English Academic Painter, Sculptor, and Writer

1830 - 1896

Leighton was born in Scarborough to a family in the import and export business. He was educated at University College School, London. He then received his legal training on the European continent, first from Edward von Steinle and then from Giovanni Costa. When in Florence, aged 24, where he studied at the Accademia di Belle Arti, he painted the procession of the Cimabue Madonna through the Borgo Allegri. He lived in Paris from 1855 to 1859, where he met Ingres, Delacroix, Corot and Millet.

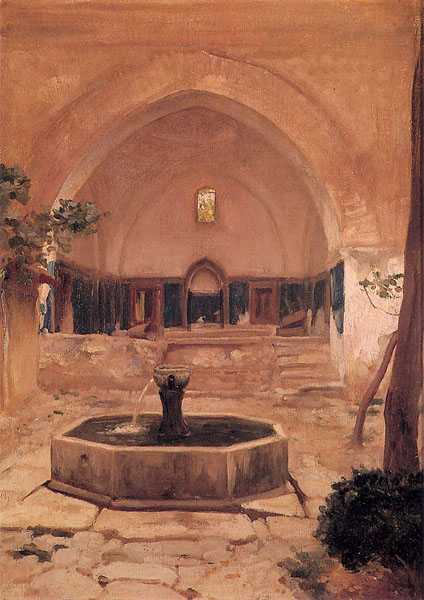

As he was unmarried, after his death his Barony was extinguished after existing for only a day; this is an all-time record in the Peerage. His house in Holland Park, London has been turned into a museum, the Leighton House Museum. It contains a number of his drawings and paintings, as well as some of his sculptures (including Athlete Wrestling with a Python). The house also features many of Leighton's inspirations, including his collection of Isnik tiles. Its centerpiece is the magnificent Arab Hall.

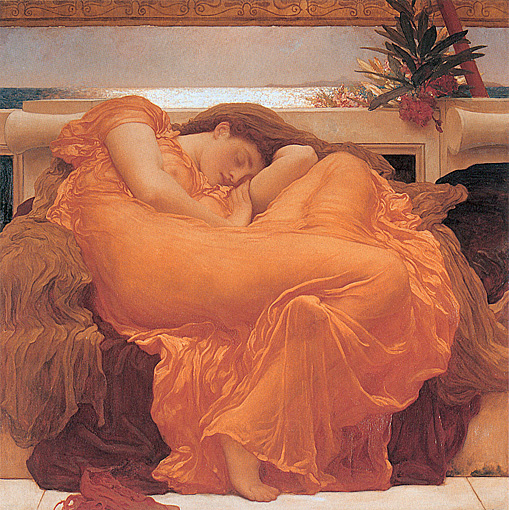

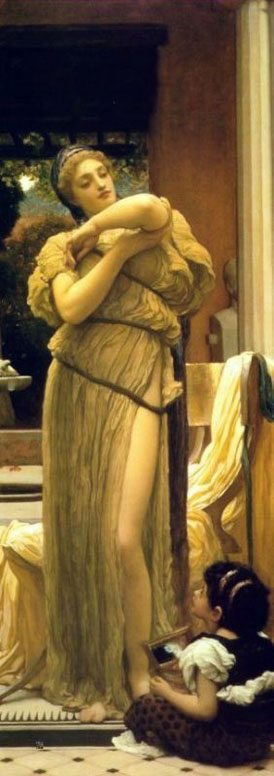

It is an image of splendid beauty that compels the viewer to gaze in wonder at the rapturous symphony of color and composition. In this painting, Leighton reveals his genius as both a colorist and a Classicist.

Although Flaming June does not tell a specific story, it is clear that the artist is inviting the spectator to contemplate the figure of the sleeping girl. Some scholars have suggested that this painting is Leighton's homage to a grand tradition in art history that goes back to Giorgione and Titian, in which images of slumbering women were represented. These sleeping women, who were usually at least partially nude and often referred to by the mythological name Venus, were meant to inspire sensuous thoughts (and reactions) in their primarily male audiences.

However, the Victorian era is notorious for its outwardly prudish attitudes toward overt sensuality. And while the model in Flaming June is certainly not nude, her fiery garments are meant to excite and arouse the senses. Indeed, the girl's dress is the most astonishing shade of orange, and this voluptuous color draws the eye. The vibrant orange is complemented by a soft band of blue in the background, and this effective combination of elements is but one of the characteristics that mark this painting as one of Leighton's most accomplished masterpieces.

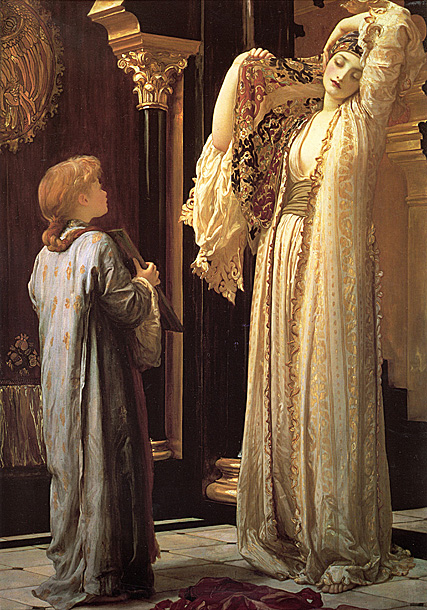

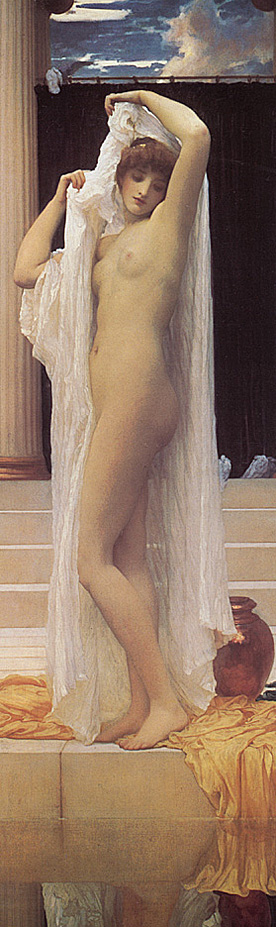

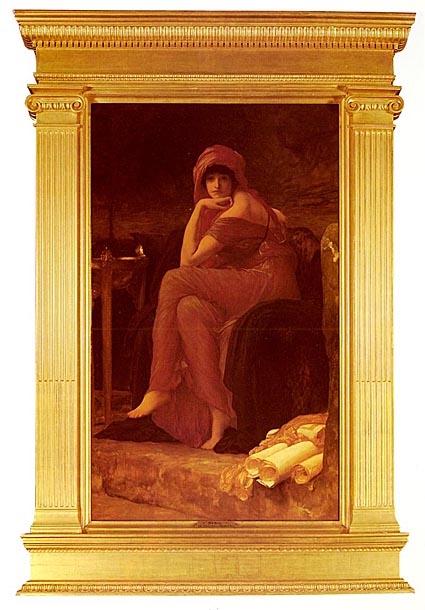

The model was Dorothy Dene, an actress who was one of Leighton's favorite models. She appears also in Flaming June and The Bath of Psyche. Leighton was instrumental in helping her with her acting career. Dene was her stage name. Her real name was Alice Pullan, one of four daughters and her family was long time friends of Leighton.

She appears to be thinking, "Physical Beauty is never enough ... from one who knows". Despite Dene's help from Leighton, her acting career fizzled, and was left depending on him for support and social position for many years.

