Luca Signorelli

Italian Renaissance Painter

1445 - 1523

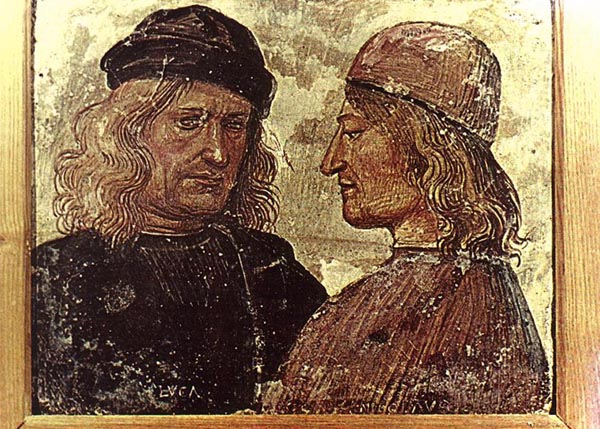

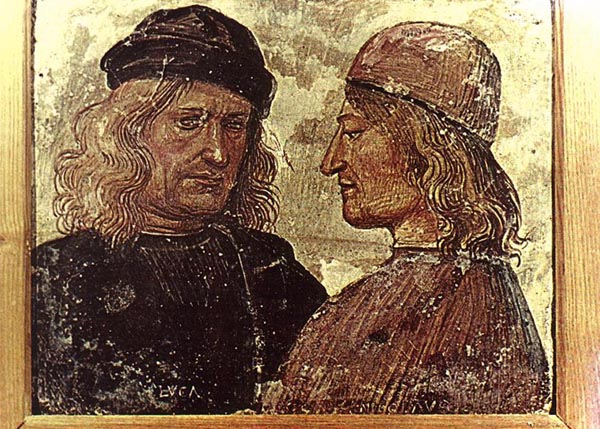

Self-Portrait with Niccolò d'Angeli Franceschi: 1500 or 1503

This painting is on a brick on the back of which is an inscription praising Signorelli as the painter of the Chapel of San Brizio. Niccolò d'Angeli Franceschi was the 'camerarius' of the Fabbrica of Orvieto cathedral from 1500 to 1501. The unusual medium and the inscription suggest that this portrait was possibly meant as a personal souvenir for the camerarius to mark the completion of the project in the chapel.

Quoted From: Self-Portrait with Niccolò d'Angeli Franceschi 1500 or 1503

Luca Signorelli was noted in particular for his ability as a draughtsman and his use of foreshortening. His massive frescoes of the Last Judgment (1499-1503) in Orvieto Cathedral are considered his masterpiece.

He was born Luca d'Egidio di Ventura in Cortona, Tuscany (some sources call him Luca da Cortona). The precise date of his birth is uncertain; birth dates of 1441-1445 are proposed. He died in 1523 in Cortona, where he is buried. He was perhaps eighty-two years old. He is considered to be part of the Tuscan school, although he also worked extensively in Umbria and Rome.

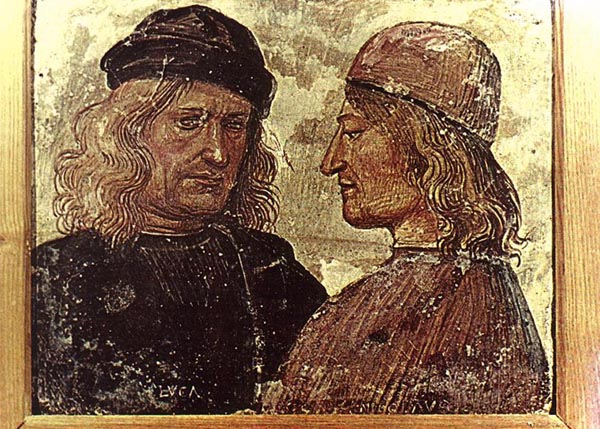

His first impressions of art seem to be due to Perugia - the style of Benedetto Bonfigli, Fiorenzo di Lorenzo and Pinturicchio. Lazzaro Vasari, the great-grandfather of art historian Giorgio Vasari, was brother to Luca's mother; according to Giorgio Vasari he got Luca apprenticed to Piero della Francesca. In 1472 the young man was painting at Arezzo, and in 1474 at Città di Castello. He presented to Lorenzo de' Medici a picture which is probably the one named the School of Pan. Janet Ross and her husband Henry discovered the painting in Florence circa 1870 and subsequently sold it to the Kaiser Frederick Museum in Berlin. The painting was destroyed by allied bombs in WWII. See Benjamin, Sarah (2006) A Castle in Tuscany at 63-67 (image of the painting at 64-65) Murdoch Books Australia. The painting's subject is almost the same which he painted also on the wall of the Petrucci palace in Siena-the principal figures being Pan himself, Olympus, Echo, a man reclining on the ground and two listening shepherds.

(Luca Signorelli, The School of Pan, formerly Berlin, presumably destroyed in Flakturm fire)

He executed, moreover, various sacred pictures, showing a study of Botticelli and Lippo Lippi. Pope Sixtus IV commissioned Signorelli to paint some frescoes, now mostly very dim, in the shrine of Loreto-Angels, Doctors of the Church, Evangelists, Apostles, the Incredulity of Thomas and the Conversion of Saint Paul. He also executed a single fresco in the Sistine Chapel in Rome, the Testament and Death of Moses, although most of it has been attributed to Bartolomeo della Gatta; another, the Moses Leaving to Egypt, once ascribed to Signorelli, is now recognized as the work of Perugino and other assistants.

Signorelli worked in Rome from 1478 to 1484. In the latter year he returned to his native Cortona, which remained from this time his home. In the Monastery of Monte Oliveto Maggiore (Siena) he painted eight frescoes, forming part of a vast series of the life of Saint Benedict; they are at present in poor condition. In the palace of Pandolfo Petrucci he worked upon various classic or mythological subjects, including the School of Pan already mentioned.

Work in Orvieto

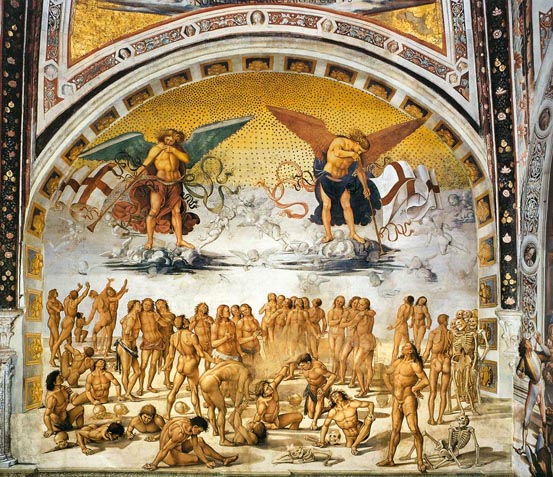

From the Monastery of Monte Oliveto Maggiore near Siena, Signorelli went to Orvieto, and produced his masterpiece, the frescoes in the chapel of Saint Brizio (then called the Cappella Nuova), in the cathedral.

The Cappella Nuova already contained two groups of images in the vaulting over the altar, the Judging Christ and the Prophets, by Fra Angelico, who had begun the murals fifty years earlier. The works of Signorelli in the vaults and on the upper walls represent the events surrounding the Apocalypse and the Last Judgment. The events of the Apocalypse fill the space which surrounds the entrance into the large chapel.

(Posthumous portrait of Fra Angelico by Luca Signorelli,

detail from Deeds of the Antichrist fresco (ca 1501)

in Orvieto Cathedral, Italy.)

The Apocalyptic events begin with the Preaching of Antichrist, and proceed to the Doomsday and The Resurrection of the Flesh. They occupy three vast lunettes, each of them a single continuous narrative composition. In one of them, Antichrist, after his portents and impious glories, falls headlong from the sky, crashing down into an innumerable crowd of men and women.

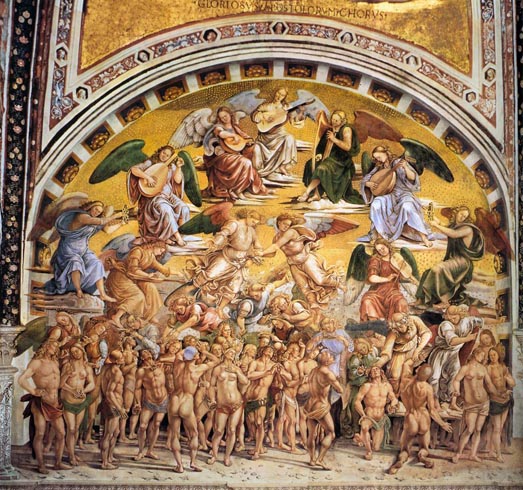

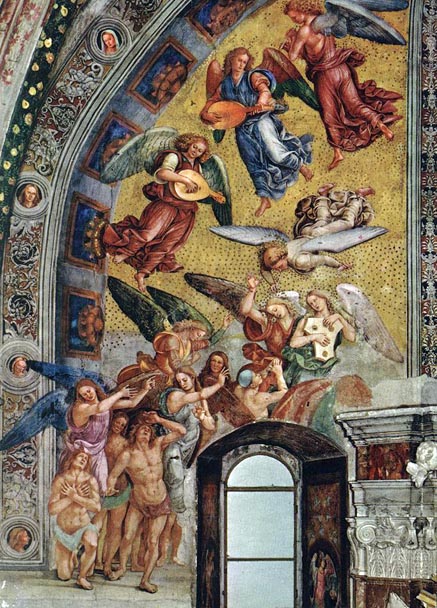

The events of the Last Judgment fill the facing vault and the walls around the altar: Paradise, the Elect and the Condemned, Hell, the Resurrection of the Dead, and the Destruction of the Reprobate.

To Angelico's ceiling, which contained the Judging Christ and the Prophets led by John the Baptist, Signorelli added the Madonna leading the Apostles, the Patriarchs, Doctors of the Church, Martyrs, and Virgins. The unifying factor of the paintings is found in the scripture readings in the Roman liturgies for the Feast of All Saints and Advent.

