Disclaimer

Giovanni Battista Tiepolo

Italian Rococo Painter, Etcher, Printmaker & Draftsman

1696 - 1770

Alexander the Great and Campaspe in the Studio of Apelles

by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo: ca 1740

A boyish artist gazes longingly at the regal woman whose portrait he is painting. The young artist is Alexander the Great's court painter, Apelles, whom ancient writers considered the greatest artist of their time. According to Pliny's Natural History of 77 A.D., Alexander commissioned Apelles to paint a portrait of his favorite concubine, Campaspe. The story illustrates art's transformative powers: Apelles fell in love with his sitter as he captured her beauty on canvas. Alexander so esteemed his painter that he presented Campaspe to Apelles as a reward for the portrait.

The tale of Alexander and Apelles, a favorite of Renaissance and Baroque painters, celebrates the power and nobility of painting. Giovanni Battista Tiepolo painted this episode at least three times. For this, the third rendering, he adopted a classicizing style in which antique architectural elements and relief sculptures evoke a sumptuous palace setting. The background provides a focal area for the gaze of Alexander the Great, who appears handsome and self-confident, yet unaware of the charged glances shared by Apelles and Campaspe.

Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, also known as Gianbattista or Giambattista Tiepolo was a Venetian painter and printmaker, considered among the last "Grand Manner" fresco painters from the Venetian Republic.

Giambattista Tiepolo was born in Venice, the last of six children of sea-captain, Domenico Tiepolo and his wife, Orsetta. While the Tiepolo surname belongs to a patrician family, Giambattista's father did not claim patrician status. The future artist was baptized in his parish church (S. Pietro di Castello) as Giovanni Battista, in honor of his godfather, a Venetian nobleman called Giovanni Battista Dorià. His father Domenico died a year after his birth, leaving Orsetta in difficult financial circumstances.

Giambattista was initially a pupil of Gregorio Lazzarini, but the influences from elder contemporaries such as Sebastiano Ricci and Giovanni Battista Piazzetta are stronger in his work. At 19 years of age, Tiepolo completed his first major commission, the Sacrifice of Isaac (now in the Accademia). He left Lazzarini studio in 1717, and was received into the Fraglia guild of painters.

In 1719, Tiepolo married Maria Cecilia Guardi, sister of two contemporary Venetian painters Francesco and Giovanni Antonio Guardi. Together, Tiepolo and his wife had nine children. Four daughters and three sons survived childhood. Two sons, Domenico and Lorenzo, painted with him as his assistants and achieved some independent recognition. His third son became a priest.

A patrician from the Friulian town of Udine, Dionisio Delfino, commissioned from the young Tiepolo the fresco decoration of the chapel and palace (1726-1728). Tiepolo's first masterpieces in Venice were a cycle of enormous canvases painted to decorate a large reception room of Ca' Dolfin, Venice (ca. 1726-1729), depicting ancient battles and triumph.

Frescoes in the Patriarchal Palace in Udine (1726)

by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo

In 1726, Tiepolo began work on the frescoes in the stairwell and in the rooms on the 'piano nobile', or first floor, of the Patriarchal Palace (now the Archiepiscopal Palace) at Udine. This important project had been commissioned by Dionisio Dolfin (1663-1734), a member of a Venetian patrician family, who had held the office of patriarch of Aquileia since 1699.

In the centre of the stairwell ceiling, Tiepolo frescoed the Fall of the Rebel Angels, which he surrounded with eight monochrome scenes from the book of Genesis. He then went on to decorate the Gallery, the so-called Sala Rossa, or Red Room, (at that time, the seat of the ecclesiastical tribunal), and the Throne Room on the piano nobile.

The Gallery features scenes from the lives of the Old Testament patriarchs, likewise inspired by the book of Genesis. The three main episodes, The Three Angels appearing to Abraham, Rachel Hiding the Idols from her Father Laban and The Angel appearing to Sarah are each surrounded by a trompe-l'oeil frame. They are hung alternately with monochrome portraits of prophetesses, which create the illusion of being statues in niches along the walls. On the ceiling, a depiction of The Sacrifice of Isaac occupies centre position, flanked by smaller oval compartments portraying Hagar in the Wilderness and Jacob's Dream. Tiepolo was aided in the realization of this famous ensemble by the quadratura specialist from Ferrara, Girolamo Mengozzi Colonna (1688-1766), with whom he continued to work closely during the years that followed.

On the ceiling of the Sala Rossa, Tiepolo painted The Judgement of Solomon, surrounded by portraits of the prophets Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel and Daniel - a theme appropriate to a room used both as a civil and ecclesiastical tribunal. Finally, there are portraits of Old Testament patriarchs in the Throne Room, but these have deteriorated badly, and not all are by Tiepolo himself.

The ambitious pictorial program of the overall decoration was probably conceived by Dionisio Dolfin himself, with the help of his theological advisers, including Francesco Florio, his vicar-general. The subjects chosen for the pictures were intended to reinforce the legitimacy of the ruling patriarchy, which at that time found itself at the centre of a fierce politico-ecclesiastical struggle between Venice and Vienna. The decoration of the Patriarchal Palace in Udine unquestionably represents the high point in Tiepolo's early career. By portraying figures in 16th century dress, and placing them in landscapes bathed in sun and light, he recalls the magnificently staged scenes of Veronese. The decisive element in this project must be his sense of the theatrical, where the respective subject matter of the picture is presented in a dramatically staged scene. Each figure is assigned a primary or secondary role and the relationships between the protagonists are elucidated by means of a masterly handling of colour. Tiepolo thus transformed the revival of Veronese's art, also favoured by his contemporaries, from a mere stylistic fashion into a pictorial language that was to confirm his own reputation as a representative of the Venetian tradition.

The Three Angels Appearing to Abraham: 1726-29

Abraham kneels in prayer, awed by the appearance of the three angels, who float on a very solid-looking white cloud. The scene illustrates both the promise to make Abraham "a father of many nations" and the favor shown by God towards him, as described in the book of Genesis. Although the divine origin of the angels is made clear by their being placed in the upper portion of the picture, Tiepolo has portrayed them with very human features.

Rachel Hiding the Idols from her Father Laban: 1726-29

The aged Laban stoops over his daughter and demands that she hand over the graven images that she has stolen. She refuses to do so. The action takes place in the encampment where Jacob's caravan rests on its way to Canaan. The staged character of the composition, imaginatively enriched with scenes from everyday life, obscures its Old Testament subject matter, reducing the latter to the status of a vague vision.

The Sacrifice of Isaac: 1726-29

The central ceiling painting depicts the sacrifice of Isaac. Accompanied by a shaft of divine light, an angel floats down on a cloud to stay Abraham's hand just as he is about to slay his son as commanded by God. The ram, which is to be sacrificed in Isaac's place can already be seen on the lower edge of the picture.

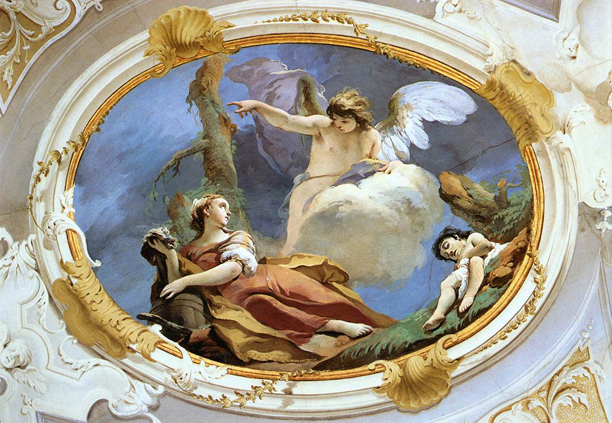

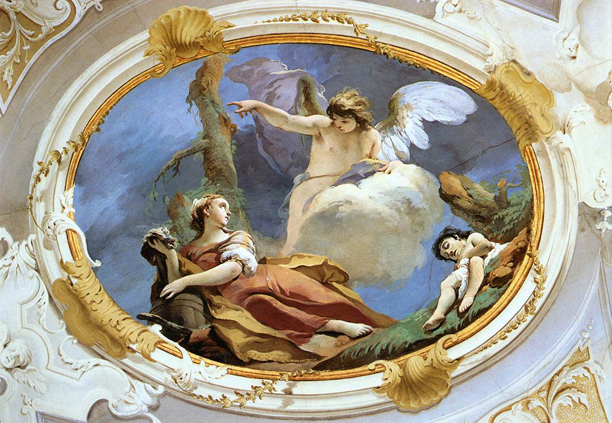

Hagar in the Wilderness: 1726-29

Hagar, Abraham's handmaiden, with whom he had conceived the illegitimate son Ishmael, had been driven from the house by Sarah. The theme of this representation is the appearance of the angel, who saves the completely exhausted Hagar, leaning against an empty barrel in the desert, and her son from dying of thirst, and who prophecies that Ishmael shall be made the "father of many nations". With an energetic gesture he points out the way, which, in reference to the central ceiling painting 'The Sacrifice of Isaac', leads away from the divine light. This symbolizes the biblical belief that the Arab nations derive from Ishmael's line of descendants, who, unlike the children of Isaac, will not inherit the divine Jerusalem.

