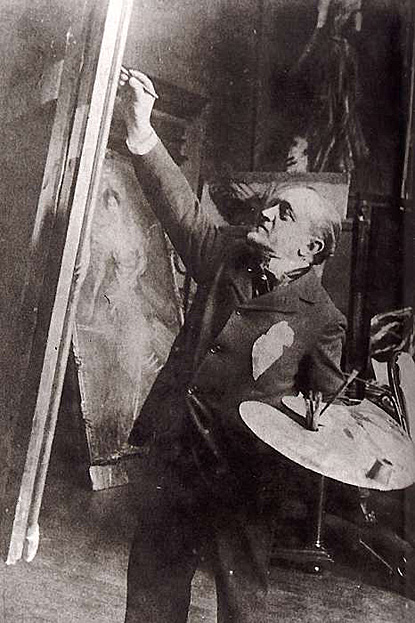

1842 - 1931

Born in Ferrara, Italy on 31st December 1842, Boldini received his initial training from his father, a painter and restorer. A precocious talent, Boldini attended the Accademia di Belle Arti (Academy of Fine Arts) in Florence in 1862. There he met the circle of Tuscan realist painters, known as the Macchiaioli, developing a particularly close friendship with Telemaco Signorini and Christiano Banti. They were a considerable influence on Boldini and introduced him to painting from nature, contemporaneous with the Barbizon painters of France.

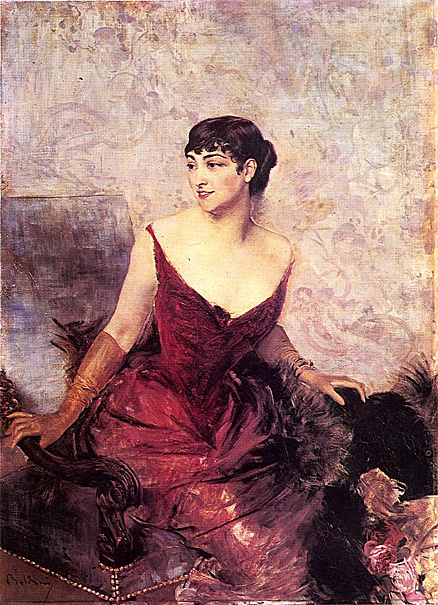

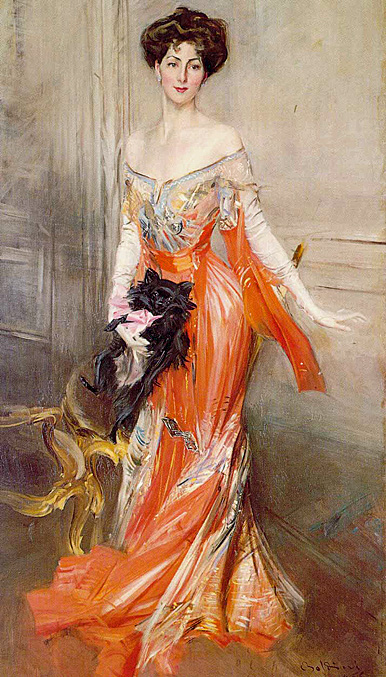

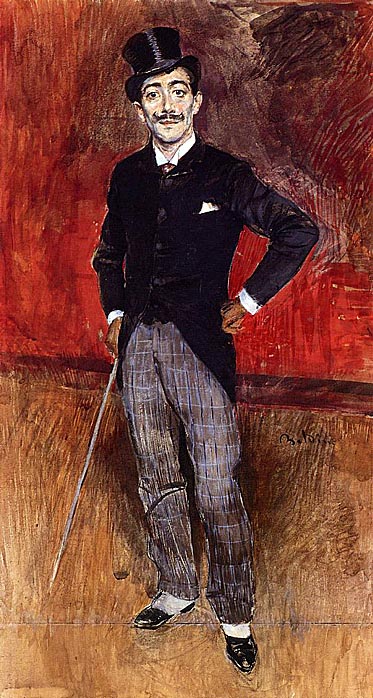

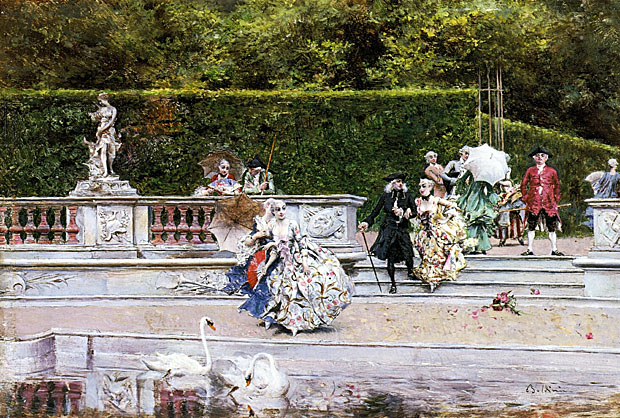

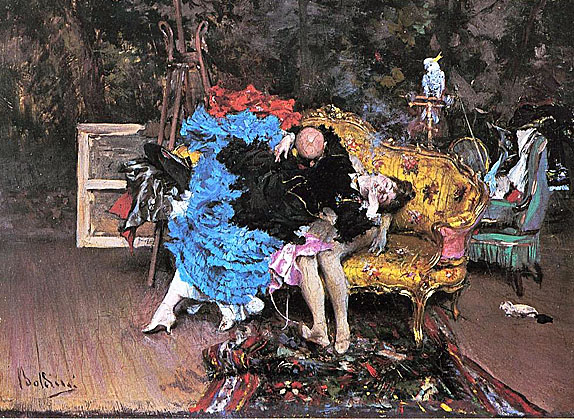

During a visit to Paris for the Exposition Universelle in 1867, Boldini was greatly influenced by the paintings of Courbet, Manet and Degas, artists with whom he later established lifelong friendships. While in Paris, Boldini was captivated by what he considered to be the cultural capital of Europe and moved there permanently in October 1871, settling in the Place Pigalle. During this period he painted a series of small-scale works of eighteenth-century and Empire scenes, commissioned by Adolphe Goupil and other Parisian dealers, but also concentrated on scenes of Parisian life and pictures of elegantly dressed women, many of which were also sold by Goupil. Boldini was accepted as one of the foremost portrait painters of the Belle Epoque in Paris during the 1890's. His unique style set him apart from his contemporaries. "Though he remained essentially Paris-based, Boldini occasionally made trips to London to paint some of Sargent's sitters... Boldini had perfected a 'whiplash' style by which the model appeared to be thrown onto the canvas... All his nervous energy... was thrown at the canvas.".

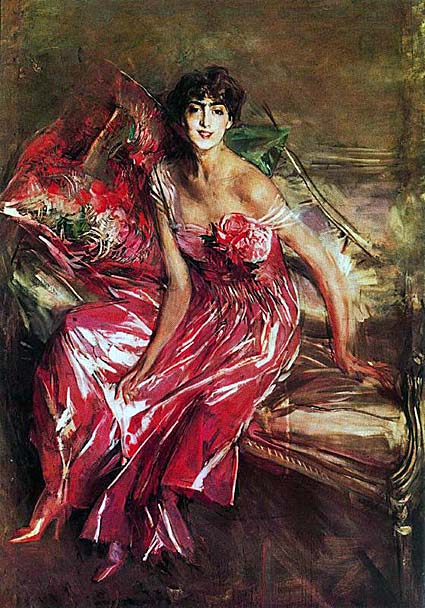

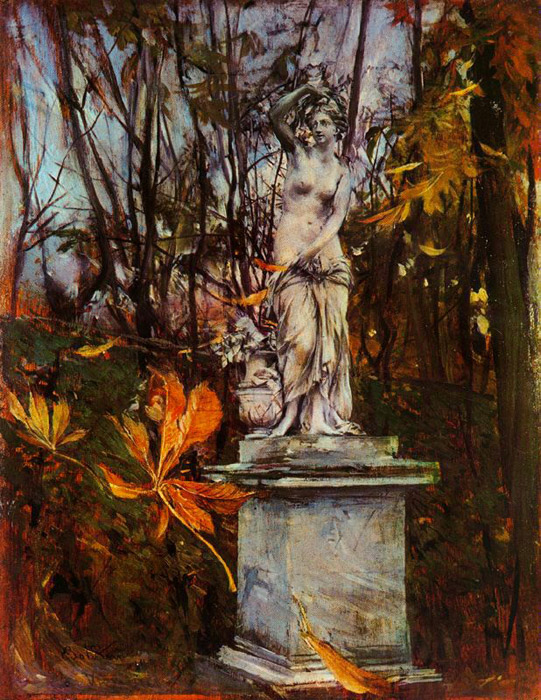

The Boldini Museum, housed on the first floor of the Palazzo Massari, is dedicated to the Ferrarese painter who lived between 1842 and 1931. After the first years of training spent in Tuscany, Paris and London, Boldini settled permanently in the French capital where he developed his own unmistakable style and became the most popular portrait painter of high society. The visit begins in the palace's elegant Baroque chapel, situated beyond the Grand Hall. This is followed by three small rooms with works realized by the artist in his younger days, among which are a Self-portrait and the oil painting Two White Horses. In the fourth room, magnificently frescoed and of vast proportions, five large paintings are on display, which alone bear witness to Boldini's mastery of the portrait: Countess Gabrielle de Rasty, The Infanta Eulalia of Spain, The Little Subercaseuse, Countess de Leusse and Fireworks, all painted between 1878 and 1891. Then come two rooms without any paintings, a corridor painted entirely with medallions and imitation sculptures and a magnificent Rococo drawing room decorated in gold and white stucco. The Boldini Collection then resumes with drawings and watercolours. The last room before the visitor retraces his steps is dominated by the splendid A Walk in the Bois (1909). From here the itinerary continues in the opposite direction, through rooms that contain numerous studies and personal belongings, among which his box of colors and pens with The Gardener of the Veil-Picard portrayed on the cover. The Woman in Rose, which has become the symbol of the museum, is exhibited in the penultimate room.

