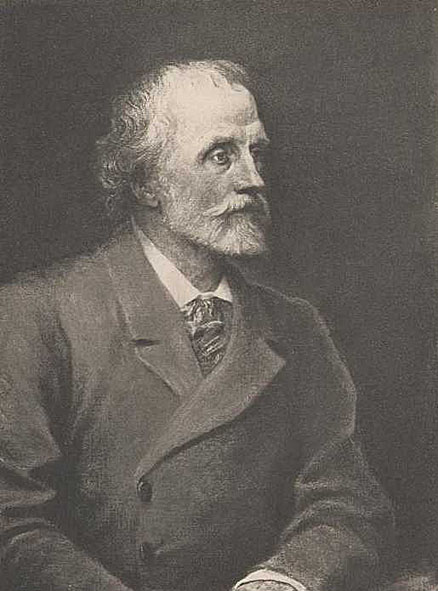

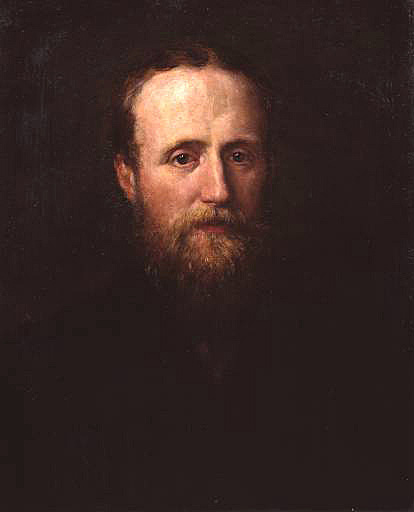

English Victorian Painter and Sculptor

1817 - 1904

Watts became famous in his lifetime for his allegorical works, such as Hope and Love and Life. These paintings were intended to form part of an epic symbolic cycle called the "House of Life", in which the emotions and aspirations of life would all be represented in a universal symbolic language.

So what makes this such a compelling work? Watts certainly didn't know. He claimed that the idea came to him quickly and easily. Other works were pondered over and reworked for years before being exhibited, but none had the same impact. His attempts to follow up Hope with Faith and Charity - the other two "theological virtues" - were far less well received.

Perhaps the answer lies in the fact that it is not, in essence, a traditionally Christian image. This hunched, isolated, blindfolded and barefoot woman seems, despite the title, to be on the edge of despair. This is not the "sure and certain hope" of Christian tradition. It is more like the hope implied by the expression "hoping against hope". It is the hope of those who refuse to submit to despair when it beckons.

This is probably why the painting seemed so persuasive to Watts' Victorian contemporaries. As the art historian Malcolm Warner has pointed out, in an age beset by religious doubts, the work appeared to visualize Tennyson's dubious expression of faith from In Memoriam: "To faintly trust the larger hope." The trust expressed by the figure is certainly faint. Only one string on her crude wooden lyre remains unbroken. It is her only hope of music, but seems as likely to snap as to sound. In other words, she remains entranced by beauty even when it seems so tenuous.

This preoccupation with music and beauty is unsurprising in a painting exhibited at the Grosvenor Gallery, which was strongly associated with the Aesthetic movement. In many ways Hope is as much concerned with pictorial harmony as a painting by Whistler or Albert Moore - a Nocturne in blue and silver perhaps. Despite its traditional use of allegory, however, it is much more humanly engaging than anything by these artists. The stooping woman is both vulnerable and serene. Clearly many Victorian viewers experienced a fellow-feeling with the character, recognizing the vulnerability and aspiring to the serenity. Nor were these the genteel and cultured visitors to the Grosvenor. They were far less elevated individuals, whose own hopes and fears were much more immediate than theological doubt. Watts received a letter from a poor man who had been "down on his luck", but who told the artist he was cheered and encouraged by a reproduction of the painting, which brought him back from the brink of despair. It was said that a prostitute, who felt that "life had become unbearable", saw a photograph of Hope in a shop window. She bought it with "her few saved coppers" and gazed at it until "the message sank into her soul, and she fought her way back to a life of purity and honor".

This may seem a rather sentimental tale of moral redemption. Yet it is exactly the effect that Watts sought to achieve. While Whistler sneered at the vulgar masses who could never appreciate art, Watts had always aspired to find a universal language through which to convey his message to as many people as possible. His efforts can sometimes appear patronizing, but his sincerity is difficult to dispute. His earliest works were fairly conventional patriotic narrative paintings destined for the Houses of Parliament, but his aspirations towards public art were later manifested in the more diffuse project of the House of Life, intended as a kind of modern Sistine Chapel in which a series of symbolic images would express the spiritual progress of humanity. Hope was one of many designs envisaged for this great public display. Needless to say, it was never realized. Instead, Watts showed work at the Royal Academy and the Grosvenor, but also loaned paintings to the free Whitechapel Art Gallery run by his friends the Reverend Samuel and Henrietta Barnett.

The Barnetts were devoted to the cause of moral improvement through art, and were firm believers in the qualities of Watts' works. Their East End parishioners were not always quite so willing to be "improved" by paintings, but the couple insisted that Hope did communicate to the often impoverished and oppressed locals. It did so because it made human desolation seem beautiful, noble and morally redeemable. For one acquaintance of the Barnett's, a trade union leader, it justified his struggle to overcome injustice, despite numerous setbacks. The same message was apparently read into the painting almost a century after it was created, when the Egyptian government issued copies of it to its troops, humiliatingly defeated by the Israelis in 1967.

Watts' humanitarian aestheticism may have reached out into the twentieth century in other, more purely artistic ways. Such a widely reproduced and circulated image would certainly have been known by the young Picasso. The blue, angular body, plucking at a string, seems like the precursor to Picasso's own Blue Period paintings, such as The Old Guitarist (1903-1904), another hunched, helpless musician. Like the subject of Hope, Picasso's Blue Period characters are all outsiders, half-real, half-symbolic; both wandering performers and timeless human archetypes. They too occupy a mysterious no-man's-land between pleasure and desolation, hope and despair.

Watts would probably have recognized the connection between the young Picasso's art and his own. His style was constantly evolving. He painted at least six different versions of the composition, a common practice for him. Watts continued to rework or revise his most successful images, often with the intention of donating versions to public collections. This included the Hope now in the Tate collection, donated in 1897. His last version is little more than a sketch, painted like other late works in pulsating waves of color that seem to emanate from the figure. The lyre is barely marked, and the string not indicated. By this stage in his career Watts appears to have believed, like the Spiritualist thinkers who influenced the pioneers of abstract art, that painting could express the force of life itself in color. This spiritual hope is no longer a Tennysonian fragile string, but a pantheistic life force suffusing the image.

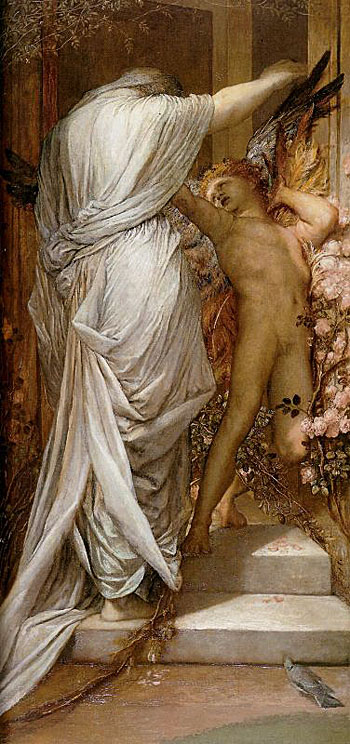

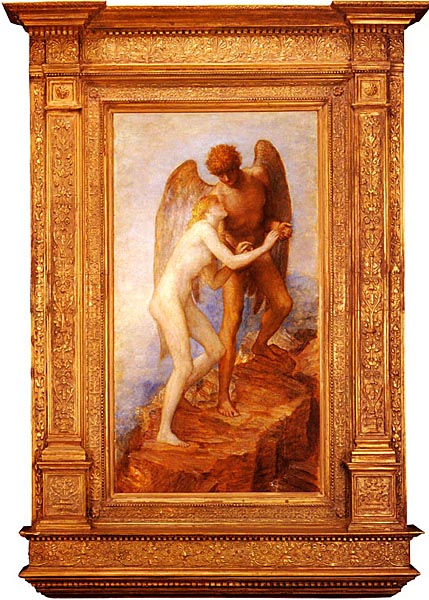

'Love and Death'

The sum of human existence reduced to two personifications struggling in a doorway.

Morris cites Watts' widow Mary as saying that there were twelve versions of this picture, of which this is apparently the original.

Watts was born in Marylebone, London, the delicate son of a poor piano-maker. He showed promise very early, learning sculpture from the age of 10 with William Behnes and enrolling as a student at the Royal Academy at the age of 18. He came to the public eye with a drawing entitled Caractacus, which was entered for a competition to design murals for the new Houses of Parliament at Westminster in 1843. Watts won a first prize in the competition, which was intended to promote narrative paintings on patriotic subjects, appropriate to the nation's legislature. In the end Watts made little contribution to the Westminster decorations, but from it he conceived his vision of a building covered with murals representing the spiritual and social evolution of humanity.

Visiting Italy in the mid-1840s, Watts was inspired by Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel and Giotto's Scrovegni Chapel, but back in Britain he was unable to obtain a building in which to carry out his plan. In consequence most of his major works are conventional oil paintings, some of which were intended as studies for the House of Life.

