Doménicos Theotokópoulos

Greek Mannerist Painter

1541 - 1614

El Greco ("The Greek") was a painter, sculptor, and architect of the Spanish Renaissance. He usually signed his paintings in Greek letters with his full name, Doménicos Theotokópoulos underscoring his Greek origin.

El Greco was born in Crete, which was at that time part of the Republic of Venice, and the center of Post-Byzantine art. He trained and became a master within that tradition before travelling at age 26 to Venice, as other Greek artists had done. In 1570 he moved to Rome, where he opened a workshop and executed a series of works. During his stay in Italy, El Greco enriched his style with elements of Mannerism and of the Venetian Renaissance. In 1577 he moved to Toledo, Spain, where he lived and worked until his death. In Toledo, El Greco received several major commissions and produced his best known paintings.

El Greco's dramatic and expressionistic style was met with puzzlement by his contemporaries but found appreciation in the 20th century. El Greco is regarded as a precursor of both Expressionism and Cubism, while his personality and works were a source of inspiration for poets and writers such as Rainer Maria Rilke and Nikos Kazantzakis. El Greco has been characterized by modern scholars as an artist so individual that he belongs to no conventional school. He is best known for tortuously elongated figures and often fantastic or phantasmagorical pigmentation, marrying Byzantine traditions with those of Western painting.

He was born in 1541 in either the village of Fodele or Candia (the Venetian name of Chandax, present day Heraklion) in Crete. El Greco was descended from a prosperous urban family, which had probably been driven out of Chania to Candia after an uprising against the Venetians between 1526 and 1528. El Greco's father, Geórgios Theotokópoulos (d. 1556), was a merchant and tax collector. Nothing is known about his mother or his first wife, a Greek woman. El Greco's older brother, Manoússos Theotokópoulos (1531 - December 13, 1604), was a wealthy merchant and spent the last years of his life (1603-1604) in El Greco's Toledo home.

El Greco received his initial training as an icon painter of the Cretan school, the leading center of post-Byzantine art. In addition to painting, he probably studied the classics of ancient Greece, and perhaps the Latin classics also; he left a "working library" of 130 books at his death, including the Bible in Greek and an annotated Vasari. Candia was a center for artistic activity where Eastern and Western cultures co-existed harmoniously, where around two hundred painters were active during the 16th century, and had organized a painters' guild, based on the Italian model. In 1563, at the age of twenty-two, El Greco was described in a document as a "master" ("maestro Domenigo"), meaning he was already a master of the guild and presumably operating his own workshop. Three years later, in June 1566, as a witness to a contract, he signed his name as Master Menégos Theotokópoulos, painter.

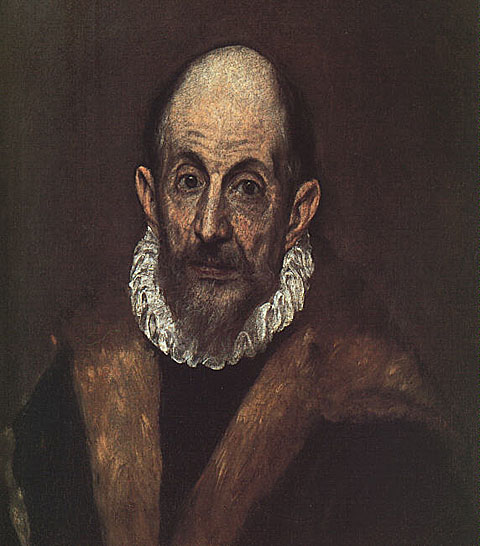

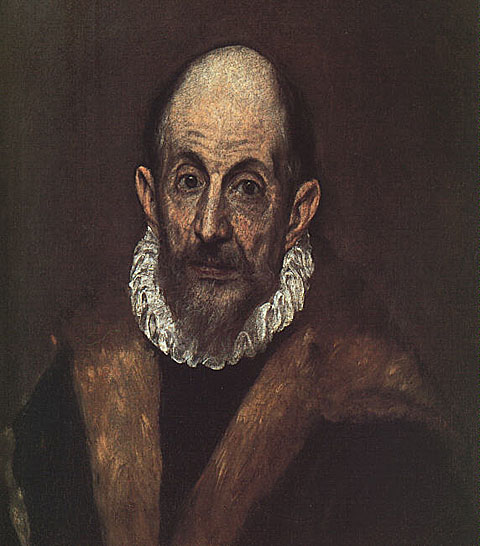

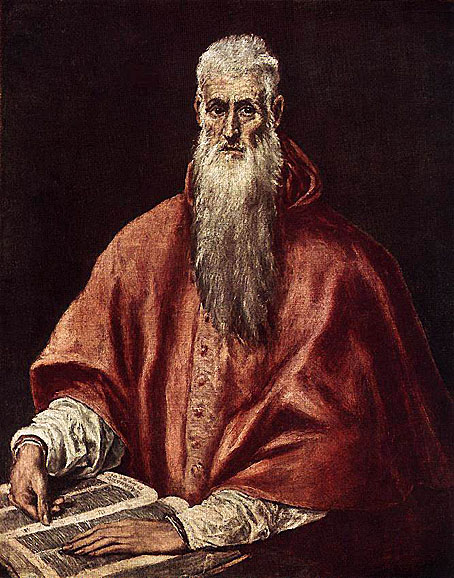

Senex Magister

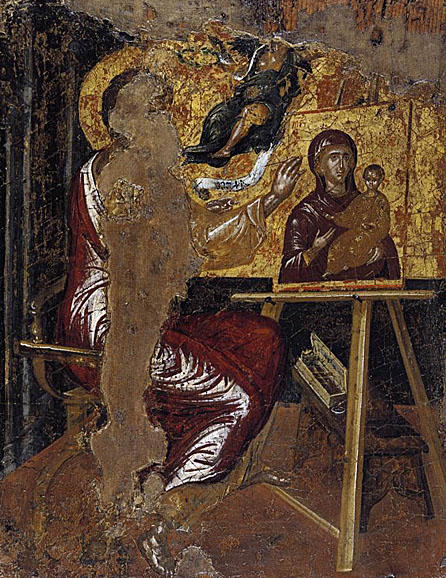

The icon, which retains its function as a cult object in the Church of the Dormition of the Virgin on the island of Syros in the Aegean Sea south-east of Athens, was probably brought to Syros during the Greek Revolution in 1824 from the Monastery of the Holy Mountain of the Dormition of the Virgin on the island of Psará in the Aegean. The icon conforms closely to the established pattern for this subject, which was very common in the Orthodox Church in which El Greco may have been raised.

El Greco kept strictly to the Byzantine canon in the representation of the icon on the easel, but he allowed himself greater freedom in the rest of the depiction. This icon is a transitional work that demonstrates how the artist was seeking to graft Renaissance elements (taken from Italian prints) on to Byzantine compositions.

Most scholars believe that the Theotocópoulos "family was almost certainly Greek Orthodox", although some Catholic sources still claim him from birth. Like many Orthodox emigrants to Europe, he apparently transferred to Catholicism after his arrival, and certainly practiced as a Catholic in Spain, where he described himself as a "devout Catholic" in his will.

Crete having been a possession of the Republic of Venice since 1211, it was natural for the young El Greco to pursue his career in Venice. Though the exact year is not clear, most scholars agree that El Greco went to Venice around 1567. Knowledge of El Greco's years in Italy is limited. He lived in Venice until 1570 and, according to a letter written by his much older friend, the greatest miniaturist of the age, the Croatian Giulio Clovio, was a "disciple" of Titian, who was by then in his eighties but still vigorous. This may mean he worked in Titian's large studio, or not. Clovio characterized El Greco as "a rare talent in painting".

In 1570 El Greco moved to Rome, where he executed a series of works strongly marked by his Venetian apprenticeship. It is unknown how long he remained in Rome, though he may have returned to Venice before he left for Spain. In Rome, on the recommendation of Giulio Clovio, El Greco was received as a guest at the Palazzo Farnese, which Cardinal Alessandro Farnese had made a center of the artistic and intellectual life of the city. There he came into contact with the intellectual elite of the city, including the Roman scholar Fulvio Orsini, whose collection would later include seven paintings by the artist (View of Mt. Sinai and a portrait of Clovio are among them).

Unlike other Cretan artists who had moved to Venice, El Greco substantially altered his style and sought to distinguish himself by inventing new and unusual interpretations of traditional religious subject matter. His works painted in Italy were influenced by the Venetian Renaissance style of the period, with agile, elongated figures reminiscent of Tintoretto and a chromatic framework that connects him to Titian. The Venetian painters also taught him to organize his multi-figured compositions in landscapes vibrant with atmospheric light. Clovio reports visiting El Greco on a summer's day while the artist was still in Rome. El Greco was sitting in a darkened room, because he found the darkness more conducive to thought than the light of the day, which disturbed his "inner light". As a result of his stay in Rome, his works were enriched with elements such as violent perspective vanishing points or strange attitudes struck by the figures with their repeated twisting and turning and tempestuous gestures; all elements of Mannerism.

