Italian Renaissance Painter and Draftsman

1480 - 1556

Lorenzo Lotto was a Northern Italian painter, draughtsman and illustrator, traditionally placed in the Venetian School. He painted mainly altarpieces, religious subjects and portraits. While he was active during the High Renaissance, he already constitutes, through his nervous and eccentric posing and distortions, a transitional stage to the first Florentine and Roman Mannerists of the 16th century.

Born in Venice, he worked in Treviso (1503-1506), the Marches (1506-1508), in Rome (1508-1510), Bergamo (1513-1525), in Venice (1525-1549), Ancona (1549) and finally as a Franciscan lay brother in Loreto (1549-1556).

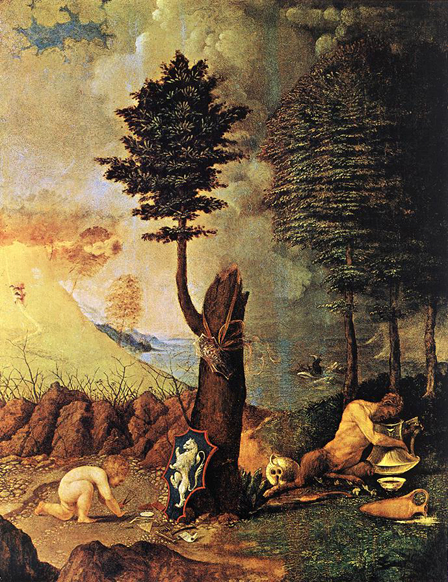

There is almost no information about his training. As a Venetian he was influenced by Giovanni Bellini as he had a good knowledge of contemporary Venetian painting. Though Bellini was doubtless not his teacher, the influence is clear in his early painting 'Virgin and Child with Saint Jerome' (1506). However, in his portraits and in his early painting 'Allegory of Virtue and Vice' (1505) he shows the influence of Giorgione's Naturalism. As he grew older his style changed, perhaps evolving, from a detached Giorgionesque classicism, to a more vibrant dramatic set piece, more reminiscent of his contemporary from Parma, Correggio.

The churchman's shield facing to the left signifies that during his life he chose the narrow path of learning and virtue symbolized by the child with instruments indicating learning. In contrast, on the right, are symbolized disaster and dissipation and vice in the shipwreck, storm, and wine-loving satyr.

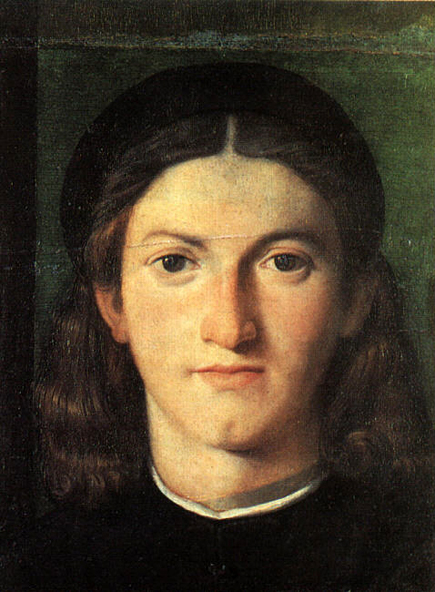

In the 18th-century inventories the painting appeared as the portrait of Raphael, executed by Leonardo da Vinci, an assumption based on the soft, atmospheric modeling, the intense psychological penetration, and the traditional iconography of Raphael, who had always been seen as a delicate, elegant and refined youth. Recent X-rays, however, have revealed a previous portrait, completely different the one executed.

Lotto soon left Venice. The competition for a young painter would have been too great with established names such as Giorgione, Palma il Vecchio and certainly with Titian. Nevertheless, Giorgio Vasari mentions in the third part of his book Vite that Lotto was a friend of Palma il Vecchio.

