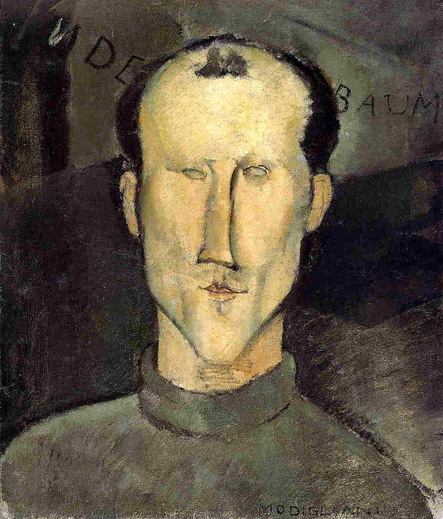

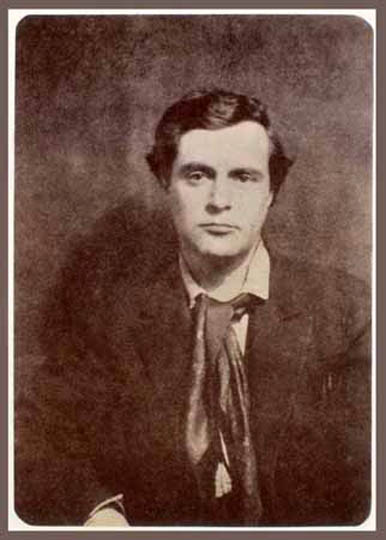

1884 - 1920

Amedeo Modigliani

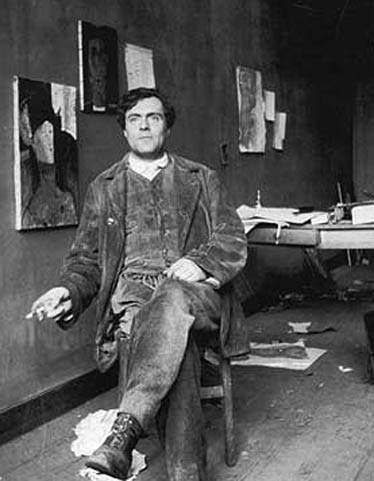

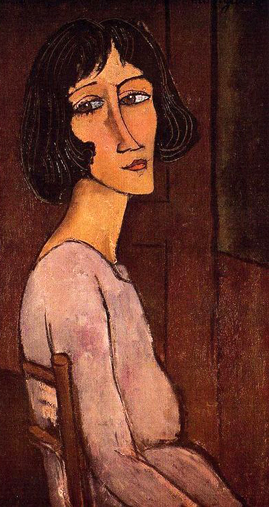

Amedeo Clemente Modigliani was an Italian artist who worked mainly in France. Primarily a figurative artist, he became known for paintings and sculptures in a modern style characterized by mask-like faces and elongation of form. He died in Paris of tubercular meningitis, exacerbated by poverty, overwork, and addiction to alcohol and narcotics.

Modigliani was born into a Jewish family in Livorno, Italy. A port city, Livorno had long served as a refuge for those persecuted for their religion, and was home to a large Jewish community. His maternal great-great-grandfather, Solomon Garsin, had immigrated to Livorno in the 18th century as a refugee.

Modigliani was the fourth child of Flaminio Modigliani and his wife, Eugenia Garsin. His father was a money-changer, but when his business failed, the family lived in poverty. Amedeo's birth saved the family from ruin, as according to an ancient law, creditors could not seize the bed of a pregnant woman or a mother with a newborn child. The bailiffs entered the family's home just as Eugenia went into labor; the family protected their most valuable assets by piling them on top of her.

Modigliani had a close relationship with his mother, who taught him at home until he was ten. Beset with health problems after an attack of pleurisy when he was about eleven, a few years later he developed a case of typhoid fever. When he was sixteen he was taken ill again and contracted the tuberculosis which would later claim his life. After Modigliani recovered from the second bout of pleurisy, his mother took him on a tour of southern Italy: Naples, Capri, Rome and Amalfi, then north to Florence and Venice.

His mother was, in many ways, instrumental in his ability to pursue art as a vocation. When he was eleven years of age, she had noted in her diary:

"The child's character is still so unformed that I cannot say what I think of it. He behaves like a spoiled child, but he does not lack intelligence. We shall have to wait and see what is inside this chrysalis. Perhaps an artist?"

Modigliani is known to have drawn and painted from a very early age, and thought himself "already a painter", his mother wrote, even before beginning formal studies. Despite her misgivings that launching him on a course of studying art would impinge upon his other studies, his mother indulged the young Modigliani's passion for the subject.

At the age of fourteen, while sick with typhoid fever, he raved in his delirium that he wanted, above all else, to see the paintings in the Palazzo Pitti and the Uffizi in Florence. As Livorno's local museum only housed a sparse few paintings by the Italian Renaissance masters, the tales he had heard about the great works held in Florence intrigued him, and it was a source of considerable despair to him, in his sickened state, that he might never get the chance to view them in person. His mother promised that she would take him to Florence herself, the moment he was recovered. Not only did she fulfill this promise, but she also undertook to enroll him with the best painting master in Livorno, Guglielmo Micheli.

Modigliani worked in Micheli's Art School from 1898 to 1900. Here his earliest formal artistic instruction took place in an atmosphere deeply steeped in a study of the styles and themes of 19th-century Italian art. In his earliest Parisian work, traces of this influence, and that of his studies of Renaissance art, can still be seen: this nascent work was shaped as much by such artists as Giovanni Boldini as by Toulouse-Lautrec.

Modigliani showed great promise while with Micheli, and only ceased his studies when he was forced to, by the onset of tuberculosis.

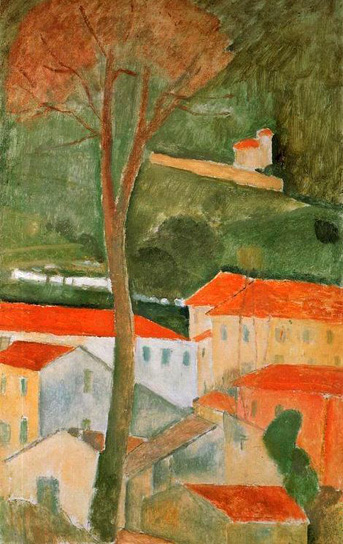

In 1901, while in Rome, Modigliani admired the work of Domenico Morelli, a painter of melodramatic Biblical studies and scenes from great literature. It is ironic that he should be so struck by Morelli, as this painter had served as an inspiration for a group of iconoclasts who went known by the title "the Macchiaioli" (from macchia -"dash of color", or, more derogatively, "stain"), and Modigliani had already been exposed to the influences of the Macchiaioli. This minor, localized landscape movement was possessed of a need to react against the bourgeois styling of the academic genre painters. While sympathetically connected to (and actually pre-dating) the French Impressionists, the Macchiaioli did not make the same impact upon international art culture as did the contemporaries and followers of Monet, and are today largely forgotten outside of Italy.

Modigliani's connection with the movement was through Guglielmo Micheli, his first art teacher. Micheli was not only a Macchiaioli himself, but had been a pupil of the famous Giovanni Fattori, a founder of the movement. Micheli's work, however, was so fashionable and the genre so commonplace that the young Modigliani reacted against it, preferring to ignore the obsession with landscape that, as with French Impressionism, characterized the movement. Micheli also tried to encourage his pupils to paint en plein air, but Modigliani never really got a taste for this style of working, sketching in cafés, but preferring to paint indoors, and especially in his own studio. Even when compelled to paint landscapes, Modigliani chose a proto-Cubist palette more akin to Cézanne than to the Macchiaioli.

While with Micheli, Modigliani not only studied landscape, but also portraiture, still-life, and the nude. His fellow students recall that the latter was where he displayed his greatest talent, and apparently this was not an entirely academic pursuit for the teenager: when not painting nudes, he was occupied with seducing the household maid.

Despite his rejection of the Macchiaioli approach, Modigliani nonetheless found favor with his teacher, who referred to him as "Superman", a pet name reflecting the fact that Modigliani was not only quite adept at his art, but also that he regularly quoted from Nietzsche's 'Thus Spoke Zarathustra'. Fattori himself would often visit the studio, and approved of the young artist's innovations.

In 1902, Modigliani continued what was to be a life-long infatuation with life drawing, enrolling in the Accademia di Belle Arti (Scuola Libera di Nudo, or "Free School of Nude Studies") in Florence. A year later while still suffering from tuberculosis, he moved to Venice, where he registered to study at the Istituto di Belle Arti.

It is in Venice that he first smoked hashish and, rather than studying, began to spend time frequenting disreputable parts of the city. The impact of these lifestyle choices upon his developing artistic style is open to conjecture, although these choices do seem to be more than simple teenage rebellion, or the clichéd hedonism and bohemianism that was almost expected of artists of the time; his pursuit of the seedier side of life appears to have roots in his appreciation of radical philosophies, such as those of Nietzsche.

Having been exposed to erudite philosophical literature as a young boy under the tutelage of Isaco Garsin, his maternal grandfather, he continued to read and be influenced through his art studies by the writings of Nietzsche, Baudelaire, Carducci, Comte de Lautréamont, and others, and developed the belief that the only route to true creativity was through defiance and disorder.

Letters that he wrote from his 'sabbatical' in Capri in 1901 clearly indicate that he is being more and more influenced by the thinking of Nietzsche. In these letters, he advised friend Oscar Ghiglia:

"(hold sacred all) which can exalt and excite your intelligence (and) seek to provoke and to perpetuate these fertile stimuli, because they can push the intelligence to its maximum creative power."

The work of Lautréamont was equally influential at this time. This doomed poet's Les Chants de Maldoror became the seminal work for the Parisian Surrealists of Modigliani's generation, and the book became Modigliani's favorite to the extent that he learnt it by heart. The poetry of Lautréamont is characterized by the juxtaposition of fantastical elements, and by sadistic imagery; the fact that Modigliani was so taken by this text in his early teens gives a good indication of his developing tastes. Baudelaire and D'Annunzio similarly appealed to the young artist, with their interest in corrupted beauty, and the expression of that insight through Symbolist imagery.

Modigliani wrote to Ghiglia extensively from Capri, where his mother had taken him to assist in his recovery from tuberculosis. These letters are a sounding board for the developing ideas brewing in Modigliani's mind. Ghiglia was seven years Modigliani's senior, and it is likely that it was he who showed the young man the limits of his horizons in Livorno. Like all precocious teenagers, Modigliani preferred the company of older companions, and Ghiglia's role in his adolescence was to be a sympathetic ear as he worked himself out, principally in the convoluted letters that he regularly sent, and which survive today.

"Dear friend,

I write to pour myself out to you and to affirm myself to myself.

I am the prey of great powers that surge forth and then disintegrate.

A bourgeois told me today - insulted me - that I or at least my brain was lazy. It did me good. I should like such a warning every morning upon awakening: but they cannot understand us nor can they understand life."

In 1906 Modigliani moved to Paris, then the focal point of the avant-garde. In fact, his arrival at the center of artistic experimentation coincided with the arrival of two other foreigners who were also to leave their marks upon the art world: Gino Severini and Juan Gris.

He settled in Le Bateau-Lavoir, a commune for penniless artists in Montmartre, renting himself a studio in Rue Caulaincourt. Even though this artists' quarter of Montmartre was characterized by generalized poverty, Modigliani himself presented-initially, at least-as one would expect the son of a family trying to maintain the appearances of its lost financial standing to present: his wardrobe was dapper without ostentation, and the studio he rented was appointed in a style appropriate to someone with a finely attuned taste in plush drapery and Renaissance reproductions. He soon made efforts to assume the guise of the bohemian artist, but, even in his brown corduroys, scarlet scarf and large black hat, he continued to appear as if he were slumming it, having fallen upon harder times.

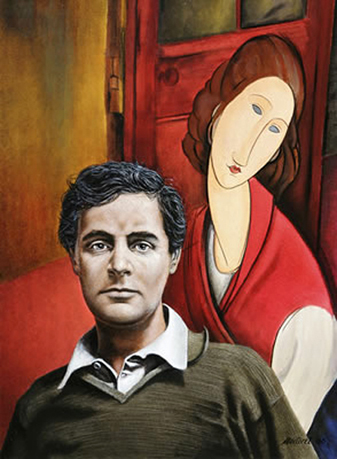

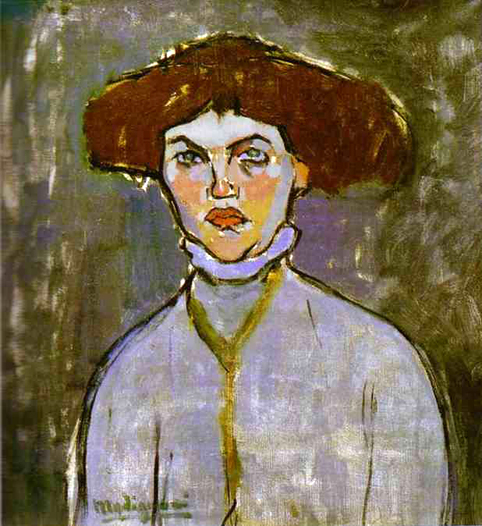

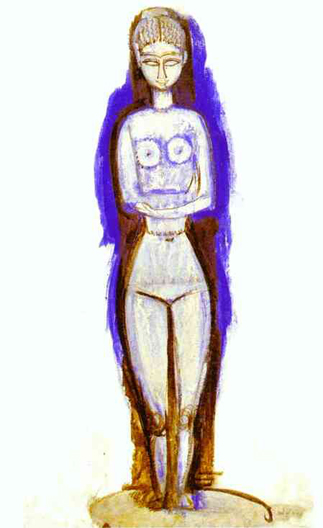

Female Nude with Hat: ca 1908

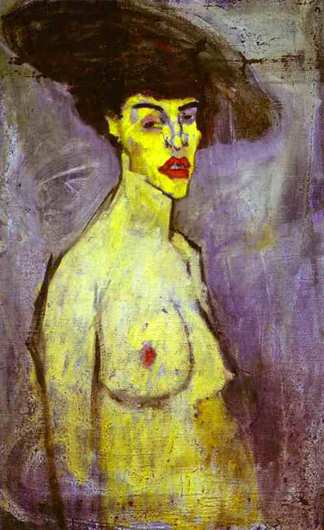

Head of a Woman with a Hat: 1907

Head of a Young Woman: 1908

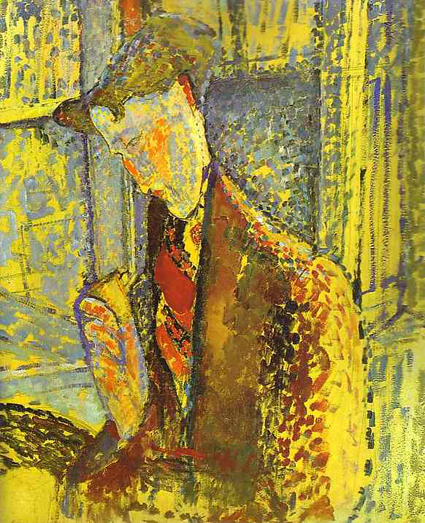

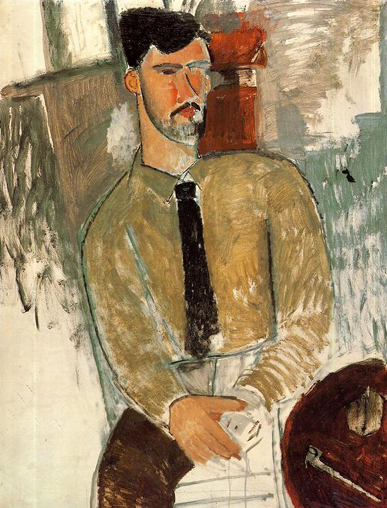

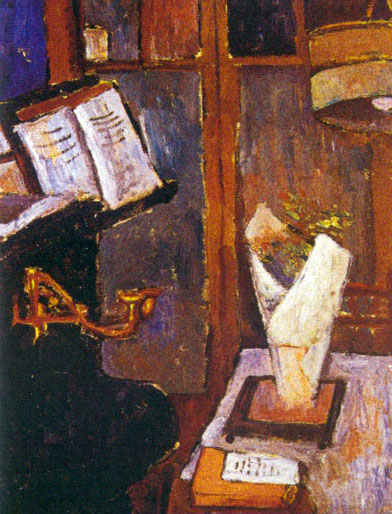

Study for The Cellist: 1909

The Cellist

The Jewess: ca 1908

Woman in Yellow Jacket

(The Amazon): 1909

_1909.jpg)

When he first arrived in Paris, he wrote home regularly to his mother, he sketched his nudes at the Académie Colaross, and he drank wine in moderation. He was at that time considered by those who knew him as a bit reserved, verging on the asocial. He is noted to have commented, upon meeting Picasso who, at the time, was wearing his trademark workmen's clothes, that even though the man was a genius, that did not excuse his uncouth appearance.

