Wassily Kandinsky

Russian Painter

Abstract Impressionism

1866 - 1944

Wassily Kandinsky: ca 1913

Wassily Wassilyevich Kandinsky was a Russian painter and art theorist. He is credited with painting the first modern abstract works.

Born in Moscow, Kandinsky spent his childhood in Odessa. He enrolled at the University of Moscow and chose to study law and economics. Quite successful in his profession-he was offered a professorship (chair of Roman Law) at the University of Dorpat - he started painting studies (life-drawing, sketching and anatomy) at the age of 30.

In 1896, he settled in Munich and studied first in the private school of Anton Azbe and then at the Academy of Fine Arts, Munich. He went back to Moscow in 1914, after World War I started. He was unsympathetic to the official theories on art in Moscow and returned to Germany in 1921. There, he taught at the Bauhaus School of Art and Architecture from 1922 until the Nazis closed it in 1933. He then moved to France where he lived the rest of his life and became a French citizen in 1939. He died at Neuilly-sur-Seine in 1944.

His great-grandson, Anton S. Kandinsky, is also an artist, based in New York and working in a style called 'Gemism'.

Kandinsky's creation of purely abstract work followed a long period of development and maturation of intense theoretical thought based on his personal artistic experiences. He called this devotion to inner beauty, fervor of spirit, and deep spiritual desire inner necessity, which was a central aspect of his art.

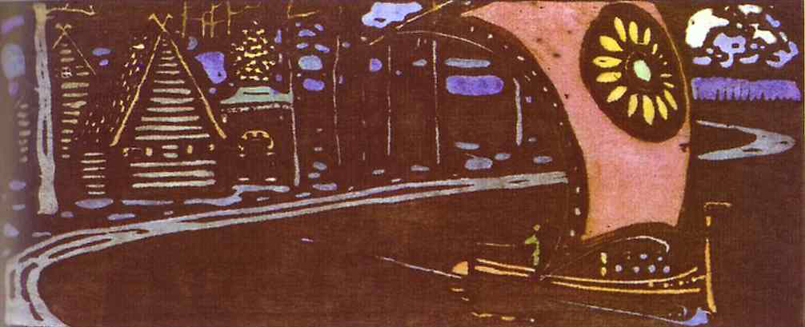

Kandinsky learned from a variety of sources living in Moscow. Later in his life, he would recall being fascinated and unusually stimulated by color as a child. The fascination with color symbolism and psychology continued as he grew. In 1889 he was part of an ethnographic research group that travelled to the Vologda region north of Moscow. In Looks on the Past he relates that the houses and churches were decorated with such shimmering colors that, upon entering them, he had the impression that he was moving into a painting. The experience and his study of the folk art in the region, in particular the use of bright colors on a dark background, was reflected in much his early work. A few years later, he first related the act of painting to creating music in the manner for which he would later become noted and wrote, "Color is the keyboard, the eyes are the harmonies, the soul is the piano with many strings. The artist is the hand that plays, touching one key or another, to cause vibrations in the soul."

It was not until 1896, at the age of 30, that Kandinsky gave up a promising career teaching law and economics to enroll in art school in Munich. He was not immediately granted admission in Munich and began learning art on his own. Also in 1896, prior to leaving Moscow, he saw an exhibit of paintings by Monet and was particularly taken with the famous impressionistic Haystacks which, to him, had a powerful sense of color almost independent of the objects themselves. Later he would write about this experience:

"That it was a haystack the catalogue informed me. I could not recognize it. This non-recognition was painful to me. I considered that the painter had no right to paint indistinctly. I dully felt that the object of the painting was missing. And I noticed with surprise and confusion that the picture not only gripped me, but impressed itself ineradicably on my memory. Painting took on a fairy-tale power and splendor."

He was similarly influenced during this period by Richard Wagner's Lohengrin which, he felt, pushed the limits of music and melody beyond standard lyricism.

Kandinsky was also spiritually influenced by H. P. Blavatsky (1831-1891), the most important exponent of Theosophy in modern times. Theosophical theory postulates that creation is a geometrical progression, beginning with a single point. The creative aspect of the forms is expressed by the descending series of circles, triangles, and squares. Kandinsky's book Concerning the Spiritual In Art (1910) and Point and Line to Plane (1926) echoed this basic Theosophical tenet.