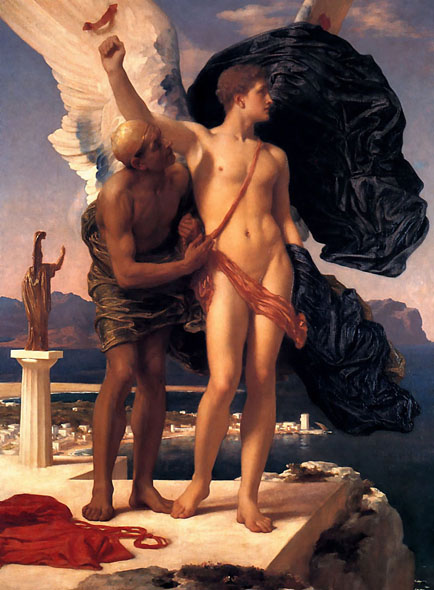

The labyrinth from which Theseus escaped by means of the clew of Ariadne was built by Daedalus, a most skilful artificer. It was an edifice with numberless winding passages and turnings opening into one another, and seeming to have neither beginning nor end, like the river Maeander, which returns on itself, and flows now onward, now backward, in its course to the sea. Daedalus built the labyrinth for King Minos, but afterwards lost the favor of the king, and was shut up in a tower. He contrived to make his escape from his prison, but could not leave the island by sea, as the king kept strict watch on all the vessels, and permitted none to sail without being carefully searched.

"Minos may control the land and sea," said Daedalus, "but not the regions of the air. I will try that way." So he set to work to fabricate wings for himself and his young son Icarus. He wrought feathers together, beginning with the smallest and adding larger, so as to form an increasing surface. The larger ones he secured with thread and the smaller with wax, and gave the whole a gentle curvature like the wings of a bird.

Icarus, the boy, stood and looked on, sometimes running to gather up the feathers which the wind had blown away, and then handling the wax and working it over with his fingers, by his play impeding his father in his labors. When at last the work was done, the artist, waving his wings, found himself buoyed upward, and hung suspended, poising himself on the beaten air. He next equipped his son in the same manner and taught him how to fly, as a bird tempts her young ones from the lofty nest into the air. When all was prepared for flight he said, "Icarus, my son, I charge you to keep at a moderate height, for if you fly too low the damp will clog your wings, and if too high the heat will melt them. Keep near me and you will be safe."

While he gave him these instructions and fitted the wings to his shoulders, the face of the father was wet with tears, and his hands trembled. He kissed the boy, not knowing that it was for the last time. Then rising on his wings, he flew off, encouraging him to follow, and looked back from his own flight to see how his son managed his wings.

As they flew the ploughman stopped his work to gaze, and the shepherd leaned on his staff and watched them, astonished at the sight, and thinking they were gods who could thus cleave the air.

They passed Samos and Delos on the left and Lebynthos on the right, when the boy, exulting in his career, began to leave the guidance of his companion and soar upward as if to reach heaven. The nearness of the blazing sun softened the wax which held the feathers together, and they came off. He fluttered with his arms, but no feathers remained to hold the air.

While his mouth uttered cries to his father it was submerged in the blue waters of the sea which thenceforth was called by his name. His father cried, "Icarus, Icarus, where are you?" At last he saw the feathers floating on the water, and bitterly lamenting his own arts, he buried the body and called the land Icaria in memory of his child.

Daedalus arrived safe in Sicily, where he built a temple to Apollo, and hung up his wings, an offering to the god.

Daedalus was so proud of his achievements that he could not bear the idea of a rival. His sister had placed her son Perdix under his charge to be taught the mechanical arts. He was an apt scholar and gave striking evidences of ingenuity. Walking on the seashore he picked up the spine of a fish. Imitating it, he took a piece of iron and notched it on the edge, and thus invented the saw. He, put two pieces of iron together, connecting them at one end with a rivet, and sharpening the other ends, and made a pair of compasses. Daedalus was so envious of his nephew's performances that he took an opportunity, when they were together one day on the top of a high tower to push him off. But Minerva (Athena), who favors ingenuity, saw him falling, and arrested his fate by changing him into a bird called after his name, the Partridge. This bird does not build his nest in the trees, nor take lofty flights, but nestles in the hedges, and mindful of his fall, avoids high places.

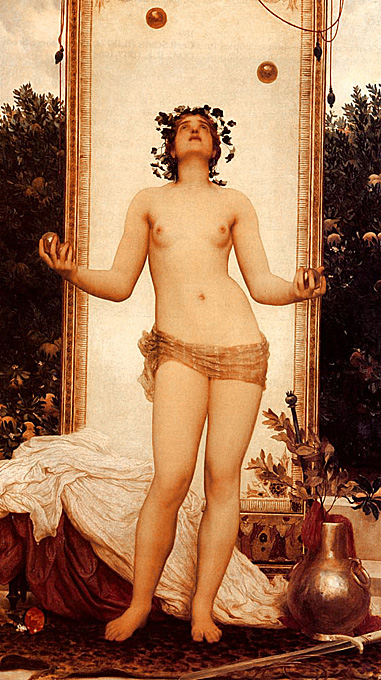

This design is full of youth, and beauty; the color is rich and warm - almost voluptuous ... We have the tree of life with its golden apples; for a rocky coast we have the beautiful Garden of Hesperides, with the purple ocean beyond. The three daughters of Atlas sit beneath a wonderful tree, around the trunk of which is wound the body of a huge serpent. The girl in the centre, who is half-draped, caresses the scaly hide of the monster; her sister on the right sings to the accompaniment of a lyre; while the maiden on the left toys carelessly with the food which she holds in a bowl. The grace and serenity of the composition are eminently characteristic of the President's later manner.

In the story, many suitors appeared before King Pelias, her father, when she became of age to marry. It was declared she would marry the first man to yoke a lion and a boar (or a bear in some cases) to a chariot. The man who would do this, King Admetus, was helped by Apollo, who had been banished from Olympus for 9 years to serve as a shepherd to Admetus. With Apollo's help, Admetus completed the king's task, and was allowed to marry Alcestis. After the wedding, Admetus forgot to make the required sacrifice to Artemis, and found his bed full of snakes. Apollo again helped the newly wed king, this time by making the Fates drunk, extracting from them a promise that if anyone would want to die instead of Admetus, they would allow it. Since no one volunteered, not even his elderly parents, Alcestis stepped forth. Shortly after, Heracles rescued Alcestis from Hades, as a token of appreciation for the hospitality of Admetus. Admetus and Alcestis had a son, Eumelus, a participant in the siege of Troy, and a daughter, Perimele.

Both figures are seated on the floor, resting comfortably on an opulently hued Oriental carpet. Details, such as a vase of lilies and a golden screen, form the backdrop for this delightful drama. Everything in the painting is equally visually enchanting, from the flower petals to the glossy red cherries to the sophisticated sheen of the woman's gown. Here again, Lord Leighton displays his prowess as an artist.

It is worth noting that the sense of sentimentality that was so much a part of Victorian art and life is captured in this splendid image.

"Though old as history itself, thou art fresh as breath of spring, blooming as thine own rosebud, as fragrant as thine own orange flower, O Damascus, Pearl of the East!"

DURING the first weeks at Damascus my only work was to find a suitable house and to settle down in it. Our predecessor in the Consulate had lived in a large house in the city itself, and as soon as he retired he let it to a wealthy Jew. In any case it would not have suited us, nor would any house within the city walls; for though some of them were quite beautiful-indeed, marble palaces gorgeously decorated and furnished after the manner of oriental houses-yet there is always a certain sense of imprisonment about Damascus, as the windows of the houses are all barred and latticed, and the gates of the city are shut at sunset. This would not have suited our wild-cat proclivities; we should have felt as though we were confined in a cage. So after a search of many days we took a house in the environs, about a quarter of an hour from Damascus, high up the hill. Just beyond it was the desert sand, and in the background a saffron-hued mountain known as the Camomile Mountain; and camomile was the scent which pervaded our village and all Damascus. Our house was in the suburb of Salahíyyeh, and we had good air and light, beautiful views, fresh water, quiet, and above all liberty. In five minutes we could gallop out over the mountains, and there was no locking us up at sunset. Here we pitched our tent.

David, a handsome, ruddy-cheeked youth and the youngest son of Jesse, is brought before Saul, the king of Israel, having slain the giant Philistine warrior Goliath with only a stone and sling.