Eulalia was born in the Royal Palace of Madrid, the youngest child of Queen Isabella II of Spain and of her husband, Francis of Spain. She was baptized on 14 February 1864 with the names Maria Eulalia Francisca de Asis Margarita Roberta Isabel Francisca de Paula Cristina Maria de la Piedad. Her godfather was Duke Robert I of Parma, while her godmother was his sister Princess Margherita of Parma.

In 1868 Eulalia and her family were forced to leave Spain by the revolution. They lived in Paris where Eulalia was educated. She received her first communion in Rome from Pope Pius IX.

In 1874 Eulalia's brother King Alfonso XII was restored to the throne in place of their mother Queen Isabella II. Three years later Eulalia returned to Spain. She lived at first in El Escorial with her mother, but later moved to the Alcázar of Seville and then to Madrid.

In May 1893 Eulalia visited the United States; her controversial visit to the Chicago World's Fair was particularly well-documented. She travelled first to Havana, Cuba, before making her way to Washington, D.C., where she was received by President Grover Cleveland at the White House. She then proceeded to New York City. Eulalia was later admitted as a member of the Daughters of the American Revolution as a descendant of King Charles III of Spain.

Eulalia was the author of several works which were controversial within royal circles, although she never ceased to have frequent contact with her relatives both in Spain and elsewhere.

In 1912, under the pseudonym comtesse de Avila, Eulalia wrote Au fil de la vie (Paris: Société française d'Imprimerie et de Librarie, 1911), translated into English as The Thread of Life (New York: Duffield, 1912). The book expressed Eulalia's thoughts about education, the independence of women, the equality of classes, socialism, religion, marriage, prejudices, and traditions. Her nephew King Alfonso XIII telegraphed her and demanded that she suspend the book's publication until he had seen it and received his permission to publish it. Eulalia refused to comply.

In May 1915 Eulalia wrote an article about the German Emperor William II for the Strand Magazine. The following month she published

In August 1925 Eulalia wrote Courts and Countries after the War. In this work she commented upon the world political situation, and particularly her belief that there could never be peace between France and Germany.

In 1935 Eulalia published her memoirs in French, Mémoires de S.A.R. l'infante Eulalie, 1868-1931. In July 1936 they were published in English as Memoirs of a Spanish Princess, H.R.H. the Infanta Eulalia.

On 9 February 1958, Eulalia had a heart attack at her home in Irun. She died there on the 8th of March and is buried in the Pantheon of the Princes in El Escorial.

Born in Hamburg, Germany the eldest son and second of six children, into the Jewish family of an affluent Hamburg trader. He was an unpromising scholar and was apprenticed to Jules Porgès & Cie, the Amsterdam diamond firm. He was sent to the Cape Colony in 1875 by his firm to buy diamonds - following the diamond strike at Kimberley. Having become a business friend of Cecil Rhodes, they proceeded to buy out digging ventures and to eliminate opposition such as Barney Barnato. He rapidly became one of a group of financiers who gained control of the diamond-mining claims in the Central, Dutoitspan, and De Beers mines. Rhodes was the active politician and Beit provided a lot of the planning and financial backing.

In 1886 Beit extended his interests to the newly-discovered goldfields of the Witwatersrand and met with great success. In his business ventures there he made use of financiers Hermann Eckstein and Sir Joseph Robinson. He founded the Robertson Syndicate and the firm of Wernher, Beit & Co. He imported mining engineers from the USA and was among the first to adopt deep-level mining. Rhodes concluded a treaty with Lobengula as a result of which Beit founded the British South Africa Company in 1888. Beit became life-governor of De Beers and also a director of numerous other companies such as Rand Mines, Rhodesia Railways and the Beira Railway Company.

In 1888 Beit moved to London whence he felt he was better able to manage his financial empire and support Rhodes in his Southern African ambitions. Beit moved into Tewin Water, near Welwyn, a large Regency house with Victorian additions and 7,000 acres, and a few miles away Julius Wernher at last bought Luton Hoo, with 5,218 acres.

Inspired by Rhodes' imperialist vision, he took part in the planning and financing of the unsuccessful Jameson Raid of late 1895 which was intended to trigger a coup in the South African Republic in the Transvaal. As a result of this debacle, Rhodes resigned as Prime Minister, and both he and Beit were found guilty by the House of Commons inquiry. Beit was obliged to resign as director of the Charter Company, but was elected vice-president of the British South Africa Company a few years later. With the death of Rhodes in 1902, Beit, as one of the trustees, helped control the enormous estate.

In his will he set up the 'Beit Trust' through which he bequeathed large sums of money for infrastructure development the central and Southern Africa, in university education and research in South Africa, Rhodesia (£1,200,000), Britain and Germany. In recognition of these bequests the Royal School of Mines, a faculty of Imperial College London, erected a large memorial to Beit flanking the entrance to its building. Beit died at Tewin Water near Tewin, Hertfordshire on 16 July 1906 after seeing a rapid deterioration in his health.

Giovanni Boldini -- Italian-French Portrait Painter

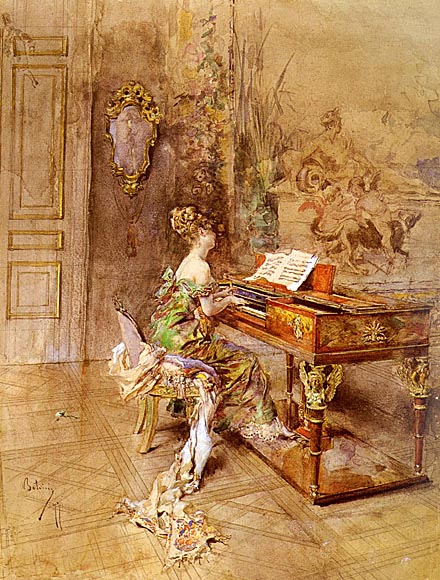

(Paul César Helleu married Alice Guerin, on July 28, 1886, so the paintings are prior to that)

Anita Petrovski, in his article "The Lesson of Piano - Femininity According to Giovanni Boldini" writes about the photographic qualities of these two paintings. The older woman, I don't think is ever identified, but the woman on the right is of Alice Guerin playing a duet in a more conventional pose; but even here, Boldini paints this stunning beauty (and by all accounts she was incredibly beautiful) with a deep décolletage of her dress and the exposed skin of her delicate shoulders.

In the second painting (below) Boldini has her stretching from the concentration of playing. Though the stretch is a natural one, the pose is not. Instantly, the second painting is charged with intimacy. The motion of her arms is abbreviated in a Boldini signature fashion of elongated flowing strokes. The hands of the older woman, however, are treated exactly the same as in the first. The subject of these two paintings, together, is unquestionably the beautiful Alice. This is quintessential French La Belle Époque style of female sensuality.

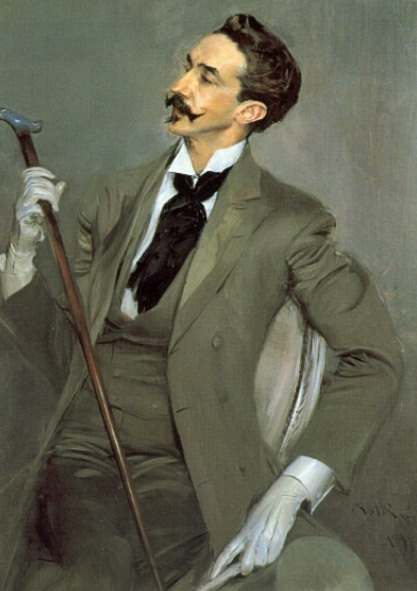

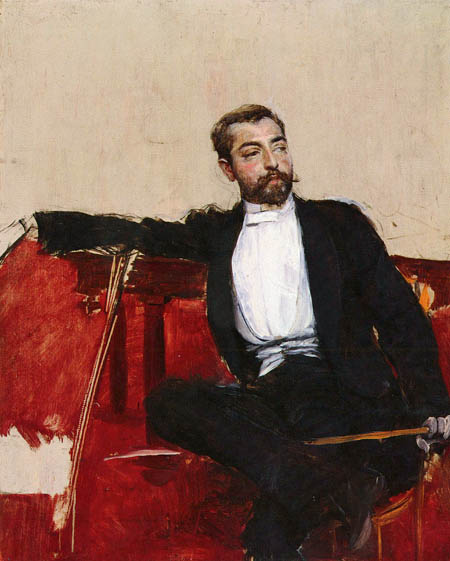

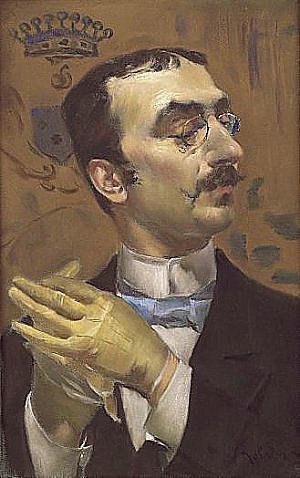

Around him floated a wide circle of artists including actress Sarah Bernhardt, composer-friends like Gustave Moreau, and Gabriel Fauré; one of his young 'disciples' the pianist Léon Delafosse; painters James McNeill Whistler, Antonio de la Gandara, Carolus-Duran, Paul César Helleu and Boldini (all paid tribute to him in paint); and there was Stephane Mallarmé, Paul Verlaine and John Singer Sargent; along with writers such as Marcel Proust, and the list is almost endless.

