Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

French Artist

1864 - 1901

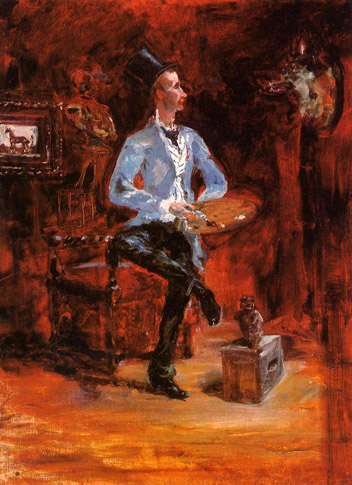

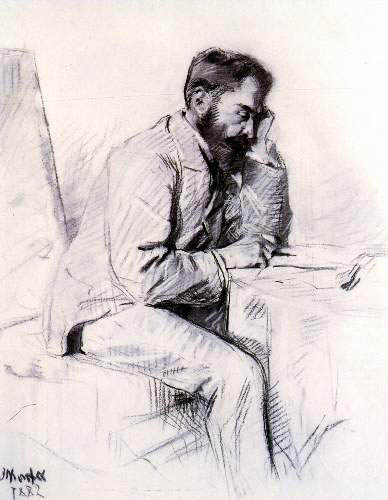

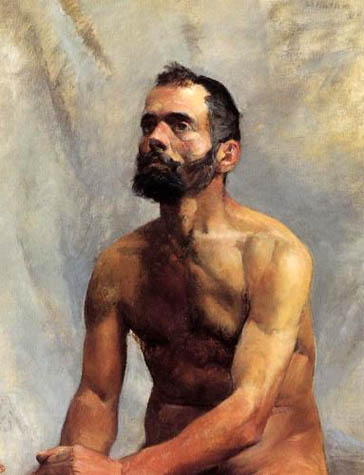

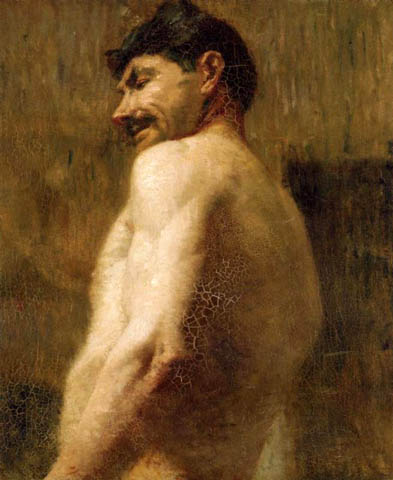

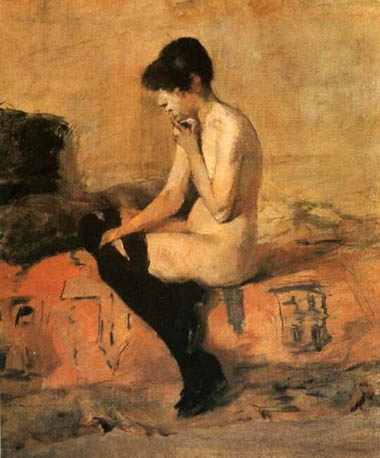

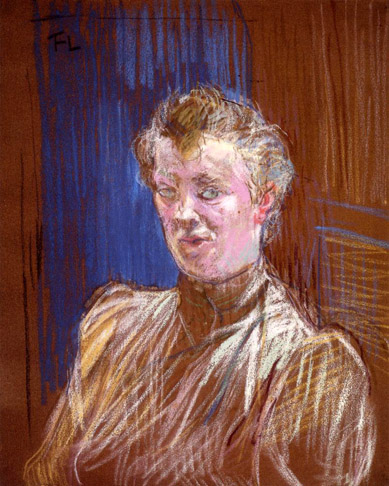

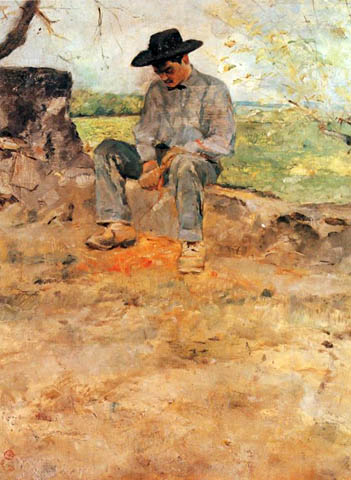

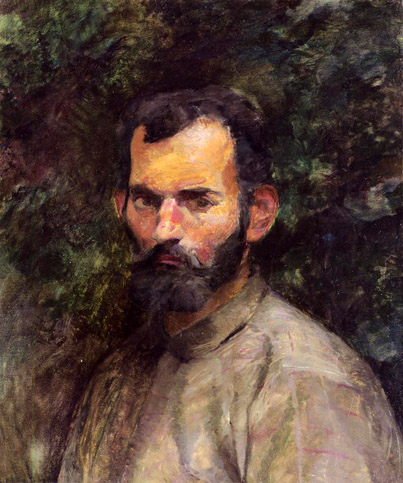

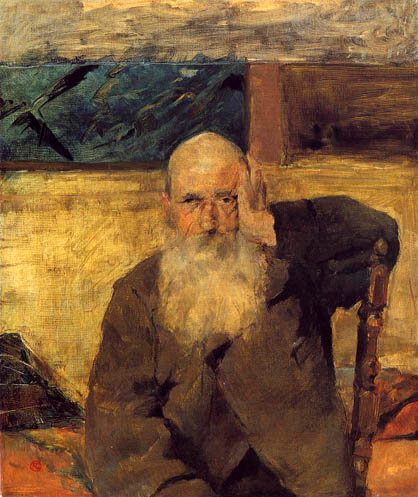

Self Portrait: ca 1882-83

Henri Marie Raymond de Toulouse-Lautrec-Monfa or simply Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864 - 1901) was a French painter, printmaker, draughtsman, and illustrator, whose immersion in the colorful and theatrical life of fin de siècle Paris yielded an œuvre of exciting, elegant and provocative images of the modern and sometimes decadent life of those times. Toulouse-Lautrec is known along with Cézanne, Van Gogh, and Gauguin as one of the greatest painters of the Post-Impressionist period. In a 2005 auction at Christie's auction house a new record was set when "La blanchisseuse", an early painting of a young laundress, sold for $22.4 million U.S.

"La blanchisseuse"

aka The Laundress: 1889

From Aristocrat to Bohemian

The turning point in Toulouse-Lautrec's art, showing which of these callings eventually took over Lautrec, is La Blanchisseuse (1886-1887), as the contrast between Carmen's hair and the background switches from those in the first paintings. Considered his first masterpiece according to Christie's where it sold for $22,400,000, this painting could suggest his bohemian side slightly taking over his aristocratic side in a palette hinting to his abating feelings of doubt about his bohemian life. Toulouse-Lautrec renders her dressed in a bright, white blouse that seems to emanate light, despite the fact that the true source of light should be the window in the extreme left of the painting. Even the part of her hair that should be illuminated by the window light is now darker, and the rest, in the shadow, is rendered in a dark red-brown hue. Her countenance too, though facing the light, is rendered darker than her hand, which seems to have borrowed some whiteness from the blouse and the cloth on the table, as if the inner light is slowly draining away from her, turning her from source of light to absorber of light. This contrast between the white blouse and dark hair and face, antithetical to the contrast in the first paintings, hints to Lautrec's realizing that his noble descent is being shadowed by the bohemian lifestyle he was starting to indulge in, but perhaps just as Carmen is depicted half lighted, Lautrec wants to regard himself as still partly aristocratic.

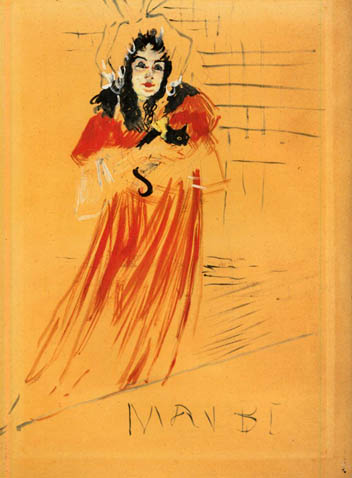

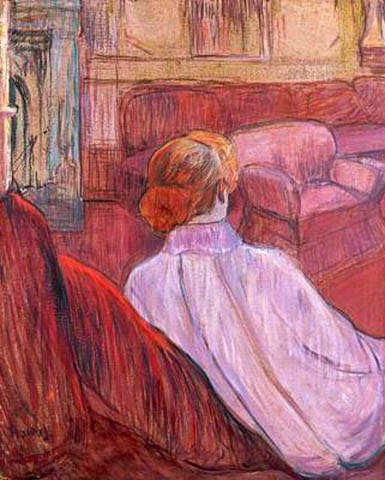

Even when bohemia permanently took over Lautrec, as marked by the painting 'At Montrouge, Rosa la Rouge'(1886-1887), the artist still exhibits a significant degree of ambivalence regarding his now fully bohemian lifestyle. Here, Gaudin is shown in a white blouse contrasting with her dark red hair and shadowed face. The intriguing aspect of this painting is that, in speaking about At Montrouge, Rosa la Rouge, Pierre Cabanne refers to the model who sat for it as being not Carmen Gaudin, but Rosa 'La Rouge', "an experienced lover" who helped Toulouse-Lautrec get over another disappointment in love. Furthermore, Julia Frey claims that Lautrec might have gotten syphilis from a prostitute known on the "butte" as "Rosa la Rouge" about the year 1886, the same year as this painting, although he had been warned of the girl's illness. Yet by looking at the women in La Blanchisseuse and At Montrouge, Rosa la Rouge, we notice that the resemblance between the two is striking: same features, same dark red hair, same white blouse. This entitles us to conclude that the same model sat for both, a hypothesis confirmed by Charles Stuckey in his book Toulouse-Lautrec, Paintings in which he identifies the model as Carmen. Therefore, the angelic, noble Carmen, the laundress- symbol of purity- has transformed into the demonic Rosa, the prostitute. This change is reflected in the colors of the painting: whereas in Carmen, the golden hair and bright face rendered her as an angel, here the white blouse serves only to enhance her dark hair and countenance, her once halo-like locks now resembling the horns of a devil. In changing Carmen from angel to devil, Lautrec might subconsciously try to show us how he too was "colored" by the licentious environment of Montmartre, capturing his own decay by darkening his palette throughout this series of paintings. Nevertheless, by juxtaposing the model's darkness and the light from the window behind her, Lautrec still shows a degree of ambivalence towards his new life, as if wanting to keep his old life close, like a safety net in case his bohemian lifestyle would lead him to self-destruction.

Quoted From: Toulouse Lautrec and Carmen Guedin: From Aristocrat to Bohemian

At Montrouge, Rosa la Rouge

Henri Marie Raymond de Toulouse-Lautrec-Monfa was born at the Chateau de Malromé near Albi, Tarn in the Midi-Pyrénées région of France, the firstborn child of Comte Alphonse and Comtesse Adèle Tapié de Celeyran. He was therefore a member of an aristocratic family (descendants of the Counts of Toulouse and Lautrec and the Viscounts of Montfa, a village and commune of the Tarn department of southern France). A younger brother was also born to the family on August 28, 1867, but died the following year.

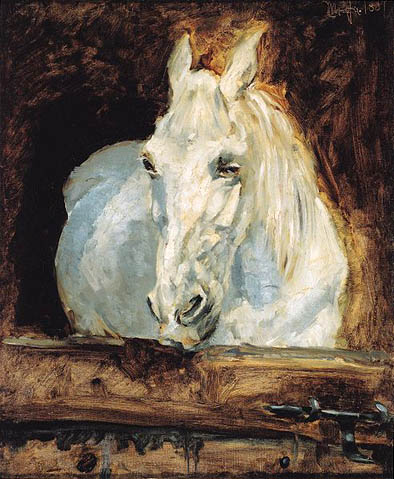

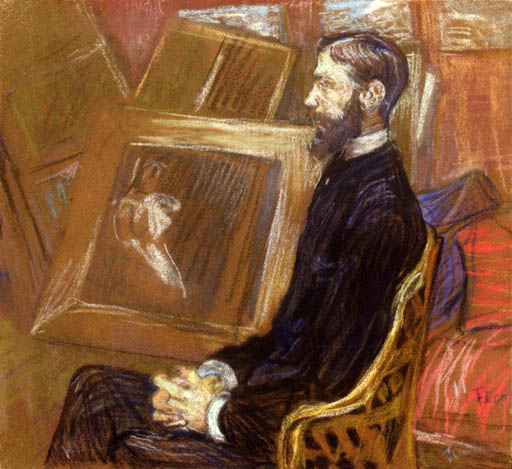

Princeteau in His Studio: 1881

Princeteau in His Studio: 1881-82

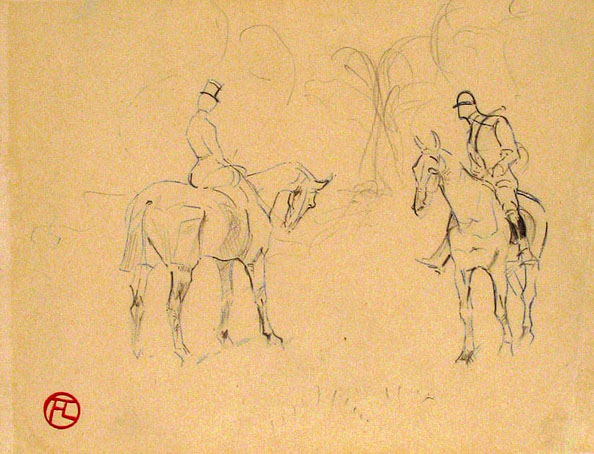

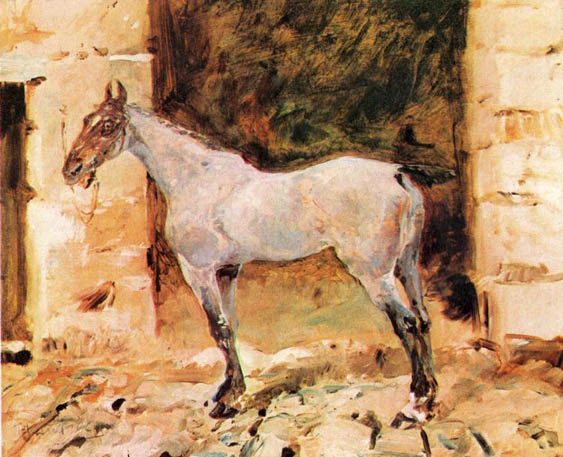

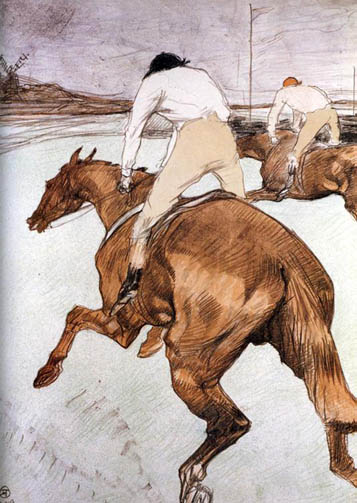

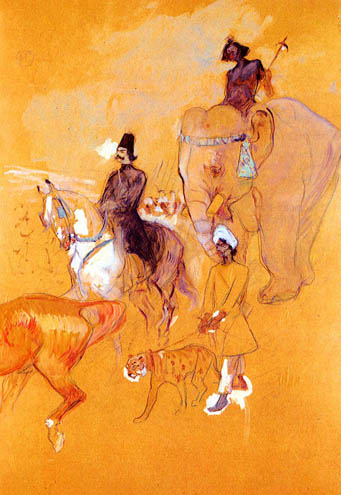

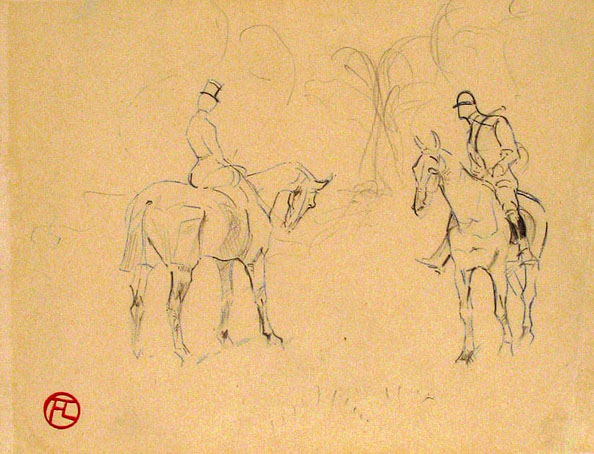

After the death of his brother his parents separated and a nanny took care of Henri through this time. At the age of 8, Henri left to live with his mother in Paris. Here he started to draw his first sketches and caricatures on his exercise workbooks. The family quickly came to realize that Henri's talent lay with drawing and painting, and a friend of his father named Rene Princeteau visited sometimes to give informal lessons. Some of Henri's early paintings are of horses, a specialty of Princeteau, and something that he would later visit with his 'Circus Paintings'.

