspective, in particular single-point perspective.

Cezanne's paintings were shown in the first exhibition of the Salon des Refuses in 1863, which displayed works not accepted by the jury of the official Paris Salon. The Salon rejected Cezanne's submissions every year from 1864 to 1869. Cezanne continued to submit works to the Salon until 1882. In that year, through the intervention of fellow artist Antoine Guillemet, Cezanne exhibited 'Portrait of Louis-Auguste Cezanne', Father of the Artist, reading 'l'Evenement', 1866 (National Gallery, Washington), his first and last successful submission to the Salon.

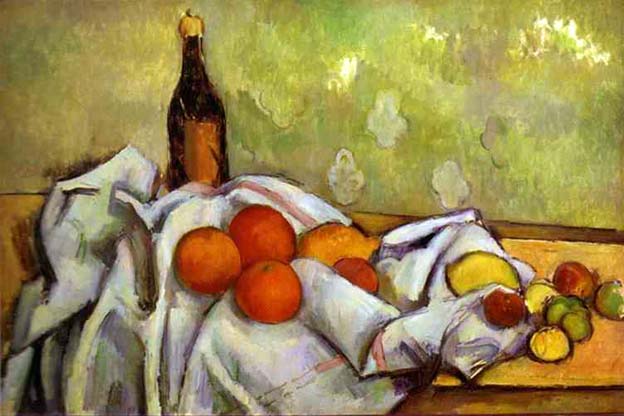

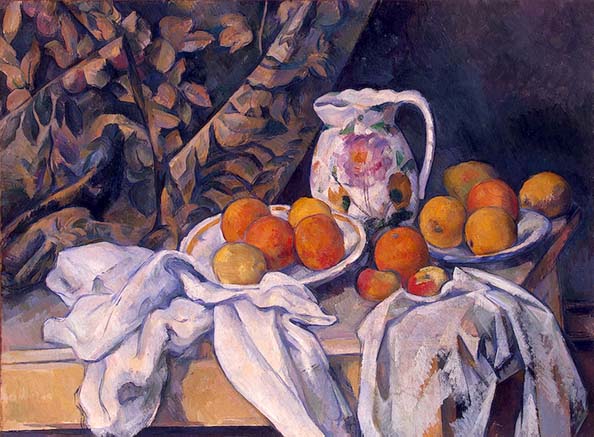

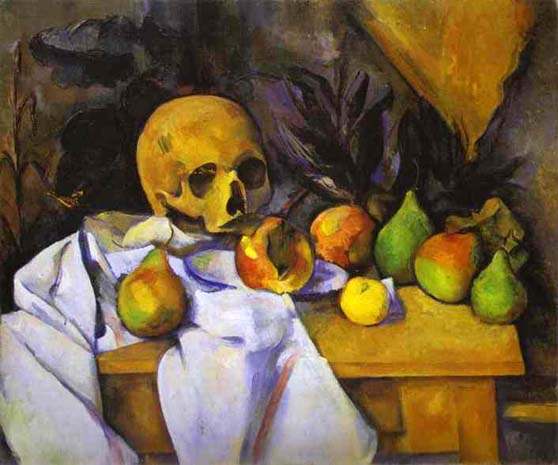

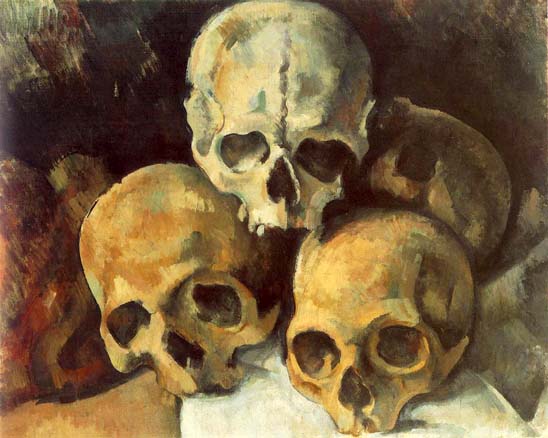

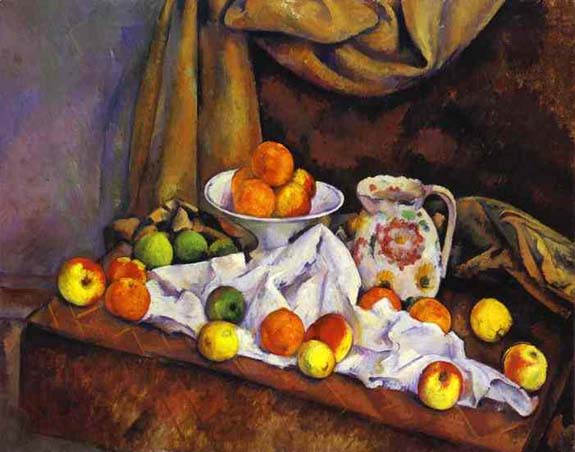

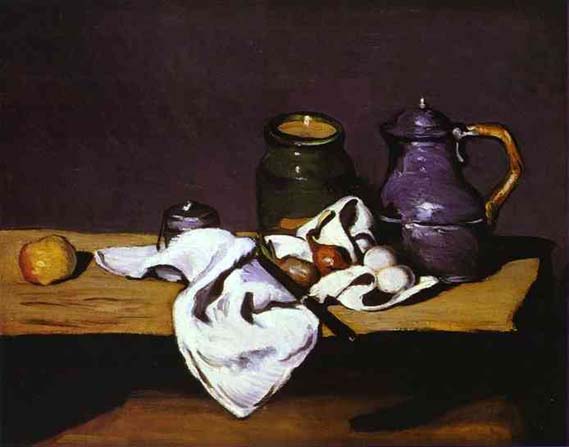

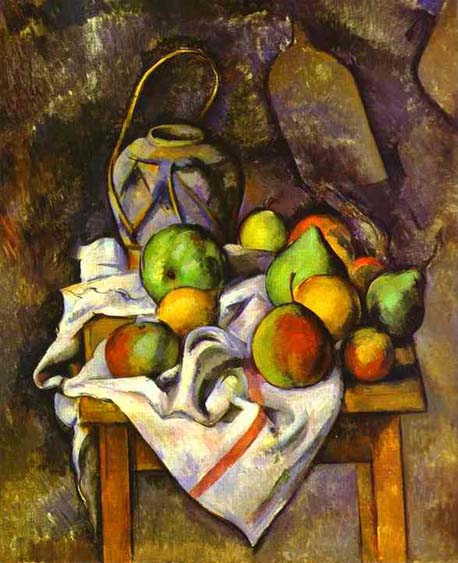

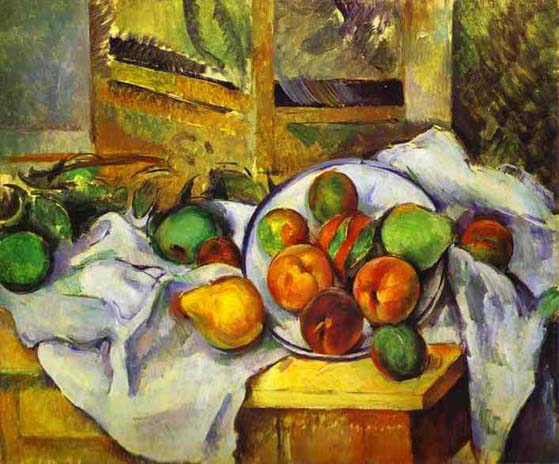

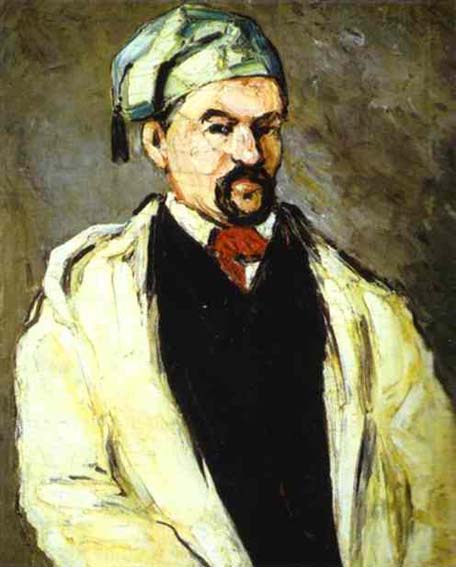

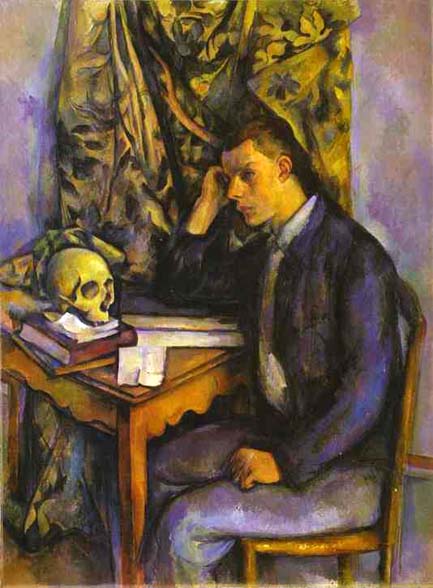

Before 1895 Cezanne exhibited twice with the Impressionists (at the first Impressionist exhibition in 1874 and the third Impressionist exhibition in 1877). In later years a few individual paintings were shown at various venues, until 1895, when the Parisian