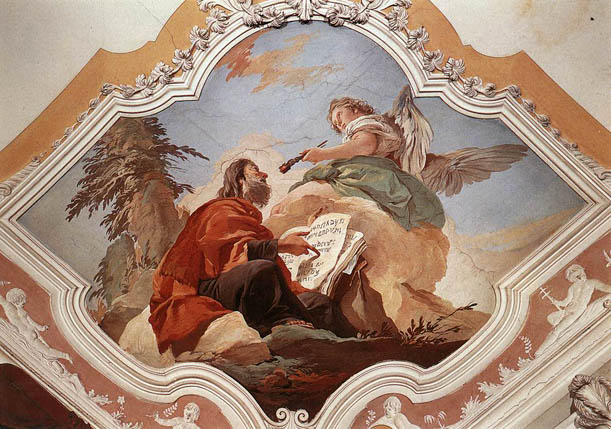

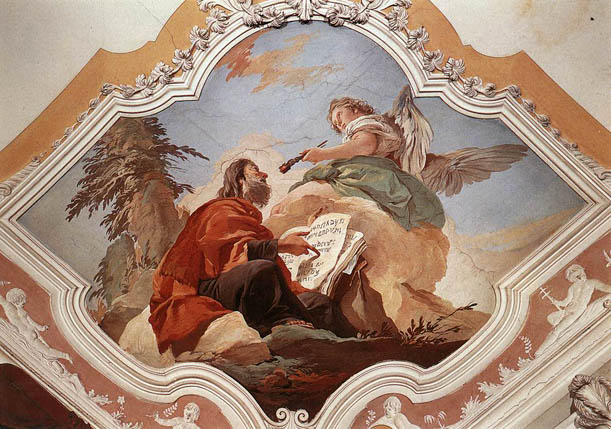

Jacob's Dream: 1726-29

The fresco illustrates Jacob's dream of the ladder to heaven. The artist has moved the ladder, seen ascending into the divine light, from the centre of the picture slightly towards the left. The sleeping Jacob sees in his dream the vision of a divine prophecy, in which he is promised numerous descendants and safe arrival in the land of Canaan under the protection of God himself In form and content, Jacob represents the antithesis of Hagar and Ishmael (shown on the next fresco), since his line leads directly to Christ. This is reflected compositionally in the way the figure of Jacob is aligned towards the central fresco, The Sacrifice of Isaac.

The Judgment of Solomon: 1726-29

The large oblong painting in the centre of the ceiling shows a wide flight of stairs, seen from below at an oblique angle, on which King Solomon is enthroned in front of a canopy of cloth, acting in his capacity as a judge. The moment in which the true mother is revealed is re-enacted here. Contrary to what it says in the Bible, a crowd of onlookers, including a dog and a dwarf, are present as Solomon makes his judgment that the child shall be "divided equally" by the sword. The true mother prevents this awful deed in order to save her child, while the dead infant of the false mother in the foreground is a reference to the cause of events.

The Prophet Isaiah: 1726-29

The painting depicts the Prophet Isaiah at the moment where he is called to prophecy. The approaching angel holds a piece of burning coal to his lips with tongs and so brings about the forgiveness of his sins. Isaiah hears the voice of the Lord and agrees to his mission.

He was soon in high demand, which he matched with an astounding prolificacy. He painted canvases for churches such as that of Verolanuova (1735-40), for the Scuola dei Carmini (1740-47), and the Scalzi 1743-1744), a ceiling for the Palazzi Archinto and Casati-Dugnani in Milan (1731), the Colleoni Chapel in Bergamo (1732-1733), a ceiling for the Gesuati (Santa Maria del Rosario) in Venice of Saint Dominic Instituting the Rosary (1737-39), Palazzo Clerici, Milan (1740), decorations for Villa Cordellini at Montecchio Maggiore (1743-1744) and for the ballroom of the Palazzo Labia, now a television studio in Venice, showing the Story of Cleopatra (1745-1750).

Frescoes in the Palazzo Labia in Venice (1746-47)

by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo

One of the most important commissions carried out by Tiepolo in the 1740's was, without a doubt, the decoration of the Palazzo Labia in Venice. The Labia family was of Spanish origin and had only recently joined the Venetian patriciate. Tiepolo's frescoes reflect the family's great desire to create an impression: they are the greatest secular decoration he ever produced in Venice.

The great hall of the palace, which rises up two storeys, is entirely covered by frescoes, which Tiepolo executed in collaboration with Girolamo Mengozzi Colonna, the quadratura specialist. The walls of the room have been opened up by an illusionistic simulated architecture, into which the real doors and windows have been integrated. In this way, a multi-layered system of fictive interior and exterior spaces has been created, supported by a massive architectural framework of multicoloured painted marble. Tiepolo's scenes, The Meeting of Anthony and Cleopatra and The Banquet of Cleopatra, are staged within this illusory architecture, the scenic framework lending them a theatrical character.

Tiepolo's method of representation, characterized by wit and irony, is enriched by many narrative details. Servants, soldiers, musicians and other figures on rostrums and balconies populate the room in so natural a manner, that the viewer begins to doubt whether they belong to Cleopatra's entourage or to the real staff of the palace. The central ceiling fresco depicts The Triumph of Bellerophon over Time, flanked by four monochrome scenes of mythological and allegorical characters.

The Meeting of Anthony and Cleopatra: 1746-47

The arrival of Anthony and his entourage is staged as an illusionistic vista within a feigned architectural framework. While the sails of the Roman fleet can still be glimpsed in the background, the magnificently costumed figures move off towards Cleopatra's palace in the manner of a triumphal procession. In the foreground, Anthony and Cleopatra lead the way, already portrayed as a couple. Tiepolo ironically plays around with different levels of reality by having Anthony point to the entrance of the palace, which is at the same time the room in which the viewer stands, and to which the steps in the picture also seem to lead down.

The Meeting of Anthony and Cleopatra (Detail): 1746-47

_1746_47.jpg)

This section shows Cleopatra and Anthony in the middle of a group of men of all ages in Oriental dress, the latter presenting a large variation of different types of figure. The main actors are emphasized by their magnificent costumes. Cleopatra's robes bring to mind the bridal dress for a royal wedding, like the one Tiepolo would eventually execute in his Würzburg frescoes.

The Banquet of Cleopatra: 1746-47

The table for Cleopatra's banquet is laid out in front of a portico, behind which the sails of the Raman fleet are visible. The somewhat static ordering of the main figures is relaxed by the ironic positioning in the foreground of the little dog and the dwarf, who drags himself with difficulty up the steps towards the table. Cleopatra's exposed decollete is meant as a reference to the by now advanced stage of her relationship with Anthony. In contrast to Tiepolo's Melbourne picture of the same subject, the erotic and witty interpretation of historical events is given prominence over the festive setting itself.

Bellerophon on Pegasus: 1746-47

The ceiling fresco is conceived as an illusionistic view of the heavens, where Bellerophon rides upon the white winged-steed Pegasus towards Glory, untroubled by the old man with the lance at the bottom of the picture, who can no longer harm him. Glory is personified by a female figure in golden yellow robes, floating on a cloud next to a pyramid, the traditional symbol of eternity.

By 1750, Tiepolo's reputation was firmly established throughout Europe, and accompanied by his son Giandomenico, he traveled to Wurzburg at the call of Prince Bishop Karl Philipp von Greiffenklau in 1750, where he resided for three years and executed magnificent ceiling paintings in the New Residenz palace (completed 1744). His painting for the grandiose Neumann-designed entrance staircase (Treppenhaus) is the most massive ceiling fresco in the world at 7287 square feet, and was completed in collaboration with his sons, Giandomenico and Lorenzo. His Allegory of the Planets and Continents depicts Apollo, embarking on his daily course; deities around him symbolize the planets; allegorical figures (on the cornice) represent the four continents, notably including America. He also painted frescoes for the Kaisersaal salon.

Frescoes in the Würzburg Residenz (1751-53)

by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo

In December 1750, Tiepolo, accompanied by his sons Giandomenico and Lorenzo (1736-1776), arrived in Wurzburg where, at the invitation of Prince-Bishop Carl Phillip von Greiffenclau, he was to fresco the large dining room - known as the Kaisersaal, or Imperial Hall - in the newly-built Residence of the Prince-Bishops designed by the architect Balthasar Neumann (1687-1753). The decorative programme of the Imperial Hall comprises the central ceiling fresco - an allegorical portrayal of the Genius Imperii, towards whom Apollo is conducting the Burgundian bride - and two historical scenes, The Marriage of the Emperor Frederick Barbarossa to Beatrice of Burgundy and The Investiture of Herold as Duke of Franconia by Emperor Frederick Barbarossa at the Imperial Diet in Wurzburg in 1168, on either side of the room. Representations of mercenary footsoldiers and courtiers under the windows, monochrome allegorical scenes in the lunettes and supra porte paintings by Tiepolo's son Giandomenico complete the decoration of the room. Tiepolo had begun preparatory sketches as soon as he arrived in Wurzburg; the ceiling fresco was then painted in the spring of 1751 and the two lateral wall frescoes were completed the following year.

The Prince-Bishop was so pleased with the finished decoration of the Imperial Hall that, in 1752, he also invited Tiepolo to fresco the ceiling of the stairwell. The splendid staircase is itself an architectural masterpiece by the designer Balthasar Neumann, and provides an artistic setting for the ceremonial path followed by the visitor from the entrance to the Residence up to the Imperial Hall on the first floor.