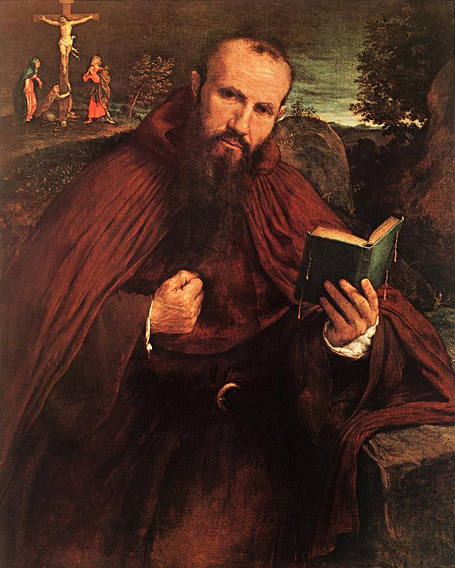

In Trevisio, a prospering town within the domain of the republic of Venice, he came under the patronage of Bishop Bernardino de'Rossi. The already mentioned painting 'Allegory of Virtue and Vice' was intended as an allegorical cover of his Portrait (1505) of the Bishop, who had survived an assassination attempt. The painting 'Saint Jerome in the Desert' (1500 or 1506) shows his youthful inexperience as a draughtsman, however the dramatic rocky landscape is accentuated by the red garment of the saint. At the same time he gives an early impression of his skill as a miniaturist.

He painted his first altarpieces for the parish church S Cristina al Tiverone (1505) and the baptistery of the Cathedral of Asolo (1506), both still on display in those churches.

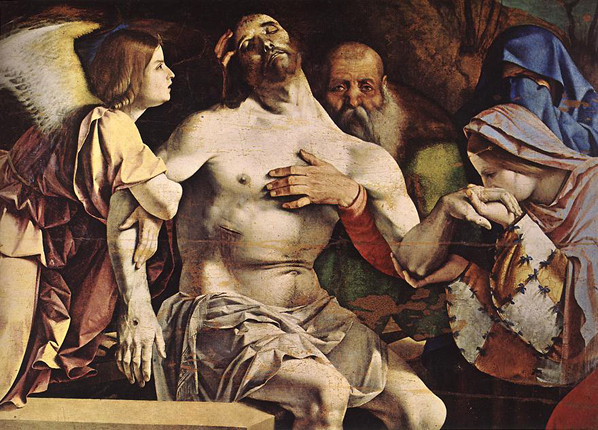

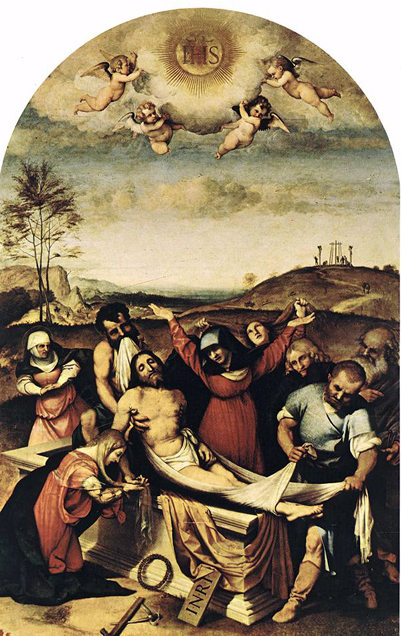

The lunetta represents the Dead Christ Surrounded by two Angels. The realism of this painting anticipates that of Caravaggio a century later.