Stylistically, the daring and terrible inventions, with their powerful treatment of the nude and arduous foreshortenings, were striking in its day. Michelangelo is claimed to have borrowed, in his own fresco at the Sistine Chapel wall, some of Signorelli's figures or combinations. The decoration of the lower walls, unprecedented in the history of art, is richly decorated with a great deal of subsidiary work connected with Dante, specifically the first eleven books of his Purgatorio, and with the poets and legends of antiquity. A Pietà composition in a niche in the lower wall contains explicit references to two important Orvietan martyr saints, Saint Pietro Parenzo and Saint Faustino, in the centuries preceding the execution of the lunette paintings.

The contract for Signorelli's work is still on record in the archives of the Cathedral of Orvieto. He undertook on April 5, 1499 to complete the ceiling for 200 ducats, and to paint the walls for 600, along with lodging, and in every month two measures of wine and two quarters of corn. The contract directed Signorelli to consult the Masters of the Sacred Page for theological matters. This is the first such recorded instance of an artist receiving theological advice, although art historians believe the two groups routinely discussed such matters. Signorelli's first stay in Orvieto lasted not more than two years. In 1502 he returned to Cortona. He returned to Orvieto and continued the lower walls. He painted a dead Christ, with Mary Magdalen and the Virgin Mary and the martyrs local Saints Pietro Parenzo and Faustino. The figure of the dead Christ, according to Vasari, is the image of Signorelli's son Antonio, who died from the plague during the course of the execution of the paintings.

Work in Siena, Cortona, Rome, and Arezzo

After finishing the frescoes at Orvieto, Signorelli was often in Siena. In 1507 he executed a great altarpiece for Saint Medardo at Arcevia in the Marche, the Madonna and Child, with the Massacre of the Innocents and other episodes.

In 1508 Pope Julius II summoned artists to Rome, including Signorelli, Perugino, Pinturicchio and Il Sodoma to paint the large rooms in the Vatican Palace. They began work, but soon the pope dismissed all to make way for Raphael. Their work was taken down, except for the ceiling in the Stanza della Segnatura. Luca returned to Siena, but mostly lived in his hometown of Cortona. He constantly was at work, but the performances of his closing years were not of the quality of his works from 1490-1505.

In 1520 Signorelli went with one of his pictures to Arezzo. He was partially paralyzed when he began a fresco of the Baptism of Christ in the chapel of Cardinal Passerini's palace near Cortona, which (or else a Coronation of the Virgin at Foiano) is the last picture of his specified. Signorelli stood in great repute as a citizen. He entered the magistracy of Cortona as early as 1488, and held a leading position by 1524 when he died.

Signorelli paid great attention to anatomy. It is said that he carried on his studies in burial grounds. Certainly his mastery of the human form indicates that he had performed dissections. He surpassed contemporaries in showing-the structure and mechanism of the nude in immediate action; and he even went beyond nature in experiments of this kind, trying hypothetical attitudes and combinations. His drawings in the Louvre demonstrate this and bear a close analogy to the method of Michelangelo. He aimed at powerful truth rather than nobility of form; color was comparatively neglected, and his chiaroscuro exhibits sharp oppositions of lights and shadows. He had a vast influence over the painters of his own and of succeeding times, but had no pupils or assistants of high mark; one of them was a nephew named Francesco.

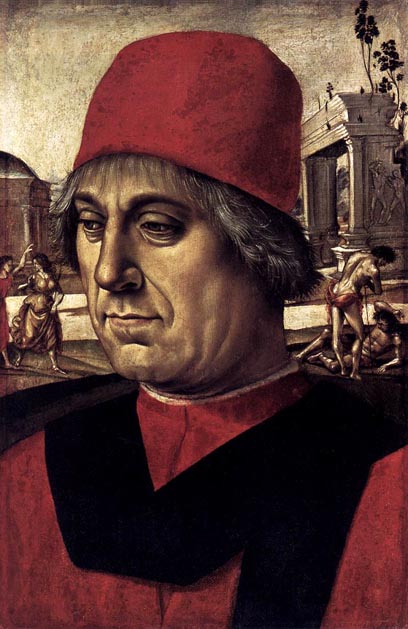

Vasari, who claimed Signorelli as a relative, described him as kindly, a family man, and said that he always lived more like a nobleman than a painter. Vasari included Signorelli's portrait, one of seven, in his study in Arezzo, along with Michelangelo and himself. The Torrigiani Gallery in Florence contains a grand life-sized portrait by Signorelli of a man in a red cap and vest, and corresponds with Vasari's observation. In the National Gallery, London, are the Circumcision of Jesus and three other works. Legend holds that Signorelli depicted himself in the left foreground of his Orvietan mural The Rule of Antichrist. Fra Angelico, his predecessor in the Orvieto cycle, is thought to stand behind him in the piece. However, the figure thought to be Fra Angelico is not dressed as a Dominican friar, and Signorelli's supposed portrait does not match that in Vasari's study.

Quoted From: Luca Signorelli - Wikipedia

Additional Sources:

Fresco Cycle in the San Brizio Chapel, Cathedral, Orvieto

by Luca Signorelli

Luca Signorelli, on 5 April 1499, signed a contract with Orvieto Cathedral: he was to paint the two remaining sections of the ceiling of the Chapel of San Brizio, a large Gothic construction built around 1408. In the summer of 1447 Fra Angelico, assisted by Gozzoli and several other minor artists, had painted a fresco of the Prophets in one of the triangular ceiling vanes and Christ the Judge in another. Half a century later Signorelli's task was to complete the fresco decoration begun by Angelico. The administrators of the Cathedral had asked other artists before Signorelli, including Perugino and Antonio da Viterbo, called Il Pastura. They finally decided to hire Luca both because he had asked for less money and because he had a reputation for being more efficient and faster than other artists. The contract refers to him as the artist who had painted 'multas pulcherrimas picturas in diversis civitatibus et presentim Senis' (many beautiful paintings in different cities and especially in Siena).

Signorelli respected the terms of the contract and worked at such a speed that even the Cathedral administrators must have been surprised. A year after the contract was signed, on 23 April 1500, the ceiling frescoes were finished and he was able to show his patrons his drawings for the side wall frescoes. The contract for these further paintings was signed a few days, later: he was to be paid 575 ducats for this second part. In 1502 the fresco cycle was certainly finished, although further payments to Signorelli are recorded as late as 1504.

In only three years, from 1499 to 1502, the decoration was planned and executed, with a speed and efficiency that is practically unique in the history of Italian art. As far as the subject matter is concerned, it is one of the most important subjects of Christian iconography. It is likely that for the ceiling frescoes (the groups of Apostles, Angels, Prophets, Patriarchs, and Doctors of the Church, Martyrs and Virgins) Signorelli simply completed the programme that had originally been devised by Fra Angelico. But the frescoes on the side walls, although the basic subject would have been planned in accordance with the Cathedral's administrators and theologians, are wholly the product of Signorelli's fertile imagination. The side walls are covered with seven large scenes:

The Sermon and Deeds of the Antichrist

The Destruction of the World

The Resurrection of the Flesh

The Damned

The Elect

The Paradise

The Hell

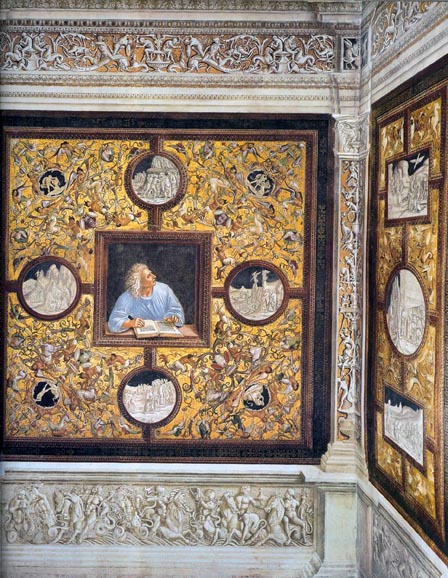

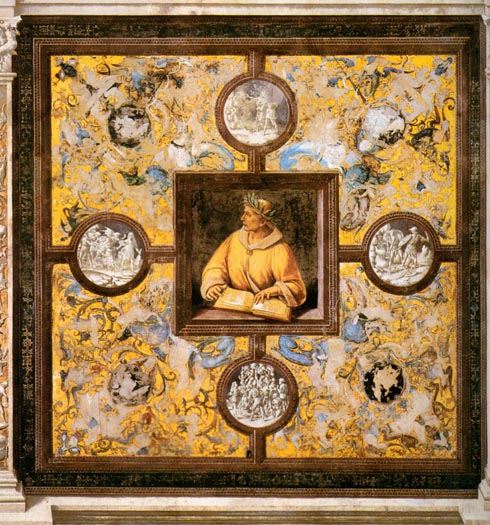

The lower part of the walls is decorated with grotesque patterns and with busts of philosophers and poets alongside monochromes commenting their works, as well as illustrations from the Divine Comedy. The overall decoration is completed in the jambs of the windows and in the small chapel on the far wall by the figures of Archangels Raphael (with Tobias), Gabriel and Michael (weighing souls and subjugating the devil), by Bishop Saints Brizio and Constant, and the Lamentation over the Dead Christ with Saints Parenzo and Faustino.

Quoted From: Fresco Cycle in the San Brizio Chapel, Cathedral, Orvieto

Preview

View of the Chapel of San Brizio: 1499-1502

The picture presents a view from the right-side aisle of Orvieto cathedral into the Chapel of San Brizio, showing the choir stalls removed during the restoration of 1996.

Quoted From: View of the Chapel of San Brizio 1499-1502

View of the Frescoes in the Chapel of San Brizio: 1499-1502

The picture shows a view of the frescoes in the Brizio Chapel of the Duomo at Orvieto. The figures seen in the vaults show the blessed in heaven as part of a panoramic Last Judgment began in the chapel by Fra Angelico in 1447 but left incomplete.