By the time El Greco arrived in Rome, Michelangelo and Raphael were dead, but their example continued to be paramount and left little room for different approaches. Although the artistic heritage of these great masters was overwhelming for young painters, El Greco was determined to make his own mark in Rome defending his personal artistic views, ideas and style. He singled out Correggio and Parmigianino for particular praise, but he did not hesitate to dismiss Michelangelo's Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel; he extended an offer to Pope Pius V to paint over the whole work in accord with the new and stricter Catholic thinking. When he was later asked what he thought about Michelangelo, El Greco replied that "he was a good man, but he did not know how to paint". And thus we are confronted by a paradox: El Greco is said to have reacted most strongly or even condemned Michelangelo, but he had found it impossible to withstand his influence. Michelangelo's influence can be seen in later El Greco works such as the Allegory of the Holy League. By painting portraits of Michelangelo, Titian, Clovio and, presumably, Raphael in one of his works (The Purification of the Temple), El Greco not only expressed his gratitude but advanced the claim to rival these masters. As his own commentaries indicate, El Greco viewed Titian, Michelangelo and Raphael as models to emulate. In his 17th century Chronicles, Giulio Mancini included El Greco among the painters who had initiated, in various ways, a re-evaluation of Michelangelo's teachings.

Because of his unconventional artistic beliefs (such as his dismissal of Michelangelo's technique) and personality, El Greco soon acquired enemies in Rome. Architect and writer Pirro Ligorio called him a "foolish foreigner", and newly discovered archival material reveals a skirmish with Farnese, who obliged the young artist to leave his palace. On July 6, 1572, El Greco officially complained about this event. A few months later, on September 18, 1572, El Greco paid his dues to the Guild of Saint Luke in Rome as a miniature painter. At the end of that year, El Greco opened his own workshop and hired as assistants the painters Lattanzio Bonastri de Lucignano and Francisco Preboste.

By EL GRECO

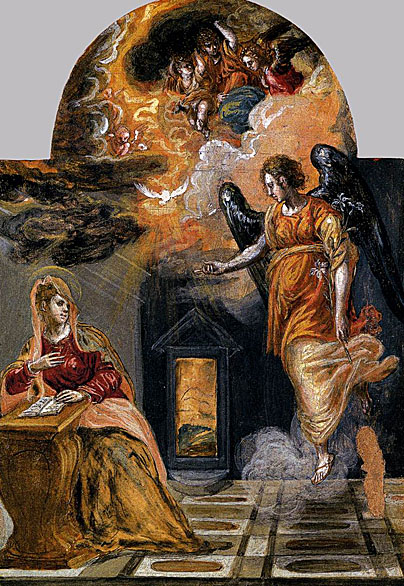

In 1567 El Greco decided to abandon a flourishing career on Crete for Venice and to become an Italian painter. It required a now mature master of Byzantine painting to acquire fluency in a naturalist style. In Venice, where he spent about three years before moving to Rome, he studied the works of the aged Titian and his successor, Tintoretto. After some small-scale compositions, such as the Modena Triptych and The Annunciation, he attempted the more complex Purification of the Temple, the first full-blown work in the Venetian manner.

_1568_Venice.jpg)

The central panel on the front, showing the Christian Knight received into Heaven, with Purgatory and Inferno below, and the three Theological virtues, is of medieval inspiration, and precisely follows a known representation of the subject. The Jaws of Hell are a specifically medieval motif. Saint Catherine, with the Wheel of her Martyrdom, appears below the figures of Christ and the Knight. The theme of Mount Sinai, on the back of the central panel, was of Cretan origin, and faithfully repeats a traditional Byzantine model. The reference to Saint Catherine in both the central panels has been suggested as a possible indication of the artist's connection in Crete with the monastery of Saint Catherine, a dependency of that of Mount Sinai, and the most important school of painting in the island. The other compositions are similarly not original, but here the artist has used engravings after Italian (mainly Venetian) compositions as his models. The repetition of traditional images was usual in Byzantine art.

The Triptych is interesting as one of the earliest known work by El Greco. It clearly belongs to the time soon after his arrival in Italy. We see the artist acquainting himself with the new Italian subject matter and its treatment, and making his first essays in the new technique of Venice. The flat, linear, geometrical designs of Byzantine art give way to compositions employing rounder, more solid forms, and a looser handling. The somewhat nervous quality may be regarded as El Greco's own, and the Triptych does contain motifs and compositions that he later develops. The subjects of the Annunciation, Adoration of the Shepherds and Baptism inspire some of El Greco's grandest works. The Allegory of the Christian Knight is appropriately recollected in the Allegory of the Holy League. The Byzantine image of Mount Sinai is not unreasonably brought to mind in front of the late Toledo.

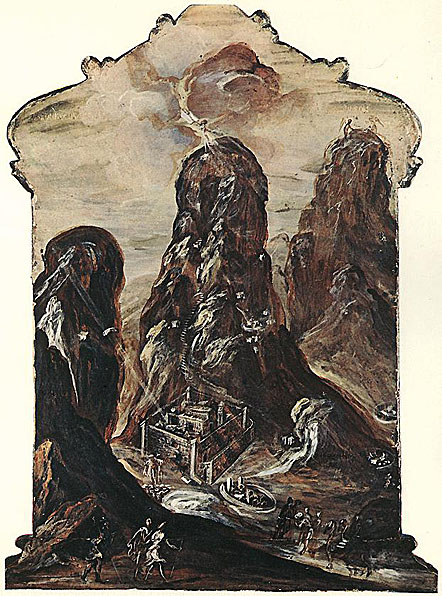

The Modena Triptych strikingly illustrates El Greco's transition from post-Byzantine icon painter to European artist of the Latin variety. The portable altarpiece, whose unknown patron perhaps stemmed from a Creto-Venetian family, in its open state shows a total of six scenes: on the front, the central panel bears a rare depiction of the Coronation of the Christian Knight, and on the wings we find the Adoration of the Shepherds on the left and the Baptism of Christ on the right. On the reverse, a View of Mount Sinai with its famous convent of St Catherine is flanked by an Annunciation and an Admonition of Adam and Eve by God the Father. This type of object with its gilded frame elements was common in Cretan workshops of the 16th century, as is its use of wood as a painting support.

_1568_Venice.jpg)

The theme of Mount Sinai, on the back of the central panel, was of Cretan origin, and faithfully repeats a traditional Byzantine model. The picture shows pilgrims on the way to the Monastery, and the Mountain as the Road to Heaven. The reference to Saint Catherine in both the central panels has been suggested as a possible indication of the artist's connection' in Crete with the monastery of Saint Catherine, a dependency of that of Mount Sinai, and the most important school of painting in the island. The other compositions are similarly not original, but here the artist has used engravings after Italian (mainly Venetian) compositions as his models. The repetition of traditional images was usual in Byzantine art.

The Modena Triptych strikingly illustrates El Greco's transition from post-Byzantine icon painter to European artist of the Latin variety. The portable altarpiece, whose unknown patron perhaps stemmed from a Creto-Venetian family, in its open state shows a total of six scenes: on the front, the central panel bears a rare depiction of the Coronation of the Christian Knight, and on the wings we find the Adoration of the Shepherds on the left and the Baptism of Christ on the right. On the reverse, a View of Mount Sinai with its famous convent of St Catherine is flanked by an Annunciation and an Admonition of Adam and Eve by God the Father. This type of object with its gilded frame elements was common in Cretan workshops of the 16th century, as is its use of wood as a painting support.

The Modena Triptych does contain motifs and compositions that he later develops. The subjects of the Annunciation, Adoration of the Shepherds and Baptism inspire some of El Greco's grandest works. The Allegory of the Christian Knight is appropriately recollected in the Allegory of the Holy League. The Byzantine image of Mount Sinai is not unreasonably brought to mind in front of the late Toledo.

According to the X-radiograph the upper part of the canvas was completely repainted, and the canvas has been cropped at the top.

This is the earliest known version of this subject by El Greco. It has usually been dated to El Greco's Venetian years, although some scholars have placed it to his time in Rome. The artist borrowed extensively from High Renaissance visual models (among others from Michelangelo, Titian, Veronese and Tintoretto) and did very little to disguise them. Uncertainties in the handling of anatomy and space can be observed which confirm the early date of the painting.

Three versions of this subject are known, all basically the same in composition, but differing in treatment. The earliest, an unsigned panel in Dresden, is looser in composition, smaller in conception, and introduces genre motifs of a dog, sack and pitcher in the foreground, eliminated in subsequent versions. The present painting, probably also painted in Venice, is more easily composed. The third and largest painting, now in the Metropolitan Museum in New York (possibly identical with the one in a Madrid collection at the time of Cossio's pioneer work on El Greco), with its comparative largeness of conception, belongs to his Roman period, after 1570. El Greco did not again take up the subject in Spain.

The inspiration is from Venice. The dramatic use of recession behind the figures in the foreground is Tintoretto's invention. El Greco is still borrowing certain motifs, but the composition would seem to be original. The painting was among the Farnese possessions in the seventeenth century, and was probably brought to Rome by the artist, unless it was painted soon after his arrival in 1570. The figure on the extreme left, looking out towards the spectator, is certainly the young El Greco. He appears, however, nearer twenty than thirty years old.

By EL GRECO

In Rome, El Greco studied the works of Michelangelo and Raphael. Despite the lack of support (no patrons or public commissions), he improved his art, and the result can be seen in a second version of the Purification of the Temple. The influence of Michelangelo is reflected in the first and second version of the Pietà composition. During his Roman stay El Greco portrayed Giulio Clovio, the miniaturist, for friendship.

The portrait was painted probably soon after El Greco arrived in Rome (November 1570), and almost certainly for his friend. In the seventeenth century, it was in the possession of Fulvio Orsini, librarian to Cardinal Farnese. This is perhaps the earliest independent portrait by the artist who was to become one of the greatest portrait painters of all time. Three splendid portraits belong to his Italian years: the present portrait, possibly the earliest, and the signed portrait of a man in Copenhagen, both Titianesque; and the more personal Vincentio Anastagi, a signed portrait in the Frick Collection, New York. It is unfortunate that the self-portrait mentioned by Giulio Clovio is lost.