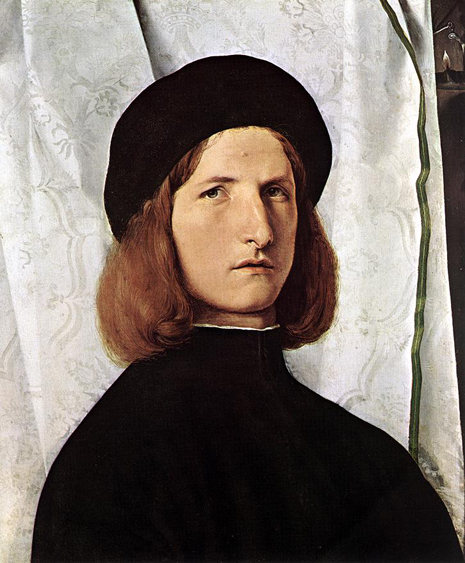

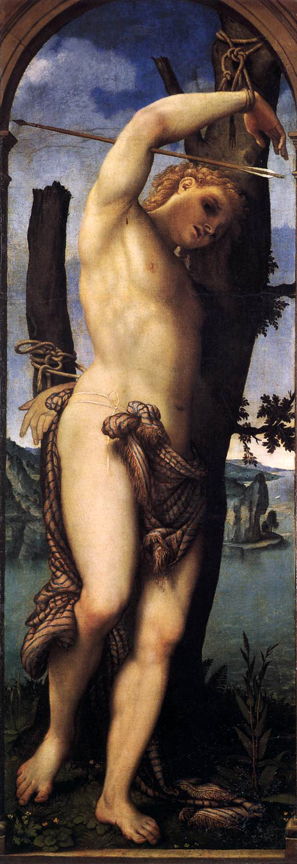

In 1508 he began the Recanati Polyptych Altarpiece for the church of Saint Domenico. This two-tiered, rather conventional painted polyptych consists of six panels. His 'Portrait Young Man against a White Curtain' (1508) is a famous painting from this period.

Lorenzo Lotto was probably trained in the Bellini workshop and his early works are strongly Bellinesque. This painting is an illustration of Lotto's early period. The picture is suffused with light, and in particular with light reflected from the vaulting of the loggia which shelters the group of Madonna and Child with attendant saints and angels from the brilliant sun outside.

_1508.jpg)

Reference to the "psychological" portrait here should not be understood in the modern sense of the epithet. The visual medium chosen by Lotto to portray mental states was less one of analytical disclosure than its opposite: enigma. His tendency to present the spectator with riddles was intensified by his mysterious symbolism, and by his frequent emblematical or hieroglyphic allusiveness. Although Lotto's allusions, in their literal sense, could be fathomed perhaps only by the "cognoscente" of his day, they are nevertheless capable of inspiring a wealth of vivid associative detail. This can be a source of fascination, as well as of frustration, to the spectator who has little access to their original meaning.

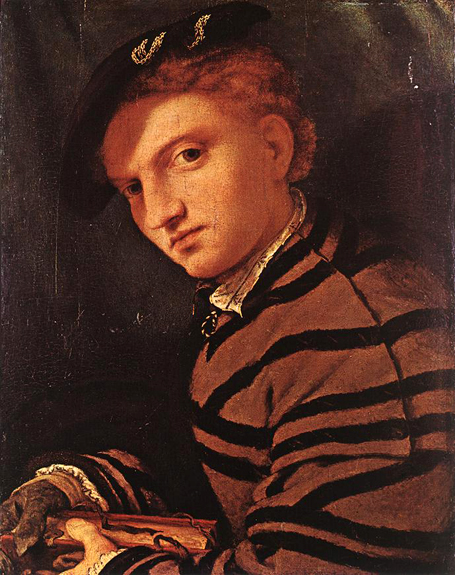

Lotto's early portrait of a young man wearing a round black beret and buttoned, black coat still owes much to the traditional aesthetic of imitation. Scholars have rightly pointed to the influence of Giovanni Bellini here. The physiognomy of his powerful nose and searching grey-brown eyes, which, under the slightly knitted brow, seem to brood on the spectator, to view him almost with suspicion, is so faithful a rendering of empirical detail that we are reminded of another painter, one whose brushwork was learned from the Netherlands' masters: Antonello da Messina. What is new here is the element of disquiet that has entered the composition along with the waves and folds of the white damask curtain. A breeze appears to have blown the curtain aside, and in the darkness, through a tiny wedge-shaped crack along the right edge of the painting, we see the barely noticeable flame of an oil-lamp.

Curtains are an important iconographical feature in Lotto's work. The motif is adopted from devotional painting, where it often provided a majestically symbolic backdrop for saints or other biblical figures. Since early Christian times, the curtain had been seen as a "velum", whose function was either to veil whatever was behind it, or, by an act of "re-velatio", or pulling aside of the curtain, to reveal it. To judge from the curtain which fills most of Lotto's canvas, we may safely conclude that he intends to reveal very little indeed of the "true nature" of his sitter. What he finally does reveal is done with such reserve and discretion as to be barely insinuated. For the burning lamp is undoubtedly an emblem of some kind. It may, in fact, be an allusion to the passage in St. John: "lux in tenebris" ('And the light shineth in darkness', John 1, 5). It is interesting to note that Isabella d'Este chose to cite this light/darkness metaphor in her own "impresa" in 1525, altering the original to refer to her isolation at the Mantuan court: "sufficit unum (lumen) in tenebris" (a single light suffices in the darkness). Perhaps Lotto intended to convey a similar message through his portrait of this young man.