In April of that year, Tiepolo presented the Prince-Bishop with an oil sketch, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The sketch outlines the basic essentials of the themes of the work, which would later be realized: the four known parts of the world (Europe, Asia, Africa and America) are arranged along the sides of the picture, with Apollo and the deities of Olympus at its centre, representing the sun rising over the world. Nevertheless, the realized version differs from the sketch in essential points, and shows to what extent the artist was prepared to adapt his design to suit the location and in accordance with the requirements of his patron. The Wurzburg frescoes are considered the high point of Tiepolo's artistic career.

View of the Imperial Hall

The magnificently-decorated Imperial Hall is the highpoint of the ceremonial sequence of public rooms in the Residence. The room is high and wide, well-lit by tall windows on three sides, and is situated in the central axis of the Residence overlooking the garden. It rises from the ground plan of an elongated octagon and is vaulted by an imposing oval cupola with ten, for the most part windowed, lunettes. Having passed through the White Room, with its neutral white stucco decoration by Antonio Bossi, the visitor enters the Imperial Hall someway down its length and is at first overwhelmed by the polychromatic variety of its decoration: by the walls with its divisions of half columns in red stucco marble, by the white and gold stucco decoration of the vault, by the areas of shell work, by the sculptures and, not least, by Tiepolo's frescoes. In the Imperial Hall, architecture, ornamental structuring and painted decoration form an incomparable unity and so create one of the most beautiful secular rooms of the Baroque period.

Tiepolo's frescoes, too, have been designed to make an impact on the viewer as he enters the room. The central ceiling fresco is intended to bring together the themes of the two wall paintings, and to illustrate these in a generally allegorical form.

This picture shows the view towards the south end of the Imperial Hall and the portrayal of the marriage of Barbarossa and Beatrice of Burgundy, and shows how the fresco is incorporated into the opulence of the overall decoration.

The Marriage of the Emperor Frederick Barbarossa to Beatrice of Burgundy: 1751

The Emperor Frederick Barbarossa and his wife Beatrice kneel before Gebhard, Bishop of Wurzburg. On the right of the picture, the royal household and dignitaries of empire are gathered, while the father of the bride, Count Raynald of Burgundy, kneels on the steps to the left of the altar, accompanied by two pageboys. The court jester, seen from behind, occupies a prominent position in the foreground at the foot of the steps to the altar, an example of Tiepolo's penchant for introducing witty and frivolous ideas to the agreed pictorial subject matter. The steps to the altar lead us into the picture and, along with the colossal background architecture, create great spatial depth. The musicians on the balcony in the background are a favorite motif of Tiepolo, which he uses to help make the historical subject matter topical.

The Investiture of Herold as Duke of Franconia: 1751

The Emperor sits on a golden throne, flanked by statue of Hercules and Minerva, and holds his scepter out towards Bishop Herold, who touches it with his fingers he takes the oath. To the left and right of the throne, secular and ecclesiastical dignitaries are represented in ceremonial dress, including the Imperial Chancellor, who reads aloud the deed of Investiture, and the Imperial Marshall, who holds up his unsheathed sword. The architecture in the background conforms to a pictorial motif inspired by Veronese and often used by Tiepolo in his paintings in order to give the scene a festive setting.

View of the Stairwell

From this vantage point the viewer sees the representation of the personification of Europe for the first time, whereas the other Continents and the center of the heavens cannot be seen. Neither can the actual dimensions of the hall be recognized until higher up.

The splendid staircase is itself an architectural masterpiece by the designer Balthasar Neumann, and provides an artistic setting for the ceremonial path followed by the visitor from the entrance to the Residence up to the Imperial Hall on the first floor. The visitor arrives at the foot of the stairs by way of a dimly lit vestibule, whose shallow vault creates an impression of heaviness. Here, he catches his first glimpse of the brighter area of the upper storey overhead. The first flight of stairs brings him to a mezzanine landing, where he must change direction and take either of the two sets of stairs, to the left or to the right, which ascend to the next level. Having arrived on the upper floor, he is overwhelmed by the enormous extent of a great room which is spanned by a single giant cove vault, without further supports. The stairwell, whose large, uninterrupted ceiling surface stood entirely at Tiepolo's disposal, is a technically brilliant achievement for its time.

Stairwell Seen from the Gallery Looking South East

The photo shows the staircase rising from the ground-floor vestibule to the brightly lit, spacious hall at the top of the stairwell. We can see the enormous scale on which it has been built and the way in which it harmonizes with Tiepolo's ceiling fresco.

Apollo and the Continents: 1752-53

The picture shows an overall view of the ceiling, photographed from below.

The perspective shows a distortion at the edges of the overall view of the ceiling fresco tell us that this was never intended as a vantage point for the visitor. Instead, the fresco was to open out to the viewer as he ascended the staircase. Apollo is portrayed in the centre of the heavens, Venus and Mars rest on a cloud below him, while the zodiac appears on a band behind them with the four seasons to the left. The Horae can be recognized by their butterfly wings. The upper part of the fresco is meant to be viewed from the opposite angle and shows Mercury and, a little below him, the gods Diana, Jupiter and Saturn.

The composition of the ceiling fresco takes into account the many viewpoints available to the visitor, who changes direction several times during his climb up the stairs, and who cannot take in the whole fresco at a glance.

Tiepolo's achievements in composing this fresco are twofold: he takes into consideration the way in which only parts of the fresco are visible to the viewer as he climbs, and he presents independent pieces which nevertheless fuse into a harmonic whole. From the foot of the stairs the viewer first sees the continent of America, whose personification points with outstretched arm to a banner showing the mythical creature the griffin, a first allusion to the client. On entering the stairwell, a wider picture is revealed, giving a view of the dramatic cloud formations which push open the skies, and of the figure of Apollo, bathed in radiant light. Halfway up the first flight of stairs, more of the long sides of the fresco are revealed, with Africa on the right and Asia on the left. The groups of figures await the visitor almost like a court society. After this first flight, the viewer must change direction and now sees the portrayal of Europe for the first time on the short side opposite. The flourishing arts are symbolized here, partly personified by the artists involved in the construction of the Residence. Above them, the Prince-Bishop's portrait medallion is borne aloft through the heavens by geni and allegorical figures. Like Apollo, who cannot be seen from here, it too lets its light shine forth over the world.

In comparison to the other Continents, the Europa fresco is statically conceived. This, and the sometimes frontal arrangement of its figures, causes the viewer to pause and so constitutes a first high point on the way to the Imperial Hall. The fresco was, therefore, never laid out with an overall view in mind, and the criticisms of the largely empty areas of sky at its centre which were later to be frequently voiced, are thus unfounded. Instead we are captivated by the harmonic perfection through which both architecture and painted decoration serve the same purpose: the magnificent staging of the ceremonial path through the Residence.

Apollo and the Continents (Detail): 1752-53

_1752_53.jpg)

Apollo has left his palace and is floating slowly downward, accompanied by two of the Horae, while the rising sun shines out behind him. This is a mythological representation of the sun rising over the Earth, which is symbolized by the surrounding Continents. The sun appears as a life-giving force which determines the course of the days, months and years.

Apollo and the Continents

(America Left Hand Side): 1752-53

_1752_53.jpg)

The personification of the American Continent rides on a huge crocodile. With her naked upper torso and feathered head-dress, she represents the uncivilized world. She is surrounded by people characterized as wild creatures, who hunt with bow and arrow. The figure reclining below her holds a horn of plenty as a symbol of the riches and fertility of this part of the world, which was of the greatest interest to the Europeans.

Apollo and the Continents

(America Right Hand Side): 1752-53

_1752_53.jpg)

The Europeans of Tiepolo's day imagined the inhabitants of the continent of America to be barely civilized; a belief symbolized in his depiction of human beings who look to nature for sustenance and who eat their meals in the open air. It was assumed that cannibalism was practiced in this part of the world, and the heads which lie around in the foreground allude to this. As a capriccio, Tiepolo has placed in the foreground the portrayal of a European, who hides behind a stone slab and secretly observes the continent.

Apollo and the Continents

(Africa Left Hand Side): 1752-53

_1752_53.jpg)

Here, too, it is Africa's flourishing trade which is the focus of the representation, in which portly merchants are occupied with their wares, stored in large bales and barrels. The monkey and the ostrich in the foreground, like the dromedary, were considered animals characteristic of Africa, but here they are intended more as playful additions to the portrayal.

Apollo and the Continents

(Africa Right Hand Side): 1752-53

_1752_53.jpg)

The personification of Africa sits astride a dromedary in the hustle and bustle of a market scene, surrounded by Negroes, Orientals and Europeans. She is being offered an incense burner, which, along with other vessels on magnificent cloths and the tusks of ivory, symbolize the goods and the riches of the continent, so coveted by the Europeans. Africa is clearly depicted as a much more civilized place than America.

Apollo and the Continents

(Asia Obelisk Group): 1752-53

_1752_53.jpg)

The meaning of the various individual figures in the so-called obelisk group, which conceals a complex symbolic language, has not yet been sufficiently explained. The female figure in the yellow coat in front of the pyramid is often interpreted as the personification of Princedom, while the old man with the hat behind the hieroglyphic stone seems to be a sage. The symbol of the snake entwined around a rod reminds us of the staff of Aesculapius and refers to the art of medicine. The composition of the scene is highly reminiscent of Tiepolo's Capricci series of prints of 1743, or of the Scherzi di fantasia, which followed a few years later.