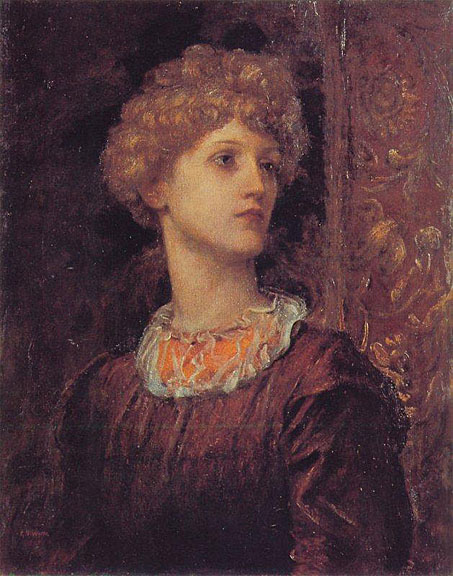

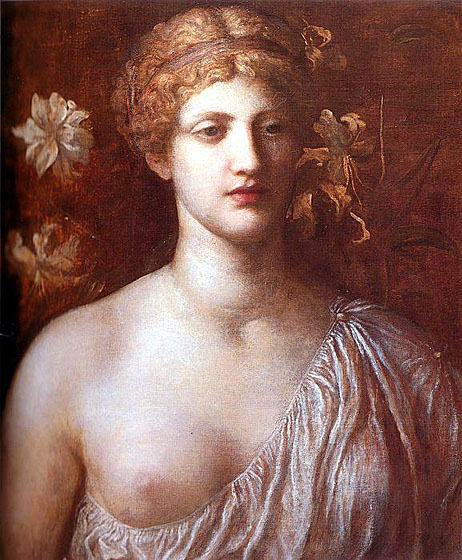

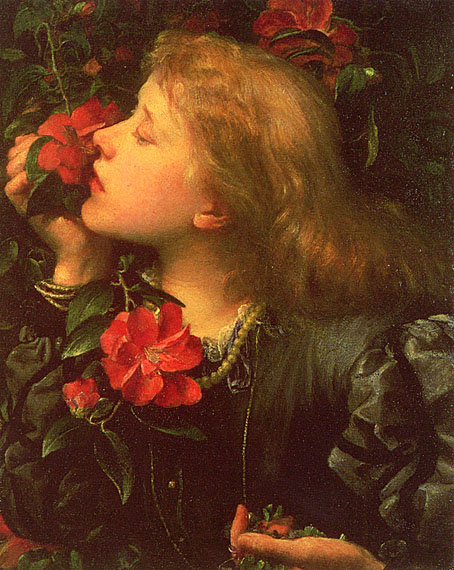

In the 1860s, Watts' work shows the influence of Rossetti, often emphasizing sensuous pleasure and rich color. Among these paintings is a portrait of his young wife, the actress Ellen Terry, who was nearly 30 years his junior - just seven days short of her 17th birthday when they married on 20 February 1864. When she eloped with another man after less than a year of marriage, Watts was obliged to divorce her (though this process was not completed until 1877). In 1886 at the age of 69 he re-married, to Mary Fraser-Tytler, a Scottish designer and potter then aged 36.

Watts's association with Rossetti and the Aesthetic Movement altered during the 1870s, as his work increasingly combined Classical traditions with a deliberately agitated and troubled surface, in order to suggest the dynamic energies of life and evolution, as well as the tentative and transitory qualities of life. These works formed part of a revised version of the house of life, influenced by the ideas of Max Müller, the founder of comparative religion. Watts hoped to trace the evolving "mythologies of the races (of the world)" in a grand synthesis of spiritual ideas with modern science especially Darwinian evolution.

In 1881, having moved to London, he set up a studio at his home at Little Holland House in Kensington, and his epic paintings were exhibited in Whitechapel by his friend and social reformer Canon Samuel Barnett. Refusing the baronetcy offered him by Queen Victoria, he later moved to a house, "Limnerslease", near Compton, south of Guildford, in Surrey.

After moving into "Limnerslease" in 1891, Watts and his wife Mary arranged the building of the Watts Gallery nearby, a museum dedicated to his work -- the first (and now the only) purpose-built gallery in Britain devoted to a single artist -- which opened in April 1904, shortly before his death. Watts's wife Mary designed the nearby Mortuary Chapel. Many of his paintings are also held at the Tate Gallery - he donated 18 of his symbolic paintings to the Tate in 1897, and three more in 1900. He was elected as an Academician to the Royal Academy in 1867 and accepted the Order of Merit in 1902.

In his late paintings, Watts' creative aspirations mutate into mystical images such as The Sower of the Systems, in which Watts seems to anticipate abstract art. This painting depicts God as a barely visible shape in an energized pattern of stars and nebulae. Some of Watts' other late works also seem to anticipate the paintings of Picasso's Blue Period.

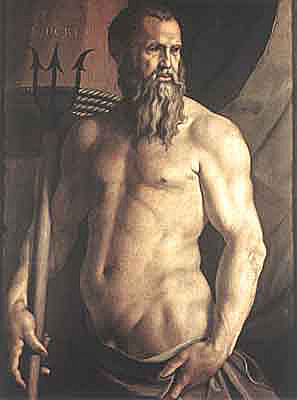

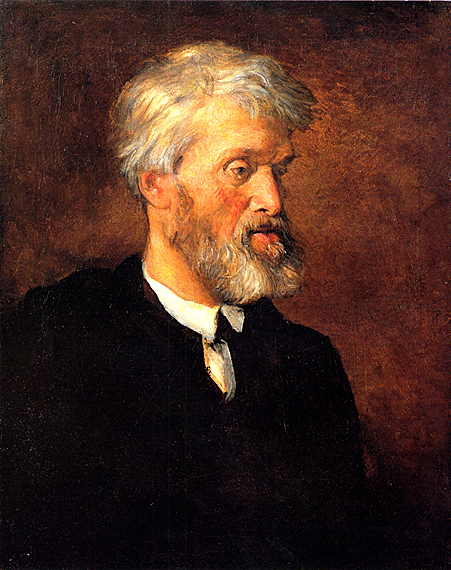

Watts was also admired as a portrait painter. His portraits were of the most important men and women of the day, intended to form a "House of Fame". Many of these are now in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery - 17 were donated in 1895, with more than 30 more added subsequently. In his portraits Watts sought to create a tension between disciplined stability and the power of action. He was also notable for emphasizing the signs of strain and wear on his sitter's faces. Sitters included Charles Dilke, Thomas Carlyle and William Morris.

During his last years Watts also turned to sculpture. His most famous work, the large bronze statue Physical Energy, depicts a naked man on horseback shielding his eyes from the sun as he looks ahead of him. It was originally intended to be dedicated to Muhammad, Attila, Tamerlane and Genghis Khan, thought by Watts to epitomize the raw energetic will to power. A cast was placed at Rhodes Memorial in Cape Town, South Africa honoring the grandiose imperial vision of Cecil Rhodes. Watts' essay "Our Race as Pioneers" indicates his support for imperialism, which he believed to be a progressive force. There is also a casting of this work in London's Kensington Gardens, overlooking the north-west side of the Serpentine.

Several reverent biographies of Watts were written shortly after his death. With the emergence of Modernism, however, his reputation declined. Virginia Woolf's comic play Freshwater portrays him in a satirical manner; an approach also adopted by Wilfred Blunt, former curator of the Watts Gallery, in his irreverent 1975 biography England's Michelangelo. On the centenary of his death Veronica Franklin Gould published G.F. Watts: The Last Great Victorian, a much more positive study of his life and work.

Blunt was succeeded as curator of the Watts Gallery by Richard Jefferies, one of the foremost authorities on Watts, who retired at the end of March 2006, to be replaced by Mark Bills.

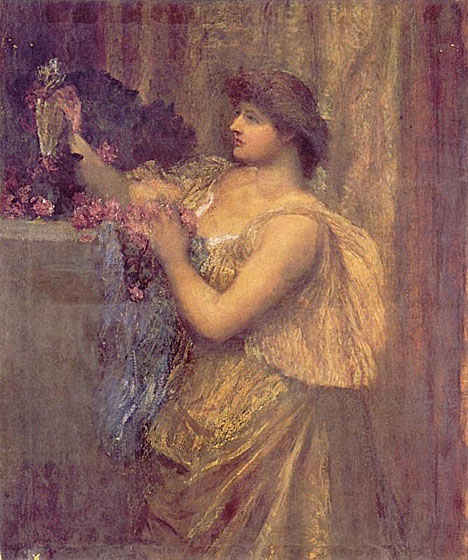

Watts painted two portraits of Dorothy Dene and she served as the model for several of his subject pictures, for example, 'Uldra' (1884). Mrs Barrington, friend and biographer of both Leighton and Watts, had sent Dorothy to her neighbour in Kensington. She recorded that Leighton always felt dissatisfied with his efforts at capturing his model's likeness, whereas Watts, 'in a couple of hours, produced a head of Dorothy Dene which was, as a mere portrait of her, more like than any Leighton ever achieved'.

The version most widely known today is based on the Brothers Grimm version. It is about a girl called Little Red Riding Hood, after the red hood (which is attached to a cape or cloak in some versions of the story) she always wears. The girl walks through the woods to deliver food to her sick grandmother. A wolf wants to eat the girl but is afraid to do so in public. He approaches the girl, and she naïvely tells him where she is going. He suggests the girl pick some flowers, which she does. In the meantime, he goes to the grandmother's house and gains entry by pretending to be the girl. He swallows the grandmother whole, and waits for the girl, disguised as the grandmother. When the girl arrives, he swallows her whole too. A hunter, however, comes to the rescue and cuts the wolf open. Little Red Riding Hood and her grandmother emerge unharmed. They fill the wolf's body with heavy stones, which kill him. Other versions of the story have had the grandmother shut in the closet instead of eaten, and some have Little Red Riding Hood saved by the hunter as the wolf advances on her rather than after she is eaten.

The tale makes the clearest contrast between the safe world of the village and the dangers of the forest, conventional antitheses that are essentially medieval, though no versions are as old as that. It also seems to be a strong morality tale, teaching children not to "wander off the path".

Interpretations and, I am sure, you could up with one of your own. Remember, beware of the 'Big Bad Wolf' no matter what its sex happens to be.

The tale has been interpreted as a puberty ritual, stemming from a pre-historical origin (sometimes an origin stemming from a previous matriarchal era.) The girl, leaving home, enters a threshold state and by going through the acts of the tale, is transformed into an adult woman by the act of coming out of the wolf's belly.

Red Riding Hood has also been seen as a parable of sexual maturity. In this interpretation, the red cloak symbolizes the blood of the menstrual cycle, braving the "dark forest" of womanhood. Or the cloak could symbolize the hymen (earlier versions of the tale generally do not state that the cloak is red-the word "red" in the title may refer to the girl's hair color or a nickname). In this case, the wolf threatens the girl's virginity. The anthropomorphic wolf symbolizes a man, who could be a lover, seducer or sexual predator.

He collected his early writings, first published in periodicals, into Poems, which were published to some acclaim in 1851. His wife left him and their five-year old son in 1858; she died three years later. Her departure was the inspiration for The Ordeal of Richard Feverel, his first "major novel".

