Sebastiano Ricci

Italian Artist

1659 - 1734

Self Portrait: 1704-06

Sebastiano Ricci was an Italian painter of the late Baroque School of Venice. About the same age as Piazzetta, and an elder contemporary of Tiepolo, he represents a late version of the vigorous and luminous Cortonesque Style of grand manner fresco painting.

Early Years

He was born in Belluno, son of Andreana and Livio Ricci. In 1671, he apprenticed to Federico Cerebri of Venice. Others claim Ricci's first master was Sebastiano Mazzoni. In 1678, a youthful indiscretion led to an unwanted pregnancy, and ultimately to a greater scandal, when Ricci was accused of attempting to poison the young pregnant woman to avoid marriage. Imprisoned, he gained release only after intervention of a nobleman, probably a Pisani family member. He married the pregnant mother in 1691, although this was a stormy union.

After his arrest, he moved to Bologna, where he domiciled near the Parish of San Michele del Mercato. His painting style there was apparently influenced by Giovanni Gioseffo dal Sole. On September 28, 1682 he was contracted by the "Fraternity of Saint John of Florence" to paint a Decapitation of John the Baptist for their Oratory. On December 9, 1685, the Count of San Segundo near Parma commissioned from Ricci the decoration of the Oratory of the Madonna of the Seraglio, which he completed in collaboration of Ferdinando Galli-Bibiena by October 1687, receiving a compensation of 4,482 Lira. In 1686, the Duke Ranuccio II Farnese of Parma commissioned a Pietà for a new Capuchin convent. From 1687-1688, the apartments of the Parmense Duchess in Piacenza were decorated by Ricci with canvases recalling the life of the Farnese pope: Paul III.

Ricci in Turin, then Return to Venice

Apparently in 1688, Ricci abandoned his wife and daughter, and fled from Bologna to Turin with Magdalen, the daughter of the painter Giovanni Francesco Peruzzini. He was again imprisoned, and nearly executed, but ultimately was freed by the intercession of the Duke of Parma. The Duke employed him and assigned him a monthly salary of 25 crowns and lodging in the Farnese Palace in Rome. In 1692, he was commissioned to copy the Coronation of Charlemagne by Raphael in Vatican City, on behalf of Louis XIV, a task he finished only by 1694. The death of the Duke Ranuccio in December, 1694, who was also his protector, forced Ricci to abandon Rome for Milan, where by November of 1695 he completed frescoes in the Ossuary Chapel of the Church of San Bernardino dei Morti. On 22 June 1697, the Count Giacomo Durini hired him to paint in the Cathedral of Monza.

Frescoes in the Ossuary Chapel of the Church of San Bernardino dei Morti

Ossario di San Bernardino agli ossi

Ossario di San Bernardino agli ossi # 2

Ossario di San Bernardino agli ossi # 3

Ossario di San Bernardino agli ossi # 4

Ossario di San Bernardino agli ossi # 5

Ossario di San Bernardino agli ossi # 6

Ossario di San Bernardino agli ossi # 7

Ossario di San Bernardino agli ossi # 8

Ossario di San Bernardino agli ossi # 9

Ossario di San Bernardino agli ossi # 10

Ossario di San Bernardino agli ossi # 11

Ossario di San Bernardino agli ossi # 12

In 1698, he returned to the Venetian republic for a decade. By August 24, 1700, he frescoed the chapel of the Santissimo Sacramento in the church of Santa Giustina of Padua. In 1701, the Venetian geographer Vincenzo Maria Coronelli commissioned a canvas of the Ascension that was inserted on the ceiling of sacristy of the Basilica of the Santi Apostoli in Rome. In 1702, he frescoed the ceiling of the Blue Hall in the Schönbrunn Palace, with the Allegory of the Princely Virtues and Love of Virtue, that illustrated the education and dedication of future Emperor Joseph I. In Vienna, Frederick August II, the elector Saxony, requested an Ascension canvas, in part to convince others of the sincerity of his conversion to Catholicism, which allowed him to become the King of Poland. In 1704 he executed in Venice a canvas of San Procolo (Saint Proculus) for the Dome of Bergamo and a Crucifixion for the Florentine church of S. Francisco de Macci.

Blue Hall in the Schonbrunn Palace

Saints Procolo, Fermo and Rustico: Date Unknown

Florentine Fresco Masterpieces

In the summer of 1706, he traveled to Florence, where he completed a work that is by many considered his masterpieces. During his Florentine stay he first completed a large fresco series on allegorical and mythological themes for the now-called Marucelli-Fenzi or Palazzo Fenzi (now housing departments of University of Florence). After this work, Ricci, along with the quadraturista Giuseppe Tonelli, was commissioned by the Grand Duke Ferdinando de' Medici to decorate rooms in the Pitti Palace, where his Venus takes Leave from Adonis contains heavenly depictions that are airier and brighter than prior Florentine fresco series. These works gained him fame and requests from foreign lands and showed the rising influence of Venetian painting into other regions of Italy. He was to influence the Florentine Rococo fresco painter Giovanni Domenico Ferretti.

Frescoes in the Palazzo Pitti in Florence: Venus and Adonis

In 1708 he returned to Venice, completing a Madonna with the Child for San Giorgio Maggiore. In 1711, now painting alongside his nephew, the also well known Marco Ricci, he painted two canvases: Esther to Assuero and Moses Saved from the Nile, for the Taverna Palace.

Madonna and Child with Saints: Date Unknown

Esther Before Ahasuenus: ca 1730-34

Moses Defending the Daughters of Jethro: 1720's

This is the companion-piece of the Bathsheba at the Bath, also in the Budapest museum. The authenticity of the two large-size biblical scenes is confirmed by drawings which have survived in Ricci's Venetian sketch-book. From their size and form it may be assumed that these pictures adorned the walls of a large room, and on the evidence of their style they were most likely painted in the 1720's. In the long and narrow field the artist built up his composition as a frieze; the figures are graceful and supple, their animation and vigor create a vivid rhythm, the grouping is loose but nevertheless powerful.

From: Moses Defending the Daughters of Jethro

Moses Drawing Water from the Rock: ca 1700

Travels to London and Paris

He ultimately accepted foreign patronage in London, when he was provided a £770 commission by Lord Burlington for eight canvases, to be completed by him and his nephew Marco Ricci, depicting mythological frolics: Cupid and Jove, Bacchus Meets Ariadne, Diana and Nymphs, Bacchus and Ariadne, Venus and Cupid, Diane and Endymion, and a Cupid and Flora.

Meeting of Bacchus

(Burlington House)

Royal Academy, Sebastiano Ricci, 1713

Ceiling painting on canvass, by Sebastiano Ricci, "Meeting of Bacchus and Ariadne" Burlington House. Originally positioned on the North wall, at the top of the staircase this scene depicts Bacchus, god of wine, seated on a golden chariot, surrounded by followers. His attention is drawn to the lonely figure of Ariadne, abandoned on the Island of Naxos by Theseus.

The Meeting of Bacchus and Ariadne: ca 1713

Bacchus and Ariadne: ca 1713

It was Ariadne, the daughter of King Minos of Crete, who helped Theseus, whom she loved, to escape from the labyrinth with the aid of a ball of string, but all she had in return was to be abandoned by him on the island of Naxos. Here Bacchus came to her rescue. Classical representations show Ariadne asleep when Bacchus arrives, as described by Philostratus. But according to Ovid she was at that moment lamenting her fate, and Renaissance and later artists generally depict her awake. Bacchus took her jeweled crown and flung it into the heavens where it became a constellation. Ariadne was readily consoled by him and they were married shortly afterwards.

Diana and Nymphs

Venus and Cupid

Diana and Endymion

Endymion was a beautiful youth who fed his flock on Mount Latmos. One calm, clear night Diana, the moon, looked down and saw him sleeping. The cold heart of the virgin goddess was warmed by his surpassing beauty, and she came down to him, kissed him, and watched over him while he slept.

Another story was that Jupiter bestowed on him the gift of perpetual youth united with perpetual sleep. Of one so gifted we can have but few adventures to record. Diana, it was said, took care that his fortunes should not suffer by his inactive life, for she made his flock increase, and guarded his sheep and lambs from the wild beasts.

The story of Endymion has a peculiar charm from the human meaning which it so thinly veils. We see in Endymion the young poet, his fancy and his heart seeking in vain for that which can satisfy them, finding his favorite hour in the quiet moonlight, and nursing there beneath the beams of the bright and silent witness the melancholy and the ardor which consumes him. The story suggests aspiring and poetic love, a life spent more in dreams than in reality, and an early and welcome death.-S. G. B.

The "Endymion" of Keats is a wild and fanciful poem, containing some exquisite poetry, as this, to the moon:

"…The sleeping kine

Couched in thy brightness dream of fields divine.

Innumerable mountains rise, and rise,

Ambitious for the hallowing of thine eyes,

And yet thy benediction passeth not

One obscure hiding-place, one little spot

Where pleasure may be sent; the nested wren

Has thy fair face within its tranquil ken;" etc., etc.

Dr. Young, in the "Night Thoughts," alludes to Endymion thus:

"…These thoughts, O night, are thine;

From thee they came like lovers' secret sighs,

While others slept. So Cynthia, poets feign,

In shadows veiled, soft, sliding from her sphere,

Her shepherd cheered, of her enamored less

Than I of thee."