Apollo and the Continents

(Asia Figure of Asia): 1752-53

_1752_53.jpg)

The magnificently costumed personification of Asia rides on a splendidly adorned elephant in the midst of scenes which are meant to distinguish the continent as the birthplace of writing, of science and of kingship. The prisoners lying on the ground and the army of soldiers behind them allude to the military importance of the continent; the parrot stands for the animal kingdom.

Apollo and the Continents

(Europe Overall View): 1752-53

_1752_53.jpg)

The personification of Europe, enthroned on a stone podium and resting against a bull, is surrounded by figures that are meant to refer to the importance of religion and the visual arts on this continent. In the left foreground, a figure symbolizing Painting kneels over a globe, palette and brush in hand. A musician on the right-hand side symbolizes Music, while the man facing the viewer and surrounded by the attributes of sculpture represents that branch of the arts. Tiepolo has lent him the features of the stucco artist Antonio Bossi. The figure reclining in the foreground is a portrait of Balthasar Neumann, who designed the Residence. His uniform refers to his rank as colonel in the Artillery. On the extreme left, Tiepolo portrayed himself and his son Giandomenico along with the painter Franz Ignaz Roth.

Apollo and the Continents (Europe Detail): 1752-53

_Two.jpg)

The portrait medallion of Carl Philipp von Greiffenclau is borne aloft above the personification of Europe. To the left, the goddess Fame sounds her trumpet and supports the likeness, while the winged personification of Virtue holds a crown over it. A griffin, the heraldic animal of the Greiffenclau family, can be seen at the bottom edge of the medallion. The flapping red imperial mantle, trimmed with ermine, emphasizes the ascension and the glory of the Prince-Bishop, as he soars up to the deities of Olympus visible in the background.

He then returned to Venice in 1753, Tiepolo was now richly in demand locally and abroad, where he was elected President of the Academy of Padua. He now completed theatrical frescoes for churches; the Triumph of Faith for the Chiesa della Pietà; panel frescos for Ca' Rezzonico (which now also holds his ceiling fresco from the Palazzo Barbarigo); and paintings for patrician villas in the Venetian countryside, such as Villa Valmarana (Vicenza) and a large panegyric ceiling for the now nearly vacant Villa Pisani in Stra.

Frescoes in the Villa Valmarana in Vicenza (1757)

by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo

In 1757, Tiepolo and his son Giandomenico were invited to Vicenza to fresco rooms in the Villa Valmarana and in the adjoining guest quarters, the so-called 'foresteria'. Their patron was Count Giustino Valmarana, a scholar and theater enthusiast. Tiepolo frescoed the vestibule and four ground-floor rooms, while his son executed the decoration in the adjacent guest house. Giandomenico's lively genre scenes featuring peasants and merchants were intended to form a marked contrast with Giambattista's noble and tragic themes in the Villa, borrowed from famous works of Greek, Roman, and Italian literature. The Iliad of Homer (c. 750-650 BC), the Aeneid of Virgil (70-19 BC), Orlando furioso by Ariosto (1474-1533) and Gerusalemme liberata by Tasso (1544-1595) were the sources for the different scenes which, because of the small, almost intimate proportions of the rooms, are narrated with a certain simplicity and using a limited number of figures.

The characteristic element of the frescoes in the Villa Valmarana is the way in which the representations have been conceived as theatrical scenes, in which the various heroes act as if on the stage.

The Sacrifice of Iphigenia: 1757

The sacrifice of Iphigenia takes place in an illusionistic hall of columns, which partially block the spectator's view of the scene. In the centre of the picture, Iphigenia lies on the altar, the priest ready to apply the knife. However, the deer hind sent by Diana to save Iphigenia is already descending on a cloud, accompanied by two putti, from the left towards the altar. Agamemnon stands somewhat isolated, on the very right of the picture, covering his face in order not to have to witness the death of his daughter. As onlookers, Tiepolo has gathered together warriors and Orientals, one of whom has placed his arm around a column, adding a perfect touch to the illusionism of the simulated architecture.

Eurybates and Talthybios Lead Briseis to Agamemmon: 1757

Agamemnon had Achilles' favorite slave, Briseis, handed over to him, in return for having been forced to surrender Chryseis, the daughter of a priest of Apollo. The representation shows an imperious-looking Agamemnon, in a kind of loggia in the foreground, awaiting the slave girl, who is being brought to him by two soldiers. The tents of the Greek army appear in the background. The panoramic landscape completes the scenery.

The Rage of Achilles: 1757

Outraged at having lost his beloved, Achilles draws his sword to kill Agamemnon. The sudden appearance of the goddess Minerva, who, in this fresco, has grabbed Achilles by the hair, prevents the act of violence. Agamemnon stands to the left and tries to shield himself with his cloak, while in the background, in front of a rounded temple, a huddled row of Greek soldiers observes the scene. What stands out in this fresco is the facial expression of Achilles, almost contorted by rage into a grimace, something seldom found in Tiepolo.

Venus Appearing to Aeneas on the Shores of Carthage: 1757

During the destruction of Troy, Aeneas flees the city, at the order of the gods, to establish a new city in Italy. A storm drives him to the shores of Carthage. Accompanied by Achates, he makes his way to Dido, the queen of Carthage. His mother Venus appears to him along the way and carries the two men, enveloped in a cloud, unscathed to Carthage. Aeneas and Achates stand on the left of the picture, while Venus, accompanied by Amor, hovers above them to the right, and is in the act of transporting them on a cloud. Ships lie at anchor in the background.

Aeneas Introducing Cupid Dressed as Ascanius to Dido: 1757

Queen Dido of Carthage has welcomed Aeneas. By way of thanks, the latter has his son Ascanius brought from the ship with gifts for the hostess. Venus swaps him for Amor underway, which leads to Aeneas and Dido falling in love. The subject matter of the fresco is the presentation of Aeneas' son, but the wings and the quiver of arrows point to the true identity of the god of Love. On the left, Dido, in splendid robes, sits enthroned underneath a kind of baldachin. The scene is furnished with an architectural backdrop typical of Tiepolo.

Mercury Appearing to Aeneas: 1757

Mercury, sent by Zeus, appears to the sleeping Aeneas in a dream and reminds him of his orders to establish a city in Italy. Aeneas consequently abandons Dido. The fresco shows the hero asleep on a rock in front of an unidentified landscape, while Mercury floats on a cloud above him. His hand points out of the picture, and so indicates the imminent departure of Aeneas from Carthage.

Thetis Consoling Achilles: 1757

Achilles sits on the balustrade of a balcony in a loggia on the seashore, his legs dangling down in an illusionistic fashion into the viewer's space, and bemoans his fate. Out in the water, his mother, the sea-goddess Thetis, appears in the company of a Nereid, and attempts to console him. The picture, largely bereft of figures, with its expansive view of the sea attempts to capture the sad mood of the hero.

Angelica and Medoro with the Shepherds: 1757

The fresco portrays a scene from the love story of the young knight and the maiden Angelica from Ariosto's "Orlando furioso". The two are given temporary shelter by a shepherd couple, once Angelica has found and cared for the wounded Medoro. As a way of thanking them for their hospitality, Medoro gives them the ring which Angelica had previously received from Orlando. The simple depiction of the peasants brings to mind Giandomenico's country scenes in the foresteria.

Angelica Carving Medoro's Name on a Tree: 1757

In front of an extensive, yet barely-developed landscape, Angelica carves the name of her beloved onto a tree. She has her back to the viewer and is looking down at Medoro, who sits to her left.

Rinaldo Abandoning Armida: 1757

During the crusades, Rinaldo, who had allowed himself to be carried off to an island by the sorceress Armida, stayed away from the fighting. Two warriors were sent to bring him back. They discover him in Armida's enchanted garden and hold up to him a shield, as a mirror in which he recognizes that he has neglected his duties. He abandons the sorceress and returns to the battle. The scene is divided down the middle by a tree. Armida sits to its right and attempts to make Rinaldo stay. He is preparing to depart with his companions on the left. A ship awaits him in the background.

Apollo and Diana: 1757

Giambattista chose to decorate only one of the rooms in the foresteria at the Villa Valmarana. In the so-called Olympus Room he frescoed Mars, Venus and Amor; Mercury; Time; Jupiter; and Apollo and Diana. This last fresco shows the two deities sitting on a cloud. Apollo, who faces the viewer, holds his lyre in his right hand and his quiver of arrows in his left, while Diana, partly concealed and with her back to the viewer, reclines to his right. Apollo's golden yellow robe and the yellowish color of the clouds are meant to allude to his office as Sun God.

In celebrated frescoes at the Palazzo Labia, he depicted two frescoes on the life of Cleopatra: Meeting of Anthony and Cleopatra and Banquet of Cleopatra, as well as a central ceiling fresco depicts Triumph of Bellerophon over Time. He collaborated with an expert in perspective, Girolamo Mengozzi Colonna. Colonna who also designed sets for opera highlights the increasing tendency towards composition as a staged fiction in his frescoes. The architecture of the Banquet fresco also recalls Veronese's Wedding at Cannae.