He married Marie Vulliamy in 1864 and settled in Surrey. He continued writing novels, and later in life he returned to writing poetry, often inspired by nature. Oscar Wilde, in his dialogue The Decay Of Lying, implies that Meredith, along with Balzac, is his favorite novelist, saying "Ah, Meredith! Who can define him? His style is chaos illumined by flashes of lightning".

Before his death, Meredith was honored from many quarters: he succeeded Lord Tennyson as president of the Society of Authors; in 1905 he was appointed to the Order of Merit by King Edward VII.

In 1909 he died at home in Box Hill, Surrey.

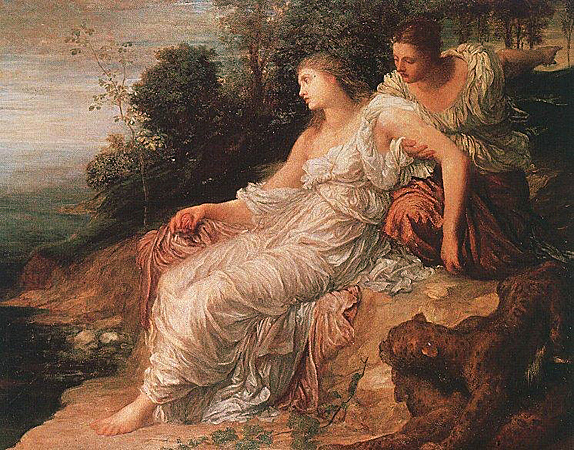

.jpg)

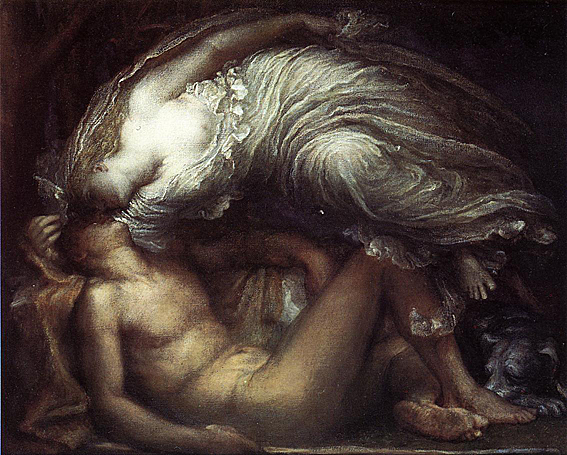

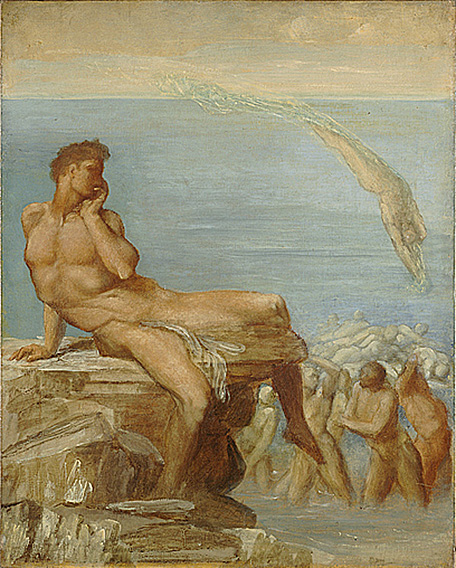

The present picture is a version of the Orpheus and Eurydice exhibited in the 1869 summer exhibition of the Royal Academy (Forbes Collection, London & New York). As with most subjects that gripped his imagination, Watts treated it several times, refining the composition until it fully realized his ideal. The exhibited painting was preceded by a sketchier version (Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool) and there is a further version in the Fogg Art Museum (Cambridge, Massachusetts).

The version here is probably the culmination of Watts' experiments with a horizontal format and half-length figures. Subtle refinements to the poses of the figures particularly that of Orpheus have enhanced their power and expressiveness. Watts painted 'Orpheus and Eurydice' on later occasions, but after 1872 he used a vertical format and full-length figures. The relationship between the present picture and a drawing in Sir Brinsley Ford's collection suggests that it is important as a transition between the two formats. This has led me to date the present painting to 1870-1872. although it has descended in the artist's family, it is not listed in the manuscript catalogue compiled by the artist's widow (three volumes, Watts Gallery, Compton) from which information about the other versions are drawn. However, this has many lacunae, especially regarding paintings produced before 1886, the date of the artist's second marriage. It is probable that, as he re-thought the composition, Watts set aside this painting, and it is possible that it was in storage and overlooked when the catalogue was compiled.

The story of Orpheus is recounted in many ancient sources. The most accessible account, and probably the one used by Watts, is found in Ovid's Metamorphoses (book X). Orpheus, the Thracian poet, descended to Hades to reclaim his wife who had died of a snake-bite. His musical skill stayed the torments of hell and so charmed Pluto and Persephone that they granted his request on condition that he did not look back at his wife as she followed him from Hades.

And now they were not far from the verge of the upper earth. He, enamored, fearing lest she should flag

and impatient to behold her, turned his eyes; and immediately she sank back again. She, hapless one!

both stretching out her arms and struggling to be grasped and to grasp him, caught nothing but the

fleeting air. And now, dying a second time, she did not at all complain of her husband; for why should she

complain of being beloved?

those spirits left the ranks where Dido suffers,

approaching us through the malignant air;

so powerful had been my loving cry.

"O living being, gracious and benign,

who through the darkened air have come to visit

our souls that stained the world with blood, if He

who rules the universe were friend to us,

then we should pray to Him to give you peace,

for you have pitied our atrocious state.

Whatever pleases you to hear and speak

will please us, too, to hear and speak with you,

now while the wind is silent, in this place.

The land where I was born lies on that shore

to which the Po together with the waters

that follow it descends to final rest.

Love, that can quickly seize the gentle heart,

took hold of him because of the fair body

taken from me- how that was done still wounds me.

Love, that releases no beloved from loving,

took hold of me so strongly that through his beauty

that, as you see, it has not left me yet.

Love led the two of us unto one death.

Caina waits for him who took our life."

These words were borne across from them to us.

When I had listened to those injured souls,

I bent my head and held it low until

the poet asked of me: "What are you thinking?"

When I replied, my words began: "Alas,

how many gentle thoughts, how deep a longing,

had led them to the agonizing pass!"

Then I addressed my speech again to them,

and I began: "Francesca, your afflictions

move me to tears of sorrow and of pity.

But tell me, in the time of gentle sighs,

with what and in what way did Love allow you

to recognize your still uncertain longings?"

And she to me: "There is no greater sorrow

than thinking back upon a happy time

in misery- and this your teacher knows.

Yet if you long so much to understand

the first root of our love, then I shall tell

my tale to you as one who weeps and speaks.

One day, to pass the time away, we read

of Lancelot- how love had overcome him.

We were alone, and we suspected nothing.

And time and time again that reading led

our eyes to meet, and made our faces pale,

and yet one point alone defeated us.

When we had read how the desired smile

was kissed by one who was so true a lover,

this one, who never shall be parted from me,

while all his body trembled, kissed my mouth.

A Gallehault indeed, that book and he

who wrote it, too; that day we read no more."

And while one spirit said these words to me,

the other wept, so that- because of pity-

I fainted, as if I had met my death.

And then I fell as a dead body falls.

Dante, InfernoV.82-142

Translated by Allen Mandelbaum

Paolo and Francesca were historical contemporaries of Dante. Francesca's father, Guido da Polenta, lord of Ravenna had waged a long war with Malatesta, lord of Rimini. Finally peace was made through intermediaries, and to make it more firm, they decided to cement it with a marriage. Guido would give his beautiful young daughter Francesca in marriage to Gianciotto, eldest son of Malatesta. Though Gianciotto was very capable and expected to become ruler when his father died, he was ugly and deformed. Guido's friends informed him that if Francesca sees Gianciotto before the marriage, she would never go through with it. So they sent Gianciotto's younger brother Paolo to Ravenna with a full mandate to marry Francesca in Gianciotto's name. Paolo was a handsome, pleasing, very courteous man, and Francesca fell in love the moment she saw him. The deceptive marriage contract was made, and Francesca went to Rimini. She was not aware of the deception until the morning after the wedding day, when she saw Gianciotto getting up from beside her. When she realized she had been fooled, she became furious. In any case, the feelings of Paolo and Francesca for each other were still very much alive when Gianciotto went off to a nearby town on business. With almost no fear of suspicion, they became intimate. Gianciotto's servant found them out, and told his master all he knew. Gianciotto returned secretly to Rimini and went to Francesca's room. Since it was bolted from within, he shouted to her and pushed against the door. Paolo and Francesca recognized his voice, and Paolo pointed to a trapdoor that led to a room below. He told Francesca to go open the door as he planned his escape. As he jumped through, a fold of his jacket got caught on a piece of iron attached to the wood. Francesca had already opened the door for Gianciotto, thinking she would be able to make excuses, now that Paolo was gone. When Gianciotto entered and noticed Paolo caught by his jacket. He ran, rapier in hand, to kill him. Seeing this, Francesca quickly ran between them, to try to prevent it. But Gianciotto's rapier was already on its way down. Before reaching Paolo, the blade passed through Francesca's bosom. Gianciotto, completely beside himself because of this accident- for he loved the woman more than himself- withdrew the blade, struck Paolo again, and killed him. Leaving them both dead, he left, and returned to his duties. The next morning, amidst much weeping, the two lovers were buried in the same tomb.

Charles Singleton,

Commentary: Dante's Inferno(1977)

I looked, and there before me was a white horse! Its rider held a bow, and he was given a crown, and he rode out as a conqueror bent on conquest.

When the Lamb opened the second seal, I heard the second living creature say, "Come!"

Then another horse came out, a fiery red one. Its rider was given power to take peace from the earth and to make men slay each other. To him was given a large sword.

When the Lamb opened the third seal, I heard the third living creature say, "Come!"

I looked, and there before me was a black horse! Its rider was holding a pair of scales in his hand.

Then I heard what sounded like a voice among the four living creatures, saying, "A quart of wheat for a day's wages, and three quarts of barley for a day's wages, and do not damage the oil and the wine!"

When the Lamb opened the fourth seal, I heard the voice of the fourth living creature say, "Come!"