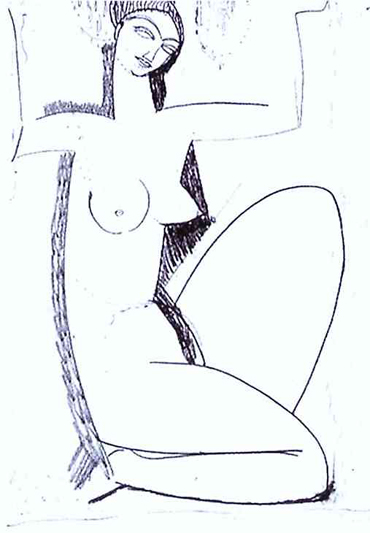

Caryatid: ca 1912-13

(Pencil)

Within a year of arriving in Paris, however, his demeanor and reputation had changed dramatically. He transformed himself from a dapper academician artist into a sort of prince of vagabonds

The poet and journalist Louis Latourette, upon visiting the artist's previously well-appointed studio after his transformation, discovered the place in upheaval, the Renaissance reproductions discarded from the walls, the plush drapes in disarray. Modigliani was already an alcoholic and a drug addict by this time, and his studio reflected this. Modigliani's behavior at this time sheds some light upon his developing style as an artist, in that the studio had become almost a sacrificial effigy for all that he resented about the academic art that had marked his life and his training up to that point.

Not only did he remove all the trappings of his bourgeois heritage from his studio, but he also set about destroying practically all of his own early work. He explained this extraordinary course of actions to his astonished neighbors thus:

"Childish baubles, done when I was a dirty bourgeois."

The motivation for this violent rejection of his earlier self is the subject of considerable speculation. The self-destructive tendencies may have stemmed from his tuberculosis and the knowledge (or presumption) that the disease had essentially marked him for an early death; within the artists' quarter, many faced the same sentence, and the typical response was to set about enjoying life while it lasted, principally by indulging in self-destructive actions. For Modigliani such behavior may have been a response to a lack of recognition; he sought the company of artists such as Utrillo and Soutine, seeking acceptance and validation for his work from his colleagues.

Modigliani's behavior stood out even in these Bohemian surroundings: he carried on frequent affairs, drank heavily, and used absinthe and hashish. While drunk, he would sometimes strip himself naked at social gatherings. He became the epitome of the tragic artist, creating a posthumous legend almost as well-known as that of Vincent van Gogh.

During the 1920's, in the wake of Modigliani's career and spurred on by comments by André Salmon crediting hashish and absinthe with the genesis of Modigliani's style, many hopefuls tried to emulate his "success" by embarking on a path of substance abuse and bohemian excess. Salmon claimed-erroneously-that whereas Modigliani was a totally pedestrian artist when sober:

"From the day that he abandoned himself to certain forms of debauchery, an unexpected light came upon him, transforming his art. From that day on, he became one who must be counted among the masters of living art."

While this propaganda served as a rallying cry to those with a romantic longing to be a tragic, doomed artist, these strategies did not produce unique artistic insights or techniques in those who did not already have them.

In fact, art historians suggest that it is entirely possible for Modigliani to have achieved even greater artistic heights had he not been immured in, and destroyed by, his own self-indulgences. We can only speculate what he might have accomplished had he emerged intact from his self-destructive explorations.

During his early years in Paris, Modigliani worked at a furious pace. He was constantly sketching, making as many as a hundred drawings a day. However, many of his works were lost-destroyed by him as inferior, left behind in his frequent changes of address, or given to girlfriends who did not keep them.

He was first influenced by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, but around 1907 he became fascinated with the work of Paul Cézanne. Eventually he developed his own unique style, one that cannot be adequately categorized with other artists.

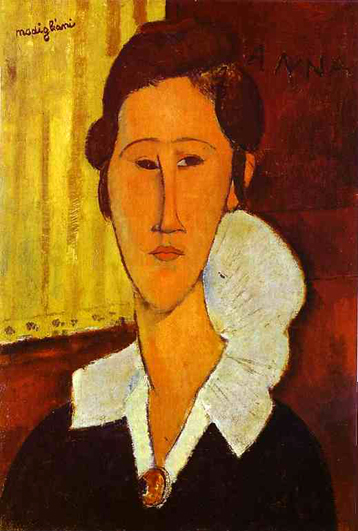

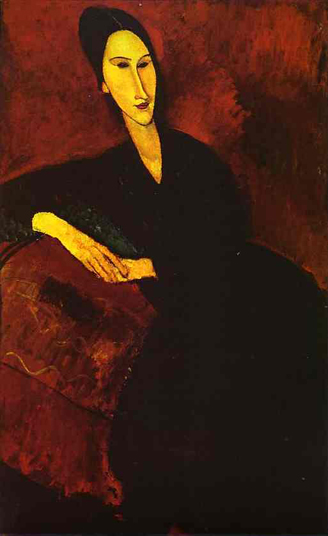

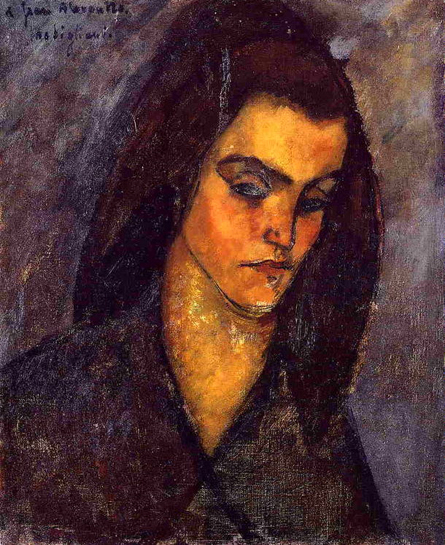

He met the first serious love of his life, Russian poet Anna Akhmatova, in 1910, when he was 26. They had studios in the same building, and although 21-year-old Anna was recently married, they began an affair. Tall with dark hair (like Modigliani's), pale skin and grey-green eyes, she embodied Modigliani's aesthetic ideal and the pair became engrossed in each other. After a year, however, Anna returned to her husband.

Anna Akhmatova: ca 1911

Anna Akhmatova

(Pencil): ca 1911

Anna Akhmatova and Amedeo Modigliani

In 1909, Modigliani returned home to Livorno, sickly and tired from his wild lifestyle. Soon he was back in Paris, this time renting a studio in Montparnasse. He originally saw himself as a sculptor rather than a painter, and was encouraged to continue after Paul Guillaume, an ambitious young art dealer, took an interest in his work and introduced him to sculptor Constantin Brancusi.

Although a series of Modigliani's sculptures were exhibited in the Salon d'Automne of 1912, by 1914 he abandoned sculpting and focused solely on his painting, a move precipitated by the difficulty in acquiring sculptural materials due to the outbreak of war, and by Modigliani's physical debilitation.

Caryatid: 1914

(Limestone)

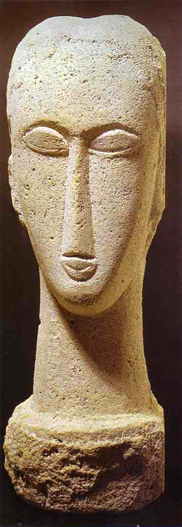

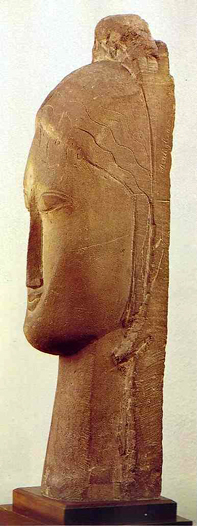

Head: ca 1911

(Limestone)

Head: ca 1911

(Limestone

Stone Head: 1911-12

(Limestone)