In 1761, Charles III commissioned from the painter a large ceiling fresco to decorate the throne room of the royal palace of Madrid. The panegyric theme is the Apotheosis of Spain. In Spain, he incurred the jealousy and the bitter opposition of Anton Raphael Mengs.

Frescoes in the Royal Palace in Madrid (1762-66)

by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo

Tiepolo and his sons arrived in Madrid on 4 June 1762. In spite of his advanced age, he was extremely productive in the remaining eight years of his life, creating an impressive number of large frescos and altarpieces in Madrid. He appears to have been very well aware of the fact that the time for his art, in which he portrayed triumphal apotheoses and the glorification of the virtues of his clients by means of illusionistic settings, was well and truly over. Tiepolo was one of the few European painters still working on a monumental scale and able to realize extensive interior decorations. King Charles III of Spain had thus made the right choice in commissioning this artist to decorate the Throne Room of the Royal Palace in Madrid, only recently built to designs by Filippo Juvarra (1676-1736) by his pupil Sacchetti (died 1764).

Tiepolo had already completed the oil sketch for the ceiling fresco in the Throne Room, The Glory of Spain, in Venice. The subject portrayed is the glorification of the Spanish nation, which in the course of the 16th and 17th centuries had developed into one of the leading European powers, politically, geographically and culturally. The compositional scheme of the ceiling fresco in the Throne Room is a brilliant synthesis of decorative elements from Tiepolo's earlier works, such as those in the Residence in Würzburg and the Villa Pisani in Stra. Tiepolo reproduces his previous work in a new setting without compromising the original character of the fresco or giving the impression of its being a copy. In spite of the complex structure of the numerous figural elements and the intricate meaning of its content, and thanks to the largely empty expanse of sky, the fresco appears to be one of the airiest Tiepolo ever created.

Work on the Throne Room was completed in 1764. The King was pleased with the result and asked Tiepolo to carry out further decorative work within the palace. The painting of a ceiling fresco in the Guard Room followed. In the Queen's antechamber, a small room adjoining the Throne Room, Tiepolo created the ceiling fresco The Apotheosis of the Spanish Monarchy.

Glory of Spain (Detail): 1762-66

_One_1762_66.jpg)

The loading of a European ship with the treasures of the American Continent is depicted in a direct allusion to the discovery of America by Christopher Columbus and to the Spanish Conquest of the New World in the l6th century. The two Red Indians in the foreground, who throw themselves to the ground in front of the ship, symbolize the Europeans' victory over the natives.

Glory of Spain (Detail): 1762-66

_Two_1762_66.jpg)

A part of the African Continent appears at the lower edge of the picture, characterized by the ostrich. In the clouds, we see Jupiter and his eagle, Minerva, Bacchus, and another divinity. From this angle we can again see that scenes and figural groupings, which, in his other fresco cycles, Tiepolo linked together in an organic fashion, are here divided up and separated from one another in spite of the trompe-l'oeil breaching of the framework.

Glory of Spain (Detail): 1762-66

_Three_1762_66.jpg)

The sea-goddess Thetis hovers on a cloud, together with her spouse Oceanus, and holds aloft a shell filled with treasures. Tritons and Nereids, who are meant to symbolize the riches of the sea, accompany the scene. The attempt to bridge the austere Classical golden frame using the group of figures and the orange tree at the lower edge of the picture (possibly a personification of the Province of Aragon), and to create the typical connection between the fresco and the space occupied by the viewer does not succeed here.

The Apotheosis of the Spanish Monarchy: 1762-66

The lower half of the oval ceiling fresco displays the personification of the Spanish Monarchy, enthroned among the clouds and crowned by Mercury. To the right above her, Apollo stands in front of his sun-chariot, while in the upper half of the picture we see Jupiter on his throne, Fame with trumpets, as well as putti and other divinities. Below the Spanish monarchy, the personification of Ancient Castilia, the most important Spanish province, appears with a tower, below that are Venus and Mars, while the meeting of the Continents Europe and Africa at Spanish Gibraltar is symbolized at the bottom left by the Pillars of Hercules.

Venus and Vulcan: 1762-66

Tiepolo's fresco on the vault of the Halberdiers' Room in the Royal Palace depicts Venus charging Vulcan to forge the arms of Aeneas, a topic taken from Virgil's Aeneid and chosen for the military function of the room. The stucco decoration was executed by Bartolomeo Rusca.

Tiepolo died in Madrid on March 27, 1770.

After his death, the rise of stern Neoclassicism and the post-revolutionary decline of royal absolutism led to the slow decline of the Tiepolo style, but had failed to dent his impact on artistic progress. By 1772 Tiepolo was sufficiently famous to be documented as painter to Doge Giovanni Cornaro, in charge of the decoration of Palazzo Mocenigo a San Polo.

In his most fluid elaborations, Tiepolo has closest affinity to Ricci, Piazzetta, and Federico Bencovich. He is a shadow less fresco artist, a sunnier rococo Pietro da Cortona. His sumptuous historical set-pieces are enveloped in a regal luminosity. He is principally known for his fresco work, particularly his panegyric ceilings. These followed the Baroque tradition begun a century before by Pietro da Cortona, converting roof to painted sky, elevating petty aristocrats to divine status, and allowing for vast compositions that merged with the delicate ornamentation of the stucco frames. Like Luca Giordano, his palette was muted, almost water-color like. Like Giordano, he was prolific. With an unrivaled Sprezzatura, he painted worlds of fresco, and some such as the walls of Villa Valmarana in Vicenza, not only peer into the mythologic scenes, but are meant to relocate viewers into their midst. The earliest example of this is perhaps his canvases in the Ca' Dolfin, which allowed Tiepolo to introduce exuberant costumes, classical sculpture, and action that appears to spill from the frames into the room. Originally set into recesses, they were surrounded with frescoed frames.

While his painting is infused with the Venetian spirit, his luminosity is not seen in the previous masters; however, Tiepolo is considered the last "Olympian" painter of the Venetian Republic. Like Titian before him, Tiepolo was an international star, treasured by royalty far afield for his ability to depict glory in fresco. His children developed similar, but distinctive styles.

Paintings up to 1740

by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo

The Martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew: 1722

To the Testament of Andrea Stazio, a Venetian nobleman who died in 1722, we owe a cycle of paintings of great importance in the history of Venetian art. The will provided that twelve canvases should be painted for the church of San Stae (Venetian for Saint Eustace). All similar in size, they depict episodes in the lives of the Apostles and their martyrdom. The commission was given to twelve different Venetian painter, ranging from the aged Nicolò Bambini, then seventy-one, through to Giambattista Tiepolo, almost at the start of his career.

All the paintings were completed within a few months, in 1722 and early 1723. The artists were the following in alphabetic order: Antonio Balestra, Nicolo Bambini, Gregorio Lazzarini, Silvestro Manaigo, Giambattista Mariotti, Giovanni Antonio Pellegrini, Giambattista Piazzetta, Giambattista Pittoni, Sebastiano Ricci, Giambattista Tiepolo, Angelo Trevisano and Pietro Uberti. They vied with each other to transform the church into a remarkable showcase of currents and developments in eighteenth-century Venetian art.

Tiepolo's painting is part of the cycle of the Apostles which as a 'collective exhibition' fortunately remained intact in the choir of the Baroque church San Stae, giving an outline of Venetian painting of the period. The subject of the painting is the 'Martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew', whose tormentors are on the point of flaying him alive. The awfulness of the scene is matched by the extremely powerful composition which places the writhing body of the saint along the diagonal between the two henchmen. The eerie contrast between light and shade makes the scene all the more vivid. The expressive gesture with which the despairing saint stretches his arm heavenward transforms the picture into a wonderful depiction of divine grace, the existence of which is already signaled by the bright light emanating from above.

This painting was inspired by Piazzetta and is placed opposite his Saint James in San Stae, and it is almost its mirror image. As in the other work, the structure dynamically offsets conflicting forces, rendered by means of a chiastic arrangement of diagonals and clear contrasts of light and shade.

Apollo and Marsyas: 1720-22

With the similar sized paintings of Diana and Acteon, Diana and Callisto, and the Rape of Europa, this painting belonged to a single decorative series, probably in a building in Belluno.

The Rape of Europa: ca 1725

Giambattista Tiepolo very early withdrew from the lessons he was receiving from Gregorio Lazzarini, an academic of mediocre talents, and developed rather towards the vigorous chiaroscuro of Federico Bencovich and Piazzetta, rendering their solutions still more refined and precious by using colors which have an absolutely unmistakable, densely fused luminous vibration to them. At the end of this fundamental experience comes the canvas of 'The Rape of Europa' in which the mythological subject is depicted in an airy, disenchanted transcription which at times becomes almost caricature. The severity of the pattern of chiaroscuro loses intensity in favor of refinement of chromatic notes in an interpretation of space open and articulated in depth which is as far from Bencovich and Piazzetta as it is consonant with the taste of Sebastiano Ricci. And the very lively spatial and luministic framework in which the figures take their places with such easy confidence offers a foretaste of the supreme gifts of Tiepolo as an 'organizer' of paintings.

Temptations of Saint Anthony

This is a juvenile work by the artist.

