Italian Early Renaissance Painter and Musician

1430 - 1516

Giovanni Bellini was an Italian Renaissance painter, probably the best known of the Bellini family of Venetian painters. His father was Jacopo Bellini, his brother was Gentile Bellini, and his brother-in-law was Andrea Mantegna. He is considered to have revolutionized Venetian painting, moving it towards a more sensuous and coloristic style. Through the use of clear, slow-drying oil paints, Giovanni created deep, rich tints and detailed shadings. His sumptuous coloring and fluent, atmospheric landscapes had a great effect on the Venetian painting school, especially on his pupils Giorgione and Titian.

The painting is signed and dated: " Joannes Bellinus / faciebat M.D.X.V."

We witness in this late canvas the incredible openness that the almost ninety year-old artist succeeded in advancing in his affirmation of a new profane sensibility.

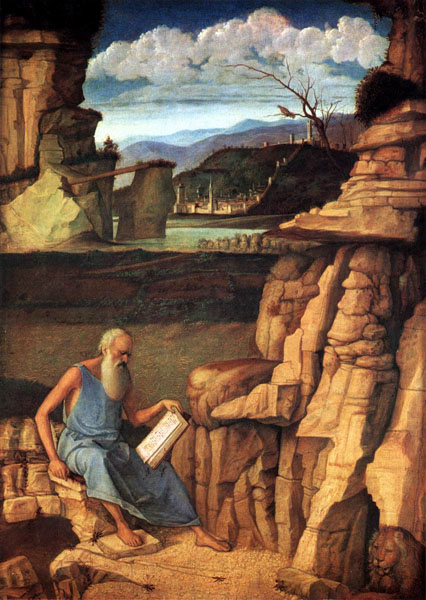

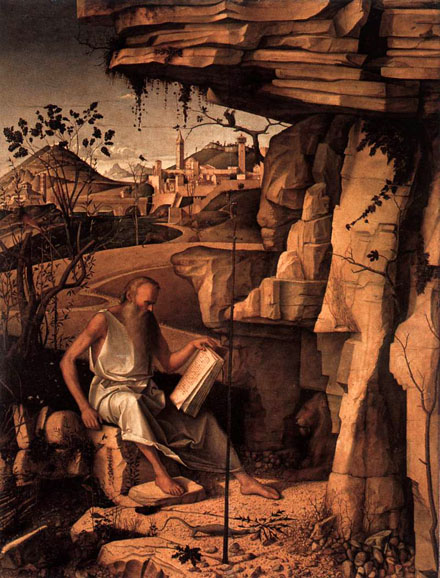

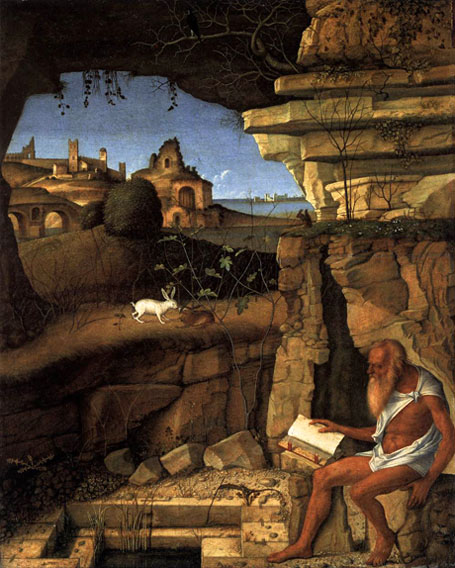

Giovanni Bellini was probably born in Venice. He was brought up in his father's house, and always lived and worked in the closest fraternal relation with his brother Gentile. Up until the age of nearly thirty we find in his work a depth of religious feeling and human pathos which is his own. His paintings from the early period are all executed in the old tempera method; the scene is softened by a new and beautiful effect of romantic sunrise color (see for example, the Saint Jerome).

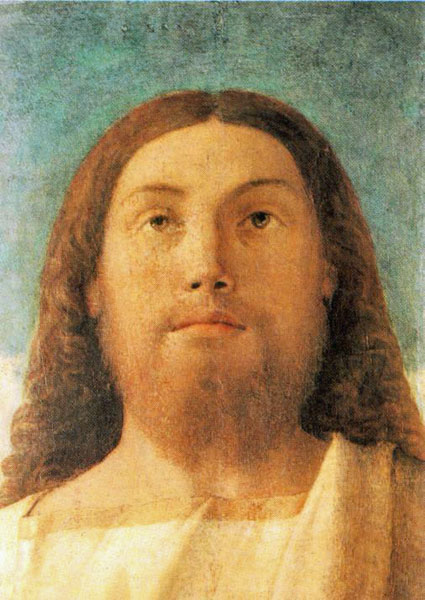

The painting is signed on cartellino: IHOVANES BELINUS.

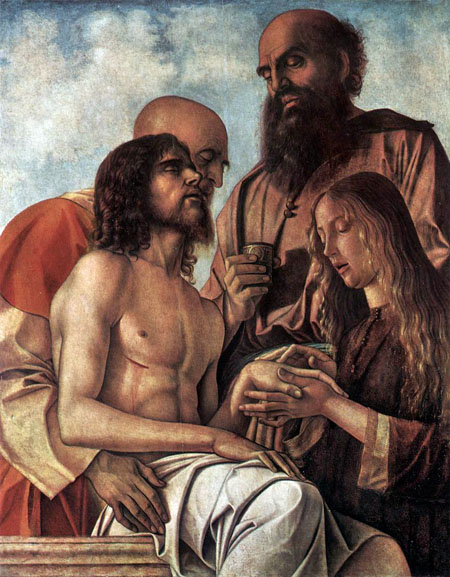

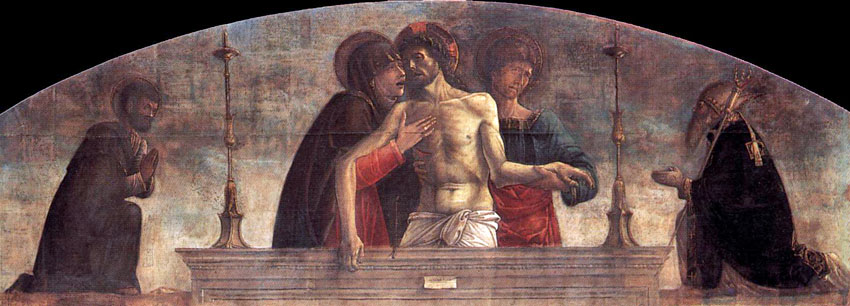

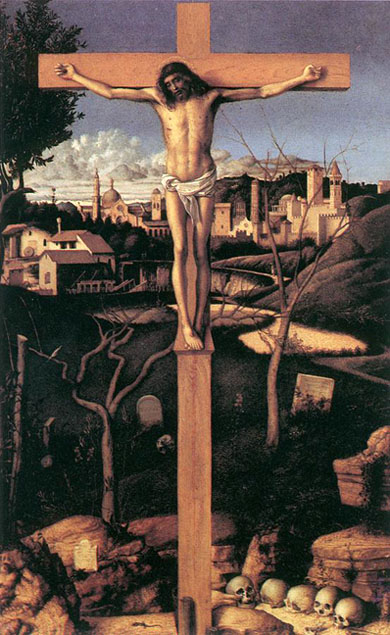

In a somewhat changed and more personal manner, with less harshness of contour and a broader treatment of forms and draperies, but not less force of religious feeling, are the Dead Christ pictures, in these days one of the master's most frequent themes, (For example the Pietà: Dead Christ Supported by the Virgin and St. John). Giovanni's early works have often been linked both compositionally and stylistically to those of his brother-in-law, Andrea Mantegna.

