1477 - 1510

Giorgione is the familiar name of Giorgio Barbarelli da Castelfranco, an Italian painter, a seminal artist of the High Renaissance in Venice. Giorgione is known for the elusive poetic quality of his work, though only about six surviving paintings are known for certain to be his work. The resulting uncertainty about the identity and meaning of his art has made Giorgione one of the most mysterious figures in European painting.

Giorgione's life is described in Giorgio Vasari's Vite. The painter came from the small town of Castelfranco Veneto, outside Venice. His name sometimes appears as Zorzo. The variant Giorgione (or Zorzon) may be translated "Big George". How early in boyhood he went to Venice we do not know, but stylistic evidence supports the statement of Carlo Ridolfi that he served his apprenticeship there under Giovanni Bellini; there he settled and made his fame.

Contemporary documents record that his gifts were recognized early. In 1500, when he was only twenty-three (that is, if Vasari gives rightly the age at which he died), he was chosen to paint portraits of the Doge Agostino Barberigo and the condottiere Consalvo Ferrante. In 1504 he was commissioned to paint an altarpiece in memory of another condottiere, Matteo Costanzo, in the cathedral of his native town, Castelfranco. In 1507 he received at the order of the Council of Ten part payment for a picture (subject not mentioned) on which he was engaged for the Hall of the Audience in the Doge's Palace. In 1507-1508 he was employed, with other artists of his generation, to decorate with frescoes the exterior of the newly rebuilt Fondaco dei Tedeschi (or German Merchants' Hall) at Venice, having already done similar work on the exterior of the Casa Soranzo, the Casa Grimani alli Servi and other Venetian palaces. Very little of this work survives today.

Vasari gives also as an important event in Giorgione's life, and one which had influence on his work, his meeting with Leonardo da Vinci on the occasion of the Tuscan master's visit to Venice in 1500. All accounts agree in representing Giorgione as a person of distinguished and romantic charm, a great lover and musician, given to express in art the sensuous and imaginative grace, touched with poetic melancholy, of the Venetian existence of his time. They represent him further as having made in Venetian painting an advance analogous to that made in Tuscan painting by Leonardo more than twenty years before; that is, as having released the art from the last shackles of archaic rigidity and placed it in possession of full freedom and the full mastery of its means.

He was certainly very closely associated with Titian; Vasari says Giorgione was Titian's master, while Ridolfi says they both were pupils of Bellini, and lived in his house. They worked together on the Fondaco dei Tedeschi frescoes, and Titian finished at least some paintings of Giorgione after his death, although which ones remains very controversial.

Giorgione also introduced a new range of subjects. Besides altarpieces and portraits he painted pictures that told no story, whether biblical or classical, or if they professed to tell such, neglected the action and simply embodied in form and color moods of lyrical or romantic feeling, much as a musician might embody them in sounds. Innovating with the courage and felicity of genius, he had for a time an overwhelming influence on his contemporaries and immediate successors in the Venetian school, including Titian, Sebastiano del Piombo, Palma il Vecchio, il Cariani, Giulio Campagnola (and his brother), and even on his already eminent master, Giovanni Bellini. In the Venetian mainland, Giorgionismo strongly influenced Morto da Feltre, Domenico Capriolo, and Domenico Mancini.

Giorgione died, probably of the plague then raging, by October 1510, the date of a letter by Isabella d'Este to a Venetian friend asking him to buy a painting by Giorgione; she is aware he is dead. Significantly, the reply a month later said the painting was not to be had at any price.

His name and work continue to exercise a spell on posterity. But to identify and define, among the relics of his age and school, precisely what that work is, and to distinguish it from the similar work of other men whom his influence inspired, is a very difficult matter. Though there are no longer any supporters of the "Pan Giorgionismus" which a century ago claimed for Giorgione nearly every painting of the time that at all resembles his manner, there are still, as then, exclusive critics who reduce to half a dozen the list of extant pictures which they will admit to be actually by this master.