Fletcher, in the "Faithful Shepherdess," tells:

"How the pale Phœbe, hunting in a grove,

First saw the boy Endymion, from whose eyes

She took eternal fire that never dies;

How she conveyed him softly in a sleep,

His temples bound with poppy, to the steep

Head of old Latmos, where she stoops each night,

Gilding the mountain with her brother's light,

To kiss her sweetest."

From: Diana and Endymion. Vols. I & II: Stories of Gods and Heroes. Bulfinch, Thomas. 1913 - Age of Fable

He also frescoed now lost works for Count of Portland and designed stained glass for the chapel of the Duke of Chandos at Cannons.

By the end of 1716, with his nephew, he left England for Paris, where he met Watteau and perhaps Fragonard, and submitted his Triumph of the Wisdom over Ignorance in order to gain admission to the Royal French Academy of Painting and Sculpture, which was granted on May 18, 1718. He returned to Venice in 1718 a wealthy man, and bought comfortable lodgings in the Old Procuratory of Saint Mark. That same year, the Riccis decorated the villa of Giovanni Francesco Bembo in Belvedere, near Belluno.

Allegory of France as Minerva is triumphing over Ignorance and Crowning the Virtue: 1717-18

Last Years

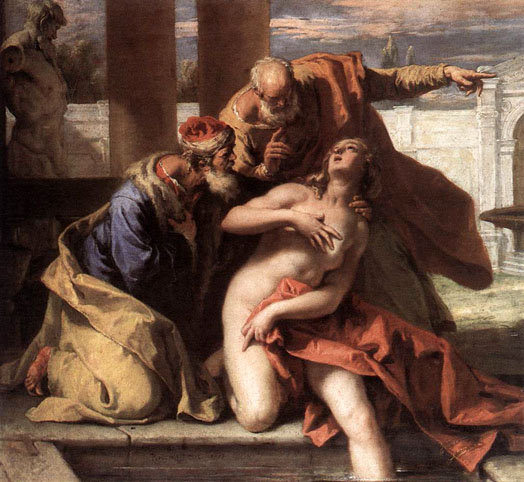

From 1724-29, Ricci worked intensely for the Royal House of Savoy in Turin: In 1724 he paints the Rejection of Agar and the Silenus Adores the Idols, in the 1725, Madonna in Gloria, in 1726, he completed in Turin the Susanna Presented to Daniel and Moses causes water to gush from the rock; He was admitted in October 1727 to the Clementine Academy of Venice.

Sacrifice to Silenus: ca 1723

In Greek mythology Silenus was a rural god, one of the retinue of Bacchus, a gay, fat old drunkard who was yet wise and had the gift of prophecy. On Ricci's picture the priest, touching the bust of Silenus, is blessing the kneeling people around him.

Maria Gloria with the Archangel Gabriel

Susanne before Daniel: Date Unknown

Ricci's style developed a following among other Venetian artists, influencing Francesco Polazzo, Gaspare Diziani, Francesco Migliori, Gaetano Zompini, and Francesco Fontebasso (1709-1769). Sebastiano Ricci died in Venice on 15 May 1734. This was an incredibly unfortunate event to both the public and his family. He was certainly a magnificent artist whom had inspired the lives of many.

Critical Assessments (Interpretations - Not Necessarily My Own)

"Ricci, leaning at first on the example of splendid art of the Veronese, made a new ideal prevail, one of clear and rich coloristic beauty: in this he paved the way for Tiepolo. The painting of figures of the Roccoco to Venice remains incomprehensible in its evolution without Ricci... Tiepolo germinated the work started by Ricci to such a richness and splendor that it leaves Ricci in the shadows... although Sebastiano is recognized in the combative role of forerunner" (Derschau).

"He is the master of a resurrected-fifteenth century style, whose painterly features are enriched with nervous express and, typically 17th century" (Rudolf Wittkower).

Wittkower in his Anthology, contrasts the facile luminous style of Ricci with the darker, more emotional intense painting of Piazzetta. Like Tiepolo, Ricci was an international artist; Piazzetta was local.

"We perceive in him that synthesis of the baroque decorativeness and individualized and substantial painting, that we will see later again in Tiepolo. On one side the influence of Cortona, directed and indirect, and on the other the observant painting of the hermit Magnasco; more intense, substantial and freed academic impulses, the airy, shining influences become, to the open air, magical coves, as well as gloomy corners. A new synthesis that opened wide new painting horizons, even if the scene is not that of a ballet, it is felt like binge in the wonders of the color, in more vibrating, acute, agile accents" (Moschini).

"At the start of the Baroque..Venetians remained isolated from the outside…from the great ideas of the baroque painting… The Ricci are the first traveling Venetian painters... and succeed to inaugurate the so-called Roccoco rooms of Pitti and Marucelli palaces." (Roberto Longhi).

Ricci "brought back in the Venetian tradition a wealth of chromatic expression resolved in a new vibrating brilliance brightness…by means of the intelligent interpretation of the Veronese chromatics and of the brushstrokes of a Magnasco-like touch, from the 16th century impediments, he takes unfashionable positions against "tenebrous styles", is against the new Piazzetta - Federico Bencovich. He supplied a valid painterly idiom for ... Tiepolo to use after his defection from the Piazzettism" (Pallucchini).

"Venice, still more than Naples, collects the Ricci inheritance of the prodigioso trade of Luca Giordano... Sebastiano throws again it, widens he then, refines it for the school of Sebastiano Mazzoni" (Argan)

From: Sebastiano Ricci - Wikipedia

Selected Works of Sebastiano Ricci

Abraham and Angels: ca 1695

In the Old Testament we read of the meeting between Abraham, the first of the great Hebrew patriarchs, and the three angels who symbolized the Holy Trinity , but until the 17th century the subject was rarely treated in Italian art. After the Reformation, the range of themes available to artists broadened considerably.

According to the Holy Scripture, Abraham was sitting at the tent door in the heat of the day when three men appeared before him. He welcomed them and with the traditional hospitality of the nomad brought them food, not knowing that they were angels. Over the meal one of the visitors predicted that Abraham's childless and ageing wife Sarah would bring him a son.

Ricci shows the final moment in the story when the angels reveal themselves to Abraham and predict his future. In fright and reverence the old man falls to his knees. Energetic gestures, large flowing folds of drapery and impressive light contrasts are combined within a balanced, strict composition.

From: Abraham and the Angels - Sebastiano Ricci

Adoration of the Shepherds: 1734

Allegorical Tomb of the Duke of Devonshire: Date Unknown

This elaborate imaginary tomb of the Duke of Devonshire (1640-1707) was one of a series. It was commissioned by Owen McSwiney to celebrate the political triumph of the Whig party following the Glorious Revolution of 1688. The monument, intact amongst the ruins of the past, is visited by figures who discuss the Duke's character and achievements, many weeping at his loss. This exercise in political flattery was produced for the Duke of Richmond, a prominent supporter of William of Orange.

The Venetian artist Sebastiano Ricci painted the figures, tomb and statues, and his nephew Marco executed the landscape.

From: The Barber Institute of Fine Arts, the Lapworth Museum of Geology and the University of Birmingham

Allegory of Heavenly Virtue: 1702-03

Allegory of Tuscany: 1706

Altar of Saint Gregory the Great

Ricci was an exuberant personality, internationally renowned and an archetypal "traveling" painter. After training in the Veneto, Ricci spent some time in Emilia (Bologna, Parma and Piacenza). This proved crucial to his development as his style was influenced by the local classicism, deepened when Ricci made a trip to Rome, where Annibale Carraci's frescos in Palazzo Farnese deeply moved him. After a brief trip to Vienna, Ricci went back to Venice in 1708, where his art changed. His Altarpiece of Saint Gregory the Great was a deliberate homage to Paolo Veronese and inaugurated a totally new era in eighteenth-century Venetian painting, trying to revive the glories of its Renaissance. Compared to his earlier works, his art was now remarkably free in composition and brushwork. This new style of painting was an immediate success. By 1711 Sebastiano had joined his nephew Marco Ricci in London where he remained for five years, working for many great noblemen.

From: Altar of St Gregory the Great

Angels Sculpturing the Statue of Madonna: 1700-05

Apelles Making a Portrait of Pancaspe: ca 1700-04

Apotheosis of a Saint: 1694-95

Apotheosis of Saint Sebastian: 1694-95

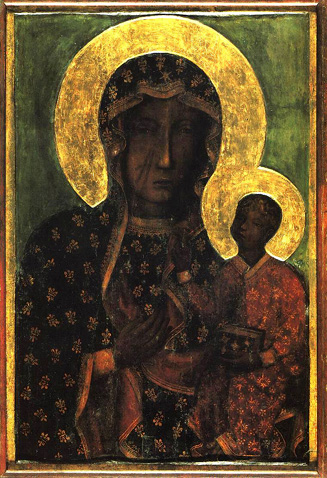

Appearance of Madonna with Child to Saint Bruno and Saint Hugo: 1704-06

Assumption: 1708-12

Bacchanal in Honor of Pan: ca 1716

This is an elegant painting of almost neoclassical taste that transforms the savage scene of the bacchanal into gracious cameos, as can be seen in the bleeding lamb's head held up by a charming ribbon by the putto on the right.