I looked, and there before me was a pale horse! Its rider was named Death, and Hades was following close behind him.

They were given power over a fourth of the earth to kill by sword, famine and plague, and by the wild beasts of the earth.

The first rider represents the lust for conquest and as such forms an integral part of the four horsemen who are all evil and are summed up by the fourth horsemen. Conquest brings with it war, famine and death. However the color white is usually associated with good not evil, but it can indicate victory, the rider wears the victory crown.

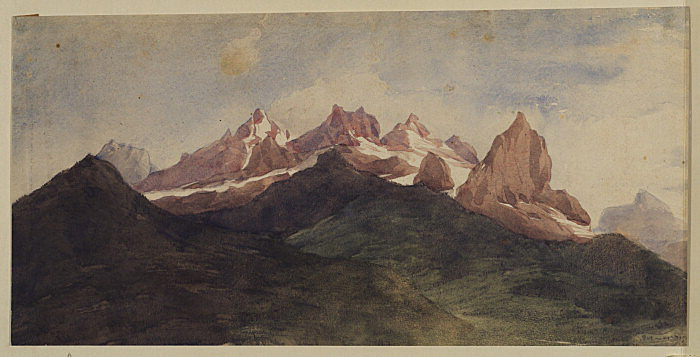

This is an apparently unrecorded example of the landscape that Watts painted early in his career when staying in Italy with Lord Holland, British Minister to the Court of Tuscany. Having won a premium of œ300 in the first competition to find artists capable of decorating the new Palace of Westminster, held in 1843, Watts had set out for Italy to study the great masters of the Italian Renaissance and the fresco technique. He was introduced to the Hollands in Florence and they invited him to stay at the Casa Feroni, where he became an essential element in Lady Holland's salon, thus begining his career as a 'tame' artist or 'genius in residence', later to be continued at Little Holland House. He painted or drew many members of the Hollands' circle, while at Villa Medici, their country retreat at Careggi two or three miles north of Florence, he embarked on a fresco showing Lorenzo de Medici's attendants drowning his doctor in a well. Lorenzo had died at the villa in 1492, and his doctor was suspected of administering poison. While working on the fresco in the spring of 1845, Watts in the words of Lord Ilchester, took 'a violent fancy for landscape (which) diverted him from his strict objective'. It has been suggested that this was a response to the first volume of Ruskin's ' Modern Painters ', published in 1843. The best-known product of the 'fancy' is ' Fiesole ' (Watts Gallery, Compton), painted from the gallery under the roof of the villa, and there is a view looking in the opposite direction, showing another Medici villa, 'Petraia'. Another example, Mountain landscape is very close to the present lot. While precise dates cannot be assigned to Watts' Italian landscapes, they must all have been executed before his return to London in the spring of 1847 to enter another of the Westminster competitions. Quite apart from their subjects, they form a homogeneous and distinctive group, being more fluently handled and topographically more specific than his later essays in this field. At the same time they anticipate many of the later landscapes in being panoramic in scope. Watts' habit of painting from high vantage points in Italy in the 1840's seems to have established a pattern for his latter landscape pictures.

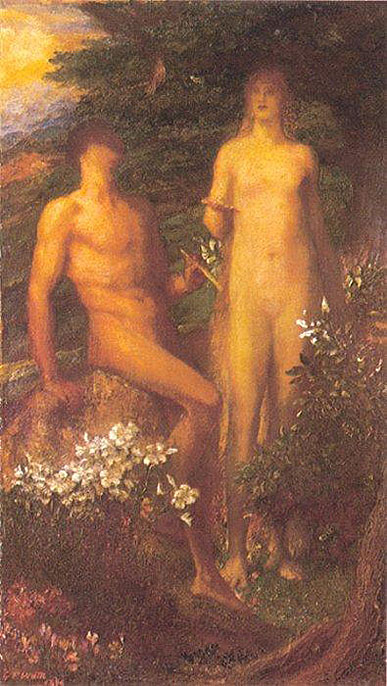

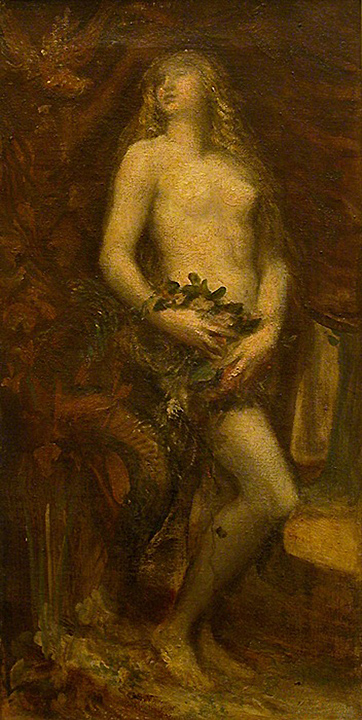

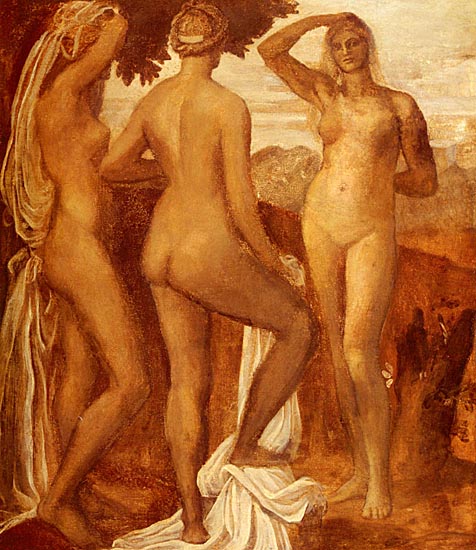

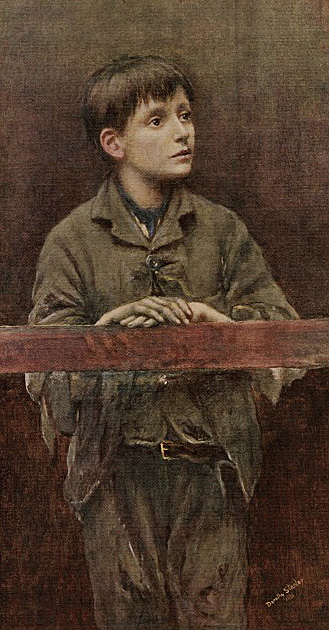

"Watts originally conceived these as being part of the House of Life sequence of paintings, but they later evolved into these three large powerful compositions."

"I think in terms of Watts' own mythology, these readdress the idea of the evolution of the human soul, of the human body. So it's really the emergence of consciousness. And it's quite interesting in these paintings how the content of the theme is paralleled by Watts' very innovative technique."

"To take the central panel, She Shall be Called Woman. This is a very powerful picture. And it shows Eve's really ascension to life. It's almost like a rocket taking off into outer space. You have all this smoke billowing out around her, and you almost feel the form is evaporating or dissolving, as much as it's actually coming together."

"I think it's the idea of spirit or energy merging into flesh. He's trying to really show that moment of impact when just energy or atoms or whatever become something solid. And so you have the figure of Eve sort of shooting up towards the sun. And around her you have these wonderful trails of lilies and flowers and birds. So there's an enormous explosion of light and color to really show the glory of this moment of creation."

"The other two paintings I think you should really see like a triptych either side of the central She Shall be Called Woman. And they are more heavy in terms of representation of the female figure. In Eve Tempted, for example, it's a very masculine depiction of the female form. Watts when he painted the nude didn't actually pay particular attention to the model which explains the rather peculiar anatomy, if for example you look at her enormous shoulders, or the way the arms actually interlock with the shoulders, it can be seen as rather awkward. But I think that's deliberate on his part."

"I think he was influenced in this work particularly by Venetian painting, also by Michelangelesque sculpture, as well as by the sculpture of ancient Greece. So it's quite sculptural in the way the figure moves. And I think he wants to get this dynamic contraposto into the pose, to show how she is intoxicated by this wonderful profusion of flowers around."

"And of course the cheetah rolling on the ground accentuates that idea of sensual pleasure. She's really giving in to the senses. She's totally succumbing to it. And I think to that end he wanted to create a sensual image, but he justifies it in terms of a narrative, because it's the moment when Eve is tempted."

"Eve Repentant can be seen as a parallel to Eve Tempted. This shows Eve after the fall, reclining against a tree, totally abandoned in grief. And the compositional lines all drag down downwards. I think it's the idea that these downward lines really correspond to the nature of her grief and her despair. So I think it's a painting which communicates through abstract elements, with the dark colours, her illuminated form, and these descending lines."

"I think Watts is quite a difficult artist to like. If one has to live with a painting by Watts, they're quite sort of; they're quite heavy, quite didactic. The paint surfaces aren't immediately attractive to the eye. But they are very powerful compositions. I think he's an artist who repays careful study."

"I don't think Watts perhaps appeals at first sight. I think the more you get into his subject matter, his technique, the more you see his paintings perhaps assembled as a whole, and see these correspondences between different works, I think the impact they were intended to have, like a great work of music, with different themes and variations, building up upon one another, totaling one grand symphonic statement, I think in those terms they're monumental and very powerful pieces."

Did Sir Percival find the Holy Grail? Almost!

On his journey to find the Holy Grail, Sir Percival came upon a spectacular yet mysterious ship, owned by a most beautiful woman. Sir Percival, of course, fell immediately in love with her.

Just at the moment where he was entering her bed to consummate their love, Sir Percival saw his unsheathed sword lying on the floor. On its pommel was a red cross - the sign of the crucifixion - which reminded him of his knightly duties and his holy quest. Ashamed, Sir Percival quickly made the sign of the cross in repentance. Suddenly, the ship transformed into a massive cloud of black smoke, and the beautiful woman, the temptress who tried to lure him away from his holy quest, turned vile and ugly and "set off with the wind roaring and yelling that it seemed all the water was burned after her". Deeply disappointed in himself for his moral lapse, Sir Percival punished himself by stabbing his thigh.

Later on his journey, he met up with two other knights, and together they entered the presence of the Holy Grail. Sir Percival was permitted this holy glimpse because of his purity and innocence, but he was denied the full vision of the Grail and its holy, heavenly release from the bonds of earth because of his moral lapse with the temptress on the ship. He did, however, receive profound spiritual nourishment from the Grail. And returning from Sarras, Sir Percival became the Grail King, heading the Order of Grail Knights.