dealer, Ambroise Vollard, gave the artist his first solo exhibition. Despite the increasing public recognition and financial success, Cezanne chose to work in increasing artistic isolation, usually painting in the south of France, in his beloved Provence, far from Paris. He concentrated on a few subjects and was highly unusual for 19th-century painters in that he was equally proficient in each of these genres: still lifes, portraits, landscapes and studies of bathers. For the last, Cézanne was compelled to design from his imagination, due to a lack of available nude models. Like the landscapes, his portraits were drawn from that which was familiar, so that not only his wife and son but local peasants, children and his art dealer served as subjects. His still lifes are at once decorative in design, painted with thick, flat surfaces, yet with a weight reminiscent of Courbet. The 'props' for his works are still to be found, as he left them, in his studio (atelier), in the suburbs of modern Aix.

Paul Cezanne, one of the creators of modern art, was called the "solidifier of Impressionism''. And indeed he does not draw his picture before painting it: Instead, he creates space and depth of perspective by means of planes of color, which are freely associated and at the same time contrasted and compared. The facets which are thus produced create not just one but many perspectives, and in this way volume comes once again to dominate the composition, no longer a product of the line but rather of the color itself. His still-lifes, in their simplicity and delicate tonal harmony, are a typical work and thus ideal for an understanding of Cezanne's art.

Most of his pictures are still lifes. These were done in the studio, with simple props; a cloth, some apples, a vase or bowl and, later in his career, plaster sculptures. Cezanne's still lifes are both traditional and modern. The fruits and objects are readily identifiable, but they have no aroma, no sensual or tactile appeal and no other function other than as passive decorative objects coexisting in the same flat space. They bear no relation to the colorful vegetables of Provence -- gorgeous red tomatoes, purple aubergines, and bright green courgettes. In his pursuit of the essence of art, Cézanne had to suppress earthly delights.

_ca_1890.jpg)

Although religious images appeared less frequently in Cezanne's later work, he remained a devout Roman Catholic and said, "When I judge art, I take my painting and put it next to a God-made object like a tree or flower. If it clashes, it is not art."