Jonathan, the eldest son of Saul, is immediately struck with David on their first meeting, "And it came to pass, when he (David) had made an end of speaking unto Saul, that the soul of Jonathan was knit with the soul of David, and Jonathan loved him as his own soul.". That same day, "Jonathan and David made a covenant, because he loved him as his own soul". Jonathan removes and offers David the rich garments he is wearing, and shares with him his worldly possessions: "And Jonathan stripped himself of the robe that was upon him, and gave it to David, and his garments, even to his sword, and to his bow, and to his girdle.".

The people of Israel openly accept David and sing of his praises, so much so that it draws the jealousy of Saul. Saul tries repeatedly to kill David, but is each time unsuccessful, and David's reputation only grows with each attempt. To get rid of David, Saul decides to offer him a daughter in marriage, requesting a hundred enemy foreskins in lieu of a dowry - hoping David will be killed trying. David however returns with a trophy of two hundred foreskins and Saul has to fulfill his end of the bargain.

Learning of one of Saul's murder attempts, Jonathan warns David to hide because he "delighted much in David". David is forced to flee more of Saul's attempts to kill him In a moment when they find themselves alone together, David says to Jonathan, "Thy father certainly knows that I have found grace in thine eyes."

"Then said Jonathan unto David, 'Whatsoever thy soul desires, I will even do it for thee' ... (and) Jonathan made a covenant with the house of David, saying, 'Let the LORD even require it at the hand of David's enemies.' And Jonathan caused David to swear again, because he loved him: for he loved him as he loved his own soul".

David agrees to hide, until Jonathan can confront his father and ascertain whether it is safe for David to stay. Jonathan approaches his father to plead David's cause: "Then Saul's anger was kindled against Jonathan, and he said unto him, 'Thou son of the perverse rebellious woman, do not I know that thou hast chosen the son of Jesse (David) to thine own confusion, and unto the confusion of thy mother's nakedness".

Jonathan is so grieved that he does not eat for days. He goes to David at his hiding place to tell him that it is unsafe for him and he must leave. "David arose out of a place toward the south, and fell on his face to the ground, and bowed himself three times: and they kissed one another, and wept one with another, until David exceeded. And Jonathan said to David, Go in peace, forasmuch as we have sworn both of us in the name of the LORD, saying, The LORD be between me and thee, and between my seed and thy seed for ever. And he arose and departed: and Jonathan went into the city."

Saul continues to pursue David; David and Jonathan renew their covenant together; and eventually Saul and David reconcile. When Jonathan is slain on Mt. Gilboa by the Philistines, David laments his death saying, "I am distressed for thee, my brother Jonathan: very pleasant hast thou been unto me: thy love to me was wonderful, surpassing the love of women."

Although David was married, David himself articulates a distinction between his relationship with Jonathan and the bonds he shares with women. David is married to many women, one of whom is Jonathan's sister Michal, but the Bible does not mention David loving Michal (though it is stated that Michal loves David). He explicitly states, on hearing of Jonathan's death, that his love for Jonathan is greater than any bond he's experienced with women. Furthermore, social customs in the ancient Mediterranean basin, did not preclude extramarital homoerotic relationships. The Epic of Gilgamesh, which predates the Books of Samuel, depicts a remarkably similar homoerotic relationship between Gilgamesh and Enkidu.

Though sex is never explicitly depicted, much of the Bible's sexual terminology is shrouded in euphemism. Numerous passages allude to a physically intimate relationship between the two men: Jonathan's disrobing, his "delighting much" in David, and the kissing before their departure. Saul accuses Jonathan of "confusing the nakedness of his mother" with David; the nakedness of one's parents is a common Biblical sexual allusion.

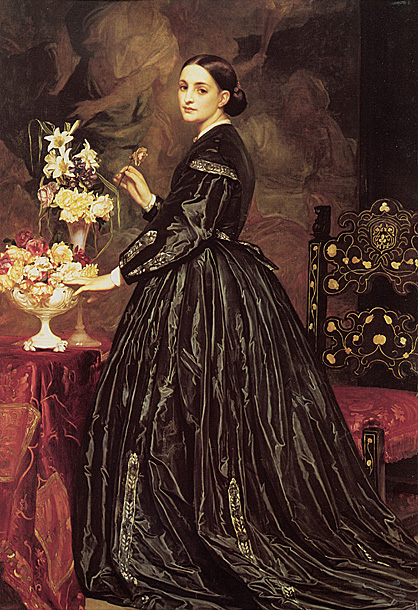

This original and eloquent study brings Frederic Leighton's portrait of May Sartoris to life through the artist's remarkable friendship with May's mother, celebrated opera singer Adelaide Sartoris. The young Leighton frequented Adelaide's artistic and literary salon in Rome in the early 1850s, and was on intimate terms with her by the time he painted her daughter's likeness in England around 1860. Malcolm Warner suggests that its wistful mood and intimations of mortality may be a reflection of Leighton's relationship with Adelaide as much as a response to his adolescent sitter. May Sartoris emerges as an evocation of the Romantic "child of nature," a meditation on themes of innocence and experience, and above all a testament to friendship.

He flew down to the marketplace, removing his helmet for the first time since he started his journey, and once again he became visible. Approaching an old woman selling fruit, he asked about the girl lashed to the cliff. "That is Princess Andromeda," she responded, obviously happy to pass on a story. "She is the daughter of our king Cepheus and his wife, Queen Cassiopeia.

"Queen Cassiopeia has always been very vain and boastful about her beauty. But this time her boasting got us all in trouble, for she said that her beauty was so enduring that even her daughter was more lovely than the Nereids. What she didn't know was that the Nereids were listening.

"When they heard these insults, the fifty Nereids stopped dancing and playing their instruments. They stopped singing and riding their sea beasts. They swiftly swam to their brother-in-law, Poseidon, the King of the Sea. "We have all been insulted, as has our beautiful sister, your wife Amphitrite. You must do something about that woman."

"When Amphitrite heard the story from her sisters, she too demanded justice, "Poseidon, you must do something, now." With his wife and fifty sisters-in-law relentlessly calling for revenge on Queen Cassiopeia, he knew he would have no peace at all until he took action against her. First, he immediately sent a flood-tide to drown Ethiopia and wash her crops away, then to finish them off, he sent a sea monster to ravage the people.

"The flood tides came and the farmers suffered as their crops and homes were washed away. The sea monster arrived near their shore and it was no longer safe for the fishermen to follow their trade, for when they tried to fish, the monster overturned their boats and swallowed the men whole. Food was in short supply and the people were frightened. It was then that the oracle of Ammon prophesied an end to all the trouble if King Cepheus would sacrifice his daughter Andromeda to the sea monster. "Sacrifice her, sacrifice her," the growing mob chanted, "like you are sacrificing us. Sacrifice her or we will sacrifice you," the people threatened. Not wanting to lose his power, King Cepheus had Andromeda chained to the cliff to await the fate of the sea monster."

An idea flashed through Perseus' mind. "Where can I find King Cepheus?" he asked the woman. She explained the route to take to reach the palace and, after thanking her for her help, Perseus set-off to enact his plan.

As he reached the palace, the royal family was assembled in the throne room. King Cepheus sat sadly, with his chin resting in his hand. His brother Phineus and his troops assembled near the wall, silently waiting for whatever unfolded before them. On her throne, which was next to Cepheus', sat Queen Cassiopeia, idly looking in a hand mirror while rearranging her hair. Perseus was announced and confidently approached the king. "King Cepheus, I come with a plan to rescue your daughter and rid your land of the dreaded sea monster. I am willing to risk my life to do this only if you will agree to let me marry your daughter Andromeda, providing she is also willing."

The king sat up, surprised at the boldness of this young man. "Certainly I'll agree to that, and I'll give you a kingdom as her dowry as well," said Cepheus, "but why do you need Andromeda's consent? It would upset and confuse her. She is not used to making her own decisions."

"If she would not be happy, how could I be?" responded Perseus. "I will ask her, you need not bother. I will enjoy being your son-in-law." With that, Perseus disappeared. He reappeared balancing upon the cliff ledge where Andromeda was chained. Startled, she stopped crying when she saw him. "When I save you from the sea monster, will you marry me?" he asked nervously. "Your father has given his permission. Don't worry, I will save you anyway." Her look of confusion gave way to a broad smile. "Yes," she answered.