From: Bacchanal in Honor of Pan

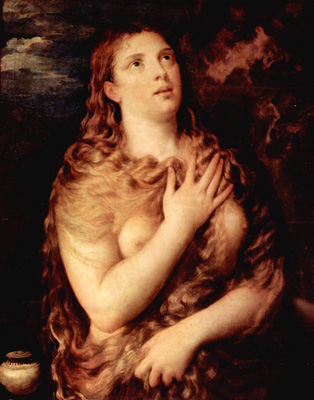

Bacchante: ca 1710

In Greek mythology, maenads were the female followers of Dionysus (Bacchus in the Roman pantheon), the most significant members of the Thiasus, the god's retinue. Their name literally translates as "raving ones". Often the maenads were portrayed as inspired by him into a state of ecstatic frenzy, through a combination of dancing and drunken intoxication. In this state, they would lose all self-control, begin shouting excitedly, engage in uncontrolled sexual behavior, and ritualistically hunt down and tear to pieces animals - and, in myth at least, sometimes men and children - devouring the raw flesh. During these rites, the maenads would dress in fawn skins and carry a thyrsus, a long stick wrapped in ivy or vine leaves and tipped by a cluster of leaves; they would weave ivy-wreaths around their heads, and often handle or wear snakes.

German philologist Walter Friedrich Otto writes that:

The Bacchae of Euripides gives us the most vital picture of the wonderful circumstance in which, as Plato says in the Ion, the god-intoxicated celebrants draw milk and honey from the streams. They strike rocks with the thyrsus, and water gushes forth. They lower the thyrsus to the earth, and a spring of wine bubbles up. If they want milk, they scratch up the ground with their fingers and draw up the milky fluid. Honey trickles down from the thyrsus made of the wood of the ivy, they gird themselves with snakes and give suck to fawns and wolf cubs as if they were infants at the breast. Fire does not burn them. No weapon of iron can wound them, and the snakes harmlessly lick up the sweat from their heated cheeks. Fierce bulls fall to the ground, victims to numberless, tearing female hands, and sturdy trees are torn up by the roots with their combined efforts.

The maddened Hellenic women of real life were mythologized as the mad women who were nurses of Dionysus in Nysa: Lycurgus "chased the Nurses of the frenzied Dionysus through the holy hills of Nysa, and the sacred implements dropped to the ground from the hands of one and all, as the murderous Lycurgus struck them down with his ox-goad." They went into the mountains at night and practiced strange rites.

In Macedon, according to Plutarch's Life of Alexander, they were called Mimallones and Klodones, epithets derived from the feminine art of spinning wool; nevertheless, these warlike parthenoi ("virgins") from the hills, associated with a shamanic Dionysios pseudanor, routed an invading enemy. In southern Greece they were described as Bacchae, Bassarides, Thyiades, Potniades and given other epithets.

The maenads were also known as Bassarids (or Bacchae or Bacchantes) in Roman mythology, after the penchant of the equivalent Roman god, Bacchus, to wear a fox-skin, a bassaris.

In Euripides' play The Bacchae, Theban maenads murdered King Pentheus after he banned the worship of Dionysus. Dionysus, Pentheus' cousin, himself lured Pentheus to the woods, where the maenads tore him apart. His corpse was mutilated by his own mother, Agave, who tore off his head, believing it to be that of a lion.

A group of maenads also killed Orpheus.

In Greek vase painting, the frolicking of maenads and Dionysus is often a theme depicted on Greek kraters, used to mix water and wine. These scenes show the maenads in their frenzy running in the forests, often tearing to pieces any animal they happen to come across.

Bacchus and Ceres

Baptism of Christ: ca 1733

Around 1713-14 Sebastiano Ricci decorated the chapel at Bulstrode House near Gerrards Cross for Henry Bentinck (1682-1726), 2nd Earl, and from 1715, 1st Duke of Portland. The painter Sir James Thornhill recorded on August 24, 1717, that Ricci had been paid £600 for "the little chapel at Bulstrode". Ricci painted the walls and ceiling of the chapel but after the destruction of the building, between 1847 and 1860, all that remains of the scheme are the modelli recording the composition of the paintings, and the description by George Vertue of 1733: "at the Duke of Portlands Gerrards Cross. (Bulstrode house) the Chappel. painted by Sig. Bastian Ricci. the round in the Ceiling. the Ascention of Christ at the end over the Gallery the Salutation. on the right hand side from the altar. the Baptism of Christ in the River Jordan - on the left, oppossite to it, the last Supper, with the twelve apostles. ornaments & the four Evangelists &c. the whole, a Noble free invention. great force of lights and shade. with variety & freedom. in the composition of the parts".

The scene is set in a wide open landscape, along the banks of the river Jordan, where the multitudes have come to be baptized by John. While people discard their clothes along the river in a theatrical fashion, Christ is at the center of the painting, surrounded by a glory of angels. The dove of the Holy Ghost descends from the sky, suddenly illuminated by a burst of divine light. The white drapery and the wings of the angels are moved by a miraculous wind that crosses the valley of the Jordan.

The main composition is framed by an architectural setting surmounted by the inscription: "HIC EST FILLIVS / MEVS DILECTV(S) / LVC CAPVT III" (Luke 3:21-22; in fact the precise source is Matthew 3:16-17). To the sides are the two allegorical figures of Meekness (not Saint Agnes as proposed by Daniels in 1976) on the left, and Penitence on the right. Above are two scenes in grisaille probably representing the Preaching of the Baptist on the left and his Beheading on the right. In the Washington modello for the Last Supper there are the figures of Divine Inspiration on the left and Obedience on the right, while the scenes above represent the Agony in the Garden and the Kiss of Judas.

From: The Baptism of Christ by Sebastiano Ricci - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

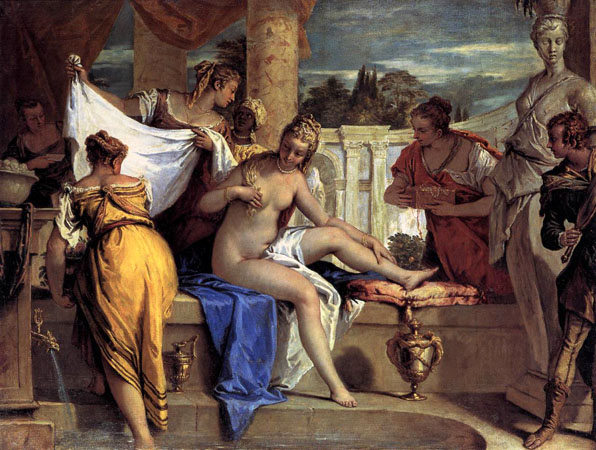

Bathsheba at the Bath: 1720's

The composition of this painting is similar to that of another painting of the same subject by Sebastiano Ricci, now in the Staatliche Museeen, Berlin. Both painting follow the scheme used for representing the toilette of Venus. Bathsheba is identified only by the barely visible spying figure in the Budapest painting and by the figure of a maid approaching with a letter from King David.

Apparently Ricci liked to use buildings with columns to close up the background, no doubt inspired by Veronese. Slender columns, light, almost floating balconies provide a picturesquely decorative framework for the figures grouped on the stage in front. The whole scene is pervaded by a shimmering silvery light; shadow and dimness have vanished completely; the painter applies light and colour for modeling. The coloring, with its nacreous luster, is particularly attractive; the hues are delicately shaded, enhancing the interplay of form and content.

From: Bathsheba at the Bath

Bathsheba: ca 1725

Attended by four maids and on the far right, a boy with a mirror, Uriah's beautiful wife, Bathsheba, devotes herself to her elaborate toilette in an enclosed garden. The sight of Bathsheba inflamed King David's desire, and he is usually depicted in a palace-window in the background. Here, however, a maid approaches on the far left with a letter from the king.

The painting dates from about 1725 and thus belongs to the artist's late period: its refinement of form and colour is reminiscent of the golden age of Venetian painting in the 16th century, in particular of Veronese. One of the most influential painters of his time, Ricci was well on the road to international success by the turn of the 17th century. His career took him to Parma, Bologna, Rome, Milan, Florence, Venice and London. His style bridges the impetuous baroque paintings of Luca Giordano and the Rococo-like, Venetian elegance of Tiepolo.From: Bathsheba

The Rape of the Sabine Women: ca 1700

The Rape of the Sabine Women and its companion-piece the Battle of the Romans and the Sabines illustrates the legend of Rome's foundation.

Romulus, the founder of Rome, succeeded by a ruse in ensuring the future growth of the population. He arranged a festival to which were invited the inhabitants of neighboring settlements including the Sabines, with their wives and children. During the festivities, at a given signal, the young men of Rome broke into the crowd and, choosing only unmarried maidens of the Sabines, carried them off. The Sabine women accepted their lot. But later a Sabine army attacked the city in force and succeeded in overcoming part of it. They were prevented from going further by the intervention of the Sabine women which brought about peace between the warring soldiers.

The story of the rape is told through five couples, arranged symmetrically. They show the same motif from various viewpoints. The central couple is modeled on Bernini's marble group The Rape of Proserpina.

From: The Rape of the Sabine Women

_ca_1700.jpg)

The Rape of the Sabine Women (Detail): ca 1700

The central couple in the painting is modeled on Bernini's marble group The Rape of Proserpina.