Quoted From: View of the Frescoes in the Chapel of San Brizio 1499-1502

Frescoes in the Chapel of San Brizio: 1499-1502

The picture presents a view of the Chapel of San Brizio from the entry toward the altar wall and the vaulting. On the side walls, the preaching and deeds of the Antichrist and the joys of the chosen in paradise (left), the resurrection of the flesh and the tortures of the damned in hell (right) can be seen. In the first bay of the vaulting, painted by Signorelli, are virgins, patriarchs, martyrs, and Church fathers.

The side walls are covered with seven large scenes:

The Sermon and Deeds of the Antichrist

The Destruction of the World The Resurrection of the Flesh The Damned The Elect The Paradise The HellThe ceiling frescoes (the groups of Apostles, Angels, Patriarchs, and Doctors of the Church, Martyrs and Virgins) had been devised by Fra Angelico. The lower part of the walls is decorated with grotesque patterns and with busts of philosophers and poets alongside monochromes commenting their works, as well as illustrations from the Divine Comedy. The overall decoration is completed in the jambs of the windows and in the small chapel on the far wall by the figures of Archangels Raphael (with Tobias), Gabriel and Michael (weighing souls and subjugating the devil), by Bishop Saints Brizio and Constant, and the Lamentation over the Dead Christ with Saints Parenzo and Faustino.

Quoted From: Frescoes in the Chapel of San Brizio 1499-1502

Sermon and Deeds of the Antichrist; Apocalypse

by Luca Signorelli

Sermon and Deeds of the Antichrist: 1499-1502

It is quite likely that the Deeds of the Antichrist is intended as a reference to Savonarola, the Dominican friar hanged and burnt at the stake in Florence on 23 May 1498. In a 'Papist' city like Urbino, and in the case of an artist like Signorelli who had been a Medici protégé and who thought of himself basically as a victim of persecution from the Florentine democratic government (a fact we learn from Michelangelo), this identification of Savonarola with the Antichrist is very plausible; it is also supported by a famous passage in Marsilio Ficino's Apologia, published in 1498, where the Ferrarese monk is again identified as the false prophet.

There is no doubt that Signorelli has given us a very convincing portrayal of the sinister and mysterious atmosphere evoked in the prophecies of the Gospels in the huge fresco showing the Sermon and Deeds of the Antichrist. Against a vast and desolate background, dominated on the right by an unusually large classical building, depicted in distorted perspective, the false prophet is shown disseminating his lies and spreading his message of destruction. He has the features of Christ, but it is Satan (portrayed behind him) who tells him what to say. The people around him, who have piled up gifts at the foot of his throne, have clearly already been corrupted by the iniquities the Gospel has warned us of. And, starting from the left, we have a description of a brutal massacre, followed by a young woman selling her body to an old merchant, and then more aggressive and evil-looking men. In the background of this scene all sorts of horrors and miraculous events are taking place. The Antichrist orders people to be executed and even resurrect a man, while a group of clerics, huddled together like a fortified citadel, resist the devil's temptations by praying. Lastly, to the left, Signorelli shows us how the age of the Antichrist is rapidly reaching its inevitable epilogue, with the false prophet being hurled down from the heavens by the Angel and all his followers being defeated and destroyed by the wrath of God. That this scene is the masterpiece of the whole cycle (at least in terms of originality of invention and evocation of fantastic imagery) even Signorelli himself must have realized, and he has placed himself, together with a monk (traditionally identified as Fra Angelico) on the left-hand side of the composition.Quoted From: Sermon and Deeds of the Antichrist 1499-1502

Sermon and Deeds of the Antichrist (Detail): 1499-1502

_1499_1502_1.jpg)

That this scene is the masterpiece of the whole cycle (at least in terms of originality of invention and evocation of fantastic imagery) even Signorelli himself must have realized, and he has placed himself, together with a monk (traditionally identified as Fra Angelico) on the left-hand side of the composition. Wearing a black cap and cloak, as was suitable for a respected artist, an attractive and elegantly dressed man in his fifties as Vasari describes him, Luca Signorelli really looks like a director so pleased with himself for the success of his theatrical representation that he stands on stage for his deserved curtain call (Scarpellini).

Quoted From: Sermon and Deeds of the Antichrist (Detail) 1499-1502

Sermon and Deeds of the Antichrist (Detail): 1499-1502

_1499_1502_2.jpg)

The detail shows the self-portrait and the portrait of Fra Angelico.

Quoted From: Sermon and Deeds of the Antichrist (Detail) 1499-1502

Sermon and Deeds of the Antichrist (Detail): 1499-1502

_1499_1502_3.jpg)

The false prophet is shown disseminating his lies and spreading his message of destruction. He has the features of Christ, but it is Satan (portrayed behind him) who tells him what to say. The people around him, who have piled up gifts at the foot of his throne, have clearly already been corrupted by the iniquities the Gospel has warned us of.

Quoted From: Sermon and Deeds of the Antichrist (Detail) 1499-1502

Sermon and Deeds of the Antichrist (detail): 1499-1502

_1499_1502_4.jpg)

The detail shows a young woman selling her body to an old merchant.

Quoted From: Sermon and Deeds of the Antichrist (Detail) 1499-1502

Apocalypse: 1499-1502

According to the prediction in the Scriptures, the deeds of the Antichrist take place immediately before the end of the world, in those last days when 'the sun shall be darkened, and the moon shall not give her light, and the stars of heaven shall fall, and the powers that are in heaven shall be shaken' (Mark, 13: 24-25).

For his description of the end of the world the artist had to make do with the narrow spaces on either side of the entrance door to the chapel. He was thus forced to divide the scene into two narrative sections. To the right he describes the first signs of the 'Apocalypse', which has been the object of prophecies since earliest times. In the foreground, in the lower part of the painting, he has shown King David and the Sibyl, as witnesses of 'Dies Irae'. The stars go pale, fires and earthquakes sweep the earth, war and murder spread throughout the world. The left-hand section recounts the epilogue of this preannounced catastrophe. Demons looking like monstrous bats soar through the darkened sky, showering earth with flaming arrows; the last survivors fall under their shots, piling up on top of each other like broken dolls.

Quoted From: Apocalypse 1499-1502

Apocalypse (Detail): 1499-1502

_1499_1502_1.jpg)

The picture shows the left-hand section of the frescoes on the entry wall. This section recounts the epilogue of this preannounced catastrophe. Demons looking like monstrous bats soar through the darkened sky, showering earth with flaming arrows; the last survivors fall under their shots, piling up on top of each other like broken dolls.

Quoted From: Apocalypse (Detail) 1499-1502

Apocalypse (Detail): 1499-1502

_1499_1502_2.jpg)

The picture shows the right-hand section of the frescoes on the entry wall. Here the painter describes the first signs of the Apocalypse, which has been the object of prophecies since earliest times. In the foreground, in the lower part of the painting, he has shown King David and the Sibyl, as witnesses of Dies Irae. The stars go pale, fires and earthquakes sweep the earth, war and murder spread throughout the world.

Quoted From: Apocalypse (Detail) 1499-1502

Apocalypse (Detail): 1499-1502

_1499_1502_3.jpg)

The detail shows the lower left part of the fresco.

The left-hand section recounts the epilogue of this preannounced catastrophe. In the lower part the last survivors fall under the shots of the demons, piling up on top of each other like broken dolls.

Quoted From: Apocalypse (Detail) 1499-1502

Apocalypse (Detail): 1499-1502

_1499_1502_4.jpg)

The detail shows the lower right part of the fresco.

In the right section of the Apocalypse Luca Signorelli describes the first signs of the Apocalypse, which has been the object of prophecies since earliest times. In the foreground, in the lower part of the painting, he has shown King David and the Sibyl, as witnesses of Dies Irae. The stars go pale, fires and earthquakes sweep the earth, war and murder spread throughout the world.

Quoted From: Apocalypse (Detail) 1499-1502

Apocalypse (Detail): 1499-1502

_1499_1502_5.jpg)

The picture shows a detail of the upper left part of the fresco.

Demons looking like monstrous bats soar through the darkened sky, showering earth with flaming arrows.

Quoted From: Apocalypse (Detail) 1499-1502

Resurrection of the Flesh

by Luca Signorelli

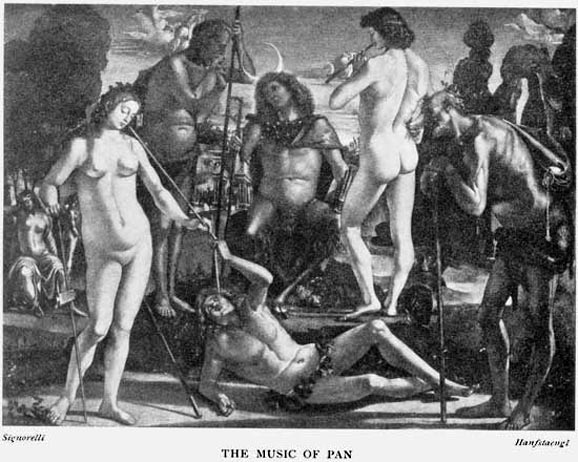

Resurrection of the Flesh: 1499-1502

This fresco is located in the first compartment on the right wall.

The account of the Apocalypse then continues with three large scenes, the Resurrection of the Flesh, the Damned and the Elect, and two smaller ones on either side of the chapel's window, Paradise and Hell. It is primarily in this section of the fresco cycle that Signorelli has given free rein to his inventive genius. An inventiveness that, as Berenson said made him one of the greatest of modern illustrators, and thanks to which his art is still an extremely important part of our figurative heritage. Despite the rhetorical devices, the theatrical ruses and the occasional contrived details, despite the limitations in his draftsmanship and use of color recognized by all modern critics, there is no denying that never before in Italian art had figurative ideas of such unforgettable power been used. Viewed all together the huge frescoes in the Orvieto chapel give an impression of overcrowding and of confusion which is far from pleasing. We have to isolate the individual details in order to grasp the greatness of Signorelli the 'illustrator' and the 'inventor' and therefore justify Berenson's statement. See, for example, in the Resurrection of the Flesh, the macabre but hilarious idea of the nude with his back to the observer who is carrying on a conversation with the skeletons; or the skulls surfacing through the cracks in the ground who put on their bodies as though they were a costume, and become human beings once again.Quoted From: Resurrection of the Flesh 1499-1502

The Damned and The Elect

by Luca Signorelli

The Damned: 1499-1502

The account of the Apocalypse continues with three large scenes, the Resurrection of the Flesh, the Damned and the Elect, and two smaller ones on either side of the chapel's window, Paradise and Hell.