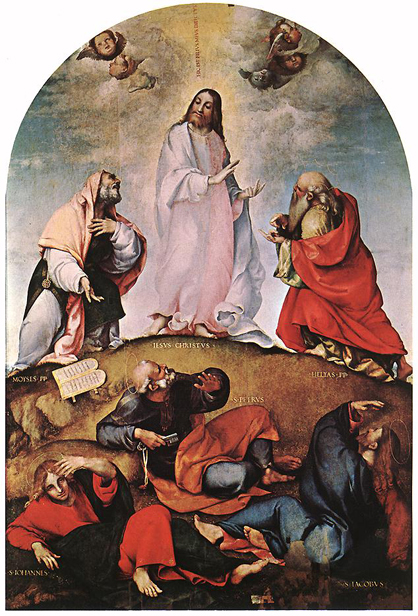

As he became a respected painter, he came to the attention of Bramante, the papal architect, who was passing through Loreto (a pilgrimage site near Recanati). Lorenzo Lotto was invited to Rome to decorate to papal apartments. Nothing however survives of his work, as they were destroyed a few years later. This was probably because he had imitated the style of Raphael, a rapidly rising star in the papal court. He had done this before in the 'Transfiguration' in the Recanati polyptych.

In 1511 he was at work for the confraternity of the Buon Gesu in Jesi, painting an 'Entombment'. Soon after, he was painting altarpieces in Recanati, a Transfiguration (1512?) and a fresco Saint Vincent Ferrer for the church San Domenico.

His work in Bergamo, the westernmost town of the Venetian Republic, and surrounding areas was to prove his best and most productive artistic period. He received many commissions from wealthy merchants, well-educated professionals and local aristocrats. He had become a rich colorist and an experienced draughtsman. He developed the concept of the psychological portrait, revealing the thoughts and emotions of his subjects. In this he was continuing the tradition started by Antonello da Messina. A good example is his Portrait of a 'Young Man with a Book'.

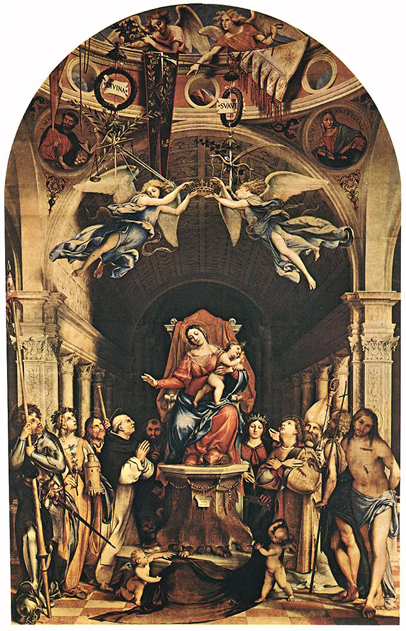

He started in 1513 with a monumental altarpiece Pala Martinengo in the Dominican church of Saint Stefano in Bergamo. This altarpiece was commissioned by Count Alessandro Martinengo-Coleoni, grandson of the famous condottiere Bartolomeo Colleoni. It would be finished in 1516. This altarpiece shows us the influence of Bramante and Giorgione. His next assignment was the decoration of the churches Saint Bernardino and Saint Alessandro in Colonna with frescoes and distemper paintings. He would finish five more altarpieces between 1521 and 1523.

The San Bartolomeo Altarpiece was commissioned in 1513 for the monastery of Saints Stephen and Dominic at Bergamo. It remained in the church until 1560 when the church was demolished. It was transferred to the Convent of Basella, then four years later to the church of San Bernardino. Finally, it was placed to the choir of the Dominican church of San Bartolomeo. In the 18th century it was dismembered, the main panel remained in the church, the other parts are dispersed.