If you were in the Paris art scene and wanted to be a "somebody", you most certainly had to know Montesquiou.

She was the daughter of Lucy Wharton and Joseph William Drexel. Joseph was the son of Francis Martin Drexel, the immigrant ancestor of the Drexel banking family in the United States.

Elizabeth married John Vinton Dahlgren I on June 29, 1889. They had a son, John Vinton Dahlgren II. Elizabeth was widowed in 1898. Elizabeth then married Henry Symes Lehr, aka Harry Lehr in June 1901.

In 1915 the Lehrs were in Paris, and Elizabeth worked for the Red Cross. They remained in Paris after World War I, where they bought in 1923 the Hôtel de Canvoie at 52, rue des Saintes Pères in the VIIe arrondissement. Harry Lehr died on January 3, 1929 of a brain malady in Baltimore.

In 1931 Elizabeth was presented at Court to King George V and Queen Mary in London. On May 25, 1936 she married John Graham Hope de la Poer Beresford, 5th Baron Decies. His first wife had been Helen Vivien Gould. [5] [6] He died on January 31, 1944.

She died in 1944 at the Hotel Shelton. She was buried in the Dahlgren Chapel at Georgetown University, which she had built as a memorial to her first husband.

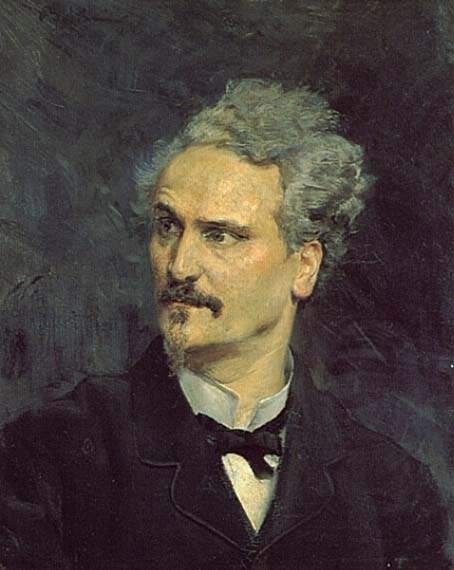

Victor Henri Rochefort, marquis de Rochefort-Luçay , 1831-1913, French journalist and politician. The editor of Le Figaro in 1863, he also founded and edited the bitterly anti-imperial journals La Lanterne (1868) and La Marseillaise (1869). After the Franco-Prussian War he founded Le Mot d'ordre (1871), supported the Commune of Paris, and was consequently sent (1873) to the penal colony of New Caledonia. He soon escaped and revived La Lanterne in Geneva, Switzerland. After the general amnesty of 1880 he returned to Paris and started L'Intransigeant. Twice elected a deputy, Rochefort, in a political switch from the extreme left to the extreme right, became an ardent supporter of Georges Boulanger and was forced to flee France. Tried in absentia, he remained in exile from 1889 to 1895. Later, Rochefort's extreme nationalism led him to take a violent stand against Alfred Dreyfus in the Dreyfus Affair.

But Whistler disliked the portrait: 'They say that looks like me, but I hope I don't look like that!' His friends disagreed and thought it accurately portrayed him in his worst temper.

" . . . [She was the] second daughter of a wealthy cotton manufacturer, Alberto Amman and his wife Lucia Bressi, [but the] early deaths of her parents made Luisa and her elder sister, Francesca, the wealthiest heiresses in Italy . . .

Gertrude Elizabeth had a close circle of friends, including the artist Edward Burne-Jones and Kate Greenaway, and became a successful writer and journalist.