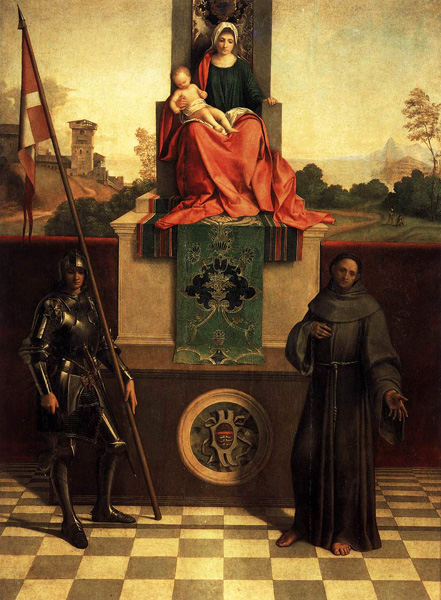

For his home town of Castelfranco, Giorgione painted the Castelfranco Madonna, an altarpiece in sacra conversazione form - Madonna Enthroned, with Saints on either side forming an equilateral triangle. This gave the landscape background an importance which marks an innovation in Venetian art, and was quickly followed by his master Giovanni Bellini and others. Giorgione began to use the very refined chiaroscuro called sfumato - the delicate use of shades of color to depict light and perspective - around the same time as Leonardo. Whether Vasari is correct in saying he learnt it from Leonardo's works is unclear - he is always keen to ascribe all advances to Florentine sources. Leonardo's delicate color modulations result from the tiny disconnected spots of paint that he probably derived from manuscript illumination techniques and first brought into oil painting. These gave Giorgione's works the magical glow of light for which they are celebrated.

This smallish altarpiece echoes the artistic approach developed by Giovanni Bellini, who was probably one of Giorgione's teachers. Giorgione softens both the atmosphere surrounding the figures and that in the space before the viewer. This atmospheric veil has a palpable analogy with the methods of Leonardo da Vinci, who was known to have been in Venice in 1500 and it is possible that Giorgione had seen some works by the Florentine genius. Yet the figural proportions and the lacy landscape speak to a fully personal Giorgionesque idiom.

_ca_1505.jpg)

Most entirely central and typical of all Giorgione's extant works is the Sleeping Venus now in Dresden, first recognized by Morelli, and now universally accepted, as being the same as the picture seen by Michiel and later by Ridolfi (his 17th century biographer) in the Casa Marcello at Venice. An exquisitely pure and severe rhythm of line and contour chastens the sensuous richness of the presentment: the sweep of white drapery on which the goddess lies, and of glowing landscape that fills the space behind her, most harmoniously frame her divinity. The use of an external landscape to frame a nude is innovative; but in addition, to add to her mystery, she is shrouded in sleep, spirited away from accessibility to her conscious expression.

Giorgione placed the Venus across the whole width of the painting. She stretches one arm behind her head, making a long, continuous slope of body whose gentle curves echo the hills of the landscape behind and suggest some form of connection between the female depicted and nature. Painted at just the moment when Venice was defending its claims on the terra firma, it may, therefore, be possible to read Venus (Venere) as Venice (Venezia).

Venus's sensuality is heightened by her red lips and by the deep red velvet and white satin drapery upon which her creamy body lies. Significantly, she is asleep, so the issue of decorum is bypassed. Her sleep implies dreaming and transport of the figure to another world. Thus the painting may be interpreted as a poetic evocation of a classical idyll.

Several works of great beauty associated with Giorgione involve the collaboration of another distinctive master. In the 'Sleeping Venus' a significant share has been assumed for Titian, especially in the landscape, where on the right a cupid has been painted out. The outstretched figure, stocky in proportions, is usually considered to be by Giorgione. The drawing is only approximate, with the outlines blurred to produce a gradual transition between the barely modeled flesh and the surrounding surface. But the edges are nonetheless legible, and they form a flattened lozenge-shaped, pale, collage-like form lying close to the picture plane, a device favored over juxtapositions of darks and lights to conjure up an illusion of three-dimensionality. Giorgione fully exploited the sensuous potential of both the medium and the subject. There is a decidedly erotic air to the totally unselfconscious young woman whose pale flesh is contrasted to the silky cloth.