_1460.jpg)

The Pietà is rightly considered one of the most moving paintings in the history of art. Deep feeling is expressed throughout, from the landscape that recalls Flemish antecedents to the lucid architectonic composition of the group and the abstract geometry of their movements, deriving from Piero della Francesca. A passionate feeling that is not so much religious as human and psychological pervades the actors in the drama. The rendering of grief has here its most universal expression and, at the same time, its most private and conscious dimension. The mother's pathetic gesture is reflected in Saint John's turning away. The construction of the work shows careful thought. The figures, borrowed from popular imagery, are grouped in the foreground against an infinite horizon. The pentagonal arm of Christ ending in a closed fist is that of a fallen but unvanquished athlete. The barely glimpsed landscape, with its road wandering up a height and its torrent coursing below, pulsates with earthly life.

The figures stand out against a leaden dreamlike sky. The painting retains a strong Paduan element that is evident in the contours, adjusting gestures and figures to the strong expressive requirements of the drama. The silent exchange of emotions in the faces is reflected in the masterly play of the hands. The landscape behind them, empty and metallic in the cold, shining grays of the painful dawn of rebirth, accentuates the sense of the scene's anguish. Both the Donatello of the altar of Saint Anthony of Padua and, once again, Mantegna and the Flemish masters are the influences which spurred Bellini along the path of a sad and bitter pathos.

In 1470 Giovanni's received his first appointment to work along with his brother and other artists in the Scuola di San Marco, where among other subjects he was commissioned to paint a Deluge with Noah's Ark. None of the master's works of this kind, whether painted for the various schools or confraternities or for the ducal palace, have survived.

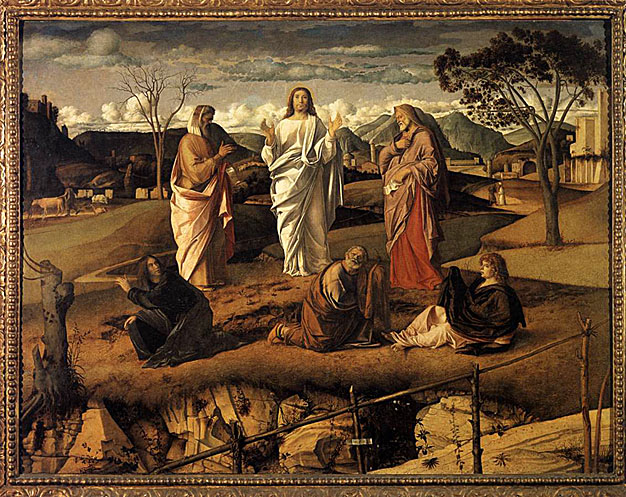

To the decade following 1470 must probably be assigned the Transfiguration now in the Naples museum, repeating with greatly ripened powers and in a much serener spirit the subject of his early effort at Venice.

Also the great altar-piece of the Coronation of the Virgin at Pesaro, which would seem to be his earliest effort in a form of art previously almost monopolized in Venice by the rival school of the Vivarini.

The Pesaro Altarpiece was executed for the church of San Francesco in Pesaro. 'Coronation of the Virgin' remained in the church at the time of its dissolution in 1797, then became the property of the Commune, and after various vicissitudes ended up at the Musei Civici in Pesaro, where it is now. The 'Pietà', which according to customary canons of the time crowned it, at the time of the church's dissolution, went to Paris; it was recovered and brought to Rome by Canova in 1815; it finally came to the Vatican Pinacoteca.

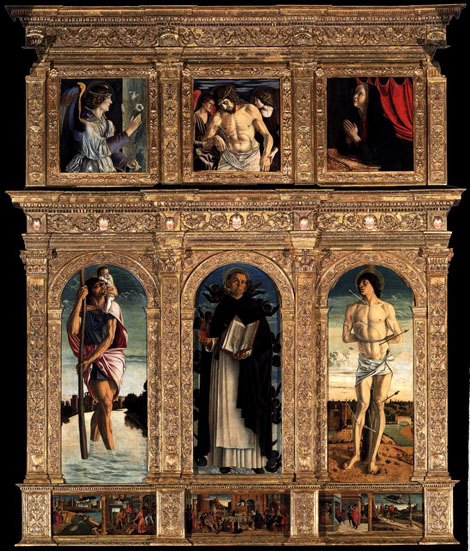

The altarpiece celebrates the profession of Franciscan faith (an Order linked to the Sforza Family, then Lords of Pesaro, by strong bonds of devotion and protection) through the presence, at the sides of the throne and in the left and right-hand pilasters, of saints whose cult was particularly venerated and fostered by the friars in Pesaro.

The altarpiece certainly has a politico-religious value which is impressed in and in some way determines the composition. On the one hand it celebrates the profession of Franciscan faith (an Order linked to the Sforza family, then lords of Pesaro, by strong bonds of devotion and protection) through the presence, at the sides of the throne and in the left and right-hand pilasters, of saints whose cult was particularly venerated and fostered by the friars in Pesaro and in the territory of the signoria. But, on the other hand, they are particularly significant by virtue of a symbolic meaning attributed to their presence: George, the knightly saint so dear to the noble courts, and Terence, saint of Pesaro represented as an ancient "miles", occupy the compartments at the base of the pilasters, where heraldic insignia were usually placed, and thus represent the civil and military power of the Sforza. Behind Terence, on the left, a Roman memorial tablet with a bust and an inscription extolling the emperor Augustus completes the celebratory reference to the 'potestas' of the ducal family.

The occasion for the execution of the altarpiece is also a matter of uncertainty and controversy. It might have been ordered to celebrate the taking of Gradara, the Riminese fortress conquered by Pesaro in 1463: the many-towered and fortified landscape in the background of the Coronation would in this case refer to the representation of Gradara. Alternatively, we might consider the marriage between the lord of Pesaro and Camilla of Aragon in 1474.

Stylistically, the Pesaro Altarpiece marks the achievement of a new balance. The lesson of Mantegna appears to have been sublimated in the light of that of Piero della Francesca, thus opening the way to yet another issue: where and when, in other words, had Bellini been able to contemplate and become so well acquainted with the art of Piero della Francesca. Probably the Pesaro Altarpiece itself constituted for him the occasion of a journey from Venice to the Marches, which was among other things his mother's birthplace, and therefore the possibility of a direct appreciation of the works of Piero della Francesca.