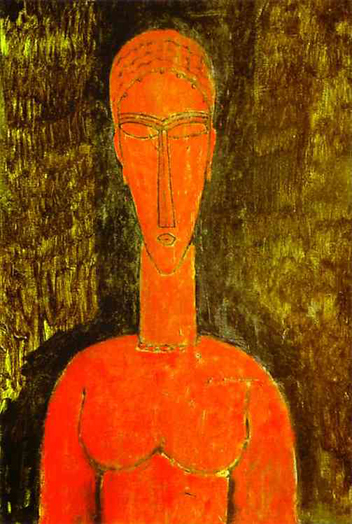

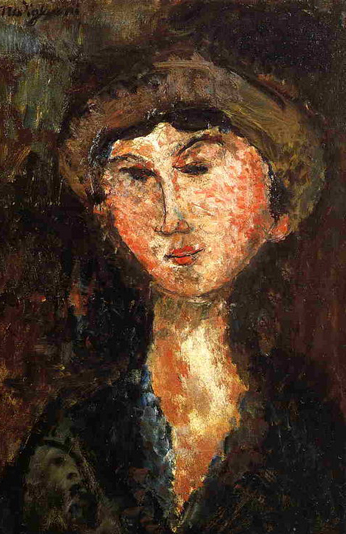

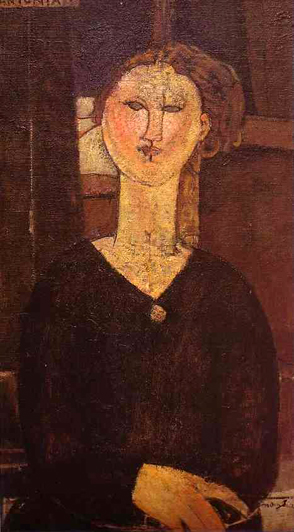

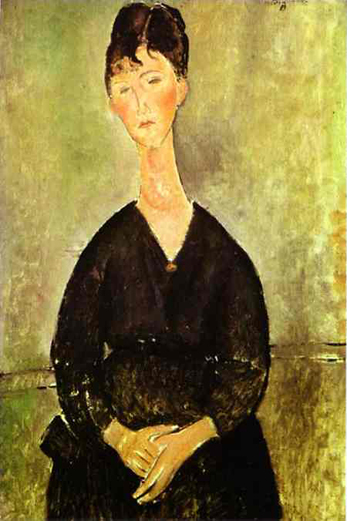

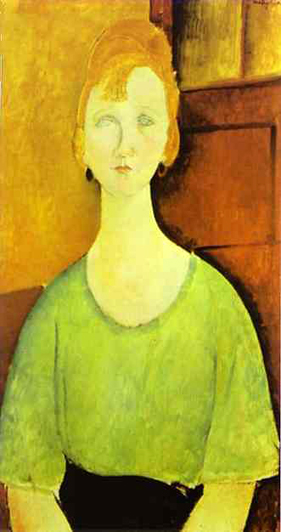

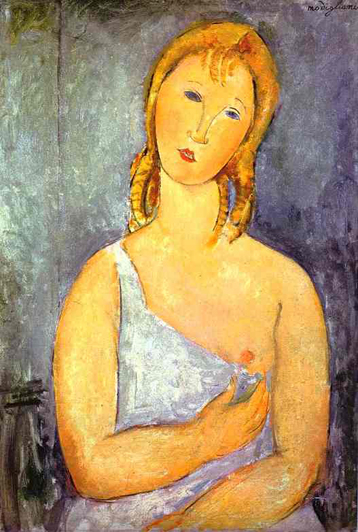

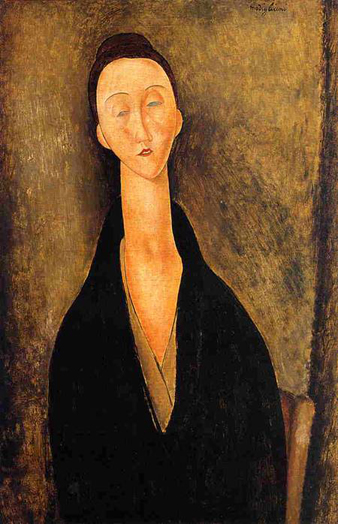

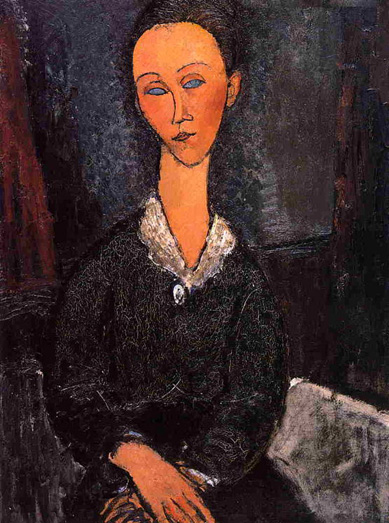

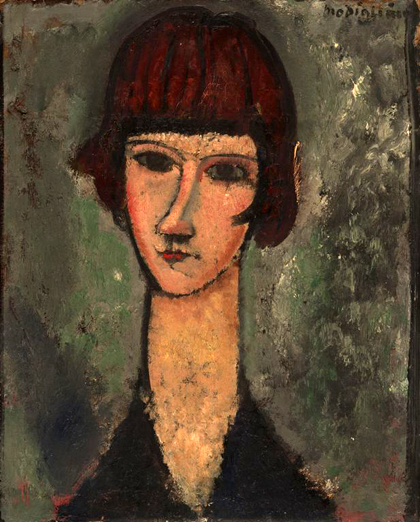

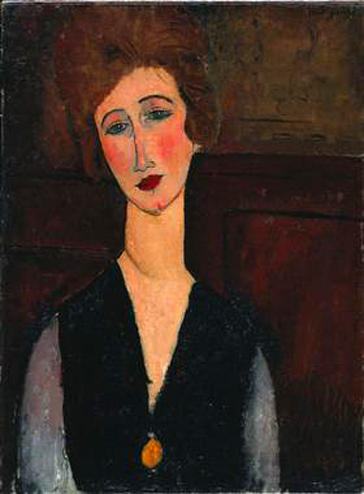

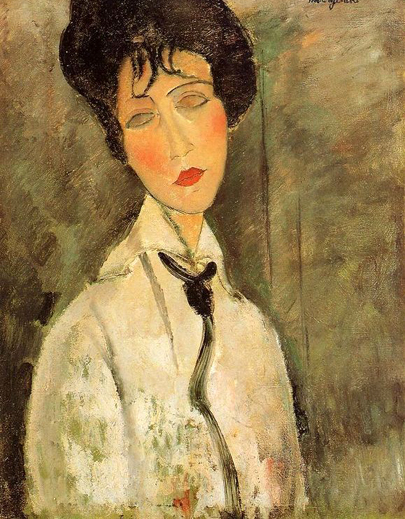

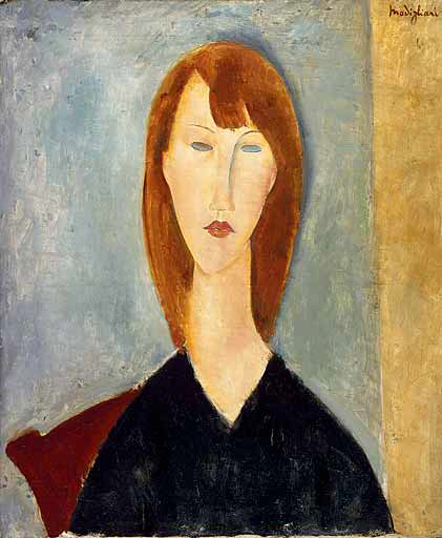

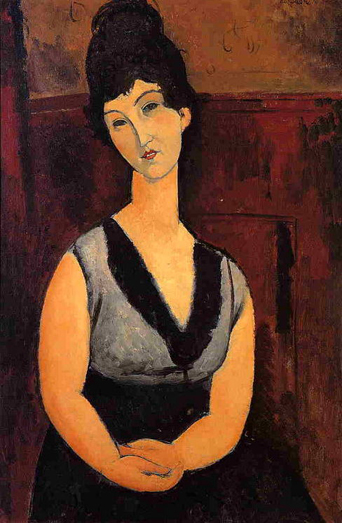

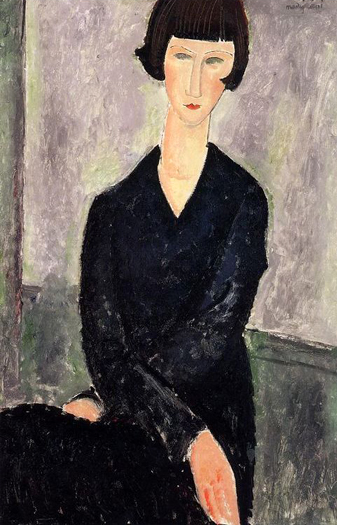

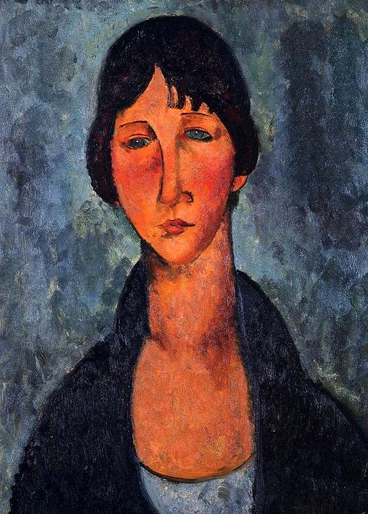

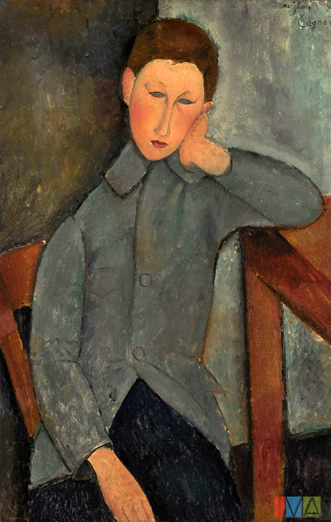

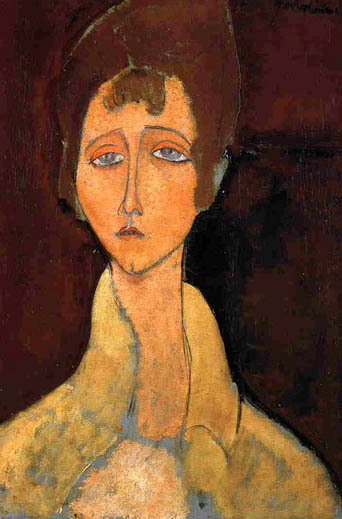

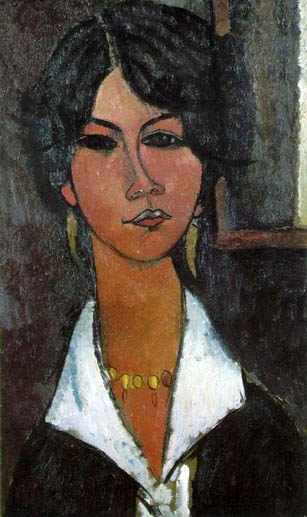

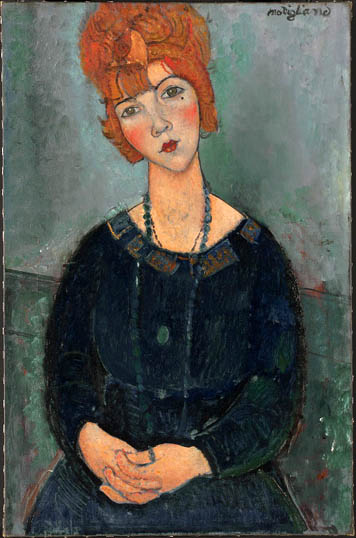

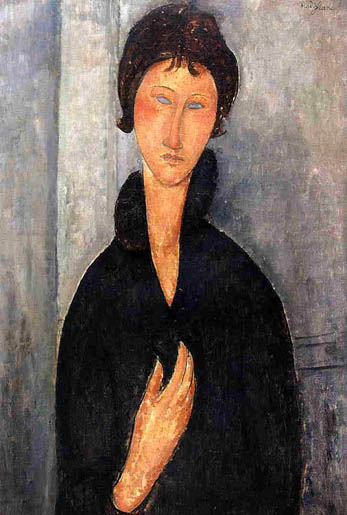

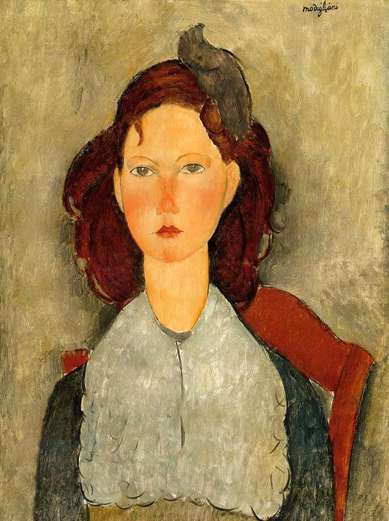

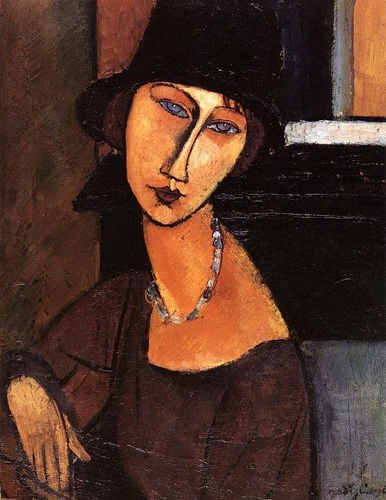

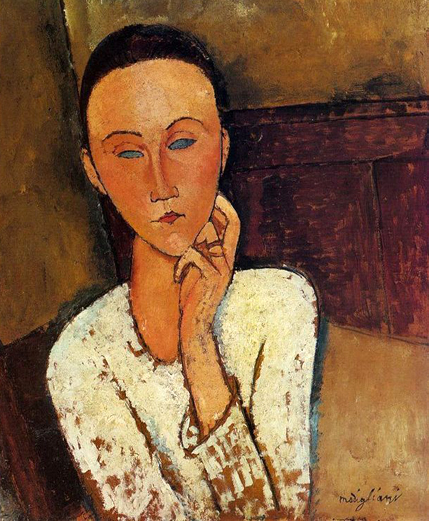

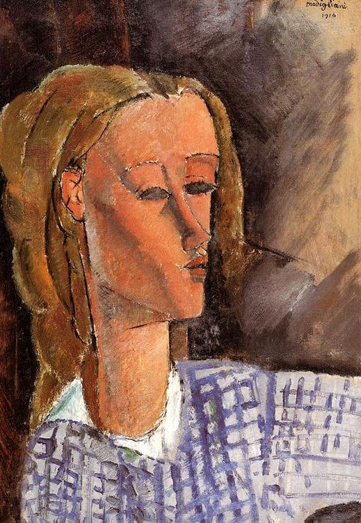

The Red Bust: 1913

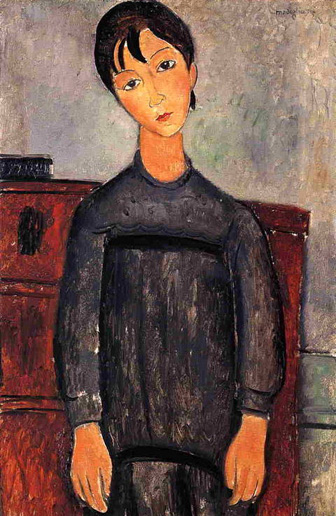

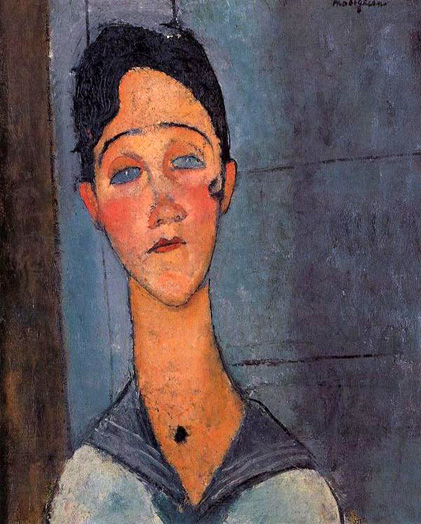

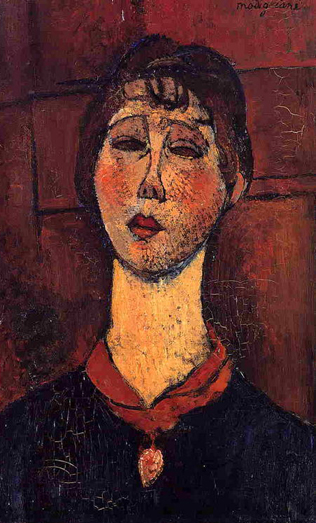

In Modigliani's art, there is evidence of the influence of art from Africa and Cambodia which he may have seen in the Musée de l'Homme, but his stylizations are just as likely to have been the result of his being surrounded by Medieval sculpture during his studies in Northern Italy. A possible interest in African tribal masks seems to be evident in his portraits. In both his painting and sculpture, the sitters' faces resemble ancient Egyptian painting in their flat and mask-like appearance, with distinctive almond eyes, pursed mouths, twisted noses, and elongated necks. However these same characteristics are shared by Medieval European sculpture and painting.

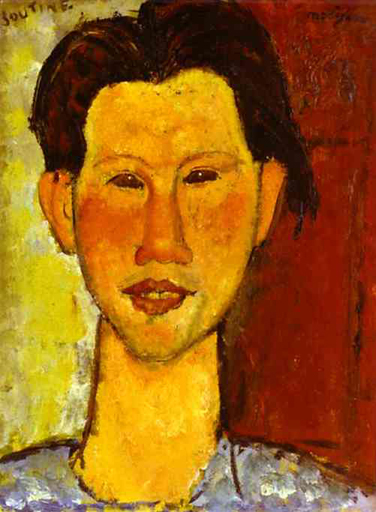

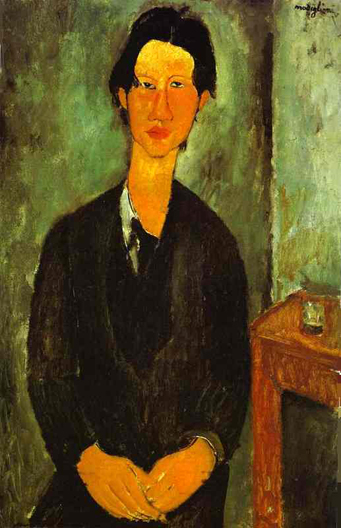

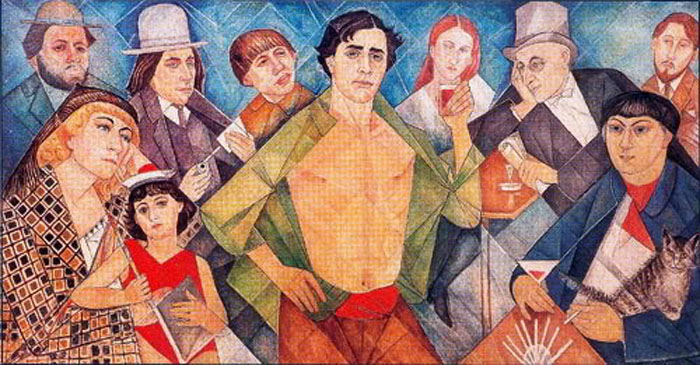

Modigliani painted a series of portraits of contemporary artists and friends in Montparnasse: Chaim Soutine, Moise Kisling, Pablo Picasso, Diego Rivera, Marie "Marevna" Vorobyev-Stebeslka, Juan Gris, Max Jacob, Blaise Cendrars, and Jean Cocteau, all sat for stylized renditions.

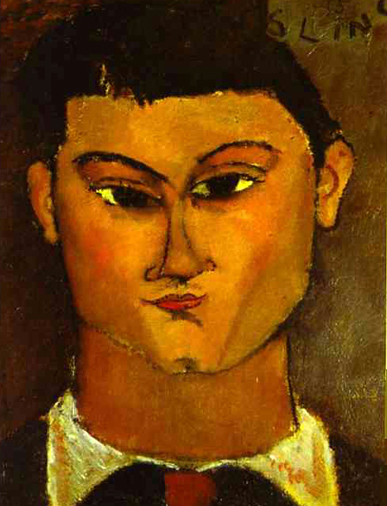

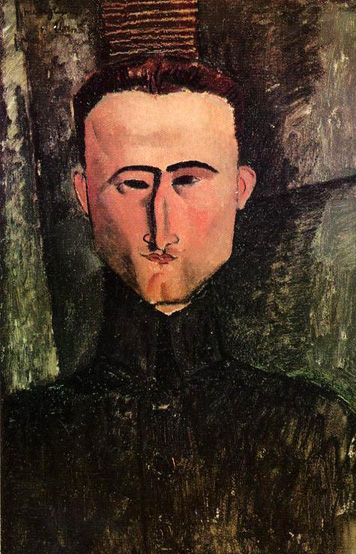

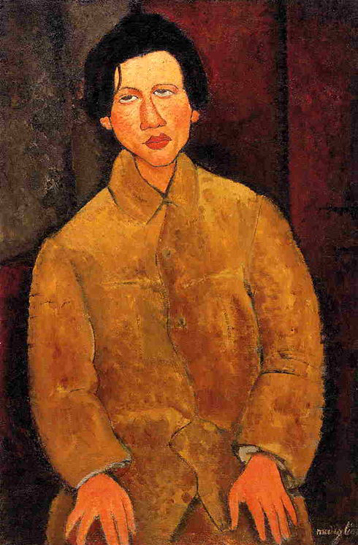

Portrait of Chaim Soutine: 1915

Chaïm Soutine (1893 - 1943) was a Jewish, expressionist painter from Belarus. He has been interpreted as both a forerunner of Abstract Expressionism and as a proponent of painting in the European tradition exemplified by the works of Rembrandt, Chardin, and Courbet.

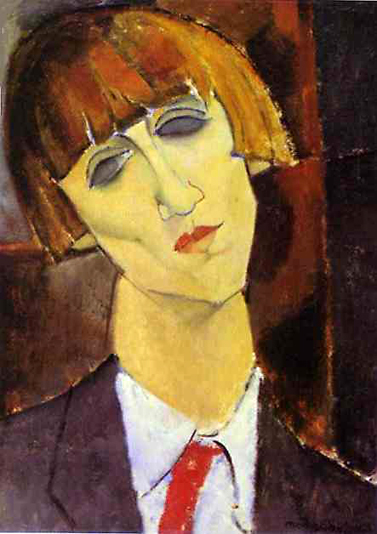

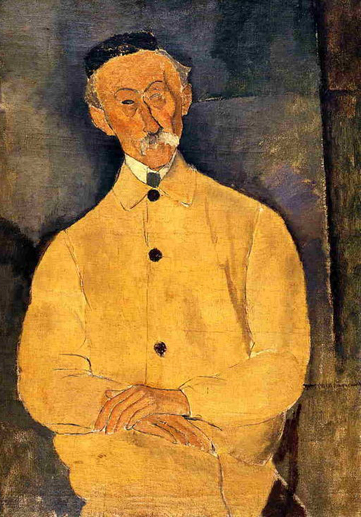

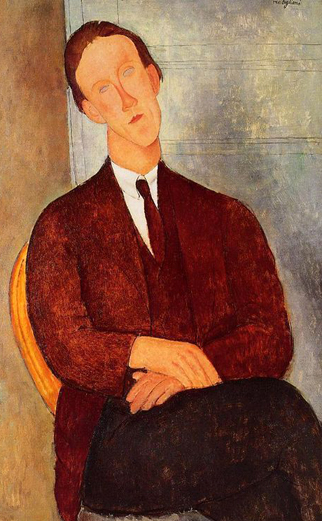

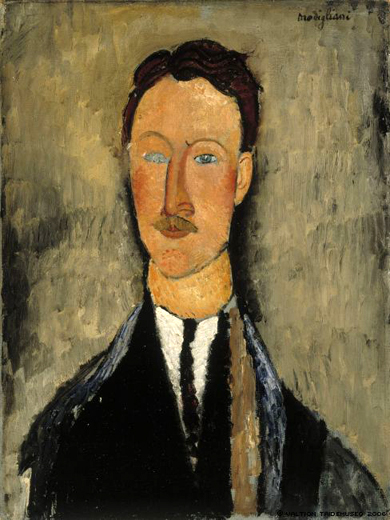

Portrait of the Painter Moise Kisling: 1915

Moise Kisling (1891 - 1953) was a Polish painter. Born in Krakow, Poland, he studied at the School of Fine Arts in Krakow, where he was encouraged to go on to Paris, France, at the time, the center for artistic creativity.

In 1910, Kisling moved to Montmartre and a few years later to Montparnasse. At the outbreak of World War I he volunteered for service in the French Foreign Legion, and in 1915 he was seriously wounded in the Battle of the Somme, for which he was awarded French citizenship.

Kisling lived and worked in Montparnasse where he was part of the renowned artistic community gathered there at the time. He became close friends with many of his contemporaries, including his neighbor, Amedeo Modigliani, who painted him in 1915 (today at the Musee d'Art Moderneas). His style used in painting landscapes is similar to that of Marc Chagall, but, a master at depicting the female body, his surreal nudes and portraits earned him the widest acclaim.