The sea churned as it carried waves from distant sources onto the Ethiopian shore. Perseus glanced quickly across the water wondering which of the angry waves carried Poseidon's death warrant. He took a deep breath and strapped on the helmet of Hades to become invisible again. He seized his sickle and the young warrior sped through the air.

In the northwest, against the far reaches of the horizon, Perseus noticed a wave that dwarfed all the rest. He watched as it moved faster than the others, nor did it follow the normal pattern of the other waves. Instead it slid parallel to the land before cutting-in sharply toward shore, then it returned back to it's original point far offshore. It seemed to be waiting. As suddenly as it had come, it disappeared, then reappeared as a mammoth black body bursting through the sea sending a fountain of water higher than the waves. Perseus had seen his enemy and flew to meet him.

Ready for battle, Perseus saw the creature burst through the waves again, high into the open air. But this time, the creature was met with a blade of razor-sharp stone which slashed into its skin. As it submerged beneath the waves, the water darkened with its blood. Sharks, clustered like gnats, descended to tear away the flesh of the monstrous beast. Again the monster surged through the waves and as before, something invisible from above ripped his flesh as the seasalt burned his wounds. Deep into the sea he continued to plunge to wash away the trail of blood that clouded his vision. Then, with a clear view above, he rose to a point just below the surface and waited.

The sun was reflecting against the crystalline surface of the sea. There he saw a shadow cast by some creature floating through the air. The creature seemed to be shaped like a man with outstretched arms and had small wings fluttering at his heels. The monster floated closer to the surface where he could see more clearly every detail in the sky, but nothing was there except the shadow which he saw only from the depths.

The monster dove down to the ocean floor, then turned to face the sky, forming himself into a ball wound as tight as a spring. His body was now a weapon as he pushed off with his flippers, becoming a flesh torpedo aimed for impact at the location of the winged shadow.

Perseus baited his attacker, the fluttering sandal wings holding him motionless in the air as he waited for the attack. In one hand he held the head of Medusa and the other held the sickle. Perseus was ready.

The monster breached the waves ahead of and in easy reach of Perseus. Too late, the monster saw the approach of the snake-haired head of a woman. He had not realized that the water distorted the location of the image and in a single smooth motion, Perseus severed the monster's head, which was caught by a high wave and carried swiftly in the current.

Looking quickly for somewhere to place his weapons as he washed off the blood, Perseus spied a mound of seaweed growing on a sandbar that rose above the waves. He placed his sickle and Medusa's head there for only an instant, then he snatched off the helmet and stuffed it beneath his belt. Andromeda must see him in all his heroic splendor. Tidying his hair and straightening his tunic, he arranged himself to look unruffled before returning to claim his beautiful prize. As he replaced Medusa's head in the knapsack he brushed the seaweed only to find that it had turned the living plants to stone. The curious Nereids came to investigate, and were delighted to find the stone plants had spread over the entire underwater realm. The Nereids named this remarkable creation coral, and in their delight they brought tiny multicolored fishes there, to make it their new home.

Quickly skirting the waves, he found and grabbed the monster's head as it floated toward shore. Then on he flew to Andromeda's ledge where he broke her chains and scooped the princess up in his arms. While carrying Andromeda and holding the head of the monster by its ear, he set down upon shore to the cheers of the crowd. In jubilation, the wedding plans were made.,P. Phineus leaned against a column of the palace portico as he watched the celebrations below. His eyes narrowed as the crowd hailed Perseus, their new prince. It had been his rightful and promised place to marry Andromeda and become his brother's successor. He and Cepheus had planned it for years. Now this boy had stolen it from him and upset the natural course of family affairs. Phineus folded his arms against the events underway. He would find a way to stop them.

Perseus collected a cow, a steer and a bull. It was time to thank his father Zeus and mentors, Athena and Hermes, for the success of his adventure. Herding the animals to a clearing in the forest and tying them to trees, he collected stones and built three altars. One was for Athena, and to her alter he took and tied the cow. The next was for Hermes. The steer was tied there. The last was for father Zeus, and to this he took the bull. Pulling out his sickle, he prepared to continue with his ritual, when, from behind him, he heard someone say, "Let us help you make a fitting sacrifice."

He turned to see Phineus approach with his band of twenty men. Their swords were out and the blades were flashing. "Don't wait for their attack, Perseus. There are too many of them. They mean to kill you," Perseus heard Athena as she spoke to him from her altar. Reaching into his knapsack, he grabbed Medusa's head by her snaky locks. Averting his eyes, he held the head high in front of him. Moving Medusa to his side, he looked ahead to where Phineus and his troops were. Like a sculpture garden, the clearing was filled with men turned to stone.

Perseus and Andromeda, married, contentedly made their home within the palace of Cepheus for a number of years. But one day, as he watched his children at play, Perseus remembered that he had not completed his mission. "I wonder what happened to my mother?" he asked himself.

Faint as a climate-changing bird that flies

All night across the darkness, and at dawn

Falls on the threshold of her native land,

And can no more, thou camest, O my child,

Led upward by the God of ghosts and dreams,

Who laid thee at Eleusis, dazed and dumb,

With passing thro' at once from state to state,

Until I brought thee hither, that the day,

When here thy hands let fall the gather'd flower,

Might break thro' clouded memories once again

On thy lost self. A sudden nightingale

Saw thee, and flash'd into a frolic of song

And welcome; and a gleam as of the moon,

When first she peers along the tremulous deep,

Fled wavering o'er thy face, and chased away

That shadow of a likeness to the king

Of shadows, thy dark mate. Persephone!

Queen of the dead no more -- my child! Thine eyes

Again were human-godlike, and the Sun

Burst from a swimming fleece of winter gray,

And robed thee in his day from head to feet

"Mother!" and I was folded in thine arms.

Child, those imperial, disimpassion'd eyes

Awed even me at first, thy mother -- eyes

That oft had seen the serpent-wanded power

Draw downward into Hades with his drift

Of fickering spectres, lighted from below

By the red race of fiery Phlegethon;

But when before have Gods or men beheld

The Life that had descended re-arise,

And lighted from above him by the Sun?

So mighty was the mother's childless cry,

A cry that ran thro' Hades, Earth, and Heaven!

So in this pleasant vale we stand again,

The field of Enna, now once more ablaze

With flowers that brighten as thy footstep falls,

All flowers -- but for one black blur of earth

Left by that closing chasm, thro' which the car

Of dark Aidoneus rising rapt thee hence.

And here, my child, tho' folded in thine arms,

I feel the deathless heart of motherhood

Within me shudder, lest the naked glebe

Should yawn once more into the gulf, and thence

The shrilly whinnyings of the team of Hell,

Ascending, pierce the glad and songful air,

And all at once their arch'd necks, midnight-maned,

Jet upward thro' the mid-day blossom. No!

For, see, thy foot has touch'd it; all the space

Of blank earth-baldness clothes itself afresh,

And breaks into the crocus-purple hour

That saw thee vanish.

Child, when thou wert gone,

I envied human wives, and nested birds,

Yea, the cubb'd lioness; went in search of thee

Thro' many a palace, many a cot, and gave

Thy breast to ailing infants in the night,

And set the mother waking in amaze

To find her sick one whole; and forth again

Among the wail of midnight winds, and cried,

"Where is my loved one? Wherefore do ye wail?"

And out from all the night an answer shrill'd,

"We know not, and we know not why we wail."

I climb'd on all the cliffs of all the seas,

And ask'd the waves that moan about the world

"Where? do ye make your moaning for my child?"

And round from all the world the voices came

"We know not, and we know not why we moan."