The St Catherine's Monastery is venerated as the spiritual home of Byzantine Orthodoxy and it was a great center of pilgrimage. In the painting, on the left are three Western pilgrims, while on the right is a group of Eastern pilgrims with camels.

The view of the holy site is based on engravings of Mount Sinai which could be found in travel books. El Greco painted a similar view on the reverse of the Modena Triptych.

The version in New York is the most sketchy in execution and is, in fact, unfinished. The two seated figures in the middle ground were so thinly painted that the pavement is visible through them.

Until recently there was a consensus of opinion that the New York version was the latest of the three treatments of the subject and possibly dated from El Greco's first years in Spain. However, in 1991 a number of scholars dated it between the Dresden and Parma pictures. The question of date is still open.

The armour, sword, helmet, the green baldric and velvet breeches ornamented with gold thread, are the attributes of his station. Yet El Greco has not confined himself to replicating these particulars. He has sought to make manifest Anastagi's body politic as well - in particular the cardinal virtue of fortitude, comprising courage, endurance and physical strength.

In spite of the qualities of the portrait, the paucity of the extant and recorded portraits which El Greco painted in Rome suggests that commissions were not forthcoming, probably because his Titianesque technique was not appreciated.

The subject of a boy blowing on an ember appears frequently as a subsidiary element in subject pictures in mid-sixteenth-century Venetian painting.

The four portraits at the bottom right represent, from left to right, Titian, Michelangelo, Giulio Clovio and possibly El Greco himself. The introduction of Titian and Michelangelo is clearly an acknowledgment of his debt to these two artists. To his friend, Giulio Clovio, he owed his introduction to the Farnese household. The young man looking out, pointing to himself, has similar features to the self-portrait in the Christ healing the Blind at Parma, but the long hair is strange. It has also been suggested that he could represent the young Raphael. The portraits of Titian and Michelangelo (died 1564) were taken from existing portraits, and that of Giulio Clovio follows closely El Greco's portrait of his friend in the Naples Museum, painted c. 1571. El Greco does continue to include portraits in his paintings of religious subjects, but here there is no proper connection with the subject matter.

_1571_76_Rome.jpg)

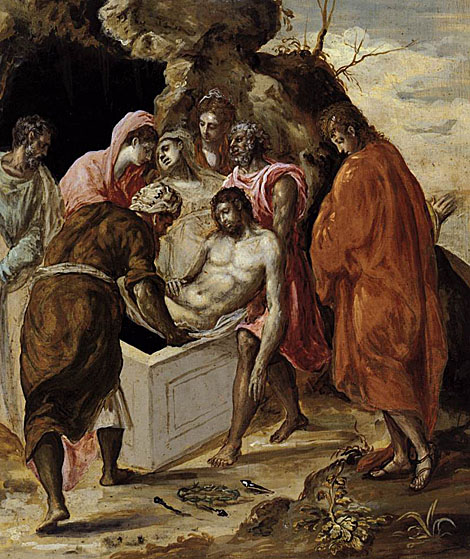

Michelangelo's Pietà group was not the only source on which El Greco drew: the arrangement of Christ's legs and his outspread arms, no less than the idea of viewing one of the two bearers of his body from the side and the other from behind, derive from Michelangelo's drawing for Vittoria Colonna, in which, as in El Greco's painting, the Virgin is placed behind and above Christ.

In the collection of the Hispanic Society of America is a larger version of the subject, unsigned, in oil on canvas, for which this may be a study. The subject is not repeated in Spain.

El Greco probably painted the portrait in Rome several years after moving there in November 1570. It reflects El Greco's association with intellectuals. The only clues to the identity of the sitter are the book and the drawing instrument beside it. He makes an eloquent gesture characteristic for an orator.

In 1577, El Greco emigrated first to Madrid, then to Toledo, where he produced his mature works. At the time, Toledo was the religious capital of Spain and a populous city with "an illustrious past, a prosperous present and an uncertain future". In Rome, El Greco had earned the respect of some intellectuals, but was also facing the hostility of certain art critics. During the 1570s the huge monastery-palace of El Escorial was still under construction and Philip II of Spain was experiencing difficulties in finding good artists for the many large paintings required to decorate it. Titian was dead, and Tintoretto, Veronese and Anthonis Mor all refused to come to Spain. Philip had had to rely on the lesser talent of Juan Fernándes de Navarrete, whose gravedad y decoro ("seriousness and decorum") the king approved. However, he had just died in 1579; the moment should have been ideal for El Greco. Through Clovio and Orsini, El Greco met Benito Arias Montano, a Spanish humanist and agent of Philip; Pedro Chacón, a clergyman; and Luis de Castilla, son of Diego de Castilla, the dean of the Cathedral of Toledo. El Greco's friendship with Castilla would secure his first large commissions in Toledo. He arrived in Toledo by July 1577, and signed contracts for a group of paintings that was to adorn the church of Santo Domingo el Antiguo in Toledo and for the renowned El Espolio. By September 1579 he had completed nine paintings for Santo Domingo, including The Trinity and The Assumption of the Virgin. These works would establish the painter's reputation in Toledo.

By EL GRECO

El Greco left Rome to find in Spain the patronage that had eluded him in Rome. He had hopes of working for Philip II who was then actively recruiting painters to work at the Escorial. The Adoration of the Name of Jesus must certainly have been made for Philip II, but no documents refer to a commission. The first commission came from the Cathedral of Toledo, for the Disrobing of Christ, the first masterpiece of the artist. The large Martyrdom of St Maurice was commissioned by Philip II, late 1570 or early 1580, for the chapel of the Saint in the church of the Escorial.

_1577_79_Spain.jpg)

_Detail_Spain.jpg)

The painting shows Christ clad in a bright red robe and looking up to Heaven with an expression of serenity as he is being tormented by his captors. A figure in the background bearing a red hat points at Christ accusingly, while two others argue over his garments. A man in green to Christ's left holds him firmly with a rope and is about to rip off his robe in preparation for his crucifixion. At the lower right, a man in yellow bends over the cross and drills a hole to facilitate the insertion of a nail to be driven through Christ's feet. The clouds above Christ, painted in strong diagonals, provide a 'path' of uplifting communication between Christ and God the Father. On the left side of the composition, the three Marys contemplate the event with distress. Above them a soldier wearing a suit of armor reminiscent of those fabricated in sixteenth-century Toledo stares out directly at the viewer. El Greco may have intended this figure to be a contemporary portrait.

A small, signed version of the Espolio, at Upton Park, Warwickshire, the original preliminary model is probably for the large painting. Many other versions exist, but few can be by El Greco. The only occasion that he treated the subject was for the Cathedral, but the type of Christ created in the Espolio is taken up in the related subject of Christ carrying the Cross, and in other representations of Christ.

The initial reception of the painting, when seen by the artists brought to value it, was that it was beyond appraisal. After the artist's death, the first real recognition of the painting was some two centuries later when Goya painted his Taking of Christ for the same sacristy.

The subject, then, is the Adoration of the Name of Jesus, a Jesuit counterpart of the Adoration of the Lamb, and incorporates the 'Church Militant', represented by the Holy League. The Name of Jesus is represented by the trigram IHS with a cross above that appears in a burst of glory at the top of the composition. The painting has also been called An Allegory of the Holy League because of the presence of the main participants of the Holy League. The popular title, the 'Dream of Philip II', is more recent.

The painting must certainly have been made for Philip II, but no documents refer to it and it is strangely not mentioned by Sigüenza in his description of the Escorial, published in 1608. The occasion of the commission may well have been the death of Juan of Austria in 1577, and the translation of his body to the Pantheon in 1578. The painting was in the Pantheon when los Santos described it. Juan of Austria was the general in charge of the forces of the Holy League at the victory of Lepanto in 1571.

The three members of the Holy League, Spain, Venice and the Papal States are represented by the three kneeling figures of Philip II, Doge Mocenigo and Pope Pius V, and the one prominent figure of the foreground group, kneeling in heroic pose, and holding a sword, can represent no other than the general in charge at Lepanto. It is an ideal representation, while the King, Pope and Doge are actual portraits. Sir Anthony Blunt first suggested that this Adoration of the Name of Jesus was an allegory of the Holy League (the 'Church Militant'), and was possibly commissioned for the tomb of the Spanish General in the Pantheon. That is, it was more in the nature of a private commission for the King, and not part of the scheme of decoration of the Escorial. This could explain the absence of documents.

The spirit of universal adoration is brilliantly conveyed. For the general arrangement of the painting, El Greco seems, appropriately, to have referred to his Allegory of a Christian Knight, of the Modena Triptych. The figures of the King, Pope, Doge and Juan of Austria take the place of the three Theological Virtues. The Jaws of Hell and the representation of Purgatory are very similar. The figure of Don Juan of Austria is inspired by Michelangelo. So special a commission could hardly have been the subject of a test-piece for the Escorial as has generally been suggested. The Martyrdom of Saint Maurice and His Legions was a specific commission (and the only commission) for the Escorial.