One day, Cezanne was caught in a storm while working in the field. Only after working for two hours under a downpour did he decide to go home; but on the way he collapsed. He was taken home by a passing driver. His old housekeeper rubbed his arms and legs to restore the circulation; as a result, he regained consciousness. On the following day, he intended to continue working, but later on he fainted; the model with whom he was working called for help; he was put to bed, and he never left it again. He died a few days later, on 22 October 1906. He died of pneumonia and was buried at the old cemetery in his beloved hometown of Aix-en-Provence.

Various periods in the work and life of Cezanne have been defined. Cezanne created hundreds of paintings, some of which command considerable market prices. On 10 May 1999, Cezanne's painting 'Rideau, Cruchon et Compotier' sold for $60.5 million, the fourth-highest price paid for a painting up to that time. As of 2006, it is the most expensive still life ever sold at an auction.

In 1863 Napoleon III created by decree the Salon des Refuses, at which paintings rejected for display at the Salon of the Academie des Beaux-Arts were to be displayed. The artists of the refused works included the young Impressionists, who were considered revolutionary. Cezanne was influenced by their style but his inept social relations with them-he seemed rude, shy, angry, and given to depression-resulted in a period characterized by dark colors and the heavy use of black. His work from this period differs sharply from his earlier watercolors and sketches at the Ecole Speciale de dessin at Aix-en-Provence in 1859, or from his subsequent works. Among the works of his dark period were paintings such as 'The Murder' (ca 1867-68); the words antisocial or violent are often used.

After the start of the Franco-Prussian War in July, 1870, Cezanne and his mistress, Marie-Hortense Fiquet, left Paris for L'Estaque, near Marseilles, where he changed themes to predominantly landscapes. He was declared a draft-dodger in January, 1871, but the war ended in February and the couple moved back to Paris, in the summer of 1871. After the birth of their son Paul in January, 1872, in Paris, they moved to Auvers in Val-d'Oise near Paris. Cezanne's mother was kept a party to family events, but his father was not informed of Hortense for fear of risking his wrath. The artist received from his father an allowance of 100 francs.

Pissarro lived in Pontoise. There and in Auvers, he and Cezanne painted landscapes together. For a long time afterwards, Cezanne described himself as Pissarro's pupil, referring to him as "God the Father" and saying, "We all stem from Pissarro". Under Pissarro's influence Cezanne began to abandon dark colors and his canvases grew much brighter.

Leaving Hortense in the Marseille region, Cezanne moved between Paris and Provence, exhibiting in the first (1874) and third Impressionist shows (1877). In 1875, he attracted the attention of the collector Victor Chocquet, whose commissions provided some financial relief. But Cezanne's exhibited paintings attracted hilarity, outrage and sarcasm. Reviewer Louis Leroy said of Cezanne's portrait of Chocquet: "This peculiar looking head, the color of an old boot might give (a pregnant woman) a shock and cause yellow fever in the fruit of her womb before its entry into the world".

In March 1878, Cezanne's father found out about Hortense and threatened to cut Czaenne off financially but, in September, he decided to give him 400 francs for his family. Cezanne continued to migrate between the Paris region and Provence until Louis-Auguste had a studio built for him at his home, Jas de Bouffan, in the early 1880's. This was on the upper floor and an enlarged window was provided, allowing in the northern light but interrupting the line of the eaves. This feature remains today. Cezanne stabilized his residence in L'Estaque. He painted with Renoir there in 1882 and visited Renoir and Monet in 1883.

In the early 1880's the Cezanne family stabilized their residence in Provence, where they remained, except for brief sojourns abroad, from then on. The move reflects a new independence from the Paris-centered impressionists and a marked preference for the south, Cezanne's native soil. Hortense's brother had a house within view of Mont Sainte-Victoire at Estaque. A run of paintings of this mountain from 1880-1883 and others of Gardanne from 1885-1888, are sometimes known as "the Constructive Period".