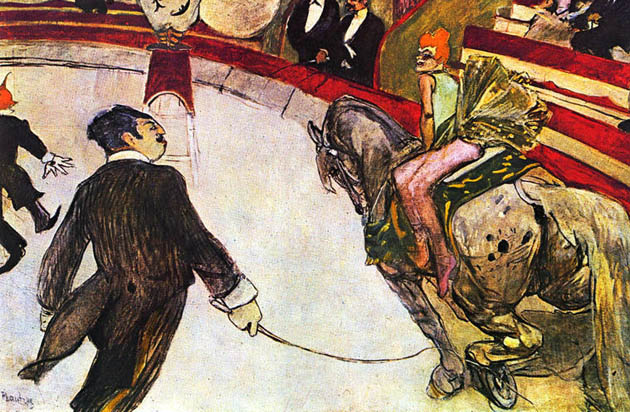

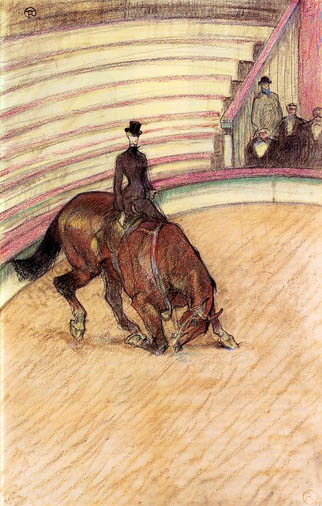

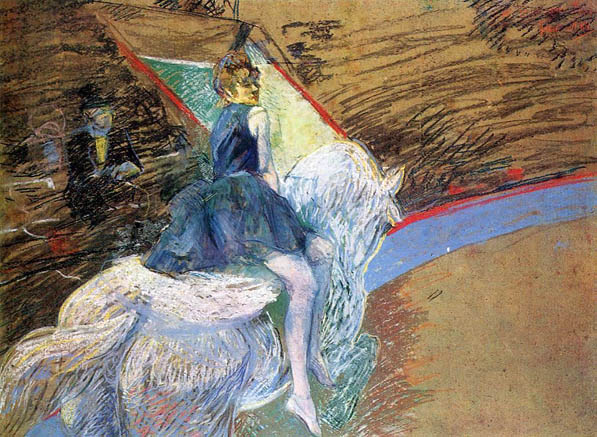

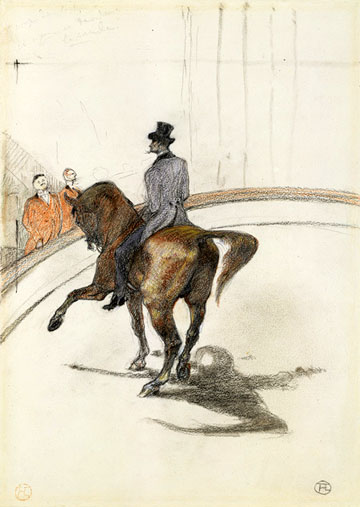

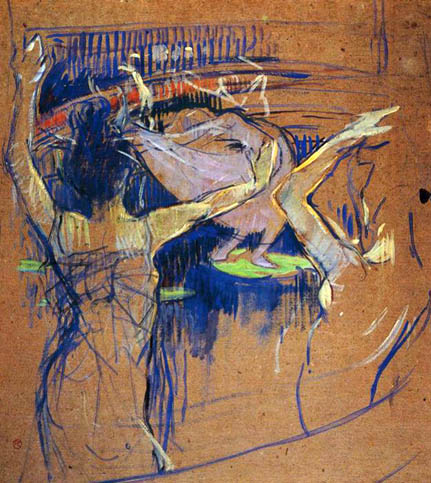

At the Circus Fernando, Eqestrienne: 1887-88

At the Circus - Entering the Ring: 1899

In a letter dated March 1899, an English poet wrote: "Toulouse-Lautrec you will be sorry to hear I was taken to a lunatic asylum yesterday." The scandal was in fact highly publicized. By the time Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec was thirty-five, he was suffering from alcoholism and dementia, most likely brought on by syphilis. His behavior was unpredictable, and often violent. Desperate, his mother had him committed to a clinic, then known as an asylum, outside of Paris.

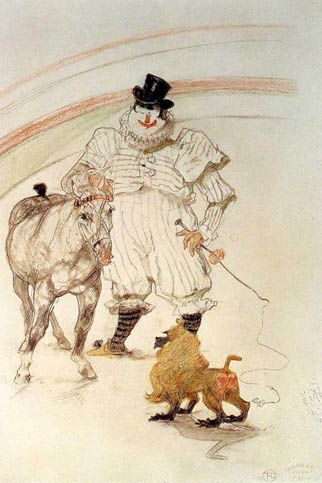

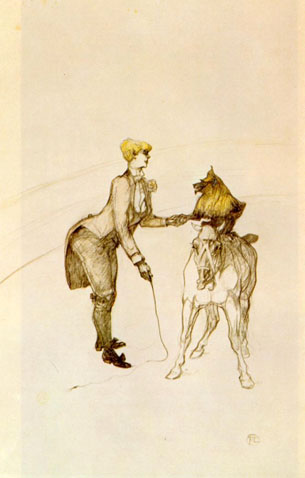

While in the clinic, Toulouse-Lautrec set upon the idea of creating a series of circus drawings to demonstrate his emotional stability and thus secure his release. Drawn from memories culled over many years of attendance at this popular entertainment, these works reveal his acute observation of horses, dogs, acrobats, clowns, and bareback riders. In this image, a performer still wearing her slippers follows a lumpy horse into the arena to perform for the spectators in the stands. Toulouse-Lautrec elongated the shadows behind the slippers to emphasize the woman's fatigue. Upon being released from the clinic after only three months, Toulouse-Lautrec declared: "I bought my freedom with my drawings."

From: At the Circus: Entering the Ring - Getty Museum

At the Circus - Performing Horse and Monkey: 1899

At the Circus - The Animal Trainer: 1899

At the Circus - Dressage

At the Cirque Fernando

(Rider on a White Horse)

In 1875 Henri returned to Albi because his mother recognized his health problems. He took thermal baths at Amélie-les-Bains and his mother consulted doctors in the hope of finding a way to improve her son's growth and development.

The Comte and Comtesse themselves were first cousins (Henri's two grandmothers being sisters) and Henri suffered from a number of congenital health conditions attributed to this tradition of inbreeding.

At the age of 13, Henri fractured his right thigh bone, and at 14, the left. The breaks did not heal properly. Modern physicians attribute this to an unknown genetic disorder, possibly pycnodysostosis (also sometimes known as Toulouse-Lautrec Syndrome), or a variant disorder along the lines of osteoporosis, achondroplasia, or ontogenesis imperfecta. Rickets aggravated with praecox virilism has also been suggested. His legs ceased to grow, so that as an adult he was only (5 ft 1 in) tall, having developed an adult-sized torso, while retaining his child-sized legs, which were (27.5 in) long. He is also reported to have had hypertrophied genitals.

Physically unable to participate in most of the activities typically enjoyed by men of his age, Toulouse-Lautrec immersed himself in his art. He became an important Post-Impressionist painter, art nouveau illustrator, and lithographer; and recorded in his works many details of the late-19th-century bohemian lifestyle in Paris. Toulouse-Lautrec also contributed a number of illustrations to the magazine Le Rire during the mid-1890's.

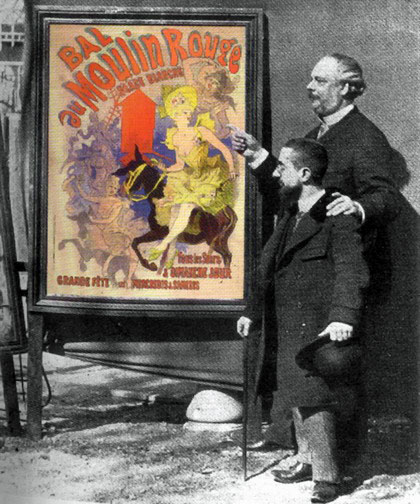

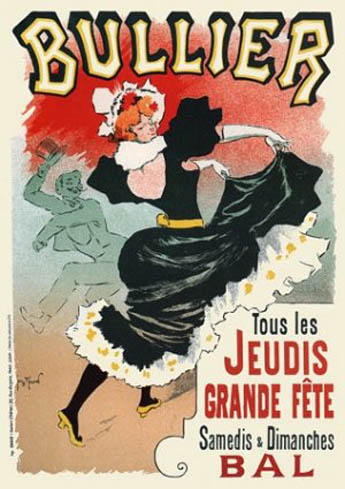

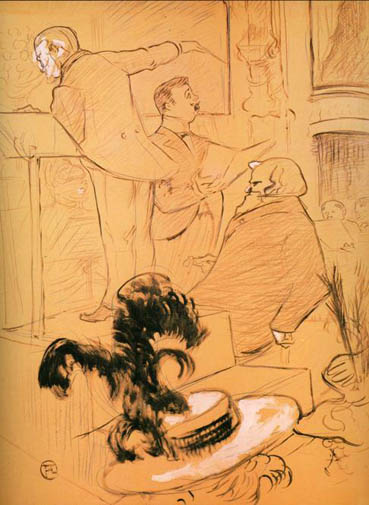

Jules Cheret and Lautrec with poster

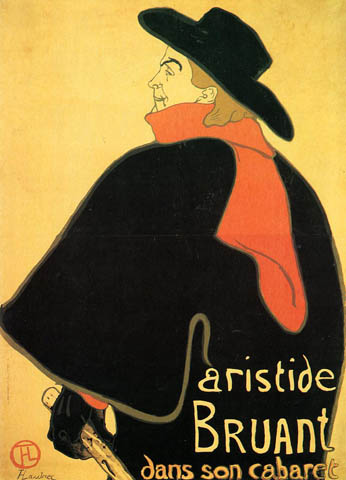

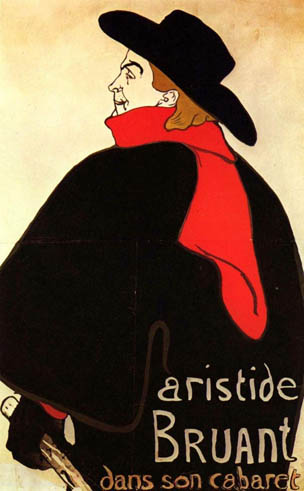

Aristede Bruand at His Cabaret: 1893

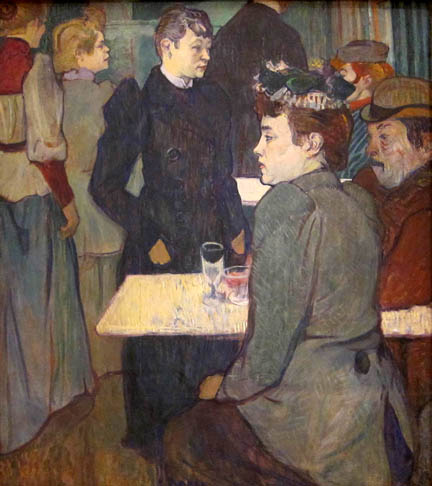

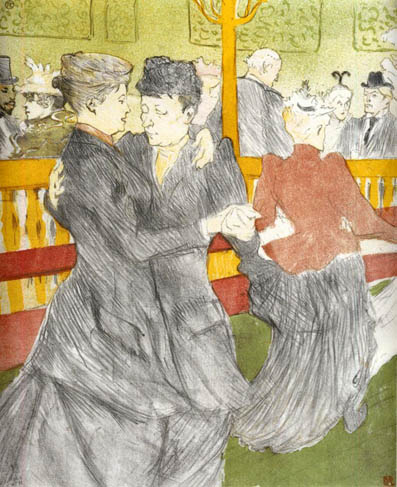

At the Moulin Rouge

The Beginning of the Quadrille: ca 1892

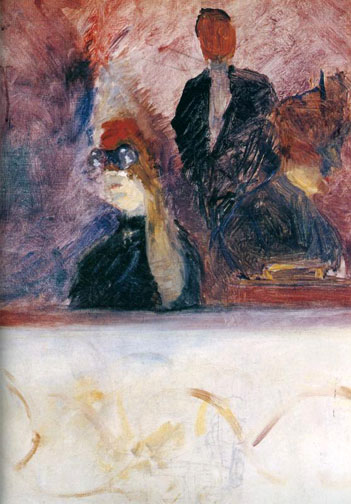

Au Concert: 1896

_1892.jpg)

Au Moulin Rouge

(La Goulue et la Mome Fromage): 1892

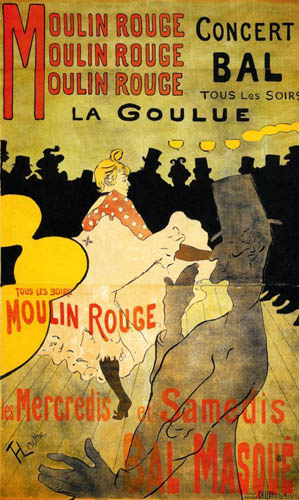

Louise Weber

La Goulue ("the glutton") was the stage name of Louise Weber (1866-1929), a dancer at several Montmartre night spots. During the 1880's, she became notorious for the open sexuality of her rowdy/explicit performances-a more explicit version of the cancan in which the dancer did standing splits. Heavily promoted in the press, she became the subject of Toulouse-Lautrec's first, highly successful, advertising poster, as well as numerous subsequent works.

From: Toulouse-Lautrec and Paris

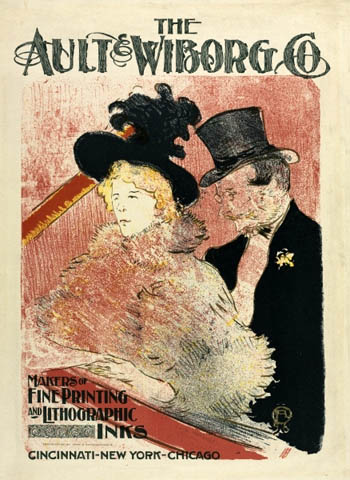

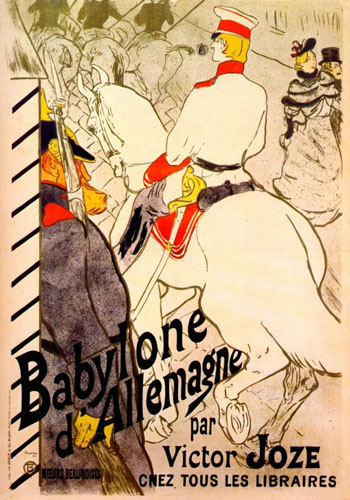

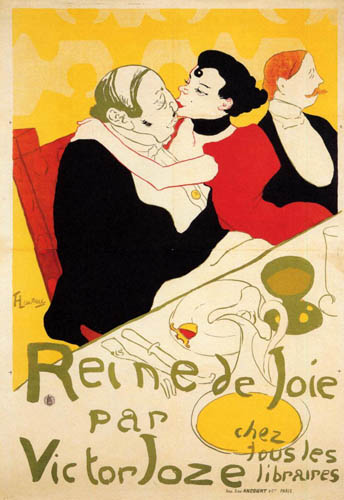

Babylone d'Allemagne: 1894

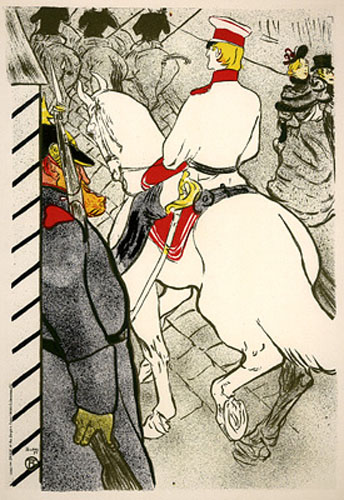

Babylone d'Allemagne - Alternate Version

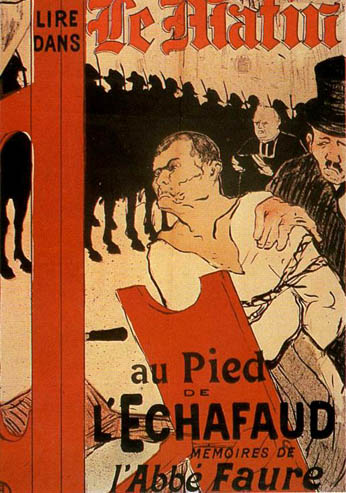

"Victor Joze's (Lautrec's friend) Babylone d'Allemagne is a series of satirical accounts of corruption and debauchery in Germany. It's title (not shown in this version before text) is an insulting reference to Berlin (the German Babylon)" (San Diego Museum of Art)

"Lautrec's poster focused the spectator's attention on the hindquarters of four horses, the largest of which was also being closely observed by a caricature of the Kaiser standing in a guard box. The implications of this, along with the book's title, (not shown in this version) provoked a protest from the German ambassador to France and nearly caused an international incident...Lautrec refused to stop distribution of the poster, and as he had paid for it, the publisher was not able to stop the distribution himself. (Thereafter), according to art dealer Edmond Sagot, the value of Henry's work quadrupled"

During the 1960's the renowned French printer, Mourlot Freres, printed this superb series "Les Affiches de Toulouse-Lautrec" for collectors. They are reduced lithographic versions of Lautrec's most famous works. They are truly the most beautiful printing we have been able to find in this size format.

As vintage printings of Lautrec's work, in all formats, reach high prices, this mid-century printing offers a superb alternative at a reasonable price that will only appreciate in value.

From: Toulouse-Lautrec - Babylone d'Allemagne

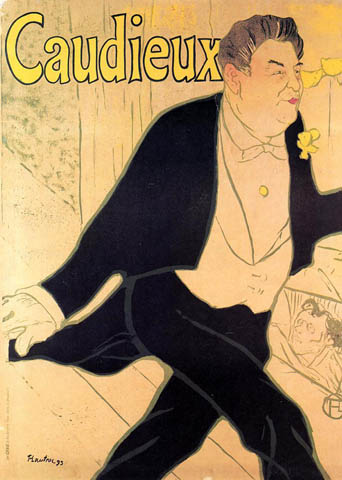

Cadieux: 1893

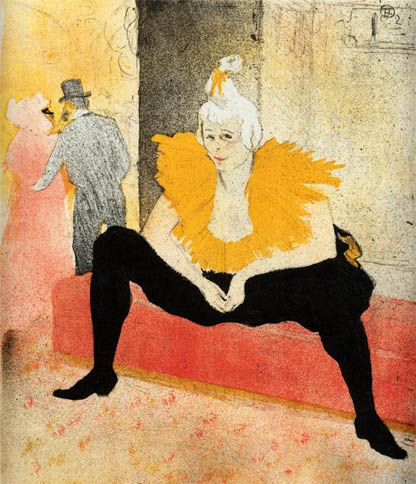

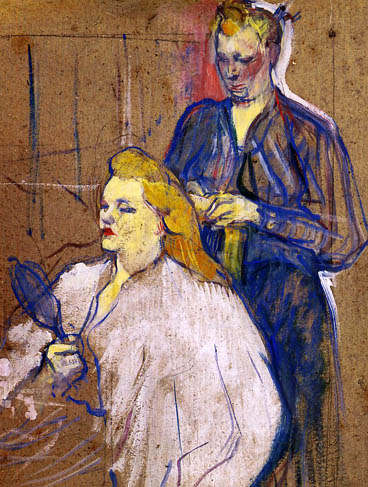

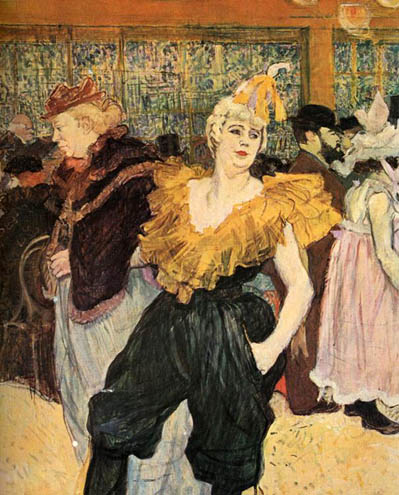

Cha-U-Kao,

The Clowness: 1895

A dancer and clown at the Nouveau Cirque and the Moulin Rouge, Cha-U-Kao owes her Japanese sounding name to the phonetic transcription of the French words "chahut" (an acrobatic dance derived from the cancan) and "chaos" referring to the uproar that occurred when she came on stage. Like La Goulue, Cha-U-Kao is a recurring figure in the painter's work and belongs to the world of Parisian showbiz in the late 19th century. Her work as a clown and sometimes even an acrobat nonetheless brought her closer to the circus tradition - which also fascinated the painter - than to the cabarets.