If compared with Titian's Venus of Urbino the differences between the two become clear since Titian has taken over the pose and the figural type almost verbatim from Giorgione; they are differences of temperament and personality more than of time passed. If the 'Sleeping Venus' was actually completed by Titian, as is frequently assumed, the overall effect remains tightly connected with Giorgione's style, and one might also suppose that it falls chronologically near the end of his short career, for we should assume that it was left unfinished at his death.

It is recorded by Michiel that Giorgione left this piece unfinished and that the landscape, with a Cupid which subsequent restoration has removed, were completed after his death by Titian. The picture is the prototype of Titian's own Venus of Urbino and of many more by other painters of the school; but none of them attained the fame of the first exemplar. The same concept of idealized beauty is evoked in a virginally pensive Judith from the Hermitage Museum, a large painting which exhibits Giorgione's special qualities of color richness and landscape romance, while demonstrating that life and death are each other's companions rather than foes.

Apart from the altarpiece and the frescoes, all Giorgione's surviving works are small paintings designed for the wealthy Venetian collector to keep in his home; most are less than two foot in either dimension. This market had been emerging over the last half of the fifteenth century in Italy, and was much better established in the Netherlands, but Giorgione was the first major Italian painter to concentrate his work on it to such an extent - indeed soon after his death the size of such paintings began to increase with the prosperity and palaces of the patrons.

The Tempest has been called the first landscape in the history of Western painting. The subject of this painting is unclear, but its artistic mastery is apparent. The Tempest portrays a soldier and a breast-feeding woman on either side of a stream, amid a city's rubble and an incoming storm. The multitude of symbols in The Tempest offer many interpretations, but none is wholly satisfying. Theories that the painting is about duality (city and country, male and female) have been dismissed since radiography has shown that in the earlier stages of the painting the soldier to the left was a seated female nude.

This painting is known since 1530 as the 'Tempesta' because of the storm that thunders in the background. The meaning of the painting has been greatly debated. Some writers believe that the painting simply lacks a subject, others have sought explanations in ancient mythology and the Bible, or see the work as allegorical. Whatever the painting's intended subject, it is clearly a revolutionary work, one in which evocative color, form, and light seem both to demand and to frustrate attempts at a literal reading.

This painting, the meaning of which has been greatly debated, marks a moment of capital importance in the renovation of the Venetian style painting, and perhaps is the most representative of the very few genuine surviving works of Giorgione.

The vigor of cultural life at the beginning of the sixteenth century provided exactly the right fertile ground for the personality of Giorgione. With Giovanni Bellini and Vittore Carpaccio as examples in his early training and with his attentive interest in Northern European painting of Belgium he soon decided to attempt a naturalistic language. Color attains to new all-important powers of expression of the poetic equivalence of man and nature in a single, fearful apprehension of the cosmos. The finest of all expressions of this new vision of the world is the 'Tempest', commissioned from the artist by Gabriele Vendramin, one of the leading lights in intellectual circles in the Venice of the day, in whose house the picture was recorded as having been hung by Marcantonio Michiel in 1530.

Though many interpretations of the subject of this small painting have been suggested, none of them is totally convincing. Thus the mystery remains of what exactly the significance is of the fascinating landscape caught at this particular atmospheric moment, the breaking of a storm. Anxious waiting seems to characterize the mood of both the human figures, absorbed in private reveries, and every other detail, from the little town half-hidden behind the luxuriant vegetation and the lazy, tortuous course of the stream to the ancient ruins, the houses, the towers and the buildings in the distance which pale against the blue of the sky. The fascination of the painting arises from the pictorial realization of the illustrative elements. In the vibrant brightness which immediately precedes the breaking of the storm the chromatic values follow one another in fluid gradations achieved by the modulation of the tones in the fused dialectic of light and shadow in an airy perspective of atmospheric value within a definite space. Completely liberated from any subjection to drawing or perspective, color is the dominant value in a new spacial-atmospheric synthesis which is fundamental to the art of painting in its modern sense.