The year 1886 was a turning point for the family. Cezanne married Hortense. In that year also, Cezanne's father died, leaving him the estate purchased in 1859; he was 47. By 1888 the family was in the former manor, Jas de Bouffan, a substantial house and grounds with outbuildings, which afforded a new-found comfort. This house, with much-reduced grounds, is now owned by the city and is open to the public on a restricted basis.

Also in that year Cezanne broke off his friendship with Emile Zola, after the latter used him, in large part, as the basis for the unsuccessful and ultimately tragic fictitious artist Claude Lantier, in a novel. Cezanne considered this a breach of decorum and a friendship begun in childhood was irreparably damaged.

Cezanne's idyllic period at Jas de Bouffan was temporary. From 1890 until his death he was beset by troubling events and he withdrew further into his painting, spending long periods as a virtual recluse. His paintings became well-known and sought after and he was the object of respect from a new generation of painters.

The problems began with the onset of diabetes in 1890, destabilizing his personality to the point where relationships with others were again strained. He travelled in Switzerland, with Hortense and his son, perhaps hoping to restore their relationship. Cezanne, however, returned to Provence to live; Hortense and Paul junior, to Paris. Financial need prompted Hortense's return to Provence but in separate living quarters. Cezanne moved in with his mother and sister. In 1891 he turned to Catholicism.

Cezanne alternated between painting at Jas de Bouffan and in the Paris region, as before. In 1895 he made a germinal visit to Bibemus Quarries and climbed Mt. Ste. Victoire. The labyrinthine landscape of the quarries must have struck a note, as he rented a cabin there in 1897 and painted extensively from it. The shapes are believed to have inspired the embryonic 'Cubist' style. Also in that year, his mother died, an upsetting event but one which made reconciliation with his wife possible. He sold the empty nest at Jas de Bouffan and rented a place on Rue Boulegon, where he built a studio.

The relationship, however, continued to be stormy. He needed a place to be by himself. In 1901 he bought some land along the Chemin des Lauves ("Lauves Road"), an isolated road on some high ground at Aix, and commissioned a studio to be built there (the 'atelier', now open to the public). He moved there in 1903. Meanwhile, in 1902, he had drafted a will excluding his wife from his estate and leaving everything to his son. The relationship was apparently off again; she is said to have burned the mementos of his mother.

From 1903 to the end of his life, he painted in his studio, working for a month in 1904 with Emile Bernard, who stayed as a house guest. After his death it became a monument, Atelier Paul Cezanne, or les Lauves.

After Cezanne died in 1906, his paintings were exhibited in Paris in a large scale museum-like retrospective in September 1907. The 1907 Cezanne retrospective at the Salon d'Automne greatly impacted the direction that the avant-garde in Paris took, lending credence to his position as one of the most influential artists of the 19th century and to the advent of Cubism.

Cezanne's explorations of geometric simplification and optical phenomena inspired Picasso, Braque, Gris, and others to experiment with ever more complex multiple views of the same subject, and, eventually, to the fracturing of form. Cezanne thus sparked one of the most revolutionary areas of artistic enquiry of the 20th Century, one which was to affect profoundly the development of modern art.