The typically Venetian architecture of the altarpiece recalls that of some contemporary funerary monuments, primarily that of the Doge Pasquale Malipiero, erected by Pietro Lombardo in the church of Saint John and Saint Paul. However, the typology of a frame that is integral with the painting, in the interests of an inseparable perspective and spatial continuity, is fundamentally new (even if it drew on various precedents, such as Mantegna's San Zeno Polyptych). The idea of the throne's open back-piece, a veritable painting within a painting, serves precisely to resume and further articulate this new structural and compositional definition. In the great altarpiece that followed, that of San Giobbe (ca. 1487) and in the altarpieces to come this intuition would develop and mature until it reached a total, and also optical, indivisibility of the painting from its frame, which constitutes the only real access to it, the starting point of the vision itself.

The 'Pietà' is a sublime artistic object in itself. It seems to have concentrated a deeply-felt knowledge of the divine sacrifice. The choral silence of the three figures around Christ, their contemplative meditation, and the play of their interlocking hands, render its sacramental sense of sublime communion.

_1471_74.jpg)

George, the knightly saint so dear to the noble courts, and Terence, saint of Pesaro represented as an ancient "miles", occupy the compartments at the base of the pilasters, where heraldic insignia were usually placed, and thus represent the civil and military power of the Sforza. Behind Terence, on the left, a Roman memorial tablet with a bust and an inscription extolling the Emperor Augustus completes the celebratory reference to the 'potestas' of the ducal family.

_Two_1471_74.jpg)

_Four_1471_74.jpg)

_Three.jpg)

George, the Knightly Saint so dear to the noble courts, and Terence, Saint of Pesaro represented as an ancient "miles", occupy the compartments at the base of the pilasters, where heraldic insignia were usually placed, and thus represent the civil and military power of the Sforza. Behind Terence, on the left, a Roman memorial tablet with a bust and an inscription extolling the Emperor Augustus completes the celebratory reference to the 'potestas' of the ducal family. A widely accepted assumption is that the fortress model in the hands of Saint Terence is the Fortezza Costanza, designed by Laurana for Costanzo Sforza, lord of Pesaro.

As is the case with a number of his brother, Gentile's public works of the period, many of Giovanni's great public works are now lost. The still more famous altar-piece painted in tempera for a chapel in the Church of S. Giovanni e Paolo, where it perished along with Titian's Peter Martyr and Tintoretto's Crucifixion in the disastrous fire of 1867.

Too, after 1479-1480 much of Giovanni's time and energy must have been taken up by his duties as conservator of the paintings in the great hall of the ducal palace. The importance of this commission can be measured by the payment Giovanni received: he was awarded, first the reversion of a broker's place in the Fondaco dei Tedeschi, and afterwards, as a substitute, a fixed annual pension of eighty ducats. Besides repairing and renewing the works of his predecessors he was commissioned to paint a number of new subjects, six or seven in all, in further illustration of the part played by Venice in the wars of Frederick Barbarossa and the pope. These works, executed with much interruption and delay, were the object of universal admiration while they lasted, but not a trace of them survived the fire of 1577; neither have any other examples of his historical and processional compositions come down, enabling us to compare his manner in such subjects with that of his brother Gentile.

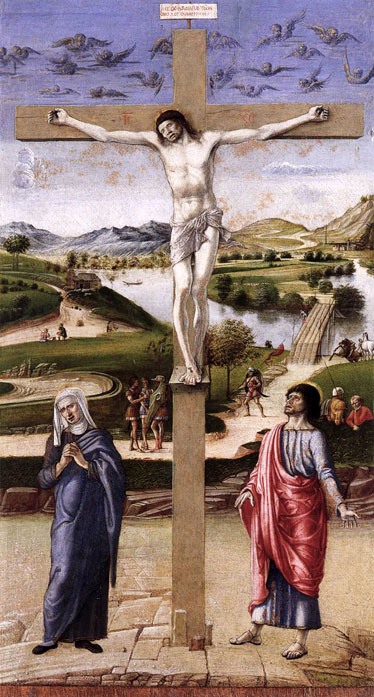

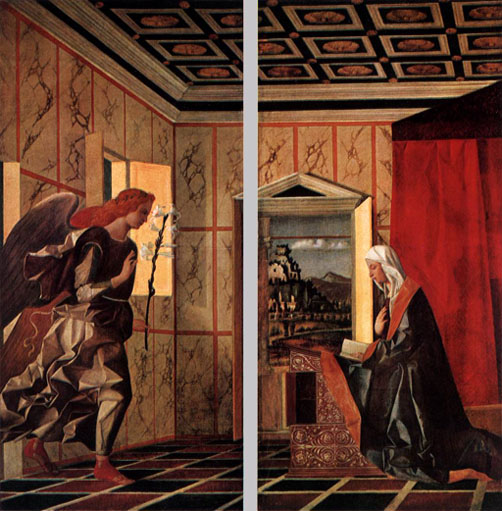

Of the other, the religious class of his work including both altar-pieces with many figures and simple Madonnas a considerable number have fortunately been preserved. They show him gradually throwing off the last restraints of the Quattrocento manner; gradually acquiring a complete mastery of the new oil medium introduced in Venice by Antonello da Messina about 1473, and mastering with its help all, or nearly all, the secrets of the perfect fusion of colors and atmospheric gradation of tones. The old intensity of pathetic and devout feeling gradually fades away and gives place to a noble, if more worldly, serenity and charm. The enthroned Virgin and Child become tranquil and commanding in their sweetness; the personages of the attendant saints gain in power, presence and individuality; enchanting groups of singing and viol-playing angels symbolize and complete the harmony of the scene. The full splendor of Venetian color invests alike the figures, their architectural framework, the landscape and the sky.

An interval of some years, no doubt chiefly occupied with work in the Hall of the Great Council, seems to separate the San Giobbe Altarpiece, and that of the church of San Zaccaria at Venice. Formally, the works are very similar, so a comparison between serves to illustrate the shift in Bellini's work over the last decade of the Quattrocento. Both pictures are of the Sacra conversazione (sacred conversation between the Madonna and Saints) type. Both show the Madonna seated on a throne (thought to allude to the throne of Solomon), between classicizing columns. Both place the holy figures beneath a golden mosaic half dome that recalls the Byzantine architecture in the church of San Marco.

This altarpiece representing the Madonna with the Child, Saints and Angels was executed for the church of San Giobbe in Venice, originally over the second altar on the right of the church, completing, in an illusory way, with its own spatiality, the Lombardian architectural plan. When it appeared, it immediately became one of Bellini's most celebrated works. The dating is uncertain, however, it is assumed that this was the first altarpiece by Bellini painted with the new oil technique introduced by Antonello da Messina in Venice in 1475-76.