The Rape of Proserpina by Bernini: 1621-22

The large marble group of Pluto and Proserpina shows Pluto, powerful god of the underworld, abducting Proserpina, daughter of Ceres (Greek Demeter), the goddess of harvest and fertility. By interceding with Jupiter, her mother obtains permission for her daughter to return to earth for half the year and then spend the other half in Hades. Thus every spring the earth welcomes her with a carpet of flowers.

The group was executed between 1621 and 1622. Cardinal Scipione gave it to Cardinal Ludovisi in 1622, and it remained in his villa until 1908, when it was purchased by the Italian state and returned to the Borghese Collection.

In this group Bernini develops the twisting pose reminiscent of Mannerism, combined with an impression of vital energy (in pushing against Pluto's face Proserpina's hand creases his skin and his fingers sink into the flesh of his victim). Seen from the left, the group shows Pluto taking a fast and powerful stride and grasping Proserpina, from the front he appears triumphantly bearing his trophy in his arms; from the right one sees Proserpina's tears as she prays to heaven, the wind blowing her hair, as the guardian of Hades, the three-headed dog, barks. Various moments of the story are thus summed up in a single sculpture.

This group has often been said to strongly resemble ancient sculpture such as the Niobe (then in the Villa Medici), as regards Proserpina's face, while Pluto's stance is reminiscent of the Pedagogue (now in the Uffizi) and also the Hercules Killing Hydra, which was found in 1620 and restored by Algardi (now in the Capitoline Museums). Bernini, like Rubens, focused on the tactile quality of his surfaces.

From: The Rape of Proserpina

Battle of the Romans and the Sabines: ca 1700

Sebastiano Ricci's "Battle of the Romans and the Sabines" continues the legend of Rome's foundation. Three years after the Rape of the Sabines, their fathers and brothers attempt to avenge the injustice. Battle is engaged before the gates of Rome, but the women do not simply stand and watch. Not prepared to lose their next of kin from whatever side in a self-righteous bloodbath, they throw themselves into the battle to separate the combatants. The dynamism that events confer on these figures is not just a characteristic of Baroque painting, but of sculpture, too. Ricci's paintings can thus be readily compared with contemporary sculptures such as Diana and Callisto by Massimiliano Soldani Benzi. Their graceful gestures appear choreographed, their bodies captured in mid-movement. Both artists express this fleeting quality through erratic poses created by markedly shifting the figures' centers of gravity outwards. The fluttering garments take up the movement and further reinforce it. Ricci's painting also derives part of its inner tension from the contrast between the men's raw violence and the women's idealized, vulnerable beauty despite their fear and terror.

From: LIECHTENSTEIN MUSEUM Wien

Camillus Rescuing Rome from Brennus: ca 1716-20

Brennus was a chieftain of the Senones, a Gallic tribe originating from the modern areas of France known as Seine-et-Marne, Loiret, and Yonne, but which had expanded to occupy northern Italy.

More important historically was a branch of the above (called Senones, by Polybius), who about 400 B.C. made their way over the Alps and, having driven out the Umbrians, settled on the east coast of Italy from Ariminum to Ancona, in the so-called ager Gallicus, and founded the town of Sena Gallica (Sinigaglia), which became their capital.

In 391 they invaded Etruria and besieged Clusium. The Clusines appealed to Rome, whose intervention, accompanied by a violation of the law of nations, led to war, the defeat of the Romans at the Allia (18 July 390) and the capture of Rome. In 387 BC he led an army of Cisalpine Gauls in their attack on Rome. It has been theorized that Brennus is actually a title rather than a name. This is because "Brennus" also appears as the name of a Gallic leader 100 years later. It is also possible that Brennus refers to a god, his name taken by the leader before battle in order to invoke the god's favor and powers.

In the Battle of the Allia, Brennus defeated the Romans, and entered the city itself. The Senones captured the entire city of Rome except for the Capitoline Hill, which was successfully held against them. However, seeing their city devastated, the Romans attempted to buy their salvation from Brennus. The Romans agreed to pay one thousand pounds weight of gold. According to Livy, during a dispute over the weights used to measure the gold (the Gauls had brought their own, heavier-than-standard) Brennus threw his sword onto the scales and uttered the famous words "Vae victis!", which translates to "Woe to the vanquished!".

The argument about the weights had so delayed matters that the exiled dictator Marcus Furius Camillus had extra time to muster an army, return to Rome and expel the Gauls, saving both the city and the treasury. Following initial combat through Rome's streets, the Gauls were first ejected from the city, then utterly annihilated in a regular engagement eight miles outside of town on the road to Gabbi. Camillus was hailed by his troops as another Romulus, father of his country 'Pater Patriae' and second founder of Rome.

Some historical accounts say that the Senones besieging the Capitoline Hill were afflicted with an illness and thus were in a weakened state when they took the ransom for Rome. This is plausible as dysentery and other sanitation issues have incapacitated and killed large numbers of combat soldiers up until and including modern times.

It has been theorized that Brennus was working in concert with Dionysius of Syracuse, who sought to control all of Sicily. Rome had strong allegiances with Messana, a small city state in north east Sicily, which Dionysius wanted to control. With Rome's army pinned down by Brennus' efforts Dionysius led a campaign which ultimately failed. Brennus may have been paid twice to sack Rome.

However, the more accepted history (usually citing Livy and Plutarch) finds that Senones marched to Rome to exact retribution for three Roman ambassadors breaking the law of nations (oath of neutrality) in hostilities outside of Clusium. According to this history, the Senones marched to Rome, ignoring the surrounding countryside; once there, they sacked the city for 7 months, and then withdrew. For more information, see the Battle of Allia.

A famous depiction is the academic painting Le Brenn et sa part de butin (1893) by Paul Jamin that shows Brennus viewing his share of spoils (predominantly naked captive women) after the looting of Rome.

Brennus and His Share of the Spoil: 1893

Childhood of Romulus and Remus: ca 1708

Plutarch presents Romulus and Remus' ancient descent from prince Aeneas, fugitive from Troy after its destruction by the Achaeans. Their maternal grandfather is his descendant Numitor, who inherits the kingship of Alba Longa. Numitor's brother Amulius inherits its treasury, including the gold brought by Aeneas from Troy. Amulius uses his control of the treasury to dethrone Numitor, but fears that Numitor's daughter, Rhea Silvia, will bear children who could overthrow him.

Amulius forces Rhea Silvia to perpetual virginity as a Vestal priestess, but she bears children anyway. In one variation of the story, Mars, god of war, seduces and impregnates her: in another, Amulius himself seduces her, and in yet another, Hercules.

The king sees his niece's pregnancy and confines her. She gives birth to twin boys of remarkable beauty; her uncle orders her death and theirs. One account holds that he has Rhea buried alive - the standard punishment for Vestal Virgins who violated their vow of celibacy - and orders the death of the twins by exposure; both means would avoid his direct blood-guilt. In another, he has Rhea and her twins thrown into the River Tiber.

In every version, a servant is charged with the deed of killing the twins, but cannot bring himself to harm them. He places them in a basket and leaves it on the banks of the Tiber. The river rises in flood and carries the twins downstream, unharmed.

The river deity Tiberinus makes the basket catch in the roots of a fig tree that grows in the Velabrum swamp at the base of the Palatine Hill. The twins are found and suckled by a she-wolf (Lupa) and fed by a woodpecker (Picus). A shepherd of Amulius named Faustulus discovers them and takes them to his hut, where he and his wife Acca Larentia raise them as their own children.

In another variant, Hercules impregnates Acca Larentia and marries her off to the shepherd Faustulus. She has twelve sons; when one of them dies, Romulus takes his place to found the priestly college of Arval brothers Fratres Arvales. Acca Larentia is therefore identified with the Arval goddess Dea Dia, who is served by the Arvals. In later Republican religious tradition, a Quirinal priest (flamen) impersonated Romulus (by then deified as Quirinus) to perform funerary rites for his foster mother (identified as Dia).

Another and probably late tradition has Acca Larentia as a sacred prostitute (one of many Roman slangs for prostitute was lupa (she-wolf).

Yet another tradition relates that Romulus and Remus are nursed by the Wolf-Goddess Lupa or Luperca in her cave-lair (Lupercal). Luperca was given cult for her protection of sheep from wolves and her spouse was the Wolf-and-Shepherd-God Lupercus, who brought fertility to the flocks. She has been identified with Acca Larentia.

From: Romulus and Remus - Wikipedia

Christ and the Woman Taken in Adultery

Christ Healing the Blind Man

Christ who described himself as 'the light of the world' is depicted restoring the sight of a man blind since birth, as recounted in Saint John's Gospel. The crowd witnessing this miracle includes a mother and child, a soldier and a crippled man, in addition to Christ's Apostles and some skeptical Pharisees. The painting's small size did not inhibit Ricci's grand design. His balanced, richly colored composition features monumental architecture and lively detail. The picture was owned by King George II's physician, Dr Richard Mead, and may have been painted as a gift, perhaps from a grateful patient.

From: National Galleries of Scotland

Classical Ruins and Figures: ca 1725

In this fantastic vista, Marco Ricci combined ancient Roman monuments, such as an obelisk, sections of temples, and statues, to create a scene both picturesque and evocative of the power of the ancient world. In the last decade of his life, Ricci specialized in such theatrical views and repeatedly used the same monuments in different arrangements. As usual, his uncle Sebastiano Ricci painted the rustic figures, which are nearly lost amidst the colossal ruins.