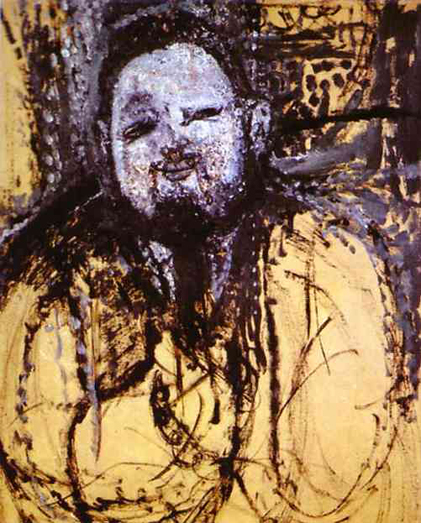

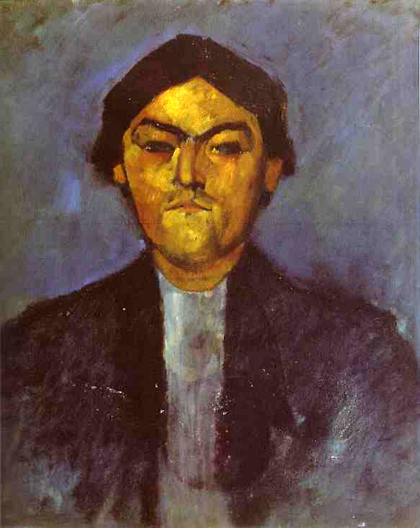

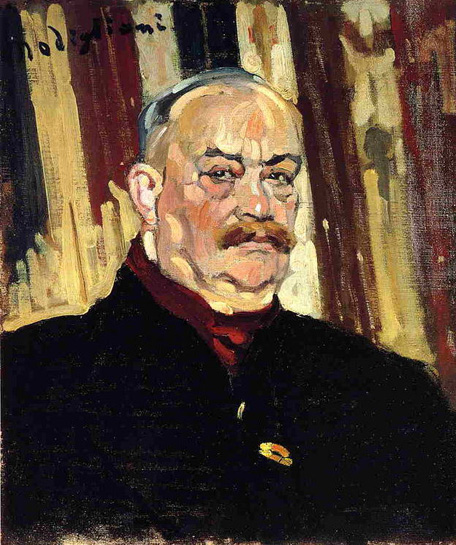

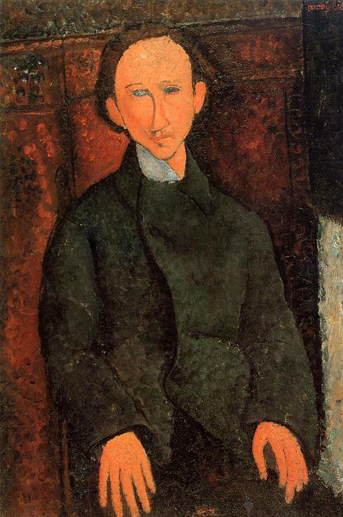

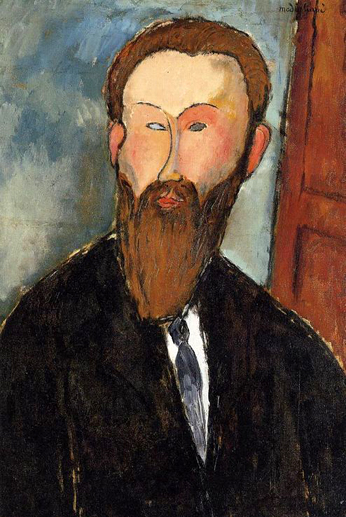

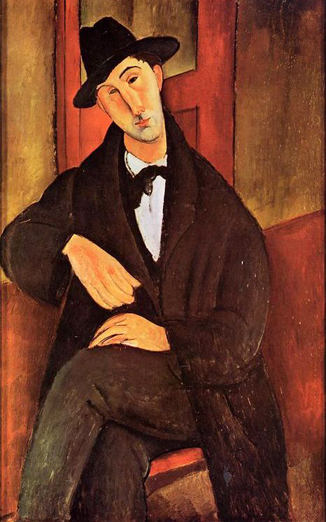

Portrait of Pablo Picasso: 1915

Pablo Picasso (1881 - 1973) was a Spanish painter, draftsman, and sculptor. He is one of the most recognized figures in 20th-century art. He is best known for co-founding the Cubist movement and for the wide variety of styles embodied in his work. Among his most famous works are the proto-Cubist Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907) and Guernica (1937), his portrayal of the German bombing of Guernica during the Spanish Civil War.

Picasso demonstrated uncanny artistic talent in his early years, painting in a realistic manner through his childhood and adolescence; during the first decade of the twentieth century his style changed as he experimented with different theories, techniques, and ideas. Picasso's creativity manifested itself in numerous mediums, including painting, sculpture, drawing, and architecture. His revolutionary artistic accomplishments brought him universal renown and immense fortunes throughout his life, making him the best-known figure in twentieth century art.

Portrait of Diego Rivera ca: 1914

Portrait of Diego Rivera: 1914

Diego Rivera (1886 - 1957) was born in Guanajuato City, Guanajuato. He was a world-famous Mexican painter, an active Communist, and husband of Frida Kahlo, 1929-1939 and 1940-1954 (her death). Rivera's large wall works in fresco helped establish the Mexican Mural Renaissance. Between 1922 and 1953, Rivera painted murals in Mexico City, Chapingo, Cuernavaca, San Francisco, Detroit, and New York City. In 1931, a retrospective exhibition of his works was displayed at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City.

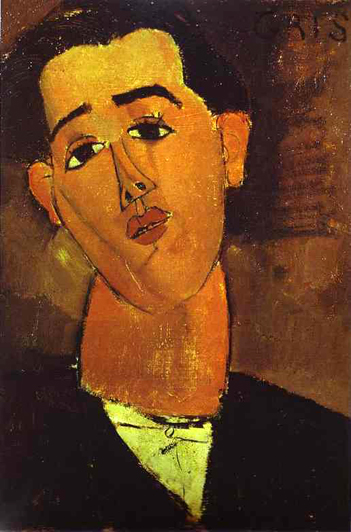

Portrait of Juan Gris: 1915

José Victoriano González-Pérez (1887 - 1927), better known as Juan Gris, was a Spanish painter and sculptor who lived and worked in France most of his life. His works are closely connected to the emergence of an innovative artistic genre-Cubism, creating several of the movement's most distinctive works.

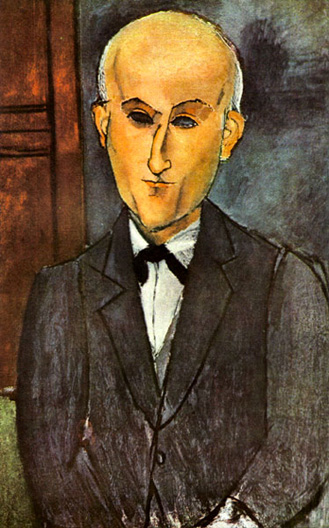

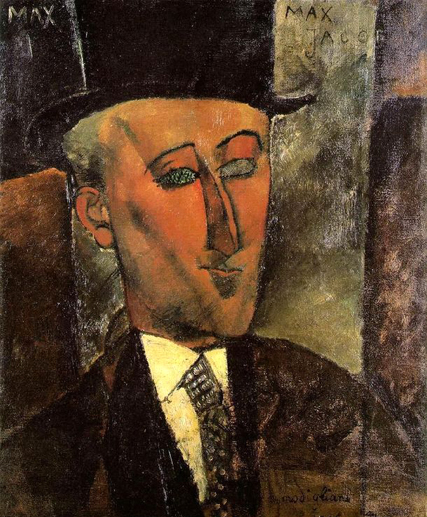

Max Jacob: 1916

Max Jacob (1876 - 1944) was a French poet, painter, writer, and critic. After spending his childhood in Quimper, Brittany, France, he enrolled in the Paris Colonial School, which he left in 1897 for an artistic career. On the Boulevard Voltaire, he shared a room with Pablo Picasso, who introduced him to Guillaume Apollinaire, who in turn introduced him to Georges Braque. He would become close friends with Jean Cocteau, Jean Hugo, Christopher Wood and Amedeo Modigliani, who painted his portrait in 1916. He also befriended and encouraged the artist Romanin, otherwise known as French politician and future Resistance leader Jean Moulin.

Quotes of Max Jacob

Friendship is inexplicable, it should not be explained if one doesn't want to kill it.

The poet's expression of joy conceals his despair at not having found the reality of joy.

What is called a sincere work is one that is endowed with enough strength to give reality to an illusion.

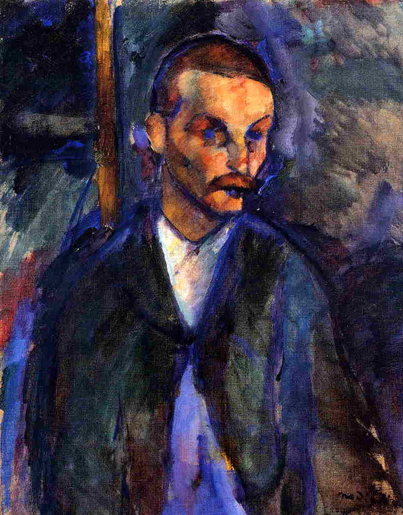

Portrait of Max Jacob

This work with its firmly designed face and realistic rendering of the features, shows the influence of Cubism's geometric style, but with a difference. With his fluid lines and forms, he adapted the Cubists' techniques not only for the model, but for the entire composition.

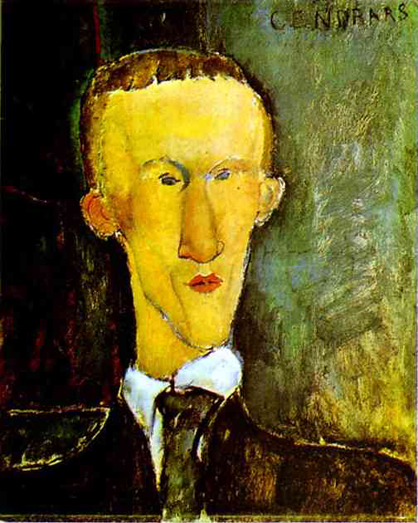

Blaise Cendrars: 1918

Frédéric Louis Sauser (1887 - 1961), better known as Blaise Cendrars, was a Swiss novelist and poet naturalized French in 1916. He was a writer of considerable influence in the modernist movement.

His writing career was interrupted by World War I. When it began, he and Italian writer Ricciotto Canudo appealed to other foreign artists to join the French army in battle. He himself joined the French Foreign Legion. He was sent to the front line in the Somme where from mid-December 1914 until February 1915 he was in the line at Frise (at La Grenouillère and the Bois de la Vache). He described this experience in the books La Main Coupée ("The Severed Hand") and J'ai Tué ("I have Killed"). It was during the bloody attacks in Champagne in September 1915 that Blaise Cendrars lost his right arm and was discharged from the army.

Jean Cocteau introduced him to Eugenia Errázuriz, who proved a supportive if at times possessive patron. Around 1918 he visited her house and was so taken with the simplicity of the décor, he was inspired to write the sequence of poems D'Oultremer à Indigo ("From Ultramarine to Indigo"). He stayed with Eugenia in her house in Biarritz, in a room decorated with murals by Pablo Picasso. At this time he was also driving an old Alfa Romeo which had been 'color-coordinated' by Georges Braque. Cendrars became an important part of the era of artistic creativity in Montparnasse at the time, his writings a literary epic of the modern adventurer. He was a friend of Henry Miller as well as many of the writers, painters, and sculptors living in Paris. In 1918, his friend Amedeo Modigliani painted his portrait. He was acquainted with Ernest Hemingway, who mentions having seen him "with his broken boxer's nose and his pinned-up empty sleeve, rolling a cigarette with his one good hand," at the Closerie des Lilas, in Paris.

After the war, he became involved in the movie industry in Italy, France, and the United States. Needing to generate sufficient income, after 1925 he stopped publishing poetry and focused on novels or short stories.

During World War II, tragedy struck when his youngest son was killed in an accident while escorting American planes in Morocco. In occupied France, the Gestapo listed Cendrars as a Jewish writer of "French expression."

In 1950, he ended his life of travel by settling down on the rue Jean-Dolent in Paris, across from the La Santé Prison. T here he collaborated frequently with Radio diffusion Française. He finally published again in 1956. The novel, Emmène-moi au bout du monde !…, was to be his last work before suffering a stroke in 1957.

In 1960, André Malraux bestowed upon him the title of Commander of the Légion d'honneur for his wartime service. A year later, he also received the Paris Grand Prix for literature. Shortly after, he died. His ashes now rest at Le Tremblay-sur-Mauldre.

Portrait of Jean Cocteau: 1916

Jean Maurice Eugène Clément Cocteau (1889 -1963) was a French poet, novelist, dramatist, designer, boxing manager, playwright, artist and filmmaker. Along with other Surrealists of his generation (Jean Anouilh and René Char for example) Cocteau grappled with the "algebra" of verbal codes old and new, mise en scène language and technologies of modernism to create a paradox: a classical avant-garde. His circle of associates, friends and lovers included Pablo Picasso, Jean Hugo, Jean Marais, Henri Bernstein, Édith Piaf, whom he cast in one of his one act plays entitled Le Bel Indifferent in 1940, and Raymond Radiguet.

His work was played out in the theatrical world of the Grands Theatres, the Boulevards and beyond during the Parisian epoque he both lived through and helped define and create. His versatile, unconventional approach and enormous output brought him international acclaim.

Quotes of Jean Cocteau

After the writer's death, reading his journal is like receiving a long letter.

All good music resembles something. Good music stirs by its mysterious resemblance to the objects and feelings which motivated it.

Art produces ugly things which frequently become more beautiful with time. Fashion, on the other hand, produces beautiful things which always become ugly with time.

Children and lunatics cut the Gordian knot which the poet spends his life patiently trying to untie.

Everything one does in life, even love, occurs in an express train racing toward death. To smoke opium is to get out of the train while it is still moving. It is to concern oneself with something other than life or death.

I have lost my seven best friends, which is to say God has had mercy on me seven times without realizing it. He lent a friendship, took it from me, sent me another.

Man seeks to escape himself in myth, and does so by any means at his disposal. Drugs, alcohol, or lies. Unable to withdraw into himself, he disguises himself. Lies and inaccuracy give him a few moments of comfort.

One of the characteristics of the dream is that nothing surprises us in it. With no regret, we agree to live in it with strangers, completely cut off from our habits and friends.

The actual tragedies of life bear no relation to one's preconceived ideas. In the event, one is always bewildered by their simplicity, their grandeur of design, and by that element of the bizarre which seems inherent in them.

At the outset of World War I, Modigliani tried to enlist in the army but was refused because of his poor health.

Known as Modì, which translates as 'cursed', by many Parisians, but as Dedo to his family and friends, Modigliani was a handsome man, and attracted much female attention.

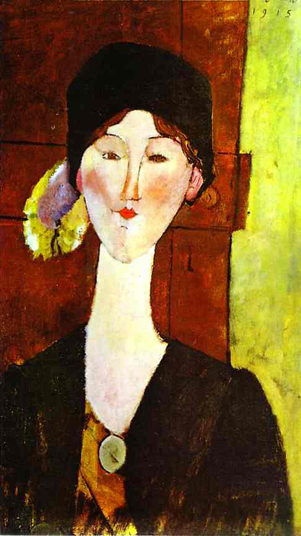

Women came and went until Beatrice Hastings entered his life. She stayed with him for almost two years, was the subject for several of his portraits, including Madame Pompadour, and the object of much of his drunken wrath.

Madam Pompadour

(Portrait of Beatrice Hastings): 1915

_1915.jpg)

Amedeo Clemente Modigliani was one of the most unique and innovative Italian artists, who always rendered an idiosyncratic and distinctive painting style. Controversies however, surrounded his destitute life and was therefore, never famous among his contemporaries. Modigliani adopted the 'Expressionist' style of painting, where the depiction of emotions was primary. The painter blended this emotional high with twisted reality for a distinct expression in his portraits, including his masterpiece "Madame Pompadour - Portrait of Beatrice Hastings."

Modigliani was a very handsome and attractive man, well capable of luring women easily. In 1914, he met a very eccentric English poet, Beatrice Hastings, who later became his mistress. During this time, Modigliani lived a very Bohemian lifestyle, heavily addicted to drugs & alcohol. Beatrice Hastings even quoted, "A complex character. A swine and a pearl. Met him in 1914 at a crémerie. I sat opposite him. Hashish and brandy. Not at all impressed. Didn't know who he was. He looked ugly, ferocious and greedy. Met him again at the Café Rotonde. He was shaved and charming. Raised his cap with a pretty gesture, blushed and asked me to come and see his work. And I went. He always had a book in his pocket. Lau Tremont's Maldoror. The first oil painting was of Kisling. He had no respect for anyone except Picasso and Max Jacob. Detested Cocteau. Never completed anything good under the influence of hashish."

Beatrice Hastings was a very pompous and haughty woman, who was an unfortunate victim of Amedeo's drunken rage. She was the model for many of his paintings, which eventually resulted in a famous fourteen portraits series, in 1915, entitled "Madame Pompadour - Portrait of Beatrice Hastings," of which only three were exhibited. Beatrice Hastings was a very proud writer, literary critic, and a vocal feminist. Her nature at times was a complete contrast to that of Modigliani's. Due to her haughtiness, he nicknamed her Madame or madam Pompadour and created her portraits. The portraits were famous for their ability to portray the existing close relationship between Modigliani and Beatrice. Modigliani always gave key attention to the facial features of the subjects. Since he also adopted the style of 'Cubism,' his portraits were sharp and projected in manner.

Due to Beatrice's nature, Amedeo depicted her as an aristocratic 'English Madame.' The portrait, through its title subtlety, depicted the relationship between King Louis V & his mistress, which ironically manifested his relationship with Beatrice Hastings. Amedeo and Hastings' relationship lasted for two years, which died an unfortunate death, due to their contrasting attitudes.

In the "Madame Pompadour - Portrait of Beatrice Hastings," Modigliani rendered 'Cubism' by simultaneously depicting the sides of the face through different viewpoints, as well as having a collage effect with the writings on stonewall. The 'Expressionist' style was evident through the distortion of the face and the depiction of Modigliani's personal interpretation of Beatrice Hastings. The misspelled graffiti written on the painting as well as its backdrop of a stonewall reflect the deviation from reality.

Beatrice Hastings: 1915

Portrait of Beatrice Hastings: 1915

Beatrice Hastings

When the British painter Nina Hamnett arrived in Montparnasse in 1914, on her first evening there the smiling man at the next table in the café introduced himself as Modigliani; painter and Jew. They became great friends.