The Force of Eloquence: ca 1723

The frescoes of mythological and allegorical subjects in the main hall and two other chambers of the Palazzo Sandi are among Tiepolo's greatest works. They reveal that he was already master of a distinctive and independent style.

The picture shows Bellerophon on Pegasus slaying the Chimera.

Education of the Virgin: 1732

The figures in this altarpiece are portrayed more as the heroines of noble dramas than as saints. They combine true pathos with elegant sensuality, as if they were creatures of some higher human species. At the same time, however, they are firmly linked to our sense of everyday life through the descriptive details which are so naturalistic as to border on trompe-l'oeil.

In the center of the representation, in front of a magnificent architectural backdrop, stands Mary as a young girl, reading from an open book, and instructed by her mother, who sits next to her. Her father, standing to her right, is deep in prayer and has his eyes raised towards Heaven. What is striking about the composition is the diagonal line which runs from the three angels' heads beneath the book to the three large angels above Mary, and which symbolizes the way to the Kingdom of Heaven.

Abraham Praying before the Three Angels: ca 1730

This is a youthful painting by Tiepolo which contrast with the sixteenth-century interior of the Scuola Grande di San Rocco where it is on display.

Nativity: 1732

This is one of Tiepolo's most interesting and least known religious works. Set in a room (the Sacristy of the Canonici) that is rarely visited, in the midst of golden mosaics, it offers the excitement of a true discovery.

John the Baptist Preaching: 1732-33

The impressive figure of John the Baptist, delivering his sermon with raised forefinger from the top of a rock in the landscape, dominates the right-hand side of the picture. His cross staff and the lamb at his feet refer to the fate of Christ. The left-hand side of the picture is almost completely taken up by men, women and children, who listen spellbound to the sermon. The young woman placed in the very centre of the picture breast-feeding her child, who thus conforms to the standardized portrayal of the Madonna and Child, can be understood as an allusion to the birth of Christ, which is the subject of John's sermon.

The Beheading of John the Baptist: 1732-33

Tiepolo presents us with a particularly graphic depiction of the beheading of John the Baptist, which takes place in a stone dungeon. The torso of the beheaded man lies on a raised stone podium, the blood dripping down the few steps which lead to it, while the executioner, who stands over him, holds up the severed head. To the left, a female servant approaches with a salver. Behind her, a young woman turns from the scene in horror. On the right-hand side, Salome, who has ordered the murder, stands in elegant robes, surrounded by Herod and members of the royal court.

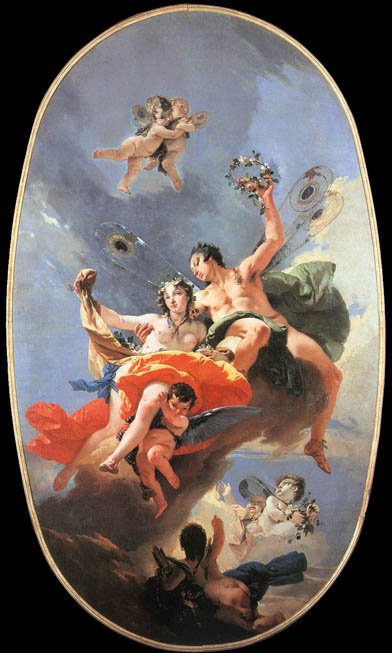

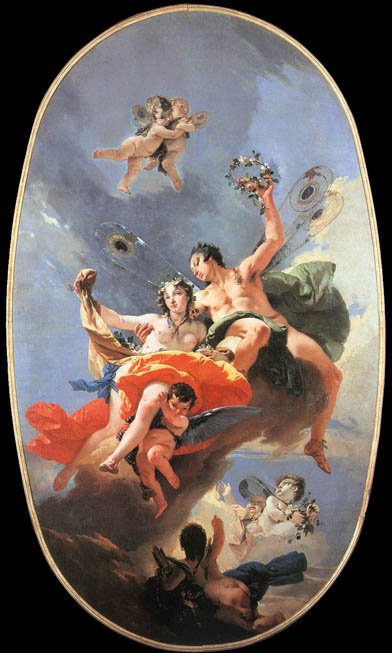

The Triumph of Zephyr and Flora: 1734-35

As an allegory of Spring, this picture brings together the god of the spring winds, Zephyr, and the goddess of all that blooms, Flora. Accompanied by several putti, they hover on a cloud in the sky, while on the lower edge of the picture, the god of love, Amor, seems to be showing them the way. The brilliant colorings of the robes, the successful modeling of the bodies and the dynamic depiction of the multicolored cloud formations, full of contrasts, make the picture one of Tiepolo's masterpieces.

Jupiter and Danae: 1736

Danaë is frequently represented in Renaissance and Baroque painting. You can view other depictions of Danae in the Web Gallery of Art.

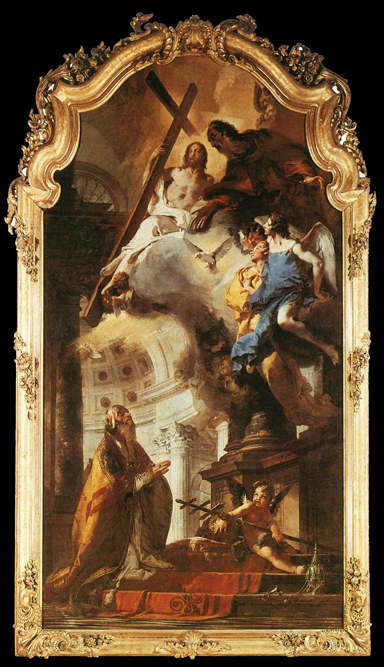

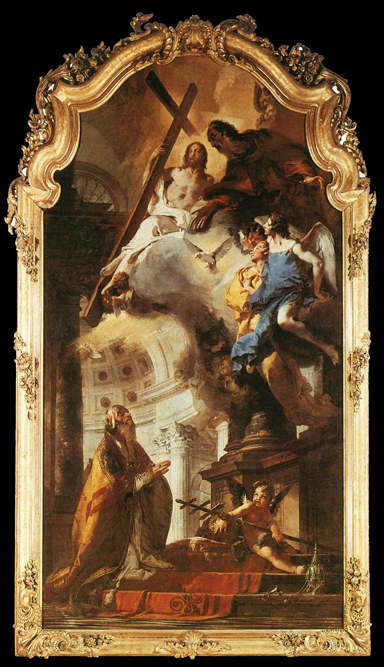

Pope Saint Clement Adoring the Trinity: 1737-38

The painting shows Pope Clement I at prayer, in an ecclesiastical architectural setting which cannot be identified more closely, before a vision of the Holy Trinity. The lively facial expressions suggest a conversation between Clement and God the Father, which is further dramatized by the strong chiaroscuro contrasts. In an allusion to the particular connection between the donor and his famous patron saint, Tiepolo lends the portrait of the Pope a private character: the tiara and crosier, symbols of his power, have been laid aside and placed in the keeping of a putto.

The Institution of the Rosary: 1737-39

The fresco is the largest version of this subject in European art, and it combines two different iconographic traditions: in the upper part of the picture, the Rosenkranzbild, in which Mary gives the Rosary to mankind, and, in the lower part, a depiction of the beneficence of the Rosary on earth, represented by Saint Dominic. As well as the Madonna of the Rosary, the fresco also extols Saint Dominic, the founder of the Dominican order, to whom the dog is a reference (lat. domini canes, God's hounds). All manner of people are portrayed - represented among others by the Doge, a Turk, a nun, and a mother and child, a symbol of Christian charity - so that the viewer, whether rich or poor, could identify with them.

Christ Carrying the Cross: 1737-38

The subject of the painting is Christ's carrying of the cross to the Hill of Golgotha, which rises up in the centre of the picture as a tall rock, the crosses already erected upon it. Directly beneath it in the foreground we see Christ in a flame red robe. He has collapsed under the heavy weight of the cross. To the right, Veronica, holding the sudarium, turns away from the dramatic scene, visibly moved. To the left, the two thieves likewise condemned to crucifixion are being led forward. In the exact centre of the picture, between Christ's cross and the hill of Golgotha, and directly facing the viewer, are the figures of Jesus' disciples, together with Mary and Mary Magdalene. Brightly illuminated, they stand out symbolically from the other figures.

Carrying the Cross: ca 1738

Eighteenth-century Venetian art, usually seen as more profane than sacred, was surprisingly inventive in terms of religious subject matter, none more so than that of Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, in both his etchings and paintings. This 'Carrying the Cross', panoramic in the greatest Venetian tradition, is a bozzetto for the central section of a Passion triptych for Sant'Alvise, Venice, completed ca. 1738.

The Madonna of Carmel and the Souls of the Purgatory: 1730's

The painting was formerly in a chapel in the church of Sant'Apollinare, Venice. After the suppression of the church, the picture was taken to France and cut in two. Both pieces were bought by the Chiesa family for the Brera, the painting was restored to its original form in 1950.

In this large painting, Tiepolo confronted the style of Piazzetta, and at the same time returned to elements of the great Venetian models of the Cinquecento, such as Veronese's Pala di San Zaccaria.

The Madonna of Carmel and the Souls of the Purgatory (Detail): 1730's

_1730_s.jpg)

The detail represents the central part of the painting.