Unlike the series of drawings or lithographs in which Cha-U-Kao appeared under the spotlights, Toulouse-Lautrec here offers a more private view of his character, shown in her dressing room or a private room. Painted in oils on card, Cha-U-Kao is trying to fasten a large yellow ruffle to the bodice of her stage costume. The outsized ruffle, which takes up a large part of the surprising composition, is echoed by the yellow ribbon which almost ironically attaches the clown's white toupee. Above a small table we can see a portrait or mirror in which there is a reflection of an elderly man who could be a close friend, an admirer or a customer.

Toulouse-Lautrec has covered the entire surface of the painting with a series of lively, colorful brushstrokes, green for the walls or red for the sofa. The unusual cropping and the studied treatment of textures go well with the trivial and private nature of the scene.

From: Musée d'Orsay: Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec The Clown Cha-U-Kao

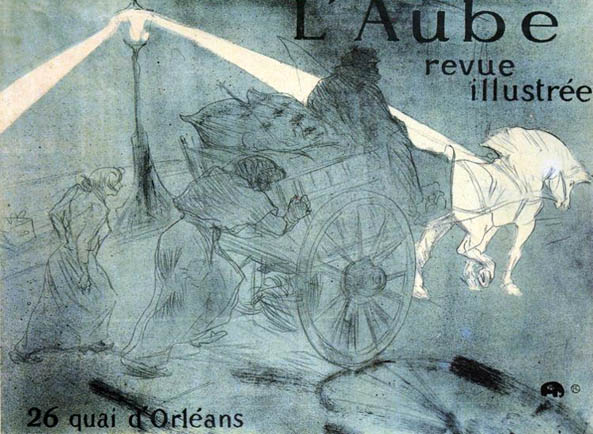

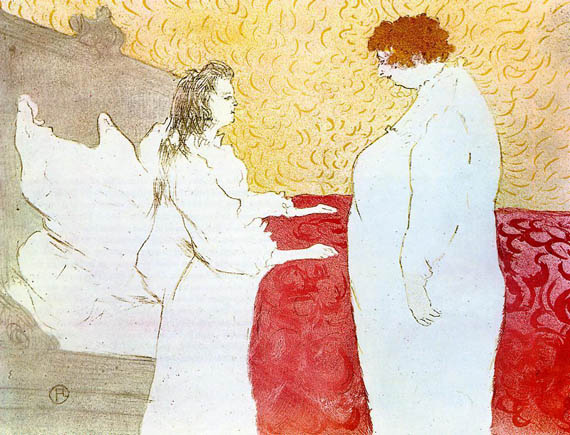

Dawn: 1896

Debauche: 1896

After initially failing his college entrance exams, Henri passed upon his second attempt and completed his studies. During his stay in Nice, his progress in painting and drawing impressed Princeteau, who persuaded Henri's parents to let him return to Paris and study under the acclaimed portrait painter Léon Bonnat. Henri's mother had high ambitions and, with aims of Henri becoming a fashionable and respected painter, she used the family influence to get Henri into Bonnat's studio.

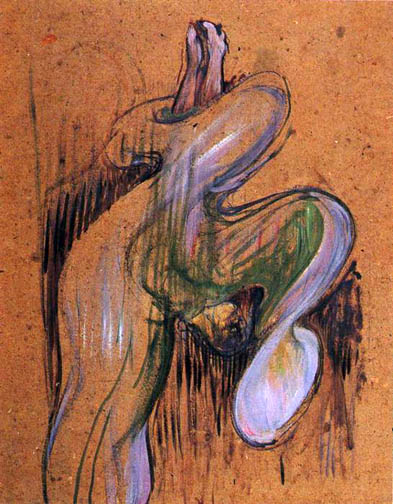

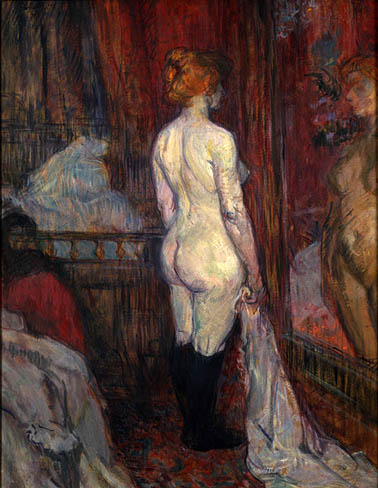

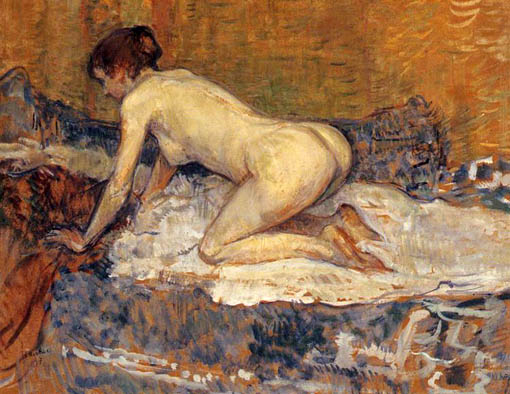

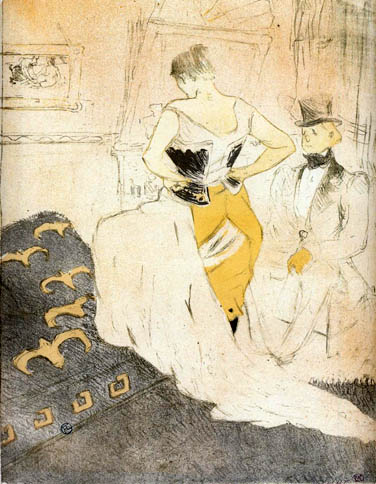

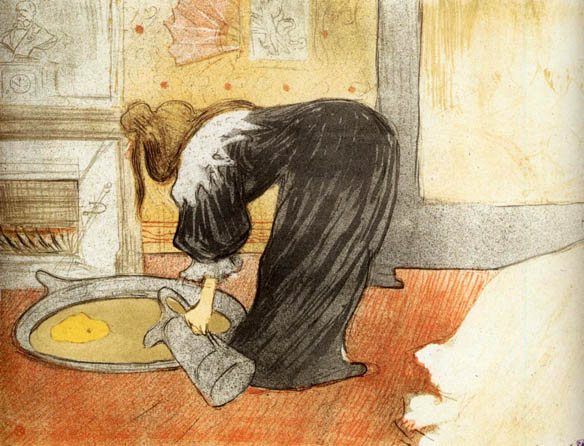

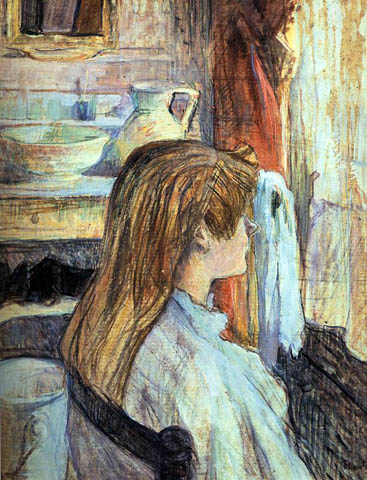

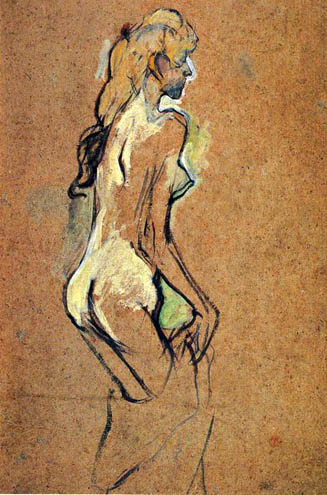

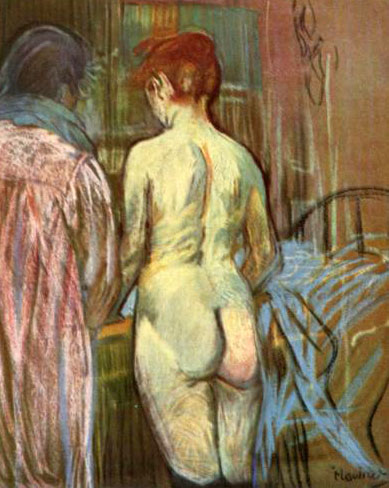

The Toilette: 1896

aka "Red-head, Washing" by Henri de Toulouse Lautrec

Woman Flower

We are looking down upon the bare back of a young woman just out of the bath. Intimate, but not erotic, a bluish light on her light frame and translucent flesh. Quick, nervous little strokes extract from the silent drapery, a stunning corolla, from the auburn hair, a dazzling pistil. A kind of flower blooms. Can you see this miraculous alchemy?

With a drawing that is not a tracing copying reality, but a collection of marks suggesting it, Toulouse Lautrec captures life in unexpected subjects.

Félix Fénéon is a fierce champion of Lautrec.

This nude, seen from behind, is not an Academic nude; the beauty of the bony body is not immediately apparent, the modeling is achieved by tiny 'dashes' of the brush.

Ambiguities: It's a nude, but there is nothing academic about it. Our subject is a model, but also a very real woman. Her pose is static, but there's a sense of movement.

This is an intimate work in all senses of the term, an expression of Lautrec's love for women. He catches his model as she gets out of the bath-tub, a moment of well-being for the body, rather than eroticism. She gets out of the water, to be bathed instead in a halo of light.

Here Lautrec evokes a matter that we do not find in anyone else's work : bone. A subject of great relevance to Lautrec, given the serious physical handicap that marked his life. Lautrec's bones are slight and delicate, often complex, and always masterfully studied. This aspect of his art is particularly apparent in Redhead, Washing. Her bone structure is robust, without feeling heavy.

Lautrec riddles his model with watered-down strokes of this bleached ochre, and creates long curved streaks of burnt Sienna for her hair. He adds this color to her cheek, to pink it up, and to her left shoulder, in the shadow cast by her head. He applies a light pink, mixed with white and blue, to the parts of the petticoat and cloths that the model is sitting on that are in the light. The body's volume is indicated by long crisscrossing brushstrokes.

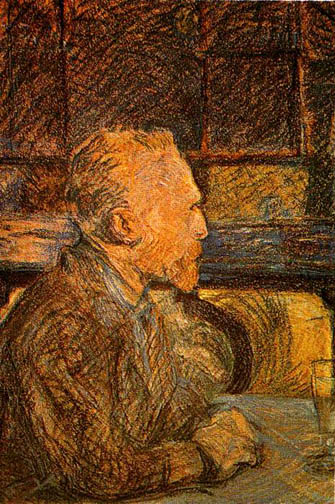

Toulouse-Lautrec was drawn to Montmartre, an area of Paris famous for its bohemian lifestyle and for being the haunt of artists, writers, and philosophers. Studying with Bonnat placed Henri in the heart of Montmartre, an area that he would rarely leave over the next 20 years. After Bonnat took a new job, Henri moved to the studio of Fernand Cormon in 1882 and studied for a further five years, here making the group of friends he would keep for the rest of his life. It was at this period in his life he first met Émile Bernard and Van Gogh. Cormon, whose instruction was more relaxed than Bonnat's, allowed his pupils to roam Paris, looking for subjects to paint. In this period Toulouse-Lautrec had his first encounter with a prostitute, reputedly sponsored by his friends, and this led him to paint his first painting of the prostitutes of Montmartre, a woman rumored to be called Marie-Charlotte.

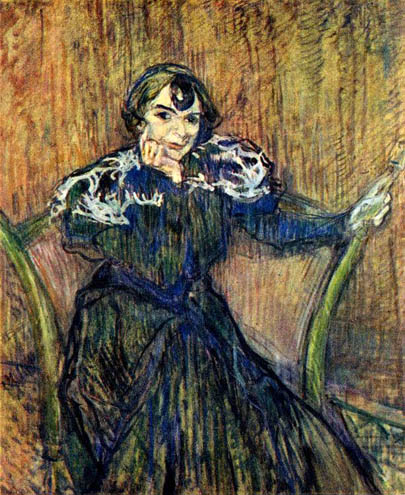

Emile Bernard: 1886

Emile Bernard was a fellow student of Toulouse-Lautrec with a reputation for artistic audacity. He entered Cormon's atelier in Paris in 1885, but was expelled in the spring of 1886.

Bernard sat twenty times for this portrait, in which Lautrec portrays him more as a young bourgeois than a radical artist. It was probably painted in 1886, when Lautrec moved into his studio in the rue Caulaincourt, Montmartre. It was common for students to sit for each other at the time, as the practice provided convenient and free subject matter. Bernard himself drew a sketch of Lautrec.

From: Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec - Emile Bernard - The National Gallery, London

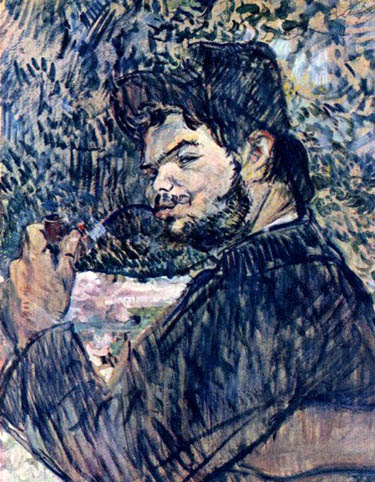

Portrait of Vincent Van Gogh: 1887

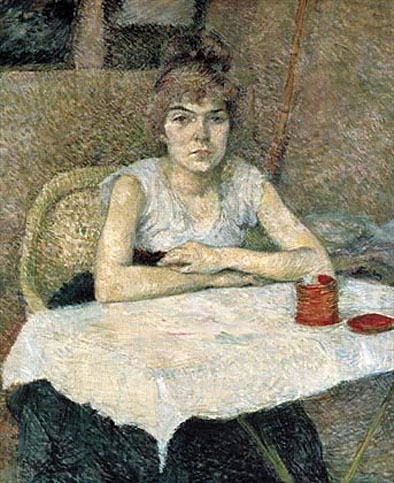

With his studies finished, in 1887 he participated in an exposition in Toulouse under the pseudonym "Tréclau", an anagram of the family name 'Lautrec'. He later exhibited in Paris with Van Gogh and Louis Anquetin. The Belgian critic Octave Maus invited him to present eleven pieces at the Vingt (the Twenties) exhibition in Brussels in February. The brother of Vincent van Gogh, Theo van Gogh bought 'Poudre de Riz' (Rice Powder) at the price of 150 francs for the Goupil and Cie gallery.

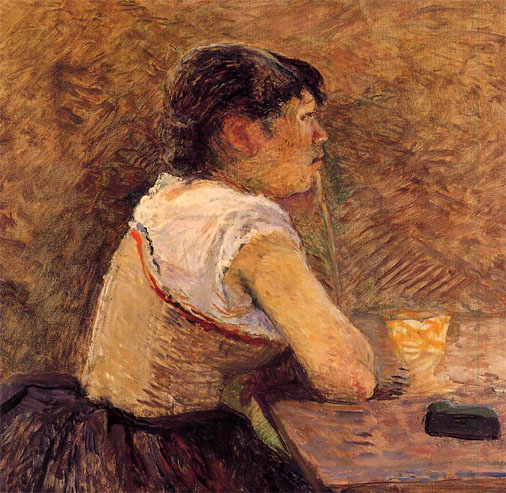

Poudre de riz

(Rice Powder)

This painting by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec shows a young woman seated at a table, a red jar of some kind in front of her. She looks directly at the viewer. It is difficult to identify exactly where the scene takes place. Is it a café or other public place, or a room in a house? The dark green patches at the upper right could be a painting, or perhaps a window.. The woman's role and identity is also unclear: is she a model posing for the painter, or has he depicted a real situation from memory?

Rice Powder

Thanks to the painting's title, however, we do know something about the contents of the little red jar. It is filled with perfumed rice powder, which women used to give themselves a fashionably pale complexion.

It was not considered good manners for women to sit alone in cafés, and even less so to put on their make-up in public. That kind of behavior was associated with the prostitutes Toulouse-Lautrec often depicted. This soberly dressed woman, however, does not appear to be of that profession. It has often been claimed that the work depicts Suzanne Valadon, the artist's mistress. Valadon was also a painter, and Toulouse-Lautrec encouraged her to pursue her art. He also made several portraits of her.

Style

The work belongs to Toulouse-Lautrec's early period, when he was strongly influenced by Impressionism. The artist has built up his canvas in short, colorful stokes; these loose dots were meant to merge in the viewer's eye, forming coherent areas of color. The artist also made numerous drawings at this period, many of which are more sketchy in character.