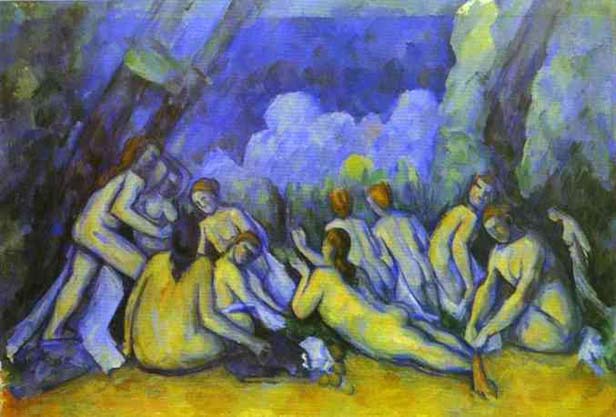

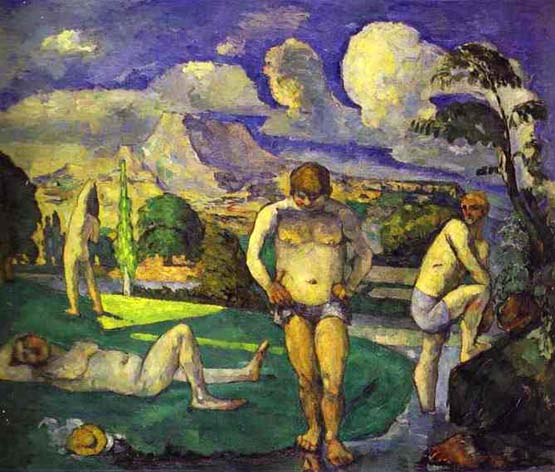

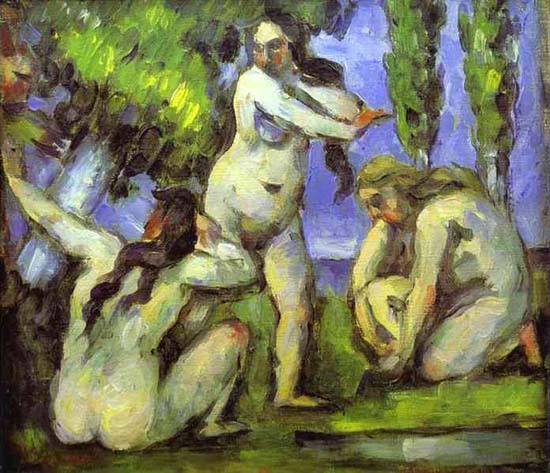

Bathers were another of Cezanne's themes. Women bathers are usually presented in large pyramidal groups, overlapping, mostly with their backs to the viewer. His men generally face forward, almost in a frieze. They are individuals in the same scenery, neither interacting nor overlapping. There is no eye contact between any of them. Czeanne's only real passion was his art, but that passion was never revealed on the canvas itself.

_ca_1880_81.jpg)

The Sainte-Victoire Mountain near Cezanne's home in Aix-en-Provence was one of his favorite subjects and he is known to have painted it over 60 times. Cezanne was fascinated by the rugged architectural forms in the mountains of Provence and painted the same scene from many different angles. He would use bold blocks of color to achieve a new spatial effect known as "flat-depth'' to accommodate the unusual geological forms of the mountains. Cezanne travelled widely in the Provence region and also enjoyed painting the coast at L'Estaque.

_1905.jpg)

The chateau in those paintings derives its name from rumors about its owner, rather than from its appearance. It was built in the 18th century by an industrialist from Marseilles, who manufactured lampblack paint (derived from soot). He also used it to decorate the interior walls and furniture of the château. As a result, he was associated with black magic among the local people, who believed that the château was also home to the devil.