"Where?" and I stared from every eagle-peak,

I thridded the black heart of all the woods,

I peer'd thro' tomb and cave, and in the storms

Of Autumn swept across the city, and heard

The murmur of their temples chanting me,

Me, me, the desolate Mother! "Where"? -- and turn'd,

And fled by many a waste, forlorn of man,

And grieved for man thro' all my grief for thee,

The jungle rooted in his shatter'd hearth,

The serpent coil'd about his broken shaft,

The scorpion crawling over naked skulls;

I saw the tiger in the ruin'd fane

Spring from his fallen God, but trace of thee

I saw not; and far on, and, following out

A league of labyrinthine darkness, came

On three gray heads beneath a gleaming rift.

"Where"? and I heard one voice from all the three

"We know not, for we spin the lives of men,

And not of Gods, and know not why we spin!

There is a Fate beyond us." Nothing knew.

Last as the likeness of a dying man,

Without his knowledge, from him flits to warn

A far-off friendship that he comes no more,

So he, the God of dreams, who heard my cry,

Drew from thyself the likeness of thyself

Without thy knowledge, and thy shadow past

Before me, crying "The Bright one in the highest

Is brother of the Dark one in the lowest,

And Bright and Dark have sworn that I, the child

Of thee, the great Earth-Mother, thee, the Power

That lifts her buried life from loom to bloom,

Should be for ever and for evermore

The Bride of Darkness."

So the Shadow wail'd.

Then I, Earth-Goddess, cursed the Gods of Heaven.

I would not mingle with their feasts; to me

Their nectar smack'd of hemlock on the lips,

Their rich ambrosia tasted aconite.

The man, that only lives and loves an hour,

Seem'd nobler than their hard Eternities.

My quick tears kill'd the flower, my ravings hush'd

The bird, and lost in utter grief I fail'd

To send my life thro' olive-yard and vine

And golden grain, my gift to helpless man.

Rain-rotten died the wheat, the barley-spears

Were hollow-husk'd, the leaf fell, and the sun,

Pale at my grief, drew down before his time

Sickening, and Aetna kept her winter snow.

Then He, the brother of this Darkness, He

Who still is highest, glancing from his height

On earth a fruitless fallow, when he miss'd

The wonted steam of sacrifice, the praise

And prayer of men, decreed that thou should'st dwell

For nine white moons of each whole year with me,

Three dark ones in the shadow with thy King.

Once more the reaper in the gleam of dawn

Will see me by the landmark far away,

Blessing his field, or seated in the dusk

Of even, by the lonely threshing-floor,

Rejoicing in the harvest and the grange.

Yet I, Earth-Goddess, am but ill-content

With them, who still are highest. Those gray heads,

What meant they by their "Fate beyond the Fates"

But younger kindlier Gods to bear us down,

As we bore down the Gods before us? Gods,

To quench, not hurl the thunderbolt, to stay,

Not spread the plague, the famine; Gods indeed,

To send the noon into the night and break

The sunless halls of Hades into Heaven?

Till thy dark lord accept and love the Sun,

And all the Shadow die into the Light,

When thou shalt dwell the whole bright year with me,

And souls of men, who grew beyond their race,

And made themselves as Gods against the fear

Of Death and Hell; and thou that hast from men,

As Queen of Death, that worship which is Fear,

Henceforth, as having risen from out the dead,

Shalt ever send thy life along with mine

From buried grain thro' springing blade, and bless

Their garner'd Autumn also, reap with me,

Earth-mother, in the harvest hymns of Earth

The worship which is Love, and see no more

The Stone, the Wheel, the dimly-glimmering lawns

Of that Elysium, all the hateful fires

Of torment, and the shadowy warrior glide

Along the silent field of Asphodel.

Through the open window of the church the fragrant incense was wafted and with it the fragrant names of her who was conceived without stain of original sin, spiritual vessel, pray for us, honourable vessel, pray for us, vessel of singular devotion, pray for us, mystical rose. And careworn hearts were there and toilers for their daily bread and many who had erred and wandered, their eyes wet with contrition but for all that bright with hope for the reverend father Hughes had told them what the great saint Bernard said in his famous prayer of Mary, the most pious Virgin's intercessory power that it was not recorded in any age that those who implored her powerful protection were ever abandoned by her.

The twins were now playing again right merrily for the troubles of childhood are but as fleeting summer showers. Cissy played with baby Boardman till he crowed with glee, clapping baby hands in air. Peep she cried behind the hood of the pushcar and Edy asked where was Cissy gone and then Cissy popped up her head and cried ah! and, my word, didn't the little chap enjoy that! And then she told him to say papa.

-- Say papa, baby. Say pa pa pa pa pa pa pa.

And baby did his level best to say it for he was very intelligent for eleven months everyone said and big for his age and the picture of health, a perfect little bunch of love, and he would certainly turn out to be something great, they said.

-- Hajajajahaja.

Cissy wiped his little mouth with the dribbling bib and wanted him to sit up properly, and say pa pa pa but when she undid the strap she cried out, holy saint Denis, that he was possing wet and to double the half blanket the other way under him. Of course his infant majesty was most obstreperous at such toilet formalities and he let everyone know it:

-- Habaa baaaahabaaa baaaa.

And two great big lovely big tears coursing down his cheeks. It was all no use soothering him with no, nono, baby, no and telling him about the geegee and where was the puffpuff but Ciss, always readywitted, gave him in his mouth the teat of the suckingbottle and the young heathen was quickly appeased.

Gerty wished to goodness they would take their squalling baby home out of that and not get on her nerves no hour to be out and the little brats of twins. She gazed out towards the distant sea. It was like the paintings that man used to do on the pavement with all the coloured chalks and such a pity too leaving them there to be all blotted out, the evening and the clouds coming out and the Bailey light on Howth and to hear the music like that and the perfume of those incense they burned in the church like a kind of waft. And while she gazed her heart went pitapat. Yes, it was her he was looking at and there was meaning in his look. His eyes burned into her as though they would search her through and through, read her very soul. Wonderful eyes they were, superbly expressive, but could you trust them? People were so queer. She could see at once by his dark eyes and his pale intellectual face that he was a foreigner, the image of the photo she had of Martin Harvey, the matinée idol, only for the moustache which she preferred because she wasn't stagestruck like Winny Rippingham that wanted they two to always dress the same on account of a play but she could not see whether he had an aquiline nose or a slightly retroussé from where he was sitting. He was in deep mourning, she could see that, and the story of a haunting sorrow was written on his face. She would have given worlds to know what it was. He was looking up so intently, so still and he saw her kick the ball and perhaps he could see the bright steel buckles of her shoes if she swung them like that thoughtfully with the toes down. She was glad that something told her to put on the transparent stockings thinking Reggy Wylie might be out but that was far away. Here was that of which she had so often dreamed. It was he who mattered and there was joy on her face because she wanted him because she felt instinctively that he was like no-one else. The very heart of the girlwoman went out to him, her dreamhusband, because she knew on the instant it was him. If he had suffered, more sinned against than sinning, or even, even, if he had been himself a sinner, a wicked man, she cared not. Even if he was a protestant or methodist she could convert him easily if he truly loved her. There were wounds that wanted healing with heartbalm. She was a womanly woman not like other flighty girls, unfeminine, he had known, those cyclists showing off what they hadn't got and she just yearned to know all, to forgive all if she could make him fall in love with her, make him forget the memory of the past. Then mayhap he would embrace her gently, like a real man, crushing her soft body to him, and love her, his ownest girlie, for herself alone.

Refuge of sinners. Comfortress of the afflicted. Ora pro nobis. Well has it been said that whosoever prays to her with faith and constancy can never be lost or cast away: and fitly is she too a haven of refuge for the afflicted because of the seven dolours which transpierced her own heart. Gerty could picture the whole scene in the church, the stained glass windows lighted up, the candles, the flowers and the blue banners of the blessed Virgin's sodality and Father Conroy was helping Canon O'Hanlon at the altar, carrying things in and out with his eyes cast down. He looked almost a saint and his confession-box was so quiet and clean and dark and his hands were just like white wax and if ever she became a Dominican nun in their white habit perhaps he might come to the convent for the novena of Saint Dominic. He told her that time when she told him about that in confession crimsoning up to the roots of her hair for fear he could see, not to be troubled because that was only the voice of nature and we were all subject to nature s laws, he said, in this life and that that was no sin because that came from the nature of woman instituted by God, he said, and that Our Blessed Lady herself said to the archangel Gabriel be it done unto me according to Thy Word. He was so kind and holy and often and often she thought and thought could she work a ruched teacosy with embroidered floral design for him as a present or a clock but they had a clock she noticed on the mantelpiece white and gold with a canary bird that came out of a little house to tell the time the day she went there about the flowers for the forty hours' adoration because it was hard to know what sort of a present to give or perhaps an album of illuminated views of Dublin or some place.