The story of St Maurice (a legendary warrior saint, the commander of the 'Theban Legion', Roman troops from Thebes in Egypt, who served at Agaunum in Gaul (St-Maurice en Valais) in the 3rd century) relates that the soldiers, at the instigation of Maurice, refused to participate in certain pagan rites. They were punished by the Emperor Maximian Herculeus first by decimation and finally by the wholesale massacre of the legion. Maurice and his fellow officers were executed in A.D. 287. The authenticity ot the story is debated.

The subject of the martyrdom of the soldier Saint with his legions, for his refusal to worship the pagan gods was appropriate for the Escorial, the real center of the crusade for the Faith. This subject expresses the conviction of faith that inspired the crusade; the Allegory of the Holy League, the militant spirit of the crusade itself. The ecstatic character of this 'invitation to death' (Ortega y Gasset) is expressed. The physical side of the martyrdom is not emphasized, is no more than symbolized by the small group on the left comprising the one martyred figure, the figure, in the pose of his Christ of the Baptism, awaiting martyrdom and the grand figure in back-view of the executioner. The impression of the ranks of the Saint's army awaiting martyrdom is similar to that of the multitude in adoration in the Adoration of the Name of Jesus. The two paintings are related in composition, and in their expression of devotional fervor.

The sitter is depicted as a practitioner of a liberal art. He is elegantly and modestly dressed in black. His dark, penetrating eyes and high brow imply his intellectual capacity. The hammer is poised to suggest his mental deliberation. El Greco has ingeniously applied the conventional formula of the self-portrait, in which the artist turns to face the viewer while working at the easel. Wittily, the viewer can imagine the sculptor looking at the sitter (Philip II) posing for his bust portrait.

The portrait was surely known by Velázquez, whose 1635 portrait of the great Seville sculptor Juan Martínez Montañés seems to reflect it.

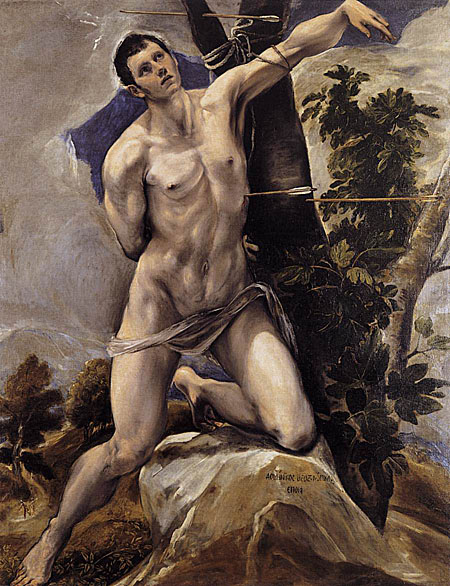

The Saint abandoned after his martyrdom and presumed death. The style is that of around 1580. The frontal placing of the nude figure and treatment of the forms avoids a three-dimensional emphasis. The greater prominence of the setting - and of actual depth, in the vista on the right - compared with the paintings for Santo Domingo, the Cathedral and the Escorial, depends on the subject. In comparable representations of Saints, as of the Magdalene or Saint Jerome in the wilderness, he continues to indicate a setting. Where the image alone is demanded, as in his series of Apostles, a setting is omitted. In this painting the forms of tree and rock and the silhouette of the foliage are made to continue the plane of the figure. It is perhaps the natural sequence in the process of dematerialization that the more flexible elements, the draperies, preceded the nude figure and natural forms.

El Greco did not use the pose again for a Saint Sebastian. A related figure is the Christ in the Prado Baptism of some fifteen to twenty years later; the Saint Jerome of his last year shows the culmination of this development. The compositional motif of the pose, with the outstretched leg taking the movement upwards appears in the Adoration of the Shepherds of similar date, and indeed in El Greco's work is first met in the Adoration of the Modena Triptych.

_1577_79_Spain.jpg)

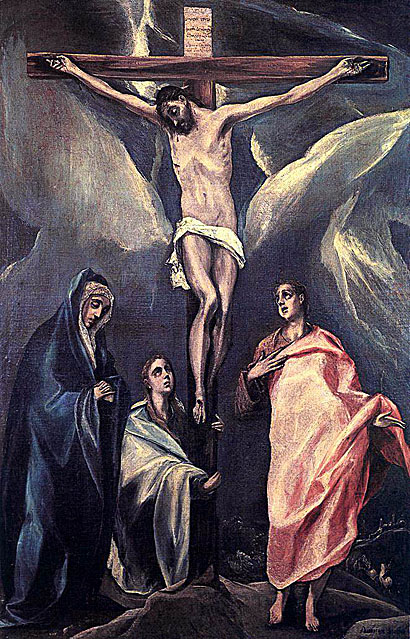

The influence of Michelangelo - whose works El Greco would have known in Rome - is recognized in the depiction of the naked Christ. In fact, the posture and anatomy of El Greco's Christ echo in reverse Michelangelo's drawing for Vittoria Colonna.

El Greco did not plan to settle permanently in Toledo, since his final aim was to win the favor of Philip and make his mark in his court. Indeed, he did manage to secure two important commissions from the monarch: Allegory of the Holy League and Martyrdom of St. Maurice. However, the king did not like these works and placed the St Maurice altarpiece in the chapter-house rather than the intended chapel. He gave no further commissions to El Greco. The exact reasons for the king's dissatisfaction remain unclear. Some scholars have suggested that Philip did not like the inclusion of living persons in a religious scene; some others that El Greco's works violated a basic rule of the Counter-Reformation, namely that in the image the content was paramount rather than the style. Philip took a close interest in his artistic commissions, and had very decided tastes; a long sought-after sculpted Crucifixion by Benvenuto Cellini also failed to please when it arrived, and was likewise exiled to a less prominent place. Philip's next experiment, with Federigo Zuccaro was even less successful. In any case, Philip's dissatisfaction ended any hopes of royal patronage El Greco may have had.

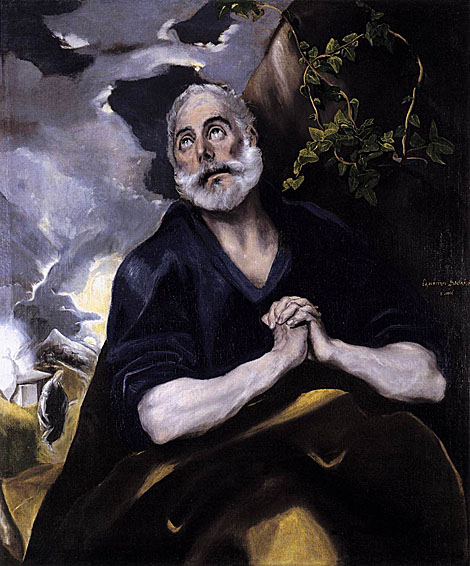

By EL GRECO

In addition to major altarpieces, El Greco did a booming trade in devotional pictures. Although rarely documented, these work supplied the artist's daily bread and were produced by him and his workshop in impressive quantities. It appears that he had a sort of sample case which could be shown to prospective customers, who would choose from reduced versions stored in a small room. The reason for the popularity of El Greco's devotional paintings is obvious: they are brilliantly rendered, and they also capture the piety and emotion of Counter-Reformation spirituality. Examples are St Peter in Penitence, and Mary Magdalen in Penitence.

The roses, iris, olive, palm, portal and throne all belong to the iconography of the Immaculate Conception. The twelve stars have been omitted. This subject, related in composition to that of the Assumption of the Virgin, with which it is sometimes confused, was more suited to El Greco's genius, more in sympathy with the expression of the purely supernatural image. In Spain, he avoids anything that can be related to mundane actions or events, which would detract from the expression of the supernatural. The rather angular and schematic quality of the design is appropriate to the image, and captures something of the grand effect of Byzantine designs. The mandorla shape, belonging to this image - the clothing with the sun - is again introduced effectively in the Burial of the Count of Orgaz. The general pattern is retained in the splendid late painting in the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid. The subject inspired the great masterpiece of his last years.

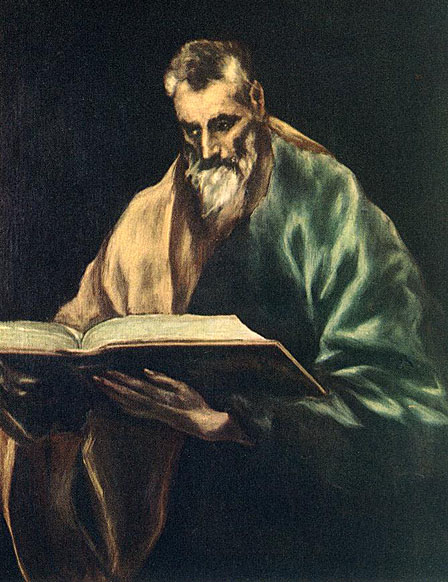

St Peter appears a great number of times in El Greco's oeuvre and he is depicted with remarkable consistency. The saint is always shown with white hair and beard, and he often wears his yellow cloak over a blue tunic.

By EL GRECO

In addition to major altarpieces, El Greco did a booming trade in devotional pictures. Examples from this period are St Francis Receiving the Stigmata,, Mary Magdalen in Penitence, St Dominic in Prayer, and Christ Carrying the Cross.

_1588_89_Spain.jpg)

The crucifix, propped against the rocks, is repeated by El Greco in a number of paintings showing saints in devotion: he must have created a drawn or painted model that he could refer to for replication.