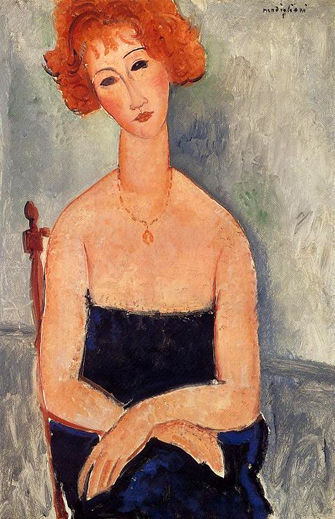

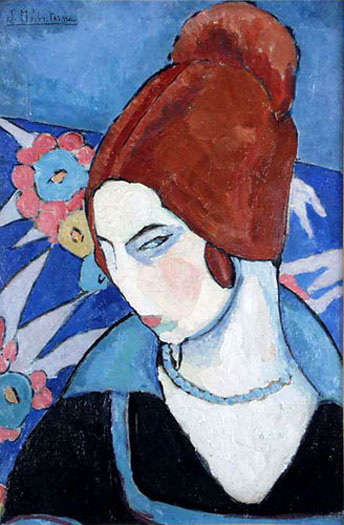

Woman with Red Hair: 1917

(aka Nina Hamnet, at least I think it is?)

Known as "Modì" by the art world, but as "Dedo" to his friends, Amedeo Modigliani was an extremely handsome man to whom females were greatly attracted. Women came and went until Beatrice Hastings entered his life. She stayed for almost two years, was the subject for several of his portraits, including "Madame Pompadour" shown here, and the object of much of his drunken wrath. Drunk, he was a bitter, angry person, always looking for a fight as was depicted in the famous drawing by Marie Vassilieff. Sober, he was graciously timid and charming, would quote Dante Alighieri and recite poems from Lautreamont's book, Les Chants de Maldoror, a copy of which he always carried with him. When the English painter Nina Hamnett arrived in Montparnasse in 1914, on her first evening there the smiling man at the next table in the café introduced himself as "Modigliani, painter and Jew". They became great friends.

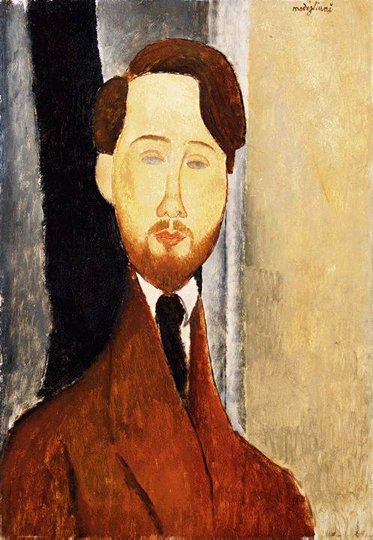

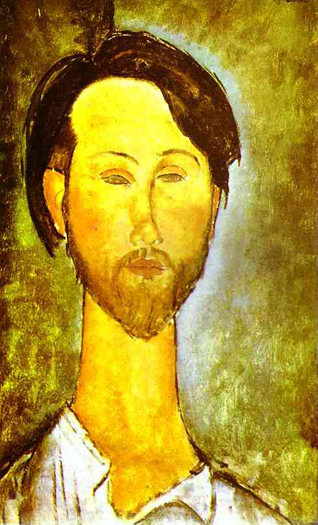

In 1916, Modigliani befriended the Polish poet and art dealer Leopold Zborovski and his wife Anna.

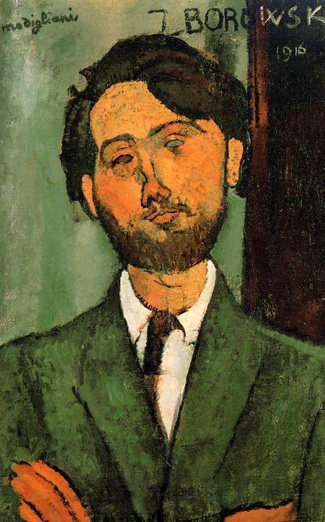

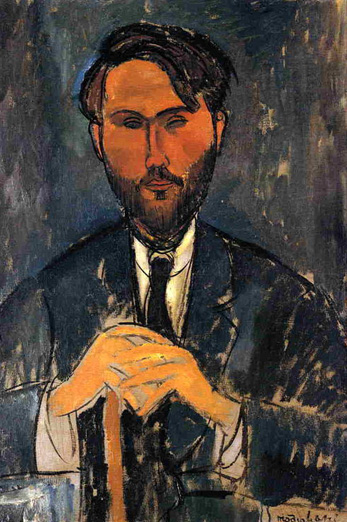

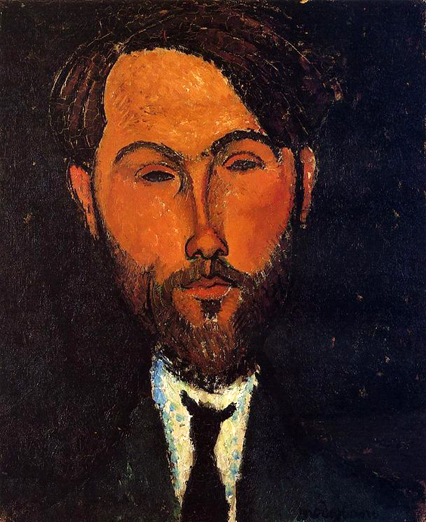

Portrait of Leopold Zborowski

Polish Poet and Art Dealer Leopold Zborovski: 1918

Leopold Zborowski

Leopold Zborowski with Cane

Portrait of Leopold Zborowski

Leopold Zborowski (1889-1932) was a Polish poet, writer and art dealer.

Zborowski and his wife Anna (Hanka Zborowska) were contemporaries with Parisian artists such as Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Paul Cézanne, André Derain and Amedeo Modigliani, who painted their portraits.

Léopold Zborowski was Amedeo Modigliani's primary art dealer and friend during the artist's final years, organizing his expositions and letting the Leghorn artist use his house as an atelier. He also was the first art dealer of René Iché, Chaim Soutine, Maurice Utrillo, Marc Chagall and André Derain. There are several portraits of him by Modigliani. Zborowski highly benefited of the celebrity after Modigliani, accumulating a fortune which he though lost during the 1929's economic crisis, dying poor in 1931.

Portrait of Anna Zborovska: 1917

Madame Zborowska on a Sofa: 1917

Anna (Hanka) Zabrowska

_Zabrowska.jpg)

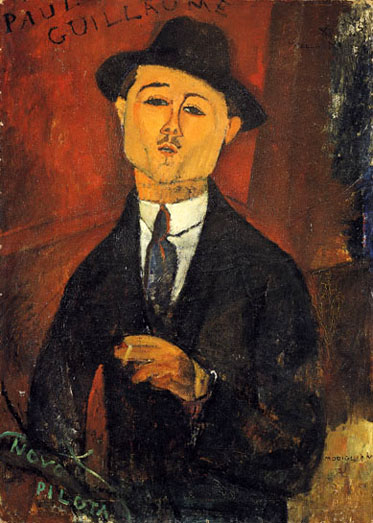

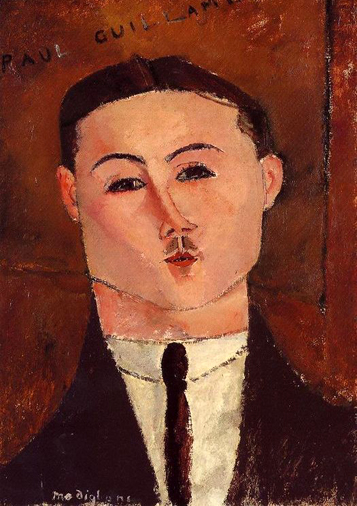

Paul Guillaume, Novo Pilota: 1915

Paul Guillaume was twenty-three when Modigliani painted this portrait. Already an established dealer in l'art négre, Guillaume is presented as the 'new helmsman' and defender of contemporary art. His name boldly appears at upper left; at upper right the Star of David is accompanied by the inscription 'Stella Maris'; 'Novo Pilota' is painted with a flourish at lower left. Modigliani signed the painting at lower right, adding a 'swastika' which, prior to its later negative association, was recognized as a Sanskrit symbol meaning 'good omen'.

The Russian sculptor Ossip Zadkine, a friend of Modigliani, gave an account of one of Guillaume's sittings for the artist: 'Zborowski took Modi to the home of Paul Guillaume, a young art dealer, rather plump and flabby, who exhibited not only cubist paintings but also African sculptures as yet unfamiliar to the general public, of the sort I had noticed some years earlier in the British Museum, with ethnographic labels. Paul Guillaume agreed to have his portrait done by Modigliani. All the sittings and painting sessions took place in a cellar lit by strong electric light and with a liter of wine on the table'.

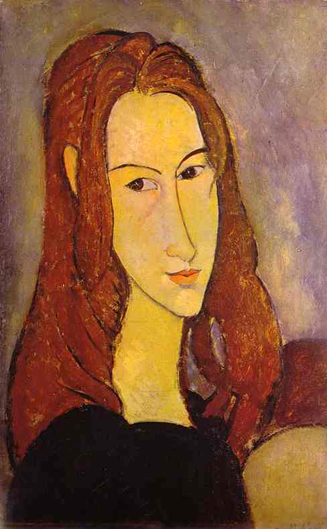

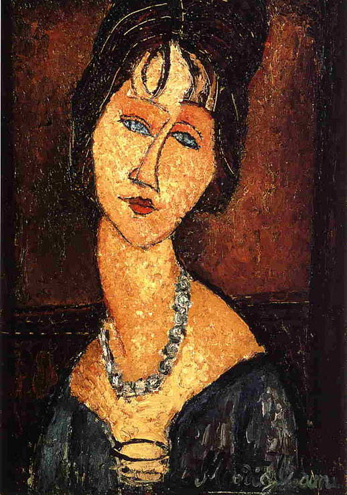

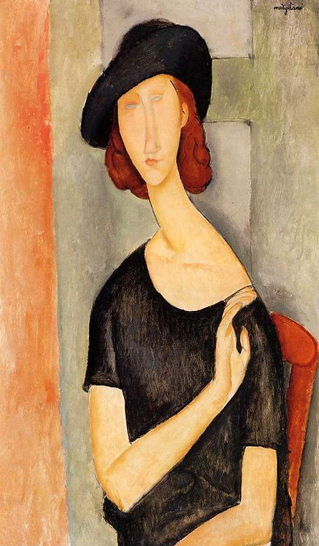

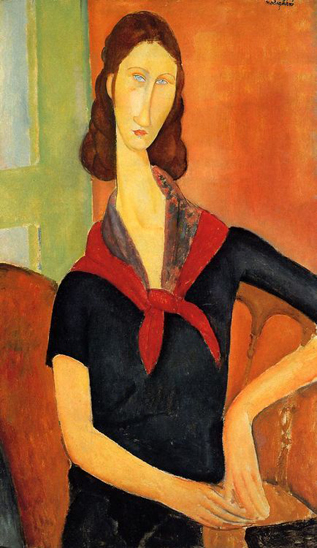

Jeanne Hébuterne

The following summer, the Russian sculptor Chana Orloff introduced him to a beautiful 19-year-old art student named Jeanne Hébuterne who had posed for Tsuguharu Foujita. From a conservative bourgeois background, Hébuterne was renounced by her devout Roman Catholic family for her liaison with the painter, whom they saw as little more than a debauched derelict, and, worse yet, a Jew. Despite her family's objections, soon they were living together, and although Hébuterne was the current love of his life, their public scenes became more renowned than Modigliani's individual drunken exhibitions.

Jeanne Hebuterne in Profile: 1918

Jeanne Hebuterne in Profile: 1918

Jeanne Hebuterne, Common Law Wife of Amedeo Modigliani: 1918

Jeanne Hebuterne, Common Law Wife of Amedeo Modigliani: 1918-19

Portrait of the Artist's Wife, Jeanne Hebuterne: 1918

Amedeo Modigliani, born into a wealthy family in Italy, was stricken with illness early on in life. He managed to move to Paris by 1906 and often visited Picasso's studio, but instead of being drawn into the Cubist aesthetic, took his artistic cues from early European medieval art as well as the art of several non-Western cultures. From these he drew on the stylized, linear simplifications that would characterize his nudes and his portraits. This is one of the latest depictions of his wife (1898-1920), whose soft features and quiet gaze are not easily distinguishable from the dozens of other three-quarter and bust-height portraits he completed. Stricken with tuberculosis and prone to abusing alcohol and drugs, Modigliani died at age 36, less than two years after this portrait was completed. Grieving, Jeanne killed herself two days later. She was pregnant with their second child.

Jeanne Hebuterne, Common Law Wife of Amedeo Modigliani: 1918

Jeanne Hebuterne, Common Law Wife of Amedeo Modigliani: 1919

Jeanne Hebuterne, Common Law Wife of Amedeo Modigliani: 1919

Jeanne Hebuterne, Common Law Wife of Amedeo Modigliani: 1919

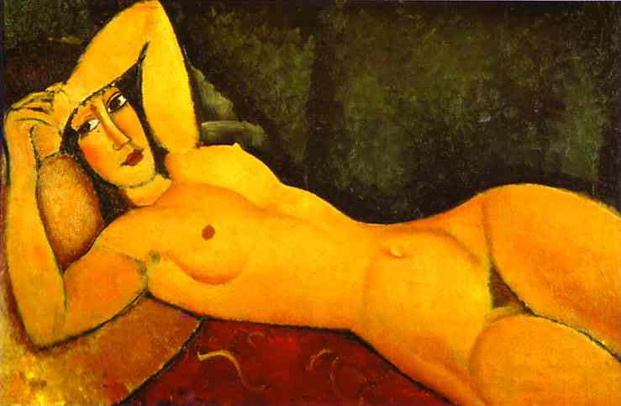

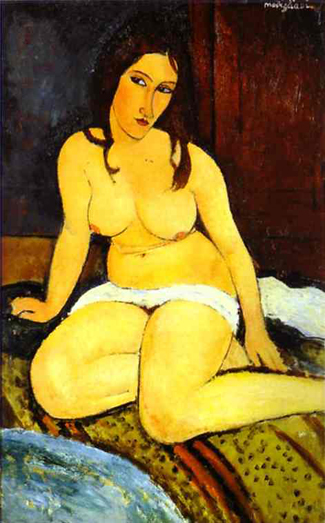

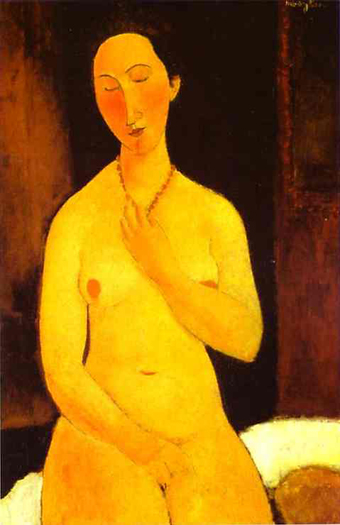

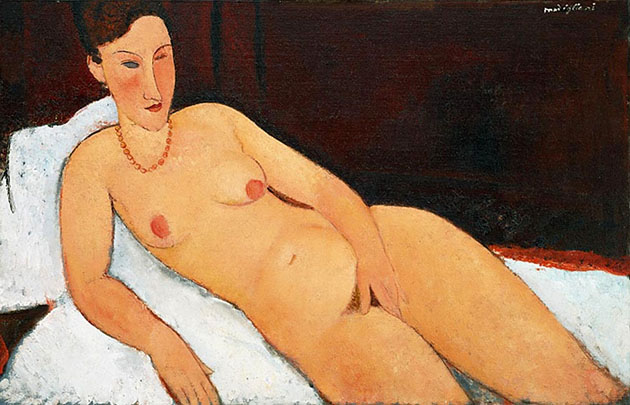

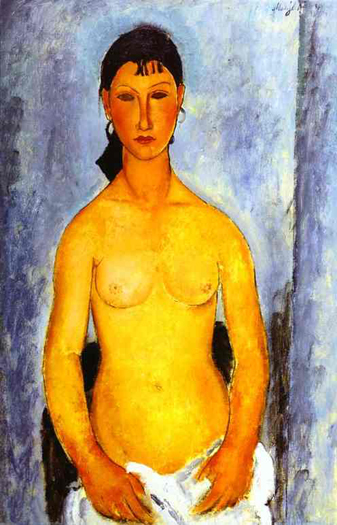

On December 3, 1917, Modigliani's first one-man exhibition opened at the Berthe Weill Gallery. The chief of the Paris police was scandalized by Modigliani's nudes and forced him to close the exhibition within a few hours after its opening.