In it, the figures are arranged with monumentality and human warmth; the modeling is softened by the redefined blending of colors, which reflects dim crepuscular lights from the apsidal basin, depicted like a gold mosaic according to a visual and chromatic tradition associated with the basilica mosaics of San Marco.

This altarpiece was executed by the seventy-five-years-old Bellini for the church of San Zaccaria in Venice. The altarpiece, commissioned in memory of Pietro Cappello, was already in its own time "considered one of the most beautiful and refined works of the master" (Ridolfi, 1648). The compositional and architectural structure of the canvas is not fundamentally very different from the San Giobbe Altarpiece: a niche-like apse surrounding the group of the enthroned Madonna and the saints who are positioned at her sides. However, many Madonnas with saints have been painted before and after, in Italy and elsewhere, but few were ever conceived with such dignity and repose.

The composition of the altarpiece is governed by a rigorous symmetry that highlights connections and contrasts in meaning: Saint Peter has his usual attributes, the keys of power and the closed book of acquired wisdom; Saint Jerome is deep in an open book, endless study still before him; Catherine and Lucy, sister like, are two demure, wise virgins, each with the same palm and the specific emblems of her martyrdom, a section of wheel in Catherine's case and Lucy's small bowl with her eyes. All the figures are arranged around the direct revelation of the mystery: the incarnation, passion, death, and resurrection of Christ. The story begins with angelic music, reaches its climax in the exhibition of the Child in the arms of Mary, seated on the throne of Solomon, and is recapitulated in the mosaic, which features the early Christian symbols of the evergreen acanthus and the eagle of glory.

In the later work he depicts the Virgin surrounded by: St. Peter holding his keys and the Book of Wisdom; the virginal St. Catherine and St. Lucy closest to the Virgin, each holding a martyr's palm and her implement of torture St. Jerome, who translated the Greek Bible into the first Latin edition (the Vulgate).

Stylistically, the lighting in the San Zaccaria piece has become so soft and diffuse that it makes that in the San Giobbe appear almost raking in contrast. Giovanni's use of the oil medium had matured, and the holy figures seem to be swathed in a still, rarefied air. The San Zaccaria is considered perhaps the most beautiful and imposing of all Giovanni's altarpieces, and is dated 1505, the year following that of Giorgione's Madonna of Castelfranco.

Other late altar-piece with saints includes that of the church of San Francesco della Vigna at Venice, 1507; that of La Corona at Vicenza, a Baptism of Christ in a landscape, 1510; and that of San Giovanni Crisostomo at Venice of 1513.

Of Giovanni's activity in the interval between the altar-pieces of San Giobbe and San Zaccaria, there are a few minor works left, though the great mass of his output perished with the fire of the Doge's Palace in 1577. The last ten or twelve years of the master's life saw him besieged with more commissions than he could well complete. Already in the years 1501-1504 the marchioness Isabella Gonzaga of Mantua had had great difficulty in obtaining delivery from him of a picture of the Madonna and Saints (now lost) for which part payment had been made in advance. In 1505 she endeavored through Cardinal Bembo to obtain from him another picture, this time of a secular or mythological character. What the subject of this piece was, or whether it was actually delivered, we do not know.

Albrecht Dürer, visiting Venice for a second time in 1506, describes Giovanni Bellini as still the best painter in the city, and as full of all courtesy and generosity towards foreign brethren of the brush.

In 1507 Bellini's brother Gentile died and Giovanni completed the picture of the Preaching of Saint Mark which he had left unfinished; a task on the fulfillment of which the bequest by the elder brother to the younger of their father's sketch-book had been made conditional.

In 1513 Giovanni's position as sole master (since the death of his brother and of Alvise Vivarini) in charge of the paintings in the Hall of the Great Council was threatened by one of his former pupils. Young Titian desired a share of the same undertaking, to be paid for on the same terms. Titian's application was granted, then after a year rescinded, and then after another year or two granted again; and the aged master must no doubt have undergone some annoyance from his sometime pupil's proceedings. In 1514 Giovanni undertook to paint The Feast of the Gods for the duke Alfonso I of Ferrara, but died in 1516.

Both in the artistic and in the worldly sense, the career of Giovanni Bellini was, on the whole, very prosperous. His long career began with Quattrocento styles but matured into the progressive post-Giorgione Renaissance styles. He lived to see his own school far outshine that of his rivals, the Vivarini of Murano; he embodied, with growing and maturing power, all the devotional gravity and much also of the worldly splendor of the Venice of his time; and he saw his influence propagated by a host of pupils, two of whom at least, Giorgione and Titian, equaled or even surpassed their master. Giorgione he out lived by five years; Titian, as we have seen, challenged him, claiming an equal place beside his teacher. Other pupils of the Bellini studio included Girolamo da Santacroce, Vittore Belliniano, Rocco Marconi, Andrea Previtali and possibly Bernardino Licinio.

In the historical perspective, Bellini was essential to the development of the Italian Renaissance for his incorporation of aesthetics from Northern Europe. Significantly influenced by Antonello da Messina, who had spent time in Flanders, Bellini made prevalent both the use of oil painting, different from the tempera painting being used at the time by most Italian Renaissance painters, and the use of disguised symbolism integral to the Northern Renaissance. As demonstrated in such works as Saint Francis in Ecstasy and the San Giobbe Altarpiece, Bellini makes use of religious symbolism through natural elements, such as grapevines and rocks. Yet his most important contribution to art lies in his experimentation with the use of color and atmosphere in oil painting.

The polyptych of St Vincent Ferrer, executed for the altar dedicated to the saint in the Venetian basilica of Saint John and Saint Paul, is Bellini's first public assignment. It comprises nine panels arranged in three parts: above the Pietà with the Virgin and the Angel of the Annunciation at the side; in the center the titular saint with Saint Christopher and Saint Sebastian at the sides; in the predella five miracles of the Saint. Formerly the painting was crowned by a lunette which is lost.

Champion of the Dominican Order, ardent and threatening preacher and controversialist, early confessor and later bitter adversary of Benedict XIII, the Spanish Saint had been sanctified in 1455 and immediately the Order had committed itself to a vast campaign of propaganda and assertion of the cult.

The looming figures of the central register, furrowed by the lines of their bodies and drapery, are emphasized by a brilliant light shining from below. The measure of their perspective is expressed by one or two basic elements: the arrows of Saint Sebastian, the stout staff of Saint Christopher in the foreground. Above, the Christ in Pietà (which, as always, faithfully follows a Byzantine iconographical model) is enclosed between an announcing angel and a Madonna with extremely limpid colors. In the angel, especially, the colors are blended with an almost glassy quality, and their pallid and alabaster splendor contrasts with the sudden blaze of red curtain behind the Virgin. The space is suggested by small details in an almost unnoticed and yet essential way: the deep dark folds of the curtain, and the sharp cold corner of the marmoreal pillar.

.jpg)

_Two.jpg)

_Three.jpg)

.jpg)

_1464_68.jpg)

_1464_68.jpg)

_1464_68.jpg)

_1464_68.jpg)

The picture shows the left predella representing Saint Vincent saves a drowned woman and brings back to life those buried under the ruins.