In the catalogue to the 1896 retrospective of his work, Watts suggested that this ethereal figure 'may be vaguely called conscience... on her lap lie the arrows that pierce through all disguise, and the trumpet which proclaims truth to the world'.

Like Michelangelo's sibyls on the Sistine Chapel ceiling, Watts' figure appears monumental and androgynous, qualities which suggest a higher knowledge of the universe.

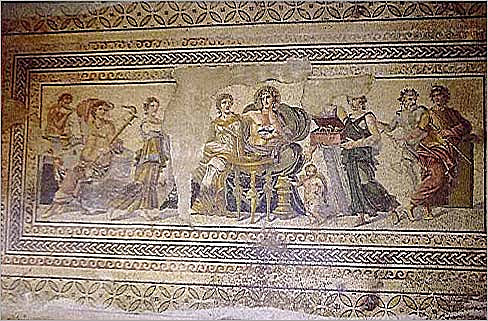

Hesiod, The Theogony

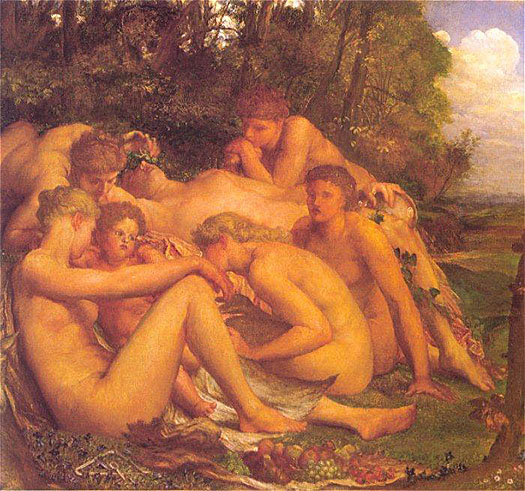

In Greek mythology, the Charities were the graces. Ordinarily they were three: Aglaea, the youngest, Euphrosyne and Thalia, but others are sometimes mentioned, including Auxo, Charis, Hegemone, Phaenna, and Pasithea.

They were the daughters of Zeus and Eurynome, usually, though also said to be daughters of Dionysus and Aphrodite or of Helios and the Naiad Aegle. Homer claimed they were part of the retinue of Aphrodite. Their Roman equivalent was the Gratiae.

The Charities were the goddesses of charm, beauty, nature, human creativity and fertility. They were great lovers of beauty and gave humans talents in the arts, closely associated with the Muses. The Charities were associated with the underworld and the Eleusinian Mysteries.

The river Cephissus near Delphi was sacred to them.

Pausanias, interrupts his Description of Greece (book 9.xxxv.1 - 7) to expand upon the various conceptions of the Graces that obtained in different parts of mainland Greece and Ionia:,P. "The Boeotians say that Eteocles was the first man to sacrifice to the Graces. Moreover, they are aware that he established three as the number of the Graces, but they have no tradition of the names he gave them. The Lacedaemonians, however, say that the Graces are two, and that they were instituted by Lacedaemon, son of Taygete, who gave them the names of Cleta and Phaenna. These are appropriate names for Graces, as are those given by the Athenians, who from of old have worshipped two Graces, Auxo and Hegemone... It was from Eteocles of Orchomenus that we learned the custom of praying to three Graces. And Angelion and Tectaus, sons of Dionysus, who made the image of Apollo for the Delians, set three Graces in his hand. Again, at Athens, before the entrance to the Acropolis, the Graces are three in number; by their side are celebrated mysteries which must not be divulged to the many. Pamphos was the first we know of to sing about the Graces, but his poetry contains no information either as to their number or about their names. Homer (he too refers to the Graces ) makes one the wife of Hephaestus, giving her the name of Grace. He also says that Sleep was a lover of Pasithea, and in the speech of Sleep there is this verse:

Verily that he would give me one of the younger Graces.

Aphrodite was curious so she visited the studio of the sculptor while he was away and was charmed by his creation. Galatea was the image of herself. Being flattered, Aphrodite brought the statue to life. When Pygmalion returned to his home, he found Galatea alive, and humbled himself at her feet. Pygmalion and Galatea were wed, and Pygmalion never forgot to thank Aphrodite for the gift she had given him. He and Galatea brought gifts to her temple throughout their life and Aphrodite blessed them with happiness and love in return.

Ariadne was often depicted alongside Dionysus in Greek vase painting: either amongst the gods of Olympus, or in Bacchic scenes surrounded by dancing Satyrs and Maenads. The discovery of the sleeping Ariadne on Naxos was also a popular scene in both vase painting and mosaic.

According to the story told in the Metamorphoses, Psyche was the youngest daughter of a king (incidentally, she had two older sisters). Psyche was so stunningly beautiful that her appearance rivaled that of a goddess. Indeed, the simple people of her county were so in awe of Psyche's grace and beauty that they stopped worshipping Aphrodite (the real goddess) and paid their honors instead to the daughter of a king. In her defense, it should be noted that Psyche was a modest girl, and she resisted this improper attention. However, the damage had been done - Aphrodite took notice of this insult of being overthrown in popularity by a mere mortal, so the goddess decided to punish her rival. And her punishment was swift and severe. Aphrodite commanded her son Eros to do her dirty work in this situation, and insisted that Eros use his powers as the god of desire to make Psyche fall in love with the most terrible and grotesque thing on earth.

As fate would have it, Eros fell victim to Psyche's beauty himself. He simply could not resist her charms. However, loving the mortal girl meant disobeying his powerful mother and making Aphrodite angry - and no one wants to anger a goddess. But Love will find a way.

Eros thought of a cunning plan to win Psyche for himself while keeping his mother Aphrodite ignorant of his actions. The god of love and desire arranged to have Psyche brought to a desolate area. Here, the innocent girl was told, she would become the bride of an evil being. Psyche waited for her doom dressed in a wedding gown. In time, Zephyrus led her gently into a valley in which a majestic and grand palace dominated the landscape. The girl was awed by the magical palace, but she soon found that this place was her new home.

Clever Eros then came to Psyche when she had gone to bed that night. The bedroom was dark - too dark to see anything - when the god of love entered. Eros used the darkness to his advantage in order to conceal his identity from the girl. He whispered in Psyche's ear that he was her husband and that she must not under any circumstances look upon him or seek to know who he was.

Psyche enjoyed her life with her unseen husband, but for one minor detail - she came to feel isolated and homesick. She begged to see her sisters. Although Eros did not want to comply, he could not deny his beloved anything. So Psyche's sisters were invited to the palace. Once there, they saw the grand lifestyle of their younger sister and quickly became jealous of Psyche's good fortune. Together the pair of sisters persuaded Psyche that her husband was dangerous and that she must rid herself of him immediately. And Psyche, innocent and trusting girl that she was, believed the horrible stories told by her sisters.

When she next went to bed, Psyche took with her a lamp, which she lit when she was assured her husband was asleep. When Psyche gazed upon the god, however, she was stunned by the grace and perfection of his divine features - he was definitely no monster! In her surprise she let a drop of oil fall from the lamp, and this woke Eros. Realizing what had happened, Eros immediately departed.

Psyche was beside herself with grief. She was now alone and abandoned by her husband. She searched for her lost love, but could not find him anywhere. In desperation Psyche asked the goddesses Demeter and Hera for assistance, but neither goddess was willing to risk the wrath of Aphrodite. So finally, left with no other options, Psyche went to see Aphrodite herself.

Aphrodite decided to punish the girl a bit more. Psyche - the daughter of a king - was made into a slave by the goddess of love. And indeed, Aphrodite added insult to injury by requiring Psyche to perform tasks that seemed impossible. For example, Psyche had to sort, grain by grain, an entire room full of seeds in the span of a single day. This task might well have been impossible if it had not been for the help of some industrious ants - with their assistance, Psyche achieved her goal.

One other fiendishly devious task assigned by Aphrodite was that Psyche must fetch a jar that contained beauty from Persephone. Now, Persephone was the Queen of the Underworld, which meant that (at least part of the year) she lived and ruled in the gloomy realm of the dead. Naturally, Psyche despaired of accomplishing this goal. But in the end, she was given instructions on how to descend to the Underworld while still alive and approach Persephone.

In the meantime, Eros suffered from the separation from his beloved as well. He finally went to Zeus to beg for mercy. Zeus listened to the story that Eros told, and decided to grant the god of love's wish - that the couple should be reunited and joined in marriage. And this is exactly what happened. In the end, Eros and Psyche were allowed to be together and Aphrodite gave up her anger in order to welcome her new daughter in law into the family.

It is also worth noting that the word psyche means soul in Greek.

O sweet illusions of song

That tempt me everywhere,

In the lonely fields, and the throng

Of the crowded thoroughfare!

I approach and ye vanish away,

I grasp you, and ye are gone;

But ever by night and by day,

The melody soundeth on.

As the weary traveller sees

In desert or prairie vast,

Blue lakes, overhung with trees

That a pleasant shadow cast;

Fair towns with turrets high,

And shining roofs of gold,

That vanish as he draws nigh,

Like mists together rolled

So I wander and wander along,

And forever before me gleams

The shining city of song,

In the beautiful land of dreams.

But when I would enter the gate

Of that golden atmosphere,

It is gone, and I wonder and wait

For the vision to reappear.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

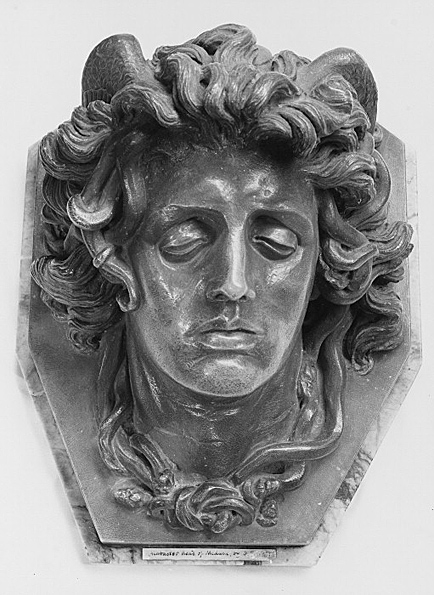

Watts shows her metamorphosing into a flower, while also suggesting movement over time through the musculature and torsion of the body. He said he wanted to get an impression of color, by which he meant the variation of light and shade across the surface of the sculpture.