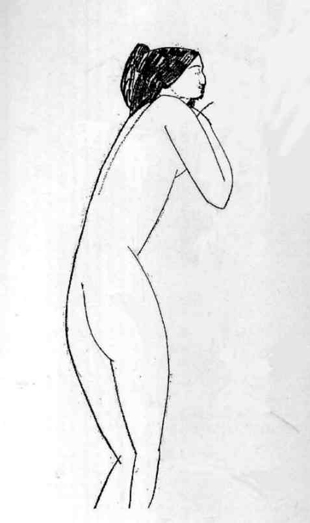

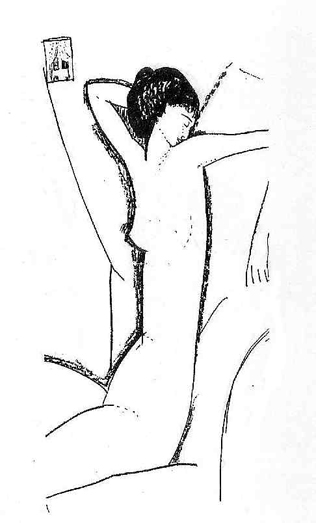

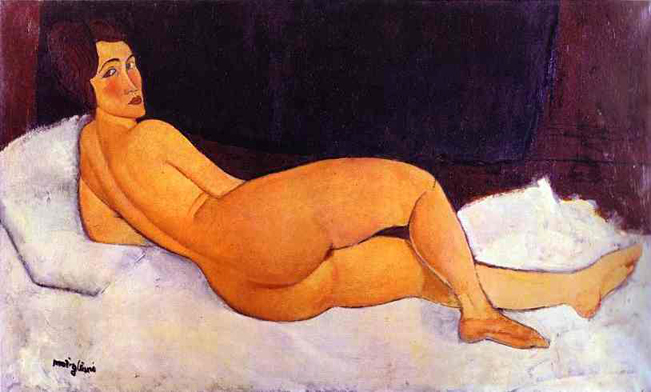

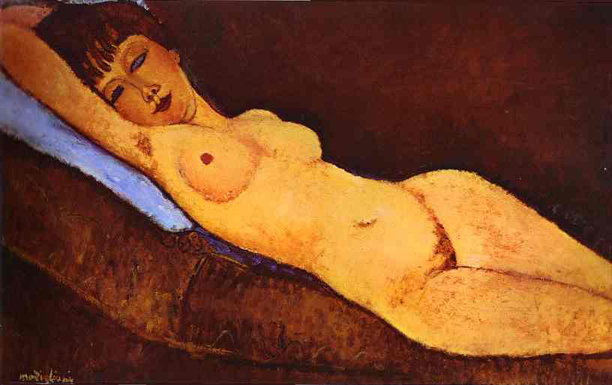

Modigliani painted very few commissioned portraits. They were means to satisfy his rage for people, including people quite different in nature, such as young, un-awakened beings, children, often blond and blue-eyed. He put upon them all the stamp of his own delicate lineaments and his own melancholy, so that the result is unmistakably his. This rapacious desire to possess the human being is given its highest expression in his female nudes. Never before Modigliani was the woman's readiness for love so palpably represented in her accentuated and stretched out nakedness - it has been contrasted to the reserved discretion of Manet's Olympia; thus it is hardly to be wondered at that, at the first exhibition in 1917 at the Galerie Berthe Weill, which his friend Zborowski had organized for him, it had to be withdrawn.

And yet these nudes are the culminating synthesis of the art of Modigliani, combining the formal clarity of the sculptor of the caryatids, the simplified tense line of the unsurpassed draftsman and the bold chromatic effects of the painter with his blooming flesh tints on a dark-red ground and the red-striped coverlet.

Modigliani, who died in 1920 at thirty-five, had squandered himself and yet found fulfillment.

Venus: 1917

(Nu debout, nu medicis)

.jpg)

Nu couche de dos: 1917

Nude Looking over her Right Shoulder: 1917

Nude on a Blue Cushion: 1917

Nude with Necklace: 1917

Reclining Nude: 1917

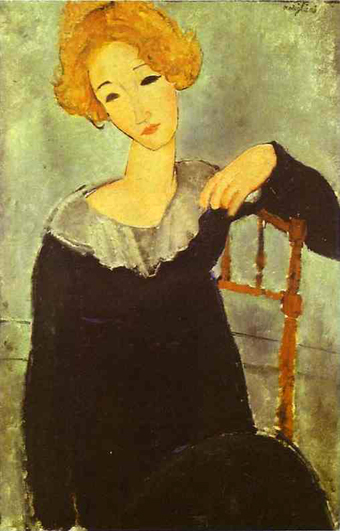

The artist is best known for the works created in Paris between 1915 and 1919-portraits, in which a few telling details achieve a striking likeness, and nudes. His celebrated series of nude reclining women, begun in 1916, continues the tradition of depictions of Venuses from the Renaissance to the nineteenth century, but with one significant difference: the eroticism of the earlier figures is always couched in a mythological or anecdotal context, whereas Modigliani dispenses with this pretext. Consequently, his women appear unabashedly frank and provocative. The two dozen or so figures in the series-never his mistresses or friends but always professional models-lie on a dark bed cover that accentuates the glow of their skin; they are seen close-up and usually from above. Their stylized bodies span the entire width of the canvas, and their hands and feet often remain outside the picture frame. Sometimes asleep, they most often face the viewer, as does this gracefully built model in one of the artist's most famous paintings of the series.

Reclining Nude with Blue Cushion: 1917

Reclining Nude with Left Arm Resting on Forehead: 1917

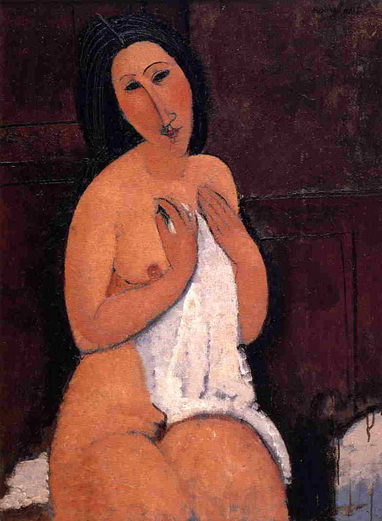

Seated Nude: 1917

Seated Nude: 1917

Seated Nude on Divan: 1917

Seated Nude with Necklace: 1917

Sleeping Nude with Arms Open

(Red Nude): 1917

_1917.jpg)

Nude with Coral Necklace: 1917

Nude with Coral Necklace, 1917

Among Modigliani's most powerful compositions are the more than two dozen female nudes he painted between 1916 and 1919. The artist's distinctive grace and sensuality of line, and fluid elongation and abstraction of form, are here juxtaposed with realistic details that emphasize the eroticism of his subject. The figure is displayed boldly, without extraneous props or accessories to create a narrative or historical context.

Between 1916 and 1919, Modigliani produced twenty-six paintings of female nudes, arranged in both seated and reclining poses. There is considerable difficulty in establishing a sequence or chronology for these works, as various styles and techniques coexisted and overlapped during these last years of the artist's life. More than half of the nudes appear to date from 1917; the back of the Oberlin canvas is inscribed: "Modigliani./ Joseph Bara./ Paris./ 1917". During the winter of 1916-17, Modigliani's patron and dealer, Léopold Zborowski, moved to an apartment at 3 rue Joseph Bara; there he offered the artist living and working space, furnished materials and models, and paid him about 300 francs a month for his entire output.

Two other paintings from 1917 feature the same unknown model, who was undoubtedly hired by Zborowski to pose for the artist: the vertical Seated Nude with Necklace (Nu assis au collier), current location unknown; and the reclining Nude in the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. The Guggenheim and Oberlin paintings are especially close in their shared debt to Titian's female nudes. While the former reflects the Giorgionesque Sleeping Venus in Dresden (ca. 1508), the pose and diagonal placement of the figure in Nude with Coral Necklace, as well as the relationship between figure and viewer, recall Titian's resplendent Venus of Urbino (1538).

Despite such glancing historical references, however, Modigliani's nudes consciously renounce Western traditions of representing the female nude. Avoiding any of the mediating conventions of history, mythology, or anecdote embodied in localizing details of props or setting, Modigliani presents his languorously outstretched figures boldly, with only the barest suggestion of a "setting": a cushion, an expanse of cloth. The figures themselves are open and straightforward, rather than coy or provocative; detached studies of the objective beauty of the female body. Modigliani's uniformly dense, rough application of paint--particularly evident in the Oberlin work--is far removed from the sensual and tactile re-creation of flesh that characterizes traditional depictions of the female nude. In the majority of Modigliani's compositions, moreover (portraits as well as nudes), contact or exchange with the viewer is blunted by a masklike stylization of the face and blank, inwardly focused eyes; in the Oberlin painting, for example, one eye is shut and the other rendered opaque and pupil-less. The absence of setting, the figural distortions, and the focus on surface rather than illusion, combine to distance the nude figure from the viewer, tempering the blatant eroticism of the subject.

Indeed, the impact of Modigliani's nudes is based largely on his fine balance of the erotic and aesthetic: his figures are voluptuous but not indecent; sensual and individual, but also generalized. Figural distortions, such as the characteristic attenuation of the neck or torso, create a grand, precise rhythm and a harmony of elongated oval forms. The pure aesthetic contemplation of this simple, flowing abstraction of form is interrupted, however, by jarringly specific reminders of the real (a nipple, pubic hair, teeth) that insistently reiterate the erotic sensuality of the figure.

In fact, it was this reductive focus on the nude female body, hovering midway between realism and abstraction, that was deemed so shocking by contemporary viewers. In December 1917, Modigliani's first (and only) one-man show, organized by his dealer Zborowski at the Galerie Berthe Weill in Paris, was closed by the police because the nudes exhibited there were found to be obscene. Four paintings of nudes were in the exhibition; it is not known if the Oberlin Nude with Coral Necklace was among them, although it seems quite likely, as the painting was owned by Zborowski at that time.

After he and Hébuterne moved to Nice, she became pregnant and on November 29, 1918 gave birth to a daughter whom they named Jeanne (1918-1984).

Jeaune fille au corsage a pois: 1919

On a trip to Nice which had been conceived and organized by Leopold Zborovski, Modigliani, Foujita and other artists tried to sell their works to rich tourists. Modigliani managed to sell a few pictures but only for a few francs each. Despite this, during this time he produced most of the paintings that later became his most popular and valued works.

During his lifetime he sold a number of his works, but never for any great amount of money. What funds he did receive soon vanished for his habits.

In May 1919 he returned to Paris, where, with Hébuterne and their daughter, he rented an apartment in the rue de la Grande Chaumière. While there, both Jeanne Hébuterne and Amedeo Modigliani painted portraits of each other, and of themselves.

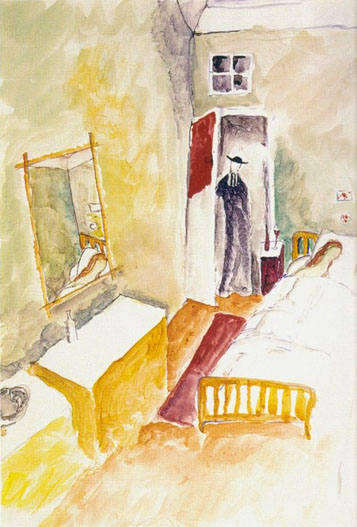

Modi by Jeanne Hebuterne

Self-Portrait: 1919

Although he continued to paint, Modigliani's health was deteriorating rapidly, and his alcohol-induced blackouts became more frequent.

In 1920, after not hearing from him for several days, his downstairs neighbor checked on the family and found Modigliani in bed delirious and holding onto Hébuterne who was nearly nine months pregnant. They summoned a doctor, but little could be done because Modigliani was dying of the then-incurable disease tubercular meningitis.

Modigliani died on January 24, 1920. There was an enormous funeral, attended by many from the artistic communities in Montmartre and Montparnasse.

Hébuterne was taken to her parents' home, where, inconsolable, she threw herself out of a fifth-floor window two days after Modigliani's death, killing herself and her unborn child. Modigliani was interred in Père Lachaise Cemetery. Hébuterne was buried at the Cimetière de Bagneux near Paris, and it was not until 1930 that her embittered family allowed her body to be moved to rest beside Modigliani. A single tombstone honors them both. His epitaph reads: "Struck down by Death at the moment of glory". Hers reads: "Devoted companion to the extreme sacrifice".

Modigliani died penniless and destitute-managing only one solo exhibition in his life and giving his work away in exchange for meals in restaurants. Since his death his reputation has soared. Nine novels, a play, a documentary and three feature films have been devoted to his life.

Source: Wikipedia

Various Paintings of Amedeo Modigliani

There is no thematic or chronological order in their presentation.

A Blond Woman (Portrait of Germaine Survage): 1918

_1918.jpg)

Germaine Survage, wife of Léopold Survage (1879-1968), Finish-born painter of Russian descent, Modigliani’s friend, who let him use his studio in 1818.

Adrienne

(Woman with Bangs): 1917

_1917_Two.jpg)

Antonia: 1915

Cafe Singer: 1917

Girl in a Green Blouse: 1917

Girl in a White Chemise: 1918

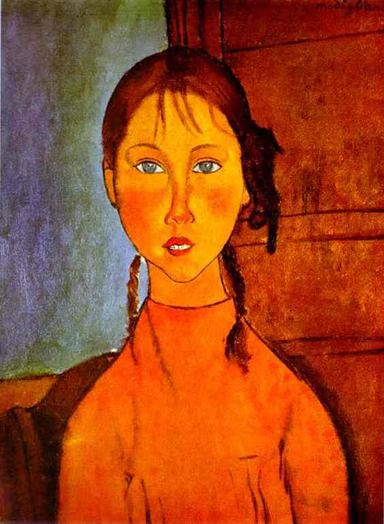

Girl with Braids: 1918

Gypsy Woman with Child: 1919

La Belle Epiciere: 1918

Lalotte: 1916

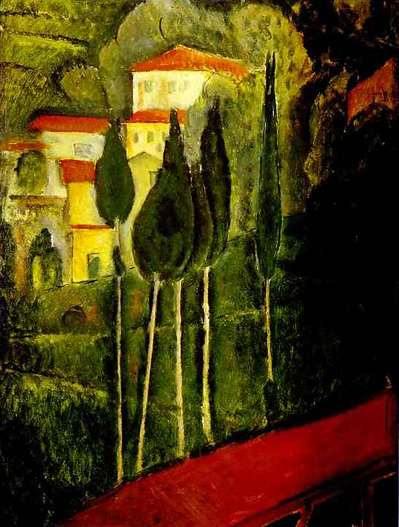

Landscape: 1919

Little Girl in Blue: 1918

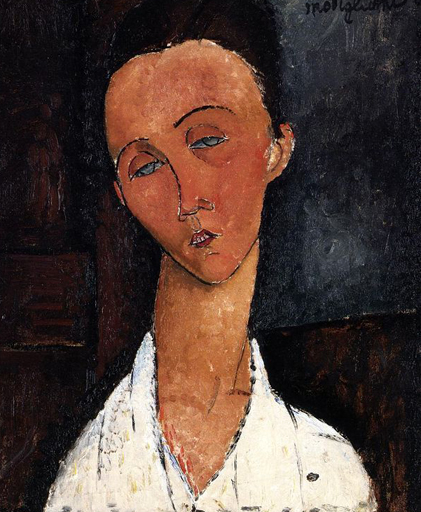

Lunia Czechovska: 1919

Lunia Czechowska: 1919

Lunia Czechowska

Lunia Czechowska

Man with Pipe

(The Notary of Nice): 1918

_1918.jpg)

Marcelle: 1917

Monsieur Deleu: 1916

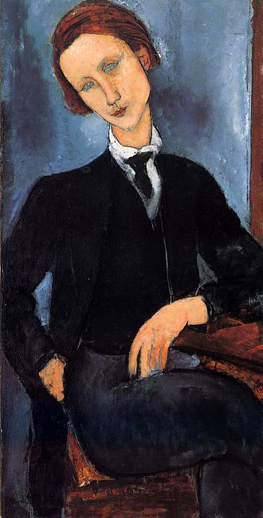

Monsieur Lepoutre: 1916

Pierrot: 1915

Portrait of a Girl (Victoria): ca 1917

_ca_1917.jpg)

Portrait of a Girl: 1917-18

Portrait of Chaim Soutine Seated at a Table: 1917

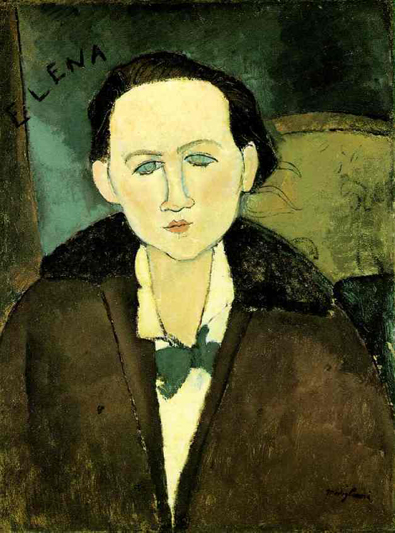

Portrait of Elena Pavlowski: 1917

Portrait of Leon Bakst: 1917

Portrait of Madame Kisling: ca 1917

Portrait of Paul Alexandre Against a Green Background: 1909

Portrait of Pedro: 1909

Portrait of the Art Dealer Paul Guillaume: 1916

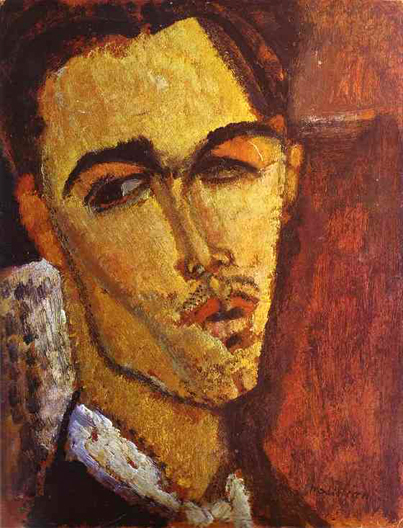

Portrait of the Spanish Painter Celso Lagar: 1915

Celso Lagar (1891-1966) entered the history of art of the 19th century as a painter of circus, though his life and work was much more than this. First of all and above all, Lagar represents well a social consideration of a contemporary artist, that is, someone who, after initial studying in historical vanguards of Paris, looks for an authentic way of expressing himself with a series of personal themes, easily identifiable among his contemporaries. But besides, Celso Lagar is an introverted Bohemian, a depressive person and absolutely dependent on his companion, Hortense Begué, a sculpturer with whom he will share his life since he knew her, in 1912, until her death in 1956. In case of Lagar we meet an "execrated painter" and that precisely gives him all the requirements for the triumph in a period like the current, marked by the "revival". Thus, the public opinion about Lagar has improved considerably in the last years, that coincided with the centenary of his birth, when he has been rediscovered by the public in a number of anthological exhibitions.