The Agony in the Garden testifies to an astonishing development of the artist. The Italian influences recede to the same degree as El Greco frees himself from his obligation to nature. The figures lose their sense of substance, while their expressiveness is amplified by the unreal shapes assumed by the landscape. Thus Christ is literally heightened by the rock behind him, while the disciples are seen in a sheltering cave as a symbol of sleep. The figures are absolved from logical relationships of scale. The falling diagonal which leads from an angel, through Christ, to the soldiers on the right-hand edge of the painting is a visual statement of the inevitability of Christ's fate. Such departures from the natural model, also evident in the visionary apparition of the moon, were one of the major reasons for the revival of interest in El Greco's work around 1900.

By EL GRECO

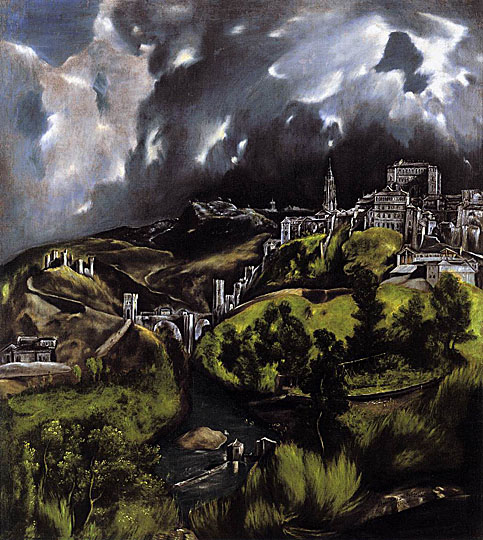

El Greco created his extraordinary landscape, the View of Toledo, in the second half of the 1590s. This is one of the earliest independent landscapes in Western art and one of the most dramatic and individual landscapes ever painted.

It is supposed that the head of Mary is a portrait of Doña Jerónima de las Cuevas while that of St Joseph is a self-portrait of the artist.

Both in here and in the View and Plan the city is shown from the north, except that El Greco has included only the easternmost portion, above the Tagus river. This partial view would have excluded the cathedral, which he therefore imaginatively moved to the left of the dominant Alcázar or royal palace. The fact that an identical view appears in the Saint Joseph and the Christ Child in the Capilla de San José suggests that the painting was conceived in connection with the San José commission (1597-99). From that time, the town features in many of his paintings: in the Laocoön (National Gallery of Art, Washington), the Christ in Agony on the Cross (Cincinnati Art Museum), the Virgin of the Immaculate Conception (Museo de Santa Cruz), in all of which it takes on an apocalyptical character appropriate to the themes. In his late Saint John the Baptist (Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco) the landscape of the Escorial is appropriately introduced.

This is one of the earliest independent landscapes in Western art and one of the most dramatic and individual landscapes ever painted. It is not just a 'View of Toledo', although the topographical details are correct; neither is it 'Toledo at night' or 'Toledo in a storm', other titles which have been attached to the painting: it is simply 'Toledo', but Toledo given a universal meaning - a spiritual portrait of the town. In introducing the view into his paintings he acknowledges how much his art owed to the inspiration of the town, until a few years before the great Imperial Capital and still the great ecclesiastical and cultural centre of Spain - the town isolated on the plain of Castile which he had made his new home, so far from the island of his birth.

In the painting the ideal monastic settlement is depicted: we see individual hermitages or cells, each with their own garden, built around a central chapel with a common building and fountain near the entrance gate. The community, sited on a mountainous plateau, is enclosed by a dense forest.

Lacking the favor of the king, El Greco was obliged to remain in Toledo, where he had been received in 1577 as a great painter. According to Hortensio Félix Paravicino, a 17th-century Spanish preacher and poet, "Crete gave him life and the painter's craft, Toledo a better homeland, where through Death he began to achieve eternal life." In 1585, he appears to have hired an assistant, Italian painter Francisco Preboste, and to have established a workshop capable of producing altar frames and statues as well as paintings. On March 12, 1586 he obtained the commission for The Burial of the Count of Orgaz, now his best-known work. The decade 1597 to 1607 was a period of intense activity for El Greco. During these years he received several major commissions, and his workshop created pictorial and sculptural ensembles for a variety of religious institutions. Among his major commissions of this period were three altars for the Chapel of San José in Toledo (1597-1599); three paintings (1596-1600) for the Colegio de Doña María de Aragon, an Augustinian monastery in Madrid, and the high altar, four lateral altars, and the painting St. Ildefonso for the Capilla Mayor of the Hospital de la Caridad (Hospital of Charity) at Illescas (1603-1605). The minutes of the commission of The Virgin of the Immaculate Conception (1607-1613), which were composed by the personnel of the municipality, describe El Greco as "one of the greatest men in both this kingdom and outside it".

By EL GRECO

No picture better demonstrates the essence of El Greco's art than his most famous, The Burial of the Count of Orgaz, which was painted for his own parish church, Santo Tomé. Gonzalo Ruiz de Toledo, Count of Orgaz, was a Toledan nobleman who had lived in the fourteenth century and acquired a renown as a donor to religious institutions. Before he died, he had willed certain rents from the village of Orgaz to the church of Santo Tomé, where he had elected to be buried. In 1586 the parish priest initiated a project to refurbish the count's burial chapel, and commissioned El Greco to paint what has to be considered as his masterpiece.

The most striking aspect of the composition is the juxtaposition of the imaginative vision of heaven with the burial scene, in which all the figures are garbed in contemporary costumes and presumably represent distinguished citizens of Al Greco's Toledo. The dichotomy in style between the upper and lower parts is one of the most remarkable feature of the painting. In the lower zone, El Greco meticulously reproduces the appearances of persons and objects. The heavenly scene, by contrast is far more abstracted. This peculiar synthesis of real and super-real is essential to El Greco's art.

The painting illustrates a popular local legend. In 1312, a certain Don Gonzalo Ruíz, native of Toledo, and Señor of the town of Orgaz, died (the family received the title of Count, by which he is generally known, only later). He was a pious man who, among other charitable acts, left moneys for the enlargement and adornment of the church of Santo Tomé (El Greco's parish church). At his burial, Saint Stephen and Saint Augustine intervened to lay him to rest. The occasion for the commission of the painting for the chapel in which the Señor was buried, was the resumption of the tribute payable to the church by the town of Orgaz, which had been withheld for over two centuries.

The painting remains in the chapel - the actual scene of the event - for which it was ordered. Already in 1588, people flocked to see the painting. This immediate popular reception depended, however, on the 'life-like portrayal of the notable men of Toledo of the time'. Indeed, this painting is sufficient to rank El Greco among the few great portrait painters. Nowadays the painting can communicate to us a whole society and age, as perhaps no other single work of art can, and at the same time offer us one of the great marvels of painting.

It was the custom for the eminent and noble men of the town to assist at the burial of the high-born, and it was stipulated in the contract that the scene should be represented in this way. Without the contemporary confirmation, it would be clear that all are portraits. Unfortunately, there is no record of the identity of the sitters. Andrés Núñez, the parish priest, and a friend of El Greco's, who was responsible for the commission, is certainly the figure on the extreme right. The artist himself can be recognized in the caballero third from the left, immediately above the head of Saint Stephen. The artist's son acts as the young page. The signature of the artist appears on the handkerchief in the pocket of the young boy, and by a strange conceit it is followed by the date '1578' - the year of Jorge Manuel's birth, and certainly not the date of the painting. The boy points to the body of the deceased, thus bringing together birth and death.

The painting is very clearly divided into two zones, the heavenly above and the terrestrial below, but there is little feeling of duality. The upper and lower zones are brought together compositionally (e.g., by the standing figures, by their varied participation in the earthly and heavenly event, by the torches, cross . . .). The grand circular mandorla-like pattern of the two Saints descended from Heaven echoes the pattern formed by the Virgin and Saint John the Baptist, and the action is given explicit expression. The point of equilibrium is the outstretched hand poised in the void between the two Saints, whence the mortal body descends, and the Soul, in the medieval form of a transparent and naked child, is taken up by the angel to be received in Heaven. The supernatural appearance of the Saints is enhanced by the splendor of color and light of their gold vestments. The powerful cumulative emotion expressed by the group of participants is suffused and sustained through the composition by the splendor, variety and vitality of the color and of light.

This is the first completely personal work by the artist. There are no longer any references to Roman or Venetian formulas or motifs. He has succeeded in eliminating any description of space. There is no ground, no horizon, no sky and no perspective. Accordingly, there is no conflict, and a convincing expression of a supernatural space is achieved. This is the beginning of his real development, and the process of dematerialization and spiritualization continues.

By EL GRECO

The Colegio de Nuestra Señora de la Encarnacion (College of Our Lady of the Incarnation), also known as the Colegio de Doña María de Aragón, was an Augustinian seminary in Madrid for the training of priests. Construction of the church began in 1581 and El Greco - who was resident in Toledo and had relatively few contacts in Madrid - was fortunate to obtain the contract for the main altarpiece. The agreement between the painter and the Council of Castile was signed in December 1596 and required El Greco to deliver the altarpiece (including carpentry, sculptures and gilding) by Christmas 1599. The altarpiece was eventually completed in July 1600.

The Doña María de Aragón altarpiece was the most important commission El Greco received and he was paid just under 6000 ducats for it, a vast sum, and more than he earned for any other work. It was here that he first fully realised the traits of his late, 'mystical' style - elongated forms, flickering effects of light, colour combinations that verge on dissonance (copper-resinate green, rose-to-magenta, golden yellow and blue), and an emphasis on ecstatic gestures and expressions.