From: Van Gogh Museum - Young woman at a table, Poudre de riz

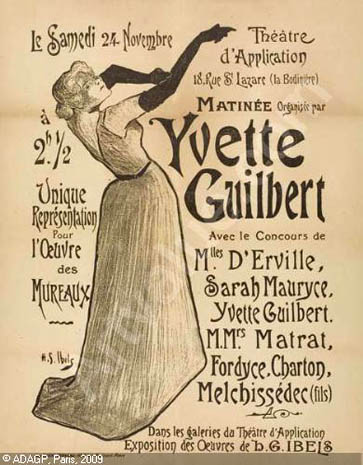

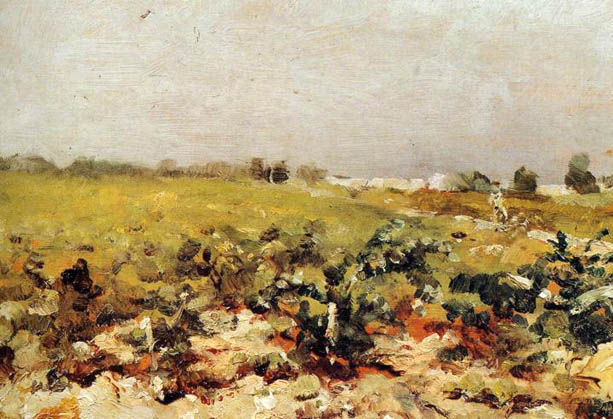

From 1889 until 1894, Henri took part in the "Independent Artists' Salon" on a regular basis. He made several landscapes of Montmartre. It was in this era that the 'Moulin Rouge' opened. Tucked deep into Montmartre was the garden of Monsieur Pere Foret, where Toulouse-Lautrec executed a series of pleasant plein-air paintings of Carmen Gaudin, the same red-head model who appears in The Laundress (1888). When the nearby Moulin Rouge cabaret opened its doors, Toulouse-Lautrec was commissioned to produce a series of posters. His mother had left Paris and while Henri still had a regular income from his family, making posters offered him a living of his own. Other artists looked down on the work, but Henri was so aristocratic he did not care. Thereafter, the cabaret reserved a seat for him, and displayed his paintings. Among the well known works that he painted for the Moulin Rouge and other Parisian nightclubs are depictions of the singer Yvette Guilbert; the dancer Louise Weber, known as the outrageous La Goulue ("The Glutton"), who created the "French Can-Can"; and the much more subtle dancer Jane Avril.

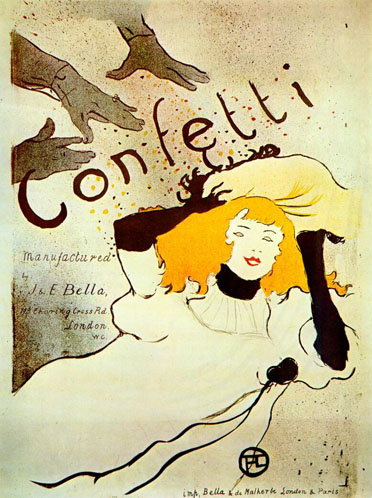

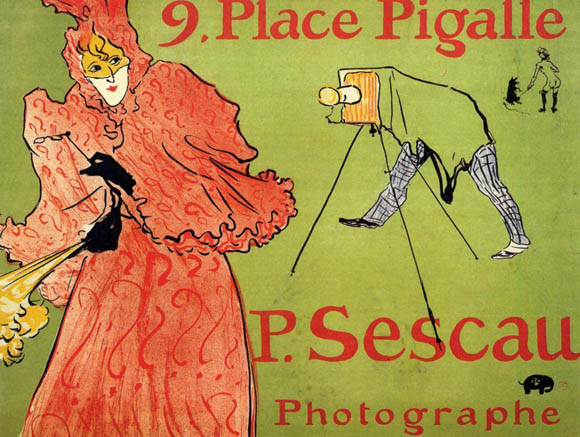

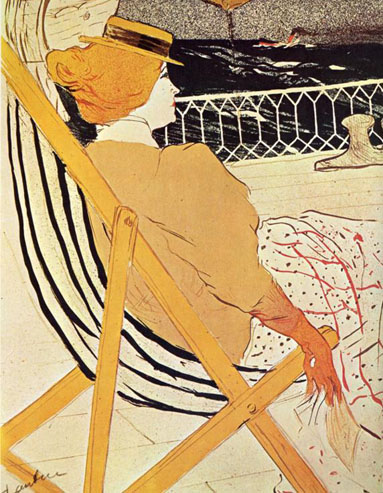

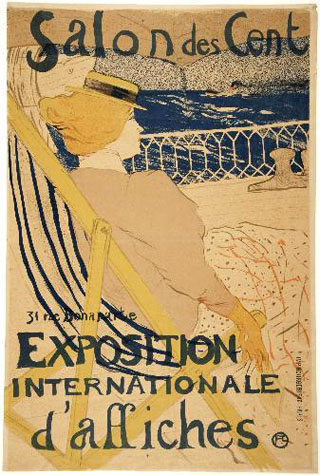

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec came from a family of Anglophiles, and while he wasn't as fluent as he pretended to be, he spoke English well enough to travel to London. The business of making posters led Henri to London, gaining him work that led to the making of the 'Confetti' poster, and the bicycle advert 'La Chaîne Simpson'.

Confetti Poster: 1894

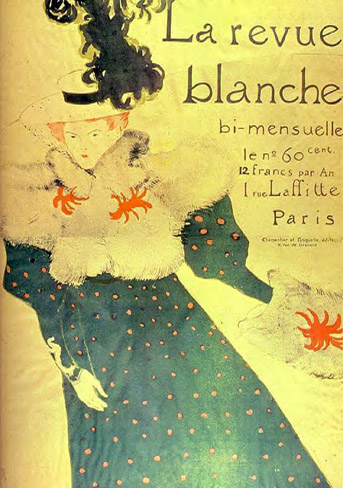

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, whose large, colorful posters were a familiar sight in Paris in the 1890s and remain popular to this day, has become a symbol of the Belle Epoque. A man of aristocratic background, he was a constant presence in the popular cafés, concert halls, and brothels of Montmartre as he sought escape from the despair brought on by physical handicaps. He also circulated freely among artists and intellectuals of the day. His poster for La Revue blanche, an adventurous literary magazine, depicts Misia Natanson, the wife of one of the editors and a celebrated muse whose salons he frequented.

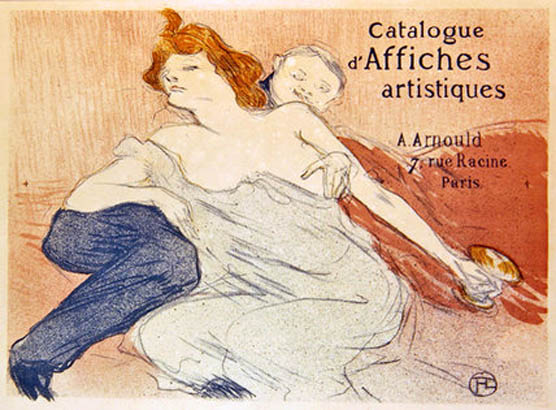

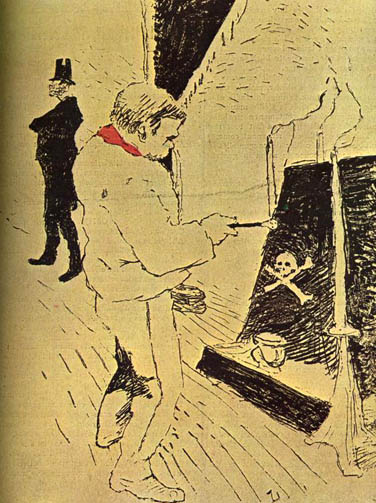

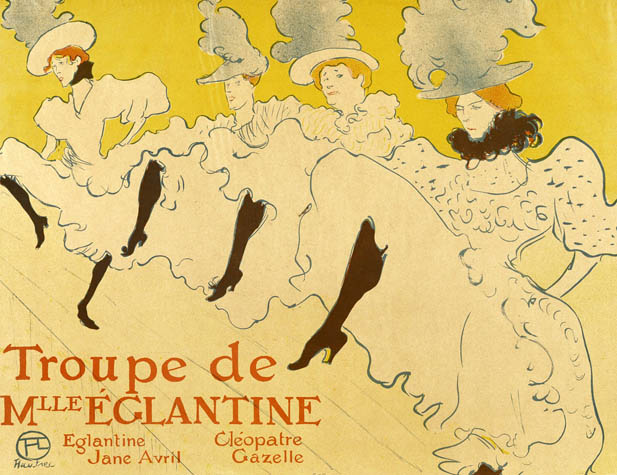

Toulouse-Lautrec took up lithography at a high point in its history, when technical advances in color printing and new possibilities for large scale led to a proliferation of posters as well as prints for the new bourgeois collector. In his short career, he created more than three hundred fifty prints and thirty posters, as well as lithographed theater programs and covers for books and sheet music, all of which brought his avant-garde visual language into a broad public arena. For technical expertise, he depended on master craftsmen to share their knowledge. One such printer, Père Cotelle of the Ancourt workshop, is seen at his printing press on the cover for the L'Estampe originale portfolio, while Toulouse-Lautrec's friend, the performer Jane Avril, inspects a fresh impression of a print.

Whether advertising a product, like the new paper form of confetti, or entertainers in a well-known can-can troupe, Toulouse-Lautrec's posters were noteworthy for their highly simplified and abstracted designs. Inspired by Japanese woodblock prints, the artist incorporated diagonal perspectives, abrupt cropping, patterns of vivid, flat color, and sinuous lines to achieve an immediacy and directness that went far beyond the illustrative charm of other poster makers of the day.

From: Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec - Confetti: 1894

La Chaine Simpson

The Simpson Chain or Simpson Lever Chain was an English-made bicycle chain invented by William Spears Simpson in 1895. The design departed from the standard roller bicycle chain: it was composed of linked triangles forming two levels. The inner level was driven by the chain-ring and the outer drove the rear cog. Instead of teeth, the chain-ring and cog had grooves into which the rollers of the chain engaged.

Simpson made claims, widely discredited, that the levers of this chain provided a mechanical advantage that could amplify energy produced by the cyclist. Simpson hired top cyclists such as Constant Huret (depicted in Toulouse-Lautrec's advertisement and Tom Linton (of Paris-Bordeaux fame), and the Gladiator Pacing Team from France to race for high stakes in England for the Chain Matches. His teams were largely successful.

Jimmy Michael attended the so-called Chain Race at Catford track in 1896. Simpson was so insistent that it was an improvement over conventional chains that he staked part of his fortune on it.

Pryor Dodge wrote:

"In the fall of 1895, Simpson offered ten-to-one odds that riders with his chain would beat cyclists with regular chains. Later known as the Chain Matches, these races at the Catford track in London attracted huge crowds estimated between twelve and twenty thousand in June of 1896. Simpson's team not only included the top racers - Tom Linton, Jimmy Michael, and Constant Huret - but also the Gladiator pacing team brought over from Paris. Pacers enabled a racer to ride faster by shielding him from air resistance. Although Simpson won the Chain Matches, they only proved that the Gladiator pacers were superior to their English rivals."

This invention would probably have been long forgotten except that:

The Simpson Chain is portrayed in a work of the French post-impressionist artist Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

The Simpson Lever Chain Racing Team employed the Belgian cyclist Hélène Dutrieu who became a stunt cyclist and pioneering aviator.

Simpson's promotions were so widespread and effective that much of his promotional material is collected today.

From: Simpson Chain - Wikipedia

It was during his time in London that he met and befriended Oscar Wilde, and when Wilde faced imprisonment in Britain, Henri was a very vocal supporter. Toulouse-Lautrec's portrait of Wilde was done the same year as Wilde's trial.

Oscar Wilde: 1895

An alcoholic for most of his adult life, Toulouse-Lautrec was placed in a sanatorium shortly before his death. He died from complications due to alcoholism and syphilis at the family estate in Malromé at the age of 36. He is buried in Verdelais, Gironde, a few kilometers from the Château Malromé, where he died.

Toulouse-Lautrec's last words reportedly were: "Le vieux con!" ("The old fool!", although the word "con" can be meant in both simple and vulgar terms). This was his goodbye to his father. Although another version has him saying, using the word "hallali" which is used by huntsmen for the moment the hounds kill their prey, "I knew, papa, that you wouldn't miss the death." ("Je savais, papa, que vous ne manqueriez pas l'hallali").

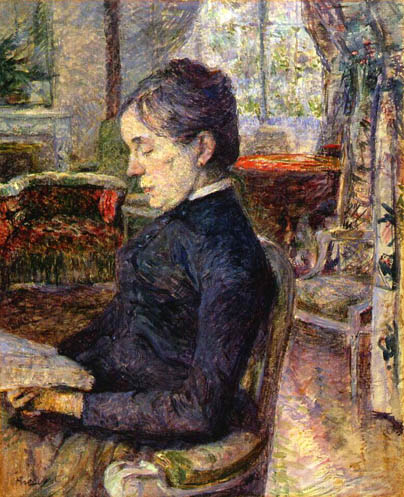

After Toulouse-Lautrec's death, his mother, the Comtesse Adèle Toulouse-Lautrec, and Maurice Joyant, his art dealer, promoted his art. His mother contributed funds for a museum to be created in Albi, his birthplace, to house his works. The Toulouse-Lautrec Museum now owns the world's largest collection of works by the painter.

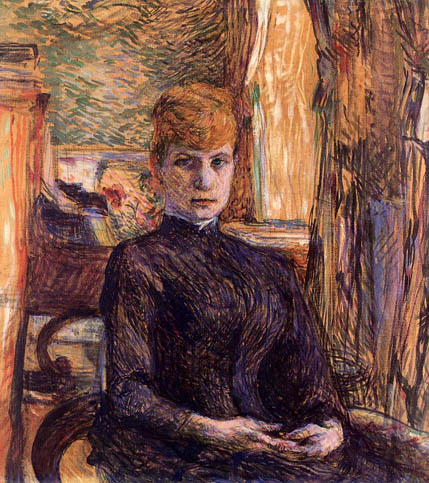

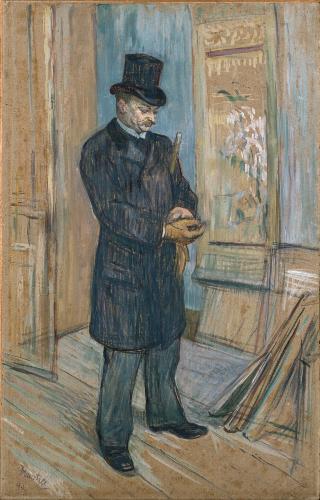

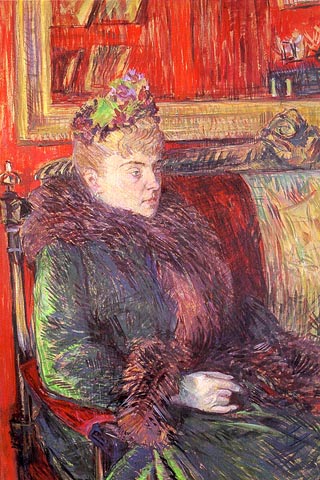

Maurice Joyant In A Summer Bay

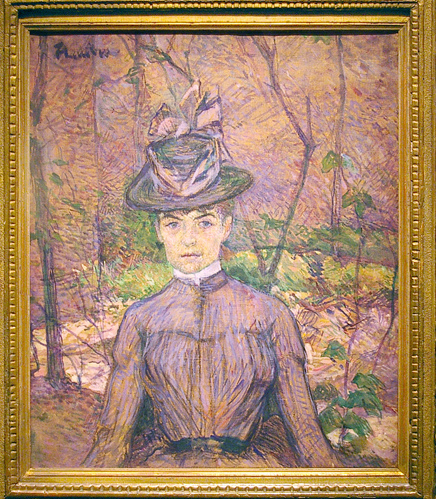

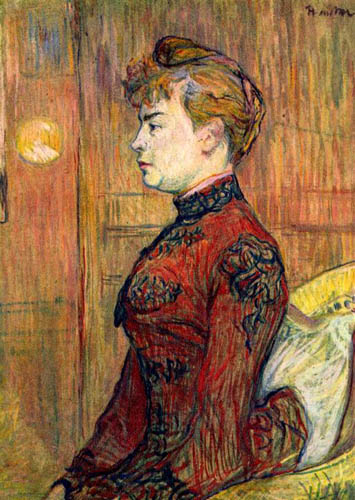

Comtesse Adele-Zoe de Toulouse-Lautrec,

the Artist's Mother: ca 1883

Adele de Toulouse-Lautrec: 1882

Madam Countess Adele de Toulouse-Lautrec in the Garden of Malrome: 1882

The Countess Adele de Toulouse-Lautrec in her salon

at the Chateau Malrome, in 1887

Throughout his career, which spanned fewer than 20 years, Toulouse-Lautrec created 737 canvases, 275 watercolors, 363 prints and posters, 5,084 drawings, some ceramic and stained glass work, and an unknown number of lost works. His debt to the Impressionists, in particular the more figurative painters Manet and Degas, is apparent. His style was also influenced by the classical Japanese woodprints which became popular in art circles in Paris. In the works of Toulouse-Lautrec can be seen many parallels to Manet's detached barmaid at A Bar at the Folies-Bergère and the behind-the-scenes ballet dancers of Degas. He excelled at capturing people in their working environment, with the color and the movement of the gaudy night-life present but the glamour stripped away. He was masterly at capturing crowd scenes in which the figures are highly individualized. At the time that they were painted, the individual figures in his larger paintings could be identified by silhouette alone, and the names of many of these characters have been recorded. His treatment of his subject matter, whether as portraits, scenes of Parisian night-life, or intimate studies, has been described as both sympathetic and dispassionate.

Toulouse-Lautrec's skilled depiction of people relied on his painting style which is highly linear and gives great emphasis to contour. He often applied the paint in long, thin brushstrokes which would often leave much of the board on which they are painted showing through. Many of his works may best be described as drawings in colored paint.

From: Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec - Wikipedia

Additional Sources

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec - Olga's Gallery

Henri De Toulouse-Lautrec - The complete works

Art Renewal Center Museum - Artist Information for Henri de Toulouse

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901) - Thematic Essay

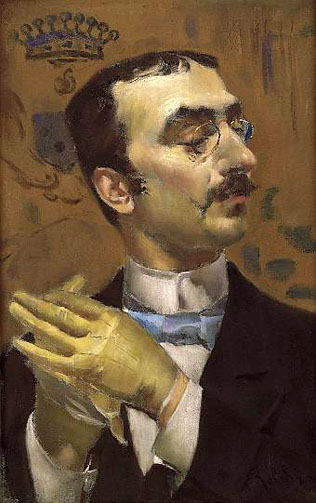

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

by Giovanni Boldini

An aristocratic, alcoholic dwarf known for his louche (disreputable) lifestyle, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec created art that was inseparable from his legendary life. His career lasted just over a decade and coincided with two major developments in late nineteenth-century Paris: the birth of modern printmaking and the explosion of nightlife culture. Lautrec's posters promoted Montmartre entertainers as celebrities, and elevated the popular medium of the advertising lithograph to the realm of high art. His paintings of dancehall performers and prostitutes are personal and humanistic, revealing the sadness and humor hidden beneath rice powder and gaslights. Though he died tragically young (at age thirty-six) due to complications from alcoholism and syphilis, his influence was long-lasting. It is fair to say that without Lautrec, there would be no Andy Warhol.