The Three Philosophers is equally enigmatic and its attribution to Giorgione is still disputed. The three figures stand near a dark empty cave. Sometimes interpreted as symbols of Plato's cave or the Three Magi, they seem lost in a typical Giorgionesque dreamy mood, reinforced by a hazy light so characteristic of his other landscapes, such as the Pastoral Concert, now in the Louvre. The latter "reveals the Venetians' love of textures", for the painter "renders almost palpable the appearance of flesh, fabric, wood, stone, and foliage". The painting is devoid of harsh contours and its treatment of landscape has been frequently compared to pastoral poetry, hence the title.

Whatever the precise theme, one can find three ages of man, three distinct temperaments, and three different nations. There are important pentimenti, more easily accomplished in the oil medium that Giorgione favored than with tempera. The present picture may have been cut down on all sides, judging from a later copy. If there was an element of collaboration, the invention and the figure types, their poses, and the relation of one to another are Giorgione's. Sebastiano's role must have been limited literally to finishing the work, that is, giving it the final surface and unifying the elements. In the 'Three Philosophers' the figures are rather weightless, silent images, placed somewhat unspecifically in space, haphazardly related, as it were, to the landscape. For example, the youngest figure, seated toward the centre of the composition, is partly blocked out by the oriental with the deep red garment, and his head, in profile, is apparently unrelated to the twin tree trunks behind it. The natural and private world Giorgione has created envelops us with its mystery and poetry, with its antiscientific structure and even its rather un-classical choice of figural types and poses.

The painting belonged to the collection of Archduke Leopold Wilhelm in Brussels, as shown by the painting of David Teniers (now in the Prado, Madrid). Teniers also painted a strongly modified copy of this painting (now in the National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin).

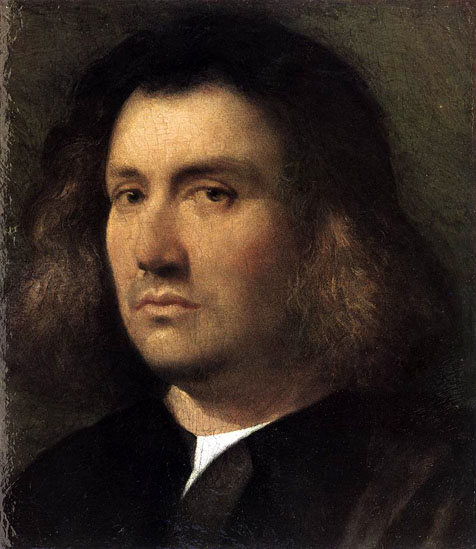

Giorgione and the young Titian revolutionized the genre of the portrait as well. It is exceedingly difficult and sometimes simply impossible to differentiate Titian's early works from those of Giorgione. None of Giorgione's paintings are signed and only one bears a reliable date: his Portrait of Laura (June 1, 1506), one of the first to be painted in the "modern manner", distinguished by dignity, clarity, and sophisticated characterization. Even more striking is the Portrait of a Young Man now in Berlin, acclaimed by art historians for "the indescribably subtle expression of serenity and the immobile features, added to the chiseled effect of the silhouette and modeling".

_1506.jpg)

This young woman is perhaps a courtesan and a poet, the combination of which is not unknown in Renaissance Venice. Her name is assumed to be 'Laura' because of the depiction of laurel springs behind her. The sensuousness of the representation, the soft flesh of the breast against the fur of her garment, is consistent with the delicacy of treatment in the medium of oil paint, of which Giorgione was an unequaled master.