It is primarily in this section of the fresco cycle that Signorelli has given free rein to his inventive genius. An inventiveness that, as Berenson said, made him one of the greatest of modern illustrators, and thanks to which his art is still an extremely important part of our figurative heritage. Despite the rhetorical devices, the theatrical ruses and the occasional contrived details, despite the limitations in his draftsmanship and use of colour recognized by all modern critics, there is no denying that never before in Italian art had figurative ideas of such unforgettable power been used. Viewed all together the huge frescoes in the Orvieto chapel give an impression of overcrowding and of confusion which is far from pleasing. We have to isolate the individual details in order to grasp the greatness of Signorelli the 'illustrator' and the 'inventor' and therefore justify Berenson's statement. Signorelli's fresco cycle in Orvieto is full of humor, grotesque inventions, erotic allusions and ribald jokes. There is no need to refer to the profane spirit of the Renaissance to explain this. On the contrary, these scenes fit in very well with the idea of the Cathedral as theatrum mundi, as the mirror image of the whole universe, and they are fully in the spirit of the religious plays of the time. Basically, neither Signorelli nor his patrons wanted to do without the enjoyment provided by story-telling, a typically Italian style based on humorous and imaginative details. But this in no way invalidates the dogmatic truth of the prophecies relating to the end of the world, which, especially in those turbulent years, really came across as a terrifying threat. It becomes quite understandable that Michelangelo would have been really interested in these Orvieto frescoes. But he in no way imitated Luca's work , (as Vasari would have us believe), for the spirituality and the moral content of the Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel have absolutely nothing in common with the theatrical representation in Orvieto. Michelangelo perhaps found in Signorelli's frescoes a useful iconographical repertory, a catalogue of surprising and unusual inventions. In any case the parts of the fresco cycle that would have attracted Michelangelo's curiosity most would certainly have been the scenes with devils and other imaginary figures, those scenes that were best suited to Signorelli's eccentric temperament, to his irony and macabre humor.Quoted From: The Damned 1499-1502

The Damned (Detail): 1499-1502

_1499_1502_1.jpg)

The Damned (Detail): 1499-1502

_1499_1502_2.jpg)

We have to isolate the individual details in order to grasp the greatness of Signorelli the 'illustrator' and the 'inventor'. For example, in this detail, the beautiful naked woman lying on the ground, screaming in fear of the terrible punishment that lies in store for her at the hands of the devil who has captured her and is now towering over her from behind, as strong and powerful as a Roman gladiator.

Quoted From: The Damned (Detail) 1499-1502

The Damned (Detail): 1499-1502

_1499_1502_3.jpg)

The Damned (Detail): 1499-1502

_1499_1502_4.jpg)

We have to isolate the individual details in order to grasp the greatness of Signorelli the 'illustrator' and the 'inventor'. For example, in this picture, the justly famous detail of the flying devil carrying off a young girl and turning around, with a broad, satisfied grin on his face.

Quoted From: The Damned (Detail) 1499-1502

The Damned (Detail): 1499-1502

_1499_1502_5.jpg)

We have to isolate the individual details in order to grasp the greatness of Signorelli the 'illustrator' and the 'inventor'. For example, in this detail, the demon attacking a young woman from behind, biting her ear, and she does not appear to mind all that much.

And Luca Signorelli has portrayed himself as a devil, too: with just one horn in the middle of his forehead, he is embracing a beautiful blonde who is trying to break away from his fiery assault. One can't help imagining that this rather unusual self-portrait must be a reference to some episode in Signorelli's private life, something that we know nothing about, but which must have been public knowledge in both Cortona and Orvieto at the time. Probably the story of a woman who was unfaithful to the painter: and in fact, if we look carefully we can see that this is the same woman portrayed as the sinner being carried off by the flying demon, as the woman being grabbed from behind by the other demon, and even as the prostitute being paid by the old merchant in the scene of the Antichrist's Sermon.Quoted From: The Damned (Detail) 1499-1502

The Damned (Detail): 1499-1502

_1499_1502_6.jpg)

The Damned (Detail): 1499-1502

_1499_1502_7.jpg)

The detail shows a group of devils and damned souls.

Quoted From: The Damned (Detail) 1499-1502

The Elect: 1499-1502

There is no doubt that Luca Signorelli's portrayal of the Elect is far less convincing than his fresco of the Damned. Despite his extremely accurate studies of the human body, his depiction of Paradise is no more than a conventional catalogue of good sentiments and the overall effect is one of unmitigated dullness. The same is true of the pair of frescoes depicting the Elect being called to Paradise and the Damned being plunged into Hell.

Quoted From: The Elect 1499-1502

The Elect (Detail): 1499-1502

_1499_1502_1.jpg)

The Elect (Detail): 1499-1502

_1499_1502_2.jpg)

The Elect Being Called to Paradise and the Damned Being Plunged into Hell

by Luca Signorelli

The Elect Being Called to Paradise and The Damned Being Plunged into Hell: 1499-1502

The picture shows the frescoes on the altar wall of the chapel: The Elect Being Called to Paradise (left) and The Damned Being Plunged into Hell (right). In the window embrasures are angels and Saints Brizio and Constantius, while in the tondi of the side window embrasures, the archangel Michael and a demon (left) and the archangel Raphael with Tobias (right).

There is no doubt that Luca's portrayal of the Elect is far less convincing than his fresco of the Damned. Despite his extremely accurate studies of the human body, his depiction of Paradise is no more than a conventional catalogue of good sentiments and the overall effect is one of unmitigated dullness. The same is true of the pair of frescoes depicting the Elect being called to Paradise and the Damned being plunged into Hell. Although each covers a half wall interrupted by an arch, the scene of the blessed being summoned to heaven is unimaginative and common-place, with its pretty musician angels and chocolate-box portrayals of the Elect. Whereas the scene of the Damned is constructed around the visionary, almost surrealistic, idea of these crowds of naked figures jostling for space along the banks of the Acheron, and the splendid group in the foreground of the devil whipping a terrified, screaming sinner (reminiscent of a Pollaiolo figure). Michelangelo was clearly fascinated by this powerful scene of cruelty and did a drawing of it.Quoted From: The Elect Being Called to Paradise and The Damned Being Plunged into Hell 1499-1502

The Elect Being Called to Paradise: 1499-1502

In this scene nine angels show to the blessed the way to Heaven.

Quoted From: The Elect Being Called to Paradise 1499-1502

The Damned Being Plunged into Hell: 1499-1502

The scene of the Damned is constructed around the visionary, almost surrealistic, idea of these crowds of naked figures jostling for space along the banks of the Acheron.

In this representation, at the foot of two big mountains, along the shore of the Acheron, a devil with a white banner leads a group of damned. Other damned are in despair since they see Charon's boat getting near. Below there is Minos punishing a damned man. Above, two angels, one wearing a breast-plate and the other covered with veils, are watching the scene.Quoted From: The Damned Being Plunged into Hell 1499-1502

The Damned Being Plunged into Hell (Detail): 1499-1502

_1499_1502_1.jpg)

The scene of the Damned is constructed around the visionary, almost surrealistic, idea of these crowds of naked figures jostling for space along the banks of the Acheron. A devil with a white banner leads a group of damned. Other damned are in despair since they see Charon's boat getting near.

Quoted From: The Damned Being Plunged into Hell (Detail) 1499-1502

The Damned Being Plunged into Hell (Detail): 1499-1502

_1499_1502_2.jpg)

The splendid group in the foreground depicts the devil whipping a terrified, screaming sinner (reminiscent of a Pollaiolo figure). Michelangelo was clearly fascinated by this powerful scene of cruelty and did a drawing of it.

Quoted From: The Damned Being Plunged into Hell (Detail) 1499-1502

Frescoes on the Vault and Decoration

by Luca Signorelli

Borrowing a decoration programme that had already been used in 1494 by Pinturicchio in the Borgia Apartment in Rome, Signorelli decided to decorate the area below his frescoes with grotesque ornamental motifs, busts of philosophers and poets, as well as monochromes illustrating their work. It is possible that the busts of philosophers and poets are intended as symbols of reason and moral values, the only instruments that man can use to keep in check the powerful animal instincts of his nature and to attain the higher spheres of the spirit.

But one thing is certain: this apparently minor section, which was painted to a large extent by Signorelli's assistants, contains fascinating inventions and reaches extraordinary heights of expression. The artist gives free rein to his imagination in these grotesques, and the result is comparable only to the scenes that Filippino Lippi was painting at about the same time in the Strozzi Chapel in the church of Santa Maria Novella in Florence.Quoted From: Frescoes on the Vault and Decoration

Dante Alighieri: 1499-1502

Borrowing a decoration programme that had already been used in 1494 by Pinturicchio in the Borgia Apartment in Rome, Signorelli decided to decorate the area below his frescoes with grotesque ornamental motifs, busts of philosophers and poets, as well as monochromes illustrating their work. It is possible that the busts of philosophers and poets are intended as symbols of reason and moral values, the only instruments that man can use to keep in check the powerful animal instincts of his nature and to attain the higher spheres of the spirit.

But one thing is certain: this apparently minor section, which was painted to a large extent by Signorelli's assistants, contains fascinating inventions and reaches extraordinary heights of expression. The artist gives free rein to his imagination in these grotesques, and the result is comparable only to the scenes that Filippino Lippi was painting at about the same time in the Strozzi Chapel in the church of Santa Maria Novella in Florence. The only one of philosophers and poets that can be identified with certainty is Dante Alighieri, and some of the loveliest and most famous of the monochromes are illustrations of episodes from the Divine Comedy, for the most part from Purgatory.Quoted From: Dante Alighieri 1499-1502

Statius: 1499-1502

The picture shows the Roman Poet Statius.