The exasperating little brats of twins began to quarrel again and Jacky threw the ball out towards the sea and they both ran after it. Little monkeys common as ditchwater. Someone ought to take them and give them a good hiding for themselves to keep them in their places, the both of them. And Cissy and Edy shouted after them to come back because they were afraid the tide might come in on them and be drowned.

-- Jacky! Tommy!

Not they! What a great notion they had! So Cissy said it was the very last time she'd ever bring them out. She jumped up and called them and she ran down the slope past him, tossing her hair behind her which had a good enough colour if there had been more of it but with all the thingamerry she was always rubbing into it she couldn't get it to grow long because it wasn't natural so she could just go and throw her hat at it. She ran with long gandery strides it was a wonder she didn't rip up her skirt at the side that was too tight on her because there was a lot of the tomboy about Cissy Caffrey and she was a forward piece whenever she thought she had a good opportunity to show off and just because she was a good runner she ran like that so that he could see all the end of her petticoat running and her skinny shanks up as far as possible. It would have served her just right if she had tripped up over something accidentally on purpose with her high crooked French heels on her to make her look tall and got a fine tumble. Tableau! That would have been a very charming exposé for a gentleman like that to witness.

Queen of angels, queen of patriarchs, queen of prophets, of all saints, they prayed, queen of the most holy rosary and then Father Conroy handed the thurible to Canon O'Hanlon and he put in the incense and censed the Blessed Sacrament and Cissy Caffrey caught the two twins and she was itching to give them a ringing good clip on the ear but she didn't because she thought he might be watching but she never made a bigger mistake in all her life because Gerty could see without looking that he never took his eyes off of her and then Canon O'Hanlon handed the thurible back to Father Conroy and knelt down looking up at the Blessed Sacrament and the choir began to sing Tantum ergo and she just swung her foot in and out in time as the music rose and fell to the Tantumer gosa cramen tum. Three and eleven she paid for those stockings in Sparrow's of George's street on the Tuesday, no the Monday before Easter and there wasn't a brack on them and that was what he was looking at, transparent, and not at her insignificant ones that had neither shape nor form (the cheek of her!) because he had eyes in his head to see the difference for himself.

Cissy came up along the strand with the two twins and their ball with her hat anyhow on her to one side after her run and she did look a streel tugging the two kids along with the flimsy blouse she bought only a fortnight before like a rag on her back and bit of her petticoat hanging like a caricature. Gerty just took off her hat for a moment to settle her hair and a prettier, a daintier head of nutbrown tresses was never seen on a girl's shoulders, a radiant little vision, in sooth, almost maddening in its sweetness. You would have to travel many a long mile before you found a head of hair the like of that. She could almost see the swift answering flush of admiration in his eyes that set her tingling in every nerve. She put on her hat so that she could see from underneath the brim and swung her buckled shoe faster for her breath caught as she caught the expression in his eyes. He was eyeing her as a snake eyes its prey. Her woman's instinct told her that she had raised the devil in him and at the thought a burning scarlet swept from throat to brow till the lovely colour of her face became a glorious rose.

Eight years later Electra returned from Athens with her brother, Orestes. According to Pindar, Orestes was saved by his old nurse or by Electra, and was taken to Phanote on Mount Parnassus, where King Strophius took charge of him.

In his twentieth year, Orestes was ordered by the Delphic oracle to return home and avenge his father's death. According to Aeschylus, he met Electra before the tomb of Agamemnon, where both had gone to perform rites to the dead; a recognition took place, and they arranged how Orestes should accomplish his revenge.

Orestes, after the deed (sometimes with Electra helping), goes mad, and is pursued by the Erinyes, or Furies, whose duty it is to punish any violation of the ties of family piety. Electra is not hounded by the Erinyes.

Orestes takes refuge in the temple at Delphi. Even though Apollo (to whom the Delphic temple was dedicated) had ordered him to do the deed, he is powerless to protect Orestes from the consequences of his actions.

At last Athena (also known as Areia) receives him on the Acropolis of Athens and arranges a formal trial of the case before twelve Attic judges. The Erinyes demand their victim; he pleads the orders of Apollo; the votes of the judges are equally divided, and Athena gives her casting vote for acquittal.

Later, Electra married Pylades, Orestes' close friend and son of King Strophius (the same one who had cared for Orestes while he hid from his mother and her lover).

Generally, an odalisque was never seen by the sultan, but instead remained under the direct supervision of the Valide sultan. If an odalisque was of extraordinary beauty or had exceptional talents in dancing or singing, she would be trained as a possible concubine. If selected, an odalisque trained as a concubine would serve the sultan sexually, and only after such sexual contact would she change in status, becoming thenceforth a concubine. In the Ottoman Empire, concubines encountered the sultan only once-unless she was especially skilled in dance, singing, or the sexual arts, and thus gained his attention. If a concubine's contact with the sultan resulted in the birth of a son, she would become one of his wives.

At the base of the column there is a cluster of leaves and fruit. Dusky grapes cascade down the platform, their dark color complemented by the greens, golds, and russets of the lush leaves. This appealing still life can be interpreted as an offering, and the column an altar. The tiny golden statue is in fact an image of some Classical goddess, and it is to this object that the white-robed woman is paying homage. With these observations in mind, the subject of the painting becomes much more clear - the woman is in fact begging assistance from an unidentified goddess. The Classical details in the background also enhance the ancient setting.

Author and Leighton scholar Christopher Newall suggests that the woman in this work is either a dancer or singer who is looking to her Muse for inspiration. This is a perfectly plausible - not to mention charming - interpretation of the painting. Certainly, the title Invocation also reinforces this explanation. As with many of Lord Leighton's later works, however, one can enjoy the exquisite beauty of the painting without troubling too much over its exact meaning.

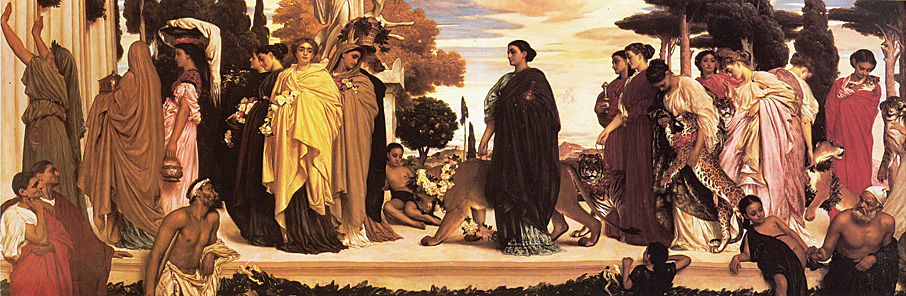

This is one of Leighton's 'Panavision' projects, although he avoids the wholly serial effect of the larger and earlier Cimabue and Daphnephoria by positioning his heroine dead center. We know very well that she's upset about more than the line at the water-trough; nevertheless the black-shrouded figure is visually rather dull. Thus the eye circulates around the bit-players (including various Denes, easily recognizable even in the sketch) who are heartlessly celebrating the joys of togetherness.

Then there's the sky. Someone, some time, will write a fascinating monograph on the true significance of the distinctive, rather bizarre cloudscapes that Leighton put into the background of many of his grand machines. Here he outdoes himself with a formation that no one today could possibly paint without thinking of the Bomb. That's progress.