The composition is characterized by its raised perspective and is divided in two by the brick wall, which seems almost to form a proscenium for the performance of a religious representation. The characters are arranged on the "stage" in dramatic poses, which, although perhaps somewhat strained and rhetorical, are undoubtedly effective.

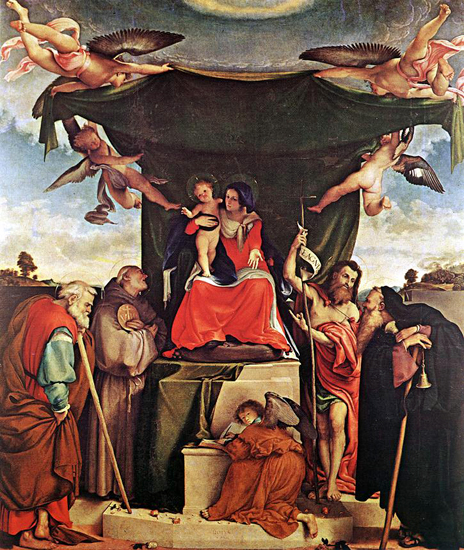

The charming open landscape gives the composition a delightfully archaic quality - quite intentional - which serves to balance the dramatic impact of the scene in the foreground.

In 1523 he went for a brief stay in the Marches, obtaining several commissions for altarpieces. He would paint these during his stay in Venice.

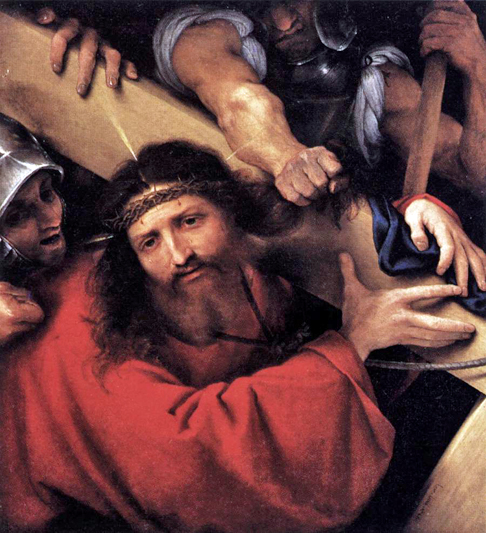

Lotto never accepted the material and secular values of painting in his native city of Venice and the Christ Taking Leave of his Mother shows how he used ambiguities of space and scale to heighten the religious and visionary effects of his paintings. At the same time he was capable of great intensity of observation, and his works often include passages of detail.

The represented saints are Joseph, Bernardino, John the Baptist, and Anthony Abbot.

_1521.jpg)

The painting echoes the circular compositions of Raphael, with a definitely Northern interpretation.

Lotto's three great altarpieces for churches in Bergamo, which were painted between 1516 and 1521, in the same periods as Titian's Assumption and Pesaro altar, are High Renaissance compositions, but closer, in their symmetrical arrangement, to Florentine painters like Fra Bartolommeo and Albertinelli, than to Titian himself. Yet for all the balance of their compositions, they remain restless in detail, and a passion for bright local color, and smooth hard surfaces prevents Lotto from achieving, or even aiming at, the painterly unity of his contemporaries. This failure to integrate perhaps reflects, at the deepest level, the tensions of a neurotic personality.

His next paintings are mostly wall paintings. In 1524 he painted a series of frescoes with the lives of saints (such as Saint Clare) in the Suardi chapel in Trescore (near Bergamo). In the details he depicts scenes of every life, such as in the fresco 'Martyrdom of Saint Claire. In the same fresco he portrays Christ with vines sprouting from his hands, illustrating the words of the New Testament: "I am the vine, you are the branches" (John 15-5).

In 1524 he also painted the cartoons with Old Testament stories as models for the intarsia panels for the choir stalls of S Maria Maggiore in Bergamo.