From: Landscape with Classical Ruins and Figures - Getty Museum

Communion and Martyrdom of Saint Lucy: Date Unknown

David before the Army of Saul: ca 1684

Muzio Scevola: ca 1680-84

Dawn: 1702-04

Diana and Callisto: 1712-16

Inspired by Ovid's Metamorphoses, the subject - Diana discovering Callisto's pregnancy - gave Ricci the opportunity to linger gracefully and sensuously on the female nude.

Diana and Her Dog: ca 1700-05

Rather than being engaged in a heroic mythological story, this Diana, goddess of the moon, simply rests languidly in a world of her own. Lost in thought as her greyhound nuzzles her arm, she has dropped off her garment and seems spent from a long day of hunting.

Sebastiano Ricci characteristically employed this graceful, elongated figure type and lively brushwork, but the muted palette, modest dimensions, and reflective tone are unusual for him. Perhaps he restrained his normally bold colors here because he depicted Diana at dusk. This painting shows his transition to a more Rococo style of pastel colors and a lighter touch, leaving behind his earlier Baroque compositions with their dramatic gestures, bold colors, and serious subject matter.

From: Diana and Her Dog - Getty Museum

Diana and Nymphs

Dream of Aesculapius: ca 1710

After a long period of study of the greatest figures of late seventeenth century Italian painting, from Pietro da Cortona and Baciccio in Rome to the Carracci in Bologna, Luca Giordano in Florence and Magnasco in Milan, Sebastiano Ricci achieved a voice of his own characterized by a sparklingly fluent Rococo brilliance which was to gain the artist acceptance in London (1712-1716), and Paris (1716). Especially in paintings of small dimensions Sebastiano Ricci freed himself from all trace of his complex artistic training. Thus in the Dream of Aesculapius every detail of the bed chamber is rendered in the dancing rhythm of his line and the free and easy pictorial style. In the subdued glow of the setting, the scene seems like an animated ballet, fixed for ever in the wonder of bright, spirited color.

From: Dream of Aesculapius

Ecstasy of Saint Therese: Date Unknown

Escape to Egypt

The flight into Egypt is a biblical event described in the Gospel of Matthew, in which Joseph fled to Egypt with his wife Mary and infant son Jesus after a visit by Magi because they learn that King Herod intends to kill the infants of that area. The episode is frequently shown in art, as the final episode of the Nativity of Jesus in art, and was a common component in cycles of the Life of the Virgin as well as the Life of Christ.

When the Magi come in search of Jesus, they go to Herod the Great in Jerusalem and ask where to find the newborn "King of the Jews". Herod becomes paranoid that the child will threaten his throne, and seeks to kill him. Herod initiates the Massacre of the Innocents in hopes of killing the child. But an angel appears to Joseph and warns Joseph to take Jesus and his mother into Egypt.

Egypt was a logical place to find refuge, as it was outside the dominions of King Herod, but both Egypt and Palestine were part of the Roman Empire, making travel between them easy and relatively safe.

From: Flight into Egypt - Wikipedia

Exaltation of the True Cross: 1733

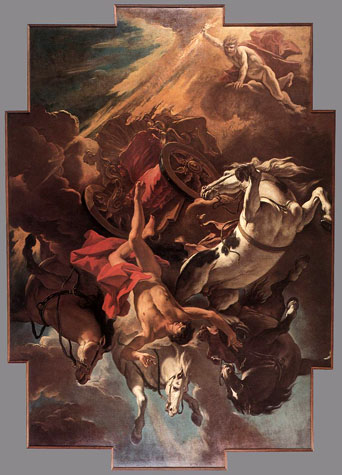

Fall of Phaethon: 1703-04

In Greek mythology Phaethon was the son of Helios, the sun-god. Helios drove his golden chariot, a 'quadriga' yoked to a team of four horses abreast, daily across the sky. Phaethon persuaded his unwilling father to allow him for one day to drive his chariot across the skies. Because he had no skill he was soon in trouble, and the climax came when he met the fearful Scorpion of the zodiac. He dropped the reins, the horses bolted and caused the earth itself to catch fire. In the nick of time Jupiter, father of the goods, put a stop to his escapade with a thunderbolt which wrecked the chariot and sent Phaethon hurtling down in flames into the River Eridanus (according to some, the Po). He was buried by nymphs. Phaethons' reckless attempt to drive his father's chariot made him the symbol of all who aspire to that which lies beyond their capabilities.

Undoubtedly Sebastiano Ricci's dashing virtuoso technique had its roots in the Baroque. In his hands, however, it was translated into an explosive, light-hearted energy

From: Fall of Phaethon

Family of Centaurs: Date Unknown

Feast in Honor of Pan: Date Unknown

Flora: 1712-16

In Roman mythology, Flora was a goddess of flowers and the season of spring. While she was otherwise a relatively minor figure in Roman mythology, being one among several fertility goddesses, her association with the spring gave her particular importance at the coming of springtime. Her festival, the Floralia, was held between April 28 and May 3 and symbolized the renewal of the cycle of life, drinking, and flowers. The festival was first instituted in 240 B.C.E but on the advice of the Sibylline Books she was given another temple in 238 B.C.E. Her Greek equivalent was Chloris, who was a nymph and not a goddess at all. Flora was married to Favonius, the wind god, and her companion was Hercules. Her name is derived from the Latin word "flos" which means "flower." In modern English, "Flora" also means the plants of a particular region or period.

Flora achieved more prominence in the neo-pagan revival of Antiquity among Renaissance humanists than she had ever enjoyed in ancient Rome.

From: Flora (Mythology) - Wikipedia

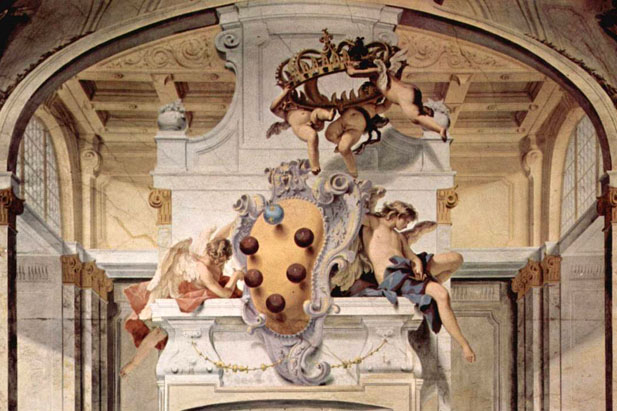

Frescoes in the Palazzo Pitti in Florence: Venus and Adonis

Frescoes in the Palazzo Pitti in Florence: Arms of the Medici

Frescoes in the Palazzo Pitti in Florence: Diana and chromemansion

Palazzo Pitti

The Palazzo Pitti in English sometimes called the Pitti Palace, is a vast mainly Renaissance palace in Florence, Italy. It is situated on the south side of the River Arno, a short distance from the Ponte Vecchio. The core of the present palazzo dates from 1458 and was originally the town residence of Luca Pitti, an ambitious Florentine banker.