_Two_1464_68.jpg)

_Three_1464_68.jpg)

_Four_1464_68.jpg)

The signed and dated triptych with the 'Virgin and Child Enthroned with Two Musician Angels and Saints Nicholas, Peter, Mark, and Benedict' is in the Pesaro chapel of the Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari. In this chapel lie the mortal remains of Frenceschina Tron, wife of Pietro Pesaro, and was commissioned by the couple's sons, Nicolò, Marco, and Benedetto. The work thus portrays the eponymous saints of the entire family. The paintings wooden frame is probably designed by Bellini himself in perfect spatial harmony with the painting.

Although apparently more "archaic" in that it once again follows a polyptychal scheme (possibly on the request of the commissioners), in many respects the painting constitute a further evolution of the San Giobbe Altarpiece, of which it is reminiscent in many ways.

IANUA CERTA POLI DUC MENTEM DIRIGE VITAM: QUAE PERAGAM COMISSA TUAE SINT OMNIA CURAE

(Secure gateway to Heaven, guide my mind, lead my life, may everything I do be entrusted to your care).

Although apparently more "archaic" in that it once again follows a polyptychal scheme (possibly on the request of the commissioner), in many respects the painting constitute a further evolution of the San Giobbe Altarpiece, of which it is reminiscent in many ways. Extremely similar, for example, is the figure of the enthroned Virgin, immersed in fine golden dust that is contrasted only by the compact blue color of the mantle, which in some way isolates her in space. But mostly it is the study of light that continues, in favor of which the merely plastic elements lose their importance, while the question of space, despite the limit imposed by the shape of the triptych, is ingeniously resolved, not only by rebuilding within the painting the unity interrupted by the frame, but also by suggesting at the sides a vast perspective depth by means of a thin strip of landscape.

The painting representing the Madonna and Child, Saint Mark, Saint Augustine and the kneeling Agostino Barbarigo, and musician angels is known as the Barbarigo Altarpiece. It is signed and dated in the center of the Virgin's throne:

"IOANNES BELLINVS 1488".

It was commissioned by Doge Agostino Barbarigo, member of an important family of the Venetian aristocracy, who placed the painting in the most prominent position of the main hall in the family palace. Dying in 1501, Agostino left the canvas to the women's monastery of Santa Maria degli Angeli at Murano. However, the canvas was soon moved to San Pietro Martire, Murano, to make space for an Annunciation (now lost) commissioned to Titian.

In the painting Saint Mark, with an expression of affectionate protection, presents the kneeling Agostino to the Virgin. According to the words of the Doge himself, both the background landscape and the walled fortress on the right (similar to the one in the Pesaro Altarpiece of some years before) refer semiologically to Mary. The withered tree, on the other hand, a symbol of death and of guilt that must be expiated, refer to the Doge's family disgrace.

Dying in 1501, after a much-debated and variously evaluated dogate, Agostino left the canvas to the women's monastery of Santa Maria degli Angeli at Murano "because that figure of our Lady with angels is well suited to being placed above the high altar of her church...". And he added, "... And that neither our sons-in-law nor our daughters (Agostino had had five children, but the only son had died before him), nor our grand-children may put it in our great house, nor in any place other than above the high altar of that very pious monastery". Nonetheless, the canvas was soon moved to make space for an Annunciation commissioned to Titian.

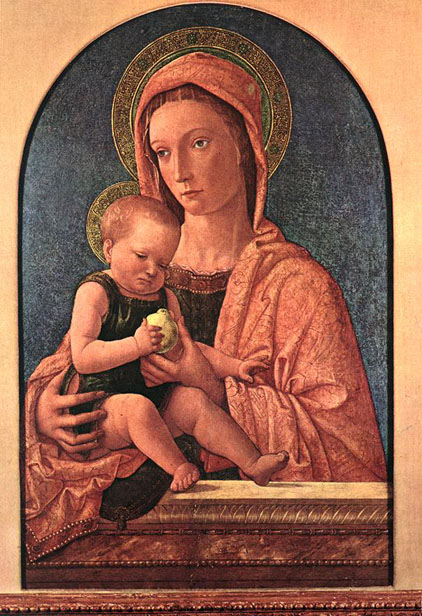

Bellini's paintings are distinguished however by a strange, subtle tension that always binds the mother and child in a relationship of profound pathos. The models for these Madonnas were the numerous Byzantine and Graeco-Cretan icons which circulated in Venice, and which Bellini occasionally transposed with absolute precision. Yet the static stereotypes of the Eastern images were radically altered and reinterpreted by him with a lyricism and poetic sensibility that unmistakably animates the figures and puts them in intimate contact with the spectator.

The still harsh Madonna and Child of the Museo Civico Malaspina in Pavia must be ascribed to around 1450-55. Originally assigned to Bartolomeo Vivarini, then to Bellini , then attributed to Lazzaro Bastiani, and finally to Bellini, this small panel is very closely related to the less disputed Madonna and Child of the John G. Johnson Collection in Philadelphia. The slender hands and iconic immobility still reveal the influence of Jacopo and the Vivarini family, while the boldy delineated line of the Child's figure and his transparent garment possibly derive from Squarcione, who was undoubtedly an inspiration to the young Bellini.

_1455.jpg)

The Bergamo painting is a harsh work, marked by a dramatic force which, in rather uncustomary fashion, the artist renders with the expressionistic masks of suffering of the Madonna and Saint John. The hands of the mother and son are clasped tightly together in a strong plastic join of Crivellesque inspiration, which in the past led scholars to suppose it was the work of a Ferrarese master. Nor should we underestimate the importance that the particular fascination of the Paduan altar of Donatello still held for Bellini at this time.

The painting is signed at the bottom as "IOHANNES B." The inscription at the top is illegible.

The landscape, though vast and expanded, is not yet conceived as a whole, but built up piece by piece according to an intellectual model filtered through the Gothic experiences of Jacopo. The figures are slender and sharply defined, and their grief, sculpted with raw pathos in the half-open mouths and extreme boniness of the bodies, is echoed in the stony contours of the landscape. These features had led some scholars in the 19th century to ascribe the painting to the Ferrarese artist Ercole de' Roberti.

The composition shows Elijah and Moses on Mount Tabor on either side of Christ, while below them are the disciples Peter, James and John blinded by the vision, according to the iconography suggested by the Synoptic Gospel. The composition was conceived according to a stratified ascending movement culminating in the figure of Christ, who is clothed in an ethereal pearly-white robe. The figures' shoulders and heads are forced into extreme foreshortening, dictated by the suggestion of the extraordinary Mantegnesque talent for perspective, but the stretch of landscape on the left is already expanded into an image of moving realism.

The panel, which is damaged at the top, probably comes from the church of San Giobbe.