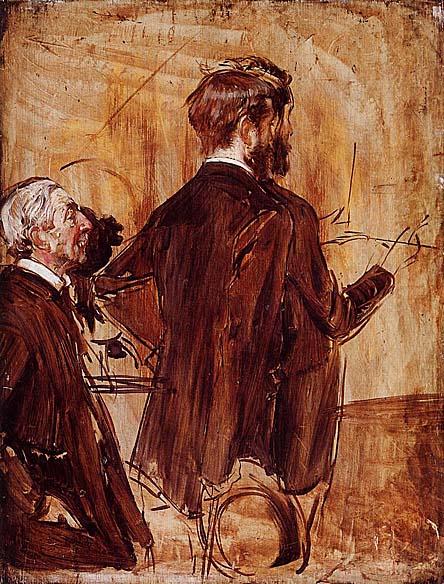

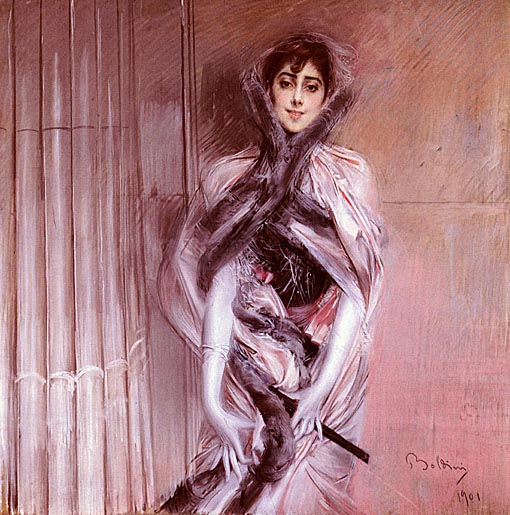

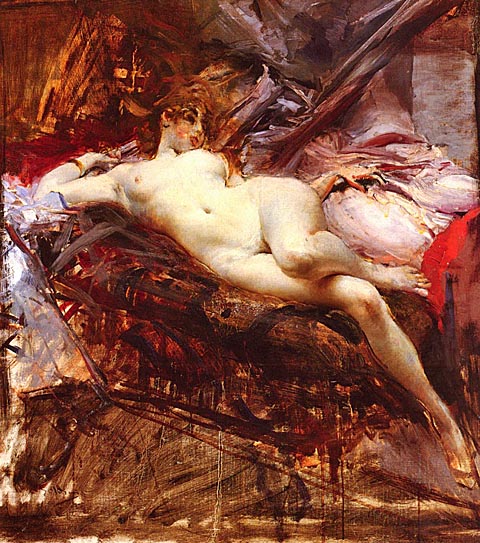

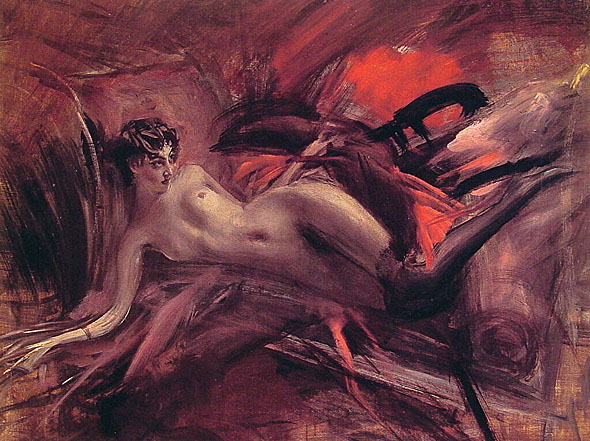

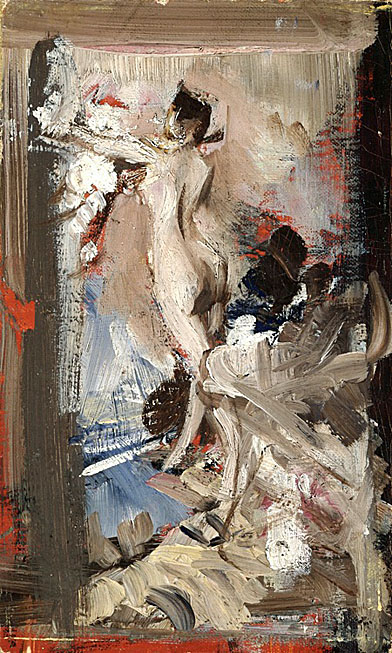

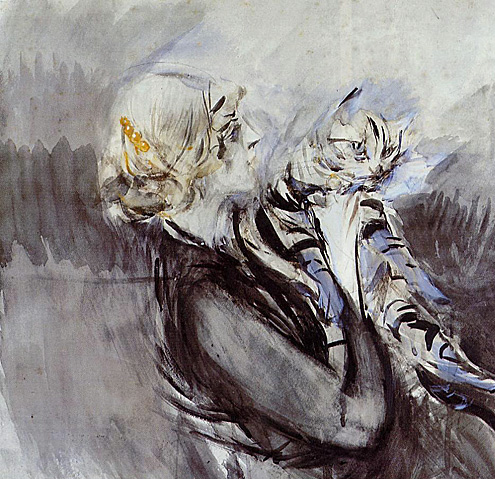

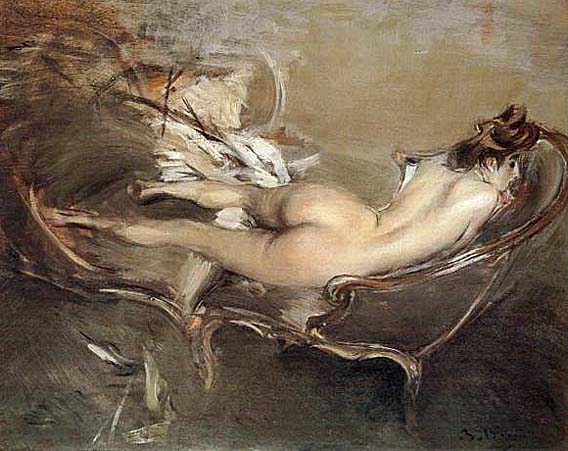

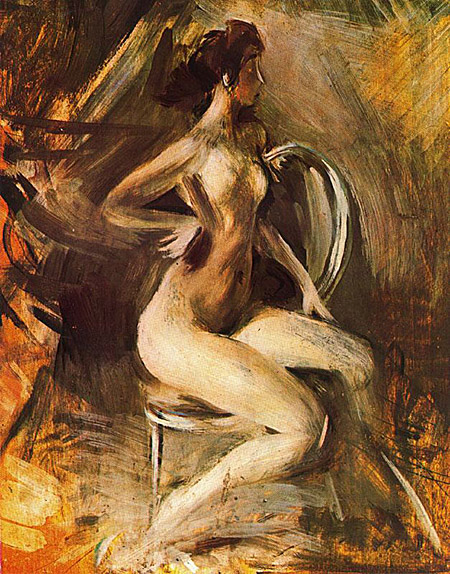

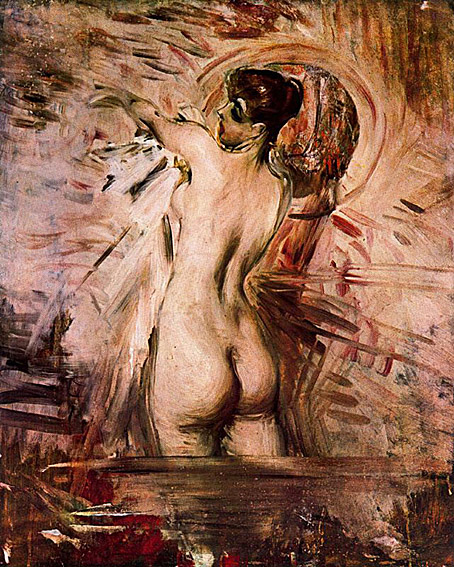

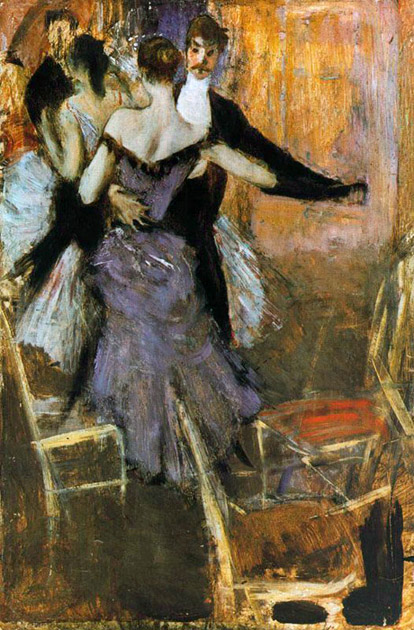

In sketches like this Boldini is seen at his freest, the fluid brushstrokes and stylized curvatures and elongations of the figura serpentinata epitomizing his handling of the human form. Boldini's sinuous lines and lively forms lend his works an expressiveness but also a decorative idiom rooted in art nouveau. The grey tonalities also call to mind the work of Whistler, Boldini's contemporary in Paris.

Avant-garde though he was, Boldini always remained indebted to the sixteenth-century Italian masters, whose work he had copied assiduously as a young student and later at the Academy in Florence. The serpentine forms and grayish palette that so characterize his work clearly hark back to Parmigianino and the Italian Mannerist tradition.

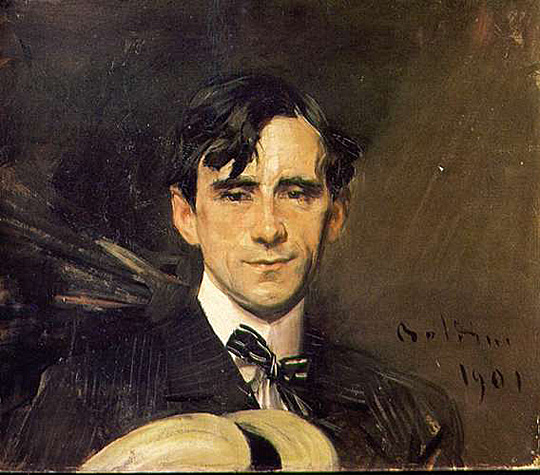

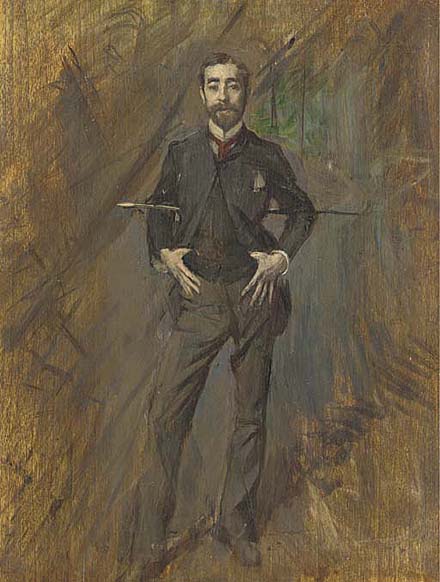

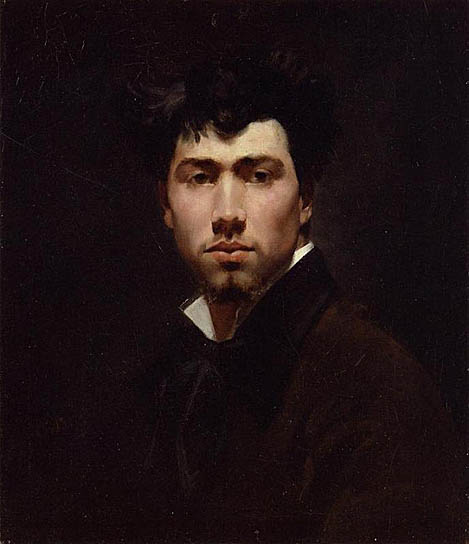

The dark background and strongly focused lighting give 'Portrait of a Young Man' a seventeenth-century Dutch or Spanish flavor that sets the picture apart from other early portraits in Boldini's career. Together with the self-contained gaze of the sitter and the exquisitely subtle coloring of his brown jacket, black collar and Prussian blue cravat, the blending of old and new suggests the self-portrait style popular among ambitious young Parisian painters of the 1860's. Prodigiously talented, Boldini moved in a broad artistic circle in Florence during the mid-1860's, and he might well have encountered contemporary French portraits in the collections of cosmopolitan collectors such as Prince Demidoff or at the Florentine villa of the eccentric French artist Marcellin Desboutin. The refined paint handling of 'Portrait of a Young Man' does not yet reveal the bravura brushwork that would make Boldini's success as a portrait painter in the next decades; but the ability to orchestrate a deliberately limited palette and to use incidental costume details (such as the two glimpses of white collar) to focus attention on a face would become trademarks of Boldini's achievement.