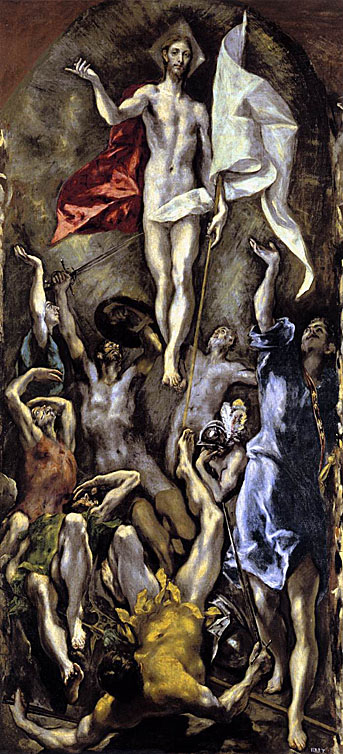

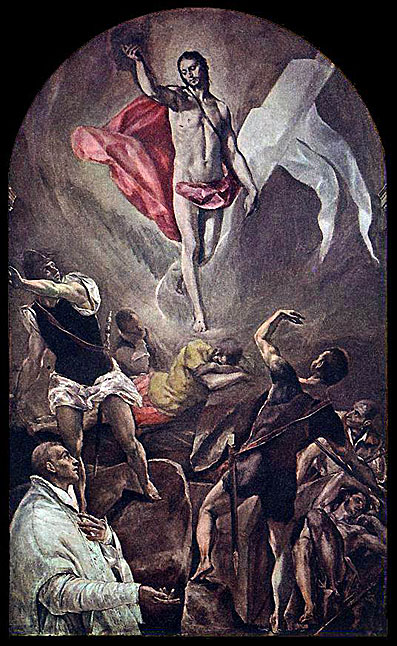

The altarpiece was dismantled in 1810, following the suppression by Joseph Bonaparte of the religious orders in Spain. No detailed description of it survives, but according to a document of 1814 it comprised seven paintings and six sculptures. There has been much debate in recent years over the altarpiece's original appearance, but there is considerable agreement that it comprised five paintings today in the Prado, The Resurrection, The Crucifixion, The Pentecost, The Baptism of Christ and The Annunciation, and a sixth, The Adoration of the Shepherds, in Bucharest. The seventh painting is presumed lost and it has been suggested that it may have been a Coronation of the Virgin.

At the bottom of the canvas, the terrestrial world is barely indicated by the steps, sewing basket and rose-bush in flame. The flames are rendered so naturalistically that they probably have appeared to mirror the real candle flames burning on the altar during the celebration of the Mass. But above and beyond El Greco has distorted light, color and form. Indeed, all the forms are in a state of flux. The grand rhythm of the wings of Gabriel and the Holy Spirit quicken the drama. Garments of crystalline blue, crimson and yellow-green vibrate against the blue-grey void. Incandescent light is reflected off the figures with such intensity that each seems to be its own source of light.

A comparison with the earlier painting of the same subject in Santo Domingo shows the advance made in the process of developing a style appropriate to the expression of the supernatural. There is no reference to the ordinary conception of space of this world, there are no allusions to the corporal quality of the figures, whose gestures also belong to the realm of imagination and not to that of ordinary experience. Light is the important dematerializing and expressive element in this painting. The Santo Domingo painting can still be related to a human event.

The retable no longer exists, and the paintings are dispersed. The subjects of the paintings of the retable are not recorded, but it is assumed that they illustrated the Life of Christ. For reasons of size, style, and subject matter, the following paintings probably came from the retable: the Annunciation, the widest painting, in the centre (the church was dedicated to the Virgin of the Annunciation); the Adoration of the Shepherds and the Baptism of Christ, two paintings of the same size, on the left and right of the Annunciation; the Crucifixion above the Annunciation; and the Resurrection and Pentecost, another pair of identical size, flanking the Crucifixion (the whole forming a retable of a type known in the Escorial). Such an arrangement gives a chronological sequence to the events of the Life of Christ. The payment of 6000 ducados (for the paintings and retable) indicates a large commission. Small versions, probably models, exist for the three paintings more generally accepted as belonging to the retable, the Annunciation, the Adoration of the Shepherds and the Baptism of Christ.

Probably originally on the right of the retable of the Colegio de Doña María, balancing the Adoration of the Shepherds, and painted at the same time. A small version, possibly the model for the large painting, is in the Galleria Corsini, Rome. A later development of this subject, only treated once before, in the Modena Triptych, is the painting for the Hospital de San Juan Bautista, Toledo, probably completed after his death by Jorge Manuel. The pose of the Christ is related to that of the Saint Sebastian of c. 1580. The bipartite composition can be related to the Burial of the Count of Orgaz, the portraits giving place to the range of angels. The splendid ecstatic figure of the angel, between the Baptist and Christ, is one of a number of such symbols that he began to introduce into his painting. If his figures - the actual participants in the action - become increasingly dematerialized, these new symbols appear as emotions materialized in gesture and color.

Already, in Santo Domingo el Antiguo, the artist had sensibly related together in composition the two central paintings of the high altar, the Assumption and Trinity. Again, there is this compositional relationship of the two paintings, but there is also something more in this bringing together of the two so diverse yet intimately related themes of the Virgin's reception of the Holy Ghost, and Christ's giving up of the Holy Ghost. One subject represents one of the Joys of the Virgin, and the other incorporates one of Her Grief's. Each painting is divided horizontally in three. The figure of Christ of the Expiration is a continuation upwards of the central zone of the Annunciation with the Flames and the Dove; the figure of the Archangel Gabriel has its counterpart in the figure of Saint John; and the Virgin of Joy appears above as the Virgin of Grief.

This painting of the Crucifixion is one of the great interpretations of the subject in painting and almost inevitably brings to mind two other great Crucifixions, Grünewald's of the Isenheim Altar and Giotto's of the Arena Chapel. El Greco has introduced more of those symbols embodying spiritual emotions: the clamoring angels with outstretched arms encircling the Body of Christ - strangely recalling Giotto's painting - and the remarkable figure of the angel at the foot of the Cross.

It is of the same size and shape as the Pentecost, to which it was almost certainly a pair. The place of these two paintings in the chapel is more difficult to decide. The Resurrection was almost certainly on the left and the Pentecost on the right, because of their relationship in meaning with the Nativity and the Baptism, respectively. If they were placed above these two paintings, the narrower format would correspond with the upper range of paintings. This and the Pentecost would have been the last of the paintings executed for the Colegio.

Only one other painting of the subject by El Greco is known, that for Santo Domingo el Antiguo. This painting and the Adoration of the Shepherds are higher in proportion to their width than the corresponding paintings in Santo Domingo el Antiguo.

Christ is shown in a blaze of glory, striding through the air and holding the white banner of victory over death. The soldiers who had been placed at the tomb to guard it scatter convulsively. Two of them cover their eyes, shielding themselves from the radiance, and two others raise one hand in a gesture of acknowledgement of the supernatural importance of the event. Another wearing a helmet decorated with brilliantly coloured plumes, rests his cheek on his hand - the traditional pose of melancholy - still unaware of Christ's resurrection. El Greco's skill in creating dramatically foreshortened figures is clamorously apparent in the soldier wearing a yellow cuirass sprawled in the foreground and in the adjacent soldier in green. By excluding any visual reference to the tomb or to landscape, El Greco removed the scene from the realm of history, he articulated its universal significance through the dynamism of nine figures that make up the composition and the intensity of the light and colors

. Again El Greco has created one of the greatest interpretations of the subject in art. It can, perhaps, only be compared with the great masterpiece by Piero della Francesca. Light is the important element in this image of the Risen Christ, as it was in the Adoration of the Shepherds, but of a different quality. The movement has an incomparably greater force than in the Santo Domingo painting and has nothing of the sharp explosive quality of the earlier work. The movement is not dissipated, but is contained and concentrated. The figures now are vehicles of movement and light. It is interesting to compare the treatment of the classical 'draperies' of the soldier at the base of the composition with those of the saintly warriors of the Martyrdom of Saint Maurice and his Legions.

There are, however, certain passages in this painting that suggest over painting or finishing by another hand (Jorge Manuel's?), which could point to a separate contract for this pair of paintings for the college. He was late in finishing the commission and there were difficulties in collecting moneys from the College - was the last of the series left unfinished, and completed later by his son? The Apostle second from the right is certainly a portrait of the artist, and the same portrait appears in the Marriage of the Virgin, one of his last works.

By EL GRECO

In 1603 El Greco received the commission for a new altarpiece for the Hospital de la Caridad, Illescas. The commission included the decoration of the whole chapel, including the design for the retable and the provision of sculptures as well as paintings of the Madonna of Charity, Coronation of the Virgin, Annunciation and Nativity. The contract stipulated that the altarpiece should be in place by 31 August 1604. However, the work was completed only by 4 August 1605, and a bitter and lengthy litigation started over the price which ended with compromise in March 1607.

It is difficult, and perhaps not proper, to separate his portraits of Saints from his actual portraits. In both he employs all his means of spiritual or psychological expression. The legend is that Saint Ildefonso, the first Bishop of Toledo, presented an image of the Virgin of the Mantle to a foundation of his in Illescas. The Saint is portrayed before the same image, as he wrote his dissertation on the Purity of the Virgin. The state of inspiration is brilliantly expressed. There is an infinite distinction in expression between the hand poised with the pen in this 'portrait' and the similar motif in the portrait of his son. In his depiction of St Ildefonso, El Greco anticipated a Baroque motif, that of the learned churchman. As if receiving inspiration, the saint is seated at a desk covered with an array of utensils that is unusually detailed for the artist.