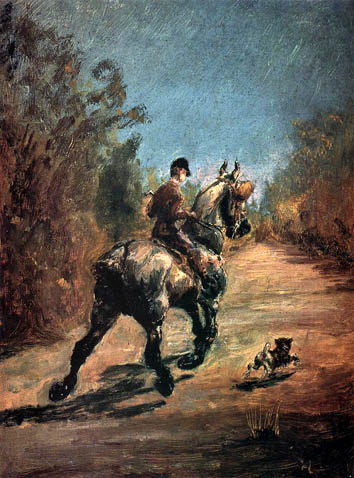

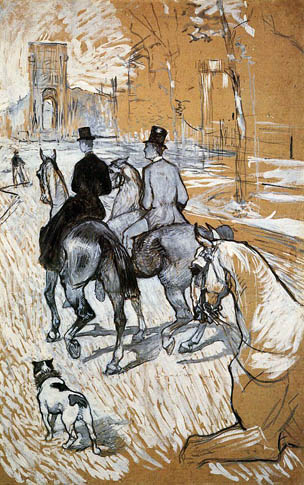

Lautrec began drawing at a young age, when frequent illnesses (portending more serious health problems to come) kept him bedridden at the family estate in Albi in southern France. His favorite juvenile subject was the horse, as seen in the sketch of Two Riders on Horseback. This probably was owed to the influence of his first teacher, René Princeteau (1844-1914), a close family friend and deaf-mute who painted fashionable sporting pictures. Lautrec's fascination for horses endured throughout his career, as seen in his 1899 work At the Circus: The Spanish Walk, one of a group of colored chalk drawings Lautrec made from memory while recovering at a sanatorium, offered to doctors as proof of his improving health.

Two Riders on Horseback: 1879-81

The Spanish Walk: 1899

Due to a genetic weakness resulting from the consanguineous marriage of his parents (who were first cousins), Lautrec's legs ceased growing after he broke both his femur bones in separate, minor accidents during his adolescence. As an adult, Lautrec had a normally proportioned upper body, but the stubby legs of a dwarf; his mature height was barely five feet, and he walked with great difficulty using a cane. Lautrec compensated for his physical deformities with alcohol and an acerbic, self-deprecating wit. His sympathy and fascination for the marginal in society, as well as his keen caricaturist's eye, may be partly explained by his own physical handicap.

In 1882, Lautrec moved from Albi to Paris, where he studied art in the ateliers of two academic painters, Léon Bonnat (1833-1922) and Fernand Cormon (1845-1924), who also taught Émile Bernard (1868-1941) and Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890). Lautrec soon began painting en plein air in the manner of the Impressionists, and often posed sitters in the Montmartre garden of his neighbor, Père Forest, a retired photographer. One of his favorite models was a prostitute nicknamed La Casque d'Or (Golden Helmet), seen in the painting The Streetwalker. Lautrec used peinture à l'essence, or oil thinned with turpentine, on cardboard, rendering visible his loose, sketchy brushwork. The transposition of this creature of the night to the bright light of day-her pallid complexion and artificial hair color clash with the naturalistic setting-signals Lautrec's fascination with sordid and dissolute subjects. Later in his career, he would devote an entire series of prints, called Elles, to life inside a brothel.

The Streetwalker: ca 1890-91

Title Page for the Suite Elles, 1896

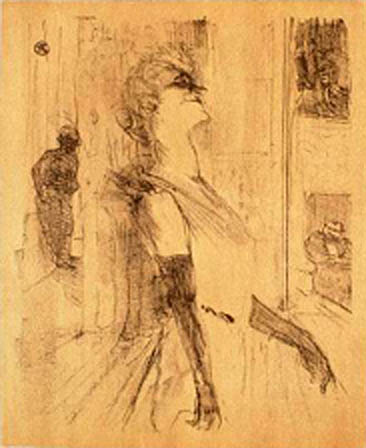

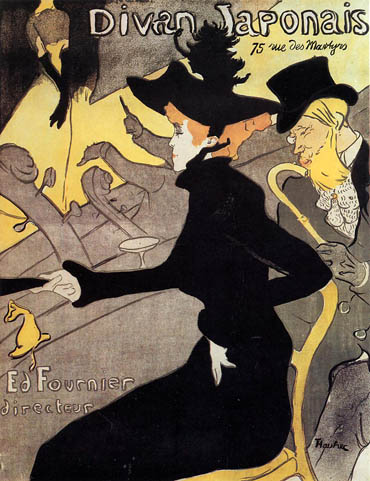

Lautrec eventually established himself as the premier poster artist of Paris and was often commissioned to advertise famous performers in his prints. One of Lautrec's favorite café-concert stars was Yvette Guilbert, who was known as a diseuse or "speaker" for the way she half-sung, half-spoke her songs during performances. She had bright red hair, thin lips, a tall gaunt physique, and wore black elbow-length gloves. Though her head is cropped by the top edge of the composition, her elongated body and trademark gloves in the upper left corner of the poster Divan Japonais leave no doubt as to her identity. Likewise, the pinched features and aloof demeanor of the singer Jane Avril, seated in the foreground of the image wearing one of her famously outlandish hats, are also subjected to Lautrec's crystallizing vision. By exaggerating the characteristic features of these women, Lautrec conveyed the essence of their personalities.

Yvette Guilbert

Yvette Guilbert (1867-1944) was the most famous cabaret star in Paris in the 1890's. Celebrated for her deadpan delivery of bawdy songs, the tall, slim Guilbert cultivated a comic stage persona that contrasted with her trademark costume of simple gowns and long black gloves. Toulouse-Lautrec emphasized this awkward elegance almost to the point of caricature in the suite of limited-edition lithographs known as "The English Series." Commissioned by the publisher W.H.B. Sands, the series of eight prints was meant to coincide with Guilbert's London premiere in 1898, which was ultimately canceled.

From: Toulouse-Lautrec and Paris

Yvette Guilbert: 1893

Yvette Guilbert: 1894

Yvette Guilbert: 1894

Yvette Guilbert: 1895

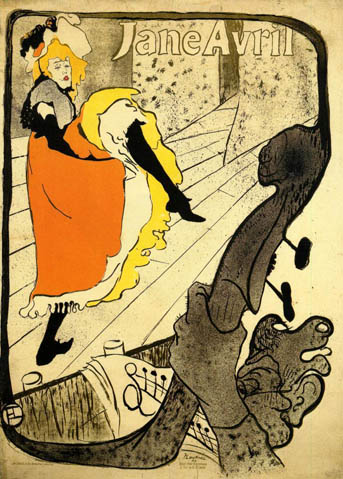

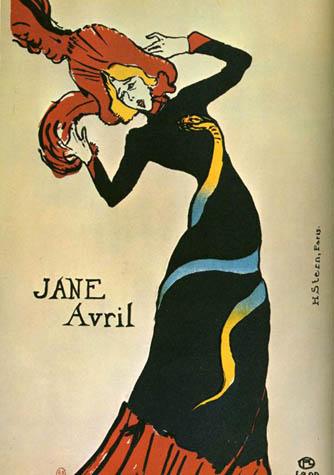

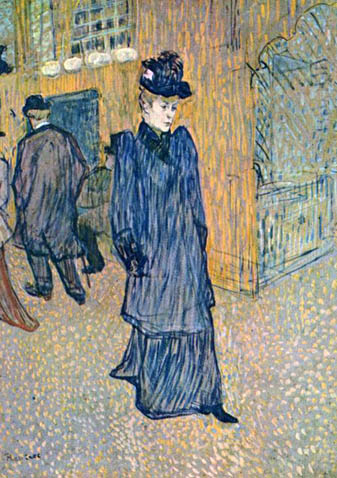

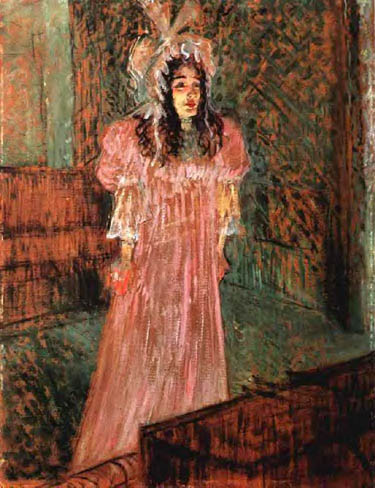

Jane Avril

Jane Avril (Jeanne Louise Beaudon, 1868-1943) made her name as a dancer at the Moulin Rouge. Between 1892 and 1899, Toulouse-Lautrec produced a series of paintings and posters that featured Avril as a performer on stage, but he also painted her as a private individual, as in the Clark's portrait. Such treatment, which the artist did not grant many of the other celebrities he depicted, suggests his respect for the accomplished Avril.

From: Toulouse-Lautrec and Paris

Divan Japonais: 1892-93

The Divan Japonais, a cabaret in Montmartre, an artists' quarter in Paris, was newly redecorated in 1893 with fashionable Japanese motifs and lanterns. Its owner, Édouard Fournier, commissioned this poster-depicting singers, dancers, and patrons-from Toulouse-Lautrec to attract customers to the opening of his nightclub. In the immediate foreground, Toulouse-Lautrec depicts two of his good friends in the audience: on the right, Édouard Dujardin, an art critic and founder of the literary journal Revue wagnérienne, and, at the center, the famous cancan dancer Jane Avril, whose elegant black silhouette dominates the scene. In the background, another well-known entertainer of the period, the singer Yvette Guilbert, performs on stage. Although her head is abruptly cropped in this composition-reflecting the influence of photography and Japanese prints-Guilbert was immediately known to contemporary patrons by the dramatic gesture of her signature long black gloves.

Lithographed posters proliferated during the 1890s due to technical advances in color printing and the relaxation of laws restricting the placement of posters. Dance halls, café-concerts, and festive street life invigorated nighttime activities. Toulouse-Lautrec's brilliant posters, made as advertisements, captured the vibrant appeal of the prosperous Belle Époque.

From: Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec - Divan Japonais (Japanese Settee): 1893

Jane Avril: 1893

The Jardin de Paris was a café-concert hall owned by the proprietor of the Moulin Rouge. One of the hall's performers, Jane Avril, is seen here dancing on stage. Avril was a favorite subject of Toulouse-Lautrec's and appears in many of his works from this period, including another poster, Divan Japonais, which, unusually, shows her as a spectator rather than a performer.

This poster demonstrates the visual juxtaposition of the beautiful and the grotesque that was so beloved of Toulouse-Lautrec: the sensuous figure of Avril contrasts sharply with that of the caricatured features of the musician playing the double-bass, his hairy knuckles are rendered all the more conspicuous by their proximity to her frothy gown.

From: Poster - Jane Avril au Jardin de Paris - Victoria and Albert Museum

Jane Avril: 1899

Jane Avril Back View: ca 1891-92

Jane Avril Dancing: 1892

Like La Goulue and the female clown Cha-U-Kao, Jane Avril was part of the night life and show business that Toulouse-Lautrec loved to portray. The daughter of a demimondaine and an Italian aristocrat, Jane Avril started to dance at the Moulin Rouge, continued her career at Les Décadents, then went on to Le Divan Japonais, before triumphing at Les Folies Bergères. Although her fragile rather ethereal look made her a figure apart in this shady world, on stage she proved to be an acrobatic dancer, full of energy and grace. She was even regarded by her contemporaries as the 'incarnation of dance'.

Using the fluidity of oil paint diluted with turpentine, the artist has caught the elegance of the dancing silhouette and the liveliness of her kicks. With the force and economy typical of his style, Lautrec sketched in broad strokes the essential of the dancer's movement and rendered a few elements of the setting in which she was performing her solo number. Two figures appear in the background, on a piece of the cardboard left almost blank. Although the woman in the hat is unknown, the man on her left is the impresario Warner who served as a model for the famous lithograph known as The Englishman at the Moulin Rouge.

A lifelong friend, Jane was at the center of several other works by Toulouse-Lautrec, and posters for Le Divan Japonais or Le Jardin de Paris, in 1893, which made the name of artist and model alike.

From: Musée d'Orsay: Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec Jane Avril Dancing

Jane Avril Dancing: ca 1891-92

Jane Avril Entering the Moulin Rouge: 1892

Jane Avril Leaving the Moulin Rouge: 1892

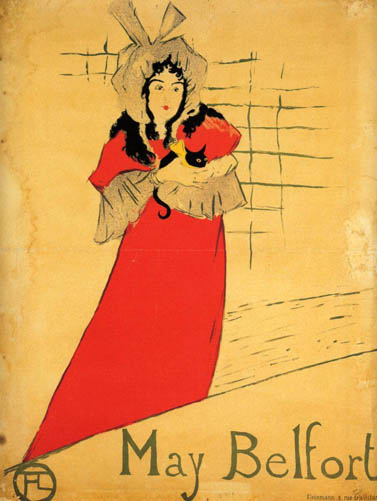

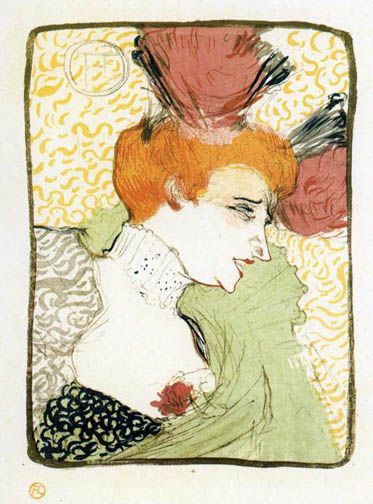

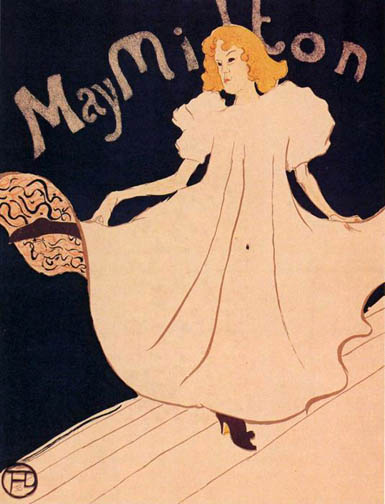

The style and content of Lautrec's posters were heavily influenced by Japanese ukiyo-e prints. Areas of flat color bound by strong outlines, silhouettes, cropped compositions, and oblique angles are all typical of woodblock prints by artists like Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) and Ando Hiroshige (1797-1858). Likewise, Lautrec's promotion of individual performers is very similar to the depictions of famous actors, actresses, and courtesans from the so-called "floating world" of Edo-Period Japan. For instance, Lautrec's poster of May Belfort can be compared with the figure of Iwai Hanshiro V (a male actor in female guise) in Three Kabuki Actors by Utagawa Kuniyasu (1794-1832).

.jpg)

Katsushika Hokusai-The Great Wave at Kanagawa

(from a Series of Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji)

Ando Hiroshige-Kinryusan Temple at Asakusa: 1856

May Belfort: 1895

Toulouse-Lautrec is acknowledged as history's greatest poster artist, although he produced just 31 colour lithograph posters, most of which advertised the decadent dance halls of Paris.

May Belfort was born in Ireland; after working in the music halls of London, she arrived in Paris in 1895, where she performed at the Cabaret des Decadents. She caused a sensation for a few months and Toulouse-Lautrec made a series of six lithographs of her.

From: Aberdeen Art Gallery and Museums

Three Kabuki Actors-Iwai Hanshiro V: 1776-1847

Three Kabuki Actors-Iwai Hanshiro V: 1776-1847 - Two

Three Kabuki Actors-Iwai Hanshiro V: 1776-1847 - Three

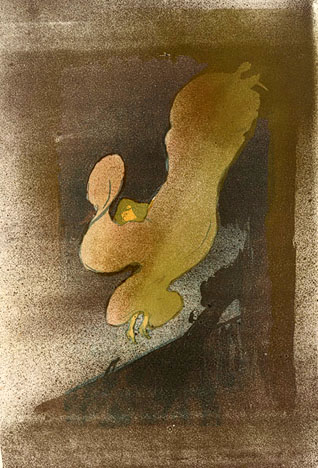

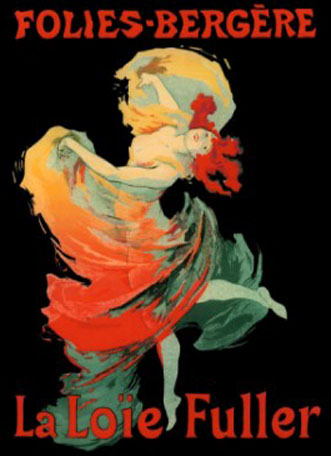

Lautrec's prints often display dazzling technical effects, as new innovations in lithography during the late nineteenth century permitted larger prints, more varied colors, and nuanced textures. The artist frequently employed the spattered ink technique known as crachis, seen in his series of prints depicting Miss Loïe Fuller. Fuller was an American famous in fin-de-siècle Paris for her performances combining dance, multicolored artificial lights (her nickname was the "Electric Fairy"), and music. As she twirled and bounded across the stage, enormous lengths of fabric would billow outward from her body and reflect the colored lights, creating a spectacular effect. Lautrec executed about sixty versions of this print in a variety of colored inks, including gold and silver, which evoke, cumulatively, the effect of her performances.

Marie-Louise Fuller

American-born Loïe Fuller (Marie-Louise Fuller, 1862-1928) was an avant-garde dancer of the Paris stage. Her Serpentine Dance-during which she swirled swaths of fabric and twirled to an accompaniment of music and multi-colored electric lights-attracted the attention of many artists, who tried to capture the dazzling visual effects of her performance in a variety of media, including photography. Toulouse-Lautrec attempted to convey the dance's ethereal magic in his minimal lithograph, in which Fuller appears as a sinuous form surrounded by yards of flowing silk.