Life and work of Celso Lagar can be divided in four stages distinctly separated by the historical events (the two World Wide Wars). Both wars had a powerful influence on Lagar's life but not on his obvious artistic approaches, regarding his artistic consolidation after the First World War, on his own thematic (landscapes, taverns and, especially, the circus scenes) and a series of constant influences (Goya, Cezanne ...).

The first of his stages was that of apprenticeship, that lasted until he left Paris when the First World War started. Perhaps influenced by his father's work (Gumersindo Lagar was a cabinetmaker) he began his education in the field of sculpture. From his natal Ciudad Rodrigo, he went to Madrid to join a workshop of one of the best sculptors of the time, Michael Blay. Blay himself advised Lagar to go to Paris to continue his learning, just when the French capital was the centre of the artistic world. As a good disciple, Lagar will go to Paris though before, during 1910 and 1911, he visited Barcelona, where, he began a series of contacts that will become very helpful later

In March of 1911, Lagar arrived to Paris where he made a number of sculptures most of which are nowadays lost. Throughout these years he will get to know Hortense Begué, his companion for the rest of his life, and the distinguished sculptor Joseph Bernard and Amedeo Modigliani with whom he established a brief but intense friendship that influenced him strongly during that period. This will be the time when, gradually, he left sculpture in favor of painting as it was stated on his return from Paris after the First World War.

The outbreak of the First World War meant the beginning of the second stage in Celso Lagar's life and work. He will go to Barcelona where he will remain during the war and, taking advantage of the contacts of his previous stay. He organized a number of exhibitions that already had a clear pre-eminence of his work as a painter and that were useful for achieving certain recognition in Cataluña and, finally, a presentation letter for his return to Paris.

Celso Lagar will return to France in 1919 to settle there definitively. Until the beginning of the Second World War we observe the prime of his career of an artist. During this period, Lagar exposes his works in the best Parisian galleries, his work is constant and abundant, his style becomes peculiar and he entirely devotes himself to the painting. During his residence in Paris as well as during his stays in Normandy, from 1928, he will create works on very specific themes: taverns, Spanish reminiscences, landscapes and his eulogized scenes of the circus. Having already passed the period of ultramodern influences of all kinds (cubism, fauvism, etc.), Celso Lagar will find his own way marked mainly by the inspiration provided by works of Goya and Picasso. Gradually his palette becomes colder but the themes stay the same. The recognition of the critics and the public increases.

The outbreak of the Second World War will be the beginning of the end of the Lagar's golden epoch. He was obliged to emigrate from Paris due to the Nazi occupation. Lagar and Hortense sheltered in the French Pyrenees in very rough conditions that could affect the psychological balance of the artist. Their return after the liberation of Paris, though was not a failure, did not have as many repercussions as the author believed. His time had passed. Lagar will continue his artistic path using the same topics and the same technique but the collectors were already looking for new contents and manners. Though the exhibitions continue, they are not in the best galleries now and the sales decrease. Little by little, the success fades away and the economic penuries affect the couple that is obliged to borrow money from their friends. This was the time when the last period in Celso Lagar's life began. When on 30 January, 1956 Hortense got into the hospital Broca, Lagar fell down in a deep depression that later brought him to the Sainte Anne's psychiatric asylum and put an end to his work as an artist. Those were difficult years, years of deep depression, that he will not overcome until the end of his days despite the work on recovery of his creations initiated by a gallery owner, Crane Kalman, a true rediscoverer of Celso Lagar's art in the second half of the 19th century. Though he did not paint anymore, there were organized, by judicial order, two auctions of the works that remained in his workshop to pay his stay in the asylum until October, 1964, when he returned to Spain to live in Seville with his sister until his death on 6 September, 1966.

Reclining Nude

(Le Grande Nu): ca 1919

_ca_1919.jpg)

His brash colors and large graphic shapes filled with texture add to the appeal, making a fascinating visual soup of lines, colors and forms. Modigliani's figures lean and twist, their geometry askew as though gravity has shifted to an angle off of perpendicular. His faces are sometimes perched atop elongated necks, as if striving to be taller, and are often tilted to one side in some quizzical inflection.

His geometrically distilled portraits and languorous nudes project a warmth and humanity that is often lacking in the work of many of the other modern painters, who seemed to be striving to remove those characteristics from their angular collisions of shapes and colors.

Modigliani's charms were wasted on the art patrons of the time, even those interested in the other emerging modern painters. His work became very popular years after it was too late to do anyone but the gallery owners any good.

Sadly, Modigliani lived the tragic, falsely romanticized life of the "starving artist". So charming and romantic was this lifestyle that the desperation and shame of his poverty, along with bouts of chronic illness, drove him to be consumed by drink and drugs in addition to the tuberculosis that cut short his life in 1920 at the age of 35.

Seated Nude

Seated Nude with Shift

Red-Haired Young Woman in Chemise: 1918

Renee the Blonde: 1916

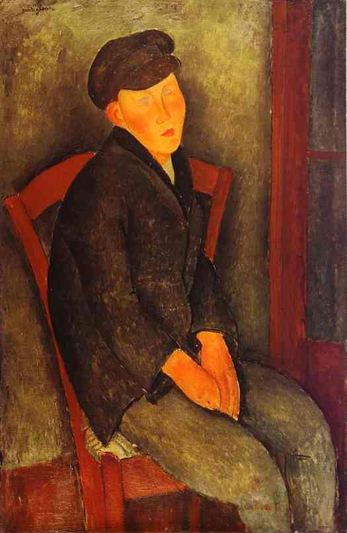

Seated Boy with Cap: 1918

Seated Nude: 1916

Standing Nude Elvira: 1918

Standing Nude: 1911-12

Seated Woman with Child: 1919

Study for Portrait of Frank Haviland: 1914

The Little Peasant: ca 1918

The Sculptor Jacques Lipchitz and his Wife Berthe Lipchitz: 1916

The Servant Girl: ca 1918

This is a portrait of someone whose name we do not know. But we can still figure out some things about her from the painting. How old do you think she is? Try and think of words that describe the kind of person you think she was (for example, loud, quiet, fun, boring, happy, sad, etc.). Stand in the pose she takes in the portrait. How do you feel? Does that give you any other ideas about what type of person she was?

Amedeo Modigliani, the artist who painted this girl, tells us in the title that she is a servant. She would have worked in someone's house, and might have cooked, cleaned, done the laundry, or served meals. Her eyes are blank, taking away any kind of personality she might have had. She was expected to be quiet unless someone spoke to her first. Her head is slightly tilted, and she stands in a corner so she will not be in the way, with her hands folded in front of her as if she is waiting for an order to be given. What else about her might let you know that she's a servant?

With paintings like this, you can use your imagination! What time of day do you think it is? Is she just starting her daily chores or is she almost finished? Which room of the house is she in, and why do you think so? Is there anyone else in the room with her? Give her a name.

The Young Apprentice: 1918

The Zouave: 1918

Young Girl: 1918

Almaisa

Andre Rouveyre

Beggar Woman

Chaim Soutine

Constant Leopold

Count Weilhorski

Jean Alexandre

Joseph Levi

Landscape

Leon Indenbaum

Little Girl in Black Apron

Little Servant Girl

Louise

Madame Dorival

Madame Georges van Muyden

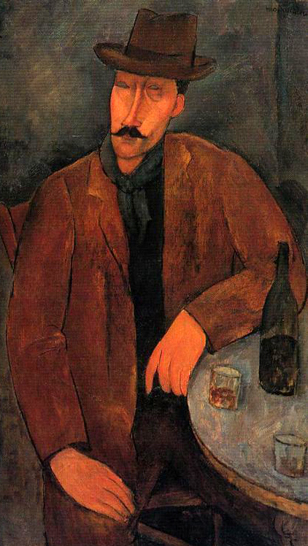

Man with a Glass of Wine

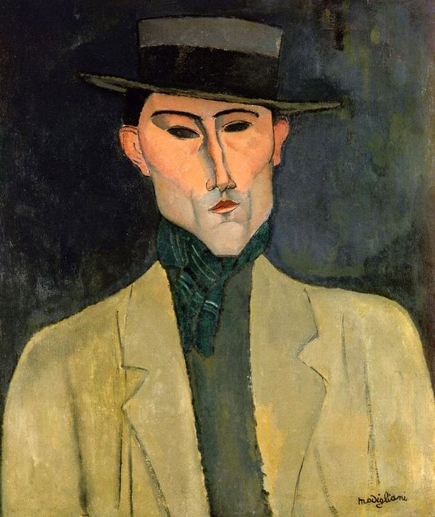

Man with Hat

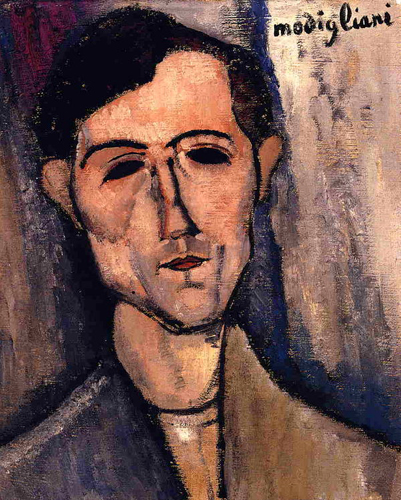

Man's Head

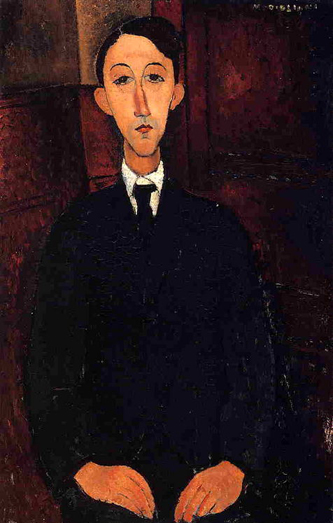

Manuel Humberg Esteve

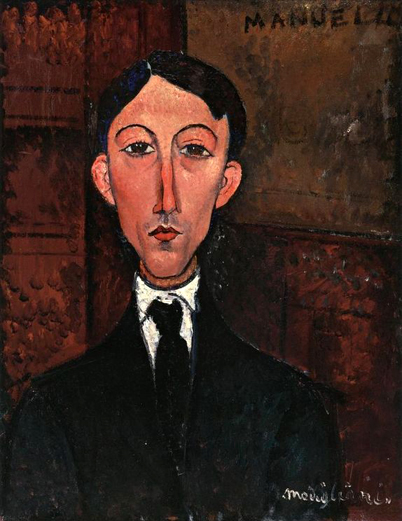

Manuel Humbert

Paul Guillaume

Pierre-Edouard Baranowski

Portrait of a Student (L' Etudiant): ca 1918-19

_ca_1918_19.jpg)

Portrait of a Woman: ca 1917-19

Portrait of a Woman: ca 1917-1918

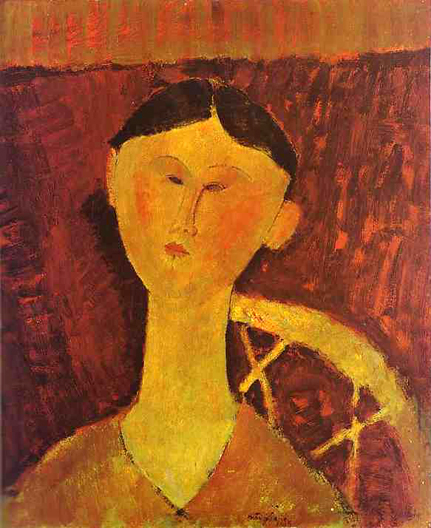

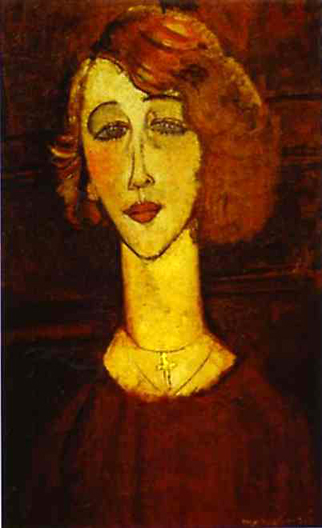

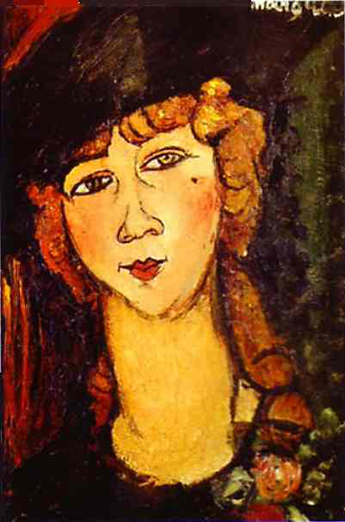

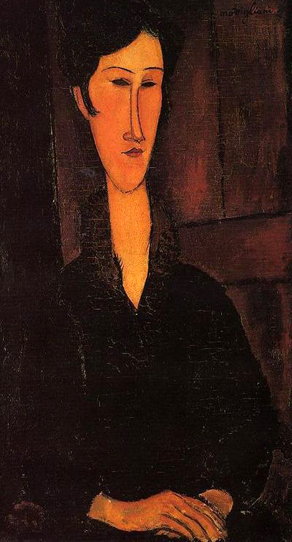

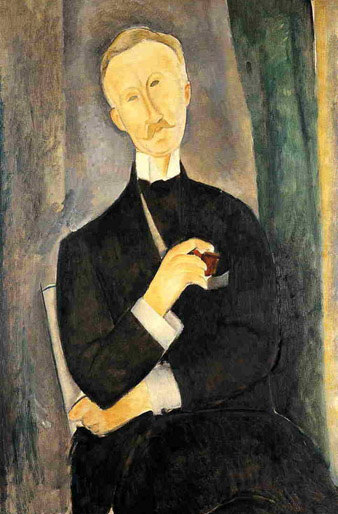

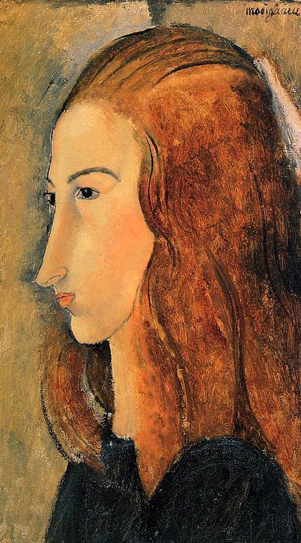

Modigliani studied briefly in Florence and Venice before moving to Paris in 1906. His portraits chronicle the lives of fellow artists and poets, although the woman in this painting remains unidentified. Influenced by African masks and Cubism, he rendered her features as flat, geometric planes. The gracefully elongated neck and nose may also derive from the Renaissance paintings of Sandro Botticelli and Parmigianino, thereby elegantly merging Western and non-Western, modern and traditional styles.

Portrait of a Woman in a Black Tie

Portrait of a Young Woman, seated: 1911-12

Portrait of an Unknown Model

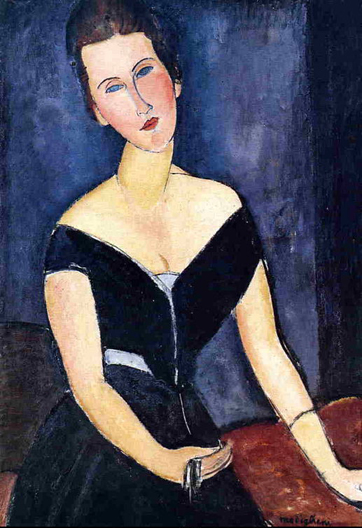

Stylized, bust-length, front view of young woman with auburn, shoulder-length hair, blue eyes, wearing a black v-neck top and seated on a chair against plain blue/green background with yellow strip on the right.