More than twenty private paintings date from the same period. They are mostly of religious and pious subjects such as Madonnas or a Deposition, used for worship at home. They are painted in the Classical tradition, but Lotto adds a personal touch to the intense emotions. Using contrasting poses and opposing movement, he breaks the traditional symmetry of the Virgin surrounded by angels and saints.

Lotto executed this painting in Bergamo for Marsilio Cassotti, signing it on the step of the throne in an inscription that reads "L. Aur Flus Lotus 1524". It was part of the collection housed at the Quirinal Palace, where it was noted by Cavalcaselle and Morelli, up until around 1912 when it passed to the Galleria Corsini. Within Lotto's career, this picture belongs to the last part of the period that he spent working in Bergamo. A direct comparison can be made with the almost contemporary Marriage at the Accademia Carrara in Bergamo, a picture signed and dated to 1523. In both works Lotto attains a compositional equilibrium through the interlinking of the figures. In the National Gallery picture, the circular motion around the fulcrum of the Madonna is also underscored by seemingly improvisational light reflections which form a pattern of diffusion that centers on the figure of the Virgin.

The medallion hanging from Saint Catherine's belt is typical of Lotto's world of emblematic symbols. Its winged putto is a recurring motif in the artist's work. Lotto employed a similar putto in his 1525 inlay designs for the steps of the choir entrance at Santa Maria Maggiore in Bergamo, accompanied by the motto "Nosce te ipsum". The motif and motto appear again in Lotto's portrait of an anonymous Thirty-seven year old man (Doria-Pamphili Gallery, Rome), though without the same degree of detail evident in the Palazzo Barberini Mystic Marriage. The theme of wisdom and justice, symbolically communicated by the putto with his feet resting on a balance, is well adapted to this learned saint. Catherine is also portrayed with a richness of clothing and jewels which, though normal to her iconography, are distinctive in the refined attention with which the artist treats them. Lotto generally requested additional compensation for such intricate work.

The figures of the Saints mark one of the high points of Lotto's career. The meanings and possible interpretations are extremely complicated and also include references to the Protestant Reformation and alchemy. However, the two longer walls are dedicated to the narration of the legends relating to the two Saints. While the stories of Saint Bridget interrupted by the door and windows, the complex account of the martyrdom of Saint Barbara is continuous, with the important points being underlined by the presence of architecture.

Lotto first stayed at the Dominican monastery of SS Giovanni e Paolo. But he had to leave after a few months after a conflict with Friar Damiano Zambelli, the intaglia artist. To cope with the many commissions, he founded a workshop. He shipped five altarpieces for churches in the Marches and another one for the church Saint Maria Assunta in Celano (near Bergamo). Another altarpiece was for the Venetian church of Saint Maria dei Carmini, portraying St. Nicholas of Bari in Glory.