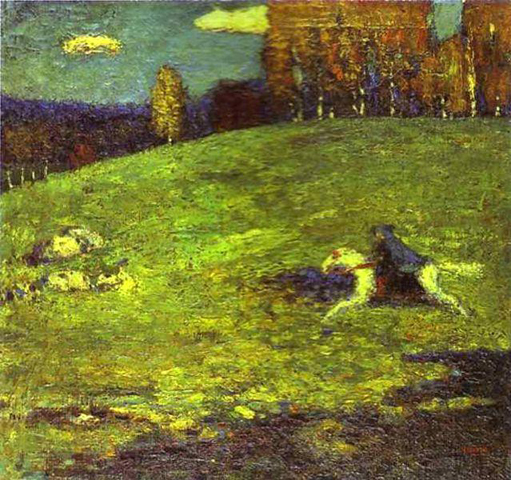

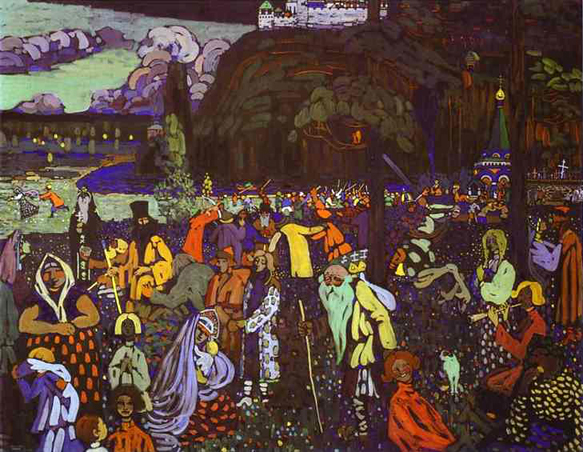

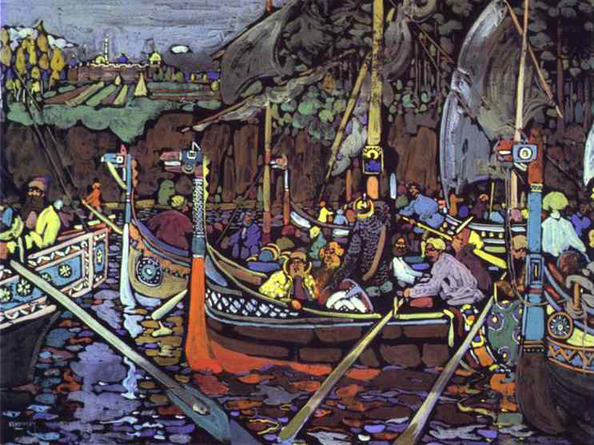

Art school, typically considered difficult to get through, was easier for Kandinsky because he was older and more settled than the other students. It was during this time that he began to emerge as a true art theorist in addition to being a painter. The number of existing paintings increased at the beginning of the 20th century and much remains of the many landscapes and towns that he painted, using broad swathes of color but recognizable forms. For the most part, however, Kandinsky's paintings did not emphasize any human figures. An exception is Sunday, Old Russia (1904) where Kandinsky recreates a highly colorful (and fanciful) view of peasants and nobles before the walls of a town. Riding Couple (1907) depicts a man on horseback, holding a woman with tenderness and care as they ride past a Russian town with luminous walls across a river. Yet the horse is muted, while the leaves in the trees, the town, and the reflections in the river glisten with spots of color and brightness. The work shows the influence of pointillism in the way the depth of field is collapsed into a flat luminescent surface. Fauvism is also apparent in these early works. Colors are used to express the artist's experience of subject matter, not to describe objective nature. Perhaps the most important of Kandinsky's paintings from the first decade of the 1900's was The Blue Rider (1903), which shows a small cloaked figure on a speeding horse rushing through a rocky meadow. The rider's cloak is a medium blue, and the shadow cast is a darker blue. In the foreground are more amorphous blue shadows, presumably the counterparts of the fall trees in the background. The Blue Rider in the painting is prominent, but not clearly defined, and the horse has an unnatural gait (which Kandinsky must have known). Indeed, some believe that a second figure, a child perhaps, is being held by the rider, though this could just as easily be another shadow from a solitary rider. This type of intentional disjunction, allowing viewers to participate in the creation of the artwork, would become an increasingly conscious technique used by Kandinsky in subsequent years, culminating in the (often nominally) abstract works of the 1911-1914 period. In The Blue Rider Kandinsky shows the rider more as a series of colors than of specific details. In and of itself, The Blue Rider is not exceptional in that regard when compared to contemporary painters, but it does show the direction that Kandinsky would take only a few years later.

Sunday, Old Russia: 1904

Couple Riding: 1906/07

Blue Rider: 1903

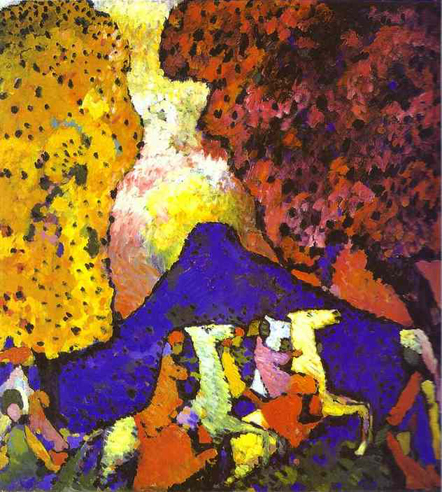

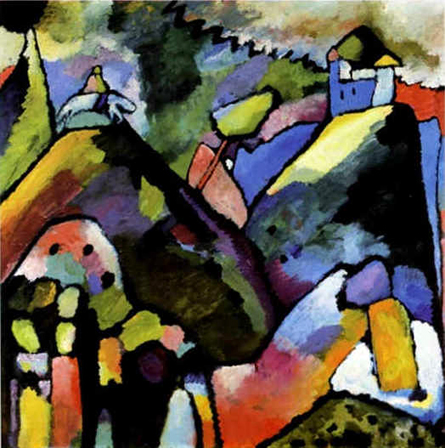

From 1906 to 1908 Kandinsky spent a great deal of time travelling across Europe, (he was an associate of the Blue Rose symbolist group of Moscow) until he settled in the small Bavarian town of Murnau. The Blue Mountain (1908-1909) was painted at this time and shows more of his trend towards pure abstraction. A mountain of blue is flanked by two broad trees, one yellow and one red. A procession of some sort with three riders and several others crosses at the bottom. The faces, clothing, and saddles of the riders are each a single color, and neither they nor the walking figures display any real detail. The flat planes and the contours also are indicative of some influences by the Fauvists. The broad use of color in The Blue Mountain, illustrates Kandinsky's move towards an art in which color is presented independently of form, and which each color is given equal attention. The composition has also become more planar, as it seems that the painting itself is divided into four sections- the sky, the red tree, the yellow tree, and the blue mountain containing the three riders.

The Blue Mountain: 1908 - 09

The paintings of this period are composed of large and very expressive colored masses evaluated independently from forms and lines which serve no longer to delimit them but are superimposed and overlap in a very free way to form paintings of an extraordinary force.

The influence of music has been very important on the birth of abstract art, as it is abstract by nature-it does not try to represent the exterior world but rather to express in an immediate way the inner feelings of the human soul. Kandinsky sometimes used musical terms to designate his works; he called many of his most spontaneous paintings "improvisations", while he entitled more elaborated works "compositions".

In addition to painting Kandinsky developed his voice as an art theorist. In fact, Kandinsky's influence on the History of Western Art stems perhaps more from his theoretical works than from his paintings. He helped to found the Neue Künstlervereinigung München (New Artists' Association) and became its president in 1909. The group was unable to integrate the more radical approach of those like Kandinsky with more conventional ideas of art and the group dissolved in late 1911. Kandinsky then moved to form a new group The Blue Rider (Der Blaue Reiter) with like minded artists such as August Macke and Franz Marc. The group released an almanac, called The Blue Rider Almanac, and held two exhibits. More of each were planned, but the outbreak of World War I in 1914 ended these plans and sent Kandinsky home to Russia via Switzerland and Sweden.

Kandinsky's writing in The Blue Rider Almanac and the treatise On the Spiritual In Art, which was released at almost the same time, served as both a defense and promotion of abstract art, as well as an appraisal that all forms of art were equally capable of reaching a level of spirituality. He believed that color could be used in a painting as something autonomous and apart from a visual description of an object or other form.

"The sun melts all of Moscow down to a single spot that, like a mad tuba, starts all of the heart and all of the soul vibrating. But no, this uniformity of red is not the most beautiful hour. It is only the final chord of a symphony that takes every color to the zenith of life that, like the fortissimo of a great orchestra, is both compelled and allowed by Moscow to ring out."

~ Wassily Kandinsky

Through the years 1918 to 1921, Kandinsky dealt with the cultural development politics of Russia and collaborated in the domains of art pedagogy and museum reforms. He devoted his time to artistic teaching with a program based on form and color analysis, as well as participating in the organization of the Institute of Artistic Culture in Moscow. He painted little during this period. In 1916 he met Nina Andreievskaya, who in the following year became his wife. His spiritual, expressionistic view of art was ultimately rejected by the more radical members of the Institute as too individualistic and bourgeois. In 1921 Kandinsky received the mission to go to Germany to attend the Bauhaus of Weimar, on the invitation of its founder, the architect Walter Gropius.