Portrait of Dr. Paul Alexandre

Portrait of Henri Laurens

Portrait of Madame Zborowska

Portrait of Morgan Russell

Portrait of Pinchus Kremenge

Portrait of the Artist Leopold Survage: 1918

Portrait of the Photographer Dilewski

Readhead Wearing a Pendant

Roger Dutilleul

The Beautiful Confectioner

The Beggar of Leghorn

The Black Dress

The Blue Blouse

The Boy: 1919

Utilizing the expressive potential of the human face and figure in a highly individual way, Modigliani painted the colorful personalities of Parisian art circles, using elongated forms and shallow interior spaces.

In 1918 the artist's doctor arranged for him to move to southern France to improve his failing health. There Modigliani painted portraits of unnamed young workers. This boy, with his solemn, introspective expression, is one of the finest of this era. The mask-like face and blank eyes are a translation of forms found in African and Archaic Greek sculpture.

The Pretty Housewife

Thora Klinckowstrom

Woman in White Coat

Woman of Algiers

Woman with a Necklace: 1917

Woman with Blue Eyes

Young Girl Seated

Even through the dysfuction that alcohol and drugs can inflict upon individuals and family, there is a trajedy of unfulfilled possibilities in the story of Amedeo Modigliani and Jeanne Hébuterne. It is a story that ought not to have happened when family and friends are present in our lives, but I suppose the difficult question is, even if we are well intentioned, what is the consequence when we turn a blind eye on suffering that is clear and apparent. The following essay though a bit repetitive provides further insight to a tragedy that I wished didn't seem to be unending

Senex Magister

Missing Person in Montparnasse: The Case of Jeanne Hébuterne

(excerpts)

by Linda Lappin

Jeanne Hebuterne

Jeanne Hebuterne with Hat and Necklace

An elusive figure inhabits the sundrenched rooms of Modigliani's Montparnasse studio in Rue de la Grande Chaumière. She sits quietly in a corner sketching, paces the corridor with a heavy step, waits at the window, looking down at skeletal trees in an empty courtyard. From Modigliani's many portraits of her, we recognize the otherworldly gaze, the coppery hair coiled like a geisha's, the unflattering hint of double chin: It is Jeanne Hébuterne, Modigliani's last mistress, only friend, and the mother of his daughter, Jeanne Modigliani.

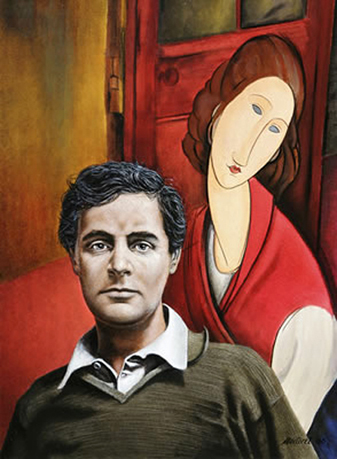

Amedeo Clemente Modigliani in his Studio

Until October 2000, when her art work was featured at a major Modigliani exhibition in Venice at the Fondazione Giorgio Cini, not much was known about Jeanne Hébuterne, except for the tragic story of her suicide in 1920. She was a promising young artist, fourteen years Modigliani's junior. She came from a conservative bourgeois background and was renounced by her family, devout Catholics, for her liaison with the painter, who in their eyes was nothing but a debauched derelict, and Jewish besides. Much too early in their love affair, Jeanne became pregnant with their first child. She was approaching the end of her second pregnancy when, destitute, abandoned by all but Jeanne, Modigliani died of tubercular meningitis on January 24, 1920.

Unable to face life without him, she walked backwards out a Paris window twenty-four hours later, and at the age of twenty-one, exited a world she had but little known.

Eighty years of silence have passed since Jeanne Hébuterne's last act of protest. Upon her death, her daughter of fourteen months was whisked away to Italy where she was adopted by Modigliani's sister, Margherita, who refused to recognize her brother's stature as an artist, or to condone his illicit relationship with Jeanne. In the years that followed, Jeanne Hébuterne's papers were scattered, her artworks and possessions secretly guarded by her brother, the painter André Hébuterne. Surviving family members and friends would not collaborate with the biographers and scholars who later attempted to piece together the facts of Jeanne's relationship with Modigliani and to define her place in Montparnasse.

Portrait of Marguerite

Throughout her youth, Hébuterne's daughter, Jeanne Modigliani, herself an artist, was kept in the dark about her parents. Rejecting both Margherita's moralistic view of Modigliani and the Montparnasse myth depicting her father as a peintre maudit and genial drunk, Jeanne Modigliani undertook a quest to discover her own history and published the findings of her research in 1958 in Modigliani senza leggenda. Some details of this account were corrected in a revised version reissued in 1984 for the centennial of Modigliani's birth.

Yet this was not the final version of the facts, or rather her final interpretation of patchy evidence gleaned over a lifetime. Prior to her death in 1984, Jeanne Modigliani worked closely with the art historian Christian Parisot, author of many studies on Modigliani, and dictated further changes to be made in a new, definitive biography written by Parisot, as yet unpublished. Jeanne Modigliani entrusted to Parisot previously unknown materials documenting Modigliani's Life and his relationship with Jeanne Hébuterne, but posed one condition concerning future publication. The true story of Jeanne Hébuterne was to be kept secret until the year 2000.

Meanwhile, in his Montparnasse studio, Jeanne's brother, André Hébuterne, cursed himself for having introduced his sister to the Paris art world, and jealously hoarded all existing artworks she had produced, for he was determined not to have her name tainted by connection with Modigliani's. Her drawings and paintings were hidden away. Christian Parisot learned of their existence in 1970, but it took him thirty years to convince the Hébuterne heirs to allow public access to Jeanne's artwork, which could not be done as long as it was in André's hands. André lived well into his nineties.

Amedeo Modigliani

by Jeanne Hébuterne Modigliani

Self Portrait of Jeanne Hebuterne Modigliani

Composition by Jeanne Hebuterne Modigliani

Natura Morta by Jeanne Hebuterne Modigliani

Morte Jeanne

by Jeanne Hebuterne Modigliani

In October 2000, the last veil was lifted. Parisot brought to Venice an extraordinary exhibition, entitled Modigliani ed i suoi (Modigliani and his circle). The exhibition focused on an extensive network of friends and associates active in Montparnasse at the end of the Belle Epoque. Modigliani's moving portrait of Jeanne, visibly pregnant in her simple shift, was the most well-known painting on display. There were also minor pieces by Picasso, Max Jacob, Léon Bakst, and Rouault. The core of the show consisted in a far more intimate and lesser known group including Jeanne Hébuterne, her brother André, his future father-in-law Georges Dorignac, and Hébuterne's former admirer, Tsuguharu Foujita. Jeanne's works were being shown for the first time ever, and one could only be profoundly moved by the privilege of viewing them, after nearly a century of oblivion.

Although Modigliani's influence on Jeanne's style was undeniable, the works exhibited vindicated Jeanne Hébuterne's identity as an artist in her own right. Some critics will find an anticipation of feminist iconography in her bold nude self-portraits of vivid sexual detail. This treatment of the nude is even more remarkable considering that just a few years earlier in France, women studying in art academies were excluded from life-drawing classes with nude models, as the naked body was not thought to be a proper subject for their contemplation. In keeping with the climate of the times, Jeanne transgressed the dictates of bourgeois propriety through such daring self-portrayal. These drawings also present a conundrum for gender-based interpretation. Modigliani's favorite model portrays herself naked in voluptuous poses, inspired by the classic tradition of the female nude seen through male eyes. In doing so, she achieves a curious androgyny, seizing both roles: artist and model, male and female, subject and object. Clearly her intention was to startle, challenge, and provoke.

Aside from the sixty drawings and half-dozen paintings on display, the photographic documentation collected in the exhibition suggested other areas in which Jeanne experimented: clothing and jewelry design. For Jeanne Hébuterne, as for many other citizens of Montparnasse, life itself was art, and she sought total expression: in her work, in her self-presentation, in the clothes and jewelry she designed for herself, and in the unconventional life she freely chose as Modigliani's partner.

Biographical information concerning Modigliani is drawn from two main sources. The first, not always reliable, consists of memoirs celebrating Montparnasse in this period. In testimonies such as those collected by Lawrence Golding in Artist's Quarter, Modigliani is inevitably drawn as a wild, half-drugged, tormented genius, an incorrigible alcoholic, a prodigious seducer of women, and a naked dancer in the street. Scanty record is given of Jeanne in these sensational hagiographies, for she was not popular in the bohemian circle. Some considered her "too proper" and out of place in Montparnasse: she was bourgeois. From all accounts, Jeanne Hébuterne was a reserved person with few friends, and when in the midst of Modigliani's acquaintances, tended to remain aloof. This gave some the impression that she was extremely passive, or just plain dull, and thus of no interest to anyone.

Artist Jeanne Modigliani,

the Daughter of Amedeo and Jeanne

The second source of information about Modigliani is his daughter's research into her parents' life through documents, letters, photo albums, and reminiscences gathered after overcoming enormous resistance on the part of both the Hébuterne and Modigliani families. In reconstructing Modigliani's life, Christian Parisot tends to discredit the first source, relying primarily on Jeanne Modigliani's findings, but adds a third source, previously inaccessible to Modigliani scholars, Mme. Céline-Georgette Hébuterne, widow of André.

In an interview with Parisot appearing in the catalogue of the Venice Modigliani exhibition, Céline tries to rehabilitate Modigliani, claiming that his addiction to alcohol and the stories of drug use, documented by many sources, were only legends concocted by the envious. Céline, who as a young girl modeled for Modigliani, goes on to suggest that use of drugs and alcohol cannot possibly co-exist with the capacity to create great art. Parisot echoes this in emphasizing Modigliani's poor health and crushing sense of failure, rather than a long history of substance abuse, as the cause of the semi-madness into which he fell at the end of his life. In this picture, all tarnish from Modigliani's image has been removed for posterity.

One biographer who might object to these airbrushed adjustments is the British novelist Patrice Chaplin, who in the eighties unearthed a correspondence between Jeanne and her friend Germaine Labaye, another aspiring young artist. Some of these letters would corroborate the darker side of Modigliani's personality, while portraying Jeanne as a spirited, sensual, and independent woman who may have experienced moments of deep melancholy, but had no regrets about the life she had chosen.

Chaplin published her version of Jeanne's life in Into the Darkness Laughing, which is more a memoir about her own search for Jeanne than a proper biography. While researching in Paris, she also tracked down Céline Hébuterne who consented to a brief phone interview included in Chaplin's book. In no uncertain terms, Céline confirmed reports of Modigliani's alcoholism and added, "The Hébuterne family wanted nothing to do with him." This version of the story blatantly contradicts statements Céline later made to Parisot during an interview, which are recorded in an essay printed in the catalogue of the Venice show.

But this is only one of the many discrepancies you come across in trying to puzzle out the facts of Jeanne's life. Issues still to be clarified are: was Jeanne merely a passing romantic episode for Modigliani or an intimate partner and work associate? Did they ever live together for any length of time? Did the Hébuternes really renounce their daughter and are they to blame for the tragedy? Other ambiguous questions concern the date and place of her suicide, the fate of her body after she fell through the window; and the reason why her artwork was concealed for so long from public knowledge. All this makes Jeanne Hébuterne a missing person framed in an empty window over Montparnasse.

Early biographers, overly solicitous of Jeanne Modigliani's feelings, as she was now an orphan, cast Jeanne Hébuterne in the role of silent saint and sacrificial victim, while ignoring her artistic talents. Such an attitude infuriated her daughter who undertook her search in order to reclaim her maternal legacy as an artist. Other biographers simply stated that Modigliani had no truly deep attachments aside from his mother, Eugenia, that Jeanne was only one of many women, second to his model Lunia, or that he lived only for art.

Lunia Czechowska, Left Hand on her Cheek

Modigliani himself may have contributed to this idea, for he did his best to keep Jeanne Hébuterne out of sight. In the early phase of their courtship, he took her round to the cafés, but after they began to work together, he would leave her at their studio while he went carousing. All this, out of respect, in what Modigliani himself defined to a friend as "the Italian way." In public he treated her quite formally. His other mistresses had not received such genteel treatment. Modigliani had once hoisted his previous lover, Beatrice Hastings, through an unopened window during a knockdown fight.

Sometimes after an evening out for a cheap dinner on credit at a friendly bistro, Modigliani would accompany Jeanne home to her parents, kiss her in the doorway, and send her up while he headed out for a night of serious discussions on art, and, doubtless, serious drinking. Some later criticized Jeanne for not making him give up drink, too tall an order, perhaps, for a twenty-year old girl. Stoically, she stood by him, no matter what. To those few who knew them well, there was no doubt he loved her deeply and that to her, he was a god. In his own way, he was committed to her, for although he fathered children by at least three other women, Jeanne's daughter was the only one he recognized as his own.

If reticence and propriety have kept this woman wreathed in mystery, so has rivalry. Jeanne had an army of rivals in Montparnasse: many women, and also men, were in love with the handsome, passionate, madcap Italian. Modigliani-"Modì" to his friends, "Dedo" to his family, was a small man of sturdy build, mild features and probing eyes. Even in the most temporary living conditions, as when spending the nights on a bench in a square, he was fastidious about his appearance. He was often dressed in a natty brown corduroy suit, a red scarf knotted around his neck. Amedeo Modigliani was no dropout, but a man of breeding and culture with a solid background in the history of Italian painting, which he had studied at the academies of Florence and Venice. Indeed, his work is generally interpreted as a renovation of the classic tradition of the Italian masters rather than a break with it. Cocteau has described him as a true aristocrat of the soul: "He was always proud and rich, when we knew him; rich in the real sense." He had a ringing childlike laugh which, as he grew embittered towards the end, could chill you to the core. When sober, he was a man of great finesse and irresistible charm. Several women later claimed to have been Modigliani's one true love, like Lunia Czechowska, a Polish girl who modeled for some of his better known portraits. Lunia hardly mentions Jeanne in her memoirs, although she insisted her own relationship with Modigliani was purely spiritual and that she was never infatuated with him. Perhaps her pride caused her to make such a statement, as it was clear to all Modigliani had chosen Jeanne Hébuterne to share his life, for better or for worse, and indeed "worse" it turned out to be for both of them.

The tragic story of Jeanne and Amedeo might have been copied from the libretto of a nineteenth-century melodrama, though some of the darker-and even squalid details-the sheets stained with sardine oil while he lay dying, as the only thing they had to eat in the studio were tinned sardines-resist such sentimental treatment, and may be apocryphal. But flashing back to when it began, we cannot but relish the scene.

Paris was in transition from the belle époque to the années folles, which unfolded against the backdrop of the First World War. In 1914, the City of Light was still wild and free despite the curfews, the rationing, the empty hotels, the black-bordered telegrams. Although many artists and intellectuals were called into service, the foreigners remained in Montparnasse, like Picasso and Juan Gris. Modigliani had been declared physically unfit for military service. At first, no one really took the war seriously or believed it could last long. If anything, the war reports whetted the hedonism of those left behind. Long goodbye parties were held in Montparnasse for the men going off to fight and the remaining artists stuck together to keep their spirits up. These were hard times for Modigliani, as he regularly received an allowance from his family in Livorno, but the war held up the postal service from Italy, so he was often without funds. Still, even the poorest managed to scrape by on a few sous. As Cocteau has said, poverty was a luxury in Montparnasse, although by 1914 absinthe was banned, the cafés closed at 8 p. m. and women did not go about the streets at night. Yet, there were parties and readings.

Into this world of café life and make-shift studios Jeanne Hébuterne had come as early as 1913, at the age of fifteen, following her brother André, who had, to his parents' dismay, decided to become a painter. Monsieur Hébuterne worked in the perfume department of the Bon Marché. His wife was a modest housewife and fervent Catholic. They had envisioned quite other lives for their children, but did not oppose either André or Jeanne in their choice of studies. They were convinced Jeanne's wish to become an artist was only an adolescent whim. Jeanne enrolled first at a school of decorative arts, and then at the Colarossi Academy, where she studied life-drawing. This itself was an achievement. Women painters were still an exception, even in Paris. Marie Laurencin and Susan Valadon were two of the artists Jeanne hoped to emulate by studying painting. She may have caught her first glimpse of Modigliani here at the academy, for many painters in Montparnasse attended the life-drawing sessions to have cheap access to models, especially in the winter, for the academy was heated.

After class, she would stop off at the Café de la Rotonde, have a drink and chat with friends, including the dapper Japanese painter Foujita, who was genuinely interested in her work, and with whom she may have had a fleeting affair. Most certainly she noted Modigliani at the Rotonde, where he could frequently be seen drinking with Utrillo or Soutine, discussing art with Picasso and Kisling, or even quarreling with Beatrice Hastings. He would have been hard to miss, with his red scarf and corduroy suit, wandering from table to table "like a fortune teller," says Apollinaire, and sketching portraits for a mere five francs, the equivalent of a taxi fare of medium distance.

Or she could have met him on Boulevard Raspail, where, it has been reported, Modigliani danced daily in front of the statue of Balzac. Or maybe she saw him roaming the streets, his jacket pockets stuffed with pages torn from Lautréamont, reciting Dante or Baudelaire at the top of his voice. Wherever she spotted him, in 1915, Jeanne wrote to Germaine that she had "seen someone around" who was just her type, but they did not meet until 1916, when they were introduced by the Russian sculptor, Chana Orloff, during the artists' carnival.