The palace was bought by the Medici family in 1549 and became the chief residence of the ruling families of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany. It grew as a great treasure house as later generations amassed paintings, plates, jewelry and luxurious possessions. In the late 18th century, the palazzo was used as a power base by Napoleon, and later served for a brief period as the principal royal palace of the newly united Italy. The palace and its contents were donated to the Italian people by King Victor Emmanuel III in 1919, and its doors were opened to the public as one of Florence's largest art galleries. Today, it houses several minor collections in addition to those of the Medici Family, and is fully open to the public. The construction of this severe and forbidding building was commissioned in 1458 by the Florentine banker Luca Pitti, a principal supporter and friend of Cosimo de' Medici. The early history of the Palazzo Pitti is a mixture of fact and myth. Pitti is alleged to have instructed that the windows be larger than the entrance of the Palazzo Medici. The 16th-century art historian Giorgio Vasari proposed that Brunelleschi was the palazzo's architect, and that his pupil Luca Fancelli was merely his assistant in the task but today it is Fancelli that is generally credited. Besides obvious differences from the elder architect's style, Brunelleschi died 12 years before construction of the palazzo began. The design and fenestration suggest that the unknown architect was more experienced in utilitarian domestic architecture than in the humanist rules defined by Alberti in his book De Re Aedificatoria. Though impressive, the original palazzo would have been no rival to the Florentine Medici residences in terms of either size or content. Whoever the architect of the Palazzo Pitti was, he was moving against the contemporary flow of fashion. The rusticated stonework gives the palazzo a severe and powerful atmosphere, reinforced by the three-times-repeated series of seven arch-headed apertures, reminiscent of a Roman aqueduct. The Roman-style architecture appealed to the Florentine love of the new style all'antica. This original design has withstood the test of time: the repetitive formula of the façade was continued during the subsequent additions to the palazzo, and its influence can be seen in numerous 16th-century imitations and 19th-century revivals. Work stopped after Pitti suffered financial losses following the death of Cosimo de' Medici in 1464. Luca Pitti died in 1472 with the building unfinished. The building was sold in 1549 by Buonaccorso Pitti, a descendant of Luca Pitti, to Eleonora di Toledo. Raised at the luxurious court of Naples, Eleonora was the wife of Cosimo I de' Medici of Tuscany, later the Grand Duke. On moving into the palace, Cosimo had Vasari enlarge the structure to fit his tastes; the palace was more than doubled by the addition of a new block along the rear. Vasari also built the Vasari Corridor, an above-ground walkway from Cosimo's old palace and the seat of government, the Palazzo Vecchio, through the Uffizi, above the Ponte Vecchio to the Palazzo Pitti. This enabled the Grand Duke and his family to move easily and safely from their official residence to the Palazzo Pitti. Initially the Palazzo Pitti was used mostly for lodging official guests and for occasional functions of the court, while the Medicis' principal residence remained the Palazzo Vecchio. It was not until the reign of Eleonora's son Ferdinando I and his wife Cristina of Lorraine that the palazzo was occupied on a permanent basis and became home to the Medicis' art collection. Land on the Boboli hill at the rear of the palazzo was acquired in order to create a large formal park and gardens, today known as the Boboli Gardens. The landscape architect employed for this was the Medici court artist Niccolo Tribolo, who died the following year; he was quickly succeeded by Bartolommeo Ammanati. The original design of the gardens centred on an amphitheatre, behind the corps de logis of the palazzo. The first play recorded as performed there was Andria by Terence in 1476. It was followed by many classically inspired plays of Florentine playwrights such as Giovan Battista Cini. Performed for the amusement of the cultivated Medici court, they featured elaborate sets designed by the court architect Baldassarre Lanci. With the garden project well in hand, Ammanati turned his attentions to creating a large courtyard immediately behind the principal façade, to link the palazzo to its new garden. This courtyard has heavy-banded channeled rustication that has been widely copied, notably for the Parisian Palais of Maria de' Medici, the Luxembourg. In the principal façade Ammanati also created the finestre inginocchiate ("kneeling" windows, in reference to their imagined resemblance to a prie-dieu, a device of Michelangelo's), replacing the entrance bays at each end. During the years 1558-70, Ammanati created a monumental staircase to lead with more pomp to the piano nobile, and he extended the wings on the garden front that embraced a courtyard excavated into the steeply sloping hillside at the same level as the piazza in front, from which it was visible through the central arch of the basement. On the garden side of the courtyard Amannati constructed a grotto, called the "Grotto of Moses" on account of the porphyry statue that inhabits it. On the terrace above it, level with the piano nobile windows, Amannati constructed a fountain centered on the axis; it was later replaced by the Fontana del Carciofo ("Fountain of the Artichoke"), designed by Giambologna's former assistant, Francesco Susini, and completed in 1641.

Grotto of Moses

In 1616, a competition was held to design extensions to the principal urban façade by three bays at either end. Giulio Parigi won the commission; work on the north side began in 1618, and on the south side in 1631 by Alfonso Parigi. During the 18th century, two perpendicular wings were constructed by the architect Giuseppe Ruggeri to enhance and stress the widening of via Romana, which creates a piazza centered on the façade, the prototype of the cour d'honneur that was copied in France. Sporadic lesser additions and alterations were made for many years thereafter under other rulers and architects.

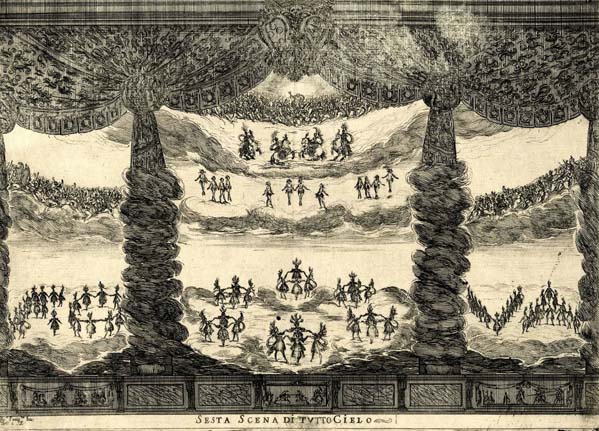

Field of View of Giulio Parigi

These set designs are by Alfonso Parigi for the opera Le Nozze degli Dei (The Marriage of the Gods). It was performed in 1637 in Florence at the Palazzo Pitti in the courtyard. The images are from the British Museum website.

Alfonso Parigi # 1

Alfonso Parigi # 2

Alfonso Parigi # 3

Alfonso Parigi # 4

To one side of the Gardens is the bizarre grotto designed by Bernardo Buontalenti. The lower façade was begun by Vasari but the architecture of the upper storey is subverted by 'dripping' pumice stalagtites with the Medici coat of arms at the center. The interior is similarly poised between architecture and nature; the first chamber has copies of Michelangelo's four unfinished slaves emerging from the corners which seem to carry the vault with an open oculus at its center and painted as a rustic bower with animals, figures and vegetation. Figures, animals and trees made of stucco and rough pumice adorn the lower walls. A short passage leads to a small second chamber and to a third which has a central fountain with Giambologna's Venus in the centre of the basin, peering fearfully over her shoulder at the four satyrs spitting jets of water at her from the edge.

I found this blog on three unfinished slaves including Saint Mathews.

Michelangelo's Unfinished Slaves

I started thinking through Michelangelo's unfinished sculptures of slaves. These unfinished pieces are incredible for what they reveal about Michelangelo's work process; it's like seeing a three-dimensional equivalent of a preliminary drawing where all of the evidence and mistakes are bare and exposed. Even in their incomplete state, the form quietly emerges out of the marble in a manner that is both mysterious and powerful. There are practically no details in these sculptures, yet they command a weight and sense of mass and movement that is beyond their actual physical weight. I started thinking through Michelangelo's unfinished sculptures of slaves. These unfinished pieces are incredible for what they reveal about Michelangelo's work process; it's like seeing a three-dimensional equivalent of a preliminary drawing where all of the evidence and mistakes are bare and exposed. Even in their incomplete state, the form quietly emerges out of the marble in a manner that is both mysterious and powerful. There are practically no details in these sculptures, yet they command a weight and sense of mass and movement that is beyond their actual physical weight. In relation to the sculptures I'll be working on, Michelangelo's unfinished slaves are an excellent example of the kind of the articulation I'm thinking about: form that slowly emerges and remains at times elusive and ambiguous. I want the sculptures to focus on an internal sense of structure, with a highly textured surface with devoid of highly articulated details. The form is at times undefined, inviting the viewer to want more.

Saint Matthew: Unfinshed

Bearded Slave: Unfinished

Young Slave: Unfinished

From: Michelangelo's Unfinished Slaves

The palazzo remained the principal Medici residence until the last male Medici heir died in 1737. It was then occupied briefly by his sister, the elderly Electress Palatine; on her death, the Medici dynasty became extinct and the palazzo passed to the new Grand Dukes of Tuscany, the Austrian House of Lorraine, in the person of Francis I, Holy Roman Emperor. The Austrian tenancy was briefly interrupted by Napoleon, who used the palazzo during his period of control over Italy.

When Tuscany passed from the House of Lorraine to the House of Savoy in 1860, the Palazzo Pitti was included. After the Risorgimento, when Florence was briefly the capital of the Kingdom of Italy, Victor Emmanuel II resided in the palazzo until 1871. His grandson, Victor Emmanuel III, presented the palazzo to the nation in 1919. The palazzo and other buildings in the Boboli Gardens were then divided into five separate art galleries and a museum, housing not only many of its original contents, but priceless artifacts from many other collections acquired by the state. The 140 rooms open to the public are part of an interior, which is in large part a later product than the original portion of the structure, mostly created in two phases, one in the 17th century and the other in the early 18th century. Some earlier interiors remain, and there are still later additions such as the Throne Room. In 2005 the surprise discovery of forgotten 18th-century bathrooms in the palazzo revealed remarkable examples of contemporary plumbing very similar in style to the bathrooms of the 21st century.From: Palazzo Pitti - Wikipedia

Hercules and Omphale: Date Unknown

Omphale

In Greek mythology, Omphale was a daughter of Iardanus, either a king of Lydia, or a river-god. Omphale was queen of the kingdom of Lydia in Asia Minor; according to Bibliotheke she was the wife of Tmolus, the oak-clad mountain king of Lydia; after he was gored to death by a bull, she continued to reign on her own.

Diodorus Siculus provides the first appearance of the Omphale theme in literature, though Aeschylus was aware of the episode. The Greeks did not recognize her as a goddess: the undisputed etymological connection with omphalos, the world-navel, has never been made clear. In her best-known myth, she is the master of the hero Heracles during a year of required servitude, a scenario that offered writers and artists opportunities to explore gender roles and erotic themes.

Hercules and Omphale by Johann Heinrich Tischbein the Elder

Gender Roles: The Dominant Woman and the Effeminate Man

Hercules and Omphale by Spranger

Omphale and Hercules by Theodor Van Thulden

In one of many Greek variations on the theme of penalty for "inadvertent" murder, for his murder of Iphitus, the great hero Heracles, whom the Romans identified as Hercules, was, by the command of the Delphic Oracle Xenoclea, remanded as a slave to Omphale for the period of a year, the compensation to be paid to Eurytus, who refused it. The theme, inherently a comic inversion of gender roles, was not illustrated in Classical Greece. Plutarch, in his Vita of Pericles, 24, mentions lost comedies of Kratinos and Eupolis, which alluded to the contemporary capacity of Aspasia in the household of Pericles and to Sophocles in The Trachiniae it was shameful for Heracles to serve an Oriental woman in this fashion, but there are many late Hellenistic and Roman references in texts and art to Heracles being forced to do women's work and even wear women's clothing and hold a basket of wool while Omphale and her maidens did their spinning, as Ovid tells: Omphale even wore the skin of the Nemean Lion and carried Heracles' olive-wood club. Unfortunately no full early account survives, to supplement the later vase-paintings.