The Bauhaus was an innovative architecture and art school whose objectives included the merging of plastic arts with applied arts, reflected in its teaching methods based on the theoretical and practical application of the plastic arts synthesis. Kandinsky taught the basic design class for beginners and the course on advanced theory, and also conducted painting classes and a workshop where he completed his color theory with new elements of form psychology. The development of his works on forms study, particularly on point and different forms of lines, lead to the publication of his second major theoretical book Point and Line to Plane in 1926.

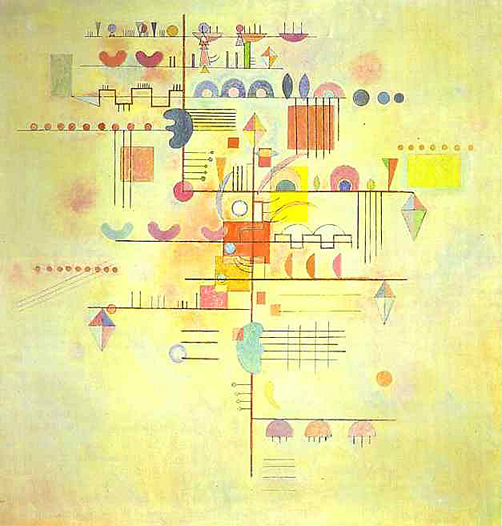

Geometrical elements took on increasing importance in his teaching as well as in his painting, particularly circle, half-circle, the angle, straight lines and curves. This period was a period of intense production. The freedom of which is characterized in each of his works by the treatment of planes rich in colors and magnificent gradations as in the painting Yellow - red - blue (1925), where Kandinsky shows his distance from constructivism and suprematism movements whose influence was increasing at this time.

Yellow-Red-Blue: 1925

The large two meter width painting that is Yellow - red - blue (1925) consists of a number of main forms: a vertical yellow rectangle, a slightly inclined red cross and a large dark blue circle, while a multitude of straight black or sinuous lines, arcs of circles, monochromatic circles and scattering of colored checkerboards contribute to its delicate complexity. This simple visual identification of forms and of the main colored masses present on the canvas only corresponds to a first approach of the inner reality of the work whose right appreciation necessitates a much deeper observation-not only of forms and colors involved in the painting, but also of their relation, their absolute position and their relative disposition on the canvas, of their whole and reciprocal harmony.

Kandinsky was one of Die Blaue Vier (Blue Four), with Klee, Feininger and von Jawlensky formed in 1923. They lectured and exhibited together in the USA in 1924.

In front of the hostility of the political parties of the right, the Bauhaus left Weimar and settled in Dessau from 1925. Following a fierce slander campaign from the Nazis, the Bauhaus closed at Dessau in 1932. The school pursued its activities in Berlin until its dissolution in July 1933. Kandinsky then left Germany and settled in Paris.

In Paris he was quite isolated since abstract painting-particularly geometric abstract painting-was not recognized, the artistic fashions being mainly Impressionism and Cubism. Kandinsky lived in a small apartment and created his work in a studio constructed in the living room. Biomorphic forms with supple and non-geometric outlines appear in his paintings; forms which suggest externally microscopic organisms but which always express the artist's inner life. He used original color compositions which evoke Slavonic popular art and which are similar to precious watermark works. He also occasionally mixed sand with paint to give a granular texture to his paintings.

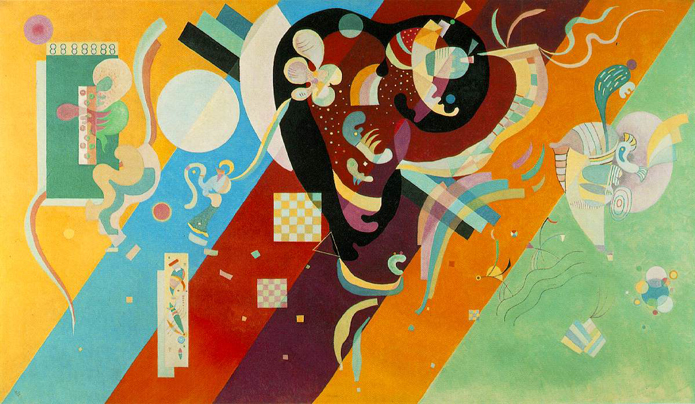

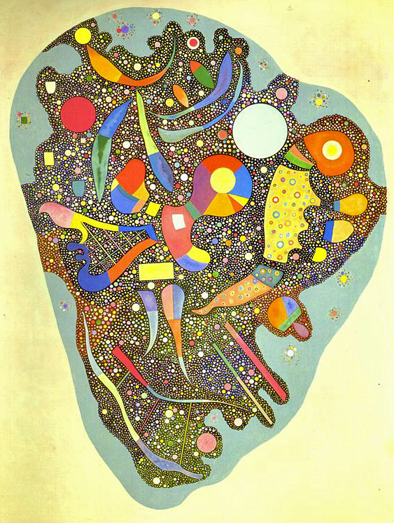

This period corresponds, in fact, to a vast synthesis of his previous work, of which he used all elements, even enriching them. In 1936 and 1939 he painted his two last major compositions; canvases particularly elaborate and slowly ripped that he hadn't produced for many years. Composition IX is a painting with highly contrasted powerful diagonals and whose central form give the impression of a human embryo in the womb. The small squares of colors and the colored bands seem to stand out against the black background of Composition X, as stars' fragments or filaments, while enigmatic hieroglyphs with pastel tones cover the large maroon mass, which seems to float in the upper left corner of the canvas.

Composition IX: 1936

It was another ten years before Kandinsky completed another canvas that he would call a Composition. Composition IX reflects Kandinsky's exposure in Paris to Surrealist imagery. Although he denied any Surrealist influence in his work, the biomorphic shapes distinctly recall the pictorial language of Miro in particular. There is only one preparatory drawing for Composition IX and none for Composition X. According to Nina Kandinsky, the artist at this stage of his development was able to visualize a painting entirely in his head and then translate it directly to the canvas. This explains the paucity of studies for the late compositions. Composition IX is possibly the least impressive of the series. The wide diagonal colors serve as a solid background for the biomorphic and geometrical shapes that seem to float in front of it. There is an almost dream-like quality to the rhythm and unfurling of the forms. In the final analysis, however, Composition IX has a tangible decorative feel to it that makes it pale in comparison to the emotional intensity of the earlier compositions.