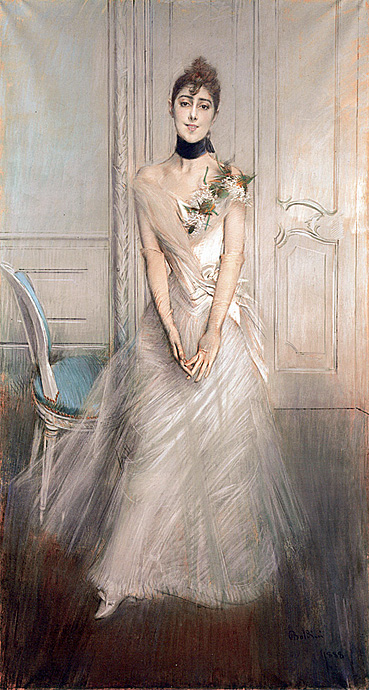

Having decided to keep the first pastel, Boldini excitedly set out to execute a further work for the sitter's family to admire in Chile, known as 'Ritratto di Emiliana Concha de Ossa', in abito bianco. This pastel is certainly one of the most refined that the artist ever executed, having worked the pastels in exactly the same way as he had done only months previously. Set against the elaborate arabesque rococo background clothed in virginal white, her gloved hands and arms playfully disclose her impatient coquettishness. With his detailed yet strong pastel strokes Boldini conveys the awkward sweetness, naïveté and timidity that make this sitter so timelessly alluring.

Only ten years old when she sat for Boldini, Giovinetta comes across in her portrait as a challenging customer, assured and commanding as she locks the artist and viewer in her gaze. Whether Giovinetta chose her own costume, or whether Boldini threw it together to amuse her, she is very strangely dressed. Her white bonnet, with its double rows of ruching, was intended for a four or five year old child; the black velvet cape pulled askew across her shoulders and the tightly furled umbrella was walking costume for a grown woman. Still, the coloring of Giovinetta's outfit complements her dark eyes and rosy cheeks and she wears the disparate garments with aplomb. Boldini treated her unusual garb with the same attention to flourish and detail that he employed for adult clients.

As Giovinetta slides down on the satin cushions, her dress has pulled back above the top of her black stocking, revealing an inch of thigh. 'The notorious centimeter of skin,' as Boldini's wife described it, created a damaging scandal when Boldini exhibited the painting at the Venice Biennale in 1897 (although it should be noted that the French had barely noticed when Boldini presented the work in Paris, a few years earlier). Boldini's willingness to exhibit the portrait in important presentations suggests he himself recognized no leering irony in his conception of Giovinetta. It is much more likely that his deliberate inclusion of the detail (which he could easily have painted out) was part and parcel of the ambiguities presented by Giovinetta herself, a self-assured coquette, halfway between childhood and womanhood, still too innocent to fully understand her own power to charm.

Giovinetta Errazuriz was the daughter of Madame Josephina Alvear de Errazuriz, a prominent Chilean expatriate living in Paris during the 1890's.

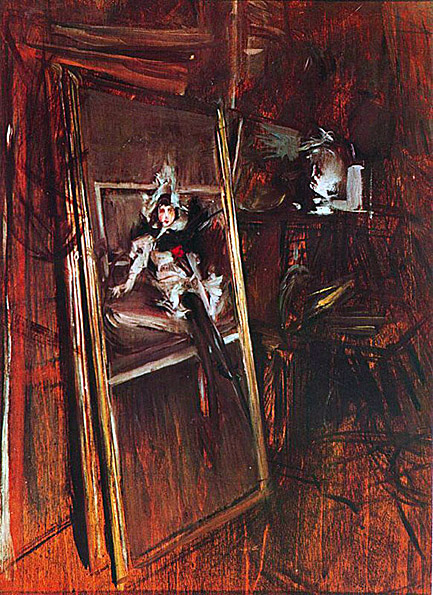

Boldini's affection for his painting of Giovinetta is underlined by the 'portrait of a portrait' which he kept in his studio: a painting of his workshop with the present 'Portrait of Giovinetta' propped aslant in the center (Museo Boldini, Ferrara).

Born Natalina Cavalieri in Viterbo, Latium, Italy, she lost her parents at the age of fifteen and became a ward of the state, sent to live in a Roman Catholic orphanage. The vivacious young girl was extremely unhappy under the strict raising of the nuns, and at the first opportunity she ran away with a touring theatrical group.

Blessed with a good singing voice, a young Cavalieri made her way to Paris, France, where her stunning good looks opened doors and she obtained work as a singer at one of the city's café-concerts. From there she performed at a variety of music halls and other such venues around Europe while still working to develop her voice for the opera. A soprano, Cavalieri took voice lessons and made her opera debut in Lisbon, Portugal, in 1900, the same year she married her first husband, the Russian Prince Bariatinsky. Eventually she followed in the footsteps of Hariclea Darclée as one of the first stars of Puccini's Tosca. In 1904 she sang at the Opéra de Monte-Carlo then in 1905, at the Sarah Bernhardt Theatre in Paris, Cavalieri starred opposite Enrico Caruso in the Umberto Giordano opera, Fedora. From there, she and Caruso took the show to New York City, debuting with it at the Metropolitan Opera on December 5, 1906.

Cavalieri remained with the Metropolitan Opera for the next two seasons performing again with Caruso in 1907 in Puccini's Manon Lescaut. Renowned as much for her great beauty as for her singing voice, she became one of the most photographed stars of her time. Frequently referred to as the "world's most beautiful woman," she was part of the tight lacing tradition that saw women use corsetry to create an "hour-glass" figure. During the 1909-1910 season she sang with Oscar Hammerstein's Manhattan Opera Company. Her first marriage long over, she had a whirlwind romance and marriage with Robert Winthrop Chanler (1872-1930), a member of New York's prominent Astor family. However, this marriage lasted only a very short time and Cavalieri returned to Europe where she became a much-loved star in pre-Revolutionary Saint Petersburg, Russia, and in the Ukraine.

During her career, Cavalieri sang with other opera greats such as the Italian baritone Titta Ruffo and the French tenor Lucien Muratore, whom she married in 1913. After retiring from the stage, Cavalieri ran a cosmetic salon in Paris. In 1914, on the eve of her fortieth birthday - her beauty still spectacular - she wrote an advice column on make-up for women in Femina magazine and published a book, My Secrets of Beauty. In 1915, she returned to her native Italy to make motion pictures. When that country became involved in World War I, she went to the United States where she made four more silent films. The last three of her films were the product of her friend, the Belgian film director Edward José.

Married for the fourth time to Paolo d'Arvanni, Cavalieri returned to live with her husband in Italy. Well into her sixties when World War II broke out, she nevertheless worked as a volunteer nurse. Cavalieri was killed in 1944 during an Allied bombing raid that destroyed her home in the outskirts of Florence.

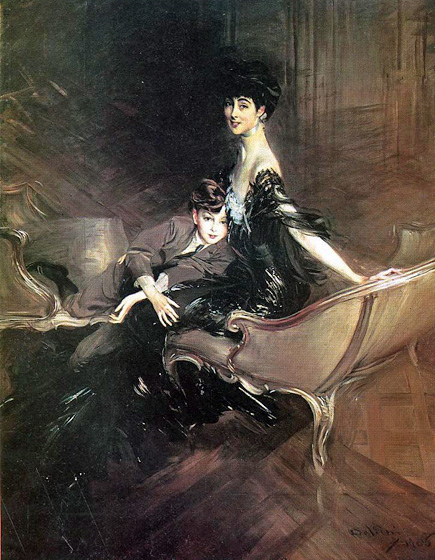

_and_Her_Son_Jean_1898.jpg)

Boldini's choice of pose with a mother looking off, away from her son, and in fact visibly restrained from moving by the child's embrace, is a challenge to prevailing notions of good-motherhood, at least as those were celebrated in family portraiture. Often compared to the static, forward-facing mother and son in John Singer Sargent's Mrs. Edward Davis and her son Livingston (Los Angeles County Museum of Art) because both young boys wear the fashionable sailor suits of the 1890's, Boldini's portrait is a testament to fashionably fast lives and the competing demands on his sitters as the nineteenth-century turned to twentieth. The tensions Edgar Degas (a Boldini friend) might have teased out in such an interaction are skillfully undercut by the young boy's playful smile and his mother's restraining hand. The viewer senses a larger world, beyond the picture frame, has momentarily intruded.

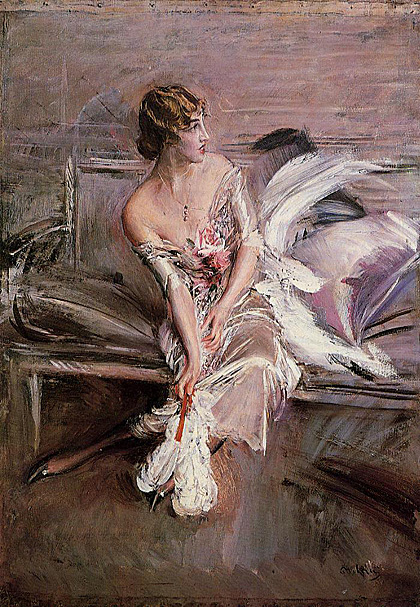

This work, which dates from 1912, shows Boldini at the height of his powers. The vigorous technique and swirl of colors convey an exciting vitality while the direct gaze of the sitter is both provocative and alluring. It compares favorably with other major works from 1911-12, such as the portrait of Mrs. Blumenthal, now in the Brooklyn Museum of Art. The sitter, Mme. Juilliard, was the wife of a prominent Parisian banker; the pose which Boldini asked her to adopt is closely imitated in a subsequent portrait from 1916, Portrait of Signora Olivia Concha de Fontevilla or La donna in rosa now in the Boldini Museum in Ferrara.