After completing his Twelve Labors, Heracles joined the Argonauts in a search for the Golden Fleece. They rescued heroines, conquered Troy, and helped the gods fight against the Gigantes. He also fell in love with Princess Iole of Oechalia. King Eurytus of Oechalia promised his daughter, Iole, to whoever could beat his sons in an archery contest. Heracles won but Eurytus abandoned his promise. Heracles' advances were spurned by the king and his sons, except for one: Iole's brother Iphitus. Heracles killed the king and his sons-excluding Iphitus-and abducted Iole. Iphitus became Heracles' best friend. However, once again, Hera drove Heracles mad and he threw Iphitus over the city wall to his death. Once again, Heracles purified himself through three years of servitude - this time to Queen Omphale of Lydia.

From: Heracles - Wikipedia

But it was also during his stay in Lydia that Heracles captured the city of the Itones and enslaved them, killed Syleus who forced passersby to hoe his vineyard, and captured the Cercopes. He buried the body of Icarus and took part in the Calydonian Boar Hunt and the Argonautica.

After some time, Omphale freed Heracles and took him as her husband.

Eroticism Depicted in the Omphale and Hercules Myth

Hercules in the Palace of Omphale by Antonio Bellucci

Hercules and Omphale by Boucher

Hercules and Omphale by Francois Le Moyne

Omphale's name, connected with omphalos, a Greek word meaning navel (or axis), may represent a significant Lydian earth goddess. Heracles's servitude, a mystical marriage, thus may represent the servitude of the sun to the axis of the celestial sphere, the spinners being Lydian versions of the Moirae. Most earth goddess religions contained a priesthood which wore women's clothing, was effeminate, or involved eunuchs. The priest of Heracles, curiously, also wore female clothing, and this myth may represent an attempt to explain the fact.

From: Omphale - Wikipedia

Hercules at the Crossroad: ca 1706

The Greek hero was a popular subject, especially in the Baroque era and after, because his adventures allowed painters to display familiarity with anatomy and motion.

From: Hercules at the Crossroad

Hercules on the Crossroads: Date Unknown

Holy Family with the Infant Saint John the Baptist: ca 1710

Madonna and Child with Saints: 1708

This has to be one of the most cheerful altarpieces of the whole eighteenth century. It was directly inspired by Veronese's Sacra Conversazione but the subject is reinvented with a freshness and exquisite coloration that are spectacularly effective. It was commissioned for a side altar in the church designed by Palladio. It is carefully composed using rising diagonal lines that shift the viewer's attention toward the left of the picture, that is to say toward the Madonna and Child. This geometrical rigor (which is disguised by the apparent immediacy of an action-packed scene) also helps to overcome the tricky problem of having so many figures packed into a fairly small space.

From: Madonna and Child with Saints

Last Supper: 1713-14

Lucretia: 1680-84

The legend of Lucretia is reported by Livy in his Roman history. In his story, she was the daughter of Spurius Lucretius Tricipitinus, sister of Publius Lucretius Tricipitinus, niece of Lucius Junius Brutus, and wife of Lucius Tarquinius Collatinus who was the son of Egerius.

The story begins with a drinking bet between some young men at the home of Sextus Tarquinius, a son of the king of Rome. They decide to surprise their wives to see how they behave when they are not expecting their husbands. The wife of Collatinus, Lucretia, is behaving virtuously, while the wives of the king's sons are not.

Several days later, Sextus Tarquinius goes to Collatinus' home and is given hospitality. When everyone else is asleep in the house, he goes to Lucretia's bedroom and threatens her with a sword, demanding and begging that she submit to his advances. She shows herself to be unafraid of death, and then he threatens that he will kill her and place her nude body next to the nude body of a servant, bringing shame on her family as this will imply adultery with her social inferior.

She submits, but in the morning calls her father, husband, and uncle to her, and she tells them how she has "lost her honor" and demands that they avenge her rape. Though the men try to convince her that she bears no dishonor, she disagrees and kills herself, her "punishment" for losing her honor. Brutus, her uncle, declares that they will drive the king and all his family from Rome and never have a king in Rome again. When her body is publicly displayed, it reminds many others in Rome of acts of violence by the king's family.

Her rape is thus the trigger for the Roman revolution. Her uncle and husband are leaders of the revolution and the newly-established republic. Lucretia's brother and husband are the first Roman consuls.

The legend of Lucretia -- a woman who was sexually violated and therefore shamed her male kinsmen who then took revenge against the rapist and his family -- was used not only in the Roman republic to represent proper womanly virtue, but was used by many writers and artists in later times.

From: Lucretia

Madonna and Child with Saints: Date Unknown

Madonna with Child, Saint John the Baptist and Saint Peter: 1704-16

Maria Gloria with the Archangel Gabriel

Miracle of Saint Francis of Paola: 1733

Miraculous Arrival of the Statue of Madonna: 1700-05

Neptune and Amphitrite: 1691-94

Ricci travelled throughout his life, working in the major Italian cities as well as in England, France and the Netherlands, but always returning to Venice. This painting was executed during his Roman period.

From: Neptune and Amphitrite

Night: 1702-04

Noon: 1702-04

Nymph and Satyrs: 1712-16

Paul III Appointing His Son Pier Luigi to Duke of Piacenza and Parma: 1687

Born in Rome, Pier Luigi was the illegitimate son of Cardinal Alessandro Farnese (who later became Pope Paul III). He became a soldier and participated in the sack of Rome in 1527.

Pier Luigi Alexander Farnese was born in 1503 from the union between Cardinal Alexander Farnese (future Pope Paul III) and probably Silvia Ruffini - a Roman noblewoman who also gave birth with Alexander to three other children: Constanza, Paul and Ranuccio.

His illegitimacy tormented Pier Luigi all his life, and doubtless contributed to the formation of his character. The nobility of Piacenza was frequently known to insult him as "the bastard son of the Pope". As the eldest and beloved son he was legitimized along with his brother Paul at the age of two in 1505 by Pope Julius II. He was given a famous humanist tutor, Baldassarre Malosso di Casalmaggiore, nicknamed "Tranquillus"; and quickly developed a love of war and fortifications.

Alexander was, however, keen to make Pier Luigi the true head of the Farnese family and so arranged a favorable marriage alliance with Gerolama Orsini, daughter of Lodovico, Count of Pitigliano. In 1513 the engagement contract was drawn up, and in 1519 the wedding celebrated.

Despite a loveless marriage, Gerolama remained a faithful devoted wife, tolerating Pier Luigi's excesses, brutality, and extravagances with dignity. Delays in the construction at the palace in Gradoli, meant the young couple had to lodge in the Castle at Valentano. The following year their first son Alexander was born.

Pier Luigi quickly became the stereotype of a mercenary soldier - wild, primeval and amoral. He lacked neither courage nor daring, and was strong and audacious yet brutal enough to offend many commentators. Nor did he always fight on the traditional side of the papacy; reversing the pro-Guelph sentiments of the Farnese.

In 1520, at the age of seventeen, he and his brother Ranuccio were already employed as mercenaries in the pay of Venice. As a result he served under the standard of Charles V - remaining with the emperor until 1527 and present at the Sack of Rome; in which he himself took part.

While his brother Ranuccio withdrew to Castel Sant'Angelo to defend the Pope; Pier Luigi crossed the Tiber and quartered in the family palace, thus saving it from destruction. Critics accused the Farnese of backing both sides, but Pope Clement VII refused to condemn. Finally when the plague hit the city, the imperial troops decided to withdraw.

Pier Luigi retired to the Roman countryside, taxing it without mercy and permitting a climate of theft and murder. Pope Clement, tired of this behavior, eventually threatened excommunication, until Cardinal Alexander tried diplomatically to reconcile his son with the pope. In 1528 Pier Luigi, still under imperial pay, fought in Puglia against the French army and distinguished himself in the defense of Manfredonia.

When his father was elevated to the papacy as Paul III in 1534, great festivities were celebrated at Valentano, after which Pier Luigi left for Rome.

Paul's first action was to make Pier Luigi's eldest son, Alessandro Farnese, a cardinal. But Charles V only reluctantly allowed the granting of titles to Pier Luigi over the city of Novara - agreeing an annual pension on the condition that the news was not made public. In the hope of speeding things up, Pier Luigi took direct part in the negotiations while leading troops into the lands occupied by his Farnese relatives. Novara and its surrounding territory was finally established as a marquessate in favor of Pier Luigi, but had to wait until February 1538 until formal investiture could be made.

In the meantime the office of Captain General of the Church had become vacant, and Paul nominated his son on January 31, 1537. Pier Luigi travelled through the Papal States defeating pockets of resistance before arriving in triumph at Piacenza.