From: Toulouse-Lautrec and Paris

Miss Loie Fuller: 1893

France, AD 1893

A remarkable image of a remarkable dancer

Loie Fuller (1864-1901) was an American dancer who came to perform at the Folies-Bergère in Paris in 1892. Her act was a huge success; she swirled long drapes around herself, extending her reach with poles, while being lit in kaleidoscopic colors and by spotlights. The flowing lines and glowing colors of her dance have been credited as an influence on Art Nouveau, and many prints and small bronzes were made of her dance. She described herself as a 'sculptor of light', and even Rodin praised her strange 'art of the future'.

This was Toulouse-Lautrec's first color lithograph that was not a poster. He produced around sixty impressions from five stones, each uniquely colored and some (including this from The British Museum) dusted with gold or silver powder to catch the light with a shimmering effect. Some survive with a passé partout mount specially designed for it. The British Museum impression is signed by Toulouse-Lautrec, and marked 'Passe': it is though that this indicates to the printer that he was content with the quality, and the edition could be run off.

From: British Museum - Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Miss Loie Fuller, a lithograph

Loie Fuller in Dance of the Veils at the Folies-Bergere: 1893

Loie Fuller: 1892

Folies Bergere

La Loie Fuller

Loie Fuller Poster

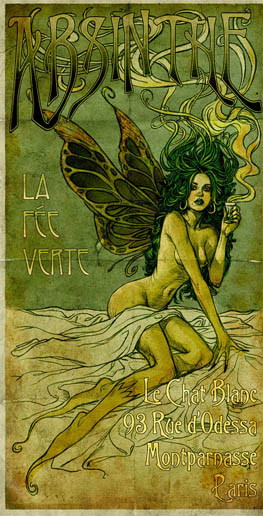

Absinthe

Absinthe has been surrounded by myth and mystery for decades - la fée verte - the "green fairy" - embraced by bohemian French artists and writers, notably Toulouse Lautrec and Vincent van Gogh although it was Oscar Wilde who described the feeling of having tulips on his leg after leaving a bar.

It was claimed that absinthe had hallucinogenic properties, now shown to be untrue, although Thujone, the active ingredient in absinthe, can cause muscle spasms in large doses.

It is now thought that any hallucinogenic effect from absinthe was probably from the many potentially toxic chemicals that were added to it in the 19th century when its popularity took off and many tried to cash in on the exotic drink.

From: ABC New South Wales

Lautrec's poignant depiction of a prostitute in the painting Woman before a Mirror offers a counterpoint to the dazzling exuberance of Miss Loïe Fuller. Nude save for her black stockings, the woman stands straight-backed as she gazes into a looking glass, dispassionately analyzing her body's attributes and faults. Meanwhile, the viewer is compelled to do the same, as we are presented with both her ample backside and her blurred reflection. Lautrec presents her neither as a moralizing symbol nor a romantic heroine, but rather as a flesh-and-blood woman (the dominant whites and reds in the composition reinforce this reading), as capable of joy or sadness as anyone. Indeed, the directness and honesty of the picture testify to Lautrec's love of women, whether fabulous or fallen, and demonstrates his generosity and sympathy toward them.

Cora Michael

Department of Drawings and Prints, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

From: Thematic Essay-Metropolitan Museum of Art

Woman before a Mirror: 1897

In this work of 1897, a woman frankly confronts her reflection, as in Degas' many pictures of women dressing and bathing. Unlike Degas, however, Lautrec makes the brothel setting evident, whereas Degas left his settings ambiguous.

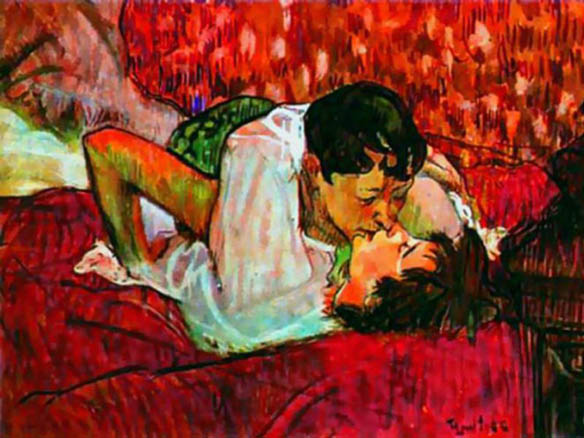

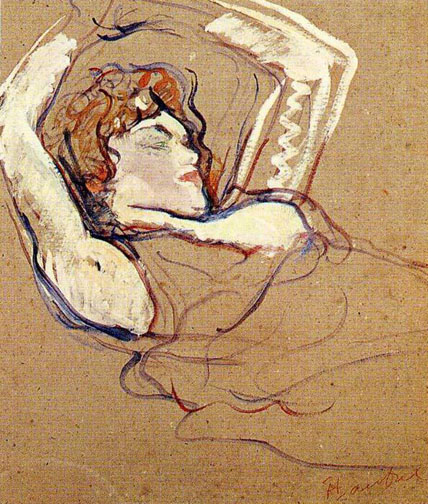

Sketches of Lesbians - Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

The Bedroom

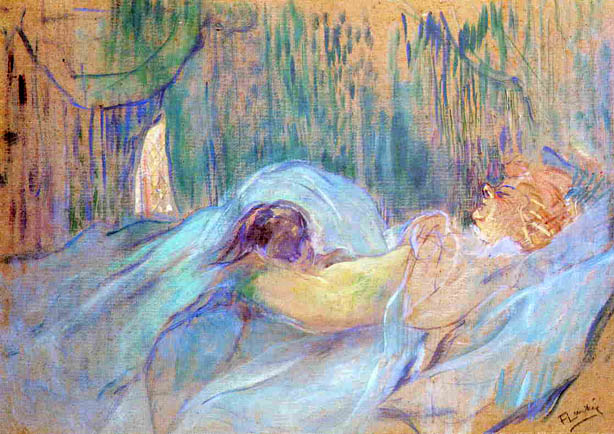

Toulouse-Lautrec's first lesbian works were sketched in the most private place - the bedroom (indicating his belief that homosexuality should be confined to secluded settings) - and are the most sensual (indicating his obsession with the scandalous matter). During the morning and afternoon in the brothels the women were together, alone and at peace. Toulouse-Lautrec reflects this relaxed ambience with the reclining embrace of the women in his sketches. In these earlier drawings, this embrace is more visible. The most provocative is The Kiss (1892) in which two women are captured on the canvas kissing other on a bed. One woman is hovering over her partner while her arm is tucked underneath the latter's back, which is suggestive of a tender, supportive embrace. The woman below her has her arm wrapped around the other's neck, drawing the woman above closer to her for support. They are holding each other very tightly. According to Julia Fey, Lautrec was best at portraying body language. (Frey "Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec") The women do not have to tell about their love; it is powerfully expressed by the natural embrace of their arms. The non-coerced tightness reflects Toulouse-Lautrec's attempt in becoming closer with the lesbians in order to better understand their situation and motives.

The Kiss: 1892

Toulouse-Lautrec soon reverses this attraction by gradually separating the lovers, reflecting his developing homophobia, as we remain in the bedroom for the painting In Bed (1892), which places two lesbians in bed next to each other. They are in an unperturbed and restful position. One has both of her arms crossed above her head while the other has her head cradled in her own arm. Both women's arms are touching each other, but slightly. The arm of the woman on the right is supporting the arm of the woman on the left. The scene appears quite natural because the pose is relaxing, nurturing, and innocently intimate. However, the embrace is not as strong as it was in The Kiss. The couple is not hugging and, for the most part, the women are keeping their arms to themselves. According to Sweetman, "The women are lying together…clearly absorbed in each other, yet with no sign of closer physical contact." (Sweetman 362) Toulouse-Lautrec purposefully separates them even though he knows that they were usually actively embracive, such as in The Kiss. We are now beginning to see some ambivalence in Toulouse-Lautrec's judgments about the openness of the embrace. Strangely, the determined artist, who found the relationship between the women an intriguing affair by saying, "This is better than anything else. There is the very epitome of sensual delight," now appears to be questioning his interest. Why was he drawing the women away from each other? What did he fear? We can best theorize that he was having second thoughts about this scandalous display of affection. There was something about these relationships that he disapproved. He probably still retained his conservative ideals that stemmed from his aristocratic upbringing, therefore being skeptical about the liberal ideals of lesbianism

In Bed: 1892

It may sound reasonable to say that Toulouse-Lautrec's movement towards less intimate lesbian works was due to his wariness of the critics' response, but this is not the case. By the 1890's Toulouse-Lautrec had been popularly accepted by the Montmartre community due to his eccentric personality and artistic innovation. According to Sweetman, Toulouse-Lautrec was "accepted by the avant-garde yet also by a wider public who knew his work was an integral part of the most exciting places of amusement in the city." In 1893, after he had produced The Kiss and In Bed, he participated in eight exhibitions consisting of paintings and lithographs of Montmartre's public view on nightlife with which everyone was familiar. Sweetman adds that "all were of subjects that encouraged the idea that he was the artist of Parisian show business, the 'Master of the Moulin Rouge', the portraitist of the stars rather than someone concerned with deeper social issues" such as lesbianism. The fact that none of the works in his exhibition were about the more sensitive issues such as homosexuality hints at the possibility of homophobia. He still was not feeling strongly or comfortable with this issue. A conflict between his bohemian desires to explore the underbellies of society and his traditional platform was constantly being battled out in his conscience. He was obsessed with these lesbians and later chose to portray them individually, but did not prefer them together, finding the intimacy too repulsive for his moral standards. He often commented about the lesbians; for example, he said, "These women are alive!" The quote seems derogatory, as if he is saying the women are alive in a monstrous, animal-like manner. Also, according to Julia Frey, "It was not uncommon for him to refer in conversation to the women as abstract parts: disparate limbs, organs." Toulouse-Lautrec nearly picks apart these lesbians part by part, hardly demonstrating any respect that many critics thought he had for these women. He may have likely viewed them as non-human beings and saw their passion for each other as just another humorous and curious spectacle. In reality, he did not know how to properly respond to this behavior and decided to slowly withdraw from these private brothel investigations due to his latent homophobia.

From: Toulouse Lautrec's Sketches of Lesbians - The Bedroom

I find it very difficult to accept the author's view of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec as a homophobe. Homophobia is consistant with the aristocracy of his day but I am not sure they reflect the 'Toulouse-Lautrec' we find in the Montmartre community of his own day. There is another In Bed: 1892 though it may be a forgery is attributed to Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

~ Senex.

In Bed - The Kiss

From Embrace to Embarrassment: Toulouse-Lautrec's Uneasiness with Lesbians "Coming Out"

Keerthi Shetty, Princeton Class of 2009

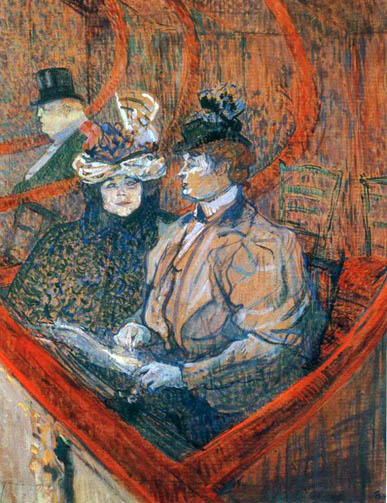

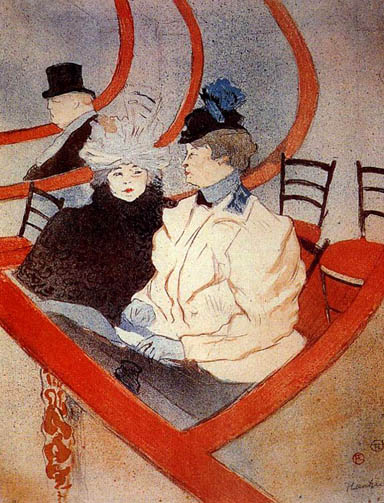

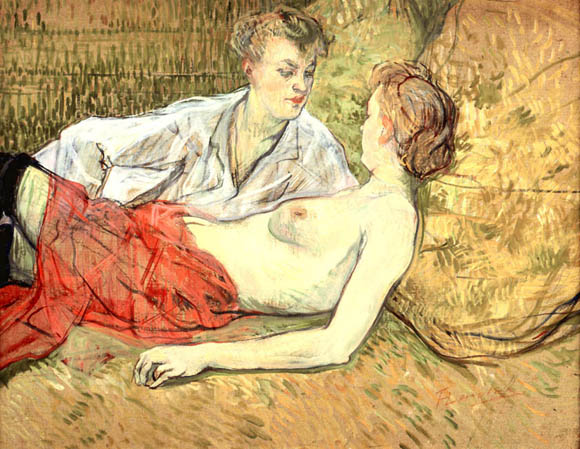

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec had obtained a backstage pass in the late 1880's to something many men could only dream of having: a private viewing of prostitutes sensually embracing each other. He was deeply moved by their natural intimacy, which influenced him to launch a series of lesbian artwork on the true affairs of these women. Such a taboo topic should not be surprising considering the artist's flamboyant and carefree behavior. He was known for being indifferent to public opinion and having an obsession with risqué elements. According to Julia Frey, "He liked all the underbelly of human behavior, all the things people hid beneath a veneer of social niceties and hypocrisy." In his most familiar lesbian work At the Moulin Rouge: The Women Dancing (1894) the avant-garde artist steps across the boundaries of "social niceties" as he displays two women embracing each other while waltzing in a café concert. They are holding hands and have their arms wrapped around each other. The focus of the painting is on the open embrace between the women. For Edward Lucie-Smith, "The picture is one of the first statements of Lautrec's fascination with lesbian activity, which later seems to have become an obsession." At the Moulin Rouge: The Women Dancing opened up the critics' eyes to the clandestine world of the demimonde. Many critics believe that Toulouse-Lautrec actually sympathized with the lesbians. According to Nret, Toulouse-Lautrec found them "melancholy, human, moving." Andre Fermigier adds to this conception by saying that the Toulouse-Lautrec felt a "bond of sympathy" with these women. The critics believed the artist sketched them for pity's sake and was attempting to show a more graceful side of lesbianism. Therefore, from the rest of Toulouse-Lautrec's works reflecting the "obsession" with the lesbians, perhaps the critics concluded that he continued to comfortably embrace this theme by significantly developing the women's embrace throughout the years as a gesture of sympathy.

At the Moulin Rouge, the Two Waltzers: 1892

But was Toulouse-Lautrec really as liberal and accepting as we think he was? He definitely painted voyeuristic material, but if we analyze these paintings and sketches further, we begin to see that he may not have been at ease with the subject matter. Initially, he drew the lesbians in order to portray the truth about them - they truly loved each other. The profound artist even proclaimed his motto to be "I seek the true, not the ideal." Perhaps the truth is that he was beginning to fear this homosexuality. Most of these sketches were not publicly viewed, even though we would think Toulouse-Lautrec would want to disclose the reality of the brothels. In fact, just as lesbianism was becoming more visible in café concerts, Toulouse-Lautrec made his lesbian art less sexual by distancing the women further apart from each other. The provoking appeal of the topic fades along with the dissolution of the embrace, as if the ostentatious Toulouse-Lautrec was actually attempting to permanently hide the ulterior motive of these paintings because he was becoming more conservative in his ideals. We can best hypothesize that he sketched these lesbian drawings for his own sake in order to make himself more comfortable with the topic. Toulouse-Lautrec developed furias, or "serial obsessions" according to Julia Frey, with the more scandalous subjects. Even if the artist was uneasy about it, he had a certain infatuation for these fallen women, but the fascination soon waned within the five years he spent studying them along with the lesbians' embrace in his sketches. Perhaps he was not able to attain the comfort zone he had expected. Through the change in the women's embrace, we can see Toulouse-Lautrec's own insecurities about his acceptance of his own Sapphic, or lesbian, work emerge, indicating his latent homophobia.

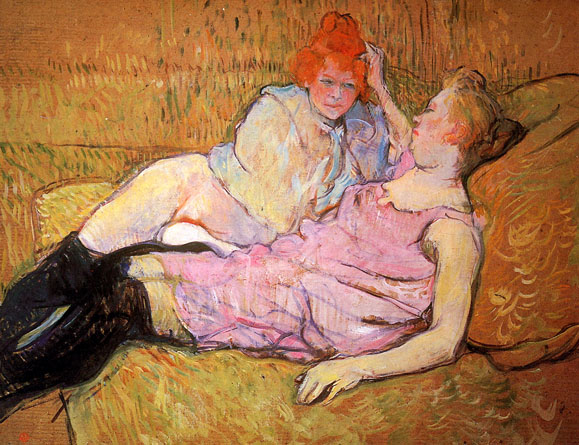

Are They Lesbians?

As a result of this phobia the women in Toulouse-Lautrec's images continue to drift apart from each other, suggesting his desire to drift away from his study of the lesbians. Now we cannot tell if the women are lesbians. For example, in 1894 he produced The Two Girlfriends. The two women are sitting on a plush divan, but it is not obvious that they are lesbians. One woman's arm is placed on the waist of her partner whose arms are covered by a blanket. The embrace does not appear vulgar but rather a friendly support as the woman who is being cuddled is not returning any sexual gesture. The distance between the two women is greater than that between the women in the earlier bedroom scenes. We can presume that Toulouse-Lautrec was attempting to make his sketches less recognizable as being lesbian ones. He did want to be tagged as the artist famous for his homosexual studies. If he were, it would be hypocritical considering our hypothesis that Toulouse-Lautrec was homophobic. Even though Lesbianism was becoming more prominent in Paris at this time, Toulouse-Lautrec was still uncomfortable with his own Sapphic artworks and was slowly pulling away from his liberal notions.