Quoted From: Kandinsky: Compositions

Composition X: 1939

Five years before his death in 1944, Kandinsky completed the final work in the series. The outstanding characteristic of Composition X is obviously the stark, black ground. The colors and forms appear particularly sharp against the black background. The brilliance of the colored shapes brings to mind the cutouts done by Matisse over a decade later. The movement of the forms is distinctly upward and outward from both sides of a central axis running through the book-like form near the top of the canvas. This movement enhances the evocation of hot-air balloon forms rising into an infinite space. The round form between the book shape and the brown balloon shape has a lunar feel to it that even conveys a feeling of literal "outer space". Kandinsky had always expressed a strong dislike for the color black and it is significant that he chose it as the dominating color of his last major artistic statement.

Quoted From: Kandinsky: Compositions

In Kandinsky's work, some characteristics are obvious while certain touches are more discrete and veiled; that is to say they reveal themselves only progressively to those who make the effort to deepen their connection with his work. He intended his forms, which he subtly harmonized and placed, to resonate with the observer's own soul.

Writing that "music is the ultimate teacher", Kandinsky embarked upon the first seven of his ten Compositions. The first three survive only in black-and-white photographs taken by fellow artist and friend, Gabriele Münter. While studies, sketches, and improvisations exist (particularly of Composition II), a Nazi raid on the Bauhaus in the 1930's resulted in the confiscation of Kandinsky's first three Compositions. They were displayed in the State-sponsored exhibit "Degenerate Art" then destroyed along with works by Paul Klee, Franz Marc and other modern artists.

Influenced by Theosophy and the perception of a coming New Age, a common theme among Kandinsky's first seven Compositions is the Apocalypse, or the end of the world as we know it. Writing of the "artist as prophet" in his book, Concerning the Spiritual In Art, Kandinsky created paintings in the years immediately preceding World War I showing a coming cataclysm which would alter individual and social reality. Raised an Orthodox Christian, Kandinsky drew upon the Jewish and Christian stories of Noah's Ark, Jonah and the whale, Christ's Anastasis and Resurrection, the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse in the Revelation, various Russian folk tales, and the common mythological experiences of death and rebirth. Never attempting to picture any one of these stories as a narrative, he used their veiled imagery as symbols of the archetypes of death / rebirth and destruction / creation he felt were imminent to the pre-World War I world.

As he stated in Concerning the Spiritual In Art, Kandinsky felt that an authentic artist creating art from "an internal necessity" inhabits the tip of an upwards moving triangle. This progressing triangle is penetrating and proceeding into tomorrow. Accordingly, what was odd or inconceivable yesterday is commonplace today; what is avant garde today (and understood only by the few) is standard tomorrow. The modern artist/prophet stands lonely at the tip of this triangle making new discoveries and ushering in tomorrow's reality. Kandinsky had become aware of recent developments in sciences, as well as the advances of modern artists who had contributed to radically new ways of seeing and experiencing the world.

Composition IV and subsequent paintings are primarily concerned with evoking a spiritual resonance in viewer and artist. As in his painting of the apocalypse by water (Composition VI), Kandinsky puts the viewer in the situation of experiencing these epic myths by translating them into contemporary terms along with requisite senses of desperation, flurry, urgency, and confusion. This spiritual communion of viewer-painting-artist/prophet is ineffable but may be described to the limits of words and images.

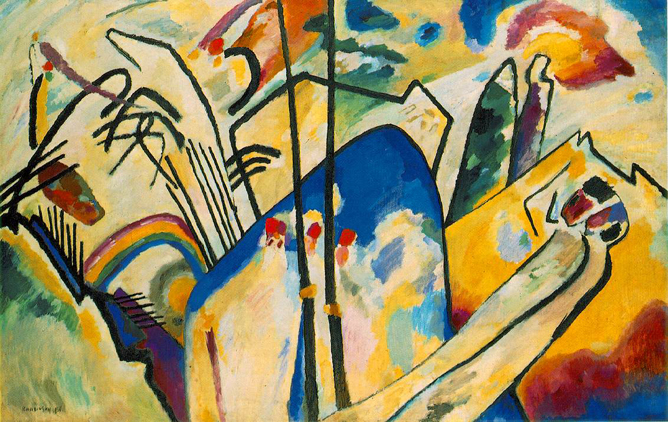

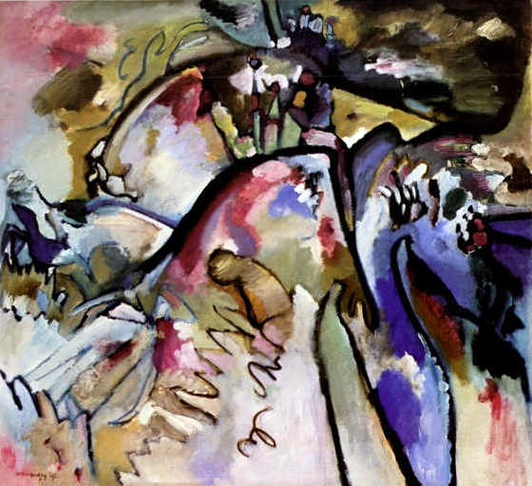

Composition IV: 1911

This feeling provides a contrast that enhances the impact of Composition IV, a maelstrom of swirling colors and soaring lines. The painting is divided abruptly in the center by two thick, black vertical lines. On the left, a violent motion is expressed through the profusion of sharp, jagged and entangled lines. On the right, all is calm, with sweeping forms and color harmonies. We have followed Kandinsky's intention that our initial reaction should result from the emotional impact of the pictorial forms and colors. However, upon closer inspection the apparent abstraction of this work proves illusory. The dividing lines are actually two lances held by red-hatted Cossacks. Next to them, a third, white-bearded Cossack leans on his violet sword. They stand before a blue mountain crowned by a castle. In the lower left, two boats are depicted. Above them, two mounted Cossacks are joined in battle, brandishing violet sabers. On the lower right, two lovers recline, while above them two robed figures observe from the hillside. Kandinsky has reduced representation to pictographic signs in order to obtain the flexibility to express a higher, more cosmic vision. The deciphering of these signs is the key to understanding the theme of the work. An awareness of Kandinsky's philosophy leads to a reading of Composition IV as expressing the apocalyptic battle that will end in eternal peace. Composition IV works on multiple levels: initially, the colors and forms exercise an emotional impact over the viewer, without need to consider the representational aspects. Then, the decoding of the representational signs involves the viewer on an intellectual level. I find that I can no longer view Composition IV without automatically translating the imagery to representational forms. Yet this solving of the work's mysteries does not draw the life from it; rather, the original emotional impact is strengthened in a new way.