In this marble bust laurel leaves surround her body, suggesting the transition from flesh to branches. The unfinished appearance of the work, with the marks of the claw-chisel still visible, reinforces the idea of transformation.

INSCRIBED TO THE MEMORY OF THOMAS CHATTERTON

PREFACE

KNOWING within myself the manner in which this Poem has been produced, it is not without a feeling of regret that I make it public.

What manner I mean, will be quite clear to the reader, who must soon perceive great inexperience, immaturity, and every error denoting a feverish attempt, rather than a deed accomplished. The two first books, and indeed the two last, I feel sensible are not of such completion as to warrant their passing the press; nor should they if I thought a year's castigation would do them any good;- it will not: the foundations are too sandy. It is just that this youngster should die away: a sad thought for me, if I had not some hope that while it is dwindling I may be plotting, and fitting myself for verses fit to live.

This may be speaking too presumptuously, and may deserve a punishment: but no feeling man will be forward to inflict it: he will leave me alone, with the conviction that there is not fiercer hell than the failure in a great object. This is not written with the least atom of purpose to forestall criticisms of course, but from the desire I have to conciliate men who are competent to look, and who do look with a zealous eye, to the honor of English literature.

The imagination of a boy is healthy, and the mature imagination of a man is healthy; but there is a space of life between, in which the soul is in a ferment, the character undecided, the way of life uncertain, the ambition thick-sighted: thence proceeds mawkishness, and all the thousand bitters which those men I speak of must necessarily taste in going over the following pages.

I hope I have not in too late a day touched the beautiful mythology of Greece and dulled its brightness: for I wish to try once more, before I bid it farewell.

April 10, 1818

BOOK I

A thing of beauty is a joy for ever:

Its loveliness increases; it will never

Pass into nothingness; but still will keep

A bower quiet for us, and a sleep

Full of sweet dreams, and health, and quiet breathing.

Therefore, on every morrow, are we wreathing

A flowery band to bind us to the earth,

Spite of despondence, of the inhuman dearth

Of noble natures, of the gloomy days,

Of all the unhealthy and o'er-darkened ways

Made for our searching: yes, in spite of all,

Some shape of beauty moves away the pall

From our dark spirits. Such the sun, the moon

,

Trees old, and young, sprouting a shady boon

For simple sheep; and such are daffodils

With the green world they live in; and clear rills

That for themselves a cooling covert make

'Gainst the hot season; the mid forest brake,

Rich with a sprinkling of fair musk-rose blooms:

And such too is the grandeur of the dooms

We have imagined for the mighty dead;

All lovely tales that we have heard or read:

An endless fountain of immortal drink,

Pouring unto us from the heaven's brink.

Nor do we merely feel these essences

For one short hour; no, even as the trees

That whisper round a temple become soon

Dear as the temple's self, so does the moon,

The passion poesy, glories infinite,

Haunt us till they become a cheering light

Unto our souls, and bound to us so fast,

That, whether there be shine, or gloom o'ercast,

They alway must be with us, or we die.

Therefore, 'tis with full happiness that I

Will trace the story of Endymion.

The very music of the name has gone

Into my being, and each pleasant scene

Is growing fresh before me as the green

Of our own vallies: so I will begin

Now while I cannot hear the city's din;

Now while the early budders are just new,

And run in mazes of the youngest hue

About old forests; while the willow trails

Its delicate amber; and the dairy pails

Bring home increase of milk. And, as the year

Grows lush in juicy stalks, I'll smoothly steer

My little boat, for many quiet hours,

With streams that deepen freshly into bowers.

Many and many a verse I hope to write,

Before the daisies, vermeil rimm'd and white,

Hide in deep herbage; and ere yet the bees

Hum about globes of clover and sweet peas,

I must be near the middle of my story.

O may no wintry season, bare and hoary,

See it half finish'd: but let Autumn bold,

With universal tinge of sober gold,

Be all about me when I make an end.

And now at once, adventuresome, I send

My herald thought into a wilderness:

There let its trumpet blow, and quickly dress

My uncertain path with green, that I may speed

Easily onward, thorough flowers and weed.

Upon the sides of Latmos was outspread

A mighty forest; for the moist earth fed

So plenteously all weed-hidden roots

Into o'er-hanging boughs, and precious fruits.

And it had gloomy shades, sequestered deep,

Where no man went; and if from shepherd's keep

A lamb stray'd far a-down those inmost glens,

Never again saw he the happy pens

Whither his brethren, bleating with content,

Over the hills at every nightfall went.

Among the shepherds, 'twas believed ever,

That not one fleecy lamb which thus did sever

From the white flock, but pass'd unworried

By angry wolf, or pard with prying head,

Until it came to some unfooted plains

Where fed the herds of Pan: aye great his gains

Who thus one lamb did lose. Paths there were many,

Winding through palmy fern, and rushes fenny,

And ivy banks; all leading pleasantly

To a wide lawn, whence one could only see

Stems thronging all around between the swell

Of turf and slanting branches: who could tell

The freshness of the space of heaven above,

Edg'd round with dark tree tops? through which a dove

Would often beat its wings, and often too

A little cloud would move across the blue.

Full in the middle of this pleasantness

There stood a marble altar, with a tress

Of flowers budded newly; and the dew

Had taken fairy phantasies to strew

Daisies upon the sacred sward last eve,

And so the dawned light in pomp receive.

For 'twas the morn: Apollo's upward fire

Made every eastern cloud a silvery pyre

Of brightness so unsullied, that therein

A melancholy spirit well might win

Oblivion, and melt out his essence fine

Into the winds: rain-scented eglantine

Gave temperate sweets to that well-wooing sun;

The lark was lost in him; cold springs had run

To warm their chilliest bubbles in the grass;

Man's voice was on the mountains; and the mass

Of nature's lives and wonders puls'd tenfold,

To feel this sun-rise and its glories old.

Now while the silent workings of the dawn

Were busiest, into that self-same lawn

All suddenly, with joyful cries, there sped

A troop of little children garlanded;

Who gathering round the altar, seem'd to pry

Earnestly round as wishing to espy

Some folk of holiday: nor had they waited

For many moments, ere their ears were sated

With a faint breath of music, which ev'n then

Fill'd out its voice, and died away again.

Within a little space again it gave

Its airy swellings, with a gentle wave,

To light-hung leaves, in smoothest echoes breaking

Through copse-clad vallies,- ere their death, o'ertaking

The surgy murmurs of the lonely sea.

And now, as deep into the wood as we

Might mark a lynx's eye, there glimmered light

Fair faces and a rush of garments white,

Plainer and plainer showing, till at last

Into the widest alley they all past,

Making directly for the woodland altar.

O kindly muse! let not my weak tongue faulter

In telling of this goodly company,

Of their old piety, and of their glee:

But let a portion of ethereal dew

Fall on my head, and presently unmew

My soul; that I may dare, in wayfaring,

To stammer where old Chaucer us'd to sing.

Leading the way, young damsels danced along,

Bearing the burden of a shepherd song;

Each having a white wicker over brimm'd

With April's tender younglings: next, well trimm'd,

A crowd of shepherds with as sunburnt looks

As may be read of in Arcadian books;

Such as sat listening round Apollo's pipe,

When the great deity, for earth too ripe,

Let his divinity o'erflowing die

In music, through the vales of Thessaly:

Some idly trail'd their sheep-hooks on the ground,

And some kept up a shrilly mellow sound

With ebon-tipped flutes: close after these,

Now coming from beneath the forest trees,

A venerable priest full soberly,

Begirt with ministring looks: alway his eye

Stedfast upon the matted turf he kept,

And after him his sacred vestments swept.

From his right hand there swung a vase, milk-white,

Of mingled wine, out-sparkling generous light;

And in his left he held a basket full

Of all sweet herbs that searching eye could cull:

Wild thyme, and valley-lillies whiter still

Than Leda's love, and cresses from the rill.

His aged head, crowned with beechen wreath,

Seem'd like a poll of ivy in the teeth

Of winter hoar. Then came another crowd

Of shepherds, lifting in due time aloud

Their share of the ditty. After them appear'd,

Up-followed by a multitude that rear'd

Their voices to the clouds, a fair wrought car,

Easily rolling so as scarce to mar

The freedom of three steeds of dapple brown:

Who stood therein did seem of great renown

Among the throng. His youth was fully blown,

Showing like Ganymede to manhood grown;

And, for those simple times, his garments were

A chieftain king's: beneath his breast, half bare,

Was hung a silver bugle, and between

His nervy knees there lay a boar-spear keen.

A smile was on his countenance; he seem'd,

To common lookers on, like one who dream'd

Of idleness in groves Elysian:

But there were some who feelingly could scan

A lurking trouble in his nether lip,

And see that oftentimes the reins would slip

Through his forgotten hands: then would they sigh,

And think of yellow leaves, of owlets' cry,

Of logs piled solemnly.- Ah, well-a-day,

Why should our young Endymion pine away!

Soon the assembly, in a circle rang'd,

Stood silent round the shrine: each look was chang'd

To sudden veneration: women meek

Beckon'd their sons to silence; while each cheek

Of virgin bloom paled gently for slight fear.

Endymion too, without a forest peer,

Stood, wan, and pale, and with an awed face,

Among his brothers of the mountain chace.

In midst of all, the venerable priest

Eyed them with joy from greatest to the least,

And, after lifting up his aged hands,

Thus spake he: "Men of Latmos! shepherd bands!

Whose care it is to guard a thousand flocks:

Whether descended from beneath the rocks

That overtop your mountains; whether come

From vallies where the pipe is never dumb;

Or from your swelling downs, where sweet air stirs

Blue hare-bells lightly, and where prickly furze

Buds lavish gold; or ye, whose precious charge

Nibble their fill at ocean's very marge,

Whose mellow reeds are touch'd with sounds forlorn

By the dim echoes of old Triton's horn:

Mothers and wives! who day by day prepare

The scrip, with needments, for the mountain air;

And all ye gentle girls who foster up

Udderless lambs, and in a little cup

Will put choice honey for a favoured youth:

Yea, every one attend! for in good truth

Our vows are wanting to our great god Pan.