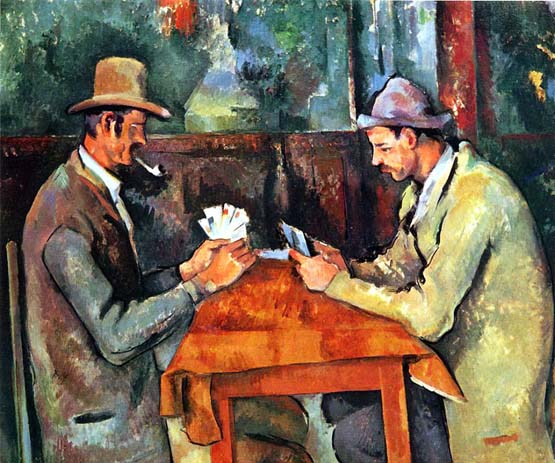

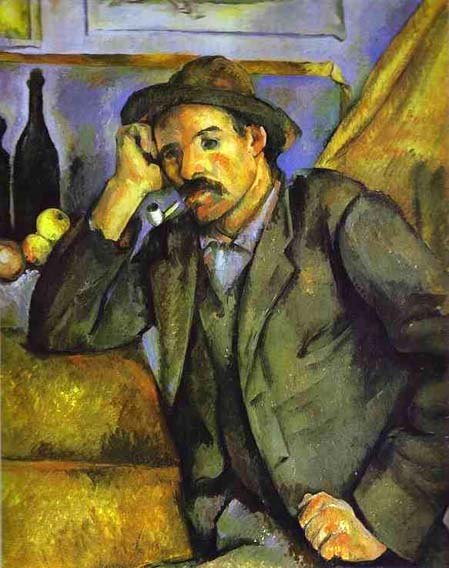

The abstract side of Cezanne's art has always been given due weight. It was amusingly emphasized by Ambroise Vollard who, after sitting many times for his portrait, asked how it was getting on. Cezanne's reply: "I am not displeased with the shirt-front" seemed to suggest that the human element did not enter into his calculations, that he was simply concerned with planes and gradations of color. On the other hand, his several self-portraits give a remarkable sense of character and towards 1890 there are other signs of his interest in the aspect of human beings, as for example the five versions of 'The Card Players' produced during this period at Aix. The Louvre version, reproduced here, with two players (and a bottle between them to mark the center of the symmetrically balanced composition) could be looked on in the abstract as a magnificent rendering of solid forms, given their appearance of structure by the gradated areas of the thinly applied color. But the fact remains that these are not abstractions but peasant card players in his native Provence. Whether by the sheer veracity of his study of facial planes or through some feeling of kinship with the solid countrymen he was portraying, Cezanne has made them live.

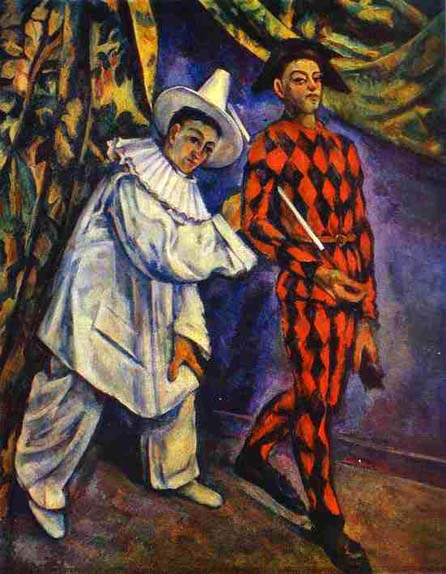

A picture of seventeenth-century card players from the studio of the brothers Le Nain in the museum at Aix and its peasant character first suggested the series to Cezanne though single peasant studies also show his interest in the essentially French type and his capacity to convey its essence. These pictures and the strange Mardi Gras of the same period (the clown and harlequin like two Romantic ghosts taking on substance and swaggering into a new era, perhaps by their strangeness leaving a deeper impression on French artists afterwards than by technique alone) realize the equation of form and content which Cezanne so often lamented he has not attained.

Even Cezanne's pictures of people can be regarded as still lifes, because he demanded that his models sit absolutely still. Sitting for him was something of a nightmare. Not only was he foul-tempered, he was an extremely slow painter, probably the reason his subjects always look tired and somber. Ambroise Vollard, the dealer who arranged Cezanne's first one-man show a century ago, posed 115 times for a single painting, sitting absolutely still "like an apple" and then Cezanne, dissatisfied, abandoned the picture with only two unpainted spots remaining. He told Vollard that with luck he would find the correct color and could finish the painting. "The prospect of this made me tremble," noted Vollard in his biography of the painter. In the artist's eye, there was no difference between a human sitter and a bowl of fruit, except that the reflection value and the palette were different. In the end, both his subjects and his fruit wilted.

_ca_1891.jpg)

_1892_96.jpg)

_ca_1880_81.jpg)

_ca_1866.jpg)

Source: Art Renewal Center

Source: WebMuseum: Cezanne, Paul

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.