Quoted From: Kandinsky: Compositions

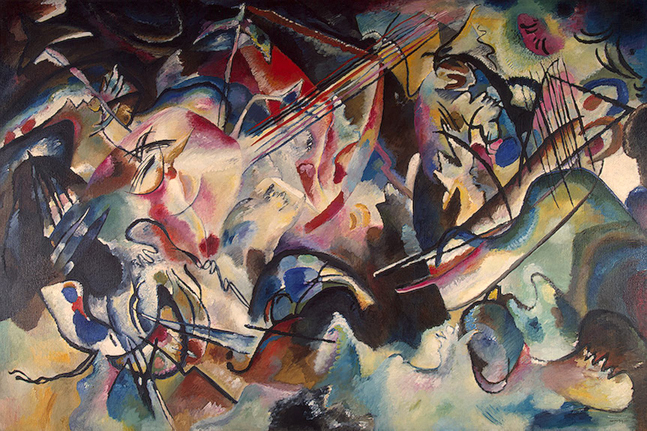

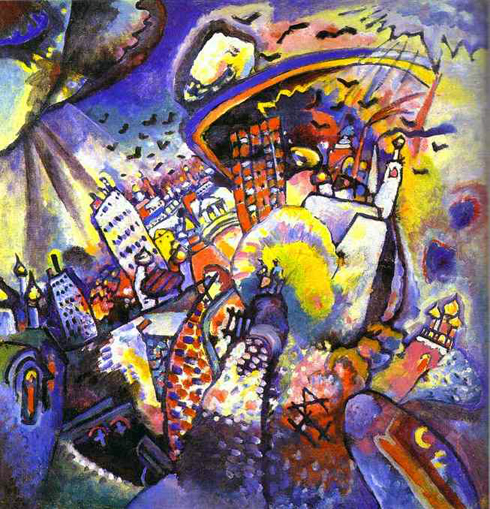

Composition VI: 1913

Standing below the six by ten foot expanse of Composition VI, the viewer cannot help but brace himself against the impending crash of a tidal wave of colliding forms and colors. And, in fact, the theme of this work is The Deluge. Kandinsky defined three centers to this Composition, which are discerned sequentially by the viewer. Initially, the eye is drawn to the pink and white vortex in the left center. The multiple lines representing torrential rain carry the focus to the right section, where a darker center of discordant forms and stronger rain lines adds to the tumult. From this second center, the eye slides to the lower center, where a blue form outlined in black cowers below the torrents of rain and crashing waves. In this work, Kandinsky has pushed further beyond representation to the very limits of abstraction.

Quoted From: Kandinsky: Compositions

As the Der Blaue Reiter Almanac essays and theorizing with composer Arnold Schoenberg indicate, Kandinsky also expressed this communion between artist and viewer as being simultaneously available to the various sense faculties as well as to the intellect (synesthesia). Hearing tones and chords as he painted, Kandinsky theorized that, for examples, yellow is the color of middle-C on a piano, a brassy trumpet blast; black is the color of closure and the ends of things; and that combinations and associations of colors produce vibrational frequencies akin to chords played on a piano. Kandinsky also developed an intricate theory of geometric figures and their relationships, claiming, for example, that the circle is the most peaceful shape and represents the human soul. These theories are set forth in Point and Line to Plane.

During the months of studies Kandinsky made in preparation for Composition IV he became exhausted while working on a painting and went for a walk. In the meantime, Gabriele Münter tidied his studio and inadvertently turned his canvas on its side. Upon returning and seeing the canvas-yet not identifying it-Kandinsky fell to his knees and wept, saying it was the most beautiful painting he had seen. He had been liberated from attachment to the object. As when he first viewed Monet's Haystacks, the experience would change his life and the history of Western art.

In another event with Münter during the Bavarian Abstract Expressionist years, Kandinsky was working on his Composition VI. From nearly six months of study and preparation, he had intended the work to evoke a flood, baptism, destruction, and rebirth simultaneously. After outlining the work on a mural-sized wood panel, he became blocked and could not go on. Münter told him that he was trapped in his intellect and not reaching the true subject of the picture. She suggested he simply repeat the word "uberflut" ("deluge" or "flood") and focus on its sound rather than its meaning. Repeating this word like a mantra, Kandinsky painted and completed the monumental work in only a three-day span.

From: Wassily Kandinsky - Wikipedia

From: Wassily Kandinsky Online

Selected Works of Wassily Kandinsky

They are in no specific chronological or thematic order.