Meanwhile Paul III gradually recovered the family lands around Castro which had been split after the death of Ranuccio the Elder. To this he added the territory of Ronciglione. Pier Luigi, was invested with the titles of Montalto which gave the right to export grain without paying taxes; and Paul accepted feudal rights over Canine, Gradoli, Valentano, Latera and Marta. He exchanged the city of Frascati for the fortress at Castro, and at bought Bisenzio from the Diocese of Montefiascone. As a final act, Paul created a formal duchy out of the lands and bestowed it upon his son and heirs. The duchy was, however, to come under the direct control of the Holy See.

The Duchy of Castro operated as a functioning State within the Patrimony of Saint Peter. It possessed rich forests full of game, fertile vineyards and fields, and a great number of fortresses. In the consistory of 14 March 1537, the Pope also awarded his son the cities of Nepi and Ronciglione. Pier Luigi was tasked with repairing all the fortresses over which he was now feudal lord. The new Duke commissioned Antonio da Sangallo the Younger to create a new capital, which saw the construction of a citadel, ducal palace and mint.

In 1538 his son Ottavio married Margaret of Austria, daughter of Charles V; thus consolidating the friendship between the Farnese and the imperial family. In 1543 another son, Orazio, was sent to the court of the king of France. Finally in 1545 his third son, Ranuccio, was created a cardinal by Paul III.

Paul III then went on to make Pier Luigi Duke of Parma and Piacenza, properties that had previously been a part of the Papal States. Pier Luigi and his son, Ottavio, declared they would have pay 9,000 golden ducati every year to the Holy See, and, in exchange, they gave back the Duchies of Camerino and Nepi. Pier Luigi took possession of his new states on September 23, 1546.

During his life he had gained a fame on cruelty, ruthlessness and decadence. He was also suspected of being homosexual, with scandal erupting in 1537 when he was accused in what became known as the 'Rape of Fano' where he allegedly raped the young bishop of the city, Cosimo Gheri, while marching with his troops (Gheri subsequently died). Letters also exist from his father, Paul III, reproaching him for taking male lovers when on an official mission to the court of the emperor; and another from the chancellor of the Florentine embassy detailing a man-hunt he had mounted in Rome to search for a youth who had refused his advances. The allegations of homosexuality were used in later protestant polemic directed against the papacy.

His firm rule and his taxes gained him the enmities of the cities, which were used to the fair authority of the Popes. The aristocracy, in particular, was supported against him by emperor Charles V, who aimed to unite Parma and Piacenza to the Duchy of Milan.

In 1547 a conspiracy was arranged against him by counts Francesco Anguissola and Agostino Landi and the marquises Giovan Luigi Confalonieri and Girolamo and Alessandro Pallavicini. After Anguissola and others had stabbed him to death, the conspirators hung his body from a window of his palace in Piacenza. Charles V's vicar Ferrante Gonzaga captured the Duchy soon after; although subsequent events led to the return of the duchy to Pier-Luigi's son, Ottavio in 1551.

From: Pier Luigi Farnese, Duke of Parma - Wikipedia

Pope Paul III Proclaims: ca 1687-88"

Perseus Confronting Phineus with the Head of Medusa: ca 1705-10

In Greek mythology, the hero Perseus was famous for killing Medusa, the snake-haired Gorgon whose grotesque appearance turned men to stone. This painting, however, shows a later episode from the hero's life. At Perseus' and Andromeda's wedding, their nuptials were interrupted by a mob led by Phineus, a disappointed suitor. After a fierce battle, Perseus finally triumphed by brandishing the head of Medusa and turning his opponents into stone.

Sebastiano Ricci depicted the fight as a forceful, vigorous battle. In the center, Perseus lunges forward, his muscles taut as he shoves the head of Medusa at Phineus and his men. One man holds up a shield, trying to reflect the horrendous image and almost losing his balance. Behind him, soldiers already turned to stone are frozen in mid-attack. All around, other men have fallen and are dead or dying. Ricci used strong diagonals and active poses to suggest energetic movement.

From: Perseus Confronting Phineus with the Head of Medusa - Getty Museum

Pope Gregory the Great and Saint Vitalis Saving the Souls of Purgatory: 1730-34

Pope Gregory the Great before Virgin: 1699-1700

Pope Gregory the Great Saving the Souls of Purgatory: Date Unknown

Pope Gregory the Great Saving the Souls of Purgatory

History of Purgatory - Wikipedia

Internet History Sourcebooks

THE DIALOGUES OF SAINT GREGORY, SURNAMED DIALOGUS AND THE GREAT,

POPE OF ROME AND THE FIRST OF THAT NAME.

The Dialogues of Gregory the Great - Open Library

Pope Gregory I by Francisco de Zurbaran

Pope Gregory I

Pope Gregory I (Latin: Gregorius I) (ca. 540 - 604), better known in English as Gregory the Great, was pope from September 3, 590 until his death. Gregory is well known for his writings, which were more prolific than those of any of his predecessors as pope.

Throughout the Middle Ages he was known as "The Father of Christian Worship" because of his exceptional efforts in revising the Roman worship of his day.

He is also known as Saint Gregory the Dialogist in Eastern Orthodoxy because of his Dialogues. For this reason, English translations of Orthodox texts will sometimes list him as "Gregory Dialogus". He was the first of the popes to come from a monastic background. Gregory is a Doctor of the Church and one of the Latin Fathers. He is considered a Saint in the Roman Catholic Church, Eastern Orthodox Church, Anglican Communion, and some Lutheran Churches. Immediately after his death, Gregory was canonized by popular acclaim. John Calvin admired Gregory and declared in his Institutes that Gregory was the last good pope. He is the patron saint of musicians, singers, students, and teachers.

Early Life

The exact date of Gregory's birth is uncertain, but is usually estimated to be around the year 540, in the city of Rome. His parents named him Gregorius, which according to Aelfric in An Homily on the Birth-Day of Saint Gregory, "... is a Greek Name, which signifies in the Latin Tongue Vigilantius, that is in English, Watchful...." The medieval writers who give this etymology do not hesitate to apply it to the life of Gregory. Aelfric, for example, goes on: "He was very diligent in God's Commandments."

When Gregory was a child, Italy was retaken from the Goths by Justinian I, emperor of the Roman Empire ruling from Constantinople. The war was over by 552. An invasion of the Franks was defeated in 554. The Western Roman Empire had long since vanished in favor of the Gothic kings of Italy. After 554 there was peace in Italy and the appearance of restoration, except that the government now resided in Constantinople. Italy was still united into one country, "Rome" and still shared a common official language, the very last of classical Latin.

From 542 the so-called Plague of Justinian swept through the provinces of the empire, including Italy. The plague caused famine, panic, and sometimes rioting. In some parts of the country, over 1/3 of the population was wiped out or destroyed. This had heavy spiritual and emotional effects on the people of the Empire.

As the fighting had been mainly in the north, the young Gregorius probably saw little of it. Totila sacked and vacated Rome in 547, destroying most of its ancient population, but in 549 he invited those who were still alive to return to the empty and ruinous streets. It has been hypothesized that young Gregory and his parents, Gordianus and Silvia, retired during that intermission to Gordianus' Sicilian estates, to return in 549.

Gregory had been born into a wealthy noble Roman family with close connections to the church. The Lives in Latin use nobilis but they do not specify from what historical layer the term derives or identify the family. No connection to patrician families of the Roman Republic has been demonstrated. Gregory's great-great-grandfather had been Pope Felix III, but that pope was the nominee of the Gothic king, Theodoric. Gregory's election to the throne of Saint Peter made his family the most distinguished clerical dynasty of the period. The family owned and resided in a villa suburbana on the Caelian Hill, fronting the same street, now the Via di San Gregorio, with the former palaces of the Roman emperors on the Palatine Hill opposite. The north of the street runs into the Coliseum; the south, the Circus Maximus. In Gregory's day the ancient buildings were in ruins and were privately owned. Villas covered the area. Gregory's family also owned working estates in Sicily and around Rome.

Gregory's father, Gordianus, held the position of Regionarius in the Roman Church. Nothing further is known about the position. Gregory's mother, Silvia, was well-born and had a married sister, Pateria, in Sicily. Gregory later had portraits done in fresco in their former home on the Caelian and these were described 300 years later by John the Deacon. Gordianus was tall with a long face and light eyes. He wore a beard. Silvia was tall, had a round face, blue eyes and a cheerful look. They had another son whose name and fate are unknown.

The monks of Saint Andrew's (the ancestral home on the Caelian) had a portrait of Gregory made after his death, which John the Deacon also saw in the 9th century. He reports the picture of a man who was "rather bald" and had a "tawny" beard like his father's and a face that was intermediate in shape between his mother's and father's. The hair that he had on the sides was long and carefully curled. His nose was "thin and straight" and "slightly aquiline". "His forehead was high". He had thick, "subdivided" lips and a chin "of a comely prominence" and "beautiful hands".

Gregory was well educated, with Gregory of Tours reporting that "in grammar, dialectic and rhetoric ... he was second to none...." He wrote correct Latin but did not read or write Greek. He knew Latin authors, natural science, history, mathematics and music and had such a "fluency with imperial law" that he may have trained in law, it has been suggested, "as a preparation for a career in public life."

While his father lived, Gregory took part in Roman political life and at one point was Prefect of the City.

In the modern era, Gregory is often depicted as a man at the border, poised between the Roman and Germanic worlds, between East and West, and above all, perhaps, between the ancient and medieval epochs.

Monastic Years