This painting perfectly illustrates how Boldini's expressive technique had so fervently captured the so-called nervous energy and high fashion of the period. His later compositions were painted with an almost expressionist technique of impasto and strong and long brushstrokes almost to the point of abstraction. It was as Serge Lifar, the Ballets Russes choreographer, once said: 'useless to explain Boldini because he is a forerunner. It will take a century before magician of movement is fully understood and appreciated.'

Mrs. John Howard-Johnston, née Dolly Baird of Dunbarton, was a Scottish beauty -- note her lush red hair which Boldini has flattered and tamed with the choice of a cold pink-lavender gown -- who first married British industrial wealth and then, following Howard-Johnston's death, remarried into French aristocratic status.

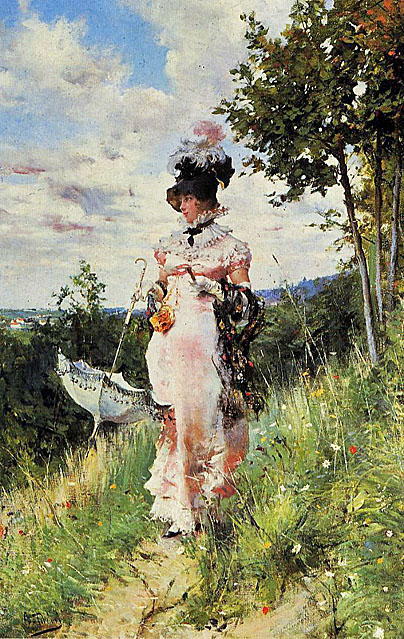

Anxiousness perhaps produces pro-activeness, and this is certainly the case for Ernest-Ange Duez who, in addition to becoming a leading artist of the late nineteenth century, was a strong advocate for the advancement of artistic styles outside of the Salon system, furthering the avant-garde move towards an art that was free of the staid principles advocated by the École des Beaux-Arts. In his own work, he was a devotee of the Normandy coast, and can be loosely associated with the Impressionist group, though his execution differs somewhat in style.

Ernest-Ange Duez was born in Paris on March 8, 1843. In his early twenties, when others had already begun their official artistic training, Duez had "accepted the family decree that he should enter a silk house for business" where he remained for three years until, at the mature age of twenty-seven, he could no longer push aside his desire to pursue a career as an artist. His training began in the Parisian ateliers of Isidore-Alexandre-Augustin Pils, a well-known Realist painter, and Carolus-Duran, the adopted name for Charles-Auguste-Émile Durand, who became well known for his portraits and led an atelier that produced many successful artists, such as the Americans John Singer Sargent and James McNeill Whistler.

After absorbing the methods of both of his teachers, Duez debuted at the Salon of 1868 with Mater Dolorosa (Mater Dolorosa). While this training gave him experience in the general manners of the École des Beaux-Arts, after several long years of painting and studying in detail he became a conspicuous follower of Édouard Manet and showed tendencies towards adherence to Impressionists principles.

But at this time Impressionism was still in its development, and not wholly accepted by either the public or the Salon juries. The definition of just what Impressionism was had not yet been determined, allowing several interpretations to circulate. Equally contestable were the value of each painter's "brand" of Impressionism. Writing in 1888, after Impressionism had been around for several years, C.H. Stranahan wrote that: Impressionism is an elastic term so far as it is to be applied to a so-called "school." Rigidly applied it is misleading. There are, it may be said, two kinds of impressionists. Henry Houssaye said in 1882: "Impressionism receives every form of sarcasm when it takes the names Manet, Monet, Renoir, Caillebotte, Degas; every honor when it is called Bastien-Lepage, Duez, Gervex, Bompard, Dantan, Goeneutte, Butin, Mangeant, Jean Béraud, or Dagnan-Bouveret." There is cause for this different estimate. The latter painters have a nicety of finish, a delicacy of treatment wholly unknown to the former, which they carry out under the impressionist' doctrine of light and color. Here critics have aligned Duez with a more acceptable form of Impressionism. But at the same time that some artists came under fire for adopting the principles of Impressionism and the freeness of their brush, the lightness of their palette, Duez really only established himself after he advocated the way of painting pursued by Manet, considered somewhat less an Impressionist but rather as an artist who was a visionary for the future.

Early in his career, Duez began with a style of naturalism, described by Montrosier "…he attacks modernity of which he will rapidly become one of the most sincere translators. He simply paints, the people that he meets each day, placing them in their appropriatte milieu…" It was this sense of naturalism that would both surprise audiences and make him a strong artist espousing the precepts of Impressionism.

It wasn't until 1874 that Duez attained a level of success that any artist would aspire to. At the Salon of that year, he exhibited Splendeur et Misère (Splendor and Misery) for which he was given a third-class medal. Most important for his recognition as a public persona, this composition "set all of Paris talking about this young artist" … even though the work was "criticized, condemned, accused of being merely sensational". The work was somewhat characteristic of the Impressionist style but was carried out in a more "finished" look thus counteracting one of the main criticisms leveled at Impressionist works that simply did not look like completed paintings to many nineteenth century viewers.

Duez's links with Impressionism were still tenuous, and W.C. Brownell thought that Duez exhibited certain qualities beyond those of the Impressionist group:

Gervex and Duez are very much more than impressionists, both in theory and practice. There is nothing polemic in either.…Personal feeling is clearly the inspiration of every work of Duez, not the demonstration of a theory of treating light and atmosphere.

Having found success, Duez became intrigued by landscapes and he moved to Villerville, between Trouville and Honfleur in Normandy. He was so taken by the effervescence of the light and atmosphere of that region, that around 1878 he built a glass studio along the seashore so that he could continue painting during the winter months when he could not go outside. He could thus still pose his subjects in the light that one can only get outdoors. In this new studio he attempted one of his most famous works, Saint Cuthbert, "one of the most remarkable pages of modern painting" a large triptych that was eventually purchased by the state and placed in the Luxembourg Museum after its exhibit at the Salon of 1879. Contemporary audiences were shocked by the use of a modern day landscape setting, one that was based on Villerville where he was working, instead of a more historically-oriented setting that was not as anachronistic. If they had traveled to Duez's site, seen that he had constructed a glass studio to pose hi s models outdoors, while maintaining the attitude of the traditional indoor studio, they would have been inspired by his sense of modernity. Glass studios were the rage in artistic circles at the time.

Much of his work from this point on is based on scenes at the beach, with young women holding their parasols, enjoying the scene, or children playing near the water, though there was not the sense of nostalgia that might be construed by choice of such a theme. Duez was just one of many artists who had come to the Normandy beaches, described by Elizabeth G. Martin in "A Haunt of Painters":

…it is still the resort of painters. Year after year Guillemet and Duez, Butin, Dantan, and a lengthening train of men less known or still altogether unknown, find here a perennial source of inspiration. Sketching-umbrellas begin to dot the beach, and easels get into position near the washing-fountains, public and private, or in the leafy shelter of the charming lanes, so soon as summer fairly opens, and linger until autumn is well over.…French painters, however, know little of that demarcation between landscape and figure which has been emphasized more sharply in America than elsewhere, and there, no doubt, chiefly because figures were really rare where scenery was most beautiful, or jarred upon the artistic sense by want of harmony with their surroundings. Here all is congruous-occupation, costume, attitude; nay, as one leaves the precincts of the town and strolls through lane or byway, even the houses and steep-roofed barns fit into the landscape as naturally and harmoniously as the trees…

During this period he was also maintaining his ties with the Parisian Salons, of which he was to serve as a jury member eight times; he was also elected a member of the first Honorable Council of Ninety, which formed the administration of the Société des Artistes Français, along with other successful artists such as William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Alexandre Cabanel, Jean-Paul Laurens, Henri Fantin-Latour, and Jules Bastien-Lepage, among several others.

More important for the art of exhibition in late nineteenth century France was his involvement in the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts, a counter-faction against the Société des Artistes Français which would hold its own exhibitions that eventually led to the demise of the annual Académie des Beaux-Arts Salon. Earlier in his career Duez showed his pro-activeness and interest in furthering the career of artists working outside of the strictly academic tradition, when in 1879 he signed a petition requesting a reorganization of the Salon. The petition accused the Salon juries of biases, and because of this:

The administration accepted the idea and it went into effect beginning with the Salon of 1881. This Salon was the first entirely managed by artists, and it is not fortuitous that the juste milieu artists honored Manet with a medal against the wishes of the Academy."

This is interesting considering that Duez was indeed part of the previously mentioned "Honorable Council of Ninety" with direct affiliations to the Société des Artistes Français. But at the same time, the latter Société was effectively driven by Bouguereau and Cabanel, certainly not avant-garde artists in the least. The Société Nationale, was conceived on December 28, 1889, and included members such as Ernest Meissonier - the first president - Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, Duez's teacher Carolus-Duran, Eugène Carrière, Jean-Charles Cazin, Pascal-Adolphe-Jean Dagnan-Bouveret, Henri Gervex, and Alfred-Philippe Roll. These men and the establishment of this group played a decisive role in changing the world of art exhibitions in Paris.