It is assumed that the sitter probably was also the model of the Tempest.

The colors of this brilliant portrait are unfortunately faded due to an over cleaning before 1939.

Few of the portraits attributed to Giorgione appear as straightforward records of the appearance of a commissioning individual, though it is perfectly possible that many are. Many can be read as types designed to express a mood or atmosphere, and certainly many of the examples of the portrait tradition Giorgione initiated appear to have had this purpose, and not to have been sold to the sitter. The subjects of his non-religious figure paintings are equally hard to discern. Perhaps the first question to ask is whether there was intended to be a specific meaning to these paintings that ingenious research can hope to recover. Many art historians argue that there is not: "The best evidence, perhaps, that Giorgione's pictures were not particularly esoteric in their meaning is provided by the fact that whilst his stylistic innovations were widely adopted, the distinguishing feature of virtually all Venetian non-religious painting in the first half of the sixteenth century is the lack of learned or literary content".

_1508_10.jpg)

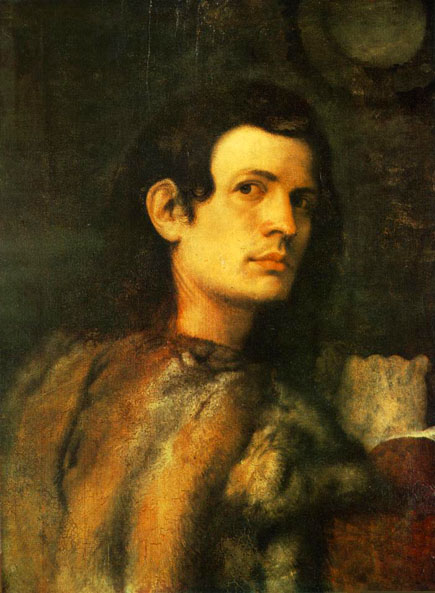

The emblems on the parapet - the small hat with a V on it, the female triple head, the tiny tablet and the inscription - have been variously interpreted. One explanation, the most frequent and perhaps the most acceptable, is that this picture is a portrait of the poet Antonio Broccardo.

Restored in 1990

_ca_1502.jpg)

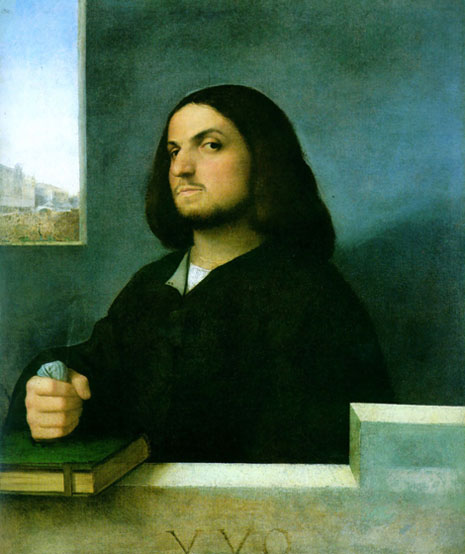

The unidentified sitter's expression of calculating, almost cruel, appraisal is amplified by the gesture of his closed fist. The inscription on the parapet does not help to identify either the sitter or the artist, although Titian sometimes "carved" his initials in a similar manner on painted parapets. These letters, VVO, have been interpreted as a form of the Latin vivo (in life). This would suggest that the portrait was painted from life and that it confers a measure of immortality on both subject and painter. It may be more likely, however, that it abbreviates a humanist motto, perhaps virtus vincit omnia (virtue conquers all).

The difficulty in making secure attributions of work by Giorgione's hand dates from soon after his death, when some of his paintings were completed by other artists, and his considerable reputation also led to very early erroneous claims of attribution. The vast bulk of documentation for paintings in this period relates to large commissions for Church or government; the small domestic panels that make up the bulk of Giorgione's oeuvre are always far less likely to be recorded. Other artists continued to work in his style for some years, and probably by the mid-century deliberately deceptive work had started.