All Saints I: 1911

Arabs I Cemetry: 1909

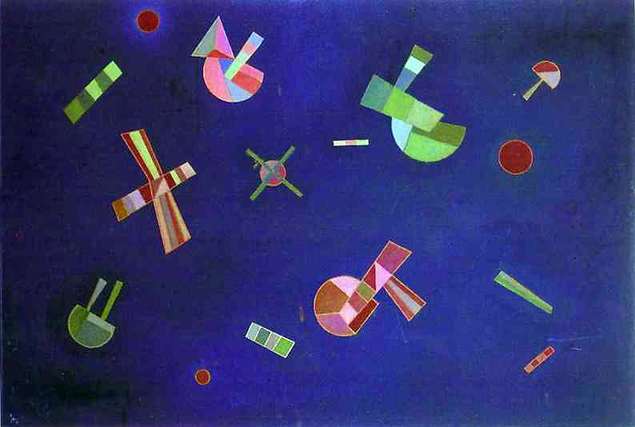

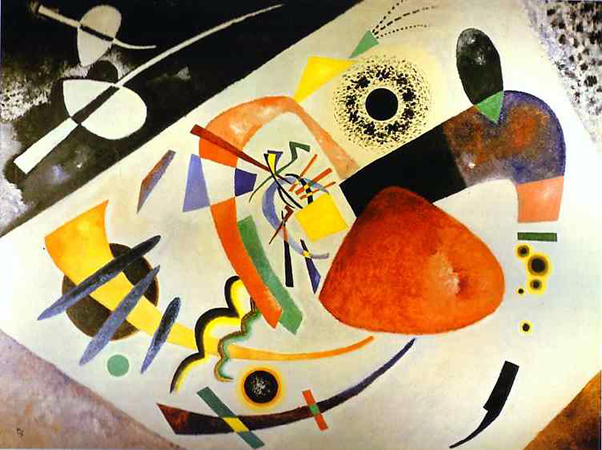

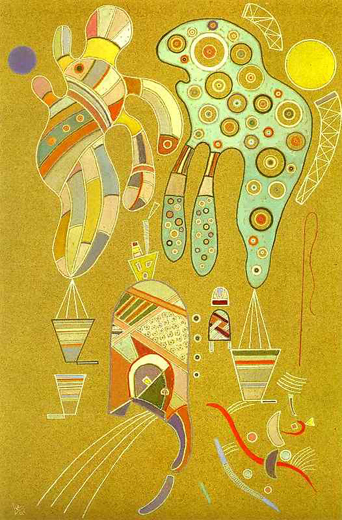

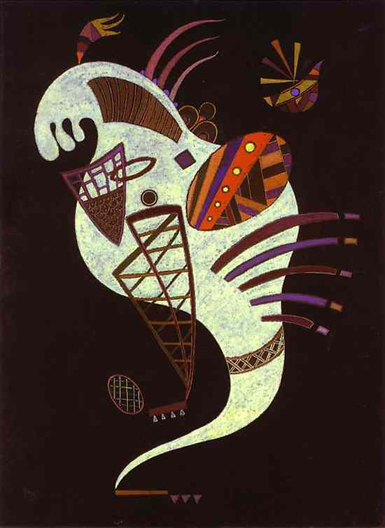

Around the Circle: 1940

Beach Baskets in Holland: 1904

Black Spot I: 1912

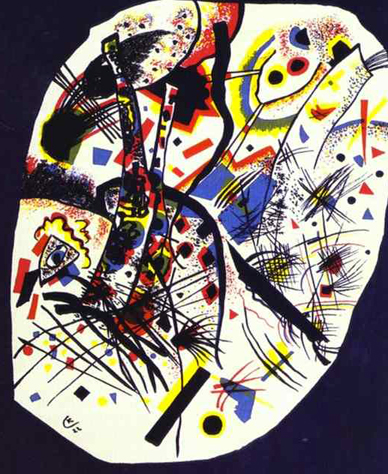

Black Strokes I: 1913

Boat Trip: 1910

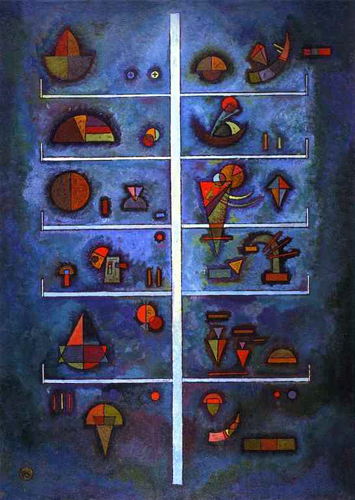

Capricious: 1930

Cemetery and Vicarage in Kochel: 1909

Church in Murnau: 1910

Colorful Ensemble: 1938

Colorful Life: 1907

Complex-Simple: 1939

Kandinsky: Compositions

A Review by Mark Harden

Kandinsky viewed the compositions as major statements of his artistic ideas. They share several characteristics that express this monumentality: the impressively large format, the conscious, deliberate planning of the composition, and the transcendence of representation by increasingly abstract imagery. Just as symphonies define milestones in the career of a composer, Kandinsky's compositions represented the culmination of his artistic vision at a given moment in his career.

Regrettably, the first three compositions were destroyed during World War II. They are represented in the exhibition by full-scale, black-and-white photographic reproductions. One of the strengths of the exhibition is the assembly of preliminary studies for most of the works. These were done in oil, watercolor, ink and pencil. These help convey a sense of the three lost compositions, but cannot hope to replace the actual canvasses. The viewer is left with a profound feeling of loss for the destroyed works.

Quoted From: Kandinsky: Compositions

(The text may deem a little disjointed since Compositions IX, X, IV, and VI were mentioned in the first section of this page.)

~ Senex

Composition V: 1911

Composition Later in 1911, Kandinsky produced Composition V, a much more abstract work. Here, the theme is the Resurrection of the Dead. The iconography is much more difficult to discern. Comparison must be made to more representational works that treat this theme done by Kandinsky around the same time. Reference to these more literal depictions of the motifs allow us to perceive their abstracted forms within Composition V. Several angels blowing their trumpets are included in the upper portion of the canvas. The strong black line crossing from right to left can be felt as a representation of the blowing of the trumpets. Above this line, the towers of a walled-in city are visible. Below the line, the thin application of paint produces a luminescence that affects our perception of space in that portion of the canvas. The luminescence conveys a sense of infinity through the lack of volume and the absence of perspectival illusion. Out of this void, the viewer can sense the rising of the dead.

Quoted From: Kandinsky: Compositions

Composition VII: 1913

Composition VII is the pinnacle of Kandinsky's pre-World War One artistic achievement. The creation of this work involved over thirty preparatory drawings, watercolors and oil studies. Each of these is included in the exhibition, documenting the deliberate creative process used by Kandinsky in his compositions. Amazingly, once he had completed the preparatory work, Kandinsky executed the actual painting of Composition VII in less than four days. The exhibition includes a series of four photographs taken between November 25 and 28, 1913, offering a fascinating record of Kandinsky's artistic procedure. Through all of the preparatory works and in the final painting itself, the central motif (an oval form intersected by an irregular rectangle) is maintained. This oval seems almost the eye of a compositional hurricane, surrounded by swirling masses of color and form. In Composition VII's final form, Kandinsky has obliterated almost all pictorial representation. Art scholars, through Kandinsky's writings and study of the less abstract preparatory works, have determined that Composition VII combines the themes of The Resurrection, The Last Judgment, The Deluge and The Garden of Love in an operatic outburst of pure painting.

Quoted From: Kandinsky: Compositions

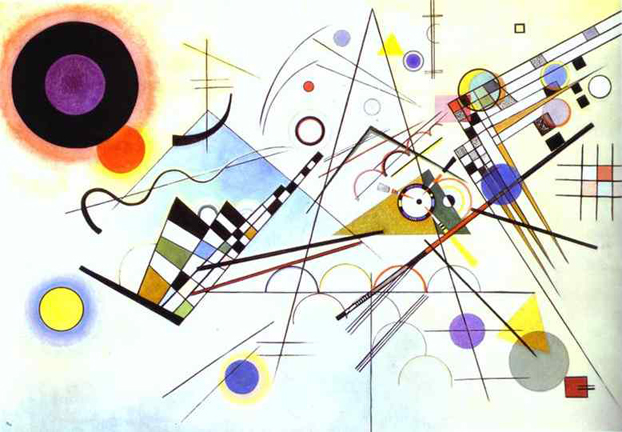

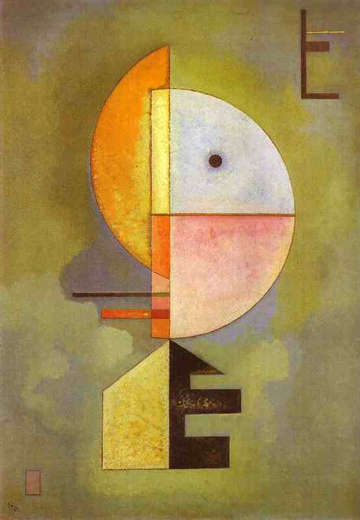

Composition VIII: 1923

The viewer receives quite a shock in moving from the apocalyptic emotion of Composition VII to the geometrical rhythm of Composition VIII. Painted ten years later in 1923, Composition VIII reflects the influence of Suprematism and Constructivism absorbed by Kandinsky while in Russia prior to his return to Germany to teach at the Bauhaus. Here, Kandinsky has moved from color to form as the dominating compositional element. Contrasting forms now provide the dynamic balance of the work; the large circle in the upper left plays against the network of precise lines in the right portion of the canvas. Note also how Kandinsky uses different colors within the forms to energize their geometry: a yellow circle with blue halo versus blue circle with yellow halo; a right angle filled with blue and an acute angle colored pink. The background also works to enhance the dynamism of the composition. The design does not appear as a geometrical exercise on a flat plane, but seems to be taking place in an undefined space. The layered background colors - light blue at bottom, light yellow at top and white in the middle - define this depth. The forms tend to recede and advance within this depth, creating a dynamic, push-pull effect.