The painting depicts the story of Cymon, a rough brutish fellow, and his first glance at the beautiful Iphigenia. Happening upon her sleeping figure, Cymon is instantly in awe, and he gives up his rough wild ways and marries Iphigenia. The painting is very softly lit by the rising moon, giving the whole painting an orange hue that softens all tones. In the center is the sleeping figure of Iphigenia, turned towards the viewer. This way, not only is Cymon gazing at her beauty, but the viewer is also invited to contemplate Iphigenia and find their own redemption. She is very strongly lit, and the hue gives her an almost all over halo effect. The robes that she wears are draped on, and fit her body perfectly, yet modestly (Leighton painted few nudes in his career). Barrington writes that Leighton painted "with emotionally intimate and caressing sense of beauty". The Athenaeum of 1897 writes "The type of the lady’s face and form is one of the noblest Sir Frederic Leighton has developed.. Her expression has the dignified air of repose that belongs to an antique statue."

This is the grandest of a group of huge processional pictures on which Leighton's reputation largely rests. His classical vision of beauty and form, his skill in arranging his figures and his imagination in conceiving the rich and luxuriant setting make this one of the few British paintings which can be compared to with the great historical and mythological works of 19th century France and Germany.

‘The Daphnephoria’ was painted for the dining room of his close friend and patron, the banker James Stewart Hodgson. He was forced to sell it following the first collapse of Barings Bank in 1890.

This was Leighton's first major work, painted in Rome. It was shown at the Academy in 1855. It was an immediate success, and Queen Victoria bought it for 600 guineas on opening day. She recorded in her diary: 'There was a very big picture by a man called Leighton. It is a beautiful painting, quite reminding one of a Paul Veronese, so bright and full of light. Albert was enchanted with it - so much so that he made me buy it.'

The subject is from Vasari's account of how the 'Rucellai Madonna' was carried from the house of the 13th century painter Cimabue to the church of S. Maria Novella in Florence. Vasari also mentions Charles of Anjou, King of Naples, and Leighton has shown him on horseback on the right of the composition.

The composition of Lord Leighton's Idyll is elegantly straightforward - two female figures recline under a tree branch on the right side of the work, while a single male figure sits on the left. The male has his back turned to the viewer, but even from this position we can see that he plays an instrument. This figure, who appears in the garb of a shepherd, seems to have enchanted his two female companions with his music, for the women rest languidly against a tree, seemingly in a trance.

It is easy to see why some art historians have identified the pair of females as nymphs or dryads. The diaphanous draperies resemble the garments worn by women in ancient Greek art, and with their flawlessly beautiful features, these creatures are idealized images inspired by Classical art and mythology. However, it is interesting to note that there were some significant Nineteenth century influences in this painting as well. Stephen Jones has pointed out that face of one of the nymphs was modeled by the legendary Lillie Langtry.

With its calm, horizontal emphasis, glorious landscape background, fashionable Classical allusions, and exquisite figures, the painting Idyll demonstrates once again why Lord Leighton is viewed as one of the most successful and respected artists of the Victorian era.

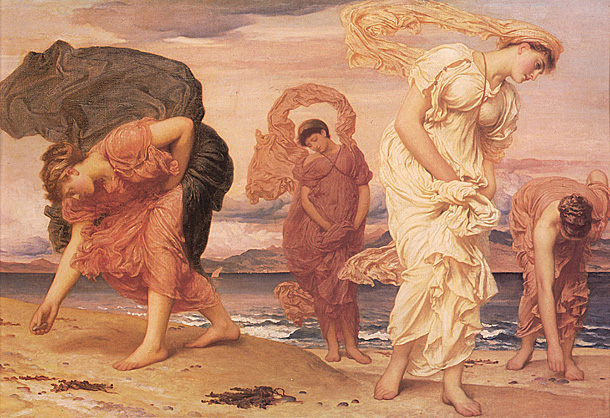

In Iliad XVIII, when Thetis cries out in sympathy for the grief of Achilles for the slain Patroclus:

"There gathered round her every goddess, every Nereid that was in the deep salt sea. Glauce was there and Thaleia and Cymodoce; Nesaea, Speio, Thoe and ox-eyed Halie; Cymothoe, Actaee and Limnoreia; Melite, Iaera, Amphithoe and Agaue; Doto, Proto, Pherusa and Dynamene; Dexamene, Amphinome and Callianeira; Doris, Panope and far-sung Galatea; Nemertes, Apseudes and Callianassa. Clymene came too, with Ianeira, Ianassa, Maera, Oreithuia, Amatheia of the lovely locks, and other Nereids of the salt sea depths. The silvery cave was full of nymphs"

In classical art they are frequently depicted riding an assortment of sea creatures - dolphins, sea monsters, and hippocampi.

~William Wordsworth~ (1770-1850)

Newell is struck by the "theatricality" of Leighton's painting of Romeo and Juliet; the scene is "in effect a tableau from the play as performed on stage." The artificiality of the lighting, he adds, "heightens the sense that one is witnessing a performance rather than a scene from life. The foreground figures seem to glow luminously, while the central group is seen in half-light, and the remaining part recedes into shadowy obscurity; the blocked-out and compositionally unimportant background is exactly like that of a stage set. . . . Leighton has offered a finale to a play, with all the protagonists present for the final curtain fall, rather than a scene of human tragedy".

Act 2, Scene 2

ROMEO

But, soft! what light through yonder window breaks?

It is the east, and Juliet is the sun.

Arise, fair sun, and kill the envious moon,

Who is already sick and pale with grief,

That thou her maid art far more fair than she:

Be not her maid, since she is envious;

Her vestal livery is but sick and green

And none but fools do wear it; cast it off.

It is my lady, O, it is my love!

O, that she knew she were!

She speaks yet she says nothing: what of that?

Her eye discourses; I will answer it.

I am too bold, 'tis not to me she speaks:

Two of the fairest stars in all the heaven,

Having some business, do entreat her eyes

To twinkle in their spheres till they return.

What if her eyes were there, they in her head?

The brightness of her cheek would shame those stars,

As daylight doth a lamp; her eyes in heaven

Would through the airy region stream so bright

That birds would sing and think it were not night.

See, how she leans her cheek upon her hand!

O, that I were a glove upon that hand,

That I might touch that cheek!

JULIET

Ay me!

ROMEO

She speaks:

O, speak again, bright angel! for thou art

As glorious to this night, being o'er my head

As is a winged messenger of heaven

Unto the white-upturned wondering eyes

Of mortals that fall back to gaze on him

When he bestrides the lazy-pacing clouds

And sails upon the bosom of the air.

JULIET

O Romeo, Romeo! wherefore art thou Romeo?

Deny thy father and refuse thy name

Or, if thou wilt not, be but sworn my love,

And I'll no longer be a Capulet.

ROMEO

Shall I hear more, or shall I speak at this?

JULIET

'Tis but thy name that is my enemy;

Thou art thyself, though not a Montague.

What's Montague? it is nor hand, nor foot,

Nor arm, nor face, nor any other part

Belonging to a man. O, be some other name!

What's in a name? that which we call a rose

By any other name would smell as sweet;

So Romeo would, were he not Romeo call'd,

Retain that dear perfection which he owes

Without that title. Romeo, doff thy name,

And for that name which is no part of thee

Take all myself.

OH, THE BLESING AND TRAGEDY OF LOVE

Psamathe was one of the fifty daughters of the sea god Nereus. These lovely sea goddesses were known collectively as the Nereids, and several Nereids - including Psamathe - played roles in myth. Psamathe's main contribution to mythology is found in the brief story that involves her relationship with Aeacus. This affair resulted in the birth of a son named Phocus.

In this painting, the emphasis is on the figure of Psamathe. The sea-nymph is posed so that one can only glimpse her back. And although we cannot see her face, we can sense that she is gazing out into the placid blue water. Psamathe's connection to the water is reinforced by the froth of white draperies upon which she reclines, for the appearance of the cloth echoes the white waves of the sea.

In this painting, Lord Leighton has represented Antigone as a tragic heroine. Using dramatic contrasts of light and dark, Leighton leads the viewer to focus on the expression on Antigone's face - she appears to be suffering from some troubled emotion, but still remains a brave and noble figure. By depicting a bust rather than a full-length view of Antigone we are forced to concentrate on the heroine exclusively and not, instead, the painting's setting.