Primary documentation for attributions comes from the Venetian collector Marcantonio Michiel. In notes dating from 1525 to 1543 he identifies twelve paintings and one drawing as by Giorgione, of which five of the paintings are identified virtually unanimously with surviving works by art historians: The Tempest, The Three Philosophers, Sleeping Venus, Boy with an Arrow, and Shepherd with a Flute (not all accept the last as by Giorgione however). Michiel describes the Philosophers as having been completed by Sebastiano del Piombo, and the Venus as finished by Titian (it is now generally agreed that Titian did the landscape). Some recent art historians also involve Titian in the Three Philosophers. The Tempest is therefore the only one of the group universally accepted as wholly by Giorgione. In addition, the Castelfranco Altarpiece in his home-town has rarely, if ever, been doubted, nor have the wrecked fresco fragments from the German warehouse. The Vienna Laura is the only work signed and dated by Giorgione (on the back). The early pair of paintings in the Uffizi are usually accepted.

After that, things become more complicated, exemplified by Vasari. In the first edition of the Vite (1550), he attributed a Christ Carrying the Cross to Giorgione; in the second edition completed in 1568 he ascribed authorship, variously, to Giorgione in his biography, which was printed in 1565, and to Titian in his, printed in 1567. He had visited Venice in between these dates, and may have obtained different information. The uncertainty in distinguishing between the painting of Giorgione and the young Titian is most apparent in the case of the Louvre Concert Champatre (or Pastoral Concert), described in 2003 as "perhaps the most contentious problem of attribution in the whole of Italian Renaissance art", but affects a large number of paintings possibly from Giorgione's last years.

_1508_09.jpg)

The painting has been interpreted as an allegory of Nature, similar to Giorgione's Storm, which was undeniably painted by him; it was even viewed as the first example of the modern herdsman genre. Its message must be more complex than this. It is likely that the master consciously unified several themes in this painting, and the deciphering of symbols required a degree of erudition even at the time of its creation. During the eighteenth century the painting was known by the simple name of "Pastorale" and only subsequently was it given the title "Fate champatre" or "Concert champatre", owing to its festive mood. Modern research has pointed out that the composition is in fact an allegory of poetry.

The female figures in the foreground are the Muses of poetry; their nakedness reveals their divine being. The standing figure pouring water from a glass jar represents the superior tragic poetry, while the seated one holding a flute is the Muse of the less prestigious comedy or pastoral poetry. The well-dressed youth who is playing a lute is the poet of exalted lyricism, while the bareheaded one is an ordinary lyricist. The painter based this differentiation on Aristotle's "Poetica".

The scenery is characterized by a duality. Between the elegant, slim trees on the left, we see a multi-leveled villa, while on the right, in a lush grove, we see a shepherd playing a bagpipe. Yet the effect is completely unified. The very presence of the beautiful, mature Muses provides inspiration; the harmony of scenery and figures, colors and forms proclaims the close interrelationship between man and nature, poetry and music.

The Concert Champatre is one of a small group of paintings, also including the Virgin and Child with Saint Anthony and Saint Roch in the Prado, which are very close in style and, according to Charles Hope, have been "more and more frequently given to Titian, not so much because of any very compelling resemblance to his undisputed early works - which would surely have been noted before - as because he seemed a less implausible candidate than Giorgione. But no one has been able to create a coherent sequence of Titian's early works that includes these ones, in a way that commands general support, and fits the known facts of his career. An alternative proposal is to assign the Concert Champatre and the other pictures like it to a third artist, the very obscure Domenico Mancini..".