Quoted From: Kandinsky: Compositions

Selected Works of Wassily Kandinsky - Continued

Contrasting Sounds: 1924

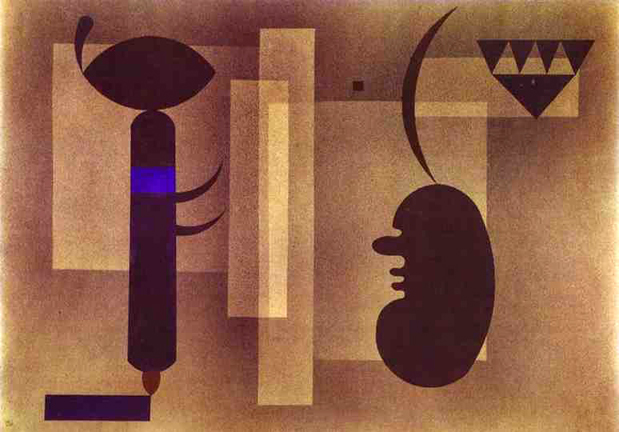

Decisive Pink: 1932

Dominant Curve: 1936

Draft for Mural in the Unjuried Art Show, Wall B: 1922

Dreamy Improvisation: 1913

Farewell: 1903

Fixed Flight: 1932

Flood Improvisation: 1913

Fugue: 1914

Gentle Ascent: 1934

Gloomy Situation: 1933

Gorge Improvisation: 1914

Grungasse in Murnau: 1909

Impression III (Concert): 1911

_1911.jpg)

Improvisation 6 (African): 1909

_1909.jpg)

Improvisation 7: 1910

Improvisation 9: 1910

Improvisation 10: 1910

Improvisation 11: 1910

Improvisation 12 (Rider): 1910

_1910.jpg)

Improvisation 14: 1910

Improvisation 19: 1911

Improvisation 21a: 1911

Improvisation 26 (Oars): 1912

_1912.jpg)

Improvisation 28 (Second Version): 1912

_1912.jpg)

Improvisation 30 (Cannons): 1913

_1913.jpg)

Improvisation 31 (Sea Battle): 1913

_1913.jpg)

Improvisation: 1914

Improvisation Deluge: 1913

In Blue: 1925

In Grey: 1919

In the Forest: 1904

Interior (My Dining Room): 1909

_1909.jpg)

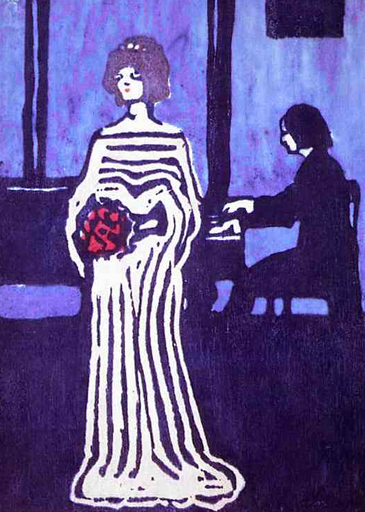

Lady in Moscow: 1912

Lyrical: 1911

Moscow I: 1916

Mountain: 1909

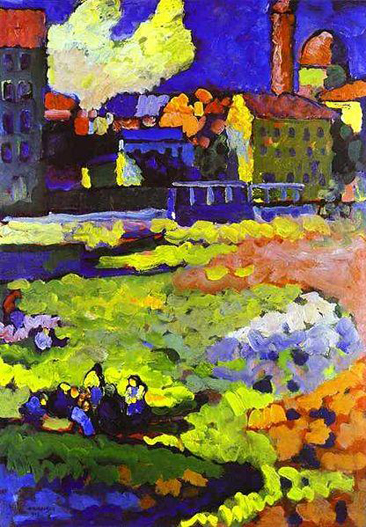

Munich Schwabing with the Church of Saint Ursula: 1908

Murnau-Garden I: 1910

Murnau-View with Railroad and Castle: 1909

Old Town II: 1902

On Points: 1928

On White II: 1923

Orange Violet: 1935

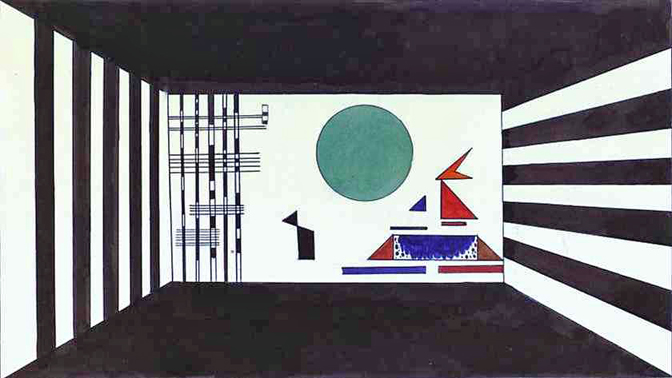

Picture II, Gnomus Stage set for Mussorgsky's Pictures at an Exhibition in

Friedrich Theater, Dessau: 1928

Picture with a Black Arch: 1912

Picture with Archer: 1909

Picture with White Border: 1913

Picture XVI, The Great Gate of Kiev Stage set for Mussorgsky's Pictures at an

Exhibition in Friedrich Theater, Dessau: 1928

Ravine Improvisation: 1914

Red Oval: 1920

Red Spot II: 1921

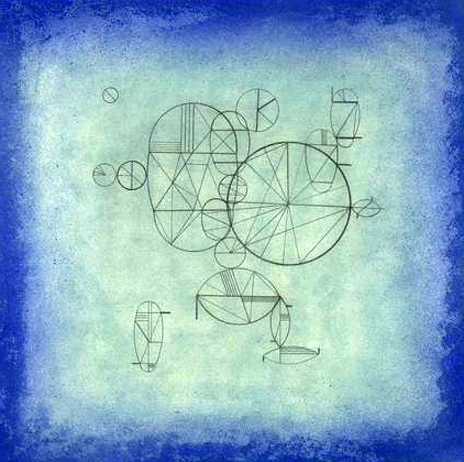

Several Circles: 1926

Sky Blue: 1940

Small Pleasures: 1913

Small Worlds II: 1922

Small Worlds III: 1922

Storeys: 1929

Study for Composition II: 1910

Tempered Elan: 1944

The Golden Sail: 1903

The Singer: 1903

To the Unknown Voice: 1916

Twilight: 1943

Untitled (First Abstract Watercolor): 1910

_1910.jpg)