If we look carefully at the anthropomorphic decorations, crowded with naked bodies in an incredible variety of poses, or the convulsive violence that runs through some of the foliage patterns or the groups of tritons and naiads like an electric current, we can really begin to understand Signorelli's great ability as a draughtsman, a talent that is further confirmed by his drawing production.

Quoted From: Statius 1499-1502

Empedocles: 1499-1502

The picture shows the wainscoting to the right of the entry. In the tondo a young man wearing turban, identified as Empedocles, a Greek philosopher (ca. 490-430 BC), leans out of the window to watch the Apocalypse. On a small tablet set in among the grotesques, the painter's initials "LS" can be seen.

If we look carefully at the anthropomorphic decorations, crowded with naked bodies in an incredible variety of poses, or the convulsive violence (that Scarpellini has compared to action painting) that runs through some of the foliage patterns or the groups of tritons and naiads like an electric current, we can really begin to understand Signorelli's great ability as a draughtsman, a talent that is further confirmed by his drawing production.Quoted From: Empedocles 1499-1502

Claudian: 1499-1502

The picture shows the Roman Poet Claudian.

The picture shows an additional poet portrait from the wainscoting panels.

Quoted From: Claudian 1499-1502

Ovid: 1499-1502

This picture shows the Roman Poet Ovid

The picture shows an additional poet portrait from the wainscoting panels.

Quoted From: Ovid 1499-1502

Sallust: 1499-1502

This picture shows the Roman Historian and Politician Sallust.

The picture shows an additional poet portrait from the wainscoting panels. The portrait of Sallust is cut off by the framing of the side chapel.

Quoted From: Sallust 1499-1502

Tibullus: 1499-1502

This picture shows the Roman Poet Tibullus.

TIBVLLI ALIORVMQUE CARMINVM LIBRI TRES

from the Latin Library.

The picture shows an additional poet portrait from the wainscoting panels. The portrait of Tibullus is cut off by the framing of the side chapel.

Quoted From: Tibullus 1499-1502

Dante and Virgil Entering Purgatory: 1499-1502

The only one of the busts of philosophers and poets that can be identified with certainty is Dante Alighieri, and some of the loveliest and most famous of the monochromes are illustrations of episodes from the Divine Comedy - for the most part from Purgatory. In these Orvieto frescoes Signorelli proves that he is a talented illustrator of Dante, but what is truly fascinating is that he has succeeded in giving an interpretation of the Divine Comedy that is evocative and visionary, so similar to more modern styles that one can't help but compare it to the work of such artists as Fuseli, Blake, Gustave Doré. If one is still searching for evidence of Luca Signorelli's inventive genius and of his astonishing versatility, then these decorations will provide it.

The decorative scheme is the following:

The series begins below the fresco of the Antichrist, with Homer and three episodes of Iliad. Below the Apocalypse Empedocles, the philosopher of Agrigento, who leans out to watch the scenes of his prophecy. The series of the poet goes on below the painting of the Resurrection, where Lucan is represented, with two scenes of Pharsalia (The slaughter of the Pompeians and the murder of Pompey).

DE BELLO CIVILI SIVE PHARSALIA

from the Latin Library.

The figure of Horace is surrounded by four medallions, in which some stories taken from Hades are narrated. It seems that Ovid - in the following panel - is speaking to an invisible interlocutor. The four scenes represent episodes of the Metamorphoses. Virgil looks amazed at the scene of the Damned. Dante - with some scenes taken from the first two cantos of Purgatory - is working. Other two medallions represent the martyrdom of Saint Faustine and Saint Peter Parenzo killed by the heretics of Orvieto (1190).

This picture shows Dante and Virgil Entering Purgatory.

Quoted From: Dante and Virgil Entering Purgatory

The Angel Arrives in Purgatory: 1499-1502

The only one of the busts of philosophers and poets that can be identified with certainty is Dante Alighieri, and some of the loveliest and most famous of the monochromes are illustrations of episodes from the Divine Comedy - for the most part from Purgatory. In these Orvieto frescoes Signorelli proves that he is a talented illustrator of Dante, but what is truly fascinating is that he has succeeded in giving an interpretation of the Divine Comedy that is evocative and visionary, so similar to more modern styles that one can't help but compare it to the work of such artists as Fuseli, Blake, Gustave Doré. If one is still searching for evidence of Luca Signorelli's inventive genius and of his astonishing versatility, then these decorations will provide it.

This picture shows The Angel Arrives in Purgatory.Quoted From: The Angel Arrives in Purgatory 1499-1502

Fresco Fragment: 1499-1502

The man lying on the ground and biting his hand in the badly damaged fragment on the altar walls thought to represent Cain. In fact, biting one's hand is a traditional symbol of envy, one of Cain's seven sins. In the medallion of the grotesque decor below, a murder scene with Triton-like creatures is depicted. Here the murder weapon is the jawbone of an ass, the one used by Cain in killing his brother Abel.

This fresco fragment was discovered during a recent restoration.

Quoted From: Fresco Fragment 1499-1502

Ceiling Frescoes in the Chapel of San Brizio: 1499-1502

The picture shows the vaulting of the Chapel of San Brizio. The frescoes were begun by Fra Angelico and completed by Luca Signorelli. Above the altar wall is Christ as World Judge flanked by prophets led by John the Baptist (right) and apostles with the Virgin (left).

Quoted From: Ceiling Frescoes in the Chapel of San Brizio 1499-1502

Choir of Patriarchs: 1499-1502

This fresco was painted by Luca Signorelli following the pattern set by Fra Angelico.

Quoted From: Choir of Patriarchs: 1499-1502

Doctors of the Church: 1499-1502

It is likely that for the ceiling frescoes (the groups of Apostles, Angels, Patriarchs, Doctors of the Church, Martyrs and Virgins) Signorelli simply completed the programme that had originally been devised by Fra Angelico.

Quoted From: Doctors of the Church 1499-1502

The Virgins: 1499-1502

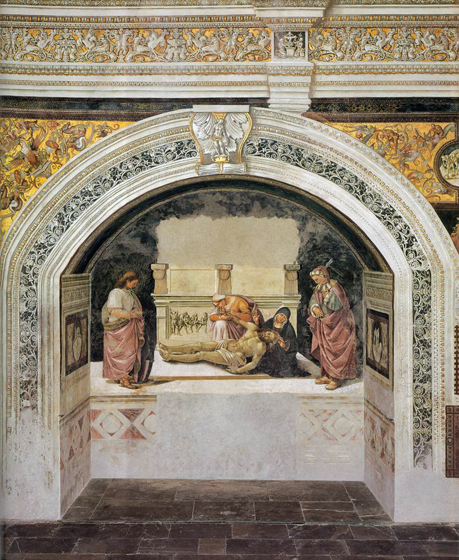

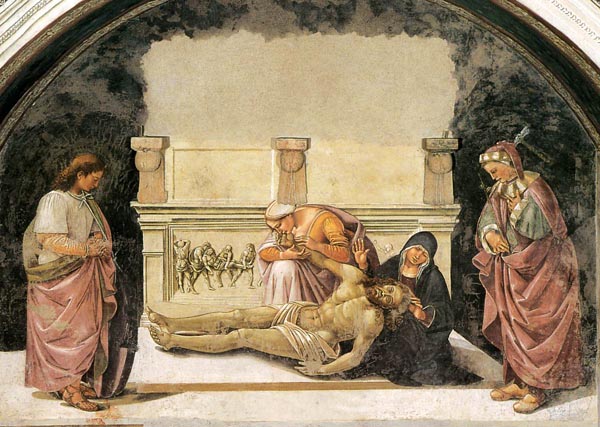

Cappellina dei Corpi Santi: 1499-1502

Luca Signorelli completed the overall decoration of the Chapel of San Brizio in the small chapel on the far wall by the figures of Archangels Raphael (with Tobias), Gabriel and Michael (weighing souls and subjugating the devil), by Bishop Saints Brizio and Constant, and the Lamentation over the Dead Christ with Saints Faustinus and Parentius who were buried here. On the painted keystone Judith with the head of Holofernes is depicted.

Quoted From: Cappellina dei Corpi Santi 1499-1502

Lamentation over the Dead Christ with Saints Faustinus and Parentius: 1499-1502

Luca Signorelli completed the overall decoration of the Chapel of San Brizio in the small chapel on the far wall by the figures of Archangels Raphael (with Tobias), Gabriel and Michael (weighing souls and subjugating the devil), by Bishop Saints Brizio and Constant, and the Lamentation over the Dead Christ with Saints Faustinus (left) and Parentius (right).

Quoted From: Lamentation over the Dead Christ with Saints Faustinus and Parentius 1499-1502

Frescoes in the Sistine Chapel

by Luca Signorelli

Luca Signorelli probably joined the team of the four painters (Perugino, Botticelli, Cosimo Rosselli and Ghirlandaio) who were commissioned by Pope Sixtus IV to decorate the walls of the Sistine Chapel by the suggestion of Perugino. Vasari implies that it was Sixtus IV who summoned Signorelli to work in competition with the other painters in his palace chapel. The fresco containing the last scenes from the life of Moses was attributed by Vasari to Luca Signorelli and Bartolomeo della Gatta. However, the question of authorship of this painting is unsettled.

Quoted From: Frescoes in the Sistine Chapel

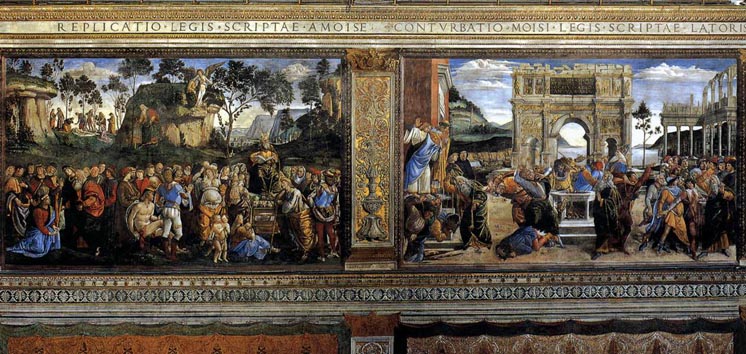

Scenes on the Left Wall: 1481-82

The depicted scenes are the Moses's Testament by Luca Signorelli and the Punishment of Corah by Sandro Botticelli.