The Two Friends: 1894

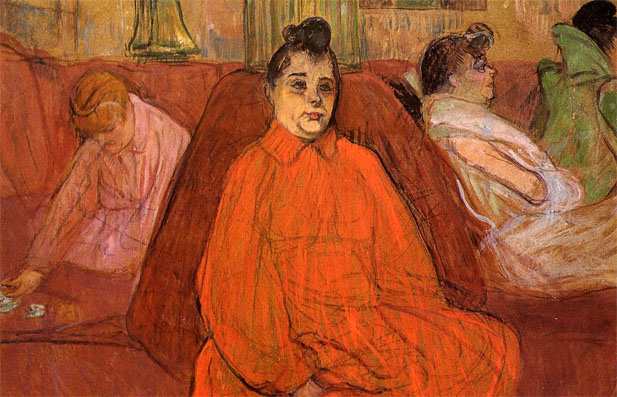

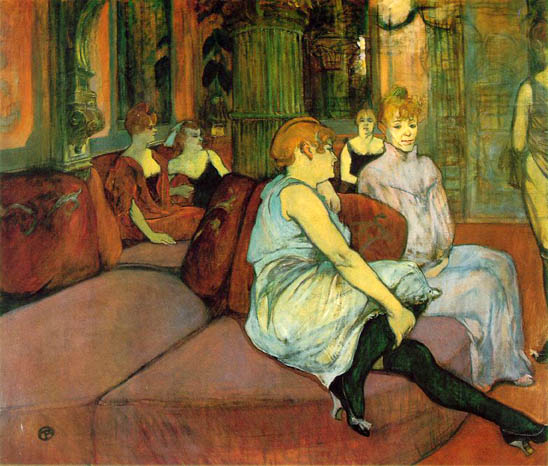

Throughout the 1890's Toulouse-Lautrec visited brothels in Paris and spent days observing the women there. A series of paintings on this theme culminated in 'Au Salon de la Rue des Moulins' of about 1894 (Albi, Musée Toulouse-Lautrec), which depicts the women sitting awaiting their clients.

This painting may represent an early stage in the genesis of the Albi picture, but it also belongs to a series of paintings focusing on the friendships between the women which often, as here, portrayed intimate moments or gestures of companionship or sympathy.

From: Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec - The Two Friends - The National Gallery, London

The Turning Point

A conservative evolution is evidenced by Toulouse-Lautrec's not having released any of his lesbian artwork for public viewing. He only allowed "worthy" people whom he could trust to take a peek at the scandalous material. We can imagine that Toulouse-Lautrec often kept these works locked away simply because they were meant for private purpose; that is, he sketched them in order to better understand the homosexual attitude himself. He did not want the general public to know that he was interested in the lifestyles of these lesbians. Finally, in 1894, Toulouse-Lautrec's Sapphic sketches were discovered by his uncle Charles Toulouse-Lautrec (a sketch of him is below). The artwork was hidden at his family home in Albi, and when his Uncle Charles found them, he was furious. He considered them to be a disgrace to the family and publicly burned them. This incident perhaps deterred Toulouse-Lautrec from drawing explicit lesbian scenes since he still respected his family's attitudes. Not all of the conservative values of his aristocratic background were shed when he moved to Montmartre. Perhaps after this incident he asked himself whether or not it was worth sketching lesbians since he was still not totally comfortable with exposing this material. Undoubtedly, this event affected the following Sapphic works. Toulouse-Lautrec was careful about portraying the lesbians as he further separated the subjects and made them appear less intimate and Sapphic by eliminating the embrace in the sketches and paintings that followed in the next year.

Charles Toulouse Lautrec

Abandonment

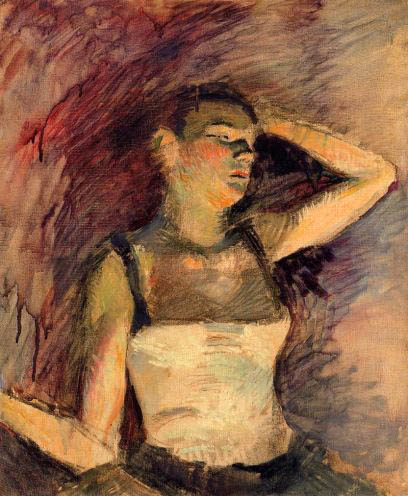

In these final Sapphic works, which were painted in 1895, we notice the definite separation of the women, defining Toulouse-Lautrec's fears of the bond between them. By this time Lautrec had been painting fewer lesbian works and began to move on to caricatured lithographs and circus scenes. Initially he was intrigued by the relationships of the women but appears to have felt a conservative pull due to his aristocratic influence and the damage done by his dear Uncle Charles. In the first of these final works, Le Sofa, the embrace of the women is totally abandoned. One of the women is propped up by a bent arm while the other is lying on her back on the sofa with an arm dangling at her side. They are not embracing each other. There is noticeable empty space between the two women. An invisible barrier appears to exist in this gap. Again, as with the previous sketch The Two Girlfriends, a viewer cannot tell if these women are lesbians. The relationship between the two women does not appear to be sexual but rather more friendly and conversational. The woman who is reclining appears uncomfortable. She is leaning further back into the divan, attempting to further distance herself from the woman above. In a similar manner, Toulouse-Lautrec is distancing himself away from these women, thus being less acknowledging of the lesbians. The embrace in his artwork has certainly been effaced.

The Sofa: ca 1894-96

The lack of embrace is manifest in the title of the final painting, Abandon. The women are in similar positions as in the previous two paintings, but we now see the back of the propped-up woman, and the reclining woman's arm is placed across her forehead. They are not embracing each other, and the position of the arm on the forehead almost seems to give a signal for the hovering woman above to stay away. Toulouse-Lautrec is blocking our view of what the women are doing with each other as the women's back is the object of obstruction. He does not allow us to enter the real world of these women. Any notions of embrace are abandoned. The painting is more conservative than the others and appears more as if the women are just engaging in conversation rather than in sexual activities. Still, Toulouse-Lautrec did not dare to exhibit these paintings even though they were less provocative. Regarding Abandon O'Connor states, "The realism of the approach used by Lautrec here would have made a scandal had the painting been exhibited." Toulouse-Lautrec did not feel that he could take the risk of displaying scandalous material which he himself in the end did not fully accept. Toulouse-Lautrec, the artist known for his laissez-faire attitude, was finally abandoning his furia with the lesbians and was unable to fully accept the existence of their relationship.

Abandon, The Two Friends: 1894-95

These two paintings may lack the very elements needed to evoke a message of sexuality and especially of lesbian love as our author attempts to direct our thinking. Yet, I would suggest there is much to be seen in what we cannot see in each painting. There is activity that can be assumed and even intimate sexuality if you wish to direct one's thinking in that direction. It could also be neither and that is where art relies on individual human imagination to provide what is missing. That is the mystery of love and art, so the answer must be yours.

~ Senex Magister

Nota Bene: As I think many of you already realize, this portion of my page dealing with Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec sexuality and attitudes toward lesbians came from a student project at Princeton. I think her work was thorough and well done, but I just don't agree with all her conclusions.

Selected Works of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

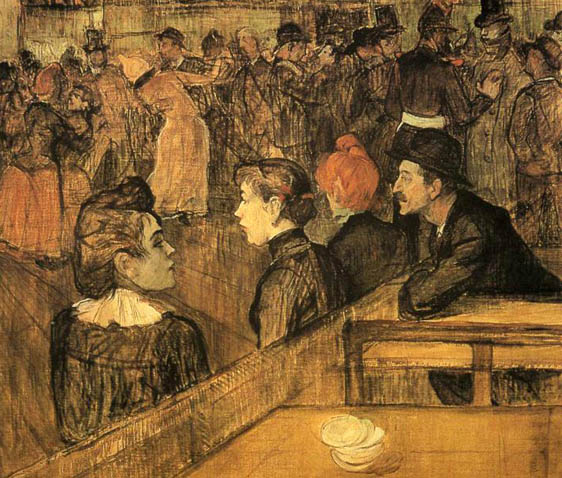

A Ball at the Moulin de la Galette: 1889

A Corner of the Moulin de la Galette: 1891

The seamy underside of the Parisian demimonde, the singers, dancers, and patrons of Montmartre nightclubs, the notorious whores of the district and their clients were Toulouse-Lautrec's principal subjects. Scion of one of France's great aristocratic families, Lautrec was afflicted in youth by injuries that stunted his growth. He was encouraged to draw during his long convalescence and permitted professional training in an academic studio, which he deserted to embrace modernism. Lautrec particularly admired Degas and emulated his unusual perspectives and gritty social realism. He mastered the new medium of color lithography and produced an impressive body of posters and printed illustrations which share the incisive linear quality of the design of this painting.

Isolated by his painful physical deformity, Lautrec became an alcoholic and a denizen of dance halls and nightclubs in Montmartre, a poor working class neighborhood untouched by Baron Haussmann's renovations of Paris. Insight gained from his handicap and his emotional remoteness from his subjects gave his depictions special force, bitterness, and sympathy, while the artifice of his preferred settings and the disguised role playing of his subjects could alter reality amusingly or grotesquely in his work. Lautrec was an observer, a voyeur rather than a participant, and alienation is endemic even in the crowded Corner of the Moulin de la Galette.

From: A Corner of the Moulin de la Galette

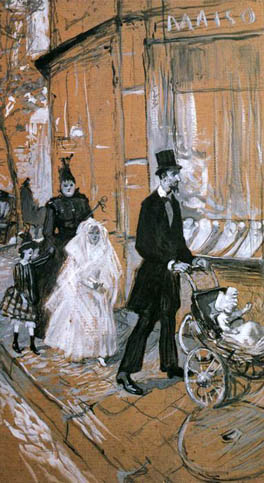

A Day Out: 1893

A Laborer at Celeyran: 1882

A l'Elysee Montmartre: 1888

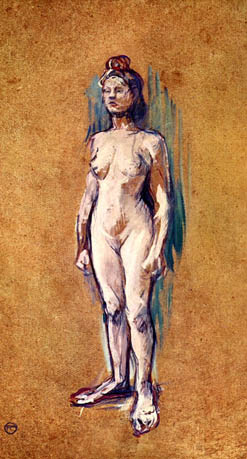

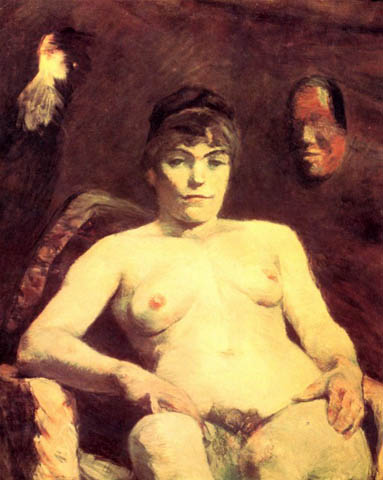

A Nude Woman

A Worker at Celeyran: 1882

Academic Study Nude: 1883

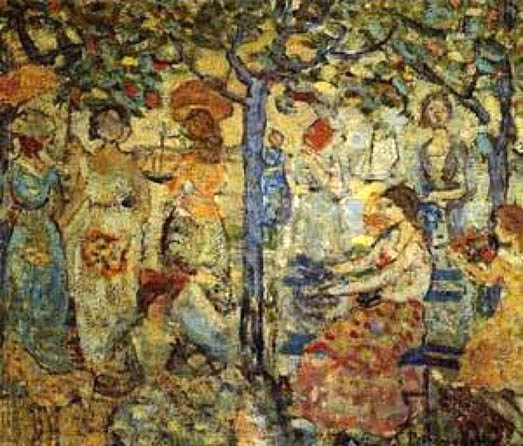

Acadia: 1918-23

Admiral Viaud: 1901

Alfred la Guigne: 1894

Allegory-Springtime of Life: 1893

Alone: 1896

This astonishing study on cardboard is a sketch for a lithograph published under the title Lassitude in the album Elles published in 1896. One can see a woman lying on her back on an unmade bed. The series Elles illustrated the artist's close acquaintance with brothels. He frequented these establishments from 1892 onwards, and was happy to move in permanently in order to observe the girls at his leisure.

Unlike the Naturalist writers of his time, Zola, Maupassant, Huysmans and the Goncourt brothers, Toulouse-Lautrec looked at the world of prostitution without making any moral judgment. Rather than painting professional models in conventional poses, he preferred to sketch these ladies at unselfconscious and spontaneous moments. La peinture à l'essence, a fluid and rapid medium, is used here to produce an almost instantaneous picture. The model, indistinctly drawn, has been captured as she is, in a position of complete abandon, with her black stockings contrasting with the folds in the faintly drawn sheets. Toulouse-Lautrec, the painter of modern life, here anticipates the Expressionist figures of Gustave Klimt and Egon Schiele, as well as those of Picasso's blue period.

From: Musée d'Orsay: Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec Alone

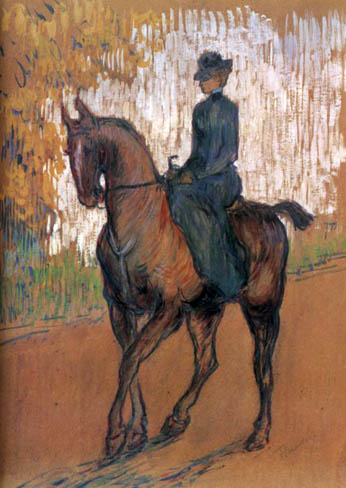

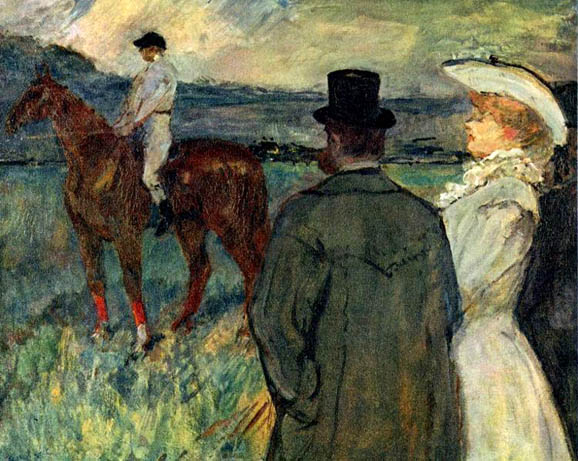

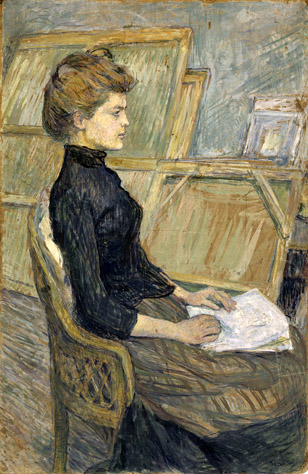

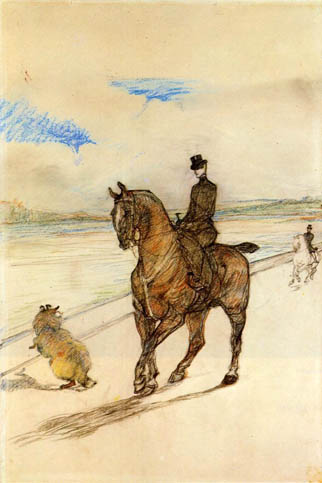

Amazone: 1899

It has been suggested that this horsewoman may be Mme Victorine Hansman, an Englishwoman who was a dealer in horses and ran a fashionable riding-school (Lautrec apparently met her at the racecourse at Auteuil and made a drawing of her in 1899), but the identification seems uncertain. There is a slightly smaller drawing (Dortu D.4.544) of 1899 in black and colored crayons in which the horse and rider are almost exactly the same, but which shows more of the setting in the Bois de Boulogne, with a dog on the left and a man on horseback in the middle distance on the right. Lautrec also made a related lithograph in the same year ('Horsewoman and Dog') of a rather similar horse and rider but in reverse, facing to the right, and with a small dog in the right-hand corner sitting in front of the horse.

From: Tate Collection - Side-saddle by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

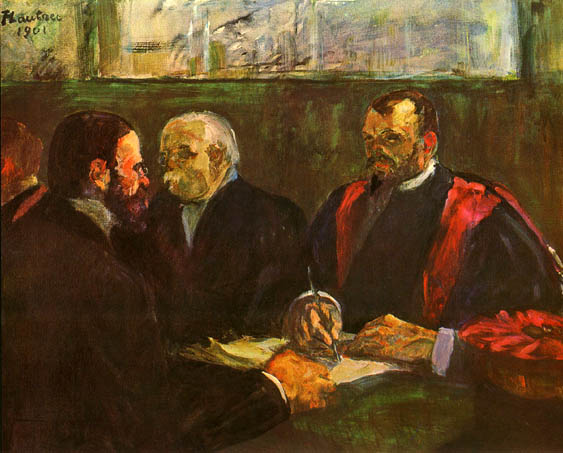

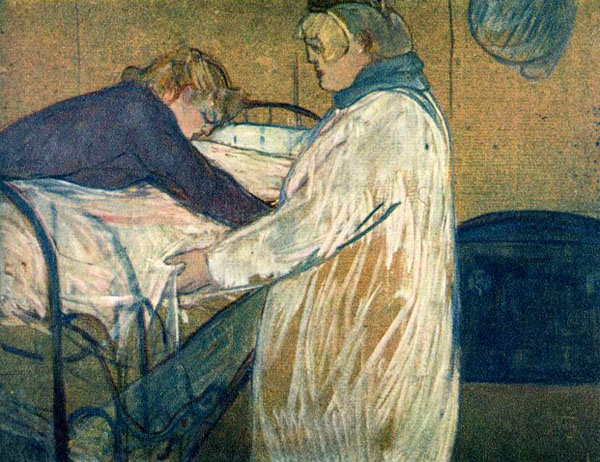

An Examination at the Faculty of Medicine: 1901

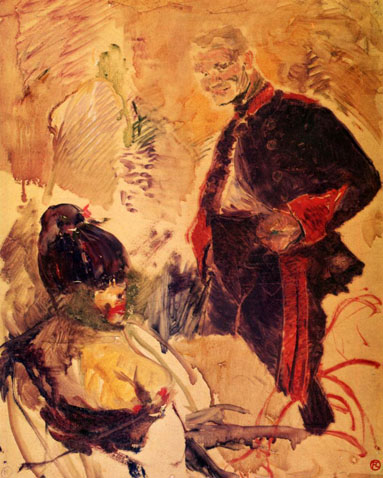

Artilleryman and Girl: ca 1886

Artilleryman Saddling His Horse: 1878 or 1881

At Gennelle, Absinthe Drinker: 1886

_1889.jpg)

At La Bastille

(aka Jeanne Wenz): 1889

At the Bar Picton, Rue Scribe: 1896

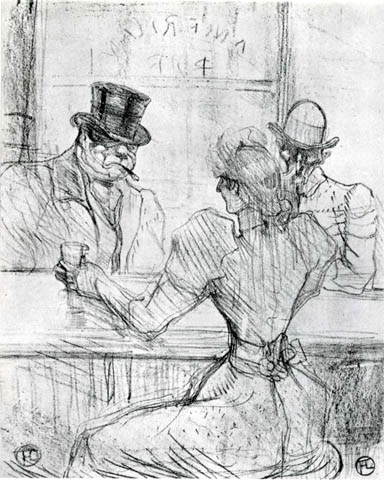

At the Cafe - The Customer and the Anemic Cashier: ca 1898-99

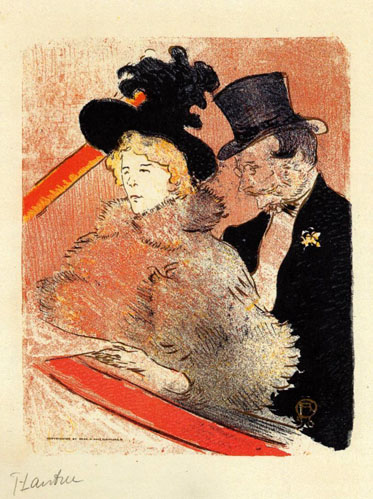

At the Concert: 1896

At the Moulin de la Galette: 1889

With Moulin de la Galette, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec continued his large-scale explorations of raucous Parisian nightlife. The pictured venue, situated at the top of the Montmartre hill, was also represented by Pierre Auguste Renoir in one of his most famous paintings (1876; Paris, Musée d'Orsay). Compositional parallels suggest that Toulouse-Lautrec may have had Renoir's Ball at the Moulin de la Galette in mind when executing his own version of the theme. In mood, however, the two works are antithetical; indeed Toulouse-Lautrec may even have set out here to produce a dark corrective to the Renoir. Rather than a sun-dappled gathering place for wide-eyed, innocently hedonistic youths in their Sunday best, Toulouse-Lautrec portrayed a gloomy dance hall with a dowdy, lower-class clientele. While the animated figures arrayed frieze like across the top of the canvas suggest the pleasurable buzz of social interaction, they also possess a tawdry aspect. Even without the inclusion of a uniformed member of the garde républicaine at the upper right, we would sense the presence of troubling energies. Isolated in the foreground, seated on either side of an oblique barrier, are three impassive women and a man whose predatory demeanor suggests he is their pimp. Spatially proximate but psychologically remote from one another, their joyless expressions indicate that they are all business.