The model for this painting was Dorothy Dene. Dene was a lovely actress who often posed for Leighton, and indeed, her features appear in a number of the artist's works, including Clytie and The Return of Persephone.

The word sibyl comes (via Latin) from the ancient Greek word sibylla, meaning prophetess. There were eventually many Sibyls in the ancient world,[1] but because of the importance of the Cumaean Sibyl in the legends of early Rome codified in Virgil's Aeneid VI, she became the most famous among Romans, supplanting the Erythraean Sibyl famed among Greeks: in Latin she was often simply referred to as The Sibyl.

She is one of the four sibyls painted by Raphael at Santa Maria della Pace, but in the art of Michelangelo (illustration, right) her powerful presence overshadows every other Sibyl, even her younger and more beautiful sisters, such as the Delphic Sibyl.

There are various names for the Cumaean Sibyl besides the "Herophile" of Pausanias and Lactantius[2] or the Aeneid's "Deiphobe, daughter of Glaucus": "Amaltheia", "Demophile" or "Taraxandra" are all offered in various references.

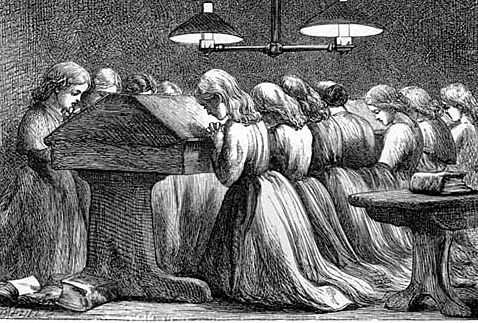

By Felicia Dorothea Browne Hemans (1793 - 1835)

-BERNARD BARTON

HUSH! 'tis a holy hour-the quiet room

Seems like a temple, while yon soft lamp sheds

A faint and starry radiance, through the gloom

And the sweet stillness, down on fair young heads,

With all their clustering locks, untouch'd by care,

And bow'd, as flowers are bow'd with night, in prayer.

Gaze on-'tis lovely!-Childhood's lip and cheek,

Mantling beneath its earnest brow of thought

Gaze-yet what seest thou in those fair, and meek,

And fragile things, as but for sunshine wrought?

Thou seest what grief must nurture for the sky,

What death must fashion for eternity!

O! joyous creatures! that will sink to rest,

Lightly, when those pure orisons are done,

As birds, with slumber's honey-dew opprest,

'Midst the dim folded leaves, at set of sun

Life up your hearts! though yet no sorrow lies

Dark in the summer-heaven of those clear eyes.

Though fresh within your breasts the untroubled springs

Of hope make melody where'er ye tread,

And o'er your sleep bright shadows, from the wings

Of spirits visiting but youth, be spread;

Yet in those flute-like voices, mingling low,

Is woman's tenderness-how soon her woe!

Her lot is on you-silent tears to weep,

And patient smiles to wear through suffering's hour,

And sumless riches, from affection's deep,

To pour on broken reeds-a wasted shower!

And to make idols, and to find them clay,

And to bewail that worship-therefore pray!

Her lot is on you-to be found untired,

Watching the stars out by the bed of pain,

With a pale cheek, and yet a brow inspired,

And a true heart of hope, though hope be vain;

Meekly to bear with wrong, to cheer decay,

And oh! to love through all things-therefore pray!

And take the thought of this calm vesper time,

With its low murmuring sounds and silvery light,

On through the dark days fading from their prime,

As a sweet dew to keep your souls from blight!

Earth will forsake-O! happy to have given

The unbroken heart's first fragrance unto Heaven.

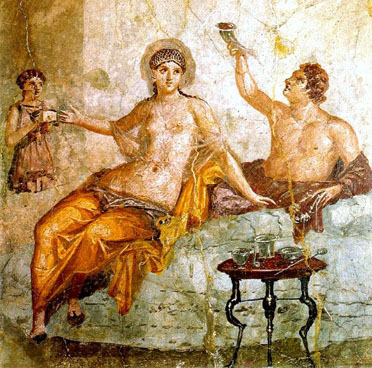

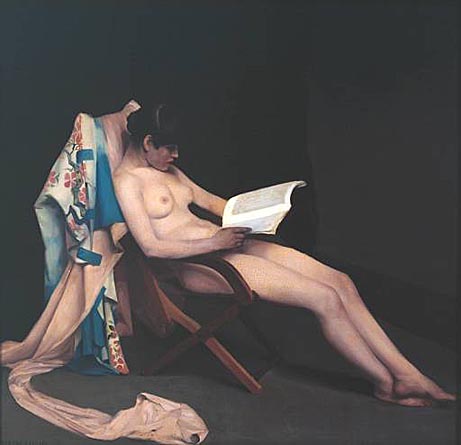

Associations with antique sculpture helped divorce the figure from any implication of sexuality. While some painters adopted the idea of archaeological reconstruction as a justification for the nude, others sought to emulate the general spirit of a lost Greek ideal.

Classicism enabled artists to explore more aesthetic treatments of the male nude, allowing for the projection of both male and female desire. At the same time, artists sought to purify the female figure by using male sculptural sources.

The classical nude was also significant in relaying ideas about hygiene, medicine and social evolution. The Greek ideal of the gymnasium helped sustain a male culture of athleticism, while the fuller proportions of Venus were held up as a model for natural womanhood, acknowledging women's traditional biological role but also encouraging more radical notions of female emancipation.

Technology drove social change throughout the Victorian era, and the development of photographic processes created a new demand for the nude which could not easily be controlled by obscenity legislation. Photography blurred the boundary between the real and the imagined body, offering an immediacy not possible in painting. Although some photographs were conceived as works of fine art, others were more explicitly pornographic, catering to heterosexual and homosexual fantasies.

The Pygmalion myth had a central role in Victorian thinking about the artist-model relationship, embodying fantasies about sexual temptation and men's desire for, and control of, women. The concept of man-made perfection also relates to a growing interest in theories of eugenics which promoted the belief that selected human breeding could lead to racial supremacy and the eradication of disease.

The rise of the 'sensational nude' was often seen to be associated with a perceived decline in public morals and with the influence of French art, and thus invited considerable opposition, particularly from religious and moral groups. The outbreak of a number of related moral panics in the mid-1880s, centered on the victimization of children, adolescents and women by abusive men, led to the nude being blamed as an incitement to vice and exploitation.

However, the politicization of the nude provoked by scandal and media exposure did little to restrict its visibility. Instead, sensationalism generated audience curiosity and with it a greater tolerance for the nude in the face of what was ultimately dismissed as philistine opposition.

Around the turn of the century the conventions of the idealized nude were challenged by new, naturalistic treatments of nakedness and by the desire to see the body placed in contemporary settings. These concerns led to the making of a painting from a model becoming an end in itself rather than a stage in the process of evolving a composition.

'Boudoir nudes' by cutting-edge young artists inspired by French realists such as Manet and Degas, presented the body in seedy domestic interiors that hinted at illicit sexual activity.

The vigorous, even aggressive, techniques adopted by some of these painters appeared in certain cases to besmirch and fragment the figure, offending conservative critics who perceived such works as alien (that is, French) and immoral.

Naturism

From the 1860s, but especially in the years around 1900, images of nudes in informal modern outdoor settings emerged as an important category in British art. Many of these advanced pictures were shown at dissident exhibiting societies such as the New English Art Club, established in 1886 as a direct challenge to the conservatism of the Royal Academy.

The representation of naked figures in the open air also connected with ideas about the benefits of fresh air, exercise and bathing, which were in themselves a response to reformist thinking about public health. Many painters and photographers showed boys or young men enjoying the sun or engaged in athletic sports, and although sometimes deriving from, and appealing to, homoerotic sensibilities, such scenes also reflect a universal longing for the untainted innocence and physical ease of gilded youth.

Source: Art Renewal Center

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.