Quoted From: Scenes on the Left Wall 1481-82

Moses's Testament and Death: 1481-82

The fresco is from the cycle of the life of Moses in the Sistine Chapel. It is located in the sixth compartment on the south wall.

The fresco depicts the last episodes in the life of Moses. On the right sits the hundred-and-twenty-year-old Moses on a rise, holding his staff and with golden rays circling his head. At Moses's feet stands the Ark of the Covenant, opened to show the jar of manna inside and the two tables of the law. In the left half of the picture Joshua is appointed Moses's successor. Joshua kneels before Moses, who gives him his staff. In the center of the background we see Moses being led by the angel of the Lord up Mount Nebo, from which he will be able to look across to the Promised Land that by the will of God he will never enter. At the foot of the mountain we see him again, turning toward the left. His death is depicted in the background, in the land of Moab, where the children of Israel mourned him for thirty days. Signorelli must have been just over thirty, when he became involved in the decoration of the Sistine Chapel. Luca's name does not appear among the group of Tuscan and Umbrian artists (Cosimo Rosselli, Botticelli, Ghirlandaio and Perugino) who, on 27 October 1481, signed the contract for the decoration of the side walls of the famous chapel, which were to be frescoed with Biblical scenes. But Vasari is absolutely certain of his involvement and his hand is evident in some details of the huge scene of Moses's Testament and Death. The painting, at any rate as it appears to us today, is for the most part the work of Bartolomeo della Gatta, reflecting his typical use of vibrant colour and subtle lighting. But, amidst the numerous figures that populate the scene, there are some whose anatomical description is full of energy and who convey powerful emotions: the young nude seated in the center, for example, or the two clothed figures portrayed with their backs to the onlooker, or the man with the stick leaning against Moses's throne. Luca Signorelli's hand appears quite obvious in these details, and in others as well.Quoted From: Moses's Testament and Death 1481-82

Frescoes in the Sacristy of Saint John, Basilica of Santa Casa, Loreto

by Luca Signorelli

The Santuario della Santa Casa (Sanctuary of the Holy House) at Loreto was constructed in the fifteenth century to enshrine the Holy House (Santa Casa) of the Virgin Mary, which tradition held had been brought from the Holy Land to Loreto by angels in the fourteenth century. The heart of the sanctuary is an unprepossessing brick chapel, said to be the structure in which the Virgin Mary was born, received the Annunciation, lived with Joseph and her child after returning from Egypt, and finally died in the presence of the twelve apostles.

In its layout, the shrine consists of three-aisle arms ending in apses to the north, east, and south, and a six-bay nave extending to the west. The chapels off the nave were added only after 1507, by Bramante. Around the crossing, with the Santa Casa in the center, are four octagonal rooms, closed off by doors that are referred to simply as sacristies. Two of the four were painted in the fifteenth century, the Sacristy of Saint John by Luca Signorelli, and the Sacristy of Saint Mark by Melozzo da Forli. There is a close connection between the gospel texts and the pictorial programs of the two painted sacristies. The Gospel of Saint John places particular emphasis on the gathering of Christ's disciples and the mission of the apostles, and this is reflected in the paintings of the Sacristy of Saint John. In five of the seven openings on the walls of the Sacristy of Saint John - the eighth is taken up by the window - there are pairs of apostles in dispute. The Conversion of Paul, a scene filled with dramatic movements, fills the one above the door, and the viewer sees it only when he turns to leave. The last opening, centered on the right as one enters, presents another familiar event, but one that in its composition repeats the pairings of the apostles, for it presents two figures side by side. In this case it is Christ and the apostle Thomas, who places his hand against the wound in Christ's side to assure himself that this is the resurrected Christ.Quoted From: Frescoes in the Sacristy of Saint John, Basilica of Santa Casa, Loreto

View of the Sacristy of Saint John: 1477-82

The individual apostles cannot be identified with the exception of Peter and John, who stand in the panel to the left of the Christ-Thomas grouping. The idea of presenting pairs of apostles in debate is borrowed from the bronze doors that Donatello created for the Old Sacristy at San Lorenzo, Florence. Signorelli borrowed not only some of the compositional features of Donatello's reliefs but also specific iconographic details. Like Donatello, he depicts his apostles barefoot and draped in classical garments, eschewing any identifying attributes and even halos.

Quoted From: View of the Sacristy of Saint John 1477-82

View of the Vaulting of the Sacristy of Saint John: 1477-82

The picture shows the vaulting of the Sacristy of Saint John with depictions of the four evangelists alternating with the four Latin Church fathers. In the wall compartments, five pairs of apostles, Christ and the Doubting Thomas, and above the door, the Conversion of Paul are depicted.

Quoted From: View of the Vaulting of the Sacristy of Saint John 1477-82

Pair of Apostles in Dispute: 1477-82

The individual apostles cannot be identified with the exception of Peter and John, who stand in the panel to the left of the Christ-Thomas grouping. The idea of presenting pairs of apostles in debate is borrowed from the bronze doors that Donatello created for the Old Sacristy at San Lorenzo, Florence. Signorelli borrowed not only some of the compositional features of Donatello's reliefs but also specific iconographic details. Like Donatello, he depicts his apostles barefoot and draped in classical garments, eschewing any identifying attributes and even halos.

Quoted From: Pair of Apostles in Dispute 1477-82

Pair of Apostles in Dispute: 1477-82 - # 2

Pair of Apostles in Dispute: 1477-82 - # 3

Pair of Apostles in Dispute: 1477-82 - # 4

The Apostles Peter and John the Evangelist: 1477-82

Christ and the Doubting Thomas: 1477-82

The last opening, centered on the right as one enters, presents another familiar event, but one that in its composition repeats the pairings of the apostles, for it presents two figures side by side. In this case it is Christ and the Apostle Thomas, who places his hand against the wound in Christ's side to assure himself that this is the resurrected Christ.

Quoted From: Christ and the Doubting Thomas 1477-82

The Conversion of Paul: 1477-82

The Conversion of Paul, a scene filled with dramatic movements, fills the opening above the door, and the viewer sees it only when he turns to leave.

Quoted From: The Conversion of Paul 1477-82

Frescoes in the Great Cloister, Abbazia, Monteoliveto Maggiore

by Luca Signorelli

The abbey of Monteoliveto Maggiore which stands atop a spur of the Crete Senese, the barren, rocky country southeast of Siena, is one of the most important and best preserved monastic complexes in southern Tuscany. It was founded by the prominent and well-to-do legal scholar Giovanni Tolomei (1272-1348), who resigned his post as podestà of Siena and renounced his worldly interests to take up the life of a hermit. He was joined by two other men from Siena, Ambrogio Piccolomini and Patrizio Patrizi. The three built themselves shelters in this hostile landscape and over the years still others were attracted to the fledgling ascetic community. On March 26, 1319, the Bishop of Arezzo, Guido Tarlati, confirmed the congregation as a new religious order.

The abbey is constructed entirely of brick, and comprises a jumble of structures linked by three inner courtyards, or cloisters, of different sizes and with different functions. The Great Cloister (Chiostro Grande) around which the more important communal spaces are disposed was constructed in stages between 1426 and 1443. The cloister was frescoed by Luca Signorelli with nine scenes on the west side (1497-99) and Sodoma with twenty-eight scenes (1505-08 and after 1513). The fresco cycle is comprised of thirty-six Scenes from the Life of Saint Benedict; Saint Benedict Presenting the Rule to the Olivetans; Man of Sorrow; Christ Carrying the Cross. The life of Saint Benedict is considered as a reflection and ideal of the monastic life. The exemplary nature of the scenes presented in the cloister at Monteoliveto Maggiore gives the impression that they were deliberately selected for their bearing on life within the monastery. Virtually all of the community's activities and concerns are reflected in them. The ultimate textual source for the Benedict cycle was the biography written by Gregory the Great in about 593-94, which tells the story of the important monastic founder in thirty-eight chapter.Quoted From: Frescoes in the Great Cloister, Abbazia, Monteoliveto Maggiore

The Great Cloister: 1497-99

Life of Saint Benedict Scene 23 Benedict Drives the Devil out of a Stone: 1499-1502

Scene 23 of the cycle on the life of Saint Benedict depicts Benedict driving the devil out of a stone.

Some scenes of the cycle depict the range of tasks that had to be accomplished to maintain the monastery's self-sufficiency. Among these are the erection of churches and other buildings in accordance with the founder's precepts - often delayed by interference from the archenemy Satan. The Evil One is omnipresent: in this scene he makes a stone so heavy that the monks are unable to raise it until Benedict comes to their aid.Quoted From: Life of Saint Benedict, Scene 23: Benedict Drives the Devil out of a Stone 1499-1502

Life of Saint Benedict Scene 25 Benedict Tells Two Monks What They Have Eaten: 1499-1502

Scene 25 of the cycle on the life of Saint Benedict depicts Benedict telling two monks where and what they have eaten outside the monastery.