There is a smaller replica of the picture in the National Gallery of Art in Washington. It belonged once to the painter Jean François Millet, and later to Edgar Degas.

Between 1607 and 1608 El Greco was involved in a protracted legal dispute with the authorities of the Hospital of Charity at Illescas concerning payment for his work, which included painting, sculpture and architecture; this and other legal disputes contributed to the economic difficulties he experienced towards the end of his life. In 1608, he received his last major commission: for the Hospital of Saint John the Baptist in Toledo.

El Greco made Toledo his home. Surviving contracts mention him as the tenant from 1585 onwards of a complex consisting of three apartments and twenty-four rooms which belonged to the Marquis de Villena. It was in these apartments, which also served as his workshop, that he passed the rest of his life, painting and studying. He lived in considerable style, sometimes employing musicians to play while he dined. It is not confirmed whether he lived with his Spanish female companion, Jerónima de Las Cuevas, whom he probably never married. She was the mother of his only son, Jorge Manuel, born in 1578, who also became a painter, assisted his father, and continued to repeat his compositions for many years after he inherited the studio. In 1604, Jorge Manuel and Alfonsa de los Morales gave birth to El Greco's grandson, Gabriel, who was baptized by Gregorio Angulo, governor of Toledo and a personal friend of the artist.

During the course of the execution of a commission for the Hospital Tavera, El Greco fell seriously ill, and a month later, on April 7, 1614, he died. A few days earlier, on March 31, he had directed that his son should have the power to make his will. Two Greeks, friends of the painter, witnessed this last will and testament (El Greco never lost touch with his Greek origins). He was buried in the Church of Santo Domingo el Antigua.

By EL GRECO

Having the previous month signed the contract for The Disrobing of Christ for the vestry of Toledo Cathedral, in August 1577 El Greco was formally engaged by Diego de Castilla, dean of Toledo Cathedral, to paint three altarpieces for the Cistercian convent of Santo Domingo el Antiguo. The two side altars were to be decorated with The Adoration of the Shepherds and The Resurrection (still in situ), while the main altar received an enormous, multi-tiered altarpiece with six canvases that had as its focus The Assumption of the Virgin (signed and dated 1577, now in the Art Institute, Chicago) and The Trinity (Prado, Madrid). The complex was among the most ambitious of El Greco's career and constituted one of his finest achievements. The missing canvases - The Assumption of the Virgin, The Trinity, and the half-length figures of Saint Benedict and Saint Bernard - have been replaced by copies, so that the character of the altarpiece can still be appreciated.

El Greco was supplied with plans of the church as well as designs for the frames of the lateral altarpieces drawn up by Juan de Herrera, Philip II's architect at the Escorial. El Greco had furnished drawings for the project. Additionally, he was to superintend the design of the frames as well as of a tabernacle and five statues to adorn the main altarpiece - two of Prophets and three of Virtues (Faith, Charity and Hope). Like the frames, these statues were carved - with significant modifications - by Juan Bautista Monegro (c. 1545-1621), who was also responsible for the cherubs holding an escutcheon with the sudarium.

This involvement with the frames of his altarpieces as well as with their sculptural adornment was to become typical of El Greco, who in Venice had learned to model figures in clay and wax to study elaborate poses.

The Santo Domingo altarpieces were a fitting debut for Toledo's greatest artistic genius, newly arrived from Italy, his mind filled with the most advanced ideas about the possibilities of art as a communicator of ideas and as a vehicle for the expression of spiritual values.

El Greco was supplied with plans of the church as well as designs for the frames of the lateral altarpieces drawn up by Juan de Herrera, Philip II's architect at the Escorial. El Greco had furnished drawings for the project and he promised to paint the specified scenes to the complete satisfaction of Don Diego and to remain in Toledo until the work was finished. Additionally, he was to superintend the design of the frames as well as of a tabernacle and five statues to adorn the main altarpiece - two of Prophets and three of Virtues (Faith, Charity and Hope). Like the frames, these statues were carved - with significant modifications - by Juan Bautista Monegro (c. 1545-1621), who was also responsible for the cherubs holding an escutcheon with the sudarium.

This involvement with the frames of his altarpieces as well as with their sculptural adornment was to become typical of El Greco, who owned the architectural treatises of Vitruvius and Serlio and in Venice had learned to model figures in clay and wax to study elaborate poses. It was by means of his carefully articulated, almost rigorously classical frames that El Greco created a neutral foil for the agitated, spiritual world his paintings conjure up. In the great Assumption of the Virgin, the Apostle closest to the picture frame turns his back to the viewer, thus closing off the steep, notional space of the painting: the viewer is a distanced spectator. By contrast, in the smaller, lateral altarpiece of The Adoration of the Shepherds, a half-length figure of Saint Jerome seems to pose a book on the edge of the frame and turns to address the viewer, serving as a link between two worlds: he is painted in a distinctly more realistic style than the figures of The Adoration, positioned deeper in space, and he thus serves as a mediator between the real and the fictive.

The Santo Domingo altarpieces were a fitting debut for Toledo's greatest artistic genius, newly arrived from Italy, his mind filled with the most advanced ideas about the possibilities of art as a communicator of ideas and as a vehicle for the expression of spiritual values.

There is a clear reminiscence of Venetian paintings of the subject, and specifically of Titian's early masterpiece in the church of the Frari in Venice, but the treatment is his own. The Virgin rises as from a chalice formed by the two unified groups on either side of the open tomb, which introduce and extend motifs developed in his Cleansing of the Temple and Healing of the Blind. A complete unity is achieved in this bipartite composition, in which the circle of Apostles, with its contained and concentrated internal movement, or emotion, is continued in the circle of angels with their easy and sympathetic movement around the rising figure of the Virgin. There is a sustained rhythm of the expressions, gestures and surface treatment within each group, and an easy and inevitable connection of one group with another. This is achieved essentially by paint, the measured relationship of the passages of color over the surface. This also explains his treatment of the draperies, which has its own logic, has no suggestion of conflict, but is also not concerned with disclosing the anatomy beneath

. When we compare the The Assumption of the Virgin with the famous painting on the same subject by Titian in the Frari Church in Venice, it becomes clear how new were the paths El Greco took in Spain. Under the influence of Michelangelo he not only found an unusually naturalistic style with monumental figures, but adopted a palette tending towards that of the Roman school. The great luminosity of the painting is striking, an illumination that, probably not coincidentally, conforms with the real light falling on it from above. No other version of the subject is known, but the painting may be regarded as the forerunner of the related composition of the Immaculate Conception, a subject more compatible with El Greco's mystical approach to the Universe.

Here the reference is to Rome, rather than to Venice, and specifically to Michelangelo, developing the motif of the Pietà. The general scheme of the composition of the Trinity, however, refers to Dürer's engraving of the same subject. The composition continues that of the Assumption below, slowing down the upward movement which finally comes to rest in the supported shoulders of Christ. Form is more in evidence here than in the Assumption, especially in the Michelangelesque motif of the naked Christ (for which the artist probably drew inspiration from Michelangelo's Pietà for Vittoria Colonna), and it is only later that he treats his figures with the same freedom as draperies. Here the suggestion of weight in the supported Dead Christ is appropriate. The stress on the dead body of Christ, together with the clamorous mannerist colors and the rather loose composition of the figures, produces a feverish pathos.

El Greco was not to repeat this subject.

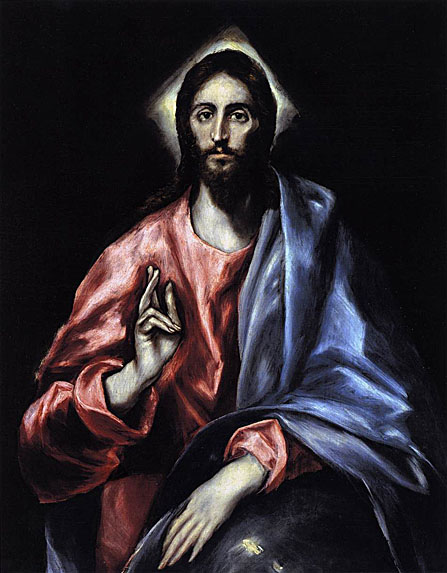

In the painting, El Greco created a hauntingly disembodied likeness, with Christ staring at the viewer in the fashion of a Byzantine icon.

The presence of Saint Ildefonso, the patron Saint of Toledo, was stipulated in the documents. Diego de Castilla, the Dean of Toledo Cathedral, is probably represented in this figure, which certainly is a portrait. The figure assists in setting an ideal plane for the enacting of the mystic event. El Greco has eliminated the intrusion of an incongruous space. The ground running parallel with the plane of the action produces no conflict. The rhythm of the passages of colour and light over the surface helps to hold together the composition, with its dramatic split revealing the figure of the Risen Christ. What suggestions remain of an ordinary conception of space, of corporeality and of a schematic quality of composition, disappear in his final version of the subject (painted in 1596-1600, now in the Prado, Madrid).