Are not our lowing heifers sleeker than

Night-swollen mushrooms? Are not our wide plains

Speckled with countless fleeces? Have not rains

Green'd over April's lap? No howling sad

Sickens our fearful ewes; and we have had

Great bounty from Endymion our lord.

The earth is glad: the merry lark has pour'd

His early song against yon breezy sky,

That spreads so clear o'er our solemnity."

Thus ending, on the shrine he heap'd a spire

Of teeming sweets, enkindling sacred fire;

Anon he stain'd the thick and spongy sod

With wine, in honour of the shepherd-god.

Now while the earth was drinking it, and while

Bay leaves were crackling in the fragrant pile,

And gummy frankincense was sparkling bright

'Neath smothering parsley, and a hazy light

Spread greyly eastward, thus a chorus sang:

"O thou, whose mighty palace roof doth hang

From jagged trunks, and overshadoweth

Eternal whispers, glooms, the birth, life, death

Of unseen flowers in heavy peacefulness;

Who lov'st to see the hamadryads dress

Their ruffled locks where meeting hazels darken;

And through whole solemn hours dost sit, and hearken

The dreary melody of bedded reeds

In desolate places, where dank moisture breeds

The pipy hemlock to strange overgrowth;

Bethinking thee, how melancholy loth

Thou wast to lose fair Syrinx- do thou now,

By thy love's milky brow!

By all the trembling mazes that she ran,

Hear us, great Pan!

"O thou, for whose soul-soothing quiet, turtles

Passion their voices cooingly 'mong myrtles,

What time thou wanderest at eventide

Through sunny meadows, that outskirt the side

Of thine enmossed realms: O thou, to whom

Broad leaved fig trees even now foredoom

Their ripen'd fruitage; yellow girted bees

Their golden honeycombs; our village leas

Their fairest blossom'd beans and poppied corn;

The chuckling linnet its five young unborn,

To sing for thee; low creeping strawberries

Their summer coolness; pent up butterflies

Their freckled wings; yea, the fresh budding year

All its completions- be quickly near,

By every wind that nods the mountain pine,

O forester divine!

"Thou, to whom every faun and satyr flies

For willing service; whether to surprise

The squatted hare while in half sleeping fit;

Or upward ragged precipices flit

To save poor lambkins from the eagle's maw;

Or by mysterious enticement draw

Bewildered shepherds to their path again;

Or to tread breathless round the frothy main,

And gather up all fancifullest shells

For thee to tumble into Naiads' cells,

And, being hidden, laugh at their out-peeping;

Or to delight thee with fantastic leaping,

The while they pelt each other on the crown

With silvery oak apples, and fir cones brown

By all the echoes that about thee ring,

Hear us, O satyr king!

"O Hearkener to the loud clapping shears

While ever and anon to his shorn peers

A ram goes bleating: Winder of the horn,

When snouted wild-boars routing tender corn

Anger our huntsmen: Breather round our farms,

To keep off mildews, and all weather harms:

Strange ministrant of undescribed sounds,

That come a swooning over hollow grounds,

And wither drearily on barren moors:

Dread opener of the mysterious doors

Leading to universal knowledge- see,

Great son of Dryope,

The many that are come to pay their vows

With leaves about their brows!

"Be still the unimaginable lodge

For solitary thinkings; such as dodge

Conception to the very bourne of heaven,

Then leave the naked brain: be still the leaven,

That spreading in this dull and clodded earth

Gives it a touch ethereal- a new birth:

Be still a symbol of immensity;

A firmament reflected in a sea;

An element filling the space between;

An unknown- but no more: we humbly screen

With uplift hands our foreheads, lowly bending,

And giving out a shout most heaven rending,

Conjure thee to receive our humble Paean,

Upon thy Mount Lycean!"

Even while they brought the burden to a close,

A shout from the whole multitude arose,

That lingered in the air like dying rolls

Of abrupt thunder, when Ionian shoals

Of dolphins bob their noses through the brine.

Meantime, on shady levels, mossy fine,

Young companies nimbly began dancing

To the swift treble pipe, and humming string.

Aye, those fair living forms swam heavenly

To tunes forgotten- out of memory:

Fair creatures! whose young children's children bred

Thermopylae its heroes- not yet dead,

But in old marbles ever beautiful.

High genitors, unconscious did they cull

Time's sweet first-fruits- they danc'd to weariness,

And then in quiet circles did they press

The hillock turf, and caught the latter end

Of some strange history, potent to send

A young mind from its bodily tenement.

Or they might watch the quoit-pitchers, intent

On either side; pitying the sad death

Of Hyacinthus, when the cruel breath

Of Zephyr slew him,- Zephyr penitent,

Who now, ere Phoebus mounts the firmament,

Fondles the flower amid the sobbing rain.

The archers too, upon a wider plain,

Beside the feathery whizzing of the shaft,

And the dull twanging bowstring, and the raft

Branch down sweeping from a tall ash top,

Call'd up a thousand thoughts to envelope

Those who would watch. Perhaps, the trembling knee

And frantic gape of lonely Niobe,

Poor, lonely Niobe! when her lovely young

Were dead and gone, and her caressing tongue

Lay a lost thing upon her paly lip,

And very, very deadliness did nip

Her motherly cheeks. Arous'd from this sad mood

By one, who at a distance loud halloo'd,

Uplifting his strong bow into the air,

Many might after brighter visions stare:

After the Argonauts, in blind amaze

Tossing about on Neptune's restless ways,

Until, from the horizon's vaulted side,

There shot a golden splendour far and wide,

Spangling those million poutings of the brine

With quivering ore: 'twas even an awful shine

From the exaltation of Apollo's bow;

A heavenly beacon in their dreary woe.

Who thus were ripe for high contemplating,

Might turn their steps towards the sober ring

Where sat Endymion and the aged priest

'Mong shepherds gone in eld, whose looks increas'd

The silvery setting of their mortal star.

There they discours'd upon the fragile bar

That keeps us from our homes ethereal;

And what our duties there: to nightly call

Vesper, the beauty-crest of summer weather;

To summon all the downiest clouds together

For the sun's purple couch; to emulate

In ministring the potent rule of fate

With speed of fire-tail'd exhalations;

To tint her pallid cheek with bloom, who cons

Sweet poesy by moonlight: besides these,

A world of other unguess'd offices.

Anon they wander'd, by divine converse,

Into Elysium; vieing to rehearse

Each one his own anticipated bliss.

One felt heart-certain that he could not miss

His quick gone love, among fair blossom'd boughs,

Where every zephyr-sigh pouts, and endows

Her lips with music for the welcoming.

Another wish'd, mid that eternal spring,

To meet his rosy child, with feathery sails,

Sweeping, eye-earnestly, through almond vales:

Who, suddenly, should stoop through the smooth wind,

And with the balmiest leaves his temples bind;

And, ever after, through those regions be

His messenger, his little Mercury.

Some were athirst in soul to see again

Their fellow huntsmen o'er the wide champaign

In times long past; to sit with them, and talk

Of all the chances in their earthly walk;

Comparing, joyfully, their plenteous stores

Of happiness, to when upon the moors,

Benighted, close they huddled from the cold,

And shar'd their famish'd scrips. Thus all out-told

Their fond imaginations,- saving him

Whose eyelids curtain'd up their jewels dim,

Endymion: yet hourly had he striven

To hide the cankering venom, that had riven

His fainting recollections. Now indeed

His senses had swoon'd off: he did not heed

The sudden silence, or the whispers low,

Or the old eyes dissolving at his woe,

Or anxious calls, or close of trembling palms,

Or maiden's sigh, that grief itself embalms:

But in the self-same fixed trance he kept,

Like one who on the earth had never stept.

Aye, even as dead still as a marble man,

Frozen in that old tale Arabian.

Who whispers him so pantingly and close?

Peona, his sweet sister: of all those,

His friends, the dearest. Hushing signs she made,

And breath'd a sister's sorrow to persuade

A yielding up, a cradling on her care.

Her eloquence did breathe away the curse:

She led him, like some midnight spirit nurse

Of happy changes in emphatic dreams,

Along a path between two little streams,

Guarding his forehead, with her round elbow,

From low-grown branches, and his footsteps slow

From stumbling over stumps and hillocks small;

Until they came to where these streamlets fall,

With mingled bubblings and a gentle rush,

Into a river, clear, brimful, and flush

With crystal mocking of the trees and sky.

A little shallop, floating there hard by,

Pointed its beak over the fringed bank;

And soon it lightly dipt, and rose, and sank,

And dipt again, with the young couple's weight,

Peona guiding, through the water straight,

Towards a bowery island opposite;

Which gaining presently, she steered light

Into a shady, fresh, and ripply cove,

Where nested was an arbour, overwove

By many a summer's silent fingering;

To whose cool bosom she was used to bring

Her playmates, with their needle broidery,

And minstrel memories of times gone by.

So she was gently glad to see him laid

Under her favourite bower's quiet shade,

On her own couch, new made of flower leaves,

Dried carefully on the cooler side of sheaves

When last the sun his autumn tresses shook,

And the tann'd harvesters rich armfuls took.

Soon was he quieted to slumbrous rest:

But, ere it crept upon him, he had prest

Peona's busy hand against his lips,

And still, a sleeping, held her finger-tips

In tender pressure. And as a willow keeps

A patient watch over the stream that creeps

Windingly by it, so the quiet maid

Held her in peace: so that a whispering blade

Of grass, a wailful gnat, a bee bustling

Down in the blue-bells, or a wren light rustling

Among sere leaves and twigs, might all be heard.

O magic sleep! O comfortable bird,

That broodest o'er the troubled sea of the mind

Till it is hush'd and smooth! O unconfin'd

Restraint! imprisoned liberty! great key

To golden palaces, strange minstrelsy,

Fountains grotesque, new trees, bespangled caves,

Echoing grottos, full of tumbling waves

And moonlight; aye, to all the mazy world

Of silvery enchantment!- who, upfurl'd

Beneath thy drowsy wing a triple hour,

But renovates and lives?- Thus, in the bower,

Endymion was calm'd to life again.

Opening his eyelids with a healthier brain,

He said: "I feel this thine endearing love

All through my bosom: thou art as a dove

Trembling its closed eyes and sleeked wings

About me; and the pearliest dew not brings

Such morning incense from the fields of May,

As do those brighter drops that twinkling stray

From those kind eyes,- the very home and haunt

Of sisterly affection. Can I want

Aught else, aught nearer heaven, than such tears?