In a number of scenes Benedict is required to be stern with his weaker brothers, either because they have become possessed by demons (Scene 13) or because they have given in to their cravings (Scene 25). The scenes in which the community is confronted with a group of voluptuous women (Scene 19) and two of the brothers gorge themselves at a nearby inn (Scene 25) stand out with their brighter colors and rich details.Quoted From: Life of Saint Benedict, Scene 25: Benedict Tells Two Monks What They Have Eaten 1499-1502

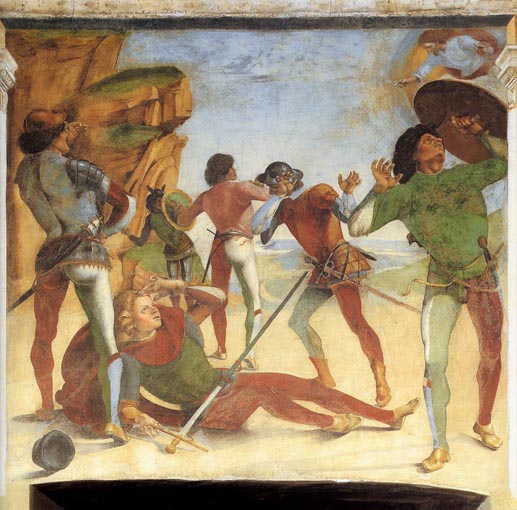

Life of Saint Benedict Scene 27 Benedict Discovers Totila's Deceit: 1499-1502

Scene 27 of the cycle on the life of Saint Benedict depicts Benedict discovering Totila's deceit.

The two scenes dealing with the Gothic king Totila, painted by Signorelli, are crowded with figures and full of action, and in a sense fall out of the established framework of the cycle, for here the fathers are confronted with a powerful figure from the outside world. Benedict is not fooled by Totila's ruse of sending his servant dressed in his own armor (Scene 27). Despite the king's arrogance and trickery, Benedict subsequently receives him, confronts him with his numerous misdeeds, and prophesies his end (Scene 28).Quoted From: Life of Saint Benedict, Scene 27: Benedict Discovers Totila's Deceit 1499-1502

Life of Saint Benedict Scene 28 Benedict Recognizes and Receives Totila: 1499-1502

Scene 28 of the cycle on the life of Saint Benedict depicts Benedict recognizing and receiving Totila.

The two scenes dealing with the Gothic king Totila, painted by Signorelli, are crowded with figures and full of action, and in a sense fall out of the established framework of the cycle, for here the fathers are confronted with a powerful figure from the outside world. Benedict is not fooled by Totila's ruse of sending his servant dressed in his own armor (Scene 27). Despite the king's arrogance and trickery, Benedict subsequently receives him, confronts him with his numerous misdeeds, and prophesies his end (Scene 28).Quoted From: Life of Saint Benedict, Scene 28: Benedict Recognizes and Receives Totila 1499-1502

Altarpiece of the Church of Saint Margaret in Cortona

by Luca Signorelli

The panel of the Lamentation in its original arrangement, mounted in an antique frame with pillars in which were represented seven saints, once enriched the scenography of the high altar of the ancient church of Saint Margaret in Cortona. This was surely admired by Pope Leo X when, during a stop on his way to Bologna to meet Francis I of France, he visited the church in 1515. In the second half of the 1700's the painting was moved, deprived of its frame, and finally placed in the choir of the cathedral of its origin.

The Lamentation, a work done entirely the artist alone, reveals all the poetry of the painter even in the context of an unrefined style which may seem declamatory, scenic and rhetorical. In the predella that Signorelli probably painted with the help of his assistant, Gerolamo Genga, four scenes from the Passion of Christ are represented: The Prayer in the Garden; The Last Supper; The Capture; The Flagellation.Quoted From: Altarpiece of the Church of Saint Margaret in Cortona

Lamentation over the Dead Christ: 1502

The static pose of the figures, which are seen in a moment of frozen drama, reveals strong links with popular religious plays. An account of Vasari says that Signorelli wanted to represent in the figure of the naked Christ his own son, who died of plague in 1502.

The Lamentation, a work done entirely the artist alone, reveals all the poetry of the painter even in the context of an unrefined style which may seem declamatory, scenic and rhetorical. It strikes the observer with great power and energy on account of its dimensions, the liveliness of its color and the strong statuesque attitude of the figures. The central characters are expressive and are painted in an attitude of pain. In the background there are two lively scenes contrast with the stillness of the central group of characters. In the middle, there is an unreal landscape, clear and clean, but interrupted by the tragic image of the blood flowing down the wood of the cross.Quoted From: Lamentation over the Dead Christ 1502

Lamentation over the Dead Christ (with predella): 1502

_1502.jpg)

This picture shows the Lamentation panel together with the predella, which consists of four scenes from the Passion of Christ: The prayer in the Garden; The Last Supper; The Capture; The Flagellation.

Quoted From: Lamentation over the Dead Christ (with predella) 1502

The Prayer in the Garden: 1502

In the predella that Signorelli probably painted with the help of his assistant, Gerolamo Genga, four scenes from the Passion of Christ are represented: The Prayer in the Garden; The Last Supper; The Capture; The Flagellation.

This picture shows the scene of the Prayer in the Garden.Quoted From: The Prayer in the Garden 1502

The Last Supper: 1502

In the predella that Signorelli probably painted with the help of his assistant, Gerolamo Genga, four scenes from the Passion of Christ are represented: The Prayer in the Garden; The Last Supper; The Capture; The Flagellation.

This picture shows the scene of the Last Supper from the predella.Quoted From: The Last Supper 1502

The Capture of Christ: 1502

In the predella that Signorelli probably painted with the help of his assistant, Gerolamo Genga, four scenes from the Passion of Christ are represented: The Prayer in the Garden; The Last Supper; The Capture; The Flagellation.

This picture shows the scene of the Capture.Quoted From: The Capture of Christ 1502

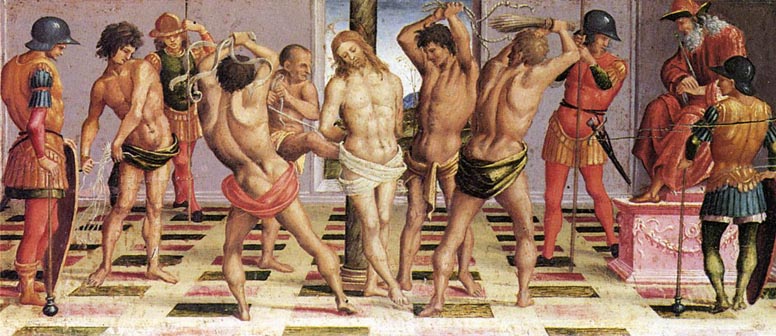

The Flagellation: 1502

In the predella that Signorelli probably painted with the help of his assistant, Gerolamo Genga, four scenes from the Passion of Christ are represented: The Prayer in the Garden; The Last Supper; The Capture; The Flagellation.

This picture shows the scene of the Flagellation.Quoted From: The Flagellation 1502

Various paintings

by Luca Signorelli

Madonna and Child with Saints: 1484

In this major altarpiece by Luca Signorelli, the enthroned Madonna and Child is accompanied by four saints, two of whom stand upon the base which supports her throne. A lute-playing angel, seated beneath the Virgin, intently tunes his instrument. Below a transparent glass with flowers casts a shadow, revealing the light source from the left.

Quoted From: Madonna and Child with Saints 1484

The Scourging of Christ: ca 1480

Signed: "OPUS LUCE CORTONENSIS" With the Madonna and Child, which is also in the Brera, this painting made up the double-faced processional image of the church of Saint Maria del Mercato at Fabriano?

This work reveals the broad influences on the young artist, who had closely studied the work of Piero della Francesca, Melozzo da Forli, Perugino and Francesco di Giorgio. The example of Pollaiolo can be seen in the creation of space by means of the harmonious placement of the figures in a circle around Christ. A classicizing atmosphere is created by the relief running across the foreground, which places the scene on a stage and separates it from the spectator. Other classicizing elements are the column bearing an idol, and the simulated bas-reliefs of the background wall, which recalls the scaena of an ancient Roman theater.Quoted From: The Scourging of Christ ca 1480

Madonna and Child: ca 1490

The Virgin is portrayed sitting in a flowery meadow, against a background of young athletes (probably to be interpreted as allegoric of ascetic virtues); towering above her are the monochrome figures of John the Baptist and two prophets. Vasari tells us that the painting was presented by Luca to Lorenzo the Magnificent and there can be no doubt that the learned symbolism and the allegorical references it contains would have been fully appreciated by the Medici Court, whose religious ideals in those years were founded on highly intellectual and philosophical studies, deeply imbued with Platonism and Classicism. Even the figurative references contained in this painting are extremely varied and sophisticated. There are references to Piero della Francesca's descendants of Adam (the young man in the background), to archeological elements, as well as tributes to Flemish painting (the monochromes in the upper part); and, above all, there is an explicit reference to Leonardo and his followers in the flowery meadow in the foreground, in the toned down colors, in the careful attention paid to chiaroscuro values.

Quoted From: Madonna and Child ca 1490

The Holy Family with Saint: 1490-92

One of the most frequent subjects in Signorelli's production is the Madonna and Child, or Holy Conversation, in a roundel. A number of examples have come down to us, attributed with more or less convincing arguments to Luca, and all of them including the work of assistants. The painting in the Pitti Palace is one of these roundels.

The studious young woman may be identified as Saint Catherine of Alexandria or Saint Barbara.Quoted From: The Holy Family with Saint 1490-92

The Holy Family with Saint: 1490-92-Two

Virgin and Child with Saints Jerome and Bernard of Clairvaux: 1492-93

Although several scholars doubt whether this painting is by Luca Signorelli and regard it a workshop product, it is more probable that the tondo for private devotion was designed and also executed by the master himself. That the painting is Signorelli's autograph work is revealed by the outstanding quality of certain details, in particular the faces of the Virgin and Saint Jerome, and by the structure of the ample and characteristic draperies.

Quoted From: Virgin and Child with Saints Jerome and Bernard of Clairvaux 1492-93

Scenes from the Lives of Joachim and Anne: ca 1490

This panel and another, The Birth of the Virgin in the same private collection, are from a predella of an unidentified Luca Signorelli altarpiece. In this panel three episodes are depicted: Joachim's expulsion from the temple; an angel visiting him in his retreat; meeting with his wife at the Golden Gate.

Quoted From: Scenes from the Lives of Joachim and Anne ca 1490

The Birth of the Virgin: ca 1490

This panel and another, The Birth of the Virgin in the same private collection, are from a predella of an unidentified Luca Signorelli altarpiece.