At an earlier period in Giorgione's short career, a group of paintings is sometimes described as the "Allendale Group", after the Allendale Nativity (or Allendale Adoration of the Shepherds, rather more correctly) in the National Gallery of Art, Washington. This group includes another Washington painting, the Holy Family, and an Adoration of the Magi predella panel in the National Gallery, London. This group, now often expanded to include a very similar Adoration of the Shepherds in Vienna, and sometimes further, are usually included or excluded together from Giorgione's oeuvre. Ironically, the Allendale Nativity caused the rupture in the 1930's between Lord Duveen, who sold it to Andrew Mellon as a Giorgione, and his expert Bernard Berenson, who insisted it was an early Titian. Berenson had played a significant part in reducing the Giorgione catalogue, recognizing fewer than twenty paintings.

This important work had an immediate impact on Venetian painting. The composition is divided into two parts, the dark cave on the right and a luminous Venetian landscape on the left. The shimmering draperies of Joseph and Mary are set off by the darkness behind them, and are also contrasted with the tattered dress of the shepherds. The scene is one of intense meditation; the rustic shepherds are the first to recognize Christ's divinity and they kneel accordingly. Mary and Joseph also participate in the adoration, creating an atmosphere of intimacy.

Despite being greatly praised by all contemporary writers, and remaining a great name in Italy, Giorgione became less well known to the wider world, and many of his (probable) paintings were assigned to others. The Hermitage Judith for example, was long regarded as a Raphael, and the Dresden Venus a Titian. In the late 19th century a great Giorgione revival began, and the fashion ran the other way. Despite well over a century of dispute, controversy remains active.

Though he died at the young age of 33, Giorgione left a lasting legacy to be developed by Titian and 17th-century artists. Giorgione never subordinated line and color to architecture, nor an artistic effect to a sentimental presentation. He was the first to paint landscapes with figures, the first to paint genre - movable pictures in their own frames with no devotional, allegorical, or historical purpose - and the first whose colors possessed that ardent, glowing, and melting intensity which was so soon to typify the work of all the Venetian School.

The attribution to Giorgione is not universally accepted, some scholars attribute the painting to a painter close to Giorgione.

_1506_10.jpg)

The Italian title, Il Tramonto, captures the painting's special temper better than the English translation, for in Italian the sun sets literally 'beyond the mountain'. Within a deep landscape meeting the horizon in a startling band of blue, two travelers halt besides a pool, from whose murky waters a little beaked monster emerges.

A hermit inhabits the dark cave on the far side. The mounted Saint George in the middle distance is a restorer's reconstruction, added in 1934 to cover an area of flaking paint, and to account for what appears, in a photograph of the period, to be the vestigial tail of a dragon. Other reconstructed areas include the larger monster in the water. The modern additions make unsafe any reading of the picture's intended meaning. If Saint George was originally present, the hermit may be Anthony Abbot a saint distressed with sores, protector against epidemics - of whom it was told that demons in the shape of monsters came at nightfall to 'tear his body with teeth, with horns, and with claws'. The two men in the foreground may be Saint Roch, a medieval French pilgrim who caught the plague while nursing the sick, and his companion Gothardus tending the ulcer on the saint's leg. The body of Saint Roch, one of the main protectors against pestilence, is one of Venice's great relics.

If we compare II Tramonto with, for example, Patenier's landscape painted a few years later, it is possible to understand the great impact of Giorgione's work. For all its artificiality, this landscape invites us to enter it in imagination; the construction, in wedge-shaped planes alternately light and dark, stresses continuity from foreground through well-defined intervening space to the blue horizon. The wispy tree in the center, like the cliff and foliage on either side, pushes back the far from the near. Soft gradations from shadow into light, contours and reflections blurred as if by haze, the isolated and mysterious figures, the barely visible, perhaps imaginary monsters, the alpine town in the distance, combine to create a sense of profound yet indefinable emotion, as 'Brightness falls from the air...' Thomas Nashe's haunting line may be more than visually apt: it comes from a poem entitled 'In Time of Pestilence'.

Source: Web Gallery of Art

Source: Art Renewal Center

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.