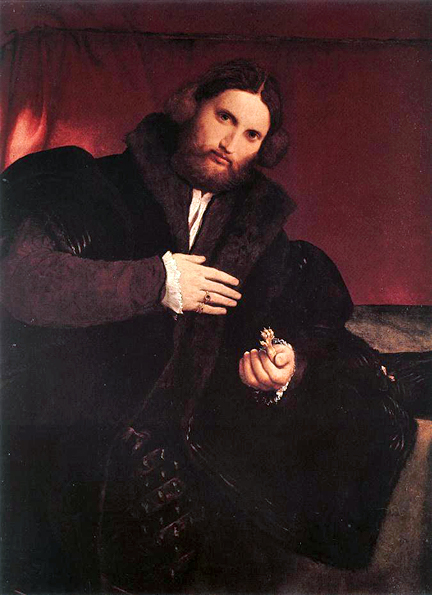

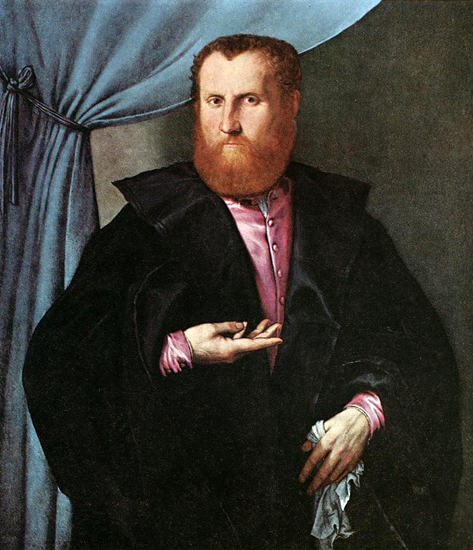

As Venice was a city of great wealth and as popularity increased, he received many orders for private paintings, including ten portraits, including Portrait of a 'Young Man'. His portrait of 'Andrea Odoni' (1527) would later influence the portrait of Jacopo Strada by Titian (1568) (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna). But in Venice he was overshadowed by his rival Titian, who dominated the artistic scene. Lorenzo Lotto left Venice in 1532 to Treviso.

The painting was executed for the Oratory of Santa Maria sopra Mercanti, where it remained until 1953, when it was transferred to the museum.

It is not unthinkable that the paw, or claw, may be an obscure reference to some Latin phrase which, in this context, would have the force of a motto. The motto might be "ex ungue leonem" (to recognize "the lion by its paw"), a synecdoche employed by Classical writers, for example Plutarch and Lucian, to refer - by metonymy - to a painter's brushwork or signature, or "hand" in sculpture, which immediately identifies the work of a particular master. This interpretation of the paw would, of course, be in keeping with the suggestion that it represents a professional attribute.

A conclusive interpretation of this painting is not possible. The historical and aesthetic conditions of the painting's conception and execution evidently precluded access to its meanings by more than a limited circle of Lotto's contemporaries, a problem that makes the painting virtually impossible to decipher today. The precept of "dissimulatio", the demand - frequently voiced in the increasingly popular moralizing literature of the day - that the sitter's inward world remain concealed, or veiled, seems to have influenced its conception. The painting shows a new page turning in the history of the mind, a new stage of awareness of subjectivity and individuality. Here was a dialectical response to a feeling that the self had become all too transparent, all too vulnerable, an example of the new tactics required by the self-assertive individual in contemporary social hierarchies.

_ca_1527.jpg)

The pale young man with his finely tapered face is obviously a lover of both music and hunting witness the mandola and the hunting horn hanging from the piece of furniture on the right, and is caught here in a moment of yearning thoughtfulness as his fingers leaf absent-mindedly through the pages of a large book. The natural light, entering through an invisible window, highlights the vibrant blacks and grays of his garments, the pale pink tones of his flesh and the blues of the table and just manages to penetrate the dark of the background in subdued illumination of the objects there, the finely turned ink-stand and the keys on the sideboard. The human figure too with its lack of any strong emotion, seems to participate in the arcane calm of this stupendous still life, the recently opened letter, the slow dropping of the rose petals, the silk shawl from whose folds darts a lizard. Such searching after human truth, veiled with melancholy, is at quite the opposite pole from the dignified idealization pursued by Titian in the portraits he painted at about the same time.

Classical Antiquity seems revived in the form of a huge head emerging from under the table-cloth. In fact, this is the head of Emperor Hadrian, the "Adrian de stucco" mentioned by Marcantonio Michiel in 1555 in his Odoni-collection inventory. The much smaller torso of Venus appears to nestle up to the head, to - probably calculated - comic effect. Although monochromatic, and indeed partly ruined, the sculptures seem mysteriously animated. Lotto invokes the magical properties of the image; he gently parodies the theme of the "re-birth" of Classical art by taking it literally.

The small statue in the collector's hand, reminiscent of Diana of Ephesus, indicates the artist's and sitter's demonstrable interest in Egyptian religion. At Venice, Lorenzo Lotto's place of birth, where he often stayed - the painting was executed after 1526, while Lotto was staying at Venice - there was widespread interest among the humanists in Egyptian hieroglyphics as a source of arcane knowledge and divine wisdom. This "science" could be traced back to Horapollo, the author of a treatise on hieroglyphics, which had survived in Greek translation.

_1527.jpg)

The represented Saints are Catherine of Alexandria and James the Greater.