_ca_1460.jpg)

_ca_1460.jpg)

The painting in the Museo Poldo-Pezzoli, stylistically very close to the Dead Christ representation in the Museo Correr in Venice, is siugned as "IOANNES BELLINVS". It is pervaded by a poignant and highly personal lyricism, which has the effect of transfiguring the divine drama into an expression of intense grief and infinite melancholy.

_1460_64.jpg)

This type of drawing shows similarities with the rigorous Flemish constructive technique though under closer scrutiny it appears to be aimed at a search for a much more solid and volumetrically constructed plastic quality. The delicate imperturbability of the Madonna, which would always remain a distinctive feature of Bellini's Virgins, shows not only its aforementioned Byzantine-iconic roots, but also how much the artist's culture owes to this heritage.

The views of critics about when the two works were painted do not concur, but it seems impossible to imagine that a long period of time separated their respective execution, as had been initially suggested, also by virtue of the diverse opinions regarding the precedence of the conception. It would be illuminating perhaps to discover the reasons that led to their execution, which do not appear to be a matter of chance, but almost certainly linked to family events, which with this important family portrait were solemnized.

_ca_1474.jpg)

The Pieta paintings of later years (like this painting in Rimini) are, compared to the earlier, pervaded by a poignant and highly personal lyricism, which has the effect of transfiguring the divine drama into an expression of intense grief and infinite melancholy.

The new relationship of form and color sealed by the quality of light leads to results of ineffable human participation in this painting which originally hung in the offices of the Magistrato della Milizia del Mare in the Palace of the Doges. The Virgin is seated with charming naturalness on the marble throne which is reminiscent of Donatello, and joins her sensitive hands in a gesture of mute adoration of her Son who lies fully relaxed in sleep across her knees. The chromatic values of the painting are reminiscent of the way Piero della Francesca used color in the mid-fifteenth century to unfold the perspective of his images.

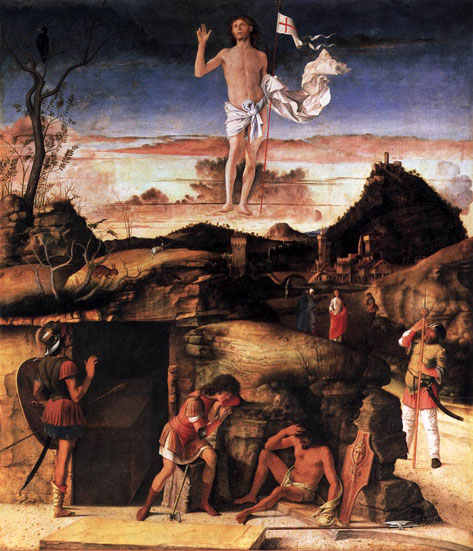

In this painting the artist follows Northern currents in his scrutiny of nature. Mystical yet realistic, his combination of faith and focus gives the painting a singularly convincing quality, its theme of resurrection a comforting one for the painting's funerary setting.

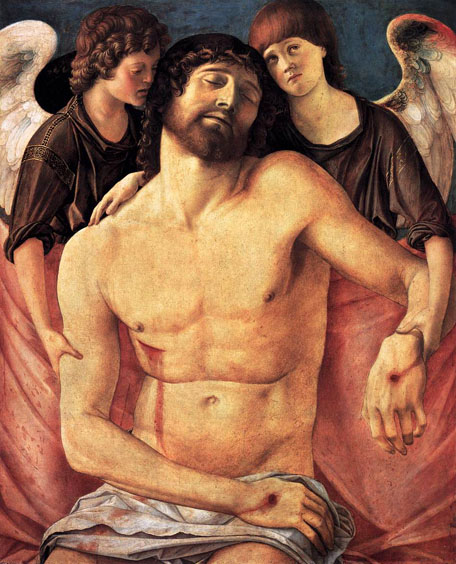

Among Bellini's favorite themes, to which he returned again and again, were the representations of the Madonna and the Lamentation in which the figure is shown half-length - a treatment already accorded the subject by Donatello. It provided the artist with the opportunity to combine a careful and subtle study of the nude with an expression of muted pain. Here Bellini succeeded in giving visual expression to new spiritual realms which no one before him had made manifest.

Two angels are supporting the naked body of the crucified Christ, who is sinking back from a sitting position. Each holds the dead man's arm with one hand, while their faces lean gently against his head. Bellini had previously executed two paintings on the same theme; one is now in the Pinacoteca Comunale, Rimini, the other in the National Gallery in London. In the first of these, which is in a landscape format, there are four angels. This rather too fanciful interpretation was abandoned in the London picture, which - making the most of the upright format - shows Christ with only two angels. It was not until he painted the picture now in Berlin that Bellini succeeded in achieving a composition which has the balance in a classical sense, and in which the natural beauty of the human body is completely in harmony with the spiritual content of the subject. At the same time, the graphic structure of the picture with its soft yet vigorous contours loses none of its prominence, and in this the likeness to the art of Mantegna is unmistakable. It is hardly surprising that precisely this style should have deeply impressed Albrecht Durer, the artist, and that, during his visit to Venice, he wrote of Bellini that he was 'still the best of all painters'.

The panel, the first known work by Bellini to bear a date, is signed and dated under the feet of the Child: IOANNES.BELLINUS.P. / 1487.

On the parapet in front of the Virgin, a detail present in many other similar compositions, there is a fruit. Like the walled and many-towered city on the right, and the inlet on the left, it is a symbol referring to the Virgin, according to the attributes assigned to her by hymns, analects and lauds ever since the Middle Ages. The mother and child are linked, more than by the tender embracing gesture, by the rapt, reflective gaze with which the Madonna engulfs her son. The painting is the prototype from which various similar compositions derive, such as the Madonna and Red Angels of the Accademia in Venice, with the child seated on the Virgin's left knee.

The Virgin and Child would have been intended for private devotion in the home, as more intimate and domestic counterparts to the large-scale sacred images that decorated the altars of Venetian churches.

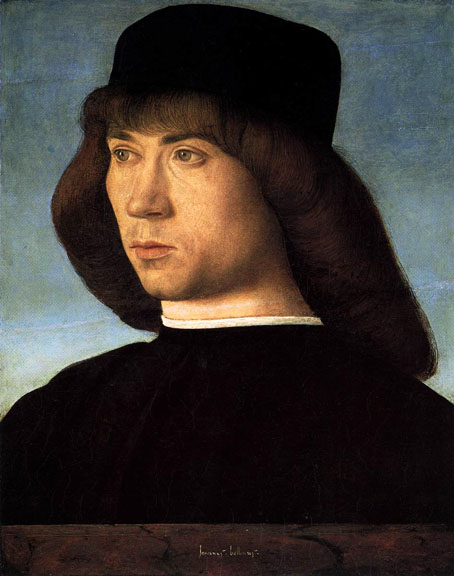

Although the concept and design of this portrait, considered to be among the finest of late quattrocento portraits extant, are derived from a Flemish prototype, the monumental simplicity of design, impersonal mood, and generalized surfaces betray the classical traditions of Italy.