Duez also executed several commissions during his career, including decorative panels entitled Virgil Seeking Inspiration from the Woods (1888) for the Sorbonne and Botany and Physics (1892) for the Hôtel de Ville in Paris. He also created a number of textile designs, devoting his time to the applied arts.

Ernest-Ange Duez met an unfortunate and early death when he had a hemorrhage while biking in the Forest of Saint-Germain. He died on April 5th, 1896. His work which began on a rather academic note progressed into his own form of Impressionism based on the prevailing sense of artistic freedom sought after by many artists of the avant-garde. His participation in several decisive actions encouraged the arts and artists to explore new directions without fear of Salon rejection, thereby creating a more fertile ground for the artistic expressions to take full root in late nineteenth century France.

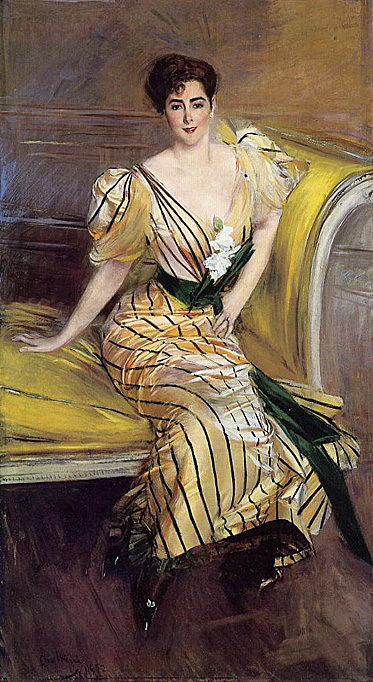

This full-length portrait shares with Boldini's portrait of Sargent of 1889 the frontal stance with hands on hips, the element of the walking stick and the sketchy background. The Comtesse Gabrielle de Rasty sat for Boldini on many occasions from 1878 to about 1888.

Born on August 8, 1859 in Villiers-sur-Orge into a bourgeois Catholic family, he attended the Lycee Fontanes and later the Jesuit College Stanislas in Paris. He became fluent in Latin and German. In 1885, he obtained a law degree and subsequently started with a job in the family's publishing firm of Gauthier-Villars.

Willy was a lady's man; Rachilde described him "as a man of the world, a brilliant Parisian rake". In 1889 he met Colette, 14 years younger than him; they married on May 15, 1893. As a writer and music critic he was an incessant and effective self promoter, under whose directions his "slaves" wrote articles and novels. His ghostwriters may or may not have received recognition but participated because publication under the Willy name secured a high publication rate and good income. With his literary workshops Willy published more than 50 novels. His participation varied and included conventionalizing, editing, and adding sections, plots, and puns.

Colette was initially handling his correspondence, but became soon involved in writing on her own starting with Claudine, her first oeuvre under the Willy label. The success led to more novels in the Claudine series. It is generally acknowledged that these books were written by Colette, but he had his hand in it editing and honing the manuscripts. Willy also went into merchandizing dolls and other items based on the Claudine novels.

Colette soon learned that Willy had other affairs, and she met his mistress Charlotte Kinceler who later became her friend. Later Willy and Colette had an affair unbeknownst to each other with the same woman, the American socialite Georgie Raoul-Duval, nee Urquhart. Upon discovery, they made it a threesome and attended the Bayreuth festival together.

The marriage to Colette lasted until 1910, although in the years prior they were already separated. While Willy made a lot of money, he squandered it with ease on women and gambling and was facing bankruptcy. Willy went on to marry Marguerite Maniez, also known as Meg Villars after her marriage. He had no children from his two marriages; his son, Jacques, was the offspring from an affair before. Willy died on January 12, 1931 in Paris. Three thousand mourners followed his casket to the Montparnasse cemetery.

Born Anastasia May Stewart, also known as Nancy Stewart, on 20 January 1883, the future Princess Anastasia of Greece was the daughter of William Charles Stewart and Mary Holden Stewart of Cleveland, Ohio. Twice married before Anastasia's engagement in 1914 to Prince Christopher of Greece and Denmark and brother of Constantine I of Greece created legal complications that delayed their marriage by six years. Her first marriage to George H. Worthington lasted barely four years before she was married to her second husband William Bateman Leeds, a tin millionaire. After his death in 1908, Anastasia inherited his sizeable fortune which in turn she used to help the Greek Royal Family during their exile in the 1920's.

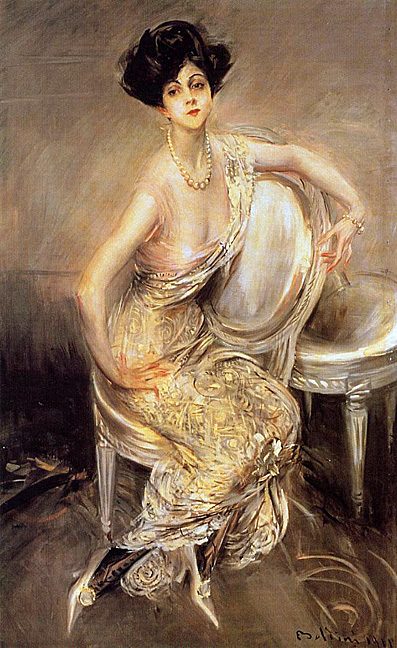

On marrying her third husband on 1 January 1920 in Vevey, Switzerland, Anastasia became daughter-in-law to George I of Greece and Olga Konstantinova Romanov, Queen of Greece and Grand Duchess of Russia, thus re-affirming her status as one of the most wealthy and powerful women of her day. While no children were born from her third and final marriage, Princess Anastasia and Prince Christopher had a son from her previous marriage, William Bateman Leeds Jr, who was married a year after his mother to Kseniya Georgiievna Romanov, Princess of Russia. Boldini, never a man to deny his insatiable taste for wealth, beautiful women and blue-blooded aristocracy, relished such a commission. Born in Ferrara, the eighth of thirteen children, Boldini showed a remarkable talent for portraiture from a young age. The tenets of immediacy and spontaneity championed by the Macchiaioli appealed to Boldini during the three years he spent in Florence in the 1860's and made a lasting impression upon his technique transforming his early stiff academic finish into the free spontaneous style that became the hallmark of his work. It was natural therefore that on settling in Paris in 1872, he established close friendships with the leading Impressionist artists of the day including Degas, Manet, Whistler and Sargent.

'Portrait of a Lady with Lilacs' may indeed be the portrait of a young woman whose identity has been lost to us, perhaps a close friend of the artist as suggested by her easy smile. But the casual nature of her bare shoulder, semi- transparent stole and strategically placed stem of lilacs all suggest a degree of intimacy that would be just a step beyond appropriate in the encounter between client and portraitist. It seems just as likely that the painting is a created image, posed by a model, intended to tempt the viewer with the sensuality of the subject matter and the equally pronounced sensuality of Boldini's characteristically fluid paint work. From the roiling red curls of her unbound hair through the self-assured chaos of the white splotches that suggest embroidery on her tulle wrap, both the lady and the painting invite one's touch.

The sitter for 'The Black Sash' is unknown; at the time of the painting's sale from the Baron de Rothschild's collection, Madame Paulette Howard-Johnston (the daughter of Paul Helleu, a contemporary painter and friend of Boldini's) suggested the red-headed beauty might be a Mrs. Law, an American socialite who also posed for Helleu.