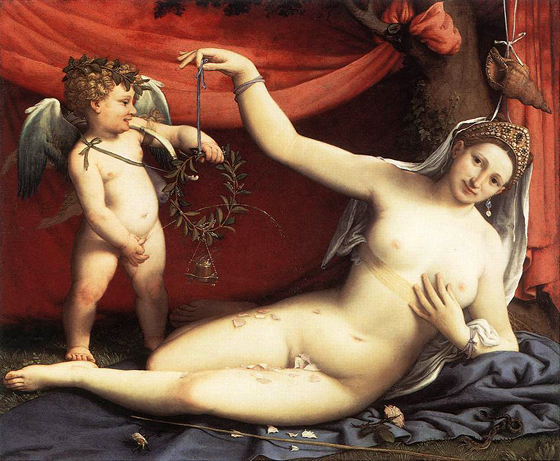

In the 16th and 17th century Lucretia was frequently portrayed as a symbol of purity. Lotto presents us with the three-quarter view of a woman dressed in fine, richly trimmed clothes. Turned slightly away from the viewer, in her left hand she holds a drawing of the naked Lucretia about to stab herself in the heart. An inscription in Latin on the sheet on the table reads: "Following Lucretia's example, no dishonored woman should continue to live".

In the exquisiteness of its palette, the painting ranks amongst Lotto's greatest works. While the subject's face follows on from the tradition of Giorgione, the contrast between her brightly lit shoulders and the richly gradated reds and greens of her dress is worthy of a Titian. The costly pendant suspended from the gold chain, its precious stones refracting the light, is virtually without equal in 16th-century Venetian painting.

In this last period of his life, Lorenzo Lotto would frequently move from town to town, searching for patrons and commissions. In 1532 he went to Treviso. Next he spent about seven years in the Marches (Ancona, Macerata en Jesi), returning to Venice in 1540. He moved again to Treviso in 1542 and back to Venice in 1545. Finally he went back to Ancona in 1549.

The altarpiece was commissioned by the Confraternity of Santa Lucia of Iesi in 1523; however, the execution started only in 1528 and ended only in 1532. The altarpiece was placed in the church of Saint Florian at Iesi, and it was transferred to the museum in 1861.

According to the tradition, the donator was Sperandia Franceschini Simonetti, the wife of Dario Franceschini, Lotto's friend at Cingoli. It is not known whether Lotto executed the painting in the Marche where he stayed in November 1538, or in Venice where he is documented in January 1540.

Rather than painting monarchs and prelates, as did Titian, Lotto portrayed the local nobility, fixing their traits with an acute eye. There is no rhetorical decorative detail but only the existential truth of the subject.

The handling of the paint, especially in the Portrait of Laura da Pola, is Titianesque in the brushwork, the broad and uneven strokes and the warm tonality. The register is kept predominantly low, however, and is almost monotonous in the costume and the background, except for the warm rays of the velvet chair and the explosive color of the fan. The abstract oval of the face, framed by the regular coiffure and headdress, is reminiscent of the Tuscan tradition.

At the end of his life it was becoming increasingly difficult for him to earn a living. Furthermore, in 1550 one of his works had an unsuccessful auction in Ancona. As recorded in his personal account book, this deeply disillusioned him. As he had always been a deeply religious man, he entered in 1552 the Holy Sanctuary at Loreto, becoming a lay brother. During that time he decorated the basilica of S Maria and painted a Presentation in the Temple for the Palazzo Apostolico in Loreto. He died in 1556 and was buried, at his request, in a Dominican habit. Giorgio Vasari included Lotto's biography in the third volume of his book Vite. Lorenzo Lotto himself left many letters and a detailed notebook (Libro di spese diverse, 1538-1556), giving a certain insight in his life and work. Among the many painters he influenced are likely Giovanni Busi.

During his lifetime, Lorenzo Lotto was a well-respected painter and certainly popular in Northern Italy. He is traditionally included in the Venetian School, but his independent career actually places him outside the Venetian art scene. He was certainly not as highly regarded in Venice as in the other towns where he worked. He had an own stylistic individuality, even an idiosyncratic style. After his death, he gradually became neglected and then almost forgotten. This could be attributed to the fact that his oeuvre now remains in lesser known churches or in provincial musea. Even the top musea of the world possess each only a few of his paintings.

Source: Art Renewal Center

Source: Web Gallery of Art

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.