Toulouse-Lautrec here applied a somber palette in a deliberately approximate manner, apart from the faces in the foreground, which he delineated with cold precision. Much of the paint seems more stained than brushed onto the canvas. Apparently arbitrary vertical streaks and drips, together with the sickly green tonality, create a subaqueous, unsavory atmosphere. The work's combination of hardened physiognomies and smeary handling left its mark on the young Pablo Picasso, whose forlorn bohemians and sad clowns are spiritual descendants of Toulouse-Lautrec's dispirited pleasure-seekers.

From: Interpretive Resource - The Art Institute of Chicago

At the Moulin de la Galette: 1891

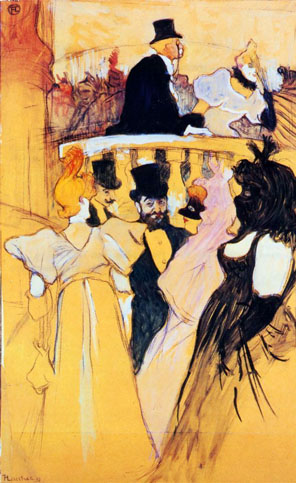

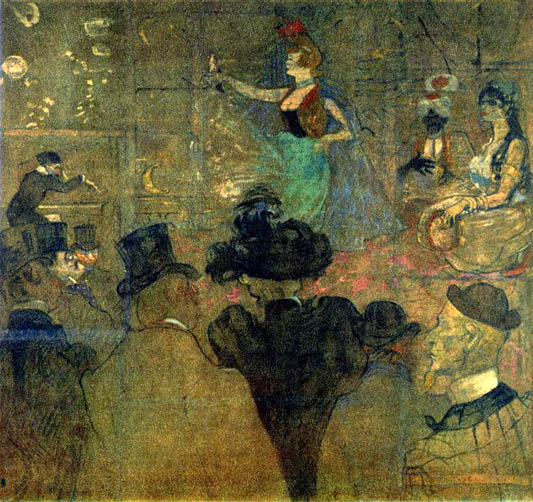

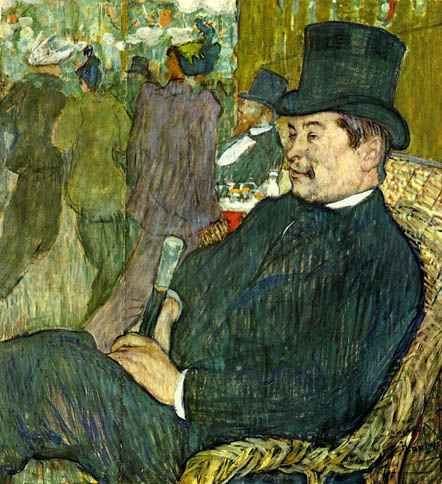

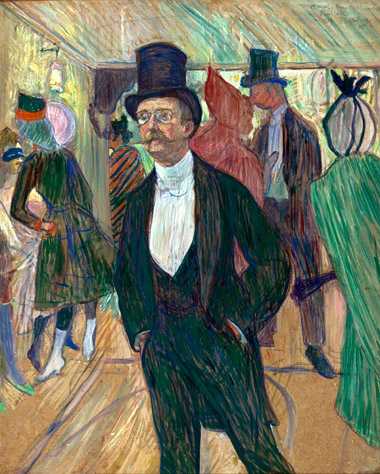

At the Moulin Rouge: 1892-93

The painting At The Moulin Rouge (1892-93) depicts many of the performers and spectators at the cabaret, and suggests that there was an intimacy between audience and spectators. The tables occupy the periphery of the dance floor; there was no stage to form a boundary between performers and audience. The red hair of Avril takes centre stage in the painting; the scandalous La Goulue (another well known dancer at the time) is seen with raised arms in the background, where the diminutive figure of Lautrec can be made out.

The ghostly face of May Milton, one of several English performers, looms into the canvas from the right.

From: Artyfacts - online journal of film, painting and architectural events in London

At the Moulin Rouge - The Beginning of the Quadrille: ca 1892

At the Nouveau Cirque, The Dancer and Five Stuffed Shirts

At the Opera Ball: 1893

At the Piano Madame Juliette Pascal

in the Salon of the Chateau de Malrome: 1896

At the Races: 1899

At the Salon, the Divan: 1893

At the Table of M and Mme Thadee Natanson: 1895

_1870_80.jpg)

Au bal: 1870-80

Aux Ambassadeurs, Gens: Chics_1893

Ballet Dancers: 1885

Behind the Scenes: ca 1898-99

Brothel on the Rue des Moulins-Rolande: 1894

In 1894, Toulouse-Lautrec moved into a brothel that had just opened at number 24, rue des Moulins. He painted several pictures representing the portraits and the daily activities of the other brothel residents, especially one of them, 'Rolande', of whom he painted two works. Representations of brothels abound in the art of the late 19th century, in the works of great artists such as Courbet and Degas, which should not be surprising at a time when the issue of prostitution was subject to heated debates. Lautrec was interested in the representation of women in bed since the beginning of the 1890's, and perhaps we should see there a reference to a scene treated by Courbet as early as 1860. Additionally, it seems very likely that besides the representation of a subject treated by his contemporaries Verlaine and Catulle Mendès, Toulouse-Lautrec saw in these marginal behaviors an echo of his own physical and moral suffering. Also, strangely enough, Toulouse-Lautrec's works suggest the most tenderness and intimacy of those depicting the brothels. The thick cardboard used as the background is characteristic of Toulouse-Lautrec's technique; he painted straight from the paintbrush without preparatory drawing, using the color of the material as the background of the work. His mastery of the arabesque and his supple and concise lines show the influence of Japanese etchings.

From: Welcome Foundation Bemberg

Bust of a Nude Man: ca 1882

Ballet de Papa Chrysantheme: 1892

Celeyran-View of the Vignards: 1880

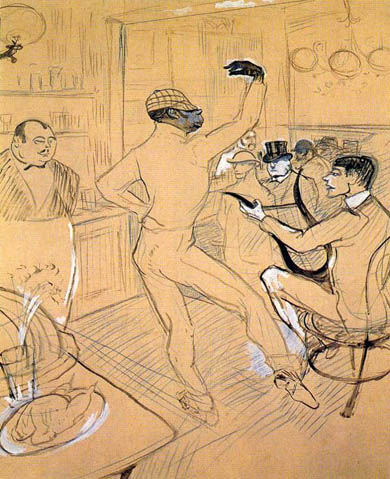

Chocolate Dancing at Achille's Bar: 1896

Cissy Loftus: 1894

Cecilia Loftus - The Golden Age of British Theatre

Coffee Pot: ca 1884

Count Alphonse de Toulouse-Lautrec, the Artist's Father,

on Horseback in Circassian Costume: 1881

Crouching Woman with Red Hair: 1897

* This is from another student assignment.

I keep wondering why he was so fascinated by the very bottom of society, and of course especially the prostitutes. Was it because he really did admire them, or did it just come from the fact that they were more or less the only women, who would talk to him? It seems to me like he's genuinely interested in them as human beings, and I honestly think that he got a lot of his inspiration from their strength. He was creating beautiful illusions, just like them, whether they were singers, dancers or prostitutes, and like they were trapped in poverty, he was trapped in his weak and strange looking body. Perhaps it also had to do with his general fascination of the body as an object of art: "Nothing exists but the (human) figure; landscape is nothing ... but an accessory." (Life, 1950, p. 94)

Sometimes I'm even tempted to think that he is being ironic about sexuality. Take for instance his painting 'Crouching Woman With Red Hair' (1897). This is definitely not a very flattering way to portray a female body. She looks more like someone who has been told to pretend being a horse, even though she doesn't want to, than an attractive redhead. I don't really understand his fine art, and I can never figure out whether he is being serious or not. His posters however are made so well, that even an ignorant student like me gets it. That deserves some recognition!

Toulouse-Lautrec's posters personalize the performers so much, that they make me more interested in the person behind the performance, than in the performance itself. I guess that is why his posters stand out, and why they worked so well. To know the person, you go see the show, and the show automatically gets better, if you're already a fan of the performer. Lautrec understood this, and he understood how to communicate, through a painting, his own personal interest in a person. I think Lautrec had a lot of empathy for his surroundings, and I think that was what kept him going. Having so many problems of his own, I think he eased his own existence by taking on other people's misfortune, for a while at least.

Quoted From: Art History Assignment: Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

Cuirassier: 1881

Dance at the Moulin Rouge: 1889-90

A recently discovered penciled inscription, in the artist's hand, on the back of this famous painting reads: "The instruction of the new ones by Valentine the Boneless." Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec was thus not depicting an ordinary evening at the Moulin Rouge, the fashionable Parisian nightclub but rather a specific moment when a man now known only by his nickname (which certainly describes his nimbleness as a dancer) appears to be teaching the "can-can." Many of the inhabitants of the scene are well-known members of Lautrec's demimonde of prostitutes and artists and people seen only at night including the white-bearded Irish poet William Butler Yeats who leans on the bar. One of the mysteries, however, is the dominant woman in the foreground, the beauty of her profile made all the more so in comparison with that of her chinless companion. It is the latter who expresses better than nearly any other character in this full stage of people Lautrec's profoundly touching ability to be brutally truthful but also truly kind in his observations. Joseph J. Rishel, from Philadelphia Museum of Art: Handbook of the Collections (1995), p. 206.

From: Philadelphia Museum of Art - At the Moulin Rouge: The Dance

Dancing at the Moulin Rouge: 1897

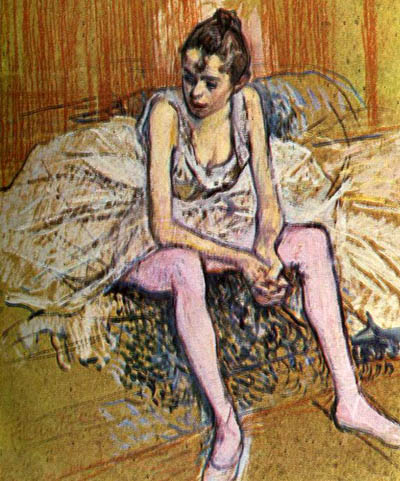

Dancer Adjusting Her Tights: 1890

Seated Dancer: 1890

Standing Dancer: 1890

_1890.jpg)

Desire Dihau

(Reading a Newspaper in the Garden): 1890

Driving the Mail Couch at Nice: 1881

Dun, a Gordon Setter Belonging to

Comte Alphonse de Toulouse-Lautrec: 1881

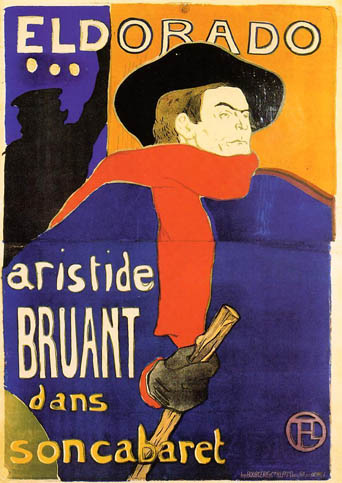

Eldorado, Aristide Bruant: 1892

This poster designed by Henri Toulouse-Lautrec is a copy of an earlier poster entitled Ambassadeurs that he designed for the singer Aristide Bruant. Toulouse-Lautrec created four posters for Bruant in 1892. This one advertises Bruant's café-cabaret at the Eldorado on Boulevard de Strasbourg in Paris. Aristide Bruant was a satirical singer who is shown here as a powerful, almost menacing figure. The poster owes its impact to the simplicity of the outlines and the palette, which comprises solid blocks of five colors. During the 1890's Toulouse-Lautrec visited the cabarets of Montmartre in Paris, producing a series of images depicting its nocturnal population.

From: Poster - Eldorado Aristide Bruant dans son Cabaret - Victoria and Albert Museum

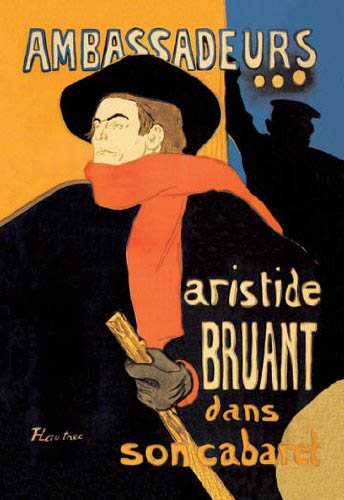

Eldorado, Aristide Bruant: 1892

This poster advertises an event with the singer Aristide Bruant at the Ambassadeurs nightclub in Paris, 1892. Bruant, a satirical singer and a friend of the French artist Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901), insisted that Lautrec design this poster. The director of the Ambassadeurs disliked its dramatic and uncompromising style, but since Bruant said he would not perform unless the poster remained, it was used both outside the theatre and inside to decorate the proscenium arch.

From: Poster - Ambassadeurs. Aristide Bruant Dans Son Cabaret - Victoria & Albert Museum

Eldorado, Aristide Bruant: 1893

Born Louis Armand Aristide Bruant in the village of Courtenay, Loiret in France, Bruant left his home in 1866 at age fifteen, following his father's death, to find employment. Making his way to the Montmartre Quarter of Paris, he hung out in the working-class bistros, where he finally was given an opportunity to show his musical talents. Although bourgeois by birth, he soon adopted the earthy language of his haunts, turning it into songs that told of the struggles of the poor.

Bruant began performing at cafe-concerts and developed a singing and comedy act that led to his being signed to appear at the Le Chat Noir club. Dressed in a red shirt, black velvet jacket, high boots, and a long red scarf, and using the stage name Aristide Bruant, he soon became a star of Montmartre, and when Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec began showing up at the cabarets and clubs, Bruant became one of the artist's first friends.

In 1885, Bruant opened his own Montmartre club, a place he called "Le Mirliton". Although he hired other acts, Bruant put on a singing performance of his own. As the master of ceremonies for the various acts, he used the comedy of the insult to poke fun at the club's upper-crust guests who were out "slumming" in Montmartre. His vaudeville-inspired mix of song, satire and entertainment developed into the musical genre called chanson réaliste (realist song).

Bruant died in Paris and was buried in the cimetière de Subligny, near his birthplace in the département of Loiret. A street in Paris was named in his honor.

From: Aristide Bruant - Wikipedia

Those Women

Elles: 1896

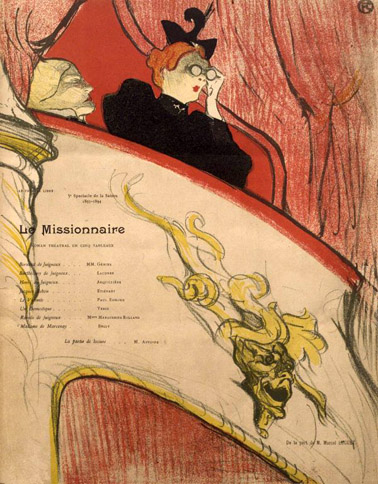

This poster advertised the exhibition and sale of a suite of eleven lithographs by Toulouse-Lautrec. The same image served as the frontispiece to the suite and as its cover.

The title "Elles" is the French feminine form of "they" and described the contents of the suite, which dealt sympathetically and matter-of-factly with the daily life of Parisian prostitutes with whom Toulouse-Lautrec had shared lodgings. The understated treatment may have disappointed the publisher, Gustave Pellet, who specialized in erotica.

From: Frontispiece for "Elles" - Indianapolis Museum of Art

Elles-Cha-U-Kao, Chinese Clown, Seated: 1896

This color lithograph belongs to the very important series Elles. The subject is Mlle Cha-U-Kao, a dancer, acrobat and clown who worked at the Moulin Rouge, the New Circus and in Parisian cabaret. She was one of the artist's favorite models and he depicted her several times.