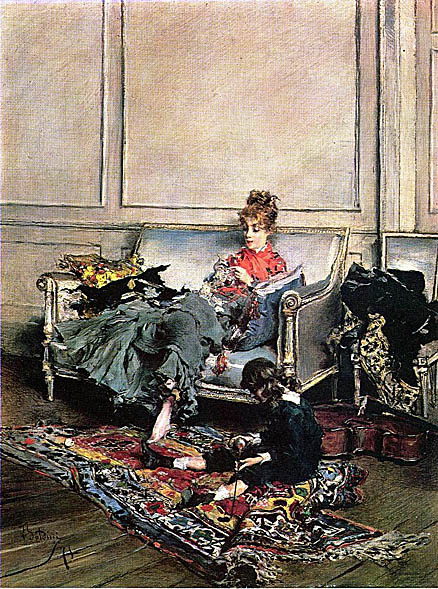

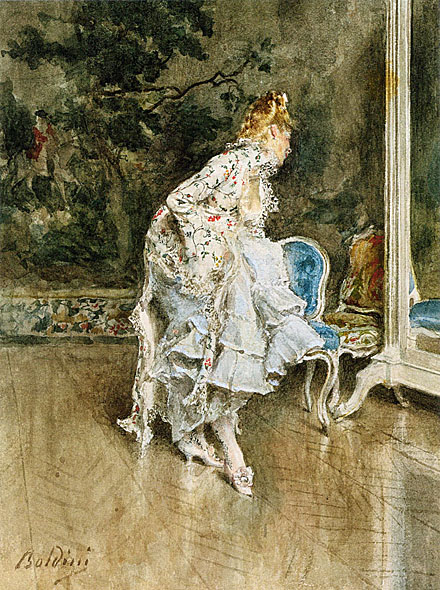

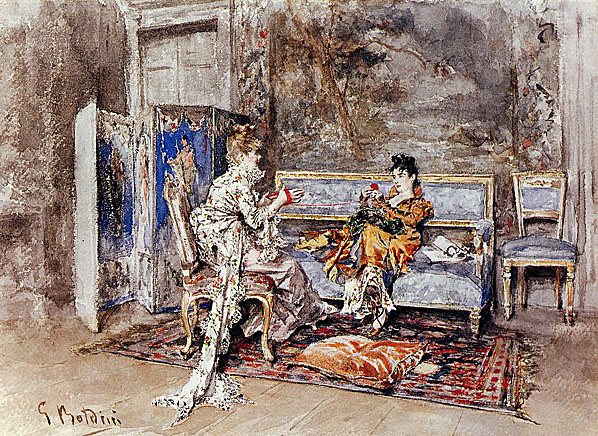

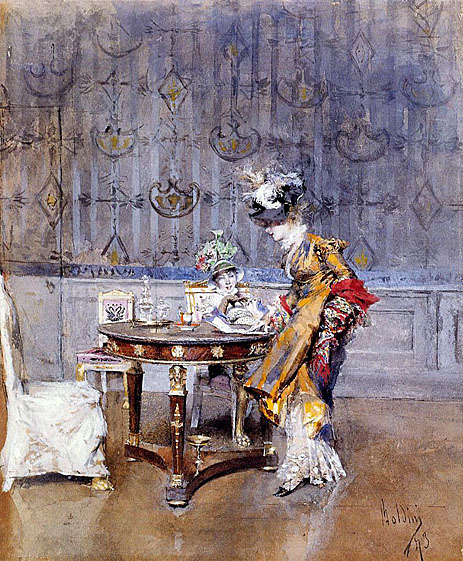

In his choice of subject and scale, Boldini reveals the influence of contemporary master and top seller Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissionier, whose works detailed scenes from France's past periods of wealth and prominence. Collectors faced with the harsh realities of "modern" nineteenth century society were eager to acquire works that suggested (however unrealistically) a gentler, less wrought era of parlor dramas, expensive clothes and fine furnishings. Yet, 'La Lettre', reveals Boldini's personal and unique approach to the genre---particularly as it is a watercolor. He employs the medium to build a softly layered palette of lacey whites, pale blue-grays and minty greens, in contrast with heavily saturated splashes of mustard, crimson and mahogany. While the artist often employs his brush to create the loosely defined swags of the wallpaper design, his strict control also renders surprisingly subtle, yet powerful, elements which heighten visual interest, such as the pooling reflection of upholstery and dress in the high-gloss of the floor. Interestingly these painterly contrasts of technique and form evoke Empire period décor, which embraced Neoclassical motifs. In comparison with the women's flounce of feathers and folds of fabric, the furniture surrounding them is symmetrical and strong of line. The chairs are most likely the creation of a good menuisier, such as the celebrated Jacob or Bellangér. The guéridon (center table) with its glossy grained wood, bronze appliques, and Sphinx-like decorations alludes to Napoleon's conquest of Egypt and his legendary ambitions of imperial dynasty. It is likely no accident that the pink upholstered chair in the background bears a double swan design, their touching beaks and curved necks form a heart, and reveal the influence of Empress Joséphine on decoration: she was very fond of the birds, which often served as a primary decorative motif for her state rooms at Malmaison.

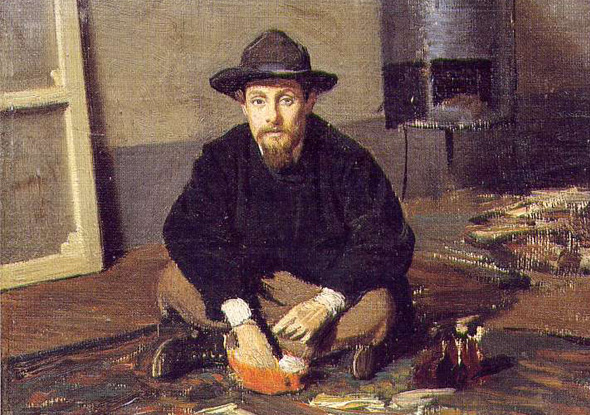

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec was born on Nov. 24, 1864, in Albi, France. He was an aristocrat, the son and heir of Comte Alphonse-Charles de Toulouse and last in line of a family that dated back a thousand years. Henri's father was rich, handsome, and eccentric. His mother was overly devoted to her only living child. Henri was weak and often sick. By the time he was 10 he had begun to draw and paint.

At 12 young Toulouse-Lautrec broke his left leg and at 14 his right leg. The bones failed to heal properly, and his legs stopped growing. He reached young adulthood with a body trunk of normal size but with abnormally short legs.

Deprived of the kind of life that a normal body would have permitted, Toulouse-Lautrec lived wholly for his art. He stayed in the Montmartre section of Paris, the center of the cabaret entertainment and bohemian life that he loved to paint. Circuses, dance halls and nightclubs, racetracks--all these spectacles were set down on canvas or made into lithographs.

Toulouse-Lautrec was very much a part of all this activity. He would sit at a crowded nightclub table, laughing and drinking, and at the same time he would make swift sketches. The next morning in his studio he would expand the sketches into bright-colored paintings.

In order to become a part of the Montmartre life--as well as to protect himself against the crowd's ridicule of his appearance--Toulouse-Lautrec began to drink heavily. In the 1890's the drinking started to affect his health. He was confined to a sanatorium and to his mother's care at home, but he could not stay away from alcohol. Toulouse-Lautrec died on Sept. 9, 1901, at the family chateau of Malrome. Since then his paintings and posters--particularly the Moulin Rouge group--have been in great demand and bring high prices at auctions and art sales.

In 1848 he participated in the liberation revolt and in 1849 he took part in the defense of Bologna. In 1853, perhaps for political reasons, he moved to Florence, where together with Severini and Borrani he joined the rising macchiaioli group, attended the Caffé dell'Onore and then, from 1855, the famous Caffé Michelangelo.

The first experiments of outdoor painting had no immediate consequence in his own painting, which until 1857/58 was tied to the compositional schemes and formal balance of the academic genre painting, as shown in the works which he exhibited in that period at the Florentine Promotrici. Cabianca however began to show more and more interest for the construction of the image through chromatic values and tones of light which was adapted first to genre paintings, such as "Abbandonata" (The Abandoned), 1857, and "Goldoni giovinetto" (The Young Goldoni), then during the Summer of 1858, which he spent in La Spezia with Signorini, to "en plein air" works.

Between 1859 and 1860, together with Banti, he devoted himself to regular "painting expeditions" in the countryside between Montemurlo and Piantavigne, making long reflections and applying the new theories of the "macchia". Paintings such as "Rovine di San Pietro a Portovenere" (Ruins of San Pietro in Portovenere) and "Le monachine" (The small Nuns), exhibited in Turin in 1861, are among his masterpieces and they make him one of the emblematic painters of the initial stage of the Macchiaioli story.

In 1861 Cabianca visited Paris with Signorini without being particularly impressed by it; the following year he came back to Tuscany and painted in Montemurlo; however he didn't abandon the hostorical-academic subject as shown by the painting "Novellieri fiorentini del secolo XIV" (Florentine Story-tellers of the XIV Century) which he brought to the Florence exposition of 1861. The academic component got more evident during his stay in Parma which lasted about seven years beginning 1863, with frequent visits to Florence and Rome, where he moved in 1870, becoming friend of Nino Costa and painting from life small works according to the Macchiaioli technique.

In the abundant production of the 70's and 80's we find beautiful paintings dating back to the stay by Diego Martelli in Castiglioncello and many views of the countryside by Anzio and Nettuno. In 1876 he was among the founders of the "Watercolorist Society", in 1886 he subscribed to the anti academic Roman group "In Arte Libertas" together with Coleman, Costa and De Maria. In 1893 a paralysis forced him to an almost complete inactivity.

Under her feet, a brightly colored woven carpet of contemporary origin dazzles in its vivid geometric design. The Empire ormolu mounted mahogany secretaire abbatant in the background, and the mahogany directoire to her left underscore the lady's wealth and aristocratic taste. Boldini's masterful layering of motley fabrics and textures, while maintaining the integrity of each distinct article is an incredible technical achievement. The throw on the lady's lap spirals casually to the floor, an effect that showcases Boldini's recurrent interest in the serpentine form, and recalls inadvertently the sinuous form of Sarah Bernhardt's gown in portraits by Georges Clairin, for example.

In 1874 Boldini painted two important compositions, Place Clichy and Place Pigalle. Our picture, probably painted in 1874, is a study for Place Pigalle.

These spontaneous drawings and sketches are in contrast to the small-scale eighteenth century style interiors which he was producing for the dealer Adolphe Goupil during this period.

1874 also marked a turning point in Boldini's career, as this was the first year he exhibited at the Paris Salon. It was also the year of the opening exhibition of the Impressionists at the Salon des Refusés, a movement by which this sketch is greatly influenced.

Source: Art Renewal Center

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.