_ca_1490.jpg)

An unusual theme for Bellini, the panels represent respectively: Lust tempting the virtuous man or Perseverance (Bacchus who from a chariot offers a plate of fruit to a warrior); Fickle Fortune (the woman on an unstable boat holding a sphere); Prudence (the naked woman pointing at a mirror); Falsehood (the man emerging from the shell). There are diverging opinions about the interpretation of the last two representations, such that they have been seen as: the Woman as Vanitas (on the basis of similar representations by Jacopo de' Barbari and Baldung Grien), and the Man in the shell as an allegory of Virtus Sapientia, since the shell might have a positive connotation as a generative principle.

_ca_1490.jpg)

_ca_1490.jpg)

_ca_1490.jpg)

_ca_1490.jpg)

The painting is one of the loftiest expressions of this frequently painted theme. It shows a magisterial development that has prompted critics to recall the fundamental teaching of Leonardo's "sfumato". The light, in fact, softly progressing over the faces and garments, strikes from the side of the assorted figures of the Virgin and Saints Catherine and Magdalene, silent companions of the former in sacred contemplation. Also in the characteristic symmetrical composition of all Bellini's sacred conversations, the spreading of a crepuscular and intimate light that tinges the figures is a demonstration of how far ahead Bellini was proceeding in these years in developing the concepts of space and color which had belonged to Antonello da Messina. The indistinct background, completely lacking any kind of connotation, is just "opened" in depth by the two diagonal wings of the saints which close at the sides the perfect pyramid formed by the group of the Madonna and Child. What is suggested is a warm and yet transparent depth in which the figures move without being engulfed.

There is also another, probably autograph version at the Prado in Madrid. The success of paintings like this can be measured by the large quantity of existing variants, mostly the work of the workshop or only partially autograph, and often reproduced in various copies.

In the past the painting was for long attributed to Giorgione owing to the warm diffusion of the light, the subtle but total naturalism, and the air drenched with golden color. Nevertheless the scheme used by Bellini was still the traditional one, planned according to a rational and controlled construction of the whole composition, although signs of the imminent new landscapist vision of the 16th century can be discerned.

The picture is, however, justly one of the most famous of the master's paintings, inspired, in the already complete tonal unity of the color, by a spirit of profound and visionary contemplation. From such works as this Giorgione takes his point of departure.

The artist s progress from the early portraits is apparent, and particularly from the still pre-Antonellian Portrait of Jorg Fugger, fixed and linked as it is to the analytical realism of late-Gothic art. In this figure, that fixity now assumes the quality of an emblem of his own highest dignity of office: a "denaturalization" almost that crystallizes, but does not dim, the psychological make-up of this highly cultivated man, even in spite of the fact that he is rendered with solemn detachment. Any psychological excess or a too penetrating individualization were prohibited in the name of official and hierarchical decorum. For this reason the portrait finishes by being placed in a line that is consistent more with the Venetian portraiture tradition than with the revolutionary and hyper-real portraits of Antonello da Messina.

_1505.jpg)

The image is a kind of synthesis of Bellini's dictates, a height of unattainable unity of poetry and metaphorical and religious meanings, which Bellini's complex culture on the one hand and his emotional depth on the other succeed in reaching. Few works in fact have such a highly developed double nature, demanding therefore a comprehension and an interpretation that take account of different levels. Unequivocal is the poignant lyricism of the landscape, and its rarefied and intensely limpid presence. But the sky pervaded by an indefinitely serene light and, against its deep blue transparency, the golden weightless trees, the neat graceful buildings, the air devoid of sounds or disturbances are also the ideal representation of the "quies" (spiritual reconciliation, idyllic or ascetic retreat into solitude) as the guiding principle of the Marian concept. Nor must we forget that if the Madonna sits down in a barren rocky land it is because she is a Madonna of Humility; if the lush and minutely depicted greenness of a meadow extends around her it is an allusion to the "hortus conclusus" of medieval hymns, while in the background other attributes referring to her are added: the fortress on the hill, the doorway, the well, the clouds (symbol of the humanity of Christ and also of divine mysteries), the struggle between the pelican and the snake.

The painting is a devotional work for private patrons. It is signed bottom left: IOANNES / BELLINUS.

An intervention by the workshop, if it existed, did not go further than some parts of the landscape, like the part with the ruins above left, which does appear stiff and rather heavy. The landscape is laden with the usual symbols and religious metaphors which Bellini was very careful about (the fig-tree, the withered tree, the ivy, the layered, agglomerated, crumbling rocks, etc.). However, in the very clear landscape view all these elements, affectionately and lyrically portrayed one by one, have not yet found the sublime harmony that was typical of the backgrounds which Bellini painted after 1500, and appear here more like a kind of splendid naturalistic compilation.

The plan of the large "historia", conceived as an ordered representation on a wide stage closed on three sides by large architectural walls, was clearly Gentile's. The style of the architecture, suggested to the painter during his journey in the East (where he had been sent by the Republic in 1479 in the retinue of a diplomatic mission) is reminiscent of Mameluke prototypes, which led to the speculation that Gentile may have proceeded from Constantinople to Jerusalem on a pilgrimage, and from there have recorded new architectural ideas that were different from Ottoman styles, the latter being more familiar to Venetians.

The official narrative, however, hinges on the crowd gathered around the preaching saint in the square, where, according to Venetian canons of public portraiture, the characters appear as a socially and hierarchically defined group.

Critics have advanced a number of theories concerning the extent to which either brother was responsible for the painting of this large human group. Apart from Vasari, who in the first edition of the Lives (1550) mentioned Gentile as the only author of the painting, only to drop this idea in the second edition (1568), the old historiographers attributed the Sermon to both brothers without entering into detail about the individual contributions.

Modern critics see Giovanni as the hand behind the more precisely psychologically analyzed portraits, placed in the central group, many of whom are shown with a three-quarter turn, and of some characters on the far left. Others assert that Saint Mark himself, in addition to the senator listening on the right, may be the work of Giovanni.

Here too the research carried out before and during the last restoration was useful in giving new and more precise answers to the problem, revealing the numerous modifications of arrangement and character that some faces have undergone, and the additions and corrections applied to a part of the drawing of the buildings.

But beyond the precise detailed statements, which are in fact secondary, the intervention of Giovanni should be evaluated on the overall conception of the composition. Moving and animating the characters, indeed, restoring to them a unique and peculiar individuality, lightening, even if slightly, the severity of Gentile's "order", Giovanni went beyond the solemn historical consecration typical of his brother's great narrations and imprinted in the "story" a human dimension together with a masterly development towards modernity.

The analysis carried out on the occasion of the last restoration (1986) revealed the absence of a preparatory drawing in the landscape. This confirms that, while for the figures Bellini still felt the need to lay out the image beforehand, by this time he had a full and total confidence in the manipulation and figurative arrangement of the landscape. Over the preparatory ground he proceeded with light strokes, on which he often intervened with his fingertips.