By EL GRECO

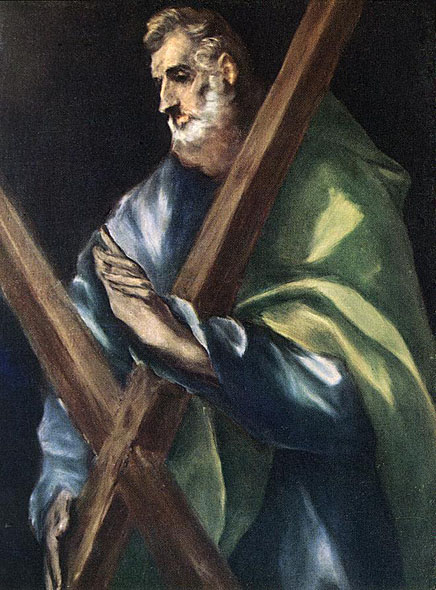

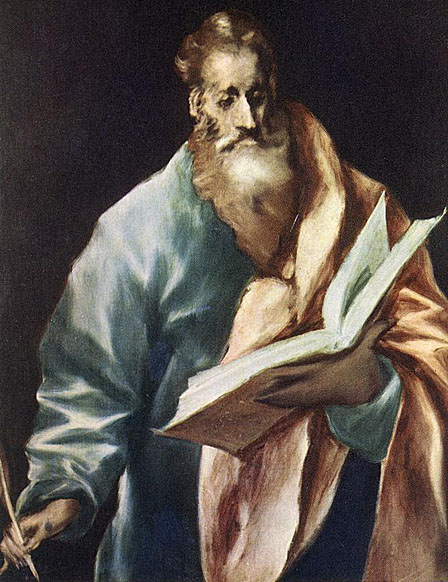

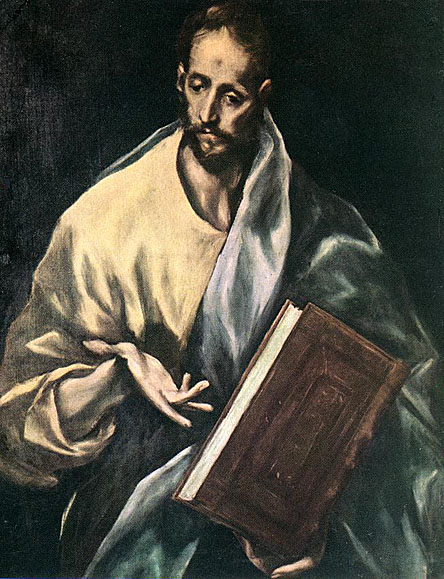

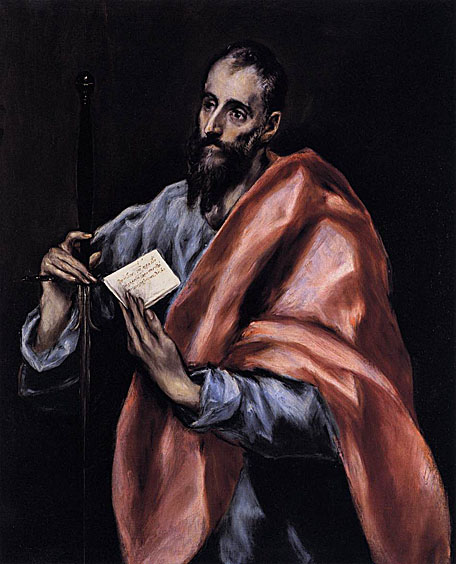

El Greco painted several series in which Christ and the Apostles appear as separate images (Apostolados). The artist accepted the assistance of collaborators in some of these he painted in the final years of his life, but it is no less certain that he preserved until the very end that absolute mastery over his art so conspicuous in the superb series in the Museo de El Greco in Toledo. Other (incomplete) series are in the Toledo Cathedral, in Oviedo and in the Prado.

The group of thirteen pictures in the Museo de El Greco was conceived as a whole, with Christ looking directly at the viewer, six of the Apostles turning to the right and six to the left. The expressive, fragmentary brushwork has led some to suppose that the series was left unfinished at El Greco's death.

Literally, the apostles (from the Greek apostolos, envoy, messenger) are the twelve disciples of Christ whom he sent out to evangelise the nations. The name was also given at a later date to the small number of saints who continued the task of evangelisation begun by the first "apostles", and who are also considered as emissaries of Christ. Following St Paul, the apostle of the Gentiles, come, among many others, St Martin, the apostle of the Gauls; St Boniface, apostle of Frisia and Germany; and SS. Cyril and Methodius, apostles of the Slavs. The original twelve formed a group which served to witness that the Jesus they knew was indeed the Messiah.

In the lists given in the New Testament, the earliest disciples - Peter (Simon Peter), Andrew, James the Greater (or Great) and John - are always named first. A second group of four follows: Philip, Bartholomew, Matthew and Thomas. Finally appear James the Less, Jude (or Thaddaeus), Simon the Canaanite and Judas Iscariot. Peter always occupies the first place and Judas the last; the latter was replaced by Matthias after the betrayal. However, in all of El Greco's Apostolados, Apostle Paul is chosen to replace Judas. Although not one of the original twelve whom Christ chose to be his closest followers, Paul became the 'Apostle of the Gentiles' following his dramatic conversion on the road to Damascus.

Popular piety had all the apostles die for the true faith and their legends include a number of different methods of martyrdom. Like Christ, five were crucified: Peter and Philip upside down and Andrew on a cross saltire.

Andrew is the patron saint of Greece and Scotland. Among differing accounts of his relics, one tells of their being carried to the town of St Andrews in Scotland in the 4th century.

He is usually portrayed as dark-haired, bearded and of middle age. His invariable attribute is the knife with which he was flayed. Not uncommonly the flayed skin hangs over his arm, or is held in his hand, as in the Last Judgement in the Sistine Chapel (said to be a self-portrait of Michelangelo). His inscription, from the Apostles' Creed, is 'Credo in Spiritum Sanctum'. Typical narrative themes from Renaissance art show him preaching, exorcizing demons, baptizing, and being hauled before the authorities for refusing to worship idols. The most usual scene is the rather gruesome flaying. Artists sometimes follow the Hellenistic sculpture from Pergamum of the flaying of Marsyas.

Apostle St James the Less in Art

James holds a fuller's staff, which may be short- or long-handled, having a clubbed head; or it is shaped like a flat bat. It was once used by the fuller in the process of finishing cloth, to compact the material by beating it. From the early 14th century, especially in German art, he may instead hold a hatter's bow, which was used in the manufacture of felt for hats and by wool-workers to clean wool. It may be shown without a bow-string.

James was the patron saint of hat-makers, mercers and other similar medieval guilds. As bishop of Jerusalem he may wear episcopal robes, with mitre and crozier.

El Greco's painting does not follow thetraditional representations of the Apostle.

_1610_14_Apostolados.jpg)

In this painting El Greco shows St Paul with a sword, the instrument of his martyrdom, and a letter inscribed in cursive Greek "To Titus, ordained first bishop of the church of the Cretans'.

St Paul appears a great number of times in El Greco's oeuvre and he is depicted with remarkable consistency. The saint is always shown slightly balding, with dark hair and beard, wearing a red mantle thrown over a blue or green tunic.

By EL GRECO

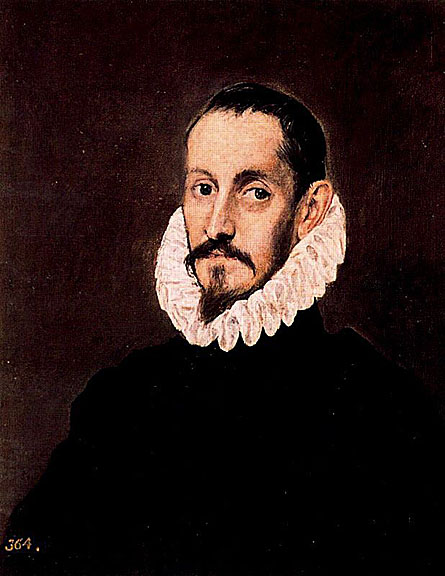

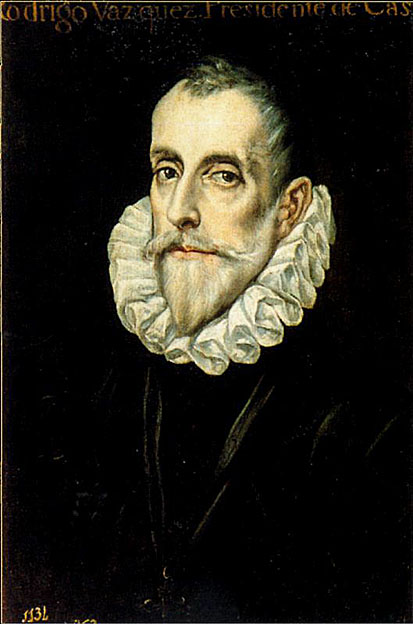

In his later portraits El Greco increasingly reduces the role of the body of his sitters, omitting all the props and attributes of their rank, and he attempts to reveal the whole being of them. He painted around 1600 the Portrait of a Man (an assumed self-portrait), a fine and particularly compelling portrait, the moving portrait of his friend Antonio de Covarrubias, and the awesome portrait of the Grand Inquisitor, a celebrated picture which has become synonymous not only with El Greco but with Spain and the Spanish Inquisition.

Two signed and four unsigned versions are known, the best being that in the Frick Collection, New York.

This celebrated picture - a landmark in the history of European portraiture - has become synonymous not only with El Greco but with Spain and the Spanish Inquisition.

The painting has a pendant, also in the Museo de El Greco, showing Diego's younger brother Antonio - an autograph copy of El Greco's painting in the Louvre.

Source: Web Gallery of Art

Source: Art Renewal Center

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.