Yet dry them up, in bidding hence all fears

That, any longer, I will pass my days

Alone and sad. No, I will once more raise

My voice upon the mountain-heights; once more

Make my horn parley from their foreheads hoar:

Again my trooping hounds their tongues shall loll

Around the breathed boar: again I'll poll

The fair-grown yew tree, for a chosen bow:

And, when the pleasant sun is setting low,

Again I'll linger in a sloping mead

To hear the speckled thrushes, and see feed

Our idle sheep. So be thou cheered, sweet,

And, if thy lute is here, softly intreat

My soul to keep in its resolved course."

Hereat Peona, in their silver source,

Shut her pure sorrow drops with glad exclaim,

And took a lute, from which there pulsing came

A lively prelude, fashioning the way

In which her voice should wander. 'Twas a lay

More subtle cadenced, more forest wild

Than Dryope's lone lulling of her child;

And nothing since has floated in the air

So mournful strange. Surely some influence rare

Went, spiritual, through the damsel's hand;

For still, with Delphic emphasis, she spann'd

The quick invisible strings, even though she saw

Endymion's spirit melt away and thaw

Before the deep intoxication.

But soon she came, with sudden burst, upon

Her self-possession- swung the lute aside,

And earnestly said: "Brother, 'tis vain to hide

That thou dost know of things mysterious,

Immortal, starry; such alone could thus

Weigh down thy nature. Hast thou sinn'd in aught

Offensive to the heavenly power? Caught

A Paphian dove upon a message sent?

Thy deathful bow against some deer-herd bent

Sacred to Dian? Haply, thou hast seen

Her naked limbs among the alders green;

And that, alas! is death. No, I can trace

Something more high perplexing in thy face!"

Endymion look'd at her, and press'd her hand,

And said, "Art thou so pale, who wast so bland

And merry in our meadows? How is this?

Tell me thine ailment: tell me all amiss!

Ah! thou hast been unhappy at the change

Wrought suddenly in me. What indeed more strange?

Or more complete to overwhelm surmise?

Ambition is so sluggard; 'tis no prize,

That toiling years would put within my grasp,

That I have sighed for: with so deadly gasp

No man e'er panted for a mortal love.

So all have set my heavier grief above

These things which happen. Rightly have they done:

I, who still saw the horizontal sun

Heave his broad shoulder o'er the edge of the world,

Out-facing Lucifer, and then had hurl'd

My spear aloft, as signal for the chace

I, who, for very sport of heart, would race

With my own steed from Araby; pluck down

A vulture from his towery perching; frown

A lion into growling, loth retire

To lose, at once, all my toil-breeding fire,

And sink thus low! but I will ease my breast

Of secret grief, here in this bowery nest.

"This river does not see the naked sky,

Till it begins to progress silverly

Around the western border of the wood,

Whence, from a certain spot, its winding flood

Seems at the distance like a crescent moon:

And in that nook, the very pride of June,

Had I been used to pass my weary eves;

The rather for the sun unwilling leaves

So dear a picture of his sovereign power,

And I could witness his most kingly hour,

When he doth tighten up the golden reins,

And paces leisurely down amber plains

His snorting four. Now when his chariot last

Its beams against the zodiac-lion cast,

There blossom'd suddenly a magic bed

Of sacred ditamy, and poppies red:

At which I wondered greatly, knowing well

That but one night had wrought this flowery spell;

And, sitting down close by, began to muse

What it might mean. Perhaps, thought I, Morpheus,

In passing here, his owlet pinions shook;

Or, it may be, ere matron Night uptook

Her ebon urn, young Mercury, by stealth,

Had dipt his rod in it: such garland wealth

Came not by common growth. Thus on I thought,

Until my head was dizzy and distraught.

Moreover, through the dancing poppies stole

A breeze, most softly lulling to my soul;

And shaping visions all about my sight

Of colours, wings, and bursts of spangly light;

The which became more strange, and strange, and dim,

And then were gulph'd in a tumultuous swim:

And then I fell asleep. Ah, can I tell

The enchantment that afterwards befel?

Yet it was but a dream: yet such a dream

That never tongue, although it overteem

With mellow utterance, like a cavern spring,

Could figure out and to conception bring

All I beheld and felt. Methought I lay

Watching the zenith, where the milky way

Among the stars in virgin splendour pours;

And travelling my eye, until the doors

Of heaven appear'd to open for my flight,

I became loth and fearful to alight

From such high soaring by a downward glance:

So kept me stedfast in that airy trance,

Spreading imaginary pinions wide.

When, presently, the stars began to glide,

And faint away, before my eager view:

At which I sigh'd that I could not pursue,

And dropt my vision to the horizon's verge;

And lo! from opening clouds, I saw emerge

The loveliest moon, that ever silver'd o'er

A shell for Neptune's goblet: she did soar

So passionately bright, my dazzled soul

Commingling with her argent spheres did roll

Through clear and cloudy, even when she went

At last into a dark and vapoury tent

Whereat, methought, the lidless-eyed train

Of planets all were in the blue again.

To commune with those orbs, once more I rais'd

My sight right upward: but it was quite dazed

By a bright something, sailing down apace,

Making me quickly veil my eyes and face:

Again I look'd, and, O ye deities,

Who from Olympus watch our destinies!

Whence that completed form of all completeness?

Whence came that high perfection of all sweetness?

Speak, stubborn earth, and tell me where, O where

Hast thou a symbol of her golden hair?

Not oat-sheaves drooping in the western sun;

Not- thy soft hand, fair sister! let me shun

Such follying before thee- yet she had,

Indeed, locks bright enough to make me mad;

And they were simply gordian'd up and braided,

Leaving, in naked comeliness, unshaded,

Her pearl round ears, white neck, and orbed brow;

The which were blended in, I know not how,

With such a paradise of lips and eyes,

Blush-tinted cheeks, half smiles, and faintest sighs,

That, when I think thereon, my spirit clings

And plays about its fancy, till the stings

Of human neighbourhood envenom all.

Unto what awful power shall I call?

To what high fane?- Ah! see her hovering feet,

More bluely vein'd, more soft, more whitely sweet

Than those of sea-born Venus, when she rose

From out her cradle shell. The wind out-blows

Her scarf into a fluttering pavillion;

'Tis blue, and over-spangled with a million

Of little eyes, as though thou wert to shed,

Over the darkest, lushest blue-bell bed,

Handfuls of daisies."- "Endymion, how strange!

Dream within dream!"- "She took an airy range,

And then, towards me, like a very maid,

Came blushing, waning, willing, and afraid,

And press'd me by the hand: Ah! 'twas too much;

Methought I fainted at the charmed touch,

Yet held my recollections, even as one

Who dives three fathoms where the waters run

Gurgling in beds of coral: for anon,

I felt upmounted in that region

Where falling stars dart their artillery forth,

And eagles struggle with the buffeting north

That balances the heavy meteor-stone;

Felt too, I was not fearful, nor alone,

But lapp'd and lull'd along the dangerous sky.

Soon, as it seem'd, we left our journeying high,

And straightway into frightful eddies swoop'd;

Such as aye muster where grey time has scoop'd

Huge dens and caverns in a mountain's side;

There hollow sounds arous'd me, and I sigh'd

To faint once more by looking on my bliss

I was distracted; madly did I kiss

The wooing arms which held me, and did give

My eyes at once to death: but 'twas to live,

To take in draughts of life from the gold fount

Of kind and passionate looks; to count, and count

The moments, by some greedy help that seem'd

A second self, that each might be redeem'd

And plunder'd of its load of blessedness.

Ah, desperate mortal! I e'en dar'd to press

Her very cheek against my crowned lip,

And, at that moment, felt my body dip

Into a warmer air: a moment more,

Our feet were soft in flowers. There was store

Of newest joys upon that alp. Sometimes

A scent of violets, and blossoming limes,

Loiter'd around us; then of honey cells,

Made delicate from all white-flower bells;

And once, above the edges of our nest,

An arch face peep'd,- an Oread as I guess'd.

"Why did I dream that sleep o'er-power'd me

In midst of all this heaven? Why not see,

Far off, the shadows of his pinions dark,

And stare them from me? But no, like a spark

That needs must die, although its little beam

Reflects upon a diamond, my sweet dream

Fell into nothing- into stupid sleep.

And so it was, until a gentle creep,

A careful moving caught my waking ears,

And up I started: Ah! my sighs, my tears,

My clenched hands:- for lo! the poppies hung

Dew-dabbled on their stalks, the ouzel sung

A heavy ditty, and the sullen day

Had chidden herald Hesperus away,

With leaden looks: the solitary breeze

Bluster'd, and slept, and its wild self did teaze

With wayward melancholy; and I thought,

Mark me, Peona! that sometimes it brought

Faint fare-thee-wells, and sigh-shrilled adieus!

Away I wander'd- all the pleasant hues

Of heaven and earth had faded: deepest shades

Were deepest dungeons; heaths and sunny glades

Were full of pestilent light; our taintless rills

Seem'd sooty, and o'er-spread with upturn'd gills

Of dying fish; the vermeil rose had blown

In frightful scarlet, and its thorns out-grown

Like spiked aloe. If an innocent bird

Before my heedless footsteps stirr'd, and stirr'd

In little journeys, I beheld in it

A disguis'd demon, missioned to knit

My soul with under darkness; to entice

My stumblings down some monstrous precipice:

Therefore I eager followed, and did curse

The disappointment. Time, that aged nurse,

Rock'd me to patience. Now, thank gentle heaven!

These things, with all their comfortings, are given

To my down-sunken hours, and with thee,

Sweet sister, help to stem the ebbing sea

Of weary life."

Thus ended he, and both

Sat silent: for the maid was very loth

To answer; feeling well that breathed words

Would all be lost, unheard, and vain as swords

Against the enchased crocodile, or leaps

Of grasshoppers against the sun. She weeps

And wonders; struggles to devise some blame;

To put on such a look as would say, Shame

On this poor weakness! but, for all her strife,

She could as soon have crush'd away the life

From a sick dove. At length, to break the pause,

She said with trembling chance: "Is this the cause?

This all? Yet it is strange, and sad, alas!