Even fifty years after the beginning of his career Bellini has not abandoned the habit inherited from his father Jacopo of the sketch in a notebook and the single study from life. Here, then, is a tiny cheetah on the classical memorial stone, farming activities and animals. The result is a transparent landscape with a light, ordered structure. Although, in this respect, it is certainly still linked to the Quattrocento, the light is now so much the essence of it that it transforms and directs it toward tonalism. The organization of the image is quite unitary, also because it is bathed in a soft, gentle, auroral light that alludes to the dawn of a new era.

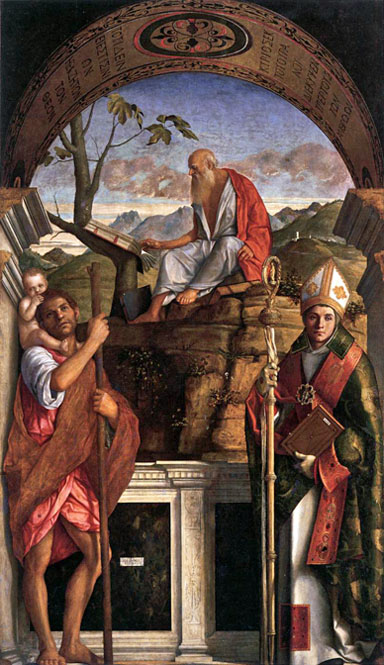

The painting had been commissioned in 1494 by the merchant Giorgio Diletti, who had left instructions in his will for the construction of an altar and the execution of an altarpiece to go with it representing Saints Jerome, Louis and Crisostomo. The almost twenty years that elapsed between the ordering and execution of the altarpiece, and the partial modification of the identity of the saints requested by Diletti, have raised a number of queries which scholars have only partly resolved. The first uncertainty concerns the bishop saint on the right holding a book bearing the inscription "De civitate Dei", which has led some scholars to identify him with St Augustine. However, the inscription on the book is almost certainly a later addition: its extraneousness is revealed by the fact that it is written on the back of the volume and by the uncertainty of the inscription itself, unimaginable in Bellini who was always highly accurate and extremely precise. Besides, the Anjou lilies on the bishop's cloak confirm that it must be the French noble Louis, who renounced the throne to become a Franciscan. According to a complex iconological interpretation of the altarpiece, Saint Louis in his lavish bishop's robes represents a pastoral and liturgical significance. In this he provides a contrast with Christopher, an emblem of the active faith and preaching, and both are placed under an arch, a symbolic image of the church, on which the second verse of Psalm 14 is written in Greek: "The Lord looked down from heaven upon the children of men, to see if there were any that did understand, and seek God". The choice of the Greek language is explained, besides the fact that the church of San Giovanni Crisostomo was the center of the Greco-Venetian community, also by remembering Bellini's contacts with the erudite circle that revolved around Aldo Manuzio. Manuzio, indeed, is credited with an important edition in Greek of the Psalter, which was printed between 1496 and 1498.

Beyond the parapet Saint Jerome a hermit and doctor of the Church represents the highest point of spiritual life that of mystical exaltation and revealed science. Beside him the fig-tree symbolizes that he has been chosen by the Lord to understand its supreme law.

According to this interpretation we are therefore confronted by a clear, conscious stand-point in the contemporary religious debate that existed in Venice during those years: a position by which action and contemplation are a unitary moment in the ecclesiastical path.

Undoubtedly such a complex and culturally significant proposition must have been established by the client in the first place; nonetheless, Bellini's humanistic and theological lucidity too is certainly confirmed once again.

The represented Saints are John the Evangelist, James, Mark, Francis, Louis of Toulouse, Anthony Abbot, Augustine, and John the Baptist. (Note that Francis and Louis are at the center of the group of eight saints.)

This scene is not an Assumption but another image of glory exalting the Immaculate Conception.

According to the current interpretations, the scene illustrates a passage from Ovid's Fasti (The Feasts), a long classical poem that recounts the origins of many ancient Roman rites and festivals. Ovid (43 B.C. - A.D. 17), describing a banquet given by the god of wine, mentioned an incident that embarrassed Priapus, god of virility.

The beautiful nymph Lotis, shown reclining at the far right, was lulled to sleep by wine. Priapus, overcome by lust, seized the opportunity to take advantage of her and is portrayed bending forward to lift her skirt. His attempt was foiled when an ass, seen at the left, "with raucous braying, gave out an ill-timed roar. Awakened, the startled nymph pushed Priapus away, and the god was laughed at by all." Priapus, his pride wounded, took revenge by demanding the annual sacrifice of a donkey.

The ass stands next to Silenus, a woodland deity who used the beast to carry wood, thus wears a keg on his belt because he was a follower of Bacchus, god of wine. Bacchus himself, seen as an infant, kneels before them while decanting wine into a crystal pitcher.

Reading from left to right, the principal figures are:

Silenus, a woodland god attended by his donkey

Bacchus, the infant god of wine crowned with grape leaves

Faunus or Silvanus, an old forest god wearing a wreath of pine needles

Mercury, the messenger of the gods carrying his caduceus or herald's staff

Jupiter, the king of the gods accompanied by an eagle

An unidentified goddess holding a quince, a fruit associated in the ancient world with marriage

Pan, a satyr with a grape wreath who blows on his shepherd's pipes

Neptune, the god of the sea sitting beside his trident harpoon

Ceres, the goddess of cereal grains with a wreath of wheat

Apollo, god of the sun and the arts, crowned by laurel and holding a Renaissance stringed musical instrument, the lira da braccio, in lieu of a classical lyre

Priapus, the god of virility and of vineyards with a scythe, used to prune orchards, hanging from the tree above him

Lotis, one of the naiads, is a nymph of fresh waters who represents chastity.

These deities are waited upon by three naiads, nymphs of streams and brooks, and two satyrs, goat-footed inhabitants of the wilderness. On the distant mountain, which Titian added to Bellini's picture, two more satyrs cavort drunkenly and a hunting hound chases a stag.

Certainly the small Bacchus must be seen as very close to the 'Feast of the Gods', the masterpiece of Bellini's last years. Indeed, the resemblance between the Bacchus of the 'Feast and the Young Bacchus' has been pointed out several times. In the small canvas, however, we witness yet again the incredible openness that the almost ninety year-old artist succeeded in advancing in his affirmation of a new profane sensibility, the same that ran through the Naked Woman 'in front of the Mirror of the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna and the Drunkenness of Noah of the Musée des Beaux Arts in Besançon. The same landscape background against which the young Bacchus is seated was by now an image that was so essential and reduced to pure ideal substance that it seems referable only to the other foreshortening, similarly idealized and eternal, of the Viennese 'Naked Woman'. Also in addressing himself to and portraying nature Bellini had covered a considerable distance. One might say, indeed, that he no longer needed to look at it or represent it with elements that were in some way real or recognizable; nor did he needs to animate it in any way. He gave only its pure structure, the inner and "philosophical" vision.

Source: Art Renewal Center

Source: Web Gallery of Art

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.