An early work by Tiepolo, this painting is violent and agitated in its composition, construction of the figures, impastos and in the Baroque light effects. The influences on Tiepolo that can be discerned range from Balestra to Piazzetta. Veronese's example is seen in the broadness of the space and the juxtaposition of episodes. The painting shows one of the fundamentals of Tiepolo's spiritual approach: a skeptical, disenchanted detachment from his subject matter. This typical attitude of the Enlightenment later carried him to the supremely un-dramatic balance of his maturity, in which he returned, in more modern terms, to the sardonic ideal of Veronese.

Queen Zenobia before Emperor Aurelianus

Tiepolo treated this subject earlier, in one of the scenes in the frescoes of the Patriarchal Palace in Udine.

Abraham and the Three Angels

Tiepolo treated this subject earlier, in one of the scenes in the frescoes of the Patriarchal Palace in Udine.

Paintings in the 1740's

by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo

The Virgin with Six Saints: 1737-40

In Venetian Cinquecento paintings of the Madonna, the Virgin and Child are usually represented in a terrestrial environment, with a landscape background, in the company of saints. This type of "santa conversazione" was subsequently altered to suit the taste of the baroque era: in most instances the Virgin Mary, floating among clouds, appears to the saints situated in earthly regions. As in the Budapest canvas and in a number of other pictures by Tiepolo, the painter conveys a vision, an apparition, seeking to establish a connection between celestial and earthly elements.

Most likely the Budapest picture was painted for some pious brotherhood. Its airily receding architecture, the marvelous purity of its resplendent colors, the harmony of construction are similar to Tiepolo's works of the years 1737 to 1740, The Virgin with Six Saints was probably produced simultaneously with pictures in the church of Gesuati, and the lost Saint Augustine altarpiece of San Salvatore.

The Virgin Appearing to Saint Philip Neri: 1740

The saint stands in profile at the steps of an altar in front of a highly-developed architectural background. His gaze diverted upward in astonishment, he experiences the manifestation of the 'Mother of God and her Child', who appear to float in the interior of the church on a cloud, accompanied by angels. The rendering of the material of the robes is particularly impressive, as is the mist-like quality of the cloud, which almost turns the vision into an actual happening.

The Gathering of Manna: 1740-42

The altarpiece shows Moses standing on a rocky outcrop, with outspread arms, his gaze rose towards Heaven, which has already heard his prayers. An angel pours bread from a large vase down to earth, where the hungry Israelites scurry around on the ground to collect it. The strict division of the composition into two different areas - the spheres of heaven and earth - is broken by the figure of Moses, who is placed dead centre, and so is characterized as a mediator between the two spheres.

The Sacrifice of Melchizedek: 1740-42

The Sacrifice of Melchizedek is shown here as a pendant to the Gathering of Manna. The Priest-King of Salem brings Abraham bread and wine on the evening following the Battle of the Kings, and blesses him. Abraham, who kneels before him in armor, and the army to the right are a reminder of the battle which went before. To the left, we see the civilian population, including women, children and the elderly, while a triumphal procession is already approaching from behind the altar.

Allegory of Strength and Wisdom: 1740-43

This small canvas is a preparatory sketch for a bigger painting executed between 1740 and 1743 for the decoration of the ceiling of Palazzo Caiselli in Udine. (It is now conserved in the Museo Civico, Udine.) The artist later produced several copies for the ceilings of private palaces.

The Banquet of Cleopatra: 1743-44

Magnificent, brightly lit palace architecture is the setting for Cleopatra's banquet. However, the historical event of the meeting between the Queen of Egypt and the Roman Anthony takes second place to the creation of an opulent banqueting scene in the manner of Veronese. It is therefore the sumptuous costumes, the magnificent receptacles and the rich variety of foods which draw most attention as they are proffered by the servants of the court, who include Moors, a dwarf and a dog - a collection of elements typical of the work of Veronese.

Worshippers: 1743-45

Giambattista Tiepolo collaborated with the Venetian quadratura painter Girolamo Mengozzi Colonna on the ceiling fresco of the nave of the church of Saint Mary of Nazareth called the 'Scalzi', completing the work in 1743-45 following the careful preparation of studies and models. The grandiose fresco depicting the 'transportation of the holy house of Loreto' was almost completely destroyed during World War I. The few remaining fragments, such as this 'Worshippers', are enough to evoke the richness of color and conception of this major decorative achievement. The silver-white tones of the visionary shrine are illuminated by the dazzling hues of the garments of the nobleman who looks up towards the saintly apparition while his servant glances curiously downward towards the crowded nave.

Apollo and Daphne: 1744-45

The dramatic episode of Apollo and Daphne, as narrated by Ovid in the "Metamorphoses", is staged in front of an almost Alpine backdrop. Daphne escapes the attentions of Apollo, who has fallen madly in love with her, by turning herself into a tree. The moment in which the transformation begins is represented: Apollo is hard on her heels and Amor, too, is attempting to hold her, but her hands have already turned into foliage. The backward-facing figure of a river god in the foreground marks the end of her desperate flight. The strong contrast between the brilliant yellow and red robes and the dark blue shades of the background brings to mind works of French art.

Discovery of the True Cross: ca 1745

According to legend, Saint Helen, the mother of Constantine the Great, discovered the True Cross on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem. Tiepolo portrays the saint, in daring foreshortening from below, making a triumphal gesture in front of the Cross, which towers up into the sky. She is surrounded by the usual retinue of soldiers, holy men, the old and the young, women and children, commonly used by Tiepolo as extras in his paintings. A number of angels hover over the scene, carrying a thurible and a tablet bearing the name of Christ, looking down on the miracle of the discovery of the cross.

This grandiose tondo, originally the centerpiece of the ceiling decorated by Girolamo Mengozzi Colonna in the Capuchin church in Castello, is a typical example of Tiepolo's ability to translate any theme, sacred or profane into a stupendous Baroque magniloquence. Within the monumental order the areas of color are arranged in patterns of polychromatic splendor, suffused with a pure light which highlights every carefully observed detail. In this remarkable example of illusionistic perspective, with which Tiepolo never tired of amazing his contemporaries, the images are characterized by distinct notes of colors and emotion with a fascinating musical decorative freshness.

The Virgin Appearing to Dominican Saints: 1747-48

The Virgin Mary hovers on a throne-like golden yellow cloud beneath a baldachin in front of Renaissance architecture, dressed in brilliant reds and blues and accompanied by angels. In the foreground are the three saints, all members of the Dominican order. Agnes of Montepulciano (1274-1317) sits at the front and meditates over a small crucifix. Her robes illusionistically jut out into the viewer's space. To her left stands St Catherine of Siena (1347-1380) with a crown of thorns and a crucifix, and St Rose of Lima (1586-1617), holding the Christ Child in her arms.

The figures in this altarpiece are portrayed more as the heroines of noble dramas than as saints. They combine true pathos with elegant sensuality, as if they were creatures of some higher human species. At the same time, however, they are firmly linked to our sense of everyday life through the descriptive details which are so naturalistic as to border on trompe-l'oeil.

Last Communion of Saint Lucy: 1747-48

Still further proof of Tiepolo's extraordinarily eclectic talents comes from the fact that at the same period that he was working on the breathtakingly secular spectacle of the frescos in Palazzo Labia, he also painted his most religiously intense Venetian altarpiece. In no sense did he compromise the clear sobriety of the architecture nor the brilliance of his palette. Indeed they seem to underline the sadness of the scene.

With arms crossed, Saint Lucy kneels before a priest to receive the last communion. Her half closed eyes and the elegiac expression on her face hint at her later fate. The priests and secular dignitaries who surround her wear magnificent robes, whose beautifully rendered material and brilliant colors are of particular intensity. The scene takes place in front of an imposing palace, upon whose balustrade Tiepolo has again placed spectators. While the bloody knife and the platter with the gouged-out eyes in the foreground are a drastic reminder of the impending martyrdom, the heads of angels which hover over the saint announce her entry into the Kingdom of Heaven.

Saint James the Greater Conquering the Moors: 1749-50

Signed on the sword at the bottom: G. TIEPOLO F

Legend has it that the Apostle Saint James the Greater appeared to the Spaniards as they fought the Moors at the battle of Clavijo and that, with the help of this heavenly apparition, they achieved victory. Ever since that time the Apostle has been venerated by the Spanish people as their patron saint and his memory honored in numerous works of art. Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, perhaps the most significant of eighteenth-century painters, worked in Spain during the last years of his life, and it had been assumed that during those years he painted this picture - no doubt for an altarpiece. According to the latest research, however, the painting was commissioned by the Spanish Ambassador to London and executed in Venice in 1749-50; it is true that the Venetian chronicler mentions a picture of St George on horseback, but it is not unlikely that an Italian, unfamiliar with Spanish legend, may have misidentified the subject. Because of the monumental simplicity of its composition and its brilliant color harmony, this work must rank high in the annals of eighteenth-century painting.

Apparition of the Virgin to Saint Simon Stock: 1749

Tiepolo decorated the ceiling in the Scuola dei Carmini with the canvases 'Apparition of the Virgin to Saint Simon Stock', together with virtues and allegories.

Swathed in a full, dazzling light and supported by a sensual flight of angels, the Virgin Mary appears to Saint Simon, promising him eternal salvation in exchange for accepting the scapular, the gentle yoke of Christ.