Quoted From: The Birth of the Virgin ca 1490

Portrait of an Elderly Man: ca 1492

Very few portraits survive from Signorelli's hand. Indubitably his finest is the Portrait of an Elderly Man, probably of a humanist. It is often said to be of a jurist, that profession and humanism considered practically inseparable. Victories before a temple approach athletes in front of a triumphal arch, these all'antica themes pertinent to the sitter's scholarly calling or pretensions. The action taking place in the background may be on his mind, as suggested by his downcast eyes. The hard-won balance between hat, head, V-shaped scarf, and the far-smaller figures is among the major triumphs of his great portrait.

Quoted From: Portrait of an Elderly Man ca 1492

Saint Augustine Altarpiece (Left Wing): 1498

_1498.jpg)

In 1498 Luca Signorelli executed a great altarpiece for the Bichi Chapel in the church of Sant'Agostino, Siena. Two wings, now in the Staatliche Museen, Berlin, flanked a statue of Saint Christopher ascribed to Francesco di Giorgio Martini (Musée du Louvre, Paris). The predella is now divided between various museums.

The left wing of the altarpiece represents Saints Catherine of Siena, Magdalen, and the kneeling Saint Jerome.Quoted From: Saint Augustine Altarpiece (Left Wing) 1498

Saint Augustine Altarpiece (Right Wing): 1498

_1498.jpg)

In 1498 Luca Signorelli executed a great altarpiece for the Bichi Chapel in the church of Sant'Agostino, Siena. Two wings, now in the Staatliche Museen, Berlin, flanked a statue of Saint Christopher ascribed to Francesco di Giorgio Martini (Musée du Louvre, Paris). The predella is now divided between various museums.

The right wing of the altarpiece represents Saints Augustine, Catherine of Alexandria and the kneeling Anthony of Padua.Quoted From: Saint Augustine Altarpiece (Right Wing) 1498

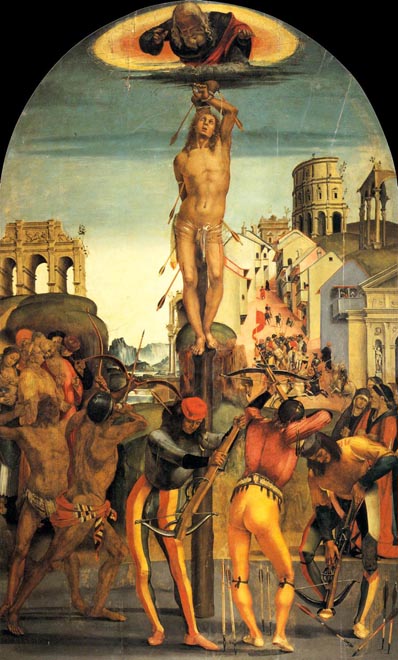

Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian: ca 1498

The figure bending at the waist was a popular motif at the end of the fifteenth century, especially experimented with for the companies of archers in narratives of Saint Sebastian's torture. Such poses give variation to figural groups and demonstrate the artist's skill, both in drawing and in placing the figure in a complex space.

Quoted From: Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian ca 1498

Self-Portrait with Niccolò d'Angeli Franceschi: 1500 or 1503

This painting is on a brick on the back of which is an inscription praising Signorelli as the painter of the Chapel of San Brizio. Niccolò d'Angeli Franceschi was the 'camerarius' of the Fabbrica of Orvieto cathedral from 1500 to 1501. The unusual medium and the inscription suggest that this portrait was possibly meant as a personal souvenir for the camerarius to mark the completion of the project in the chapel.

Quoted From: Self-Portrait with Niccolò d'Angeli Franceschi 1500 or 1503

Mary Magdalene: 1504

Flagellation: ca 1505

There are evident influences from Florence in the painting, but the crowded figures and their complex, foreshortened poses look forward to Signorelli's frescoes in the chapel of San Brizio in the cathedral at Orvieto.

Quoted From: Flagellation ca 1505

The Trinity, the Virgin and Two Saints: 1510

The painting was commissioned to Luca Signorelli by the Confraternità della Trinità dei Pellegrini of Cortona and shows a compact, tightly constructed composition. The Virgin and Child represent the central axis around which the Archangels Michael and Gabriel and Saints Augustine and Athanasius are grouped.

More rhetorical and at the same time archaizing is the glory of cherubim surrounding the symbolic apparition of the crucified Christ and God the Almighty.Quoted From: The Trinity, the Virgin and Two Saints 1510

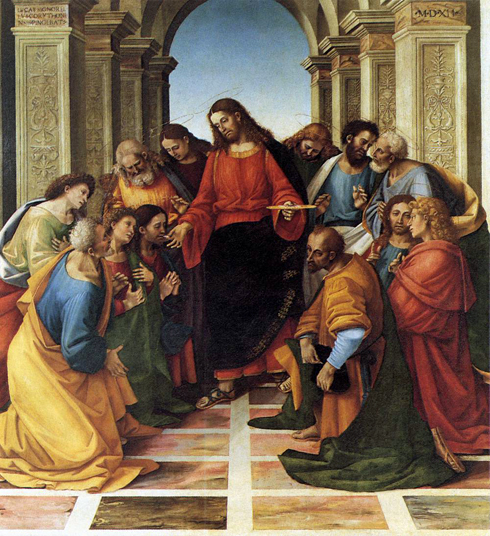

Communion of the Apostles: 1512

This work seems to be straining to escape from the cruel and tragic style of the Last Judgment of Orvieto and the Lamentation of Cortona, in order to imitate the sweet tones of the airy architecture of Raphael and the new sixteenth-century school.

The iconography of this panel is very unusual. The apostles, some standing, some on their knees, surround Christ to receive the consecrated Host. This contrasts with the traditional way in which the apostles are represented, seated around a set table. A classical structure functions as a background. The work reminds one of the rhythmic works of Perugino and seems to imitate Raphael's School of Athens. The figure of Judas is stupendous; he is leaning to one side hiding the Host in his bag with a look that shows the painful realization of his betrayal. The painting is signed and dated on the first capitals of the background columns.Quoted From: Communion of the Apostles 1512

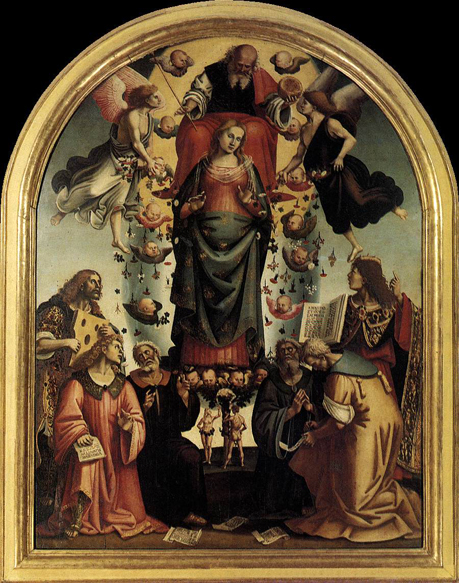

Immaculate Conception: ca 1523

This painting is one of the three that were commissioned from Luca Signorelli by the Company of Jesus for the three altars of their church in Cortona. These paintings were executed by Signorelli's workshop. The majority of art critics recognize in the Immaculate Conception the stylistic characteristics of Luca Signorelli's nephew, Francesco Signorelli.

Quoted From: Immaculate Conception ca 1523

Study of Nudes: ca 1500

Signorelli studied firsthand from the living model to create his marvelous drawings, which are often specific preparatory efforts for his frescoes. The only artist whose skill as a draftsman could equal that of Signorelli was the young Florentine sculptor who was required to paint a vast cycle in Rome a few years later, namely Michelangelo. It comes as no surprise that Michelangelo was not only acquainted with the painter from Cortona, but even lent him money.

Quoted From: Study of Nudes ca 1500

Four Demons with a Book

Numerous Signorelli drawings have survived but only a few of them can be directly related to the Orvieto paintings. Many of their figures, such as the devils seen on the present drawing, would have had to be developed especially for this project, as Signorelli had never dealt with such subjects.

Quoted From: Four Demons with a Book

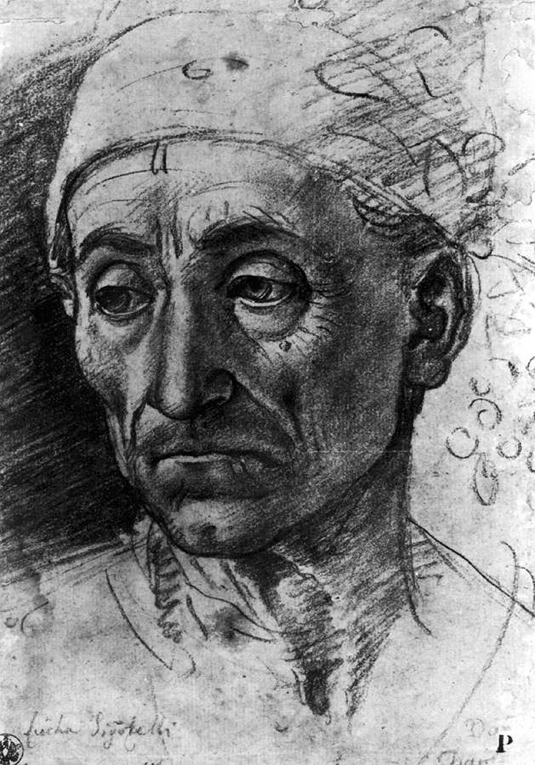

Head of a Poet Wearing a Cap

This drawing depicts a poet wearing a cap and crowned with a laurel wreath. This impressive portrait is very likely the one of Virgil. The flat beretto of the type worn by scholars was a standard attribute in portraits of Virgil. Virgil's portrait in the compartment behind the Baroque altar in the Chapel of San Brizio in Orvieto has now been lost.

Quoted From: Head of a Poet Wearing a Cap

Additional Sources:

Luca Signorelli - The Web Gallery of Art

Luca Signorelli - Olga's Gallery

Luca Signorelli - Biography and Gallery of Art

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.