Untitled: 1941

Upward: 1929

Volga Song: 1906

White Figure: 1943

White Stroke: 1920

Three Wives of Wassily Kandinsky

Kandinsky came into art relatively late, at the age of thirty, and quite unexpectedly for everyone around him. Brushing aside his academic career he left Russia for Germany taking only his wife, Anna Chimyakina, with him. Anna, who was also Kandinsky's cousin, was not an ordinary person for her time - she was one of the first women-students of the Moscow University, where Kandinsky was a lecturer. We can't say that she did not like art. But to love art and to be married to a painter are absolutely different things. Anna, who had married a man of the respectable profession of a lawyer, was not enthusiastic at the prospect of bohemian surroundings. Though reluctantly, she still followed her husband to Munich, only to leave him seven years later and to give him an official divorce in 1911.

By that time there was another woman in his life - a German painter named Gabriele Münter. They got acquainted in 1901, when Gabriele enlisted as an art student in the newly opened Phalanx Art school. State art academies did not admit women-students at the time. The school existed for only a year and had to close, but Gabriele remained with Kandinsky as his student and as an intimate friend. When in 1904 Kandinsky split with his wife, they started to live together. It was a very bold action for a young woman of the beginning of the 20th century - she openly lived with a married man as his wife. And though it was more or less acceptable in bohemian circles, it was quite inappropriate among the bourgeois that they both came from.

Gabriele Munter Painting in Kallmunz: 1903

At that time it did not matter for them, they were both in love. Portrait as a genre is not present in his heritage, but Kandinsky made only one exception: for Gabriele. Her portrait of 1905 shows a big-eyed woman, not exactly a beauty with a massive nose and a small chin, thin lips and high forehead. Was she a woman an artist could dream of? She was an artist herself, both brave an ambitious, but still a woman, sensitive, understanding and loving. Unfortunately for her, her passionate love to Kandinsky would make her unhappy for many years.

Gabriele Münter: 1905

In 1904 they started traveling throughout Europe and Northern Africa, settling back in Munich in 1908. Gabriele bought a country house in Murnau, in the Bavarian Alps, where they spent their summer months; the house was also intended as the home to which the artist couple would retire in their old age. Kandinsky had simple furniture made for the interior, some of which he decorated himself with stylized flowers and riders on galloping horses.

Though officially Kandinsky's student, Gabriele had her own vision and style in painting, which very much probably influenced his style and vision for a time and might be a reason of his irritation with her. In time their relations became more and more complicated, one day he would ask Gabriele to marry him, another day he would insist on their immediate separation.

What happens to people's love, and where it goes, who can say? While she was an admiring student she seemed an inspiring muse to him. When she became more independent, developing her own painting style, and refusing to follow his, and quite probably influencing his own style, she began to irritate him. The beginning of the WWI was a good pretext for him to break relations with Gabriele. First leaving Germany together, Kandinsky soon returned to Moscow, while Gabriele had to go back to Munich. They corresponded, she wrote a lot of letters to him. Their final meeting took place in Stockholm in December 1915. It was to be the last time they saw each other, although their correspondence continued for another year. Gabriele could not suppress the painful and destructive passion for the man, although for him she was already the past.

In September 1916 Kandinsky, aged 50, had a new love affair, which ended by marriage in February 1917. The news of his marriage was such a shock for Gabriele that she could not paint for several years. But time heals and she recovered, and returned to painting and, we hope, lived happily ever after, forgiving, if not forgetting, her genius's betrayal. All her life Gabriele praised Kandinsky, while he never mentioned her or her work. This only strengthens our suspicions that he as a painter owes much to her.

As for Kandinsky, he was happy in his new marriage. At last he found the woman he had dreamed of. Who was she? One Nina Nikolayevna Andreevskaya, a young Russian. Though a recent story, there is a lot of unknown in it. Even Nina's birth date. She never mentioned it, it's only known, from her own words, that she was 27 years younger than her husband. According to her own memoirs she was the daughter of a general (researchers failed to find a general Nikolai Andreevsky among 1248 generals, aged 40-90, listed in the Russian army in the late 1890's - early 1900's). According to some Russian researchers she was the daughter of one captain Andreevsky, who was killed in the Russo-Japanese war in 1905. Later, being already the wife and then the widow of a famous man, Nina was very much anxious to create a legend about herself. Some biographers insist that Kandinsky married a simple housemaid. Not quite improbable. There were a lot of intellectual friends around him, did he need another intellectual at home? Once he had an intellectual wife and an intellectual girlfriend. Quite enough. But from her very first days outside Russia, Nina insisted that she was from a good family. "Good" meant, if not nobility, then at least intelligentsia, otherwise she might not be admitted in Russian emigrant circles, which at that time were all "good" families.

How did Kandinsky and Nina meet? If we follow Nina's legend, then first by phone; she called him on behalf of a friend to deliver a message and her "voice made a deep impression on" him. He even executed a watercolor "To the Unknown Voice", which, according to Nina, was devoted to her voice.

In February 1917 Kandinsky, now aged 51, married the much younger Nina. "Our marriage marked the start of spring in the autumn of his life. We fell in love at first sight, and for that reason we were never apart for one day," wrote Nina Kandinsky in her memoirs. They left for Finland for their honeymoon but had to return soon because of the revolution in Russia. Their first and only son, Vsevolod, was born the same year; the little boy died in 1920 during the Civil war in Russia, unable to survive undernourishment and some infectious disease.

In December 1921 Kandinsky and Nina set off for Berlin, leaving hungry and ruined Russia behind. Abroad Nina shared Kandinsky's life completely, "never separating for a day", never standing out, always in the shade of her genius husband.

When the artist died in December 1944, his widow was his only heiress. She founded the Kandinsky Fund for studying, exhibiting and preserving his works. The biggest part of the Fund she later contributed to the Centre of Georges Pompidou in Paris.

Nina never remarried again. But being very rich, she was always surrounded by young men of the gigolo sort and she liked that. She also loved jewelry, bought it eagerly, and had a big collection. In 1983 she was killed in Switzerland in her villa, and maybe the collection played a fatal role in that. The murderers were never apprehended. Nina was buried in Paris and soon forgotten. Her memoirs are interesting, but should be read very critically, as they are full of Hollywood style fairy-tales.

Quoted From: Three Wives of Wassily Kandinsky - Olga's Gallery

Source: Wassily Kandinsky - Olga's Gallery

Round Poetry: 1933

Return to Pagina Artis

Return to Bruce and Bobbie's Main Page.