Fortitude and Justice: 1743

Tiepolo decorated the ceiling in the Scuola dei Carmini with the canvases 'Apparition of the Virgin to Saint Simon Stock', together with virtues and allegories.

For this corner canvas Tiepolo took his inspiration from Veronese's work in the Sala del Collegio of the Palazzo Ducale. He brought his models up to date with more theatrical, relaxed poses and a use of color that exploits vibrant tones of light.

Prudence Sincerity and Temperance: 1743

Tiepolo decorated the ceiling in the Scuola dei Carmini with the canvases 'Apparition of the Virgin to St Simon Stock', together with virtues and allegories.

For this corner canvas Tiepolo took his inspiration from Veronese's work in the Sala del Collegio of the Palazzo Ducale. He brought his models up to date with more theatrical, relaxed poses and a use of color that exploits vibrant tones of light.

Neptune Offering Gifts to Venice: 1740's

This painting in the Sala delle Quattro Porte is one of the last public works commissioned by the Venetian Republic. As its thousand years of history drew to a close, the city commissioned this painting of Neptune pouring out the treasures of the sea and the riches of commerce before Venice. It was commissioned from Tiepolo to replace a lost painting by Tintoretto. The dating is controversial because of the painting's stylistic anomalies. In homage to the context, the work takes up motifs typical of the golden age of Venetian art.

Paintings between 1751 and 1770

by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo

Allegory of the Planets and Continents: 1752

Giovanni Battista Tiepolo was the most famous Italian painter of the 18th century. His greatest achievement was the decoration of two rooms in the palace, or Residenz, of Carl Philipp von Greiffenklau, Prince-Bishop of Wurzburg, carried out between 1751 and 1753. This painting is the oil sketch presented by Tiepolo on April 20, 1752, for the vast fresco over the staircase of the palace. It shows Apollo about to embark on his daily course across the sky; the deities around him symbolize the planets, and the allegorical figures on the cornice represent the four continents of the world. Numerous changes were made between the oil sketch and the fresco, but this painting shares with the completed ceiling the feeling for airy space, sun-washed colors, and the prodigious inventiveness for which Tiepolo is admired.

The Death of Hyacinth: 1752-53

In the foreground, accompanied by a putto, and with a sweeping gesture, Apollo laments Hyacinth, who he accidentally killed during a ball game, and whose body is impressively laid out on a red cloth. Behind them to the left, and somewhat distanced, is a group of onlookers included as staffage, while a grinning statue of Pan and a parrot, on the right, act as a third centre in the composition, their presence turning the tragedy of the scene to irony.

Adoration of the Magi: 1753

Tiepolo painted this altarpiece during his stay in Germany. Because if the damp climate, he could only work on the frescoes in the Wurzburg Residenz in the spring and summer. So in the fall and winter he had to concentrate on painting in oil on canvas. He produced some fantastic and exotically beautiful works in which the religious subject seems merely a pretext for eye-catching, showy images, but he himself was genuinely religious. The style of the age, however, meant that even religious topics often became theatrical.

An Allegory with Venus and Time: 1754-58

To enter fully the radiant world of Tiepolo we must travel - to Venice, his native city, then back to the mainland to Udine and Vicenza, across the Alps to Wurzburg in Bavaria, finally to Madrid in Spain where, fearing the shift of taste in his homeland, he elected to spend the last years of his life. The greatest decorative painter of his century, he was happiest working in fresco where his 'rapid and resolute' manner was a technical necessity. Under his virtuoso brush airy spaces, shimmering with light, opened on walls and ceilings to admit heroic beings - Christian, mythological, allegorical, historic or poetic - dazzling to mortal viewers. He has been called the last Renaissance painter, and borrowed much from Veronese. But Tiepolo, even more than Veronese, was never wholly serious when painting epic. He can be majestic but not solemn; poignant rather than tragic. In the century which discovered feminine sensibility, he introduced a note of tenderness into the sternest and loftiest imagery.

Luckily for us, something of the freshness of Tiepolo's mural decorations is preserved in his oil sketches and in this canvas, painted to be inserted into the ceiling of au with his quiver full of arrows. Venus has come to consign her newly born child, freshly washed with water from an earthenware amphora, to Father Time. Having set down his scythe, Time here signifies eternity rather than mortality. The child - wide-eyed, thick-lipped and with a precocious widow's peak in his hairline - resembles page boys frescoed by Tiepolo shortly before on the staircase of the prince-bishop's palace in Würzburg. He is clearly meant to be a real baby. Venus' only human child, born to a mortal father, was Aeneas the founder of Rome. The Contarini, one of the oldest families in Venice, had fabricated for themselves a lineage from ancient Rome; the reference to Aeneas thus suggests that the ceiling may have been commissioned to proclaim the birth of a son. Through august parentage and his own heroic deeds, a Contarini boy might be expected, like Aeneas, to win eternal fame.

A Seated Man and a Girl with a Pitcher: ca 1755

The painting belongs to a series of four paintings of identical size, all in the National Gallery, London.

The Theological Virtues: ca 1755

This is a study (modello) of a fresco above the choir of the Santa Maria della Pietà in Venice. The final fresco closely follows the modello with only minor changes.

Portrait of Daniele IV Dolfin: 1750's

Daniele Dolfin was a Procurator in Venice. This splendid portrait, still arranged in seventeenth-century modules, reveals a new sensitivity in its psychological insight. It is one of the finest examples of Tiepolo's shrewd, acute spirit of observation.

The Martyrdom of Saint Agatha: ca 1756

This picture was painted ca. 1756 for the high altar of the church of Saint Agatha in Lendinara. It must originally have been rounded at the top, for it appears in this form in an etching by Tiepolo's son, Giovanni Domenico. The part which is now missing showed a heart surrounded by the crown of thorns in a nimbus, at which the saint was gazing. The beautiful Agatha was a devout Christian who lived in Catania. She steadfastly refused to make sacrifice to the heathen gods. When she defied the threats of the Roman Governor of Sicily, Quintianus, he ordered her breasts to be cut off. We see her, half-naked, on a flight of steps; a maid kneels behind her, supporting her and holding her dress against the bleeding wounds. A page stands in front of a marble pillar, holding the severed breasts of the martyr on a silver platter and gazing down at her. The uncouth figure of the executioner clad in red and holding a blood-stained sword towers menacingly over the group.

Tiepolo is among the last of the great Venetian painters, a master of large-scale composition, who was commissioned by princes outside (Wurzburg, Madrid) as well as inside Italy. Nor did he shrink from this particularly horrifying subject; once before, twenty years earlier, he had been required to treat the same subject for the church of Saint Antonio in Padua. With astonishing self-assurance the painter succeeds in portraying this fearful episode in artistic terms without allowing it to degenerate into mere bloodshed and horror. At the same time, so strong is his desire for realism - and he had doubtless witnessed executions himself - that he exploits to the utmost the artistic possibilities open to him.

In color and form the composition is extremely accomplished, almost too much so to do justice to the theme. Between the soaring pillar and the towering figure of the executioner, one glimpses the dark entrance of the dungeon and beneath it the pale face of the martyr, flanked on both sides - almost oppressively close - by the faces of the two witnesses. The compassion expressed in the attitude of the young woman on the right contrasts with the searching glance of the page on the left, in which merely the physical effect of the scene before him is reflected. The wide, pale-blue cloak of the saint serves to bind the group of three figures together and blends with the silver-white, the bright yellow and the orange to produce a color-harmony that is characteristic of Tiepolo. Two of the artist's crayon studies for the saint's face are in the Kupferstichkabinett (Copper Engravings section) in the Berlin Museum.

Allegory of Merit Accompanied by Nobility and Virtue: 1757-58

The oval-shaped ceiling fresco shows the allegory of Merit on the left-hand side, personified by an elderly, bearded man wearing a laurel wreath. Accompanied by Nobility and the winged figure of Virtue, dressed in white, he rises up on a cloud populated by putti towards the temple of Glory. On the upper edge of the picture, Fame announces the glory of Merit by sounding her trumpets. The mostly empty skies in the centre of the fresco contain only clouds and several putti.

Rinaldo and Armida: 1755-60

Tiepolo illustrated in two horizontal paintings Tasso's Renaissance epic poem 'Gerusalemme Liberata'. The lovers Rinaldo and Almira are first seen in Armida's ravishing Palladian magical garden, then at Rinaldo's reluctant departure. These Mozartian paintings are either bozzetti or replicas in small format of the painter's large scenes of 1753 for the Episcopal Palace at Wurzburg.

Rinaldo's Departure from Armida: 1755-60

The Vision of Saint Anne: 1759

The Vision of Saint Anne was painted in 1759 for the church of Santa Chiara at the Benedictine monastery in Cividale, Friuli. The building can be made out in the small image in the background, together with the Santuario di Castelmonte and the old bridge over the River Natisone. The painting was removed from the church in 1810 and finally came to the Gemäldegalerie, Dresden in 1914 through auction.

In this strongly vertical composition, Tiepolo develops three distinct levels, one above the other: kneeling at the front is Saint Anne, who holds out her arms while gazing up to heaven; her husband, Joachim, who is shown behind a balustrade with his hands folded in prayer, looks in the same direction. Borne aloft on a cloud by angels, the young Mary is suspended above them. She too looks up to heaven and God the Father, who appears there leaning on the globe with his arms outstretched.